Sleep and dreaming

Dreams: Why We Dream & How They Affect Sleep

Dreams are one of the most fascinating and mystifying aspects of sleep. Since Sigmund Freud helped draw attention to the potential importance of dreams in the late 19th century, considerable research has worked to unravel both the neuroscience and psychology of dreams.

Despite this advancing scientific knowledge, there is much that remains unknown about both sleep and dreams. Even the most fundamental question — why do we dream at all? — is still subject to significant debate.

While everyone dreams, the content of those dreams and their effect on sleep can vary dramatically from person to person. Even though there’s no simple explanation for the meaning and purpose of dreams, it’s helpful to understand the basics of dreams, the potential impact of nightmares, and steps that you can take to sleep better with sweet dreams.

What Are Dreams?

Dreams are images, thoughts, or feelings that occur during sleep. Visual imagery is the most common, but dreams can involve all of the senses. Some people dream in color while others dream in black and white, and people who are blind tend to have more dream components related to sound, taste, and smell.

Studies have revealed diverse types of dream content, but some typical characteristics of dreaming include:

- It has a first-person perspective.

- It is involuntary.

- The content may be illogical or even incoherent.

- The content includes other people who interact with the dreamer and one another.

- It provokes strong emotions.

- Elements of waking life are incorporated into content.

Although these features are not universal, they are found at least to some extent in most normal dreams.

Having trouble sleeping?

Call the Help Me Sleep Hotline at 1-833-I-CANT-SLEEP for a set of tips, meditations, and bedtime stories to help you get a good night’s rest.

Why Do We Dream?

Debate continues among sleep experts about why we dream. Different theories about the purpose of dreaming include:

- Building memory: Dreaming has been associated with consolidation of memory, which suggests that dreaming may serve an important cognitive function of strengthening memory and informational recall.

- Processing emotion: The ability to engage with and rehearse feelings in different imagined contexts may be part of the brain’s method for managing emotions.

- Mental housekeeping: Periods of dreaming could be the brain’s way of “straightening up,” clearing away partial, erroneous, or unnecessary information.

- Instant replay: Dream content may be a form of distorted instant replay in which recent events are reviewed and analyzed.

- Incidental brain activity: This view holds that dreaming is just a by-product of sleep that has no essential purpose or meaning.

Experts in the fields of neuroscience and psychology continue to conduct experiments to discover what is happening in the brain during sleep, but even with ongoing research, it may be impossible to conclusively prove any theory for why we dream.

When Do We Dream?

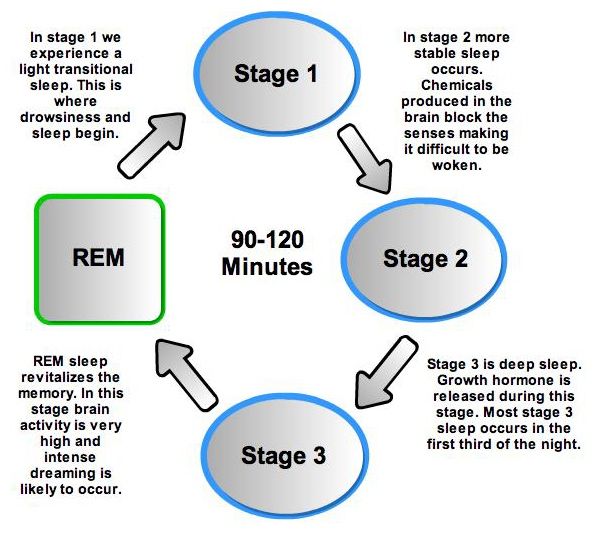

On average, most people dream for around two hours per night. Dreaming can happen during any stage of sleep, but dreams are the most prolific and intense during the rapid eye movement (REM) stage.

During the REM sleep stage, brain activity ramps up considerably compared to the non-REM stages, which helps explain the distinct types of dreaming during these stages. Dreams during REM sleep are typically more vivid, fantastical, and/or bizarre even though they may involve elements of waking life. By contrast, non-REM dreams tend to involve more coherent content that involves thoughts or memories grounded to a specific time and place.

REM sleep is not distributed evenly through the night. The majority of REM sleep happens during the second half of a normal sleep period, which means that dreaming tends to be concentrated in the hours before waking up.

Having trouble sleeping?

Call the Help Me Sleep Hotline at 1-833-I-CANT-SLEEP for a set of tips, meditations, and bedtime stories to help you get a good night’s rest.

Do Dreams Have Meaning?

How to interpret dreams, and whether they have meaning at all, are matters of considerable controversy. While some psychologists have argued that dreams provide insight into a person’s psyche or everyday life, others find their content to be too inconsistent or bewildering to reliably deliver meaning.

While some psychologists have argued that dreams provide insight into a person’s psyche or everyday life, others find their content to be too inconsistent or bewildering to reliably deliver meaning.

Virtually all experts acknowledge that dreams can involve content that ties back to waking experiences although the content may be changed or misrepresented. For example, in describing dreams, people often reference people who they recognize clearly even if their appearance is distorted in the dream.

The meaning of real-life details appearing in dreams, though, is far from settled. The “continuity hypothesis” in dream research holds that dreams and waking life are intertwined with one another and thus involve overlapping themes and content. The “discontinuity hypothesis,” on the other hand, sees thinking during dreams and wakefulness as structurally distinct.

While analysis of dreams may be a component of personal or psychological self-reflection, it’s hard to state, based on the existing evidence, that there is a definitive method for interpreting and understanding the meaning of dreams in waking, everyday life.

The Matt Walker Podcast

SleepFoundation.org's Scientific Advisor

Dreams

Listen on BuzzsproutWhat Are Types of Dreams?

Dreams can take on many different forms. Lucid dreams occur when a person is in a dream while being actively aware that they are dreaming. Vivid dreams involve especially realistic or clear dream content. Bad dreams are composed of bothersome or distressing content. Recurring dreams involve the same imagery repeating in multiple dreams over time.

Even within normal dreams, there are certain types of content that are especially identifiable. Among the most recognizable and common themes in dreams are things like flying, falling, being chased, or being unable to find a bathroom.

What Are Nightmares?

In sleep medicine, a nightmare is a bad dream that causes a person to wake up from sleep. This definition is distinct from common usage that may refer to any threatening, scary, or bothersome dream as a nightmare. While bad dreams are normal and usually benign, frequent nightmares may interfere with a person’s sleep and cause impaired thinking and mood during the daytime.

While bad dreams are normal and usually benign, frequent nightmares may interfere with a person’s sleep and cause impaired thinking and mood during the daytime.

Do Dreams Affect Sleep?

In most cases, dreams don’t affect sleep. Dreaming is part of healthy sleep and is generally considered to be completely normal and without any negative effects on sleep.

Nightmares are the exception. Because nightmares involve awakenings, they can become problematic if they occur frequently. Distressing dreams may cause a person to avoid sleep, leading to insufficient sleep. When they do sleep, the prior sleep deprivation can induce a REM sleep rebound that actually worsens nightmares. This negative cycle can cause some people with frequent nightmares to experience insomnia as a chronic sleep problem.

