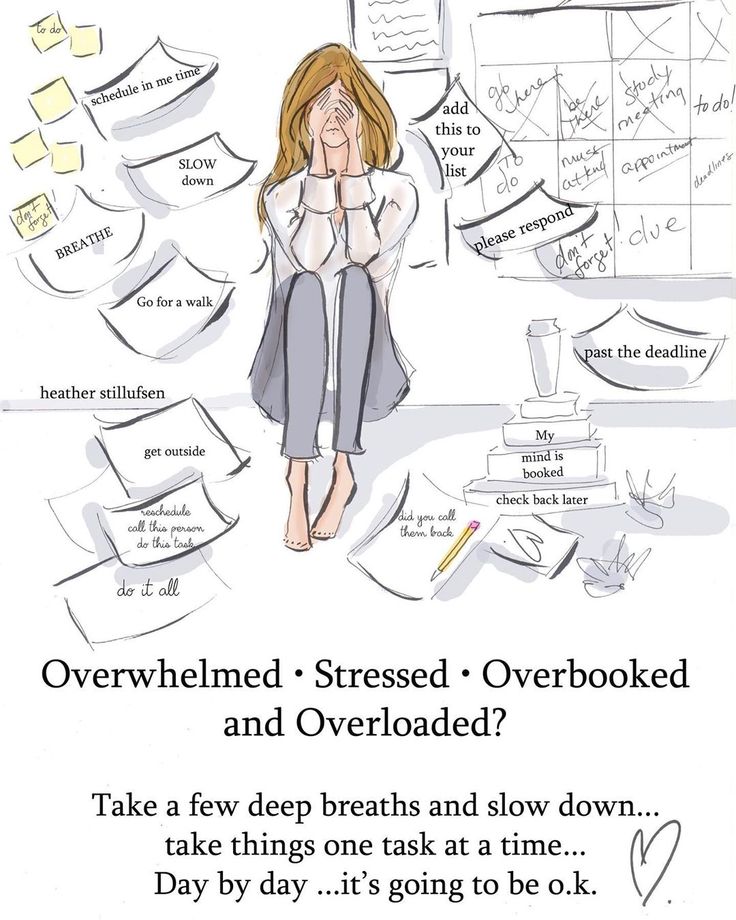

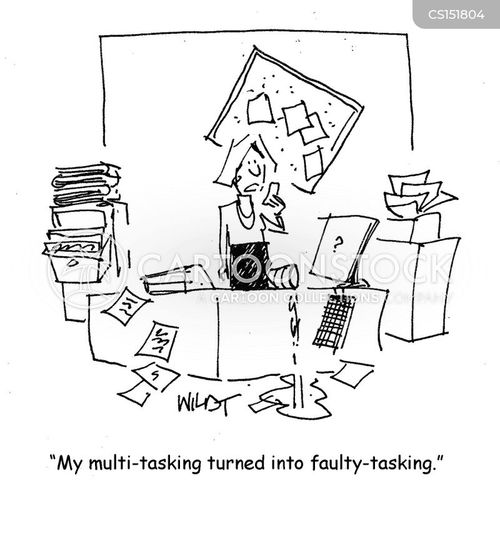

Simple tasks seem overwhelming

When Simple Tasks Become Like Mountains—How to Calm Your Anxious Thoughts | Anne Keating Counseling

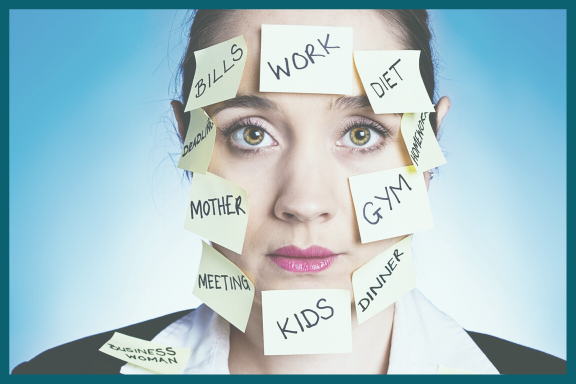

When you struggle with anxiety even small everyday tasks can seem like mountainous obstacles. As a result, you’ll start to feel even more overwhelmed and nervous because you can’t get things done.

That's because anxious thoughts tend to “blow up” even the smallest things. And so, something that would typically be easy to accomplish suddenly feels nearly impossible.

The worst thing is, these thoughts usually feed back on themselves, creating a vicious cycle—anxious thoughts leading to you feeling out of control and causing even worse thoughts, on and on. As a result, the mountain begins to grow until it becomes overwhelming.

Thankfully, there are practical things you can do in the moment to calm your anxious thoughts. While the situation may still be out of your control, being able to view it with a calmer state of mind can make it feel less overwhelming.

So, how can you calm your anxious thoughts and turn those overwhelming mountains into manageable hills?

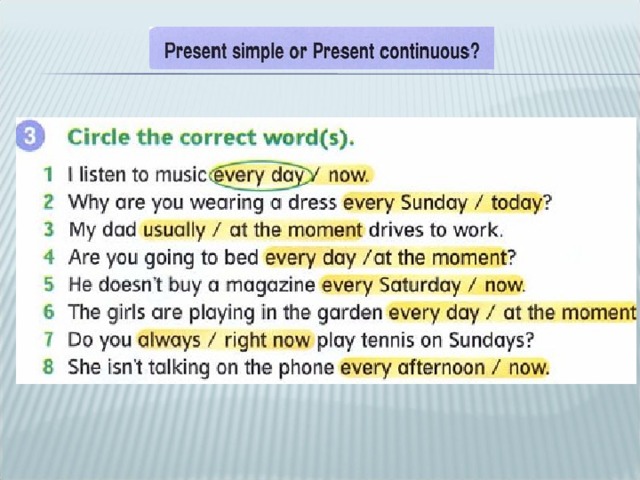

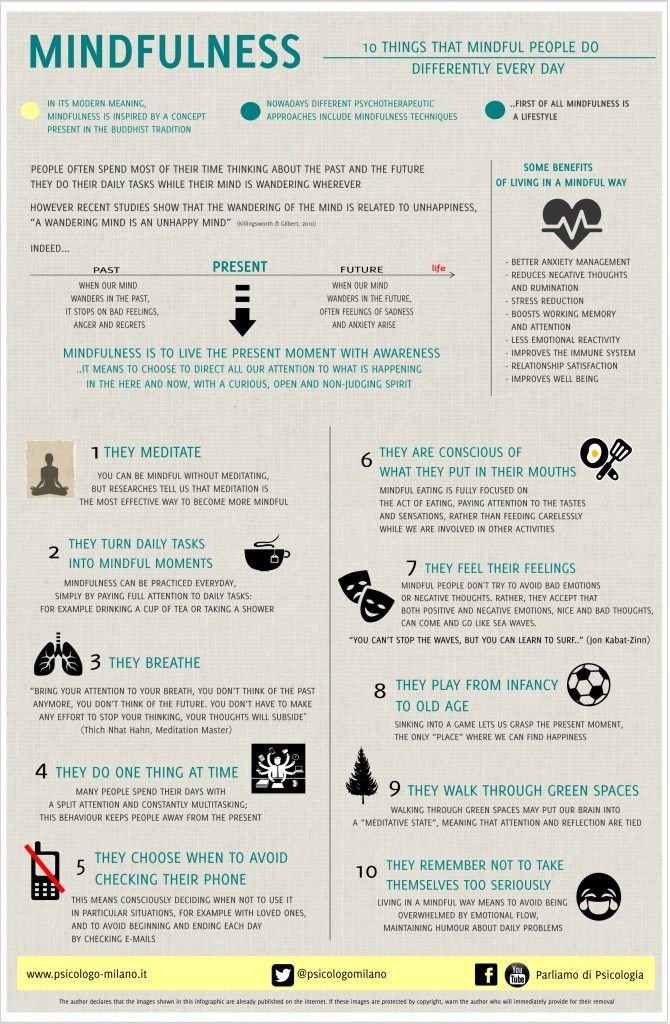

Stay Focused On the Present Task

When you’re dealing with anxiety, it’s easy to connect your thoughts with negative things that may have happened in the past, even if they were minor. So if your task is to wash the dishes, you may be mentally holding onto a time you dropped and broke a dish, or accidentally cut your finger, etc.

With any task you have to do, be mindful of the moment and don’t let your thoughts drift to past negative experience. Each task is a unique opportunity to get things done and move forward.

Think About the Positive Outcome

Many times, people with anxious thoughts will worry about all the things that could go wrong in a situation. These worries can encompass a very broad spectrum that ranges from something minor and annoying to something catastrophic.

Instead, try focusing your thoughts on the potential positive outcome of your task. Ask yourself what the best possible result could be and rely on that to get you through the task itself. Most of the time, getting things done throughout the day feels rewarding and can lead to a sense of accomplishment.

Be Kind to Yourself

You might think that not being able to do simple, everyday tasks is silly. As a result, you may start to criticize yourself or introduce negative self-talk. Unfortunately, that only makes matters worse and can even lead to other mental health issues, like depression.

As a result, you may start to criticize yourself or introduce negative self-talk. Unfortunately, that only makes matters worse and can even lead to other mental health issues, like depression.

Just because a task might be simple and mundane to someone else doesn’t take away the fact that it is difficult for you to overcome. So, show compassion and kindness to yourself as you work through these daily “mountains." Encourage yourself and work on boosting your confidence, rather than tearing yourself down.

Trust Yourself

As you start to show more compassion toward yourself and your anxiety, you can begin to trust yourself as well.

When you’re feeling anxious about getting something done, think about a time in the past where you completed that task, or something similar to it. How did you feel when you were done? Was there something you could have done better? What was the best outcome? Relying on your positive past experiences of completing a task can give you the self-trust you need to get through it once again.

--

It’s far too easy for anxious thoughts to take over your mind when you’re dealing with everyday tasks. While there are many ways to help manage these thoughts and get you through your daily tasks, one of the best things you can consider is participating in professional counseling or therapy.

Counseling for anxiety can teach you even more ways to manage your negative thoughts. And that often makes each day a bit easier than the last.

If you’re struggling with anxiety, feel free to set up an appointment with me. We can work on calming those anxious thoughts, making simple tasks feel less mountain-like and calming your anxiety in general so you can get back to living and enjoying your life.

