Hpa axis supplements

Super-charging your HPA axis: research-supported therapies

Super-charging your HPA axis Part I: Vitamins and Minerals

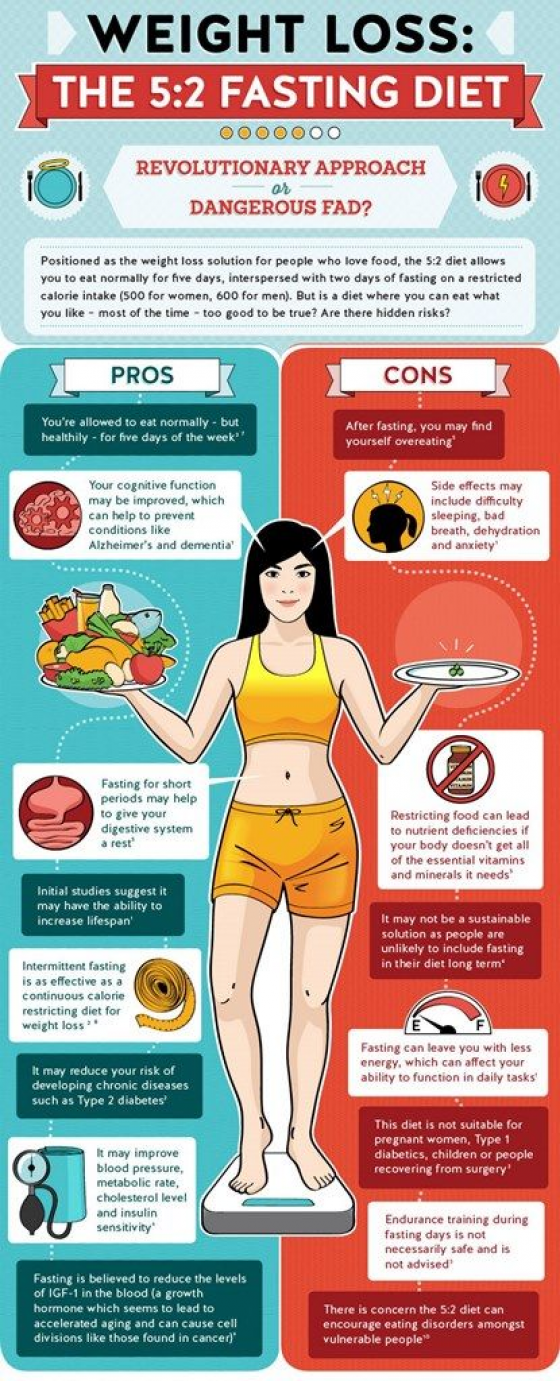

Tweaking our diet and lifestyle can nurture the HPA axis and give us a healthier body.

