How to shut someone up in an argument

5 Ways To Stop An Argument In Less Than A Minute

Pat LaDouceur, PhD, helps people dealing with anxiety, panic, and relationship stress who want to feel more focused and confident. She has a private practice ...Read More

The trouble with arguments is that they don’t work.

I’m not talking about a good debate, where you have some great ideas, and they clash, and you start a healthy back-and-forth that feels fun. I mean arguments – where tension starts to rise, responses start to get personal, and you go around in circles without getting anywhere.

Often this kind of conflict takes on a life of it’s own, where you end up arguing about who does more of the chores or what time you came home last night, while bigger issues like caring, teamwork, and appreciation hide under the surface.

This is what many of the couples I work with mean when they say, “we can’t communicate. ” They start what seems like a simple conversation, and within minutes it escalates into criticism, blame, hostility, or stonewalling.

Therapists are Standing By to Treat Your Depression, Anxiety or Other Mental Health Needs

Explore Your Options Today

It’s not just couples either – unwanted arguments happen in families, between friends, and at work. With some skill, though, you can learn to stop them, so you can get on with solving the real concerns.

What doesn’t work

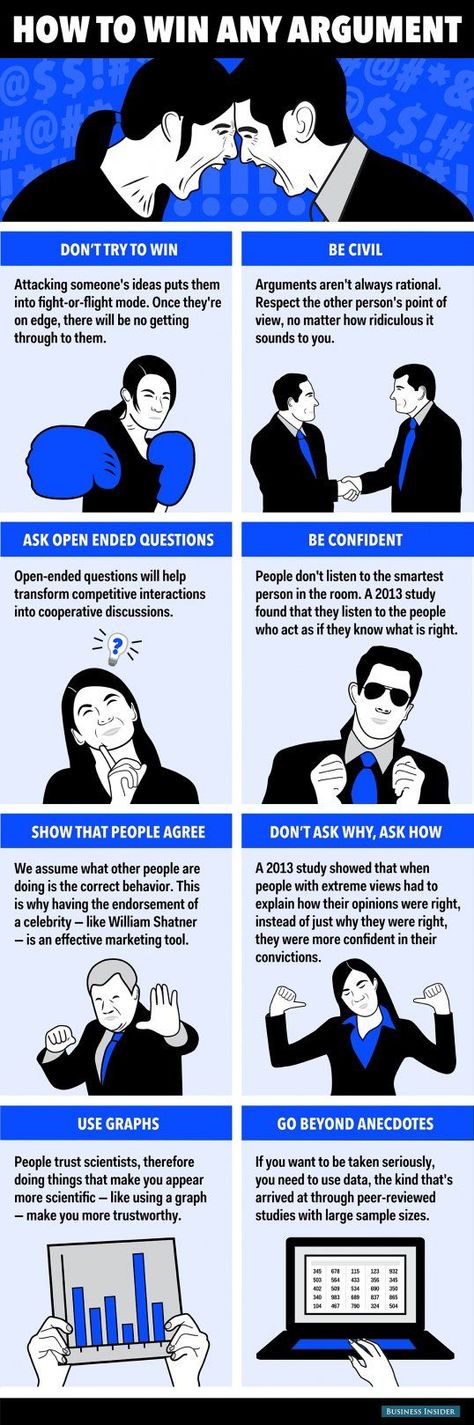

Have you ever felt like you know you’re right, but the other person doesn’t understand? Or maybe every once in awhile you just have to have something go your way? For some people, the feeling of urgency nudges them into using some of these tactics:

- speaking more loudly

- bringing up evidence

- speaking with a tone of urgency

- refusing to let the topic drop

- following the other person from room to room

These strategies create problems, though. A raised voice can sound like an attack. Evidence provides an opportunity to get sidetracked by debating the evidence. Urgency often comes across as impatience or frustration.

A raised voice can sound like an attack. Evidence provides an opportunity to get sidetracked by debating the evidence. Urgency often comes across as impatience or frustration.

If the conversation stays on track, you can keep trying to solve the problem. If it turns into an argument, you might need something another strategy.

How to Stop Arguments in a Relationship

No one likes arguing, especially in relationships. It can be hard to know how to stop arguing and fighting once it has started. Even though it may feel like it’s impossible to end the conflict, there are things you can do to de-escalate a situation and prevent future arguments from happening.

