How do you change your personality

I Gave Myself Three Months to Change My Personality

The author, photographed in December (Illustration by Gabriela Pesqueira; photographs by Devin Christopher for The Atlantic)Science

The results were mixed.

By Olga KhazanThis article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic, Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

One morning last summer, I woke up and announced, to no one in particular: “I choose to be happy today!” Next I journaled about the things I was grateful for and tried to think more positively about my enemies and myself. When someone later criticized me on Twitter, I suppressed my rage and tried to sympathize with my hater. Then, to loosen up and expand my social skills, I headed to an improv class.

I was midway through an experiment—sample size: 1—to see whether I could change my personality. Because these activities were supposed to make me happier, I approached them with the desperate hope of a supplicant kneeling at a shrine.

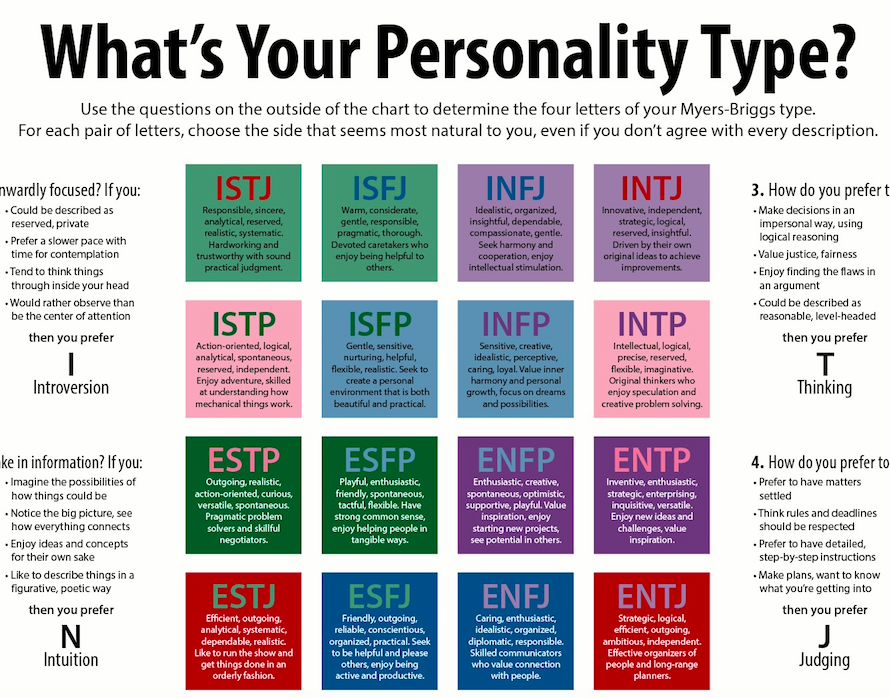

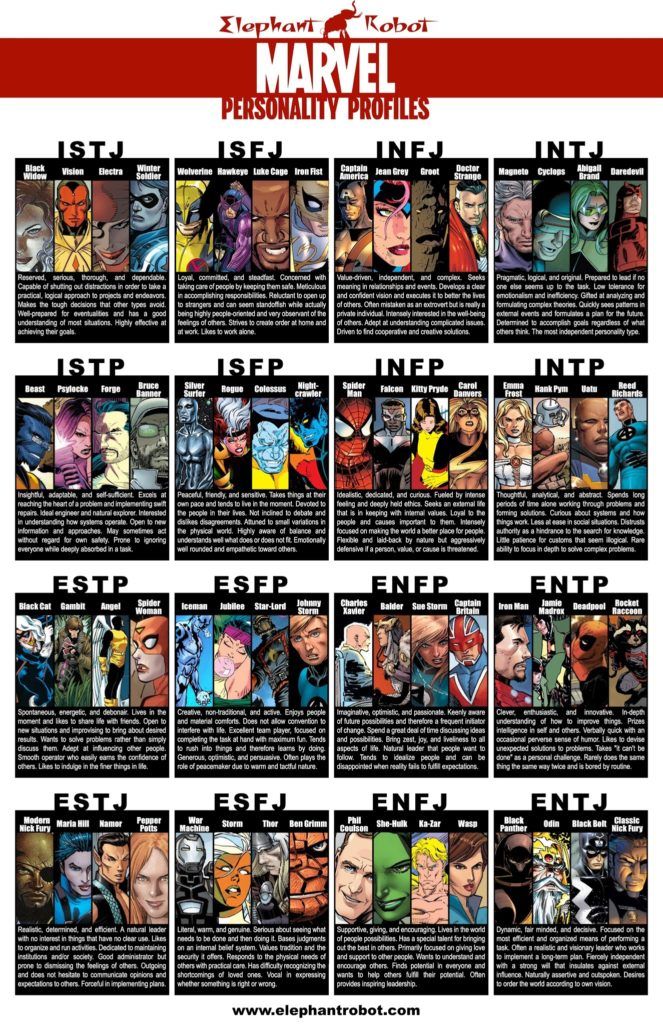

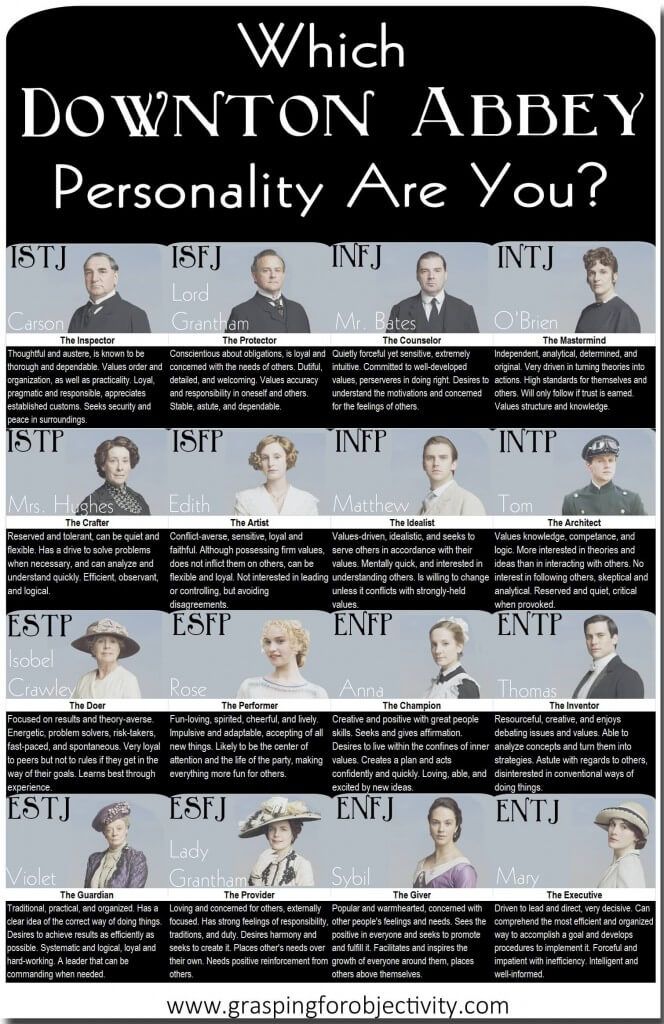

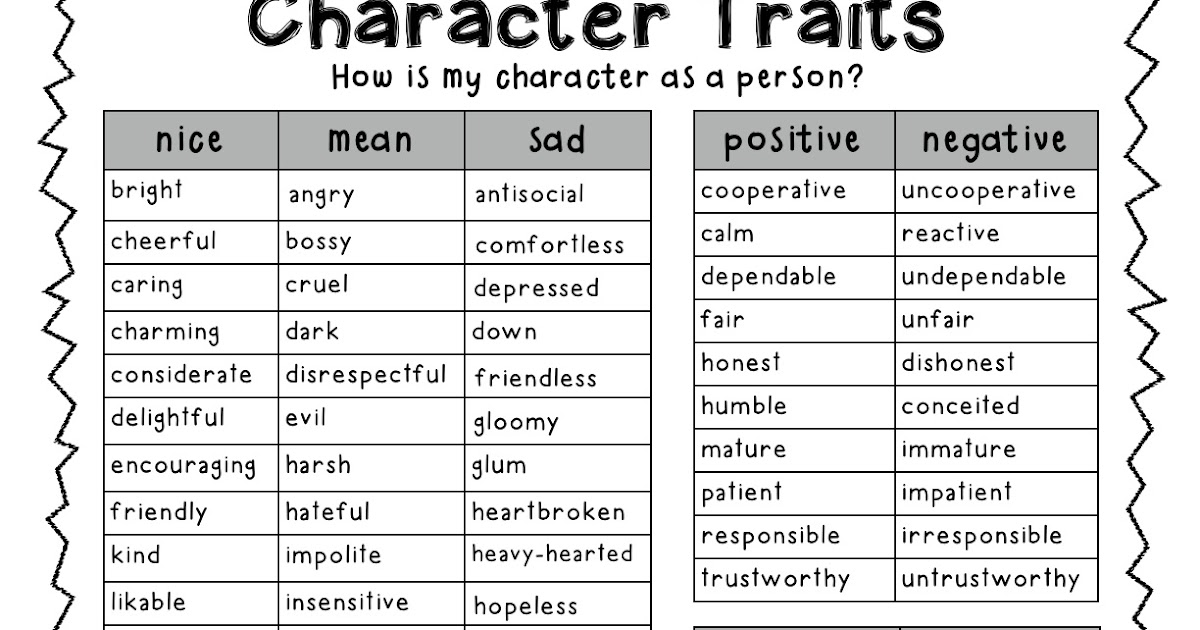

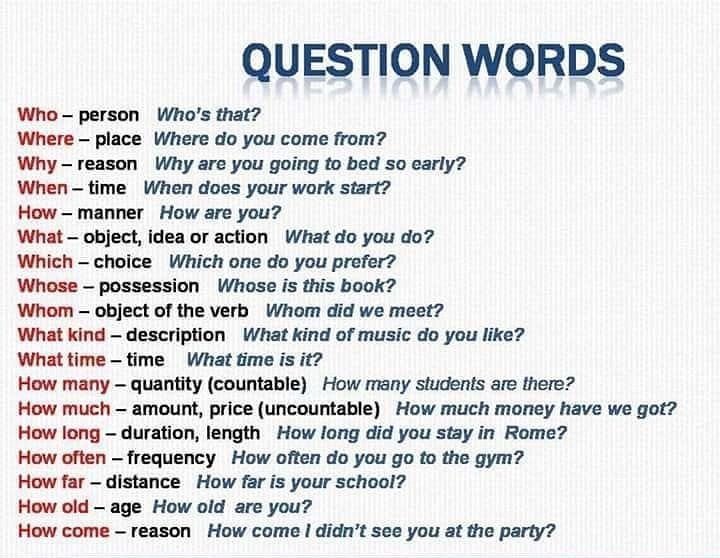

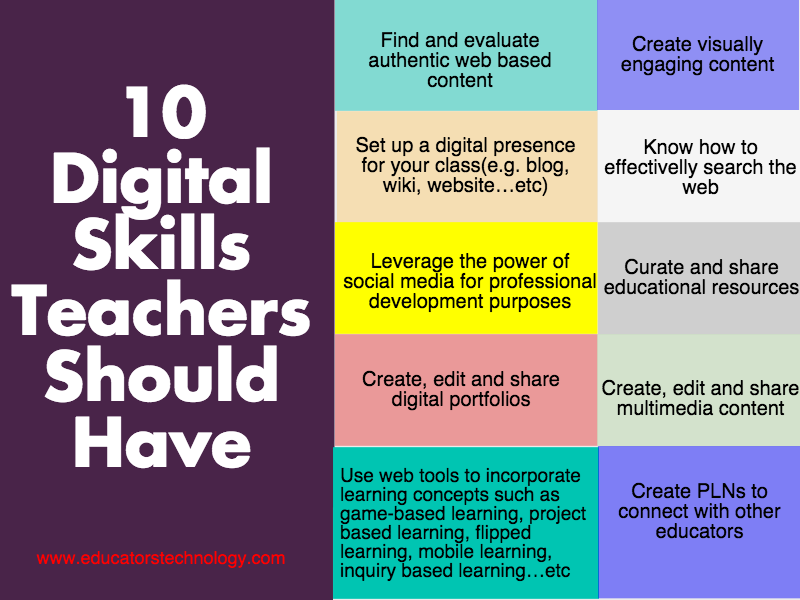

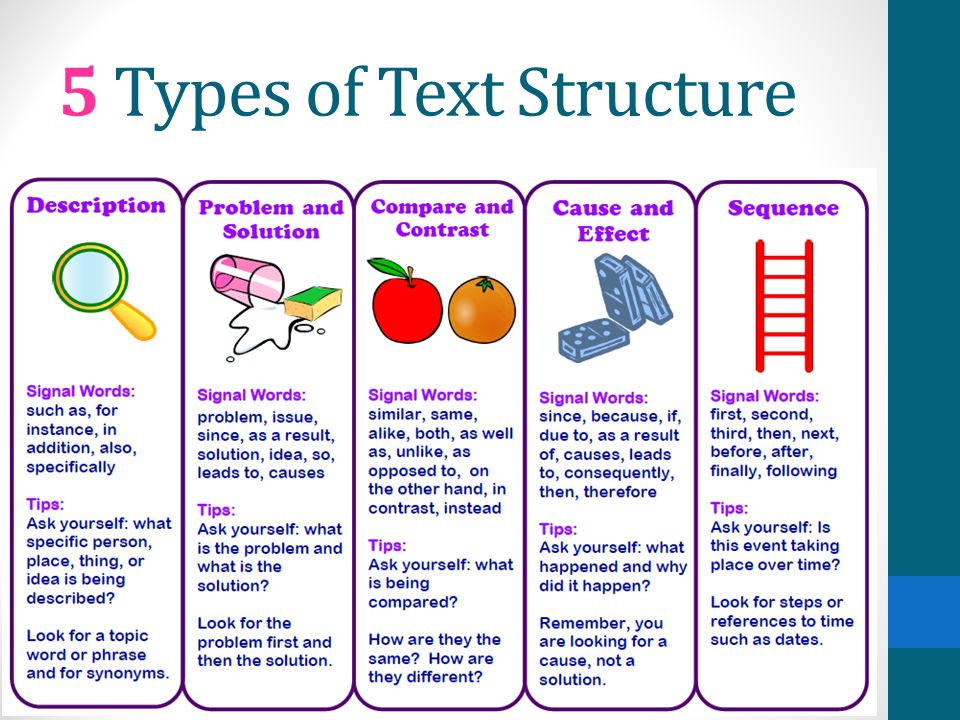

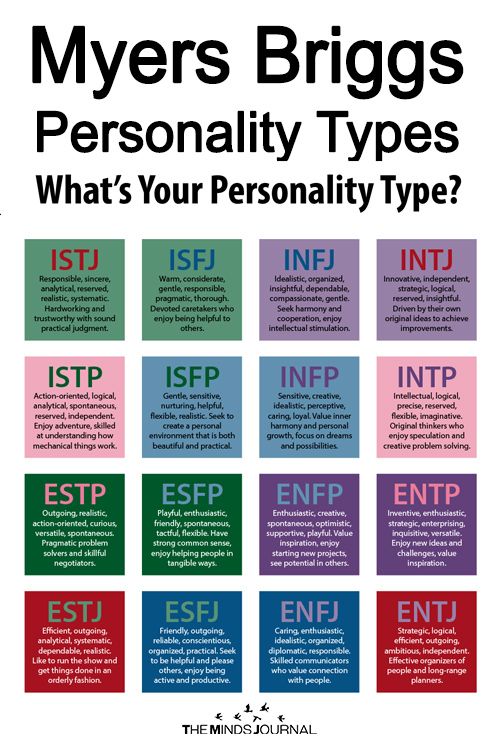

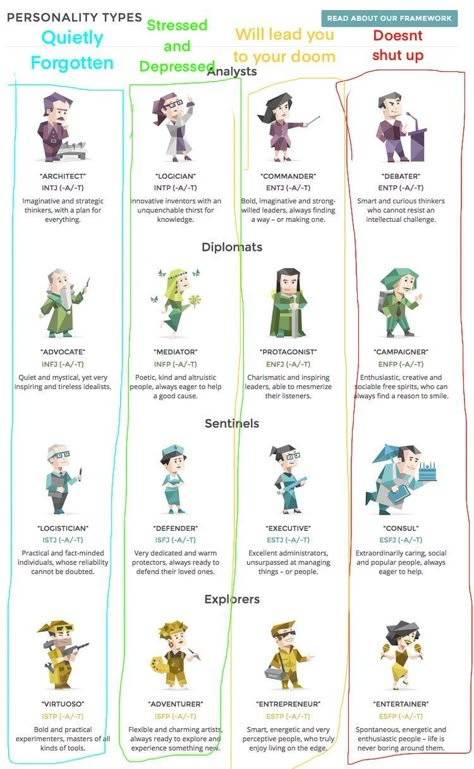

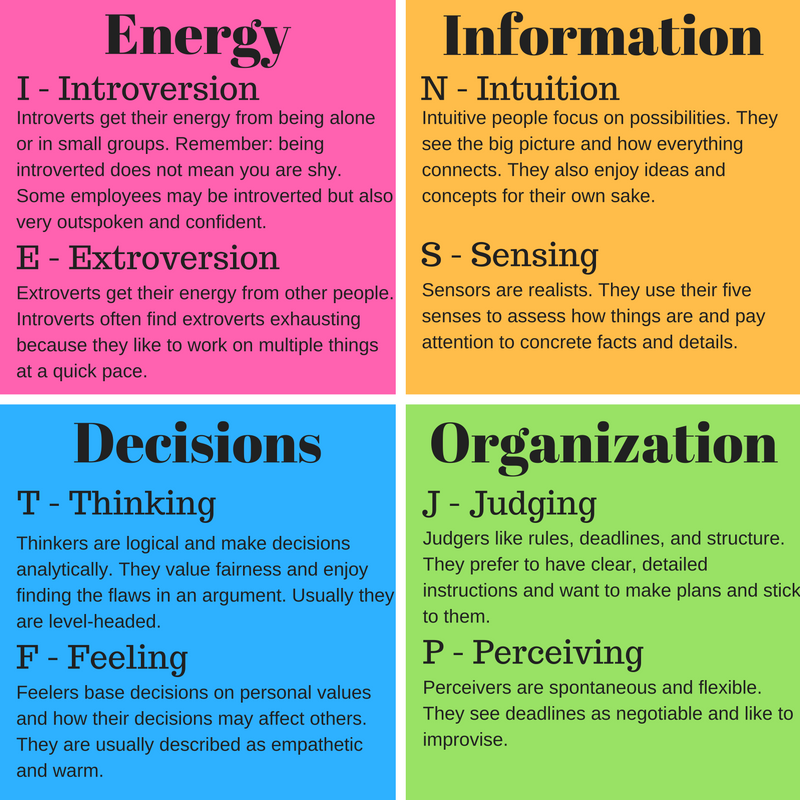

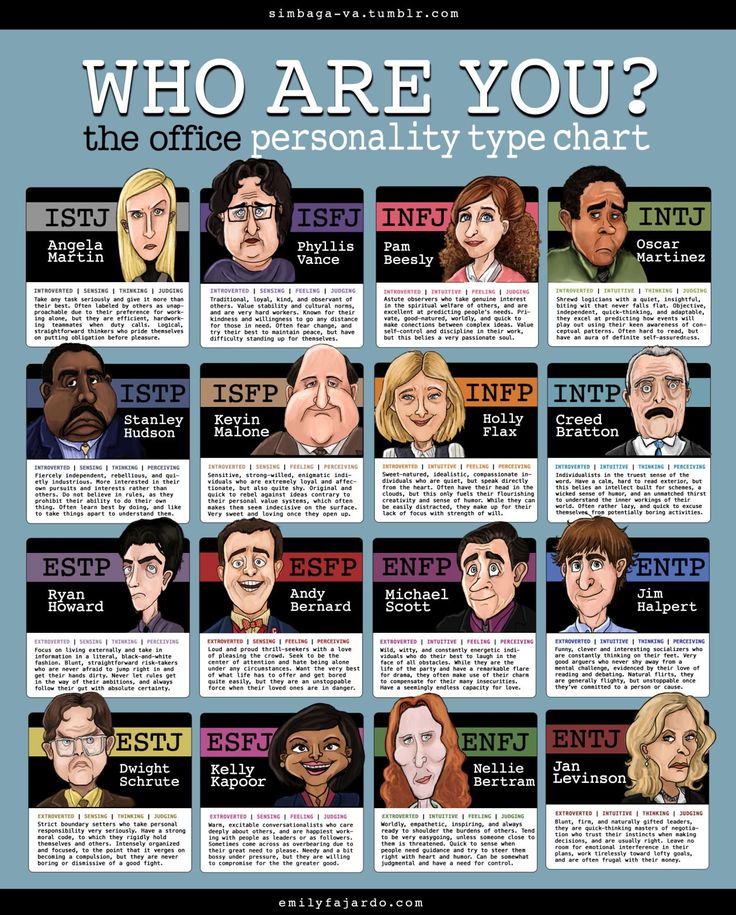

Psychologists say that personality is made up of five traits: extroversion, or how sociable you are; conscientiousness, or how self-disciplined and organized you are; agreeableness, or how warm and empathetic you are; openness, or how receptive you are to new ideas and activities; and neuroticism, or how depressed or anxious you are. People tend to be happier and healthier when they score higher on the first four traits and lower on neuroticism. I’m pretty open and conscientious, but I’m low on extroversion, middling on agreeableness, and off the charts on neuroticism.