You’re Not Lazy! You Could Be Stuck on the Impossible Task

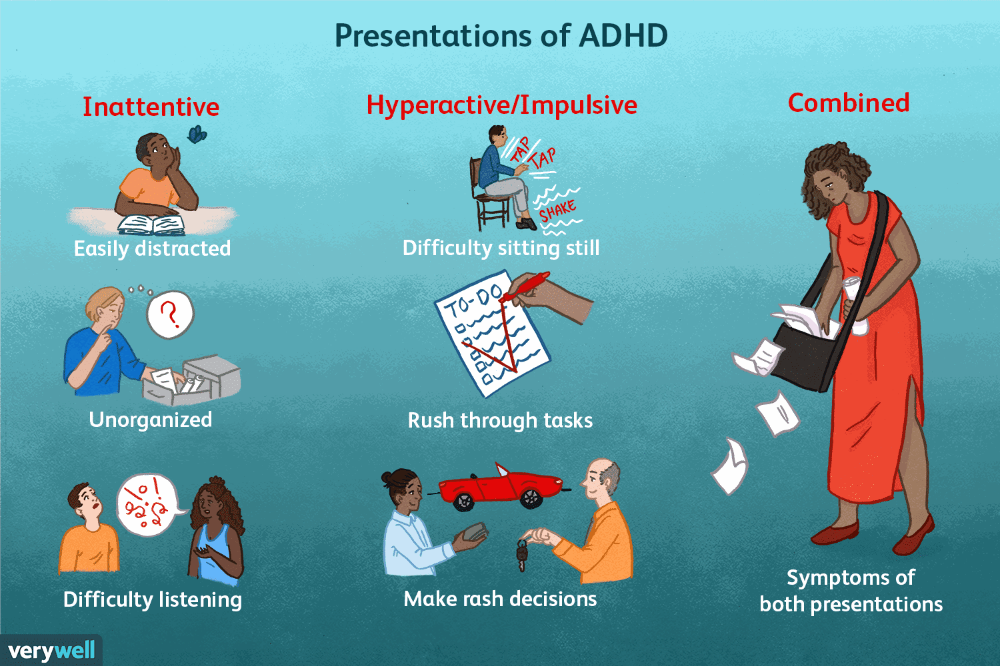

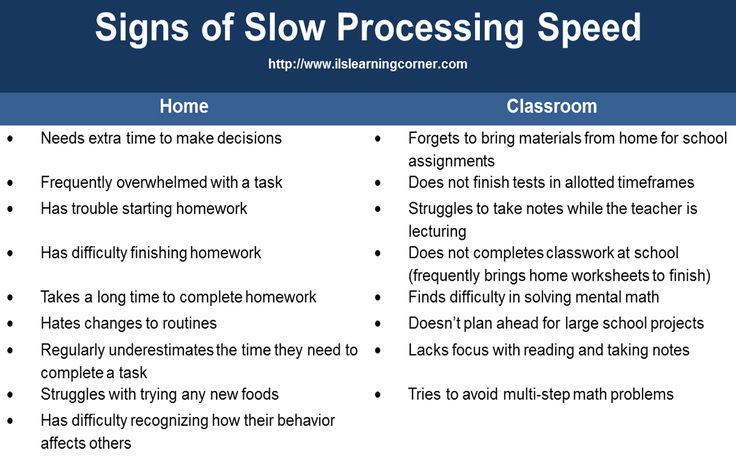

Many of my clients suffer from being overwhelmed by the thought of doing even the simplest tasks. This is an often overlooked but very common symptom for people with depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), bipolar disorder, and other mental health problems.

Sometimes the impossible tasks are things they can’t get themselves to do because they dread doing them even though they were previously able to motivate themselves. Things like paying bills, scrubbing the kitchen floor, doing the dishes, or sorting paperwork for taxes. These tasks loom larger now as they do not feel well enough to do them. Sometimes “the impossible tasks” are things the person would really love to do but are unable to get motivated to do. Things like playing with their pet, exercising, calling friends, carrying out job tasks, and picking up the messy house so it’s a more pleasant place to live. They’re unable to do even these desired tasks.

When even a simple task seems impossible, author M. Molly Backes called this The Impossible Task. How is that possible? Like everything else about our mental and physical health – it’s a brain thing. In this case, it’s about motivation. But wait, my clients protest. They tell me the frustrating thing is that they are motivated to do these tasks … until it is time to do them. The day goes by and the dishes remain undone. So let me explain some of the relevant aspects of motivation.

The day goes by and the dishes remain undone. So let me explain some of the relevant aspects of motivation.

If you’re stuck on The Impossible Task(s) hopefully this explanation about motivation and the brain will offset the guilt, shame, disappointment, and confusion you’re feeling. If you’re reading this because it sounds like someone you care about, I hope it will help you understand that they are not “lazy.” This is something very different. They don’t understand it either. It’s not that they just don’t want to do something or can’t be bothered. Doing The Impossible Task(s) literally feels like the most difficult thing in the world.

As you will see this feeling is not their fault. They aren’t lazy. It’s a symptom of their mental illness for which they need tolerance and compassion from those who love them.

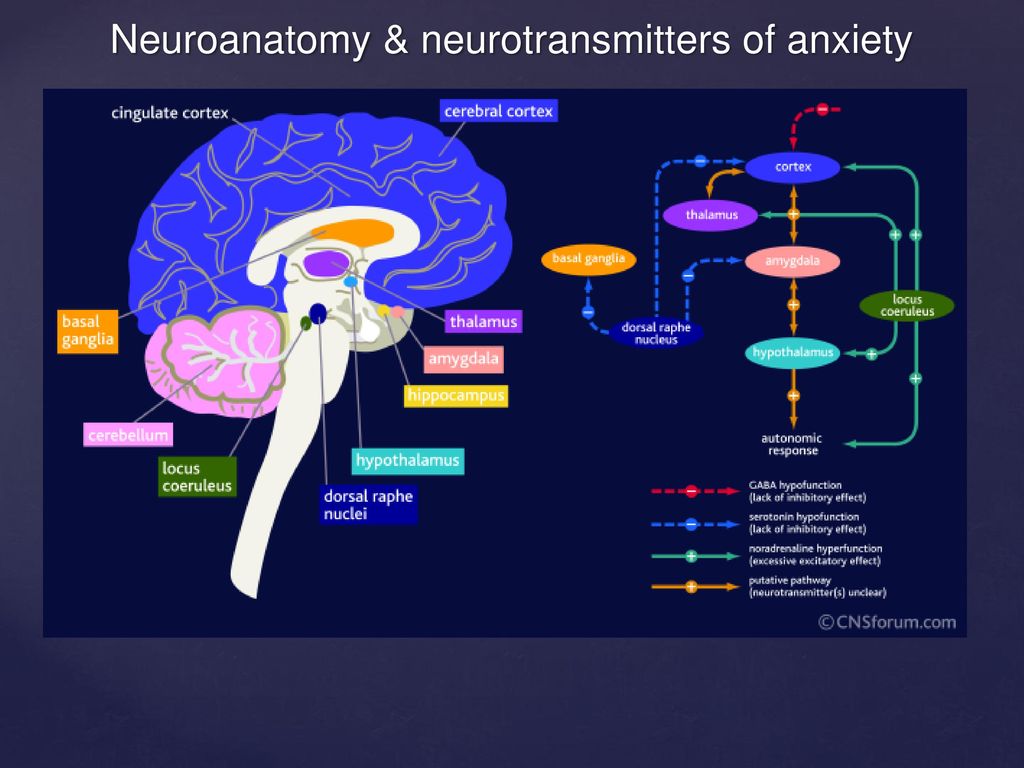

Motivation and the Brain

There are many possible reasons for not feeling motivated. Everything from dreading negative consequences to finding something unpleasant to being too tired, injured, physically unable, or being in too much physical pain, fearing failure or negative reactions, just to name a few. But as anyone stuck in The Impossible Task knows, this is something different. This is not about any of the customary reasons for choosing to put off or not do something. This is about not being able to do very much at all.

But as anyone stuck in The Impossible Task knows, this is something different. This is not about any of the customary reasons for choosing to put off or not do something. This is about not being able to do very much at all.

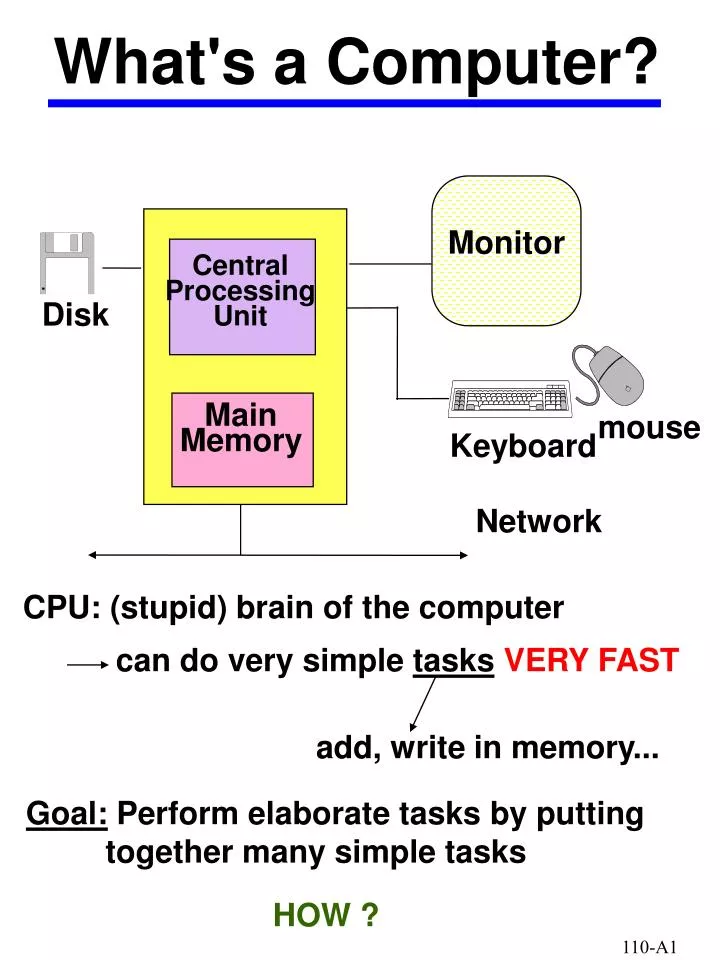

As neuroscientist Dr. Alex Korb explains in his book The Upward Spiral, the motivation to act is “the result of a conversation between three parts of the brain: the pre-frontal cortex, the nucleus accumbens,and the dorsal striatum. The prefrontal cortex [the only one of the three involving conscious intention] chooses what to do based on what’s good for us in the long term and creates new action. The nucleus accumbens chooses what to do based on what’s most immediately pleasurable [and thus motivates us to do it]. The dorsal striatum chooses what to do based on what we have done before,” habits we do routinely with little thought.

All three of these areas of the brain depend heavily on an ample supply of dopamine, the pleasure-providing neurotransmitters. In the case of The Impossible Task, due to the state of one’s brain, none of these areas are getting enough dopamine to motivate us to act. As crude and overly simplified as this comparison is, you can think of dopamine as the gas that runs a car engine. The person suffering from The Impossible Task is out of gas. The tank is empty. When they try to step on the gas, nothing happens.

In the case of The Impossible Task, due to the state of one’s brain, none of these areas are getting enough dopamine to motivate us to act. As crude and overly simplified as this comparison is, you can think of dopamine as the gas that runs a car engine. The person suffering from The Impossible Task is out of gas. The tank is empty. When they try to step on the gas, nothing happens.

In Depression. In the case of depression, the lack of available dopamine, and Serotine, another feel-good neurotransmitter, causes serious problems with motivation. The lack of dopamine in the prefrontal cortex means there is not enough energy to weigh options, make decisions, solve problems and take action.

