Infantile amnesia psychology

What Is Infantile Amnesia?

Written by Alyssa Anderson

Medically Reviewed by Poonam Sachdev on April 28, 2022

In this Article

- What to Know About Infantile Amnesia

- How Does Your Brain Handle Memories?

- Types of Memories Involved in Infantile Amnesia

- Infantile Amnesia Causes

- What Are Other Kinds of Amnesia?

Infantile amnesia is a version of amnesia that seems to be a side effect of your brain’s normal developmental processes. As a result, almost all people have trouble remembering any biographical events before the age of four years old.

The rate of memory also remains lower than expected up until sometime between the ages of seven and ten years old, so it’s commonly referred to as childhood amnesia.

The exact cause of infantile amnesia remains a heavily debated issue in modern neuroscience.

What to Know About Infantile Amnesia

Almost every adult studied to date has infantile amnesia. Infantile amnesia best explains why we have so few early memories compared to our later childhood, teenage years, and beyond.

The few rare exceptions tend to occur in people that store memories unusually even when they’re adults. There’s even evidence of parallels to infantile amnesia in other mammalian species — like rats.

There are a few questions raised by this condition, and some are more easily solved than others.

The first discrepancy is that — based on the rate that adults forget memories — humans have too few memories from early childhood. In support of this, newer research that actually involves children seems to clearly show that they forget at a much faster rate than adults. A follow-up question is why and how this is the case.

The second discrepancy concerns how childhood memories — which we can no longer recall or discuss — can still have large impacts on your adult psychology.

Studies have shown that events like abuse, trauma, and neglect — even when they occur in the time frames encompassed by infantile amnesia — can predispose adults to a number of psychopathologies. Examples include:

Examples include:

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

- Borderline personality disorder

- Depression

- Anxiety

Data from neglected children show that they almost all have problems with learning and other cognitive functions. Some of these abilities can improve with proper care, but others never recover from childhood problems.

So, how can events that we can no longer consciously remember or articulate have such large impacts on our continued development? What is happening in our brains during the ages when infantile amnesia is most prevalent?

These are just some of the questions that researchers are trying to solve today.

How Does Your Brain Handle Memories?

In order to understand the potential causes of infantile amnesia, it’s important to know how your brain handles new memories. There are four basic steps to creating and accessing a new memory. These involve:

- Encoding information.

First, your brain forms a series of connections to represent new information.

These can be linked to other information that is already stored in your memory. Oftentimes, you need to be paying attention to adequately store this information.

These can be linked to other information that is already stored in your memory. Oftentimes, you need to be paying attention to adequately store this information. - Consolidation. This step ensures that the encoded information is preserved in your brain for the short or long term.

- Storage. Your brain then holds onto your consolidated memories for later use.

- Retrieval. Your brain either recreates or reactivates the original connections in order to consciously remember the encoded information.

Keep in mind that these descriptions are highly simplified. Each one of these steps is a complex process that isn’t fully understood, but we do know that these processes are likely not fully developed in infants and young children. This lack of development is possibly related to how and why infantile amnesia occurs.

Types of Memories Involved in Infantile Amnesia

Humans make a number of different kinds of memories. Certain ones are more affected by infantile amnesia than others.

Certain ones are more affected by infantile amnesia than others.

Two broad categories of memories include declarative or explicit memories and non-declarative or implicit memories.

Declarative memories are ones that you can consciously recall and discuss. They include episodic memories about different people, events, times, and places. They also include semantic memories, which are more general things you’ve learned about the world.

These are different from implicit memories, which are more ingrained and less accessible to your conscious mind. Examples include the knowledge of how to walk or ride a bike.

All forms of amnesia affect declarative memories, not non-declarative ones. Infantile amnesia specifically involves these autobiographical memories — the same types that are lost in cases of Alzheimer’s and other age-related memory disorders.

Infantile Amnesia Causes

At present, no one knows the exact cause of infantile amnesia. A leading hypothesis is that it’s a consequence of the particular way that our brains develop.

The part of your brain called the hippocampus is most likely involved in this process. It helps create the autobiographical memories that are missing in cases of infantile amnesia. Studies have shown that the hippocampus only reaches some degree of maturity when you’re between 20 and 24 months of age. It’s almost fully formed, though, by the age of five.

This developmental timeline happens to coincide nicely with the ages that are most affected by infantile amnesia.

Another question is whether or not this amnesia is a problem with learning and forming memories or storing and retrieving them properly. Most experts agree that even very young infants can learn and form autobiographical memories even before they can talk.

For example, a study done at Yale showed infants two sets of images. One set contained a coherent story, and the others were completely random. The babies responded much more to the first set than the second set. Other studies have shown that infants can imitate sequences of actions that they’ve just watched.

Additionally, very young children can remember autobiographical events that occurred up to six months ago — even when they’ve just learned to talk.

All of this implies that children are capable of storing some autobiographical memories, so they must forget them at a much faster rate.

The next question is if these memories are forgotten because of improper storage or problems with retrieval. More research is needed to answer this question.

One theory is that infantile amnesia is a consequence of the hippocampus learning how to remember. It’s starting to do all of the right memory creation processes — encoding, storage, retrieval — but can’t do them as well as it can when you’re an adult.

Since research is ongoing, there’s likely to be more data soon that can shed light on the exact causes of infantile amnesia.

