How to deal with anxiety in toddlers

How to Cope With an Anxious Child

When children are chronically anxious, even the most well-meaning parents, not wanting a child to suffer, can actually make the youngster’s anxiety worse. It happens when parents try to protect kids from their fears. Here are pointers for helping children escape the cycle of anxiety.

1. The goal isn’t to eliminate anxiety, but to help a child manage it.

None of us wants to see a child unhappy, but the best way to help kids overcome anxiety isn’t to try to remove stressors that trigger it. It’s to help them learn to tolerate their anxiety and function as well as they can, even when they’re anxious. And as a byproduct of that, the anxiety will decrease over time.

2. Don’t avoid things just because they make a child anxious.

Helping children avoid the things they are afraid of will make them feel better in the short term, but it reinforces the anxiety over the long run. Let’s say a child in an uncomfortable situation gets upset and starts to cry — not to be manipulative, but just because that’s how they feel. If their parents whisk them out of there, or remove the thing they’re afraid of, the child has learned that coping mechanism. And that cycle has the potential to repeat itself.

3. Express positive — but realistic — expectations.

You can’t promise a child that their fears are unrealistic—that they won’t fail a test, that they’ll have fun ice skating, or that another child won’t laugh at them during show & tell. But you can express confidence that they’re going to be okay, that they will be able to manage it. And you can let them know that as they face those fears, the anxiety level will drop over time. This gives them confidence that your expectations are realistic, and that you’re not going to ask them to do something they can’t handle.

4. Respect their feelings, but don’t empower them.

It’s important to understand that validation doesn’t always mean agreement. So if a child is terrified about going to the doctor because they’re due for a shot, you don’t want to belittle those fears, but you also don’t want to amplify them. You want to listen and be empathetic, help them understand what they’re anxious about, and encourage them to feel that they can face their fears. The message you want to send is, “I know you’re scared, and that’s okay, and I’m here, and I’m going to help you get through this.”

You want to listen and be empathetic, help them understand what they’re anxious about, and encourage them to feel that they can face their fears. The message you want to send is, “I know you’re scared, and that’s okay, and I’m here, and I’m going to help you get through this.”

5. Don’t ask leading questions.

Encourage your child to talk about their feelings, but try not to ask leading questions— “Are you anxious about the big test? Are you worried about the science fair?” To avoid feeding the cycle of anxiety, just ask open-ended questions: “How are you feeling about the science fair?”

What you don’t want to do is be saying, with your tone of voice or body language: “Maybe this is something that you should be afraid of.” Let’s say a child has had a negative experience with a dog. Next time they’re around a dog, you might be anxious about how they will respond, and you might unintentionally send a message that they

should, indeed, be worried.

7. Encourage the child to tolerate their anxiety.

Let your child know that you appreciate the work it takes to tolerate anxiety in order to do what they want or need to do. It’s really encouraging them to engage in life and to let the anxiety take its natural curve. We call it the “habituation curve.” That means that it will drop over time as he continues to have contact with the stressor. It might not drop to zero, it might not drop as quickly as you would like, but that’s how we get over our fears.

8. Try to keep the anticipatory period short.

When we’re afraid of something, the hardest time is really before we do it. So another rule of thumb for parents is to really try to eliminate or reduce the anticipatory period. If a child is nervous about going to a doctor’s appointment, you don’t want to launch into a discussion about it two hours before you go; that’s likely to get your child more keyed up. So just try to shorten that period to a minimum.

9. Think things through with the child.

Sometimes it helps to talk through what would happen if a child’s fear came true—how would they handle it? A child who’s anxious about separating from their parents might worry about what would happen if a parent didn’t come to pick them up. So we talk about that. If your mom doesn’t come at the end of soccer practice, what would you do? “Well I would tell the coach my mom’s not here.” And what do you think the coach would do? “Well he would call my mom. Or he would wait with me.” A child who’s afraid that a stranger might be sent to pick them up can have a code word from their parents that anyone they sent would know. For some kids, having a plan can reduce the uncertainty in a healthy, effective way.

10. Try to model healthy ways of handling anxiety.

There are multiple ways you can help kids handle anxiety by letting them see how you cope with anxiety yourself. Kids are perceptive, and they’re going to take it in if you keep complaining on the phone to a friend that you can’t handle the stress or the anxiety. I’m not saying to pretend that you don’t have stress and anxiety, but let kids hear or see you managing it calmly, tolerating it, feeling good about getting through it.