Key Points

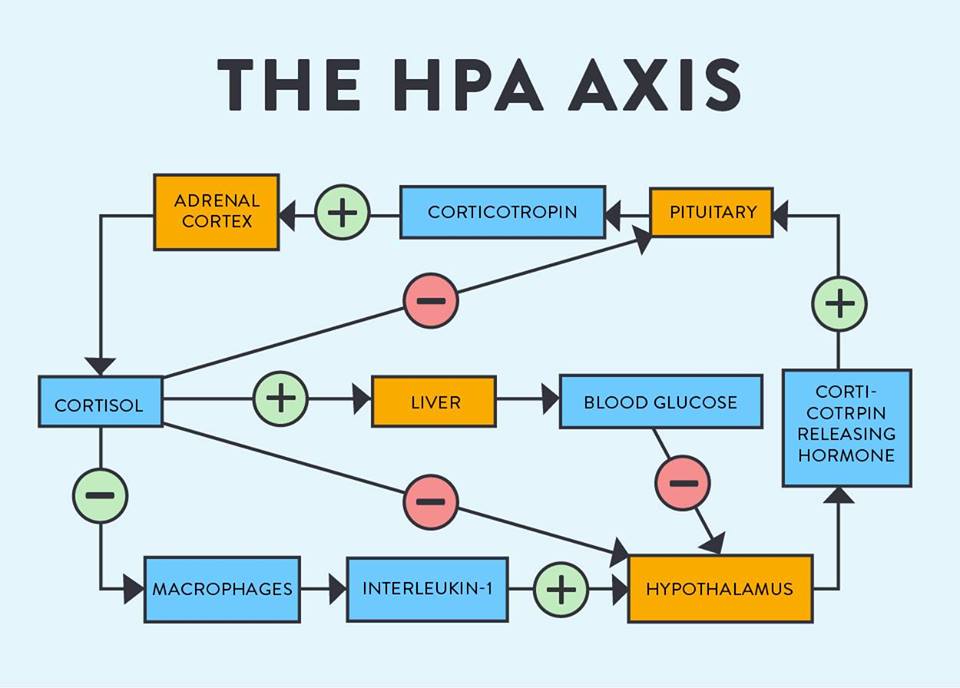

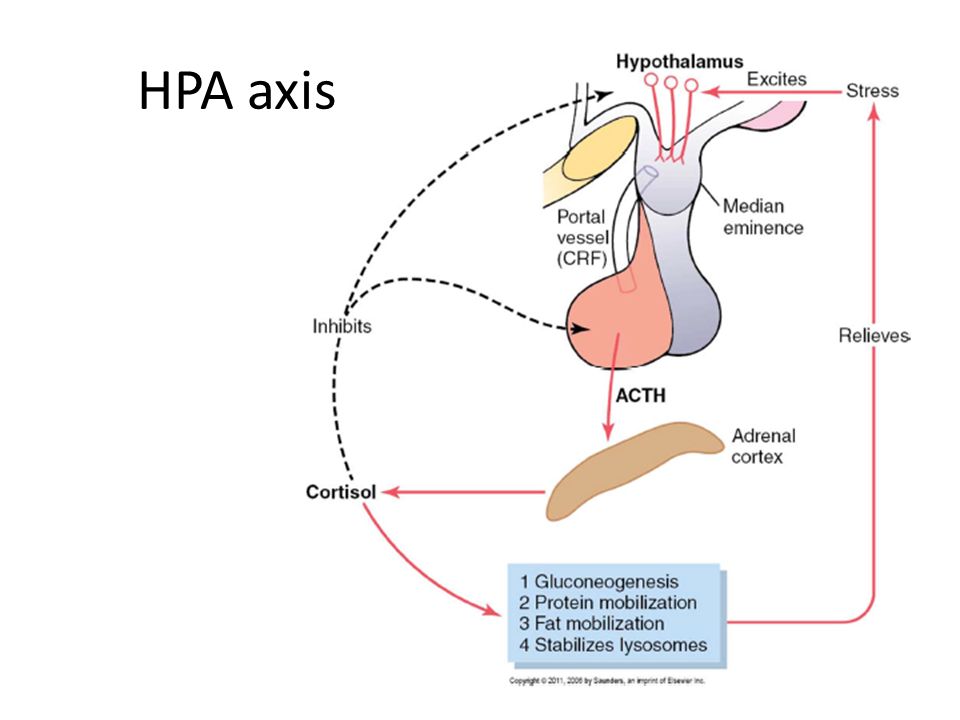

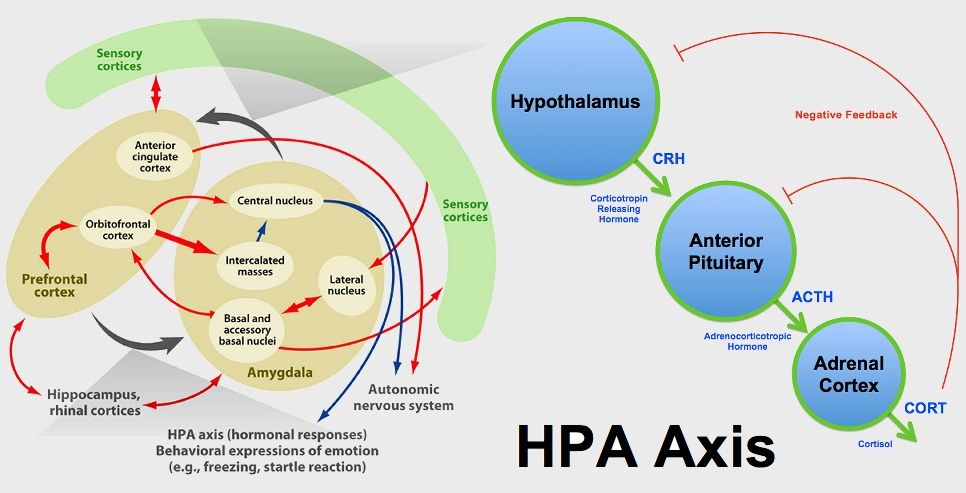

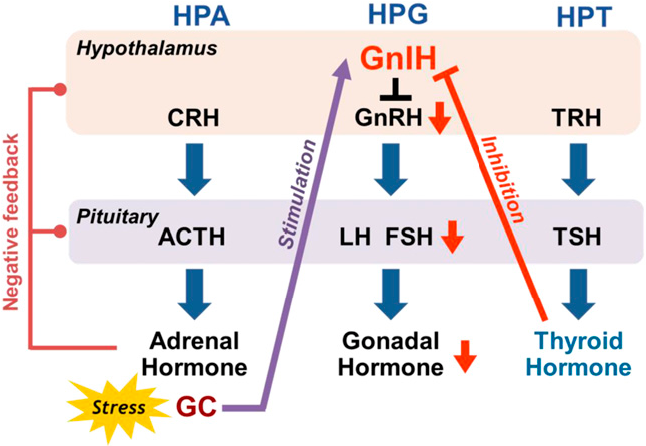

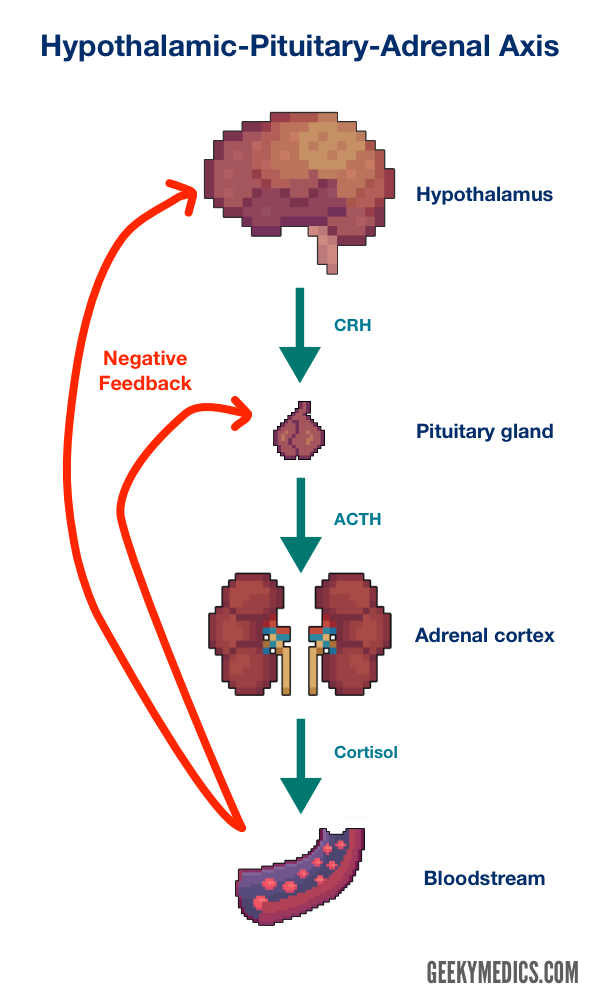

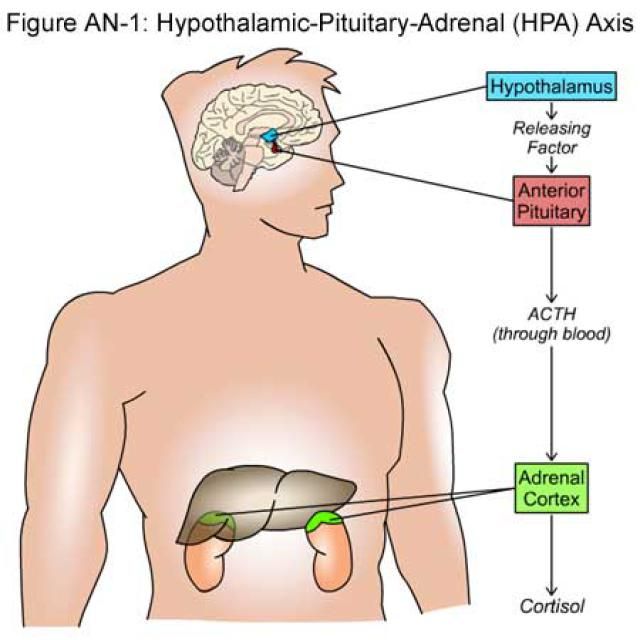

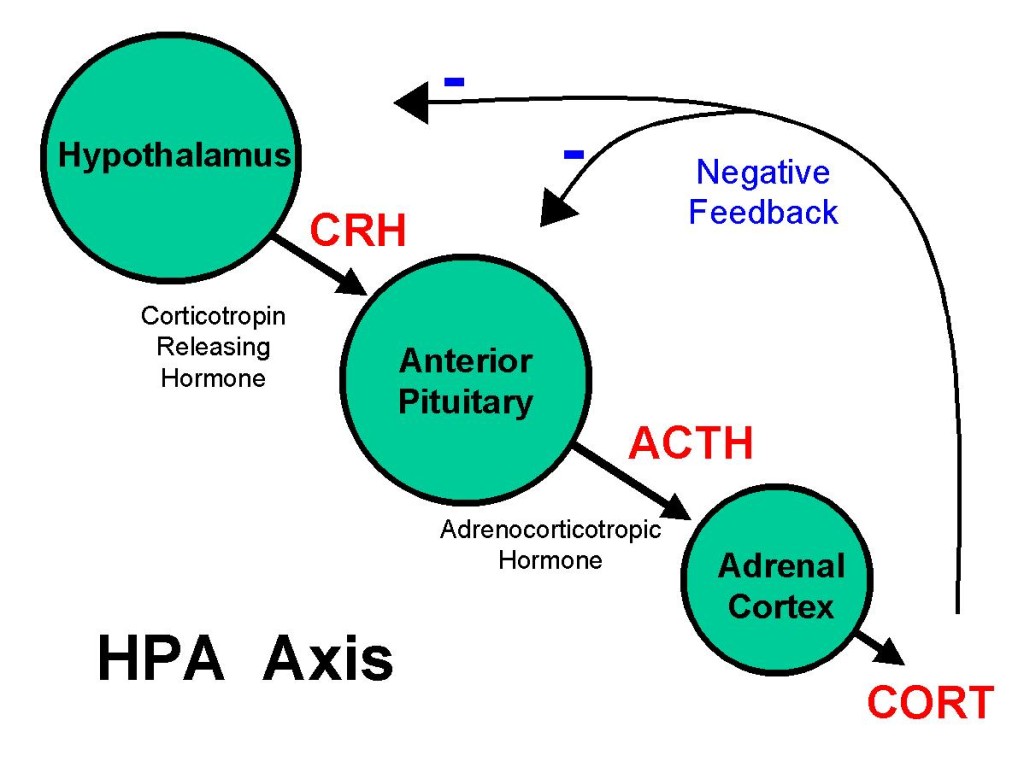

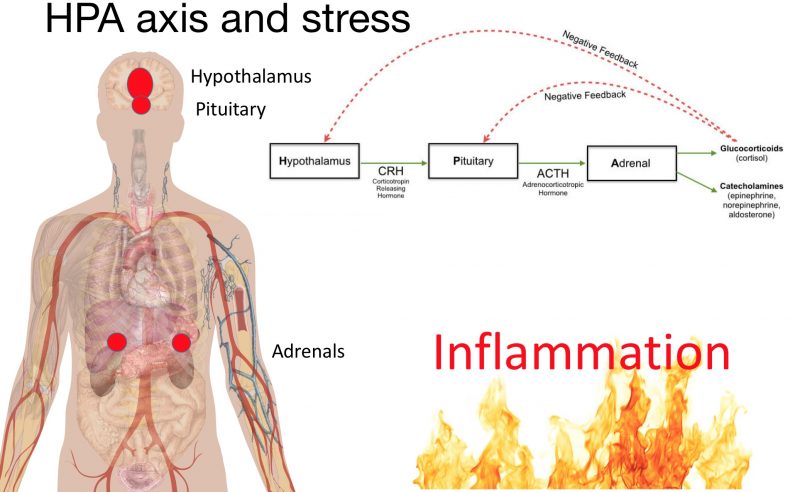

- The HPA axis involves the complex interaction of the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the adrenal glands.

- The HPA axis regulates the release of multiple hormones involves in the body’s response to stress

- Dysfunction of the HPA axis can lead to the development of diseases like to type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease.

- Alterations to the HPA axis can also increase our chances of developing infections, through its role with the body’s immune system.

- There are multiple approaches to sustaining the optimal function of the HPA axis.

- One key approach to maintaining an optimal HPA axis is through the thoughtful use of vitamins and minerals.

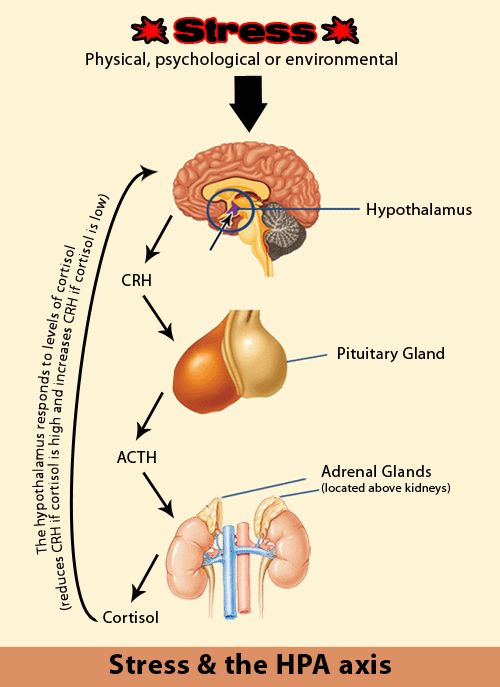

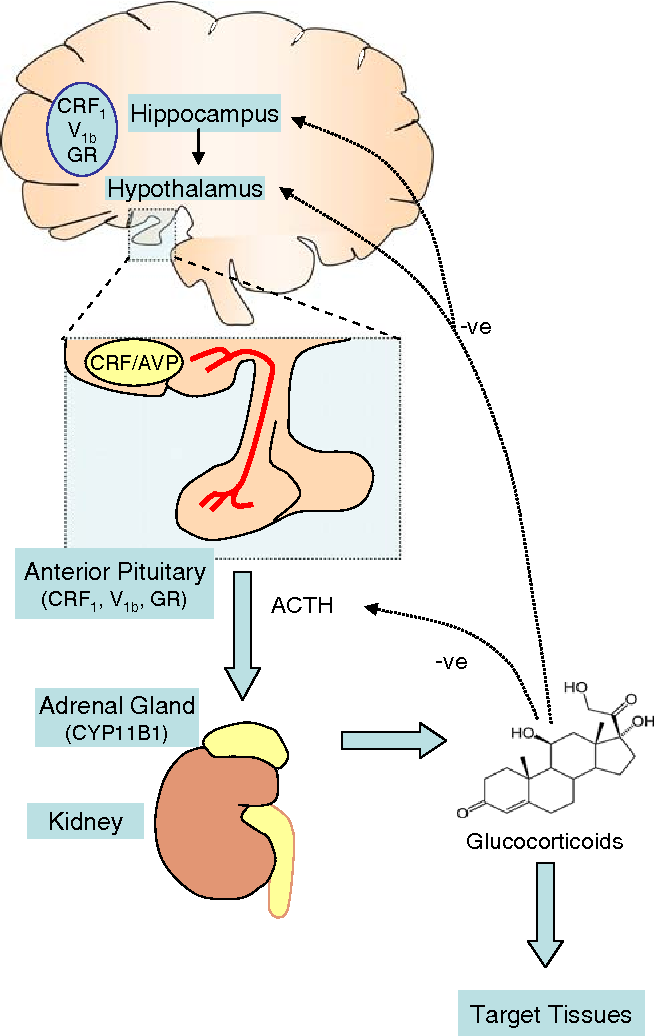

The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is a term used to describe the complex interaction of three major organs in the body: the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland and the adrenal glands. The hypothalamus and pituitary gland can be found just above the brainstem, the part of the brain that connects with the spinal cord. The adrenal glands, in turn, are located on top of the kidneys. These three organs work together in the so-called HPA axis to regulate our body’s response to stress.

HPA axis and stress: the basics

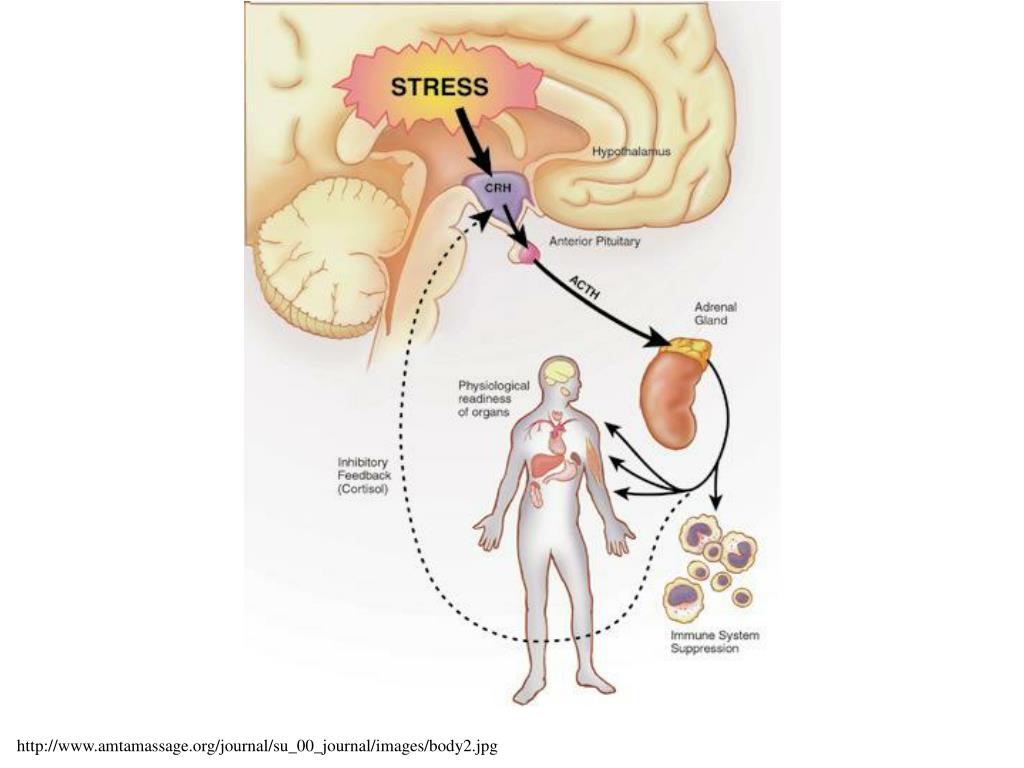

Whenever our body is exposed to stressful factors, the brain is the first organ to respond through the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). This is the part of our autonomic nervous system that oversees the so-called fight or flight response, regulating the function of multiple organs during a stressful event. For example, the SNS system is responsible for the increased heart rate and perspiration we experience when exposed to stress.

