Mixed episode description

Mixed Bipolar Disorder Symptoms, Causes, and Treatments

Written by Matthew Hoffman, MD

In this Article

- What Are Mixed Episodes in Bipolar Disorder?

- Who Gets Mixed Bipolar Episodes?

- What Are the Symptoms of a Mixed Features Episode?

- What Are the Risks of Mixed Features During Mood Episodes of Bipolar Disorder?

- What Are the Treatments for Mood Episodes With Mixed Features in Bipolar Disorder?

What Are Mixed Episodes in Bipolar Disorder?

Mixed features refers to the presence of high and low symptoms occurring at the same time, or as part of a single episode, in people experiencing an episode of mania or depression. In most forms of bipolar disorder, moods alternate between elevated and depressed over time. A person with mixed features experiences symptoms of both mood "poles" -- mania and depression -- simultaneously or in rapid sequence.

Who Gets Mixed Bipolar Episodes?

Virtually anyone can develop bipolar disorder. About 2.5% of the U.S. population -- nearly 6 million people -- has some form of bipolar disorder.

Mixed episodes are common in people with bipolar disorder -- half or more of people with bipolar disorder have at least some mania symptoms during a full episode of depression. Those who develop bipolar disorder at a younger age, particularly in adolescence, may be more likely to have mixed episodes. People who develop episodes with mixed features may also develop "pure" depressed or "pure" manic or hypomanic phases of bipolar illness. People who have episodes of major depression but not full episodes of mania or hypomania also can sometimes have low-grade mania symptoms. These are symptoms that are not severe or extensive enough to be classified as bipolar disorder. This is referred to as an episode of "mixed depression" or a unipolar (major) depressive episode with mixed features.

Most people are in their teens or early 20s when symptoms from bipolar disorder first start. It is rare for bipolar disorder to develop for the first time after age 50. People who have an immediate family member with bipolar are at higher risk.

It is rare for bipolar disorder to develop for the first time after age 50. People who have an immediate family member with bipolar are at higher risk.

What Are the Symptoms of a Mixed Features Episode?

Mixed episodes are defined by symptoms of mania and depression that occur at the same time or in rapid sequence without recovery in between..

- Mania with mixed features usually involves irritability, high energy, racing thoughts and speech, and overactivity or agitation.

- Depression during episodes with mixed features involves the same symptoms as in "regular" depression, with feelings of sadness, loss of interest in activities, low energy, feelings of guilt and worthlessness, and thoughts of suicide.

This may seem impossible. How can someone be manic and depressed at the same time? The high energy of mania with the despair of depression are not mutually exclusive symptoms, and their co-occurrence may be much more common than people realize.

For example, a person in an episode with mixed features could be crying uncontrollably while announcing they have never felt better in their life. Or they could be exuberantly happy, only to suddenly collapse in misery. A short while later they might suddenly return to an ecstatic state.

Mood episodes with mixed features can last from days to weeks or sometimes months if untreated. They may recur ,and recovery can be slower than during episodes of "pure" bipolar depression or "pure" mania or hypomania.

What Are the Risks of Mixed Features During Mood Episodes of Bipolar Disorder?

The most serious risk of mixed features during a manic or depressive episode is suicide. People with bipolar disorder are 10 to 20 times more likely to commit suicide than people without bipolar disorder. Tragically, as many as 10% to 15% of people with bipolar disorder eventually lose their lives to suicide.

Evidence shows that during episodes with mixed features, people may be at even higher risk for suicide than people in episodes of bipolar depression.

Treatment reduces the likelihood of serious depression and suicide. Lithium (Eskalith, Lithobid) in particular, taken long term, may help to reduce the risk of suicide.

People with bipolar disorder are also at higher risk for substance abuse. Nearly 60% of people with bipolar disorder abuse drugs or alcohol. Substance abuse is associated with more severe or poorly controlled bipolar disorder.

What Are the Treatments for Mood Episodes With Mixed Features in Bipolar Disorder?

Manic or depressive episodes with mixed features generally require treatment with medication. Unfortunately, such episodes are more difficult to control than an episode of pure mania or depression. The main drugs used to treat episodes with mixed features are mood stabilizers and antipsychotics.

Mood Stabilizers

While lithium is often considered a gold standard treatment for mania, it may be less effective when mania and depression occur simultaneously, as in a manic episode with mixed features. Lithium has been used for more than 60 years to treat bipolar disorder. It can take weeks to work fully, making it better for maintenance treatment than for acute manic episodes. Blood levels of lithium and other lab test results must be monitored to avoid side effects.

Lithium has been used for more than 60 years to treat bipolar disorder. It can take weeks to work fully, making it better for maintenance treatment than for acute manic episodes. Blood levels of lithium and other lab test results must be monitored to avoid side effects.

Valproic acid (Depakote) is an antiseizure medication that also levels out moods in bipolar disorder. It has a more rapid onset of action, and in some studies has been shown to be more effective than lithium for the treatment of manic episodes with mixed features.

Some other antiseizure drugs, such as and carbamazepine (Tegretol) and lamotrigine (Lamictal), are also effective mood stabilizers.

Antipsychotics

Many atypical antipsychotic drugs are effective FDA-approved treatments for manic episodes with mixed features. These includearipiprazole (Abilify), asenapine (Saphris), cariprazine (Vraylar), olanzapine (Zyprexa), quetiapine (Seroquel), risperidone (Risperdal), and ziprasidone (Geodon). Antipsychotic drugs are also sometimes used alone or in combination with mood stabilizers for preventive treatment.

Antipsychotic drugs are also sometimes used alone or in combination with mood stabilizers for preventive treatment.

Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT)

Despite its frightening reputation, electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is an effective treatment for any phase of bipolar disorder, including manic episodes with mixed features. ECT can be helpful if medication fails or can't be used.

Treatment for Depression in Mixed Bipolar Disorder

Common antidepressants such as fluoxetine (Prozac, Sarafem), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft) have been shown to worsen mania symptoms without necessarily improving depressive symptoms when depressive and manic symptoms occur together. Most experts therefore advise against using antidepressants during episodes with mixed features. Mood stabilizers (particularly Depakote), as well as atypical antipsychotic drugs, are considered the first-line treatments for mood episodes with mixed features.

Bipolar disorder usually involves recurrences of mixed, manic, or depressed phases of illness. Therefore, it is usually recommended that medications be continued in an ongoing fashion after an acute episode resolves in order to prevent relapses. This is sometimes called maintenance treatment.

Therefore, it is usually recommended that medications be continued in an ongoing fashion after an acute episode resolves in order to prevent relapses. This is sometimes called maintenance treatment.

Bipolar Disorder Guide

- Overview

- Symptoms & Types

- Treatment & Prevention

- Living & Support

This Is What a Mixed Bipolar Episode Feels Like

Health

Related Condition Centers

- Bipolar Disorder

- Mental Health

- Depression

“The manic energy just drives the depression.”

By Jacqueline Andriakos

Stuart Kinlough/Getty Images

Bipolar disorder is a condition in which a person experiences dramatic shifts in mood and energy, but at severities that are different from the mood changes the average person goes through. But a common misconception about bipolar disorder is that a person with the diagnosis only experiences two distinct moods: either really high highs (mania), or really low lows (depression). For starters, people with bipolar disorder are not always experiencing symptoms, known as bipolar “episodes.” Plus, these episodes aren't always as simple as high or low.