I’m not saying to pretend that you don’t have stress and anxiety, but let kids hear or see you managing it calmly, tolerating it, feeling good about getting through it.

Video Resources for Kids

Teach your kids mental health skills with video resources from The California Healthy Minds, Thriving Kids Project.

Start Watching

How To Help A Child With Anxiety : Life Kit : NPR

Lindsey Balbierz for NPR

Lindsey Balbierz for NPR

Explore Life Kit

This story is adapted from an episode of Life Kit, NPR's podcast with tools to help you get it together. To listen to this episode, play the audio at the top of the page or subscribe here. For more, sign up for the newsletter and follow @NPRLifeKit on Twitter.

Childhood anxiety is one of the most important mental health challenges of our time. One in five children will experience some kind of clinical-level anxiety by the time they reach adolescence, according to Danny Pine, a child and adolescent psychiatrist at the National Institute of Mental Health and one of the world's top anxiety researchers. Pine says that for most kids, these feelings of worry won't last, but for some, they will — especially if those children don't get help.

Pine says that for most kids, these feelings of worry won't last, but for some, they will — especially if those children don't get help.

Here are six takeaways that all parents, caregivers and teachers can add to their anxiety toolkits, including information on how anxiety works, how parents can spot it and how to know when it's time to get professional help.

1. Anxiety is a fear of the future and all its unpredictability.

"The main thing to know about anxiety is that it involves some level of perception about danger," says Pine, and it thrives on unpredictability. The mind of an anxious child is often on the lookout for some future threat, locked in a state of exhausting vigilance.

We all have some of this hard-wired worry, because we need it. Pine says it's one of the reasons we humans have managed to survive as long as we have. "Young children are naturally afraid of strangers. That's an adaptive thing. They're afraid of separation."

Full-blown anxiety happens when these common fears get amplified — as if someone turned up the volume — and they last longer than they're supposed to. Pine says separation anxiety is quite common at age 3, 4 or 5, but it can be a sign of anxiety if it strikes at age 8 or 9. According to research, 11 is the median age for the onset of all anxiety disorders.

Pine says separation anxiety is quite common at age 3, 4 or 5, but it can be a sign of anxiety if it strikes at age 8 or 9. According to research, 11 is the median age for the onset of all anxiety disorders.

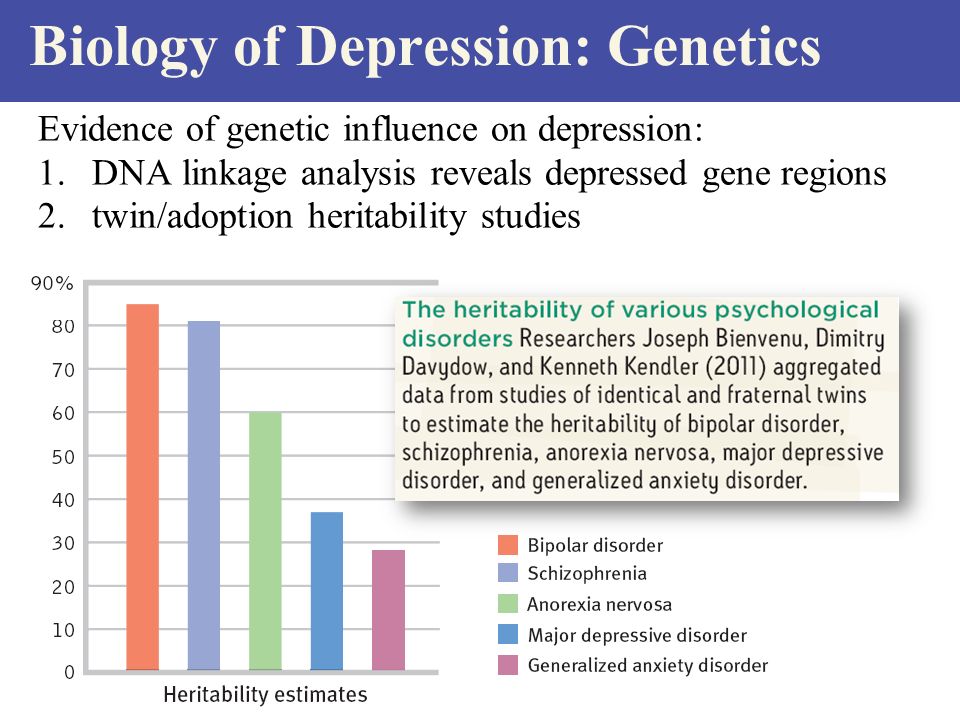

A bundle of factors contributes to a child's likelihood of developing anxiety. Roughly a third to half of the risk is genetic. But environmental factors also play a big part. Exposure to stress, including discord at home, poverty and neighborhood violence, can all lead to anxiety. Research has shown that women are much more likely than men to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder over their lifetime and that anxiety, as common as it is, appears to be vastly underdiagnosed and undertreated.