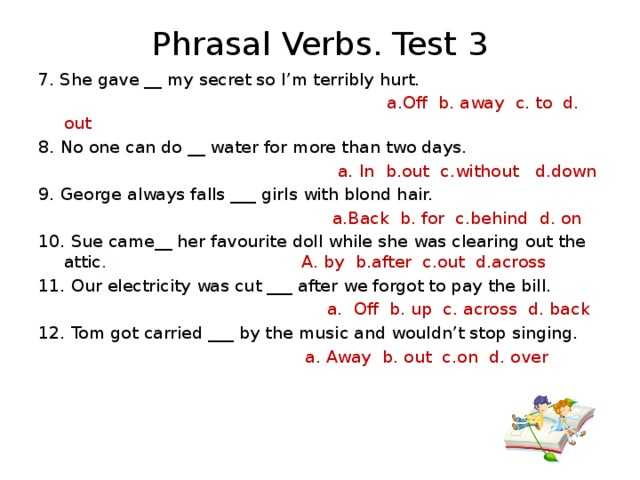

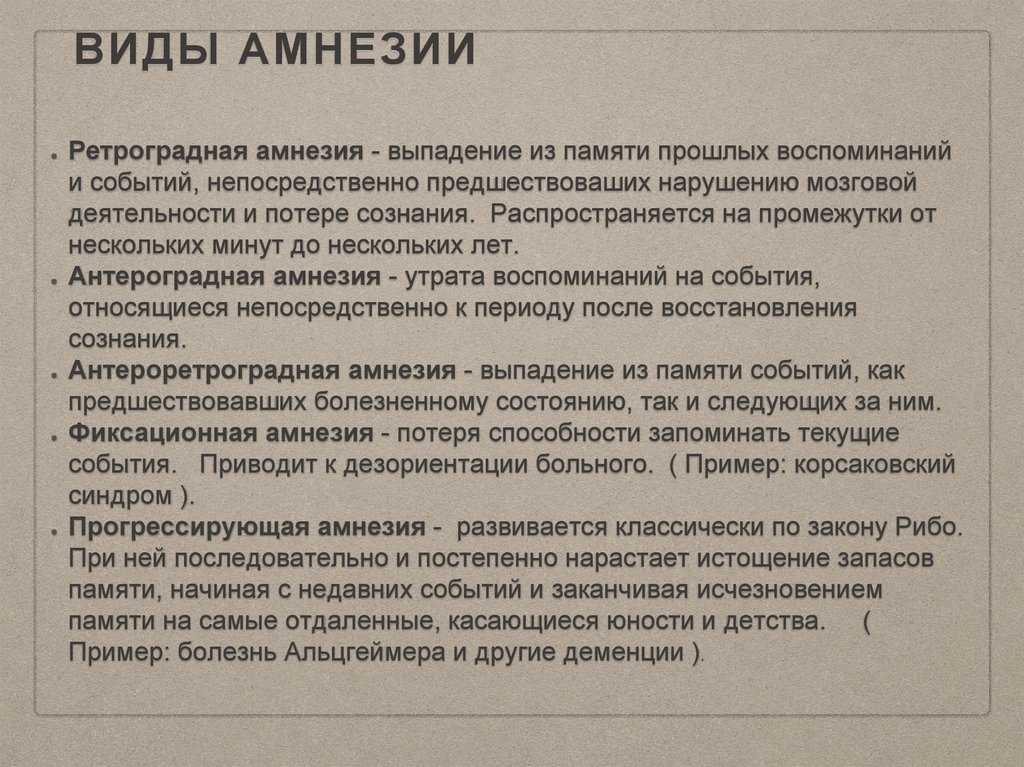

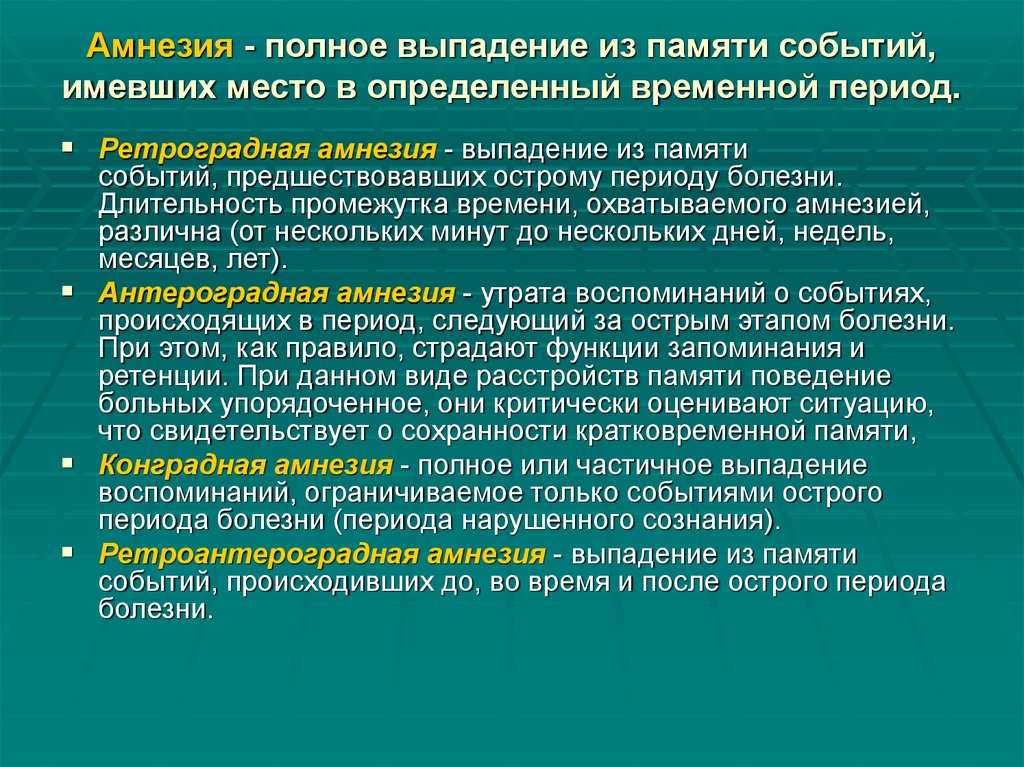

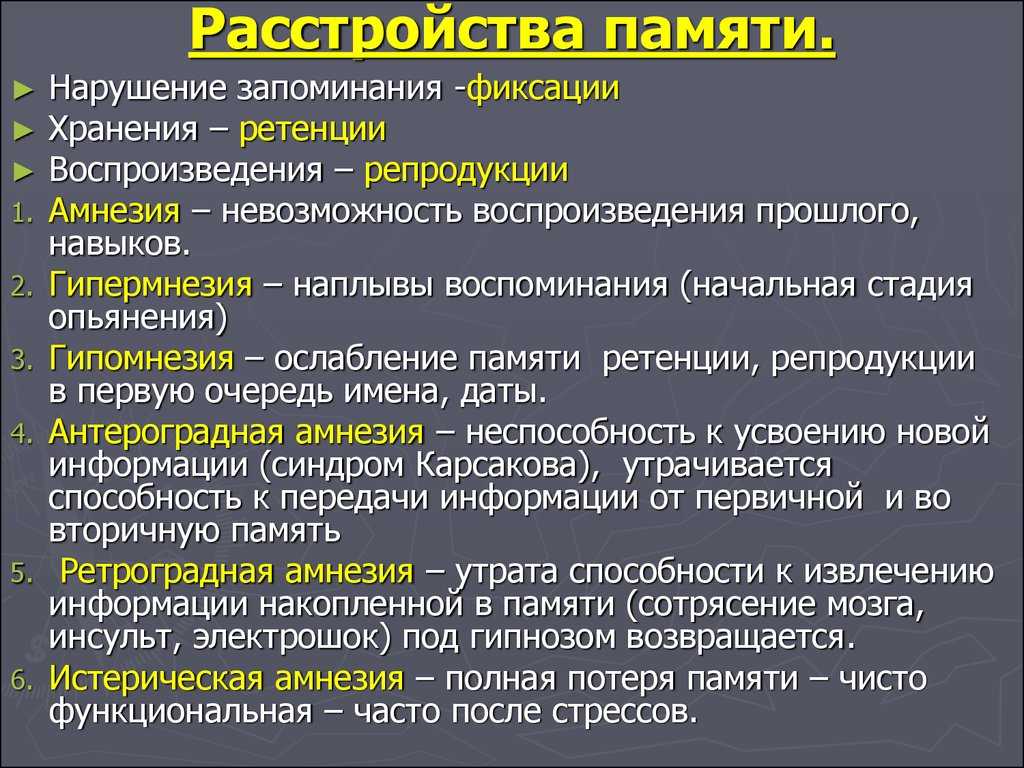

What Are Other Kinds of Amnesia?