But a common misconception about bipolar disorder is that a person with the diagnosis only experiences two distinct moods: either really high highs (mania), or really low lows (depression). For starters, people with bipolar disorder are not always experiencing symptoms, known as bipolar “episodes.” Plus, these episodes aren't always as simple as high or low.

Many episodes that people with a bipolar diagnosis experience are considered “mixed” episodes, sometimes also described as “switching” episodes, or manic/hypomanic or depressive episodes with mixed features. A mixed episode signals that the person is experiencing both aspects of mania or hypomania as well as symptoms of bipolar depression.

Before we get into mixed episodes, let’s go over what constitutes a standard episode of mood elevation (mania or hypomania) versus a depressive episode.

“Bipolar historically was known as manic depression, and some people will still call it that. So it makes sense to me that many people only associate it with two sort of categories of mood, those being mania and depression,” Wendy Marsh, M. D., director of the Bipolar Disorders Specialty Clinic and an associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, tells SELF.

D., director of the Bipolar Disorders Specialty Clinic and an associate professor in the department of psychiatry at the University of Massachusetts Medical School, tells SELF.

Symptoms associated with an episode of bipolar depression include lower energy and/or activity levels, difficulty concentrating, loss of interest in things, and changes in appetite and sleep, among others. “And to classify as having an episode of depression, you need to be experiencing a gateway symptom of either a sad mood or loss of interest in life pervasively, in addition to at least five of the other symptoms for two weeks,” Dr. Marsh says.

To classify an episode as a mood elevation—meaning mania or hypomania—you must exhibit a prolonged, unusual, high-energy mood, while also showing at least three additional symptoms of mood elevation, including (but not limited to) feeling a sense of euphoria, having increased energy and/or self-esteem, racing thoughts, reduced sleep, and others. (If someone experiences hallucinations or psychosis or is hospitalized as a result of manic symptoms, this would also be considered mania. )

)

A

mixed bipolar episode is when a person experiences depressive symptoms and those of a mood elevation at the same time.Dr. Marsh points out that “bipolar” is somewhat of a misnomer, “because while there are two poles, they’re not necessarily experienced separately,” she says. “This can be a very hard concept to grasp for someone observing a patient who is having symptoms associated with both poles at the same time, and for the patients themselves.”

With bipolar disorder in general, it’s actually quite common for a person to experience episodes that are mixed, Igor Galynker, M.D., associate chairman for research in the department of psychiatry at Mount Sinai Beth Israel, tells SELF. (Research suggests an estimated 20 to 40 percent of people with bipolar have mixed episodes.)

Most Popular

The fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) included specific diagnostic criteria for mixed episodes, Dr. Marsh says. But the DSM-5, the latest version of the manual, replaced the “mixed episode” diagnosis with a “mixed-features specifier” that clinicians now apply to episodes of depression, hypomania, or mania. The issue that some researchers took with the DSM-4 mixed episode diagnosis was that it required a person to meet the complete diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode, as well as the full criteria for a manic episode, for a week or longer. “Simply put, you had to be experiencing ongoing full mania and full depression simultaneously,” Dr. Marsh says. But in reality, a person may present mixed features but not necessarily check every single diagnostic box for both.

Marsh says. But the DSM-5, the latest version of the manual, replaced the “mixed episode” diagnosis with a “mixed-features specifier” that clinicians now apply to episodes of depression, hypomania, or mania. The issue that some researchers took with the DSM-4 mixed episode diagnosis was that it required a person to meet the complete diagnostic criteria for a depressive episode, as well as the full criteria for a manic episode, for a week or longer. “Simply put, you had to be experiencing ongoing full mania and full depression simultaneously,” Dr. Marsh says. But in reality, a person may present mixed features but not necessarily check every single diagnostic box for both.

According to the latest edition of the DSM, a bipolar episode may be clinically classified as having mixed features if a person is experiencing one mood episode along with at least three symptoms of the opposite mood episode for the majority of the time. So, for instance, you may have a week-long manic episode with at least three symptoms of a depressive episode for five of those days. You can find a list of diagnostic symptoms for mania/hypomania and depression here. And it’s worth noting that episodes with mixed features can present in both bipolar I and II.

You can find a list of diagnostic symptoms for mania/hypomania and depression here. And it’s worth noting that episodes with mixed features can present in both bipolar I and II.

So what does a mixed episode look like exactly?

This will typically depend on which mood episode is the predominant one—for instance, are you having a manic/hypomanic episode with symptoms of depression, or having a depressive episode with symptoms of mania? In some cases, a person presenting mixed features may be in a full mania and a full depression at the same time; in other cases, a person may be experiencing all of the symptoms of mania/hypomania and only a few depressive symptoms (or the other way around). “Bipolar is not an alternating disorder of mood, it’s a dysregulation of mood,” Dr. Galynker says. “The mood can be all over the place.”

Speaking generally, “This is a person who is really ramped up, their thoughts are racing, they’re talking a mile a minute, they don’t need as much sleep—mood elevations symptoms,” Dr. Marsh explains. “But at the same time, they feel sad and blue, they’re beating themselves up in their head, their self-worth is down.” Dr. Marsh also says a person experiencing a mixed episode commonly has thoughts of escaping the misery or even death. “While they may not have suicidal ideation, they may ask themselves questions like, What would happen if I died? What would happen to my children?” she describes. This can be particularly dangerous for a person in a depressive episode with manic symptoms—they’re feeling helpless and miserable and they have the energy to act on that.

Marsh explains. “But at the same time, they feel sad and blue, they’re beating themselves up in their head, their self-worth is down.” Dr. Marsh also says a person experiencing a mixed episode commonly has thoughts of escaping the misery or even death. “While they may not have suicidal ideation, they may ask themselves questions like, What would happen if I died? What would happen to my children?” she describes. This can be particularly dangerous for a person in a depressive episode with manic symptoms—they’re feeling helpless and miserable and they have the energy to act on that.

Initially, you might think it sounds pretty impossible to experience depression and mania at the same time. “It’s very hard to conceptualize,” Dr. Marsh says. “But when you hear people express their own experience with it, it becomes a lot more clear.”

For an individual in a mixed episode, it can be one of the most distressing mood states to be in.

Gracie, 30, who was diagnosed with bipolar II in July 2018, tells SELF that her episodes are usually mixed. “One minute you’re full of energy, cleaning the house, feeling great about life, having some great ideas, getting your excitement back. Then the next, [you’re] about to cry and over-emotional for no reason, so lost in life you don’t know where you’re going [or] how you’re feeling, just that you’re not feeling good at all, feeling like you’ve not slept in weeks, irritated beyond belief by anything and everything,” she describes. “You want your significant other there to hug you and hold you and tell you it’s going to be ok but at the same time the idea of someone touching you makes your skin crawl.”

“One minute you’re full of energy, cleaning the house, feeling great about life, having some great ideas, getting your excitement back. Then the next, [you’re] about to cry and over-emotional for no reason, so lost in life you don’t know where you’re going [or] how you’re feeling, just that you’re not feeling good at all, feeling like you’ve not slept in weeks, irritated beyond belief by anything and everything,” she describes. “You want your significant other there to hug you and hold you and tell you it’s going to be ok but at the same time the idea of someone touching you makes your skin crawl.”