Relationship arguments can range from minor disagreements about household chores or choosing a restaurant for dinner, to major fights about trust issues or money. It is important to recognize what kind of disagreement you are having because that will help determine the best way to stop arguing. If the argument becomes more of a power struggle, then it may require professional help from a licensed therapist.

One way to stop arguments in a relationship is to take a break when things start to feel heated. This gives each person time to cool off and reflect on the situation before continuing the conversation. It’s also helpful to choose your words carefully and avoid name-calling or personal attacks. Remember that no one is perfect and it’s important to be respectful of each other’s feelings.

If arguments have become a regular occurrence in your relationship, then it may be time to take a step back and evaluate the underlying cause. Are you both feeling unheard or misunderstood? Is there an unresolved issue that needs to be addressed? Couples counseling can help couples identify patterns of behavior that may be leading to arguments. Additionally, taking time for self-care and engaging in activities that bring joy can also help couples reconnect and reduce the chances of future conflicts.

A game changing strategy

One of the kids in our neighborhood has a great way of handling the frustration of not getting his way. Like many six-year-olds, he loves winning. Young kids about this age are often obsessed with winning, losing, and rules. If there is a contest, Frankie naturally wants to come out on top.

Like many six-year-olds, he loves winning. Young kids about this age are often obsessed with winning, losing, and rules. If there is a contest, Frankie naturally wants to come out on top.

Of course, the ball doesn’t always bounce that way. When Frankie plays Four-Square with his family, sometimes he misses a few returns. He doesn’t want to compromise his winning or his generally buoyant mood, so he just announces some new rules, and with such humor that everyone laughs. This game – the one where Frankie always wins – is known as “Frankieball.”

Adults, or course, have to use more finesse. The “I Win No Matter What” game is not so endearing when you’re twenty, or perhaps fifty.

Still, there’s a middle ground. When the game isn’t working – when discussions veer into argument territory – it’s helpful to pause and consider some new rules. Sometimes it’s better not to play at all.

New plays

There are many ways to graciously step back from an argument. Here are four simple statements you can use that will stop an argument 99 percent of the time.

Here are four simple statements you can use that will stop an argument 99 percent of the time.

1. “Let me think about that.”

This works in part because it buys time. When you’re arguing, your body prepares for a fight: your heart rate goes up, your blood pressure increases, you might start to sweat. In short, you drop into fight-or-flight mode. Marriage researcher John Gottman calls this “flooding”. Your mental focus narrows, so that you think about the danger in front of you rather than nuances and possibilities. Because of this, the ability to problem-solve plummets.

When there is no lion about to pounce, flooding gets in your way. Taking time to think allows your body to calm down. It also sends a message that you care enough to at least consider someone else’s point of view, which is calming for the other person in the argument.

2. “You may be right.”

This works because it shows willingness to compromise. This signal is enough to soften most people’s position, and allow them to take a step back as well.

Yet it’s hard to do. Sometimes my clients worry that giving an inch is very close to giving in. In my view, it’s usually the opposite: acknowledging someone else’s point of view usually leads to a softening. Look at some examples:

- Comment: Blue jeans aren’t appropriate to wear to work.

- Response: You may be right.

- Comment: This project is going to be late.

- Response: I’m working on it, but you may be right.

- Comment: You didn’t handle that very well.

- Response: You may be right.

Notice that with this Aikido-like sidestep, you are not agreeing that the other person is right. You’re only acknowledging that there might be something to their point of view, and implying that you’ll consider what they said.

3. “I understand.”

These are powerful words. They work because they offer empathy. They stop an argument by changing it’s direction – trying to understand someone else’s point of view isn’t an argument. They are sometimes hard to say, because pausing to understand can sometimes feel like giving in. It’s important to remember that:

They are sometimes hard to say, because pausing to understand can sometimes feel like giving in. It’s important to remember that:

- Understanding doesn’t mean you agree.

- Understanding doesn’t mean you have to solve the problem.

With the pressure to assert yourself or fix it out of the way, you can just listen.

4. “I’m sorry.”

These words are perhaps the most powerful in the English language. One administrator I know says that half his job is apologizing to people.

Many people are reluctant to apologize, fearing that an apology is an admission of guilt and an acceptance of complete responsibility. This view unfortunately often makes the problem worse.

Apologies sometimes just express sympathy and caring: “I’m sorry you didn’t get that job.”

More often, though, apologies mean owning some part of the responsibility: “I’m sorry my comment came across that way. It’s not what I meant.”

