Healing from lack of object constancy

Object Constancy in BPD and NPD: Causes, Coping, Resources

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission Here’s our process.

Psych Central only shows you brands and products that we stand behind.

Our team thoroughly researches and evaluates the recommendations we make on our site. To establish that the product manufacturers addressed safety and efficacy standards, we:

- Evaluate ingredients and composition: Do they have the potential to cause harm?

- Fact-check all health claims: Do they align with the current body of scientific evidence?

- Assess the brand: Does it operate with integrity and adhere to industry best practices?

We do the research so you can find trusted products for your health and wellness.

Read more about our vetting process.If the fear of losing someone overpowers your ability to bond with them, this may be an opportunity to work on object constancy.

Having people in your life that you love and trust is one of the greatest gifts in the world.

And it’s natural to be disappointed in these people every once in a while. It’s also OK to say goodbye if your lives go in different directions.

However, you may find that you’re falling out with these people more than usual. You may feel constantly disappointed by those around you for unclear reasons.

Maybe you tend to draw out fights or cut people off after they’ve hurt you. Perhaps you feel deep pain when you believe that someone you love isn’t showing up for you.

Sometimes a fear of abandonment gets in the way of having healthy relationships. You may worry that if you get too close to someone, they’re going to push you away.

If you find this fear gets in the way of your relationships, you’re not alone. Research about object constancy and coping mechanisms may help you feel more secure in your relationships.

