Histrionic personality disorder lying

Pathological Lying Revisited | Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law

OtherREGULAR ARTICLE

Charles C. Dike, Madelon Baranoski and Ezra E. H. Griffith

Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law Online September 2005, 33 (3) 342-349;

- Article

- Info & Metrics

Abstract

Although pathological lying was first described in the medical literature over 100 years ago, it remains a poorly understood concept. Psychiatrists continue to grapple with the full ramifications of the condition, even though interest specifically in pathological lying seems to have waned in recent times. The impact of pathological lying deserves critical attention from forensic psychiatrists because of the implications that untruths have in a legal context. In this article, the authors review the considerable vagueness and confusion that has surrounded this concept and examine the extent to which a person can control lying behavior and the related question of whether pathological liars have responsibility for their actions.

While providing a structured framework for considering pathological lying in the forensic context, the authors conclude that further systematic research is needed to resolve the questions raised in this article.

In August 2001, the State of California Commission on Judicial Performance ordered the removal from office of Judge Patrick Couwenberg for making misrepresentations to become a judge, continuing to make misrepresentations while a judge, and deliberately providing false information to the Commission in the course of its investigation.1 The judge had lied at various times to judges, attorneys, a newspaper reporter, and the Commission on Judicial Performance. He told the Commission, under oath, that he had participated in covert CIA operations in Southeast Asia and Africa and that he had a master's degree in psychology when, in reality, he had never been in the CIA nor did he have a degree in psychology. He had committed many other misrepresentations, including stating that he had received a Purple Heart for injuries sustained in Vietnam and dramatically reporting that shrapnel was still lodged in his groin. In reality, he was never in Vietnam during the war.1

In reality, he was never in Vietnam during the war.1

A psychiatrist expert witness testifying before a panel of three judges sitting as special masters investigating Judge Couwenberg concluded that the judge was suffering from pseudologia fantastica which he described as “story telling that often has sort of a matrix of fantasy interwoven with some facts” (Ref. 1, p 10). The expert further testified that pseudologia fantastica is treatable with therapy and did not render Judge Couwenberg unfit for judicial service. The basis for the conclusions regarding treatment and fitness for judicial service was not stated in the reference article and therefore is not available for review.

Cases like Judge Couwenberg's continue to emerge from time to time. Recent media articles chronicling the lying behavior of prominent men such as Joseph J. Ellis,

2 a Pulitzer Prize winning historian and professor of history at Mount Holyoke College; Jeffery Archer,3 member of the House of Lords of England; and Sir Laurens Van der Post,4 former spiritual adviser to Prince Charles and godfather to Prince William, have generated significant interest. A former student of Professor Ellis, upon learning of his mentor's lies was quoted as saying, “He seemed so genuine. Perhaps it was a fantasy he came to believe himself” (Ref. 5, p A12). This observation raised important questions: did the just‐named individuals consciously and willfully engage in spewing their lies or were they unable to control their lying?

A former student of Professor Ellis, upon learning of his mentor's lies was quoted as saying, “He seemed so genuine. Perhaps it was a fantasy he came to believe himself” (Ref. 5, p A12). This observation raised important questions: did the just‐named individuals consciously and willfully engage in spewing their lies or were they unable to control their lying?

The concept of pathological lying, in which an individual repeatedly and apparently compulsively tells false stories, is not new to psychiatry. Numerous articles were written on it in the first half of the 20th century. However, interest in it waned drastically, to the extent that in recent years, it has received very little mention. Yet, the relatively modest light shed on pathological lying in recent psychiatric literature may not reflect its true prevalence in the pathology encountered routinely by clinical psychiatrists. Rather, it may be that psychiatrists simply know little about the subject and have difficulty recognizing the phenomenon.

Lies have been written about and classified for centuries. However, as noted by Healy and Healy,6 it was a German physician (Dr. Delbruck) who first clearly described the concept of pathological lying after an extensive examination of lies told by five of his patients. He concluded that these lies were so abnormal and out of proportion that they deserved a special category, which he described as pseudologia phantastica, terminology that is used interchangeably with pseudologia fantastica, which may be an Americanized spelling. Pathological lying, pseudologia fantastica, mythomania and morbid lying are generally used interchangeably, although it remains debatable whether they all describe the same phenomenon. Indeed, Bursten's7 description of Manipulative Personality shows characteristics similar to those of pathological lying. Nevertheless, for the purpose of this article, we make no distinction among the terms just described. In addition, we confine our discussion to the narrow phenomenon of pathological lying and do not consider the broader concept of lying. The latter subject has been the object of considerable discussion.

The latter subject has been the object of considerable discussion.

Many articles have variously defined pseudologia fantastica, but a commonly quoted definition is that put forth by Healy and Healy8 who described it as “falsification entirely disproportionate to any discernible end in view, may be extensive and very complicated, manifesting over a period of years or even a lifetime, in the absence of definite insanity, feeblemindedness or epilepsy” (Ref. 8, p 1). While this is a very comprehensive definition, it raises the question of whether definite insanity, feeblemindedness, or epilepsy must be absent for lying to be considered pathological.

Selling disagreed. He believed that “obvious mental disease, particularly a diagnosable psychopathic personality of some type” (Ref. 9, p 336) was responsible for pseudologia fantastica.

While no consensus definition for pathological lying currently exists in the literature, the identified functional elements of the phenomenon are: the repeated utterance of untruths; the lies are often repeated over a period of years, with the lies eventually becoming a lifestyle; material reward or social advantage does not appear to be the primary motivating force but the lying is an end in itself; an inner dynamic rather than an external reason drives the lies, but when an external reason is suspected, the lies are far in excess of the suspected external reason; the lies are often woven into complex narratives.

We shall define pathological lying as Healy and Healy8 did, but without the quagmire of etiology. Pathological lying is falsification entirely disproportionate to any discernible end in view, may be extensive and very complicated, and may manifest over a period of years or even a lifetime.

In this article, we revisit the concept of pathological lying and explore how it has been discussed in psychiatric literature. We intend to review the historical development of the concept and explore its current status in modern‐day psychiatry. We want to establish the similarities and differences between pathological lying and other more popular psychiatric syndromes, such as confabulation, delusional thinking, factitious disorder, and malingering. Finally, we pay attention to the significance of the concept in forensic psychiatry and the approach to the forensic assessment of pathological lying.

Historical Evolution of Pathological Lying

Pathological lying has been compared with the “pseudolying” observed in children. Despite their obvious comparability, it is important to draw a distinction between the “fantasy” lying observed in children and pathological lying. Children's use of fantasy to deny reality is said to be an important aspect of self‐development and self‐protection, but when this persists into adulthood, it becomes pathological. It has been proposed that the pathological liar's ego is fixated at the childhood level.10

Despite their obvious comparability, it is important to draw a distinction between the “fantasy” lying observed in children and pathological lying. Children's use of fantasy to deny reality is said to be an important aspect of self‐development and self‐protection, but when this persists into adulthood, it becomes pathological. It has been proposed that the pathological liar's ego is fixated at the childhood level.10

Eminent psychiatrists, such as Schneider,11 Bleuler,12 Jaspers,13 and Fish14 have all wondered if the pathological liar recognizes his or her story as false or believes it is real. Essential notions in much of the literature are the basis of the lying and the extent to which the pathological lying reflects impairment in reality testing. A brief review of past characterizations of pathological lying—published by Healy and Healy,8 who translated the early work that was originally published in German and summarized it in their landmark text published in 1926—shows a split between those who believe possible impairment in reality testing is an important consideration and those who believe pathological lying is a willful act.