That's why it's important for parents, caregivers and teachers to spot it early. Be on the lookout for how long anxious feelings last. A few weeks, Pine says, usually isn't a cause for concern. "It's really when it goes into the one- to two-month range — that's where parents should really start . .. worrying about it."

.. worrying about it."

Here's another red flag: "Are there things that the child really wants to do or needs to be doing, and they can't do those things?" asks Krystal Lewis, a colleague of Pine's and a clinical researcher at the National Institute of Mental Health who provides therapy to anxious children. "If you feel you're hitting a wall in terms of trying to get the child to do those things, that might be another indicator that potentially, you know, we should get some help."

2. Be on the lookout for the physical signs of anxiety.

The worried feelings that come with anxiety can seem hidden to everyone but the child trapped in the turbulence. That's why it's especially important for grown-ups to pay close attention to a child's behavior and to look for the telltale signs of anxiety in children.

Anna, of Brampton, England, remembers when her 7-year-old son started having trouble at school. (We aren't using parents' full names to protect their children's privacy. )

)

"He was just coming home and saying his stomach hurt. He was very sick," Anna says. When she followed up with him to try to get to the root of his stomachache, she says, "he did tell me he was worried about school, and he told me specifically it was a teacher that he was worried about."

A stomachache, headache or vomiting can all signal anxious feelings, especially as a child gets closer to the source of the anxiety.

"You'll see that they'll have a rapid heartbeat. They'll get clammy, you know, because their heart is racing," says Rosemarie Truglio, the head of curriculum and content at Sesame Workshop. "They'll become tearful. That's another sign. ... Anxiety is about what's going to be happening in the future. So there's a lot of spinning in their head, which they're not able to articulate."

It's near this point of panic that Pine says a child's anxiety is most visible: "So you can see it in their face. There is a certain way the eyes might look. You can see it in behavior in general. People tend to either freeze, be inhibited not to do things when they're anxious, or they can get quite upset. They can pace. They might run away."

People tend to either freeze, be inhibited not to do things when they're anxious, or they can get quite upset. They can pace. They might run away."

Rachel, of Belgrade, Mont., says her 6-year-old son really doesn't want to swim or go to their local splash park.

"He just says there's too many kids in there. And he cries, and I've tried to go early in the morning when there's no one there. I mean, I've lost count of how many times we've driven by just to see if I could get him out of the car and he won't. And I'm not going to drag him."

We heard this from so many parents: My child is terrified to do something that I know won't hurt them, that they might actually enjoy. What do I do?

3. Before you try to reason with a panicked child, help the child relax.

"You're not going to be able to move forward until you get them to calm down," says Sesame's Truglio. "Because if you can't calm them down, you can't even reach them. They're not listening to your words because they can't. Their body is taking over, so talking and shouting and saying, 'You're going to do this!' is not very helpful."

Their body is taking over, so talking and shouting and saying, 'You're going to do this!' is not very helpful."

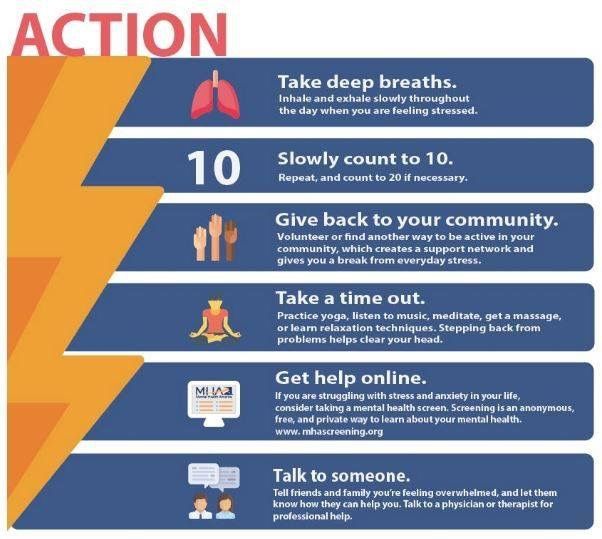

How do you break through this kind of panic? We recommend the Swiss Army knife in the mental health toolkit: deep belly breathing. Take a look:

NPR YouTube

Now that you've managed to calm down your child, it's time to ...