Lack of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens means things that used to be enjoyable no longer are. This state is called anhedonia, not taking pleasure in anything. It too is very common in depression, like a man who enjoyed caring for and riding his horse every day but became unable to get to the stables. He felt terrible about this, ashamed, guilty, and fearful of harming his horse. At night he tells himself tomorrow will be different. Tomorrow he will go. But tomorrow he can’t.

He felt terrible about this, ashamed, guilty, and fearful of harming his horse. At night he tells himself tomorrow will be different. Tomorrow he will go. But tomorrow he can’t.

Without enough dopamine, in the dorsal striatum, we don’t have the wherewithal to do even the routine tasks we once did automatically day in and day out without thinking. Like the woman who has done her dishes after eating all her life but now can’t “get to them.” To her embarrassment, they are piling up in the sink for days. Without dopamine in the dorsal striatum, she isn’t motivated to do anything.

In Anxiety and Panic. In the case of anxiety and panic, the brain is sending out an alert that a threat is present. Without sufficient dopamine and serotonin, the prefrontal cortex cannot intervene to check out the validity of that threat, calm the activated parts of the brain and take any needed problem-solving action. We remain on high alert and can either take the fight, flight or freeze. When we freeze we are essentially immobilized and can do nothing, but we may get stuck in incessant worry and rumination. With flight, we avoid doing anything but protecting ourselves from an ambiguous threat. Sometimes this means escaping into substance abuse or other addictive behaviors.

When we freeze we are essentially immobilized and can do nothing, but we may get stuck in incessant worry and rumination. With flight, we avoid doing anything but protecting ourselves from an ambiguous threat. Sometimes this means escaping into substance abuse or other addictive behaviors.

In ADHD. In the case of ADHD, the harder a person tries the less blood flow, oxygen and needed neurotransmitters are available to the prefrontal cortex to carry out the tasks at hand. Since proper prefrontal functioning is required to create a new action, the person with ADHD becomes disorganized and discouraged and eventually gives up trying to do anything about what needs doing. Parents and teachers often don’t understand how truly impossible doing homework or chores can be for ADHD children. Without dopamine to fuel the nucleus accumbens, this lack of motivation extends even to things that were once enjoyable if they become more challenging as participating in a sport at a higher age level.

People with ADHD are often motivated by impulse or highly stimulating and pleasurable things, confusing others all the more. If they can do that, why not their schoolwork? But that kind of motivation is activated from the nucleus accumbens, not the prefrontal cortex. It’s impulsive. Thus we can see thoughtless, even dangerous, behavior and choices. This doesn’t change their difficulty with The Impossible Task, however, because those tasks are not usually highly stimulating or tremendously enjoyable.

Chronic vs. episodic. For most of my clients, feelings of The Impossible Tasks is a chronic condition. It continues throughout the period of their illnesses. When they improve, it improves too. But there are many factors determining dopamine levels from genetics to levels of other neurotransmitters, environmental conditions, food, supplement, mood, sleep, exercise, drugs physical health, and even social standing to name a few. This means

that incidents of the feelings of the Impossible Task may come and go for some people. Struggling on some days or for briefer periods and not on others. This fluctuation can make it harder for us to understand or predict what we will be able to do. It also confuses others who don’t understand. If you did things like the other day, why can’t you do this today?”

Struggling on some days or for briefer periods and not on others. This fluctuation can make it harder for us to understand or predict what we will be able to do. It also confuses others who don’t understand. If you did things like the other day, why can’t you do this today?”

Getting Past the Impossible Task.

As with any aspect of mental illness, there are many approaches that can help manage the workings of the brain that keep us stuck on The Impossible Task. An approach that will work for one person with one type of condition may not work for another person with a different condition. I can help you find the right one for you. Here are several things I and other therapists have found helpful I’d like to share now

First, let me tell you about some things that seem to others would be helpful but that my clients have found to only be marginally helpful or not helpful at all. These suggestions tend to make them feel worse because they can’t do them either. You have probably tried them and wondered why these ideas work for other people but not for you.

You have probably tried them and wondered why these ideas work for other people but not for you.

Here is a definition: ‘Pairing a task with something pleasant?

Not Usually Helpful.

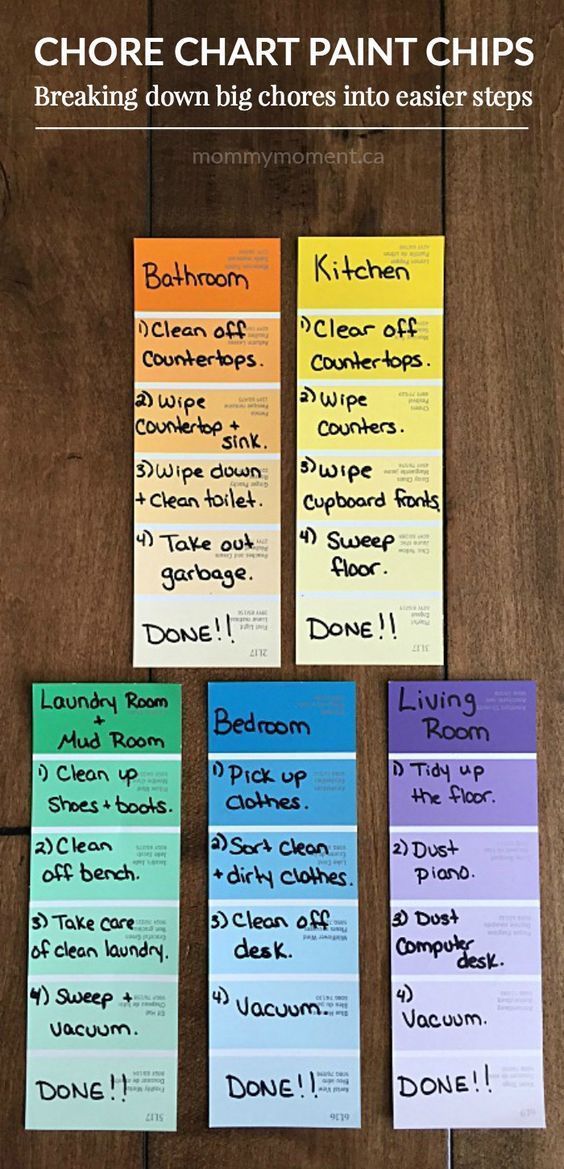

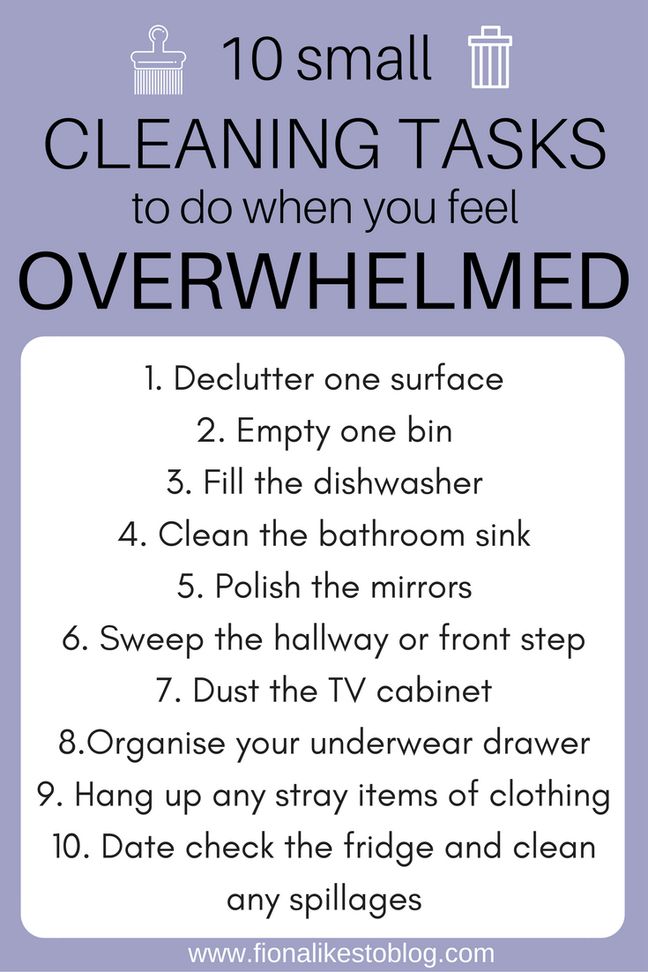

As mentioned above, people have myriad reasons for not being motivated to do certain daunting tasks. The following suggestions are often helpful for people who are overwhelmed by the enormity of difficulty of specific tasks, like packing or unpacking to move, writing a term paper, or doing the taxes. But my clients who are stymied by doing even simple tasks they have done successfully at other times and even really want to do but can’t, have not found them helpful.

Breaking tasks down into smaller pieces can be helpful for people who are dealing with The Impossible Task. Instead, of aiming to clean up a messy kitchen, setting a goal to just clear the kitchen table might help them get started. Here is an example of a woman for whom that was helpful. She was responsible for clearing out her mother’s entire household upon her death all by herself. She was overwhelmed and anxious about this but her motivation, in general, was not the issue. She was able to do other things that needed doing like driving to pick up prescriptions, making needed personal phone calls, doing her job, etc. She just didn’t know how to tackle this enormous responsibility. Breaking the tasks down in one small step at a time was helpful, i.e. starting with her mother’s clothes closet, and then moving on to small segments.

She was responsible for clearing out her mother’s entire household upon her death all by herself. She was overwhelmed and anxious about this but her motivation, in general, was not the issue. She was able to do other things that needed doing like driving to pick up prescriptions, making needed personal phone calls, doing her job, etc. She just didn’t know how to tackle this enormous responsibility. Breaking the tasks down in one small step at a time was helpful, i.e. starting with her mother’s clothes closet, and then moving on to small segments.

My clients who are stuck on The Impossible Task do not find this helpful. They find themselves as unable to do a small task at times as a larger one.

Paring a task with something pleasant. To use the house-cleaning example again, listen to your favorite music or while watching a favorite show while cleaning. This might be helpful for people with other types of motivation issues but my clients don’t find it helpful with The Impossible Task. They can usually listen to their favorite music, do puzzles online or sometimes watch a show, but these things don’t help them get on with The Impossible Task.

They can usually listen to their favorite music, do puzzles online or sometimes watch a show, but these things don’t help them get on with The Impossible Task.

I often find that for my clients any idea of doing anything with another person becomes another Impossible Task. It’s not an appealing idea either because of the embarrassment they already feel about not being able to do things or because calling a friend is itself an Impossible Task. Take the man who was distressed about not being able to get out to ride his horse. In the session, we agreed that arranging to ride with a friend might help him to get to the stables. Oops. Bad idea. Although riding with his friend had always been enjoyable before not anymore. When his friend called to ask about riding together, they set a day to meet, but that morning he couldn’t get himself to go out. He was humiliated and more depressed than ever to have stood up to his friend.

Making suggestions like this forgets that when it comes to The Impossible Task even pleasurable tasks are impossible. I’ve found that the disappointment and shame of trying to do pleasurable things make matter worse. One client was indignant. She told me, “Don’t you think that if I could do that I would have?” I haven’t suggested it again.