For this reason, people who have nightmares more than once a week, have fragmented sleep, or have daytime sleepiness or changes to their thinking or mood should talk with a doctor . A doctor can review these symptoms to identify the potential causes and treatments of their sleeping problem.

A doctor can review these symptoms to identify the potential causes and treatments of their sleeping problem.

How Can You Remember Dreams?

For people who want to document or interpret dreams, remembering them is a key first step. The ability to recall dreams can be different for every person and may vary based on age. While there’s no guaranteed way to improve dream recall, experts recommend certain tips:

- Think about your dreams as soon as you wake up. Dreams can be forgotten in the blink of an eye, so you want to make remembering them the first thing you do when you wake up. Before sitting up or even saying good morning to your bed partner, close your eyes and try to replay your dreams in your mind.

- Have a journal or app on-hand to keep track of your dream content. It’s important to have a method to quickly record dream details before you can forget them, including if you wake up from a dream in the night. For most people, a pen and paper on their nightstand works well, but there are also smartphone apps that help you create an organized and searchable dream journal.

- Try to wake up peacefully in the morning. An abrupt awakening, such as from an alarm clock, may cause you to quickly snap awake and out of a dream, making it harder to remember the dream’s details.

Remind yourself that dream recall is a priority. In the lead-up to bedtime, tell yourself that you will remember your dreams, and repeat this mantra before going to sleep. While this alone can’t ensure that you will recall your dreams, it can encourage you to remember to take the time to reflect on dreams before starting your day.

How Can You Stop Nightmares?

People with frequent nightmares that disturb sleep should talk with a doctor who can determine if they have nightmare disorder or any other condition affecting their sleep quality. Treatment for nightmare disorder often includes talk therapy that attempts to counteract negative thinking, stress, and anxiety that can worsen nightmares.

Many types of talk therapy attempt to reduce worries or fears, including those that can arise in nightmares. This type of exposure or desensitization therapy helps many patients reframe their emotional reaction to negative imagery since trying to simply suppress negative thoughts may exacerbate nightmares.

This type of exposure or desensitization therapy helps many patients reframe their emotional reaction to negative imagery since trying to simply suppress negative thoughts may exacerbate nightmares.

Another step in trying to reduce nightmares is to improve sleep hygiene, which includes both sleep-related habits and the bedroom environment. Healthy sleep hygiene can make your nightly sleep more predictable and may help you sleep soundly through the night even if you have bad dreams. Examples of healthy sleep tips include:

- Follow a stable sleep schedule: Keep a steady schedule every day, including on weekends or other days when you don’t have to wake up at a certain time.

- Choose pre-bed content carefully: Avoid scary, distressing, or stimulating content in the hours before bed since it may provoke negative thoughts during sleep.

- Wind down each night: Exercising during the day can help you sleep better at night. In the evening, try to allow your mind and body to calmly relax before bed such as with light stretching, deep breathing, or other relaxation techniques.

- Limit alcohol and caffeine: Drinking alcohol can cause more concentrated REM sleep later in the night, heightening the risk of nightmares. Caffeine is a stimulant that can throw off your sleep schedule and keep your brain wired when you want to doze off.

- Block out bedroom distractions: Try to foster a sleeping environment that is dark, quiet, smells nice, and has a comfortable temperature. A supportive mattress and pillow can make your bed more inviting and cozy. All of these factors make it easier to feel calm and to prevent unwanted awakenings that can trigger irregular sleep patterns.

- Was this article helpful?

- YesNo

About Our Editorial Team

Eric Suni

Staff Writer

Eric Suni has over a decade of experience as a science writer and was previously an information specialist for the National Cancer Institute.

Alex Dimitriu

Psychiatrist

MD

Dr. Dimitriu is the founder of Menlo Park Psychiatry and Sleep Medicine. He is board-certified in psychiatry as well as sleep medicine.

He is board-certified in psychiatry as well as sleep medicine.

References

+17 Sources

-

1.

Ruby P. M. (2011). Experimental research on dreaming: state of the art and neuropsychoanalytic perspectives. Frontiers in psychology, 2, 286. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00286

-

2.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS). (2019, August 13). Brain Basics: Understanding Sleep. Retrieved October 14, 2020, from https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/patient-caregiver-education/understanding-sleep

-

3.

Meaidi, A., Jennum, P., Ptito, M., & Kupers, R. (2014). The sensory construction of dreams and nightmare frequency in congenitally blind and late blind individuals. Sleep medicine, 15(5), 586–595. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sleep.2013.12.008

-

4.

Scarpelli, S., Bartolacci, C., D'Atri, A., Gorgoni, M., & De Gennaro, L. (2019).

Mental Sleep Activity and Disturbing Dreams in the Lifespan. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(19), 3658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph26193658

Mental Sleep Activity and Disturbing Dreams in the Lifespan. International journal of environmental research and public health, 16(19), 3658. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph26193658 -

5.

Division of Sleep Medicine at Harvard Medical School. (2007, December 18). The Characteristics of Sleep. Retrieved October 14, 2020, from http://healthysleep.med.harvard.edu/healthy/science/what/characteristics

-

6.

Purves, D., Augustine, G. J., & Fitzpatrick, D. et al. (Eds.). (2001). The Possible Functions of REM Sleep and Dreaming. In Neuroscience (2nd Edition). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11121/

-

7.

Pagel J. F. (2000). Nightmares and disorders of dreaming. American family physician, 61(7), 2037–2044. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/10779247/

-

8.

Payne, J. D., & Nadel, L. (2004). Sleep, dreams, and memory consolidation: the role of the stress hormone cortisol. Learning & memory (Cold Spring Harbor, N.

Y.), 11(6), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.77104

Y.), 11(6), 671–678. https://doi.org/10.1101/lm.77104 -

9.

Kahn, D., Stickgold, R., Pace-Schott, E. F., & Hobson, J. A. (2000). Dreaming and waking consciousness: a character recognition study. Journal of sleep research, 9(4), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2869.2000.00213.x

-

10.

Schredl, M., Ciric, P., Götz, S., & Wittmann, L. (2004). Typical dreams: stability and gender differences. The Journal of psychology, 138(6), 485–494. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.138.6.485-494

-

11.

Paul, F., Schredl, M., & Alpers, G. W. (2015). Nightmares affect the experience of sleep quality but not sleep architecture: an ambulatory polysomnographic study. Borderline personality disorder and emotion dysregulation, 2, 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-014-0023-4

-

12.

Aurora, R. N., Zak, R. S., Auerbach, S. H., Casey, K. R., Chowdhuri, S., Karippot, A., Maganti, R. K., Ramar, K., Kristo, D. A., Bista, S.

R., Lamm, C. I., Morgenthaler, T. I., Standards of Practice Committee, & American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2010). Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 6(4), 389–401. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2919672/

R., Lamm, C. I., Morgenthaler, T. I., Standards of Practice Committee, & American Academy of Sleep Medicine (2010). Best practice guide for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults. Journal of clinical sleep medicine : JCSM : official publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 6(4), 389–401. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2919672/ -

13.

A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. (2018, March 26). Nightmares. Retrieved October 14, 2020, from https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003209.htm

-

14.