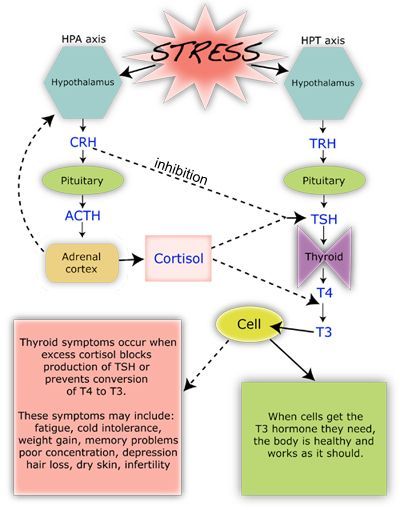

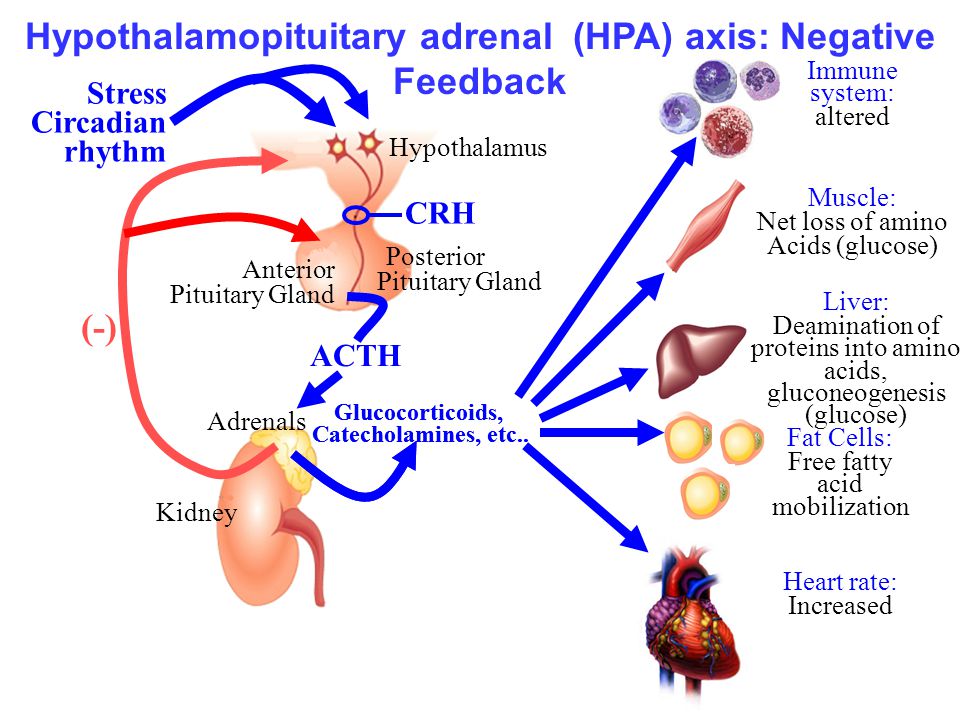

Following a stressful event, the SNS releases the hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine, which activate the HPA axis, starting with the hypothalamus. This organ releases a hormone called corticotropin-releasing hormone or CRH, which keeps the SNS active during the body’s stress response and activates the rest of the HPA axis to produce a cascade of important hormones, such as cortisol, that drive the body’s response to stress.

Once the stressful factor disappears, our body deactivates the stress response, and regulate the production of hormones to normal levels. This is a very important step, because excessive and constant production of hormones like cortisol can have detrimental health effects. For example, chronic elevated cortisol can lead to reduced immune function1 and to an increased chance of infections. Constantly elevated levels of cortisol have also been linked to type 2 diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease2.

Hence, it pays to maintain a healthy HPA axis and there are many ways to optimise your lifestyle and super-charge your body’s response to stress.

Supporting the HPA axis

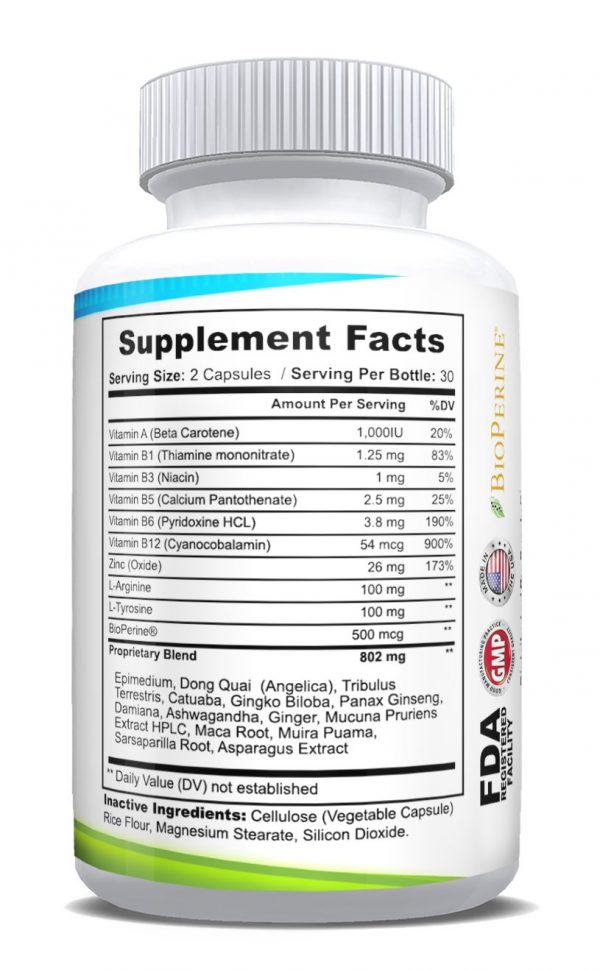

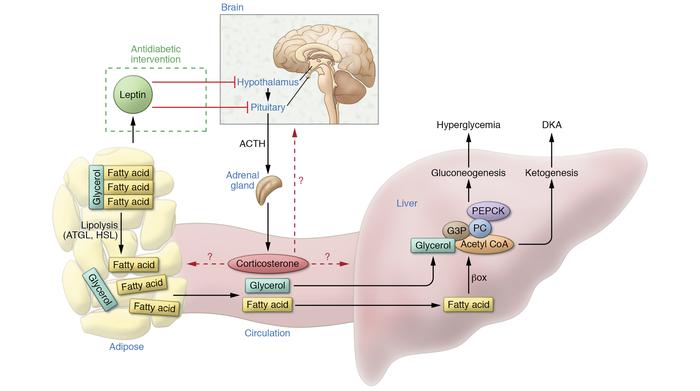

One of the most obvious ways to optimise the function of the HPA axis is to avoid stressors and lead a healthy lifestyle that benefits your brain and body. In addition, there is a wide range of treatment options that help optimise the function of the brain, adrenal glands and help with the regulation of cortisol in specific tissues (Figure 1).

Below, we highlight the best research-backed treatments that improve the function of the HPA axis.

- Vitamins and minerals

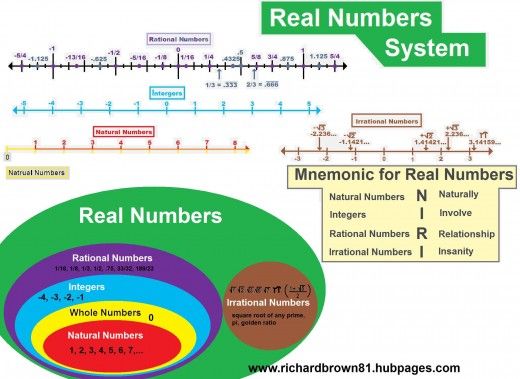

Vitamins and minerals are important co-factors in the biological reactions that produce hormones and neurotransmitters, chemicals that allows communications between neurons. Below we highlight some of the most important vitamins and minerals that are available as dietary supplements and for which there is strong research evidence for their efficacy.

-

- Vitamin C – Also known as ascorbic acid, this is an important cofactor needed for the function of the adrenal glands.

In fact, studies have shown that adrenal glands hold the greatest concentration of vitamin C in their tissues. Vitamin C supplementation prior to intense exercise has been shown to regulate levels of the hormone cortisol, a key hormone produced by the adrenal glands.

In fact, studies have shown that adrenal glands hold the greatest concentration of vitamin C in their tissues. Vitamin C supplementation prior to intense exercise has been shown to regulate levels of the hormone cortisol, a key hormone produced by the adrenal glands. - For example, studies have shown that Vitamin C supplementation before a 90 km race resulted in clear changes in levels of cortisol and inflammatory cytokines (molecules involved with the inflammatory response). Runners that received 1,500 mg/day of Vitamin C for seven days showed significantly lower levels of cortisol and inflammatory cytokines after the race, compared to runners that received either lower levels of Vitamin C or a placebo3-4 (no treatment).

- Similar results were obtained when measuring the effect of Vitamin C in stress levels. One study showed that participants who received 3,000 mg of Vitamin C for two weeks reported reduced levels of stress and blood pressure, relative to the placebo group.

- B Vitamins – This group of vitamins include riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6, folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, inositol, and choline. They are important components needed for the synthesis of adrenal hormones and for the optimal function of neurotransmitters. During episodes of stress, levels of B-vitamins are depleted in the body, and patients experience significant improvement after treatment with B-vitamin supplements.

- Sub-optimal levels of B-vitamins have been shown to contribute to poor metabolic responses to stress5-8.

- A review of multiple studies showed that treatment with B vitamins in combination with other nutrients results in significant reduction of perceived stress, as well as improvement in mild psychiatric symptoms, subclinical anxiety, energy levels9.

- Minerals – Sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, and zinc are among the most important minerals known to affect the function of the HPA axis.

- Deficiencies on these minerals can result inf alterations in neurotransmitter and HPA axis dysfunctions10-12.

- Magnesium supplementation has been shown to effectively improve sleep, metabolic function and measures of fatigue and energy in people with stress and HPA axis-related dysfunctions13-18.

- Vitamin C – Also known as ascorbic acid, this is an important cofactor needed for the function of the adrenal glands.

-

According to the 2011-2012 Australian health survey, one in three people aged two years and over did not consume enough magnesium. Likewise, the same survey found that more than half of the Australian population over two years of age did not consume adequate levels of calcium.

There is extensive research supporting the important role of vitamins and minerals in the maintenance of an optimal HPA axis. Following a healthy diet rich in these nutrients or complementing your diet with supplements is a solid approach to improving your health. Consulting with your functional medicine practitioner is the first step to find your personalised pathway to health.

HEAD TO ARTICLE 6

References

- Bellavance MA, Rivest S. The HPA–immune axis and the immunomodulatory actions of glucocorticoids in the brain. Frontiers in immunology. 2014 Mar 31;5:136. Read it!

- Chrousos GP. Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature reviews endocrinology. 2009 Jul;5(7):374. Read it!

- Peters EM, Anderson R, Nieman DC, Fickl H, Jogessar V. Vitamin C supplementation attenuates the increases in circulating cortisol, adrenaline and anti-inflammatory polypeptides following ultramarathon running. International journal of sports medicine. 2001 Oct;22(07):537-43. Read it!

- Nieman DC, Peters EM, Henson DA, Nevines EI, Thompson MM. Influence of vitamin C supplementation on cytokine changes following an ultramarathon. Journal of Interferon & Cytokine Research. 2000 Nov 1;20(11):1029-35. Read it!

- Schwabedal PE, Pietrzik K, Wittkowski W.

Pantothenic acid deficiency as a factor contributing to the development of hypertension. Cardiology. 1985;72(Suppl. 1):187-9. Read it!

Pantothenic acid deficiency as a factor contributing to the development of hypertension. Cardiology. 1985;72(Suppl. 1):187-9. Read it! - Tarasov IU, Sheĭbak VM, Moĭseenok AG. Adrenal cortex functional activity in pantothenate deficiency and the administration of the vitamin or its derivatives. Voprosy pitaniia. 1985(4):51-4. Read it!

