How is sex different from gender

What is the difference between sex and gender?

Exploring the difference between sex and gender, looking at concepts that are important to the Sustainable Development Goals.

This is the latest release.

View previous releases

1. Introduction

This article sets out the interpretation of the terms “sex” and “gender”, which the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and UK government bodies will be using to assess how the UK is progressing towards the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

!

The government definitions of "sex" and "gender" included in this article are not current and do not reflect a current cross-government agreed position. They are only intended for use within the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) context.

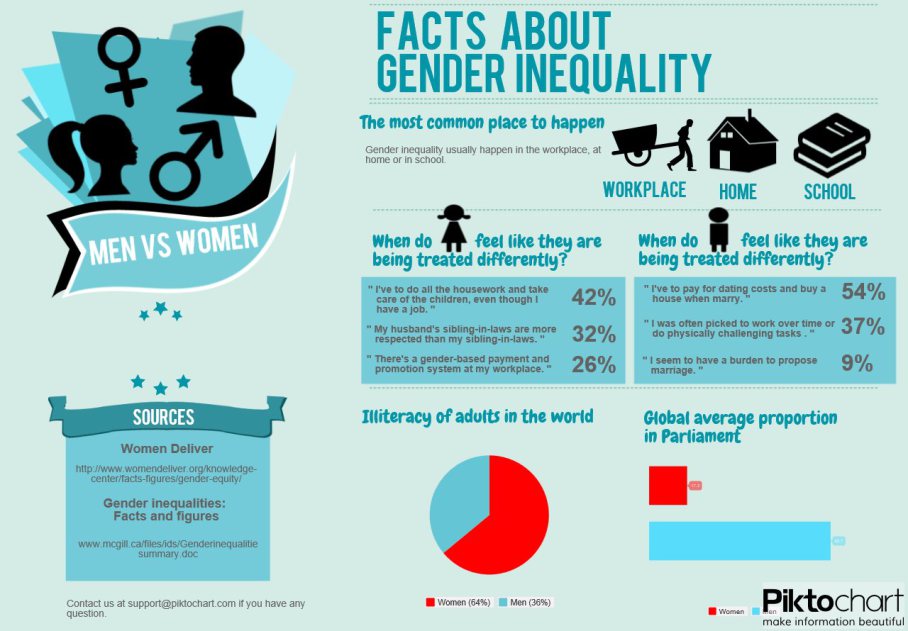

SDGs are a universal call to action to end poverty, protect the planet and ensure that all people enjoy peace and prosperity by 2030. The goals cover a range of areas, including health, the environment, the economy and inequalities. Sex and gender are relevant across the SDGs as a whole, but are particularly important for Goal 5: Gender equality.

As the UK’s national statistics institute, ONS is responsible for monitoring the UK’s progress towards the global SDG indicators. Part of this role includes putting the data into context. For more information about SDGs, please see our online reporting platform.

Download this image

.png (59.4 kB)

Sex and gender are terms that are often used interchangeably but they are in fact two different concepts, even though for many people their sex and gender are the same. This article will clarify the differences between sex and gender and why these differences are important to understand, especially in research and data collection. How and why sex and gender is important for SDGs and the principle of “leave no one behind” will be considered. It includes the UK government position on these concepts. ONS has done a lot of research and participated in discussions to understand these terms.

It includes the UK government position on these concepts. ONS has done a lot of research and participated in discussions to understand these terms.

