How many diagnoses in the dsm 5

Number of DSM Diagnoses - Evaluating Mental Health Patients

I'd like to get something off my chest about the number of diagnoses in the various DSMs. First, though, let me say that I don't have definitive, final numbers. That'll have to await better research and more thought.

My thoughts were set in motion by yet another statement (this time, in Psychiatric Times for July 2013, by S. Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH). In an article titled "Requiem for DSM," he notes that the number of diagnoses has grown from about two dozen (the Research Diagnostic Criteria of Spitzer et al (Archives of General Psychiatry, 1978; 35:773) to 265 diagnoses (not including modifiers) in DSM-5 today. Dr. Ghaemi calls 90% of the current DSM diagnoses unscientific, and says that DSM-5 is "91.9% false, based on the original 2 dozen RDC criteria divided by 297 DSM-IV diagnoses." Well, there's a lot there to talk about, but I'll confine myself to one issue, plus Dr. Ghaemi's conclusion--of which, more in a moment.

Quite frankly, I am getting a little weary of the meme that we suffer from diagnostic inflation and of the numbers that are floated to demonstrate it. Of course, there are more diagnoses now than there were 35 years ago, but is that so surprising? We've identified a fair number of new disorders, after all, and we've found nuances that are important to the treatment of our patients. Science marches on.

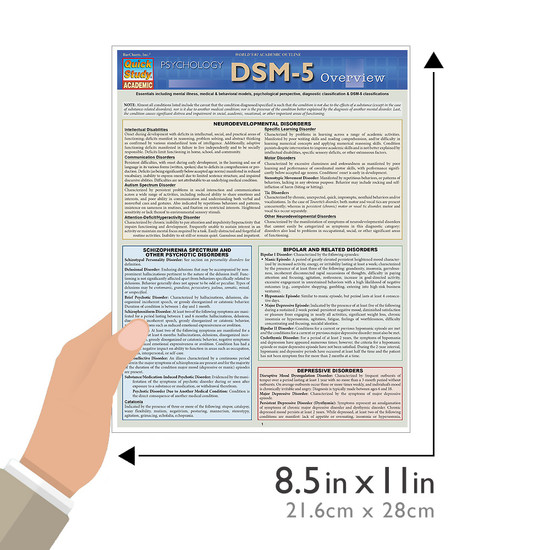

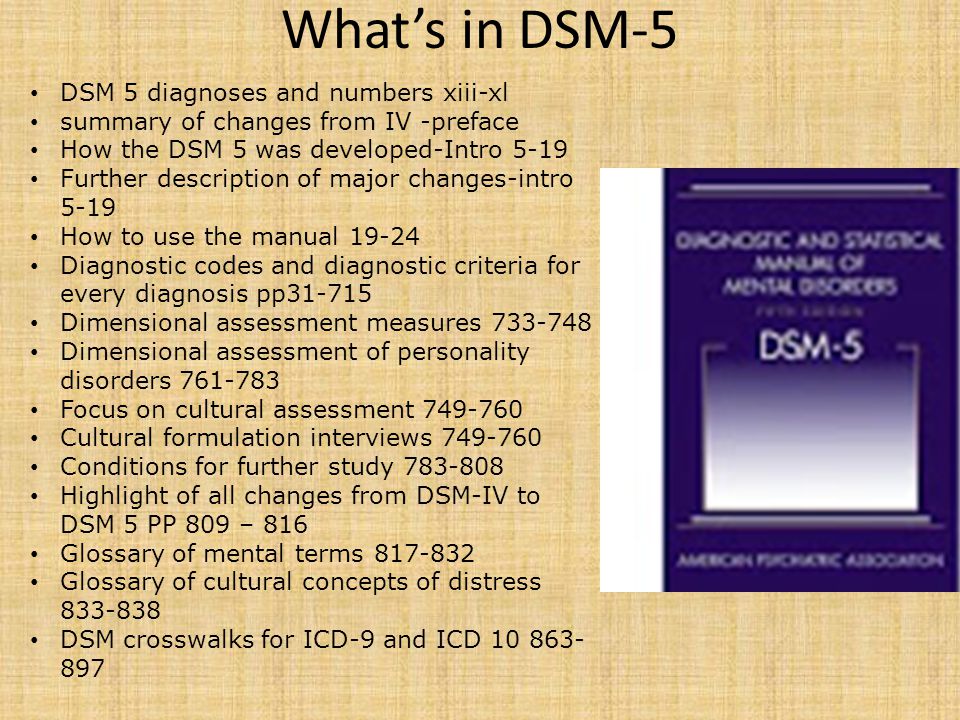

It all hinges on how and what we count. Stated one way, I can come up with 600 discrete diagnoses in DSM-5. That includes every numbered mental health diagnosis DSM-5 mentiones in connection with the forthcoming ICD-10 scheme. But of course, by no means does every one of these represent a distinct disease process. Many are simply a matter of degree (mild versus major neurocognitive disorder, for example), and many more are different states of what must be fundamentally the same process (say, bipolar depression single episode versus bipolar recurrent depression). And those 600 don't even include all the possibilities when you add in myriad specifiers..jpg) If we did add them in, their permutations could extend the count into the tens of thousands.