- Shor-Posner G, Feaster D, Blaney NT, Rocca H, Mantero-Atienza E, Szapocznik J, Eisdorfer C, Goodkin K, Baum MK. Impact of vitamin B6 status on psychological distress in a longitudinal study of HIV-1 infection. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 1994 Sep;24(3):209-22. Read it!

- McCarty MF. High-dose pyridoxine as an’anti-stress’ strategy. Medical hypotheses. 2000 May 1;54(5):803-7. Read it!

- Long SJ, Benton D. Effects of vitamin and mineral supplementation on stress, mild psychiatric symptoms, and mood in nonclinical samples: a meta-analysis.

Psychosomatic medicine. 2013 Feb 1;75(2):144-53. Read it!

Psychosomatic medicine. 2013 Feb 1;75(2):144-53. Read it! - Whittle N, Li L, Chen WQ, Yang JW, Sartori SB, Lubec G, Singewald N. Changes in brain protein expression are linked to magnesium restriction-induced depression-like behavior. Amino Acids. 2011 Apr 1;40(4):1231-48. Read it!

- Sartori SB, Whittle N, Hetzenauer A, Singewald N. Magnesium deficiency induces anxiety and HPA axis dysregulation: modulation by therapeutic drug treatment. Neuropharmacology. 2012 Jan 1;62(1):304-12. Read it!

- Takeda A, Tamano H. Zinc signaling through glucocorticoid and glutamate signaling in stressful circumstances. Journal of neuroscience research. 2010 Nov 1;88(14):3002-10. Read it!

- Nielsen FH, Johnson LK, Zeng H. Magnesium supplementation improves indicators of low magnesium status and inflammatory stress in adults older than 51 years with poor quality sleep. Read it!

- Reinstatler KM, Woolf B.

Treatment of Sleep Disturbances in Nursing Home Patients: Practical Management Strategies. Psychiatric Annals. 2018 Jun 12;48(6):271-8. Read it!

Treatment of Sleep Disturbances in Nursing Home Patients: Practical Management Strategies. Psychiatric Annals. 2018 Jun 12;48(6):271-8. Read it! - Murck H, Steiger A. Mg2+ reduces ACTH secretion and enhances spindle power without changing delta power during sleep in men–possible therapeutic implications. Psychopharmacology. 1998 Jun 1;137(3):247-52. Read it!

- Boyle NB, Lawton C, Dye L. The effects of magnesium supplementation on subjective anxiety and stress—a systematic review. Nutrients. 2017 May;9(5):429. Read it!

- Tanabe K, Yamamoto A, Suzuki N, Osada N, Yokoyama Y, Samejima H, Seki A, Oya M, Murabayashi T, Nakayama M, Yamamoto M. Efficacy of oral magnesium administration on decreased exercise tolerance in a state of chronic sleep deprivation. Japanese circulation journal. 1998;62(5):341-6. Read it!

- Kirkland AE, Sarlo GL, Holton KF. The role of magnesium in neurological disorders.

Nutrients. 2018 Jun;10(6):730. Read it!

Nutrients. 2018 Jun;10(6):730. Read it!

Why HPA Axis Dysfunction May Be More Important Than Gut Health…

Ask any functional medicine doctor where chronic disease begins, and you’ll typically hear one consistent answer: in the gut!

So what the heck do I mean by stating that HPA axis dysfunction (whatever THAT is) may be even more important?

I realize this is a bold statement, and may even sound contrary to what I’ve said before. Let me be clear, I firmly believe, based on my own experience and emerging research, that gut health is a leading factor in the genesis of chronic disease. However…

…the more patients I treat with complex, chronic conditions the more I’ve realized we have to dig a little deeper. We have to ask more questions, like: what’s causing or contributing to the gut health issues? What’s causing the chronic inflammation? Why aren’t people getting better who are doing “all the right things”?

The conclusion that some of my most respected colleagues and I have come to is: it’s stress.

Specifically, chronic stress that causes what’s known as Hypothalamus Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) axis dysfunction. Or it’s better known (but less accurate names): adrenal fatigue, adrenal burnout, or adrenal insufficiency).

If you’re suffering from a diagnosis or symptoms that just won’t go away even though you’re doing “all the right things,” listen up! This could very well be the missing link to getting your life back.

What Exactly is HPA Axis Dysfunction, aka: Adrenal Fatigue?

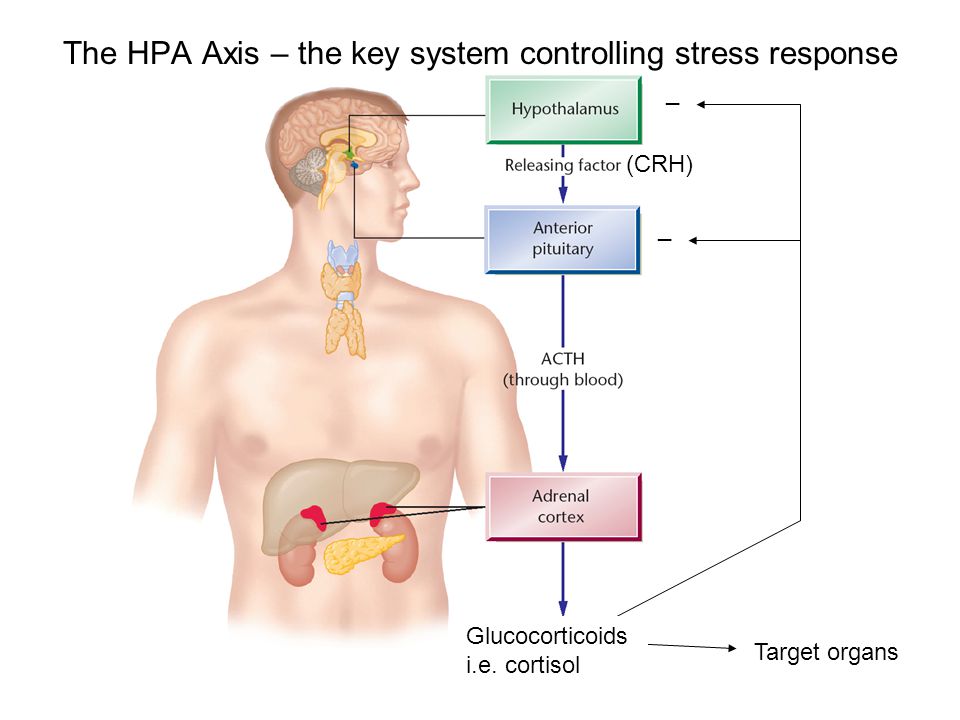

The “HPA” in HPA axis dysfunction refers to your hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal glands. Which are all part of your endocrine/hormonal system and communicate through what’s known as the HPA axis.

Your hypothalamus, located at the base of your brain, acts as a traffic cop for the rest of your endocrine system, sending communication to the pituitary gland, which then signals the adrenals, thyroid, and ovaries to secrete hormones.

The terms “adrenal fatigue” and “adrenal burnout” are considered myths by most endocrinologists1, and though many people suffer with real symptoms, the names are not entirely accurate. The adrenal glands (typically) don’t just burn out or lose function. Rather, the body becomes less sensitive to their hormones over time.

The adrenal glands (typically) don’t just burn out or lose function. Rather, the body becomes less sensitive to their hormones over time.

I think it’s important to note, however, that sometimes the adrenals do burn out… adrenal insufficiency is a recognized diagnosis characterized by lack of cortisol and other hormones. The most common cause is an autoimmune disease called Addison’s.

So What Causes HPA Axis Dysfunction?

In a word: stress…specifically, chronic stress. Just like in relationships, when our bodies are stressed, communication starts to break down.2

Here’s how that works:3

When you’re under stress, your hypothalamus releases Corticotropin Releasing Hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary to release Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) which triggers the adrenal glands to release the stress hormone cortisol.

This triggers our fight or flight response, which is essential for dealing with acute periods of stress…like if you were chased by a wild animal or had to rescue your child from a sudden fall.

However, since cortisol triggers a release of glucose to bolster your energy, while suppressing your digestive system, immune system, reproductive system, and insulin production, it’s not sustainable long-term.

The tricky thing about chronic stress is the longer we’ve been “surviving” in this state, the more “normal” it feels to always feel tense, aggravated, on-edge, hyper, wired and tired, etc.

In fact, being “so stressed”, “exhausted”, and “busy, busy, busy!”, is often considered a sign of success. Which is unfortunate because it comes at the expense of our health, healing, and happiness.

I myself have had to learn to temper my ambitions on several occasions to heal from chronic disease, get through a tough emotional time, and/or avoid defaulting into that “chronic stress culture.” So I know the struggle we all face…especially as we become parents, build our careers, start businesses, try to save the world, etc.

The point is, while fight or flight is a God-send for getting you through acute phases of stress, you cannot exist in that state for long without experiencing body breakdown.

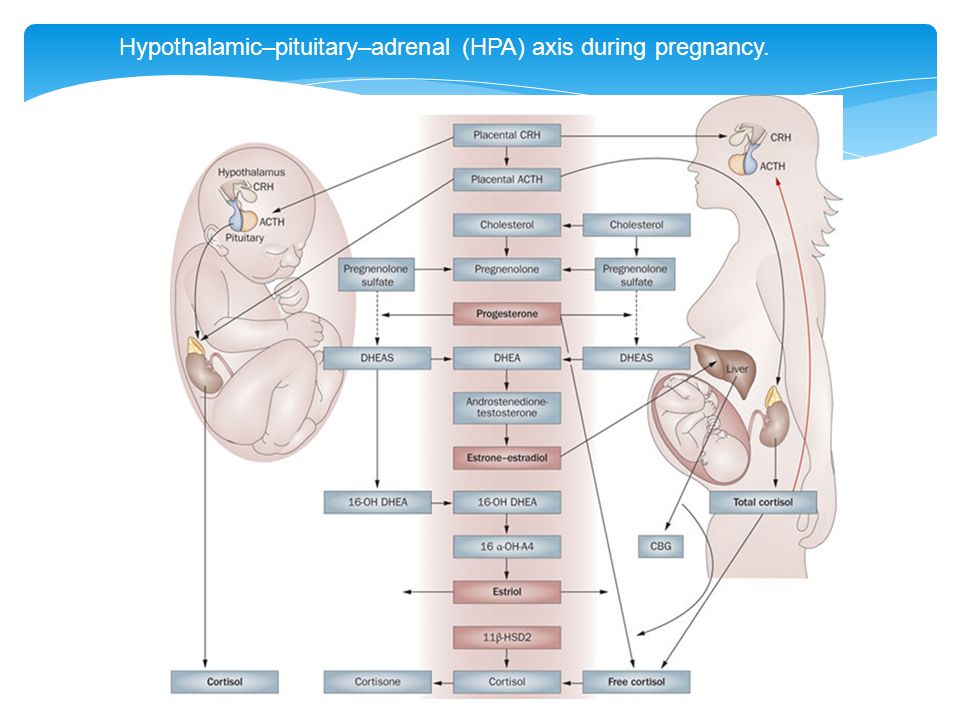

It’s also worth mentioning that maternal stress has been shown to predispose babies to HPA axis dysfunction.4, 5. So if you’re pregnant or thinking of becoming pregnant, NOW is a really good time to join the counter-chronic-stress-culture movement.

Before we go on, I want to emphasize an important point that’s often left out of discussions on chronic stress/HPA axis dysfunction: the mind-body connection.

There are physical and mental/emotional sources of chronic stress. Some of which are unavoidable, such as an acute or chronic disease, a recent injury, trauma, a new baby, the loss of a loved one, or a toxic marriage/work environment.

If you’re experiencing any of these (and we all do at some point) I urge you not to give up on yourself. Even during times of unavoidable stress, you can take steps to protect yourself even if you can’t fully escape the circumstances. We’ll look at some proven ways you can accomplish this coming up.