Supporters of possible impaired reality testing observe that in the final evolution of the pathological lie, it cannot be differentiated from a delusion because, to the liar, it has the worth of a real experience.15 The lie ultimately wins power over the pathological liar, so that mastery of his or her own lies is lost. The new “I” supposedly overwhelms the normal “I” who now appears only at intervals, a condition that has been referred to as systematized delirium.16 Consciousness of the real situation was said to be clouded in the minds of the pathological liar, and the lies were described as impulsive and unplanned, “seizing” the liar suddenly.17 Pseudologues (pathological liars) were therefore not seen as liars in the true sense, despite the falsehood of their statements, because the verbalizations were not believed to be consciously engendered, nor the goal consciously recognized.

Further support for possible impaired reality testing in pathological lying was the observation that the lies were more elaborate than ordinary lies and left the grounds of reality more readily. The proposal that pathological lying is a “wish psychosis” was based on the observation that pathological liars saw their lies as reality and believed them.18

The proposal that pathological lying is a “wish psychosis” was based on the observation that pathological liars saw their lies as reality and believed them.18

Opponents of impaired reality testing in pathological lying noted that when the pathological liar's attention was energetically drawn to his lies, he could be brought to at least a partial recognition of their falseness, but when left to himself, he did not exert his attention in that direction.19 This observation suggested a degree of willfulness. Pseudologia fantastica was therefore described as a fantasy lie, a daydream communicated as reality, in which the lie can be a gratification in itself, for pleasure only and not for any other obvious gain.20 It was described as an intermediary phase between psychic health and neurosis.20 The notion of “double consciousness,” in which two forms of life run side by side, the actual and the desired, and the desired becomes preponderant and decisive, has been proposed as the mechanism underlying pathological lying. 21 It has also been suggested that the mental processes similar to those forming the basis of the impulse to literary creation in normal people is the foundation of the morbid romances and fantasies of those with pseudologia fantastica.22 The impulse that forces the fabrication of stories is supposedly bound up with the desire to play the role of the person depicted; fiction and real life are not separated. Further support for intact reality testing in pseudologia fantastica is the proposition that pseudologues usually have sound judgment in other matters, an observation that makes it difficult to prove that the pseudologue does not know that what he or she is doing is wrong.

21 It has also been suggested that the mental processes similar to those forming the basis of the impulse to literary creation in normal people is the foundation of the morbid romances and fantasies of those with pseudologia fantastica.22 The impulse that forces the fabrication of stories is supposedly bound up with the desire to play the role of the person depicted; fiction and real life are not separated. Further support for intact reality testing in pseudologia fantastica is the proposition that pseudologues usually have sound judgment in other matters, an observation that makes it difficult to prove that the pseudologue does not know that what he or she is doing is wrong.

In their work involving pathological liars, Healy and Healy8 observed that utterance of lies comes just as quickly and naturally as speaking truth comes to other people. They noted that even really insane individuals are not immune to pathological lying; some may tell tales that they recognize to be untrue. This observation further highlights the controversy about whether the pathological liar maintains contact with reality. In the opinion of Healy and Healy, pathological lying is very rarely a symptom by itself, as there is a tendency for the lying to be embedded in other forms of misrepresentation. The pathological liar gets himself/herself in a tight spot by lying and then tells more lies to extricate himself/herself. After a while, the only way out may be to run away to a different location.

This observation further highlights the controversy about whether the pathological liar maintains contact with reality. In the opinion of Healy and Healy, pathological lying is very rarely a symptom by itself, as there is a tendency for the lying to be embedded in other forms of misrepresentation. The pathological liar gets himself/herself in a tight spot by lying and then tells more lies to extricate himself/herself. After a while, the only way out may be to run away to a different location.

In summary, the historical review provides some elements that may be said to characterize the pathological liar or at least create a general impression of what constitutes pathological lying. Pathological liars can believe their lies to the extent that, at least to others, the belief may appear to be delusional; they generally have sound judgment in other matters; it is questionable whether pathological lying is always a conscious act and whether pathological liars always have control over their lies; an external reason for lying (such as financial gain) often appears absent and the internal or psychological purpose for lying is often unclear; the lies in pathological lying are often unplanned and rather impulsive; the pathological liar may become a prisoner of his or her lies; the desired personality of the pathological liar may overwhelm the actual one; pathological lying may sometimes be associated with criminal behavior; the pathological liar may acknowledge, at least in part, the falseness of the tales when energetically challenged; and, in pathological lying, telling lies may often seem to be an end in itself. However, it is evident that no single descriptive tableau of a pathological liar settles all the nosological and etiological questions raised by the phenomenon of pathological lying.

However, it is evident that no single descriptive tableau of a pathological liar settles all the nosological and etiological questions raised by the phenomenon of pathological lying.