If we did add them in, their permutations could extend the count into the tens of thousands.

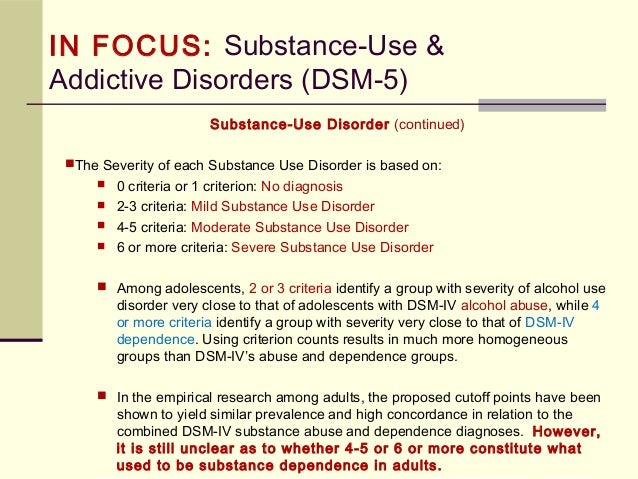

When I carefully count up what I consider to be discrete diagnoses in DSM-5, I reach the high water mark of 155; the semi-official count by those who wrote the book is 157--close enough that I didn't feel impelled to go hunting for the discrepancy. My count includes, for example, separate entries for bipolar I disorder, bipolar II disorder, dysthymic disorder (which we now call persistent mood disorder), and major depressive disorder--but not additional entries for bipolar I manic, bipolar I depressed, bipolar I hypomanic, &c. There's a separate entry for cocaine use disorder (the new term for what DSM-IV called cocaine dependence) and for cocaine intoxication and for cocaine withdrawal. Though each of these is a symptom of the use disorder, it can be diagnosed as a free-standing condition. I've included "substance-induced psychotic disorder" but not separate entries for alcohol-induced or cocaine-induced psychotic disorders. Of course, well-meaning people can disagree as to how to divide this particular pie. I'll be glad to send along my complete list to anyone who is truly interested.

Of course, well-meaning people can disagree as to how to divide this particular pie. I'll be glad to send along my complete list to anyone who is truly interested.

I'd be really happy to entertain other viewpoints about the total number we should be counting, but I think it's safe to say that 297 is a stretch, and that it is vastly overstating to say that DSM-5 is 91% false. On that issue, I truly beg to differ. This point of view claims that gender dysphoria is not a disorder, that anorexia nervosa is a fraud. Try telling that to the relatives of countless people who have died of that non-illness. There are any number of other disorders on the list that I'd claim are well-underpinned with experience and good research.

Further, the authors of the long-ago RDC criteria never intended that the number of acceptable diagnoses remain static, only that new disorders be based on studies that affirm reliability and, most importantly, validity. In large measure, the disorders included in DSM-5 do just that--though there are one or two exceptions that I reserve the right to discuss. Later.

Later.

It's Dr. Ghaemi's conclusion, however, that I find truly distressing. For he proposes to go his own way diagnostically, and by inference recommends that we all do the same, leaving "…clinicians free to use the best of what they know to diagnose, or not to diagnose, not because they are told to do so in a certain way by DSM, but in their best judgment of the art and science of psychiatry." This, of course, is the way to chaos, the same diagnostic anarchy that culminated, years ago, in a state of affairs in which American psychiatrists were wont, far more than their European counterparts, to lumber a psychotic patient with the diagnosis of "schizophrenia," disregarding symptoms that would lead many others to a finding of a mood disorder with psychosis. Whatever you think of the current DSM, the solution cannot be to disregard scientific research and rely on your instincts. No one's instinct is that good.

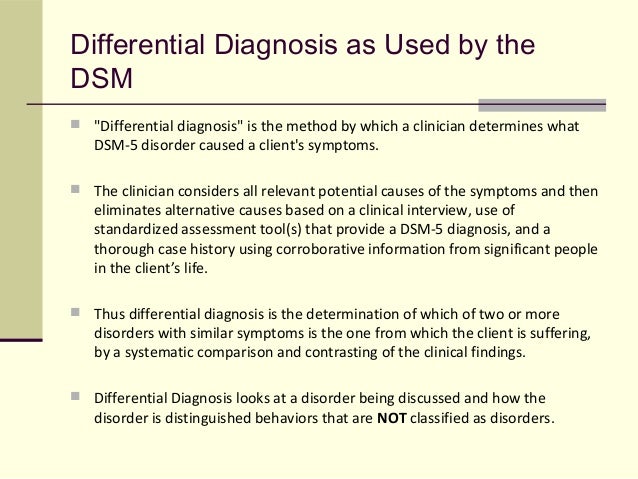

What is the DSM?

The DSM is a reference handbook that most U. S. mental health professionals use to reach an accurate diagnosis. The latest version of the manual is the DSM-5-TR.

S. mental health professionals use to reach an accurate diagnosis. The latest version of the manual is the DSM-5-TR.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) was released on March 18, 2022 by the American Psychiatric Association (APA).

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a formal classification of mental health disorders, featuring symptoms, diagnostic criteria, culture and gender-related features, and other important diagnostic information. The DSM does not include treatment guidelines.