Mangiaruga, A., Scarpelli, S., Bartolacci, C., & De Gennaro, L. (2018). Spotlight on dream recall: the ages of dreams. Nature and science of sleep, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2147/NSS.S135762

-

15.

Barrett, D., & Luna, K. (2018, December). Speaking of psychology: The science of dreaming. American Psychological Association. Retrieved September 16, 2021, from https://www.apa.org/research/action/speaking-of-psychology/science-of-dreaming

-

16.

Kröner-Borowik, T., Gosch, S., Hansen, K., Borowik, B., Schredl, M., & Steil, R. (2013). The effects of suppressing intrusive thoughts on dream content, dream distress and psychological parameters. Journal of sleep research, 22(5), 600–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12058

-

17.

National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Population Health. (2016, July 15). Tips for Better Sleep. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved October 28, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html

See More

The Effects of Sleep Quality on Dream and Waking Emotions

1. Walker M.P., van der Helm E. Overnight Therapy? The Role of Sleep in Emotional Brain Processing. Psychol. Bull. 2009;135:731–748. doi: 10.1037/a0016570. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Tempesta D., Socci V., De Gennaro L., Ferrara M. Sleep and emotional processing. Sleep Med. Rev. 2018;40:183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2017.12.005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Levin R., Nielsen T. Nightmares, Bad Dreams, and Emotion Dysregulation. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2009;18:84–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01614.x. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Maquet P., Peters J.M., Aerts J., Delfiore G., Degueldre C., Luxen A., Franck G. Functional neuroanatomy of human rapid-eye-movement sleep and dreaming. Nature. 1996;383:163–166. doi: 10.1038/383163a0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Schwartz S., Maquet P. Sleep imaging and the neuropsychological assessment of dreams. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2002;6:23–30. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01818-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Nofzinger E.A., Mintun M.A., Wiseman M., Kupfer D.J., Moore R.Y. Forebrain activation in REM sleep: An FDG PET study. Brain Res. 1997;770:192–201. doi: 10.1016/S0006-8993(97)00807-X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Pace-Schott E.F., Hobson J.A. The neurobiology of sleep: Genetics, cellular physiology and subcortical networks. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:591–605. doi: 10.1038/nrn895. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2002;3:591–605. doi: 10.1038/nrn895. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Goldstein A.N., Walker M.P. The Role of Sleep in Emotional Brain Function. Annu. Rev. Clin. Psychol. 2014;10:679–708. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153716. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Schredl M., Wittmann L. Dreaming: A psychological view. Schweiz. Arch. Neurol. Psychiatr. 2005;156:484–492. doi: 10.4414/sanp.2005.01656. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Scarpelli S., Bartolacci C., D’Atri A., Gorgoni M., De Gennaro L. The Functional Role of Dreaming in Emotional Processes. Front. Psychol. 2019;10:459. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00459. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Cartwright R., Luten A., Young M., Mercer P., Bears M. Role of REM sleep and dream affect in overnight mood regulation: A study of normal volunteers. Psychiatry Res. 1998;81:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(98)00089-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Cartwright R., Agargun M.Y., Kirkby J., Friedman J.K. Relation of dreams to waking concerns. Psychiatry Res. 2006;141:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.05.013. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Cartwright R., Agargun M.Y., Kirkby J., Friedman J.K. Relation of dreams to waking concerns. Psychiatry Res. 2006;141:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2005.05.013. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Revonsuo A. The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of the function of dreaming. Behav. Brain Sci. 2000;23:877–901. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X00004015. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Revonsuo A., Tuominen J., Valli K. Dreaming as a Simulation of Social Reality. Open MIND. 2015:1–28. doi: 10.15502/9783958570375. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Conte F., Cellini N., De Rosa O., Caputo A., Malloggi S., Coppola A., Albinni B., Cerasuolo M., Giganti F., Marcone R., et al. Relationships between Dream and Previous Wake Emotions Assessed through the Italian Modified Differential Emotions Scale. Brain Sci. 2020;10:690. doi: 10.3390/brainsci10100690. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Fredrickson B.L., Tugade M.M., Waugh C. E., Larkin G.R. What Good Are Positive Emotions in Crises? A Prospective Study of Resilience and Emotions Following the Terrorist attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003;84:365–376. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

E., Larkin G.R. What Good Are Positive Emotions in Crises? A Prospective Study of Resilience and Emotions Following the Terrorist attacks on the United States on 11 September 2001. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2003;84:365–376. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Fredrickson B.L. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Volume 47. Academic Press Inc.; San Diego, CA, USA: 2013. Positive Emotions Broaden and Build; pp. 1–53. [Google Scholar]

