Help for ocd child

The Parents' Role in OCD Treatment

When you’re the parent of an anxious child, you assume that your role is to provide reassurance, comfort, and a sense of safety. Of course you want to support and protect a child who is distressed and, as much as possible, avert her suffering. But in fact, when it comes to a child with an anxiety disorder like obsessive compulsive disorder, trying to shield her from things that trigger her fears can be counterproductive for the child. By doing what comes naturally to a parent, you are inadvertently accommodating the disorder, and allowing it to take over your child’s life.

That’s why parents have a surprisingly important role in treating anxiety disorders in children. The gold standard in pediatric OCD treatment is a form of cognitive-behavioral therapy called exposure and response prevention. The therapy involves “exposing” the child to her anxieties in a gradual and systematic way, so she no longer fears and avoids those objects or situations; “response prevention” means she is not allowed to perform a ritual to manage fears.

Because parents become so involved in their children’s OCD, research has shown that including parents in treatment and assigning them as “co-therapists” improves effectiveness.

The fear hierarchy

In therapy the child, parents, and therapist create a “fear hierarchy” in which they collaboratively identify all of the feared situations, rate them on a scale of 0-10, and tackle them one at a time. For example, a child with fears about germs and getting sick would repeatedly confront “contaminated” situations and objects until her fear subsides and she can tolerate the activity. The child would start with a low-level anxiety item, such as touching clean towels, and build to more difficult items such as holding half-eaten food from the trash.

Response prevention involves preventing the child from performing the behavior that serves to decrease the anxiety. For example, a boy with a fear of germs would have to abstain from washing his hands after touching the doorknob, or the garbage. Through gradual exposure he learns that what he “fears” usually does not come true, so that new learning can take place. It also teaches him that he can tolerate uncomfortable feelings.

Through gradual exposure he learns that what he “fears” usually does not come true, so that new learning can take place. It also teaches him that he can tolerate uncomfortable feelings.

Much of the work in CBT involves practice outside of sessions, requiring parents to participate in the treatment. Children are assigned “homework” and asked to continue practicing facing their fears in a variety of settings. Since exposure and response prevention evokes anxiety and requires considerable follow-up, family involvement and support is essential.

For a child with a fear of contamination, the parents may encourage him to do the dishes, or to become a “human vacuum cleaner,” which is what clinicians call picking up small scraps of garbage from the carpet. A child with fears of vomiting might write a comic about “Vomit Man” in session with his therapist, and then practice reciting it aloud to his parents.

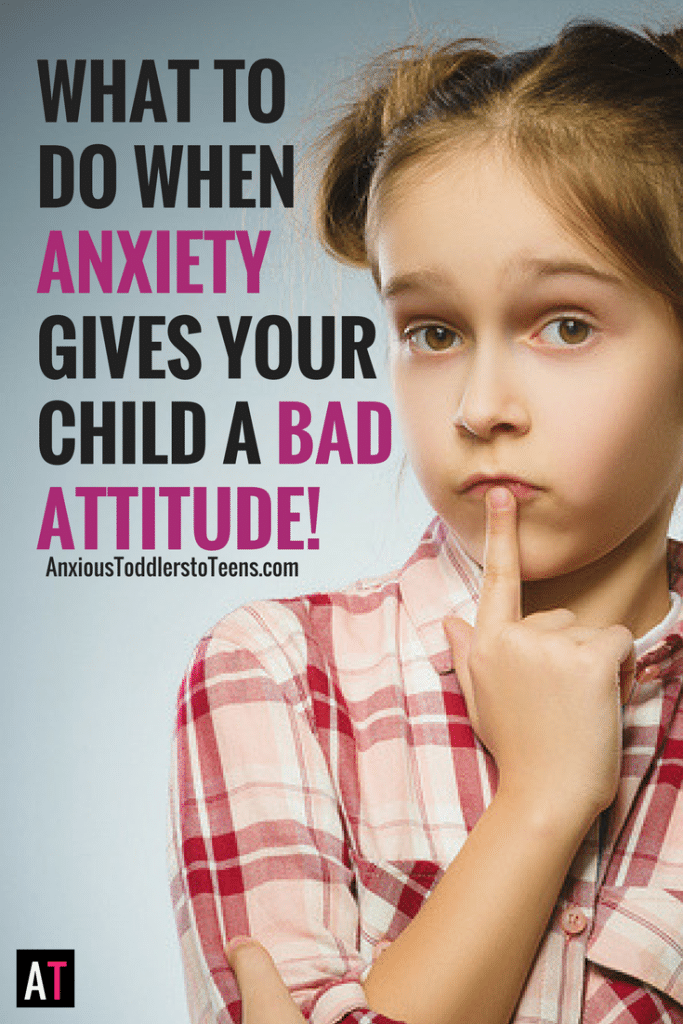

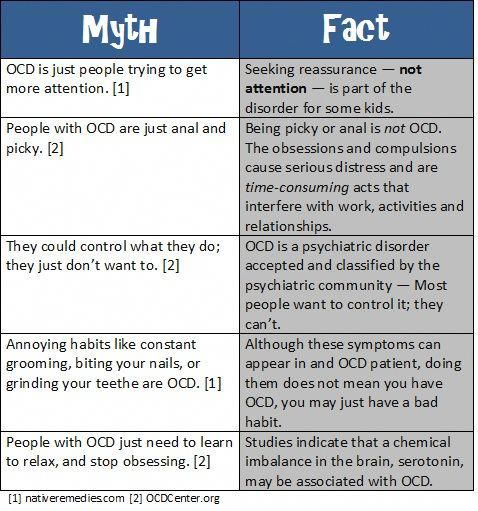

The problem with reassurance

But parents have a bigger role than backup when it comes to practicing exposures at home. Since OCD can be a crippling disorder for children, relatives often become excessively involved in a child’s symptoms in order to help the child function. For instance, many children with OCD, as well as other anxiety disorders, seek constant reassurance from family members. Reassurance-seeking is used by children to manage fears, and many parents provide it, even though it’s excessive, in order to make their child feel better in the moment.

Since OCD can be a crippling disorder for children, relatives often become excessively involved in a child’s symptoms in order to help the child function. For instance, many children with OCD, as well as other anxiety disorders, seek constant reassurance from family members. Reassurance-seeking is used by children to manage fears, and many parents provide it, even though it’s excessive, in order to make their child feel better in the moment.

Reassurance-seeking is one of the many forms of “family accommodation.” This phenomenon refers to the manner in which family members participate in the rituals the child uses to manage his anxiety, as well as how they modify personal and family routines in order to accommodate him.

Many children suffering from OCD are unable to tolerate uncertainty, and they ask their parents to provide them with definitive answers. For example, it is not uncommon to hear an anxious child ask their parent “Am I going to get sick from eating this?” or “Is everything going to be okay?” although the answer may have already been provided several times.

Parents can easily become frustrated because they feel like no matter how many times their child’s questions are answered, they are never satisfied. Answering their child’s questions becomes an endless cycle, and the child never learns that he can indeed tolerate the uncertainty.

Accommodating fears

There are many other forms of accommodation. Families may stop taking vacations, going out to restaurants, or even change the way they speak in order to avoid anxiety-provoking situations for their child. They may avoid particular names, numbers, colors, and sounds that trigger anxiety.

“OCD can be very overwhelming to families and can really interfere with how families can normally function,” says Jerry Bubrick, PhD, a clinical psychologist at the Child Mind Institute who specializes in anxiety and OCD. “The family decisions are made to accommodate the anxiety, rather than the best interests of the family.”

To the family of a patient we’ll call John, a 12-year old boy who was treated at the Child Mind Institute for OCD, this is all too familiar. John had fears about contamination and gaining weight and thus he avoided any food that was considered “unhealthy,” took up to seven showers a day, and didn’t play with his siblings or hug his parents in the belief that they were contaminated.