I’ve found that the disappointment and shame of trying to do pleasurable things make matter worse. One client was indignant. She told me, “Don’t you think that if I could do that I would have?” I haven’t suggested it again.

Promise yourself a reward. Again, this is a great idea for motivating someone who has other reasons for not doing something, but not with The Impossible Task. If you remember there is no, or not enough, gas in the engine to kick start the motivation to act. That would hold true for either the task or the reward. Those who have never faced the Impossible Tasks tend to keep thinking that somehow those facing this have control over their problem.

Remind yourself of how much you enjoyed doing or having completed the task in the past. The idea here is that remembering how much you had once enjoyed something will motivate you enough to do it now. This is perhaps the worse suggestion anyone can make to someone facing The Impossible Task. Most likely they already too often remember what they once enjoyed and feel really awful that it isn’t that way anymore.

Awful that now they can’t enjoy the task or the feelings of accomplishment they once had doing these tasks.

It can be heart-breaking.

Usually Been Helpful

Here are a number of things that my clients do find helpful in dealing with The Impossible Task.

Having a physical and mental evaluation and getting needed treatment.

I begin with this as a first step to overcoming The Impossible Task because fatigue and an inability to motivate oneself can be symptoms of other physical and psychological illnesses. Unless you know what is causing this problem you can’t begin the road to recovery. Fatigue and lack of motivation are symptoms of autoimmune diseases like fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue, and multiple sclerosis, thyroid deficiency, heart problems, and many others. As mentioned above, it is also a symptom of many psychological conditions, something as common as burnout.

Often when my clients first come to see me they do not have a clear diagnosis or an understanding of the nature of their diagnosis. They especially don’t know what is going on in their brain to cause their symptoms and how they can help their brain function better. In addition, in psychotherapy tailored to that condition, there may be a medication that can help or they may need a change in their medication. I’ve found that medication does not always help, though, and in some situations causes or contributes to their problems with motivation. With a thorough physical evaluation and the right psychological diagnosis, I can help you heal or manage your illness. Once you can do that, you will not be stuck in the Impossible Task, at least not as often or for as long. Should it hit, you’ll be able to get out of it.

They especially don’t know what is going on in their brain to cause their symptoms and how they can help their brain function better. In addition, in psychotherapy tailored to that condition, there may be a medication that can help or they may need a change in their medication. I’ve found that medication does not always help, though, and in some situations causes or contributes to their problems with motivation. With a thorough physical evaluation and the right psychological diagnosis, I can help you heal or manage your illness. Once you can do that, you will not be stuck in the Impossible Task, at least not as often or for as long. Should it hit, you’ll be able to get out of it.

When the man who wasn’t able to get to the stables to see his horse had a thorough physical evaluation, it was discovered he had sleep apnea in addition to other medical issues. Once he got these conditions treated he got to the stables. He still had problems with anxiety attacks, but we continued to work on helping him manage those and he no longer spends the majority of his days sacked out on the couch. He’s getting a lot of things done that he simply wasn’t able to do.

He’s getting a lot of things done that he simply wasn’t able to do.

Understanding and accepting that you are not to blame.

Remember, this is a symptom of your condition. You are not choosing it. It is not a flaw in your character. You are not lazy. This problem is the result of your illness and what it’s doing to your brain. This knowledge will hopefully free you from feeling ashamed, guilty, or embarrassed. This is a symptom of a physiological condition, like any other. We don’t feel guilty if we have a problem with our lungs or our heart. You need not feel guilty because you’re having a problem with your brain. It is, after all, the most complex part of our body. Of course, you are disappointed and saddened but please don’t feel shameful. Blessedly this needn’t be a permanent condition. As your mental or physical condition is treated, you will most likely be able to return to

Be compassionate to yourself.

Extensive research is showing that compassion has a powerful ability to heal mental and physical distress..jpg) Compassion goes beyond empathy when you feel for someone. Compassion also includes the ability to sit comfortably with the person who is suffering and take some kind of action to help them. That might simply be a kind word, a caring touch. Or it could be listening to their thoughts and feelings, sharing your supportive thoughts, or offering to help them. What would you do for your friend or loved one?

Compassion goes beyond empathy when you feel for someone. Compassion also includes the ability to sit comfortably with the person who is suffering and take some kind of action to help them. That might simply be a kind word, a caring touch. Or it could be listening to their thoughts and feelings, sharing your supportive thoughts, or offering to help them. What would you do for your friend or loved one?

Now comes the challenge. It’s time to do things like that for yourself. But how? For one thing, understanding that you are not well and using kind instead of critical self-talk … repeatedly and often.

You might say to yourself, ”I can see you are hurting, that you feel bad about yourself. I’m sorry. You don’t deserve this. It is not your fault.” Or

“I know you are doing the best you can and I am proud of you for getting counseling and seeing your doctor. I know how difficult that is for you.” Or

“I know this seems endless and overwhelming, but when you get the help you need for your illness(es) you won’t feel like this. ”

”

Stating that you are in a difficult, unpleasant situation is a reality check that can help you to sit with your discomfort and allow it to be while you comfort yourself.

Releasing yourself from guilt and expectation

Clients tell me the most compassionate thing they can do is to release themselves from feeling ashamed and to quit expecting themselves to be able to “get over it,” as others may have told them. They say that knowing this is not their fault, but rather a symptom of an illness frees them from self-blame and criticism. They feel free at last to be at rest knowing they don’t have to do what they can’t do.

Allowing yourself to do what you can do without criticism and praising yourself is a caring gift you can give yourself. If you find solace in watching TV, that’s good. If you are taking care of your pets despite your condition, praise yourself for this. If you feel better sleeping late or going back to bed, allow yourself to do that. Remember as you get needed treatment, this probably won’t be forever. It’s like having a broken leg. While your leg is healing, there are many things you can’t do. But as it gets better, you can do more and more and eventually probably everything you once did.*

It’s like having a broken leg. While your leg is healing, there are many things you can’t do. But as it gets better, you can do more and more and eventually probably everything you once did.*

for example, free in the way the woman who had been so upset about her piled-up dirty dishes, was able to accept her daughter’s offer to wash the ones in the sink. She then got out her paper plates and cups she could just toss out. She had some initial resistance to this solution because she didn’t think it wasn’t environmentally responsible. But I reminded her again, that this is temporary. It was like what she’d done when the family went on camping trips.

Ask what’s the worst thing that could happen if I don’t do this today? Can I live with that?

When clients are really fretting about something they can’t do, they have told me that asking these two questions is helpful. First, they can usually see that the worst thing is not going to happen but even if it did, they may not like it, but they can live with it. This seems to make it easier for them to let themselves off the hook of The Impossible Task. Recently a client was dismayed about not doing the laundry. When she asked these questions in her session, she began to laugh. She has other clothes and if necessary could wear something again that wasn’t washed yet. That put a stop to her dismay. Everything would be fine.

This seems to make it easier for them to let themselves off the hook of The Impossible Task. Recently a client was dismayed about not doing the laundry. When she asked these questions in her session, she began to laugh. She has other clothes and if necessary could wear something again that wasn’t washed yet. That put a stop to her dismay. Everything would be fine.

Clearly doing the laundry is a good task but your worth as a person isn’t tied to having clean laundry today. If there are crucial tasks that are going undone, such as making important doctor appointments, filing to keep disability income, or paying a bill to keep the lights on that’s another matter and the next idea can save a lot of future problems.

* In the case of some chronic or degenerative physical conditions The Impossible Task may continue to be a challenge that requires additional levels of acceptance and compassion counseling.

Asking or paying for help.

Asking for help is a problem for many people. In this case, though, asking for help is a real test of how well you’re doing at accepting that you have a symptom of a serious illness. No shame, no embarrassment for being ill. Chances are you’ve been a competent, independent person before your illness but consider this: if you had fallen and were at home recovering from two broken legs or from major surgery would you expect yourself to manage your daily tasks all by yourself? Goodness, I hope not. That would be impossible. Sound familiar? The Impossible Task.

In this case, though, asking for help is a real test of how well you’re doing at accepting that you have a symptom of a serious illness. No shame, no embarrassment for being ill. Chances are you’ve been a competent, independent person before your illness but consider this: if you had fallen and were at home recovering from two broken legs or from major surgery would you expect yourself to manage your daily tasks all by yourself? Goodness, I hope not. That would be impossible. Sound familiar? The Impossible Task.

I know that mental illness can be a little different. Mental illness is considered an invisible illness in that a person can look perfectly capable but not be. And sadly some unenlightened individuals still harbor harmful stereotypes or even deny the existence of mental illness. You may need to let your loved ones know that you are ill and are working on recovering. (That’s assuming you are in counseling, consulting with your doctor, and following their directions).

I also know that getting help is easier for some people than for others. For the lucky ones, loving and supportive friends and family simply step forward to help take care of matters. No request is needed. In that case, just make sure you don’t turn them away. `But you’re not lucky and friends and family don’t offer, you owe it to yourself please ask those who care about you, i.e.:

For the lucky ones, loving and supportive friends and family simply step forward to help take care of matters. No request is needed. In that case, just make sure you don’t turn them away. `But you’re not lucky and friends and family don’t offer, you owe it to yourself please ask those who care about you, i.e.:

“Darling, would you be willing to take the dog out in the morning until I’m feeling better? I wish I could

do it and I will as soon I can.”

“Son, would you be able to come by and take this check to the electric company?”

“Connie, do you think you could help me with these disability forms? They are sort of overwhelming and I need to get them in to keep getting my disability check while I’m so ill.”

“Daughter, would you please be willing to make these appointments for me?”

Some of my clients don’t have nearby family or friends who they can ask to help. Isolation is another serious symptom of depression and other illnesses. In such cases, I urge them to hire some help if they can. Cleaning is a particularly good task to hire out, even if it’s just once a month. Catching up on housework and having a neat, clean house can be a real mood lifter. Many cleaning services will do laundry, change bedding and take the trash.

Cleaning is a particularly good task to hire out, even if it’s just once a month. Catching up on housework and having a neat, clean house can be a real mood lifter. Many cleaning services will do laundry, change bedding and take the trash.

Whoever can step in to help, be sure to accept that they are going to carry out their help in their way. It may – probably – won’t be exactly the way you do and you may not think it’s done as well as you would do, but accept their efforts and thank them profusely.

Take tiny baby steps and watch out for the word “Can’t”

One of my disabled clients who struggles both physically and mentally with The Impossible Task offered these suggestions. She agrees that breaking big tasks into little tasks is just as impossible for her as trying to do the whole thing. But what she finds she can do is to do at least one teeny, tiny task each day. She may not be able to make her bed some mornings. That is something she prides herself on doing but when she feels too stuck she sets the tiny goal to get out of bed. If she is unable to take a shower, wash, style her hair and get dressed, she sets a tiny goal to take a quick sponge bath and have a “pajama day.” She feels pleased that she can do these tiny tasks. And it keeps away feelings of failure she might otherwise feel.