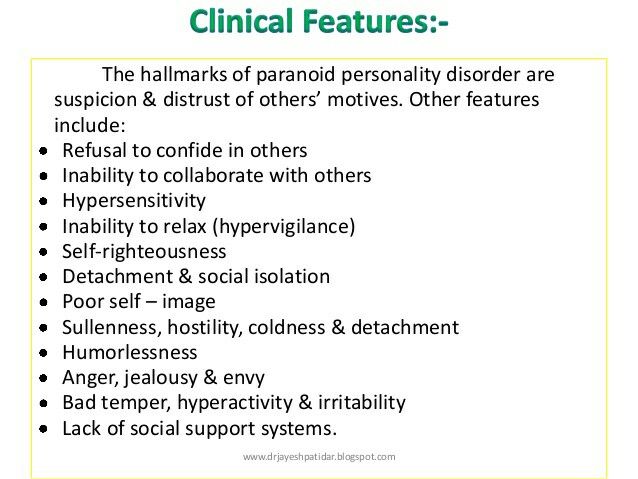

Symptoms of HPA Axis Dysfunction

Since HPA axis dysfunction causes elevated cortisol and low hormones levels across the board, it can result in the following symptoms:6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

- Anxiety

- Autoimmune disease

- Blood pressure imbalance

- Blood sugar imbalance

- Brain fog

- Chronic Fatigue Syndrome

- Depression

- Digestive disorders/Gut health issues

- Fatigue (often extreme, like you can’t get enough sleep)

- Infertility

- Inflammation

- Insomnia

- Low immunity

- Low libido

- Mood swings

- PMS

- PTSD

- Seasonal affective disorder

- Inflammatory skin conditions

- Slow healing

- Thinning hair

- Thyroid issues

- Trouble with focus and concentration

- Weight gain around the midsection and upper back

HPA Axis Dysfunction Also Affects The Vagal Nerve, A Critical Player In The Gut-brain Connection

What is the vagal nerve aka: vagus nerve? It’s the longest cranial nerve that meanders from your brain all the way to your gut, interacting with various organs and systems in its path.

This tree-like nerve works like a super-highway, shuttling information from brain to gut and everything in between. The vagus nerve is also the main component of your parasympathetic nervous system—which controls your rest-and-digest response and oversees other critical functions like mood, heart rate, and immune response.14

Unfortunately, chronic stress and HPA axis dysfunction can cause your vagal nerve to lose its tone over time. This creates a cascade of issues that can affect things like digestion, stress response, heart health, inflammatory response, your ability to relax, mental health, and others.

Fortunately, there’s been some great research into tools and lifestyle practices that will re-tone your vagus nerve and help reset your stress response, gut health, and help with HPA axis dysfunction…which we’ll explore next.

How To Heal And Deal With HPA Axis Dysfunction And Get A Handle On Chronic Stress

Let’s face it, life can get stressful. And I see this as an even bigger issue in patients with childhood trauma.

And I see this as an even bigger issue in patients with childhood trauma.

So let’s start working on it, shall we? Here are 13 ways to heal HPA axis dysfunction.

- Get more quality and quantity of sleep—since HPA axis dysfunction can make you feel tired all the time, it can be hard to tell if you actually got a good night’s rest. To track this, I recommend (and use) an Oura ring which gives me data on my quantity and quality of sleep. Better sleep is absolutely essential to restoring optimal HPA axis function,15 so aim for 8-10 hours a night while you’re healing. And if you have trouble sleeping (because it can be a vicious cycle) talk to your doctor about adding melatonin, ashwagandha, l-theanine, magnesium, or other natural sleep aids.

- Just the right amount of exercise—stressed out adrenals do not like strenuous, lengthy workouts like marathons. However, exercise is important because it can help regulate cortisol, insulin, and glucose levels while boosting your mood and promoting sleep.

Which means, you’ll have to find the right balance for you, and you have full license to tone down your workout a bit if you’re overtraining! I’ve become a Peloton fan post-pandemic, but yoga and walking are excellent for HPA patients. One of my favorite video platforms is Citizen Yoga on Demand.

Which means, you’ll have to find the right balance for you, and you have full license to tone down your workout a bit if you’re overtraining! I’ve become a Peloton fan post-pandemic, but yoga and walking are excellent for HPA patients. One of my favorite video platforms is Citizen Yoga on Demand. - Spending time in nature and disconnecting from technology—there is a ton of research to back up the dirt-cheap effectiveness of spending time outdoors to reduce stress. For example, the simple act of “grounding” aka: “earthing”, which means having direct contact with the earth via gardening, walking around barefoot, swimming in natural water, or using a grounding mat (more on that in the next point) significantly reduces cortisol levels and improves vagal nerve tone.16 Additional research shows that just 10 minutes a day of time spent in greenspace can be enough to reduce stress and enhance your well-being.17

- Meditation—meditation has been proven to help improve vagal nerve tone, reduce inflammation, and reduce stress.

18 Plus these days, it’s really easy to learn how. Some of my favorite resources include: Muse Meditation Headband, HeartMath (heart rate variability training) and my newest obsession the PEMF Mat.

18 Plus these days, it’s really easy to learn how. Some of my favorite resources include: Muse Meditation Headband, HeartMath (heart rate variability training) and my newest obsession the PEMF Mat. - Pulsed Electro-Magnetic Field (PEMF)—works by sending a low-level frequency throughout your body, similar to the Earth’s natural electrical frequency that you’d experience from walking outdoors barefoot, which recharges your cells and organs while helping reset your stress response. It also uses infrared technology to reduce pain and promote relaxation, and releases antioxidant-rich negative ions for even greater healing benefits. I use my PEMF Mat daily, and even more often when stress is really high — because it helps! Learn all about it here (plus use DRMAREN75 for $75 off!).

- Breathwork—slow, deep breathing stimulates activity of the vagal nerve, promotes better sleep, and activates our parasympathetic nervous system response.19 And you can do it from anywhere! I love doing the 4-7-8 breath and focusing on longer exhalations vs.

inhalations. But any type of breathwork including Oujai breath, belly breathing, etc. will benefit your HPA axis.

inhalations. But any type of breathwork including Oujai breath, belly breathing, etc. will benefit your HPA axis. - Sex and orgasms help too—chronic stress can really mess with your libido, but sex is also ahhh-mazing for stress relief, mental health, parasymptathetic nervous system response, heart rate variability, hormonal balance in some cases, and better immunity. All of which have a positive impact on HPA axis function and stress response.20

- Adaptogens—these powerful and ancient herbs have been used for centuries to help people adapt to stress and increase energy. And several studies have shown that they positively impact the immune-neuro-endocrine-system and HPA axis.21 In other words: they are one of your best tools to help mediate those inevitable, stressful times in life! My favorites are Ashwagandha and Rhodiola Rosea, but other adaptogens include ginseng, schisandra, goji berry, cordyceps, licorice, turmeric, and Tulsi (Holy Basil).

- Addressing underlying health issues—remember stress can be caused by physical and environmental issues too (known or unknown), especially those related to inflammation and toxins. So be sure you’re working with a functional medicine physician to help you diagnose and treat these at the root cause.

- Therapy—in cases of trauma, grief, or any mental/emotional pain that won’t go away, I recommend seeking the help of a qualified therapist. If you’re lucky, you may even find one trained in Functional Medicine as “holistic psychology” is becoming more popular. You can always check out: ifm.org/findapractitioner to search for one in your area.

- Dynamic Neural Retraining System (DNRS)—this is a really cool training program that helps get to the root cause of an overactive stress response by retraining your brain. It does this using a combination of mindfulness, meditation, and specific brain exercises that help to rewire the limbic system.

The limbic system is intimately connected to your endocrine and autonomic nervous system and can become dysfunctional due to trauma—physical, mental, or emotional.

The limbic system is intimately connected to your endocrine and autonomic nervous system and can become dysfunctional due to trauma—physical, mental, or emotional. - Dance—any type of dancing, whether solo, with a partner, or a group of friends is excellent for reducing stress and increasing those lovely feel-good endorphins.22

- Alone time—taking time to relax and nourish your creative side, especially if you’re a busy mom or dad, is essential to healing from chronic stress. This could mean reading, cooking, drinking a cup of tea, taking a walk, whatever makes you feel restored. Make sure you take some time every day to refill your cup. I love to wake up early before my kids and enjoy my toxin-free coffee in peace.

- Community—did you know the effects of loneliness or social isolation has been compared to smoking a pack of cigarettes a day? That’s partly because feeling lonely causes an increased activation of the HPA Axis.

23 The solution? Get involved in a community. I know it’s easier said than done sometimes, especially post-COVID, but it is extremely important to surround yourself with people who care. This could mean joining a Meetup group of some sort, taking a course, volunteering, joining a church, temple, mosque, etc. reconnecting with old friends, joining a moms or dads club, starting a book club, or hosting a party! Whatever speaks to you, make sure to make some personal connections regularly for the sake of your health and happiness.

23 The solution? Get involved in a community. I know it’s easier said than done sometimes, especially post-COVID, but it is extremely important to surround yourself with people who care. This could mean joining a Meetup group of some sort, taking a course, volunteering, joining a church, temple, mosque, etc. reconnecting with old friends, joining a moms or dads club, starting a book club, or hosting a party! Whatever speaks to you, make sure to make some personal connections regularly for the sake of your health and happiness.

You Have The Tools, Here’s How To Get Started

Healing HPA axis dysfunction is possible and essential if you want to fully recover from any type of chronic disease.

As I tell my patients, you can take all the best supplements and eat all the right foods in the world, but if your HPA axis is off and you’re chronically stressed out, you will not heal completely.

Sure, you may heal enough to feel better, get your lab markers within range, and get rid of your symptoms for a period of time. But, without addressing the chronic stress piece those pesky symptoms, or new ones, will crop up again. Annoying, but true.

But, without addressing the chronic stress piece those pesky symptoms, or new ones, will crop up again. Annoying, but true.

Healing won’t happen overnight, and the process is different for everyone based on their individual lifestyle, health presentation, history, mental health, life circumstances, etc. But you can do it!

The first step is to choose 2 or 3 of those lifestyle recommendations listed above and commit to them. Even if it’s as simple as spending 10 minutes in nature every day and getting more sleep, those small changes can make a dramatic impact on your HPA axis function.

The next step would be to find a functional medicine physician well-versed in HPA axis dysfunction, to help you get to the next level of healing. That typically means taking a thorough health history, running lab work to check your hormonal/adrenal status, search for underlying infections and nutrient deficiencies, and create a custom program to help you heal and get on with your life.

If you’re located in Colorado, Michigan, or Texas I’d love to see if I can help. Click here to learn more about my approach to functional medicine and how to become a patient.

Click here to learn more about my approach to functional medicine and how to become a patient.

Not in my tri-state area? I’d still love to keep in touch (as I will likely broaden my scope of practice in the future). Click here to join the mailing list and/or join the fun on Instagram @drchristinemaren and @heymami.life.

Post Views: 0

Sources

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27557747/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3860380/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/cphy.c150015/figures

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20550950/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16123758/

- https://www.nature.com/articles/s41380-019-0501-6

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3181830/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541120/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30621143/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18488870/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26356039/

- https://www.

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5979578/

ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5979578/ - https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30342071/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5859128/

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25905298/

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3344267

- https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02942/full

- https://www.biologicalpsychiatryjournal.com/article/S0006-3223%2816%2900079-2/fulltext

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25234581/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01677.x#ss41

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6240259/

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334281938_DANCING_TO_RESIST_REDUCE_AND_ESCAPE_STRESS

- https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29972603/

It has long been known that pharmacological treatment with antidepressants does not produce at least a partial response in about one-third of patients with recurrent depression, and remission is achieved in about 30% of patients. This is called therapeutically resistant depression (TRD). The lack of remission and lack of response to adequate treatment for depressive illnesses is also referred to as "refractory depression". More recently, Rush et al. introduced the designation "intractable depression" (DTD). The burden of TRD increases exponentially, the longer it persists, the higher the risk of impairment of functional and social functioning, the huge loss in quality of life and the significant risk of somatic morbidity and the risk of suicide.