2. Definitions and differences

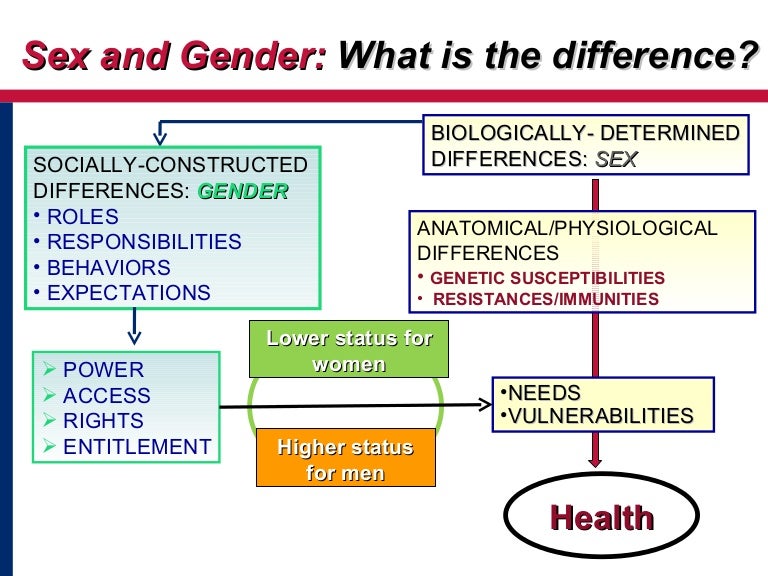

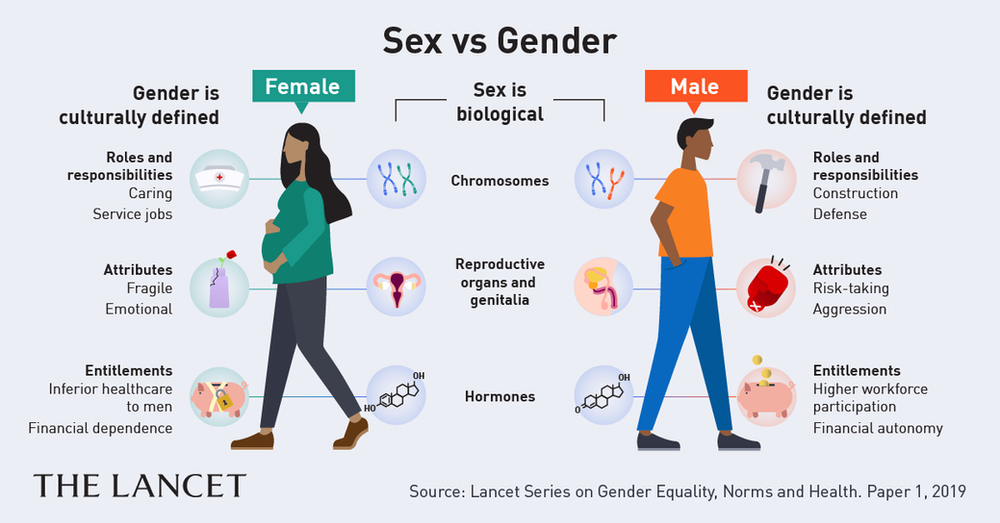

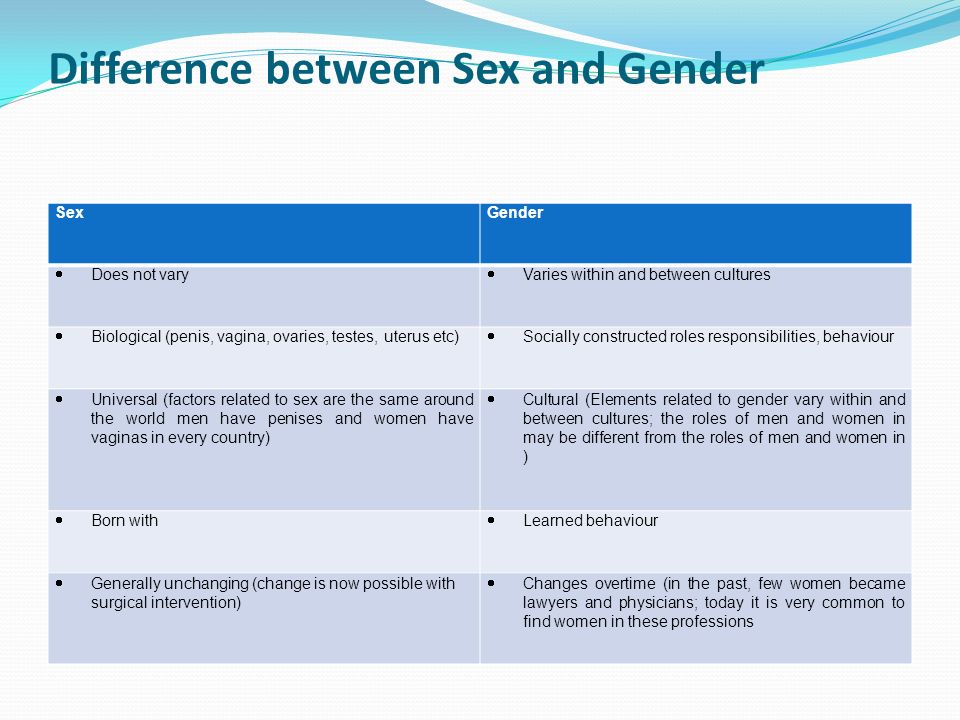

The UK government defines sex as:

referring to the biological aspects of an individual as determined by their anatomy, which is produced by their chromosomes, hormones and their interactions

generally male or female

something that is assigned at birth

The UK government defines gender as:

a social construction relating to behaviours and attributes based on labels of masculinity and femininity; gender identity is a personal, internal perception of oneself and so the gender category someone identifies with may not match the sex they were assigned at birth

where an individual may see themselves as a man, a woman, as having no gender, or as having a non-binary gender – where people identify as somewhere on a spectrum between man and woman

The World Health Organisation regional office for Europe describes sex as characteristics that are biologically defined, whereas gender is based on socially constructed features. They recognise that there are variations in how people experience gender based upon self-perception and expression, and how they behave.

They recognise that there are variations in how people experience gender based upon self-perception and expression, and how they behave.

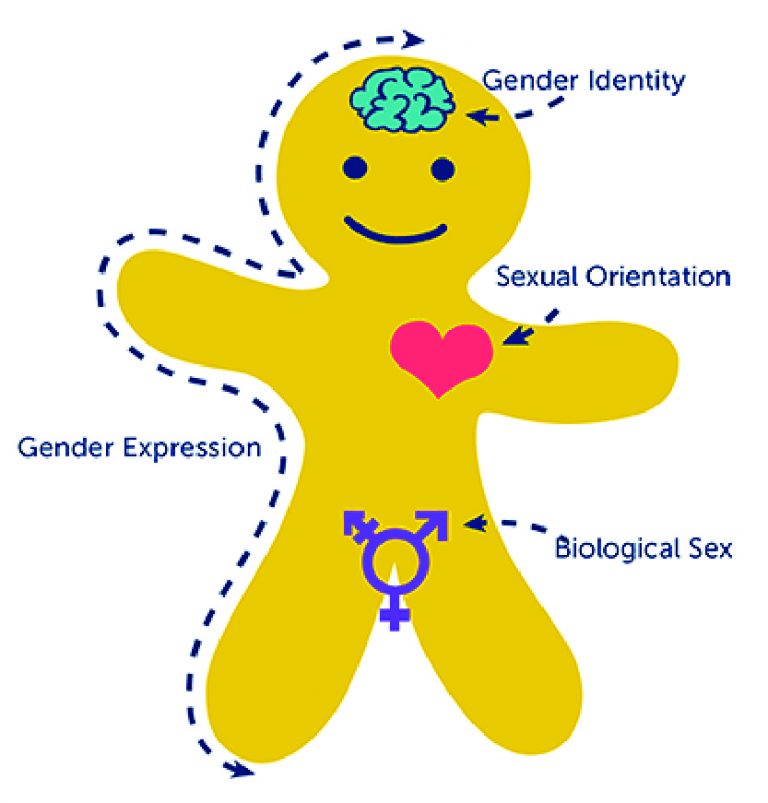

Essentially, nearly all people are born with physical characteristics that are labelled male or female. In 1964, Robert Stoller1 coined the term gender identity, which refers to an individual’s personal concept about their gender and how they feel inside. It is a deeply held internal sense of self and is typically self-identified. Gender identity differs from sexual identity and is not related to an individual’s sexual orientation (for more information, see the Terminology page of the Gender Identity Research and Education Society). As such, the gender category with which a person identifies may not match the sex they were assigned at birth.

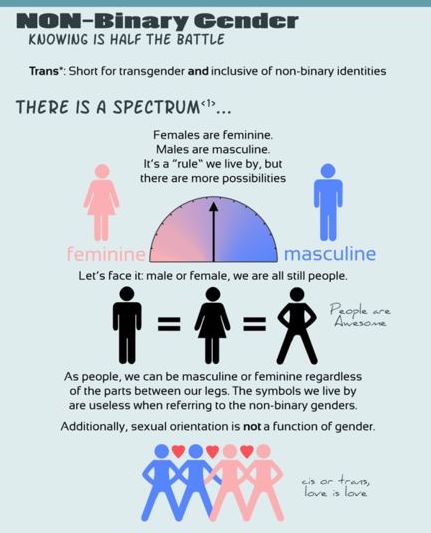

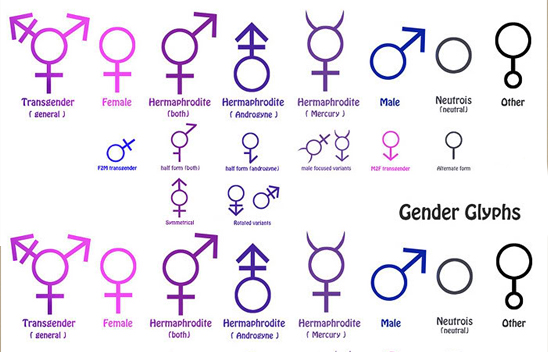

Gender is increasingly understood as not binary but on a spectrum. Growing numbers of people are identifying as somewhere along a continuum between man and woman, or as non-gendered (neither man nor woman) (see Gender Spectrum). Therefore, they often have their own words to describe themselves rather than using pre-defined categories of male and female (for more information, see Gender Identity Workshop, Summary of Discussions). While more people are identifying as non-binary, this is not a new concept and has existed for many years across different cultures around the world.