18. Minkel J.D., Banks S., Htaik O., Moreta M.C., Jones C.W., McGlinchey E.L., Simpson N.S., Dinges D.F. Sleep deprivation and stressors: Evidence for elevated negative affect in response to mild stressors when sleep deprived. Emotion. 2012;12:1015–1020. doi: 10.1037/a0026871. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Anderson C., Platten C.R. Sleep deprivation lowers inhibition and enhances impulsivity to negative stimuli. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;217:463–466. doi: 10. 1016/j.bbr.2010.09.020. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1016/j.bbr.2010.09.020. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Tempesta D., Couyoumdjian A., Curcio G., Moroni F., Marzano C., De Gennaro L., Ferrara M. Lack of sleep affects the evaluation of emotional stimuli. Brain Res. Bull. 2010;82:104–108. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.01.014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Tempesta D., De Gennaro L., Natale V., Ferrara M. Emotional memory processing is influenced by sleep quality. Sleep Med. 2015;16:862–870. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.01.024. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Van Der Helm E., Gujar N., Walker M.P. Sleep deprivation impairs the accurate recognition of human emotions. Sleep. 2010;33:335–342. doi: 10.1093/sleep/33.3.335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Minkel J., Htaik O., Banks S., Dinges D. Emotional expressiveness in sleep-deprived healthy adults. Behav. Sleep Med. 2011;9:5–14. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2011.533987. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Yoo S.S., Gujar N., Hu P., Jolesz F.A., Walker M.P. The human emotional brain without sleep—A prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R877–R878. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Yoo S.S., Gujar N., Hu P., Jolesz F.A., Walker M.P. The human emotional brain without sleep—A prefrontal amygdala disconnect. Curr. Biol. 2007;17:R877–R878. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.08.007. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Motomura Y., Kitamura S., Oba K., Terasawa Y., Enomoto M., Katayose Y., Hida A., Moriguchi Y., Higuchi S., Mishima K. Sleep Debt Elicits Negative Emotional Reaction through Diminished Amygdala-Anterior Cingulate Functional Connectivity. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e56578. doi: 10.1371/annotation/5970fff3-0a1c-4056-9396-408d76165c4d. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Franzen P.L., Buysse D.J. Sleep disturbances and depression: Risk relationships for subsequent depression and therapeutic implications. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2008;10:473–481. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Sauvet F., Leftheriotis G., Gomez-Merino D., Langrume C., Drogou C., Van Beers P., Bourrilhon C., Florence G., Chennaoui M. Effect of acute sleep deprivation on vascular function in healthy subjects. J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;108:68–75. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00851.2009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Appl. Physiol. 2010;108:68–75. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00851.2009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Dinges D.F., Pack F., Williams K., Gillen K.A., Powell J.W., Ott G.E., Aptowicz C., Pack A.I. Cumulative sleepiness, mood disturbance, and psychomotor vigilance performance decrements during a week of sleep restricted to 4-5 h per night. Sleep. 1997;20:267–277. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.4.267. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Baum K.T., Desai A., Field J., Miller L.E., Rausch J., Beebe D.W. Sleep restriction worsens mood and emotion regulation in adolescents. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry Allied Discip. 2014;55:180–190. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Norlander T., Johansson Å., Bood S.Å. The affective personality: Its relation to quality of sleep, well-being and stress. Soc. Behav. Pers. 2005;33:709–722. doi: 10.2224/sbp.2005.33.7.709. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Mccrae C.S., Mcnamara J.P.H. , Rowe M.A., Dzierzewski J.M., Dirk J., Marsiske M., Craggs J.G. Sleep and affect in older adults: Using multilevel modeling to examine daily associations. J. Sleep Res. 2008;17:42–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00621.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Rowe M.A., Dzierzewski J.M., Dirk J., Marsiske M., Craggs J.G. Sleep and affect in older adults: Using multilevel modeling to examine daily associations. J. Sleep Res. 2008;17:42–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00621.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Bower B., Bylsma L.M., Morris B.H., Rottenberg J. Poor reported sleep quality predicts low positive affect in daily life among healthy and mood-disordered persons: Sleep quality and positive affect. J. Sleep Res. 2010;19:323–332. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2009.00816.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Mauss I.B., Troy A.S., LeBourgeois M.K. Poorer sleep quality is associated with lower emotion-regulation ability in a laboratory paradigm. Cogn. Emot. 2013;27:567–576. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2012.727783. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Prather A.A., Bogdan R., Hariri A.R. Impact of sleep quality on amygdala reactivity, negative affect, and perceived stress. Psychosom. Med. 2013;75:350–358. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828ef15b. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Med. 2013;75:350–358. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31828ef15b. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Buysse D.J., Reynolds C.F., Monk T.H., Berman S.R., Kupfer D.J. The Pittsburgh sleep quality index: A new instrument for psychiatric practice and research. Psychiatry Res. 1989;28:193–213. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(89)90047-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Schredl M., Schäfer G., Weber B., Heuser I. Dreaming and insomnia: Dream recall and dream content of patients with insomnia. J. Sleep Res. 1998;7:191–198. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1998.00113.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Pérusse A.D., De Koninck J., Pedneault-Drolet M., Ellis J.G., Bastien C.H. REM dream activity of insomnia sufferers: A systematic comparison with good sleepers. Sleep Med. 2016;20:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2015.08.007. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Feige B., Nanovska S., Baglioni C., Bier B., Cabrera L., Diemers S., Quellmalz M., Siegel M., Xeni I. , Szentkiralyi A., et al. Insomnia-Perchance a dream? Results from a NREM/REM sleep awakening study in good sleepers and patients with insomnia. Sleep. 2018;41 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy032. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Szentkiralyi A., et al. Insomnia-Perchance a dream? Results from a NREM/REM sleep awakening study in good sleepers and patients with insomnia. Sleep. 2018;41 doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy032. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Fosse R., Stickgold R., Hobson J.A. Emotional experience during rapid-eye-movement sleep in narcolepsy. Sleep. 2002;25:724–732. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.7.724. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Levin R. Sleep and dreaming characteristics of frequent nightmare subjects in a university population. Dreaming. 1994;4:127–137. doi: 10.1037/h0094407. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Krakow B., Tandberg D., Barey M., Scriggins L. Nightmares and sleep disturbance in sexually assaulted women. Dreaming. 1995;5:199–206. doi: 10.1037/h0094435. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Ohayon M.M., Morselli P.L., Guilleminault C. Prevalence of nightmares and their relationship to psychopathology and daytime functioning in insomnia subjects. Sleep. 1997;20:340–348. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.5.340. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.5.340. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Stepansky R., Holzinger B., Schmeiser-Rieder A., Saletu B., Kunze M., Zeitlhofer J. Austrian dream behavior: Results of a representative population survey. Dreaming. 1998;8:23–30. doi: 10.1023/B:DREM.0000005912.77493.d6. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Blagrove M., Henley-Einion J., Barnett A., Edwards D., Heidi Seage C. A replication of the 5-7day dream-lag effect with comparison of dreams to future events as control for baseline matching. Conscious. Cogn. 2011;20:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.07.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Eichenlaub J.B., van Rijn E., Phelan M., Ryder L., Gaskell M.G., Lewis P.A., Walker M., Blagrove M. The nature of delayed dream incorporation (‘dream-lag effect’): Personally significant events persist, but not major daily activities or concerns. J. Sleep Res. 2019;28:e12697. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12697. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Schredl M., Berres S., Klingauf A., Schellhaas S., Göritz A.S. The Mannheim dream questionnaire (MADRE): Retest reliability, age and gender effects. Int. J. Dream Res. 2014;7:141–147. doi: 10.11588/ijodr.2014.2.16675. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Schredl M., Berres S., Klingauf A., Schellhaas S., Göritz A.S. The Mannheim dream questionnaire (MADRE): Retest reliability, age and gender effects. Int. J. Dream Res. 2014;7:141–147. doi: 10.11588/ijodr.2014.2.16675. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Curcio G., Tempesta D., Scarlata S., Marzano C., Moroni F., Rossini P.M., Ferrara M., De Gennaro L. Validity of the Italian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) Neurol. Sci. 2013;34:511–519. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1085-y. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Fredrickson B.L., Cohn M.A., Coffey K.A., Pek J., Finkel S.M. Open Hearts Build Lives: Positive Emotions, Induced Through Loving-Kindness Meditation, Build Consequential Personal Resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2008;95:1045–1062. doi: 10.1037/a0013262. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Cohn M.A., Fredrickson B.L., Brown S.L., Mikels J.A., Conway A.M. Happiness Unpacked: Positive Emotions Increase Life Satisfaction by Building Resilience. Emotion. 2009;9:361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0015952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Emotion. 2009;9:361–368. doi: 10.1037/a0015952. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Galanakis M., Stalikas A., Pezirkianidis C., Karakasidou I. Reliability and Validity of the Modified Differential Emotions Scale (mDES) in a Greek Sample. Psychology. 2016;7:101–113. doi: 10.4236/psych.2016.71012. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Rovira D.P., Bobowik M., Levillain P.C., Bosco S. Evaluación de la afectividad durante diferentes episodios emocionales. In: Beristain C.M., Castro J.L.G., Basabe N., De Rivera J., editors. Superando la Violencia Colectiva y Construyendo Cultura de Paz. Fundamentos; Madrid, Spain: 2011. [Google Scholar]

52. Muzaffar N. Najam-us-Sahar Role of Family System, Positive Emotions and Resilience in Social Adjustment among Pakistani Adolescents. J. Educ. Health Community Psychol. 2017;6:46–58. [Google Scholar]