Most Popular

Joey, 41, who was diagnosed with bipolar II in 2006, also experiences episodes with mixed features. “Even when [I’m] hypomanic I’m still suffering, as the manic energy just drives the depression,” he tells SELF. “And I’m even more aware that my depression prevents me from doing most of the things my manic side screams at me to do. ”

”

He describes periods of more standard hypomania as a “little moment of clarity and relief, [like] when you are looking through binoculars and finally get them perfectly focused.”

For Emma, 20, mixed states are the most common. “I get extremely agitated. I'm very short with people. Even the smallest things can set off my anxiety. I'm quick to snap when I'm in a mixed state, because my mind and body are so confused. How can you be manic and depressed at the same time? [It feels like] your brain isn't equipped to handle that,” she tells SELF. (In April 2017, she was diagnosed with bipolar II.)

“So one minute I could feel totally fine. A few hours later, a text message could burst my entire day into flames and I can't see any of the good that happens,” Emma continues. “And then if I ask for help, it's like my mind doesn't want it, and I flip out on whoever I was asking.”

Treatment and management of bipolar disorder can vary greatly depending on the individual and their type of bipolar, as well as their episode patterns.

Whether or not you have bipolar I or II—and even if you’re not completely sure if your mood episodes present with mixed features—taking mood-stabilizing medications is the standard of care for bipolar disorder as a whole, Dr. Marsh says. “But there are a lot of exceptions and caveats—for instance, these drugs come with side effects,” she adds. “So there is a lot of discussion with the patient when prescribing treatment.”

Dr. Galynker also points out that it can take several months to find the right combination of medication, and the most effective medications for a person can change over time, too. “The illness is cyclical, and the same medication that may work at one point, let’s say in the more depressive phase of their cycle, may not work in the more manic phase of their cycle or in a period with mixed features,” he explains. “That’s why it’s very important to learn the very subtle behavioral changes a person exhibits at the early stages of their cycle.”

Therapy is also often helpful for this reason. “One of the ways that therapy has been found to be beneficial for people with bipolar disorder is that psychoeducation aspect—teaching people what their first symptoms of a mood elevation are, for instance, so they can catch them as quickly as possible when they present and implement the necessary interventions,” Dr. Marsh says.

“One of the ways that therapy has been found to be beneficial for people with bipolar disorder is that psychoeducation aspect—teaching people what their first symptoms of a mood elevation are, for instance, so they can catch them as quickly as possible when they present and implement the necessary interventions,” Dr. Marsh says.

Related:

- 21 Symptoms of Bipolar Disorder That Might Surprise You

- This Is What It's Actually Like to Live With Bipolar Disorder

- This Is What It's Really Like to Experience Psychosis

Jacqueline has been covering health and wellness since her college years at the Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University. She joined Team SELF in March 2018, and her writing/editing under the Health vertical primarily focuses on health conditions, mental health, and sexual and reproductive health. Her goal is to... Read more

SELF does not provide medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. Any information published on this website or by this brand is not intended as a substitute for medical advice, and you should not take any action before consulting with a healthcare professional.

Topicsbipolar disordermental healthmental illnessdepressionfeature

More from SelfEvolution of the concept of mixed states in the clinic of bipolar affective disorder

Mixed affective states are a controversial area of psychopathology. Along with mania and depression, they act as an independent phase of manic-depressive disorder [47], forming a family of separate forms of affective syndromes. Characterized by the introduction of depressive features into mania/hypomania or, conversely, manic into depression, mixed states are often not recognized by clinicians due to the polymorphism of symptoms and the lack of adequate diagnostic criteria.

The history of the concept of mixed states had four stages: the stage of creating the Kraepelinian concept of mixed states, which generalized all earlier indications of their existence; relative oblivion of the concept of mixed states; introduction into practice of their criteria within the framework of modern classifications of mental disorders; scientific search for new diagnostic criteria. For a deeper understanding of the essence of mixed states, one should consider each of them in more detail, prefixing them with a description of the stage of prototypes of mixed states.

For a deeper understanding of the essence of mixed states, one should consider each of them in more detail, prefixing them with a description of the stage of prototypes of mixed states.

Mixed states prototype stage. As pointed out by A. Koukopoulos and A. Koukopoulos [54], the first mentions of conditions that could essentially be called mixed are found in Lorry, Boissier de Sauvages and Cullen in descriptions of individual variants of melancholia ( melancholia moria, melancholia enthusiastica and etc.).

In the classification of mental disorders proposed by J. Heinroth [51], states of exaltation and excitation (hyperthymia), depressed states (asthenia), mixed states of excitation and weakness (hypoasthenia) were distinguished. The last diagnostic category included "mixed emotional disorders" ( animi morbi complicati ), "mixed mental disorders" ( morbi mentis mixti ) and "mixed impulse disorders" ( morbi voluntatis mixti, athymia ). The first two groups correspond to modern definitions of mixed affective and schizoaffective disorders. The French psychiatrist J. Guislain [49] classified “grumpy depression”, “grumpy exaltation”, “depression with exaltation and recklessness”, and “depression with anxiety” as mixed states, while noting the long duration of episodes characteristic of the first type and an unfavorable prognosis. . In his opinion, "gloomy insanity precedes frenzy", and the transition from one state to another can be accomplished through numerous steps, representing a "mixture of mental disorders" in various combinations. Similar descriptions can be found in J. Baillarger [25]. F. Richarz [72] used the term " melancholia agitans ". W. Griesinger [48] noted that depressive ideas and ideas of grandeur "do not necessarily exclude" each other, but can be observed simultaneously during the transition from one state to another, representing a "conglomerate of manic and depressive symptoms." The same opinion was shared by J.

The first two groups correspond to modern definitions of mixed affective and schizoaffective disorders. The French psychiatrist J. Guislain [49] classified “grumpy depression”, “grumpy exaltation”, “depression with exaltation and recklessness”, and “depression with anxiety” as mixed states, while noting the long duration of episodes characteristic of the first type and an unfavorable prognosis. . In his opinion, "gloomy insanity precedes frenzy", and the transition from one state to another can be accomplished through numerous steps, representing a "mixture of mental disorders" in various combinations. Similar descriptions can be found in J. Baillarger [25]. F. Richarz [72] used the term " melancholia agitans ". W. Griesinger [48] noted that depressive ideas and ideas of grandeur "do not necessarily exclude" each other, but can be observed simultaneously during the transition from one state to another, representing a "conglomerate of manic and depressive symptoms." The same opinion was shared by J. Falret [42], describing the period of “transition from excitation to depression” with the onset of a hard-to-characterize state formed by weakened excitation and beginning depression. Studying circular psychosis, R. Kraft-Ebing [57] singled out the phase of “indefinite symptoms, when excitement follows depression and vice versa”: in the transitional period, these states “merge” and one can observe the phenomenon when “temporary symptoms” appear in a depressive or manic picture. opposite state." In the group of "combined" psychoses, C. Wernicke [86] described "agitated melancholia" with characteristic features: intense anxiety, speech pressure and a jump in ideas. According to him, "agitated melancholy" combined elements of depression and melancholy.

Falret [42], describing the period of “transition from excitation to depression” with the onset of a hard-to-characterize state formed by weakened excitation and beginning depression. Studying circular psychosis, R. Kraft-Ebing [57] singled out the phase of “indefinite symptoms, when excitement follows depression and vice versa”: in the transitional period, these states “merge” and one can observe the phenomenon when “temporary symptoms” appear in a depressive or manic picture. opposite state." In the group of "combined" psychoses, C. Wernicke [86] described "agitated melancholia" with characteristic features: intense anxiety, speech pressure and a jump in ideas. According to him, "agitated melancholy" combined elements of depression and melancholy.