Therefore, they often have their own words to describe themselves rather than using pre-defined categories of male and female (for more information, see Gender Identity Workshop, Summary of Discussions). While more people are identifying as non-binary, this is not a new concept and has existed for many years across different cultures around the world.

Notes for: Definitions and differences

- Stoller, R. J. (1964). A contribution to the study of gender identity. The International Journal of Psychoanalysis, volume 45 issues 2 to 3, pages 220 to 226.

3. Variations in sex characteristics

Sex and gender are both generally referred to in two distinct categories: male and female or man and woman. However, there are naturally occurring instances of variations in sex characteristics (sometimes known as intersex). This is where people are born with hormones, chromosomes, anatomy or other characteristics that are neither exclusively male nor female. They are usually assigned a sex (male or female) by their family or doctor at birth as birth certificates require the sex of the child – either male or female. Individuals with variations in sex characteristics might identify as male, female, or intersex, and they may consider themselves to be a man, a woman, or to have a non-binary identity.

They are usually assigned a sex (male or female) by their family or doctor at birth as birth certificates require the sex of the child – either male or female. Individuals with variations in sex characteristics might identify as male, female, or intersex, and they may consider themselves to be a man, a woman, or to have a non-binary identity.

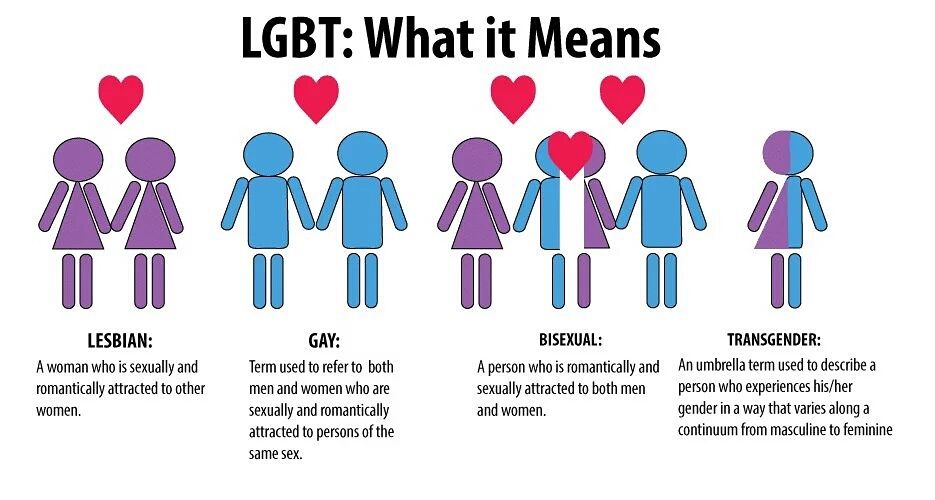

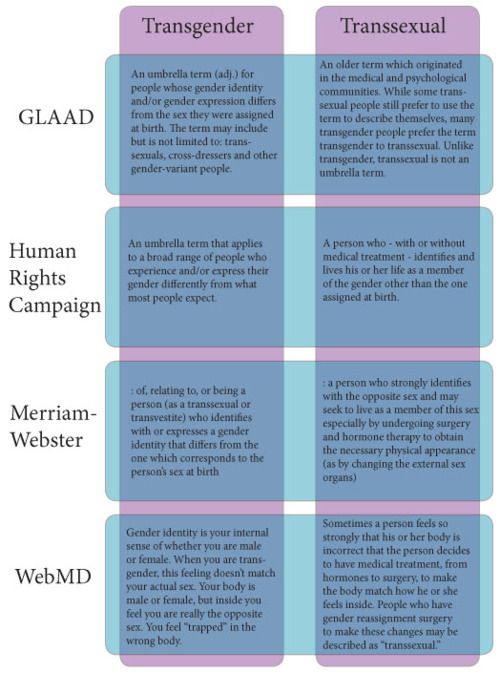

4. Transgender

Transgender or trans is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity is different from the sex assigned at birth. The Equality Act 2010 contains the protected characteristic of gender reassignment, which is defined as follows:

“A person has the protected characteristic of gender reassignment if the person is proposing to undergo, is undergoing or has undergone a process (or part of a process) for the purpose of reassigning the person's sex by changing physiological or other attributes of sex.”

This definition covers a wide range of people at varying stages of transition. A person does not need to have legally changed their gender to be included within the definition of the protected characteristic, nor do they need to have had any kind of surgery. The protection extends to anyone who has been treated less favourably because of gender reassignment, regardless of whether they have that characteristic or not.

A person does not need to have legally changed their gender to be included within the definition of the protected characteristic, nor do they need to have had any kind of surgery. The protection extends to anyone who has been treated less favourably because of gender reassignment, regardless of whether they have that characteristic or not.

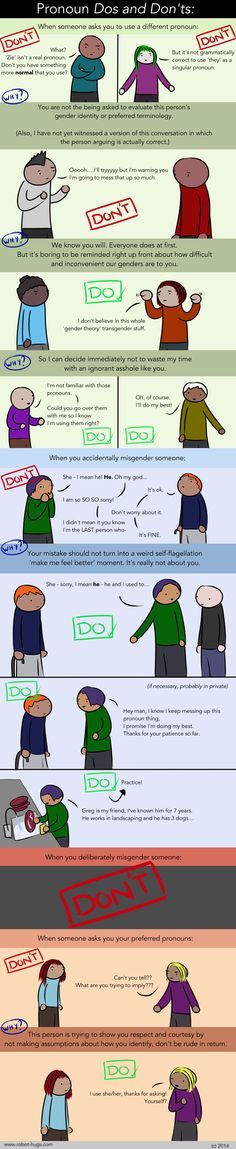

Many trans people go through a process called transitioning: changing how people see them and the way they look to align with their gender identity. It can involve changing characteristics, appearance, names and pronouns, and may include medical treatment, such as hormone therapy or surgery. Some people may not go on to have surgical procedures, but just have the “lived experience” in the gender they identify as. Definitions and terms are very personal; people who have transitioned do not necessarily identify their gender as trans. They may see their gender identity as a man or woman, or have different preferences and words to describe themselves (for more information, see Trans Data Position Paper).

