Anxiety procrastination perfectionism

7 Steps to Break the ‘Perfectionism, Procrastination, Paralysis’ Cycle

It’s time to lower the bar. Lower… no, keep going. There.

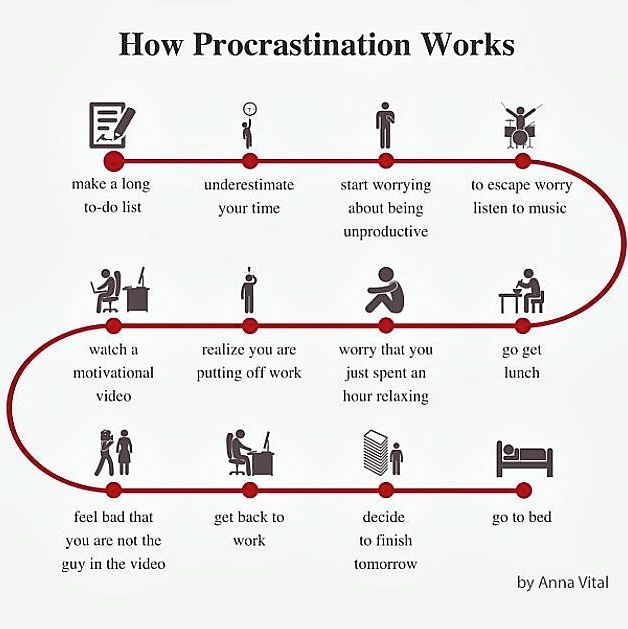

Raise your hand if this sounds familiar: A swirling to-do list in your brain. A list so long that even the simplest task becomes overwhelming and all-consuming.

Even as I sit here writing this article, I’m overwhelmed with the points I want to make and how to phrase them. It leaves me wanting to throw up my hands and deal with it later.

Getting things done or let alone getting organized when you struggle with anxiety can be overwhelming.

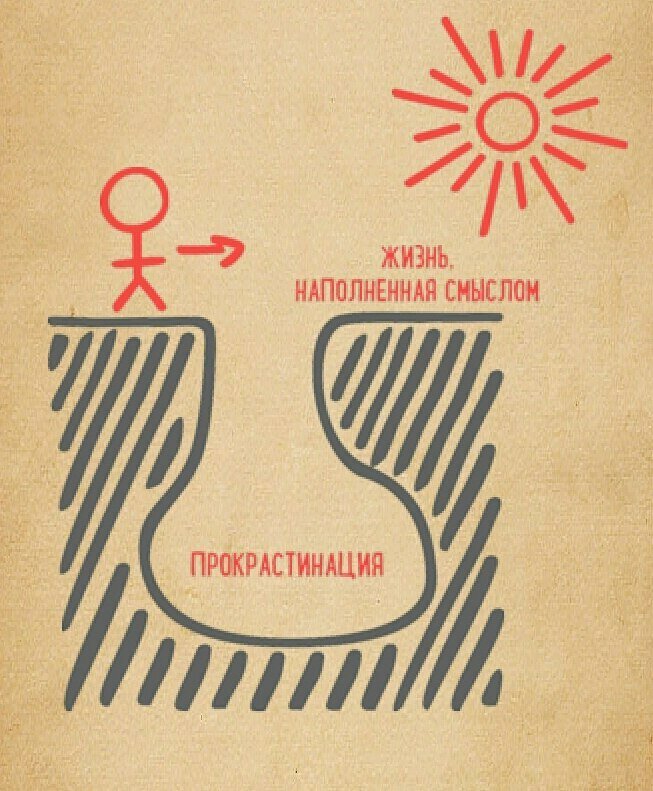

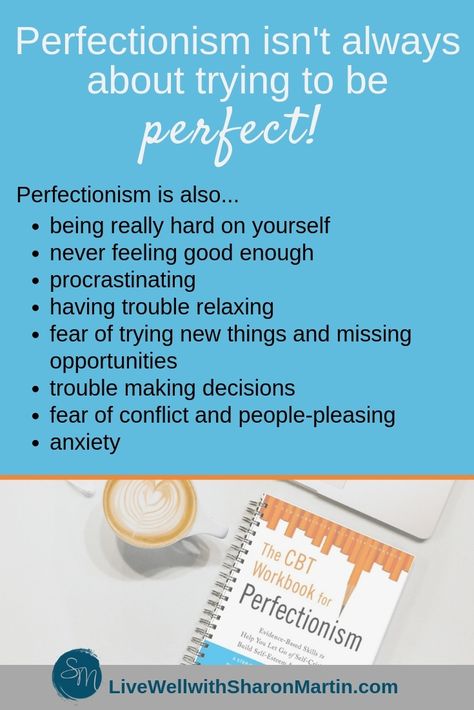

It’s this sense of overwhelm that feeds one of the common patterns that people struggle with: the perfectionism-procrastination-paralysis cycle.

For many people, the idea of doing a task in a less-than-perfect way may be grounds enough to say, “Forget the whole thing!”

Whether that perfectionism stems from a fear of judgment or judgments you have of yourself, the anxiety likes to convince you that if you can’t do everything and do it perfectly? You should probably do nothing at all.

But inevitably, there comes a point when that avoidance has gone on for far too long — and just when it’s time to pull it together? You freeze.

And along comes anxiety’s best friend: shame. Shame wants to constantly remind you that the task didn’t get done, only reinforcing your perfectionism… and perpetuating the cycle.

Getting organized has now become not only a monumental task — it’s now an existential crisis, as you begin to wonder what could be so “wrong” with you that you keep getting stuck.

Am I just lazy? Is my brain broken? Why do I do this to myself? What’s the matter with me?

Rest assured, you’re not alone. And there are very practical ways to overcome anxiety so that this cycle is not only something you can manage, but something you can conquer.

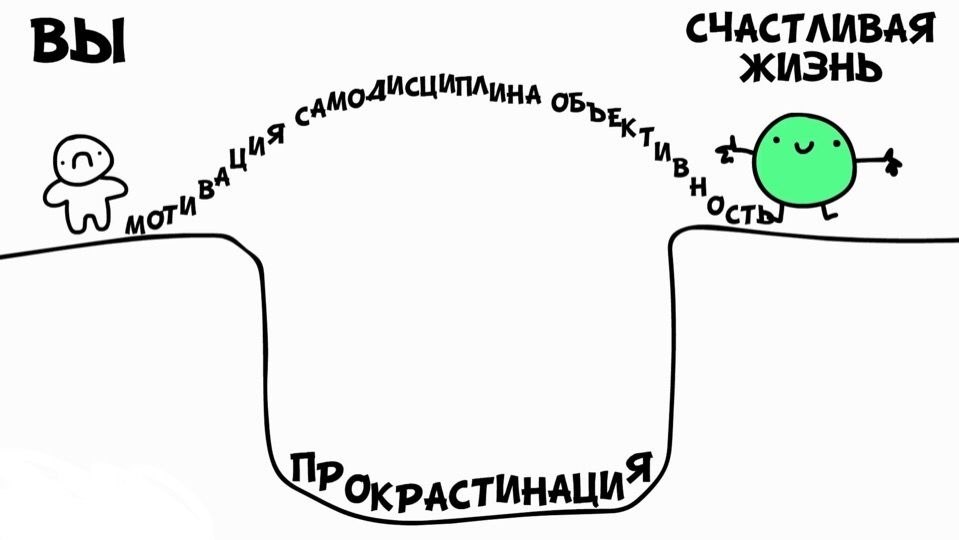

“The good thing about cycles is that they can be reversed in an equally cyclical way,” says Dr. Karen McDowell, clinical director of AR Psychological Services.