John had fears about contamination and gaining weight and thus he avoided any food that was considered “unhealthy,” took up to seven showers a day, and didn’t play with his siblings or hug his parents in the belief that they were contaminated.

“We didn’t go out to a restaurant for months,” said John’s mother. “He didn’t have any friends come over. We didn’t have any of our friends come over. Our house was a safe place.”

But accommodating John’s anxiety didn’t stop it from taking over more and more of his life. John’s mother described the peak of his OCD as an extremely challenging time for her family. “It was really hard because it’s like we had lost our son. He was so trapped in the OCD. We couldn’t physically touch him. There was no spontaneity anymore. We couldn’t even sit across the table and talk anymore.”

Reinforcing anxiety

While the parents who accommodate their child are well intentioned, family accommodation is known to reinforce their child’s symptoms. Since anxiety is maintained through avoidance, family members who accommodate their child are causing the symptoms to become even more fixed.

Since anxiety is maintained through avoidance, family members who accommodate their child are causing the symptoms to become even more fixed.

“Before I knew what accommodation was, I thought I was helping,” said John’s mother. “I was heartbroken when I found out the definition of accommodation. I was devastated to know I was feeding the OCD instead of helping John.”

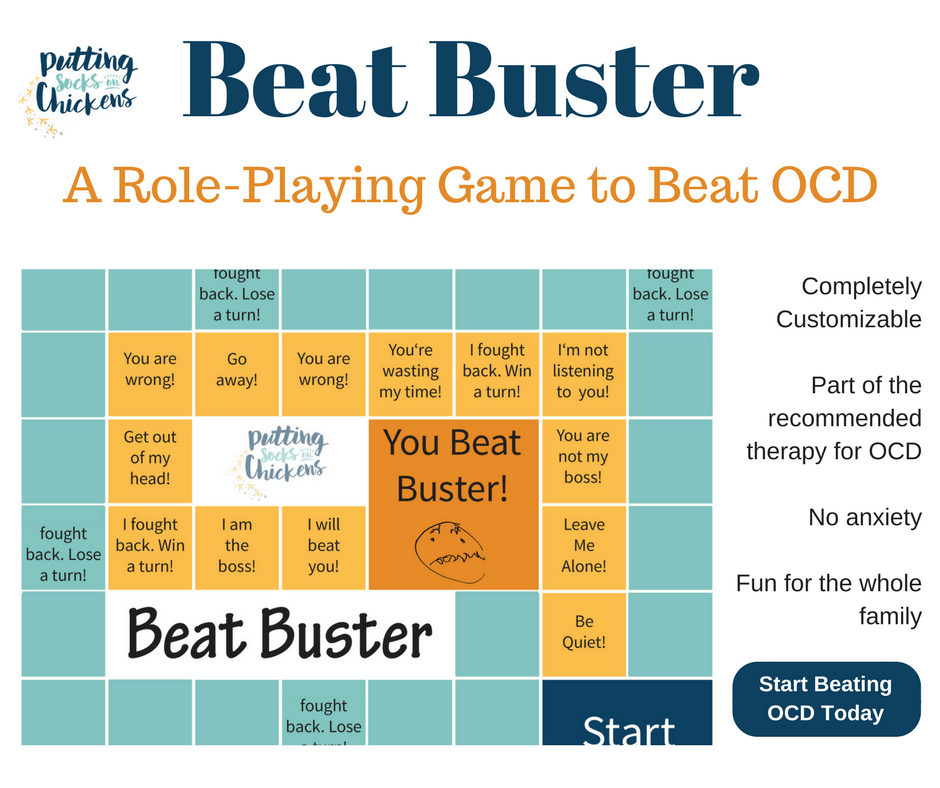

Naming the child’s OCD is one way to reduce the stigma associated with it, and makes the child feel like the anxiety is not who she is. For example, a child may name her OCD “The Bully” or “The Witch.” John’s mother continues: “Divorcing the OCD from John has been huge. Now the family has a common enemy, everyone is in on the battle. Before it was an unnamed invader. Now we know who we’re fighting.”

Building coping skills

Through treatment, parents learn new ways to respond when their children get “stuck” and how to encourage their child to rely on coping skills or to “boss back” their anxiety, instead of relying on their parents to help them through it. The children eventually become much more independent, and the parents may start to realize that anxiety is no longer in charge of their families.

The children eventually become much more independent, and the parents may start to realize that anxiety is no longer in charge of their families.

Grandparents and siblings can also become involved in family accommodation, although they are not typically included in treatment as regularly as parents are.

“Since grandparents and siblings are more a part of the child’s outside world, they may be more likely to accommodate because they want to maintain peace,” said Dr. Bubrick. “They should be a involved in the treatment so they don’t undermine it.”

Helping kids face fears

Through treatment, family members learn to help their children face their fears instead of avoiding them. Instead of comforting the child, it becomes the parent’s job to remind him of the skills he has developed in treatment and to use them in the moment.

“Now I’m helping John and I’m not feeding the OCD,” said John’s mom. A lot of that is letting John know that he has strength to fight the OCD. Reminding him of the strategies instead of making the world better for him.”

Reminding him of the strategies instead of making the world better for him.”

OCD Resources for Parents | OCD Treatment in Children

Children with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) have intrusive thoughts and worries that make them extremely anxious, and they develop rituals they feel compelled to perform to keep those anxieties at bay. This guide explains the often confusing behaviors that can be associated with OCD in children, and the effective treatments for helping kids who develop it.

What Is OCD?