Some Psychiatric Conditions and Pathological Lying

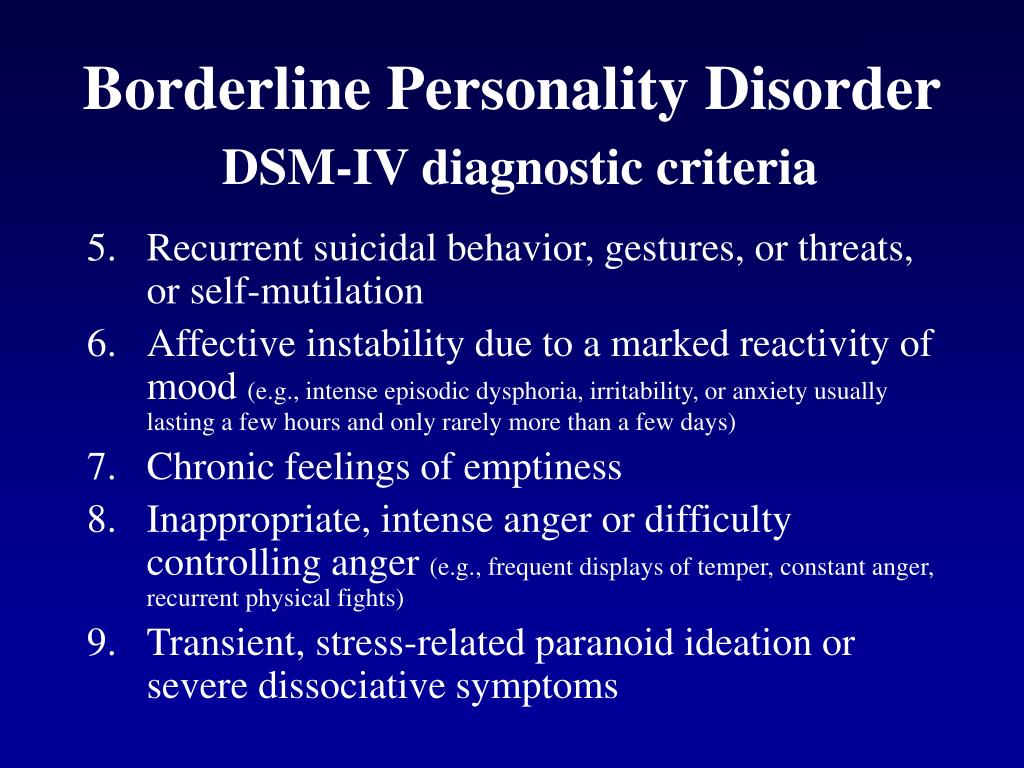

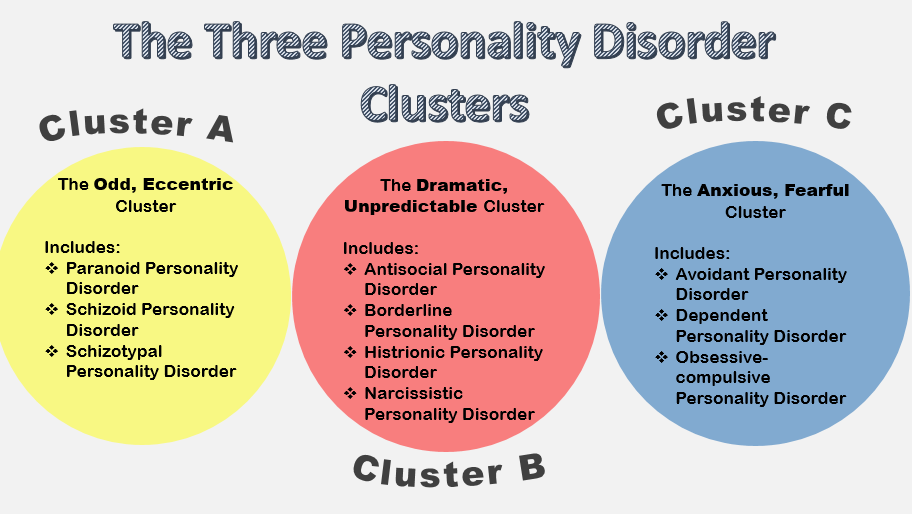

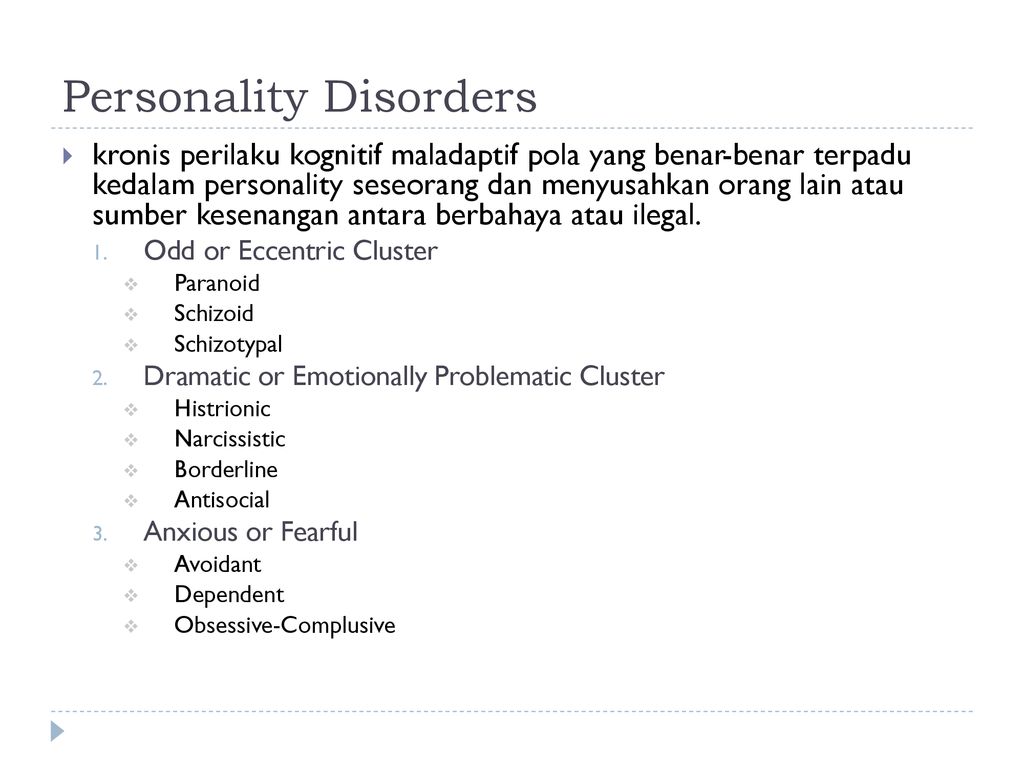

Psychiatric conditions that have been traditionally associated with deception in one form or another include Malingering, Confabulation, Ganser's Syndrome, Factitious Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, and Antisocial Personality Disorder. Lying may also occur in Histrionic and Narcissistic Personality Disorders. A brief description of these conditions will be offered for the purpose of comparing them with pathological lying. Although delusion is not traditionally associated with intentional deception, it has been included to highlight the difficulty of referring to pathological lying as delusional.

Malingering

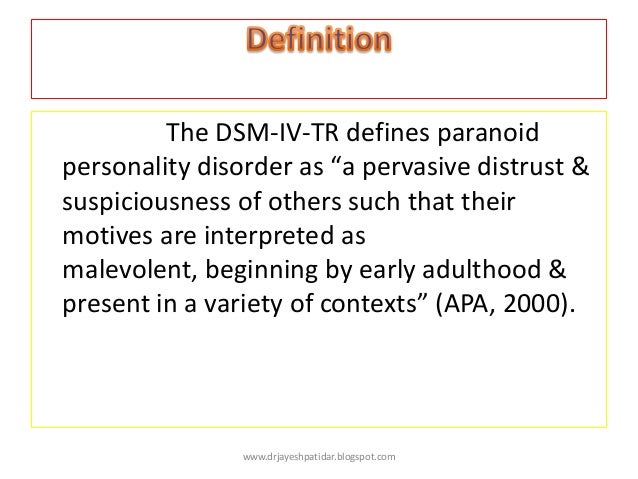

The DSM‐IV‐TR defines Malingering as the intentional production of false or grossly exaggerated physical or psychological symptoms, motivated by external incentives such as obtaining financial compensation or illicit drugs and avoiding work, military service, or criminal prosecution. While the purpose of lying is clear in Malingering, it is often unclear in pathological lying. In the rare instances when there appears to be an external incentive for pathological lying, the lies are often so grossly out of proportion to the perceived gain that they appear ridiculous. Further, some have proposed that the lie in pathological lying is not altogether a conscious (or intentional) act even when it starts off initially as one.10

While the purpose of lying is clear in Malingering, it is often unclear in pathological lying. In the rare instances when there appears to be an external incentive for pathological lying, the lies are often so grossly out of proportion to the perceived gain that they appear ridiculous. Further, some have proposed that the lie in pathological lying is not altogether a conscious (or intentional) act even when it starts off initially as one.10

Confabulation

Confabulation describes falsifications of memory occurring in clear consciousness in association with organically derived amnesia. The patient attempts to cover exposed memory gaps with the confabulated materials. In pathological lying, there is no organically derived amnesia. In addition, the pattern of memory impairment in Confabulation is characteristic, mainly affecting recent memory, in the presence of intact immediate memory and attention and concentration. Confabulation occurs in Substance‐Induced Persisting Amnestic Disorder (Wernicke‐Korsakoff's syndrome), Anton's syndrome (cortical blindness), and anosognosia.

Ganser's Syndrome

The lie in Ganser's syndrome is limited to approximate answers, rather than the elaborate fantasies in pathological lying. In addition, Ganser's syndrome is associated with other features that do not characterize pathological lying: clouding of consciousness with subsequent amnesia regarding the episode, prominent hallucinations, and sensory changes of a hysterical kind.23

Factitious Disorder

In Factitious Disorder, the intentional production of symptoms (psychological or physical), often through false means, is solely for the purpose of assuming the role of a sick person. The pathological liar does not want to appear sick. DSM‐IV‐TR recognizes pseudologia fantastica as a common feature of Factitious Disorder, but one that is not essential for the diagnosis. Although Munchausen's syndrome comes under this diagnosis, the stories of Baron Von Munchausen (1720–1791), a German calvary officer after whom the syndrome was named by Asher,24 as reported by Rudolf Respe in 1785,25 were quite fantastic and dramatic and were not told for the purpose of his assuming the sick person's role, a crucial element in Factitious Disorder.