“When you tackle perfectionism, you’re less likely to procrastinate,” she says. “When you procrastinate less, you don’t get that sense of panic and paralysis, so your work ends up looking and feeling better than it would have otherwise.”

“When you procrastinate less, you don’t get that sense of panic and paralysis, so your work ends up looking and feeling better than it would have otherwise.”

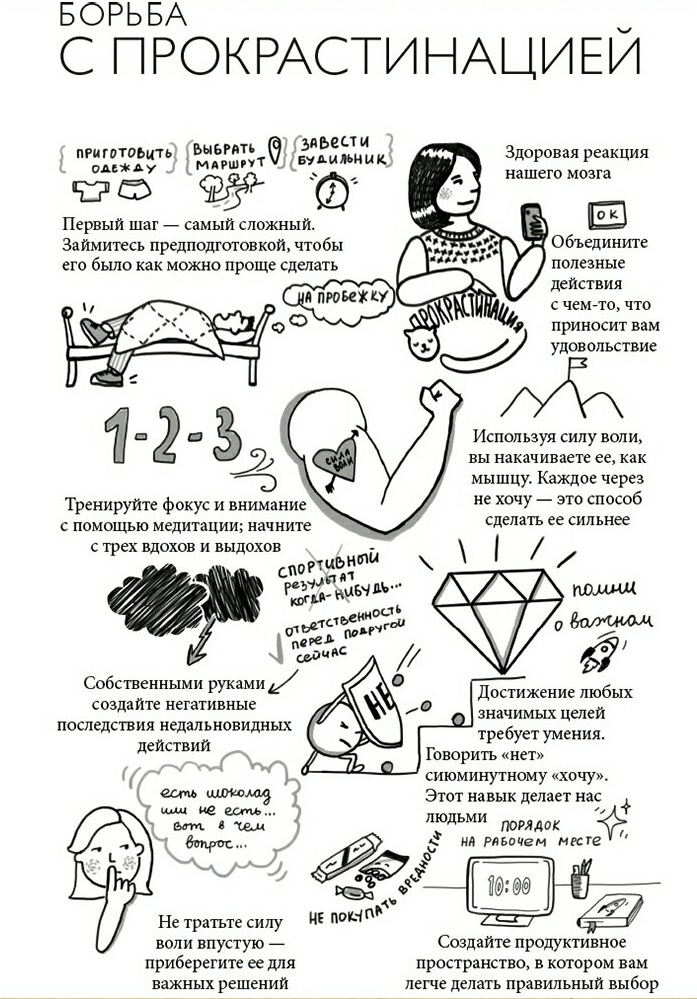

But where to begin? To break the cycle, follow these 7 steps:

The first step to breaking that cycle is to recognize that often times, accomplishing tasks is a slow process, and an imperfect one at that — and that’s normal and totally okay.

It won’t happen all at once. It’s okay to take your time. It’s okay to make mistakes (you can always go back and fix them later!).

In other words, it’s okay to be human.

It’s easy to forget this, though, when so many of the expectations we have of ourselves are lurking just below the surface, fueling our anxiety.

As a writer, it’s my job to write every single day. One of the best pieces of advice someone gave me was, “Remember, not every single piece needs to be a gem.” Meaning, don’t shoot for the Pulitzer Prize with every assignment I have. Nothing would ever get done and I’d wind up challenging my self-worth on a daily basis. How exhausting!

Nothing would ever get done and I’d wind up challenging my self-worth on a daily basis. How exhausting!

Instead, I’ve learned to separate which tasks deserve the bulk of time and attention, and which ones are okay to ease up on. This doesn’t mean accepting laziness! It just means understanding that B-level work is so very far from failure — and a normal part of life.

Before diving into your work, make a conscious decision to lower the bar. Free yourself from the expectation that you have to give 100 percent of yourself to everything you do.

“Tackling perfectionism requires disrupting all-or-nothing thinking,” says Dr. McDowell. “For example, if you’re trying to get your inbox organized, it’s not going to help if you consider that as one single task. Figure out what the components of the task are, and take them in bite sizes.”

Breaking down tasks into their smaller pieces not only makes them more manageable, but leads to more frequent feelings of accomplishment as you cross each one off your list.

Let’s look at it this way: You have to plan your wedding. You might be tempted to write “get flowers” as a task, for example, but that could invoke feelings of overwhelm.

Sometimes the very act of crossing something off a list instills motivation to get more done. This is why no task is too small for your list! It can be as simple as, “Google florists in my area.” Cross it off, feel good about accomplishing something, and repeat the positivity.

Small victories build momentum! So set up your tasks accordingly.

It’s important to remember that when a task is looming over us and we’ve built it up to be a behemoth, we often overestimate the time it takes for us to complete it. When you think an anxiety-inducing task will take the entire day, you also tend to not schedule any time for self-care.

“Balancing priorities is important,” says Dr. Supriya Blair, licensed clinical psychologist. “This is why we include time for social and self-care activities during our daily and weekly schedule. Holding oneself accountable to follow through on work and fun activities takes practice, patience, and self-compassion.”

Holding oneself accountable to follow through on work and fun activities takes practice, patience, and self-compassion.”

Not sure where to start? there’s a technique for that.Tracking time can be made easier by using the ‘Pomodoro’ technique:

- Choose a task you’d like to get done. It doesn’t matter what it is, as long as it’s something that needs your full attention.

- Set the timer for 25 minutes, vowing that you’ll devote 25 minutes (and only 25 minutes) to this task.

- Work until the timer goes off. If another task pops into your head, simply write it down and return to the task at hand.

- Put a checkmark next to your task after the timer goes off (this will help you tally up how much time you’ve spent working on something!).

- Take a short break (a short one, like 5 minutes or so).

- After 4 Pomodoros (2 hours), take a longer break for about 20 or 30 minutes.

Using this method overtime helps you to recognize how much time an activity actually requires, building confidence in your ability to complete your work while also cutting down on interruptions.

It also makes space for self-care by reminding you that you do, in fact, have room in your schedule for it!

Power in numbers! Tackling anything alone is more overwhelming than doing so with a support system.

One of the best ways to get organized when you have anxiety is to partner up with a supportive, hardworking companion, whether it’s your significant other, friend, parent, or child. You can also reach out to a therapist or life coach to get some much-needed perspective.

“You are not alone. There are people out there who can help,” says Briana Mary Ann Hollis, LSW, and owner/administrator of Learning To Be Free.

“Write down what you need support with right now, and next to that write at least one person who can help you with that task,” she says. “This will show you that you don’t have to do everything by yourself.”

“This will show you that you don’t have to do everything by yourself.”

It’s impossible for one person to commit to absolutely everything, but we often feel the need to please everyone.

Taking on too many responsibilities is a sure-fire way to become overwhelmed and to then fall into the similar self-destructive cycle.

“Think about where you can streamline your schedule, delegate to others, or even say no to events and tasks that are not immediate or urgent,” says Angela Ficken, a psychotherapist who specializes in anxiety and OCD.

“The idea is to add some limits into your schedule. Doing this can clear your mind and your time so that you can actually do some activities that bring you joy. It really is OK to say no,” she adds.

How do you know what your limits are? Have you ever heard the expression, “If it’s not a ‘hell yes, then it’s a no”? While there are exceptions to any rule, this is a good template to follow when it comes to taking on responsibilities.

We’re all busy and we all have obligations, so if you don’t have to take on a project or catch up with that acquaintance from college you haven’t spoken to in 14 years, then don’t feel guilty about saying no.

You’re never too old to reward yourself, and often setting up small rewards can be one of the most effective ways to motivate yourself to get organizational tasks done.