If she is unable to take a shower, wash, style her hair and get dressed, she sets a tiny goal to take a quick sponge bath and have a “pajama day.” She feels pleased that she can do these tiny tasks. And it keeps away feelings of failure she might otherwise feel.

She is also cautious about using the word “can’t” with people. Many people have heard the word “can’t” as meaning “won’t.” Again they are assuming the person is making a choice not to do their tasks. This type of word substitution can be helpful with people who do not own that they actually can do something but are unwilling to. That is not the situation here, so she avoids the word “can’t” and replaces it with “unable.” She finds people are more accepting of that word. If both legs are in a cast one is unable to climb the stairs.

One final suggestion: Challenge leftover ANTs and let them pass.

When we’re depressed, anxious, or suffering from other challenges we don’t always remember to be compassionate and kind to ourselves. Even after fully knowing that we deserve it, that we’re not lazy, that we have nothing to be ashamed of, and that we are recovering, nonetheless, automatic negative thoughts may creep into our minds unbidden. They pop out from our primitive limbic brain. We are not in charge of the random thoughts from our primitive brain and unfortunately many limbic thoughts lean toward the negative and are outrageously untrue. But fortunately, we can dismiss them or if they are too stubborn to dismiss, we can challenge them by asking questions that derail them. Here are some powerful ones.

Even after fully knowing that we deserve it, that we’re not lazy, that we have nothing to be ashamed of, and that we are recovering, nonetheless, automatic negative thoughts may creep into our minds unbidden. They pop out from our primitive limbic brain. We are not in charge of the random thoughts from our primitive brain and unfortunately many limbic thoughts lean toward the negative and are outrageously untrue. But fortunately, we can dismiss them or if they are too stubborn to dismiss, we can challenge them by asking questions that derail them. Here are some powerful ones.

1. Is that true? Really? According to whom?

2. How do I know that?

3. Because something was true once does that mean always the case?

4. Because something wasn’t possible once, is it never possible?

Am I sure? 100%? What evidence do I have?

6. Do I have a crystal ball?

7. Is it really that bad?

8. Is there another way to see it?

9. How will I act if I believe this?

10. Who would I be without this thought? How would I act?

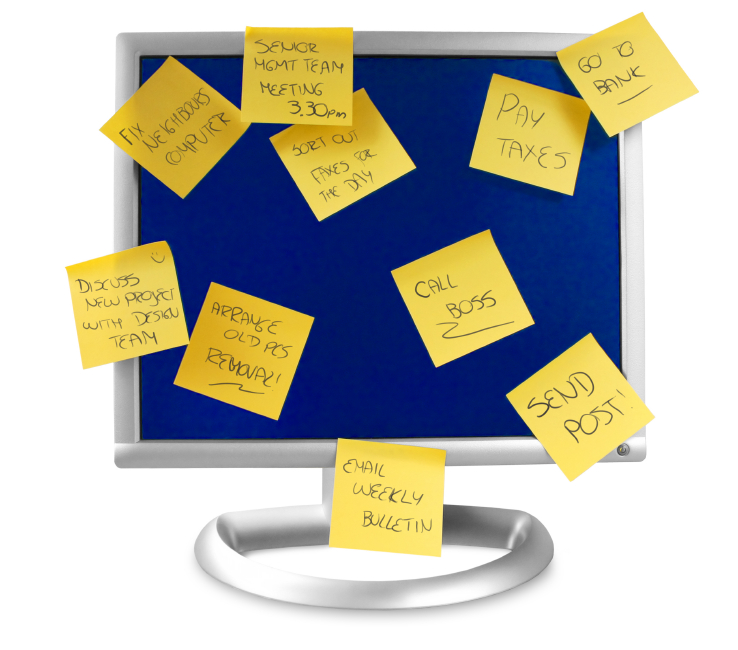

To cue yourself, post these questions on your refrigerator, your desk, or by your bed. They are usually most rampant at night when we’re trying to lie quietly in bed to go to sleep. Take them on and then dismiss them. Let them pass. Remember:

They are usually most rampant at night when we’re trying to lie quietly in bed to go to sleep. Take them on and then dismiss them. Let them pass. Remember:

You don’t have to believe all the crazy thoughts that pop into your head

The problem isn’t you; it’s your illness.

With proper treatment, you can escape The Impossible Task

__________________

I hope this Special Report has empowered you to understand the nature of The Impossible Task and leaves you with feeling compassion for yourself, as well as some useful tools for overcoming it. I know this is not always easy so if you are continuing to struggle with being stuck in The Impossible Task, please contact me or bring it up in your next session. I can help.

Other articles on this subject are: Finding Help That Understands

If you are interested in any subject on this site, please contact me.

For more information about the Impossible Task, go to

(c) 2020 Dr. Sarah A. Edwards

Sarah A. Edwards

what it is and how it helps in business

I talk about what decomposition is and how it allows you to set goals and more effectively achieve the desired results.

What is a goal?

The goal is the result of your activity. The result that you were striving for when you planned something. The goal allows you to accurately characterize the outcome of the planned work. This is a kind of guiding star that helps not to get bogged down in a routine and always get a return on the actions performed.

It is important to understand that goal setting and planning is a tool. You are not obliged to constantly use it in your activities and pass everything through the prism of setting goals.

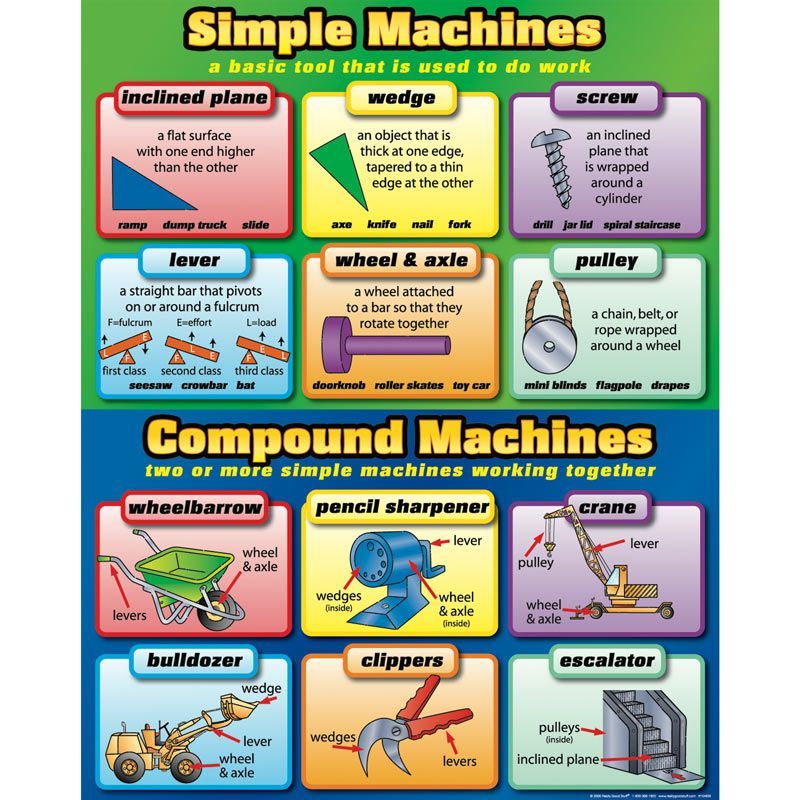

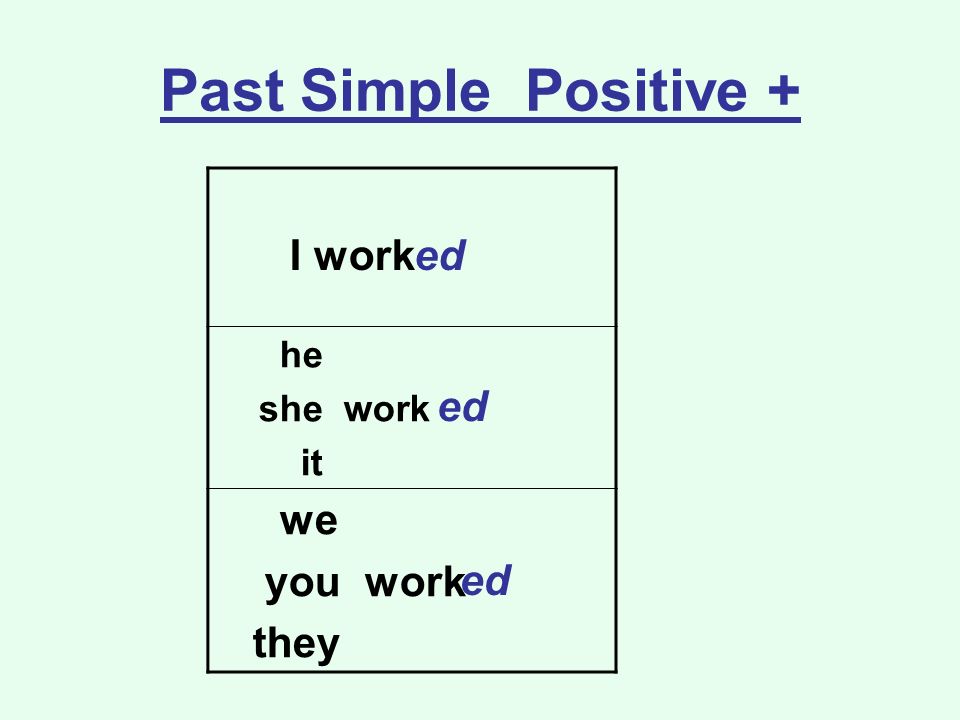

The concept of goal decomposition

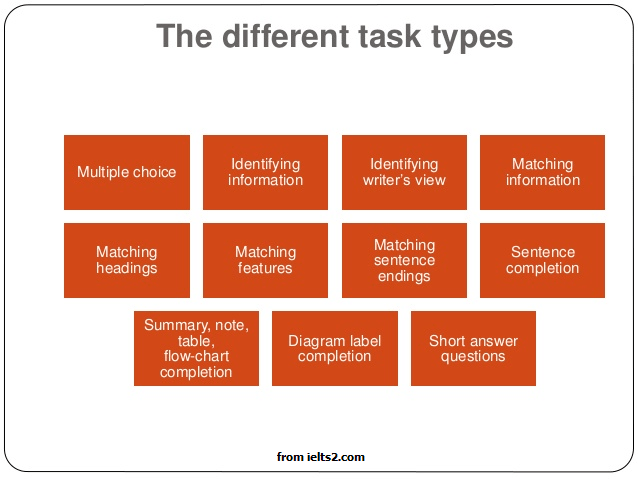

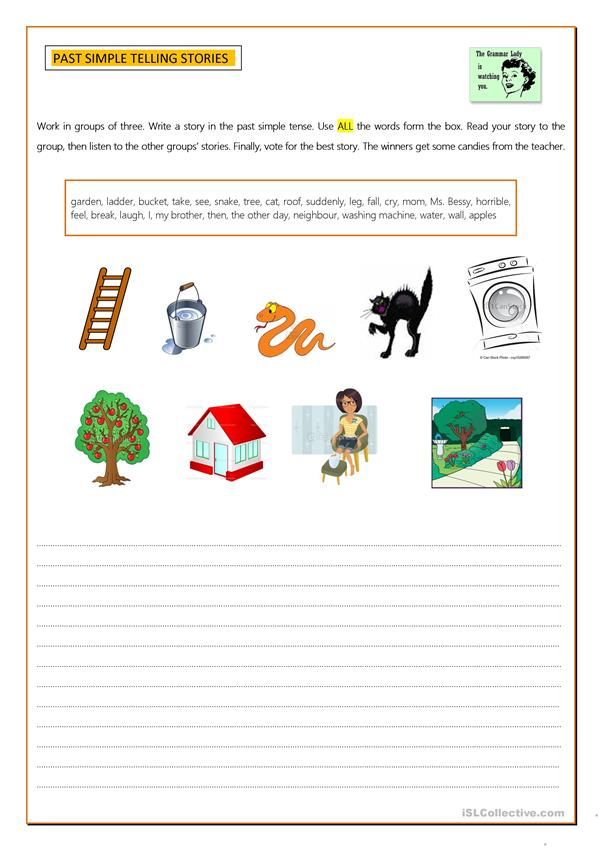

Decomposition is a tool to simplify the process of goal setting. The procedure itself involves breaking something large into small components. In the context of goal setting, decomposition is the division of a large task (the result that a person aspires to) into many small tasks.