Researching the science of personality, I learned that it was possible to deliberately mold these five traits, to an extent, by adopting certain behaviors. I began wondering whether the tactics of personality change could work on me.

I’ve never really liked my personality, and other people don’t like it either. In grad school, a partner and I were assigned to write fake obituaries for each other by interviewing our families and friends. The nicest thing my partner could shake out of my loved ones was that I “really enjoy grocery shopping.” Recently, a friend named me maid of honor in her wedding; on the website for the event, she described me as “strongly opinionated and fiercely persistent.” Not wrong, but not what I want on my tombstone. I’ve always been bad at parties because the topics I bring up are too depressing, such as everything that’s wrong with my life, and everything that’s wrong with the world, and the futility of doing anything about either.

Neurotic people, twitchy and suspicious, can often “detect things that less sensitive people simply don’t register,” writes the personality psychologist Brian Little in Who Are You, Really? “This is not conducive to relaxed and easy living.” Rather than being motivated by rewards, neurotic people tend to fear risks and punishments; we ruminate on negative events more than emotionally stable people do. Many, like me, spend a lot of money on therapy and brain medications.

Many, like me, spend a lot of money on therapy and brain medications.

And while there’s nothing wrong with being an introvert, we tend to underestimate how much we’d enjoy behaving like extroverts. People have the most friends they will ever have at age 25, and I am much older than that and never had very many friends to begin with. Besides, my editors wanted me to see if I could change my personality, and I’ll try anything once. (I’m open to experiences!) Maybe I, too, could become a friendly extrovert who doesn’t carry around emergency Xanax.

I gave myself three months.

The best-known expert on personality change is Brent Roberts, a psychologist at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Our interview in June felt, to me, a bit like visiting an evidence-based spiritual guru—he had a Zoom background of the red rocks of Sedona and the answers to all my big questions. Roberts has published dozens of studies showing that personality can change in many ways over time, challenging the notion that our traits are “set like plaster,” as the psychologist William James put it in 1887. But other psychologists still sometimes tell Roberts that they simply don’t believe it. There is a “deep-seated desire on the part of many people to think of personality as unchanging,” he told me. “It simplifies your world in a way that’s quite nice.” Because then you don’t have to take responsibility for what you’re like.

But other psychologists still sometimes tell Roberts that they simply don’t believe it. There is a “deep-seated desire on the part of many people to think of personality as unchanging,” he told me. “It simplifies your world in a way that’s quite nice.” Because then you don’t have to take responsibility for what you’re like.

Don’t get too excited: Personality typically remains fairly stable throughout your life, especially in relation to other people. If you were the most outgoing of your friends in college, you will probably still be the bubbliest among them in your 30s. But our temperaments tend to shift naturally over the years. We change a bit during adolescence and a lot during our early 20s, and continue to evolve into late adulthood. Generally, people grow less neurotic and more agreeable and conscientious with age, a trend sometimes referred to as the “maturity principle.”

Longitudinal research suggests that careless, sullen teenagers can transform into gregarious seniors who are sticklers for the rules. One study of people born in Scotland in the mid-1930s—which admittedly had some methodological issues—found no correlation between participants’ conscientiousness at ages 14 and 77. A later study by Rodica Damian, a psychologist at the University of Houston, and her colleagues assessed the personalities of a group of American high-school students in 1960 and again 50 years later. They found that 98 percent of the participants had changed at least one personality trait.

One study of people born in Scotland in the mid-1930s—which admittedly had some methodological issues—found no correlation between participants’ conscientiousness at ages 14 and 77. A later study by Rodica Damian, a psychologist at the University of Houston, and her colleagues assessed the personalities of a group of American high-school students in 1960 and again 50 years later. They found that 98 percent of the participants had changed at least one personality trait.

Even our career interests are more stable than our personalities, though our jobs can also change us: In one study, people with stressful jobs became more introverted and neurotic within five years.

With a little work, you can nudge your personality in a more positive direction. Several studies have found that people can meaningfully change their personalities, sometimes within a few weeks, by behaving like the sort of person they want to be. Students who put more effort into their homework became more conscientious. In a 2017 meta-analysis of 207 studies, Roberts and others found that a month of therapy could reduce neuroticism by about half the amount it would typically decline over a person’s life. Even a change as minor as taking up puzzles can have an effect: One study found that senior citizens who played brain games and completed crossword and sudoku puzzles became more open to experiences. Though most personality-change studies have tracked people for only a few months or a year afterward, the changes seem to stick for at least that long.

In a 2017 meta-analysis of 207 studies, Roberts and others found that a month of therapy could reduce neuroticism by about half the amount it would typically decline over a person’s life. Even a change as minor as taking up puzzles can have an effect: One study found that senior citizens who played brain games and completed crossword and sudoku puzzles became more open to experiences. Though most personality-change studies have tracked people for only a few months or a year afterward, the changes seem to stick for at least that long.

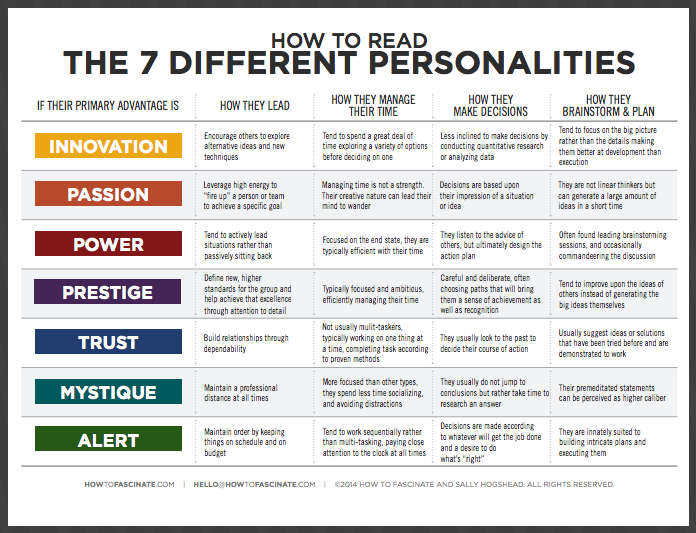

When researchers ask, people typically say they want the success-oriented traits: to become more extroverted, more conscientious, and less neurotic. Roberts was surprised that I wanted to become more agreeable. Lots of people think they’re too agreeable, he told me. They feel they’ve become doormats.

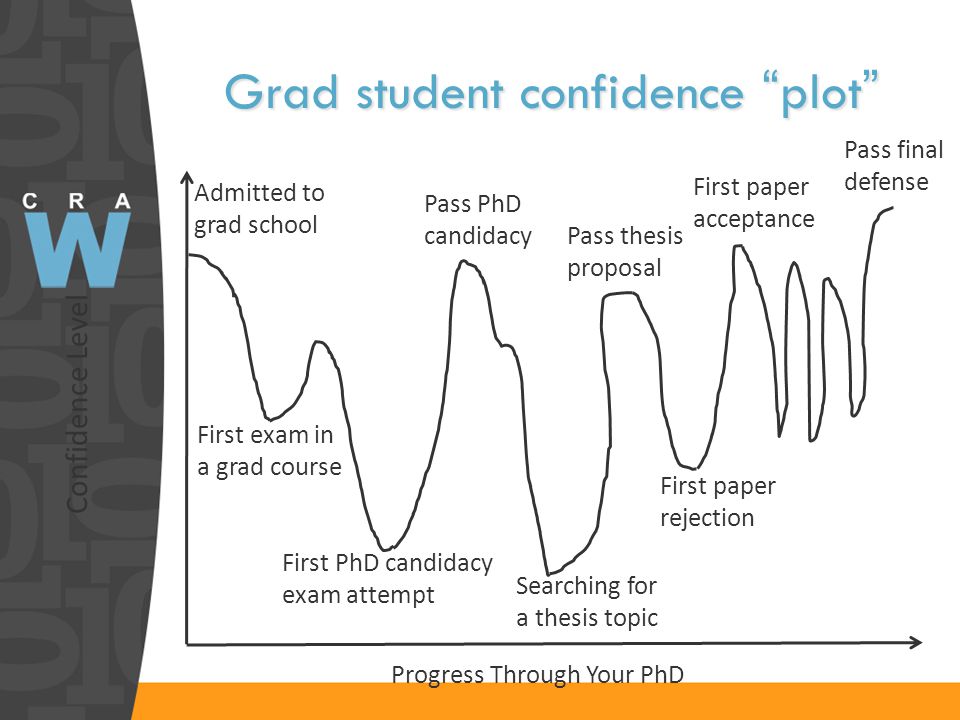

Toward the end of our conversation, I asked Roberts whether there’s anything he would change about his own personality. He admitted that he’s not always very detail-oriented (a.k.a. conscientious). He also regretted the anxiety (a.k.a. neuroticism) he experienced early in his career. Grad school was a “disconcerting experience,” he said: The son of a Marine and an artist, he felt that his classmates were all “brilliant and smart” and understood the world of academia better than he did.

He admitted that he’s not always very detail-oriented (a.k.a. conscientious). He also regretted the anxiety (a.k.a. neuroticism) he experienced early in his career. Grad school was a “disconcerting experience,” he said: The son of a Marine and an artist, he felt that his classmates were all “brilliant and smart” and understood the world of academia better than he did.

I was struck by how similar his story sounded to my own. My parents are from the Soviet Union and barely understand my career in journalism. I went to crappy public schools and a little-known college. I’ve notched every minor career achievement through night sweats and meticulous emails and aching computer shoulders. Neuroticism had kept my inner fire burning, but now it was suffocating me with its smoke.

To begin my transformation, I called Nathan Hudson, a psychology professor at Southern Methodist University who created a tool to help people alter their personality. For a 2019 paper, Hudson and three other psychologists devised a list of “challenges” for students who wanted to change their traits. For, say, increased extroversion, a challenge would be to “introduce yourself to someone new.” Those who completed the challenges experienced changes in their personality over the course of the 15-week study, Hudson found. “Faking it until you make it seems to be a viable strategy for personality change,” he told me.

For, say, increased extroversion, a challenge would be to “introduce yourself to someone new.” Those who completed the challenges experienced changes in their personality over the course of the 15-week study, Hudson found. “Faking it until you make it seems to be a viable strategy for personality change,” he told me.

But before I could tinker with my personality, I needed to find out exactly what that personality consisted of. So I logged on to a website Hudson had created and took a personality test, answering dozens of questions about whether I liked poetry and parties, whether I acted “wild and crazy,” whether I worked hard. “I radiate joy” got a “strongly disagree.” I disagreed that “we should be tough on crime” and that I “try not to think about the needy.” I had to agree, but not strongly, that “I believe that I am better than others.”

I scored in the 23rd percentile on extroversion—“very low,” especially when it came to being friendly or cheerful. Meanwhile, I scored “very high” on conscientiousness and openness and “average” on agreeableness, my high level of sympathy for other people making up for my low level of trust in them. Finally, I came to the source of half my breakups, 90 percent of my therapy appointments, and most of my problems in general: neuroticism. I’m in the 94th percentile—“extremely high.”