In other words, the DSM is a tool and reference guide for mental health clinicians to diagnose, classify, and identify mental health conditions.

The DSM also includes “specifiers.” These are extensions to the formal diagnoses that specify one or more particular features, like onset or severity. A diagnosis can have one or more specifiers to make it more precise.

In other words, because a mental health condition doesn’t always present itself in the same way, a DSM specifier can better describe particular scenarios.

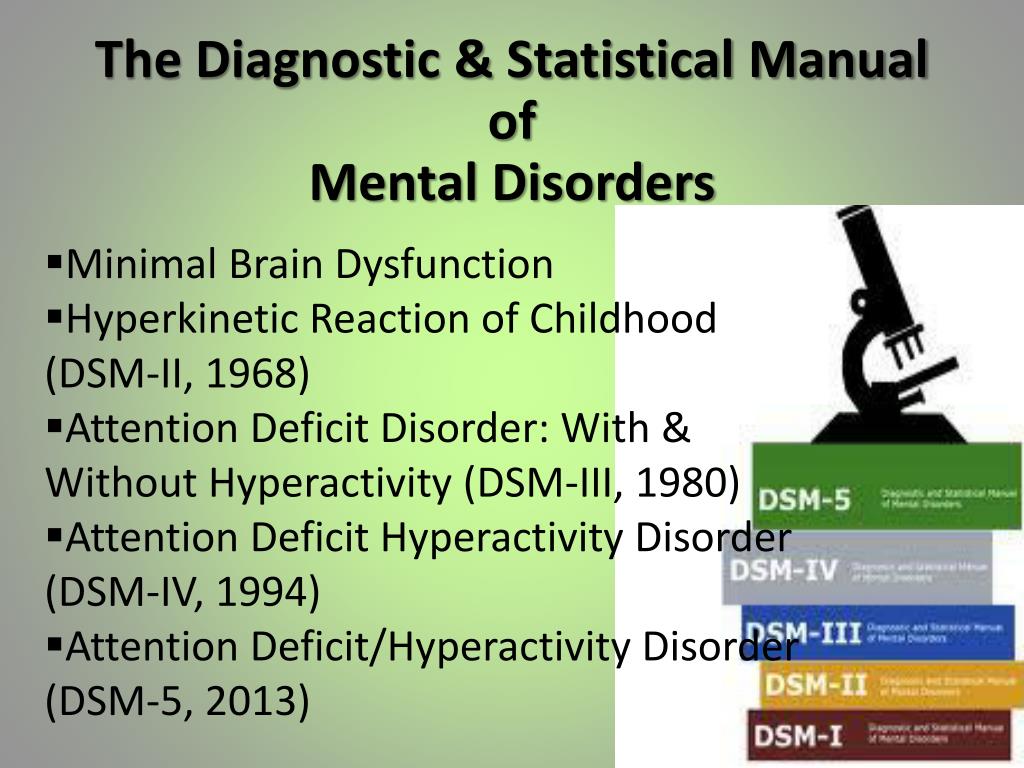

The DSM has had many revisions, to clarify, add, or remove mental health diagnoses according to the latest research and clinical consensus.

It took more than 13 years to update and finalize the book’s fifth edition and about 10 years to release the current text revision.

The DSM-5 was released in 2013 and the current version released in 2022 is the DSM-5-TR.

The difference between a new edition and a text revision is that the first one is released when new research supports the need to create, remove, or significantly revise key aspects of existing diagnoses.

A text revision, on the other hand, refers to editing the existing text to clarify some concepts, introduce inclusive language, or update statistics and references. Sometimes, like it’s the case with the DSM-5-TR, a new diagnosis might be introduced.

The first edition of the DSM was published in 1952 following an increased need to classify and define mental conditions, especially in veterans returning home after World War II.

The DSM was created to catalog mental health conditions similar to its counterpart, the International Classification of Disease (ICD).

The ICD is published by the World Health Organization (WHO) and catalogs both physical and mental conditions.

The DSM-II was released in 1968 and focused on broadening terms and definitions from the original DSM to diagnose mental health conditions better.

The biggest shift in the history of the DSM came as a result of the DSM-III, published in 1980.

This edition listed 265 categories — a big increase from 182 in the previous edition. This jump was due to an expansion of disorder subtypes, which allowed for more accurate classifications and options for a diagnosis.

The DSM-III also saw the removal of “homosexuality” as a mental condition category.

The DSM-III would later receive an update and be revised and renamed in 1987 as the DSM-III-R.

The next edition, the DSM-IV, was published in 1994 and was created alongside the WHO’s International Classification of Disease, 10th edition. This aimed to decrease inconsistencies in terminology between the two manuals.

This aimed to decrease inconsistencies in terminology between the two manuals.

The DSM-IV would see one final revision in 2000, named the DSM-IV-TR before the DSM-5 was released in 2013.

The latest text revision of the DSM-5 was released in 2022.