Transitioning can also involve legally changing gender under the Gender Recognition Act 2004, which allows trans people to obtain a new birth certificate showing their new name and sex. It is important to note that the law in the UK treats the terms sex and gender as interchangeable. This is shown by the Gender Recognition Act allowing someone who is changing their gender to change the sex marker on their birth certificate.

The term trans is often grouped with sexual identity and orientation (for example, lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT)), however, it is independent of who you are attracted to and should be considered as separate.

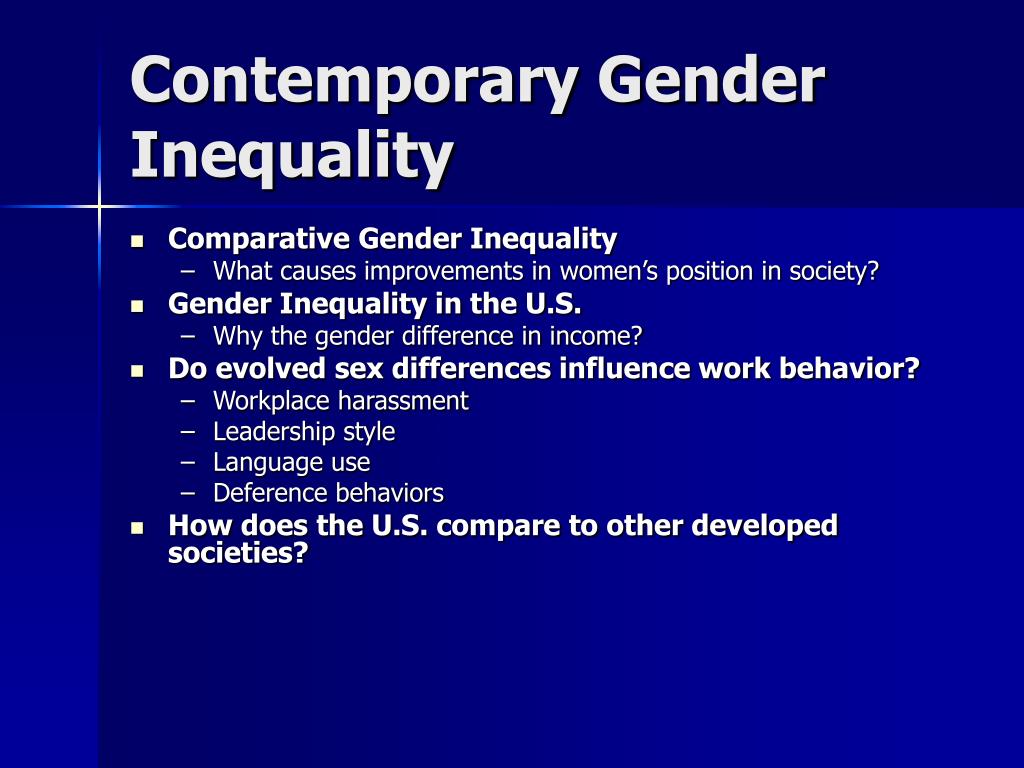

Back to table of contents5. Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs): gender and sex

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) are a universal set of goals, underpinned by targets and indicators. They seek to eradicate inequalities, ensuring that no one is left behind. Office for National Statistics (ONS) is the focal point of UK data for the global SDG indicators.

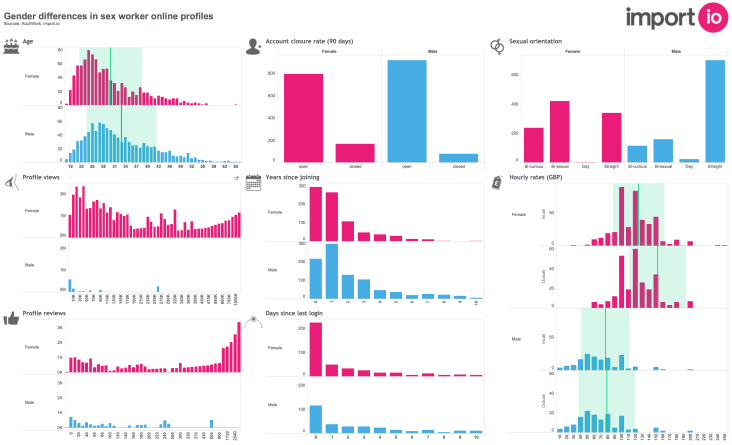

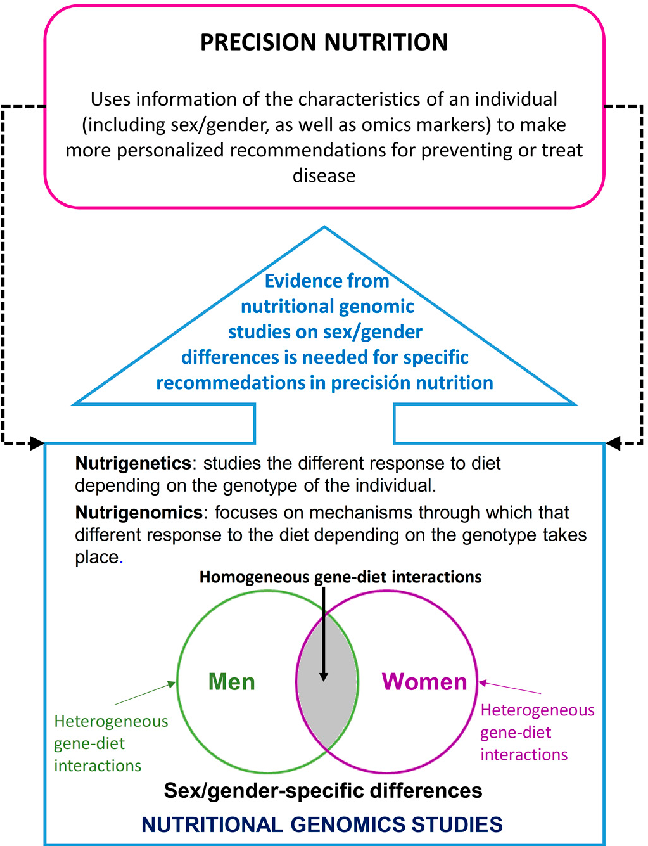

The data used to report on the indicators are often collected by other organisations (such as the NHS and government departments) and may not match SDG requirements. Most data collected captures those who are male or female only, and in some cases is labelled sex and some cases gender. There are very few organisations that collect data on gender identity. For more information, please see the Equalities data audit.