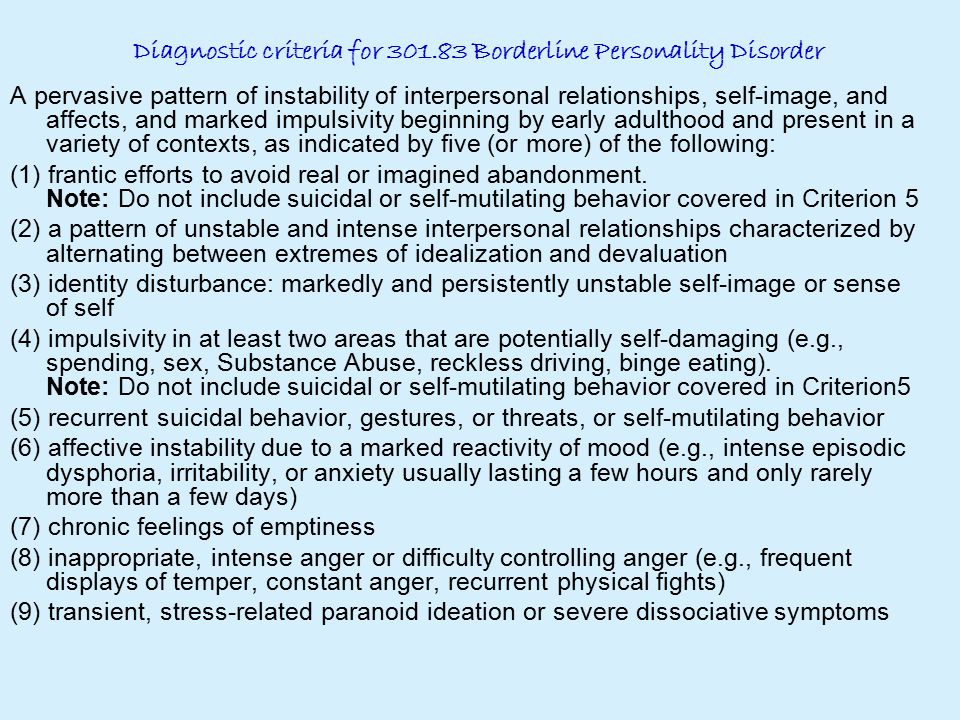

Borderline Personality Disorder

Pathological lying is not uncommon in patients with Borderline Personality Disorder.26 Indeed, the core characteristics of the latter disorder foster falsifications. These patients often lack a consistent self‐identity and hold contradictory views of themselves that alternate frequently. They are prone to loose thinking in unstructured situations and may suffer transient loss of reality testing. Such distortions of reality complicated by a lack of impulse control and the defense mechanisms of primitive denial, idealization, and devaluation are fertile grounds for pathological lying.

Antisocial Personality Disorder

Symptoms of this disorder listed in the DSM‐IV‐ TR include deceitfulness and repeated lying for personal profit or pleasure. Although it is debatable whether individuals with Antisocial Personality Disorder lie repeatedly and consistently for internal satisfaction alone, given their predominant picture of lying for personal profit, there is evidence that they do. 27 The pathological egocentricity characteristic of this condition may, however, be a key to development of pathological lying in these individuals. Although pathological lying may theoretically occur in Antisocial Personality Disorder, pathological liars do not often have disordered antisocial personalities.

27 The pathological egocentricity characteristic of this condition may, however, be a key to development of pathological lying in these individuals. Although pathological lying may theoretically occur in Antisocial Personality Disorder, pathological liars do not often have disordered antisocial personalities.

Histrionic and Narcissistic Personality Disorders

Histrionic Personality Disorder is characterized by dramatic and attention‐seeking behavior. These individuals frequently lie to attract attention and in severe cases, the lies may be so frequent as to resemble pseudologia fantastica. Their superficial and dramatic character and constant attention‐seeking behavior often point to a diagnosis of Histrionic Personality Disorder.

Individuals with Narcissistic Personality Disorder may tell ego‐boosting tales to obtain constant approval from others. In this condition, lies are mainly told for the reason of self‐aggrandizement, which is often obvious to the audience.

Delusions

These are false beliefs that are strongly held despite incontrovertible evidence to the contrary and that are generally not shared by others in the individual's cultural context. Unlike the delusional person, when strongly presented with clear evidence contrary to the lies told, the pathological liar may acknowledge, at least in part, the falsehood of his or her stories or more often, change stories. Although controversial, it is worth noting that some have suggested that pathological liars may believe their lies to such an extent that the beliefs appear delusional.

In summary, of the conditions discussed, only Factitious Disorder, Borderline Personality Disorder, Antisocial Personality Disorder, Histrionic Personality Disorder, and possibly Narcissistic Personality Disorder have an association with pathological lying.

Pathological Lying as a Diagnosis

While there is no doubt that pathological lying as a symptom may occur in Factitious Disorder and Borderline Personality Disorder, it is less clear whether it can stand on its own and occur independent of a known psychiatric disorder. Healy and Healy8 suggested that a clear distinction should be made between those who lie pathologically as a direct complication of a psychiatric disorder (secondary pathological liars, in our opinion), and pathological liars who do not demonstrate symptoms of a clearly defined psychiatric disorder (primary pathological liars). In fact, Healy and Healy argued that true pathological lying should be independent of a primary major psychiatric disorder. Both Judge Couwenberg and Professor Ellis repeatedly told false tales about their exploits, while at the same time pursuing high‐level professions and contributing to society. We have not had the privilege of examining either of them but media descriptions suggest that their lies were not driven by a primary major psychiatric disorder. Indeed, the psychiatrist who examined Judge Couwenberg concluded that he did not have a major psychiatric disorder. Going back into history, there is no evidence that Baron Von Munchausen had a psychiatric disorder; and, although Munchausen's syndrome was named after him, as far as we are aware, it was based solely on his pathological lies.

Healy and Healy8 suggested that a clear distinction should be made between those who lie pathologically as a direct complication of a psychiatric disorder (secondary pathological liars, in our opinion), and pathological liars who do not demonstrate symptoms of a clearly defined psychiatric disorder (primary pathological liars). In fact, Healy and Healy argued that true pathological lying should be independent of a primary major psychiatric disorder. Both Judge Couwenberg and Professor Ellis repeatedly told false tales about their exploits, while at the same time pursuing high‐level professions and contributing to society. We have not had the privilege of examining either of them but media descriptions suggest that their lies were not driven by a primary major psychiatric disorder. Indeed, the psychiatrist who examined Judge Couwenberg concluded that he did not have a major psychiatric disorder. Going back into history, there is no evidence that Baron Von Munchausen had a psychiatric disorder; and, although Munchausen's syndrome was named after him, as far as we are aware, it was based solely on his pathological lies.

Cleckley28 also described the case of a successful and respected man with a doctorate in physics, whose stories were filled with exaggerations and falsifications, sometimes conscious or half conscious. He noted that the man was not a psychopath or insane, but he had the attributes of pseudologia fantastica. These ego‐boosting lies, harmless as they may seem initially, may lead to serious difficulties for the liar when discovered. These examples, though centuries apart, suggest that pathological lying may occur in the absence of another diagnosable major psychiatric disorder.

Also of note is the description of “pseudology à deux” (Ref. 20, p 383) in the literature, a diagnosis akin to folie à deux but different in that pseudology rather than delusions are shared.20 Indeed, another article suggested that the primary diagnosis in the dominant partner in this variant of folie à deux is pathological lying, rather than psychosis,29—a further indication that pathological lying may exist as its own primary diagnostic entity.

Discussion

Clinical Questions

Despite the fact that lying is common, it is not clear why some individuals become pathological liars, whether it is a mental disorder, and if so, whether it is treatable. Although pathological lying was defined in the scientific literature over 100 years ago, it has remained poorly researched and its significance to the practice of psychiatry largely unclear. Indeed, its only mention in the DSM‐IV is in association with Factitious Disorder, but a review of the literature reveals a subgroup of individuals who exhibited pathological lying but without evidence of Factitious Disorder or any other overt psychiatric disorder.

Although many of these individuals may not have cause to seek treatment and may indeed continue to lead highly successful and productive lives, it is not uncommon for their lying to cause them hardship through clashes with the law or other authorities, with resultant adverse consequences. The consequence for Judge Couwenberg was removal from the bench. Judge Couwenberg's expert witness conceded that although the judge was suffering from pseudologia fantastica, he did not have a DSM‐IV diagnosable major psychiatric disorder. He noted, however, that pseudologia fantastica is treatable with therapy and did not render Judge Couwenberg unfit for judicial service. Although evidence for this latter clarification was not available for review, it is important because for pathological lying to be a desired defense strategy, it must be identified as an illness for which one could be treated and recover fully. Otherwise, the label could be quite damaging to one's reputation and credibility.