Occasionally an apology is an admission of complete responsibility, and in those cases a heartfelt expression of regret becomes all the more important: “You’re right, I didn’t get it done on time. I’ll do everything I can to make sure it doesn’t happen again.” Apologies change the game from “It’s Not My Fault” to “I Understand.” Apologies are powerful; they have prevented lawsuits, improved business communication, and healed personal rifts.

I’ll do everything I can to make sure it doesn’t happen again.” Apologies change the game from “It’s Not My Fault” to “I Understand.” Apologies are powerful; they have prevented lawsuits, improved business communication, and healed personal rifts.

Home run

Of course, sidestepping an argument is only the first step in sorting through an emotionally charged issue. Sometimes you have to dig beneath the surface so that you can talk about the beliefs and feelings underneath. Then there’s work to be done in negotiating a compromise or coming to an agreement. However, arguments keep you spinning in circles, and usually make the problem worse.

Sometimes the only way not to lose is to stop playing the game. Like Frankie, you can change the rules. Instead of, “One of Us Has to Win,” you can play, “Let’s Take Some Time with This.” With a simple statement, you can buy time, show willingness to compromise, offer empathy, or own part of the problem. These strategies are the basis of good communication. When the object of the game is to stop arguing, both players can win.

When the object of the game is to stop arguing, both players can win.

Keep Reading By Author Pat LaDouceur, Ph.D.

Read In Order Of Posting

This 1 key sentence will help defuse arguments in your relationships

Akai Suddeth | Twenty20

If there's one thing we know about fights and conflicts, whether inside or outside the office, it's that angry people often look for reasons to stay angry.

Hardly anyone will ever come up to you and furiously say, "You know, rather than being angry, I'm just going to stare at you and remind myself of all the reasons I really do like you." (Wouldn't that be great, though?)

Instead, your angry colleague might dredge up something you said in a meeting last month, just as an angry boss might reference that one time you missed a deadline. An angry spouse might stir the pot by complaining about how you missed the family holiday party last year.

Why exactly does this happen? According to psychologist Harry Mills, anger is defined as "feelings of pain combined with anger-triggering thoughts" that can sometimes motivate a person to defend themselves by striking out against their target. This allows them to feel justified in their anger.

This allows them to feel justified in their anger.

Don't take the bait

A 2013 study, called "Conflict Management: Difficult Conversations with Difficult People," conducted by researchers from the University of Wisconsin, found that it's important to maintain a safe environment when in the middle of an argument. That means saying sentences or asking open-ended questions that lead to points of agreement. The data suggested using "I" statements, specifically.

To defuse an argument, avoid taking the bait and allowing the other person to justify their anger.

Instead, you can simply say, "I'd actually like to focus on all the things we agree on."

(You can vary the exact wording as long as you include the word "agree" — e.g., "I think we actually agree on a lot," or "let's start by talking about where we agree.")

Why it works

This sentence delivers a number of benefits. First, it ensures that we don't get suckered into prolonging the fight. When we force ourselves to look for areas of agreement, it changes our mindset. We move from seeing a person as an enemy to seeing them as someone who's not that different from us.

When we force ourselves to look for areas of agreement, it changes our mindset. We move from seeing a person as an enemy to seeing them as someone who's not that different from us.

Second, it deprives the angry person of additional fuel for their anger. We've all encountered the person who's in a foul mood and just looking to pick a fight with anyone. But when we greet their provocations with a smile and a desire for seeking agreement, we make ourselves a very unappealing target.

Third, if anyone from the outside happens to be observing, we look like the nice, mature, collaborative, rational party. Anger is not a flattering look, especially in the workplace, and it will inevitably damage a reputation. But if you're seen as the person who can find agreement, who calmly and smoothly assuages anger, you'll earn the trust of your colleagues and bosses. This can lead to the type of high-profile assignments that angry people don't get.

There is always a common ground

If you feel you're in a situation where absolutely no agreement or common ground can be found, try looking again. Most of the time, even the most divisive situations have potential agreement.

Most of the time, even the most divisive situations have potential agreement.

Anger is not a flattering look, especially in the workplace, and it will inevitably damage a reputation.

How to silence a person who deliberately pisses you off

To defend your point of view in public or present a project, you need to have a certain courage and self-confidence. As long as the audience politely listens to you and does not interrupt, it seems to be easy. But what to do if there are people in the team or at the presentation who all the time want to tease you and criticize you with absolutely no constructiveness?