“Focus on how you will feel when your home is organized and clean, how exciting and fun it can be to plan your wedding, how responsible you will feel when you complete your taxes,” says Dr. Nancy Irwin, a psychologist with Seasons in Malibu.

“Then reward yourself for a job well done. Positive reinforcement ensures the next project can go as smoothly and informs you that you are bigger than the anxiety,” she says.

Each day, I make a list of the assignments and household tasks I want to accomplish. They’re as mundane as “take out the trash” to important ones like “complete edits” or “submit invoicing. ”

”

No matter the size of the task, after each one I treat myself. I go for a walk, or allow myself to watch 30 minutes of television. When I finish the list I might even have a glass of wine.

It’s giving myself these fun treats to look forward to that breaks up the day, and turns my overwhelming to-do list into something of a game!

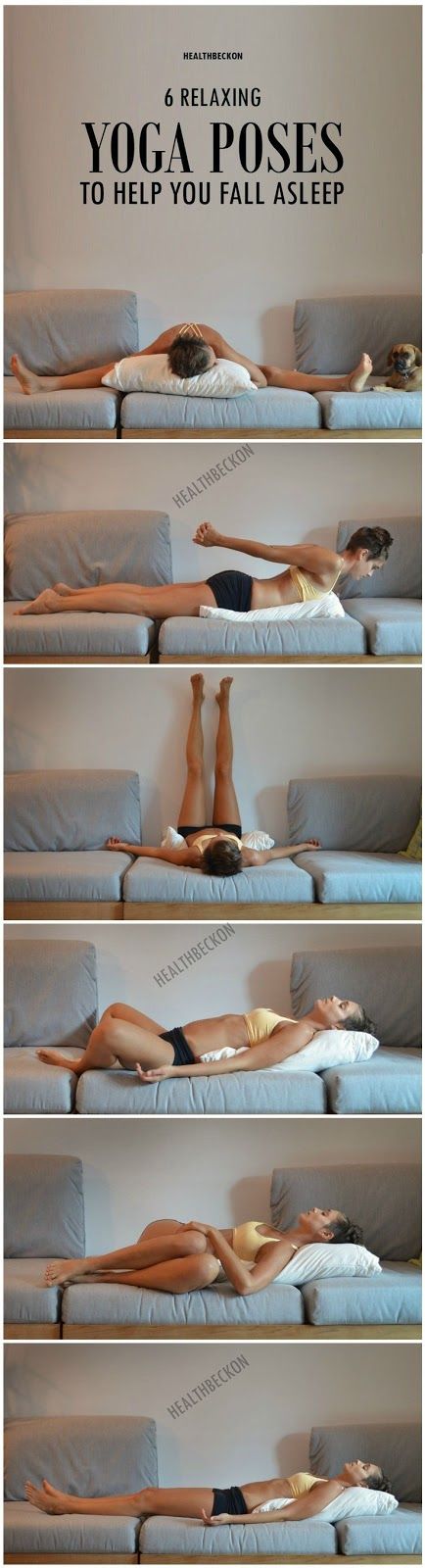

Staying in tune with your body and mindset as you practice breaking patterns can be extremely beneficial.

Self check-ins are critical, especially if you’re prone to honing in on the smallest details. To avoid feeling overwhelmed, it’s important to take a step back to give yourself breaks and reminders.

“Mindfulness is key,” says Ficken. “A relatively easy mindfulness skill is to take yourself outside for a walk or to sit out on your stoop. Being out in the elements can be an easy visual and sensational cue to bring yourself into the present moment.”

Keeping grounded is an important part of keeping your anxiety in check. Don’t hesitate to take a breather when you feel your anxiety building — your body and brain will thank you later!

In fact, anxiety disorders are the most common U. S. mental illness, affecting 40 million adults each year.

S. mental illness, affecting 40 million adults each year.

If your anxiety is building up walls when it comes to organizing your life or day-to-day tasks, rest assured there are millions out there struggling with the same issues.

The good news is that anxiety disorders are highly treatable, and the patterns that keep you in a negative loop are breakable. The first step is deciding that it’s okay to cut yourself some slack.

You’ve got this!

Meagan Drillinger is a travel and wellness writer. Her focus is on making the most out of experiential travel while maintaining a healthy lifestyle. Her writing has appeared in Thrillist, Men’s Health, Travel Weekly, and Time Out New York, among others. Visit her blog or Instagram.

Caught in the Perfectionism-Procrastination Loop? — The Skill Collective

By Olivia Kingsley

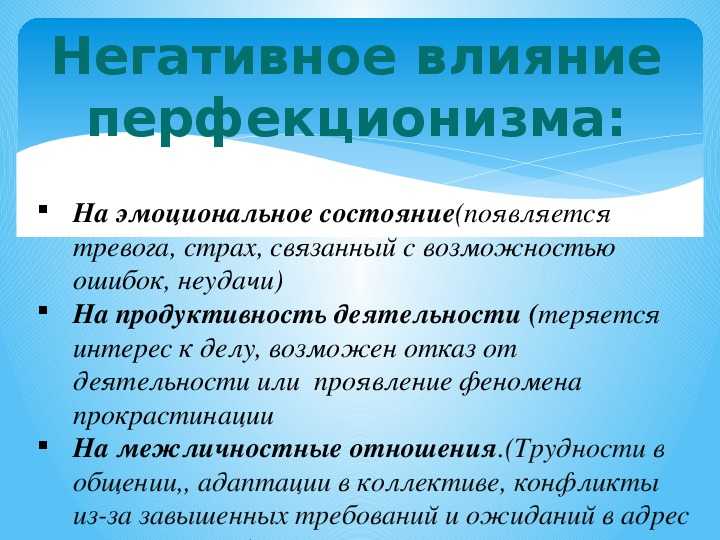

Perfectionism is often viewed as a positive quality – after all, who wouldn’t want to be perfect? High achievers meet their goals, and this can lead to feeling accomplished. However, the dark side of perfectionism, Clinical Perfectionism, can actually harm our wellbeing, mental health, and performance. Clinical Perfectionism involves placing immense pressure on ourselves to meet extremely high (and often unattainable) standards [1], relentlessly striving for these standards, and basing our self-esteem based on the ability to achieve these standards[2]. When we (inevitably) fall short of meeting these standards, we experience negative emotions and low self-worth. Rather than helping us attain excellence, Clinical Perfectionism can actually result in a number of self-defeating behaviours, including procrastination [3]. Let’s look at Mia’s situation:

However, the dark side of perfectionism, Clinical Perfectionism, can actually harm our wellbeing, mental health, and performance. Clinical Perfectionism involves placing immense pressure on ourselves to meet extremely high (and often unattainable) standards [1], relentlessly striving for these standards, and basing our self-esteem based on the ability to achieve these standards[2]. When we (inevitably) fall short of meeting these standards, we experience negative emotions and low self-worth. Rather than helping us attain excellence, Clinical Perfectionism can actually result in a number of self-defeating behaviours, including procrastination [3]. Let’s look at Mia’s situation:

Mia, 22, is a university student who takes her studies very seriously and wants to impress her professors. She holds very high standards for her academic performance and believes that any grade lower than a high distinction is unacceptable. If she receives a grade she considers too low, Mia believes she is a failure and assumes that her professors are disappointed in her. Because of the immense pressure she faces, Mia delays starting assignments because she is terrified of making a mistake when writing the ‘perfect’ paper. This means that Mia starts her assignments at the last minute, which leaves her feeling rushed, guilty, and overwhelmed.

Because of the immense pressure she faces, Mia delays starting assignments because she is terrified of making a mistake when writing the ‘perfect’ paper. This means that Mia starts her assignments at the last minute, which leaves her feeling rushed, guilty, and overwhelmed.

