How can students study effectively

Study Smarter Not Harder – Learning Center

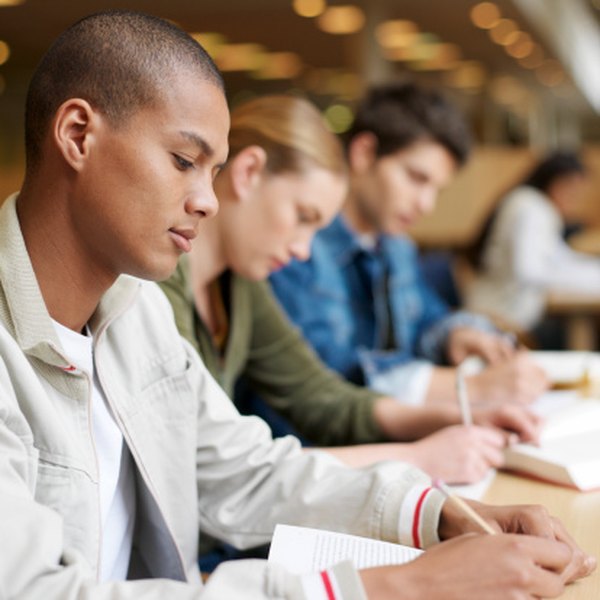

Do you ever feel like your study habits simply aren’t cutting it? Do you wonder what you could be doing to perform better in class and on exams? Many students realize that their high school study habits aren’t very effective in college. This is understandable, as college is quite different from high school. The professors are less personally involved, classes are bigger, exams are worth more, reading is more intense, and classes are much more rigorous. That doesn’t mean there’s anything wrong with you; it just means you need to learn some more effective study skills. Fortunately, there are many active, effective study strategies that are shown to be effective in college classes.

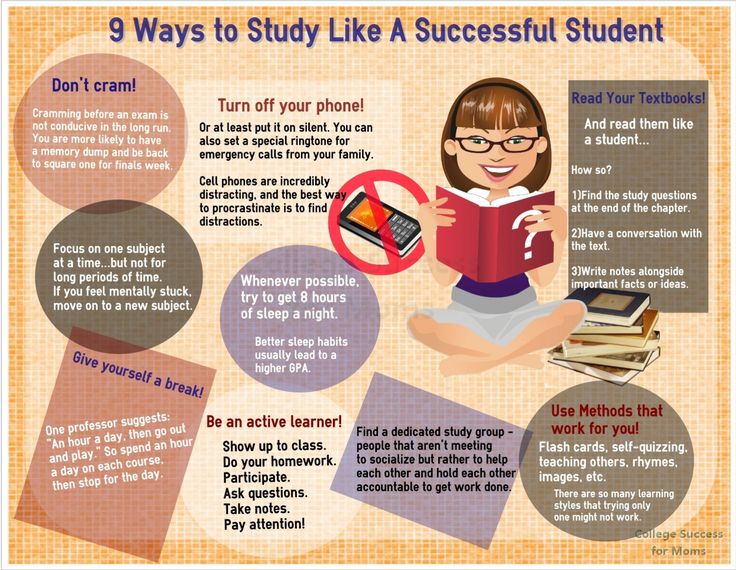

This handout offers several tips on effective studying. Implementing these tips into your regular study routine will help you to efficiently and effectively learn course material. Experiment with them and find some that work for you.

Reading is not studying

Simply reading and re-reading texts or notes is not actively engaging in the material. It is simply re-reading your notes. Only ‘doing’ the readings for class is not studying. It is simply doing the reading for class. Re-reading leads to quick forgetting.

Think of reading as an important part of pre-studying, but learning information requires actively engaging in the material (Edwards, 2014). Active engagement is the process of constructing meaning from text that involves making connections to lectures, forming examples, and regulating your own learning (Davis, 2007). Active studying does not mean highlighting or underlining text, re-reading, or rote memorization. Though these activities may help to keep you engaged in the task, they are not considered active studying techniques and are weakly related to improved learning (Mackenzie, 1994).

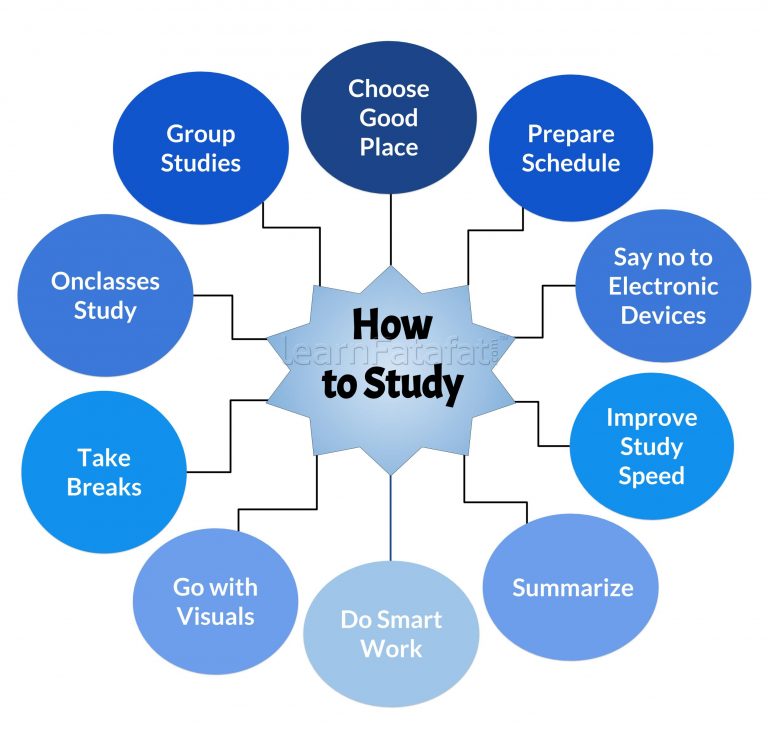

Ideas for active studying include:

- Create a study guide by topic. Formulate questions and problems and write complete answers. Create your own quiz.

- Become a teacher. Say the information aloud in your own words as if you are the instructor and teaching the concepts to a class.

- Derive examples that relate to your own experiences.

- Create concept maps or diagrams that explain the material.

- Develop symbols that represent concepts.

- For non-technical classes (e.g., English, History, Psychology), figure out the big ideas so you can explain, contrast, and re-evaluate them.

- For technical classes, work the problems and explain the steps and why they work.

- Study in terms of question, evidence, and conclusion: What is the question posed by the instructor/author? What is the evidence that they present? What is the conclusion?

Organization and planning will help you to actively study for your courses. When studying for a test, organize your materials first and then begin your active reviewing by topic (Newport, 2007). Often professors provide subtopics on the syllabi. Use them as a guide to help organize your materials. For example, gather all of the materials for one topic (e.g., PowerPoint notes, text book notes, articles, homework, etc. ) and put them together in a pile. Label each pile with the topic and study by topics.

) and put them together in a pile. Label each pile with the topic and study by topics.

For more information on the principle behind active studying, check out our tipsheet on metacognition.

Understand the Study Cycle

The Study Cycle, developed by Frank Christ, breaks down the different parts of studying: previewing, attending class, reviewing, studying, and checking your understanding. Although each step may seem obvious at a glance, all too often students try to take shortcuts and miss opportunities for good learning. For example, you may skip a reading before class because the professor covers the same material in class; doing so misses a key opportunity to learn in different modes (reading and listening) and to benefit from the repetition and distributed practice (see #3 below) that you’ll get from both reading ahead and attending class. Understanding the importance of all stages of this cycle will help make sure you don’t miss opportunities to learn effectively.