Pathological lying has been defined in various ways, and the core symptoms, possible etiological factors, and the effect on the individual's level of functioning are unclear. Further, it is unknown whether pathological lying exists across cultures, whether there are different subtypes of the phenomenon, and whether pathological liars present enough predominant, consistent, and stable symptoms or symptom clusters to delineate clearly a clinical entity fit for individual classification in the DSM. Systematic collection of data will help not only in clarifying these conundrums, but also in determining whether pathological lying is always only a symptom, a syndrome, or a diagnosis.

We anticipate the criticism that pathological lying is merely a behavioral symptom and not a diagnosis. Such a conclusion may, of course, be ultimately correct. However, we maintain that at present we lack the clinical evidence to draw a conclusion one way or the other.

Alternatively, if it cannot be considered a clinical entity in its own right, where should pathological lying be placed under currently existing psychiatric disorders in the DSM? For example, does it meet the criteria for an Impulse Control Disorder, given the impulsive nature of the lies, or should it simply be associated with one or several of the personality disorders? Obsessive Compulsive Disorder should also be considered, given the notion held by some that pathological liars feel compelled to repeat their mendacious acts.

The options available for treating pathological lying are also poorly researched. Scientific interest in pathological lying was prominent in the era preceding the development of psychotropic medications, and as a result, the treatment modality discussed consisted mainly of psychotherapy. Even so, the effectiveness of psychotherapy in the treatment of pathological lying has not been systematically studied. The recent report that up to 40 percent of cases of pseudologia fantastica have a history of central nervous system abnormalities,30 and the finding of right hemithalamic dysfunction by single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) in a case of pathological lying,31 suggest a possible role for pharmacotherapy or other interventions. Research in these areas could therefore fruitfully include the use of radioimaging and other studies for diagnosis and a systematic study of the effectiveness of pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, or the two in combination.

Forensic Implications

When the lies of pathological liars lead directly to a clash with the judicial system or with an administrative structure, psychiatrists may be asked to give advice about the nature of pathological lying. Untruths are of particular import in forensic assessments and present the expert with the challenge of sorting through the applicable differential diagnoses that may encompass pathological lying in a particular case. We certainly recommend that psychiatrists complete a thorough clinical evaluation of these individuals and obtain an extensive longitudinal history of the lying. Obtaining collateral information from relatives, employers, and other relevant associates would be particularly helpful, as would be a clear understanding of the individual's past legal entanglements. Attention should also be paid to clarifying external and internal objectives of the liar. We expect the evaluation to be better structured if the psychiatrist recalls the diagnostic entities potentially associated or confused with pathological lying. Psychological testing may also be helpful in establishing whether a psychotic disorder or malingering is present, or whether the lying is couched in particular personality traits. There is no specific psychological test currently available for the detection of pathological lying.

We wonder about the frequency of pathological lying in forensic psychiatry settings, and we expect that in these contexts a clearer definition is crucial. Psychiatrists have expressed differing opinions on substantive questions about pathological liars: Do they recognize their stories as false or believe them to be real? To the extent that they believe them as reality, is there a loss of reality testing? The answers to these questions may have implications for the arena of forensic psychiatry practice. One relevant concern would be whether an individual is considered responsible for any acts associated with pathological lying. Would it be feasible in some cases to assert that the lying was uncontrollable? We realize that pathological lying as a defense does not reach the threshold of insanity in most jurisdictions and we are certainly not advocating that it should. We believe, however, that when the behavior is properly framed for the prosecutors, the defendants may get some consideration.

A complicating factor in making assertions that pathological lying is uncontrollable is the observation that it may sometimes coexist with ordinary lies. Any evidence of lying for self‐benefit is likely to confuse the picture, even if the individual mostly tells pathological lies. Judge Couwenberg's misrepresentations of his educational qualifications were seen by the commission as examples of lying for direct promotion of his self‐interest, and even though some of his lies were not so easily explicable, he could not shake off the impression that his lies were for obvious gain. Another complicating factor is the observation that pathological liars usually have sound judgment in other matters. As stated earlier, this observation makes it difficult to prove that the pathological liar does not know that what he or she is doing is wrong.

When pathological liars deliver obviously false testimony under oath, is it legitimate to characterize such testimony simply as perjury or do these individuals deserve better framing of their behavior to get some dispensation from being held to the usual standards of truth‐telling? Judge Couwenberg repeatedly gave false testimony under oath but the commission observed that he did not have any mental condition that excused or mitigated his condition. According to the three‐judge panel sitting as masters, the possession of a “symptom” without any mental disorder is of little legal consequence. Indeed, repeatedly telling fantastic and unbelievable lies in an administrative law setting is likely to irritate the judge and produce a negative outcome.

A final question concerns whether a pathological liar is competent to stand trial. Could it be argued that the compulsively repeated lying prevents the pathological liar from effectively assisting his attorney in representing his case? Inability to present a consistent story and to bring relevant information to the attorney's attention is likely to confuse the attorney and impair the collaborative relationship between the defendant and his attorney.

The questions raised herein create a challenge for the forensic expert, both in formulating and in interpreting the findings to the court, jury, insurance company, or peers. Although consensus on the concept of pathological lying is a long way off, the forensic expert still needs a strategy for assessing the connection between pathological lying and the forensic problem at hand. When pathological liars get into trouble with the law or some other administrative entity, forensic examiners need to determine whether to make no recommendations or to argue for extenuating circumstances. We think that with the information provided herein, forensic psychiatrists may in certain cases be able to help attorneys frame an argument that may or may not ultimately be exculpatory, but that justifiably presents their clients in a more understandable way to the relevant authorities.

References

- ↵

State of California, Before the Commission on Judicial Performance: Decision and order removing Judge Couwenberg from office, August 15, 2001. Available at http://cjp.ca.gov/CN%20removals/couwdecision_sign.doc. Accessed December 13, 2003

- ↵

Robinson WV: Professor's past in doubt. The Boston Globe. June 18, 2001, pp A1, A6

- ↵

Langdon J: Lies Jeffery told me.

The Guardian, December 9, 1999. Available at http://www.guardian.co.uk/comment/story/0,3604,246410,00.html. Accessed November 6, 2002

- ↵

Smith D: Master storyteller or master deceiver. The New York Times. August 3, 2002, p B7

- ↵

Healy P, Robinson WV: Professor apologizes for fabrications. The Boston Globe. June 19, 2001, pp A1, A12

- ↵

Delbruck A: Die pathologische Luge und die psychisch abnormen Schwindler: Eine Untersuchung uber den allmahlichen Uebergang eines normalen psychologischen Vorgangs in ein pathologisches Symptom, fur Aerzte und Juristen. Stuttgart, 1891, p 131. Translated by Healy W, Healy MT: Pathological lying, accusation and swindling, in Patterson Smith Reprints Series in Criminology, Law Enforcement, and Social Problems. Edited by Gault RH, Crossley FB, Garner JW. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969

- ↵

Bursten B: The manipulative personality.

Arch Gen Psychiatry 26:318–21, 1972

- ↵

Healy W, Healy MT: Pathological Lying, Accusation, and Swindling. Boston: Little, Brown, 1926

- ↵

Selling LS: The psychiatric aspects of the pathological liar. Nerv Child 1:335–50, 1942

- ↵

Hoyer TV: Pseudologia fantastica. Psychiatr Q 33:203–20, 1959

- ↵

Schneider K: Clinical Psychopathology (translated by Hamilton MW). New York: Grune and Stratton, 1959

- ↵

Bleuler E: Textbook of Psychiatry. New York: The Macmillan Company, 1924

- ↵

Jaspers K: General Psychopathology (translated by Hoenig J, Hamilton MW). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1963

- ↵

Fish F. Clinical Psychopathology. Bristol, UK: John Wright, 1967

- ↵

Koppen M: Über die pathologische Luge (Pseudologia phantastica).