Infantile amnesia is the only type of amnesia that’s a normal part of human development. All other types are caused by trauma, injury, or systemic illness.

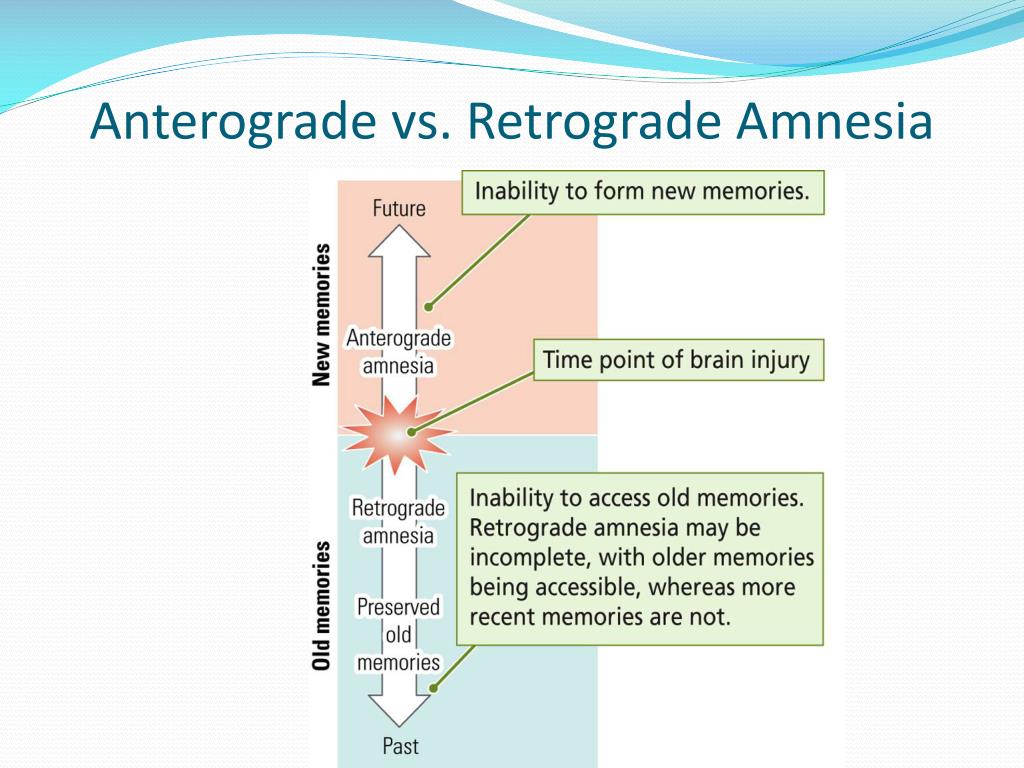

In general, there are two broad categories of amnesia. Retrograde amnesia is diagnosed when you can no longer recall information from the past. All infantile amnesia is a form of retrograde amnesia. Anterograde amnesia occurs when you can no longer form new memories.

Exploring Childhood Amnesia | Psychology Today

What is your earliest memory?

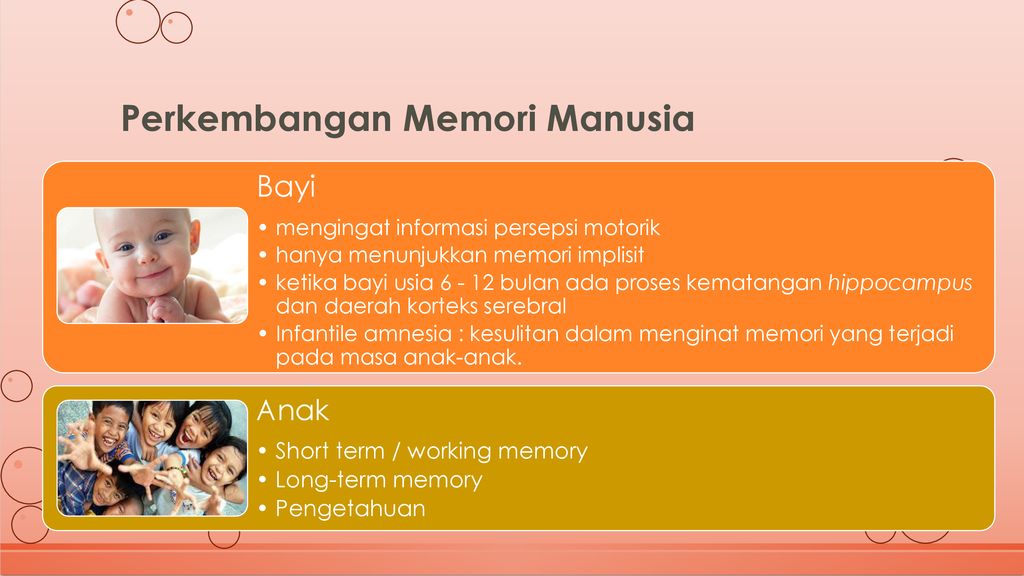

By the time children are two years old, they are able to answer questions about recent events, although they often need careful prompting to retrieve memories. Over the next four or five years, children become better at recalling and describing important events in their lives.

By the age of seven or eight, most children have well-developed autobiographical memories with the same rate of normal forgetting seen in adults.

When questioned about earlier memories however, children are rarely able to recall memories of events that happened earlier than age three or four, and these early memories become even harder to access as they grow older.

Despite decades of research, understanding why this childhood amnesia happens remains a mystery.

Though children can be prompted to recall early memories, this recall is often plagued by problems with false memory caused by leading questions and unintentional cues on the part of adults. For this reason, the American Psychiatric Association has cautioned against cases of adults recalling events of abuse that apparently occurred at a very early age without physical evidence.

For adults, however, recall of memories before the age of three or four is virtually impossible regardless of the method used to retrieve those memories, whether through free recall or by targeted recall (such as the birth of a sibling).

Over the past century, research into the earliest age for which adults can recall a life event has been remarkably stable. Those memories typically begin at about age three or four with the number and quality of memories available gradually increasing over time.

The most widely used method for testing childhood amnesia is the cue word technique. First developed by Sir Francis Galton in his early research on memory, the technique involves giving participants certain words (eg., dog, cat, or chair) and then asking them to "think of a specific memory" associated with that word as well as estimate their age at the time when they experienced that memory. Cue word methods are often used to test autobiographical memory across the entire lifespan.

By comparing recall at different ages, memory researchers have identified the rate of normal forgetting that occurs for memories developed from the age of eight onward. From that point on, amnesia for early childhood events becomes well established with little change over time.

For example, research comparing how well 20-year-olds and 70-year-olds can recall events from early childhood show no real difference in memory despite the decades that have passed.

So why does childhood amnesia occur?

Various explanations have been offered, including Freud's theory that childhood amnesia is caused by repression of traumatic memories occurring in the child's early psychosexual development.