Spacing out is good

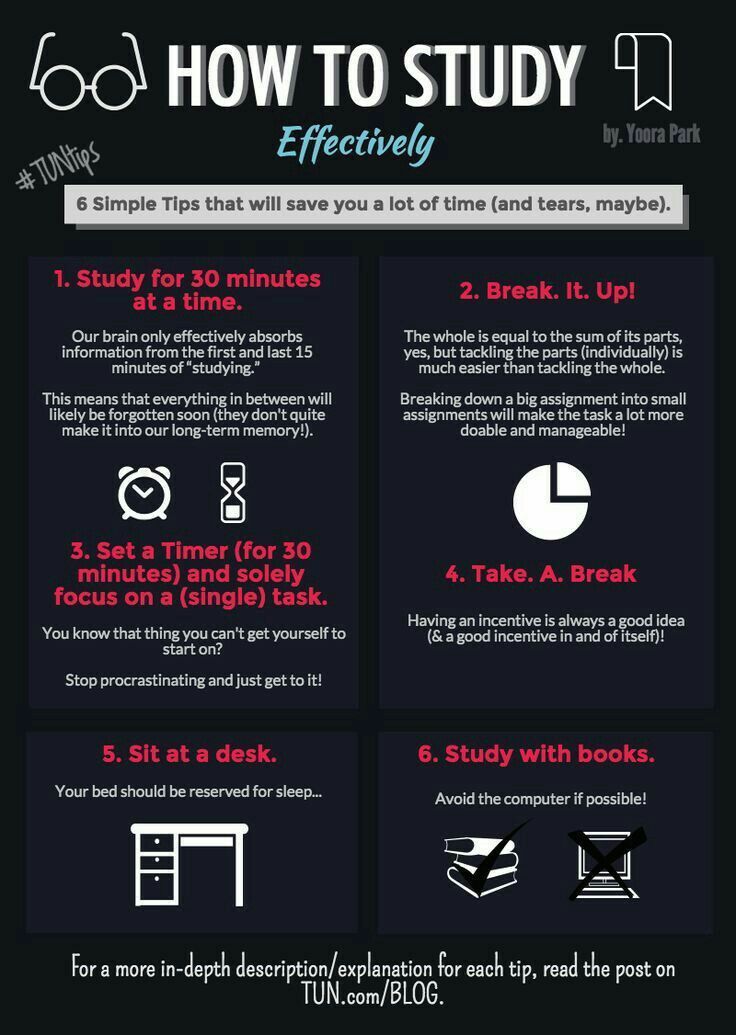

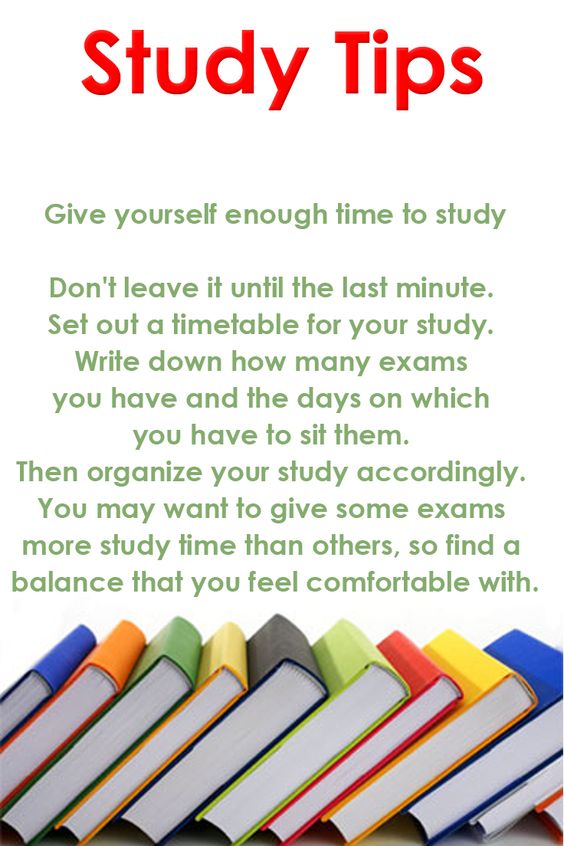

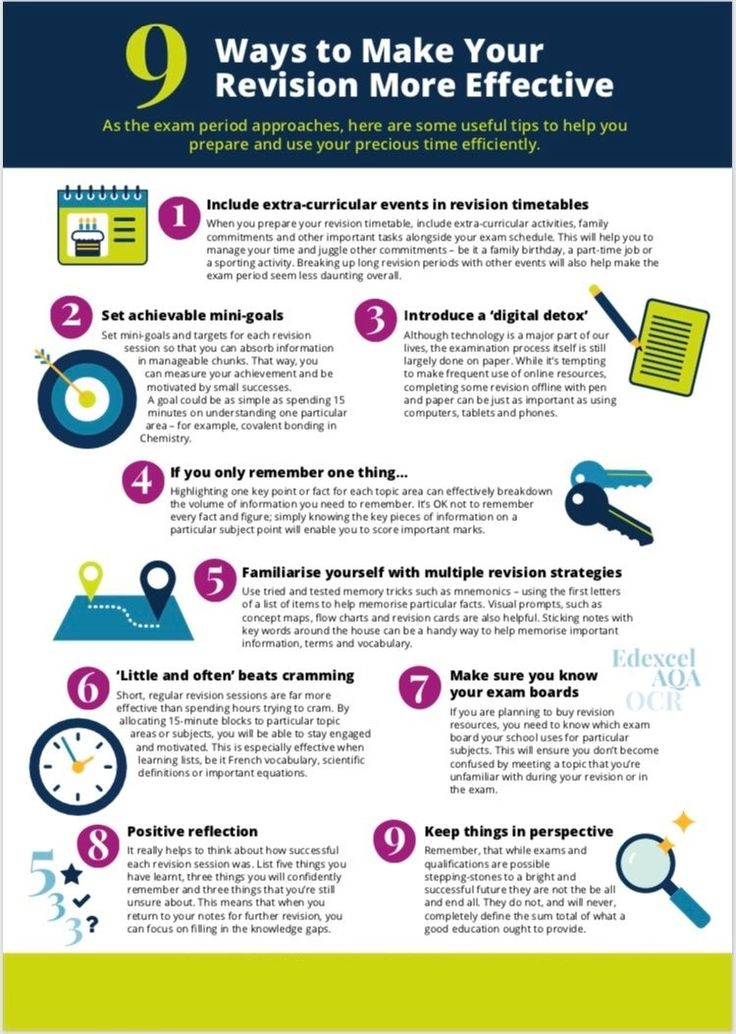

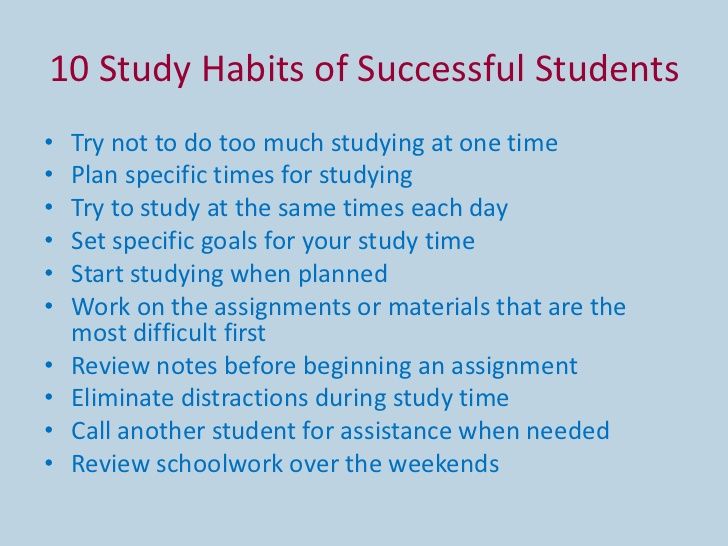

One of the most impactful learning strategies is “distributed practice”—spacing out your studying over several short periods of time over several days and weeks (Newport, 2007). The most effective practice is to work a short time on each class every day. The total amount of time spent studying will be the same (or less) than one or two marathon library sessions, but you will learn the information more deeply and retain much more for the long term—which will help get you an A on the final. The important thing is how you use your study time, not how long you study. Long study sessions lead to a lack of concentration and thus a lack of learning and retention.