In the SDGs, the goals and targets tend to refer to gender, for example, “Goal 5: Gender equality” and “Target 4.a: Build and upgrade education facilities that are child, disability and gender sensitive and provide safe, non-violent, inclusive and effective learning environments for all”. However, indicators refer to sex, for example, “Indicator 5.b.1: Proportion of individuals who own a mobile telephone, by sex” and “Indicator 8.5.2: Unemployment rate, by sex, age and persons with disabilities”. This makes it complex in understanding what data are required and what information needs to be collected.

The main principle of the SDGs is to “leave no one behind”. To meet this, each of these indicators are to be broken down, where relevant, by eight characteristics required by the United Nations (UN). In paragraph 74.g of Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, they state the disaggregations are: income, sex, age, race, ethnicity, migration status, disability and geographic location, and other characteristics relevant in national contexts. However, in paragraph 17.18 they state gender instead of sex (the other disaggregations are the same).

The terms sex and gender appear to be used interchangeably. The “other characteristics” outlined in the Agenda relate to human rights and international laws, and include sexual orientation and gender identity. This suggests that measuring both sex and gender is important to ensure that no one is left behind. However, the Equality and Human Rights Commission indicates there may be a concern when it comes to reporting, especially when data are disaggregated. Even where data on gender identity are collected accurately, the amount of data may be so small that disclosure control means the data cannot be provided.

Even where data on gender identity are collected accurately, the amount of data may be so small that disclosure control means the data cannot be provided.

6. Data collection: benefits and complexities

Sex and gender data can be collected in various ways, as: biological sex, self-defined sex and gender identity. For many people, their sex and their gender are the same, so when asked about sex or gender they do not see a difference, and will just respond “male” or “female” as appropriate.

There are many positives in collecting gender identity data. The Equality and Human Rights Commission indicates that people welcome inclusion in surveys as it provides opportunities to express their opinions and to raise the profile of gender identity in society. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) gender identity workshop suggested that gender identity data would be useful to monitor discrimination and equality, and to inform policy. It would:

assist with allocation of funding and specialist services

provide education and awareness of gender identity

be beneficial to have official, reliable data about the size of the trans population

However, there are many different challenges in collecting and reporting gender information. Gender identity is subjective and often non-binary, therefore, data collection needs to be more detailed than simply man and woman. There are the issues of confidentiality, privacy, context, which information is appropriate to ask for and whether people would answer openly.

Gender identity is subjective and often non-binary, therefore, data collection needs to be more detailed than simply man and woman. There are the issues of confidentiality, privacy, context, which information is appropriate to ask for and whether people would answer openly.

It is important that respondents have the opportunity to identify their own gender and that they are comfortable in doing so. It was suggested in the gender identity workshop that people may not wish to divulge some information. This was more likely if they were transitioning or not “out” about their identity for fear of discrimination or harassment, or being unsure about what their information would be used for. Those who have transitioned may see this as part of their past and not want to disclose this, or have always felt they are the gender they identify with and therefore have not made a “transition”.

Under the Gender Recognition Act 2004, people who have transitioned are not required to (but can) reveal their gender history and Article 8 of the Human Rights Act 1998 says no one is required to reveal their gender identity. This could make the collection of accurate data difficult. Additionally, in some cases gender identity is not fixed but fluid, for example, with people who identify as non-binary. This could mean that you may not be reliably measuring something for all time.

This could make the collection of accurate data difficult. Additionally, in some cases gender identity is not fixed but fluid, for example, with people who identify as non-binary. This could mean that you may not be reliably measuring something for all time.

7. UK data collection

Office for National Statistics (ONS) does not currently collect data on gender identity in any social surveys and there are no harmonised questions across the Government Statistical Service (GSS). However, data collection methodology and question designs are being explored. The Census White Paper: Help Shape Our Future recommended that there will be a question on gender identity (while keeping the existing question on sex) for those aged 16 years and over for the 2021 Census for England and Wales. There is a dedicated web page outlining the work carried out and further work planned. The devolved authorities in Scotland and Northern Ireland are also considering the issue in the context of their data collection.

During the consultation for the 2021 Census for England and Wales and a gender identity workshop, it was confirmed that information about gender identity for all ages was needed to inform government policy and to allocate resources and service planning. With the 2010 Equality Act specifying gender reassignment as a protected characteristic and the government agreeing to assess how to measure the size of the UK trans population, there is increasing demand for data on gender identity (for more information, see Government Response to the Women and Equalities Committee Report on Transgender Equality). The Census White Paper: Help Shape Our Future outlines the latest position regarding gender identity questions in the 2021 Census for England and Wales.

Measurement and data on a person’s sex are still useful in certain areas, for example, healthcare and fertility. There are also some sex-specific laws, though these are changing. For example, pension provision is different for males and females, with males having a higher retirement age.

8. Summary

Sex and gender are different concepts that are often used interchangeably. The UK government refers to sex as being biologically defined, and gender as a social construct that is an internal sense of self, whether an individual sees themselves as a man or a woman, or another gender identity. They encompass many different identities and may be non-binary (that is, not a man or a woman).

Office for National Statistics (ONS) is researching how best to collect data on gender identity. The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) will look to report data disaggregated by gender identity and sex where possible as part of the principle of “leave no one behind”. All SDG data can be found on our reporting platform.

Back to table of contentsRelated publications

- Sustainable Development Goals data update, UK: December 2021

You might also be interested in:

- UK's Sustainable Development Goals reporting platform

- Links to all ONS Sustainable Development Goals publications

Meanings, definition, identity, and expression

People often use the terms “sex” and “gender” interchangeably, but this is incorrect. Sex and gender are different, and it is crucial to understand why.

Sex and gender are different, and it is crucial to understand why.

“Sex” refers to the physical differences between people who are male, female, or intersex. A person typically has their sex assigned at birth based on physiological characteristics, including their genitalia and chromosome composition. This assigned sex is called a person’s “natal sex.”