Thus, already in the 19th century, most well-known psychiatrists noted the existence of mixed states, denoting in their first prototypical descriptions fundamentally different positions, considering these states as an independent form or as a stage of transition between opposite affective phases.

The period of conceptualization of mixed states. By the beginning of the 20th century, numerous indications of the existence of mixed states needed to be generalized and were conceptualized by E. Kraepelin and his student W. Weygandt [87]. The latter, working under the guidance of E. Kraepelin in the psychiatric clinic of the University of Hedelberg, drew attention to the frequency of the simultaneous appearance of symptoms of different poles of manic-depressive psychosis (in 20% of the “circular” patients he observed). In his first monograph on mixed states in psychiatric literature - "On mixed states in manic-depressive insanity" ("Uber die Mischzustande des Manisch-depressiven Irreseins") - he outlined the fundamental approaches to their diagnosis - a different combination of opposite manic and depressive symptoms from triads: elated mood, psychomotor agitation and a jump in ideas, on the one hand, and low mood, psychomotor and ideator retardation, on the other. According to the author, instability of mood, motility and thinking is a characteristic feature of manic-depressive (circular) psychosis. He also noted that in some cases, mixed symptoms determine the clinical picture of the entire episode, contributing to a more protracted course (weeks, months, and even years) than in pure manic or depressive states. W. Weygandt believed that with various combinations of symptoms of the manic and depressive triad, at least six variants of mixed states can occur for a short time. Avoiding speculativeness, he attached practical importance to only three of their types, which are more common in clinical practice and have the longest duration - "manic stupor", "agitated depression" and "unproductive mania".

According to the author, instability of mood, motility and thinking is a characteristic feature of manic-depressive (circular) psychosis. He also noted that in some cases, mixed symptoms determine the clinical picture of the entire episode, contributing to a more protracted course (weeks, months, and even years) than in pure manic or depressive states. W. Weygandt believed that with various combinations of symptoms of the manic and depressive triad, at least six variants of mixed states can occur for a short time. Avoiding speculativeness, he attached practical importance to only three of their types, which are more common in clinical practice and have the longest duration - "manic stupor", "agitated depression" and "unproductive mania".

According to P. Salvatore [75], the works of W. Weygandt were a powerful impetus to the creation of Kraepelin's concept of manic-depressive psychosis, which was finally published in the 8th edition of his manual [55]. In this work, E. Kraepelin developed the concept of mixed states (Mischzustande) with a circular form of periodic insanity, pointing to the “internal relationship of seemingly opposite states”, in which there is a multidirectionality of the three components of an affective state - thinking, motor activity and mood itself. Singling out six mixed states (see table) , he believed that depressive or anxious mania (depressive oder ängsliche Manie), excited depression (erregte Depression), mania with scarcity of thoughts (ideenarme Manie) are based on three fundamental symptoms of mania (high euphoric mood, jump ideas, hyperactivity), while manic stupor (manischer Stupor), depression with a flight of thoughts (ideenfluchtige Depression), inhibited mania (gehemmte Manie) - on the fundamental symptomatology of depression ("ideational weakness", "depressed mood", "decreased motivation "). Analyzing the stereotype of the development of mixed states, E. Kraepelin singled out the transient form as a stage of transition from depression to mania or vice versa and an independent form characterized by a tendency to a protracted course.

Singling out six mixed states (see table) , he believed that depressive or anxious mania (depressive oder ängsliche Manie), excited depression (erregte Depression), mania with scarcity of thoughts (ideenarme Manie) are based on three fundamental symptoms of mania (high euphoric mood, jump ideas, hyperactivity), while manic stupor (manischer Stupor), depression with a flight of thoughts (ideenfluchtige Depression), inhibited mania (gehemmte Manie) - on the fundamental symptomatology of depression ("ideational weakness", "depressed mood", "decreased motivation "). Analyzing the stereotype of the development of mixed states, E. Kraepelin singled out the transient form as a stage of transition from depression to mania or vice versa and an independent form characterized by a tendency to a protracted course.

E. Kraepelin's concept had many supporters.

E. Bleuler [36] emphasized the importance of "such a quality of manic-depressive psychosis as confusion", reflecting, in his opinion, the possibility of a diverse combination of symptoms. K. Leonhard [59] believed that the allocation of mixed states indicates the potential properties of manic-depressive psychosis "to involve the characteristics of the opposite affective pole." However, other opinions were also expressed.

K. Leonhard [59] believed that the allocation of mixed states indicates the potential properties of manic-depressive psychosis "to involve the characteristics of the opposite affective pole." However, other opinions were also expressed.

In particular, K. Jaspers [52] and K. Schneider [77], questioning the independent significance of mixed states, considered it unlawful to “break” manic-depressive disorders into affective, intellectual and cognitive components. In their opinion, mixed states are nothing more than a change from a manic state to a depressive state and vice versa.

In parallel with E. Kraepelin, other researchers also worked on the issue of mixed states. O. Rehm [71], using the term "mixed affect" and separating "speech" and "general motor skills" from the psychomotor component of the affective state, proposed a more complex typification of mixed states. A different classification principle was proposed by E. Stransky [81], who divided mixed states depending on the nature of the predominant affect (manic and depressive types of mixed states), as well as taking into account the mechanisms of their formation (simultaneous and successive variants). At the same time, simultaneous mixed states were characterized by the simultaneous coexistence of individual signs of an affect of different polarity, and successive ones were characterized by a successive change of individual components of different polarity in the structure of one phase.

At the same time, simultaneous mixed states were characterized by the simultaneous coexistence of individual signs of an affect of different polarity, and successive ones were characterized by a successive change of individual components of different polarity in the structure of one phase.

In domestic psychiatry of the beginning of the 20th century, works devoted to mixed states are relatively few in number. Mixed states were mentioned by P.B. Gannushkin, S.A. Sukhanov [3], V.P. Serbian [11, 12], A.N. Bernstein [1], Yu.V. Kannabih [6], E.S. Lokshin [8]. A particularly detailed study of mixed states was carried out by S.A. Sukhanov [13]. The author noted that mixed states appear at more distant stages of the disease as a "further evolution of manic-depressive psychosis" after the stage of alternation of typical manic and depressive phases.

The middle of the 20th century became a period of relative oblivion for mixed fortunes . Nevertheless, in a few publications of foreign psychiatrists (K. Kleist [56], G. Ewald [41], J. Rouart [74], M. Fischetti [44], J. Lange [58], J. Campbell [37] ) you can find indications of the importance of identifying mixed conditions, which, combining the symptoms of different affective poles, thereby reflect the commonality of a single cyclothymic process with the possibility of developing any of these forms in a particular patient.

Kleist [56], G. Ewald [41], J. Rouart [74], M. Fischetti [44], J. Lange [58], J. Campbell [37] ) you can find indications of the importance of identifying mixed conditions, which, combining the symptoms of different affective poles, thereby reflect the commonality of a single cyclothymic process with the possibility of developing any of these forms in a particular patient.