In order to spread out studying over short periods of time across several days and weeks, you need control over your schedule. Keeping a list of tasks to complete on a daily basis will help you to include regular active studying sessions for each class. Try to do something for each class each day. Be specific and realistic regarding how long you plan to spend on each task—you should not have more tasks on your list than you can reasonably complete during the day.

Be specific and realistic regarding how long you plan to spend on each task—you should not have more tasks on your list than you can reasonably complete during the day.

For example, you may do a few problems per day in math rather than all of them the hour before class. In history, you can spend 15-20 minutes each day actively studying your class notes. Thus, your studying time may still be the same length, but rather than only preparing for one class, you will be preparing for all of your classes in short stretches. This will help focus, stay on top of your work, and retain information.

In addition to learning the material more deeply, spacing out your work helps stave off procrastination. Rather than having to face the dreaded project for four hours on Monday, you can face the dreaded project for 30 minutes each day. The shorter, more consistent time to work on a dreaded project is likely to be more acceptable and less likely to be delayed to the last minute. Finally, if you have to memorize material for class (names, dates, formulas), it is best to make flashcards for this material and review periodically throughout the day rather than one long, memorization session (Wissman and Rawson, 2012). See our handout on memorization strategies to learn more.

See our handout on memorization strategies to learn more.

It’s good to be intense

Not all studying is equal. You will accomplish more if you study intensively. Intensive study sessions are short and will allow you to get work done with minimal wasted effort. Shorter, intensive study times are more effective than drawn out studying.

In fact, one of the most impactful study strategies is distributing studying over multiple sessions (Newport, 2007). Intensive study sessions can last 30 or 45-minute sessions and include active studying strategies. For example, self-testing is an active study strategy that improves the intensity of studying and efficiency of learning. However, planning to spend hours on end self-testing is likely to cause you to become distracted and lose your attention.

On the other hand, if you plan to quiz yourself on the course material for 45 minutes and then take a break, you are much more likely to maintain your attention and retain the information. Furthermore, the shorter, more intense sessions will likely put the pressure on that is needed to prevent procrastination.

Furthermore, the shorter, more intense sessions will likely put the pressure on that is needed to prevent procrastination.

Silence isn’t golden

Know where you study best. The silence of a library may not be the best place for you. It’s important to consider what noise environment works best for you. You might find that you concentrate better with some background noise. Some people find that listening to classical music while studying helps them concentrate, while others find this highly distracting. The point is that the silence of the library may be just as distracting (or more) than the noise of a gymnasium. Thus, if silence is distracting, but you prefer to study in the library, try the first or second floors where there is more background ‘buzz.’

Keep in mind that active studying is rarely silent as it often requires saying the material aloud.

Problems are your friend

Working and re-working problems is important for technical courses (e.g., math, economics). Be able to explain the steps of the problems and why they work.

Be able to explain the steps of the problems and why they work.

In technical courses, it is usually more important to work problems than read the text (Newport, 2007). In class, write down in detail the practice problems demonstrated by the professor. Annotate each step and ask questions if you are confused. At the very least, record the question and the answer (even if you miss the steps).

When preparing for tests, put together a large list of problems from the course materials and lectures. Work the problems and explain the steps and why they work (Carrier, 2003).

Reconsider multitasking

A significant amount of research indicates that multi-tasking does not improve efficiency and actually negatively affects results (Junco, 2012).

In order to study smarter, not harder, you will need to eliminate distractions during your study sessions. Social media, web browsing, game playing, texting, etc. will severely affect the intensity of your study sessions if you allow them! Research is clear that multi-tasking (e. g., responding to texts, while studying), increases the amount of time needed to learn material and decreases the quality of the learning (Junco, 2012).

g., responding to texts, while studying), increases the amount of time needed to learn material and decreases the quality of the learning (Junco, 2012).

Eliminating the distractions will allow you to fully engage during your study sessions. If you don’t need your computer for homework, then don’t use it. Use apps to help you set limits on the amount of time you can spend at certain sites during the day. Turn your phone off. Reward intensive studying with a social-media break (but make sure you time your break!) See our handout on managing technology for more tips and strategies.

Switch up your setting

Find several places to study in and around campus and change up your space if you find that it is no longer a working space for you.

Know when and where you study best. It may be that your focus at 10:00 PM. is not as sharp as at 10:00 AM. Perhaps you are more productive at a coffee shop with background noise, or in the study lounge in your residence hall. Perhaps when you study on your bed, you fall asleep.

Have a variety of places in and around campus that are good study environments for you. That way wherever you are, you can find your perfect study spot. After a while, you might find that your spot is too comfortable and no longer is a good place to study, so it’s time to hop to a new spot!

Become a teacher

Try to explain the material in your own words, as if you are the teacher. You can do this in a study group, with a study partner, or on your own. Saying the material aloud will point out where you are confused and need more information and will help you retain the information. As you are explaining the material, use examples and make connections between concepts (just as a teacher does). It is okay (even encouraged) to do this with your notes in your hands. At first you may need to rely on your notes to explain the material, but eventually you’ll be able to teach it without your notes.

Creating a quiz for yourself will help you to think like your professor. What does your professor want you to know? Quizzing yourself is a highly effective study technique. Make a study guide and carry it with you so you can review the questions and answers periodically throughout the day and across several days. Identify the questions that you don’t know and quiz yourself on only those questions. Say your answers aloud. This will help you to retain the information and make corrections where they are needed. For technical courses, do the sample problems and explain how you got from the question to the answer. Re-do the problems that give you trouble. Learning the material in this way actively engages your brain and will significantly improve your memory (Craik, 1975).

What does your professor want you to know? Quizzing yourself is a highly effective study technique. Make a study guide and carry it with you so you can review the questions and answers periodically throughout the day and across several days. Identify the questions that you don’t know and quiz yourself on only those questions. Say your answers aloud. This will help you to retain the information and make corrections where they are needed. For technical courses, do the sample problems and explain how you got from the question to the answer. Re-do the problems that give you trouble. Learning the material in this way actively engages your brain and will significantly improve your memory (Craik, 1975).

Take control of your calendar

Controlling your schedule and your distractions will help you to accomplish your goals.

If you are in control of your calendar, you will be able to complete your assignments and stay on top of your coursework. The following are steps to getting control of your calendar:

- On the same day each week, (perhaps Sunday nights or Saturday mornings) plan out your schedule for the week.

- Go through each class and write down what you’d like to get completed for each class that week.

- Look at your calendar and determine how many hours you have to complete your work.

- Determine whether your list can be completed in the amount of time that you have available. (You may want to put the amount of time expected to complete each assignment.) Make adjustments as needed. For example, if you find that it will take more hours to complete your work than you have available, you will likely need to triage your readings. Completing all of the readings is a luxury. You will need to make decisions about your readings based on what is covered in class. You should read and take notes on all of the assignments from the favored class source (the one that is used a lot in the class). This may be the textbook or a reading that directly addresses the topic for the day. You can likely skim supplemental readings.

- Pencil into your calendar when you plan to get assignments completed.

- Before going to bed each night, make your plan for the next day. Waking up with a plan will make you more productive.

See our handout on calendars and college for more tips on using calendars as time management.

Use downtime to your advantage

Beware of ‘easy’ weeks. This is the calm before the storm. Lighter work weeks are a great time to get ahead on work or to start long projects. Use the extra hours to get ahead on assignments or start big projects or papers. You should plan to work on every class every week even if you don’t have anything due. In fact, it is preferable to do some work for each of your classes every day. Spending 30 minutes per class each day will add up to three hours per week, but spreading this time out over six days is more effective than cramming it all in during one long three-hour session. If you have completed all of the work for a particular class, then use the 30 minutes to get ahead or start a longer project.