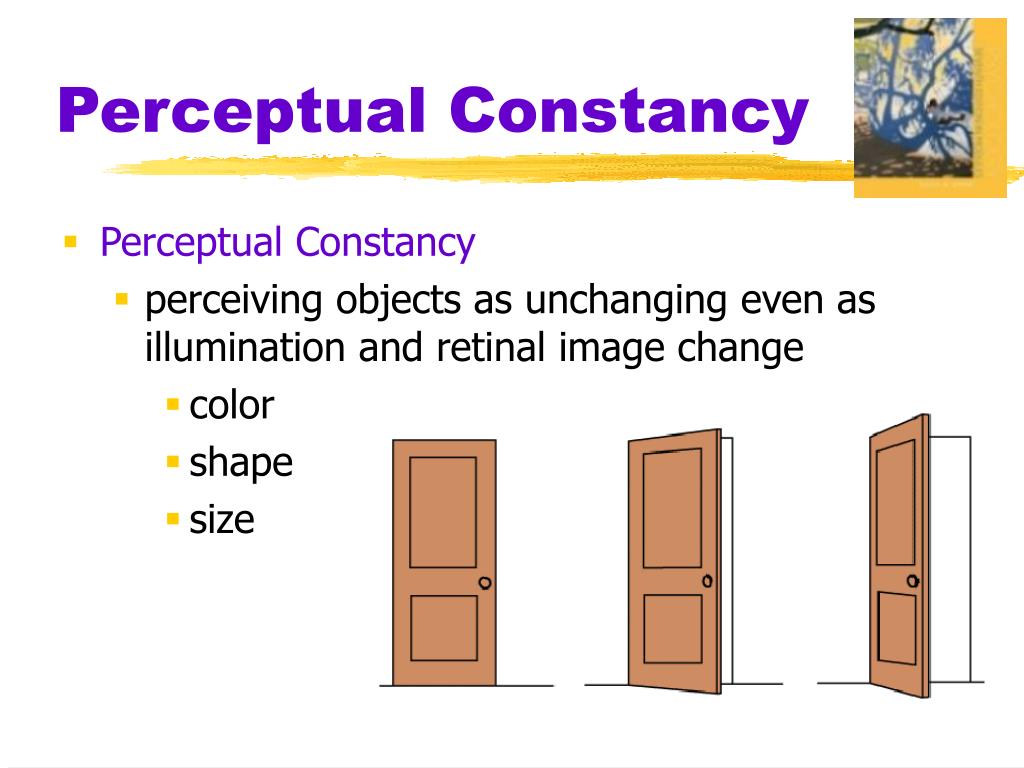

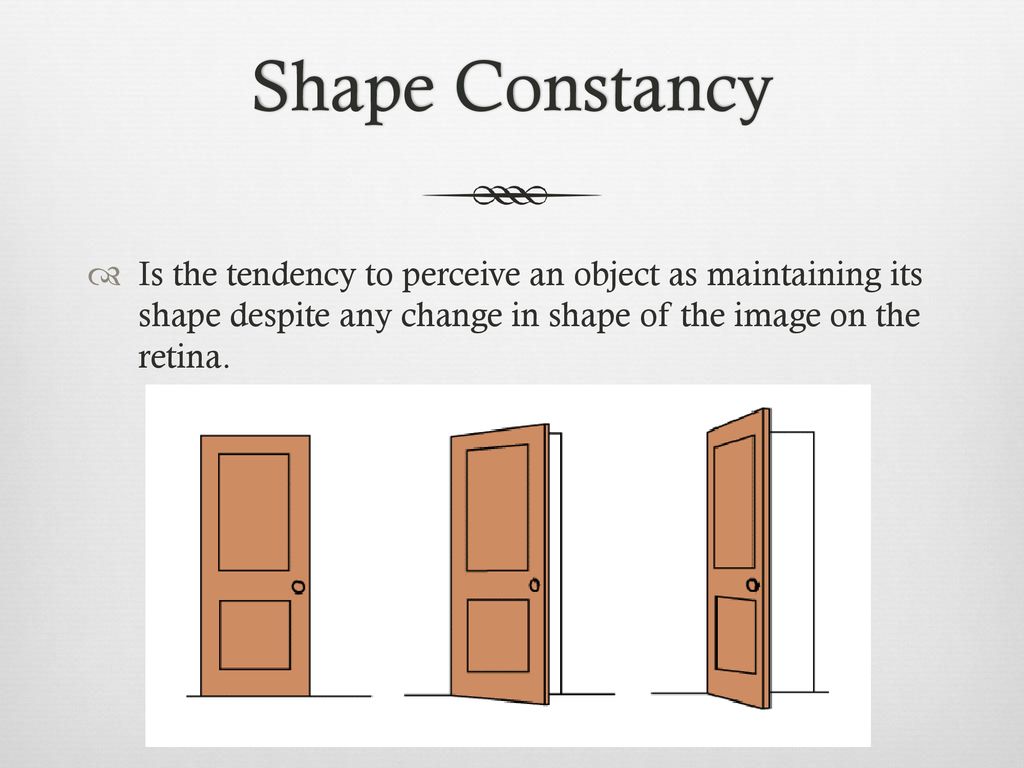

Object constancy is the ability to retain a bond with another person — even if you find yourself upset, angry, or disappointed by their actions.

This particular cognitive skill develops around 2 or 3 years of age. As a child, object constancy sets the foundation for how you will feel about your loved ones when they’re not near you, such as how you feel when your mother leaves the room before your afternoon nap.

When a child develops object constancy, “they begin to understand that when their mother or caretaker leaves them, they are not being abandoned, and their caretaker will return,” explains Dr. Bryan Bruno, the medical director at Mid City TMS.

“Developing object constancy means a child can understand that objects and people retain the same traits even when they are not being actively watched.”

As a child, object constancy helps you deal with separation from your caretaker. As an adult, object constancy allows you to have healthy disagreements with your loved ones and remain close to friends — even if they don’t answer your call or reply to your text.

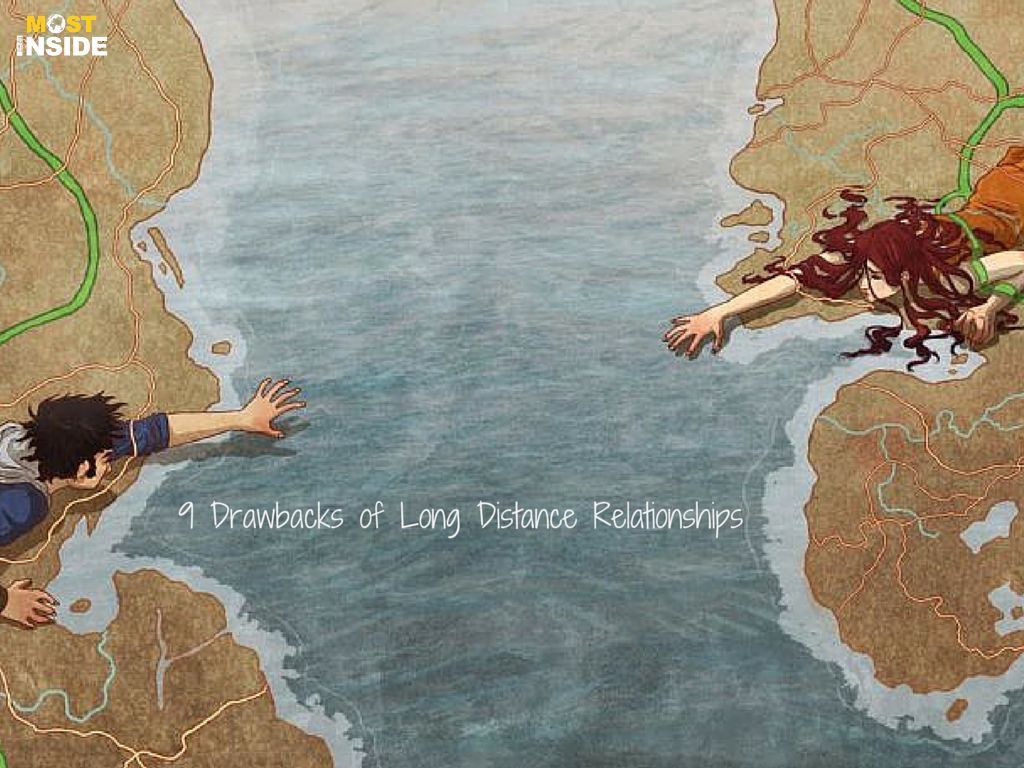

With object constancy, you understand that distance doesn’t mean abandonment and that you don’t need to see, touch, or sense someone to feel supported by them.