During this period, in domestic psychiatry, with some delay, active disputes continued about the validity of E. Kraepelin's ideas in relation to these conditions. One of the followers of the Kraepelinian model of mixed states in the Russian psychiatric school, V.A. Gilyarovsky [4] pointed out that "in addition to pure states of excitation or depression, mixed patterns are observed, characterized by a longer course and an unfavorable prognosis." The author believed that out of nine theoretically possible combinations of excitation and oppression in three areas of mental activity (emotional, intellectual and volitional), the real value among mixed states with an emphasis on the manic component is angry mania, with an emphasis on the depressive - agitated melancholia. Opposite views were expressed by V.M. Bekhterev [2], pointing out the inconclusive evidence for the existence of mixed or transient manic-melancholic states.

Opposite views were expressed by V.M. Bekhterev [2], pointing out the inconclusive evidence for the existence of mixed or transient manic-melancholic states.

Stage of introduction of criteria within the framework of modern classifications of mental disorders. Subsequently, in the wake of the consequences of the psychopharmacological "revolution" in the works of a number of researchers [22, 68, 88], a revival of interest in mixed states began, which was characterized by two features: on the one hand, confirmation of the previously formulated provisions regarding this concept, on the other hand, dissatisfaction with the accumulated by that time, ideas about the structure of mixed states as a simple combination of polar symptoms. Deepening knowledge about the dependence of the psychopathological structure of mixed affective syndromes on syndromokinesis, S. Mentzos [66] proposed to distinguish between stable and unstable mixed states. The clinical picture of stable mixed states is represented by a synchronous combination of symptoms of depression and mania and is characterized by the replacement of one or more elements of mania (hypomania) by signs of depression and vice versa (for example, agitation in depression or lethargy in a manic state). So, during the period of the greatest severity of affective disorders, anxiety can be accompanied by motor restlessness (patients are tense, cannot find a place for themselves, can neither sit nor lie down) and speech excitation with groans, lamentations, anxious verbigeration - repeated monotonous repetition of monotonous short phrases and expressions ( agitated depression). Unstable mixed states are formed during the rapid change of polar affective phases within the "short cycle". At the same time, depressive and manic manifestations overlap in various, sometimes very chaotic combinations. Their psychopathological structure, in contrast to "pure" depression and hypomania, is determined by a large polymorphism; the variety of manifestations is associated both with the formation of general symptoms (irritability, anxiety, ideomotor restlessness, internal tension, impaired concentration, insomnia), and the addition of psychopathological disorders of other registers (obsessive-compulsive, panic attacks, depersonalization).

So, during the period of the greatest severity of affective disorders, anxiety can be accompanied by motor restlessness (patients are tense, cannot find a place for themselves, can neither sit nor lie down) and speech excitation with groans, lamentations, anxious verbigeration - repeated monotonous repetition of monotonous short phrases and expressions ( agitated depression). Unstable mixed states are formed during the rapid change of polar affective phases within the "short cycle". At the same time, depressive and manic manifestations overlap in various, sometimes very chaotic combinations. Their psychopathological structure, in contrast to "pure" depression and hypomania, is determined by a large polymorphism; the variety of manifestations is associated both with the formation of general symptoms (irritability, anxiety, ideomotor restlessness, internal tension, impaired concentration, insomnia), and the addition of psychopathological disorders of other registers (obsessive-compulsive, panic attacks, depersonalization). Such unstable mixed states were described in the domestic literature [7] under the term “atypical”, often associated with the consequences of the use of antidepressants.

Such unstable mixed states were described in the domestic literature [7] under the term “atypical”, often associated with the consequences of the use of antidepressants.

T.F. put another meaning into the term "atypical mixed states". Papadopoulos [10]. Noting the relative clarity in terms of the psychopathological structure of the periods of "mixed affect" during the transition from one phase to another, he singled out true mixed states that require special analysis within the atypical phases of not only circular, but also affective psychoses in a broader sense. The author suggested considering the "atypia" of individual phases of manic-depressive psychosis, taking into account the premorbid personality and age of patients.

Yu.L. Nuller and I.N. Mikhalenko [9] to the assumption that the typology of mixed states proposed by E. Kraepelin is limited.

Uniformity in the diagnosis of mixed states began with the creation in the 80s of unified criteria for assessing mental disorders - Research Diagnostic Criteria (RDC) [78, 79] and the DSM-III-R classification [20].

In the RDC, two variants of mixed states were distinguished: when depressive and manic syndromes were presented simultaneously during one episode and when they followed one after the other without interruption. RDC criteria were partly incorporated into the DSM-III-R classification, which provided a rather vague description of the category "bipolar disorder - mixed". Its diagnosis required the presence of a complete symptomatological picture of a manic and major depressive episode, coexisting simultaneously or rapidly replacing each other every few days. At the same time, depressive symptoms had to be sufficiently pronounced and persist at least throughout the day. The advent of the DSM-III-R did not add clarity to the diagnosis of mixed conditions. As noted by G. Perugi et al. [69], such criteria ruled out the possibility of the presence of individual competing symptoms of opposite polarity, which led to an underdiagnosis of mixed conditions.

A more specific definition of a "mixed episode" was given in DSM-IV [21]. Its diagnosis required meeting the criteria for both manic and major depressive episodes almost every day for at least 1 week. Thus, the category of mixed episodes did not include unstable forms characterized by a successive change of manic and depressive symptoms, which were classified under the heading specifier “rapid cyclicity”.

Its diagnosis required meeting the criteria for both manic and major depressive episodes almost every day for at least 1 week. Thus, the category of mixed episodes did not include unstable forms characterized by a successive change of manic and depressive symptoms, which were classified under the heading specifier “rapid cyclicity”.

In this regard, the criteria of the modern American classification correspond only to stable forms of mixed conditions.

The DSM-IV criteria for mixed states have also been criticized as narrow, restrictive, and inconsistent with clinical reality [17, 26, 65, 69, 83], primarily due to the high prevalence of non-syndromic symptoms of the opposite polarity. Thus, F. Benazzi [27] cites data that the formation of complete syndromic hypomania in patients with a major depressive episode was observed in 2.8% of cases, while in the presence of individual hypomanic symptoms - in 28.5%.

In accordance with the results of the study by F. Benazzi, H. Akiskal [29], 48.7% of patients with major depression as part of bipolar affective disorder type II (BAD II) had three or more competing hypomanic symptoms coexisting.

Benazzi, H. Akiskal [29], 48.7% of patients with major depression as part of bipolar affective disorder type II (BAD II) had three or more competing hypomanic symptoms coexisting.

The ICD-10 [89] defines a mixed episode as “an affective episode lasting at least 2 weeks and characterized by either a mixture or a rapid alternation (often within hours) of hypomanic, manic and depressive symptoms.” Both sets of symptoms must be "significantly pronounced during most of the current episode of the disease." It further clarifies that "depressive mood is often accompanied for days or weeks by hyperactivity and the pressure of speech, and a manic state with grandiosity - agitation and loss of energy and libido." Thus, the ICD-10, compared to DSM-IV, offers less restrictive criteria for mixed states, requiring only "pronounced" manic or hypomanic and depressive symptoms, but not full syndromes, and explicitly embraces ultradian cyclicity. Moreover, unlike the DSM-IV, the description of the ICD-10 recognizes the existence of mixed depression and mania.

Search for new diagnostic criteria. In recent decades, the concept of mixed states has received increasing attention in light of the increasing interest in the problem of bipolar disorders (especially type II). Research is directed, on the one hand, to the search for new, more realistic diagnostic criteria, and, on the other hand, to clarify the phenomenology of mixed states.