Use all your resources

Remember that you can make an appointment with an academic coach to work on implementing any of the strategies suggested in this handout.

Works consulted

Carrier, L. M. (2003). College students’ choices of study strategies. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 96(1), 54-56.

Craik, F. I., & Tulving, E. (1975). Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 104(3), 268.

Davis, S. G., & Gray, E. S. (2007). Going beyond test-taking strategies: Building self-regulated students and teachers. Journal of Curriculum and Instruction, 1(1), 31-47.

Edwards, A. J., Weinstein, C. E., Goetz, E. T., & Alexander, P. A. (2014). Learning and study strategies: Issues in assessment, instruction, and evaluation. Elsevier.

Junco, R., & Cotten, S. R. (2012). No A 4 U: The relationship between multitasking and academic performance. Computers & Education, 59(2), 505-514.

Mackenzie, A. M. (1994). Examination preparation, anxiety and examination performance in a group of adult students. International Journal of Lifelong Education, 13(5), 373-388.

International Journal of Lifelong Education, 13(5), 373-388.

McGuire, S.Y. & McGuire, S. (2016). Teach Students How to Learn: Strategies You Can Incorporate in Any Course to Improve Student Metacognition, Study Skills, and Motivation. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Newport, C. (2006). How to become a straight-a student: the unconventional strategies real college students use to score high while studying less. Three Rivers Press.

Paul, K. (1996). Study smarter, not harder. Self Counsel Press.

Robinson, A. (1993). What smart students know: maximum grades, optimum learning, minimum time. Crown trade paperbacks.

Wissman, K. T., Rawson, K. A., & Pyc, M. A. (2012). How and when do students use flashcards? Memory, 20, 568-579.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 4.0 License.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Learning Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

If you enjoy using our handouts, we appreciate contributions of acknowledgement.

Make a Gift

10 Effective Study Tips and Techniques to Try This Year

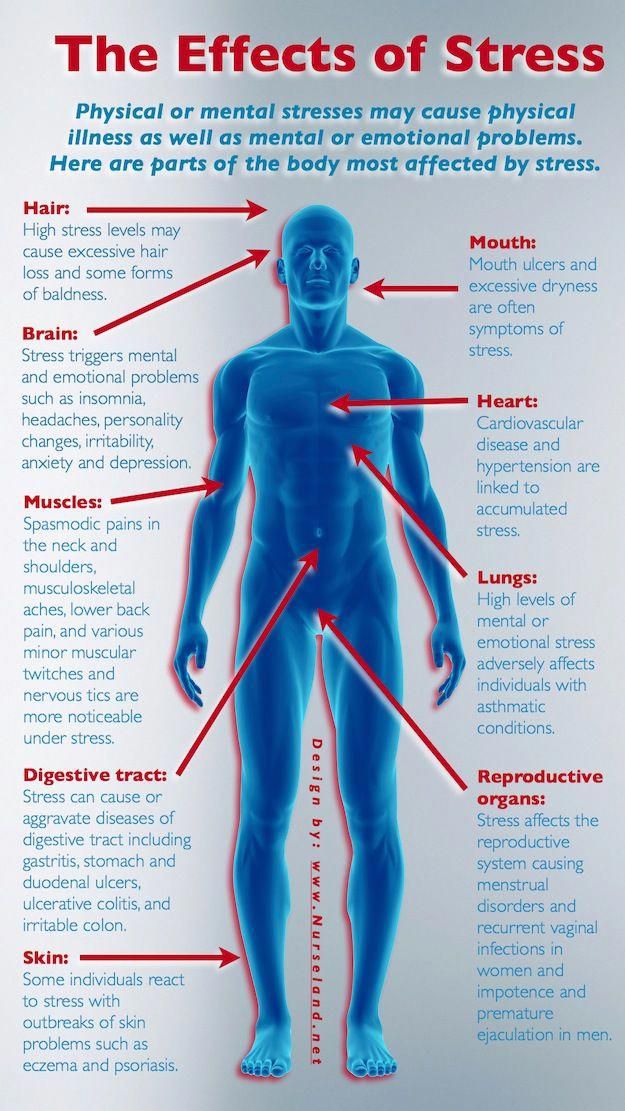

Is your current study method reading a textbook repeatedly, hoping something will stick? If so, do you find yourself stressed out because you can’t memorize such a vast quantity of information in such a short time?

As a grad student, it’s imperative to develop effective time management and study techniques that help you retain the most information. In grad school, cramming the night before doesn’t cut it anymore. Go into the new year with a new strategy and try some of these effective study tips below.

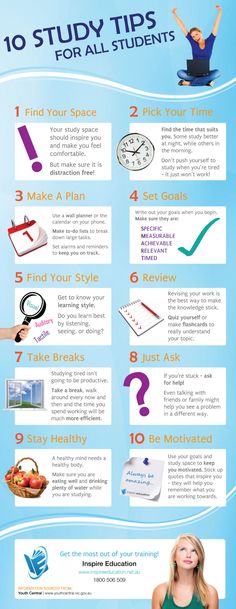

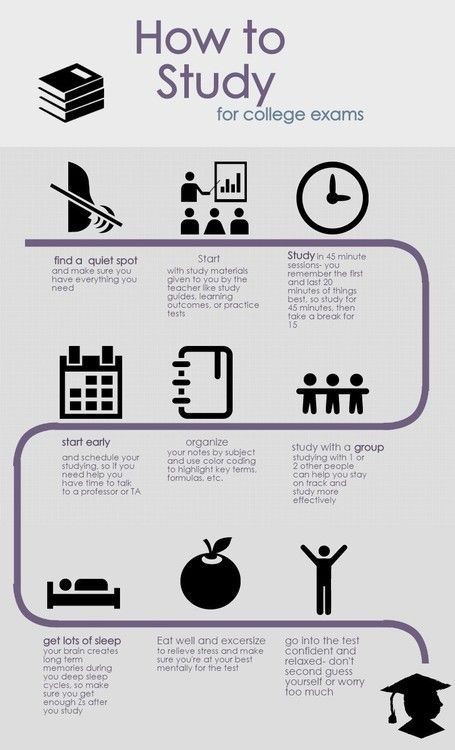

Set the Stage

First, you need to create the conditions-in your body and external environment-to successfully learn and retain information. Here are some study habits worth trying:

- Get a good night’s sleep: A recent study found a positive relationship between students’ grades and how much sleep they’re getting. However, this doesn’t only mean getting a full 8 hours of sleep before a big test.

What matters even more is getting enough sleep for several nights before you do the bulk of your studying.

What matters even more is getting enough sleep for several nights before you do the bulk of your studying. - Switch up your study environment: This might not seem like a promising study strategy, but studies show that switching up your study environment can increase recall performance. Instead of studying at home every day, try checking out a new coffee spot each week or heading to your local library. A change in scenery can improve both your memory and concentration levels.

- Stick with an environment that works: If you you have a good study space at home or a café that is reliably a productive place for you, it makes sense to stick with this when you are under pressure.

- Listen to calming music: You can listen to any music you like, but many agree that classical, instrumental, and lo-fi beats make good background music for studying and can actually help you pay attention to the task at hand. Songs with lyrics can be distracting.

- Eliminate distractions: Eliminate distractions by silencing your phone and annoying background noises such as the TV or radio. Make a pact with yourself to avoid checking social media until your study session is over.

- Snack on smart food: Coffee and candy will give you a temporary boost, but then you’ll have a blood sugar crash. For energy that is more focused and sustainable, try healthy snacks such as edamame, apples, or nuts.

10 Study Methods & Tips That Actually Work

1. The SQ3R Method

The SQ3R method is a reading comprehension technique that helps students identify important facts and retain information within their textbook. SQ3R (or SQRRR) is an acronym that stands for the five steps of the reading comprehension process. Try these steps for a more efficient and effective study session:

- Survey: Instead of reading the entire book, start by skimming the first chapter and taking notes on any headings, subheadings, images, or other standout features like charts.