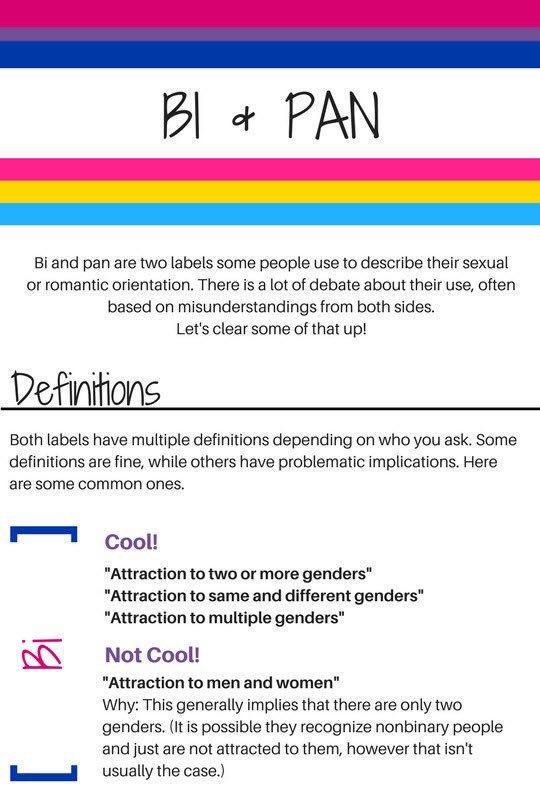

Gender, on the other hand, involves how a person identifies. Unlike natal sex, gender is not made up of binary forms. Instead, gender is a broad spectrum. A person may identify at any point within this spectrum or outside of it entirely.

People may identify with genders that are different from their natal sex or with none at all. These identities may include transgender, nonbinary, or gender-neutral. There are many other ways in which a person may define their own gender.

Gender also exists as social constructs — as gender “roles” or “norms.” These are defined as the socially constructed roles, behaviors, and attributes that a society considers appropriate for men and women.

Sex assignment typically happens at birth based on anatomical and physiological markers.

Male and female genitalia, both internal and external, are different, and male and female bodies have distinct hormonal and chromosomal makeups. Doctors use these factors to assign natal sex.

At birth, female-assigned people have higher levels of estrogen and progesterone, and while assigned males have higher levels of testosterone. Assigned females typically have two copies of the X chromosome, and assigned males have one X and one Y chromosome.

Society often sees maleness and femaleness as a biological binary. However, there are issues with this distinction. For instance, the chromosomal markers are not always clear-cut. Some male babies are born with two or three X chromosomes, just as some female babies are born with a Y chromosome.

Also, some babies are born with atypical genitalia due to a difference in sex development.

This type of difference was once called a “disorder of sex development,” but this term is problematic. In a 2015 survey, most respondents perceived the term negatively. A further review found that many people do not use it at all, and instead use “intersex.”

In a 2015 survey, most respondents perceived the term negatively. A further review found that many people do not use it at all, and instead use “intersex.”

Being intersex can mean different things. For example, a person might have genitals or internal sex organs that fall outside of typical binary categories. Or, a person might have a different combination of chromosomes. Some people do not know that they are intersex until they reach puberty.

Biologists have started to discuss the idea that sex may be a spectrum. This is not a new concept but one that has taken time to come into the public consciousness. For example, the idea of sex as a spectrum was discussed in a 1993 article published by the New York Academy of Sciences.

In the United States, gender has historically been defined as a binary. Many other cultures have long recognized third genders or do not recognize a binary that matches the American understanding.

In any case, the idea of gender as an either/or issue is incorrect.

Someone who identifies with the gender that they were assigned at birth is called “cisgender.”

Someone who is not cisgender and does not identify within the gender binary — of man or woman, boy or girl — may identify as nonbinary, genderfluid, or genderqueer, among other identities.

A person whose gender identity is different from their natal sex might identify as transgender.

A 2016 review confirms that gender exists on a broad spectrum — in contrast to the genetic definitions of sex.

A person may fully or partially identify with existing gender roles. They may not identify with any gender roles at all. People who do not identify with existing gender binaries may identify as nonbinary. This umbrella term covers a range of identities, including genderfluid, bigender, and gender-neutral.

Gender and society

Gender is also a social construct. As the World Health Organization (WHO) explains:

“Gender refers to the socially constructed characteristics of women and men, such as norms, roles, and relationships of and between groups of women and men. It varies from society to society and can be changed.”

It varies from society to society and can be changed.”

Gender roles in some societies are more rigid than in others. However, these are not always set in stone, and roles and stereotypes can shift over time. A 2018 meta-analysis of public opinion polls about gender stereotypes in the U.S. reflects this shift.

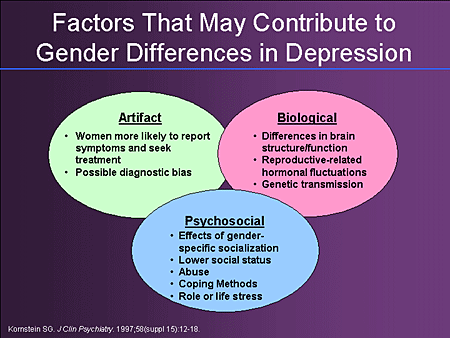

Gender and health

There are complex relationship between gender and both physical and mental health.

Health systems are not gender-neutral.

A WHO report highlights the ways that gender stereotypes and stigmas influence a person’s healthcare experience. Gender stereotypes can affect health coverage, pathways of care, and accountability and inclusivity within health systems throughout the world.

A review of first-hand case studies shows that by failing to address gender-based inequalities, health systems can reinforce prescriptive and exclusive gender binaries.

The researchers also emphasized that these inequalities in care can intersect with and amplify other social inequities.

The review concluded that health systems must be held accountable to address gender inequalities and restrictive gender norms.

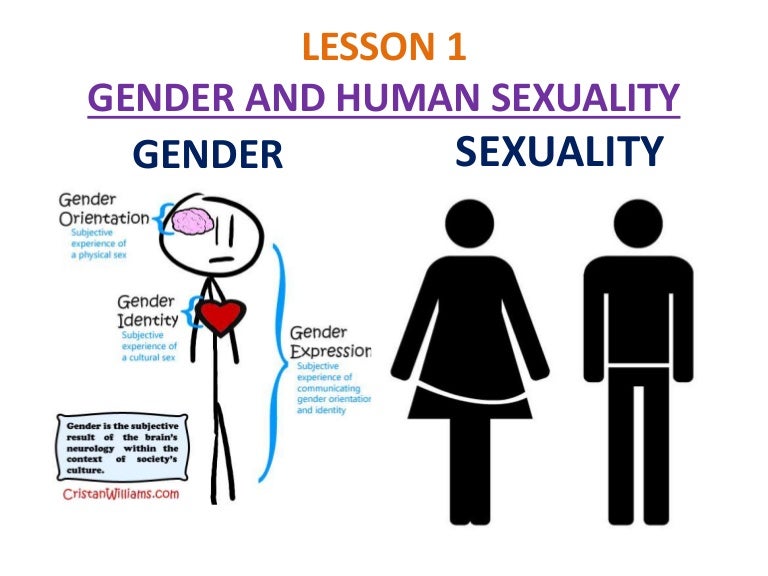

A person may identify and express their gender in different ways.