A series of steps is being generated. Each step is a clear, easily perceived and implemented action. Such tasks are easy to solve both independently and by delegating to others, because they are not too complex, do not have inconsistencies, and their implementation is more likely to lead to the expected result.

Thus, decomposition turns a global, abstract and unattainable goal into a large-scale process that is much easier to approach, because it consists of simpler tasks by default that no longer seem overwhelming.

The community is now in Telegram

Subscribe and stay up to date with the latest IT news

Subscribe

The main advantages of goal decomposition thousand"? Or more precisely: "Change profession and increase income to 500 thousand in 2022." And you can divide the goal into smaller parts:

-

Sign up for programming courses (data-science, English, SMM, etc.

).

). -

Get a basic set of knowledge required in the relevant specialty.

-

Study every day for 2 hours.

-

Get an internship/find freelance clients.

This is a more specific plan of action, and it's easier to work with, because you don't have to jump into "Get rich" right away, but rather start by learning a new profession. But this is just an example.

Decomposition also works in business. When the global goals of the company are achieved through simpler tasks in the spirit of changing the assortment, rebranding or creating additional channels of communication with the audience.

It becomes easier to navigate

Decomposition creates a ladder between you and your goal, made up of various components designed to help you achieve the desired result. The task set earlier no longer seems unattainable. Not only do you know where to start, you know where you will be in the middle of the journey, you know how to evaluate your progress, and, most importantly, you understand how to adjust your path to get closer to your desired goal.

Decomposition puts you in a better position where you don't rush headlong to an abstract result, but know exactly where you are going and how.

It is easier to plan new tasks

The result of decomposition is also a kind of goal. With their subtasks, deadlines, necessary resources, etc. And when there are more of them, they are easier to plan.

You have more control over time. An abstract goal with deadlines that cannot be laid down in your head will never be realized. But more compact tasks with specific deadlines are much more malleable.

This approach gives a great advantage when working in a team. You can confidently say when a particular stage of work will be completed. Uncertainty will no longer interfere with overall progress.

It is easier to find resources to solve the set tasks

When you are faced with an excessively large-scale task, it is difficult to orient yourself and understand what resources are needed to implement it. Starting capital, skills, team.

Starting capital, skills, team.

Finding resources to achieve more compact goals is easier. There are specific cost estimates, there are specialists who are needed to solve a particular problem, there is an understanding of in which areas there are gaps and what should be studied in order to close these gaps.

This can be seen both in the case of conventional construction (what materials to buy, how many workers to hire, what tools will be needed and in what quantity), and in the example of single projects in the spirit of program development (what technologies to learn, how much money will be spent on hosting the service online, for advertising, etc.).

Basic principles of goal decomposition

There are several ways to implement goal decomposition, but they all follow a common set of rules. Following these rules allows you to achieve the greatest efficiency in dividing the goal into parts and subsequent work aimed at achieving them.

-

The smaller the target components, the better.

Even if there are hundreds of them, they will be understandable and implementable. It will be better than a dozen subtasks, but so large that their perception will be compromised.

Even if there are hundreds of them, they will be understandable and implementable. It will be better than a dozen subtasks, but so large that their perception will be compromised. -

It is necessary to avoid discrepancies and even the potential possibility of executing a subtask incorrectly. It's hard to do that, but you have to strive for it.

-

The task hierarchy matters. An ideal decomposition is when smaller tasks flow from larger ones.

-

Branches from a larger target must have similar characteristics. If the same large task grows from one task, then it is worth conducting it in parallel and also dividing it into more compact and digestible components.

-

It is necessary to make sure that the entire system has a single logic. So that when tasks are delegated, different partners and team members do not do the same work in parallel or conflicting tasks.

Decomposition of tasks should use specialized software.

For example, applications for creating mind maps or kanban boards in the spirit of Trello.

How to Decompose

When you start decomposing a goal, it's important to cut out all unnecessary details so you don't do unnecessary work. And for this, you need to gradually cut off the "garbage", leaving only extremely important goals that reliably lead to the achievement of the planned result.

First you need to decide on a global goal and designate it in human language without unnecessary abstractions. Then divide it into its main components, conduct an audit, divide the resulting tasks into even smaller components, and cut off everything superfluous during the re-audit. Those elements that got there during the division of subtasks, but in the end seem inappropriate.

Naturally, in the course of work it is important to interact with your team (if any) and build a hierarchy of goals together. This will noticeably speed up the process and allow you to look at the emerging work strategy from different angles.

Step-by-step decomposition

The simplest implementation option, which involves building a direct step-by-step plan. Typically, applications like SheetPlanner or OmniPlan are used for this. Something in the spirit of a direct list of tasks with predetermined due dates is formed.

It looks like a horizontal calendar, where each subtask takes a certain period of time. The tasks are related to each other step by step. For example, when building a house, it is impossible to finish first and then pour the foundation. This technique works well here.

But when developing a site, everything is different, because you can do the layout in parallel, configure the server, and plan the functional component.

Decomposition due to changing indicators

This is almost the same step-by-step strategy, only the measure is not time periods, but quantitative values.

This approach works only in a narrow range of activities, because the following conditions must be met:

-

In the course of reaching the goal, there must be some easily calculable value.

And the final value, the achievement of which leads to a global result.

And the final value, the achievement of which leads to a global result. -

Only you can influence the numbers. Influence from the outside is immediately swept aside, therefore, in this case, you lose control and cannot consistently move towards the final goal.

Therefore, this kind of decomposition will work if you count sets in the gym and plan to bench press 80 kilograms by the end of the month, but it does not work if you need to increase income or the number of followers on your Instagram account.

You can even use a notepad with a pen to record preliminary results. You don’t need any special software for this, but many people record indicators in spreadsheets like Google Sheets.

Mind maps

Brainstorming is a common method of generating ideas. It can also be used in a more measured manner and extended to work with large-scale projects.

Branching of subtasks allows you to focus on a simple but effective hierarchy when tasks depend on each other in terms of complexity. Not from terms or quantitative indicators, namely from dependence. If you do not make the components of the subtask, then it will not be executed.

Not from terms or quantitative indicators, namely from dependence. If you do not make the components of the subtask, then it will not be executed.

Therefore, using mind maps as a decomposition tool allows you to focus on solving small problems before moving on to larger ones.

This is similar to a step-by-step option, but there is often no time frame, and you can move towards the final result from different directions. There is no fixed path.

One step decomposition

This is a short term planning technique. Its main advantage is independence from accidents that may arise in the course of long-term work on some large-scale project.

One step decomposition works like this:

-

First you form the global target.

-

Then extract one stage from it.

-

Break this step into several additional steps.

-

You are doing it.

Do not create parallel plans, do not draw a massive mind map and do not delegate a huge number of tasks to your colleagues. So that circumstances do not interfere with your work, the focus remains on only one task. And a new one is not set until the previous one is resolved.

So that circumstances do not interfere with your work, the focus remains on only one task. And a new one is not set until the previous one is resolved.

Naturally, one-stage strategies will not help, if necessary, to plan the company's development tactics for years to come. All this works in the moment and significantly limits the ability to look into the future.

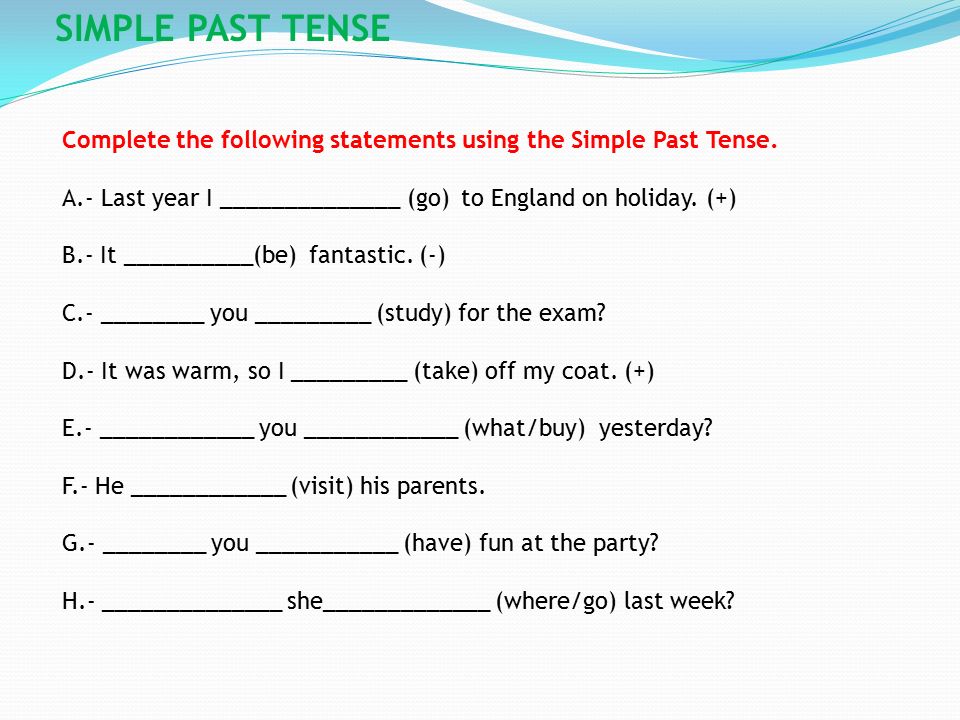

S.M.A.R.T Technology

This is not so much a decomposition technique as an addition to it that helps to set more specific goals.

The abbreviation S.M.A.R.T stands for:

-

S - Specific. This is what we talked about above. The task should be described in clear language and accurately so that there are no misunderstandings.

-

M - Measurable. According to the S.M.A.R.T methodology, a task must have a way to measure its degree of completion.

-

A - Attainable. You need to set yourself realistic goals that are achievable for you personally or your business.