53. Sikka P., Pesonen H., Revonsuo A. Peace of mind and anxiety in the waking state are related to the affective content of dreams. Sci. Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30721-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Sci. Rep. 2018;8 doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-30721-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Montebarocci O., Giovagnoli S. Alexithymia, Depression, Trait-anxiety and Their Relation to Self-reported Retrospective Dream Experience. Am. J. Appl. Psychol. 2019;8:132. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20190806.13. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Mah C.D., Kezirian E.J., Marcello B.M., Dement W.C. Poor sleep quality and insufficient sleep of a collegiate student-athlete population. Sleep Health. 2018;4:251–257. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.02.005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Lund H.G., Reider B.D., Whiting A.B., Prichard J.R. Sleep Patterns and Predictors of Disturbed Sleep in a Large Population of College Students. J. Adolesc. Health. 2010;46:124–132. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.06.016. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Becker S.P., Jarrett M.A., Luebbe A.M., Garner A.A., Burns G.L., Kofler M.J. Sleep in a large, multi-university sample of college students: Sleep problem prevalence, sex differences, and mental health correlates. Sleep Health. 2018;4:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.01.001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Sleep Health. 2018;4:174–181. doi: 10.1016/j.sleh.2018.01.001. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Soffer-Dudek N. Arousal in nocturnal consciousness: How dream- and sleep-experiences may inform us of poor sleep quality, stress, and psychopathology. Front. Psychol. 2017;8:733. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00733. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Gott J., Rak M., Bovy L., Peters E., van Hooijdonk C.F.M., Mangiaruga A., Varatheeswaran R., Chaabou M., Gorman L., Wilson S., et al. Sleep fragmentation and lucid dreaming. Conscious. Cogn. 2020;84:102988. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2020.102988. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Watson D. Dissociations of the night: Individual differences in sleep-related experiences and their relation to dissociation and schizotypy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2001;110:526–535. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.110.4.526. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Soffer-Dudek N., Shahar G. Daily Stress Interacts With Trait Dissociation to Predict Sleep-Related Experiences in Young Adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011;120:719–729. doi: 10.1037/a0022941. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2011;120:719–729. doi: 10.1037/a0022941. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Sikka P., Valli K., Virta T., Revonsuo A. I know how you felt last night, or do I? Self- and external ratings of emotions in REM sleep dreams. Conscious. Cogn. 2014;25:51–66. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2014.01.011. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Snyder F. The phenomenology of dreaming. In: Madow L., Snow L., editors. Psychodynamic Implications of the Physiological Studies on Dreams. Charles S Thomas; Springfield, MO, USA: 1970. pp. 124–151. [Google Scholar]

64. Merritt J.M., Stickgold R., Pace-Schott E., Williams J., Hobson J.A. Emotion Profiles in the Dreams of Men and Women. Conscious. Cogn. 1994;3:46–60. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1994.1004. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Strauch I., Meier B. Search of Dreams: Results of Experimental Dream Research. SUNY PRESS; New York, NY, USA: 1996. [Google Scholar]

66. Fosse R., Stickgold R., Hobson J.A. The mind in REM sleep: Reports of emotional experience. Sleep. 2001;24:947–955. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.8.1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Sleep. 2001;24:947–955. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.8.1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Sikka P., Feilhauer D., Valli K.J., Revonsuo A. How you measure is what you get: Differences in self- and external ratings of emotional experiences in home dreams. Am. J. Psychol. 2017;130:367–384. doi: 10.5406/amerjpsyc.130.3.0367. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Zadra A., Donderi D.C. Nightmares and bad dreams: Their prevalence and relationship to well-being. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 2000;109:273–281. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.109.2.273. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Schredl M. Effects of state and trait factors on nightmare frequency. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 2003;253:241–247. doi: 10.1007/s00406-003-0438-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Sikka P. Dream Affect: Conceptual and Methodological Issues in the Study of Emotions and Moods Experienced in Dreams. University of Turku; Turku, Finland: 2020. [Google Scholar]

71. Hyyppä M.T., Kronholm E. , Mattlar C.-E. Mental well-being of good sleepers in a random population sample. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1991;64:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1991.tb01639.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Mattlar C.-E. Mental well-being of good sleepers in a random population sample. Br. J. Med. Psychol. 1991;64:25–34. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1991.tb01639.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Wegner D.M., Wenzlaff R.M., Kozak M. Dream Rebound: The Return of Suppressed Thoughts in Dreams. Psychol. Sci. 2004;15:232–236. doi: 10.1111/j.0963-7214.2004.00657.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Taylor F., Bryant R.A. The tendency to suppress, inhibiting thoughts, and dream rebound. Behav. Res. Ther. 2007;45:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.005. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Kröner-Borowik T., Gosch S., Hansen K., Borowik B., Schredl M., Steil R. The effects of suppressing intrusive thoughts on dream content, dream distress and psychological parameters. J. Sleep Res. 2013;22:600–604. doi: 10.1111/jsr.12058. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Freud S. The Interpretation of Dreams. Wordsworth; Hertfordshire, UK: 1990. [Google Scholar]

76. Drummond S.P.A., Paulus M.P., Tapert S.F. Effects of two nights sleep deprivation and two nights recovery sleep on response inhibition. J. Sleep Res. 2006;15:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00535.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Drummond S.P.A., Paulus M.P., Tapert S.F. Effects of two nights sleep deprivation and two nights recovery sleep on response inhibition. J. Sleep Res. 2006;15:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2006.00535.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Zhao W., Gao D., Yue F., Wang Y., Mao D., Chen X., Lei X. Response Inhibition Deficits in Insomnia Disorder: An Event-Related Potential Study with the Stop-Signal Task. Front. Neurol. 2018;9:610. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2018.00610. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Malinowski J., Carr M., Edwards C., Ingarfill A., Pinto A. The effects of dream rebound: Evidence for emotion-processing theories of dreaming. J. Sleep Res. 2019;28 doi: 10.1111/jsr.12827. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Gilchrist S., Davidson J., Shakespeare-Finch J. Dream Emotions, Waking Emotions, Personality Characteristics and Well-Being—A Positive Psychology Approach. Dreaming. 2007;17:172–185. doi: 10.1037/1053-0797.17.3.172. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Yu C.K.C. Emotions Before, During, and After Dreaming Sleep. Dreaming. 2007;17:73–86. doi: 10.1037/1053-0797.17.2.73. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Yu C.K.C. Emotions Before, During, and After Dreaming Sleep. Dreaming. 2007;17:73–86. doi: 10.1037/1053-0797.17.2.73. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Sikka P., Revonsuo A., Noreika V., Valli K. EEG frontal alpha asymmetry and dream affect: Alpha oscillations over the right frontal cortex during rem sleep and presleep wakefulness predict anger in REM sleep dreams. J. Neurosci. 2019;39:4775–4784. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2884-18.2019. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

82. Fernandez E., Woldgabreal Y., Guharajan D., Day A., Kiageri V., Ramtahal N. Social Desirability Bias Against Admitting Anger: Bias in the Test-Taker or Bias in the Test? J. Pers. Assess. 2019;101:644–652. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2018.1464017. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