Charite‐Annalen 8:674–719, 1898. Translated by Healy W, Healy MT: Pathological lying, accusation and swindling, in Patterson Smith Reprints Series in Criminology, Law Enforcement, and Social Problems. Edited by Gault RH, Crossley FB, Garner JW. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969

- ↵

Meunier R: Remarks on three cases of morbid lying. J Ment Pathol 6:140–2, 1904

- ↵

Stemmermann A: Beitrage und Kasuistik der Pseudologia phantastica. Berlin: Geo. Reimer, 1906, p 102. Translated by Healy W, Healy MT: Pathological lying, accusation and swindling, in Patterson Smith Reprints Series in Criminology, Law Enforcement, and Social Problems. Edited by Gault RH, Crossley FB, Garner JW. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969

- ↵

Vogt H: Jugendliche Lugnerinnen. Zeitschrift fur Erforschung d. jugend. Schwachsinns Bd. 3. H. 5:394–438, 1910. Translated by Healy W, Healy MT: Pathological lying, accusation and swindling, in Patterson Smith Reprints Series in Criminology, Law Enforcement, and Social Problems.

Edited by Gault RH, Crossley FB, Garner JW. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969

- ↵

Wiersma D: On pathological lying. Character Personal 2:48–61, 1933

- ↵

Deutsch H: On the pathological lie (pseudologia phantastica). J Am Acad Psychoanal 10:369–86, 1982

- ↵

Wendt E: Ein Beitrag zur Kasuistik der Pseudologia phantastica. Allgemeine Zeitschrift fur Psychiatrie 68:482–500, 1911. Translated by Healy W, Healy MT: Pathological lying, accusation and swindling, in Patterson Smith Reprints Series in Criminology, Law Enforcement, and Social Problems. Edited by Gault RH, Crossley FB, Garner JW. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969

- ↵

Risch B: ber die Phantastische form des degenerativen Irreseins (Pseudologia phantastica). Allgemeine Zeitschrift fur Psychiatrie 65:576–639, 1908. Translated by Healy W, Healy MT: Pathological lying, accusation and swindling, in Patterson Smith Reprints Series in Criminology, Law Enforcement, and Social Problems.

Edited by Gault RH, Crossley FB, Garner JW. Montclair, NJ: Patterson Smith, 1969

- ↵

Enoch MD, Trethowan WH: The Ganser syndrome, in Uncommon Psychiatric Syndromes. Bristol, UK: John Wright, 1979, pp 50–62

- ↵

Asher R: Munchausen's syndrome. Lancet 1:339–41, 1951

- ↵

Raspe RE: The adventures of Baron Munchausen. New York: Pantheon Books, 1969

- ↵

Snyder S: Pseudologia fantastica in the borderline patient. Am J Psychiatry 143:1287–9, 1986

- ↵

Weston WA, Dalby JT: A case of pseudologia fantastica with Antisocial Personality Disorder. Can J Psychiatry 36:612–14, 1991

- ↵

Cleckley H: The Mask of Sanity. St. Louis: CV Mosby, 1955

- ↵

Casey PR: An unusual variant of folie a deux? Irish J Psychol Med 6:44–6, 1989

- ↵

King BH, Ford CV: Pseudologia fantastica.

Acta Psychiatr Scand 77:1–6, 1988

- ↵

Modell JG, Mountz JM, Ford CV: Pathological lying associated with thalamic dysfunction demonstrated by [99mTc] HMPAO SPECT. J Neuropsychiatry 4:442–6, 1992

PreviousNext

Back to top

Fiddler of the Truth | Psychology Today

Writings relating to pathological lying first appeared in the psychiatric literature over 100 years ago and have been given names such as "pseudologia fantastica" and "mythomania" and often used interchangeably. There is some consensus that Dr. Anton Delbruck, a German physician, was the first person to describe the concept of pathological lying in 1891 after publishing an account of five of his patients.

Despite the long history of research, pathological lying is not included in either the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5) or the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10). The only mention of pathological lying in the DSM is in association with Factitious Disorder (discussed below), however, many psychologists and psychiatrists claim that it is a distinct psychiatric disorder, as highlighted in the many papers that have been published on the topic over the last two decades.

At a very simplistic level, pathological lying refers to a person that incessantly tells lies. However, Dr. Charles Dike and his colleagues in a 2005 issue of the Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and Law define it as "falsification entirely disproportionate to any discernible end in view, may be extensive and very complicated, and may manifest over a period of years or even a lifetime, in the absence of definite insanity, feeble-mindedness or epilepsy."

However, there are other psychiatric conditions (such as people with manipulative personality) that may also engage in pathological lying as part of a wider set of behaviours and symptoms. In fact, there is a lot of debate as to whether the behaviour is really a discrete and unique entity or whether it typically manifests itself as an adjunct to other recognized psychological and/or psychiatric conditions. Dr. Dike and colleagues note that:

“Pathological liars can believe their lies to the extent that, at least to others, the belief may appear to be delusional; they generally have sound judgment in other matters; it is questionable whether pathological lying is always a conscious act and whether pathological liars always have control over their lies; an external reason for lying (such as financial gain) often appears absent and the internal or psychological purpose for lying is often unclear; the lies in pathological lying are often unplanned and rather impulsive; the pathological liar may become a prisoner of his or her lies; the desired personality of the pathological liar may overwhelm the actual one; pathological lying may sometimes be associated with criminal behavior; the pathological liar may acknowledge, at least in part, the falseness of the tales when energetically challenged; and, in pathological lying, telling lies may often seem to be an end in itself. However, it is evident that no single descriptive tableau of a pathological liar settles all the nosological and etiological questions raised by the phenomenon of pathological lying.

” (p.344)

Dike and colleagues then went on to list a wide range of psychiatric conditions that have been associated with pathological lying in an attempt to contextualize how the lying behaviour is manifested within these known conditions. The list of psychological and psychiatric conditions included: (i) Malingering, (ii) Confabulation, (iii) Ganser’s Syndrome, (iv) Factitious Disorder, (v) Borderline Personality Disorder, (vi) Antisocial Personality Disorder, (vii) Histrionic Personality Disorders. Arguably, it is these last three disorders with which pathological lying is most associated. The following briefly describes the symptoms and context of each of these conditions as outlined by Dr. Dike and his colleagues:

- Malingering: This is deliberate lying where the person grossly exaggerates or totally lies about physical and/or psychological symptoms. Unlike "archetypal" pathological liars, malingerers are typically motivated to tell lies for a specific purpose, such as to obtain financial compensation, to avoid working, to avoid military service, to avoid criminal prosecution, etc.

- Confabulation: This is where people tell lies incessantly as a way of covering up memory lapses caused by specific memory loss conditions (e.g., organically derived amnesia). In archetypal pathological liars, the condition is psychological (rather than organic) in origin.

- Ganser’s Syndrome (GS): GS is a rare dissociative disorder (only 101 recorded cases ever) characterized by affected people giving nonsensical answers to questions (and goes under many other names including "nonsense syndrome" and "balderdash syndrome"). Unlike the elaborate and sometimes fantastical stories told by archetypal pathological liars, the lies told by those with GS are very simplistic and approximate.

- Factitious Disorder (FD): FD is the deliberate use of lies and/or exaggerations concerning psychological and/or physical symptoms solely for the purpose of assuming the role of a sick person (formerly known as Munchausen’s Syndrome). In contrast, the archetypal pathological liar doesn’t want to appear sick to other people.

- Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD): BPD is a condition where people have long-term patterns of unstable and/or turbulent emotions. Pathological lying and being deceitful are not core characteristics of BPD, according to the DSM, but some with BPD do engage in lies. BPD patients typically lack a consistent self-identity and impulse control, which may facilitate the distortions or lies told.