4. Validate your child's fear.

We heard from lots of parents who say they really struggle to know how to respond when their kids worry about unlikely things — especially if the fear is getting in the way of a busy daily routine, maybe a fun family outing or sleep.

"She comes down. It's 2 a.m. And she wakes me up," says Amber, of Huntsville, Ala., about her 8-year-old daughter. "And she said, 'I don't want to go away to college. I want to live at home for college.' And it's 2 a.m. ... That's when I really have to filter and not say, 'That is ridiculous. This is not a big deal!' "

I want to live at home for college.' And it's 2 a.m. ... That's when I really have to filter and not say, 'That is ridiculous. This is not a big deal!' "

Amber's filtered response was exactly right, says Truglio. Never dismiss a child's worries, no matter how irrational they may seem. A parent's priority, she says, should be "validating your child's feelings and not saying, 'Oh, you know, buck up. You can do this!' That's not helpful."

Lewis, of the National Institute of Mental Health, has language for parents who in the moment may feel frustrated by a child's behavior:

" 'I know that you're feeling uncomfortable right now. I know these are scary feelings.' You want to personify the anxiety, and so you can almost say, 'You know what, we know that this is our worry brain.' "

Lewis says it's crucial that children feel heard and respected. Even if you're pretty certain aliens aren't going to take over the planet tomorrow, if your child is worried about it, you need to let your child know that you respect that fear.

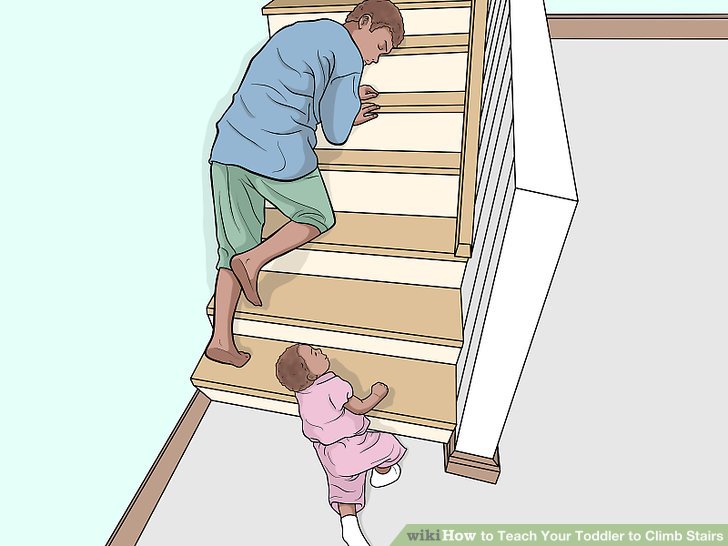

5. Help your child face their fears.

This is the fine line every parent, caregiver and teacher must walk with a child struggling with anxiety. You must respect the child's fear, but that does not mean giving in to the fear.

"I think our initial reaction when we see an anxious child is to help them and protect them and not to push them or encourage them to do the things that they're afraid of," Pine says. But, he adds, one of the things researchers have learned from years of studying anxiety in children is "how important it is to face your fears."

This might be hard for some parents to hear, but we heard it from every expert we interviewed. As to why it's important to face your fears, Lewis says, "the more that you avoid or don't do certain things, it's almost implicitly teaching the child that there is a reason to be anxious or afraid if we're not doing the things that are difficult. It's sending this message that, 'Oh well, there is potentially a dangerous component to this. ' "

' "

So it's important, Lewis says, "that children understand that things are gonna be difficult in life. Things can be scary. We can do them. ... I tell some of my patients, 'You can feel scared. That's OK. We're gonna do it anyway.' "

And Truglio agrees. While we do have to validate our kids' feeling of fearfulness, she says, "we can't always give in to this feeling. ... You need to push them a little bit. And there's this fine line: You can't push so far, because that's going to break them, right? They're going to fall apart even more."

How do we grown-ups find that fine line?