83. Baumeister R.F., Bratslavsky E., Finkenauer C., Vohs K.D. Bad is Stronger than Good. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 2001;5:323–370. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.4.323. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. Lusic Kalcina L. , Valic M., Pecotic R., Pavlinac Dodig I., Dogas Z. Good and poor sleepers among OSA patients: Sleep quality and overnight polysomnography findings. Neurol. Sci. 2017;38:1299–1306. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2978-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Valic M., Pecotic R., Pavlinac Dodig I., Dogas Z. Good and poor sleepers among OSA patients: Sleep quality and overnight polysomnography findings. Neurol. Sci. 2017;38:1299–1306. doi: 10.1007/s10072-017-2978-6. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Conte F., Cerasuolo M., Fusco G., Giganti F., Inserra I., Malloggi S., Di Iorio I., Ficca G. Sleep continuity, stability and organization in good and bad sleepers. J. Health Psychol. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1359105320903098. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

86. Zadra A., Domhoff G.W. Dream content: Quantitative findings. In: Kryger M.H., Roth T., Dement W.C., editors. Principles and Practice of Sleep Medicine. 6th ed. Elsevier; Philadelphia, PA, USA: 2017. pp. 515–522. [Google Scholar]

87. Schredl M. Dream content analysis: Basic principles. Int. J. Dream Res. 2010;3:65–73. doi: 10.11588/ijodr.2010.1.474. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Good sleep - a dream? | PSYCHOLOGIES

Health and BeautyListen to your body

Sleep problems are a human lot. This does not happen with animals. The thing is that in our brain there are areas that are able to “postpone” falling asleep and keep us active. This property is useful in case of danger or urgent work. But it sometimes turns against us and does not allow us to fall asleep, even when there is no need to stay awake.

This does not happen with animals. The thing is that in our brain there are areas that are able to “postpone” falling asleep and keep us active. This property is useful in case of danger or urgent work. But it sometimes turns against us and does not allow us to fall asleep, even when there is no need to stay awake.

Thus, 56% of the population in the USA, 31% in Western Europe and 23% in Japan complain of insomnia. Most of them say that it affects daily life, family relationships and work. But almost half of those who have sleep problems have never tried to solve them 1 .

Strong stress, anticipation of exciting events - this is enough for us to stay awake despite our desire

Also, sleep depends on the biological clock, which regulates the alternation of wakefulness and sleep. “They can be out of sync, they can be late, they can show half past eight in the evening, when it’s actually midnight,” explains Stanford University professor and sleep disorder specialist William Dement. As a result, we cannot sleep.

As a result, we cannot sleep.

Another difficulty: sleep is not continuous, there are several micro-awakenings during the night. Our brains sometimes make us think these awakenings are longer than they really are. Why this happens is still unknown to science. And in the morning we wake up tired, as if we had not closed our eyes.

To each his own insomnia?

Today there is no scientific definition of insomnia. It is not considered a disease, but a disorder, the extent of which can only be determined by the one who complains about it. Insomnia is mainly a feeling that sleep does not satisfy us and does not restore enough strength.

There are people who feel great despite sleeping five hours a day and waking up frequently 2 . They are called "little sleepers". “Each of us builds and lives our insomnia on our own,” says sleep psychologist Patrick Levy. So insomnia is a personal matter for everyone.

Still, insomnia can be divided into three main categories: sleep disturbance, early awakening, and frequent waking

“I wait hours to sleep,” complains 26-year-old Sophia. - As soon as I feel tired, I go to bed, but the dream immediately disappears. I start to get nervous, I start thinking about all the problems for the day. Terrible!"

- As soon as I feel tired, I go to bed, but the dream immediately disappears. I start to get nervous, I start thinking about all the problems for the day. Terrible!"

“The morning became a problem for me,” admits 43-year-old Yakov. - Half past five in the morning, I wake up - and sleep is not in one eye. I don't know what's wrong with me. The worst thing is that I feel bad, I can neither read nor work. Dark thoughts overwhelm me. As a result, I wake up tired, in a bad mood. I become more and more irritable and impatient. It's hard for other people to be around me."

“I wake up many times a night,” says Alexander, 32. “I constantly toss and turn at night, and this bothered my friend so much that she left me.”

These three types of insomnia can occur in the same person at different stages of life. They are related to the events that we are experiencing.

Causes of insomnia

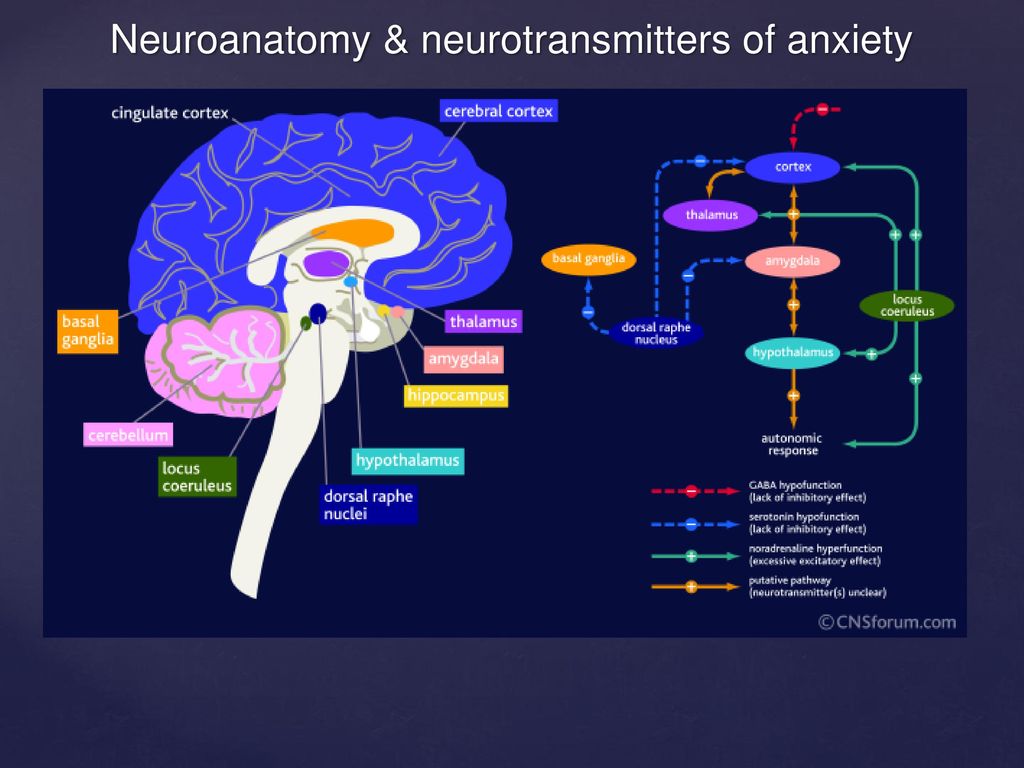

- Anxiety. Sleep is disturbed mainly when we are overwhelmed with problems.