Gender identity is how a person feels internally, while their expression is how they present themselves to the outside world. For example, a person may identify as nonbinary but present as a man to the outside world.

GLAAD, formerly called the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation, describes gender identity as “one’s internal, personal sense” of belonging at some point on or off of the gender spectrum. The organization adds:

“Most people have a gender identity of man or woman (or boy or girl). For some people, their gender identity does not fit neatly into one of those two choices.”

GLAAD describes gender expression as: “External manifestations of gender, expressed through one’s name, pronouns, clothing, haircut, behavior, voice, or body characteristics. Society identifies these cues as masculine and feminine, although what is considered masculine and feminine changes over time and varies by culture.”

Society identifies these cues as masculine and feminine, although what is considered masculine and feminine changes over time and varies by culture.”

To discover more evidence-based information and resources for LGBTQIA+, visit our dedicated hub.

For centuries, many societies have enforced the notion that a person is either a man or woman based on their physical characteristics. This idea conflates sex and gender, which is incorrect. Sex and gender are not the same.

In general terms, sex refers to a person’s physical characteristics at birth, and gender encompasses a person’s identities, expressions, and societal roles.

A person may identify with a gender that is different from their natal sex or with no gender at all. The latter identity is often referred to as nonbinary, but this is an umbrella term that covers many identifications.

Sex and gender: how not to get confused in terms

November 20, 2020 Life

The shape of the genitals is determined by nature, and the duties of "real" women and men are determined by society.

You can listen to this article. If it's more convenient for you, turn on the podcast.

What is gender

This is a set of biological characteristics that help distinguish a male from a female. Not all of them are visible to the naked eye. For the most accurate identification, it is better to use a combination of factors:

- set of chromosomes - XY for men and XX for women;

- gonads - testicles in men, ovaries in women;

- internal genital organs - prostate and seminal vesicles in men, vagina, uterus and fallopian tubes in women;

- external genitalia - penis and scrotum in men, clitoris and labia in women;

- sex hormones - androgens predominate in men and estrogens in women;

- secondary sex characteristics - type of hair growth, development of mammary glands, distribution of body fat, and so on.

By themselves, these signs still do not guarantee anything, since, for example, a person with female genital organs may have a male set of chromosomes.

Biological sex is formed in several stages:

- In the sperm that fertilized the egg, there is either an X-chromosome or a Y-chromosome. In combination with the maternal X chromosome, she promises the appearance of a girl in the first case and a boy in the second.

- Each fetus has a pair of gonads that may develop into testicles or ovaries. Previously, it was believed that female gonads are formed by default, with the active participation of the Y chromosome - male. But now scientists are studying a special DSS gene, which is responsible for the formation of ovaries capable of producing full-fledged eggs. Failure at this stage leads to the fact that the gonads do not develop in accordance with the chromosome set.

- The intrauterine hormonal background of the fetus determines the shape of the internal and external genitalia. The delicate balance here can easily be disturbed, for example, if a pregnant woman takes certain hormonal drugs.

- In adolescence, hormones take over again and complete the process of biological sex formation. Obvious secondary sexual characteristics appear. Girls are waiting for menstruation, boys - ejaculation.

Accordingly, the biological sex is determined by nature, but the path of its formation is complex and thorny. And the set of characteristics in a person whom you define as a representative of one sex may correspond to another sex. And in the case of true hermaphroditism, people completely form a complete set of features characteristic of both sexes.

What is gender

It is a social concept referring to the characteristics and behaviors that a culture ascribes to genders. The simplest illustration is the set of qualities that comes to mind when the phrase "a real man should" or "a real woman should." For persuasiveness, this is usually served under the sauce of the biological nature of the gender role. But researchers deny this.

The process of gender socialization begins even before birth.

Parents often enthusiastically talk about the baby, that he still cannot sit, but reaches for the typewriter, because "a real man." But the child does not grow up in a social vacuum, and this affects his behavior.

The sex of the fetus can be determined by ultrasound. And from that moment on, parents begin to form expectations aimed at the baby. Purchase appropriate clothing and toys. Boys and girls of all ages are encouraged in different ways: for example, sports equipment and cars are given to the former, soft toys and dresses to the latter. Boys are more likely to be physically punished.

Gender stereotypes can be introduced even if parents generally do not support them.

The formation of gender attitudes does not necessarily occur through prohibitions, rather the way of thinking is important. For example, the encouragement “don't quit sports, girls can play basketball too” indicates the existence of generally accepted rules under which this is impossible.

Research shows that in recent years parents have become more flexible about gender stereotypes. However, the pursuit of equality in some areas does not compensate for traditional views in others. Conservatism is more often characteristic of fathers, and they take a tougher position in relation to their sons.

Gender role

Social expectations related to a person's gender are called gender role. In many cultures, there are quite rigid ideas about what is allowed to be done by men or women, and what is unacceptable. The social nature of these attitudes is indicated by the fact that prohibited actions are physically possible, they are simply condemned by society. In addition, the biological sex is not always decisive in determining the gender role.

Oathed virgins in Albania abandoned the traditional female role, wore male clothes, performed male duties and received the right to vote in the management of the community. Among the Indians in North America, both men and women could change gender, they were called reeds.

Expectations for members of the same sex may differ even within the same culture.

For example, aristocratic women had to faint from someone's heavy gaze, while their less noble "colleagues" were forced to carry heavy loads.

Gender identity

The gender of a person most often coincides with the biological sex. However, gender identity - self-identification as a man or a woman - is not given from birth. A person may feel uncomfortable within the gender status assigned to him (including due to the rigid expectations of society).

It is difficult to name the number of gender identification options. Facebook* now offers users in the UK to choose from 71 positions.

How to use these terms correctly

Despite the obvious differences, both terms - sex and gender - are still used extremely inaccurately, turning into synonyms. For example, parties common in the West, at which future parents find out the gender of the baby, are called gender reveal parties. Although, of course, we are talking about the shape of the genital organs that the doctor saw on the ultrasound, and not at all about the compliance of the infant's behavior with sociocultural requirements.

Although, of course, we are talking about the shape of the genital organs that the doctor saw on the ultrasound, and not at all about the compliance of the infant's behavior with sociocultural requirements.

It is important to remember that with different biological starts, men and women in large groups do not differ that much in terms of personality, cognitive abilities and leadership.

And individual differences, for example, between two men, can be much stronger than between a specific woman and a man. Therefore, it is time to stop assigning responsibilities according to the shape of the genitals and start demanding from each according to his abilities.

Read also 🧐

- “On my own and without panties”: how real men and women see ideal sex

- Why men take colds more severely than women

- How science explains homosexuality

*Activities of Meta Platforms Inc. and its social networks Facebook and Instagram are prohibited in the territory of the Russian Federation.

Sex and gender: how they differ and how not to confuse these concepts

Marie Claire: Explain what gender is and how gender differs from sex?

Elena Rozhdestvenskaya: Sex is what is recorded in documents at birth, anatomical and physiological characteristics. And gender is about social behavior in a particular society and in a particular era, it is a socially acceptable idea of masculinity and femininity. For example, if society operates with binary constructions, then gender ideology forces men and women to be as different from each other as possible. Certain social prescriptions arise, what a woman “should” do and what a man “should” be. In general, biological sex is distinguished (it can be decomposed into genetic, gonadal, gametic, hormonal and phenotypic sex), legal sex - that is, what is indicated in the documents, and finally that gender (and here we can already talk about gender identity), which man chooses for himself.

We used to live without gender, what happened?

The concept was introduced by the American psychiatrist Robert Stoller. In 1963, he delivered a report on gender identity, and in 1968 his book Sex and Gender was published.

In the wake of the explosion of women's emancipation and the sex revolution, the perception of the "female role" began to go beyond the prescribed kinder-kirche-küche.

Hence the story of the separation of biological data from social choice. So a new scientific concept has emerged - gender. In Russia, this term has been in use since the end of the 1980s.

But in India, from time immemorial, hijras have existed - the so-called "third sex"?

Yes, Hijras — as a rule, they are intersex (they used to be called “hermaphrodites”), men with defects in physiology, most often identifying themselves as women — have been officially recognized as the “third” gender in India for several years. Representatives of this sex now have passports, they can open a bank account. As you can see, in the end, even a traditional society like India found space for a non-binary system.

Representatives of this sex now have passports, they can open a bank account. As you can see, in the end, even a traditional society like India found space for a non-binary system.

How many types of gender are distinguished in sociology?

There are no number of varieties of genders. These are transgenders (or genderqueers - those whose gender identity does not match the biological sex), and transsexuals (those who are striving to make or have already made a gender transition - have surgically or hormonally changed their sex given from birth), and androgynes with bigenders (those who identify both feminine and masculine traits in themselves), and agenders (those who do not want to identify themselves with any gender at all), and pangenders (on the contrary, who feel signs of all gender identities in themselves), and gender fluids (those who tend to constantly change their identity).

It turns out, on which foot did you get up, what is your gender?

It turns out that yes. This is an attempt to get out of that very binary system. Not everyone fits in there.

This is an attempt to get out of that very binary system. Not everyone fits in there.

Navigating new genders can be extremely difficult. Therefore, many countries are moving towards gender-neutral language in documents and gender-neutral education.

You may have heard the story of Cory Doty, a Canadian, who identifies as a "non-binary transgender" and does not consider herself to be either a woman or a man. Corey is an activist in the Gender-Free ID Coalition, which is working to ensure that the gender of children until they reach adulthood is not mentioned at all in documents. Having given birth to a child at home (and not in a hospital where obstetricians immediately fix the gender), Corey insisted that the sex of the child was not indicated on the medical record, as well as on the birth certificate. She managed to get medical insurance, but she was denied a "sexless" birth certificate, and the activist sued. Although Canada has long adopted a law on gender-neutral language in document flow and even rewrote the anthem so that it does not sound only like an appeal to men.

Although Canada has long adopted a law on gender-neutral language in document flow and even rewrote the anthem so that it does not sound only like an appeal to men.

Why do so many kinds of genders emerge right now?

This is not entirely true. The desire for non-binary, gender fluidity and other queer manifestations have always existed with varying degrees of legitimacy. Today we just have more means and resources to discuss it on different media platforms. We have already talked about India. But "cross-sex" is practiced in other traditional societies too. For example, the bacha-posh tradition in Afghanistan: girls from an early age were brought up as boys, called by a man's name, cut their hair short, were allowed to get an education, practice martial arts, and go shopping on their own. Later, however, they were married off - reincarnation back into a woman and the loss of freedom was not easy for many.

Where can all this lead us?

Now the search for gender identity is the subject of experiments, self-determination and self-affirmation. But any identity somehow strives to be supported, heard and accepted in society. But in a neoconservative society there is no wide understanding and accepting community. There are chances of being accepted only among those who are close in experience and ideology, that is, within the framework of their scene (now this concept is more often used - from the English scene, and not the concept of subculture, as it was in 1980s of the last century). Therefore, the fluid gender identity goes “into the closet” a little - for the time being, it is very difficult for those who choose this path to explain to society who they are.

But any identity somehow strives to be supported, heard and accepted in society. But in a neoconservative society there is no wide understanding and accepting community. There are chances of being accepted only among those who are close in experience and ideology, that is, within the framework of their scene (now this concept is more often used - from the English scene, and not the concept of subculture, as it was in 1980s of the last century). Therefore, the fluid gender identity goes “into the closet” a little - for the time being, it is very difficult for those who choose this path to explain to society who they are.

Should we put aside gender doubts?

There is an opinion that the set of gender roles is outdated. Now we are forced to create new scenarios, to speak out new needs. But can we negotiate? Do we even have a language for negotiation? And do people with a fluid gender identity understand what they want?

Countries that recognize the rights of citizens to sexual indeterminacy

In Germany back in 2013 they allowed the “gender” column to be left temporarily blank in birth certificates, and a few years ago the government approved a bill where a new paragraph is attached to the birth certificate under the name "other" or "various".

In 2014, the Supreme Court of Australia ruled that there was a third, "indeterminate" gender in the country.

In New Zealand you can register your gender as indeterminate, intersex, non-specific.

In 2007, the Supreme Court of Nepal coined the term "third gender", and since 2015, Nepalese can indicate the third gender on their identity cards.

In Bangladesh passed a law in 2013 that introduced the Hijra category in passports and other identification documents.

In India in 2014, the Supreme Court finally equalized the "third sex" in rights with other citizens.

In Austria in 2018, the Constitutional Court ruled that people should be able to register not only as a man or a woman.

Relaxation of gender identity norms is also discussed in Malta , in some states of America , and in Indonesia as many as 5 different genders are recognized, including "metagender" and "bissu" - the sexual ambiguity that healers most often identify themselves with and shamans.