More modern theorists, however, argue that the key to forgetting lies in the early development of the brain itself. While young children and even infants appear able to recall information for weeks or months, linking those memories to verbal cues is more difficult.

In one intriguing research study looking at memory recall from early to middle childhood, 7- to 9-year-old children were interviewed about events they had previously recalled with their mothers at the age of three. Among 7-year-old children, 60 percent recalled the same events while children tested at age 8 or 9 remembered only 36 to 38 percent of the events.

This suggests that amnesia for early events occurs rapidly over only two years. Overall, younger children appear far more vulnerable to forgetting than older children.

While there appear to be sex differences in childhood amnesia, with girls being better able to recall early memories than boys, the rate at which early memories are forgotten throughout later childhood is still debated by researchers.

In a new research study published in the Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, the cue-word technique was used to test autobiographical memory in children aged seven to eleven years old and compared with findings from young and middle-aged adults. The research was conducted by Patricia Bauer and Marina Larkina of Emory University as part of their ongoing examination of why childhood amnesia occurs.

By comparing rates of forgetting between children and adults, Bauer and Larkina hoped to test the age of earliest memory among children, college students, and middle-aged adults as measured by cue words.

Along with replicating earlier research looking at childhood amnesia in children, looking at recall of earliest memories in adults allowed them to measure how stable childhood amnesia remains over time.

The participants in the study were 100 children aged 7 to 11 with 20 children in each of the 5 age groups (52 girls and 48 boys). The 2 adult groups consisted of 20 adults each (average age of 19 and 43).

Each participant was tested using the cue-word method, asking them to recall a life event linked to 1 of 20 neutral cue words. After describing the event, they were then asked to provide more details and to recall their age at the time the event occurred as well as the time of year.

Since the parents of most of the children participating were in the room, they were able to provide written feedback about how accurate the memory was. All of the events were recorded on video and scored by independent raters.

Results showed that most of the memories that children recalled occurred in the previous year but the age of earliest memory tended to be about 3.67 years. There was no real difference between the different age groups or the two adult groups. Even for older adults, the age of earliest memory was not much different despite the decades that passed from early childhood.

One important finding was that children rapidly forgot memories of early childhood but that forgetting slowed as children grow older. This suggests that the number of available memories relating to early childhood rapidly shrinks in children. For adults, however, memories are less vulnerable to forgetting due to better memory consolidation.

This suggests that the number of available memories relating to early childhood rapidly shrinks in children. For adults, however, memories are less vulnerable to forgetting due to better memory consolidation.

So what does this mean in explaining childhood amnesia? While the age of earliest recall seems remarkably stable for both older children and adults, the rapid forgetting that causes early memories to fade means that childhood amnesia emerges fairly early in childhood (by the age of 7 years old). As to why this happens, one important clue can be found in the narrative reports that children provide when questioned about specific memories.

In the study by Bauer and Larkina, 7-year-old children needed considerable prompting to describe events that happened to them while older children and adults provide richer, more verbally complete, narratives with little need for extra prompting.

Since narrative retelling allows us to "rehearse" important memories and retain them longer, memories that are not rehearsed become inaccessible over time and can be quickly forgotten as a result.

As children grow and mature, autobiographical memory matures as well. By the age of eleven, autobiographical memory shows the same level of development seen in adults. Prior to that time, however, forgetting appears to be much faster than in adults which may be due to memories failing to consolidate which makes them more vulnerable to memory loss.

As Bauer and Larkina point out in concluding their study: "Accelerated forgetting throughout childhood results in an ever-shrinking pool of memories from early in life. The resulting distribution of memories reveals childhood amnesia in the making."

Like so many other things children learn as they grow older, the ability to remember is a skill that develops with time. So cherish those memories of your children's early lives and those events that are all too quickly forgotten by growing children.

Some aspects of infantile amnesia | Journal of Practical Psychology and Psychoanalysis

Year of publication and journal number:

2001, No. 3

3

The absence of memories of early childhood in psychoanalysis is called infantile amnesia. Due to the fact that the author of this article is a staunch supporter of the psychoanalytic concept of personality, the term "infantile amnesia" will continue to be used to characterize the individual's inability to reproduce from the long-term memory of his infantile and early childhood experiences.

Today there is no unambiguous point of view on the problem of infantile amnesia accepted by everyone in scientific (psychological, philosophical, medical) circles. As you know, even before Freud, infantile amnesia was explained from the standpoint of the functional immaturity of the organism. Moreover, there is still an opinion that the reasons for this phenomenon lie in the underdevelopment of certain parts of the brain. We, in turn, in this article will try to consider this issue from the standpoint of psychology, partly medicine and partly from the standpoint of philosophical teachings, although we perfectly represent the controversy of everything that will be said below.

The discovery of infantile amnesia does not belong to psychoanalysis. However, faced with this phenomenon, Freud offered his own peculiar interpretation, in which he explained this fact from the position of not forgetting, but of repression. Moreover, Freud saw infantile amnesia as a condition for subsequent repressions and, in particular, hysterical amnesia (Laplanche J., Pontalis J., M., 1996). In his work “Three Essays on the Theory of Sexuality,” Z. Freud wrote: “On the other hand, we must admit, or can be convinced by doing psychological research on others, that the same impressions that we have forgotten have nevertheless left the deepest traces in of our mental life and had a decisive influence on our further development.It is therefore not at all about the real loss of childhood memories, but about amnesia, like that which we observe in neurotics in relation to later experiences, and the essence of which consists only in the prevention of consciousness (repression). But what forces accomplish this repression of childhood impressions? Whoever solves this riddle will also explain hysterical amnesia" (Psychoanalysis of child sexuality. 1997).

1997).

Thus, amnesia usually hides from us the facts of the first years of life. The psychoanalytic trend sees the causes of infantile amnesia, which extends to almost all childhood events, in the repression of childhood sexuality. The time limit of the period covered by infantile amnesia is the extinction of the Oedipus complex and the entry into the latent period. After all, this is precisely the period when the sexuality of the child is free from control by moral norms, internalized into the structure of the personality in the form of the Super-Ego, and contact with the mother as with the first sexual object is characterized by special intimacy. However, we see the issue of the boundaries of infantile amnesia as rather controversial: they do not always extend up to 6-8 years of age. In our opinion, the boundaries of amnesia are of a floating nature and not everyone is the same, but there is no doubt that the memories of the first two or three years are practically absent in the average individual. If we strive for accuracy, then the information of M.J. Hiccup and R.A. Crawls, who in their research concluded that the age of 2.5 years is the limit of infantile amnesia (M. J. Eacott, R. A. Crawley., 1998).

If we strive for accuracy, then the information of M.J. Hiccup and R.A. Crawls, who in their research concluded that the age of 2.5 years is the limit of infantile amnesia (M. J. Eacott, R. A. Crawley., 1998).