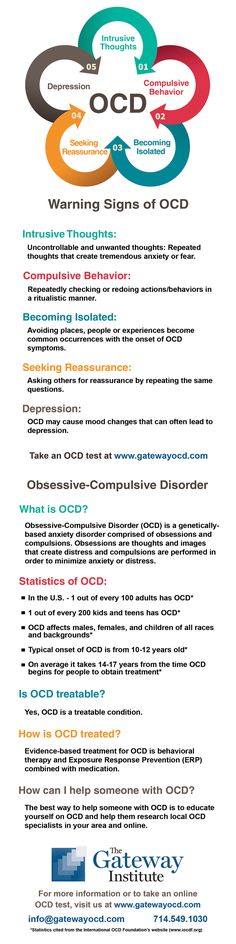

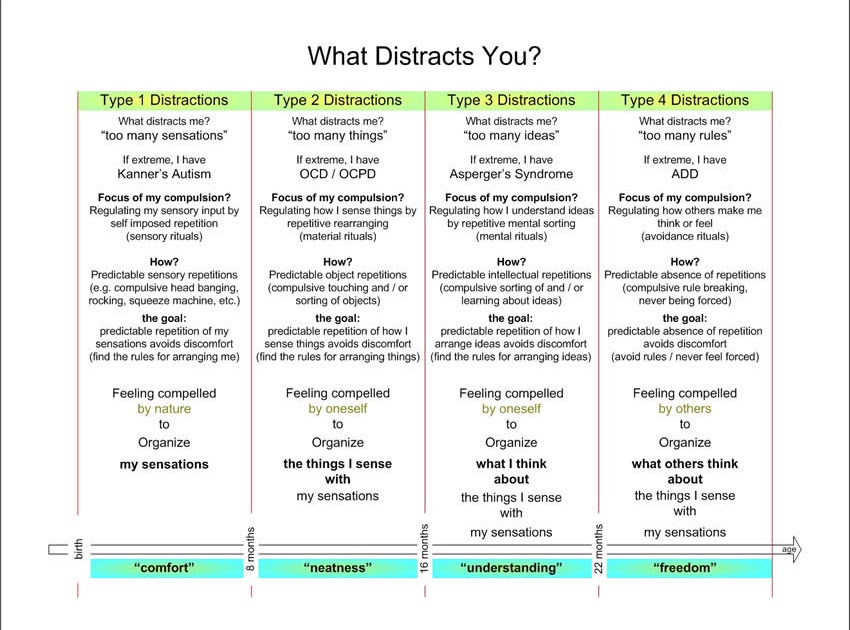

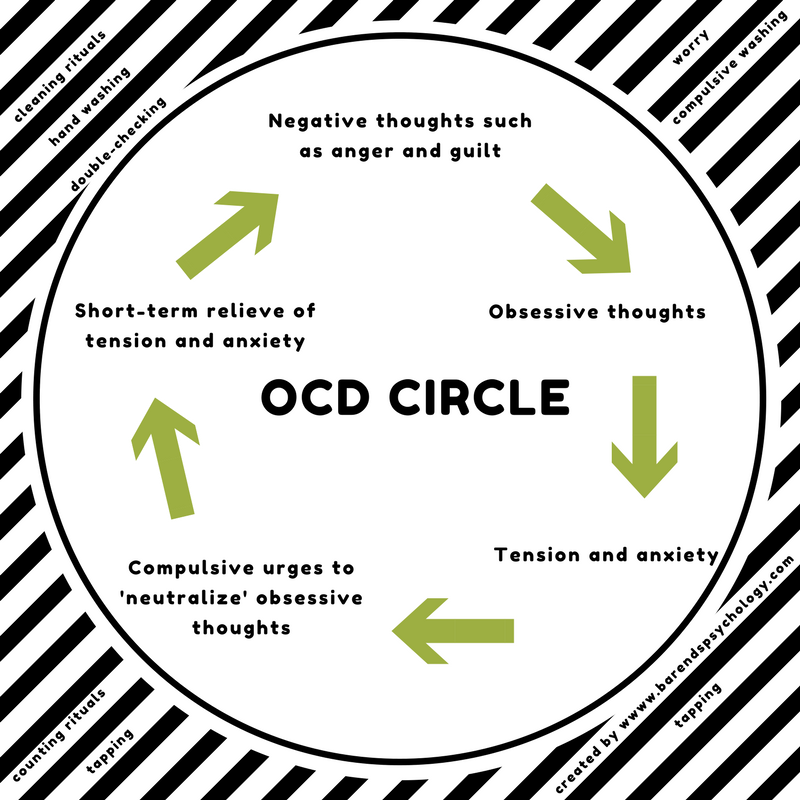

Children who have OCD struggle with either obsessions or compulsions or both. Obsessions are unwanted and intrusive thoughts, images or impulses. Obsessions make kids feel upset and anxious. Compulsions are actions or rituals kids are driven to perform to get rid of anxiety.

To understand how OCD works, think about a mosquito bite. When you get bitten by a mosquito, it itches, so to make it feel better you scratch. While you scratch the bite it feels great, but as soon as you stop scratching, the itching gets worse. That’s how OCD plays out. When a child with OCD feels anxious he’ll do something to fix it temporarily, but that ritual makes it worse over time.

That’s how OCD plays out. When a child with OCD feels anxious he’ll do something to fix it temporarily, but that ritual makes it worse over time.

OCD obsessions fall into a variety of categories, including the below list.

- Contamination: Kids with this obsession are sometimes called “germophobes.” These are the kids who worry about other people sneezing and coughing, touching things that might be dirty, checking expiration dates or getting sick. This is the most common obsession in children.

- Magical thinking: This is a kind of superstition, like “step on a crack, break your mother’s back.” For example, kids might worry that their thoughts can cause someone to get hurt, or get sick. A child might think, “Unless my things are lined up in a certain way, mom will get in a car accident.”

- Scrupulosity: This is when kids have obsessive worries about offending God or being blasphemous in some way.

- Aggressive obsessions: Kids may be plagued by a lot of different kinds of thoughts about bad things they could do. “What if I hurt someone? What if I stab someone? What if I kill someone?”

- The “just right” feeling: Some kids feel they need to keep doing something until they get the “right feeling,” though they may not know why it feels right. So they might think: “I’ll line these things up until it just kind of feels right, and then I’ll stop.”

Compulsions can be things that kids actively do — like line up objects or wash hands — or things done mentally, like counting in their head. A compulsion could also be an avoidance of something, like a child who avoids touching knives, even flimsy plastic ones, because she’s afraid of hurting someone. Because compulsions are things that parents might notice, it is common for parents to be more aware of them than obsessions.

Kinds of OCD compulsions include (but are not limited to):

- Cleaning compulsions, including excessive or ritualized washing and cleaning

- Checking compulsions, including checking locks, checking to make sure a mistake wasn’t made and checking to make sure things are safe

- Repeating rituals, including rereading, rewriting and repeating actions like going in and out of a doorway

- Counting compulsions, including counting certain objects, numbers and words

- Arranging compulsions, including ordering things so that they are symmetrical, even or line up in a specific pattern

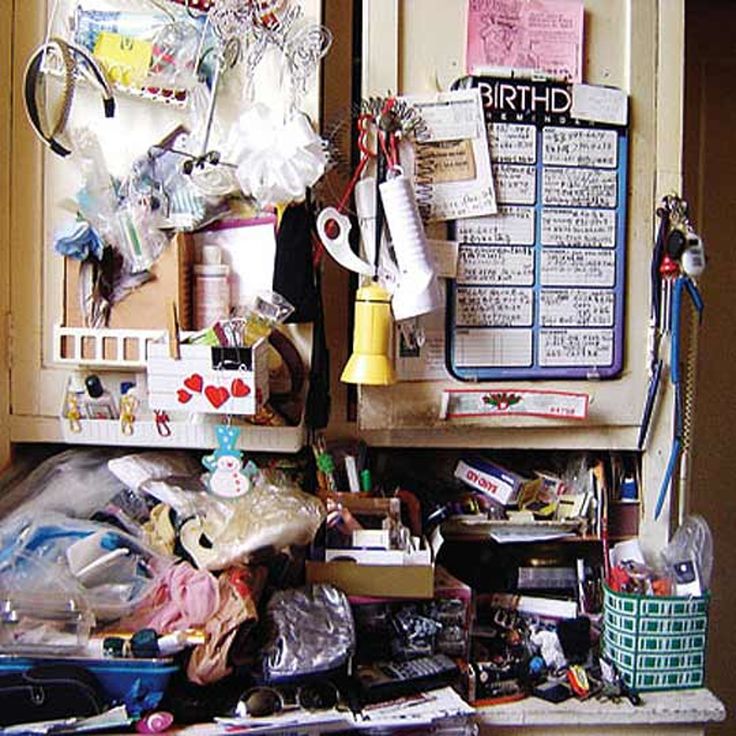

- Saving compulsions, including hoarding and difficulty throwing things away

- Superstitious behaviors, including touching things to prevent something bad from happening or avoiding certain things

- Rituals involving other persons, including asking a person the same question repeatedly, or asking a parent to perform a particular mealtime ritual

Signs of OCD

OCD often first develops around ages six to nine. The disorder can manifest as early as five. Young children experience the disorder differently than adolescents and adults do. A young child may not recognize that his thoughts and fears are exaggerated or unrealistic, and he may not be fully aware of why he is compelled to perform a ritual; he just knows that it gives him a “just right” feeling, at least momentarily. Over time, in the 9-12 range, it evolves into magical thinking and becomes more superstitious in nature.

The disorder can manifest as early as five. Young children experience the disorder differently than adolescents and adults do. A young child may not recognize that his thoughts and fears are exaggerated or unrealistic, and he may not be fully aware of why he is compelled to perform a ritual; he just knows that it gives him a “just right” feeling, at least momentarily. Over time, in the 9-12 range, it evolves into magical thinking and becomes more superstitious in nature.