- Antisocial Personality Disorder (APD): APD is the condition in which the sufferer has a long-term pattern of manipulating, exploiting, or violating the rights of others (and is often criminal). Those with APD often lie repeatedly and consistently for personal satisfaction alone. Although those with APD are often pathological liars, archetypal pathological liars rarely have disordered antisocial personalities.

- Histrionic Personality Disorder (HPD): Those with HPD act in a highly emotional and dramatic way to draw attention to themselves. They often lie as a way to enhance and/or facilitate their dramatic and attention-seeking behaviour.

In contrast, archetypal pathological liars do not constantly seek attention.

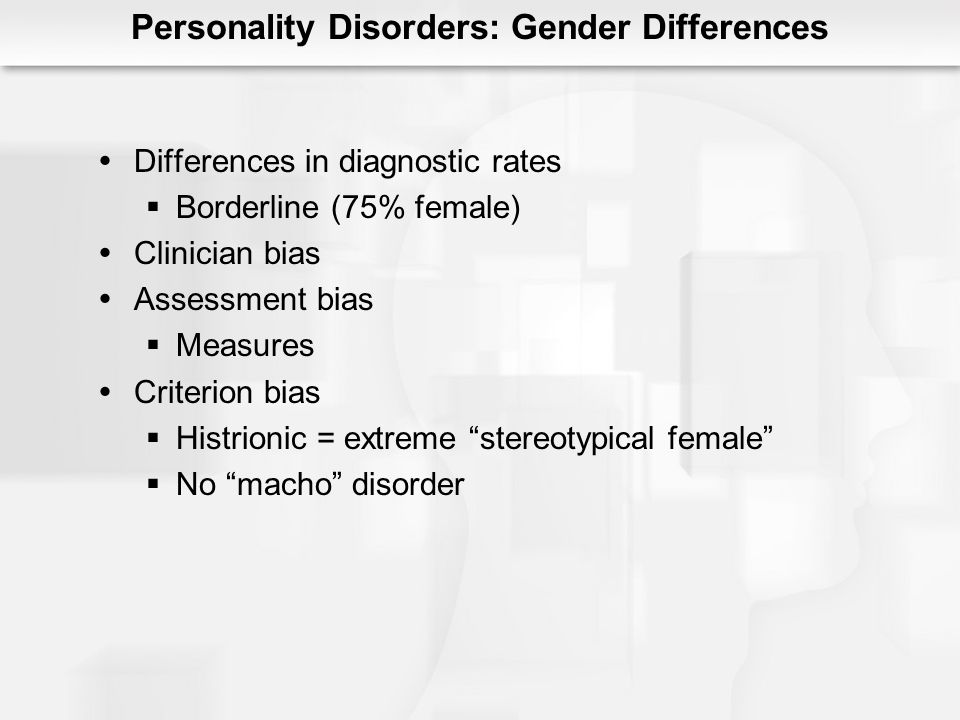

Based on the list above, it is evident that the symptom of pathological lying can occur in some mental disorders (e.g., FD) and could be called secondary pathological lying. However, it is much less clear whether it can occur independently of a known psychiatric disorder and be seen as primary pathological lying. Unlike the other forms of lying outlined above, Dr. Dike says pathological lying appears to be unplanned and impulsive. Despite all the speculation, there is still relatively little known, although it’s thought to affect men and women equally, with an onset in late adolescence. There are no reliable prevalence figures, although one study estimated that one in 1,000 repeat juvenile offenders suffered from it.

On a biological and neurological level, a paper published in the Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences by Dr. J.G. Modell and colleagues reported the case of a pathological liar who was given a brain scan. Results showed that his condition was associated with right hemithalamic dysfunction. This supported the hypothesized roles of the thalamus and associated brain regions in the modulation of behavior and cognition.

A 2007 study published in the British Journal of Psychiatry by Dr. Y. Yang and colleagues reported differences in brain structure between pathological liars and control groups. Pathological liars showed a relatively widespread increase in white matter (approximately one-quarter to one-third more than controls) and the authors suggested that this increase may predispose some individuals to pathological lying.

Those working in the mental health system need to pay attention to pathological lying so that they can inform legal practitioners about whether pathological liars should be held responsible for their behaviour. Whether pathological liars are aware of the lies they tell has major implications for forensic psychiatry practice. Dr. Dike says it could help determine how a court deals with pathological liars who provide false testimony while under oath.

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Borderline mental disorders››

Hysterical personality disorder, or hysterical type of psychopathy. Hysterical reactions (stigmas, fainting, etc.) and other forms of hysterical behavior (extravagance, a tendency to dramatize trivial situations, the desire to be in the spotlight), characteristic of this type of psychopathy, are quite widespread and are often observed in psychopathic personalities of other types with the development of neurotic reactions or reactive psychoses. Hysterical psychopathy is characterized not only by psychogenic hysterical reactions and behaviors, but also by a certain personality type. These people are internally empty, sometimes empty and even miserable; external impressions play the greatest role in the balance of their mental life. They do not have their own opinion, their own established views on life; their judgments lack maturity, seriousness, and depth. Their behavior is not dictated by internal motives, but is calculated for an external effect. The desire to attract attention to oneself, the "thirst for recognition", a tendency to imitate, fiction and fantasies, capriciousness are noted in tantrums even in the preschool period. In adolescence and youth, along with this, their egocentrism, disorganization, a tendency to frivolous acts, wastefulness, and various adventures come out more clearly. They are incapable of systematic, hard work, prefer amateurish activity when choosing their occupation and succumb to tasks that require perseverance, thorough knowledge and solid professional training. Most of all, they like an idle life with external, ostentatious splendor, various entertainments, and frequent changes of impressions. They willingly and selflessly perform the rituals of festivities and banquets, strive to follow fashion in everything, attend successful performances, “idolize” popular artists, discuss sensational books, etc.

For the most part, they are gullible, easily attached to people. At the same time, a tendency to eroticize interpersonal relationships is often found [Yakubik A. , 1982]; quickly fall in love, starting numerous, often short-lived novels, accompanied at first by violent manifestations of feelings. However, being fickle in their hobbies, they cool down just as quickly. In more rare cases, persistent ecstatic attachments are formed, which are formed according to the type of overvalued formations [Dubnitskaya E. B., 1979; Filts A. O., 1987].

As K. Jaspers (1923) points out, one of the main properties of hysterics is the desire to appear larger than they really are, to experience more than they are able to survive. Some try to emphasize their talent, while operating with very superficial information from various fields of science and art, others exaggerate their social position, hinting at close ties with high-ranking officials; others, without stinting on promises, talk about their vast possibilities, which in fact turn out to be the fruit of their rich imagination. Hysterics use everything possible to be in the spotlight: eccentricity in clothing, “flashy” forms of external behavior, unusual actions that contrast with generally accepted views, allegedly mysterious symptoms of an unknown illness, fainting, etc.

A feature of the hysterical psyche is also the absence of clear boundaries between the products of one's own imagination and reality. Focusing on this property, P. B. Gannushkin emphasizes that the real world for a person with a hysterical psyche acquires a peculiar bizarre shape; the objective criterion for him is lost, which often gives those around him a reason to accuse such a person, at best, of lying and pretense. The hysteric perceives the processes in his own body and his own psyche in the same way. Some experiences completely escape his attention, while others, on the contrary, are evaluated extremely thinly. Because of the brightness of some images and ideas and the pallor of others, a person with a hysterical mentality very often does not see the difference between fantasy and reality, between what happened in reality and what was seen in a dream, or, more precisely, is not able to do it.