6. Build confidence with a baby-step plan.

Helping kids come up with a plan to face their fears is Lewis' job. It's called cognitive behavioral therapy, and a big part of that is exposure therapy.

Lewis says she once worked with an 8-year-old who was terrified of vomiting.

"We did a lot of practice, which included buying vomit spray off Amazon and vomit-flavored jelly beans," she recalls. "We listened to all types of fun vomit sounds using YouTube video. We did a lot of practicing up to the point where we created fake vomit, and we were in the bathroom and just pretending to vomit."

"We listened to all types of fun vomit sounds using YouTube video. We did a lot of practicing up to the point where we created fake vomit, and we were in the bathroom and just pretending to vomit."

And Lewis says that baby step after baby step, the girl made important progress.

"One of her peers had vomited in the classroom. And she comes into session, and she was just like, 'Someone vomited in my class, and I ran to the corner of the classroom' and was just like, 'I didn't leave the classroom!' ... She was very proud of the progress she was making. In the past, she would have run out of the classroom to the counselor's office and then missed school for, like, the next week."

Lewis says parents can use rewards to celebrate their kids when they make progress — think small but meaningful rewards like letting your child pick dinner that night or the movie for family movie night.

Obviously, these takeaways are just a starting point for concerned families. For more helpful takeaways about how to identify and manage childhood anxiety, Pine and Lewis recommend a handful of books:

- Helping Your Anxious Child: A Step-by-Step Guide for Parents, by Ronald Rapee, Ann Wignall, Susan Spence, Vanessa Cobham and Heidi Lyneham

- Outsmarting Worry: An Older Kid's Guide to Managing Anxiety, by Dawn Huebner

- What to Do When You Worry Too Much: A Kid's Guide to Overcoming Anxiety, by Dawn Huebner

- Anxious Kids, Anxious Parents: 7 Ways to Stop the Worry Cycle and Raise Courageous & Independent Children, by Reid Wilson and Lynn Lyons

If you feel overwhelmed by your child's anxiety, don't hesitate to ask for professional help — again, from your family's pediatrician or from a cognitive behavioral therapist. Because the good news is that anxiety is not only incredibly common but also treatable.

Because the good news is that anxiety is not only incredibly common but also treatable.

You can listen to this podcast episode, hosted by Anya Kamenetz and Cory Turner, here. Audio for this podcast episode was produced by Sylvie Douglis.

Children's anxiety. How to help an anxious child? | "Four-leaf clover"

Children's anxiety

Anxiety is commonly referred to as an increased tendency to experience apprehension and worry. In some situations, anxiety is justified and even useful: it mobilizes a person, allows you to avoid danger or solve a problem. This is the so-called situational anxiety. But sometimes anxiety accompanies a person in all life circumstances, even objectively favorable ones. That is, it becomes a stable personality trait. Such a person experiences constant unaccountable fear, an indefinite sense of threat. Any event is perceived as unfavorable and dangerous.

An anxious child is constantly depressed, on guard, it is difficult for him to establish contact with others, the world is perceived as frightening and hostile.

An anxious child is constantly depressed, on guard, it is difficult for him to establish contact with others, the world is perceived as frightening and hostile. Low self-esteem and a gloomy look at the future are constantly fixed.

Signs of anxiety:

- The child cannot work for a long time without getting tired

- He has difficulty concentrating on something

- Any occupation causes unnecessary anxiety

- During the performance of the task is very tense, constrained

- Embarrassed more than others

- Often talks about tense situations

- Blushing in unfamiliar surroundings

- Complains about having nightmares

- His hands are usually cold and damp

- He often has stool disorder

- Sweats profusely when excited

- Does not have a good appetite

- Sleeps restlessly, falls asleep with difficulty

- Shy, many things cause him fear

- Usually restless, easily upset

- Often unable to hold back tears

- Does not tolerate waiting well

- Doesn't like to take on new business

- Unsure of yourself and your abilities

- Afraid to face difficulties

Childhood anxiety at different ages

Preschool anxiety

It is often difficult for parents to understand why their child may be worried. Well, what problems can there be at his age: dressed, well-fed, the yard is full of friends, a lot of toys, loving relatives ?!

Well, what problems can there be at his age: dressed, well-fed, the yard is full of friends, a lot of toys, loving relatives ?!

However, the presence of childhood anxiety problems signals that in the life of a small person, not everything is as smooth as it seems to adults. This condition should never be ignored. In addition, it doesn’t matter if you have a son or a daughter, at this age anxiety does not depend on the child’s gender.