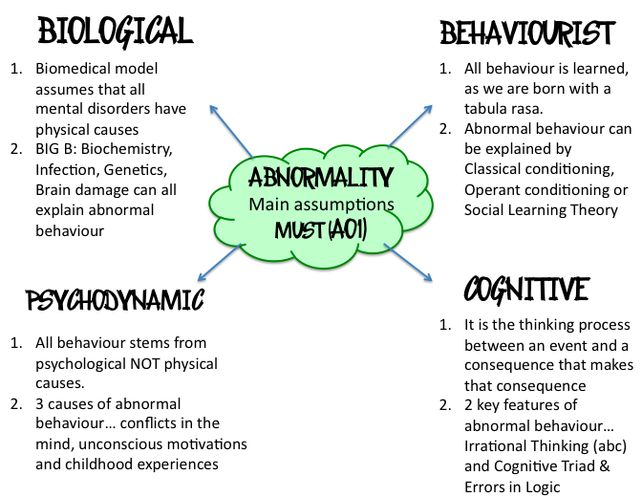

A difficulty with object constancy plays a role in borderline personality disorders (BPD). However, object constancy plays a central role in other personality disorders.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD)“Patients with a borderline personality disorder often struggle with object constancy and find it hard to develop stable mental images of their loved ones,” explains Bruno.

“Consequently, someone with BPD may have a negative perception of the people they care about when they are no longer in their presence.”

For someone with BPD, distance may trigger a fear of abandonment, which may cause avoidance or anger in your relationships.

“People with BPD may not be able to fully understand that someone can have both good and bad aspects that make them whole, which could lead towards unreliable and unstable relationships,” says licensed clinical psychologist Dr. Holly Schiff.

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD)Someone who lives with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) may see things as black and white — all or nothing.

With a lack of object constancy, one may find it difficult to retain positive feelings about someone once they make mistakes or have disagreements within relationships.

“If you do something they don’t like or are unhappy with or they notice a flaw, you suddenly become all-bad, and they devalue you,” explains Schiff.

“They cannot see you as someone that they love and someone who has angered them at the same time.”

With NPD and without object constancy, you may only be able to see people as “high status and special or low status and worthless,” says Schiff.

This can also cause you to find yourself constantly going back and forth on how you feel about your loved ones.

Due to your guardians’ parenting styles or early traumatic experiences, a lack of object constancy typically stems from your childhood.

“If a child was raised in a negative environment with emotionally invalidating or neglectful parents, they don’t receive good instruction on human behavior and managing expectations of loved ones,” explains Bruno.

“As a result, they will often struggle to form stable mental portraits of their loved ones as adults.”

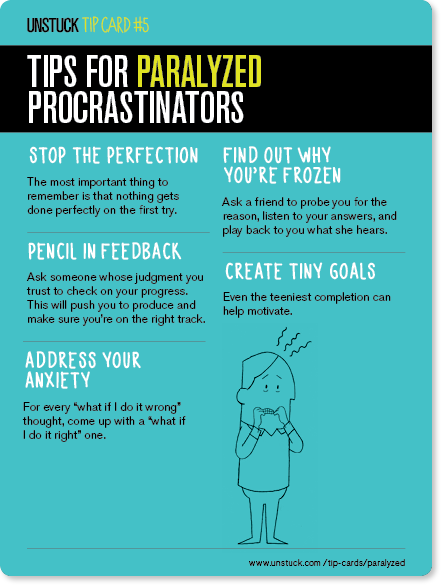

While the roots of a lack of object constancy lay in childhood, you can make steps as an adult to help your relationship with yourself and the people you love.

Working on object constancy as an adult may take time, but it’s certainly doable and recommended.

Over time, you may that it can get easier to build trust, heal from past trauma, and maintain healthy bonds in your adult relationships.

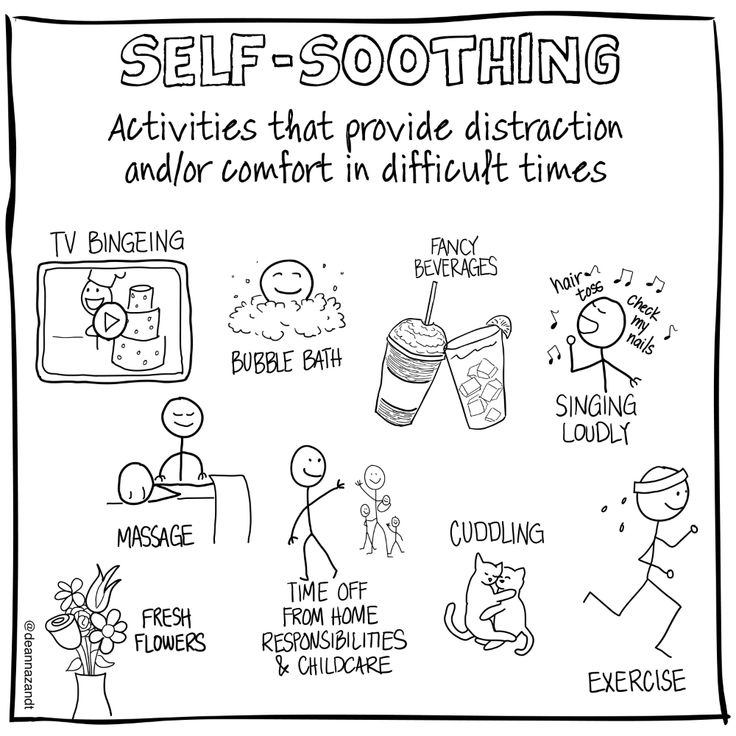

To begin that journey, you may consider several options:

- building trust with a certified therapist

- reading about various attachment styles

- joining a support group with people with similar experiences

- journaling

- practicing mindfulness meditation

Moreover, a 2014 study demonstrated how essential it is for people who live with BPD or NPD to spend time with other people.