In either case, a child with OCD will respond to his anxiety in a way that is very rigid and rule-bound and interferes with normal functioning. Parents might notice signs such as:

- Repeated hand washing, locking and relocking doors or touching things in a certain order

- Extreme or exaggerated fears of contamination, family members being hurt or harmed or doing harm themselves

- Use of magical thinking, such as, “If I touch everything in the room, Mom won’t be killed in a car accident”

- Repeatedly seeking assurances about the future

- Intolerance for certain words or sounds

- Repeatedly confessing “bad thoughts” such as thoughts that are mean (thinking a family friend is ugly), thoughts that are sexual (imagining a classmate naked) or violent (thinking about killing someone)

Signs of OCD might not always be obvious. Compulsions can be very subtle, so parents and other caregivers might not notice when a child is doing them, or they might not understand that a particular behavior is a compulsion. Other signs might be invisible to parents, like when a child compulsively counts to a certain number in her head.

Compulsions can be very subtle, so parents and other caregivers might not notice when a child is doing them, or they might not understand that a particular behavior is a compulsion. Other signs might be invisible to parents, like when a child compulsively counts to a certain number in her head.

As children get older and realize that some of their fears are nonsensical, or their behaviors unusual, they might also go to greater efforts to conceal their OCD symptoms from parents, teachers and friends. Children with OCD can sometimes manage to suppress their symptoms in certain situations, like at school, only to explode at home because of the tremendous effort.

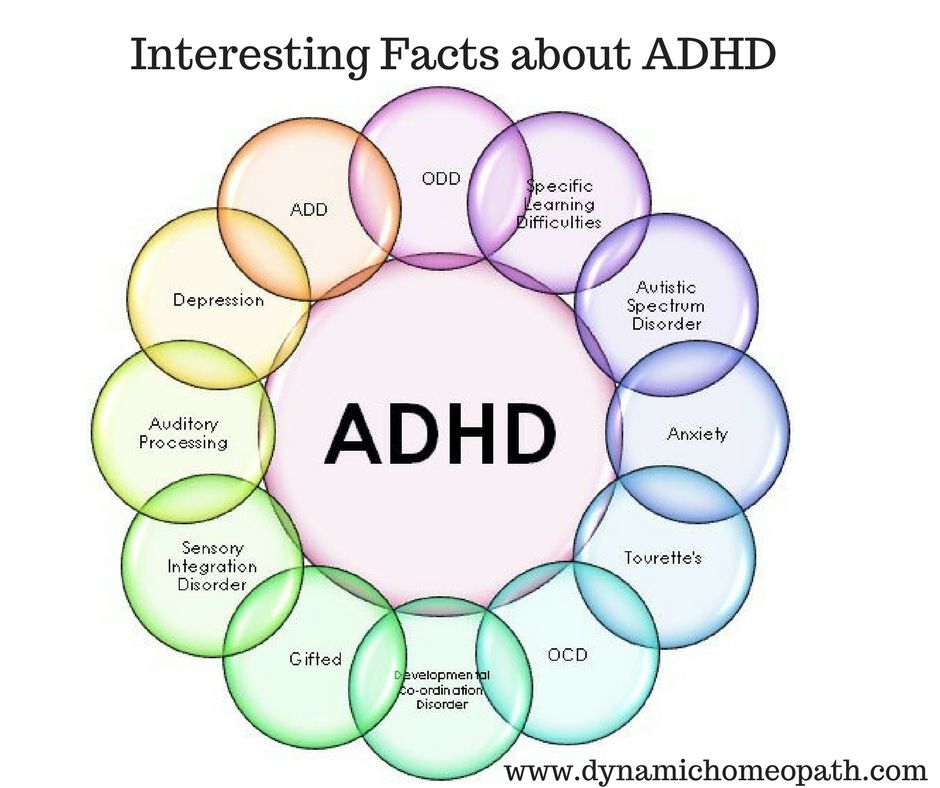

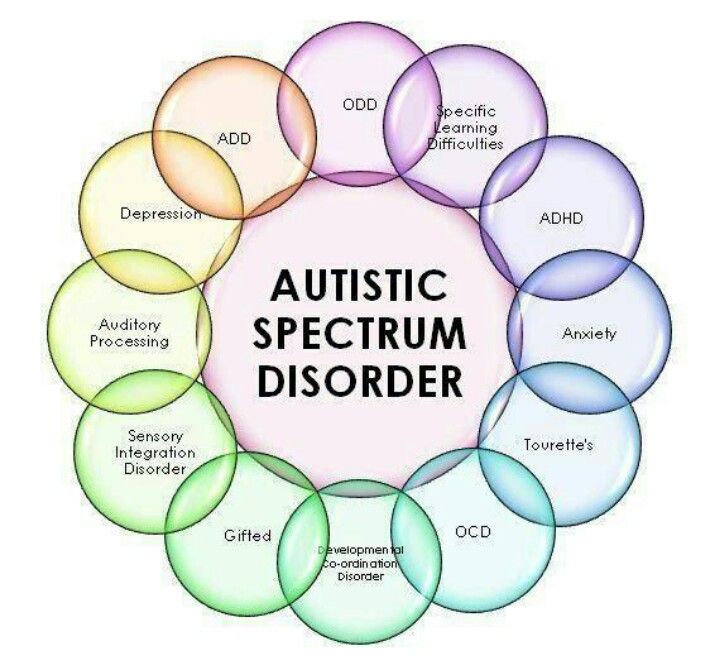

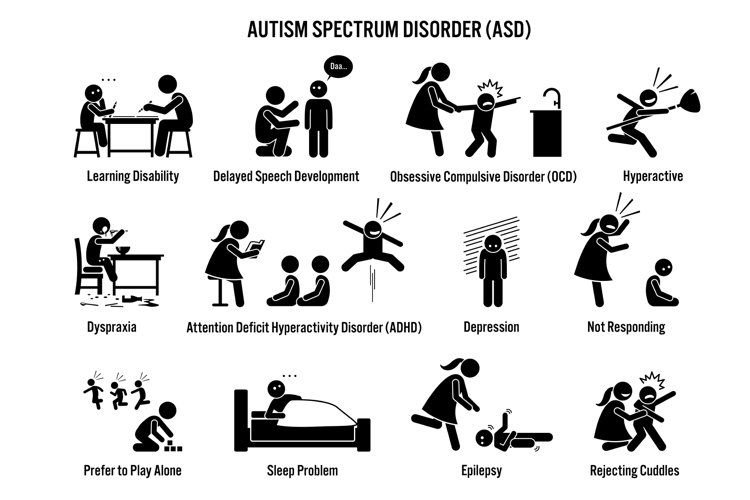

OCD can also be mistaken for a different disorder. Many children with OCD are distracted by their obsessions and compulsions, and it can interfere with their ability to pay attention in school. A teacher might notice a child having difficulty focusing and assume she has ADHD, since her OCD isn’t apparent. It could also be mistaken for an anxiety disorder. And it can be overlooked when a child with OCD also develops depression, which kids with OCD are at risk for, especially without treatment.

And it can be overlooked when a child with OCD also develops depression, which kids with OCD are at risk for, especially without treatment.

What Does OCD Look Like in the Classroom?

Treatment for OCD

Cognitive behavioral therapyThe first step in treatment is helping children understand how OCD works. It often helps to put OCD in a context that children can understand. For example, a clinician might explain that OCD functions like a bully. If a bully asks for your lunch money and you give in because you’re afraid, then the bully will be happy and go away. But the next day the bully will come back for more, because he knows you are afraid. The more you give in to a bully the more he will ask for. OCD functions the same way. The goal of treatment is to help a child learn how to stand up to his bully.