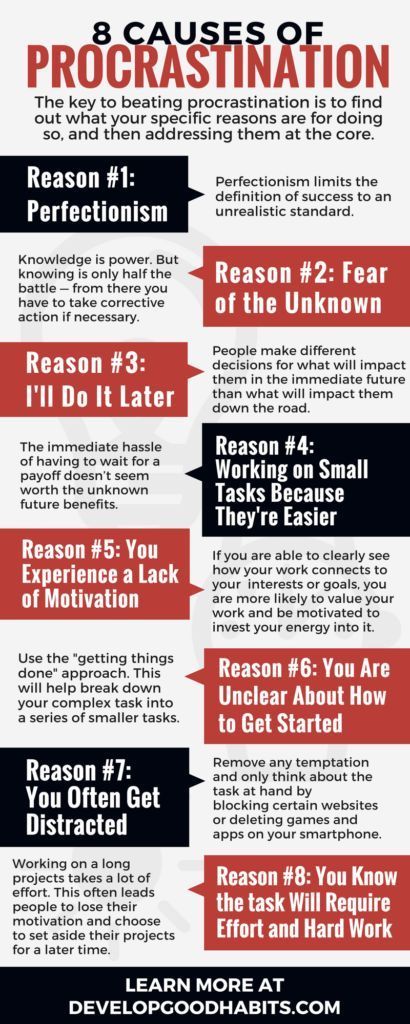

In Mia’s situation, procrastination has nothing to do with being lazy. Rather, her procrastination is directly tied to her fear of not attaining perfection. If this sounds familiar, here are some other signs that perfectionism could be driving procrastination [3]:

The thought of starting a project or assignment is too terrifying because it won’t be good enough.

Excessive amounts of time are spent in the planning phase (the ‘grand vision’), but doing the actual task is put off until the last minute because the output may fall short of the vision.

Actions are heavily driven by emotions, for example avoiding finishing a task until it feels “ just right”, or not starting an assignment because we’re “not in the right frame of mind”.

Easier, less intimidating (and less ego-threatening) tasks are prioritised, taking time away from those tasks that need to be completed.

The challenge, though, is that while procrastination brings short-term relief, it’s later replaced by increased time pressure, feeling even more overwhelmed, and underperformance in general.

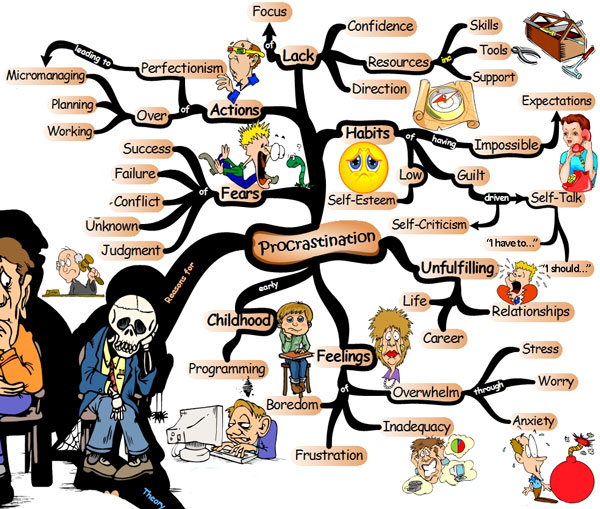

what maintains the perfectionism-procrastination loop?How is this unhelpful perfectionism-procrastination loop maintained? Let’s look to those thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that keep us stuck in this loop.

The way we think

The way perfectionists think can really maintain clinical perfectionism and contribute to procrastination.[3][4]

Perfectionists are often hypervigilant for signs that their performance is not up to scratch. They may be sensitive to signs of negative feedback, or even tune in to their own stress and discomfort when attempting to start a task (and rationalising that this discomfort reflects a lack of ability).

Perfectionists can fall into the trap of unhelpful thinking styles. These thinking styles are often inaccurate but are accepted as reflecting reality. They unhelpful thinking styles serve to increase stress and overwhelm, which can be demotivating. Procrastination is a natural consequence when facing such negative emotions. These kinds of thinking styles include:

All or Nothing Thinking: This particularly relates to the attainment of unrealistically high standards, “If I don’t receive 100% on my test then I am a bad student”. Certainly, attaining these unrealistically high standards is unlikely, thus this way of thinking sets the perfectionist up to experience stress and overwhelm.

Catastrophic Thinking: This involves assuming that one will not be able to cope with negative outcomes, and that even a small mistake will be a disaster. “My reputation would never recover if I said the wrong thing at a work meeting”.

When the consequences are blown out of proportion, is it any wonder that procrastinating on taking action seems to be the safer option?

When the consequences are blown out of proportion, is it any wonder that procrastinating on taking action seems to be the safer option?Mind Reading: This involves predicting what other people are thinking, often making assumptions that they are judging you negatively, “My supervisor is so critical and exacting that they will rip my assignment to shreds and think I am utterly incompetent.” This type of thinking can then lead to procrastination when submitting work to be evaluated.

Misguided attributions and rationalisations following the outcome subsequently serve to reinforce the perfectionism-procrastination loop, for example believing that:

Attributing deadline-driven productivity to capability, “I do my best work under pressure!”. In reality, the work is done only because of the imminent deadline. The rest of the time

Rationalising outcomes as an underestimate of true abilities, thus preserving self-esteem, “Wow, look at that mark.

Pretty remarkable given I didn’t have much time to do it. Imagine if I actually focused I could’ve done so much better!”

Pretty remarkable given I didn’t have much time to do it. Imagine if I actually focused I could’ve done so much better!”

The way we feel

Since perfectionists tend to be highly self-critical, they experience negative emotions when their expectations are (inevitably) not met. The thinking styles described earlier keep perfectionists feeling bad about themselves and reinforce their low self-worth. When a perfectionist is unable to meet their high standards, they may experience feelings of anxiety, overwhelm, guilt, depression, and doubt.

These feelings may be so intense and unbearable that procrastination seems to be the safest and most comfortable option. [4]

The way we behave

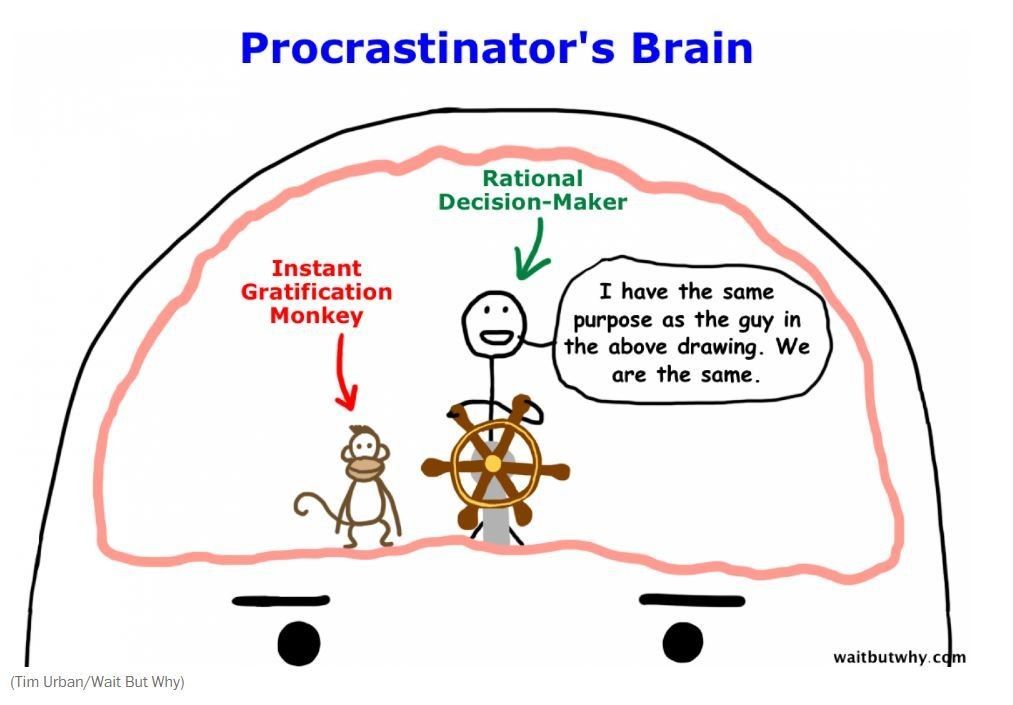

Finally, behaviour plays a big role in maintaining the perfectionism underpinning procrastination. In the article Anxiety on Campus: What Students Need to Know about Managing Anxiety, our Fight or Flight response kicks in when we face a threat (as is the case of a task we see as challenging and demanding perfection). Procrastination is an excellent example of the Flight response, where we seek to avoid the threat of failure and the resulting negative feelings triggered by the task. Some common examples of procrastination behaviours include:

Procrastination is an excellent example of the Flight response, where we seek to avoid the threat of failure and the resulting negative feelings triggered by the task. Some common examples of procrastination behaviours include:

Avoiding making a decision: This may include being unable to choose an assignment topic because you need to pick the “perfect” one that will result in you making the most compelling presentation in order to earn top marks, or even putting off making a decision (in case it’s the incorrect one!) so that you just have to make do with whatever is left over.

Giving up too soon: It is common for perfectionists to give up trying because doing so means facing the possibility of failure. It feels more secure and safe to avoid the scrutiny.

Delaying starting a task: This can include avoiding starting assignments, or even spending an excessive amount of time on researching but not actually starting the assignment (but still feeling productive).

Not committing means not having to deal with a less-than-perfect attempt.

Not committing means not having to deal with a less-than-perfect attempt.

All these procrastinating behaviours are problematic in that they not only increase psychological distress, but also maintain perfectionism. When we engage in procrastination behaviours, we never really learn if we are actually good enough, and our thoughts keep us stuck in the perfectionism-procrastination loop:

If we performed well, we can only imagine how much better we could’ve done if only we’d started earlier and given ourselves a proper chance to shine (that is, our real potential hasn’t been fairly tested!)

If we perform poorly, then we can excuse it because of the pressure you were under (that is, our real potential was crushed under the weight of time pressure or anxiety).

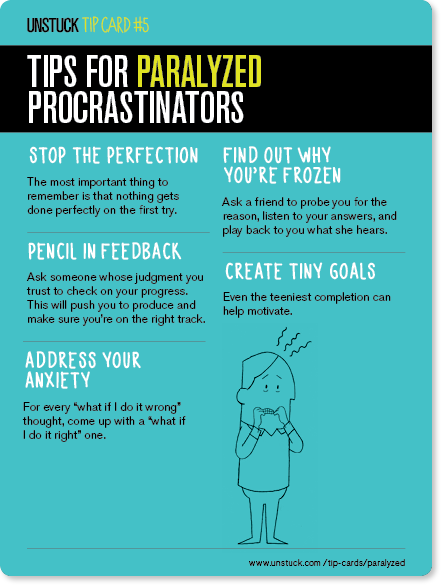

Tips to break the perfectionism-procrastination loop

If you find yourself agreeing to all of the above, help is at hand. Here’s our tip sheet to help you break the perfectionism-procrastination loop [2] . As a sneak peek these include:

Here’s our tip sheet to help you break the perfectionism-procrastination loop [2] . As a sneak peek these include:

Count the costs of procrastination.

Set realistic and achievable goals .

Shift your mindset.

Shift your goalposts.

Show yourself compassion. .

Reach out and talk to a psychologist who works in the perfectionism-procrastination space (like us!).

A word of caution - the perfectionism-procrastination loop often reflects an entrenched pattern of thinking and behaving, accompanied by strong emotions. Progress will take time, and there will be setbacks along the way, so it’s best to adopt the approach of chipping away at it gradually.

You'll also receive news and updates at The Skill Collective. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link in the footer of any newsletter email you receive from us, or by contacting us. For more information please read our Privacy Policy and Terms + Conditions.

You'll also receive news and updates at The Skill Collective. You can unsubscribe at any time by clicking the unsubscribe link in the footer of any newsletter email you receive from us, or by contacting us. For more information please read our Privacy Policy and Terms + Conditions. REFERENCES

[1] Flett, G.L., Hewitt, P.L., Blankstein, K. R. & Koledin, S. (1991). Dimensions of perfectionism and irrational Thinking. Journal of Rational Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 9, 185-201.

[2] Baldwin, M. W., & Sinclair, L. (1996). Self-esteem and "if…then" contingencies of interpersonal acceptance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 1130 - 1141. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1130

[3] Antony, M. M., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). When perfect isn't good enough: Strategies for coping with perfectionism. New Harbinger Publications.

[4] Fursland, A., Raykos, B. and Steele, A. (2009). Perfectionism in Perspective. Perth, Western Australia: Centre for Clinical Interventions

Perth, Western Australia: Centre for Clinical Interventions

[5] Egan, S.J., Wade, T.D., Shafran, R., & Antony, M.M. (2014). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of perfectionism. New York: The Guilford Press.

Perfectionism, procrastination and cognitive distortions

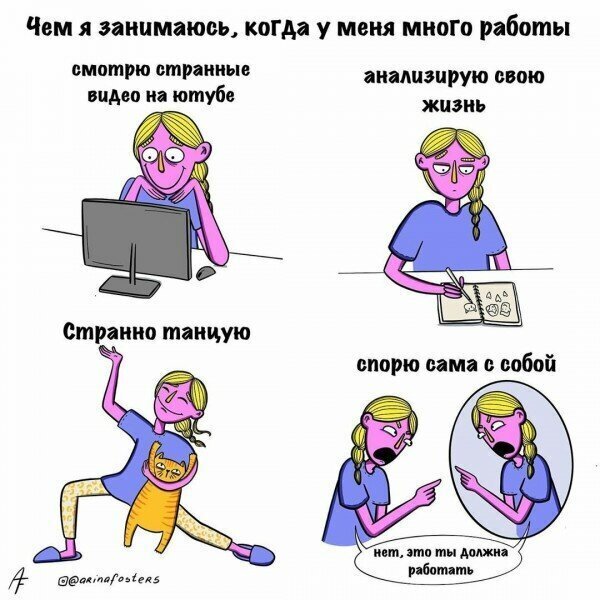

Do you periodically find yourself in situations where deadlines are burning, and you have not even begun to complete the task, you cannot force yourself to do anything and are constantly distracted by unimportant and far from urgent matters?

Scolding yourself, but you still can't get started, end up doing everything on the last day, experiencing distress and working "at the limit", drinking the 7th cup of coffee per day?

Things get put on the back burner, accumulate like a snowball, and you don't know how to approach it, in the end you decide to watch the next episode of a YouTube entertainment show, and then you find yourself sorting through archives of family photos in 2 one o'clock in the morning, when it's time to go to bed and you again didn't have time to do anything?

If any of the above sounds familiar to you, sit back, things can wait a bit, and now we'll talk a little about perfectionism and its accompanying phenomena.

"The first rule of the perfectionist-procrastinator: it's better to do well, but never, than poorly today" (c)

A short digression into history: the concept of “perfectionism” is rooted in the philosophy of Renaissance humanism and Protestant ethics 19th century. In those days, perfectionism was a set of ethical and moral teachings that implied the active participation of the individual will in the processes of improving oneself, society, and the world. In a religious context, this meant developing one's benefactors, self-discipline, and doing good deeds in the hope of earning redemption before God.