- Question: Formulate questions around the chapter’s content, such as, What is this chapter about? What do I already know about this subject?

- Read: Begin reading the full chapter and look for answers to the questions you formulated.

- Recite: After reading a section, summarize in your own words what you just read. Try recalling and identifying major points and answering any questions from the second step.

- Review: Once you have finished the chapter, it’s important to review the material to fully understand it. Quiz yourself on the questions you created and re-read any portions you need to.

You can try this study technique before taking your final exam.

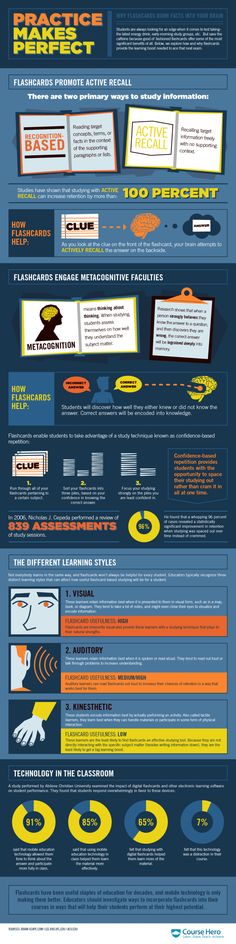

2. Retrieval Practice

Retrieval practice is based on the concept of remembering at a later time. Recalling an answer to a question improves learning more than looking for the answer in your textbook. And, remembering and writing down the answer to a flashcard is a lot more effective than thinking you know the answer and flipping the card over early.

If you practice retrieval, you are more likely to remember the information later on. Below are some ways you can implement the retrieval process into your study routine.

- Utilize practice tests: Use practice tests or questions to quiz yourself, without looking at your book or notes.

- Make your own questions: Be your own teacher and create questions you think would be on a test. If you’re in a study group, encourage others to do the same, and trade questions.

- Use flashcards: Create flashcards, but make sure to practice your retrieval technique. Instead of flipping a card over prematurely, write the answer down and then check.

3. Spaced Practice

Spaced practice (also known as “distributed practice”) encourages students to study over a longer period of time instead of cramming the night before. When our brains almost forget something, they work harder to recall that information. Spacing out your studying allows your mind to make connections between ideas and build upon the knowledge that can be easily recalled later.

Spacing out your studying allows your mind to make connections between ideas and build upon the knowledge that can be easily recalled later.

To try this technique, review your material in spaced intervals similar to the schedule below:

- Day 1: Learn the material in class.

- Day 2: Revisit and review.

- Day 3: Revisit and review.

- After one week: Revisit and review.

- After two weeks: Revisit and review.

It’s important to start planning early. At the beginning of each semester, schedule some time each day just for studying and reviewing the material. Even if your exams are months away, this will help you hold yourself accountable.

4. The PQ4R Method

This method takes an active approach to learning that improves memorization and understanding of the topic. Similar to the SQ3R method above, PQ4R is an acronym that stands for the six steps in the process.

- Preview: Preview the information before you start reading to get an idea of the subject. Skim the material and read only the headers, subheadings, and highlighted text.

- Question: Ask yourself questions related to the topic, such as, What do I expect to learn? What do I already know about this topic?

- Read: Read the information one section at a time and try to identify answers to your questions.

- Reflect: Did you answer all of your questions? If not, go back and see if you can find the answer.

- Recite: In your own words, either speak or write down a summary of the information you just read.

- Review: Look over the material one more time and answer any questions that have not yet been answered.

5. The Feynman Technique

The Feynman Technique is an efficient method of learning a concept quickly by explaining it in plain and simple terms. It’s based on the idea, “If you want to understand something well, try to explain it simply.” What that means is, by attempting to explain a concept in our own words, we are likely to understand it a lot faster.

It’s based on the idea, “If you want to understand something well, try to explain it simply.” What that means is, by attempting to explain a concept in our own words, we are likely to understand it a lot faster.

How it works:

- Write the subject/concept you are studying at the top of a sheet of paper.

- Then, explain it in your own words as if you were teaching someone else.

- Review what you wrote and identify any areas where you were wrong. Once you have identified them, go back to your notes or reading material and figure out the correct answer.

- Lastly, if there are any areas in your writing where you used technical terms or complex language, go back and rewrite these sections in simpler terms for someone who doesn’t have the educational background you have.

6. Leitner System

The Leitner System is a learning technique based on flashcards. Ideally, you keep your cards in several different boxes to track when you need to study each set. Every card starts in Box 1. If you get a card right, you move it to the next box. If you get a card wrong, you either move it down a box or keep it in Box 1 (if it’s already there).

Every card starts in Box 1. If you get a card right, you move it to the next box. If you get a card wrong, you either move it down a box or keep it in Box 1 (if it’s already there).

Each box determines how much you will study each set of cards, similar to the following schedule:

- Every day — Box 1

- Every two days — Box 2

- Every four days — Box 3

- Every nine days — Box 4

- Every 14 days — Box 5

7. Color-Coded Notes

Messy notes can make it hard to recall the important points of a lecture. Writing in color is a dynamic way to organize the information you’re learning. It also helps you review and prioritize the most important ideas.

A recent study found that color can improve a person’s memory performance. That same study found that warm colors (red and yellow) “can create a learning environment that is positive and motivating that can help learners not only to have a positive perception toward the content but also to engage and interact more with the learning materials. ” It also reported that warmer colors “increase attention and elicit excitement and information.”

” It also reported that warmer colors “increase attention and elicit excitement and information.”

Writing in color may seem like a no-brainer, but keep these tips in mind:

- Write down key points in red.

- Highlight important information in yellow.

- Organize topics by color.

- Don’t color everything—just the most important information.

8. Mind Mapping

If you’re a visual learner, try mind mapping, a technique that allows you to visually organize information in a diagram. First, you write a word in the center of a blank page. From there, you write major ideas and keywords and connect them directly to the central concept. Other related ideas will continue to branch out.

The structure of a mind map is related to how our brains store and retrieve information. Mind mapping your notes instead of just writing them down can improve your reading comprehension. It also enables you to see the big picture by communicating the hierarchy and relationships between concepts and ideas.

So, how do you do it?

- Grab a blank sheet of paper (or use a tool online) and write your study topic in the center, such as “child development.”

- Connect one of your main ideas (i.e., a chapter of your book or notes) to the main topic, such as “developmental stages.”

- Connect sub-branches of supporting ideas to your main branch. This is the association of ideas. For example, “Sensorimotor,” “Preoperational,” “Concrete operational,” and “Formal operational.”

- TIP: Use different colors for each branch and draw pictures if it helps.

9. Exercise Before Studying

Not only does exercise fight fatigue, but it can also increase energy levels. If you’re struggling to find the motivation to study, consider adding an exercise routine to your day. It doesn’t have to be a full hour at the gym. It can be a 20-minute workout at home or a brisk walk around your neighborhood. Anything to get your heart rate pumping. Exercising before you study:

- Kickstarts brain function and can help improve memory and cognitive performance.

- Releases endorphins, which can improve your mood and reduce stress levels.

10. Study Before Bed

Sleep is crucial for brain function, memory formation, and learning. Studying before you sleep, whether it is reviewing flashcards or notes, can help improve recall. According to Scott Cairney, a researcher from the University of York in the United Kingdom, “When you are awake you learn new things, but when you are asleep you refine them, making it easier to retrieve them and apply them correctly when you need them most. This is important for how we learn but also for how we might help retain healthy brain functions.”

When you’re asleep, the brain organizes your memories. Instead of pulling an all-nighter, study a few hours before bed and then review the information in the morning.

No one wants to spend more time studying than they need to. Learning effective study techniques can ensure you are fully prepared for your exams and will help curve any looming test anxiety. Hopefully, with the techniques above, you can avoid cramming the night before and make your study time more effective. For more tips, download the infographic below.