Finally, I came to the source of half my breakups, 90 percent of my therapy appointments, and most of my problems in general: neuroticism. I’m in the 94th percentile—“extremely high.”

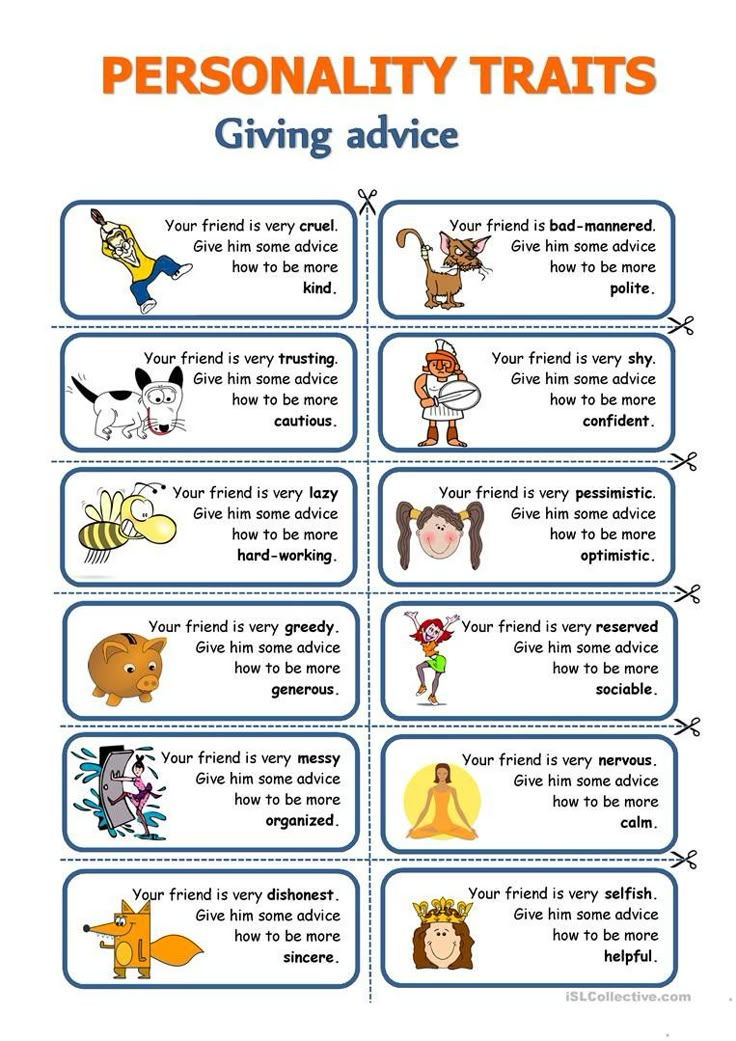

I prescribed myself the same challenges that Hudson had given his students. To become more extroverted, I would meet new people. To decrease neuroticism, I would meditate often and make gratitude lists. To increase agreeableness, the challenges included sending supportive texts and cards, thinking more positively about people who frustrate me, and, regrettably, hugging. In addition to completing Hudson’s challenges, I decided to sign up for improv in hopes of increasing my extroversion and reducing my social anxiety. To cut down on how pissed off I am in general, and because I’m an overachiever, I also signed up for an anger-management class.

Hudson’s findings on the mutability of personality seem to endorse the ancient Buddhist idea of “no-self”—no core “you.” To believe otherwise, the sutras say, is a source of suffering. Similarly, Brian Little writes that people can have “multiple authenticities”—that you can sincerely be a different person in different situations. He proposes that people have the ability to temporarily act out of character by adopting “free traits,” often in the service of an important personal or professional project. If a shy introvert longs to schmooze the bosses at the office holiday party, they can grab a canapé and make the rounds. The more you do this, Little says, the easier it gets.

Similarly, Brian Little writes that people can have “multiple authenticities”—that you can sincerely be a different person in different situations. He proposes that people have the ability to temporarily act out of character by adopting “free traits,” often in the service of an important personal or professional project. If a shy introvert longs to schmooze the bosses at the office holiday party, they can grab a canapé and make the rounds. The more you do this, Little says, the easier it gets.

Staring at my test results, I told myself, This will be fun! After all, I had changed my personality before. In high school, I was shy, studious, and, for a while, deeply religious. In college, I was fun-loving and boy-crazy. Now I’m a basically hermetic “pressure addict,” as one former editor put it. It was time for yet another me to make her debut.

Ideally, in the end I would be happy, relaxed, personable. The screams of angry sources, the failure of my boyfriend to do the tiniest fucking thing—they would be nothing to me. I would finally understand what my therapist means when she says I should “just observe my thoughts and let them pass without judgment.” I made a list of the challenges and attached them to my nightstand, because I’m very conscientious.

I would finally understand what my therapist means when she says I should “just observe my thoughts and let them pass without judgment.” I made a list of the challenges and attached them to my nightstand, because I’m very conscientious.

Immediately I encountered a problem: I don’t like improv. It’s basically a Quaker meeting in which a bunch of office workers sit quietly in a circle until someone jumps up, points toward a corner of the room, and says, “I think I found my kangaroo!” My vibe is less “yes, and” and more “well, actually.” When I told my boyfriend what I was up to, he said, “You doing improv is like Larry David doing ice hockey.”

I was also scared out of my mind. I hate looking silly, and that’s all improv is. The first night, we met in someone’s townhouse in Washington, D.C., in a room that was, for no discernible reason, decorated with dozens of elephant sculptures. Right after the instructor said, “Let’s get started,” I began hoping that someone would grab one and knock me unconscious.

That didn’t happen, so instead I played a game called Zip Zap Zop, which involved making lots of eye contact while tossing around an imaginary ball of energy, with a software engineer, two lawyers, and a guy who works on Capitol Hill. Then we pretended to be traveling salespeople peddling sulfuric acid. If someone had walked in on us, they would have thought we were insane. And yet I didn’t hate it. I decided I could think of being funny and spontaneous as a kind of intellectual challenge. Still, when I got home, I unwound by drinking one of those single-serving wines meant for petite female alcoholics.

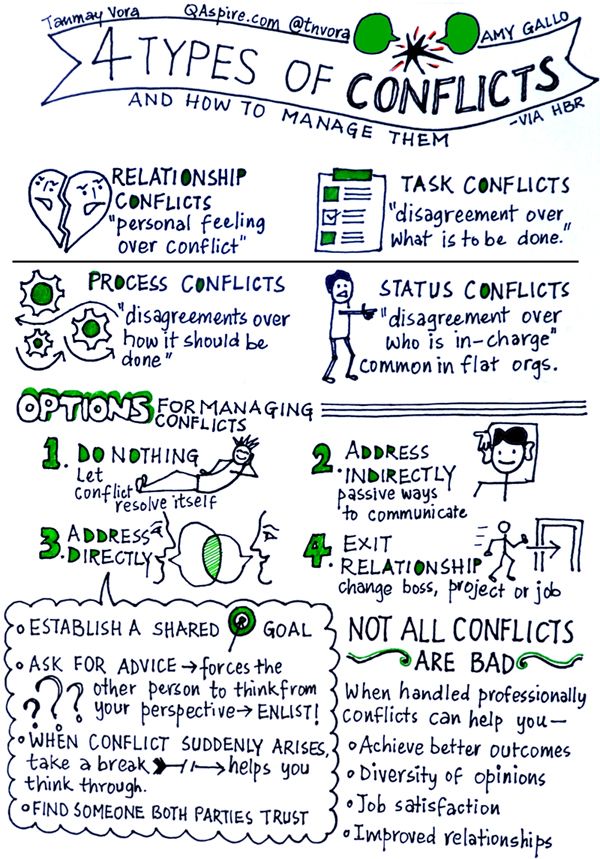

A few days later, I logged in to my first Zoom anger-management class. Christian Jarrett, a neuroscientist and the author of Be Who You Want, writes that spending quality time with people who are dissimilar to you increases agreeableness. And the people in my anger-management class did seem pretty different from me. Among other things, I was the only person who wasn’t court-ordered to be there.

We took turns sharing how anger has affected our lives. I said it makes my relationship worse—less like a romantic partnership and more like a toxic workplace. Other people worried that their anger was hurting their family. One guy shared that he didn’t understand why we were talking about our feelings when kids in China and Russia were learning to make weapons, which I deemed an interesting point, because you’re not allowed to criticize others in anger management.

The sessions—I went to six—mostly involved reading worksheets together, which was tedious, but I did learn a few things. Anger is driven by expectations. If you think you’re going to be in an anger-inducing situation, one instructor said, try drinking a cold can of Coke, which may stimulate your vagus nerve and calm you down. A few weeks in, I had a rough day, my boyfriend gave me some stupid suggestions, and I yelled at him. Then he said I’m just like my dad, which made me yell more. When I shared this in anger management, the instructors said I should be clearer about what I need from him when I’m in a bad mood—which is listening, not advice.

All the while, I had been working on my neuroticism, which involved making a lot of gratitude lists. Sometimes it came naturally. As I drove around my little town one morning, I thought about how grateful I was for my boyfriend, and how lonely I had been before I met him, even in other relationships. Is this gratitude? I wondered. Am I doing it?

What is personality, anyway, and where does it come from?

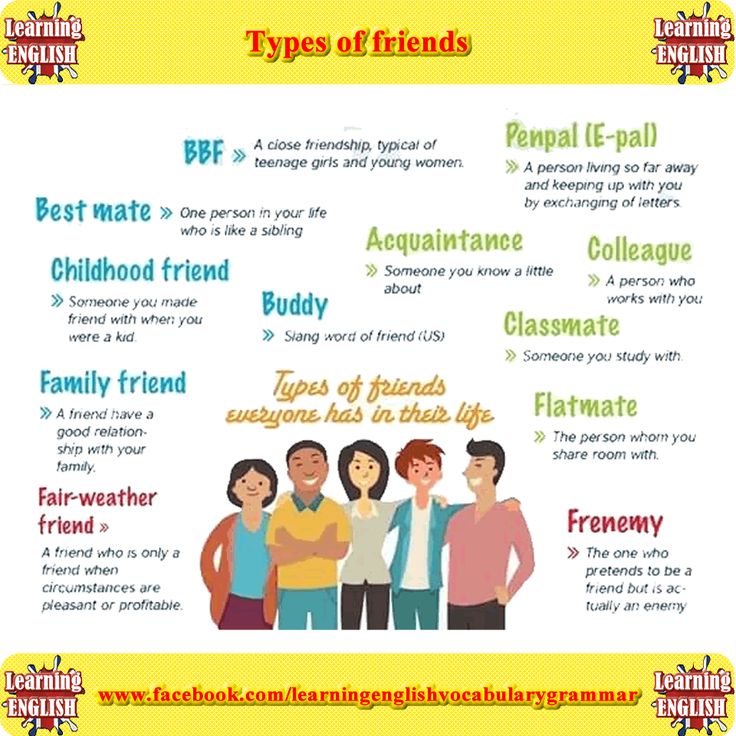

Contrary to conventional wisdom about bossy firstborns and peacemaking middles, birth order doesn’t influence personality. Nor do our parents shape us like lumps of clay. If they did, siblings would have similar dispositions, when they often have no more in common than strangers chosen off the street. Our friends do influence us, though, so one way to become more extroverted is to befriend some extroverts. Your life circumstances also have an effect: Getting rich can make you less agreeable, but so can growing up poor with high levels of lead exposure.