The prognosis for hysterical psychopathy in general cannot be considered unfavorable. In adulthood, with good social conditions and a working environment, in most cases, long-term and stable compensation is possible [Semke V. Ya., 1988]. During this period, the pathocharacterological structure of hysterical psychopathy largely coincides with the accentuated personalities of the “demonstrative” type described by K. Leonhard (1968). Compensated hysterical psychopathic personalities are infantile, youthfully graceful, with emphasized plasticity and expressiveness of movements. Among them there are people with a certain stage talent, artistic natures, but also poseurs and "dandies", dressed with exaggerated elegance. With age, they become smoother and more serious, acquire the necessary labor skills, but the elements of theatricality in behavior remain; First of all, this is reflected in the ability to make a good, favorable impression for oneself, to arouse sympathy, and if necessary, sympathy. Most fully in hysterical psychopathy, compensation processes occur in the case of a predominance of psychopathic manifestations of a tendency to various autonomic and hysterical paroxysms (spasms, a feeling of suffocation during excitement, globus hystericus, nausea, vomiting, aphonia, tremor of the fingers, numbness of the extremities and other sensitivity disorders).

Already by the age of 30-35, such psychopathic personalities are sufficiently adapted to the real situation, they can correct their behavior. In life, these are emphasized obligatory people, diligent, successfully coping with their professional duties, maintaining fairly strong family ties. However, with such variants of hysterical psychopathy, the risk of decompensation at involutionary age is more likely, which is often associated with a deterioration in the somatic condition (hypertension, coronary artery disease and other diseases) and menopause. Manifestations of decompensation (usually in the form of emotional instability, violent hysterical reactions and paroxysms) in more severe cases correspond to the clinic of involutional hysteria [Geyer T.I., 1925]. Along with increasing depression, asthenia, tearfulness, anxious fears for one's health, more persistent hypochondriacal symptoms, accompanied by various algias, conversion and vegetative disorders, may come to the fore.

The prognosis is less favorable in the case of a predominance in the structure of the hysterical personality of a tendency to pathological fantasizing. Such psychopathic personalities are distinguished by some authors into a separate group - pathological swindlers and pseudologists according to A. Delbruck (1891), mythomaniacs according to E. Durpe (1909), liars and deceivers according to E. Kraepelin (1915), pathological liars according to P. B. Gannushkin (1964). These people lie from a young age, sometimes without any reason or meaning. Some get so used to the situations created by their imagination that they themselves believe in them. Some can enthusiastically talk about journeys into the remote taiga as part of a geological expedition in which they have never participated; others, having no medical education, describe as if they performed complex surgical operations. Fantasies sometimes turn into self-incrimination with confessions to fictional crimes and even murders. Decompensation, usually quite frequent, occurs either already in the school years, or somewhat later, with the transition to independent activity. For the first time after starting a job or moving to a new place, they impress others as thoughtful, conscientious, enterprising, gifted specialists.

However, their complete failure is soon discovered. They are extremely frivolous about the assigned work, incapable of systematic work, instead of real problems, they are busy with fantastic fictions. Compared to ordinary hysterics, as G. E. Sukhareva points out, pseudologists are more active in their desire to realize their plans. It's not always an innocent lie. More often, certain selfish goals are pursued, which leads to a collision with the law. A motley gallery of petty swindlers, soothsayers, marriage swindlers, charlatans posing as doctors, or extortionists who accept valuable gifts and cash advances for services that they can never provide is formed from among the pseudologists.

Some taxonomies (DSM-IV) distinguish narcissistic personality disorder, having in common with hysterical psychopathy. The definition of "narcissus" goes back to Greek mythology (Narcissus fell in love 1 with his own reflection in the water and died while trying to hug him). Conceptualization of the concept "narcissistic" belongs to Z. Freud. Later, the concept of narcissism developed in the context of psychoanalytic research. The term "narcissistic personality disorder" was introduced by H. Kohut in 1968. Narcissistic and hysterical personality disorder bring together the features of demonstrativeness, a tendency to dramatize, a thirst for recognition, but significant differences are also found. Narcissistic personalities are characterized by pathological ambition, conceit, arrogance, a sense of superiority over others. "Narcissists" are always confident in their significance, correctness, cannot stand criticism, tend to exaggerate their knowledge and achievements (narcissistic falsification of reality according to H. Kohut, 1971). The ability to work effectively is often combined with the pursuit of universal attention and admiration. The choice of progression also corresponds to this goal: they are not satisfied with activities that do not promise quick fame and public recognition.

If hysterical personalities retain the ability to care for their neighbors and love them, then narcissists are devoid of empathy, indifferent to the interests and feelings of others, “perceive others as a faceless applauding mass” [Svrakic D. M., 1989].

10 signs of a personality disorder | PSYCHOLOGIES

188 969

A person among people

In most cases it is difficult to communicate with such people, they often like to argue over trifles and are very stubborn. A person with a personality disorder perceives reality in a distorted form, and these symptoms appear in any situation.

This diagnosis is not made before the age of 18. However, this requires that symptoms have been continuously present for the previous five years. There are several main types of personality disorders: antisocial, narcissistic, borderline, hysterical, obsessive-compulsive, paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, dependent and avoidant. There are several other varieties, but they are beyond the scope of our discussion.

Here are 10 signs that allow you to suspect a personality disorder in a person:

1. He constantly has mutual misunderstanding with others. He often hears in the words of others what they did not actually say. The narcissist feels that he is idealized, although he is far from ideal, and the person suffering from avoidant personality disorder in the words of others hears contempt and anger, which in fact are not there. Such a person hears in the words of others the content of his own internal dialogue (uncertainty or a sense of superiority).

2. He perceives reality incorrectly. Incorrectly interpreting other people's words, such people often have wrong ideas about what kind of relationship they are with others and what status they occupy in society. For example, hysterical personalities quickly begin to consider themselves the best friends of the person they just met, not realizing that their new acquaintance does not think so.

3. They often spoil the pleasure of others. For example, they tell how the movie will end, come up with unlikely reasons why someone's plans may fail, spoil the mood of others by making scenes over trifles. They do all this to be in the spotlight, to prove to others that they are smart and right - a typical manifestation of obsessive-compulsive and narcissistic traits.

4. They don't understand that no means no. Tendency to violate the personal boundaries of others is a typical symptom. Those suffering from these disorders do not recognize the right of others to set limits and easily violate any boundaries they do not like. People with antisocial and borderline personality disorders violate other people's boundaries for other reasons - the former enjoy it, while the latter often do not even realize that they are violating something.

5. They try to make themselves a victim. To avoid responsibility, people with personality disorders tend to portray themselves as victims, for example, talking about their difficult childhood and chronic psychological trauma. But it is one thing for a patient with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) to suffer from difficult memories, and quite another when a person tries to manipulate others or avoid responsibility by portraying himself as a victim and talking about a difficult past. Paranoid, dependent or antisocial personalities are especially prone to this.

6. They have an imbalance in personal relationships. Some disorders (borderline, hysteria, and addiction) are characterized by too close and emotional relationships, while others (with narcissistic, avoidant, schizoid, schizotypal, obsessive-compulsive or antisocial disorder), on the contrary, have almost no emotional closeness. In any case, relationships are built unbalanced - either too close, or cold and distant.

7. It is very difficult for them to change themselves. Growth and development are almost impossible for such people. They can change, but very slowly. It is usually not possible to completely get rid of the disorder, with the exception of borderline disorder: studies show that it responds well to certain types of psychotherapy.

8. They put the blame on others. If a person comes to a psychotherapist with a partner, he often tries to show himself to be perfect, and the partner is almost crazy. It is not uncommon for people with obsessive-compulsive disorder to bring a paper to the therapist listing all of their partner's shortcomings. When their mistakes and shortcomings are pointed out to them, they try to blame someone else for them.

9. They are prone to outright lies. It's one thing to lie to save someone's feelings (this is something people with personality disorders don't usually care about), and quite another to lie outright to protect themselves. Such individuals cannot admit that they are the problem and resort to deception. And if they do, they usually do it as dramatically as possible, trying to win over the interlocutor. The most dangerous lie of a person with antisocial personality disorder, often it threatens others with real mental trauma.

10.