This is called therapeutically resistant depression (TRD). The lack of remission and lack of response to adequate treatment for depressive illnesses is also referred to as "refractory depression". More recently, Rush et al. introduced the designation "intractable depression" (DTD). The burden of TRD increases exponentially, the longer it persists, the higher the risk of impairment of functional and social functioning, the huge loss in quality of life and the significant risk of somatic morbidity and the risk of suicide.

Causes of treatment-resistant depression

Psychiatrists and researchers are making intense efforts to unravel the causes of TRD (or DTD), but so far with limited success. On the positive side, numerous biological and non-biological risk factors and risk factors have been identified that need to be considered when countering TRD. Clinical variables that may distinguish patients with TRD from patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) or recurrent depression (ICD-10) responding to treatment include psychiatric comorbidities (eg, anxiety and panic disorder and social phobia), personality disorder, suicidality, psychosis, substance abuse and dependence, early age of onset, more hospitalizations, and recurrent episodes. A number of comorbidities, in particular endocrinopathies, cardiovascular disease, neurological disease, and vitamin deficiencies, can also contribute to the development of TRD. Structural changes in neurons and loss of synapses associated with stress and sleep disturbances alter the density and function of 5-HT receptors and transporters and may cause cognitive decline and emotional dysfunction. Last but not least, the role of stress must be seriously considered in the management of patients with TRD. Excessive and prolonged stress can lead to structural changes in neurons that contribute to the shrinkage of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus seen in depressed patients. Chronic stress causes dendritic atrophy of neurons within the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex.

A number of comorbidities, in particular endocrinopathies, cardiovascular disease, neurological disease, and vitamin deficiencies, can also contribute to the development of TRD. Structural changes in neurons and loss of synapses associated with stress and sleep disturbances alter the density and function of 5-HT receptors and transporters and may cause cognitive decline and emotional dysfunction. Last but not least, the role of stress must be seriously considered in the management of patients with TRD. Excessive and prolonged stress can lead to structural changes in neurons that contribute to the shrinkage of the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus seen in depressed patients. Chronic stress causes dendritic atrophy of neurons within the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex.

A recent meta-analysis showed that patients who experienced childhood trauma and therefore potentially chronic activation of the HPA axis had a lower overall response to treatment.

Genetic studies

To date, the most promising TRD-associated genes encode the serotonin transporter SLC6A4, the presynaptic serotonin autoreceptor 5-HTR1A, catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT), the brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and transcription factor CREB1.

Hormonal causes of persistent depression

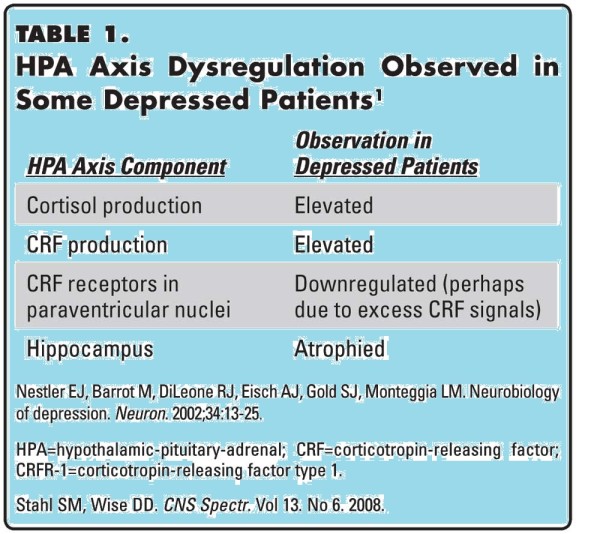

Numerous studies and recent meta-analyses evaluating the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and depression have shown that depression is associated with elevated cortisol levels and that patients with MDD have a reduced cortisol awakening response (CAR ). Chronically elevated cortisol levels are associated with worse outcomes from MDD treatment, leading some patients to be characterized as “treatment resistant. Studies show that hypercortisolemia is associated with impaired cognitive function and is a risk factor for subsequent MDD in patients at risk. One study examined the detrimental effects of synthetic glucocorticoid treatment and its association with mental illness, emphasizing the importance of recognizing this important pathway when considering the label "treatment-resistant depression". This study of over 350,000 primary care patients found that even when the underlying disease was under control, patients treated with synthetic glucocorticoids were 7 times more likely to attempt suicide and twice as likely to develop persistent depression.

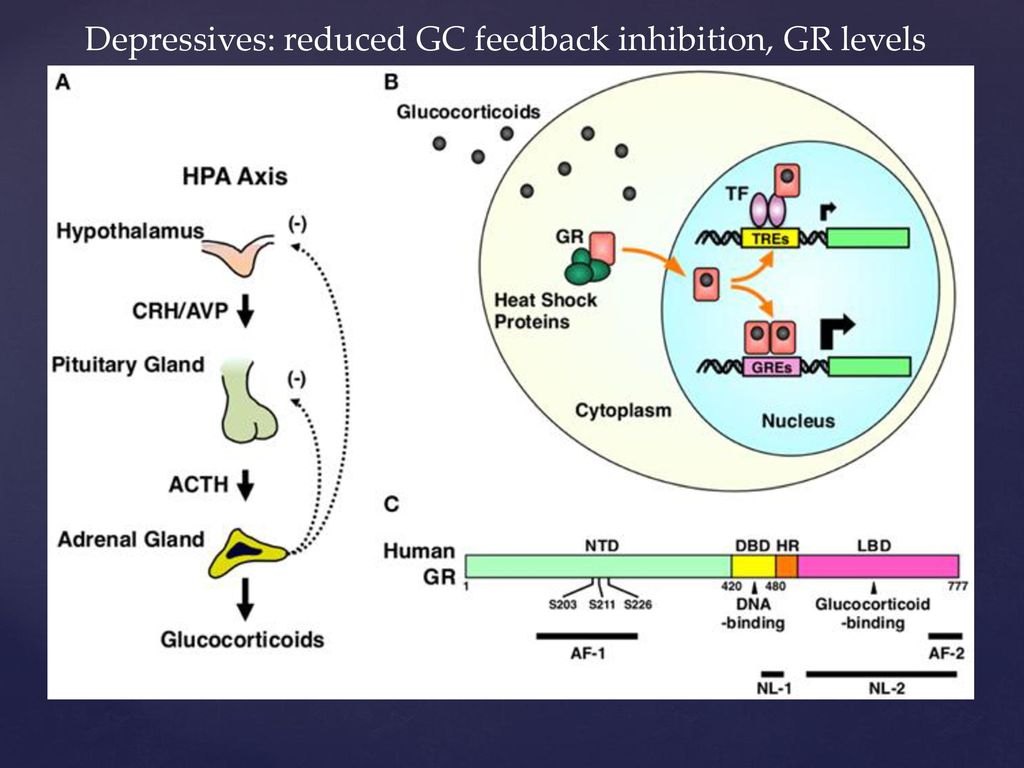

The HPA axis is activated in the presence of a perceived stressor, followed by the release of corticotropic releasing hormone (CRH) and adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the adrenal glands to release cortisol. Cortisol is essential for boosting our energy levels to properly deal with stressful situations. Cortisol raises blood sugar levels by activating gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. Among the most important aspects of the HPA axis that is involved in MDD is the negative feedback loop in which cortisol begins to act as a suppressor of the HPA axis once it is transported back to the hypothalamus and pituitary via the bloodstream. Within this negative feedback loop, cortisol binds to the mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptors (MR and GR), inhibiting the release of CRH and ACTH. Over time, this also reduces the amount of systemic cortisol release and the system returns to homeostasis when the stressor is gone. In other non-psychiatric illnesses such as Cushing's disease or Addison's disease, in which there is hypercortisolemia and hypocortisolemia, respectively, patients experience severe symptoms, including psychopathological syndromes requiring surgical and/or pharmacological treatment.

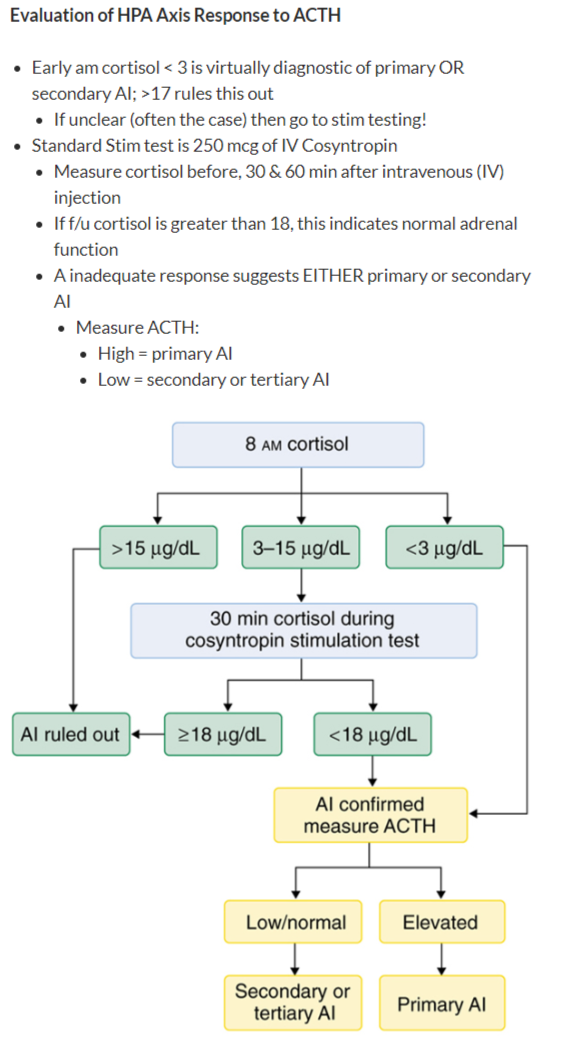

In other non-psychiatric conditions, such as Cushing's disease or Addison's disease, which present with hypercortisolemia and hypocortisolemia, respectively, patients experience severe symptoms, including psychiatric symptoms requiring surgical and/or medical treatment. The normal stress response to a short-term stressor consists of an adequate release of cortisol and eventually a recovery to homeostatic levels of cortisol once it has been eliminated. The problem arises with chronic activation of the HPA axis, which results in permanently elevated cortisol levels that cannot return to homeostatic levels. This inability to return to homeostasis leads to a chronic increase in cortisol levels, which ultimately desensitizes the glucocorticoid receptors (GR). Integrated negative feedback of the HPA axis through GR at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland is responsible for the suppression of cortisol secretion. This feedback increasingly fails due to a decrease in both the number of expressed GRs and GR desensitization. This ultimately leads to a paradoxical increase in basal cortisol levels but decreased glucocorticoid signaling, which is associated with fatigue, depressed mood, and cognitive impairment. Salivary cortisol appears to be the most accurate measure of cortisol as it reflects non-protein cortisol in the blood. Compared to urinary and plasma cortisol, salivary cortisol is cheaper, less invasive, and requires fewer laboratory resources. All three collection methods have one thing in common - diurnal fluctuations; therefore, it is important to remember that one collection of samples only measures this point in time. Cortisol peaks early in the morning and declines throughout the day. This spike in cortisol is called the cortisol awakening response (CAR), which occurs in all humans and is believed to be used to fuel the human body by temporarily activating gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. As mentioned above, cortisol levels can be measured reliably, but how do you measure the function of the HPA axis?

This ultimately leads to a paradoxical increase in basal cortisol levels but decreased glucocorticoid signaling, which is associated with fatigue, depressed mood, and cognitive impairment. Salivary cortisol appears to be the most accurate measure of cortisol as it reflects non-protein cortisol in the blood. Compared to urinary and plasma cortisol, salivary cortisol is cheaper, less invasive, and requires fewer laboratory resources. All three collection methods have one thing in common - diurnal fluctuations; therefore, it is important to remember that one collection of samples only measures this point in time. Cortisol peaks early in the morning and declines throughout the day. This spike in cortisol is called the cortisol awakening response (CAR), which occurs in all humans and is believed to be used to fuel the human body by temporarily activating gluconeogenesis and glycogenolysis. As mentioned above, cortisol levels can be measured reliably, but how do you measure the function of the HPA axis?