Social isolation may dramatically affect how you bond with other people, so be sure to continue to spend time around your friends and loved ones, even as you work on yourself.![]()

Bonding and building healthy relationships with the people you love can bring joy into your life.

If you have a hard time retaining bonds or feeling stable about the people in your life, you’re not alone. You can’t choose your childhood.

Moreover, you should know that mental health professionals can offer you support in working on object constancy — whether you live with BPD, NPD, or neither of those disorders.

As you work with a mental health professional trained to help you cope with object constancy, BPD, or NPD diagnoses, do be sure to take care of yourself. Self-care can help you prevent burnout and show yourself love and patience, rather than judgment.

Even if progress is slow at first, you may work towards seeing people and their actions in their full colors, rather than just black and white.

Object Constancy in BPD and NPD: Causes, Coping, Resources

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission Here’s our process.

Psych Central only shows you brands and products that we stand behind.

Our team thoroughly researches and evaluates the recommendations we make on our site. To establish that the product manufacturers addressed safety and efficacy standards, we:

- Evaluate ingredients and composition: Do they have the potential to cause harm?

- Fact-check all health claims: Do they align with the current body of scientific evidence?

- Assess the brand: Does it operate with integrity and adhere to industry best practices?

We do the research so you can find trusted products for your health and wellness.

Read more about our vetting process.If the fear of losing someone overpowers your ability to bond with them, this may be an opportunity to work on object constancy.

Having people in your life that you love and trust is one of the greatest gifts in the world.

And it’s natural to be disappointed in these people every once in a while. It’s also OK to say goodbye if your lives go in different directions.

However, you may find that you’re falling out with these people more than usual. You may feel constantly disappointed by those around you for unclear reasons.

Maybe you tend to draw out fights or cut people off after they’ve hurt you. Perhaps you feel deep pain when you believe that someone you love isn’t showing up for you.

Sometimes a fear of abandonment gets in the way of having healthy relationships. You may worry that if you get too close to someone, they’re going to push you away.

If you find this fear gets in the way of your relationships, you’re not alone. Research about object constancy and coping mechanisms may help you feel more secure in your relationships.

Object constancy is the ability to retain a bond with another person — even if you find yourself upset, angry, or disappointed by their actions.

This particular cognitive skill develops around 2 or 3 years of age. As a child, object constancy sets the foundation for how you will feel about your loved ones when they’re not near you, such as how you feel when your mother leaves the room before your afternoon nap.

When a child develops object constancy, “they begin to understand that when their mother or caretaker leaves them, they are not being abandoned, and their caretaker will return,” explains Dr. Bryan Bruno, the medical director at Mid City TMS.

“Developing object constancy means a child can understand that objects and people retain the same traits even when they are not being actively watched.”

As a child, object constancy helps you deal with separation from your caretaker. As an adult, object constancy allows you to have healthy disagreements with your loved ones and remain close to friends — even if they don’t answer your call or reply to your text.

With object constancy, you understand that distance doesn’t mean abandonment and that you don’t need to see, touch, or sense someone to feel supported by them.

A difficulty with object constancy plays a role in borderline personality disorders (BPD). However, object constancy plays a central role in other personality disorders.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD)“Patients with a borderline personality disorder often struggle with object constancy and find it hard to develop stable mental images of their loved ones,” explains Bruno.

“Consequently, someone with BPD may have a negative perception of the people they care about when they are no longer in their presence.”

For someone with BPD, distance may trigger a fear of abandonment, which may cause avoidance or anger in your relationships.

“People with BPD may not be able to fully understand that someone can have both good and bad aspects that make them whole, which could lead towards unreliable and unstable relationships,” says licensed clinical psychologist Dr. Holly Schiff.

Narcissistic personality disorder (NPD)Someone who lives with narcissistic personality disorder (NPD) may see things as black and white — all or nothing.

With a lack of object constancy, one may find it difficult to retain positive feelings about someone once they make mistakes or have disagreements within relationships.

“If you do something they don’t like or are unhappy with or they notice a flaw, you suddenly become all-bad, and they devalue you,” explains Schiff.

“They cannot see you as someone that they love and someone who has angered them at the same time.”

With NPD and without object constancy, you may only be able to see people as “high status and special or low status and worthless,” says Schiff.

This can also cause you to find yourself constantly going back and forth on how you feel about your loved ones.

Due to your guardians’ parenting styles or early traumatic experiences, a lack of object constancy typically stems from your childhood.

“If a child was raised in a negative environment with emotionally invalidating or neglectful parents, they don’t receive good instruction on human behavior and managing expectations of loved ones,” explains Bruno.

“As a result, they will often struggle to form stable mental portraits of their loved ones as adults.”

While the roots of a lack of object constancy lay in childhood, you can make steps as an adult to help your relationship with yourself and the people you love.

Working on object constancy as an adult may take time, but it’s certainly doable and recommended.

Over time, you may that it can get easier to build trust, heal from past trauma, and maintain healthy bonds in your adult relationships.

To begin that journey, you may consider several options:

- building trust with a certified therapist

- reading about various attachment styles

- joining a support group with people with similar experiences

- journaling

- practicing mindfulness meditation

Moreover, a 2014 study demonstrated how essential it is for people who live with BPD or NPD to spend time with other people.

Social isolation may dramatically affect how you bond with other people, so be sure to continue to spend time around your friends and loved ones, even as you work on yourself.