Anxiety is inherent in a person, regardless of age. In children from 1 to 3 years of age, the most common fears are caused by sharp loud sounds, sudden pain, for example, during vaccinations, and as a result, a negative reaction to doctors. In the age range from 3 to 5 years, anxiety in preschoolers often manifests itself in the form of fears such as fear of the dark, closed space, and loneliness. At the age of 5 to 7 years, fear of death is often added. If you notice anxiety in your child, in no case should you let this problem go by itself.

In the age range from 3 to 5 years, anxiety in preschoolers often manifests itself in the form of such fears as fear of the dark, closed space, loneliness. At the age of 5 to 7 years, fear of death is often added.

School anxiety

The age from 7 to 11 years can become very difficult. At this time, the child's life changes, he becomes an adult, he is entrusted with the mission of studying well, behaving correctly, being better, diligent, smarter than his peers.

Usually, anxiety manifests itself 1.5 months after the start of the school year, it is in connection with this that schoolchildren need rest - holidays from 1 to 1.5 weeks.

Usually, anxiety manifests itself 1.5 months after the start of the school year, it is in connection with this that schoolchildren need rest - holidays from 1 to 1.5 weeks.

Sometimes anxiety is related to more serious problems. So, with the help of a professional psychologist at the Four-Leaf Clover Clinic of Restorative Psychology, a child can be diagnosed with a mental disorder, neurosis at an early stage.

So, with the help of a professional psychologist at the Four-Leaf Clover Clinic of Restorative Psychology, a child can be diagnosed with a mental disorder, neurosis at an early stage.

Where does increased anxiety come from?

- If there is a constant anxious and suspicious atmosphere in the house. If the parents themselves are constantly afraid of something and worry about something. This condition is very contagious, the child adopts from adults an unhealthy form of reaction to everything, even to ordinary life events.

- If the child lacks information (or uses incorrect information). Try to keep track of what he reads, what programs he watches, what emotions he experiences. It is sometimes difficult for adults to understand how children interpret this or that event.

- Anxious children can grow up not only with anxious parents. The authoritarian style of parenting in the family also does not contribute to the inner peace of the child.

Parents who do not doubt and do not worry know exactly what and how to achieve in life. And most importantly - what they want to achieve from their child. Such a child must constantly live up to the high expectations of adults. He is in a situation of constant and intense expectation: he managed or failed to please his parents. It is especially difficult for a child if the demands and reactions of adults are unpredictable and inconsistent.

A child's internal conflict can be caused by:

- Contradictory demands made by parents or parents and the school (kindergarten). For example, parents do not let their child go to school because they feel unwell, and the teacher puts a “deuce” in a journal and scolds him for skipping a lesson in the presence of other children.

- Inadequate requirements, most often overstated. For example, parents repeatedly repeat to the child that he must certainly be an excellent student, they cannot come to terms with the fact that the child receives at school not only "five" and is not the best student in the class.

- Negative demands that humiliate the child, put him in a dependent position. For example, a caregiver or teacher says to a child: “If you tell me who behaved badly in my absence, I won’t tell my mother that you got into a fight.”

Experts believe that in preschool and younger preschool age boys are more anxious, and after 12 years - girls. At the same time, girls are more worried about relationships with other people, and boys are more worried about violence and punishment.

Having committed some “unseemly” act, the girls worry that their mother or teacher will think badly of them, and their girlfriends will refuse to be friends with them. In the same situation, boys are likely to be afraid that they will be punished by adults or beaten by their peers.

How to help an anxious child?

- Raise the child's self-esteem

To achieve success in this matter, it is necessary that an adult himself see the dignity of the child, treat him with respect (and not just with love) and be able to notice all his successes, even the smallest ones.

- Teaching a child to manage their behavior

It is necessary to teach the ability to manage oneself in situations that cause the greatest anxiety in the child

- Teach the child to relax

It is important for all children to be able to relax, but for anxious children it is simply a necessity, because the state of anxiety is accompanied by a clamping of different muscle groups.

It is very useful for such a child to attend group psycho-corrective classes - after consultation with a psychologist. The topic of childhood anxiety is well developed in psychology, and usually the effect of such activities is palpable.

Prevention of anxiety. Recommendations to parents.

- Communicating with your child, do not undermine the authority of other significant people.