If the problems never end, then the person is extremely anxious by nature. Many of those who experience this kind of difficulty struggle with insomnia by taking small doses of sedatives. Will psychotherapy help in this case? It will not cure insomnia immediately, but it will change the attitude towards anxiety. As a result, most clients who turn to a psychotherapist for help gradually return to restful sleep.

If the problems never end, then the person is extremely anxious by nature. Many of those who experience this kind of difficulty struggle with insomnia by taking small doses of sedatives. Will psychotherapy help in this case? It will not cure insomnia immediately, but it will change the attitude towards anxiety. As a result, most clients who turn to a psychotherapist for help gradually return to restful sleep. - Depression. Morning insomnia is indicative of latent depression. In this case, depression needs to be treated first, explains sleep disorder psychiatrist Sylvie Royan-Parola. There is a mysterious but undeniable connection between depression and insomnia. Stress, shock, loss of a loved one often disrupt sleep. These disturbances usually disappear with time. But this does not always happen, and then there is a "psychophysiological" insomnia. Those who suffer from it complain of restlessness that keeps them awake. It comes to the point that the desire to fall asleep becomes an obsession, which in itself prevents sleep.

- Unconscious. In the form of insomnia, problems hidden in our unconscious can manifest themselves. This almost always applies to those who wake up several times a night for no apparent reason. This happens when we are afraid to be in the power of sleep and lose conscious control. Charles Baudelaire experienced such fear. “I am afraid of sleep, as they are afraid of a huge hole with many obscure horrors coming from the unknown,” he admitted. According to Freud, in our unconscious desire for death is in constant struggle with the desire for life. Panic before sleep is connected with this struggle.

Why don't the children sleep?

In adults, sleep is usually disturbed by stress. And insomnia that arose in childhood is often associated with the fear of parting, says Sylvie Royan-Parola.

An anxious mother worries about something happening to her child during sleep. Out of an unconscious sense of fidelity, he will respond to her by not falling asleep or by waking up frequently. Over time, the memory of the mother's anxiety will leave the child's mind, but insomnia will remain.

Over time, the memory of the mother's anxiety will leave the child's mind, but insomnia will remain.

There is also a kind of “transmission” of insomnia from parents to children. “Every child’s sleep is interrupted. This is fine. But a parent with a sleep disorder tends to respond according to their attitude towards falling asleep, emphasizes Sylvie Royan-Parola. - He says to the child: “You are not sleeping, just like me. I'll give you herbal tea." So the child convinces himself that he will not fall asleep without outside help.

Helping yourself to sleep

“For those suffering from sleep disorders, lying in bed means staying awake,” says Sylvie Royan-Parola. “Therefore, another attitude should be created: to equate “lying in bed” with “sleeping.” And if you can’t fall asleep, force yourself to leave the room, no matter how much the clock shows. You should go to bed only when drowsiness comes.

If you feel unwell, you can turn to sleeping pills. “But you should not take it every night, not only to avoid addiction, but also because the medicine stops working after a few days,” warns Sylvie Royan-Parola.

As a rule, people get ready for bed. Each of us has an evening ritual: drink a glass of water or warm milk, read a little, pray... These soothing activities take us back to the time when we fell asleep after a parental kiss with a teddy bear in our hands. And it replaces for us “transitional objects” (pacifier, favorite toy, mother's handkerchief), which in childhood were associated with the mother and helped to maintain contact, even when she was not around.

5 rules for good sleep

These principles are simple but effective at the same time:

- do not consume caffeine at the end of the day;

- go to bed and get up at the same time, at least approximately;

- learn to relax;

- avoid any exciting activity before going to bed (in particular, never pay bills in the evening).

- attention should be paid to using a computer at night: strong light from the screen can cause the brain to "think" that it is daytime and not yet time to prepare for rest.

Sleep problems begin at about forty years of age - sleep becomes more superficial, intermittent. But do not rush to immediately contact the doctors. Walking, physical activity, a change of scenery, falling in love ... often enough to get rid of the most persistent insomnia.

1 "An international survey of sleeping problems in the general population", Current Medical Research and Opinion, 2008, No. 24.

2 97 clinical psychologist Maurice Ohayon (Maurice Ohayon), examining 12,000 sleepers in the UK and Quebec.

Text: Elza Lestvitskaya

New on the site

Age of uncertainty: why it is important to praise teenagers guilt before her does not let me live”

Are OnlyFans sexual perverts or not?

Life after 30: new rules for dating

How to know if a work colleague likes you

On the verge of a foul: why people like movies and TV shows about forbidden relationships

"I live in the Gravity Falls cartoon"

Sleep learning : Dreams Come True?

- David Robson

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

image copyrightThinkstock

Sleep learning used to seem like a pipe dream. But now neuroscientists claim to have found ways to develop a person's memory in a state of sleep. BBC Future .

Before getting under the covers, carefully prepare the bedroom: a few drops of aromatic essence on the pillow, on the ears - headphones, on the head - a strange-looking bandage. Now you can go to sleep. This ritual takes only a few minutes, but it is hoped that it will help speed up the process of mastering a variety of intricacies: from playing the piano and tennis to French. In the morning, nothing from the night "lesson" will remain in memory, but this is not important - the result is still there.

Once upon a time, the idea of learning in a dream seemed simply absurd, but today there are already several ways - high-tech and not so - that will allow you to acquire new knowledge during the rest period. And although there are no methods for mastering something in the unconscious state from scratch, this does not mean that sleep time cannot be used to develop memory. At night, the human brain actively processes and generalizes memories of the day. Why not stimulate this process?

At night, the human brain actively processes and generalizes memories of the day. Why not stimulate this process?

Since we spend a third of our lives in the arms of Morpheus, it is not surprising that the idea of learning by sleeping has long captured the imagination of artists and writers. In most cases, it is embodied in the image of a hero who subconsciously learned new information from an audio recording that was playing in the background. For example, in the dystopian novel Brave New World by English writer Aldous Huxley, a Polish boy learns English by listening to a lecture by Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw in his sleep on the radio, and soon the authoritarian government of the "new world" begins to use this method for indoctrination their subjects.

Here is an example from a recent work: the character of the animated series "The Simpsons" Homer buys an audio cassette that affects the subconscious during sleep and promises to reduce appetite. However, the cassette instead contributes to a change in his vocabulary, and when his wife Marge asks him if such a diet helped him, Homer, who usually speaks very primitively, suddenly says: "It's sad, but no. My gastronomic capacity knows no satiety."

However, the cassette instead contributes to a change in his vocabulary, and when his wife Marge asks him if such a diet helped him, Homer, who usually speaks very primitively, suddenly says: "It's sad, but no. My gastronomic capacity knows no satiety."

Anti-science

In fact, this kind of sleep learning is almost certainly impossible. Although some early studies showed that participants in the experiment could memorize a number of facts in their dreams, it could not be said with certainty that they did not wake up and hear the recording while awake. To test this, American scientists Charles Simon and William Emmons began to attach electrodes to the head of their wards and play cassettes only when people were in a state of sleep. As expected, after falling asleep, the participants in the experiment did not remember anything.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image caption A dream of many students: learning in their sleep. Straight to the lecture

Straight to the lecture

These results were published in the 1950s, but over the years entrepreneurs have tried to capitalize on the attractive prospect of quick and easy learning, even though their methods were not based on any scientific basis.