Other representatives of the psychoanalytic school partly accepted Freud's position, partly expressed their own hypotheses, which most often indicated the presence of basic anxiety that begins at the moment of the birth of a child and affects the subsequent life of the individual. From the point of view of G. Sullivan, anxiety and fear cover the child already in the first seconds of life, when he encounters a lack of oxygen at the moment preceding the first cry. Then, in his opinion, anxiety can be determined by the child's discovery of his powerlessness in front of the outside world and in the fulfillment of certain desires. It is this kind of anxiety, according to Sullivan, that is the trigger for the development of actions, thinking, the ability to anticipate, etc., since such neoplasms help to minimize anxiety and fear, and also inspire hope in the ability to control various kinds of events (Mead M. , 1988).

, 1988).

Otto Rank saw the cause of basic anxiety in birth trauma. In Birth Trauma, Rank contrasts the blissful self-feeling of a child in the womb with the act of birth, which involves a severe shock, both physical and psychological.

This primary trauma, which the individual seeks to overcome, is the key to many human reactions. Its consequences are found at all stages of human development.

Throughout childhood, a person tries to overcome the trauma of birth. This he succeeds later, at the time of the flowering of sexuality. If birth traumatism cannot be overcome, mental disorders are inevitable.

According to Rank, the treatment for such mental disorders consists in getting rid of this primary shock through therapeutic treatment (Marson P., 1999).

Melanie Klein saw the origin of anxiety and fear in the envy and gratitude that a child feels for his own mother. M. Klein believed that the "I" (the personality of the baby) immediately experiences a load of vital functions. Unlike Freud, who did not recognize the existence of "I" (Ego) in an infant, Klein believed that - "... the Ego exists from the very beginning of postnatal life, although in a rudimentary form, and in many respects is not united enough" (Marson P., 1999). From the very beginning of his life, he is overcome by anxiety, the main cause of which is envy. In response, the child splits all objects into good and bad and equips himself with the whole arsenal of means of protection. The "I" constantly strives to protect itself from the suffering and tension caused by anxiety. It is worth noting that, according to Melanie Klein, the main and dominant function of the "I" is to deal with anxiety (Klein M., 1997).

Unlike Freud, who did not recognize the existence of "I" (Ego) in an infant, Klein believed that - "... the Ego exists from the very beginning of postnatal life, although in a rudimentary form, and in many respects is not united enough" (Marson P., 1999). From the very beginning of his life, he is overcome by anxiety, the main cause of which is envy. In response, the child splits all objects into good and bad and equips himself with the whole arsenal of means of protection. The "I" constantly strives to protect itself from the suffering and tension caused by anxiety. It is worth noting that, according to Melanie Klein, the main and dominant function of the "I" is to deal with anxiety (Klein M., 1997).

Thus, we see that anxiety and fear are an integral attribute of the birth of a child and its further development as a person. This problem is reflected in the concepts of Adler and Grof. Thus, depth psychology and psychoanalytic direction directly or indirectly consider the phenomenon of infantile amnesia through the prism of repression, the cause of which is traumatic experiences of the ego in the first years of life.

However, we believe, unlike a large number of psychoanalysts, that traumatic events in a child's life begin even before he is born, that is, even in the prenatal phase, or rather, in the fetal period of his development, which continues from the beginning of the third month of pregnancy and until the moment of birth. Lloyd de Mause, for example, writes superbly about this problem.

Medicine has only recently begun to take an interest in the study of the fetus. This state of affairs was most often explained by the inaccessibility of the child for study in the womb. The results of the latest research were merged into one general direction, which shifted the beginning of all stages of development and the emergence of sensory capabilities of the fetus to an increasingly earlier stage. This is especially true for the development of the brain, nervous system and sensory apparatus, which begins in the first month after conception.

Scientists have found that physical development is far from the only process that occurs with the human body during the prenatal period. Already at the age of 15 weeks, the fetus is able to make grasping movements, wince, move its eyes and grimace. Reflex movements are caused by irritation of the soles or eyelids. By the 20th week, the organs of taste and smell develop. By the 24th week, skin sensitivity develops more fully, the fetus begins to respond to sound, and by the 25th week, the reaction to sound becomes quite stable. At 27 weeks, the fetus can already turn its head in the direction of the light directed at the mother's abdomen. At the 8th month, the susceptibility of the fetus and the variety of forms of its behavior increase significantly. Some scientists believe that in the middle of this month, the eyes of the fetus are already opening and he can see his hands and the surrounding space, despite the fact that the inside of the uterus is dark. Scientists also believe that from the 32nd week the fetus begins to be aware of what is happening, since many of the neural systems of the brain have already formed by this time.

Already at the age of 15 weeks, the fetus is able to make grasping movements, wince, move its eyes and grimace. Reflex movements are caused by irritation of the soles or eyelids. By the 20th week, the organs of taste and smell develop. By the 24th week, skin sensitivity develops more fully, the fetus begins to respond to sound, and by the 25th week, the reaction to sound becomes quite stable. At 27 weeks, the fetus can already turn its head in the direction of the light directed at the mother's abdomen. At the 8th month, the susceptibility of the fetus and the variety of forms of its behavior increase significantly. Some scientists believe that in the middle of this month, the eyes of the fetus are already opening and he can see his hands and the surrounding space, despite the fact that the inside of the uterus is dark. Scientists also believe that from the 32nd week the fetus begins to be aware of what is happening, since many of the neural systems of the brain have already formed by this time. Brain scan shows periods of REM sleep. With the transition to 9Month 1 of prenatal development, the fetus establishes daily sleep-wake cycles and completes hearing development (research finds that the sound of a metronome tuned to the mother's heart rate has a calming effect on the newborn) (Craig G., 2000).

Brain scan shows periods of REM sleep. With the transition to 9Month 1 of prenatal development, the fetus establishes daily sleep-wake cycles and completes hearing development (research finds that the sound of a metronome tuned to the mother's heart rate has a calming effect on the newborn) (Craig G., 2000).

Thus, we see that the child already in the fetal period has all the necessary physical and mental formations in order to fully perceive and reflect the surrounding world, not only localized in the uterus, but also outside it; moreover, some studies show that the child, being in the womb, is already capable of learning.

Returning to our thesis regarding doubts about the completely favorable stay of the child in the uterus, we would like to cite the following data presented by Lloyd de Mose.

Moz has no doubt that the womb is not the safest place for a child, especially given the complete dependence on it. So, for example, when a mother smokes, the fetus “smokes” with her, and after a few puffs, his heart starts to beat faster, he feels a decrease in the amount of oxygen and an increase in the amount of carbon dioxide. When a mother takes alcohol, alcohol goes directly to the fetus and soon reaches almost the same level in the blood as the mother. The same applies, of course, to many other narcotic substances, including caffeine - they all go straight to the fetus, penetrating the so-called "placental barrier" and have a wide variety of harmful effects, including through hypoxia. The listed harmful effects of the intrauterine environment are so common that the fetus rarely manages to avoid them, and this is just a small dose of the threat posed by complete dependence on the mother and her body (Moz L., 2000).