For example, you can’t say to a child: “Your teachers understand a lot, better listen to your grandmother!”.

Be consistent in your actions, do not forbid the child for no reason what was allowed before.

- Consider children's abilities, do not demand from them what they cannot do.

If a child is given some kind of educational Subject with difficulty, it is better to once again help him and provide support, and when even the slightest success is achieved, do not forget to praise him.

- Trust your child, be honest with him and accept him for who he is.

If for some objective reasons it is difficult for a child to study, choose a circle for him to his liking so that classes in it bring joy to the child and he does not feel disadvantaged.

If parents are not satisfied with the behavior and success of their child, this is not a reason to deny him love and support. Let your child live in an atmosphere of warmth and trust, and then all his many talents will manifest.

If you have any questions on this topic, write or call us +7 (3822) 33–44–77.

Yours truly, Four Leaf Clover.

We wish you happiness and prosperity!

We recommend you specialists: Kupriyanova Irina Evgenievna, Zaichenko Tatyana Vladimirovna, Serykh Nadezhda Sergeevna, Glushko Tatyana Valerievna

← Previous | Next →

Child anxiety. 7 tips to cope with it

Nature has built in our body the ability to worry. Worry and anxiety are really useful when they push us to take action and solve problems. They cause a feeling of discomfort and this is normal: after all, we would hardly be saved in a dangerous situation if the experience of anxiety was similar to the state of inspiration when listening to our favorite song.

But if you are often preoccupied with thoughts like “what if?”, “something bad is going to happen”, “I have to control everything” and feel constant tension, then this anxiety becomes a problem. After all, you have to spend a lot of energy and time on it. It's like walking on level ground with the same effort as climbing steep stairs.

After all, you have to spend a lot of energy and time on it. It's like walking on level ground with the same effort as climbing steep stairs.

Chronic anxiety is a habit of thought that can be changed. And the good news is that you can train your brain, your behavior, change your attitude to experiences, to the very state of anxiety and open up new roads and horizons.

On the one hand, we may think that our constant anxiety can get out of control, drive us crazy or harm our health. On the other hand, that experiences help us avoid something bad, prepare for the worst, or come up with solutions to bad scenarios in advance.

"Worry about worry" adds strength to our experiences and keeps them going (just as worrying about falling asleep often prevents us from falling asleep). But positive beliefs about worry can be even more damaging. It's hard to break the habit of worrying if we think that worrying is protecting us. To stop worrying, we must give up our belief that constant worrying is justified and serves us well.

“After the birth of a child, I looked at the word “anxiety” in a new way”

Childbirth is a hormonal storm for the body, and after them, many diseases often either become aggravated or, on the contrary, disappear. Evolutionarily conditioned, in order to save the offspring, the mother needs to be more anxious, since the newborn cannot stand up for himself, and this is absolutely normal. Every day this need is decreasing, but many women (and men too) reinforce this pattern of behavior, which is also reinforced by social pressure. We all know the phrase “What kind of mother are you if you don’t worry about the child.”

“How not to worry? This is my child, I want him to grow up healthy and smart.”

Unfortunately, trying to protect the child from all dangers, we take away from him the ability to develop independence and self-confidence. Maybe the child will get higher grades, but how will this affect his life in the future?

Don't forget! Next to the need for security, another basic need of the child for AUTONOMY / INDEPENDENCE appears. According to statistics, children who grow up with anxious mothers, who often do not satisfy this need, achieve less in their careers, and also experience difficulties in their personal lives.

According to statistics, children who grow up with anxious mothers, who often do not satisfy this need, achieve less in their careers, and also experience difficulties in their personal lives.

Yes, many people show their concern and love with their anxiety, but do the children themselves feel it? Are there other ways to show your love to convey to your children?

"It's very easy to say don't worry, but how do you do it?"

Advice 1. Isolate yourself from the source of your anxiety for the first time.

Try to cut down on reading medical literature, drug instructions, “people's advice”, spend less time on forums. There are medical professionals who have been studying for about a decade and can filter the information that is useful from the information that is harmful to your child. Even the most illiterate doctor with the wrong treatment will provide better help than "traditional medicine" from the Internet.

Advice 2. Determine what you are experiencing and separate useful experiences from unhelpful ones.

An alarm is useful if:

- I can influence events or a problem;

— the theme of the experience is real, that is, what I worry about can happen in principle;

- there is a high probability that the event that I am worried about can happen.