The function of the HPA axis can be measured using validation tests. One such stimulus test is the dexamethasone suppression test (DEX), which was one of the first tests used to assess stress-related psychiatric disorders. Dexamethasone is a synthetic glucocorticoid that binds to GR in the CNS, specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Ordinarily, administration of synthetic glucocorticoids should activate negative feedback and slowly lower cortisol levels. If there is HPA axis dysfunction, then cortisol levels will not go down and may actually go up. In the case of MDD and a potential characteristic of TRD, we hypothesize that this failure to activate negative feedback is indicative of HPA axis dysfunction, possibly due to receptor insensitivity. Most studies have demonstrated that patients with severe depression often exhibit a lack of suppression and impaired feedback suppression by dexamethasone, indicative of dysfunction of corticosteroid receptors, especially GR. Other control tests include the CRH test; combined DEX-CRH test; and the newest test, the Prednisolone Suppression Test (PST).

One such stimulus test is the dexamethasone suppression test (DEX), which was one of the first tests used to assess stress-related psychiatric disorders. Dexamethasone is a synthetic glucocorticoid that binds to GR in the CNS, specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Ordinarily, administration of synthetic glucocorticoids should activate negative feedback and slowly lower cortisol levels. If there is HPA axis dysfunction, then cortisol levels will not go down and may actually go up. In the case of MDD and a potential characteristic of TRD, we hypothesize that this failure to activate negative feedback is indicative of HPA axis dysfunction, possibly due to receptor insensitivity. Most studies have demonstrated that patients with severe depression often exhibit a lack of suppression and impaired feedback suppression by dexamethasone, indicative of dysfunction of corticosteroid receptors, especially GR. Other control tests include the CRH test; combined DEX-CRH test; and the newest test, the Prednisolone Suppression Test (PST). PST is the gold standard for assessing HPA axis function because it can measure both MR and GR, unlike other screening tests.

PST is the gold standard for assessing HPA axis function because it can measure both MR and GR, unlike other screening tests.

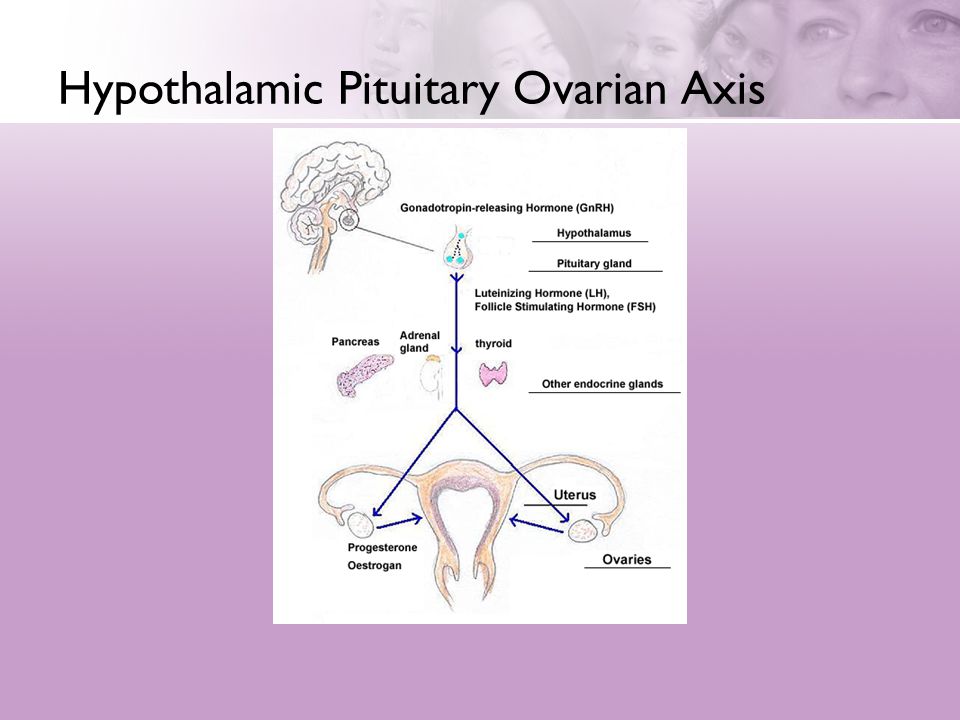

HPA axis hyperactivity inhibits hormone synthesis and secretion in the hypothalamus, pituitary and gonads; gonadotropin-releasing hormone in the hypothalamus; FSH and LH in the pituitary; and testosterone and estradiol in the gonads. After the onset of puberty, the prevalence of anxiety and depression in men and women changes, suggesting a link between mood disorders and sex hormones. Many studies show that a higher prevalence of depression in women is associated with hormonal fluctuations throughout a woman's life cycle, including menstrual changes, pre- and post-natal changes, and menopause. Unlike women, men experience a fairly linear decline in sex hormones, especially testosterone, throughout their lives. Estradiol and testosterone are both central and peripheral gonadal hormones that make up the HPG axis and also influence the HPA axis, cognition, metabolism, and other important autonomic functions. The effects of estrogen and testosterone on the HPA axis are mediated by glucocorticoids. Elevated levels of glucocorticoids are associated with mood disorders, heart disease, and obesity.

The effects of estrogen and testosterone on the HPA axis are mediated by glucocorticoids. Elevated levels of glucocorticoids are associated with mood disorders, heart disease, and obesity.

Given the increased levels of anxiety and depression in older hypogonadal men, it is suggested that androgens and estrogen may have a neuroprotective effect on mood disorders. Androgens act through androgen receptors but can also bind to estrogen receptors. Androgen replacement therapy, in particular testosterone replacement therapy in older men with hypogonadism, not only improves mood, but also reduces symptoms of depression. As mentioned earlier, the literature suggests that the HPA axis and the HPG axis are closely related, and in fact testosterone and cortisol have been shown to inhibit each other's release. If the HPG axis negatively regulates the HPA axis, then the HPG axis may play an important role in reducing TRD, as chronic high levels of glucocorticoids are a key factor in the development of these disorders.

DHEA is a precursor to progesterone, which is a precursor to the gonadal hormones testosterone and estradiol. In addition, DHEA also acts independently on the HPA axis, enhancing the relationship between the HPA axis and HPG. Low DHEA levels have always been associated with increased depressive symptoms. Progesterone, a subsequent metabolite of DHEA, and its own metabolites act as neurosteroids and are strongly associated with mood disorders. Progesterone and its metabolites are allosteric modulators of the GABA A receptor. This means that progesterone and its metabolites can suppress excitatory signals that would otherwise cause feelings of anxiety and fear. Another mechanism proposed in the literature to explain the neuroprotective properties of progesterone and its metabolites relates to the glutaminergic system, since these neurosteroids act as NMDA and AMPA receptors. Allopregnanolone is a subsequent metabolite of progesterone, which in turn is a derivative of pregnenolone in the cholesterol synthesis pathway. An alternative metabolic pathway for pregnenolone involves DHEA, a precursor to testosterone and estradiol. For men, testosterone is recommended as replacement therapy for people with primary hypogonadism, as well as those with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Studies have shown that treatment with certain antidepressants (SSRIs) increases progesterone and allopregnanolone levels, which may reduce depressive symptoms.

An alternative metabolic pathway for pregnenolone involves DHEA, a precursor to testosterone and estradiol. For men, testosterone is recommended as replacement therapy for people with primary hypogonadism, as well as those with hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Studies have shown that treatment with certain antidepressants (SSRIs) increases progesterone and allopregnanolone levels, which may reduce depressive symptoms.

Treatment of sustainable depression

An increase in the number of studies of biomarkers and potential treatment methods is promising not only for adequate treatment of MDD, but also to increase sensitivity to treatment with MDD. Some of these potential treatments are already FDA-approved in other areas for other conditions, including anti-inflammatory drugs (celecoxib and other cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors), TNFα antagonists (etanercept and infliximab), minocycline, and aspirin. Interventions have been tried using HPA components as targets, including CRH receptor antagonists, GR antagonists, and inhibitors of cortisol synthesis. In more recent studies, inhibition of the GR chaperone protein FKBP51 with a selective inhibitor has proven effective.

In more recent studies, inhibition of the GR chaperone protein FKBP51 with a selective inhibitor has proven effective.

Other recently studied biomarkers include interleukin 1B (IL-1B), macrophage inhibitory factor (MIF), and oxytocin. IL-1B is involved in the overactivation of HPA and therefore also a potential target for the treatment of TRD. In addition to the already existing literature on cytokine activity in depression, MIF has become a novel biomarker and target in major depression.

MIF is a hormone with many immunological functions, but it is also a hormone secreted by the anterior pituitary and adrenal glands after HPA activation. When MIF is released, it acts to counteract the inhibitory action of glucocorticoids and therefore induces steroid resistance. MIF antagonizes the inhibitory effect of glucocorticoids on target immune-inflammatory cells, and due to this property, it may be responsible for the induction of steroid resistance. Oxytocin is a neuropeptide that downregulates the HPA axis and recent studies have provided evidence that intranasal oxytocin added to escitalopram may be beneficial in TRD.

Testosterone monotherapy has been found to be most effective in patients with dysthymia or mild depression. The same study did not find any significant differences between oral testosterone, testosterone gel, oral dehydroepiandrosterone, or intramuscular testosterone use. The same study showed that in these men, depression was associated with a decrease in total or plasma testosterone concentrations. Treatment with transdermal estrogen has been shown to improve depression scores. In other studies, premenopausal women who took oral contraceptives (OC) found a decrease in the level of mood disorders during the transition to menopause. In another study, longer use of oral contraceptives from menarche to menopause showed a reduced risk of postmenopausal depression. The results of the above studies show that ovarian hormones protect against mood disorders. Estrogen and progestin hormone replacement therapy and allopregnanolone (a progesterone metabolite) are the most studied hormonal interventions for ovarian effects in depression in women. In fact, studies have found moderate evidence for the effectiveness of estrogen replacement therapy or hormone replacement therapy for perimenopausal or early postmenopausal women with major depression and somatic symptoms of menopause. More recently, the hormone drug allopregnanolone has been approved for the treatment of postpartum depression. Brexanolone, administered intravenously, is one of the first FDA-approved non-steroidal hormones for use in mental illness.

In fact, studies have found moderate evidence for the effectiveness of estrogen replacement therapy or hormone replacement therapy for perimenopausal or early postmenopausal women with major depression and somatic symptoms of menopause. More recently, the hormone drug allopregnanolone has been approved for the treatment of postpartum depression. Brexanolone, administered intravenously, is one of the first FDA-approved non-steroidal hormones for use in mental illness.

Vitamin D belongs to the group of secosteroids and is centrally involved in the regulation of calcium and phosphorus metabolism and immunomodulation. Vitamin D deficiency is a common problem among children and adults worldwide, affecting an estimated 1 billion people worldwide. Evaluation of vitamin D deficiency and subsequent treatment is safe and economical. Studies of vitamin D supplementation show no side effects even at high doses up to 10,000 IU per day, and doses of 800 IU are usually sufficient to achieve a 25(OH)D level of at least 50 nmol/L (or 20 ng/mL).