Rehashing an article by facilitator and coach Tina Frey Clements for Entrepreneur on what can be done to deal with bullying in public speaking or teamwork.

Criticism and derogatory statements that the offender allows himself have nothing to do with who and what says during the speech.

Constantly hearing caustic, non-constructive remarks is unpleasant, but you don’t need to be led by them: you won’t solve the problem by answering with the same coin. Calm down and try to realize that the person who gets in your way is most likely in pain or fear himself, and in such a primitive way is trying to improve his well-being or feel safe. Ask yourself the question: “I wonder what is really going on with this person?” So you can abstract from the desire to take all the criticism personally and look at the situation from the outside.

Giving everyone in the team the opportunity to speak will help relieve tension and quench potential conflict.

Criticism of your ideas coming from one person can inflame the situation in the whole team. To prevent resistance and dissatisfaction from growing, it is important to give participants the opportunity to speak. Do not be afraid of criticism, calmly accept the fact that people have the right to a different opinion. Be an active listener: respond non-verbally to statements, paraphrase and repeat them so that participants understand that you are hearing them. When it's time to return to your presentation, thank all the speakers, once again show that you understood them, and ask permission to return to the task.

Be an active listener: respond non-verbally to statements, paraphrase and repeat them so that participants understand that you are hearing them. When it's time to return to your presentation, thank all the speakers, once again show that you understood them, and ask permission to return to the task.

Coping with passive aggression is a one-on-one conversation where you ask direct questions about what is going on.

If the criticizing person does not calm down and persists, take a break and take him aside to talk in private. People are rarely ready to gloat and resent in response to a benevolent, but confident and persistent desire to understand. Perhaps the opinion of the interlocutor will even be useful to you. A private conversation is crucial, it shows that you respect the person, are ready to listen to him and understand his problem and expect respect from him in return. If he cannot control himself and clearly continues to behave aggressively, you can ask him to leave the event.

If there is no way to talk to the person in private, being able to express your doubts during the speech will also reduce the level of passive aggression.

If you cannot stop your performance, but the person who criticizes you continues to interrupt and interfere with speaking, you cannot allow him to sabotage the event - you need to react immediately. To begin with, you can say something like "you have every right to think so" and thus show respect, but disagree with the speaker. Then ask him or her open questions, listen carefully and try to understand the root cause of his behavior, ask where he or she has such an opinion about the problem. In response, do not start a heated discussion, but try to reduce everything said to a proposal to discuss it during a break or after the event.

To calm the offender, you can simply come closer to him.

If a critic makes snide remarks to others or engages in side conversation during a group activity, stand next to that person. The situation will be resolved simply by your presence nearby - it is more difficult to criticize something and behave defiantly disrespectfully when the speaker is standing nearby.

The situation will be resolved simply by your presence nearby - it is more difficult to criticize something and behave defiantly disrespectfully when the speaker is standing nearby.

The main thing to remember is that you cannot ignore a person who behaves aggressively towards you: by indifference, you seem to be telling everyone present that they and you yourself are less important than the “valuable” comments of the offender. In such situations, it is always necessary to respond quickly, respectfully and with precision.

The best way to win an argument?

- Tom Stafford

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Image copyright Thinkstock

You are sure that you are right and that the other person is, of course, wrong. How to convince him? Psychologists say that the tactics we usually resort to are wrong.

I'm embarrassed to point this out, but you're wrong... Your position is contrary to logic... Just listen, I'll give a lot of arguments in defense of my position right now, and you will understand that you're wrong!.. You know? Sounds familiar?

The argument may be about global warming, the state of affairs in the Middle East or vacation plans, and usually we try to convince the opponent, make him change his mind. Most often, this ends with the fact that he only strengthens in his opinion. Fortunately, research shows that there is another way: to listen more and to put less pressure on the interlocutor.

A little over a decade ago, Leonid Rosenblit and Frank Keil of Yale University suggested that in many cases, when people think they understand a subject, in practice their knowledge is superficial at best. They called this phenomenon the illusion of depth of understanding.

They first asked the participants how well they understood how different devices work, such as a toilet flush, a car's speedometer, or a sewing machine. Then they were asked to explain the mechanism of work. Then they were again asked to assess the degree of their understanding. It turned out that after trying to explain, people, on average, rated their understanding of the subject much lower than before.

Then they were asked to explain the mechanism of work. Then they were again asked to assess the degree of their understanding. It turned out that after trying to explain, people, on average, rated their understanding of the subject much lower than before.