Bonding and building healthy relationships with the people you love can bring joy into your life.

If you have a hard time retaining bonds or feeling stable about the people in your life, you’re not alone. You can’t choose your childhood.

Moreover, you should know that mental health professionals can offer you support in working on object constancy — whether you live with BPD, NPD, or neither of those disorders.

As you work with a mental health professional trained to help you cope with object constancy, BPD, or NPD diagnoses, do be sure to take care of yourself. Self-care can help you prevent burnout and show yourself love and patience, rather than judgment.

Even if progress is slow at first, you may work towards seeing people and their actions in their full colors, rather than just black and white.

What is object persistence? - Practical psychology on Aboutyourself.ru

Posted by Tatiana at . Published by Developmental Psychology Last updated: 06/03/2016

Published by Developmental Psychology Last updated: 06/03/2016

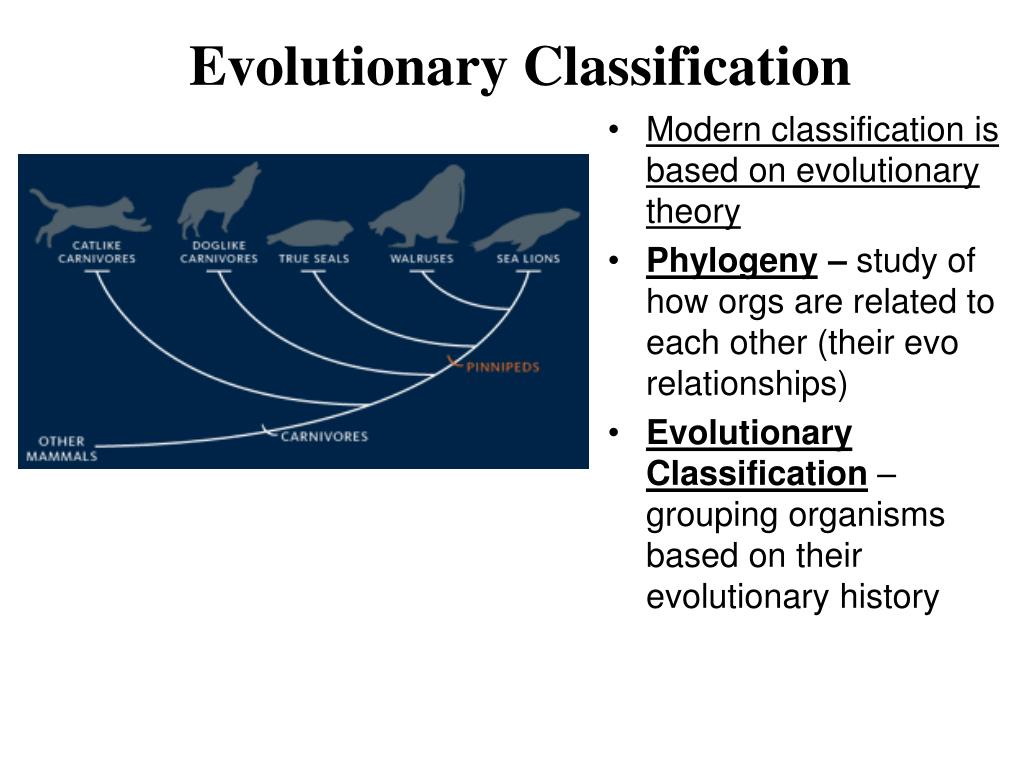

The term "object permanence" is used to describe the child's ability to understand that objects continue to exist even when they are no longer in his field of perception.

If you've ever played the game of peek-a-boo with a very young child, you probably understand how it works. When an object is hidden from their eyes, children up to a certain age become upset, thinking that it has disappeared for good. This is because they are too small to understand that the object continues to exist even if they cannot see it.

Permanence of objects and Piaget's theory

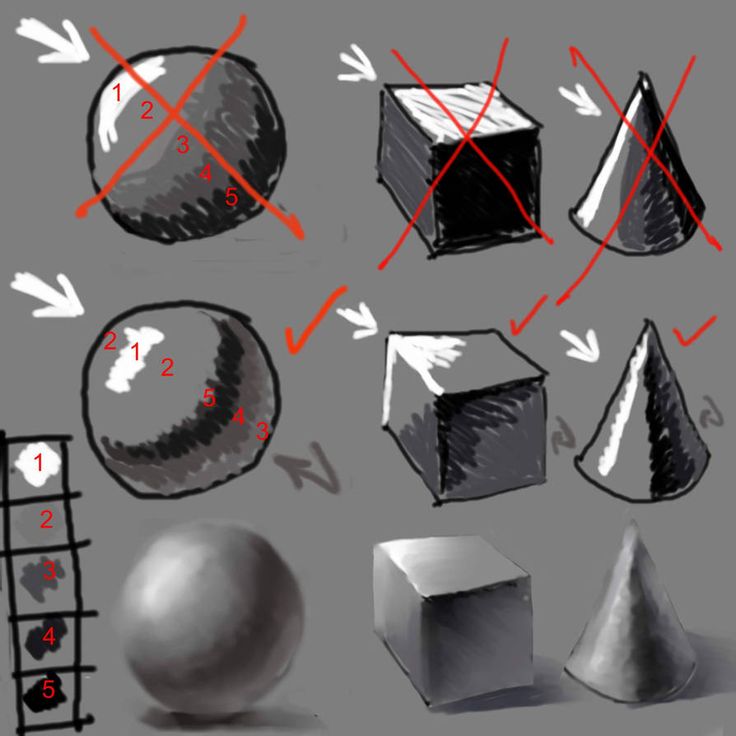

The concept of object permanence plays one of the main roles in the theory of cognitive development created by J. Piaget. At the stage of sensorimotor development (the period that lasts from birth to the age of two), according to Piaget, children learn the world only through perception, with the help of touch, sight, hearing, taste sensations and movements.