There are several theoretical models of perfectionism in modern psychology, and in this article we will focus more on perfectionism as a personality characteristic.

The first researchers of the phenomenon of perfectionism were psychoanalysts, in particular, Karen Horney, who in her works "Our Internal Conflicts" (1945) and "Neurosis and Personal Growth" (1950) considered perfectionism in the context of a narcissistic personality organization, where the "Grand Self" is a way to hide the weak and helpless "Real Self".

According to the definition of Canadian psychologists Hewitt and Flett, creators of the Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale (MPS) methodology, perfectionism is the desire to be perfect, impeccable in everything.

If we try to give a modern general definition of perfectionism, it is such a set of personality traits in which a person sets very high standards for himself in all spheres of life and tries to achieve perfection in most of his activities.

So what's wrong with striving for perfection in everything? - you ask.

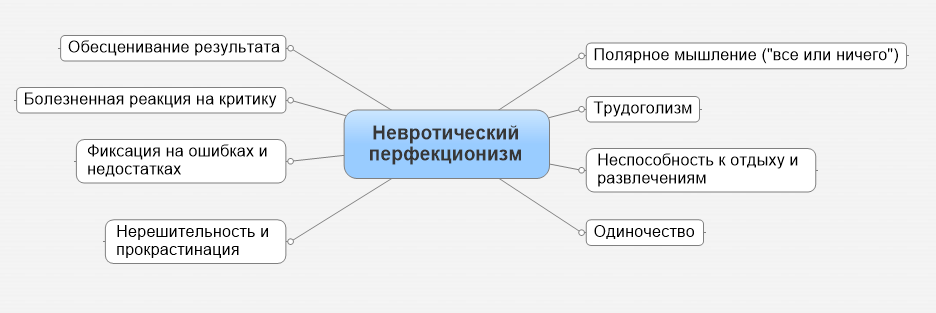

And here the most interesting and non-obvious begins: excessive self-criticism, rigidity of the cognitive sphere, depreciation of the results of one’s work, difficulties in making decisions, focusing on mistakes and failures, perception on the principle of “all or nothing”, procrastination with deadlines missed, obsession with achieving the goal, which often leads to the inability to enjoy the process and much more.

Also, perfectionism as a symptom is found in some personality and mental disorders: for example, according to the DSM-5 classification, perfectionism is included in the triad of main diagnostic criteria for anancaste personality disorder.

According to a 2017 meta-analysis (Limburg, Watson, Hagger, Egan “The relationship between perfectionism and psychopathology”), which included 284 relevant studies, there is a correlation between perfectionism and some mental and personality disorders.

However, it is worth remembering that the mere presence of perfectionism as a personality trait does not indicate that something is wrong with the person. Pathology can be assumed when it prevents a person from living and adapting to new conditions or creates significant inconvenience to the people around him.

Four types of early experiences are described that contribute to the formation of "perfectionist thinking" (Barrow J., Moore C., 1983):

- Overly critical and demanding parents;

- Parental expectations and standards are excessively high, while criticism is not direct, but indirect;

- No parental approval, inconsistent or conditional;

- Perfectionist parents serve as models for teaching perfectionist attitudes and behaviors.

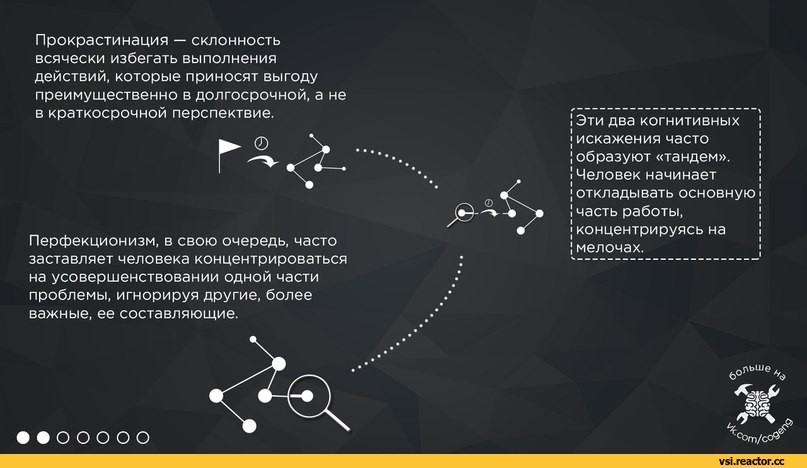

A fairly common maladaptive behavioral strategy that accompanies perfectionism is procrastination.

Procrastination is a tendency to put off even important and urgent things, which in the long run leads to personal and social problems. Even with the obvious disadvantages of such behavior and the awareness of all the consequences, it is usually extremely difficult for people to refuse it.

One of the popular theories of perfectionism, developed by Canadian psychologists Hewitt and Flett, identifies three areas of perfectionism:

- Self-addressed perfectionism is unrealistically high personal standards that a person sets for himself. This component is associated with the tendency to set "remote" and difficult to achieve goals, focusing on them;

- Socially prescribed perfectionism - a person's belief that other people have very high expectations of him, which are very difficult to meet, but necessary to avoid negative evaluation;

- Perfectionism, focused on others and the world as a whole - other people must meet the expectations and high personal standards of a person;

As you might guess, with a significant degree of perfectionism, it is extremely difficult for a person to live in an imperfect world with living people, and even suffer from his own imperfection.

Fun fact: the great Russian painter Ilya Repin was dissatisfied with his works even after they hit the exhibition halls. Once, on the basis of this, he had a conflict with Sergei Tretyakov - Ilya Efimovich came to the gallery while the patron was away and began to correct his paintings. Upon arrival, Sergei Tretyakov was furious and forbade Repin to enter the gallery.

The problems that accompany perfectionism are based on certain cognitive distortions or thinking errors.

Cognitive distortions are systematic errors in information processing that lead to inaccurate judgments, illogical interpretations, and irrational behavior. These are some kind of "bugs" that we got in the process of evolution due to various circumstances. Some of them lead to more effective actions in certain conditions: for example, when the speed of decision-making is more important than its accuracy, while the rest create problems of different levels - from everyday (as mentioned above) to global (all kinds of prejudices and negative stereotypes).

The most common cognitive distortions found in people with pronounced perfectionist traits are overgeneralization, focusing on mistakes, and dichotomous thinking. Below we will look at how dichotomous thinking works with an example.

Black and white (or dichotomous) thinking : almost any phenomenon is evaluated too categorically “all or nothing”, “ideal or disgusting”, “if I don’t become the best in something, there’s nothing to take”, etc.

Example: Egor, a self-employed designer, signed a contract with a customer - the project must be handed over in a month. In his imagination, everything goes smoothly - he makes a chic project, the customer is delighted, after adding this case to the portfolio, there is no end to clients. Everyone is happy. In reality, Yegor starts his work and realizes that everything does not turn out the way he imagined – the work is hard and slow, in parallel he constantly watches training videos and the work of the best designers, discovering with horror for himself a clear inconsistency. Time goes by, but the work hardly moves - Yegor looks for and finds flaws in his technique, along the way being distracted by various nonsense. And then the deadline comes up - Egor understands that he did not have time to show the work in this form is simply terribly embarrassing, so he asks to move the deadline and the next week he works in turbo mode - chronic lack of sleep, self-flagellation, a lot of coffee, nerves at the limit. By some miracle, he manages to hand over the project in a week, and the customer does not even express obvious dissatisfaction. But for himself, Egor knows for sure that his work is simply terrible, and the customer did not notice obvious mistakes, and this time he was just lucky that he was paid at all.