Hopefully, with the techniques above, you can avoid cramming the night before and make your study time more effective. For more tips, download the infographic below.

Sources:

Chai, Meei Tyng, et al. “Exploring EEG Effective Connectivity Network in Estimating Influence of Color on Emotion and Memory.” Frontiers in Neuroinformatics vol. 13, Oct. 9, 2019, doi:10.3389/fninf.2019.00066

Medical News Today, “Can You Learn in Your Sleep? Yes, and Here’s How”: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321161.php#1

Yana Weinstein and Megan Smith, “Learn How to Study Using… Spaced Practice” and “Learn How to Study Using… Retrieval Practice” The Learning Scientists, https://www.learningscientists.org/blog/2016/7/21-1 and https://www.learningscientists.org/blog/2016/6/23-1.

“Better Sleep Habits Lead to Better College Grades.” ScienceDaily, ScienceDaily, 1 Oct. 2019, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/10/191001083956.htm.

“Top 10 Healthy Snacks for Studying and Staying Focused: BrainMD. ” BrainMD Health Blog, 25 Oct. 2018, brainmd.com/blog/top-10-healthy-snacks-for-studying/.

” BrainMD Health Blog, 25 Oct. 2018, brainmd.com/blog/top-10-healthy-snacks-for-studying/.

“What Is Retrieval Practice? – Retrieval Practice.” Unleash the Science of Learning, www.retrievalpractice.org/why-it-works.

Whelan, Jesse. “Using the Leitner System to Improve Your Study.” Medium, Medium, 21 Sept. 2019, medium.com/@jessewhelan/using-the-leitner-system-to-improve-your-study-d5edafae7f0.

Chai, Meei Tyng, et al. “Exploring EEG Effective Connectivity Network in Estimating Influence of Color on Emotion and Memory.” Frontiers in Neuroinformatics, Frontiers Media S.A., 9 Oct. 2019, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6794354/.

Warner, Jennifer. “Exercise Fights Fatigue, Boosts Energy.” WebMD, WebMD, 3 Nov. 2006, www.webmd.com/diet/news/20061103/exercise-fights-fatigue-boosts-energy.

Aamodt, Sandra, and Sam Wang. “Exercise on the Brain.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 8 Nov. 2007, www.nytimes.com/2007/11/08/opinion/08aamodt.html?ei=5070&em=&en=875b1c15ea6447c9&ex=1194670800&pagewanted=print.

“Benefits of Exercise.” MedlinePlus, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 4 Oct. 2019, medlineplus.gov/benefitsofexercise.html.

Sandoiu, Ana. “Can You Learn in Your Sleep? Yes, and Here’s How.” Medical News Today, MediLexicon International, www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/321161.php#1.

How to study at the university to make it interesting and useful / Sudo Null IT News and can be considered as an independent work.

We often read posts like this, and also hear from students and graduates that their expectations from studying at the university were not justified. This problem can be viewed from different angles. I will only touch on a few aspects. Namely, those that relate to the interaction of universities and students. So, let's analyze the lamentations of the author of the original post, formulate the reasons for what is happening, and give newcomers advice on how to unlearn at the university and not regret that it was boring and useless.

The dissonance described by the author of the post comes from students' misunderstanding of what a university is. If we discard departmental universities engaged in the training of professional personnel for certain areas of life, then the purpose of universities (hereinafter universities, so as not to be confused with departmental universities) is scientific activity. In general, everything that happens in them is subordinated to this, including the education of students. In fact, students for universities are just "fresh blood". Yes, the university is a human community, and in order for it not to die out, but to "be fruitful and multiply", students are needed. How many of the graduates each year remain in various capacities within the walls of the alma mater? It is for them that this whole educational process basically exists.

If we discard departmental universities engaged in the training of professional personnel for certain areas of life, then the purpose of universities (hereinafter universities, so as not to be confused with departmental universities) is scientific activity. In general, everything that happens in them is subordinated to this, including the education of students. In fact, students for universities are just "fresh blood". Yes, the university is a human community, and in order for it not to die out, but to "be fruitful and multiply", students are needed. How many of the graduates each year remain in various capacities within the walls of the alma mater? It is for them that this whole educational process basically exists.

The author complains that no one was interested in their term papers. Well, not exactly: the leader is not interested in your emotions, how much and how you suffered over them, but it is interesting:

- The result is . The term paper topic could be a small original research, and you were assigned to do it.

If you succeeded, then the side effect will be that you are remembered and will be remembered.

If you succeeded, then the side effect will be that you are remembered and will be remembered. - Research Skill . Academic staff should regularly demonstrate the results of their research work. And you (students), annually, or usually more often, develop this skill, get used not only to the fact that you need to constantly be busy searching for new knowledge, but also to patiently and efficiently write reports about this activity (students write term papers, and researchers articles, monographs, textbooks).

The author also complains that many subjects were taught by the teachers without interest. Here you need to understand and keep in mind two things:

- Flow disciplines . Usually these are courses of lectures and seminars (or laboratory work, or workshops) in general educational and general professional fields. For example, in computer science it will be discrete mathematics, programming, databases. Such courses are held for a large number of students, and are guided by a certain average level of the student.

Therefore, revelations are not to be expected. As well as the special care of the teacher about the students studying with them in "their" subject. It is rare to find a lecturer here who is an expert in what he teaches, or even breaks into the subject. The usual case is a teacher who leads the discipline in so far as (accidentally got it at the beginning of a career, or the person leading it left and had to be picked up). Therefore, if some subject was informative and exciting for you, then consider that you are very lucky. If not, don't worry, it could be worse.

Therefore, revelations are not to be expected. As well as the special care of the teacher about the students studying with them in "their" subject. It is rare to find a lecturer here who is an expert in what he teaches, or even breaks into the subject. The usual case is a teacher who leads the discipline in so far as (accidentally got it at the beginning of a career, or the person leading it left and had to be picked up). Therefore, if some subject was informative and exciting for you, then consider that you are very lucky. If not, don't worry, it could be worse. - Special courses. But this is the place where the chance to pass an interesting item is already much higher. Such courses are often taught by experts in the field. They either conduct relevant research or work in production in this area. Often such special courses appear in the curriculum for specific teachers.

What can a student do here? At first glance, nothing. But you can try the following: thoroughly study the curriculum, find out who teaches what discipline, and build your expectations and strategy for passing them, in accordance with this. If the discipline is "ordinary", and the leading teacher is not so hot, then you can engage in self-education, and take classes creatively or formally, depending on motivation. Also, in this case, it does not hurt to find out from the teacher which books (perhaps online courses) he considers authoritative, and get trained on them.

If the discipline is "ordinary", and the leading teacher is not so hot, then you can engage in self-education, and take classes creatively or formally, depending on motivation. Also, in this case, it does not hurt to find out from the teacher which books (perhaps online courses) he considers authoritative, and get trained on them.

Let's talk separately about practice . Practice is a special kind of educational activity of students. Unfortunately, the role of practice is often downplayed. This is due to various reasons. One of which is the lack of real interest of the university. Usually, the practice is carried out separately from the so-called theoretical training, for example, after the end of the academic semester, or at its beginning, but it can also go in parallel with the usual educational process. Obviously, the purpose of the practice is to give the student practical skills in the profession. Ideally, practice should take place in a real production, where students are sent by the university. In reality, the case is often like this: in the first and second year of undergraduate studies, students do practice within the walls of the university, doing primitive work, perhaps not directly related to the profession, or the practice is replaced by an independent study of one of the aspects of what was studied in theory before. Third- and fourth-year students are often expected to independently find an enterprise where they will be hired for internships, and bring a report and certificate from the place of internship. Can something be squeezed out of the university in terms of practice? Yes, you certainly may. Firstly, if you have proven yourself to be a good student (see text below), then instead of primitive practice in the first two years, you may be offered something more interesting. And if not offered, then you can ask about other options, it is possible that there is something better especially for you. Secondly, (relevant for undergraduates) local enterprises can actively hunt future juniors through university practice.