During the search for new diagnostic criteria for a mixed state, evidence has been accumulated for the sufficiency of verification of several competing contrapolar symptoms for the diagnosis of subsyndromal depression in the structure of syndromic mania [63, 69] or subsyndromal mania in the structure of syndromic depression [15, 53, 69]. At the same time, the discussions concerned the question of the number of these contrapolar symptoms that are optimally sufficient for the diagnosis of a mixed state: S. McElroy et al. [63] proposed in this vein to consider more than three depressive symptoms in the structure of mania, H. Akiskal et al. [17] - more than two, and A. Swann et al. [83] - more than one, which predetermined the expansion of the concept of mixed states.

Akiskal et al. [17] - more than two, and A. Swann et al. [83] - more than one, which predetermined the expansion of the concept of mixed states.

Alternative criteria of mixed states proposed at that time (three of the best known - Cincinnati [63], Vienna [32-34], Pisan [69]) were not sufficiently valid and did not provide the same diagnostic accuracy when compared with each other and with DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 diagnostic criteria [50]. Thus, mixed mania, detected by clinical assessment in 23.2% of patients with BAD I, could be diagnosed using Cincinnati criteria in 16.7% of cases, and DSM-IV-TR and ICD-10 criteria - only in 12.9 and 9% of cases, respectively [85].

H. Akiskal [14-16, 18] expanded the interpretation of mixed states by including signs that appear as part of the manifestation of an affective episode based on temperament of the opposite polarity (hyperthymic, depressive, cyclothymic, irritable and anxious).

The concept of the bipolar spectrum, which has numerous supporters, also has a certain influence on the formation of new views on mixed states. S. McElroy [65], considering mixed bipolar episodes in relation to their belonging to the bipolar spectrum, indicates the possibility of countless variants of combinations of different severity of manic and depressive symptoms. In its extreme form, the dimensional approach was presented by A. Swann et al. [82], who proposed to consider mixed states in the form of a continuum of various combinations of manic and depressive manifestations, including not only Kraepelinian subtypes, but also many of their transitional forms.

S. McElroy [65], considering mixed bipolar episodes in relation to their belonging to the bipolar spectrum, indicates the possibility of countless variants of combinations of different severity of manic and depressive symptoms. In its extreme form, the dimensional approach was presented by A. Swann et al. [82], who proposed to consider mixed states in the form of a continuum of various combinations of manic and depressive manifestations, including not only Kraepelinian subtypes, but also many of their transitional forms.

Recent research is moving away from categorical positions towards a dimensional study of the individual symptoms of mania and depression involved in the formation of mixed states in order to identify underlying symptomatic clusters that determine response to therapy and prognosis.

The need to develop a modern phenomenology of mixed states forced researchers to turn again to the Kraepelin typology when describing the most common variants of mixed states - dysphoric mania [49, 63, 70] and agitated depression [15, 30, 31, 53, 61]. F. Cassidy [38] and T. Sato [76] confirm the validity of the subtype of mania with severe symptoms of dysphoria, corresponding to Kraepelin's "anxiety-depressive mania". N. Akiskal and F. Benazzi [19], considering mixed depression as a combination of a complete depressive syndrome and three competing hypomanic symptoms, also indicate the existence of two subtypes corresponding to Kraepelin's "depression with a leap of ideas" and "agitated depression".

F. Cassidy [38] and T. Sato [76] confirm the validity of the subtype of mania with severe symptoms of dysphoria, corresponding to Kraepelin's "anxiety-depressive mania". N. Akiskal and F. Benazzi [19], considering mixed depression as a combination of a complete depressive syndrome and three competing hypomanic symptoms, also indicate the existence of two subtypes corresponding to Kraepelin's "depression with a leap of ideas" and "agitated depression".

To the most common manic symptoms in the structure of a depressive episode in BAD I and II J. Goldberg et al. [46] refer to distractibility, ideational acceleration, agitation, and C. Pae et al. [67] - jump of ideas, increased distractibility, irritability, of which the latter, according to the authors, seems to be the main predictor of response to antipsychotic therapy. Symptoms of anxiety and dysphoria, which are related to the nuclear symptoms of mixed mania [35, 40], are attracting more and more attention from researchers. At the same time, dysphoria is considered as a special component of the affective syndrome, which correlates with irritability, increased sensitivity to external physical influences, impulsivity, and a sense of internal tension. F. Cassidy [40], based on the results of a factor analysis of a large sample of bipolar patients with mania, indicates that anxiety is an extremely common symptom of states corresponding to Kraepelin's "anxiety-depressive mania", and proposes to include it in the criteria for mixed states. A comparable level of anxiety in a comparative study of agitated depression and mixed mania by A. Swann [82] also confirms its inherent belonging to a mixed bipolar phenomenology.

At the same time, dysphoria is considered as a special component of the affective syndrome, which correlates with irritability, increased sensitivity to external physical influences, impulsivity, and a sense of internal tension. F. Cassidy [40], based on the results of a factor analysis of a large sample of bipolar patients with mania, indicates that anxiety is an extremely common symptom of states corresponding to Kraepelin's "anxiety-depressive mania", and proposes to include it in the criteria for mixed states. A comparable level of anxiety in a comparative study of agitated depression and mixed mania by A. Swann [82] also confirms its inherent belonging to a mixed bipolar phenomenology.

Factor analysis of individual symptoms of a mixed state showed that the predominance of manic or depressive symptoms in them already leads to heterogeneity in terms of subsequent dynamics, response to treatment and prognosis. Thus, according to the observations of J. Azorin [24], mixed states with a predominance of depressive symptoms are characterized by a lower probability of relapses compared with mixed states with a predominance of manic symptoms; the former often turn into depression, the latter into mania.

Further perspectives. The proposed DSM-V classification criteria published to date demonstrate the intention of its developers to bring the controversy of recent years to a common denominator and continue the clearly emerging trend to expand the criteria for mixed conditions by reducing the number of symptoms of the opposite affect, sufficient for its diagnosis. Presumably, the DSM-V will be different from the DSM-IV: the category "mixed episode" will disappear altogether and instead the specifier "with mixed features" will be introduced, applicable to the diagnosis of both depression and mania in case at least three symptoms are present. opposite polarity. The latter comes from the already mentioned data confirming that distinct differences between "pure" and "mixed" mania/hypomania or major depression appear when the number of contrapolar symptoms reaches at least three (cited in [84]). The list of counterpolar symptoms will be excluded from those occurring in both mania and depression: psychomotor agitation, irritability, insomnia (to be distinguished from a decrease in the need for sleep), increased distractibility and loss of appetite.

Thus, the proposed definition of mania/hypomania "with features of confusion" in the DSM-V requires that the criteria for a manic or hypomanic episode be fully met and that at least three of the following symptoms be present almost every day during the episode: severe dysphoria or depressed mood, decreased interest or pleasure in almost all activities, psychomotor retardation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of inadequacy and excessive or unjustified guilt, recurring thoughts of death or a suicide attempt or suicide planning. The proposed definition of a major depressive episode "with features of confusion" requires meeting the criteria for a major depressive episode and the presence of at least three of the following symptoms observed almost every day during the episode: high or expansive mood, high self-esteem, or grandiosity, unusual talkativeness, or verbal rush, racing of ideas, or subjective feeling of speeding up thoughts, increased energy, purposeful activity, involvement in activities with a high risk of unpleasant consequences, reduced need for sleep.