At an early age, children are extremely egocentric. They have no idea that the world exists apart from their point of view and experience. To understand that objects continue to exist even when they are not visible, children must first form the idea of them as something autonomous.

Piaget called these mental images schemas. A schema is a category of knowledge about something in the world. For example, a child may have a food schema (at an early age it is either a bottle or mother's breast). As the child gets older and gains more experience, new patterns will appear and old ones become more complex.

How does the ability to perceive objects as permanent develop?

According to Piaget's theory, there are six sub-stages in the stage of sensorimotor development.

- From birth to one month: reflexes. At first, reflexes (or primary circular reactions, according to Piaget) are the main tool for understanding the world.

- From a month to four: development of new schemes.

Later, reflexes lead to the formation of schemas. A child may accidentally suck on his thumb and find that it feels good. Then he will repeat this action precisely because he enjoys it.

Later, reflexes lead to the formation of schemas. A child may accidentally suck on his thumb and find that it feels good. Then he will repeat this action precisely because he enjoys it. - Four to eight months: conscious action. At this age, children begin to pay much more attention to the world around them. And even consciously react to everything that happens. Piaget called this phenomenon secondary circular reactions.

- From eight months to a year: a large study. During this period, the child's actions become much more conscious. Children begin to shake toys so that they make sounds; their response to environmental phenomena becomes more and more coordinated.

- From a year to a year and a half: trial and error. At this stage, tertiary circular reactions appear. Toddlers begin to act by trial and error, with their behavior they specifically try to attract the attention of others.

- From one and a half to two years: the awareness of the permanence of objects is formed.

Piaget believed that figurative thinking is formed between the ages of 18 and 24 months. At this point, children have the ability to form mental images of objects. And because they can now imagine things that cannot be seen, they are able to realize the permanence of objects.

Piaget believed that figurative thinking is formed between the ages of 18 and 24 months. At this point, children have the ability to form mental images of objects. And because they can now imagine things that cannot be seen, they are able to realize the permanence of objects.

In order to determine whether a child is aware of the permanence of objects, Piaget suggested showing him a toy and then hiding it. In one version of this experiment, Piaget hid a toy under a blanket and then watched the baby's actions.

Some of the children got upset, while others started looking for her instead. Piaget believed that children who began to whimper because of the loss of a toy were not yet able to realize its permanence, while those who began to look for it had already reached a certain stage of development.

Critique of Piaget

Piaget's theory remains quite influential and popular even today, but it is often attacked by critical psychologists. One of the main criticisms of Piaget's work is that he often underestimates the abilities of children.

One of the main criticisms of Piaget's work is that he often underestimates the abilities of children.

Recent research on object permanence casts doubt on some of Piaget's conclusions. In particular, the researchers were able to demonstrate that as early as three and a half months old, babies can understand that objects continue to exist even if they cannot be seen or heard.

Other researchers have offered alternative explanations for children not looking for hidden toys. The fact is that very young children lack the strength and coordination needed to find things. In addition, children may simply not be interested in a toy enough to feel the need to look for it.

Tags: children, Jean Piaget

Got something to say? Leave a comment!:

Flight from proximity - Page 29

| Part II. Ways to intimacy | 281 |

counter-addictive habits also requires an understanding of the function of your experiences so that you can use them appropriately.

Mental boundaries

Mental boundaries determine how we perceive the world. They allow us to understand our values, beliefs, thoughts, desires and needs so that we can separate our views and feelings from the views and feelings of other people.

A common violation of mental boundaries related to unmet counter-dependent needs is the setting of boundaries to other people's reality. People who have counter-addictive habits often assume that they know better about life, especially about the life of their children, spouses and subordinates, without even asking about anything. Another well-known violation of mental boundaries is interrupting the interlocutor and depriving him of the opportunity to finish his thought. Attacking, ridiculing, and manipulating the choices of others are also common violations of mental boundaries.

Considering other people's ideas as delusional or stupid is a common way that people with counter-addictive problems violate other people's mental boundaries. To paraphrase a statement by Carl Rogers, if we accept as the basis of our human existence the fact that we all live in our own separate realities, if we can consider these differing realities as the most promising sources in world history for studying each other,

To paraphrase a statement by Carl Rogers, if we accept as the basis of our human existence the fact that we all live in our own separate realities, if we can consider these differing realities as the most promising sources in world history for studying each other,

282 Janey B. Weinhold and Berry C. Weinhold. Escape from intimacy

if we can live together fearlessly learning from each other, then we can say that a new era is beginning [2].

Denial is another well-known form of breaking mental boundaries. People with counter-addictive habits deny not only their personal problems, but also the views of other people, using this as a way to maintain control and prevailing influence. Healing the wounds you received as a child when your mental boundaries were violated

involves developing a stronger sense of object permanence: the ability to recognize your worth even when others attack your thoughts or ideas, and

when you make a mistake.