When a mother takes alcohol, alcohol goes directly to the fetus and soon reaches almost the same level in the blood as the mother. The same applies, of course, to many other narcotic substances, including caffeine - they all go straight to the fetus, penetrating the so-called "placental barrier" and have a wide variety of harmful effects, including through hypoxia. The listed harmful effects of the intrauterine environment are so common that the fetus rarely manages to avoid them, and this is just a small dose of the threat posed by complete dependence on the mother and her body (Moz L., 2000).

In the process of its development, the child also experiences serious upheavals coming from the emotional dissatisfaction of the mother, marital quarrels and simply unwillingness to have an already developing child. It is now often recognized that maternal fears, fear, tension, temper tantrums, frustrations, shocks, stresses, depressions, and similar mental conditions can seriously harm the developing fetus.

During the last three months of his stay in the womb, the child experiences increasing discomfort. As it grows, it becomes more and more crowded inside the uterus, which causes a lot of suffering. He sleeps more and moves less. The most important problem for a fetus in such a "new" cramped uterus is that it is now too large for the placenta to fully provide it with food and oxygen, as well as clean its blood of carbon dioxide and waste products.

This unfavorable situation for the child becomes more and more aggravated as the childbirth approaches. During this period, the placenta performs its functions less and less efficiently, and the need for oxygen, nutrition, and the purification of blood from carbon dioxide becomes more and more noticeable. As a result, stress increases and is transferred by the fetus more and more painfully.

During the labor pains themselves, the oxygen supply becomes even lower than the critical level. Moz writes: - "... at the beginning of labor, the oxygen level in the scalp of the fetus drops to 23%, and just before childbirth - to 12% (in adults, the central nervous system cannot withstand a level below (> 3%) - a discovery that even led the most cautious obstetricians to the conclusion that "hypoxia of a certain intensity and duration is a normal phenomenon in any childbirth. Such severe hypoxia affects the fetus in the strongest way: normal breathing stops, the heartbeat first accelerates, then slows down, often the fetus thrashes furiously in response to pain from contractions and hypoxia and soon enters into a life-and-death struggle for release from such terrible conditions" (Moz L., 2000).

Such severe hypoxia affects the fetus in the strongest way: normal breathing stops, the heartbeat first accelerates, then slows down, often the fetus thrashes furiously in response to pain from contractions and hypoxia and soon enters into a life-and-death struggle for release from such terrible conditions" (Moz L., 2000).

As we have seen, the stay of the child in the womb is not as prosperous and safe as it seemed to a large number of psychoanalysts (Freud, Ferenczi, Rank, etc.). However, as we know, the threat to the life and health of a child does not stop with his birth, but only intensifies. A huge number of diseases, unfavorable ecology, careless handling, dissatisfaction (due to various reasons) of the basic needs of the child, and simply abandoning him and even killing him are clear evidence that his life is in danger.

Even until recently (and still in some cultures at a more primitive level of development) the death of a child was quite common (Mead, Cohn, Moz). Moreover, until the 19th century, many civilized countries even practiced killing children.

Moreover, until the 19th century, many civilized countries even practiced killing children.

Until the fourth century AD e. neither law nor public opinion condemned infanticide in Greece or Rome (Moz L., 2000). Not to mention the killing of girls and illegitimate children, which not only was not condemned and not prosecuted by law, but, it seems, was even encouraged in society. It's no secret that back in the 19th century in London in the mornings, dozens of discarded children could be found in the canals.

With the development of civilization came the condemnation of infanticide both by society and by law. However, this does not yet mean that the situation of the child, especially at his most helpless age, has improved dramatically. Parents still had a huge number of ways to get rid of the child in the literal or figurative sense. We are talking about raising children away from home, nannies, wet nurses, swaddling, etc. Moz writes that swaddling was often such a complex procedure that it took up to two hours. For adults, swaddling made it possible to indirectly get rid of the child, since swaddled children were no longer paid attention to. As recent medical studies show, swaddled children are extremely passive, their heartbeat is slow, they cry less, sleep much more, and in general are so quiet and lethargic that they practically do not cause any trouble to their parents. In fairness, it should be noted that some theories do not see anything wrong with swaddling and do not see any reason for parents to worry about the full, in terms of motor skills, development of the child (Gleitman H., 1999). However, the usefulness of the individual and her mental health is not only in motor skills. In this regard, we see it as important to conduct more in-depth research on swaddling and its impact on the further development of the individual.

For adults, swaddling made it possible to indirectly get rid of the child, since swaddled children were no longer paid attention to. As recent medical studies show, swaddled children are extremely passive, their heartbeat is slow, they cry less, sleep much more, and in general are so quiet and lethargic that they practically do not cause any trouble to their parents. In fairness, it should be noted that some theories do not see anything wrong with swaddling and do not see any reason for parents to worry about the full, in terms of motor skills, development of the child (Gleitman H., 1999). However, the usefulness of the individual and her mental health is not only in motor skills. In this regard, we see it as important to conduct more in-depth research on swaddling and its impact on the further development of the individual.

Without going into the details of a joyless childhood, we want to note that, in our opinion, and as shown by the works of many authors involved in the study of childhood, a threat to the life and health of a child, no matter for what reasons, (there is also a threat to die from the so-called " Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, the nature of which is not fully understood), is most serious and real in the most helpless period of human development, during its prenatal and postnatal development, up to about 3 years. As you know, this is precisely the age limit from which a person begins, albeit fragmentary, memories of his childhood. It is at this age that elementary skills of interaction with the outside world begin to appear, which gives the child the opportunity to at least to some extent feel his independence. At this age, the child can safely feed himself if the food is within his reach, he can also already actively respond to threatening phenomena and objects by avoiding them, etc. Thus, it is from this age, in our opinion, that the self-consciousness of the individual begins to form (here we mean, first of all, the reflexive function of self-consciousness), which allows a person to feel his own, inner world and those processes that occur in his psyche on a completely different quality level. It is from this age, but not earlier, that a person begins to experience fear, anxiety, suffering, resentment and a number of other emotions that he previously experienced mainly at the physiological level in a completely different way.

As you know, this is precisely the age limit from which a person begins, albeit fragmentary, memories of his childhood. It is at this age that elementary skills of interaction with the outside world begin to appear, which gives the child the opportunity to at least to some extent feel his independence. At this age, the child can safely feed himself if the food is within his reach, he can also already actively respond to threatening phenomena and objects by avoiding them, etc. Thus, it is from this age, in our opinion, that the self-consciousness of the individual begins to form (here we mean, first of all, the reflexive function of self-consciousness), which allows a person to feel his own, inner world and those processes that occur in his psyche on a completely different quality level. It is from this age, but not earlier, that a person begins to experience fear, anxiety, suffering, resentment and a number of other emotions that he previously experienced mainly at the physiological level in a completely different way. From this moment, on the one hand, all these experiences become much sharper and more traumatic, and on the other hand, as we have already said, the child acquires the ability to actively and adequately respond to them in order to protect himself. Due to this kind of qualitative transformations, a person acquires the ability to process information coming from the surrounding world in long-term memory in accordance with his internal mental state. That is, the individual begins to clearly realize that this or that event is happening to him, and he is their direct participant.