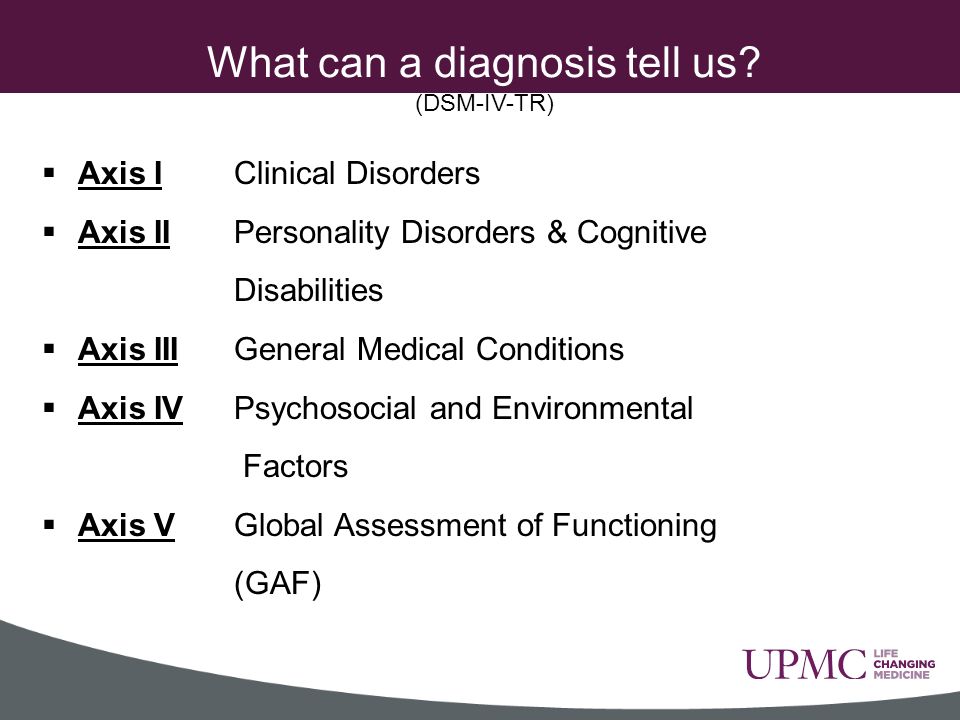

One of the biggest changes in the DSM-5 is the removal of the multiaxial assessment system to categorize diagnoses.

This evaluation method was based on multiple factors, specifically five “axes”:

- clinical disorders

- personality disorders

- general medical disorders

- psychosocial and environmental factors

- global assessment of functioning

The system was removed and replaced with a streamlined diagnostic method that combines axes I, II, and III into 1.

Additional changes in the DSM-5 include broadening the definitions to clarify certain conditions.

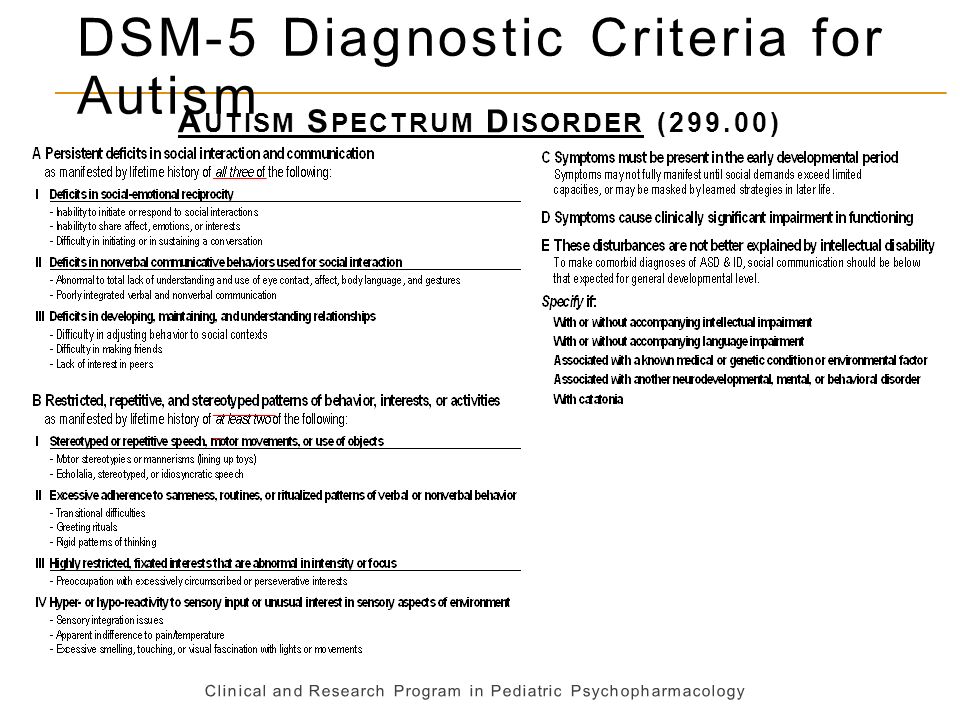

For example, the diagnostic label autism spectrum disorder now comprises four previously separate conditions:

- autistic disorder

- Asperger’s disorder

- childhood disintegrative disorder

- pervasive developmental disorder

The DSM-5 is organized into three sections and an appendix.

Section II of the DSM-5 is the lengthiest because it lists all of the mental health disorders.