The gold-standard treatment for OCD is a kind of cognitive behavioral therapy called exposure and response prevention, or ERP. ERP works by helping children face the things that trigger their anxiety in structured, incremental steps, and in a safe environment. This allows children to experience anxiety and distress without resorting to compulsions, with the support of the therapist. Through facing their triggers children learn to tolerate their anxiety and, over time, they discover that their anxiety has actually decreased.

ERP works by helping children face the things that trigger their anxiety in structured, incremental steps, and in a safe environment. This allows children to experience anxiety and distress without resorting to compulsions, with the support of the therapist. Through facing their triggers children learn to tolerate their anxiety and, over time, they discover that their anxiety has actually decreased.

For example, a child with fears about germs and contamination would create a “fear hierarchy” with his therapist. They would work together to identify all of the contamination situations he fears, rate them on a scale of 0-10, and then tackle them one at a time until his fear subsides. The child would start with a low-level trigger, such as touching clean towels, and build to more difficult triggers, such as holding something from the trash.

Because children often have symptoms that are specific to settings outside the clinical office, at home or in restaurants, for instance, it is important for treatment to move outside the office as needed. Your clinician should provide ERP in real world locations where your child experiences anxiety, and make sure that caregivers know how to reinforce ERP skills outside of treatment, too.

Your clinician should provide ERP in real world locations where your child experiences anxiety, and make sure that caregivers know how to reinforce ERP skills outside of treatment, too.

For most cases of mild to moderate OCD, treatment once a week for 12-15 weeks is usually enough to get strong results.

Working with parentsParents spend the most time with their children, so it is essential for family to be involved in treatment. You should expect your child’s clinician to work closely with you, explaining how treatment works and giving you and your child homework to practice the skills your child is learning in therapy.

Because children often come to parents looking for reassurance or to help with an obsession or compulsion, it is also important for parents to learn the best way to respond to their child without reinforcing her OCD. When a parent gives reassurance, it makes the child feel better in the moment, but that relief is fleeting and can actually reinforce the child’s anxiety in the long run. It also doesn’t help her learn any coping skills to help herself — only that asking mom or dad will help.

It also doesn’t help her learn any coping skills to help herself — only that asking mom or dad will help.

Similarly, if your child has an aversion to a certain word, your family might have learned to avoid saying that word and apologize if someone accidentally uses it. However inadvertent, this also reinforces the OCD because it doesn’t give the child a chance to overcome her anxiety. Your child’s clinician should work with you on finding ways to respond to requests for reassurance that are supportive without reinforcing OCD symptoms.

Intensive CBT and hospitalizationFor children with severe symptoms, weekly or even twice-weekly therapy sessions might not be effective enough. If your child’s symptoms are seriously interfering with school performance, family life and friendships, and if typical treatment isn’t helping, you may want to consider a treatment program that is more intensive.

Some institutions that specialize in OCD, like the Child Mind Institute, offer intensive treatment programs that allow children to be seen several times a week, compressing treatment and helping children make more gains faster. These programs can have a transformative effect on children struggling with severe OCD, and can many times prevent hospitalization.

These programs can have a transformative effect on children struggling with severe OCD, and can many times prevent hospitalization.

An inpatient hospitalization program is another option for children with severe OCD who are not getting the help they need from traditional outpatient treatment. After an inpatient OCD hospitalization, a child may be recommended to participate in an intensive outpatient program to help ease his transition away from being in a clinical environment and to help him maintain the gains he has made.

Medication treatment for OCDWhile the primary treatment for OCD is cognitive behavioral therapy, children with more severe cases are often treated with a combination of CBT and medication. A class of antidepressant medication called SSRIs, or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, can be used to help reduce a child’s anxiety, which in turn allows the child to be more responsive to therapy. Medication can be decreased or discontinued as the child learns skills to help her overcome her anxiety on her own.

Sometimes other types of medicines can be prescribed to control excessive irritability or anger that may be complicating treatment.

Kids and OCD: The Parents’ Role in Treatment

Intensive Treatment for OCD and Anxiety

Related Disorders

It is not uncommon for children with OCD to struggle with more than one disorder. Depression, eating disorders and panic disorder can frequently occur alongside OCD. If your child is diagnosed with multiple mental health disorders, it is important for him to receive specialized treatment for each disorder. Cognitive behavioral therapy for OCD, for example, will help a child with his OCD but will not help with his depression.

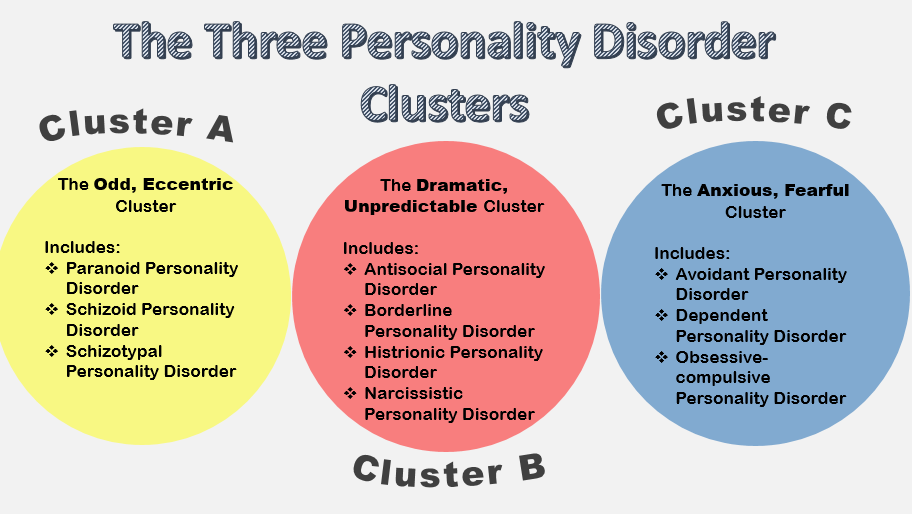

Care should be taken during diagnosis to determine if a child only has obsessive-compulsive disorder, or if the child has OCD and another disorder, or perhaps a disorder that is similar to OCD but is actually a separate disorder such as acute-onset OCD or a disorder on the “obsessive-compulsive spectrum. ”

”

There is a spectrum of disorders that share some characteristics with OCD and are treated in similar ways. These include:

- Trichotillomania

- Tourette’s syndrome

- Illness anxiety disorder (or somatic symptom disorder)

- Hoarding

- Body dysmorphic disorder

- Skin picking (or excoriation disorder)

- Chronic tic disorders

While these disorders have similar clinical characteristics — and some experts believe that they may have the same underlying neurobiological causes as OCD — they differ from OCD in certain ways and therefore require a specialized treatment.

One distinction worth making is between OCD and two other disorders that involve obsessive thoughts: illness anxiety disorder (a child is obsessed with the idea that she has a serious illness despite not having symptoms) and body dysmorphic disorder (a child obsesses on a minor or imagined flaw in her appearance). The difference is the extent to which a child believes her thoughts. For example, a child with OCD may know her obsessions are irrational and yet have so much anxiety that she feels the need to perform compulsions to reduce the anxiety anyway. A child with illness anxiety disorder or body dysmorphic disorder, however, may believe her thoughts are based in reality. Children with these disorders usually need cognitive therapy and strategies to gain insight into the irrationality of their obsessions before they can begin exposure and response prevention therapy. If they receive ERP before they are cognitively prepared for it, then their anxiety may actually worsen over time.