Developing object permanence and healing old soul wounds requires a safe space within you in which you can explore your own ideas, beliefs, attitudes and feelings. In it, you can begin to create your own perspective on who you really are and how the world is unfolding outside of your family of origin. Journaling can be a great way to do this; it will help you come to terms with your need to be perfect and always look good in the eyes of others, as well as really get other people recognition of your achievements. When you write in a journal, you are only talking to yourself.

In it, you can begin to create your own perspective on who you really are and how the world is unfolding outside of your family of origin. Journaling can be a great way to do this; it will help you come to terms with your need to be perfect and always look good in the eyes of others, as well as really get other people recognition of your achievements. When you write in a journal, you are only talking to yourself.

Making and implementing effective agreements can be an important way to establish optimal boundaries. People with counter-addictive habits often have difficulty with both parts of the agreement. What does it mean?

| Part II. Ways to intimacy | 283 |

First, they often enter into agreements that they cannot fulfill, solely because they want to always "be on top" and "look good."

Secondly, the failure to comply with these agreements is usually due to the fact that these people do not want to be controlled! When they break an agreement, they often try to place the blame on others or on circumstances beyond their control and refuse to be held accountable for breaking the agreement.

Spiritual boundaries

Spiritual boundaries allow us to experience higher, more perfect aspects of ourselves. They give us the opportunity to feel the unity and unconditional love of the higher forces of the universe. Spiritual boundaries also help us develop the permanence of the spiritual object and love ourselves unconditionally, even when we consider ourselves imperfect. When children's spiritual boundaries are violated, they often blame themselves for being rude or pushing them away, as well as stop loving themselves and then separate from their spiritual essence. Violation of spiritual boundaries is often perceived as instilling fear or intimidation.

Intimidation is a combination of shame and fear, which implies a highly controlled behavior

striving for perfection, and also carries the threat of death. Statements like: "God will punish you!"

and "You will burn for this!" — the most common form of spiritual

intimidation that many people

with counter-addiction problems experienced in childhood. As part of the perpetuation of a vicious cycle of cruelty, they

As part of the perpetuation of a vicious cycle of cruelty, they

284 Jane B. Weinhold and Berry C. Weinhold. Fleeing from Proximity

Thecan use the same spiritual weapons on others, especially their own children. Children thus learn to perceive God and their parents as cruel and unpredictable punishers. Therefore, people with unsatisfied counter-dependent needs can only consider God as their ally when they seek to control others.

Another form of spiritual transgression used by people with counter-addiction problems is taking on the "role of God." They put themselves on a pedestal and refuse to display human qualities. This position imposes on others the reality of one person without negotiating conditions. It breaks the spiritual boundaries of those who offer their love and kindness or ask for comfort.

Transforming spiritual intrusions usually takes longer than any other kind of boundary trespassing, as they traumatize people's souls. Penetrating the damaged human soul requires many skills, patience, and unconditional love. Transformation of the wounds caused by transgression of spiritual boundaries must be done with care and compassion. This may include long-term listening and establishing harmony with others, being in a continuous state of unconditional positive regard for them, while they open their spiritual wounds. Proper spiritual counseling can even prepare clients to forgive those who have violated their boundaries. When a spiritual wound is finally healed, space is created for the influx of Divine love. In twelve step programs, this phenomenon is sometimes referred to as "spiritual awakening."

Transformation of the wounds caused by transgression of spiritual boundaries must be done with care and compassion. This may include long-term listening and establishing harmony with others, being in a continuous state of unconditional positive regard for them, while they open their spiritual wounds. Proper spiritual counseling can even prepare clients to forgive those who have violated their boundaries. When a spiritual wound is finally healed, space is created for the influx of Divine love. In twelve step programs, this phenomenon is sometimes referred to as "spiritual awakening."

| Part II. Ways to intimacy | 285 |

EXAMPLE FOR DISCUSSION

Jeff suffered from many classic counter-addictive habits. He gave the impression of being well-off and self-confident, but had real difficulties in intimate situations and, as far as he could, avoided feelings. He walled off his feelings and created boundaries to prevent the occurrence of close intimate situations,

in which he feared to be insulted or humiliated.

In psychotherapy we explored the causes of his fears of intimacy by examining childhood experiences in which his boundaries were violated. Most recently, he recalled a childhood incident in which he was sexually abused.

Sexual abuse is one of the most harmful types of boundary violations as it affects all levels: physical, mental, emotional and spiritual. It forever leaves a mark on the fate of the victim, often preserving in her feelings that inspire fear.

Jeff's brother, who was eight years older than him, had anal sex with him when Jeff was six years old. This event was traumatic for Jeff. However, when he told his parents about the abuse, they blamed him for what had happened. None of the parents supported the child when he experienced shock and humiliation. As punishment, his mother spanked him and terribly shamed him. The father refrained from punishment, but said nothing in his defense.

In psychotherapy sessions with us, Jeff spoke

two issues about this case that he would like to work on: his anger towards his brother and his lack of support from his parents.

286 Jane B. Weinhold and Berry C. Weinhold. Fleeing from intimacy

He said, “I should be really angry, brother, but I can't. I still have a hard time showing anger." (From this we deduced that one of the important tasks in working with Jeff will be teaching him how to express anger.)