However, despite the fact that during sleep the brain does not perceive any new information, it is by no means inactive, but sorts through the impressions accumulated during the day and directs them from the hippocampus, where memories are believed to be formed, to those areas of the cortex in which they are formed. are stored. "This allows you to fix memories and consolidate them into a long-term memory system," says Susanne Dikelman from the University of Tübingen (Germany). Sleep also helps to generalize what has been learned, making it possible to apply the acquired skills in new situations. And although we are unable to absorb new material in a dream, instead, we can consolidate the knowledge and skills acquired during the day.

Aromamethod

At the moment, at least four methods are promising. The simplest was obtained as a result of research conducted in the 19th century by a French nobleman - the Marquis d'Herve de Saint-Denis. Studying ways to influence dreams, the Marquis found that he could awaken some memories in himself with the help of appropriate smells, tastes or sounds.

In one of his experiments, he drew a half-naked woman while chewing an orris root. When the marquis fell asleep, the servant put the same root in his mouth, and the familiar tart taste brought back dreams in which the same beauty stood in the theater foyer. She was wearing "a costume that the theater committee would hardly consider acceptable," the researcher wrote enthusiastically in his book Dreams and How to Control Them.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image captionUnfortunately, the alarm clock rarely waltzes...

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

On another occasion, he asked the conductor of the orchestra to play certain waltzes while dancing with one of two particularly beautiful ladies. Then the marquis attached a clock to the music box so that it played the same tunes at night - apparently thanks to them he saw in a dream the lovely figures of his partners.

The Frenchman simply wanted to decorate his dreams with pleasant (and sometimes voluptuous) sensations, but now we see that the same method can make the brain play out previously learned things in a dream, thereby strengthening memory.

So, Dikelman asked volunteers to play the game "Concentration", in which it is required to memorize the location of objects on the playing field, and then go to bed. Some participants in the experiment played in a room scented with a slight artificial scent, and then the researchers exposed them to the same scent while they slept. Brain scans showed that these subjects had more active interaction between the hippocampus and certain areas of the cerebral cortex than those who did not apply the smell, and it is this activity that contributes to enhanced memory consolidation. As a result, these participants remembered the location of approximately 84% of objects upon awakening, and the control group only 61%.

Some participants in the experiment played in a room scented with a slight artificial scent, and then the researchers exposed them to the same scent while they slept. Brain scans showed that these subjects had more active interaction between the hippocampus and certain areas of the cerebral cortex than those who did not apply the smell, and it is this activity that contributes to enhanced memory consolidation. As a result, these participants remembered the location of approximately 84% of objects upon awakening, and the control group only 61%.

Not only pleasant smells help to learn. As the Marquis established with his lullaby waltzes, sounds can also evoke memories - unless, of course, they also awaken the sleeping person. In one study, volunteers mastered a musical game based on the simulation of playing a composition faster if they listened to quiet fragments of a melody during sleep.

At the same time, professor at the University of Zurich (Switzerland) Bjorn Rasch came to the conclusion that the same method allows German-speaking Swiss to learn Dutch - with its help they memorized about 10% more words.

Technical innovations

In the near future, due to the development of technology, other methods based on the use of sleep cycles may appear. It is believed that memory consolidation occurs during certain, slow electrical oscillations of the brain, in connection with which the idea arose to gently stimulate such impulses without waking the person.

Jan Born, a professor at the University of Tübingen, became the main ideologist of such experiments. In 2004, he found that brain signals could be activated using the transcranial direct current stimulation method, by applying a weak current to the subject's skull, which significantly improved the ability to remember words.

Image copyright, Thinkstock

Image caption, The goal is to make sleep learning less invasive... sound synchronized with brain impulses. Bourne compares this auditory stimulation to the gentle push of a seesaw to help the child swing. This method gently stimulates the neural activity that already occurs in the brain. "NREM sleep becomes deeper and more intense," Born says. "It's a more natural way of influencing brain rhythms."

This method gently stimulates the neural activity that already occurs in the brain. "NREM sleep becomes deeper and more intense," Born says. "It's a more natural way of influencing brain rhythms."

For those who don't want to go to bed with bulky headphones, Miriam Reiner, an associate professor at the Technion Institute of Technology in Haifa, Israel, offers a more elegant solution based on using a form of neural response so that participants in the experiment can control neural activity. in the waking state. To do this, an electrode is attached to their heads, associated with a simple computer game in which participants must control a car with the power of their mind.

When the electrode captures the correct frequency of brain impulses, which are usually associated with the consolidation of memory during sleep, the speed of the car increases, with a change in frequency, the movement slows down. It usually only takes a few minutes for the participants to start firing the required impulses, and Reiner argues that there is a measurable change in the process of thinking.

"I feel peaceful, as if I'm walking in a garden or along the seashore. I feel like I'm transported to some wonderful quiet place." The idea is to stimulate memory consolidation immediately after learning by giving the brain an initial boost while processing the events of the day in sleep. "It's like a seed that sprouts overnight," Reiner says.

Play a melody

In exploring ways to influence learning, Reiner asked participants to first memorize a complex sequence of finger movements—much like learning a melody on a piano—and then undergo a 30-minute neural response stimulation session. The effect manifested itself immediately - immediately after training, the subjects showed results about 10% better than the control group, that is, the computer game really stimulated the consolidation of the acquired skills in memory, as if the participants in the experiment were really sleeping.

Image credit, Thinkstock

Image caption,Proper sleep will help you remember complex finger movement patterns

Importantly, results continued to improve over the following week, supporting Rayner's theory that stimulating a neural response can enhance memory during sleep.

Clearly, larger trials with many more participants will be required before these methods can be recommended for routine use.

In addition, so far, participants have been given somewhat artificial learning and memory tasks, so it makes sense to test these methods on more practical tasks. Reiner has already begun to move in this direction, exploring the possibility of applying the method of stimulating a neural response in learning to play the guitar.

According to Dickelman, it is also necessary to make sure that such an impact on memory will not have undesirable consequences. "It's possible that stimulating one set of memories harms another," she says.

In addition, Dikelman is convinced that we must not forget the problems posed in Brave New World and The Simpsons. In her opinion, such methods can hardly be used to indoctrinate people against their will, but the question of whether it is right to influence the memory of children in this way, for example, remains open: "In a dream, a person is vulnerable. "

"

However, Dickelman emphasizes that potential problems should not dampen interest in sleep learning. "It's worth it. You just have to approach the issue with all possible responsibility."

Little Tricks

Dikelman believes that after all these issues are resolved, there should not be too many practical obstacles left for people who want to try these methods for themselves. Many of her students and colleagues are already convinced that exposure to the senses in a dream helps them prepare for exams.

Image copyright Thinkstock

Image captionSleeping is vulnerable. Also for foreign languages

"It's very easy," Dikelman says. It is now possible to buy EEG devices that are compatible with a smartphone, and this opens up the prospect of creating games that stimulate memory consolidation. Even equipment for certain forms of transcranial direct current stimulation went on sale last year, so now we can expect the appearance of home devices for learning in a dream.