Time goes by, but the work hardly moves - Yegor looks for and finds flaws in his technique, along the way being distracted by various nonsense. And then the deadline comes up - Egor understands that he did not have time to show the work in this form is simply terribly embarrassing, so he asks to move the deadline and the next week he works in turbo mode - chronic lack of sleep, self-flagellation, a lot of coffee, nerves at the limit. By some miracle, he manages to hand over the project in a week, and the customer does not even express obvious dissatisfaction. But for himself, Egor knows for sure that his work is simply terrible, and the customer did not notice obvious mistakes, and this time he was just lucky that he was paid at all.

Result: A feeling of incredible relief and pleasure, a positive reinforcement of the strategy of behavior, Yegor has a headache, but his conscience is relatively clear. In the future, Egor will fall into many similar situations, periodically breaking the agreed deadlines, and sometimes even completely “disappearing from the radar”, leaving the customer at a loss, and himself with a sense of guilt and thoughts about his own worthlessness.

In cognitive behavioral therapy, to work with dichotomous thinking, the cognitive continuum scale is used as one of the methods. Thus, in the process of therapy, a person learns to see more than two options for evaluating his activity, the level of anxiety and general tension during work decreases, the habit of focusing attention only on the final goal is replaced by a more adaptive one - the ability to pay attention to the intermediate results of one's work without resorting to depreciation.

In the long term of working with maladaptive perfectionism, the goals for therapy are often: working with cognitive distortions, working with self-esteem, developing adaptive thinking and behavior strategies, teaching planning skills, teaching maidfulness techniques, etc. A .IN. Pushkin;

“Theoretical models for studying personality perfectionism in foreign psychology” OI Kononenko;

"Cognitive-behavioral therapy of clinical (maladaptive) perfectionism" V. Karavaev;

Arpin-Cribbie, C. , Irvine, J., & Ritvo, P. (2012). Webbased cognitive behavioral therapy for perfectionism: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 22, 194-207. Barrow J., Moore C. Group interventions with perfectionistic thinking // Personell and Guidance Journal. 1983. V. 61. R. 612-615.

, Irvine, J., & Ritvo, P. (2012). Webbased cognitive behavioral therapy for perfectionism: A randomized controlled trial. Psychotherapy Research, 22, 194-207. Barrow J., Moore C. Group interventions with perfectionistic thinking // Personell and Guidance Journal. 1983. V. 61. R. 612-615.

Blankstein K., Flett G., Hewitt P., Eng A. Self-reported fears of perfectionists: an examination with the fear survey schedule // Personality and Individual Differences. 1993. V. 15. R. 323-328.

Bouchard C., Rheame J., Ladouceur R. Responsibility and perfectionism in OCD: an experimental study // Behavior Research and Therapy. 1999. V. 37. No. 3. R. 239-248.

Flett G., Hewitt P., Blankstein K., O’Brien S. Perfectionism and learned re-resourcefulness in depression and self-esteem // Personality and Individual differences. 1991. V. 12. No. 2. R. 61-68.

Flett G., Hewitt P., De Rosa. Dimensions of perfectionism, psychological adjustment, and social scills // Personality and Individual Differences. 1996. V. 20. No. 3. P. 143-150.

1996. V. 20. No. 3. P. 143-150.

Flett G., Hewitt P., Garshowitz M., Martin T. Personality, negative social interactions, and depressive symptoms // Canadian J-l of Behavioral Science. V. 29. No. 1. P. 28-37.

Hamachek D. Psychodynamics of normal and neurotic perfectionism // Psychology. 1978. V. 15. R. 27-33.

Fear and perfectionism: what makes us procrastinate and how to deal with it

In order to stop procrastinating, you need to stop waiting for inspiration and motivation and start taking action - inspiration will come later, says Stanford psychiatry professor David Burns. We tell you why the cause of procrastination, as a rule, is not laziness at all, but unrealistic standards that we set for ourselves

David Burns - one of America's leading psychiatrists, honorary a Associate Professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University School of Medicine and author of several bestselling psychology books such as Mood Therapy and Anxiety Therapy. He also invented and patented his own scale for the diagnosis and evaluation of depression Burns Depression Checklist. Burns is one of the founders of cognitive therapy and in his books talks about how, using its principles, get rid of depression and anxiety and increase self-esteem.

He also invented and patented his own scale for the diagnosis and evaluation of depression Burns Depression Checklist. Burns is one of the founders of cognitive therapy and in his books talks about how, using its principles, get rid of depression and anxiety and increase self-esteem.

In the book Good Mood. Depression and Anxiety Handbook (Due December from Alpina Publisher) Burns offers specific techniques and exercises for everything from dealing with depression and phobias to strengthening relationships and overcoming procrastination. Forbes publishes an excerpt.

“Sometimes, in order to increase vitality, it is enough just to become more active. However, with anxiety or depression, many people procrastinate because they are literally paralyzed by their condition. Some of the causes of procrastination are internal, related to your own thoughts and attitudes, while others are based on your relationships with people. Different categories may overlap with each other, so don't be surprised if you recognize yourself in several of them."

Different categories may overlap with each other, so don't be surprised if you recognize yourself in several of them."

The cart before the horse

“Which do you think comes first, motivation or productive action? If you answered that motivation, do not worry. This is what many procrastinators think. This is a good option, but wrong.

Procrastinators say to themselves: “I don't want something. I'll wait until the mood comes." The trouble is that if you wait until the "mood comes", you can sit idly by for ages. Do you really think that the mood can come to tend the lawn, take the trash out of the garage or deal with the bills? These are boring and unpleasant things, what kind of “mood” can we talk about?

People who have achieved great success will confirm that motivation is not primary, but productive action. To start the engine, you need to turn the key. As soon as you start a task (whether you want it or don't want it), it will spur you on to complete others.

To start the engine, you need to turn the key. As soon as you start a task (whether you want it or don't want it), it will spur you on to complete others.

When I'm preparing for a lecture or a seminar, I often notice that the closer the event is, the more frightening I am. “I wish I didn’t get involved in this,” I think. On the eve, fear paralyzes me, I want to get sick in order to cancel the event under a plausible pretext. I have absolutely nothing to say! It is horrifying to think that I will be standing in front of a hundred psychologists and psychiatrists, talking about something for several hours.

But as soon as I start talking, the sensations change. I notice kind smiles, open faces. A lot of people seem to be really interested in what I'm saying. When people start asking me questions, my enthusiasm grows. At the end, I am terribly tired, but I can not wait to conduct the next event.

The same principle applies to any business you put off. Once you start it, it will most likely seem much less terrible than you imagined, and you will want to complete it successfully.

The idea is simple: the more you do, the more you want more, but you have to start by doing something.”

Related material

Mastery Model

“People who procrastinate often have a somewhat unrealistic idea of how productive people work. You may think that successful people always feel confident and easily achieve their goals without getting frustrated, doubted, or faced with setbacks. This is a “model of mastery” - you think that everything in the world should be your way, but it doesn’t happen. Achieving goals is always stressful. As a rule, along this path, fraught with numerous obstacles, both mistakes and failures occur. If you feel like life is supposed to be easy and that others don't have to suffer, then when faced with difficulties, you may decide that something is "wrong" with you and give up. Your frustration tolerance threshold will be so low that any disappointment will become unbearable.

Achieving goals is always stressful. As a rule, along this path, fraught with numerous obstacles, both mistakes and failures occur. If you feel like life is supposed to be easy and that others don't have to suffer, then when faced with difficulties, you may decide that something is "wrong" with you and give up. Your frustration tolerance threshold will be so low that any disappointment will become unbearable.