In reality, the case is often like this: in the first and second year of undergraduate studies, students do practice within the walls of the university, doing primitive work, perhaps not directly related to the profession, or the practice is replaced by an independent study of one of the aspects of what was studied in theory before. Third- and fourth-year students are often expected to independently find an enterprise where they will be hired for internships, and bring a report and certificate from the place of internship. Can something be squeezed out of the university in terms of practice? Yes, you certainly may. Firstly, if you have proven yourself to be a good student (see text below), then instead of primitive practice in the first two years, you may be offered something more interesting. And if not offered, then you can ask about other options, it is possible that there is something better especially for you. Secondly, (relevant for undergraduates) local enterprises can actively hunt future juniors through university practice. Finally, some universities take their students to practice in the laboratory. Ideal for starting an academic career.

Finally, some universities take their students to practice in the laboratory. Ideal for starting an academic career.

Finally, about final qualifying work aka diploma. Is it worth it to complain that no one is interested in your diploma, it was read by the authorities a couple of times, and it will "die" immediately after its defense? What do you think is the probability that your supervisor will be interested in your diploma if you came to him with your topic? That's the same. At best, he will be a formal leader, he will not take any intellectual part, and he will read your WRC only to make sure that it can be admitted to defense. Do you want the head of the diploma to be useful? Take care of this issue in advance. Not six months before the defense, but at least a year, preferably two. Let the leader know that you are interested in the subject of his academic work, and you would like to take the task from him at the WRC. When you receive a task or topic, start immediately. And give the first result no later than a week later. Let it be just a bibliography on the topic. But you will demonstrate your willingness to work on the topic, and the professor will have a desire to help you. Keep working on the topic regularly. Do not take long breaks, otherwise you may get the impression that you scored on a diploma. Listen to what your boss has to say if you want him to remain interested in what you are doing. If you want the work to "live" after the defense, hint to the supervisor that you plan to enter the magistracy or even graduate school, and continue to deal with this topic.

And give the first result no later than a week later. Let it be just a bibliography on the topic. But you will demonstrate your willingness to work on the topic, and the professor will have a desire to help you. Keep working on the topic regularly. Do not take long breaks, otherwise you may get the impression that you scored on a diploma. Listen to what your boss has to say if you want him to remain interested in what you are doing. If you want the work to "live" after the defense, hint to the supervisor that you plan to enter the magistracy or even graduate school, and continue to deal with this topic.

Now a few words about how a student can make life for himself at the university more interesting and useful.

- Join the local student scene. This could be a programming competition club, a science club, or even a student design bureau. Such a party can be managed by an enthusiastic teacher, or it can be self-managed. In the first case, you will learn about the party from the appropriate teacher, or you will be directed to him.

In the second case, you will see the corresponding ad or they will come to you with an advertisement. If neither one nor the other happened in the very first days from the beginning of studies, then this is a cause for concern. Either there is no party, or they are waiting for your own initiative. From personal experience: direct advertising is not effective, more sense from independent coming to you of initiative guys.

In the second case, you will see the corresponding ad or they will come to you with an advertisement. If neither one nor the other happened in the very first days from the beginning of studies, then this is a cause for concern. Either there is no party, or they are waiting for your own initiative. From personal experience: direct advertising is not effective, more sense from independent coming to you of initiative guys. - If you haven't found such a party, create your own. Universities favor students' extracurricular activities and can help you with this, for example, provide you with permanent or regular premises, finance the purchase of equipment, and pay for business trips. Creating your own party is also a good organizational experience. Plus, you will make acquaintances with the same enthusiasts of your business.

- Find a supervisor. If you feel a great craving for knowledge in yourself, sit a lot reading books or learning new technologies for you, then it makes sense to find yourself a supervisor and gain research work experience.

Most of the teachers are interested in the scientific guidance of students (but in my opinion not all, including advanced ones). Why this is so is written above. For you, it’s a double benefit, you will be able to immerse yourself in narrow issues and understand it properly, and at the same time you will understand if you would like to work in the academic world. I especially want to emphasize that R&D for a student planning to go into R&D (research and development, research and development) is a necessary thing, skills and reputation need to be developed from a young age.

Most of the teachers are interested in the scientific guidance of students (but in my opinion not all, including advanced ones). Why this is so is written above. For you, it’s a double benefit, you will be able to immerse yourself in narrow issues and understand it properly, and at the same time you will understand if you would like to work in the academic world. I especially want to emphasize that R&D for a student planning to go into R&D (research and development, research and development) is a necessary thing, skills and reputation need to be developed from a young age. - Be an active student. Even if the lecturer is good, and you are smart, and "everything is clear" to you, ask questions. But not superficial, that is, the answer to which lies on the surface (easy to google, obvious, or easy to calculate), but those that will make you think not only of you. Think about what the lecturer did not say, but would it be appropriate to say? Look at the problem at hand from a different angle.

Where can you go next? Feel free to ask clarifying questions, especially if something confuses you, or if you notice that the lecturer made a mistake. Sometimes, if you find a serious mistake, you can tell the lecturer about it in private, so as not to make him look unsightly in front of other students. A good teacher will thank you for this.

Where can you go next? Feel free to ask clarifying questions, especially if something confuses you, or if you notice that the lecturer made a mistake. Sometimes, if you find a serious mistake, you can tell the lecturer about it in private, so as not to make him look unsightly in front of other students. A good teacher will thank you for this. - Get a job at the university. It's not about the salary, it's about getting the most out of your university studies. How can this be useful? And will it hurt your studies? First, let's figure out what kind of work is available to a student within the walls of the university. Most likely a freshman will not be taken anywhere. He does not yet have any formal training to take even the most grassroots position. But starting from the second year, you can be hired as a laboratory assistant. Usually this work is associated with the support of the educational process. As a master's student, you will be able to apply for the position of engineer.

Here you will also deal with support, but probably at a more complex level. The difference is something like this: laboratory assistants wipe the monitors, and engineers install the operating system. In some universities, work as a laboratory assistant or engineer will be within the walls of laboratories, which in my opinion is very cool. Even if your duties are primitive, you can think about what and how can be done differently and better, of course, within the limits of what is permitted. It will probably be a plus that you will see the university as if from the inside. You will see and maybe understand something that is not visible to ordinary students. As for combining with studies, here, firstly, since you are a student, you will work part-time, and you will be allowed to study. Secondly, teachers will be more loyal to you in terms of the educational process, since you are a colleague. Finally, about the salary too: take it as an increased scholarship ... (In some universities, an innovation has appeared: master's students are hired to work as mentors.

Here you will also deal with support, but probably at a more complex level. The difference is something like this: laboratory assistants wipe the monitors, and engineers install the operating system. In some universities, work as a laboratory assistant or engineer will be within the walls of laboratories, which in my opinion is very cool. Even if your duties are primitive, you can think about what and how can be done differently and better, of course, within the limits of what is permitted. It will probably be a plus that you will see the university as if from the inside. You will see and maybe understand something that is not visible to ordinary students. As for combining with studies, here, firstly, since you are a student, you will work part-time, and you will be allowed to study. Secondly, teachers will be more loyal to you in terms of the educational process, since you are a colleague. Finally, about the salary too: take it as an increased scholarship ... (In some universities, an innovation has appeared: master's students are hired to work as mentors. A mentor is a teaching assistant who can be entrusted with checking laboratory work and advising on them. The salary is small, but a good start to an academic career. )

A mentor is a teaching assistant who can be entrusted with checking laboratory work and advising on them. The salary is small, but a good start to an academic career. ) - Change attitude. Now, if you have experience of going to some events, for example, to circles or meetups, with what feeling did you go there? Probably with anticipation of new knowledge, new acquaintances, "delicious" conversation, involvement in something cool. Who prevents you from having the same attitude towards going to university?