A common estimate is that about 30 to 50 percent of the differences between two people’s personalities are attributable to their genes. But just because something is genetic doesn’t mean it’s permanent. Those genes interact with one another in ways that can change how they behave, says Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas. They also interact with your environment in ways that can change how you behave. For example: Happy people smile more, so people react more positively to them, which makes them even more agreeable. Open-minded adventure seekers are more likely to go to college, where they grow even more open-minded.

But just because something is genetic doesn’t mean it’s permanent. Those genes interact with one another in ways that can change how they behave, says Kathryn Paige Harden, a behavioral geneticist at the University of Texas. They also interact with your environment in ways that can change how you behave. For example: Happy people smile more, so people react more positively to them, which makes them even more agreeable. Open-minded adventure seekers are more likely to go to college, where they grow even more open-minded.

Harden told me about an experiment in which mice that were genetically similar and reared in the same conditions were moved into a big cage where they could play with one another. Over time, these very similar mice developed dramatically different personalities. Some became fearful, others sociable and dominant. Living in Mouseville, the mice carved out their own ways of being, and people do that too. “We can think of personality as a learning process,” Harden said. “We learn to be people who interact with our social environments in a certain way.”

“We can think of personality as a learning process,” Harden said. “We learn to be people who interact with our social environments in a certain way.”

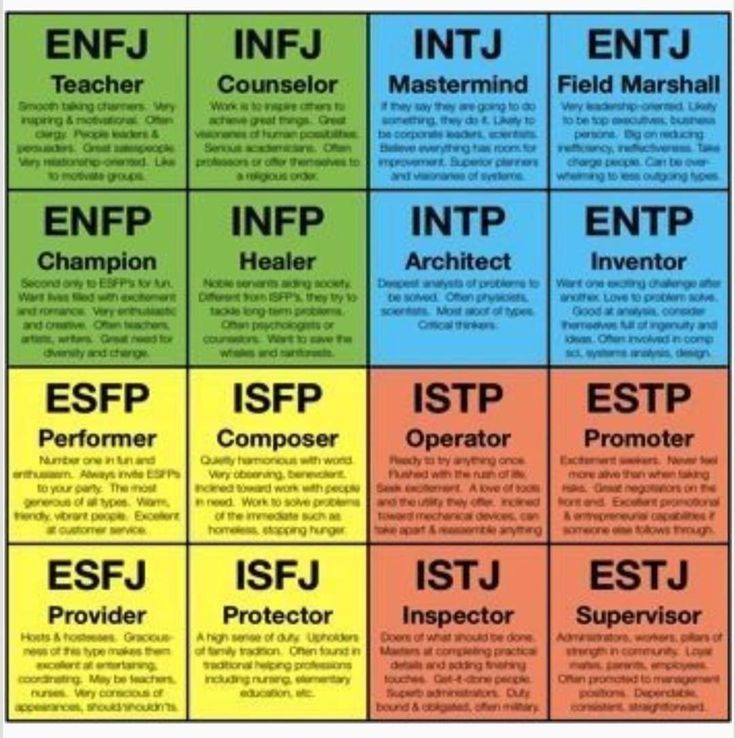

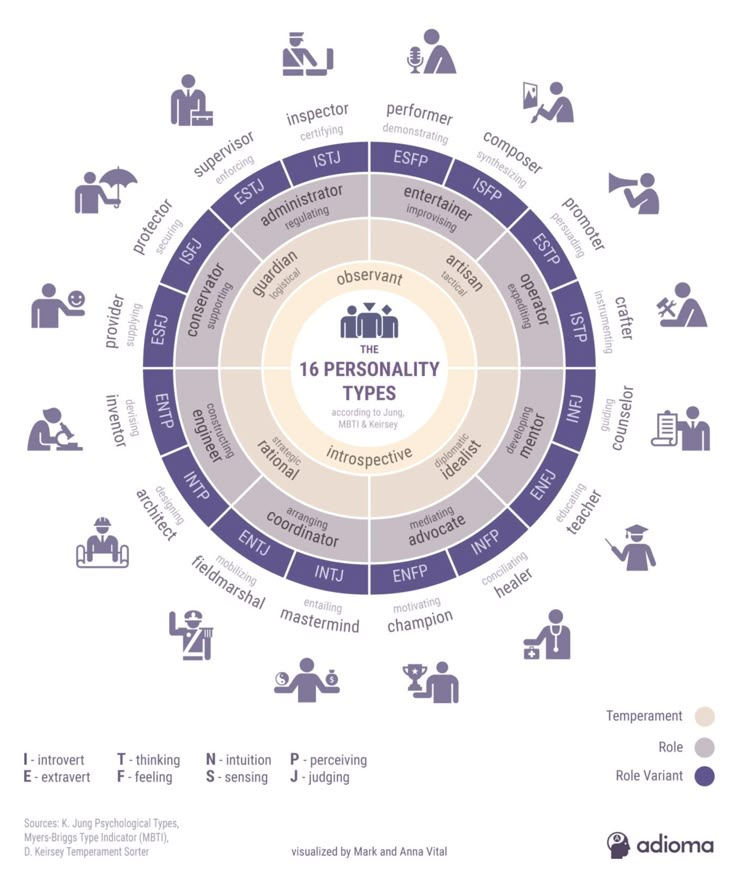

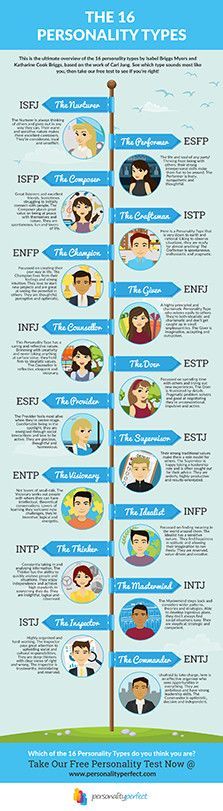

This more fluid understanding of personality is a departure from earlier theories. A 1914 best seller called The Eugenic Marriage (which is exactly as offensive as it sounds) argued that it is not possible to change a child’s personality “one particle after conception takes place.” In the 1920s, the psychoanalyst Carl Jung posited that the world consists of different “types” of people—thinkers and feelers, introverts and extroverts. (Even Jung cautioned, though, that “there is no such thing as a pure extravert or a pure introvert. Such a man would be in the lunatic asylum.”) Jung’s rubric captured the attention of a mother-daughter duo, Katharine Briggs and Isabel Briggs Myers, neither of whom had any formal scientific training. As Merve Emre describes in The Personality Brokers, the pair seized on Jung’s ideas to develop that staple of Career Day, the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator. But the test is virtually meaningless. Most people aren’t ENTJs or ISFPs; they fall between categories.

But the test is virtually meaningless. Most people aren’t ENTJs or ISFPs; they fall between categories.

Over the years, poor parenting has been a popular scapegoat for bad personalities. Alfred Adler, a prominent turn-of-the-20th-century psychologist, blamed mothers, writing that “wherever the mother-child relationship is unsatisfactory, we usually find certain social defects in the children.” A few scholars attributed the rise of Nazism to strict German parenting that produced hateful people who worshipped power and authority. But maybe any nation could have embraced a Hitler: It turns out that the average personalities of different countries are fairly similar. Still, the belief that parents are to blame persists, so much so that Roberts closes the course he teaches at the University of Illinois by asking students to forgive their moms and dads for whatever personality traits they believe were instilled or inherited.

Not until the 1950s did researchers acknowledge people’s versatility—that we can reveal new faces and bury others. “Everyone is always and everywhere, more or less consciously, playing a role,” the sociologist Robert Ezra Park wrote in 1950. “It is in these roles that we know each other; it is in these roles that we know ourselves.”

“Everyone is always and everywhere, more or less consciously, playing a role,” the sociologist Robert Ezra Park wrote in 1950. “It is in these roles that we know each other; it is in these roles that we know ourselves.”

Around this time, a psychologist named George Kelly began prescribing specific “roles” for his patients to play. Awkward wallflowers might go socialize in nightclubs, for example. Kelly’s was a rhapsodic view of change; at one point he wrote that “all of us would be better off if we set out to be something other than what we are.” Judging by the reams of self-help literature published each year, this is one of the few philosophies all Americans can get behind.

About six weeks in, my adventures in extroversion were going better than I’d anticipated. Intent on talking to strangers at my friend’s wedding, I approached a group of women and told them the story of how my boyfriend and I had met—I moved into his former room in a group house—which they deemed the “story of the night. ” On the winds of that success, I tried to talk to more strangers, but soon encountered the common wedding problem of Too Drunk to Talk to People Who Don’t Know Me.

” On the winds of that success, I tried to talk to more strangers, but soon encountered the common wedding problem of Too Drunk to Talk to People Who Don’t Know Me.

For more advice on becoming an extrovert, I reached out to Jessica Pan, a writer in London and the author of the book Sorry I’m Late, I Didn’t Want to Come. Pan was an extreme introvert, someone who would walk into parties and immediately walk out again. At the start of the book, she resolved to become an extrovert. She ran up to strangers and asked them embarrassing questions. She did improv and stand-up comedy. She went to Budapest and made a friend. Folks, she networked.

Illustration by Gabriela Pesqueira; photographs by Devin Christopher for The AtlanticIn the process, Pan “flung open the doors” to her life, she writes. “Having the ability to morph, to change, to try on free traits, to expand or contract at will, offers me an incredible feeling of freedom and a source of hope.” Pan told me that she didn’t quite become a hard-core extrovert, but that she would now describe herself as a “gregarious introvert. ” She still craves alone time, but she’s more willing to talk to strangers and give speeches. “I will be anxious, but I can do it,” she said.

” She still craves alone time, but she’s more willing to talk to strangers and give speeches. “I will be anxious, but I can do it,” she said.

I asked her for advice on making new friends, and she told me something a “friendship mentor” once told her: “Make the first move, and make the second move, too.” That means you sometimes have to ask a friend target out twice in a row—a strategy I had thought was gauche.

I practiced by trying to befriend some female journalists I admired but had been too intimidated to get to know. I messaged someone who seemed cool based on her writing, and we arranged a casual beers thing. But on the night we were supposed to get together, her power went out, trapping her car in her garage.