We asked him:

—Can you imagine how angry you are with your brother?

Jeff thought for a moment and then shook his head:

—No, I can't.

(This let us know that Jeff wasn't ready to confront his abuser yet. If he was, there would be an image in his head. So we switched to another question.)

- Perhaps you need to deal first with a lack of parental support before dealing with the problems you and your brother had?

Jeff leaned to the side and rested his chin on his hand. (This self-supporting gesture indicated to us that Berry should explore the support problem with his parents.)

We asked Jeff if he was interested in working on the support problem with his parents. He thought about it for a minute and said that he would like to role-play the scene when he told his mother and father about the abuse. He asked us to play the roles of his parents, and we agreed. Berry then asked Jeff what he would like to get out of this role play. Jeff replied that he would like to reenact the scene with a new ending, where he would receive support for his experiences from both parents and protection from his brother's encroachment.

| Part II. Ways to intimacy | 287 |

Berry asked Jeff what he should do as a father. Jeff replied, "I want you to scold my brother and protect me from my mother's wrath." Berry then turned to his imaginary brother and said, “Leave Jeff alone! You have no right to do this to him! Get away from him now and never do this to him again!” (By this time, Jeff was behind Berry and huddled as if he was hiding from his older brother. He gave the impression of a frightened six-year-old child. )

Berry then turned to Jeff and asked how he was doing. He replied: “I’m scared, dad. Can you hug me?" Embracing him, Berry said he felt guilty for not protecting him when he needed his father's protection. In addition, Berry assured that he would not allow his brother to offend him anymore.

When Berry asked Jeff what it takes to help Jeff with his mother, Jeff replied, “Can you come with me to talk to her about how she hurt me when she scolded and shamed me?” Berry agreed to do so.

The two of them approached Janey, who was acting as a mother. Jeff began talking about his hurtful remarks and how they affected him. As he spoke, he began to move slowly behind Berry until he was completely hidden from his mother. Berry turned to him and asked, “Are you trying to hide behind me? You are afraid?"

Breathing a sigh of relief seeing Berry come to his rescue, Jeff said, "Can you talk to her instead of me?" (Jeff needed to figure out how to sensibly express his anger to his mother so that he could do the same with his brother later. )

288 Jane B. Weinhold and Berry C. Weinhold. Fleeing from intimacy

Berry addressed Jeff's mother (Janey) saying, “If you spank him again like this, I will report your child abuse to the police. You were cruel to Jeff and this must not happen again." At this point, Jeff said that he was afraid that his mother might leave, and he would lose her. So Berry added the following: “This child needs a mother and a father. If you don't know how to educate him, consult me."

After that, Jeff started talking to his mother from his hiding place behind Berry. He told her about how he felt when this incident happened to him. He asked her to support his experiences and not scold him. "Mother" was able to respond to his request, and he began to relax and come out from behind Berry. (At this point, Berry realized that Jeff had found an inner protector and no longer needed Berry in that role.)

We asked Jeff if he got what he wanted from the session, and he said yes. He now knew what appropriate anger looked like, and he finally had the support he always dreamed of from his parents. (These were important developmental gaps Jeff needed to protect himself in future situations in which he had previously felt victimized.)

SKILL BUILDING ACTIVITY:

BORDERING EXERCISE

This exercise will teach you how to create optimal boundaries instead of walls. You will also be able to experience what it means to be an interventionist and to be intervened yourself, and define what it means to

| Part II. Ways to intimacy | 289 |

share which role you are most comfortable in. By the end of the exercise, you will be able to raise and lower your boundaries, allowing you to get protection when you need it and intimacy when you want it. When doing the exercise, it is important to be fully aware of what is happening in your body at any given time.

Instruction. This exercise is best done on a pile carpet or other soft surface that you can leave your finger marks on. You will need a partner for this exercise. Each of you should take turns following the guidelines below. Choose a partner, invite him to do this exercise and sit with him on the floor, opposite each other. Determine who will be the first to play the role of the person who has undergone an intervention, and who will be the interventionist. The person undergoing the intervention performs the exercise first. Your partner will play the role of an interventionist. At the end of the exercise, you will switch roles so that everyone can play both roles. In the exercise you will find recommendations for each role.

Step 1: No boundaries

This part of the exercise is designed to give you an idea of what it means to have no protective boundaries. Partners sit opposite each other at a distance of about three feet. Your partner begins to make any aggressive or threatening non-verbal movements towards you.

290 Jane B. Weinhold and Berry C. Weinhold. Escape from proximity

The partner should move towards you slowly and consciously. Pay attention to how you feel when someone approaches you without warning.

How do you feel? What reaction did you notice in your body? What thoughts came to your mind?

Step 2: Boundaries but no protection

By doing this part of the exercise, you will understand the impression that boundaries make. Understanding this will increase your awareness of creating boundaries. This time you know where the boundary is between you and your partner, and you will notice how you feel when someone crosses your boundary without permission.

I. Partner 1. Sitting on the floor, draw a symbolic circle around you. If possible, draw a circle with your finger on the carpet, or use string, magazines, pillows, and other items at hand to mark it. Feel what it means to have a boundary around you.

Partner 2. Feel what it means to be outside the circle and not have a boundary like your partner.

II.Partner 1. Once you have created your boundary (real or imagined), ask a partner outside the boundary to initiate the intervention.