If you have identified the experience as helpful, write a plan for solving the problem or describe how you will deal with the situation. If you can't fix the problem right away, schedule a time when you can.

If you have identified the experience as unhelpful, just let it go (but don't drive it away) and switch your attention to some activity. It is better if it is exciting and interesting. At first it will be difficult to do, but as you practice, it will become easier to let go of experiences and switch.

Advice 3. Set aside special time for worries and learn to postpone worry.

Create a "worry period". Pick a time and place for your worries (it shouldn't be bedtime) and clear them out of the rest of the day.

Put your worries aside. If an unsettling thought or worry pops into your head during the day, briefly state it and then move on with your day. Remind yourself that you will have time to think about this later, so there is no need to worry about it right now.

Allow yourself to experience only the amount of time you have chosen for your worry period. If these experiences don't seem important, shorten your worry period and enjoy the rest of your day.

In this way, you break the habit of dwelling on experiences when you have other things to do, but at the same time there is no “not thinking about the white monkey” effect.

Tip 3. Be realistic about the situation instead of suspecting danger in everything.

A few questions to help sort things out

- Are my predictions based on facts or feelings?

- Am I paying attention to all the information or just the negative part of it?

- How bad would it be if that happened?

- What is the worst thing that can happen in this situation?

- How can I deal with this?

- What happened in the past on such occasions?

Advice 4. Take your anxious thoughts as a false signal of danger.

Take your anxious thoughts as a false signal of danger.

It is better to write down the answers to these questions on paper

- What is the evidence that the thought is true? Is there any evidence that she is wrong?

- Is there a more positive, realistic way to look at the situation?

- What is the probability that what I fear will actually happen?

- What are the more likely outcomes?

- How often have I seen a negative outcome before? And how often did these predictions come true?

- How does experience help me? How do they harm me?

- What advice would I give to a friend in this situation?

Tip 5. Embrace anxiety instead of avoiding it.

In order to get rid of anxiety, we can resort to non-constructive and destructive ways of responding to experiences: overeating, scrolling social media feeds for a long time, getting angry at ourselves or avoiding situations associated with anxiety.

To overcome something, we have to go through it. Anxiety is not a threat at all, it is a passing reaction of your consciousness, it is not at all dangerous. Anxiety does not need to be controlled, it is not necessary to run away from it. It's like an alarm that's just set off by noise, and it'll go off on its own. When you stop giving your energy to anxiety, it will go away on its own. Instead of avoiding anxiety, treat it as a rewarding experience. Sometimes discomfort is our friend that tells us that we are moving forward.

Anxiety is not a threat at all, it is a passing reaction of your consciousness, it is not at all dangerous. Anxiety does not need to be controlled, it is not necessary to run away from it. It's like an alarm that's just set off by noise, and it'll go off on its own. When you stop giving your energy to anxiety, it will go away on its own. Instead of avoiding anxiety, treat it as a rewarding experience. Sometimes discomfort is our friend that tells us that we are moving forward.

Tip 6. Accept uncertainty.

The inability to tolerate uncertainty plays a huge role in experiences. Chronic worries cannot stand doubt or unpredictability. They need to know with 100% certainty what will happen. Anxiety is seen by us as a way to predict what awaits us in the future. This is a way to prevent unpleasant surprises and control the situation. The problem is that it doesn't work.

Thinking about all the things that could go wrong doesn't make life more predictable. You may feel more secure when you're worried, but that's just an illusion. At the same time, focusing on anxiety and worries about the future, it is unlikely that you will be able to enjoy the good, pleasant, pleasing that you have right now, in this present.

At the same time, focusing on anxiety and worries about the future, it is unlikely that you will be able to enjoy the good, pleasant, pleasing that you have right now, in this present.

Is it possible to be sure of everything in life?

What are the benefits and harms of complete certainty in life?

Is it possible to know in advance for sure about all the events that can happen to us?

Is it possible to live with the ignorance that something negative can happen, given the fact that the probability of this event is very low?

Think about what you do every day, already accepting uncertainty (meeting people, driving a car, eating at a party or catering, etc.)

Tip 7. Practice mindfulness.

Anxiety is usually focused on the future - on what might happen and what you will do about it. Mindfulness practices can help you let go of your worries by bringing your attention back to the present. Unlike previous methods of challenging your anxious thoughts or postponing them until a period of worry, this strategy is based on nonjudgmental observation.