-

R - Relevant (Relevance). It is important to understand how relevant the task is at the current time. Is it really necessary to do it at this moment.

-

T - Time-Bound. S.M.A.R.T technology requires you to specify the exact deadlines for completing the task when setting goals.

Many corporations and entrepreneurs use S.M.A.R.T in order not to set abstract goals for themselves and to clearly achieve their goals.

Evaluation of results based on the results of decomposition

It is easy to calculate personal indicators. Personal goals are usually not too big, and you can look in retrospect at where you were before and where you are now. If at the same time you also kept statistics, then you can always look at all the progress.

But formulas work in business and some other areas of activity. The formulas depend on the selected type of decomposition. For example, to calculate your income, you can take R for the result obtained by performing a particular action, and Q for the number of repetitions of a particular action. And then multiply one by the other.

And then multiply one by the other.

Instead of conclusion

Decomposition is simple in its essence. You can master this technique on the first try, but it has several implementation options. It is worth familiarizing yourself with them in order to choose the most effective method specifically for your tasks. This will help to put things in order in the head and in the company's development strategy, when it comes to business.

how to plan things so that you can do everything - T&P

Books on time management often contradict each other: somewhere they recommend immediately completing any small task, someone thinks that you need to start with the most difficult, and someone, on the contrary, it is necessary to consciously postpone things until later. Journalist Brian Christian and cognitive scientist Tom Griffiths are sure that in order to do everything, people need to use the algorithms that computers work with - with their help, you can long ago find the best option, taking into account all the given conditions.

Alpina Publisher published their book Algorithms for Life: Simple Ways to Make the Right Decisions, in which the authors explain how to apply complex mathematical formulas to solve everyday problems. T&P release snippet.

Alpina Publisher published their book Algorithms for Life: Simple Ways to Make the Right Decisions, in which the authors explain how to apply complex mathematical formulas to solve everyday problems. T&P release snippet. The science of pastime

Algorithms for Life: Simple Ways to Make Good Decisions

Although the problem of time management is as old as time itself, the science of planning was born in the machine shops of the industrial revolution. In 1874, Frederick Taylor, the son of a wealthy lawyer, abandoned his studies at Harvard to become an assistant engineer at a hydraulic plant in Philadelphia. Four years later, he graduated and began working at the Midvale Steel Works, first as a turner, then as a machine shop foreman, and eventually became chief engineer. During this time, he came to the conclusion that the time of the equipment (and people) was not used very effectively. This conclusion formed the basis of the discipline he developed, which he called "scientific management".

Taylor created a production and control department, the key element of which was an information board, which posted the schedule of work in the shop. The schedule indicated what task each of the machines was currently performing and what tasks were waiting in line. This practice would also form the basis of the work of Taylor's colleague Henry Gant. In the second decade of the 20th century, he would create his famous diagram that would go on to help realize some of the century's most ambitious construction projects, from the Hoover Dam to the US Interstate Highway System. A century later, Gantt charts still grace the office walls and laptop screens of project managers at companies like Amazon, IKEA, and SpaceX.

Taylor and Gant made planning the object of their research and gave it a visual and conceptual form. However, they did not resolve the fundamental question: what is the best planning system? The first hint that this question could in principle be answered did not come until several decades later, in a 1954 paper published by research mathematician Selmer Johnson of the RAND Corporation.

© urfinguss / iStock

Johnson explored the bookbinding scenario in which a book must first be printed on one machine and then bound using another. But the most common example of paired operation of two devices from our lives is the laundry. When you wash clothes, they first go through the washing machine and then go to the dryer. The amount of time each process will take depends directly on what you are downloading. If the clothes are heavily soiled, then the washing time will be longer, while the drying time will not differ from the usual. More items will take longer to dry, but the wash will take the same time as a smaller load. And here Johnson asked the question: “If you need to wash and dry several conditional sets of things in one go, how best to organize this?”

His answer was: you need to determine which process will take you the least time, that is, choose the set that will take the least time to wash or dry. If the set is washed quickly, start with it. If the minimum amount of time required for drying, take care of this kit last . Repeat the same steps for the rest of the sets of things, moving from the beginning and end of the schedule to the middle.

If the minimum amount of time required for drying, take care of this kit last . Repeat the same steps for the rest of the sets of things, moving from the beginning and end of the schedule to the middle.

Intuitively, the Johnson algorithm works because, regardless of the chosen load sequence, at the very beginning only the washing machine will work, while the dryer will be idle (and at the very end, when it remains only to dry the washed things, vice versa). If at the very beginning we wash things on short programs, and at the end we dry the least amount of things, then we will increase the period when both the washing machine and the dryer work at the same time. Thus, we will be able to minimize the time spent in the laundry room. Johnson's analysis formed the basis of the first optimal scheduling algorithm: start with a short wash and end with a half-empty dryer. […]

The essential planning problem for us really concerns only one device - ourselves.

Dealing with deadlines

When scheduling a single device, you immediately run into a problem. Johnson's research on bookbinding was based on the maximum reduction in the time required to complete the work of two machines. In the case of managing a single device, if we perform all the assigned tasks, any schedule will require the same amount of time and determining the order of tasks will be meaningless.

Johnson's research on bookbinding was based on the maximum reduction in the time required to complete the work of two machines. In the case of managing a single device, if we perform all the assigned tasks, any schedule will require the same amount of time and determining the order of tasks will be meaningless.

This is a fundamental and paradoxical fact, and worth repeating and fixing in our minds. If you have only one device and you plan to complete all the assigned tasks, then any order of tasks will take you the same amount of time.

Thus, we learn the first lesson in planning the operation of one device even before we start the discussion, namely: precisely define your goals . We won't be able to declare a winner among planning methods until we figure out how to keep score. This question also applies to computer science: before you have a plan, you must define a set of criteria. It turns out that the choice of criteria directly determines which planning approach will be the best.

The first scientific work on task scheduling for a single device followed immediately after Johnson's research and proposed a number of strong criteria. For each criterion, a simple optimal strategy was developed.

We are used to the fact that, for example, for each task there is a due date and an acceptable amount of delay. Thus, we can introduce the term "maximum delay in completing a set of tasks" - the largest disruption of the established deadline among these tasks (this is what your employer will take into account when evaluating your activities). For retail buyers or service customers, for example, the maximum task delay corresponds to the longest wait time for the customer.

If you would like to minimize this maximum delay time, you should start with the task that is due first and move towards the task that can be completed as soon as possible. The strategy known as "fast due date" is actually largely intuitive. (For example, in the service industry, where each customer's task deadline starts from the moment they walk in the door, this strategy involves serving customers in the order in which they appear. ) But some of the findings are surprising. For example, it doesn’t matter at all how much time it takes to complete each specific task: this does not affect the plan in any way, so, in fact, you don’t need to know this. All that is important is to know when the task must be completed.

) But some of the findings are surprising. For example, it doesn’t matter at all how much time it takes to complete each specific task: this does not affect the plan in any way, so, in fact, you don’t need to know this. All that is important is to know when the task must be completed.

You may already be using an early due date strategy to handle your workload, then you don't need to listen to programmers' advice when choosing a strategy. But, most likely, you are not aware that this is the optimal strategy. It would be more accurate to say that only one specific indicator is important for you - the reduction in the time of your maximum lateness. If you do not pursue such a goal, then another strategy may be more suitable for you.

© pixel107 / iStock

Let's take a refrigerator for example. […] Each product has a different shelf life, so eating them on a first-come-first-served basis seems like the smartest idea. However, this is not the end of the story. The fast expiration date algorithm, or spoilage date in our case, is optimal for reducing the time of maximum lateness, which means minimizing the degree of spoilage of the one most spoiled product that you have to eat. This is probably not the most appetizing criterion.

The fast expiration date algorithm, or spoilage date in our case, is optimal for reducing the time of maximum lateness, which means minimizing the degree of spoilage of the one most spoiled product that you have to eat. This is probably not the most appetizing criterion.

Perhaps instead we would like to minimize the amount of food that goes bad. And then we'd better resort to the help of Moore's algorithm. Accordingly, we begin the process of selecting products on the basis of the earliest expiration date, planning to consume the most perishable product first, one product at a time. But as soon as we realize that we won’t be able to eat the next product on time, we take a break, return to all those products that we have already planned, and throw away the largest unit (the one that will take us the most days to consume).

For example, we may have to give up melon, which can only be eaten in a few servings. Thus, we follow this pattern every time, laying out the products by their shelf life and sending the most voluminous planned product that we do not have time to eat to the trash can. At the moment when we can eat all the remaining products and prevent any of them from spoiling, we reach the goal.

At the moment when we can eat all the remaining products and prevent any of them from spoiling, we reach the goal.

Moore's algorithm minimizes the amount of food you would have to throw away. Of course, you can compost the food or just give it to a neighbor. But if we are talking about production or paperwork, when you cannot simply abandon a project, and it is the number of projects not completed on time (and not the degree of delay in their execution) that is of great importance to you, then Moore's algorithm will not tell you how deal with overdue tasks. Everything that you left out of the main part of the plan can be done at the very end in any order, since these questions are already were not resolved on time.

How to get things done

Sometimes meeting deadlines is not our biggest concern. We just want to redo all the cases: the more cases, the faster we want to deal with them. It turns out that it is very difficult to translate this seemingly elementary desire into the plane of planning criteria.

The first approach is to think abstractly. We noted earlier that when scheduling a single device, we cannot influence the total execution time of all tasks, but if, for example, each individual task is a waiting client, there is a way to minimize the time collective waiting for all customers.

Imagine that as of Monday morning you have to devote four working days to one project and one day to another. If you finished a large project on Thursday afternoon (four days passed) and then completed a small project on Friday afternoon (five days passed), then the total customer wait time was nine days. If you do the tasks in reverse order, you will finish a small project on Monday and a large project on Friday, with a waiting time of only six days. In any case, you will be busy full time, but you can save your clients three days of their time together. Scheduling theorists call this criterion the sum of execution times.

Maximizing the sum of execution times leads us to a very simple optimal algorithm, the least service time algorithm: first do what you can do the fastest.

Even if your job doesn't involve impatient customers waiting for their issue to be resolved, the least service time algorithm will help you handle your business. (I'm sure you're not surprised by this parallel with the advice in Getting Things Done to start immediately on any task that takes you less than two minutes to complete.) You can't change the time it takes you to complete the entire amount of work, but The least service time algorithm will make your life easier by reducing the number of unsolved problems in the shortest possible time. The sum of lead times criterion can be explained in another way: imagine that you are only focused on reducing your to-do list. If every unfinished business annoys you, then quick resolution of simple issues can ease your suffering a little.

Of course, not all pending cases are the same in nature. Putting out the fire in the kitchen, of course, should have been the first thing to do, postponing the extinguishing of the “fire” at work: sending an urgent letter to the client in this case will wait, even if the elimination of the fire in the kitchen takes you more time. In planning, the different importance of tasks is expressed by variable of weight . When you do things from your list, this weight can be figurative and expressed only in the weight of the mountain that will fall from your shoulders with the completion of a particular task.