Instead, I caught up with an old friend by phone, and we had one of those conversations you can have only with someone you’ve known for years, about how the people who are the worst remain the worst, and how all of your issues remain intractable, but good on you for sticking with it. By the end of our talk, I was high on agreeable feelings. “Love you, bye!” I said as I hung up.

By the end of our talk, I was high on agreeable feelings. “Love you, bye!” I said as I hung up.

“LOL,” she texted. “Did you mean to say ‘I love you’?”

Who was this new Olga?

For my gratitude journaling, I purchased a notebook whose cover said, “Gimme those bright sunshiney vibes.” I soon noticed, though, that my gratitude lists were repetitive odes to creature comforts and entertainment: Netflix, yoga, TikTok, leggings, wine. After I cut my finger cooking, I expressed gratitude for the dictation software that let me write without using my hands, but then my finger healed. “Very hard to come up with new things to say,” I wrote one day.

I find expressing gratitude unnatural, because Russians believe doing so will provoke the evil eye; our God doesn’t like too much bragging. The writer Gretchen Rubin hit a similar wall when keeping a gratitude journal for her book The Happiness Project. “It had started to feel forced and affected,” she wrote, making her annoyed rather than grateful.

I was also supposed to be meditating, but I couldn’t. On almost every page, my journal reads, “Meditating sucks!” I tried a guided meditation that involved breathing with a heavy book on my stomach—I chose Nabokov’s Letters to Véra—only to find that it’s really hard to breathe with a heavy book on your stomach.

I tweeted about my meditation failures, and Dan Harris, a former Good Morning America weekend anchor, replied: “The fact that you’re noticing the thoughts/obsessions is proof that you are doing it correctly!” I picked up Harris’s book 10% Happier, which chronicles his journey from a high-strung reporter who had a panic attack on air to a high-strung reporter who meditates a lot. At one point, he was meditating for two hours a day.

When I called Harris, he said that it’s normal for meditation to feel like “training your mind to not be a pack of wild squirrels all the time.” Very few people actually clear their minds when they’re meditating. The point is to focus on your breath for however long you can—even if it’s just a second—before you get distracted. Then do it over and over again. Occasionally, when Harris meditates, he still “rehearses some grand, expletive-filled speech I’m gonna deliver to someone who’s wronged me.” But now he can return to his breath more quickly, or just laugh off the obsessing.

Then do it over and over again. Occasionally, when Harris meditates, he still “rehearses some grand, expletive-filled speech I’m gonna deliver to someone who’s wronged me.” But now he can return to his breath more quickly, or just laugh off the obsessing.

Harris suggested that I try loving-kindness meditation, in which you beam affectionate thoughts toward yourself and others. This, he said, “sets off what I call a gooey upward spiral where, as your inner weather gets balmier, your relationships get better.” In his book, Harris describes meditating on his 2-year-old niece. As he thought about her “little feet” and “sweet face with her mischievous eyes,” he started crying uncontrollably.

What a pussy, I thought.

I downloaded Harris’s meditation app and pulled up a loving-kindness session by the meditation teacher Sharon Salzberg. She had me repeat calming phrases like “May you be safe” and “May you live with ease.” Then she asked me to envision myself surrounded by a circle of people who love me, radiating kindness toward me. I pictured my family, my boyfriend, my friends, my former professors, emitting beneficence from their bellies like Care Bears. “You’re good; you’re okay,” I imagined them saying. Before I knew what was happening, I had broken into sobs.

I pictured my family, my boyfriend, my friends, my former professors, emitting beneficence from their bellies like Care Bears. “You’re good; you’re okay,” I imagined them saying. Before I knew what was happening, I had broken into sobs.

After two brutal years, people may be wondering if surviving a pandemic has at least improved their personality, making them kinder and less likely to sweat the small stuff. “Post-traumatic growth,” or the idea that stressful events can make us better people, is the subject of one particularly cheery branch of psychology. Some big events do seem to transform personality: People grow more conscientious when they start a job they like, and they become less neurotic when they enter a romantic relationship. But in general, it’s not the event that changes your personality; it’s the way you experience it. And the evidence that people grow as a result of difficulty is mixed. Studies of post-traumatic growth are tainted by the fact that people like to say they got something out of their trauma.

It’s a nice thing to believe about yourself—that, pummeled by misfortune, you’ve emerged stronger than ever. But these studies are mostly finding that people prefer to look on the bright side.

In more rigorous studies, evidence of a transformative effect fades. Damian, the University of Houston psychologist, gave hundreds of students at the university a personality test a few months after Hurricane Harvey hit, in November 2017, and repeated the test a year later. The hurricane was devastating: Many students had to leave their homes; others lacked food, water, or medical care for weeks. Damian found that her participants hadn’t grown, and they hadn’t shriveled. Overall they stayed the same. Other research shows that difficult times prompt us to fall back on tried-and-true behaviors and traits, not experiment with new ones.

Growth is also a strange thing to ask of the traumatized. It’s like turning to a wounded person and demanding, “Well, why didn’t you grow, you lazy son of a bitch?” Roberts said. Just surviving should be enough.

Just surviving should be enough.

It may be impossible to know how the pandemic will change us on average, because there is no “average.” Some people have struggled to keep their jobs while caring for children; some have lost their jobs; some have lost loved ones. Others have sat at home and ordered takeout. The pandemic probably hasn’t changed you if the pandemic itself hasn’t felt like that much of a change.

I blew off anger management one week to go see Kesha in concert. I justified it because the concert was a group activity, plus she makes me happy. The next time the class gathered, we talked about forgiveness, which Child Weapons Guy was not big on. He said that rather than forgive his enemies, he wanted to invite them onto a bridge and light the bridge on fire. I thought he should get credit for being honest—who hasn’t wanted to light all their enemies on fire?—but the anger-management instructors started to look a little angry themselves.

In the next session, Child Weapons Guy seemed contrite, saying he realized that he uses his anger to deal with life, which was a bigger breakthrough than anyone expected. I was also praised, for an unusually tranquil trip home to see my parents, which my instructors said was an example of good “expectation management.”

I was also praised, for an unusually tranquil trip home to see my parents, which my instructors said was an example of good “expectation management.”

Meanwhile, my social life was slowly blooming. A Twitter acquaintance invited me and a few other strangers to a whiskey tasting, and I said yes even though I don’t like whiskey or strangers. At the bar, I made some normal-person small talk before having two sips of alcohol and wheeling the conversation around to my personal topic of interest: whether I should have a baby. The woman who organized the tasting, a self-proclaimed extrovert, said people are always grateful to her for getting everyone to socialize. At first, no one wants to come, but people are always happy they did.

I thought perhaps whiskey could be my “thing,” and, to tick off another challenge from Hudson’s list, decided to go to a whiskey bar on my own one night and talk to strangers. I bravely steered my Toyota to a sad little mixed-use development and pulled up a stool at the bar. I asked the bartender how long it had taken him to memorize all the whiskeys on the menu. “Two months,” he said, and turned back to peeling oranges. I asked the woman sitting next to me how she liked her appetizer. “It’s good!” she said. This is awful! I thought. I texted my boyfriend to come meet me.

I asked the bartender how long it had taken him to memorize all the whiskeys on the menu. “Two months,” he said, and turned back to peeling oranges. I asked the woman sitting next to me how she liked her appetizer. “It’s good!” she said. This is awful! I thought. I texted my boyfriend to come meet me.

The larger threat on my horizon was the improv showcase—a free performance for friends and family and whoever happened to jog past Picnic Grove No. 1 in Rock Creek Park. The night before, I kept jolting awake from intense, improv-themed nightmares. I spent the day grimly watching old Upright Citizens Brigade shows on YouTube. “I’m nervous on your behalf,” my boyfriend said when he saw me clutching a throw pillow like a life preserver.

To describe an improv show is to unnecessarily punish the reader, but it went fairly well. Along with crushing anxiety, my brain courses with an immigrant kid’s overwhelming desire to do whatever people want in exchange for their approval. I improvised like they were giving out good SAT scores at the end. On the drive home, my boyfriend said, “Now that I’ve seen you do it, I don’t really know why I thought it’s something you wouldn’t do.”

I improvised like they were giving out good SAT scores at the end. On the drive home, my boyfriend said, “Now that I’ve seen you do it, I don’t really know why I thought it’s something you wouldn’t do.”

I didn’t know either. I vaguely remembered past boyfriends telling me that I’m insecure, that I’m not funny. But why had I been trying to prove them right? Surviving improv made me feel like I could survive anything, as bratty as that must sound to all my ancestors who survived the siege of Leningrad.

Finally, the day came to retest my personality and see how much I’d changed. I thought I felt hints of a mild metamorphosis. I was meditating regularly, and had had several enjoyable get-togethers with people I wanted to befriend. And because I was writing them down, I had to admit that positive things did, in fact, happen to me.

But I wanted hard data. This time, the test told me that my extroversion had increased, going from the 23rd percentile to the 33rd. My neuroticism decreased from “extremely high” to merely “very high,” dropping to the 77th percentile. And my agreeableness score … well, it dropped, from “about average” to “low.”

And my agreeableness score … well, it dropped, from “about average” to “low.”

I told Brian Little how I’d done. He said I likely did experience a “modest shift” in extroversion and neuroticism, but also that I might have simply triggered positive feedback loops. I got out more, so I enjoyed more things, so I went to more things, and so forth.

Why didn’t I become more agreeable, though? I had spent months dwelling on the goodness of people, devoted hours to anger management, and even sent an e-card to my mom. Little speculated that maybe by behaving so differently, I had heightened my internal sense that people aren’t to be trusted. Or I might have subconsciously bucked against all the syrupy gratitude time. That I had tried so hard and made negative progress—“I think it’s a bit of a hoot,” he said.

Perhaps it’s a relief that I’m not a completely new person. Little says that engaging in “free trait” behavior—acting outside your nature—for too long can be harmful, because you can start to feel like you are suppressing your true self. You end up feeling burned out or cynical.

You end up feeling burned out or cynical.

The key may not be in swinging permanently to the other side of the personality scale, but in balancing between extremes, or in adjusting your personality depending on the situation. “The thing that makes a personality trait maladaptive is not being high or low on something; it’s more like rigidity across situations,” Harden, the behavioral geneticist, told me.

“So it’s okay to be a little bitchy in your heart, as long as you can turn it off?” I asked her.

“People who say they’re never bitchy in their heart are lying,” she said.

Susan Cain, the author of Quiet and the world’s most famous introvert, seems reluctant to endorse the idea that introverts should try to be more outgoing. Over the phone, she wondered why I wanted to be more extroverted in the first place. Society often urges people to conform to the qualities extolled in performance reviews—punctual, chipper, gregarious. But there are upsides to being introspective, skeptical, and even a little neurotic. She said it’s possible that I didn’t change my underlying introversion, that I just acquired new skills. She thought I could probably maintain this new personality, so long as I kept doing the tasks that got me here.