From this moment, on the one hand, all these experiences become much sharper and more traumatic, and on the other hand, as we have already said, the child acquires the ability to actively and adequately respond to them in order to protect himself. Due to this kind of qualitative transformations, a person acquires the ability to process information coming from the surrounding world in long-term memory in accordance with his internal mental state. That is, the individual begins to clearly realize that this or that event is happening to him, and he is their direct participant.

Returning to the question of the nature of infantile amnesia, we believe that an individual's memories of various events of his childhood and subsequent life, being in a normal state of consciousness, are possible from the moment when he acquired the ability to actively and adequately respond to a threat to his health and life, which means that he had a much better chance of surviving than it was during the period of his complete dependence on his mother and other significant adults. Otherwise, why is it that with a sufficiently developed mental apparatus, formed, as a number of studies show, even in the prenatal period, a person is absolutely unable to remember at least something about the time of his stay inside the uterus or about the time of infancy?

Otherwise, why is it that with a sufficiently developed mental apparatus, formed, as a number of studies show, even in the prenatal period, a person is absolutely unable to remember at least something about the time of his stay inside the uterus or about the time of infancy?

Arthur Schopenhauer in his work "Death and its relation to the indestructibility of our being" pointed out that death itself is inherent only in consciousness (Schopenhauer A., 1997). And although in his work Schopenhauer tries to belittle the trauma of death and, moreover, find some positive aspects in it, which is not surprising, given the suicide of his father, in our opinion, here he expressed an idea that makes it possible to look at the nature of infantile amnesia somewhat differently. Thus, it can be assumed that self-consciousness appears precisely at the moment when the will to live or the ability to actively and adequately respond to a threat to life and health are able to resist death. Freud also pointed out that Eros and Thanatos are present in a person from birth, which are destined to oppose each other throughout the life of the individual. Nature, as it were, is waiting for the moment when the chances of survival equal or exceed the chances of dying. In the event of the death of a child without the ability to self-consciousness in the period of his extreme helplessness, the trauma of death will be minimal for him. After all, even for an adult there is nothing more painful than the realization of one's end, especially when it is close and inevitable. As Schopenhauer wrote: - "... there is nothing worse than the death penalty", or rather its expectation. And a great grace for a person is to die painlessly, in a dream, that is, in an unconscious state.

Nature, as it were, is waiting for the moment when the chances of survival equal or exceed the chances of dying. In the event of the death of a child without the ability to self-consciousness in the period of his extreme helplessness, the trauma of death will be minimal for him. After all, even for an adult there is nothing more painful than the realization of one's end, especially when it is close and inevitable. As Schopenhauer wrote: - "... there is nothing worse than the death penalty", or rather its expectation. And a great grace for a person is to die painlessly, in a dream, that is, in an unconscious state.

Summing up the above, we want to once again concretize our point of view regarding infantile amnesia. We believe that infantile amnesia is due to the lack of a reflexive ability of a person’s consciousness during his prenatal and postnatal development up to 3 years, during his extreme helplessness in front of a threatening environment, as well as dependence on his mother and other significant adults. Thus, traumatic experiences related to the threat to the health and life of the child, which we spoke about above, have a less detrimental effect on his psyche, since they are experienced mainly at the physiological, unconscious level. And hence the memories of events preceding the age of 3 are possible only in an altered state of consciousness, which is achieved through special psychotherapeutic techniques or special chemical agents and psychopharmacological preparations. We also do not deny the existence of a repression mechanism in the nature of infantile amnesia. However, we believe that the causes of repression are due not only to sexual experiences, but to a greater extent to the total threat that accompanies the development of the individual during his period of extreme helplessness, as well as the lack of the reflective ability of the child's consciousness.

Thus, traumatic experiences related to the threat to the health and life of the child, which we spoke about above, have a less detrimental effect on his psyche, since they are experienced mainly at the physiological, unconscious level. And hence the memories of events preceding the age of 3 are possible only in an altered state of consciousness, which is achieved through special psychotherapeutic techniques or special chemical agents and psychopharmacological preparations. We also do not deny the existence of a repression mechanism in the nature of infantile amnesia. However, we believe that the causes of repression are due not only to sexual experiences, but to a greater extent to the total threat that accompanies the development of the individual during his period of extreme helplessness, as well as the lack of the reflective ability of the child's consciousness.

Literature:

1. Adler A. Practice and theory of individual psychology. Moscow 1995.

2. Grof S. Beyond the Brain. Publishing House of the Transpersonal Institute 1993.

Publishing House of the Transpersonal Institute 1993.

3. Klein M. Envy and gratitude. St. Petersburg 1997.

4. Kon I. The child and society. Moscow 1988.

5. Craig G. Psychology of development. St. Petersburg 2000.

6. Laplanche J., Pontalis J. Dictionary of psychoanalysis. Moscow, 1996.

7. Marson P. 25 key books on psychoanalysis. Chelyabinsk 1999.

8. Mid M. Culture and the world of childhood. Selected works. Moscow 1988.

9. Moz L. Psychohistory. Rostov-on-Don, 2000.

10. Sullivan G. Interpersonal theory in psychiatry. St. Petersburg 1999.

11. Freud Z. Three essays on the theory of sexuality. // Psychoanalysis of child sexuality. // Ed. Lukova V.A., St. Petersburg 1998.

12. Schopenhauer A. Selected Works. Rostov-on-Don, 1997.

13. Psychoanalysis of child sexuality / Z. Freud, K. Abraham, K. Jung and others; Ed. V.A. Lukov. St. Petersburg, 1997.

14. Gleitman H. & others. psychology. W. W. Norton & Company Inc. 1999.

W. Norton & Company Inc. 1999.

15. M. J. Eacott, R.A. Crawley. The offset of childhood amnesia: Memory for events that occurred before age 3. / Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 1998 Vol. 127. P. 22-33.

"Infantile amnesia": why we do not remember our childhood | Futurist

Author: Alexandra Alborova | 12 August 2016, 12:45

Most of us do not remember anything from the day we were born - the first steps, first words and impressions up to kindergarten. Our first memories tend to be fragmentary, few in number, and interspersed with significant chronological gaps. The absence of a sufficiently important stage of life in our memory for many decades distressed parents and puzzled psychologists, neurologists and linguists, including the father of psychotherapy, Sigmund Freud, who introduced the concept of "infantile amnesia" more than 100 years ago.

On the one hand, babies absorb new information like sponges. Every second, they form 700 new neural connections, so children quickly master the language and other skills necessary to survive in the human environment. Recent studies show that the development of their intellectual abilities begins even before birth.

But even as adults, we forget information over time if we don't make special efforts to save it. So one explanation for the lack of childhood memories is that childhood amnesia is just the result of a natural forgetting process that nearly all of us experience throughout our lives.

The study of the 19th century German psychologist Hermann Ebbinghaus, who was one of the first to conduct a series of experiments on himself to test the possibilities and limitations of human memory, provided an answer to this assumption. In order to avoid associations with past memories and to study mechanical memory, he developed a method of meaningless syllables - memorizing rows of fictitious syllables of two consonants and one vowel.