In addition, the use of the specifier “with mixed traits” for manic, hypomanic and depressive episodes would mean that mixed states are included not only in the circle of BAD I and II, but also in the depressive episode. Thus, the application of this criterion will mean that the diagnosis of major depression "with features of confusion" will not indicate the phenomena of bipolarity. Thus, a patient with three typical manic competing symptoms (eg, high spirits, high self-esteem or grandiosity, excessive involvement in activities with a high risk of adverse consequences) in the structure of a major depressive episode can be classified as unipolar.

The definition of mania/hypomania “with features of confusion” is consistent with available research data and operational criteria reported earlier in the literature [65] and is not likely to change. On the contrary, the definition of major depression "with features of mixed depression" is likely to be debatable, since it includes typical manic symptoms, such as elation and grandiosity, which are rare in patients with mixed depressions, while among the excluded symptoms are those often observed in them. - irritability, psychomotor agitation and distractibility [46, 60]. It is important to note that the putative criteria for the "mixed-feature" specifier in DSM-V, like the criteria for "mixed episode" in DSM-IV, do not include ultradian cyclicity, which may be the subject of further research.

- irritability, psychomotor agitation and distractibility [46, 60]. It is important to note that the putative criteria for the "mixed-feature" specifier in DSM-V, like the criteria for "mixed episode" in DSM-IV, do not include ultradian cyclicity, which may be the subject of further research.

As for the forthcoming edition of ICD-11, the same difficulties may arise before its creators. If the data on insufficient effectiveness and an increased risk of affect reversal against the background of the use of antidepressants in mixed depression are not generally recognized as sufficiently convincing [43], then all researchers emphasize a higher suicidal risk among patients with mixed states [45, 73, 80]. Moreover, mixed states belong to those clarifying diagnostic categories that significantly affect the choice of therapeutic tactics, requiring the use of specific approaches.

From the point of view of the practical orientation of modern classifications, all this justifies the need to use new criteria for the diagnosis of mixed conditions.

Thus, the definition of mixed states over more than 100 years of history has undergone a number of changes due to the search for optimal approaches to their diagnosis, and at the present stage is firmly included in the unified classifications of mental disorders. The ideas of E. Kraepelin, without losing their relevance, are reflected in all the concepts proposed by researchers, both categorical and dimensional in nature. The knowledge accumulated to date about mixed states indisputably proves the practical significance of this psychopathological unit not only in a prognostic sense, but also in the aspect of choosing a rational pharmacotherapy. The works of recent decades have formed a consensus on the need to expand the diagnostic criteria for mixed conditions, substantiating their inconsistency with clinical reality, which is reflected in the DSM-V project.

Guidelines for the Treatment of Mixed Conditions in Bipolar Disorder (WFSBP)

We present to your attention an overview translation of the first in the history of psychiatry clinical guidelines for the treatment of mixed conditions in bipolar affective disorder of the World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry, prepared jointly by the scientific Internet portal "Psychiatry & Neurosciences" and Clinics of Psychiatry and Addiction Dr. SAN.

SAN.

Mixed fortunes have attracted close attention of specialists only recently. Interest is largely due to their high prevalence and poor prognosis. 70% of patients with manic symptoms also have depressive symptoms. Observations of such mixed states support the idea that bipolar disorder is by no means a "madness in two forms", a disease in which two polar states - manic and depressive - are clearly separated.

It's time to create a guideline dedicated exclusively to mixed disorders. Current recommendations include extrapolations from studies that have examined cases of pure mania. Based on these extrapolations, recommendations were made for mixed conditions. However, mixed depression (depression with hypo/manic symptoms) was rarely taken into account.

The presence of depressive symptoms in the manic phase was noted as early as the beginning of the 19th century. by German scientists. In the middle of the XIX century. transitional states observed at the end of depression and the onset of mania have been described. In transitional states, the symptoms of mania and depression intermingle.

In transitional states, the symptoms of mania and depression intermingle.

The first systematic description of mixed states was made by Kraepelin and Weingandt in 1899. Their description proceeds from the fact that between pure mania and pure depression there are subtypes in which features of depression and mania are mixed in various combinations.

The main problem in the treatment of mixed conditions is that there is still no common definition of what it is. The DSM-IV, ICD-10, and DSM-V diagnostic criteria are summarized in Table 1. This guideline, which is based on the DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, refers to the following situations:

- immediate treatment of a manic episode with three or more depressive symptoms, including anxiety, irritability and agitation

- prompt treatment of a bipolar depressive episode with three or more hypomanic or manic symptoms

- continuation of treatment and prevention of recurrence of a mixed episode

- prevention of a mixed episode after a manic or depressive episode

Due to the lack of a common understanding of mixed states, data on their prevalence vary greatly. Mixed states are noted to become more frequent as bipolar disorder progresses, especially in women. The sex ratio, according to some sources, looks like 60:40 in favor of women. Manic patients with mixed states are more likely to be hospitalized and spend more time there. It is also noted that patients with mixed states are more likely to abuse psychoactive substances.

Mixed states are noted to become more frequent as bipolar disorder progresses, especially in women. The sex ratio, according to some sources, looks like 60:40 in favor of women. Manic patients with mixed states are more likely to be hospitalized and spend more time there. It is also noted that patients with mixed states are more likely to abuse psychoactive substances.

A - Strong evidence from controlled trials with psychotherapy superiority over “psychological placebo”) or one or more RCTs with positive results showing superiority or the same efficacy as the comparator, with three groups of participants and a placebo control or in a well-designed experiment (when there is a standard drug for comparison).

If there are studies with a negative result (studies that do not show superiority over placebo or show lower efficacy than the comparator drug), each of them must have at least two more studies with positive results or a meta-analysis of all available studies showing superiority over placebo and higher efficacy compared to the comparator drug. Research must meet established methodological standards.

B - Limited evidence from controlled trials

Category assigned if: one or more RCTs showing superiority over placebo (or in the case of psychotherapy, superiority over “psychological placebo”) or randomized controlled comparison with standard treatment without placebo control with a sample size sufficient for experiment or a priori designed subgroup analysis included in the study protocol, with one negative result (studies that do not show superiority over placebo or show lower efficacy in comparison comparator) must have at least one other positive result or meta-analysis of all available studies showing superiority over placebo and superior efficacy to the comparator.

C - Evidence from uncontrolled studies or clinical cases, expert opinion, post hoc analysis of RCTs ) or comparison with a reference drug in an insufficient sample size for a comparative experiment and no controlled studies with a negative result or clinical cases: one or more than one positive and no controlled trials with negative results or post hoc analysis of an RCT (not designed a priori as part of the study protocol) or expert opinion available

D – Inconsistent results

RCTs with positive results are inferior or approximately equal in number to RCTs with negative results.

E - Negative Evidence

Most RCTs or exploratory studies show no superiority over placebo (or in the case of psychotherapy, superiority over “psychological placebo”) or lower efficacy than the comparator drug.