Here are the DSM sections:

Section I: DSM-5 Basics

This section includes an “Introduction” and “Use of the Manual” chapters, as well as a “Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5” chapter.

Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

This section includes classifications and definitions of mental health disorders.

These conditions are organized alphabetically and developmentally, with all childhood conditions listed before adult on-set conditions.

Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

This section comprises chapters that discuss applying the newest mental health information — for example, assessment measures and how to account for cultural influences.

It also includes newer conditions that require further study before entering the general diagnostic classification — for example, caffeine use disorder and internet gaming disorder.

Appendix

The final section contains supplemental information such as a list of changes from the DSM-4 to the DSM-5, a glossary of technical terms, and a list of DSM-5 advisors.

Major changes in the DSM-5 from the DSM-IV

Below are links to explore additional updates and changes to the DSM-5:

- DSM-5 Released: The Big Changes

- DSM-5 Changes: Depression & Depressive Disorders

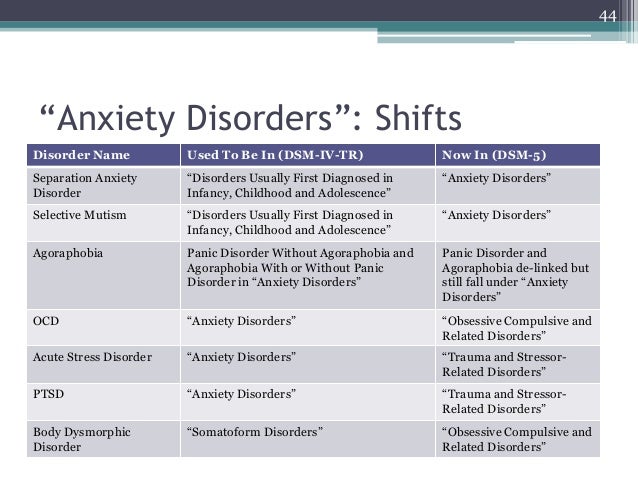

- DSM-5 Changes: Anxiety Disorders & Phobias

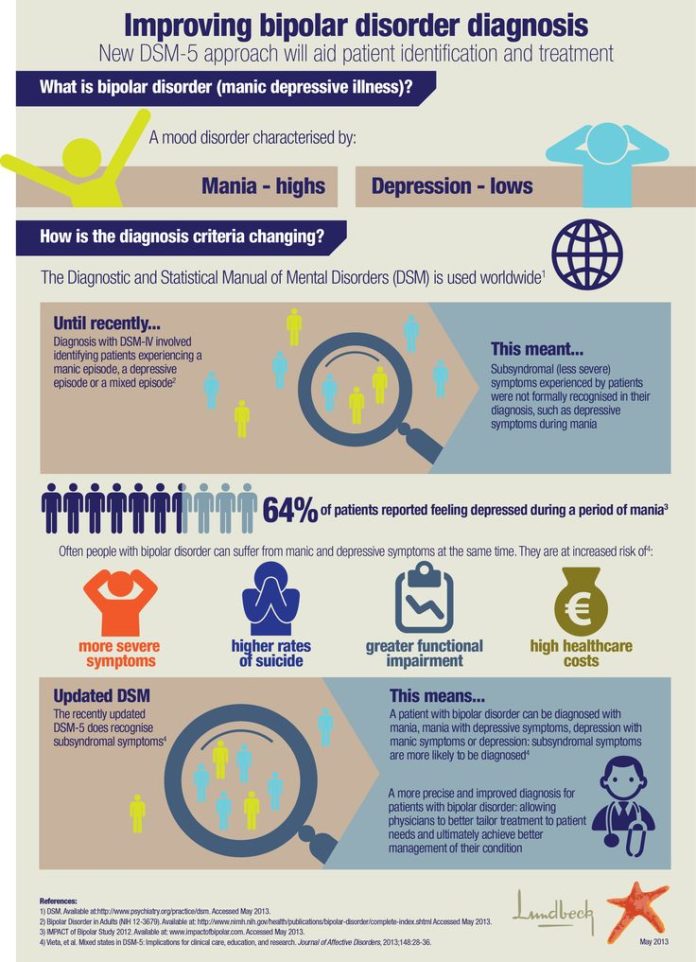

- DSM-5 Changes: Bipolar & Related Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Schizophrenia & Psychotic Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)