Recalling learned words from memory, he introduced a "forgetting curve", which demonstrates the rapid decline in our ability to recall learned material: without additional training, our brain discards half of the new material within an hour, and by day 30 we are left with only 2-3% received information.

The most important conclusion in Ebbinghaus's research: forgetting information is quite natural. It was only necessary to compare the graphs to find out if infant memories fit into it. In the 1980s, scientists did some calculations and found that we store much less information about the period between birth and age six or seven than the memory curve would suggest. This means that the loss of these memories is different from our normal forgetting process.

Interestingly, however, some people have access to earlier memories than others: some may remember events from the age of two, while others may not remember any events from life until the age of seven or eight. On average, fragmentary memories, “pictures”, appear from about the age of 3.5 years. Even more interesting is the fact that the age at which the first memories relate differs among representatives of different cultures and countries, reaching the earliest value of two years.

On average, fragmentary memories, “pictures”, appear from about the age of 3.5 years. Even more interesting is the fact that the age at which the first memories relate differs among representatives of different cultures and countries, reaching the earliest value of two years.

Could this explain gaps in memory? To establish a possible connection between this discrepancy and the phenomenon of "infantile oblivion", psychologist Qi Wang (Qi Wang) from Cornell University collected hundreds of memories of students in Chinese and American colleges. According to stereotypes, American stories were longer, more intricate, and overtly self-centered. The Chinese stories, on the other hand, were shorter and more factual, and, on average, they were six months later than those of the American students.

That more detailed, person-centered memories are much easier to retain and relive has been proven by numerous studies. A little selfishness helps our memory work, as the formation of our point of view fills events with a special meaning.

"There's a difference between 'There were tigers at the zoo' and 'I saw tigers at the zoo, and although they were scary, I had a great time,'" says Robyn Fivush, a psychologist at Emory University, -.

When Qi Wang repeated the experiment with the mothers of these children, she got the same results. It seems that our parents are also to blame for the fact that our childhood memories are hazy.

“Childhood memories are not so important in Eastern cultures, – she says. “If society tells you that these memories matter, you will try to keep them.” The record for the earliest childhood memories belongs to the indigenous people of New Zealand, the Maori, in whose culture the past occupies an important place. Many Maori can remember events from the age of 2.5.

Our culture may also determine how we talk about our memories, and some psychologists argue that they only emerge when we have mastered language.

“Language helps provide the structure or organization of our memories, that is, the narrative. By creating a story, the experience becomes more organized and therefore easier to remember for a long time,” says Fayvush.

Of course, some psychologists doubt that speech plays such a big role in our memory. For example, children who are born deaf and grow up without sign language attribute their earliest memories to the same age as their peers.

Thus, the most likely theory remains that we cannot remember the first years of our lives, because our brain has not developed the necessary functions or "tools" for this. Proof of this can be found in the history of the most famous patient in neuroscience under the initials HM. After an unsuccessful operation to treat epilepsy attacks, the patient's hippocampus, a part of the brain's limbic system also responsible for converting short-term memory into long-term memory, was damaged, and NM could not remember any new events.

However, he was still able to learn other kinds of information, as were babies. When scientists asked him to copy a drawing of a five-pointed star by looking at it in a mirror (which is more difficult than it might seem), his result improved with each new attempt, despite the fact that he did not remember the experience of his practice.

Therefore, it is possible that at an early stage of our growing up, the hippocampus is not sufficiently developed to record enough information about events. Baby rats and monkeys, like humans, add new neurons to the hippocampus during the first few years of life, but fail to form permanent infant memories. It seems that the moment we stop creating new neurons, we discover the ability to retain long-term memories.

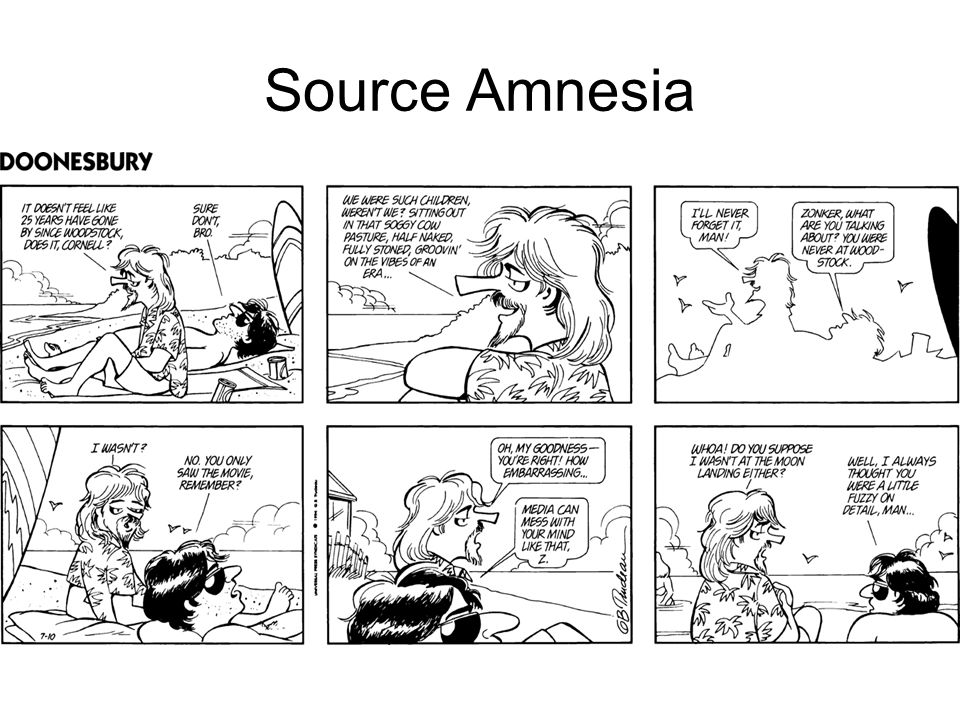

However, do we lose our childhood memories before the hippocampus is fully formed, or are they not recorded at all? Since childhood experiences can continue to influence our behavior after we have forgotten them, some psychologists believe that these memories are still stored somewhere. But even if we tried to restore them, it is hardly possible to speak with confidence about their truth.

But even if we tried to restore them, it is hardly possible to speak with confidence about their truth.

None of us like it when someone says that our memories are not real. Elizabeth Loftus, a psychologist at the University of California, Irvine, has dedicated her career to the phenomenon of false memories. At 19In the 80s, she recruited volunteers for research and personally "implanted" them with false information about their past. Each participant was told about a "traumatic experience" they had as a child at the mall - referring to the words of relatives, they were told how they got lost in it and, with the help of a kind elderly woman, found their family. Almost a third of the subjects believed it, and some of them even recalled vivid details of the "experience." That is, we are sometimes more certain of false memories than real ones.

Even if our memories are based on real events, they were in any case unconsciously further processed by talking about them. Perhaps the mystery is not why we can't remember our childhood, but whether we can trust our childhood memories.