Because we are familiar with the device, we think we understand exactly how it works, scientists conclude. After all, usually no one arranges checks for us. Well, if something is not clear - then you can just look again. Humans tend to be simplistic when making judgments and making decisions—psychologists call this the behavior of the cognitive miser.

Why waste energy on a deep understanding of a subject when we can do without it? The most interesting thing is that we manage to successfully hide this superficial understanding even from ourselves.

This phenomenon is familiar to anyone who has ever tried teaching. Sometimes it is enough to start rehearsing an explanation to meet your own misunderstanding of the subject, and sometimes, worse, it happens when the student asks the first clarifying question. Teachers often confess, "I didn't really understand it until I had to teach it." Or, as the researcher and inventor Mark Changizi said: "No matter how much I teach, I always learn something."

Teachers often confess, "I didn't really understand it until I had to teach it." Or, as the researcher and inventor Mark Changizi said: "No matter how much I teach, I always learn something."

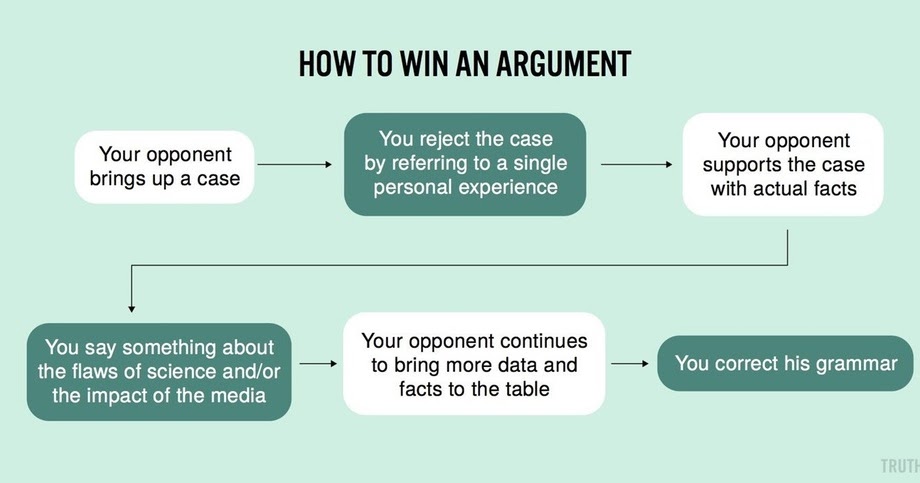

A study on this effect was published last year. It shows how to use the illusion of understanding to convince the interlocutor that he is wrong. A group of scientists from the University of Colorado, led by Philip Fernbach, demonstrated that this phenomenon is applicable to understanding both political opinions and the operation of a cistern.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image captionAsk your opponent to explain exactly how their ideas work

They suggested that a person with strong political convictions will begin to more easily perceive someone else's point of view if he is asked to explain exactly how the policy he advocates will lead to the results that he declares.

Recruiting volunteers from the United States via the Internet, they interviewed them on some issues of American politics. These were sanctions against Iran, health issues and attitudes towards carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere.

These were sanctions against Iran, health issues and attitudes towards carbon dioxide emissions into the atmosphere.