- DSM-5 Changes: Addiction, Substance-Related Disorders & Alcoholism

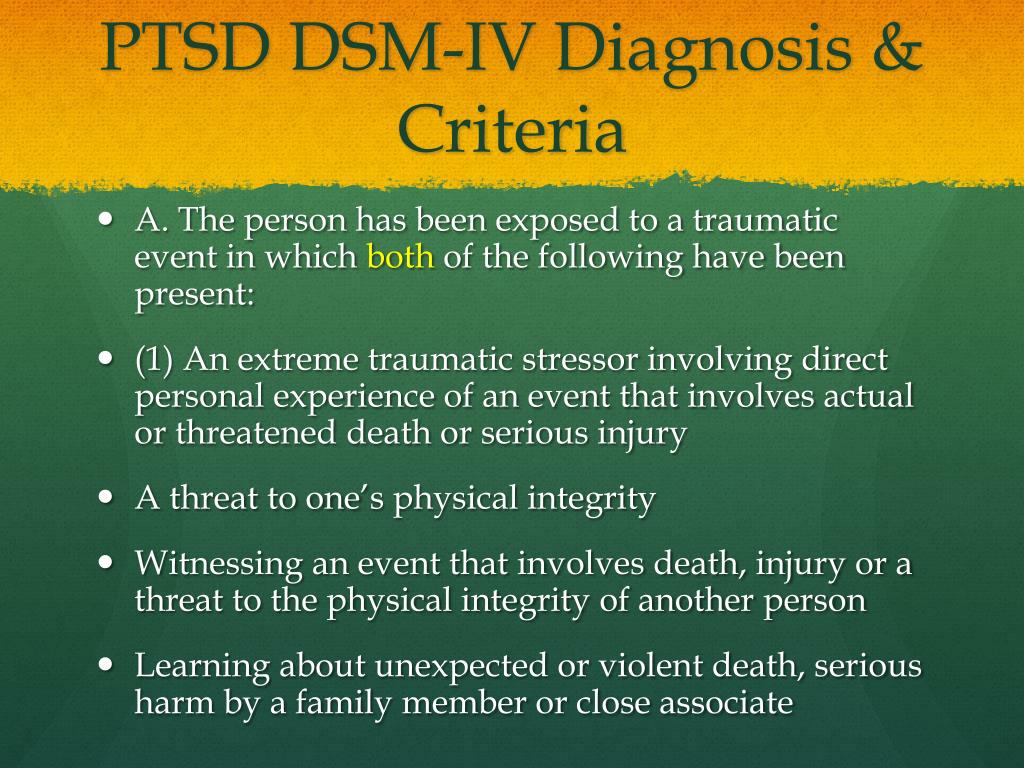

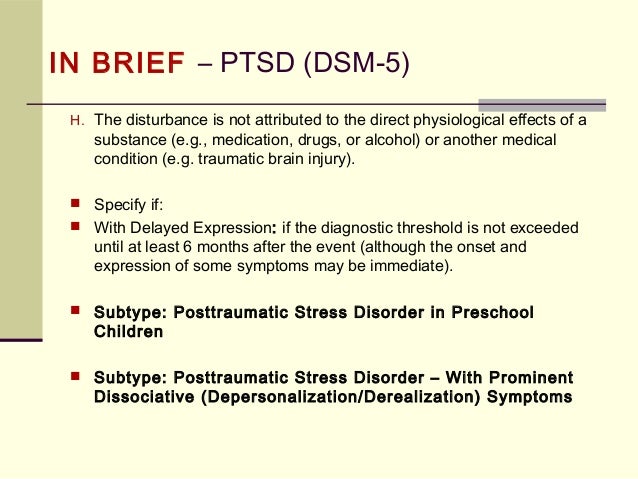

- DSM-5 Changes: PTSD, Trauma & Stress-Related Disorders

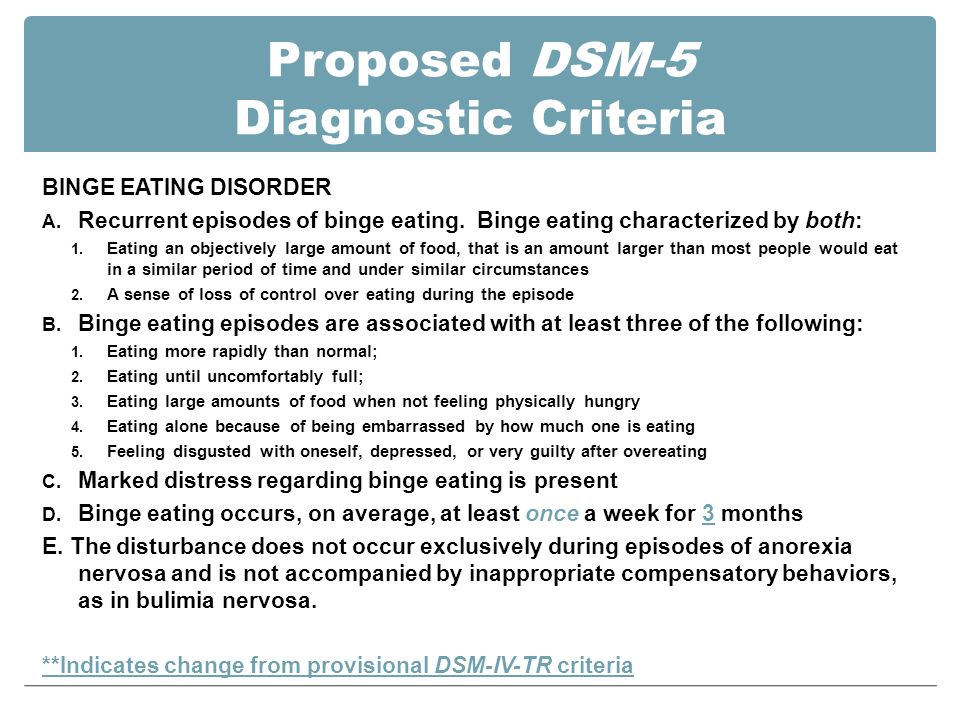

- DSM-5 Changes: Feeding & Eating Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Dissociative Disorders