A growing body of literature suggests that one-carbon metabolism may inhibit response to antidepressant treatment. The one carbon cycle includes agents such as folate, L-methylfolate, S-adenosylmethionine (SAMe), vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and homocysteine. Although the literature suggests that a deficiency in each of these components may be independently associated with depression, folic acid levels in particular are the most common. Folate, also known as vitamin B9, exists in 2 forms: dihydrofolate (in foods) or synthetic form (supplements). The first step in this one-carbon metabolism is the conversion of synthetic or dietary folate to 5-methyltetrahydrofolate (L-methylfolate) by methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase (MTHFR). L-methylfolate (also known as levomefolic acid or 5-methyltetrahydrofolate) is the active form of folic acid or folic acid and plays an important role in neurotransmitter synthesis. The methionine synthetase then uses the active form, L-methylfolate, as a methyl donor to convert homocysteine to L-methionine. Vitamin B12 helps carry out this reaction. Methionine then reacts with ATP to form SAMe. SAMe acts as a methyl donor similar to L-methylfolate and plays an important role in monoamine methylation and hence neurotransmitter synthesis via the tetrahydrobiopterin (Bh5) pathway and phenylalanine and tryptophan hydroxylation. Numerous studies have shown a link between depression and folic acid deficiency. L-methylfolate, the active form of vitamin B9, is the only form that can cross the blood-brain barrier. In fact, L-methylfolate is one of the only health food products licensed by the FDA to treat depression. Regarding the study on the use of L-methylfolate as add-on therapy, the first trial conducted was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 24 patients with MDD and erythrocyte folate deficiency were given 15mg/day of L-methylfolate as add-on therapy. in addition to their antidepressant treatment. At 3 and 6 months post-intervention, patients treated with L-methylfolate showed greater improvement compared to placebo.

Vitamin B12 helps carry out this reaction. Methionine then reacts with ATP to form SAMe. SAMe acts as a methyl donor similar to L-methylfolate and plays an important role in monoamine methylation and hence neurotransmitter synthesis via the tetrahydrobiopterin (Bh5) pathway and phenylalanine and tryptophan hydroxylation. Numerous studies have shown a link between depression and folic acid deficiency. L-methylfolate, the active form of vitamin B9, is the only form that can cross the blood-brain barrier. In fact, L-methylfolate is one of the only health food products licensed by the FDA to treat depression. Regarding the study on the use of L-methylfolate as add-on therapy, the first trial conducted was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which 24 patients with MDD and erythrocyte folate deficiency were given 15mg/day of L-methylfolate as add-on therapy. in addition to their antidepressant treatment. At 3 and 6 months post-intervention, patients treated with L-methylfolate showed greater improvement compared to placebo.

Diabetes and depression

Increasing evidence suggests a bi-directional relationship between depression and insulin resistance, especially with regard to type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). By some estimates, T2DM and depression are twice as likely to occur at the same time. Concomitant depression and insulin resistance have been shown to increase the severity of depressive symptoms as well as reduce the effectiveness of antidepressant treatment. Concomitant depression and insulin resistance have been shown to increase the severity of depressive symptoms as well as reduce the effectiveness of antidepressant treatment. Molecular mediators such as glutamate and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) have been identified as potential mediators of the bidirectional association between T2DM and depression.

F armacogenomics

One of the tools that psychiatrists have used over the past decade to personalize treatment decisions is pharmacogenomic (PGx) testing. PGx testing uses genome sequencing to determine the pharmacokinetic, immune, and pharmacodynamic effects of specific gene variants that can influence an individual's response to drugs. Evidence in favor of PGx testing in psychiatry has come from people with depression who have failed to take at least one medication. Two meta-analyses showed that patients whose treatment was determined by PGx testing resulted in improved symptom remission compared with conventional treatment. Many are still skeptical about such tests or are perplexed. One of the main reasons for this is that previously available tests have not yet been able to determine which drugs are statistically shown to be the most effective. The main barriers include a small number of genes and variants, small sample sizes, and short follow-up times. Although there is still a lot of work to be done, the shortcomings of the tests are being addressed. The combinatorial pharmacogenomic algorithm (PGx) progressively integrates and evaluates multiple pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) genes.

PGx testing uses genome sequencing to determine the pharmacokinetic, immune, and pharmacodynamic effects of specific gene variants that can influence an individual's response to drugs. Evidence in favor of PGx testing in psychiatry has come from people with depression who have failed to take at least one medication. Two meta-analyses showed that patients whose treatment was determined by PGx testing resulted in improved symptom remission compared with conventional treatment. Many are still skeptical about such tests or are perplexed. One of the main reasons for this is that previously available tests have not yet been able to determine which drugs are statistically shown to be the most effective. The main barriers include a small number of genes and variants, small sample sizes, and short follow-up times. Although there is still a lot of work to be done, the shortcomings of the tests are being addressed. The combinatorial pharmacogenomic algorithm (PGx) progressively integrates and evaluates multiple pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) genes. This approach is based on the fact that most drugs are not eliminated by one detoxification pathway, different pathways are more important than others, and mutations in even minor pathways can have a negative impact.

This approach is based on the fact that most drugs are not eliminated by one detoxification pathway, different pathways are more important than others, and mutations in even minor pathways can have a negative impact.

Blog Post Category:

Biological Psychiatry

You must enable JavaScript to use this form.

Your name *

Your phone number (privacy guaranteed) *

Main complaint *

Presumptive diagnosis

Taking medication

Consent to the processing of personal data *

I agree to the processing of personal data, I have read the privacy policy

Hack stress: cortisol-lowering supplements and foods | by Biohacking

continuation of the article: “Why do we experience chronic stress?”

Chronic stress can cause a vicious cycle of inflammation, neurotransmitter imbalances, and nutritional deficiencies, but with certain supplements and foods, you can reverse (or at least significantly mitigate) these negative effects.

Because chronic inflammation due to malnutrition and stress sustains high levels of cortisol (which is designed to fight inflammation), glucocorticoid receptor (GCR) resistance develops, resulting in the body's inability to suppress inflammatory responses.

Stress, chronic inflammation and high cortisol levels are responsible for most of today's diseases. Therefore, whole foods, anti-inflammatory foods, and a nutrient-dense diet are best for managing stress. If you suspect that you have an intolerance to certain foods and therefore avoid them, you need to find out if this is really the case. Because it can play a big role in reducing inflammation. You can do this, for example, using the Paleo Autoimmune Protocol.

HPA axis dysfunction is also associated with neurotransmitter imbalance, so eating foods that support this balance will help suppress cortisol release. Neurotransmitters are mainly composed of amino acids, B vitamins and minerals. Deficiency in any of these three essential components can lead to inadequate neurotransmitter building blocks. The main vitamins associated with cortisol are the B vitamins, thanks in large part to their association with gamma-aminobutyric acid (capable of controlling cortisol levels), vitamin C, and vitamin D.

The main vitamins associated with cortisol are the B vitamins, thanks in large part to their association with gamma-aminobutyric acid (capable of controlling cortisol levels), vitamin C, and vitamin D.

Before moving on to the list of cortisol-lowering foods, it's important to mention the foods to avoid. These include sugar, processed foods, refined carbohydrates, inflammatory fats (such as trans fats), as well as vegetable and seed oils high in omega-6s, alcohol, and caffeine. All of these foods can increase cortisol levels. It is best to eat a diet that includes whole foods, lots of vegetables, fruits, some free range meat if you eat meat, and wild fish.

Speaking of caffeine, this does not mean that you need to stop drinking coffee altogether. In moderation, you can consume decaffeinated coffee, as long as you choose a good quality product that is organic and free of harsh chemicals.

Foods that lower cortisol levels

1. Foods rich in omega-3s

Research has shown that lower levels of omega-3s are associated with cortisol dysregulation and inflammation. Foods High in Omega 3:

Foods High in Omega 3:

Some cortisol-lowering foods rich in B vitamins:

- Leafy greens such as spinach, kale, turnip greens, and romaine lettuce (high in B9)

- Oysters, clams and mussels are high in B12, as well as B1, B2, B3 and B9

- Legumes such as edamame, lentils, chickpeas and black beans, are high in folate (B9

- Homemade yogurt high in B2 and B12

- Nutritional and brewer's yeast high in B1, B2, B3, B6, B9 and B12

, therefore, is necessary for the correct functioning of the HPA axis. Vitamin C deficiency is associated with high cortisol levels, and sufficient vitamin C reduces cortisol levels. You will find a large content of this vitamin in foods such as:

Note: If you have bacterial overgrowth syndrome (SIBO), be careful with prebiotics and probiotics.

6. Foods rich in magnesium

Magnesium deficiency causes anxiety and dysregulation of the HPA axis. Foods high in magnesium:

- Dried apricots

- Dark chocolate

- Avocados

- Nuts and seeds

- Legumes

- Leafy greens

7. 0003

0003

Rat studies show that the oleuropein in olive oil increases testosterone and metabolism, and lowers cortisol levels. Choose a quality and natural olive oil.

This is a fairly exhaustive list. Incorporate as many of these foods into your diet as possible and avoid the ones discussed earlier (sugar, processed foods, refined carbohydrates, inflammatory fats, alcohol and caffeine) and you will be able to slow down your body's endless cycle of cortisol production.

Supplements that lower cortisol levels

Some supplements have also been shown to lower cortisol levels. Always start by changing your diet, but when you don't have access to some of the foods on the list above, then supplements make sense.

N.B. Do not prescribe supplements yourself, consult a biohacker doctor or naturopath. You can restore yourself with supplements, but the wrong supplement or its dosage can be harmful!

1. Adaptogenic Herbs

Adaptogenic herbs are unique healing herbs that help to respond to any stressor by normalizing physiological function. Cortisol lowering herbs:

Cortisol lowering herbs:

- Ashwagandha - 125-600 mg. per day

- Schisandra — from 500 mg. up to 2 g extract or 1.5-6 g raw lemongrass per day

- Rhodiola - 288-680 mg. extract per day

- Holy basil - 300-2000 mg. extract per day

- Lemon balm - 300-600 mg. per day

- Cordyceps - 1 g per day

- Licorice root - 1-4 g of crushed root daily 3 times a day (may not reduce cortisol levels, but optimize the function of the HPA axis)

2. Phosphatidylserine

This is a fat found in high concentrations in the brain and nervous system. Phosphatidylserine helps manage both physical and mental stress by lowering cortisol levels. In addition to lowering cortisol levels, it has also been shown to have a positive effect on cognitive decline and dementia. Take 100 mg. 3 times a day.

3. Ginkgo Biloba

This popular supplement has many positive effects besides lowering cortisol levels, such as reducing inflammation, improving heart health, and supporting the brain. Take 120-240 mg. ginkgo biloba a day.

Take 120-240 mg. ginkgo biloba a day.

4. L-theanine

Found in green and black and white teas, lowers cortisol levels and improves cognitive function. Take 100-200 mg. in a day. Can be taken in the morning with caffeine to boost concentration and mood, or before bed to improve relaxation and sleep.

5. Zinc

Zinc has been shown to lower cortisol levels. Take 14-25 mg. in a day.

6. Fish oil

A number of studies show its ability to reduce cortisol levels. Take 1000-7500 mg. high quality fish oil per day.

7. Essential Amino Acids (EAA)

When cortisol levels are high, protein is broken down into amino acids, which are then converted into glucose. So if you don't get enough EAAs, you run the risk of losing muscle during times of stress. And since EAAs are necessary for the production of neurotransmitters that affect cortisol levels, a balanced intake will be beneficial. Take 5-10 g per day.

8. Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA)

100 mg. GABA reduce stress during mental stress. Low GABA levels in PTSD patients are associated with poor sleep quality. GABA is found in dairy products, brown rice sprouts, barley, and legumes, or can be taken as a supplement.

GABA reduce stress during mental stress. Low GABA levels in PTSD patients are associated with poor sleep quality. GABA is found in dairy products, brown rice sprouts, barley, and legumes, or can be taken as a supplement.

9. Oolong tea

There is a study showing that 4 servings of 2 g of tea per day can lead to a significant decrease in cortisol levels.

10. L-ornithine

Use 400 mg. L-ornithine per day can lead to a significant decrease in the level of cortisol in the blood, as well as to balance the ratio of cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEA-S). Helps reduce anger and improve sleep quality.

11. Curcumin

Curcumin reduces inflammation, which in turn reduces cortisol production. Take 500-2000 mg. in a day.

12. Kion Lean Supplement

The ingredients in Kion Lean blunt the glycemic response, resulting in a decrease in cortisol production. Take 2 capsules daily (before or after your most carbohydrate-rich meal).