But there are upsides to being introspective, skeptical, and even a little neurotic. She said it’s possible that I didn’t change my underlying introversion, that I just acquired new skills. She thought I could probably maintain this new personality, so long as I kept doing the tasks that got me here.

Hudson cautioned that personality scores can bounce around a bit from moment to moment; to be certain of my results, I ideally would have taken the test a number of times. Still, I felt sure that some change had taken place. A few weeks later, I wrote an article that made people on Twitter really mad. This happens to me once or twice a year, and I usually suffer a minor internal apocalypse. I fight the people on Twitter while crying, call my editor while crying, and Google How to become an actuary while crying. This time, I was stressed and angry, but I just waited it out.

This kind of modest improvement, I realized, is the goal of so much self-help material. Hours a day of meditation made Harris only 10 percent happier. My therapist is always suggesting ways for me to “go from a 10 to a nine on anxiety.” Some antidepressants make people feel only slightly less depressed, yet they take the drugs for years. Perhaps the real weakness of the “change your personality” proposition is that it implies incremental change isn’t real change. But being slightly different is still being different—the same you but with better armor.

My therapist is always suggesting ways for me to “go from a 10 to a nine on anxiety.” Some antidepressants make people feel only slightly less depressed, yet they take the drugs for years. Perhaps the real weakness of the “change your personality” proposition is that it implies incremental change isn’t real change. But being slightly different is still being different—the same you but with better armor.

The late psychologist Carl Rogers once wrote, “When I accept myself just as I am, then I can change,” and this is roughly where I’ve landed. Maybe I’m just an anxious little introvert who makes an effort to be less so. I can learn to meditate; I can talk to strangers; I can be the mouse who frolics through Mouseville, even if I never become the alpha. I learned to play the role of a calm, extroverted softy, and in doing so I got to know myself.

This article appears in the March 2022 print edition with the headline “My Personality Transplant.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

Personality Change | Psychology Today

Self-Reinvention

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

A personality features a collection of traits that make an individual distinct—traits such as extroversion, openness to new experiences, narcissism, or agreeableness, which some people exhibit more strongly than others. But just because a term like "disagreeable" describes someone well doesn't mean the person necessarily wants to be that way. Procrastinators may wish to become more conscientious; those inclined to gloominess may hope to be more optimistic; the shy may long to be the life of the party. Many people want to change some feature of their personality.

Personality trait measures tend to be fairly stable during adulthood, psychologists have found. Yet research does indicate that there is room for personal evolution, especially over long periods of time as an individual matures. And whether one receives a personality makeover or not, with a little sweat and some luck, it is possible to break out of old behavioral patterns and act more like the person one wants to be.

And whether one receives a personality makeover or not, with a little sweat and some luck, it is possible to break out of old behavioral patterns and act more like the person one wants to be.

Contents

- The Flexibility of Personality

- How to Change Your Personality

How Flexible Is Your Personality?

As consistent as a personality can remain from day to day, research indicates that the adult personality is more malleable than once believed. In studies, individuals do appear to change with age, on average—showing signs of maturation that are measurable through personality questionnaires. Deliberately trying to change one's personality is a different matter, but research has explored ways of doing that, too.

Is it possible to change your personality?

Probably. Extroversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability are all traits that one may be able to deliberately increase, research suggests, though it’s not yet known how permanent such changes are. They also seem to require active engagement in efforts to change—merely wanting to is likely not enough.

Extroversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness, and emotional stability are all traits that one may be able to deliberately increase, research suggests, though it’s not yet known how permanent such changes are. They also seem to require active engagement in efforts to change—merely wanting to is likely not enough.

Does personality change with age?

Yes, for many people, it does. Research suggests that people tend to become, for example, calmer and more socially sensitive, and less narcissistic, on average. The idea that agreeableness, conscientiousness, and emotional stability tend to increase with age has been called the “maturity principle.” At the same time, people show marked consistency in terms of how their personalities compare to those of their peers, so someone who is more narcissistic than most may remain so over the years.

How much can a person change?

What causes a change in personality?

Many factors may lead to changes in personality. Genetics influences the development of a person’s traits as they grow up, and personality researchers have argued that important life changes (such as getting married) and new social roles (such as a job) can alter personality traits as well. Research indicates that therapy can produce change, especially on the trait of neuroticism.

Genetics influences the development of a person’s traits as they grow up, and personality researchers have argued that important life changes (such as getting married) and new social roles (such as a job) can alter personality traits as well. Research indicates that therapy can produce change, especially on the trait of neuroticism.

How is mental illness related to personality?

Mental health is linked to multiple aspects of personality. The Big Five trait of neuroticism, in particular, has been associated with a variety of mental health conditions, including mood and anxiety disorders, substance use disorders, and certain personality disorders (including borderline personality disorder). Research also suggests that people with some kinds of mental illness, including depression, tend to be relatively low in conscientiousness and extraversion.

Can a brain injury change personality?

Although research is limited, it suggests that brain injury may influence personality. There is evidence, for example, that people who experience a serious head injury or stroke may show decreases in conscientiousness and extroversion.

There is evidence, for example, that people who experience a serious head injury or stroke may show decreases in conscientiousness and extroversion.

How to Change Your Personality

Interventions designed to get people to behave differently—such as by introducing oneself to new people, showing up early to an event, or other challenges—have, at least in experiments, seemed to move the needle on measures of personality traits. But such efforts may need to be consistent and sustained for (at least) a matter of weeks. Psychotherapy also seems to have the power to create positive personality change.

I want to be more extroverted. What should I do?

Engaging in regular social "challenges" might help. Students who wanted to become more extroverted and completed two or more psychologist-devised challenges a week tended to show increases in their questionnaire scores on extroversion over the course of a semester. The exercises ranged from simple steps like saying hello to a cashier or waving to someone who lived nearby, to more involved ones such as going to a Meet Up event or organizing a social outing.

The exercises ranged from simple steps like saying hello to a cashier or waving to someone who lived nearby, to more involved ones such as going to a Meet Up event or organizing a social outing.

How can you change a negative personality?

How can I become more conscientious?

Students who took on two or more conscientious-related challenges a week showed some gains in their scores on the trait over the course of a semester. These included tasks such as “Begin preparing for an event 10 minutes earlier than usual," "Set out your clothes the night before," and "Clean up the dishes as soon as you're done with them."

How can you tell whether your personality has changed?

There are a variety of personality tests, and some are available to the general public. Responding to a questionnaire that assesses the Big Five traits (such as the Big Five Inventory) at different points in time—or having someone else respond to questions about you on your behalf—may help you get a clearer sense of the extent to which your personality has changed. Such tests provide scores for each trait on a continuous scale.

Such tests provide scores for each trait on a continuous scale.

Is it ever too late to change your personality?

Personality is not set in stone. While research finds some long-term consistency in measures of different personality traits, it also suggests that change is possible even in old age.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

where to start to change your life - T & P

Programmer, investor and entrepreneur James Altucher, who has already launched several startups, published a very simple, useful and honest manual on TechCrunch for those who want to radically change their field of activity, but do not know where to begin. "Theories and Practices" translated the text of the article.

Here's the thing: I've been to zero a few times, I've come back to life a few times, I've done it over and over again. I started new careers. The people who knew me then don't know me now. Etc. nine0005

Etc. nine0005

I started my career from scratch several times. Sometimes, because my interests have changed. Sometimes because all the bridges were burned to the ground, and sometimes because I desperately needed money. And sometimes because I hated everyone at my previous job or they hated me.

There are other ways to reinvent yourself, so take my words with a grain of salt. This is what worked in my case. I've seen it work for about a hundred other people. According to interviews, according to letters that have been written to me over the past 20 years. You can try - or not. nine0005

With the right organization and planning, the home office is not a punishment but an opportunity. For business - to save resources, for employees - to get rid of the feeling that life is passing by. If you do not neglect the rules of the organization, learn management at a distance, use modern technologies and systems, you can set up an effective home office for employees in just one day. More about the BeeFREE solution from Beeline Business at the link.

1. Change never ends

Every day you rediscover yourself. You are always on the move. But every day you decide where exactly you are moving: forward or backward.

2. Start with a clean slate

All your past labels are futile. Have you been a doctor? An Ivy League graduate? Owned millions? Did you have a family? Nobody cares. You have lost everything. You are zero. Don't try to say that you are something big.

3. You need a mentor

Otherwise you will sink. Someone has to show you how to move and breathe. But don't worry about looking for a mentor (see below). nine0005

4. Three types of mentors

Direct. Someone who is ahead of you, who will show you how he got it. What does "this" mean? Wait. By the way, the mentors don't look like Jackie Chan's character in The Karate Kid. Most mentors will hate you.

Indirect. Books. Movies. You can get 90% of the instructions from books and other materials. 200-500 books are equal to a good mentor. When people ask me, “What is a good book to read?” — I don't know what to answer them. There are 200-500 good books worth reading. I would turn to inspirational books. Whatever you believe, strengthen your beliefs with daily reading. nine0005

When people ask me, “What is a good book to read?” — I don't know what to answer them. There are 200-500 good books worth reading. I would turn to inspirational books. Whatever you believe, strengthen your beliefs with daily reading. nine0005

Anything can be a mentor. If you are nobody and want to re-create yourself, everything you look at can become a metaphor for your desires and goals. The tree you see, with its roots beyond sight and the groundwater that feeds it, is a metaphor for programming if you tie the dots together. And everything you look at will "connect the dots".

5. Don't worry if nothing fascinates you

You care about your health. Start with him. Take small steps. You don't need passion to succeed. Do your job with love, and success will become a natural symptom. nine0005

© Andrew B. Myers

6. Time to re-create yourself: five years

Here is a description of those five years.

First year: you flounder and read everything and just start doing something.

Year 2: You know who you need to talk to and maintain working relationships with. You do something every day. You finally understand what the map of your own game of Monopoly looks like.

Third year: You are good enough to start making money. But for now, perhaps not enough to earn a living. nine0005

Fourth year: You provide for yourself well.

Year five: you make a fortune.

Sometimes I got frustrated during the first four years. I asked myself, "Why hasn't this happened yet?" - He beat the wall with his fist and broke his arm. It's okay, just keep going. Or stop and choose a new field of activity. It does not matter. Someday you will die, and then it will be really difficult to change.

7. If you do it too fast or too slow, something is wrong

A good example is Google.

8. It's not about money

But money is a good measure. When people say, "It's not about the money," they need to be sure they have some other unit of measure. "How about just doing what you love?" There will be many days ahead when you don't like what you do. If you are doing it out of pure love, it will take much more than five years. Happiness is just a positive reaction from your brain. Some days you will be unhappy. Your brain is just a tool, it does not define who you are. nine0005

"How about just doing what you love?" There will be many days ahead when you don't like what you do. If you are doing it out of pure love, it will take much more than five years. Happiness is just a positive reaction from your brain. Some days you will be unhappy. Your brain is just a tool, it does not define who you are. nine0005

9. When can you say, “I do X”? When does X become your new profession?

Today.