The difference is the extent to which a child believes her thoughts. For example, a child with OCD may know her obsessions are irrational and yet have so much anxiety that she feels the need to perform compulsions to reduce the anxiety anyway. A child with illness anxiety disorder or body dysmorphic disorder, however, may believe her thoughts are based in reality. Children with these disorders usually need cognitive therapy and strategies to gain insight into the irrationality of their obsessions before they can begin exposure and response prevention therapy. If they receive ERP before they are cognitively prepared for it, then their anxiety may actually worsen over time.

Hoarding, skin picking, trichotillomania and tic disorders including Tourette’s can be treated by exposure and response prevention and other behavioral strategies.

Working With the School

Many times children will experience OCD symptoms at school. If this is the case for your child, it will be helpful to get his school on board with treatment. Often the first step is helping teachers and administrators at the school understand OCD. Educating the school is particularly important because many behaviors associated with OCD can be mistaken for something else, like oppositional behavior, learning problems or another disorder. For example, a child’s OCD symptoms might make him distracted, which could look like ADHD, or make him take a very long time on tasks and tests, which could look like a learning problem. An emotional outburst might be caused by another student triggering his OCD. When teachers understand what a child’s particular challenges are — and that he’s not just being difficult — they will be better able to help him.

Often the first step is helping teachers and administrators at the school understand OCD. Educating the school is particularly important because many behaviors associated with OCD can be mistaken for something else, like oppositional behavior, learning problems or another disorder. For example, a child’s OCD symptoms might make him distracted, which could look like ADHD, or make him take a very long time on tasks and tests, which could look like a learning problem. An emotional outburst might be caused by another student triggering his OCD. When teachers understand what a child’s particular challenges are — and that he’s not just being difficult — they will be better able to help him.

You child’s clinician should be able to give specific advice on the best way to work with the school, including explaining your child’s OCD triggers, setting up a plan for how the teacher can help your child if he feels his symptoms coming on, and minimizing any behavioral problems or challenges. Clinicians sometimes will go into the school to help train teachers on how to support a student with OCD.

Your child’s clinician may also be able to suggest strategies to help your child focus on learning, such as preferential seating and private testing rooms to minimize distraction, or extended time on tests and papers and use of a laptop to minimize negative consequences from perfectionism.

Teachers Guide to OCD in the Classroom

Treatment of childhood obsessive-compulsive disorder OCD in Israel

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is also known as obsessive-compulsive disorder. This disorder affects 1% to 4% of children. About half of cases begin in childhood and continue into adulthood.

Anxiety is observed in children suffering from OCD, which manifests itself in a pronounced need to organize the world around them in a special way. They ask to retell what they have already been told many times, or to play the same game many times.

[SLIDER=1661]

R&D includes 2 components:

-

Obsessions or obsessions.

The child constantly pronounces the same thought, returns to the same memories - both in the form of visual images and in the form of inner speech. The child may be constantly disturbed by the obsessive thought of pollution. He constantly wants to wash, avoid dirty places. He may require strict order in the house, symmetry in the arrangement of objects. If something is disturbed in his habits, this causes increased anxiety. The child may also be concerned about their own health and the health of their loved ones.

The child constantly pronounces the same thought, returns to the same memories - both in the form of visual images and in the form of inner speech. The child may be constantly disturbed by the obsessive thought of pollution. He constantly wants to wash, avoid dirty places. He may require strict order in the house, symmetry in the arrangement of objects. If something is disturbed in his habits, this causes increased anxiety. The child may also be concerned about their own health and the health of their loved ones. -

Compulsive actions or obsessive behavior is the second component of the syndrome. We are talking about repetitive behavioral rituals, which must be observed strictly in a strict order, otherwise, according to the patient, something bad may happen. Such rituals include constantly washing hands, touching certain things in a certain order with the hands, and much more. It should be noted that children, unlike adult patients, try to tell their parents about their rituals, which increases the chances of recovery.

Unfortunately, parents do not always listen to children's experiences, and this contributes to the further development of the disorder.

Unfortunately, parents do not always listen to children's experiences, and this contributes to the further development of the disorder.

When diagnosing obsessive-compulsive disorder, the Matspen Center conducts a comprehensive study of the patient's mental state to identify or exclude another concomitant disease. A complete physical examination of the patient is also carried out in order to determine contraindications to certain medications, as well as to establish possible physical prerequisites for the development of OCD.

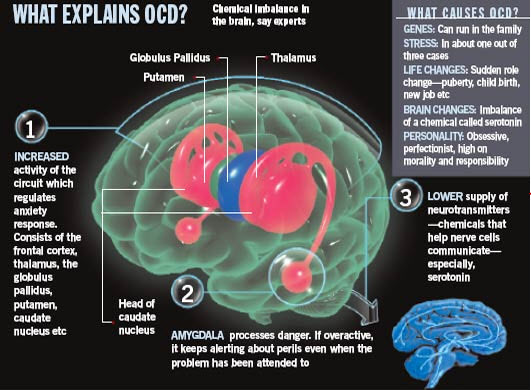

The main cause of OCD in a child may be structural or functional changes in the functioning of the anterior lobe of the brain - the ventral-medial pre-frontal cortex. This part of the brain is responsible for repetitive actions, rituals in human behavior. The pathology associated with the development of addictions to repetitive actions is also localized there. This area is associated with areas responsible for emotions, anxiety, thoughts and desires. In this way, a brain functional network is created that supports OCD. This cause can be revealed during fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging).

In this way, a brain functional network is created that supports OCD. This cause can be revealed during fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging).

why it happens and how to treat it

OCD in children: why it happens and how to treat it© Anastasia Ryzhkova

Psychiatrist Elisey Osin talks about obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Elisey Osin

Child psychiatrist

OCD (obsessive-compulsive disorder) in children is a serious illness for parents. Endless rituals - knock 5 times, swipe, ask the same question 25 times, etc. - can cause irritation that only increases guilt, fear and powerlessness.

The most acute and frequent questions of parents about OCD are answered by child psychiatrist Elisey Osin, an expert at the Vykhod Foundation.

- What is OKR? How to recognize it?

- OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder is a disorder that consists of thoughts, memories, images (obsessions) obsessively invading a person's mental activity, which come again and again and cause anxiety or discomfort; and repetitive actions, rituals (compulsions) that a person needs to reduce the discomfort or anxiety associated with obsessive thoughts and experiences.

Obsessive thoughts in OCD create a lot of stress, anxiety, tension, and greatly interfere with daily life. And it's not just the experience of "whether I closed the doors or turned off the iron." Obsessions can be very different: they can be very frightening, for example, a child may think that a loved one wants to kill him, or, conversely, he himself can kill a loved one, or that he has become contaminated internally or externally from contact with some objects ; and there are obsessions that are not frightening, but very disturbing, for example, when a child needs to count something or repeat a certain number of times.

Rituals for OCD have a protective function. I go to wash my hands or I go to my parents to make sure again and again that everything will be fine, I will not die, I will not get sick. If I wash my hands three times three times, if I turn the key, if I go up to my mother and my mother says exactly these words, just like that, everything will be fine. The essence of the ritual is not very important, the function is important: everything will be fine, I will not experience this discomfort, I will not cry, I will not get infected today, I will not become dirty, I will not ...

- How to understand that this is not a childish fantasy, but OCD?

- Fantasies are usually pleasant for a child: he creates imaginary worlds, and this does not cause him stress. Children with OCD experience a lot of stress. And repetitive actions do not cause pleasure, they are designed to reduce anxiety.

- How to distinguish OCD from other conditions that are also accompanied by obsessions and fears? For example, from increased anxiety, psychological trauma?

- In post-traumatic disorders, obsessive experiences are associated with the situation of trauma, you can trace the moment of their occurrence.

Anxiety itself is a disorder. A person with increased anxiety lives poorly, he thinks all the time that something can happen. A child who is experiencing increased anxiety needs help. Anxiety interferes with development. If you constantly think about your own safety, you cannot function normally. It is necessary to understand what causes this increased anxiety and work with the causes of anxiety.