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

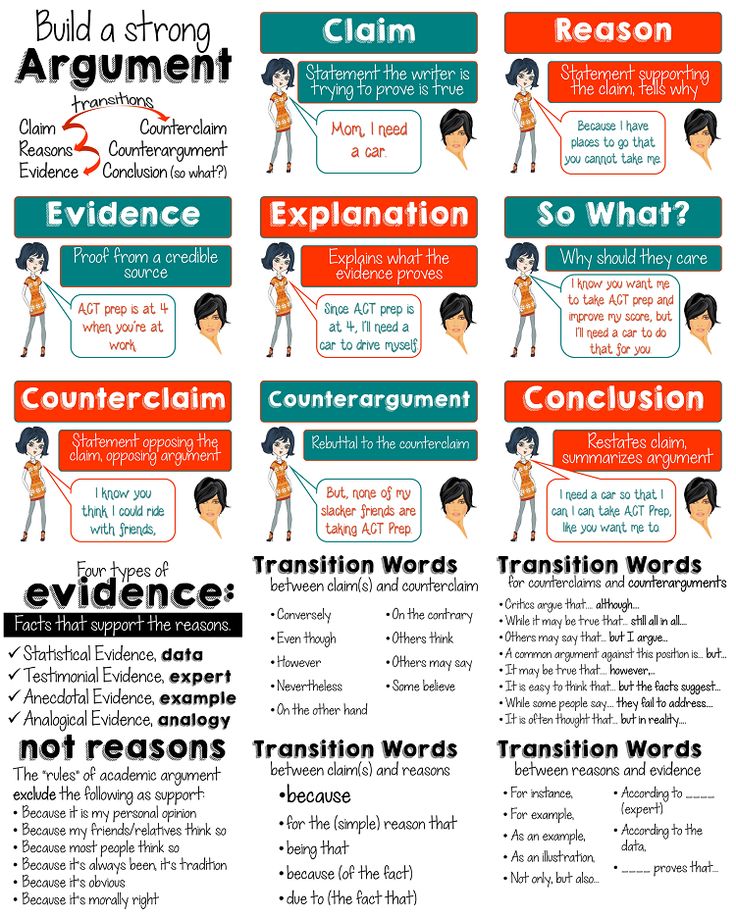

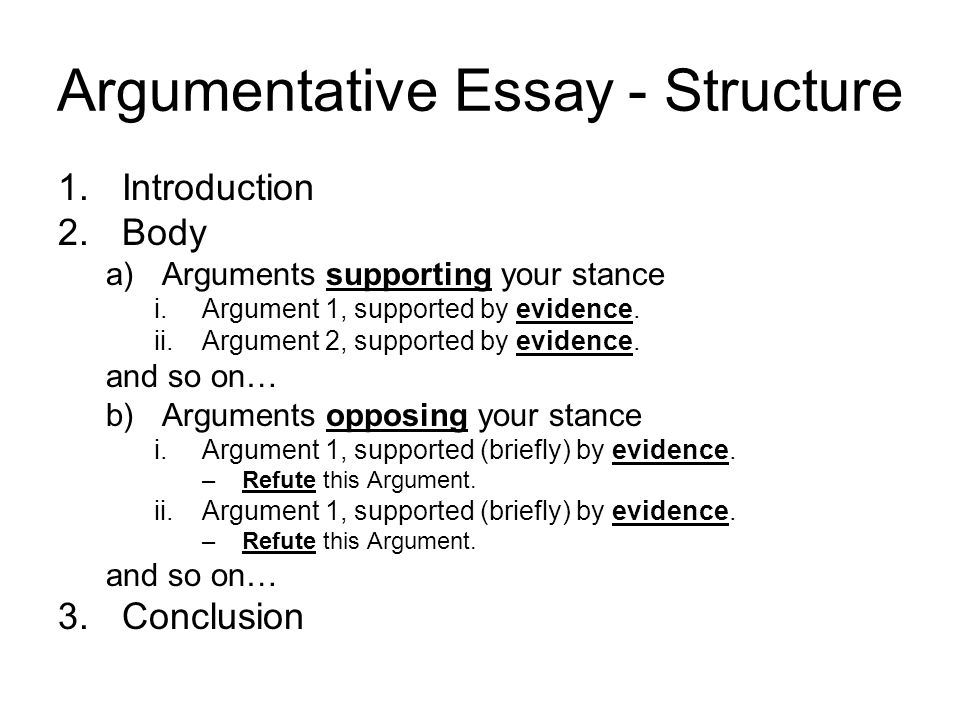

One group was asked to give their opinion and then state why they hold that view. This group was given the opportunity to express their views on the problem, as is the case in an argument or debate.

The scenario for the second group was slightly different. They were asked not to give reasons, but to explain how the policy they advocated would work. They were asked to trace, step by step, the cause-and-effect relationships leading from a political decision to an intended effect.

The results were clear. People who argued, defending their point of view, remained unconvinced. Those who were asked to provide explanations softened their position and also downgraded their understanding of the problem. Study participants who had previously been strongly opposed to, or enthusiastically supported, emissions trading have softened their views. In their own words, they have become less confident about the benefits or harms of quotas.

So the next time you convince a friend or colleague that more nuclear plants should be built, or that capitalist society is about to collapse, or that dinosaurs have lived side by side with humans for 10,000 years, think about it.

Perhaps once you try to explain in detail (first to yourself) why you are right, you will want to study the issue in more depth. And in the course of studying, you may have to adjust your opinion.

About the author. Tom Stafford lectures at the Department of Psychology at the University of Sheffield (England).