10. When can I start practicing X?

Today. If you want to paint, buy canvas and paints today, start buying 500 books one by one and paint pictures. If you want to write, do the following three things:

- read

- write

- take your favorite author and print his best story word by word. Ask yourself why he wrote each word. Let him be your mentor today. nine0005

If you want to start your own business, start coming up with an idea for a business. Rebuilding yourself starts today. Every day.

11. When will I earn money?

In a year, you will put 5,000-7,000 hours into this business. That's good enough to get you into the top 200-300 in the world in any major. Getting into the top 200 almost always provides a livelihood. By the third year, you will understand how to make money. By the fourth, you will be able to increase turnover and provide for yourself. Some stop there. nine0005

That's good enough to get you into the top 200-300 in the world in any major. Getting into the top 200 almost always provides a livelihood. By the third year, you will understand how to make money. By the fourth, you will be able to increase turnover and provide for yourself. Some stop there. nine0005

12. By the fifth year, you will be in the top 30-50, so you can make a fortune.

© Benjamin Yeager

13. How do I know if it's mine?

Any area in which you can read 500 books. Go to the bookstore and find her. If after three months you get bored, go to the bookstore again. Getting rid of illusions is normal, this is the meaning of defeat. Success is better than failure, but defeats give us the most important lessons. Very important: do not rush. During your interesting life, you can change yourself many times. And fail many times. It's fun too. These attempts will turn your life into a story book, not a textbook. Some people want their life to be a textbook. Mine is a story book, good or bad. Therefore, changes occur every day. nine0005

Mine is a story book, good or bad. Therefore, changes occur every day. nine0005

14. The decisions you make today will be in your biography tomorrow

Make interesting decisions and you will have an interesting biography.

15. The decisions you make today will become part of your biology

16. What if I like something exotic? Biblical archeology or 11th century wars?

Repeat the above steps and by the fifth year you will be rich. We don't know how. There is no need to look for the end of the path when you are only taking the first steps. nine0005

17. What if my family wants me to become an accountant?

How many years of your life did you promise to give to your family? Ten? All life? Then wait for the next life. You choose.

Choose freedom, not family. Freedom, not prejudice. Freedom, not government. Freedom, not the satisfaction of other people's requests. Then you will satisfy yours.

18. My mentor wants me to follow his path

This is normal. Learn his way. Then do it your way. Sincerely. nine0005

Learn his way. Then do it your way. Sincerely. nine0005

Luckily no one puts a gun to your head. Then you would have to comply with his demands until he lowers the gun.

19. My husband (wife) is worried: who will take care of our children?

A person who changes himself always finds free time. Part of changing yourself is finding moments and reshaping them the way you would like to use them.

20. What if my friends think I'm crazy?

Who are these friends?

21. What if I want to be an astronaut? nine0013

This is not changing yourself. This is a specific profession. If you like space, there are many professions. Richard Branson wanted to be an astronaut and created Virgin Galactic.

22. What if I enjoy drinking and hanging out with friends?

Read this post again in a year.

23. What if I'm busy? Am I cheating on my spouse or betraying my partner?

Read this post again in two or three years, when you are broke, without a job and everyone will turn their backs on you. nine0005

nine0005

24. What if I can't do anything at all?

Read point 2 again.

25. What if I don't have a diploma or it's useless?

Read item 2 again.

26. What if I need to focus on paying off a mortgage or other loan?

Read item 19 again.

27. Why do I feel like an outsider all the time?

Albert Einstein was an outsider. None of the people in power would have hired him. Everyone feels like an impostor sometimes. The greatest creativity is born out of skepticism. nine0005

© Paul Octavious

28. I can't read 500 books. Name one book to read for inspiration

Then you can just give up.

29. What if I'm too sick to change myself?

The change will boost the production of beneficial substances in your body: serotonin, dopamine, oxytocin. Move forward, and you may not get well at all, but you will become healthier. Don't use health as an excuse.

Finally, rebuild your health first. Sleep more. Eat better. Go in for sports. These are the key steps to change. nine0005

Sleep more. Eat better. Go in for sports. These are the key steps to change. nine0005

30. What if my partner set me up and I'm still suing him?

Quit litigation and never think about him again. Half the problem was you.

31. What if they put me in jail?

Great. Reread point 2. Read more books in prison.

32. What if I am a timid person?

Make weakness your strength. Introverts are better at listening and concentrating, they know how to arouse sympathy.

33. What if I can't wait five years? nine0013

If you plan to be alive in five years, you can start today.

34. How to make contacts?

Make concentric circles. You must be in the middle. The next circle is friends and family. Then there are online communities. Then - people whom you know from informal meetings and tea parties. Then - conference participants and opinion leaders in their field. Then there are mentors. Then there are customers and those who make money. Start making your way through these circles.

Start making your way through these circles.

35. What if my ego gets in the way of what I do? nine0013

In six months or a year you will return to point 2.

36. What if I am passionate about two things at once? And I can't choose?

Combine them and you will be the best in the world for this combination.

37. What if I'm so passionate that I want to teach others what I'm learning myself?

Read lectures on YouTube. Start with a one person audience and see if it grows.

38. What if I want to earn money in my sleep?

In your fourth year, start outsourcing what you do. nine0005

39. How do you find mentors and experts?

Once you have enough knowledge (after 100-200 books), write 10 ideas for 20 different potential mentors.

None of them will answer you. Write 10 more ideas for 20 new mentors. Repeat this every week.

Create a mailing list for everyone who hasn't replied to you. Repeat until someone answers. Write a blog about learning something. Build a community where you can become an expert.

Write a blog about learning something. Build a community where you can become an expert.

© Andrew B. Myers

40. What if I can't come up with ideas?

Then practice this. The mental muscles tend to atrophy. They need to be trained.

It will be difficult for me to reach my toes if I don't exercise every day. I have to do this exercise every day for some time before this pose comes easily to me. Don't expect good ideas to come from day one. nine0005

41. What else to read?

AFTER books you can read websites, forums, magazines. But most of them are garbage.

42. What if I do everything you say, but it still doesn't seem to work?

It will work. Just wait. Keep changing yourself every day.

Don't try to find the end of the road. You can't see it in the fog. But you can see the next step, and you will understand that if you take it, you will eventually reach the end of the path.

43. What if I start feeling down? nine0013

Sit in silence for an hour a day. You need to get back to your essence.

You need to get back to your essence.

If you think this sounds stupid, don't do it. Move on with your depression.

44. And if there is no time to sit in silence?

Then sit in silence for two hours a day. This is not meditation. You just have to sit.

45. What if I get scared?

Sleep 8-9 hours a day and never gossip. Sleep is the first secret to good health. Not the only one, but the first. Some people write to me that four hours of sleep is enough for them, or that in their country those who sleep a lot are considered lazy. These people will fail and die young. nine0005

When it comes to gossip, our brains are biologically programmed to have 150 friends. And when you chat with one of your friends, you can gossip about one of the other 150. And if you don't have 150 friends, then the brain will want to read gossip magazines until it seems to it that it has 150 friends.

Don't be as stupid as your brain.

46. And if everything seems to me that I will never succeed?

Practice gratitude for 10 minutes a day. Don't suppress your fear. Notice your anger. nine0005

Don't suppress your fear. Notice your anger. nine0005

But also allow yourself to be grateful for what you have. Anger never inspires, but gratitude never inspires. Gratitude is the bridge between your world and the parallel universe where all creative ideas live.

47. What if I constantly have to deal with some personal squabbles?

Find other people to be around.

A person who changes himself will constantly meet people who try to suppress him. The brain is afraid of change - it can be unsafe. Biologically, the brain wants you to be safe, and change is a risk. So your brain will give you people trying to stop you. nine0005

Learn to say no.

48. What if I'm happy at my office job?

Good luck.

49. Why should I trust you? You have been defeated so many times

Don't trust me.

50. Will you be my mentor?

You have already read this post.

The original article can be read here.

Follow us on Facebook, VK, Twitter, Instagram, Telegram (@tandp_ru) and Yandex. Zen.

Zen.

The only way to change your life for the better

Very often, when it seems to us that in life we lack the courage to change it, in fact, we lack patience and calmness, the founder of the Kommersant publishing house Vladimir Yakovlev is sure. About how to achieve real changes in life, he talks with his new video column.

Finished reading here

I am a coward. And always have been. And I don't even try to hide it. You know, every time I was going to radically change my life for the better, I was terribly afraid to do it. But I gathered my will into a fist and found the strength to overcome my fear. nine0005

And you know what? As a result, I almost always found out that I was absolutely not afraid in vain.

“I need to radically change my life for the better!” This phrase has been my mantra for many years.

I changed, left, moved, quit and started again. But no matter what I did, I invariably managed to solve the problem in half. I was able to radically change my life. But to improve it thanks to this - no.

You know, it often seems that in order to change your life, you just need to make a decision, just make an effort of will, just conquer your fear of change. But is it just true? nine0005

No matter how radically I changed my life, it always turned out that there is one very significant part of the former life, which invariably moved into a new life with me.

Do you know what?

I myself.

And so the new, radically changed life rather quickly began to acquire recognizable features of the former one. And through her, until recently such an attractive facade, the same tasks that I had not solved in my previous life began to emerge; the same questions to which in my previous life I could not find an answer; the same difficulties from which I so wanted to escape. nine0005

It is very scary to change your life drastically. And absolutely right, it's scary.

The circumstances of our life are never accidental. And there is nothing magical or supernatural about it. It's just that my life, with its pluses and minuses, advantages and problems, is an organic projection of myself: my character; how I make decisions; how do I build my relationships with loved ones; how I take care of myself or others.

The circumstances of my life are a projection of me. Therefore, it is impossible to change your life without changing yourself. But if you have changed, then there is no need to change life either - it will change itself, following you. nine0005

Very often, when it seems to us that in life we lack the courage to change it, in fact, we lack patience and calmness. Those changes in life that are really necessary occur naturally, not through fear and willpower, but through opportunities that open up when the time has come for them.

Life changes because you live it. Not because you're trying to trade it for another.

You know, it's okay to be dissatisfied with your life. Because life is always half a step behind you. nine0005

If you do not stop in your development, then the circumstances of your life always turn out to be a little outdated in relation to yourself, to your views and principles.

Because you have already changed, but your life has not yet had time.

This does not mean that you need to run away, urgently change something. It means you have a future.

Vladimir Yakovlev is a landmark personality of the Russian media market: the founder of not only the Kommersant newspaper and the Snob media project, but also a whole new school of Russian journalism of the post-propaganda era. Now Yakovlev is developing the author's project "The Age of Happiness", holds festivals of the same name, and maintains a video blog "Yakovlev on Mondays". Yakovlev has not only built several vibrant media businesses, he is also a consumer of personal development practices with over thirty years of experience. His expertise as a life coach is the experience of a serial entrepreneur, multiplied by the practical experience of a person who has been engaged in personal transformation all his adult life.