How do you differentiate “normal” anxiety from OCD? According to the result: they give actions aimed at relieving anxiety, the effect or not. If you checked the doors three times when leaving the house and calmed down, there are no difficulties - this is a normal interaction with the world, which is not always safe. If there is no calming, if you have to engage in complex rituals to cope with anxiety, if it interferes with daily life, it is possible that this is an obsessive-compulsive disorder.

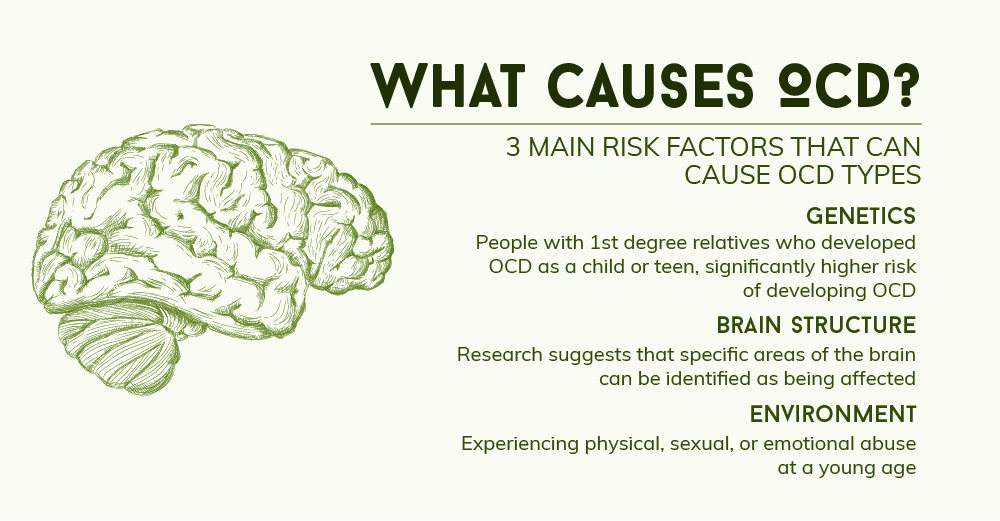

— What can cause OCD in children?

- It is very rare to single out one reason. Most often, several factors in the development of OCD are identified.

Most often, several factors in the development of OCD are identified.

Predisposition to develop OCD. There is no direct link between parent and child OCD. But if mom or dad has OCD, then the child has a significantly higher risk of developing OCD. Studies show that families of children with OCD are noticeably more likely to have various forms of anxiety disorders.

There are some characteristics of thinking associated with obsessive-compulsive disorder. People analyze the world in a certain way, and everyone has certain distortions; people with OCD have very specific distortions, very specific cognitive errors.

Apparently, certain parenting styles contribute to the development of cognitive distortions. It is possible that intense or very prolonged stress can contribute to the development of OCD.

Sometimes OCD and its symptoms can be caused by the presence of a streptococcal infection in the body.

— How exactly can OCD in a child be related to upbringing? Conditionally, are the parents to blame for yelling / criticizing - and now they brought the child to a nervous breakdown?

The cognitive distortions inherent in OCD can occur when a child is made to take responsibility not only for their own actions, but also for their own thoughts. Cognitive error, when a person feels responsible for their own thoughts, is one of the important factors in OCD.

Example. The child screams: “Mom, I hate you, I want you to feel bad, why did you forbid me to play the tablet?”. Mom says: “How can you think like that, you can’t think like that, when such thoughts come to your mind - you are bad! It is a great sin to think like that, you have no right to think like that.”

Notice the difference with "don't you dare talk about your mother like that." The ban on "speaking" is a ban on action, not a ban on thoughts, and it has the right to exist, because the child broadcasts the threat of violence - and this should be discussed with children.

The cognitive distortions inherent in OCD can be caused by evaluating certain thoughts as unacceptable or sinful. They try to force the child to take control over what he has no control over - over his own thoughts, and the child begins to experience great discomfort when forbidden thoughts come to him.

How should parents behave in the given situation? It is better to discuss with the child his and your feelings, not thoughts! Voice them and look for an acceptable way of expressing them.

- We have a normal family. We do not yell at the child and do not humiliate him, but he is still anxious, afraid of the dark and suffers from obsessive thoughts. Why is that?

“Because OCD doesn’t just come from upbringing—it’s also a biological disorder. In addition, it is not always necessary to offend a child or yell at him in order to trigger severe anxiety in him. It is enough to convey to him the idea that everything that we think necessarily returns to us. That the world reacts to our thoughts and changes depending on them. One of the causes of OCD is a sense of responsibility for something that is out of your control - for your own thoughts, as I said.

That the world reacts to our thoughts and changes depending on them. One of the causes of OCD is a sense of responsibility for something that is out of your control - for your own thoughts, as I said.

- Well, if the child's behavior is seriously similar to OCD, what exactly should parents do?

- First . Run diagnostics. See a specialist to determine if what is happening to the child is OCD or another disorder. This could be a psychotherapist working with mood disorders and anxiety, a psychologist working with cognitive behavioral therapy, or a psychiatrist. Whether it is necessary to conduct any instrumental examinations, whether it is necessary to take a blood test for the presence of a streptococcal infection in the body, the doctor will decide. The doctor will also determine the severity of the situation, as well as whether the child has depression. OCD and depression often go hand in hand. It is important to understand whether a child thinks, for example, about suicide, whether he also experiences depressed mood, melancholy in addition to obsessions, or his difficulties are limited to OCD symptoms.

Second. Determine the optimal treatment regimen. Treatment is prescribed depending on the degree of stress experienced by the child. In some situations, the only treatment will be to reassure the parents, give advice on organizing the day, discuss with the child what is happening to him, and teach simple relaxation techniques.

In complex cases, we go in three directions at the same time - we prescribe medications, begin psychotherapy, and conduct intensive family education in order to clarify the nature of the disorder.

If obsessive-compulsive disorder is complicated by something else—depression with suicidal behavior, highly violent behavior—the situation may sometimes require hospitalization, not because of the OCD itself, but because of the accompanying problems. Or more intensive pharmacological treatment is needed, not only with antidepressants, but also with mood stabilizers.

Third. Treatment, psychotherapy, work with parents.

— Doctors often prescribe pills for OCD. Can't do without them?

The symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder vary from person to person. Doctors look at how much stress the manifestations of OCD cause, how much they interfere. Sometimes the stress is mild, expressed only in anxiety, and this can be seen at the first meeting - by the way parents and the child talk about it. Then drug treatment may not be needed at all - psychotherapy is enough. But it happens that OCD affects a child very strongly: he is constantly in anxiety, constantly in rituals, cannot calm down, it is clearly hard for him. In such a situation, we usually try to use all the possibilities for help, including drug treatment. The right medications are a relatively quick, very effective, and fairly safe way to deal with some of the worst experiences a child has with OCD.

— Can you get rid of OCD with mild herbal sedatives?

There are no studies on the use of herbal medicines for OCD. In my opinion, getting rid of OCD with herbal sedatives is the same as getting rid of OCD with homeopathy, mud therapy, aromatherapy. If there is relief, it means that something else has worked, and not herbs. For example, parents began to pay more attention to the child, while giving soothing herbs, created a therapeutic environment. Or, in addition to herbs, they began to go to a psychotherapist.

- How to understand that the doctor to whom the child was brought is competent and will not prescribe antidepressants unnecessarily?

- The function necessary for a doctor is the ability to explain why he thought this way and not otherwise, why he prescribed this particular medicine and not another. If a doctor says he prescribes a drug simply because he has ten years of experience and six years of medical education and you don't, he doesn't really explain anything. Personally, I would avoid interactions with such a doctor.