F - No evidence

Levels of recommendation (RG):

1 - Category of evidence A and good risk/benefit ratio

2 - Category of evidence A and moderate risk/benefit ratio

3 -

Category of evidence C

5 - Category of evidence D

Additional evidence (FE)

++ - Several supporting additional evidence that does not meet the criteria, such as meta-analysis or positive studies to assign the category of evidence “A” or “B”

+ - Some supporting additional evidence, such as limited data from open studies

0 - Conflicting or no data open studies/Multiple refuting additional evidence, such as a negative meta-analysis or studies with a negative result that do not meet the criteria for an “A” or “B” category of evidence

Safety and tolerance (ST)

++-very good

+-good

0-the advantages and no data are equal or not data

(-)-there are problems/ there Serious problems

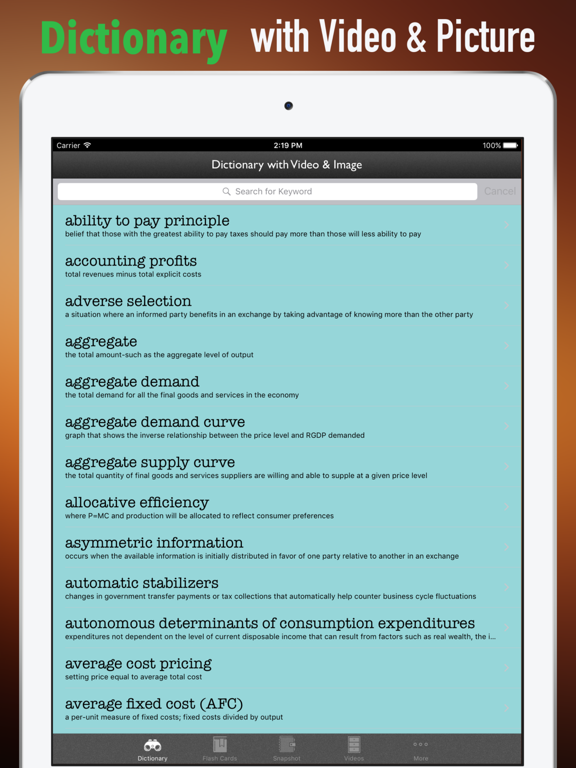

Table 2. CE and RG for immediate treatment of mixed conditions

CE and RG for immediate treatment of mixed conditions

MM: mixed manic; DM: mixed depressive; MS: manic symptoms; DS: depressive symptoms; M: mania; D: depression; Mx: mixed episode; MIE: first manic episode; DIE: first depressive episode; MxIE: first episode of mixed condition; CE: category of proof; FE: additional evidence; ST: safety and tolerability; RG: recommendation level.

| CE for acute episodes DM (monotherapy) | FE for treatment | ST for treatment | RG for immediate treatment of mixed conditions | |

| Azenapine | E for MS C for DS | F | + | 4 for MM (monotherapy, only for DS) |

| Antidepressants | F | F | – | not recommended |

| Aripiprazole | B for MS B for DS | F | 0 | 3 for MM (monotherapy) |

| Valproic acid | C for MS | F | + | 4 for MM (monotherapy) |

| Gabapentin | F | F | + | 4 for MM (combination therapy) |

| Ziprasidone | C for MS C for DS | F | + | 4 for MM (monotherapy) 3 for DM (combination therapy) |

| Carbamazepine | C for MS C for DS | C for DS | – | 4 for MM (monotherapy) 4 for DM (monotherapy, only for DS) |

| Cariprazine | C for MS F for DS | F | + | 4 for MM (monotherapy only for MS) |

| Quetiapine | E | F | 0 | 3 for MM (combined therapy, for DS) 4 for MM (combined therapy, for MS) |

| Clozapine | C for MS | F | – | 4 for MM (monotherapy, combination therapy, only for MS) |

| Lamotrigine | F | F | + | not recommended |

| Lithium | F | F | – | not recommended |

| Lurasidone | F | C | + | 4 for DM (monotherapy) |

| Oxcarbazepine | F | F | + | 4 for MM (in combination with lithium) |

| Olanzapine | A for MS C for DS | C | + | 2 for MM (monotherapy) 2 for MM (in combination with with valproic acid) 4 for DM (monotherapy) |

| Paliperidone | B for MS E for DS | F | 0 | 3 for MM (monotherapy) |

| Risperidone | C | F | 0 | 4 for MM (monotherapy) |

| Generic antipsychotics | C | F | 0 | 4 for MM (monotherapy) |

| Topiramate | F | F | 0 | 5 for MM (combination therapy) |

| ect | F | F | – | 4 for MM (combination therapy) 4 for DM (combination therapy) |

Table 3. CE and RG for maintenance therapy after an episode of a mixed state and for its prevention

CE and RG for maintenance therapy after an episode of a mixed state and for its prevention

MM: mixed manic; DM: mixed depressive; M: mania; D: depression; Mx: mixed episode; MIE: first manic episode; DIE: first depressive episode; MxIE: first episode of mixed condition; CE: category of proof; FE: additional evidence; ST: safety and tolerability; RG: recommendation level.

| CE to prevent relapse (monotherapy) | CE to prevent a mixed episode after a manic or depressive episode (monotherapy) | ST for long term treatment | RG for maintenance therapy | |

| Azenapine | F | F | + | not recommended |

| Antidepressants | F | F | 0 | not recommended |

| Aripiprazole | F | E (MIE) F (DIE) | + | 4 to prevent D after MxIE (combination therapy) |

| Valproic acid | E | B | – | 3 to prevent a mixed episode after an episode of undetermined type (monotherapy) or after a manic or mixed episode |

| Gabapentin | F | F | + | not recommended |

| Ziprasidone | C | F | + | 4 to prevent mania after MxIE (monotherapy) |

| Carbamazepine | F | E | – | not recommended |

| Cariprazine | F | F | + | not recommended |

| Quetiapine | B (for manic, depressive, any type) | E | – | 2 to prevent a new episode after MxIE (combination therapy) 3 to prevent a new episode after MxIE (monotherapy) |

| Clozapine | F | F | – | not recommended |

| Lamotrigine | F | E | + | not recommended |

| Lithium | B for all types B for Manic | D | – | 3 to prevent a new manic episode and any type of episode after MxIE (monotherapy) 5 to prevent a mixed episode after the first episode of any type |

| Lurasidone | F | F | + | not recommended |

| Oxcarbazepine | F | F | 0 | not recommended |

| Olanzapine | B | D | – | 3 to prevent a new episode after MxIE (monotherapy) |

| Paliperidone | F | F | 0 | not recommended |

| Risperidone | F | F | – | 4 to prevent a new episode after MxIE (combination therapy) |

| Generic antipsychotics | F | F | – | not recommended |

| Topiramate | F | F | 0 | not recommended |

| ect | F | F | – | 4 to prevent a new episode after MxIE (combination therapy) |

Several drugs are effective in treating patients with mixed conditions. But none of these drugs work equally well at all stages of treatment and in all subgroups of patients. There are still more questions than answers regarding the treatment of mixed conditions.

But none of these drugs work equally well at all stages of treatment and in all subgroups of patients. There are still more questions than answers regarding the treatment of mixed conditions.

Olanzapine, paliperidone and aripiprazole have been the best evidence for the immediate treatment of mixed mania. For bipolar depressive mixed state, only ziprasidone has been shown to be effective in combination therapy (recommendation grades 1-3). Level 4 recommendation categories are carbamazepine, lurasidone, olanzapine, and ECT.

Thus, for bipolar depressive mixed state, there are no drugs with convincing evidence. In addition, ziprasidone has only been studied in bipolar II disorder.

Quetiapine, lithium and olanzapine (as monotherapy and in combinations) are best suited to prevent a new episode of a mixed state.

Little is known about how to prevent a mixed episode after a primary manic, mixed, or depressive episode. But at least valproic acid, olanzapine and lithium show some effectiveness.