In my opinion, what was written above suggests that the solution to the problem of boring and useless studies is in the hands of the student himself, too. You need to stop perceiving the university solely as an unnecessary swamp, which also owes you something. And it is better to make your own efforts to ensure that this swamp dries up and "covers with flowering meadows."

A detailed discussion about what a university is and why it is needed is given in the book "Why are universities needed?" Stefan Collini, translated into Russian and published in 2016 by the HSE Publishing House.

7 ways to learn effectively and with pleasure

In the modern world, the ability to effectively master new knowledge is a skill that is necessary not only within a school or university, but also an important factor in career development. Lifelong learning is a behavior that is becoming the norm for more and more people.

However, the learning process often turns into a forced task, bringing only stress and negative emotions. One of the main reasons for this is the wrong approach to acquiring knowledge. How to maximize learning efficiency? Here are some tips to help you avoid some of the pitfalls and make the learning process fun, productive, and rewarding.

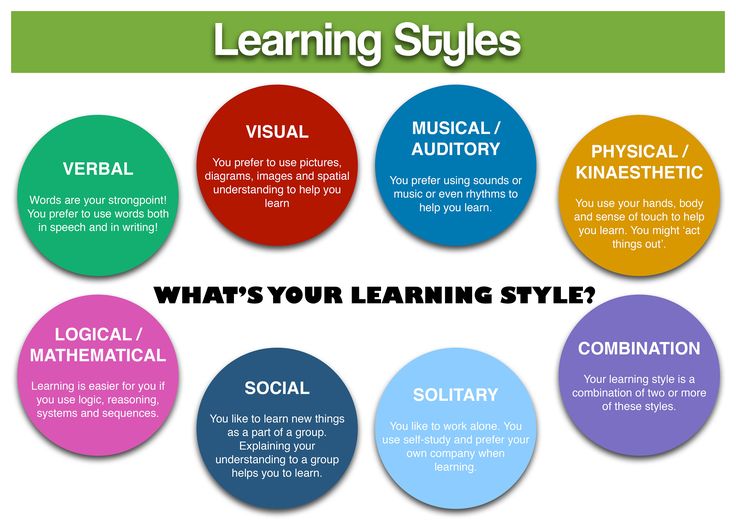

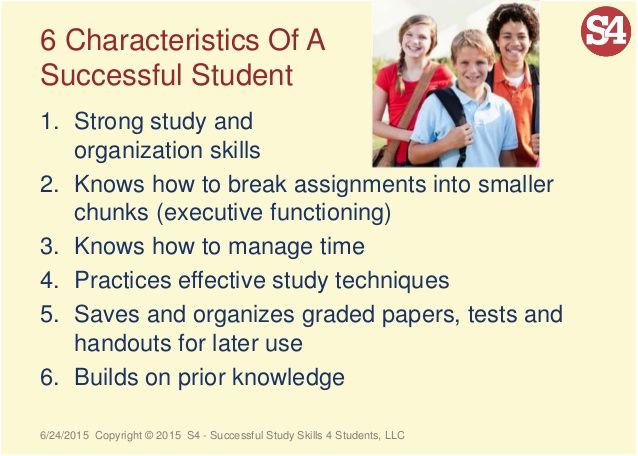

1. Consider individual differences when choosing a learning strategy

Strategies that work for some people may not work for others. There are many different approaches to learning, taking into account the form in which a person learns new information and unfamiliar concepts better. Someone prefers to read, and someone prefers to listen, someone needs notes, and someone needs flash cards.

The choice of strategy depends not only on individual characteristics, but also on the subject being studied. For example, if you are studying philosophy and programming, it is wise to choose a different approach for each of these disciplines. If you don't know which learning strategy is right for you, the best way to find the answer is through practice. Use different techniques and evaluate the results, try to mix different styles until you find the approach that allows you to master new knowledge as efficiently as possible.

2. Make a plan

Another important factor in productive learning is a good plan. Observations show that students who have a clear understanding of what they want to learn, as well as what specific steps to take to achieve this, achieve much better results.

Students already have a curriculum at the university. It should be studied in advance, as well as supplemented with individual lessons. If you are self-educated, you can find plans for studying almost any disciplines and skills on the Internet. Based on them, develop your own learning strategy, which should then be adjusted as you move forward.

Based on them, develop your own learning strategy, which should then be adjusted as you move forward.

3. Distribute the load evenly

A study marathon right before an exam, when you have to memorize the amount of information for months of study in several days, a situation familiar to many students. If your goal is just to pass the exam, this strategy is fine. However, if you want the knowledge you gain to be useful and stay with you for a long time, it is better to abandon this approach.

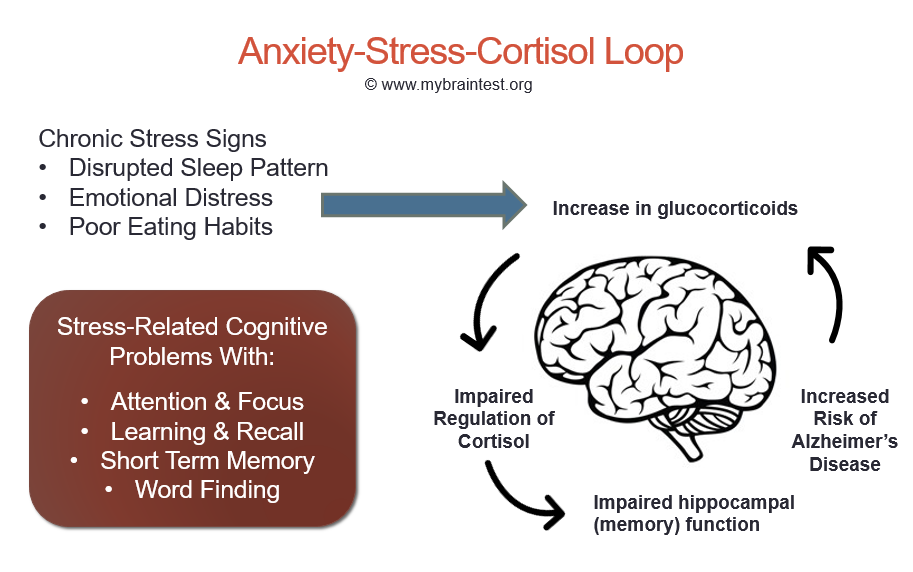

For better assimilation of new information, it is worth studying regularly and in small sessions. Even load distribution and spaced repetitions are the key to solid knowledge. If you overload yourself, it will lead to stress and loss of concentration, which will negatively affect the quality of the knowledge you receive.

4. Learn smarter, not harder

There are certain situations in which memorization is justified. However, this strategy is not effective if you want to make practical use of new knowledge. For knowledge to be useful, information must not be memorized, but understood.

For knowledge to be useful, information must not be memorized, but understood.

To make the learning process more productive and take up fewer resources, it is important to listen to what teachers have to say. They can share useful resources and give advice on how to organize the learning process, which can potentially save you a lot of time and effort. Check the recommended resources, look for additional sources of information yourself. Sometimes, to master a complex concept, it is enough to read about it in another textbook, where the material is presented in a form that is more convenient for you.

5. Use knowledge in practice

Practice is perhaps the most effective way to learn new knowledge. Theory can be abstract, many people find it difficult to understand certain concepts when they are not related to real life processes. Therefore, to increase the productivity of the educational process, it is recommended to devote as much time as possible to practice.

Finding good examples and doing your own projects to get real results from the use of new knowledge - all this helps to get the most out of the learning process and achieve high results.

6. Communicate

Self-education can be effective, but learning will be even more productive if you study not alone, but in the company of other people. For example, it could be a friend or acquaintance with similar learning goals. When you have such a study companion, you can discuss new information with him, find solutions to problems together, and work productively on complex projects. The exchange of ideas and knowledge, the opportunity to learn from each other - teamwork has many advantages.

Communication in the educational process also includes seeking help from teachers and experts in a particular field. If you run into any problem, don't be afraid to ask a knowledgeable person for advice.