Personally, I would avoid interactions with such a doctor.

If a doctor says: “I made such and such a diagnosis, because, according to modern criteria ...” and, for example, points to a diagnostic manual, this is normal, this is correct. A trusted doctor is willing to share at least a little of his thoughts. This, in fact, is not difficult to do within a fifteen-minute inspection.

It is desirable that the doctor's considerations be given out, at least briefly, in writing, so that after the meeting the parents can re-read them, think over everything, discuss it, turn to another doctor for a second opinion, raise the modern qualifications of diseases, read the literature and compare it with the fact what they were told.

- What is the best way for parents to respond to a child's behavior? It is difficult not to get annoyed when a child waves his arms strangely for the hundredth time / counts sips of water / asks the question “will our plane crash” and at the same time no consolation and reassurance work.

- First. Be sure to ask for help. OCD is a well-studied and well-understood disorder, and it can be successfully treated.

Second. Avoid extremes. First, do not participate in rituals (for example, do not repeatedly dissuade a person that he will die, or that his hands are not dirty), because this only encourages ritualized behavior: the child feels that he is not in control situation and needs adults to cope with anxiety and discomfort. Secondly, avoid devaluing what is happening to the child, for example, phrases like “what are you driving, it’s all nonsense”, “what did you come up with there”, “you are generally sick” or “you are normal, and everything is with you in order".

Third. The main message for a child with OCD should be: “I am with you, I see what is happening to you. I am on your side and I will help you. What's going on in your head really torments you, but it's only in your head. Together we will find a way to deal with this, we will find help.” This is a difficult message because it will mean slightly different things in every situation. For example, somewhere it’s just to hug a child, somewhere it’s to remind about the relaxation techniques that he has learned, somewhere it’s to practice these techniques with him. Sometimes good psychologists working with OCD involve the child's loved ones, as if taking them as partners in therapy, allowing them to go from the beginning of therapy to regaining control over themselves with the client (child).

Together we will find a way to deal with this, we will find help.” This is a difficult message because it will mean slightly different things in every situation. For example, somewhere it’s just to hug a child, somewhere it’s to remind about the relaxation techniques that he has learned, somewhere it’s to practice these techniques with him. Sometimes good psychologists working with OCD involve the child's loved ones, as if taking them as partners in therapy, allowing them to go from the beginning of therapy to regaining control over themselves with the client (child).

- What parents of a child with OCD should not do in any case?

- First. Don't take OCD personally. For some people, obsessions can be directed at other people, for example, “Mom, do you love me?”, “Mom, will you give me to anyone?”, “Mom, am I bad?”

Second. Provocative or aggressive behavior is unacceptable: "If you say that again, I'll give you up!", "If you say that again, I'll really poison you!", "You got me!". This will only lead to an increase in the problems of the child.

This will only lead to an increase in the problems of the child.

Physical aggression, despite the apparent instantaneous effectiveness (some parents practice it, unfortunately), in the future can lead to auto-aggression. For example, parents hit a child who cannot cross the threshold, and he took a step. Parents created intense emotions for the child that overcame his anxiety, but did not remove his fear. And a person learns to cope with his anxieties and fears with the help of pain. At worst, this can lead to him hurting himself in order to cope with his anxiety.

Third. In no case should you refuse treatment.

OCD can sometimes be quiet and unobtrusive to others. For example, a teenager spends a little more time in the bathroom, the child repeats the same thing several times, he has strange habits, and relatives perceive this as eccentricity. Because of this, it seems that there is nothing to worry about, there is no need to treat. At the same time, a terrible struggle can take place inside a person for the absence of discomfort, very unpleasant or interfering obsessions come to his mind, which may not be clearly manifested outwardly, but for a child or teenager this is everyday hell. Or the child is too punctual, arrives on time, tries to do everything according to the rules, studies “excellently”, and in such a situation, parents begin to doubt the need for treatment. While the desire to do everything perfectly is one of the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

At the same time, a terrible struggle can take place inside a person for the absence of discomfort, very unpleasant or interfering obsessions come to his mind, which may not be clearly manifested outwardly, but for a child or teenager this is everyday hell. Or the child is too punctual, arrives on time, tries to do everything according to the rules, studies “excellently”, and in such a situation, parents begin to doubt the need for treatment. While the desire to do everything perfectly is one of the symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Sometimes the basis of the refusal to treat a child is the parents' own internal anxiety. It can be expressed in the conviction that "chemistry" (pharmaceuticals) is harmful, and only what has grown in the garden or in the forest is useful. This is nothing more than their own attempt to control the processes of life and death, because of which parents refuse to help their children (do not give them the medicine they need).

Some parents refuse to take their children to therapy because going to therapy is admitting that there are problems in your family. And because of the fear or prejudice of parents, children do not receive the help they need.

- How to tell relatives and teachers about the child's condition?

- The family in a broad sense (grandparents, uncles, aunts) needs training. The family should be taken to counseling therapists or a psychiatrist, or given OCD literature to read. If there are questions left, they did not understand something, bring them again to a meeting with the doctor so that everyone has a clear and distinct picture of what is happening to the person.

The situation is more complicated for school teachers. Teachers have power over children, and much depends on the personality of the teacher and how he treats the child. If there is contact with the teacher, you need to talk to him in the same way as with relatives. That is, to tell what kind of diagnosis it is, that we are taking medication, that it will be easier, that, of course, it is not dangerous. The more openness in such a situation, the better.

That is, to tell what kind of diagnosis it is, that we are taking medication, that it will be easier, that, of course, it is not dangerous. The more openness in such a situation, the better.

Some teachers may not be very distant and do not want to read and learn anything, they may be afraid of a special child in the class. With such a person it is better to talk simply about increased anxiety, they say, he is very exciting with us, we go to a psychologist.

- How to help a child not be afraid that peers will find out about his condition, that he will be called "mental", teased?

“This is clearly the task of the teacher and the school administration. Children can endure fantastically difficult things if there is a clear teacher's position. I saw a child with a very serious disorder, he had vocalisms, he shouted out “Damn!”, “Damn!” many times during the lesson. The teacher was aware, he knew what it was like for a child to receive treatment, and he spoke to the class several times. The conversation was conventionally as follows: “Vasya has poor eyesight - he is sitting in front; The doctor told Masha that she needed to go to the toilet - she would go to the toilet without asking, when it was convenient for her; and Petya sometimes shouts out, he does it involuntarily, you don’t need to pay attention to it. If you tease Petya, you will make Petya worse, offend him, we don’t do that at home. ” The same goes for educators. Children are amazingly flexible creatures, and they behave the way they were taught.

The conversation was conventionally as follows: “Vasya has poor eyesight - he is sitting in front; The doctor told Masha that she needed to go to the toilet - she would go to the toilet without asking, when it was convenient for her; and Petya sometimes shouts out, he does it involuntarily, you don’t need to pay attention to it. If you tease Petya, you will make Petya worse, offend him, we don’t do that at home. ” The same goes for educators. Children are amazingly flexible creatures, and they behave the way they were taught.

It is very important for the child himself to understand that he is not alone in this situation.

If a child is bullied, then you need to behave as you would with any bullying, regardless of its cause. Bullying does not depend on the characteristics of the child, but on relationships in the classroom and at school, on the norms of interaction adopted there. This must be dealt with and worked on, regardless of the child's diagnosis and, in general, the presence of a diagnosis.

- teenagers

- 2-3 years

- 6-10 years old

We will send you the important and best materials in a week.

You can additionally set up a mailing list in your account.

I agree to the processing of my personal data

This site collects user metadata (cookies, IP addresses and location data).