- DSM-5 Changes: Personality Disorders (Axis II)

- DSM-5 Changes: Sleep-Wake Disorders

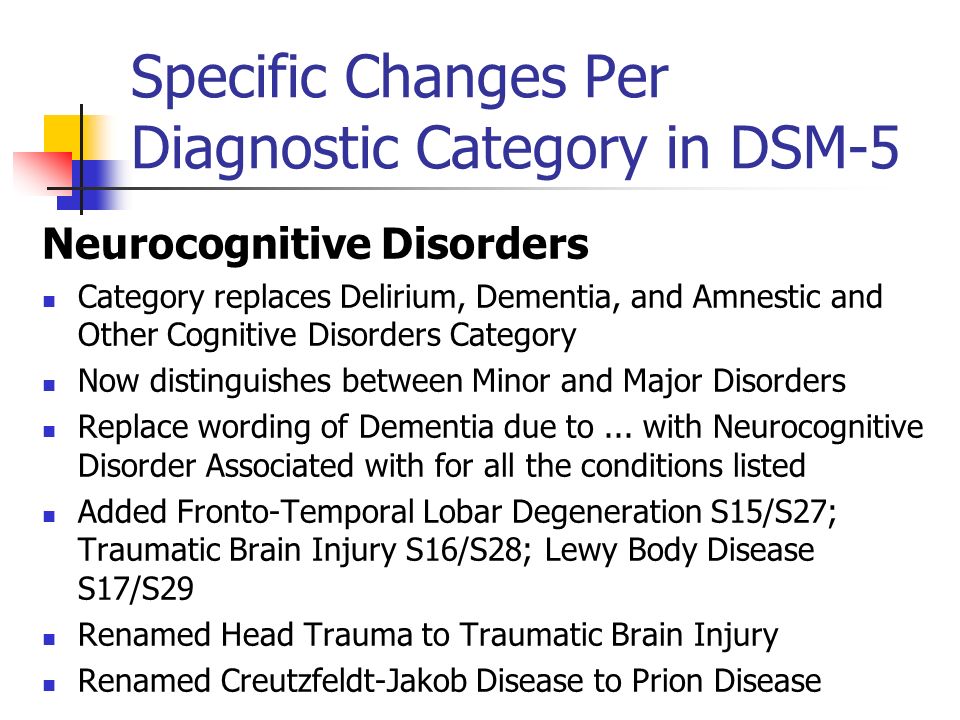

- DSM-5 Changes: Neurocognitive Disorders

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision (DSM-5-TR) is an edit of the DSM-5 that includes:

- a revision of the original descriptive text in the DSM-5, specifically under these headings:

- recording procedures

- specifiers

- diagnostic features

- associated features

- prevalence

- development and course

- risk and prognostic factors

- culture-related diagnostic issues

- sex and gender-related diagnostic issues

- association with suicidal thoughts or behavior

- functional consequences

- differential diagnosis

- comorbidity

- new and updated references to include more recent literature

- new text regarding the impact of discrimination and racism on mental health diagnoses

- a list of updated diagnostic codes from the International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision, clinical modification (ICD-10-CM), including codes related to suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-harm

- one new diagnosis (prolonged grief disorder) in section II, under trauma- and stressor-related disorders

- changes in language in the gender dysphoria chapter, going from “desired gender” to “experienced gender”

- changes in language to refer to gender-related procedures, going from “cross-sex medical procedure” to “gender-affirming medical procedure”

- changes in language in sex-related assignments, going from “natal male” or “natal female” to “individual assigned male at birth” and “individual assigned female at birth”

This is how the DSM-5-TR is indexed:

- DSM-5-TR Classification

- Preface

- Section I: DSM-5-TR Basics

- Introduction

- Use of the Manual

- Cautionary Statement for Forensic Use of DSM-5-TR

- Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes

- Neurodevelopmental Disorders

- Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders

- Bipolar and Related Disorders

- Depressive Disorders

- Anxiety Disorders

- Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders

- Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders

- Dissociative Disorders

- Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders

- Feeding and Eating Disorders

- Elimination Disorders

- Sleep-Wake Disorders

- Sexual Dysfunctions

- Gender Dysphoria

- Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Neurocognitive Disorders

- Personality Disorders

- Paraphilic Disorders

- Other Mental Disorders and Additional Codes

- Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication

- Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention

- Section III: Emerging Measures and Models

- Assessment Measures

- Culture and Psychiatric Diagnoses

- Alternative DSM-5 Model for Personality Disorders

- Conditions for Further Study

- Appendix

- Alphabetical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- Numerical Listing of DSM-5-TR Diagnoses and Codes (ICD-10-CM)

- DSM-5 Advisors and Other Contributors

- Index

More than 200 mental health experts contributed to the DSM-5-TR.

The DSM-5 offers an extensive list of conditions and symptoms that can aid mental health professionals in reaching accurate diagnoses. The latest version is the DSM-5-TR.

The manual has come a long way since its first edition and now provides diagnostic criteria for 193 mental health conditions.

The DSM is a living document that continues to change over time as we learn more about human cognition and behavior.