Highly productive people tend to follow the "overcoming model" when trying to succeed. They come from the fact that life is full of disappointments, so many failures and defeats are natural. When faced with obstacles, they take them for granted and do not back down. They fall, but rise and go forward with the same determination and dedication.

My daughter, Signy, didn't do very well in chemistry in high school and barely made it to pass grades. She read each chapter of the textbook once, but did not sit over it for a long time in order to properly absorb the material. Each time, Signy got upset because she didn't understand anything. As a result, she completely abandoned the textbook and opened it only on the eve of the exam. Her problem was the "mastery model". Signy was sure that the material should be light.

She read each chapter of the textbook once, but did not sit over it for a long time in order to properly absorb the material. Each time, Signy got upset because she didn't understand anything. As a result, she completely abandoned the textbook and opened it only on the eve of the exam. Her problem was the "mastery model". Signy was sure that the material should be light.

I explained to her that it is often difficult for me to learn something new, so I just spend more time and energy on it. At first she brushed it off and thought I was just saying it out of politeness. But I showed her a chapter from a statistics textbook that I had been working on for over a year, but didn't fully understand. She herself saw how frayed and scribbled the pages of the book were. I told her that I was not at all upset by slow progress: each time I understand the material a little better and I am proud that I try to master it on my own. Admitting that I was right, Signy began to think of chemistry as a challenge rather than an enemy. Her mood has improved and learning has become easier.”

Her mood has improved and learning has become easier.”

Related material

Fear of failure

“While we often think of procrastinators as 'lazy' and 'irresponsible' people, sometimes their real problem is quite different - success is too important to them. They do nothing because there is always the risk of failure.

In people who are afraid of failure, self-esteem is often based on achievement. If they fail to do their job, they may feel like a failure in everything. Because of this, there is a fear of error - the stake is too high.

Consider one example. Ted purchased a small but fairly well-known chocolate company near Chicago. Although her affairs were bad, she could grow and prosper - if he made some effort. However, Ted didn't seem to care about business. In the morning he did not go to the office, but stayed at home or went to do some trifles. Ted confessed to me that he was terribly afraid of failing. For the first time in his life, he owned his own company - before that, he had always worked for large corporations. In one session, I decided to explore his fear of failure.

However, Ted didn't seem to care about business. In the morning he did not go to the office, but stayed at home or went to do some trifles. Ted confessed to me that he was terribly afraid of failing. For the first time in his life, he owned his own company - before that, he had always worked for large corporations. In one session, I decided to explore his fear of failure.

David: Suppose you try and fail. What will it mean to you?

Ted: The last corporation I worked for went bankrupt, but I didn't care - I'm not the owner. I have always felt that I am doing a good job for the company. But, if I fail my own business, I will perceive this failure as personal.

David: And why would that upset you?

Ted: That would mean I'm a loser.

David: Let's say you're a loser. What does this mean to you?

Ted: Well, people will know that I'm a loser.

David: And then what?

Ted: They will stop loving me.

David: Who would stop loving you?

Ted: My wife and kids... my son. My son works with me. Maybe he would stop respecting me.

This short conversation showed us both that Ted feels he must earn the love of those he cares about. I suggested that he test this mindset using the Biggest Fear technique. I suggested that he role-play a dialogue, imagining a situation that his company went bankrupt. I will play the role of his son, but I will be much more hostile than it could be in reality. And Ted had to play himself. Here's how the dialogue developed.

I will play the role of his son, but I will be much more hostile than it could be in reality. And Ted had to play himself. Here's how the dialogue developed.

Son: Hello dad, how are you?

Father: Not really, son. I'm afraid we'll have to file for bankruptcy. We won't be able to pay our bills.

Son: Bankruptcy? Are you saying the company is going down? Are we losing our home? How could you do this to us?

Father: The company is going down and we may have to move.

Son: Wow, you screwed everything up! I have to go to college, and you let me down just when I needed your help with money the most.

Father: You will have to work and help too. We can do it, but we need to unite, we are family.

We can do it, but we need to unite, we are family.

Son: Come on, father! A nightmare!

Father: I understand your feelings. But why do you think it's a nightmare?

Son: Other fathers don't have such problems. Everyone is doing well. Why couldn't you? What will people think of us?

Father: I'm more interested in what you think of me. You seem to be angry.

Son: That's right, I'm angry! And what did you expect? It turns out that my father is a loser!

Father: It seems that in order for you to love and respect me, I need to be successful and earn a lot of money. Am I understanding you correctly?

So Ted faced - in his imagination - his worst fear. He feared failure and rejection from an early age, but he never really experienced it. Instead of being frightened or upset, he began to laugh - and I along with him. His fear was so ridiculous! And then it dawned on Ted that his fears were based on a few distorted thoughts. First, he exaggerated the financial consequences of this collapse. After all, he had other investments, so even if the company went bankrupt, his family would not go around the world. Secondly, he tried to read other people's minds. Most likely, the wife and son would not have reacted violently to his failure, and even more so would not have rejected him: on the contrary, the family would have rallied in the face of adversity. Finally - and this is the most important thing - he realized that he was "personalizing" the rejection of his son. If someone had abandoned him because of bad luck, it would not characterize Ted at all. It was a real revelation for him. Ted was immediately relieved. A week later, he reported that his depression had disappeared and he was happy to work in his new company.

He feared failure and rejection from an early age, but he never really experienced it. Instead of being frightened or upset, he began to laugh - and I along with him. His fear was so ridiculous! And then it dawned on Ted that his fears were based on a few distorted thoughts. First, he exaggerated the financial consequences of this collapse. After all, he had other investments, so even if the company went bankrupt, his family would not go around the world. Secondly, he tried to read other people's minds. Most likely, the wife and son would not have reacted violently to his failure, and even more so would not have rejected him: on the contrary, the family would have rallied in the face of adversity. Finally - and this is the most important thing - he realized that he was "personalizing" the rejection of his son. If someone had abandoned him because of bad luck, it would not characterize Ted at all. It was a real revelation for him. Ted was immediately relieved. A week later, he reported that his depression had disappeared and he was happy to work in his new company.

Related material

Perfectionism

“Finding a publisher for my first book, Mood Therapy, was a daunting task. I was an aspiring author, and no one was interested in a book on self-help for depression. In addition, the manuscript was rather boring and lengthy. In the end, I found a publisher and editor - Maria Guarnaskelli: I liked her very much. When I arrived in New York to sign the contract, we discussed how the manuscript should be revised. Maria showed what needs to be changed to make the text sound more lively. According to her, the book had every chance of becoming a bestseller.

I went home with the advance in my pocket. I had never held so much money in my hands, and the editor's praises continued to sound in my head. I should have felt in seventh heaven with happiness, but for some reason I was discouraged. When I got home, I sat down at the table ... and sat like that for 10 days, looking into space. I just couldn't handle editing. I couldn't think of a single good idea! At the same time, I felt physically exhausted, I could not run even half a block without shortness of breath, although everything was in order with my health. I knew I was upset, but I couldn't figure out what was bothering me.

When I got home, I sat down at the table ... and sat like that for 10 days, looking into space. I just couldn't handle editing. I couldn't think of a single good idea! At the same time, I felt physically exhausted, I could not run even half a block without shortness of breath, although everything was in order with my health. I knew I was upset, but I couldn't figure out what was bothering me.

Finally I took out a piece of paper and wrote down my negative thoughts. The first was: “This book should be a bestseller. But I'm a psychiatrist, not a writer, I don't know how to write bestsellers. I will disappoint Mary." Having formulated this thought, I felt a huge relief and decided to reason differently: “Writing bestsellers is not my job. But I can write a useful book - in the same style that I use in working with patients. This is easy for me, and I am only responsible for this. And how well the book will sell is the responsibility of the publisher.