In planning, the different importance of tasks is expressed by variable of weight . When you do things from your list, this weight can be figurative and expressed only in the weight of the mountain that will fall from your shoulders with the completion of a particular task.

Task time indicates how long you carry this burden, and the maximum reduction in the sum of times of the weight execution (this is the time to complete any task multiplied by its weight) will minimize the burden on your shoulders while you manage other things by the list.

For this purpose, the optimal strategy is a slightly improved version of the least service time algorithm. Let's divide the weight of each task by the time required to complete it, start solving the issue with the highest ratio of importance to unit of time (to develop our metaphor, we can call this indicator specific weight) and then move from question to question as the value of the indicator decreases . Since it can sometimes be difficult to determine the importance of each of your daily activities, this strategy suggests using a rough rule of thumb: prioritize the task that will not only take you twice as long as the rest, but will also be twice as important as the rest.

© Dmytro Lastovych / iStock

In the business world, weight can be estimated in terms of money: how much money you will get from completing a particular task. By dividing the reward by the time to complete, we get the hourly rate for each task. (If you're a freelancer, this can be especially effective for you: simply divide the cost of each of your projects by its size and work on projects in order of decreasing hourly rate.) Curiously, the weighting strategy also appears in animal foraging studies: where dollars and cents are turned into nuts and berries. Animals, trying to get the maximum energy from food, look for food based on the ratio of calories and time spent on searching and eating. […]

Selecting tasks

Let's return to where we started our discussion about scheduling the operation of one device. As the saying goes, “A man with one watch knows what time it is; a man with two clocks is never sure what time it is." Computer science can offer us optimal algorithms for any criteria that exist for the operation of one device, but only we can choose a criterion. In many cases, we ourselves decide what task we want to solve now.

In many cases, we ourselves decide what task we want to solve now.

This allows us to radically rethink the problem of procrastination, the classic pathology of time management. We used to think that this is an erroneous algorithm. But what if it's quite the opposite? What if this is the optimal solution of the incorrect problem ?

In one episode of The X-Files, the protagonist Mulder, bedridden (literally), was about to fall prey to a neurotic vampire. To save himself, he knocked over a bag of seeds on the floor. The vampire, powerless over his mental illness, began to bend down to pick them up, seed by seed. In the meantime, dawn broke, before Mulder was the monster's prey. Programmers would call this a ping attack or a network denial of service attack: if you force a system to perform an infinite number of trivial tasks, the most important things will be lost in the chaos.

We usually associate procrastination with laziness and so-called avoidance behavior, but symptoms of procrastination can just as easily appear in people (or computers, or even vampires) who sincerely and enthusiastically strive to get things done as quickly as possible.

© koosen / iStock

In a 2014 study by David Rosenbaum of the University of Pennsylvania, participants were asked to carry one or two heavy buckets to the opposite end of a corridor. One of the buckets was next to the study participant, the second was further down the corridor. To the surprise of the experimenters, people immediately grabbed the bucket next to them and dragged it along the corridor, while passing by the second bucket, which could have been dragged only part of the distance. As the researchers noted, “This seemingly irrational choice reflects a predisposition to procrastinate. We introduce this term to define the phenomenon when we are in a hurry to complete some intermediate task even at the cost of additional physical effort. Delaying a big task in favor of solving a lot of simple questions can similarly be seen as an approximation of an intermediate goal, which, in other words, means that procrastinators act (optimally!) in such a way as to reduce the number of unresolved tasks in their thoughts as quickly as possible. This does not mean that their strategy is ineffective in getting things done. They have a great strategy, but for the wrong criteria.

This does not mean that their strategy is ineffective in getting things done. They have a great strategy, but for the wrong criteria.

Working with a computer presents a certain danger when we need to consciously and clearly choose a planning criterion: the user interface can unobtrusively (or intrusively) force us to use its criteria. The modern smartphone user, in particular, is accustomed to seeing icons on application icons that signal the number of tasks that we have to complete in each of them. If the mailbox notifies us of a certain number of unread letters, then it turns out that all messages by default have the same importance. In that case, can we be blamed for choosing a weightless least service time model for this problem (deal with the simplest emails first and defer the hardest until last) in order to quickly reduce the number of unread emails?

Live by the criterion, die by the criterion. If all tasks are in fact of equal importance, that's exactly what we'll have to do. But, if we don't want to become hostage to the little things, we need to take action to move towards the bottom of the to-do list. And here it all starts with the realization that the problem of one device that we are solving is the one that we want to solve at the moment. (In the case of app icons, if we can't get them to reflect our real priorities, or if we can't resist the urge to optimally reduce this number of backlogs that we're being challenged with, then it might be best to just turn them off.)0003

But, if we don't want to become hostage to the little things, we need to take action to move towards the bottom of the to-do list. And here it all starts with the realization that the problem of one device that we are solving is the one that we want to solve at the moment. (In the case of app icons, if we can't get them to reflect our real priorities, or if we can't resist the urge to optimally reduce this number of backlogs that we're being challenged with, then it might be best to just turn them off.)0003

Focusing on not just solving issues, but solving weighty issues, doing the most important work at any given time, looks like a panacea for procrastination. But, as practice shows, even this is not enough. And a group of experts in the field of computer planning will be convinced of this under extremely dramatic circumstances: on the surface of Mars, in front of the whole world.

Prioritization and queuing

It was the summer of 1997 and humanity had much to celebrate. For example, for the first time an all-terrain vehicle explored the surface of Mars. $150 million Pathfinder hit 16,000 mph, crossed 309million miles of empty space and landed with the help of air shock absorbers on the red rocky surface of Mars.

For example, for the first time an all-terrain vehicle explored the surface of Mars. $150 million Pathfinder hit 16,000 mph, crossed 309million miles of empty space and landed with the help of air shock absorbers on the red rocky surface of Mars.

And then he stalled.

Engineers at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory were worried and confused. The Pathfinder surprisingly began to ignore the execution of its key task with the highest priority (data exchange via the information bus) and began to solve issues of medium importance. What happened? Did the robot not understand what it was doing?

Suddenly, the Pathfinder detected that the data bus had not been used for an unacceptably long time, and, unable to call for help, initiated a hard reset on its own, costing the mission nearly an entire day's work. A day or more later it happened again.

Working feverishly, the lab team was eventually able to reproduce and then diagnose this behavior. The root of the evil was the classic planning danger called "reprioritization" . What happens is that a low-priority task seizes a system resource to run (say, access to a database), but then the timer interrupts the task in the middle, pausing it, and activates the system manager. The dispatcher is ready to run a high priority task, but cannot because the database is busy. Thus, the dispatcher moves down the task queue list, running various unblocked tasks of medium importance, instead of starting the highest priority task (which is blocked) or the low priority task, which is blocking work (and which ended up at the very end of the queue list after medium priority tasks). In such a nightmare scenario, the system may ignore the highest priority task for a very long time*.

What happens is that a low-priority task seizes a system resource to run (say, access to a database), but then the timer interrupts the task in the middle, pausing it, and activates the system manager. The dispatcher is ready to run a high priority task, but cannot because the database is busy. Thus, the dispatcher moves down the task queue list, running various unblocked tasks of medium importance, instead of starting the highest priority task (which is blocked) or the low priority task, which is blocking work (and which ended up at the very end of the queue list after medium priority tasks). In such a nightmare scenario, the system may ignore the highest priority task for a very long time*.

Once the lab engineers figured out that the problem was a reprioritization, they wrote a code to solve the problem and sent it millions of miles away to the Pathfinder. The solution was inheritance priorities. This means that if a low-priority task blocks a resource of a high-priority task, then the low-priority task must immediately "inherit" the high priority of the task it blocks.

The solution was inheritance priorities. This means that if a low-priority task blocks a resource of a high-priority task, then the low-priority task must immediately "inherit" the high priority of the task it blocks.

Comedian Mitch Hedberg tells this story: “I was at the casino, relaxing, and suddenly a guy came up to me and said: “You have to change seats. You blocked the fire exit." You'd think I wasn't going to run if a fire started." The argument of the casino employee: this is a change of priorities. Hedberg's counterargument: inheritance of priorities. Hedberg, lounging in his chair in front of the fleeing mob, lingering, puts his low-priority task over the high-priority task of people intent on saving their lives. But everything will change if he inherits their priority (against the crowd advancing in a panic, her priority is inherited quite quickly). As Hedberg says, "If you're made of combustible materials and you have legs, you never block a fire escape."

© goir / iStock

The moral of this story is that even the love of problem solving is sometimes not enough to avoid fatal planning mistakes. And even the love of solving important problems, too. The readiness to solve the most important issue with the utmost scrupulousness with our usual short-sightedness can lead to what the whole world calls procrastination. As in the case of a stuck car: the more you want to get out, the more you skid. According to Goethe, "what means more should never be dominated by what means less." And although there is a certain wisdom in this, sometimes such a statement is not entirely fair. Often, what means the most to us cannot be done until the smallest thing is done. Therefore, the only way out is to treat unimportant things with the same importance as the ones they slow down.

And even the love of solving important problems, too. The readiness to solve the most important issue with the utmost scrupulousness with our usual short-sightedness can lead to what the whole world calls procrastination. As in the case of a stuck car: the more you want to get out, the more you skid. According to Goethe, "what means more should never be dominated by what means less." And although there is a certain wisdom in this, sometimes such a statement is not entirely fair. Often, what means the most to us cannot be done until the smallest thing is done. Therefore, the only way out is to treat unimportant things with the same importance as the ones they slow down.

When one task cannot be started without first completing another, planning theorists call this queuing. To conduct operational research, expert Laura Albert Maclay, relying on this principle, significantly changed some aspects of housekeeping in her family.

If you understand how these things work, it can be very helpful. Of course, life with three kids is daily planning... We don't leave the house until the kids have breakfast, and the kids can't start breakfast if I forget to give them spoons. Sometimes we can forget elementary things, which then slow everything down. From the point of view of planning algorithms, realizing this fact and trying to keep it in mind is already a great help. This is how I do things day after day.

Of course, life with three kids is daily planning... We don't leave the house until the kids have breakfast, and the kids can't start breakfast if I forget to give them spoons. Sometimes we can forget elementary things, which then slow everything down. From the point of view of planning algorithms, realizing this fact and trying to keep it in mind is already a great help. This is how I do things day after day.

In 1978, researcher Jan Karel Lenstra was able to use the same principle to help his friend Gene move to a new home in Berkeley. "Jin was constantly putting off some business, without finishing which we could not proceed to urgent matters." As Lenstra recalls, they had to return the truck, but they needed it to return some equipment, and they needed the equipment to fix something in the apartment. This repair could wait (that's why everything was postponed), but the truck had to be returned urgently. According to Lenstra, he explained to a friend that the task that came before the most urgent one was even more urgent. Since Lenstra is known as a key figure in planning theory and was more than entitled to give such advice, he could not resist a delicate irony. This situation has become a case demonstrating the change of priorities due to queue management. And perhaps the most prominent expert in the field of queue management is considered to be just a friend of the narrator - the same Gene, or Eugene Lawler.