New American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 released to the world

Home > News > The new American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 is released to the world

| DSM-5 consists of three sections: it is (1) an introductory part with instructions for use and a warning about the forensic psychiatric use of the DSM-5; (2) diagnostic criteria and codes for routine clinical use; and (3) tools and techniques to inform clinical decision making. Major changes:

The severity of the disorder is not determined by IQ, but by the level of adaptive functioning.

For the diagnosis of schizophrenia, symptoms of the first Schneider rank lose their special weight. One positive symptom is required for a diagnosis to be made. Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately.

Bipolar and related disorders are now separated from depressive disorders and placed in a separate category. A clearer definition of mania is given and refinements for mixed episodes are introduced, which lowers the threshold for disorder. Added a residual subcategory ""other"" and a qualifying score for anxiety symptoms.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder added. Chronic depression and dysthymia are combined into one diagnosis, now it is ""persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)"" with a number of clarifying indicators. Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator ""mixed manifestations"" was introduced.

|

ISSN 2588-0519 (Print)

ISSN 2618-8473 (Online)

Annotated Index of National Psychological Journal Articles

How Our Word Resounds

3 National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.126-130

Zuckerman G.A.

moreDownload PDF

205

Life with love as the meaning of being in the existential paradigm of relationships

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.119-125

Utrobina V.G.

moreDownload PDF

230

Ecopsychological interactions of young children with other subjects of the social environment

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.108-188

No. 3. c.108-188

Lidskaya E.V. Panov V.I.

detailsDownload PDF

208

Application of the methodology "Diagnostics of the mental development of children from birth to three years" in clinical psychology and psychiatry

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.97-107

Trushkina S.V. Skoblo G.V.

moreDownload PDF

210

The Russian Museum of Childhood: on the development of a scientific concept

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.89-96

Sobkin V. S. Kalashnikova E. A. Lykova T. A.

moreDownload PDF

179

From Responsiveness to Self-Organization: A Comparison of Approaches to the Child in Waldorf and Directive Pedagogy

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.77-88

No. 3. c.77-88

E.A. Abdulaeva

detailsDownload PDF

138

E.O. Smirnova on the moral education of children

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.69-76

Burlakova I.A.

moreDownload PDF

137

Modern childhood and preschool education are on the protection of the rights of the child: to the 75th anniversary of E.O. Smirnova

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.60-68

Karabanova O.A.

moreDownload PDF

124

Contribution of E.O. Smirnova in the practice of education

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.52-59

Galiguzova L.N. Meshcheryakova S.Yu.

moreDownload PDF

115

Funny and scary in children's narratives: a cognitive aspect

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.44-51

No. 3. c.44-51

Shiyan O.A.

moreDownload PDF

172

E.O. Smirnova to the assessment of toys for children

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.35-43

Ryabkova I.A. Sheina E.G.

moreDownload PDF

165

The Artist in the Child

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.26-34

Melik-Pashaev A.A.

moreDownload PDF

164

Children's play as a territory of freedom

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.13-25

Yudina E.G.

moreDownload PDF

153

Dialectical structure of preschooler play

National Psychological Journal 2022.

Speech disorders have entered the new category "social communication disorder", in which some of the syndromes coincide with "autism spectrum disorder". The category "Autism Spectrum Disorders" replaces the DSM-4 diagnoses of autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and an unspecified general developmental disorder, all of which cease to exist as separate diagnoses. ADHD can start later (before 12) and is treated differently in different areas. Learning disorders and movement disorders are organized differently in this chapter and somewhat combined.

Speech disorders have entered the new category "social communication disorder", in which some of the syndromes coincide with "autism spectrum disorder". The category "Autism Spectrum Disorders" replaces the DSM-4 diagnoses of autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and an unspecified general developmental disorder, all of which cease to exist as separate diagnoses. ADHD can start later (before 12) and is treated differently in different areas. Learning disorders and movement disorders are organized differently in this chapter and somewhat combined.  The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders.

The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders.  A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. 9(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses.

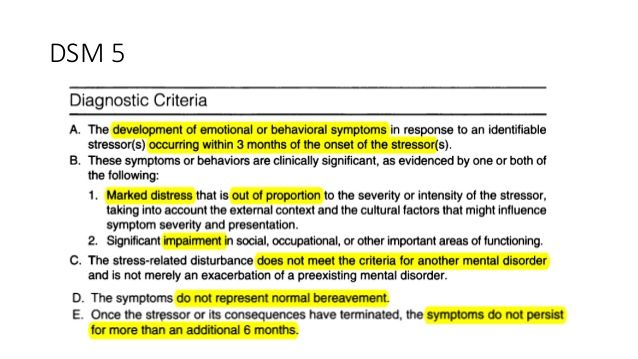

A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. 9(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses.  Also ruled out is the requirement to directly experience fear, horror, or feelings of helplessness. Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter.

Also ruled out is the requirement to directly experience fear, horror, or feelings of helplessness. Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter.  Removed somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, and unspecified somatoform disorder from DSM. A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group.

Removed somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, and unspecified somatoform disorder from DSM. A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group.  The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses.

The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses.  In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined.

In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined.