Schizophrenia and promiscuity

Risky sexual behaviors of schizophrenic patients: a single center study in Ethiopia, 2018 | BMC Research Notes

- Research note

- Open Access

- Published:

- Biruk Negash1,

- Bethlehem Asmamewu2 &

- Wondale Getinet Alemu3

BMC Research Notes volume 12, Article number: 635 (2019) Cite this article

-

10k Accesses

-

4 Citations

-

1 Altmetric

-

Metrics details

Abstract

Objective

Identify factors related to risky sexual behavior can facilitate health care providers to approach programs that improve quality of services provided to the patient service. The aim of study to assess the prevalence of risky sexual behaviors and associated factors among schizophrenia patient at Amanuel Mental specialized hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, 2019.

Result

A total of four hundred twenty-nine participants were interviewed with a response rate of 97.05%. The prevalence of risky sexual behavior was 39.4% (95% CI 34.3, 43.6). In the multivariate logistic regression, being male sex (AOR = 3.78 (1.94, 7.38)), patients in age group between 18 and 24 (AOR = 4.85 (1.73, 13.6)), current use of alcohol (AOR = 1.86 (1.049, 3.32)), place of residence (AOR = 6.22 (2.98, 12.98)), positive symptom (AOR = 3.01 (1.55, 5.84)) were associated with risky sexual behavior.

Introduction

Risky sexual behavior is the description of the activity that increases the probability of a person engaging in sexual activity with another person infected with a sexually transmitted infections, will be infected or become pregnant, or make a partner pregnant. It involves negative consequence including unintended pregnancy and HIV/AIDS or other transmitted diseases, gained due to several sexual partners, inconsistent use of condom and having sexual intercourses under influence of alcohol [1].

It involves negative consequence including unintended pregnancy and HIV/AIDS or other transmitted diseases, gained due to several sexual partners, inconsistent use of condom and having sexual intercourses under influence of alcohol [1].

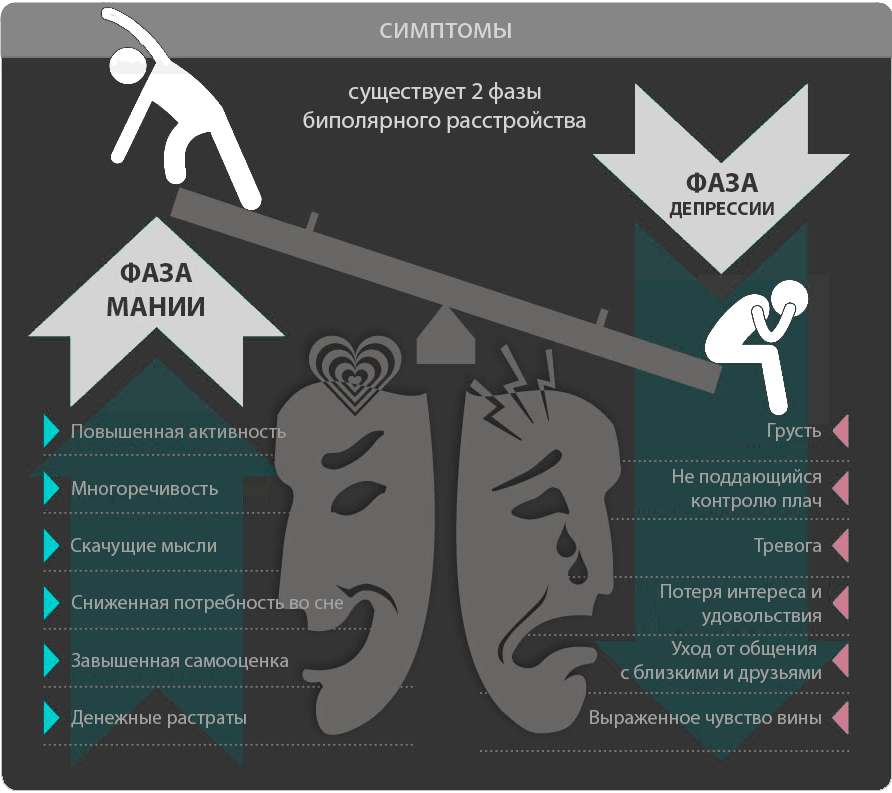

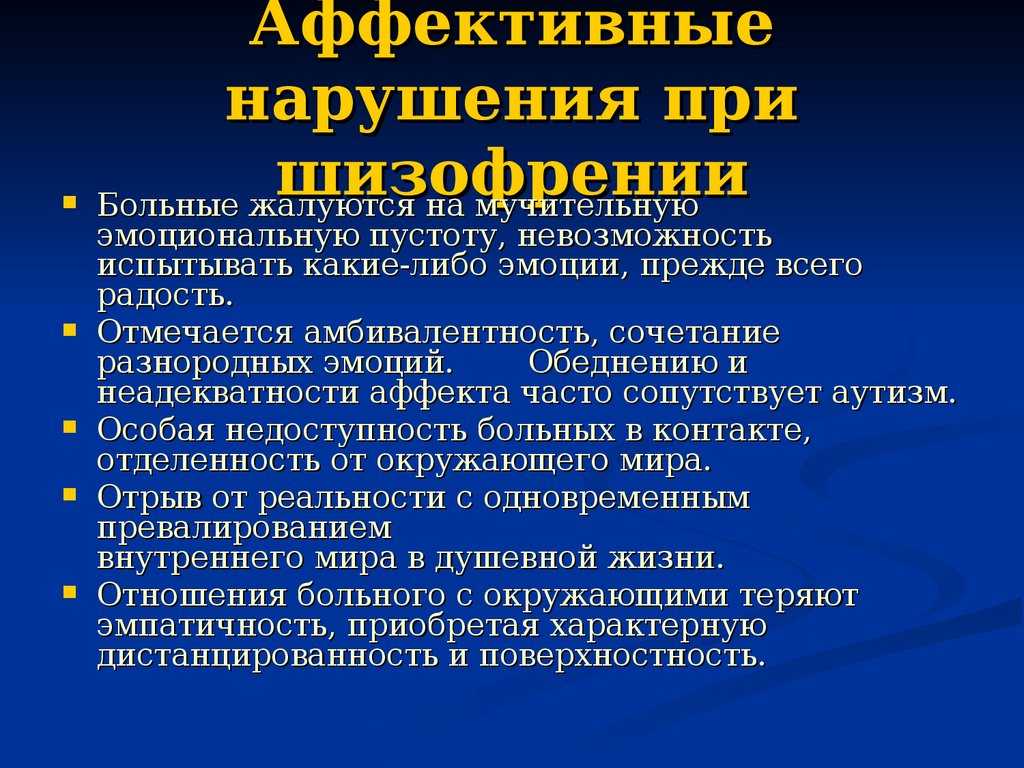

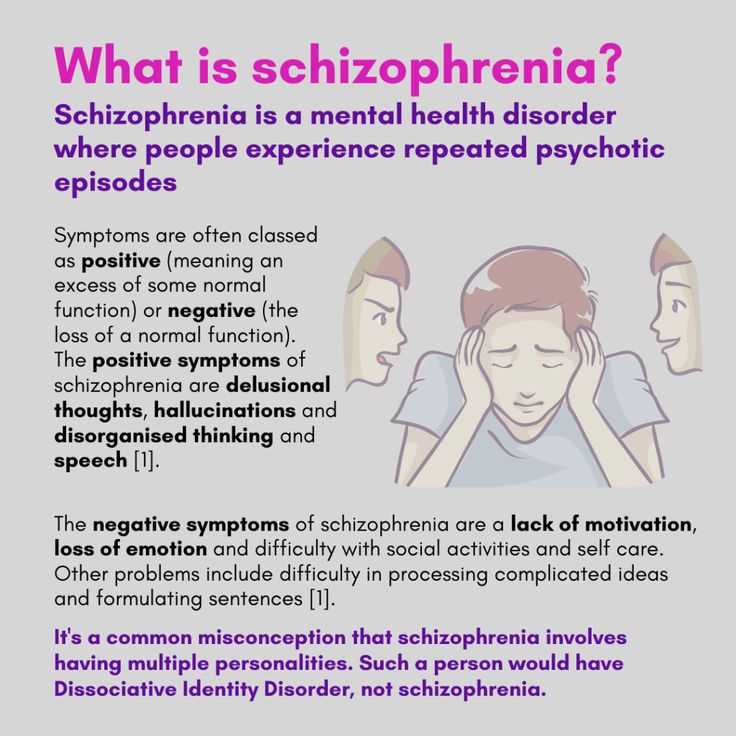

People with schizophrenia are susceptible to risky sexual behavior [2]. Being sexually active is less common among them; those who are active are more likely to engage in risky sexual behavior [3]. Persons may experience “negative” symptoms which include loss of a sense of pleasure, social withdrawal, poverty of thoughts and speech, and flattening of affect and, medication side effects disrupt patient’s ability to perform sexually, however, these problems do not eliminate the desire for sexual contact or render the patient inactive [4, 5].

Several studies conducted among adults showed that there was an increasing risky sexual behavior people with schizophrenia at global disease burden, schizophrenia spectrum was two times more likely to engage in risky sexual intercourse and 2. 3 times to develop transmitted diseases [6].

3 times to develop transmitted diseases [6].

Among studies done on New York state 93% of them use condoms, 62% had multiple sexual partners, 50% took part in sex exchange, 45% of them used drugs or alcohol during sex [7], and other studies in New York, having multiple sexual partners were three times as likely among patients with greater positive symptom [7]. In the UK condom use was very inconsistent (around 8%), drug or alcohol use during sexual intercourse was common, and sexual exchange (for money, drugs or other goods), around 12% of those who were active had sex with a partner who was a known drug user [2]. In Nigeria 38.2% reported two or more sexual partners, 5.9% reported sex trading and 80.8% inconsistent use of condom [8], community-based cross-sectional study conducted in New York 62% had multiple sexual partners, 50% took part in sex exchange, 45% of the active patients used drugs or alcohol during sex, which may affect risk-taking behavior [5].

Cross-sectional study conducted on Italy stated that 83% of schizophrenia engage in high-risk sexual activity at which (58% had multiple sexual partners, 25% of them had almost never used a condom) [9]. A case–control study conducted on Turkey of risky sexual behaviors of among diagnosis of schizophrenia was 26%, such as sex with multiple sexual partners 6%, sexual intercourse with different partners 10%, sexual activity under influence of alcohol or other drugs 10% in participants [10] in India, 59% of had a history of risky sexual behavior [11], Nigeria (48%), of the prevalence of risky sexual behavior [8].

A case–control study conducted on Turkey of risky sexual behaviors of among diagnosis of schizophrenia was 26%, such as sex with multiple sexual partners 6%, sexual intercourse with different partners 10%, sexual activity under influence of alcohol or other drugs 10% in participants [10] in India, 59% of had a history of risky sexual behavior [11], Nigeria (48%), of the prevalence of risky sexual behavior [8].

The estimated incidence of HIV/AIDS among people ranged from 4 to 23% [12], and 21% people with schizophrenia were following ART treatment [13].

So, determining the prevalence of risky sexual behavior and associated factors among schizophrenia patient is important for early intervention and the reduction of the burden of risky sexual behavior and to improve the quality of life of schizophrenia patients.

Main text

Study setting and population

An institution based cross-sectional study was conducted from May to June 2018 at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Amanuel Mental Specialized hospital is a governmental hospital in Addis Ababa, which is found in Addis ketema sub city, the capital city of Ethiopia.

Amanuel Mental Specialized hospital is a governmental hospital in Addis Ababa, which is found in Addis ketema sub city, the capital city of Ethiopia.

The study included participants aged 18 years and above during data collection in the area. There were a total of 3536 people with schizophrenia spectrum disorder receiving follow-up care at the outpatient department of Amanuel Mental Health Specialized Hospital. Individuals seriously ill and unable to communicate were excluded. We determined the sample size by using the single population proportion formula with the assumption of 50% prevalence of risky sexual behavior, 95% CI (alpha = 0.05), 1.96 standard normal distribution and a 10% non-response rate. Accordingly, a representative sample was calculated to be four hundred twenty-three. After considering non response rate the total sample size was four hundred forty-two. We selected the study participants using systematic random sampling technique.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected by face to face interviews, using a semi structured questionnaire by means of the Amharic version of the tool for a month. The questionnaire was designed in English and translated to Amharic and back to English to maintain consistency. Data collectors were trained on how to interview participants and explain unclear question and the purpose of the study. Furthermore, they were made aware about ethical principles, such as confidentiality/anonymity/data management and securing respondents informed consent for participation. Risky sexual behavior was measured using the adopted from behavioral surveillance survey and published articles which changed to apply for the local context. It was validated in Ethiopian demographic and health survey for assessment of risky sexual behavior among HIV/AIDS patients. Tools which consist of risky sexual behaviors (such as early sexual initiation, multiple sexual partners, unprotected sex, the use of substances and involved in sex [14, 15]). Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) (a 30-item semi-structured interview) to assess positive, negative and global psychopathology symptoms.

The questionnaire was designed in English and translated to Amharic and back to English to maintain consistency. Data collectors were trained on how to interview participants and explain unclear question and the purpose of the study. Furthermore, they were made aware about ethical principles, such as confidentiality/anonymity/data management and securing respondents informed consent for participation. Risky sexual behavior was measured using the adopted from behavioral surveillance survey and published articles which changed to apply for the local context. It was validated in Ethiopian demographic and health survey for assessment of risky sexual behavior among HIV/AIDS patients. Tools which consist of risky sexual behaviors (such as early sexual initiation, multiple sexual partners, unprotected sex, the use of substances and involved in sex [14, 15]). Positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) (a 30-item semi-structured interview) to assess positive, negative and global psychopathology symptoms. Before starting actual survey, the questionnaire was pre-tested on 5% of sample size at a St. Paul hospital. According to pretest Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.67. Two days training was given for data collectors and supervisor on the content of the questionnaires. All collected data were checked for completeness, consistency and recheck before processing and analysis of the data. Then, entered into EPINFO 3.5.1 statistical software and exported to SPSS windows version-20 for analysis. We computed descriptive, bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to see the frequency distribution and to test the association between independent and dependent variables, respectively. Factors associated with risky sexual behavior were selected during the bivariate analysis with a p-value < 0.2 for the analysis, variables with p-value less than 0.05 at 95% confidence interval with adjusted odds ratio were considered as statistically significant.

Before starting actual survey, the questionnaire was pre-tested on 5% of sample size at a St. Paul hospital. According to pretest Cronbach’s Alpha value was 0.67. Two days training was given for data collectors and supervisor on the content of the questionnaires. All collected data were checked for completeness, consistency and recheck before processing and analysis of the data. Then, entered into EPINFO 3.5.1 statistical software and exported to SPSS windows version-20 for analysis. We computed descriptive, bivariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses to see the frequency distribution and to test the association between independent and dependent variables, respectively. Factors associated with risky sexual behavior were selected during the bivariate analysis with a p-value < 0.2 for the analysis, variables with p-value less than 0.05 at 95% confidence interval with adjusted odds ratio were considered as statistically significant.

Results

Socio demographic characteristics of participants

A total of 442 participants took part with a response rate of 97% (429). The mean age of respondents was 32.8 years (± SD = 8.9) Out of 429 respondents, 253 (59%) were males, 190 (44.3%) were orthodox religion followers, 234 (54.5%) were singles, 221 (51.5%) had secondary education, 213 (49.7%) were unemployed, 275 (64.1%) lived in towns. From the total 298 (69.5%) were developed schizophrenia before the age of 25 years, 170 (39.6%) of them had the illness for 5–10 years, about 173 (40.3%) were on treatment for 5–10 years, 280 (65.1%) had less than two episodes, 277 (64.6%) had history of hospitalization (Table 1).

The mean age of respondents was 32.8 years (± SD = 8.9) Out of 429 respondents, 253 (59%) were males, 190 (44.3%) were orthodox religion followers, 234 (54.5%) were singles, 221 (51.5%) had secondary education, 213 (49.7%) were unemployed, 275 (64.1%) lived in towns. From the total 298 (69.5%) were developed schizophrenia before the age of 25 years, 170 (39.6%) of them had the illness for 5–10 years, about 173 (40.3%) were on treatment for 5–10 years, 280 (65.1%) had less than two episodes, 277 (64.6%) had history of hospitalization (Table 1).

Full size table

Prevalence of risky sexual behavior among schizophrenic patients

The overall prevalence of risky sexual behavior was 39.4%, 95% CI (34.3, 43.6). Among all 8.4% had sexual intercourse with two or more sexual partners, 10.5% had unprotected sexual intercourse, 11. 2% had sexual intercourse after alcohol consumption and; 12.1% had exchanged money for sex.

2% had sexual intercourse after alcohol consumption and; 12.1% had exchanged money for sex.

Factors associated with risky sexual behavior

To examine the association of independent variables with risky sexual behavior, bivariate and multivariate binary logistic regression analyses were done.

In the bivariate analyses, factors including, being male sex, being in age category of 18–24, age onset of illness, homelessness, urban residence, current use of tobacco, positive symptom and current use of alcohol were significantly associated with risky sexual behavior at a p-value less than 0.2. These factors were entered into the multivariable logistic regression model to control confounding effects. The result of the multivariate analysis showed that being male sex, being in age category of 18–24, urban residence, Current alcohol use, Positive symptom were significantly associated with risky sexual behavior at a p-value less than 0.05. Male sex was 3.78 times more likely to develop risky sexual behavior compared with female sex (AOR = 3. 78, 95% CI 1.94, 7.38). The odds of developing risky sexual behavior were 4.85 times higher among age group 18–24 compared with the ones greater than/equal to 45 years (AOR = 4.85, 95% CI 1.73, 13.6). The odds of developing risky sexual behavior were 6.22 times higher among participants from urban residence compared with those who are from rural (AOR = 6.22, 95% CI 2.98, 12.98). The likelihood of developing risky sexual behavior was 1.86 times higher among respondents who are current alcohol users compared with those who are not alcohol users (AOR = 1.86, 95% CI 1.049, 3.32). The odds of developing risky sexual behavior were 3 times higher among respondents who have positive symptoms than those who hadn’t positive symptom (AOR = 3, 95% CI 1.55, 5.84) (Table 2).

78, 95% CI 1.94, 7.38). The odds of developing risky sexual behavior were 4.85 times higher among age group 18–24 compared with the ones greater than/equal to 45 years (AOR = 4.85, 95% CI 1.73, 13.6). The odds of developing risky sexual behavior were 6.22 times higher among participants from urban residence compared with those who are from rural (AOR = 6.22, 95% CI 2.98, 12.98). The likelihood of developing risky sexual behavior was 1.86 times higher among respondents who are current alcohol users compared with those who are not alcohol users (AOR = 1.86, 95% CI 1.049, 3.32). The odds of developing risky sexual behavior were 3 times higher among respondents who have positive symptoms than those who hadn’t positive symptom (AOR = 3, 95% CI 1.55, 5.84) (Table 2).

Full size table

Discussion

Risky sexual behavior is the most common behavioral disorder and public health important in the global level. The study found that a number of participants met criteria for risky sexual behavior. The finding of this study revealed that prevalence of risky sexual behavior among schizophrenia patients was 39.4%. Almost thirty-four percent of the male and five percent of female schizophrenia have risky sexual behavior. This study was higher than studies conducted in Turkey which was 26% [9], south India 21% [16] and USA 23% [10]. The possible reason for this variation might be difference in method they used for data collection. Conversely our result is lower than 89% noted in New York [10] and a study conducted in India 51% [17]. The possible reason for the difference might be difference in study design, sample size, data collection tool and cultural difference in study population.

The study found that a number of participants met criteria for risky sexual behavior. The finding of this study revealed that prevalence of risky sexual behavior among schizophrenia patients was 39.4%. Almost thirty-four percent of the male and five percent of female schizophrenia have risky sexual behavior. This study was higher than studies conducted in Turkey which was 26% [9], south India 21% [16] and USA 23% [10]. The possible reason for this variation might be difference in method they used for data collection. Conversely our result is lower than 89% noted in New York [10] and a study conducted in India 51% [17]. The possible reason for the difference might be difference in study design, sample size, data collection tool and cultural difference in study population.

In this study, being male sex the odds of having risky sexual behavior is four times higher as compared to females. This finding is similar with other studies [18,19,20,21]. The possible reasons could be having sexual intercourse with multiple non-marital, non-cohabiting sexual partners and not using condoms common in males, substance use were more used among males than females, the third explanation might be due to differences on social dynamics given to sexual behaviors of both gender and nature of illness (schizophrenia) among males.

The odd of having risky sexual behavior was five times higher among ages of 18–24 clients with the rest age group. Possible reasons could be use of substance, psychiatric disorders and risky sexual behaviors both peak in young adulthood and severity of illness have poor prognosis among youth, have a lot of trauma in this age group [22], and low self-esteem and high internal stigma in younger adults with mental illness may cause a failure to provide healthier romantic relationship and associated with failure to advocate for safer sex and their knowledge level about risk sexual behavior and its consequence is unsatisfactory [23,24,25].

The odd of having risky sexual behavior was two times higher among clients with current alcohol use than not use. This finding is congruent with other studies [8, 26, 27]. Possible explanations were psychoactive substance use and abuse have consistently been found to be associated with sexual risk behavior, effect of alcohol could decrease motivation or ability to have protected sexual intercourse and power to influence an individual’s decision making due to these reasons they could involve in risky sexual behaviors, weighing no damage following the behavior, there is a causal relationship between alcohol and the theoretical determinants of sexual risk behavior, alcohol and risky sexual behavior may be associated at the global level because when people plan to engage in risk behavior they may drink or use drugs to decrease cognitive disagreement about their behavior.

Regarding place of residence; the odds of having risky sexual behavior was seven times higher among clients live in urban than living in rural area. It might be due to prostitution, homelessness more common in urban than rural area like other studies [28]. Participants with severe positive symptoms were three times more likely to engage in risky sexual behaviors compared to those without severe positive symptom. This finding is similar with a previous study [7]. A possible explanation is patients who have positive symptoms are self-destructive, having rational thinking loss, maybe less likely to inhibit their sexual impulses, so they do not care about life itself, there is no reason to care whether they acquire an infection or not.

Conclusion

The prevalence of risky sexual behavior was found to be high. Emphasis should be given for clients who are male, those found at a young age, who are current alcohol user, who live in urban and those present with severe positive symptom. Interventions should contain widespread sexual and reproductive health awareness on issues such as sexual education, safe sex and sexually transmitted infections for clients who are schizophrenic.

Limitations of the study

Cross-sectional study does not always confirm a cause-and-effect relationship.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data are within the paper.

Abbreviations

- OR:

-

odd ratio

- COR:

-

crude odd ratio

- AOR:

-

adjusted odd ratio

- PANNS:

-

positive and negative syndrome scale

References

Timiun GA. Sexual webs model for the explanation of unsafe sexual behavior: knitting all the perspectives of unsafe sexual behavior.

Int J Hum Soc Sci. 2011;1:17.

Google Scholar

Gray R, Brewin E, Noak J, Wyke-Joseph J, Sonik B. A review of the literature on HIV infection and schizophrenia: implications for research, policy and clinical practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2002;9(4):405–9.

Article Google Scholar

Cournos F, McKinnon K, Sullivan G. Schizophrenia and comorbid human immunodeficiency virus or hepatitis C virus. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:27.

PubMed Google Scholar

Talreja BT, Shah S, Kataria L. Cognitive function in schizophrenia and its association with socio-demographic factors. Ind Psychiatry J. 2013;22(1):47.

Article Google Scholar

Gottesman II, Groome CS. HIV/AIDS risks as a consequence of schizophrenia.

Schizophr Bull. 1997;23(4):675–84.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Cournos F, Coomaraswamy S, Guido JR, Meyer-Bahlburg HF. Sexual activity and risk of HIV infection among patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.151.2.228.

Article Google Scholar

McKinnon K, Cournos F, Sugden R, Guido JR, Herman R. The relative contributions of psychiatric symptoms and AIDS knowledge to HIV risk behaviors among people with severe mental illness. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(11):506–13.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Abayomi O, Adelufosi A, Adebayo P, Ighoroje M, Ajogbon D, Ogunwale A. HIV risk behavior in persons with severe mental disorders in a psychiatric hospital in Ogun, Nigeria. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013;3(3):380–4.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Grassi L, Pavanati M, Cardelli R, Ferri S, Peron L. HIV-risk behaviour and knowledge about HIV/AIDS among patients with schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1999;29(1):171–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Nesrin T, Ozlem T, Nesrin K, Kadriye P, Evrim O, Nihat AL. High risk behaviours for sexullay transmitted diseases in female psychiatric outpatients in Turkey. Indian J Prev Soc Med. 2006;27:17–21.

Google Scholar

Chopra MP, Eranti SSV, Chandra PS. HIV-related risk behaviors among psychiatric inpatients in India. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(6):823–5.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Lambert TJ, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C. Medical comorbidity in schizophrenia.

Med J Aust. 2003;178(9):S67.

PubMed Google Scholar

Ibrahim N. Assessment of HIV treatment outcome among mentally disordered patients at Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital; 2015.

Derbie A, Assefa M, Mekonnen D, Biadglegne F. Risky sexual behaviour and associated factors among students of Debre Tabor University, Northwest Ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2016;30(1):11–8.

Google Scholar

Negeri EL. Assessment of risky sexual behaviors and risk perception among youths in Western Ethiopia: the influences of family and peers: a comparative cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2014;14(1):301.

Article Google Scholar

Chandra PS, Carey MP, Carey KB, Prasada Rao P, Jairam K, Thomas T. HIV risk behaviour among psychiatric inpatients: results from a hospital-wide screening study in southern India.

Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14(8):532–8.

Article Google Scholar

Guimarães MDC, McKinnon K, Campos LN, Melo APS, Wainberg M. HIV risk behavior of psychiatric patients with mental illness: a sample of Brazilian patients. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2010;32(4):349–50.

Google Scholar

Alamrew Z, Bedimo M, Azage M. Risky sexual practices and associated factors for HIV/AIDS infection among private college students in Bahir Dar City, Northwest Ethiopia. ISRN Public Health. 2013. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/763051.

Article Google Scholar

Bakare MO, Agomoh AO, Ebigbo PO, Onyeama GM, Eaton J, Onwukwe JU, et al. Co-morbid disorders and sexual risk behavior in Nigerian adolescents with bipolar disorder. Int Arch Med. 2009;2(1):16.

Article Google Scholar

Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Gleason JR, Gordon CM, Brewer KK. HIV-risk behavior among outpatients at a state psychiatric hospital: prevalence and risk modeling. Behav Ther. 1999;30(3):389–406.

Article Google Scholar

Dutra MRT, Campos LN, Guimarães MDC. Sexually transmitted diseases among psychiatric patients in Brazil. Braz J Infect Dis. 2014;18(1):13–20.

Article Google Scholar

Ramrakha S, Caspi A, Dickson N, Moffitt TE, Paul C. Psychiatric disorders and risky sexual behaviour in young adulthood: cross sectional study in birth cohort. BMJ. 2000;321(7256):263–6.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Haggerty RJ, Mrazek PJ. Reducing risks for mental disorders: Frontiers for preventive intervention research. Washington, D.C: National Academies Press; 1994.

Google Scholar

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Trends in sexual risk behaviors among high school students–United States, 1991–1997. MMWR. 1998;47(36):749.

Google Scholar

Gowen L, Aue N. Sexual health disparities among disenfranchised youth. Portland, Oregon Health Authority Public Health Division and Research and Training Center for Pathways to Positive Futures at Portland State University Ioregon. Youth sexual health report. 2011.

Carey MP, Carey KB, Maisto SA, Schroder KE, Vanable PA, Gordon CM. HIV risk behavior among psychiatric outpatients: association with psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder, and gender. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(4):289.

Article Google Scholar

Calhoun KS, Mouilso ER, Edwards KM.

Sexual assault among college students. Sex in college: the things they don’t write home about. Santa Barbara: Praeger; 2012. p. 263–88.

Google Scholar

Brunette MF, Rosenberg SD, Goodman LA, Mueser KT, Osher FC, Vidaver R, et al. HIV risk factors among people with severe mental illness in urban and rural areas. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(4):556–8.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

First, Authors’ gratitude goes to the University of Gondar and Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Research and Community Service Core Process for financial support. Second, we would like to thank the study subjects for their willingness to take part in the study. Finally, our heartfelt tank goes to the supervisors and data collectors for their admirable endeavor during the data collection.

Funding

No funding sources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Ministry of Health, Geferessa Rehabilitation Center, Addis Ababa Health Bureau, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Biruk Negash

Ministry of Health, Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital, Addis Ababa Health Bureau, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

Bethlehem Asmamewu

Department of Psychiatry College of Medicine and Health Science, University of Gondar, Gondar, Ethiopia

Wondale Getinet Alemu

Authors

- Biruk Negash

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Bethlehem Asmamewu

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

- Wondale Getinet Alemu

View author publications

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

BN: carried out the manuscript from its conception, analysis, and interpretation of data and drafted the manuscript. WG: took part in the data analysis and interpretation of data, commented and drafted the manuscript for publication. BA: took part in data analysis and review of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Wondale Getinet Alemu.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The ethical review board of the University of Gondar and Amanuel Mental Specialized Hospital approved the study. A formal letter of permission got and submitted to the respective outpatient department. We inform about the study to the participants and family members even though our study subjects have full insight about their illness. We sought written informed consent for each participant who was voluntary. Only anonymous data collected in private rooms.

Consent for publishing

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

About this article

what determines sexual interest and confidence?

When Noah was doing the guest-list for his ark, everyone got a plus one. Was he concerned that the more reserved animals wouldn’t mingle well? Did he think that everyone would be more relaxed and have a better time if there was someone they knew there? Well, no. As anyone who’s familiar with the story knows, Noah got everyone to bring a partner because if the end of the world was coming, he wanted them to be able to procreate and ensure the survival of their species. Admittedly there were some flaws in his plan (increased risk for genetic disease for one), but the basic idea that sex is a fundamental part of existence was there.

Now, the animals on the arc were there to get a job done. These days however, with approximately 8 billion people on the planet, people aren’t ‘doing it’ for the survival of the species. Nevertheless, sex is still a ubiquitous and valued part of human life. Unfortunately, people with experience of psychosis may find their sex lives compromised for various reasons, of which this paper outlines the following:

1. Antipsychotic medication and sexual dysfunction

The link between antipsychotic medication and sexual dysfunction is widely accepted and it’s estimated that between 16-60% of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia who take antipsychotic medications experience sexual dysfunction (e. g. loss of libido, difficulty maintaining an erection, vaginal dryness, inability to orgasm) (Serretti & Chiesa, 2011).

2. Negative symptoms

The experience of psychosis/schizophrenia is often associated with a reduction in an individual’s thought processing and emotions, meaning people can struggle to be emotionally expressive, enthusiastic or motivated. Reduced functioning in these areas is often collectively referred to as ‘negative symptoms’. It is thought being emotionally inexpressive may be associated with a decrease in sexual interest and could also make it difficult to meet and interact with people (de Jager et al., 2017; Zemishlany & Weizman, 2008).

3. Stigma

Internalised stigma may increase social isolation and concerns about sexual inadequacy, having a detrimental impact on sexual interest and activity (de Jager et al., 2017, Redmond, Larkin & Harrop, 2010).

Despite these barriers, research suggests that people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia want intimate relationships (McCann, 2010; Volman & Landeen, 2007), and why shouldn’t they? As such, this paper aims to examine the correlates and predictors of sexual interest (interest in / ability to enjoy sexual activities) in people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia.

People who experience psychosis may face numerous barriers to satisfying sexual relationships.

Methods

This study was a cross sectional analysis of secondary data from three RCTs. Sexual interest was measured using an item from the Scale to Assess Negative Symptoms which measured participants sex drive/interest in sex on a six-point scale, with higher ratings indicating less interest/pleasure from sexual activities. Sexual self-efficacy (participants confidence in their ability to have sex with someone in a way that they and the other person could enjoy) was rated on a scale from 0 (no confidence) to 100 (complete confidence). Symptom severity, negative symptoms and depression were also measured. Finally, participants were asked to provide a list of the medications they were taking. As different medications have been shown to have distinct effects on sexual function, they were separated into four categories: mood stabilisers, antidepressants, cardiovascular medications and antipsychotics. Antipsychotics were further categorised, based on a previous review (Clayton et al., 2016) according to associated risk of sexual dysfunction (low, medium and high).

Results

The total sample size for this study was 231, gender split was fairly equal (52% male) and average age was 48 years old. Sexual interest was very low in just under half of participants and males were found to have significantly higher levels of sexual interest than females. The mean level of sexual self-efficacy was reported as relatively low (56.71, SD = 37.57).

Greater sexual interest was significantly correlated with younger age, greater sexual self-efficiency, lower negative symptoms – specifically flattened affect (reduced emotional expression) and alogia (poverty of speech). Type of antipsychotic medication taken was not associated with level of sexual interest, however use of cardiovascular medications was associated with having very little or no sexual interest.

In the final model, which controlled for ethnicity, living situation and marital status; sexual interest was most significantly associated with sexual self-efficacy. This suggests that those with greater confidence in their ability to have sex with someone in a satisfying way, have more interest and derive more pleasure from sexual activities. Additionally, men were significantly less likely than women to have impairment in sexual interest. Overall gender and sexual self-efficacy accounted for 31% of the variance in sexual interest scores for this sample. Although males had significantly higher sexual self-efficacy than females, there was no interaction effect between gender and sexual self-efficacy on sexual interest.

Gender and confidence in sexual ability were found to be the biggest predictors of sexual interest.

Conclusions

The authors concluded:

Findings from this analysis suggest that adults with schizophrenia have impairments in sexual interest that may be more pronounced among women but that are also significantly related to level of confidence in sexual ability.

Findings suggest that people with schizophrenia have impairments in sexual interest, these may be greater in women and related to level of sexual confidence.

Strengths and limitations

Romantic relationships in the context of psychosis/schizophrenia is an area that has been historically neglected in clinical practice and as the authors point out, a subject that practitioners often feel uncomfortable discussing with service users. It’s always great to see new papers that contribute to the relatively sparse body of literature there currently is on this topic because it gives hope that we are taking positive steps towards fully acknowledging and supporting the sexual needs of people who experience psychosis.

Many of the limitations for this study stem from the fact that the authors reanalysed existing data and therefore are constrained in many aspects of the design. Sexual interest and sexual self-efficiency are both measured using single items, additionally both seem to be measuring more than one concept: sexual interest is defined as a measure of 1) interest in sex and 2) ability to derive pleasure from sex; similarly sexual self-efficiency is defined as: 1) ability to have sex in a way they themselves would find enjoyable and 2) that the other person could enjoy, which as I’m sure many of those reading can attest to… isn’t necessarily the same thing! I would also have liked to see the bivariate correlation statistics reported as from these definitions it seems that sexual interest and self-efficiency could be collinear variables, meaning it would not be appropriate to include both in a regression model.

In relation to the demographics of the sample, the mean age of participants was fairly old. While I by no means want to insinuate that sex is a young person’s pursuit only, I think given that first experiences of psychosis tend to occur during adolescence and the findings of this study indicate interest in sex and age are negatively associated, it would have been good to see this commented upon by the authors. Similarly, it would have been good to address/account for participants’ sexual orientation as members of the LGBTQI+ community are likely to have different needs to those who identify as heterosexual and may experience intersectional discrimination relating to sexuality and psychosis (McCann et al., 2019).

This paper highlights the important but overlooked issue of sexuality in the context of schizophrenia, but use of secondary data means measures are limited.

Implications for practice

The authors suggest interventions aimed at improving intimate relationship confidence should be developed for people who experience schizophrenia. Considering the finding from this paper that lack of confidence in sex is likely due to lack of interest in sex, there is a clear question mark over whether such an intervention would be engaged with or even wanted. Therefore, it’s important to conduct further qualitative research to investigate this and ensure meaningful patient and public involvement is done during the development of any interventions.

What is also apparent from the results of this study is that men and women are likely to have different needs in terms of sexuality. A main finding from the study was that men had significantly higher levels of sexual interest and efficacy than women. The authors suggested reasons for this may be men being more willing to disclosure ‘adequate’ sex drive and a greater stigma/taboo around women’s sexuality. However I think it could equally be argued a social desirability may be at play whereby men may be less able to disclose lack of interest or confidence in relation to sex due to sexual prowess being so ingrained in socially constructed ideas of manliness and masculinity.

Finally, the authors touch on the issue of interpersonal trauma, suggesting that women’s lack of interest in sex may be due to higher rates of sexual abuse experienced by females compared to males. Whilst evidence suggests women are more likely to experience sexual abuse, it is still estimated that a quarter of men with psychosis/schizophrenia are sexually assaulted as adults and 28% have experienced childhood sexual abuse (Read, van Os, Morrison & Ross, 2005). Therefore, it is vital that any interventions relating to sexuality are trauma sensitive.

Men and women with schizophrenia may have different needs and require different support in relation to sexuality and intimate relationships.

Statement of interests

The blogger Beccy White reports no conflict of interest, but says that her PhD is about the role of romantic relationships in psychosis.

Links

Primary paper

Bianco, C. L., Pratt, S. I., & Ferron, J. C. (2019). Deficits in sexual interest among adults with schizophrenia: another look at an old problem. Psychiatric Services, 70(11), 1000-1005. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.201800403

Other references

Clayton, A. H., Alkis, A. R., Parikh, N. B., & Votta, J. G. (2016). Sexual Dysfunction Due to Psychotropic Medications. Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 39(3), 427–463. doi:10.1016/j.psc.2016.04.006

de Jager, J., Cirakoglu, B., Nugter, A., & van Os, J. (2017). Intimacy and its barriers: A qualitative exploration of intimacy and related struggles among people diagnosed with psychosis. Psychosis, 9(4), 301-309. doi: 10.1080/17522439.2017.1330895

McCann, E. (2010). The sexual and relationship needs of people who experience psychosis: quantitative findings of a UK study. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 17(4), 295-303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2009.01522.x

McCann, E., Donohue, G., de Jager, J., Nugter, A., Stewart, J., & Eustace-Cook, J. (2019). Sexuality and intimacy among people with serious mental illness: a qualitative systematic review. JBI database of systematic reviews and implementation reports, 17(1), 74-125. doi: 10.11124/JBISRIR-2017-003824

Read, J., van Os, J., Morrison, A. P., & Ross, C. A. (2005). Childhood trauma, psychosis and schizophrenia: a literature review with theoretical and clinical implications. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 112(5), 330-350. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00634.x

Redmond, C., Larkin, M., & Harrop, C. (2010). The personal meaning of romantic relationships for young people with psychosis. Clinical child psychology and psychiatry, 15(2), 151-170. doi: 10.1177/1359104509341447

Serretti, A., & Chiesa, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of sexual dysfunction in psychiatric patients taking antipsychotics. International clinical psychopharmacology, 26(3), 130-140. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e328341e434

Volman, L., & Landeen, J. (2007). Uncovering the sexual self in people with schizophrenia. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 14(4), 411-417. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01099.x

Zemishlany, Z., & Weizman, A. (2008). The impact of mental illness on sexual dysfunction. In Sexual dysfunction (Vol. 29, pp. 89-106). Karger Publishers.doi: 10.1159/000126626.

Photo credits

- Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

- Photo by freestocks on Unsplash

- Photo by Kelly Sikkema on Unsplash

- Photo by Tim Mossholder on Unsplash

- Photo by Sasha Freemind on Unsplash

- Photo by Jiroe on Unsplash

- Photo by Matheus Ferrero on Unsplash

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Problems of schizophrenia in childhood and adolescence››

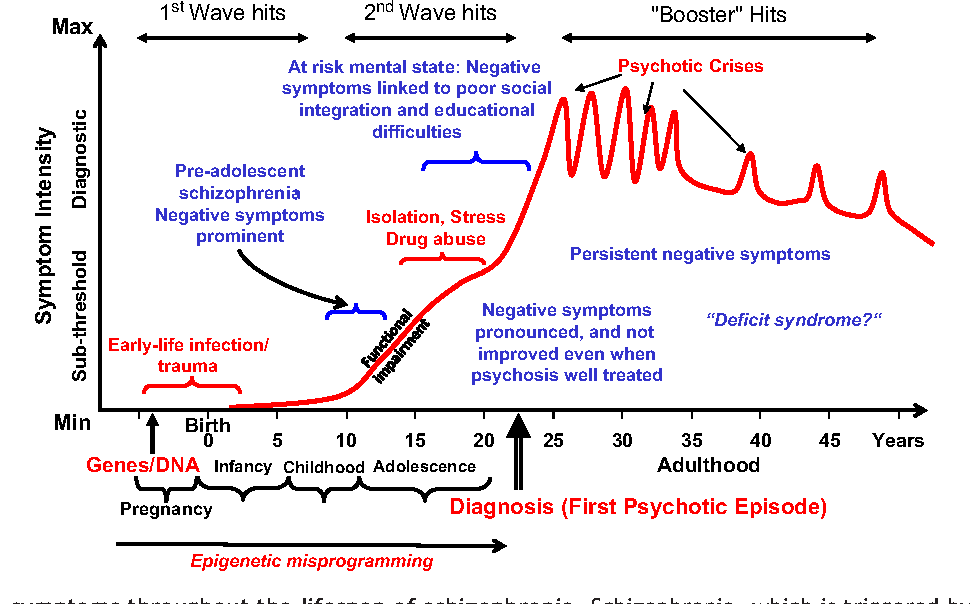

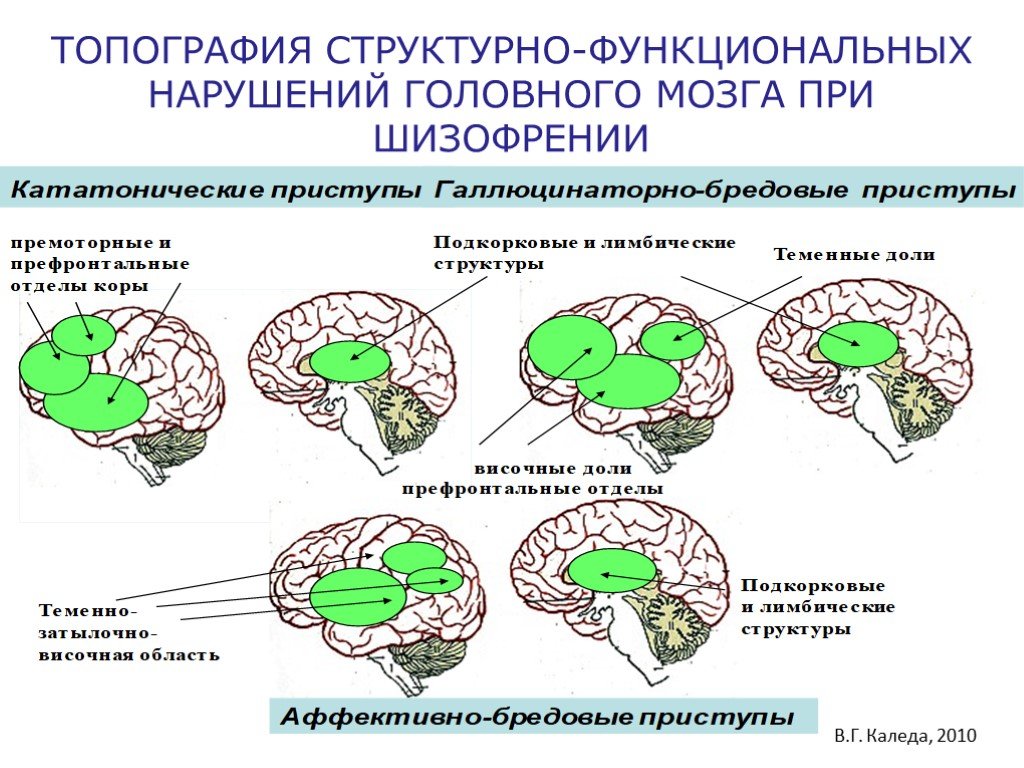

The study of affective pathology is one of the most urgent problems modern psychiatry. This is due to the fact that affective disorders are among the most universal manifestations of mental pathology and second only to asthenia in prevalence (8). In recent decades pathomorphosis of endogenous diseases with a decrease in the number of malignant forms and an increase in mild variants of the development of the disease, including among low-progressive forms of the course of schizophrenia with a predominance in the clinical picture of phasic affective disorders. This trend applies to both patients mature and pubertal age (5, 8, 16, 20). Most modern researchers note the age specificity of childhood and adolescent endogenous depression, a distinctive feature of which is the severity autonomic disorders (13, 14, 19) and a variety of behavioral disorders (4, 9), "masking" the actual affective pathology. Often erased depressive seizures are detected only retrospectively with the development of psychotic attacks level. Meanwhile, early recognition of depressive states is necessary for timely treatment of the disease and the subsequent appointment of preventive therapy. Even less studied are manic disorders that occur in childhood and adolescence. In the pedopsychiatric literature, manic phases are usually referred to in passing as the opposite of depressive states. seizures, and only a few works are devoted to the clinic and typology of mania in certain forms of children's endogenous psychoses (2, 6). Significant difficulties causes a nosological assessment of phasic affective disorders in childhood and adolescence.

According to a number of authors (1, 3), the delimitation manic-depressive psychosis from circular schizophrenia at this age becomes possible only with long-term dynamic observation. Many researchers (5, 10-12, 18) indicate the rarity of TIR before 13 years of age, its casuistry in childhood and the frequency of change initial diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis on the diagnosis circular schizophrenia during follow-up examination of patients. Insufficient development of clinical and typological issues of endogenous affective disorders in childhood and adolescence, the lack of clear diagnostic and prognostic criteria for endogenous psychoses manifesting affective seizures requires further in-depth study of this pathology.

This work is part of a clinical and course study cyclothymoid-like schizophrenia of puberty and prepubertal age, is devoted description of the features of depressive and hypomanic states in this form schizophrenia and an attempt to identify their main types.

The work included the results of observation of 51 patients (27 girls, 24 boys) aged 9-16 years with an established diagnosis of schizophrenia and the predominance in the clinical picture of affective disorders of subpsychotic level. When selecting the material, cases with severe depressive disorders were excluded. disorders (agitated and substuporous depression), as well as cases in which which affective disorders were combined with oneirism, catatonic phenomena or extended delirium (including depressive). Rationale the diagnosis of schizophrenia were signs of progression in the form of lengthening, and syndromic worsening of seizures with the addition of schizoform symptoms, as well as an increase in the patient's personality changes. In 18 patients (9girls, 9 boys) only depressive attacks were noted; at 33 patients (18 girls, 15 boys) had bipolarity affective disorders; monopolar manic course in our patients is not observed. A total of 130 depressive and 52 hypomanic states. At the age of 9-12 years, patients underwent 47 depressive and 16 hypomanic phases, from 13 to 16 years old - 83 depressive and 36 manic phases. 11 patients had well-defined depressive attacks and at an earlier age (4— 8 years), the description of which, due to their age originality, is beyond the scope of this article. Phase hypomanic states up to 9-years of age in analyzed clinical material was not identified.

Depressive cyclothymoid-like states had a variety of duration: from 1-2 days to 3 years, but protracted depression (mean duration 6 months, no notable difference in prepubertal and puberty). The clinical picture of seizures was characterized by a blurring of the clinical picture, due to a slight depth of affect, incompleteness and rudimentary accessory symptomatology. It should be noted a number of fundamentally common features of pubertal affective seizures: massiveness of somatovegetative disorders with a tendency of patients to hypochondriacal fixation; increased reflection; low availability and non-criticality of the examined both in the acute period and after its passing; lack or limitation of a verbal report in one's health and mood, which, first of all, concerned the affect of melancholy.

A feature of the studied depressions was a peculiar diurnal rhythm of affect with double deterioration of the condition throughout the day, manifested in weakness, lethargy, inactivity in the morning and the appearance of tension in the evening, anxiety, fear or irritability and malice, often accompanied by hysterical reactions. The peculiarity of depressions was the relative rarity of ideas of self-accusation with a high frequency of ideas of accusation with a feeling hostility towards others and a sense of their deliberately unfriendly relationship to yourself. In most cases, the orientation of the “pointer guilt" outside (15, 16). A hallmark of prepubertal and pubertal depressions of the cyclothymic level was the versatility and instability shade of depressive affect with its repeated change over the course of one attack. So, in the same teenager, depending on external circumstances (17) and the time of day, anxiety and restlessness prevailed, then apathy and indifference, then sullen discontent and irritability. Often the simultaneous coexistence of various depressive affects was noted: anxiety and malice, boredom and dysphoria, apathy and fear. Lability and the multidimensionality of affect complicated the identification of the main types of depression. However, on during the attack, the predominance of one or another affect was found. proceeding from the prevailing affective component, 5 types are distinguished cyclothymic depression.

In simple depression (27 attacks), the clinical picture had some similarity to sad depression in adults, however, patients rarely identified their experiences as a feeling of longing. More often they said that they were “bad”, “bored”, "sad". Sometimes they associated low mood with real troubles, but more often they could not explain their state of "tears flow by themselves", "I just want to cry." Note the sad expression faces, dull eyes. Poverty of facial expressions, slowness of gait, gesticulation became lethargic. However, the degree of expression of ideational and motor retardation was insignificant. Despite the difficulty in assimilating educational material, the children continued to study, although they prepared longer than usual hometasks. There was a fixation on the sad incidents of a past life. Reality was perceived as a chain of bleak events. Ambient seemed faded. Even pleasant events did not cause an emotional response. Characteristic was the increase in sensitivity, the desire to limit contacts. Patients did not realize the pain of their condition, rarely complained, did not They even looked for help from their parents. On the contrary, they developed hostility towards relatives and resentment towards them, arising from a feeling of uselessness by relatives, a feeling of abandonment, there was self-pity.

In anxiety depressions (33 attacks) there was a wide range of experiences from a feeling of inner discomfort, vague anxiety, which patients characterized by the expressions "restless", "somehow uneasy”, to a distinct anxiety, a feeling of “internal tension”, "inner trembling". In most cases, anxiety was vague, rarely was concretized by unreasonable fear for one's health, life or, wearing shade of transitivism, was aimed at the life and health of loved ones. facial expressions expressed anxiety, restless expectation. There was an imbalance in attention tendency to monothematic associations. The thoughts of the sick were constantly turned to upcoming events, "imminent difficulties", to a future that seemed bleak and promised nothing but grief and trouble. noted fear of failure in studies and social work. The patients felt inferior, reproached for "wrong behavior", "bad character". Often general anxiety was expressed in the desire to change the usual way in any way way of life. Teenagers vividly imagined how good their fate would have been. in new conditions and demanded from relatives decisive actions that break life families: moving to another city, changing apartments, purchasing pets etc. At the same time, the ideational animation contrasted with the motility, inactivity of the patient himself, which gave the syndrome the character dissociation.

At certain moments, the depth of affect increased sharply, immobility was replaced by psychomotor agitation, raptoid conditions that had a distinct dysphoric coloration with dissatisfaction with oneself and those around them, were accompanied by demonstrative behavior, the desire to act out of spite, to cause trouble to loved ones.

The most common in the analyzed clinical material were dysphoric depression (52 attacks). They were characterized by atypical affect with the prevalence of a gloomy mood and a hint of gloomy discontent. The motor and ideational components of depression were weakly expressed. The patients were depressed, gloomy, experienced excruciating irritability, reaching at times to spite. Often they declared: “everything is seething inside, I hate everyone”, “I want beat, break” or complained: “I am so annoyed that my whole body is buzzing - as if on vibrator stand. Any event, each act of others received from them negative rating. Lonely and malevolent, they were in opposition to the surrounding reality.

Adynamic depressions (28 attacks) were the most atypical and were expressed in a decrease in motives, lethargy, indifference, in the absence of saturated depressive affect (“headless depression”, “depression without depression"). Patients became inactive, inactive without motor lethargy. In some cases, they spent time aimlessly in solitude, in others - joined antisocial groups of teenagers, supporting with them formal contacts. They regarded their condition as "internal laziness", "laziness", "licentiousness". The disappearance of former interests, cooling to friends and family, in the absence of a component painful loss of feelings. In case of constant stimulation from adults patients continued their studies, although their productivity was significantly reduced.

Asthenic depression (7 attacks) was determined by rapid fatigue, exhaustion and irritable weakness. The children complained about the weakness and pressing headaches in the afternoon. There was intolerance to loud sounds, bright lights. There were frequent fluctuations in affect throughout the day. from irritability to lethargy and tearfulness. Difficulties were identified concentration, involvement in work and a mild decrease in productivity. These states had a clear outline in time, arose in the spring, and more often in autumn time.

Their evaluation as depressive was based on the absence of real reasons for the emergence of a true asthenic state, seasonality, a peculiar circadianity, as well as the appearance after a while of seizures with a distinct depressive affect.

Depressions of all types, except for asthenic, were accompanied by suicidal trends. In simple, anxious, dysphoric variants, suicidal attempts had the character of surprise, arose after an objectively insignificant psychotrauma, which sharply exacerbated the existing depressive experiences, and proceeded by the type of "short circuit" reactions. Sometimes they were demonstrative behavior, which by no means excluded the seriousness of suicidal intentions and possible death (7). Under adynamic conditions suicidal actions arose against the background of monotonous depression without prior provocations, were thought out and prepared in advance, accompanied by ridiculous explanations: “I decided to check how people die” and, apparently, were of the nature pathological desires.

All variants of the depressive syndrome were characterized by atypia, expressed in greater or to a lesser degree, consisting either in the atypicality of the affect itself, or in its vestigiality, or in the disproportionality of the components of the depressive triad. The most atypical were dysphoric and adynamic depressions, and simple depression to a certain extent approached the corresponding classical variant of the affective syndrome.

Depressive symptoms that dominated the pattern of seizures are extremely rare acted in isolation. In most cases, it was combined with multiple, but erased disorders of other registers. Schizophrenic symptoms were most often manifested by thinking disorders in the form of small automatisms (sperrungs, confusion of thoughts, influxes), rudimentary persecutory delirium, "a sense of the presence of an outsider", episodes of causeless fear, rudimentary deceptions of perception (calls, senestopathies, extracampal hallucinations, hallucinations of the imagination). Accessory symptoms were supplemented various obsessions (ideational, motor, elementary phobias), specific to puberty, overvalued ideas (dysmorphophobia, metaphysical intoxication), psychopathic disorders behavior and, in some cases, paradoxical on the background of depression, increased drives. In several supervision inclinations of mastering character were noted. They were extremely diverse: from the desire to buy toys, prestigious clothes to ridiculous acts with dromomanic or sexual overtones. attraction arose only against the background of depression, fading away during remission and resuming during subsequent depressive episode.

It should be emphasized that all the above disorders were multiple, but are rudimentary and did not determine the clinical picture of the disease as a whole. Combination affective disorders with rudimentary schizophrenic, neurosis-like and psychopathic symptoms formed a complex and atypical syndrome. The most diverse and rich accessory symptomatology was observed with dysphoric and anxious type of seizures; most atypical and dissociated the clinical picture was presented in the case of dysphoric and especially adynamic variant (character of affect, disharmony of the triad, combination depression and cravings, apathy and suicide). Asthenic depressions and most attacks in a simple variant of depression were limited to disorders affective circle.

Hypomanic seizures were characterized by simplicity and monomorphism clinical picture, almost exhausted by typical or atypical affective syndrome. In this they significantly differed from the structure of depressive seizures in the same patients. With hypomania, only in some observations, affective symptoms were supplemented by metaphysical intoxication, stereotypical games or weakened, but not extinguished against the background of increased affect senestopathies, motor obsessions and dysmorphophobic ideas. Neither in one observation did not reveal violations of thinking in the form of "small automatisms", rudimentary hallucinatory or delusional symptoms. typical of hypomania turned out to be the indistinctness of daily fluctuations of affect and the severity of the vegetative symptoms: eye shine, blush, weight gain, diarrhea, reduced sleep duration, etc. All hypomanic states were accompanied by a revival of drives. Duration of hypomania correlated with the age of patients: prepubertal period was dominated by short-term state (1 day-1 month), in 6 patients the duration intermittent hypomania was measured over several hours; in puberty the age of hypomania were longer (2 weeks - 6 months), and in In 2 cases x duration exceeded 8 months.

In accordance with the leading affect, 5 variants of hypomanic states.

"Cheerful" (or simple) hypomania (17 observations) approached classic variant of cyclothymic mania and was characterized by harmony of all components of the affective triad. optimistic mood, benevolence, playfulness were combined with a sense of cheerfulness and physical well-being, were accompanied by a revival of motor skills and a slight acceleration of ideational processes. Moderate verbosity was noted, activity kept purposefulness. Increased productivity, facilitated contacts with around, self-confidence appeared. Present and future seemed wonderful. Behavior was characterized by liveliness, initiative, high activity. Premorbid schizoid features of patients became inconspicuous. Hypomania gave the behavior a temporary appearance of syntonicity and extraversion.

A common feature of benevolent and foolish hypomanias was a distinct decrease in productivity.

Complacent hypomania (11 observations) was characterized by the prevalence affect over the ideational and motor components. The mood was dominated carefree contentment and serenity. Past failures and sorrows are sick regarded as insignificant, unworthy of attention events. The future is not caused them anxiety, and rosy prospects seemed easily achievable. Increased self-esteem, self-confidence combined with a variety of unstable plans for both the near and long term. At the same time, children remained passive and inactive, avoiding any kind of work. At most patients showed a decrease in sensitivity, appeared condescending and benevolent attitude towards others, however, the desire for there was no communication, there was no need for contacts with peers, low accessibility remained, i. e. such features like introversion and autism.

In goofy hypomania (6 cases), affect was also atypical. On against the backdrop of a benevolent mood, laughter prevailed, often inadequate situations. Lively motor skills were combined with an accelerated tempo of speech, and increased activity was expressed in ridiculous pranks, antics, rude jokes and mimicry. There was a decrease in criticism; suffered, though not lost completely, a sense of distance. Patients lived momentary entertainment, reluctantly talked about their past and future; in any topic of conversation they found situations that made them happy were amused by their own comparisons, jokes. Children were not burdened by the society of their peers, because they found among them are "spectators" who are able to "appreciate" their pranks, but to establish friendly relations did not try, being content with formal contacts and remaining essentially autistic.

In case of hypomania with irritability (12 observations), affect acquired dysphoric coloration. The high spirits were combined with dislike for others, especially relatives, pickiness, outbursts of anger, conflict. Behavior was characterized by arrogance, exactingness, ideas reassessment of one's own personality and the desire to establish oneself in society. The patients perceived the instructions of the elders as “an infringement of their rights”. protest against "repression" of adults was expressed in demonstrative disobedience, rudeness, willfulness. Easily entering into contacts with peers, patients do not established friendly relations, remaining secretive and malevolent. Their entertainments retained an autistic character, and lively drives often acquired a heboid hue. Due to mobility and activity, patients easily achieved success not only in daily activities, but also in numerous hobbies that arose during this period.

Hypomania with unilateral activity (6 cases) was characterized by a pronounced increase in the vital-energy tone in the absence of thymic component. Patients did not note joy or fun, but spoke of a feeling of unusual physical vigor, a surge of strength. They developed an ebullient activities in which they showed perseverance and indefatigability, not paying attention to adverse external circumstances; in 2 cases, a decrease was detected pain sensitivity. Usually there was some kind of passion, rapidly becoming overvalued. indecisive and passive premorbid, patients became active and purposeful, remaining however secretive and inaccessible. Their activities were of an autistic nature. They actively avoided communication, initiating only the elite into their hobbies.

The descriptions given are of shallow depth as well as originality of hypomanic states, the clinical picture of which in most cases is determined by a combination of atypical affective symptoms and patient's personality traits.

It should be noted that the vast majority of children with low-progressive cyclothymoid-like schizophrenia (50 people), were taken under observation during a depressive attack. The fact drew attention late visit to a psychiatrist (not earlier than 2 months after the onset of affective, disorders, and more often with repeated attacks), which in a certain least confirmed the shallow level of the affective syndrome. Despite erasure of depressive disorders, 44 patients underwent a course of inpatient treatment followed by dynamic outpatient monitoring and only 7 people were exclusively under outpatient supervision. The immediate reason for the stationing was not affective disorders, and the school maladjustment that arose against their background and various behavioral disorders, the mechanisms of which were complex and ambiguous. At the core school maladjustment, expressed in a decrease in academic performance, fear of children's team, verbal responses, stubborn refusal to attend school, violation of contact with classmates, conflict, lay a complex complex endogenous depressive disorders and personal protective reactions that occurred in a response to one's own intellectual inconsistency with difficulties in comprehending and reproduction of school material, which was accompanied by a reduced self-esteem and sensitive ideas of attitude.

In some cases, refusal to attend school was associated with a weakening of mental tone and the desire in any way avoid volitional tension. Finally, the reason for not attending school, conflict, aggressive behavior were often non-positive ideas relationship. At the same time, the patients were convinced that classmates avoided communicate with them, deliberately humiliate, insult, and teachers, “disliked”, underestimate estimates, make unreasonable remarks, “find faults”. Trying to be rude and to defend their dignity by force, the patients themselves provoked quarrels and fights, they often carried primitive weapons of "defense" with them. Aggressive behavior in most cases were exacerbated by a dysphoric mood background. Gloomy, everyone dissatisfied, angry, children often beat not only their peers, but also relatives. IN in some cases, adolescents, cut off from the life of the class, closed and unfriendly in the family and, at the same time, experiencing their own failure, experiencing constant anxiety, boredom or sadness, adjoined to asocial companies, started smoking, drinking alcohol.

The symptoms described above arose only against the background of depression, fading away in period of remission and resuming with a subsequent depressive attack, which allows us to speak about the secondary nature of maladaptive symptoms in relation to affective disorders.

Hypomanic states, due to the nature of the affect, obliteration and simplicity clinical picture, were not accompanied by pronounced social maladaptation. On the contrary, in most cases they were regarded by the patient himself and his relatives. as periods of "complete well-being", "happy respite". First of all, this concerned conditions corresponding to a simple and benign variant of the syndrome, in which patients easily adapted to any conditions, without creating difficulties in the team of children and endearing others with fun, gentleness and benevolence. The behavior of patients during periods of hypomania with unilateral activity, despite the low availability and isolation of children, caused others also have a positive emotional resonance, due to the high activity of patients who do not need external stimulation, persistence of interests, the speed of achieving the goal, and subsequently used as an illustration "exemplary" behaviour. A different picture was observed in hypomania with irritability or foolish hypomania, during which the behavior of patients acquired a distinct psychopathic coloring. Malevolence conflict, exaggerated opposition, geboid shade of inclinations in the first case and a tendency to absurd pranks, inadequate jokes with the loss of criticism - in the second, they led to maladjustment of patients, caused displeasure of others, due to the discrepancy between the behavior of adolescents of the situation and the short duration corrections. However, in these cases, the condition of patients was rarely regarded surrounding as a manifestation of mental pathology, but was subjected, as a rule, psychological interpretation with the attempts of pedagogical impact.

These reasons explained the rarity of the initial visit to a psychiatrist in period of hypomania (single case). The vast majority of hypomanic conditions were detected directly in the course of dynamic observation of the patient or retrospective assessment of anamnestic data.

Thus, the analysis of clinical material showed that affective seizures of the cyclothymic level in the framework of low-progressive schizophrenia in patients of prepubertal and pubertal age have a specific age coloration and structure. Depressive episodes are characterized atypicality and complexity of the clinical picture, which consists in a combination of erased affective disorders with rudimentary productive schizophrenic disorders, neurosis-like and psychopathic symptoms. inclination seizures to a long course and late referral to a psychiatrist lead to development against the background of subpsychotic disorders of the phenomena of social maladjustment, from which implies the need for complex treatment, including not only psychopharmacotherapy, but also a number of medical and educational activities aimed at social rehabilitation and readaptation of patients. The absence of the patient or his relatives complaining of periods of high spirits and increased activity does not rule out the possibility of bipolar , disease course. Hypomanic states are distinguished by their simplicity and monomorphic structure, exhausted in most cases by an atypical affective symptom complex and the personal characteristics of the patient. Erasure of the clinical picture of seizures with inadequate assessment of the condition by the patient himself and his relatives dictates the need for long-term dynamic observation of the patient to identify the type and forms of the course of the disease, as well as timely changes in therapy.

LITERATURE

1. Vrono M. Sh. Some features of depressive conditions in children with schizophrenia. In: Scientific and Practical Conference on Children's psychoneurology. M., 1973, p. 28-29.

2. N. M. Iovchuk, L. M. Kalinina, Kiveliovich A. M. Typological features of endogenous manic states in teenagers. In: Actual problems of clinic, treatment and social rehabilitation of the mentally ill. M., 1982, p. 70-72.

3. Lapides M. I. Clinical and psychopathological features depression in children and adolescents. In: Questions of child psychiatry. M., 1940, p. 39-77.

4. Lichko A.E. Adolescent psychiatry. L., 1979, p. 66-72.

5. Lichko A.E., Ozeretskovsky S.D. Features of the clinic and course of I depressive phases in MDP in adolescence. In Sat: Actual problems of psychiatry in childhood and adolescence. M., 1976, p. 146-153.

6. Lomachenkov A.S. Clinical course of TIR in children and adolescents (clinical follow-up and EEG study). Diss. cand., L., 1978.

7. Ponizovsky A. M. Variants of suicidal behavior of patients with TIR and cyclothymia. Diss. cand. L., 1980.

8. Snezhnevsky A. V. Depressions. Clinical issues, psychopathology, therapy. Symposium materials. Moscow-Basel, 1970, p. 5.

9. O. D. Sosyukalo, A. A. Kashnikova, Tatarova I. N. Psychopathic equivalents of depression in children and adolescents. Journal. neuropatol. and psychiatrist., 1983, No. 10, p. 1522-1526.

10. Sukhareva G. E. Clinical lectures on child psychiatry age. M., 1955.

11. Asperger H. Heilpadagogik. 2. Aufl. Vienna, 1956.

12. Barton-Ha11 M. "Nerv. Childh.", 1952, v. 9, 319-325.

13. Frommer E. Treatment of childhood depression with antidepressants. Brit Med. J., 1967, 1, 729-732.

14. G1asser K. Masked depression in children and adolescents. amer. J. Psychother., 1966, 5, 565-574.

15. Creve1en D. A. van. Acta paedopsychiat., 1972, v. 38, p. 202-210.

16. Kuhn V. and R. Depressive States in Childhood and Adolescence. Stockholm 1972, 455-459.

17. Negri M. de, More11i G. Depressive States in Childhood and Adolescence. Stockholm, 1972, pp. 182-190.

18. Stock er F. G. von—Jb. Jugendpsychiat. (Stuttg.), 1956, Bd. 1, s. 223-232.

19. Stu11e H. Depressive States in Childhood and Adolescence. Stockholm, 1972, 29-34.

20. Weitbrecht H. J. Depression. Clinical issues, psychopathology, therapy. Symposium materials. Moscow-Basel, 1970, p. 7.

SUMMARY

Examination of 51 patients aged 9-16 years, suffering from low-progressive schizophrenia, occurring with a predominance of clinical picture of affective disorders of the cyclothymic level. Analyzed 130 depressive and 52 manic episodes. 5 types identified depressive syndrome (simple, anxious, dysphoric, adynamic and asthenic depression) and 5 types of hypomanic syndrome (“cheerful”, complacent, goofy hypomania, hypomania with irritability, and hypomania with unilateral activity). Rudimentary productive symptoms are described, supplementing affective disorders in the structure of a polymorphic seizure.

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Heboid schizophrenia››

In contrast to that described above, in 27 patients with juvenile paranoid schizophrenia with an initial heboid stage, the picture of heboid syndrome was more similar to its manifestations in juvenile low-progressive heboid schizophrenia. In this regard, it is more difficult to single out specific, distinctive features. As the analysis showed, here the picture was very close to the manifestations of the heboid syndrome in that variant of juvenile low-progressive heboid schizophrenia, where the disease does not end upon reaching maturity, but is characterized by a continuous sluggish course.

In this group of patients, as well as in the case of a sluggish variant of heboidophrenia, the heboid state arose against the background of a noticeable defect in the emotional and volitional spheres. Negative changes here and in the future were somewhat less pronounced than in the malignant form. The study showed that for juvenile paranoid schizophrenia, the most characteristic is reduced-heboid (19 patients) and defective-heboid (5) types of heboid syndrome are less characteristic, and the "purely" heboid (2) and affective-heboid (1) variant are very rare. The picture of the heboid state for a long time here retains a relatively stationary character, there is no increase or noticeable complication of heboid disorders. Signs of the course of the disease are extremely erased, social adaptation decreases gradually.

As established by V. N. Eliava (1982), geboid disorders were detected here early and most often with the onset of puberty. The onset of the disease is characterized by the appearance and intensification of isolation, alienation from loved ones, against the background of these signs there is a noticeable desire to be independent, neglect of everyday activities, rudeness, arrogance in relations with others. Further complication of heboid disorders occurs, as a rule, unevenly. In some cases, capriciousness, discontent, conflict, isolation from real interests, craving for idle pastime, anti-social environment, scams, thefts become dominant, in others - unleashing desires with alcohol abuse, drugs, sexual promiscuity. Departing from practically useful activities, many were inclined to unproductive pursuits in art, architecture, reading philosophical books, but were interested in this only superficially and without real understanding. There was a tendency to drawing, posturing, extravagance. There were also autochthonous mood swings in the form of very blurred affective phases (hypomania and adynamic depression). They were of a protracted nature and usually significantly deepened the psychopathic behavior of patients.

18 out of 27 patients systematically abused alcohol, and 6 of them had signs of chronic alcoholism. Of the 7 drug abusers, one had signs of addiction. In the studied patients, despite the presence of additional hazards (imprisonment, somatic diseases, intoxication effects), as a rule, there were no transient delirious episodes or short-term delusional outbreaks of the type of situational paranoid described by S. A. Izvolsky (1982) in low progression heboid schizophrenia. Only in one case there was an episode of alcoholic hallucinosis. These patients also differed from those with heboidophrenia in a number of other ways. First, a detailed analysis drew attention to their early detection of special alertness, suspiciousness and increased vulnerability in relation to others. They had an opinion that teachers, fellow students, relatives treat them for a reason, they try to “hurt”, infringe on their interests, put them in an unseemly light, laugh at their shortcomings, physical and personal. Some had thoughts about the possibility of having a specific somatic disease that others notice and hide from them, about their physical defects, noticeable and unpleasant for others. Thus, in contrast to low-progressive heboid schizophrenia, delusional register disorders were gradually woven into the structure of the heboid syndrome. In cases where heboid disorders were combined with alcohol abuse, these delusional manifestations were often difficult to distinguish from the sensitive nature of the paranoid inclusions that occur in a state of hangover in patients with alcoholism.

It should be noted that there have long been indications of cases of this kind in the literature. J. Prichard (1835), who singled out the so-called moral insanity, for the first time described in detail among these sick people, called morally insane, in whom the disease, which began in adolescence with aspirations for vagrancy, theft, arson, with a tendency to excessive drunkenness, a desire to revel , ended in dementia with an outcome in hallucinatory-delusional psychosis. S. A. Sukhanov (1905), V. Strohmeyer (1913), O. Diem (1903), S. Pascal (1911) also wrote that the initial phase of youthful insanity, manifested by alcoholism, along with other psychopathic disorders, often ends in severe dementia with chronic hallucinatory-delusional psychosis.

K. Graeter (1909) wrote most clearly about the great difficulties in clinical differentiation between dementia praecox and alcoholic mental disorders in some young patients. The author, who studied these cases in an asylum for alcoholics, became convinced that among these only "seeming" drunkards there are various mental patients and, in particular, young eccentric individuals with incorrect behavior, in which drunkenness is not a cause, but a consequence of a mental disorder. Following follow-up of these patients follow-up, in some of them the development of chronic delusional psychosis was found in the future. Discussing the problem of differential differentiation of the disease in these patients at the first stages in adolescence between alcoholism and psychopathic disorders within the framework of dementia praecox, the author attached more importance to the following number of particular features: special irritability of patients, their inadequate rage, isolation, “hints” of persecution, unsystematized ideas poisoning, stereotyping of speech and movements, a frozen look. Manifest delusional psychosis, which developed against the background of sluggish psychopathic heboid disorders with alcoholism, as the author points out, was often difficult to distinguish from acute alcoholic hallucinosis or prison delusional psychosis, although later, becoming a chronic hallucinatory-delusional psychosis, it acquired characteristic endogenous signs.