Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorder dsm

What It Is & What It Diagnoses

What is the DSM-5?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, often known as the “DSM,” is a reference book on mental health and brain-related conditions and disorders. The American Psychiatric Association (APA) is responsible for the writing, editing, reviewing and publishing of this book.

The number “5” attached to the name of the DSM refers to the fifth — and most recent — edition of this book. The DSM-5®’s original release date was in May 2013. The APA released a revised version of the fifth edition in March 2022. That version is known as the DSM-5-TR™, with TR meaning “text revision.”

IMPORTANT: The DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR are medical reference books intended for experts and professionals. The content in these books is very technical, though people who aren’t medical professionals may still find it interesting or educational. However, you shouldn’t use either of these books as a substitute for seeing a trained, qualified mental health or medical provider.

Additionally, the APA also publishes books that supplement the content in the DSM-5-TR. Examples of these supplement publications include the DSM-5 Handbook of Differential Diagnosis and DSM-5 Clinical Cases.

What is the purpose of the DSM-5?

The first step in treating any health condition — physical or mental — is accurately diagnosing the condition. That’s where the DSM-5 comes in. It provides clear, highly detailed definitions of mental health and brain-related conditions. It also provides details and examples of the signs and symptoms of those conditions.

In addition to defining and explaining conditions, the DSM-5 organizes those conditions into groups. That makes it easier for healthcare providers to accurately diagnose conditions and tell them apart from conditions with similar signs and symptoms.

How was the DSM-5 content created?

To create the DSM-5, the APA gathered more than 160 mental healthcare professionals from around the world, including psychiatrists, psychologists and experts from many other professional fields. Hundreds of other professionals contributed and assisted as advisers on specific topics. The creation of the DSM-5 also involved field trials and tests.

Hundreds of other professionals contributed and assisted as advisers on specific topics. The creation of the DSM-5 also involved field trials and tests.

For the DSM-5-TR, the APA called on many of those involved in the initial DSM-5 release. In all, more than 200 professionals directly contributed to the DSM-5-TR.

What topics does the DSM-5 cover?

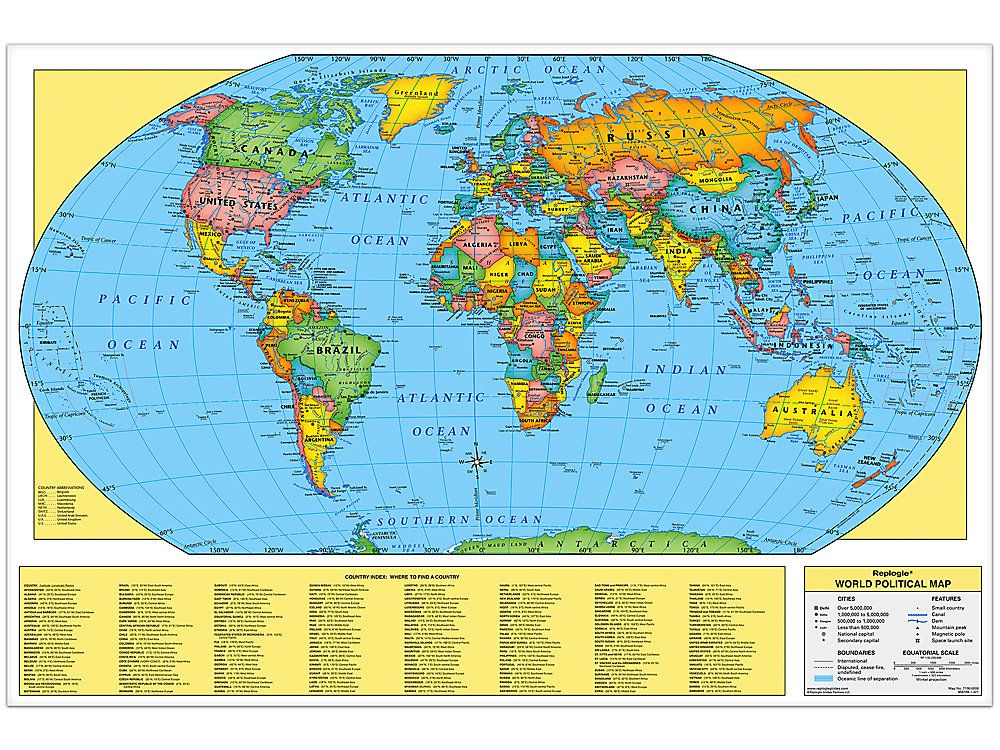

The DSM-5 mainly focuses on mental health conditions. However, because mental health and brain function are inseparable, the DSM-5 also covers conditions and concerns related to how the brain works. The book also contains diagnostic codes, which make it easier for healthcare providers to cross-reference conditions against the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th Edition (ICD-10).

The DSM-5 has three sections:

- Section I: DSM-5 Basics

. This section covers how medical professionals should use the book in their work.

It also includes guidance on using the DSM-5 when mental health concerns involve legal professionals, court cases, etc.

It also includes guidance on using the DSM-5 when mental health concerns involve legal professionals, court cases, etc. - Section II: Diagnostic Criteria and Codes. This section is the largest in the book. Each chapter covers a type of condition, with the specific conditions defined and explained within (see the table below for more about this section).

- Section III: Emerging Measures and Models. This section contains information about specific assessment tools, which providers use as guidelines for diagnosing some conditions. It also has information about how cultural differences may affect a diagnosis, and a chapter about conditions that may eventually go into a later edition of the DSM but need further study before that happens.

More about Section II and the types of conditions it covers

The types of conditions that can be found in the DSM-5 include:

| Section title | Examples of disorders in that section |

|---|---|

| Neurodevelopmental Disorders | Autism spectrum disorder. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Learning disorders (which covers dyslexia, dyscalculia, etc.). |

| Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders | Schizophrenia. Schizoaffective disorder. Delusional disorder. |

| Bipolar and Related Disorders | Bipolar I and bipolar II disorders. Cyclothymic disorder. |

| Depressive Disorders | Major depressive disorder. Persistent depressive disorder. |

| Anxiety Disorders | Generalized anxiety disorder. Social anxiety disorder. Separation anxiety disorder. Panic disorder. Phobias. |

| Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders | Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD). Hoarding disorder. Body dysmorphic disorder. Skin-picking disorder and hair-pulling disorder. |

| Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders | Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Acute stress disorder.

Adjustment disorder. |

| Dissociative Disorders | Dissociative identity disorder. Dissociative amnesia. Depersonalization/derealization disorder. |

| Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders | Somatic symptom disorder. Illness anxiety disorder. Functional neurological symptom disorder (conversion disorder). |

| Feeding and Eating Disorders | Anorexia nervosa. Bulimia nervosa. Binge-eating disorder. Pica. |

| Elimination Disorders | Enuresis (a group of disorders that includes bedwetting). |

| Sleep-Wake Disorders | Insomnia disorder. Narcolepsy. Sleep apnea disorders. Nightmare disorder. Restless legs syndrome. |

| Sexual Dysfunctions | Sexual dysfunctions. |

| Gender Dysphoria | Gender dysphoria-related disorders. |

| Disruptive, Impulse-Control and Conduct Disorders | Oppositional defiant disorder. Antisocial personality disorder. Kleptomania. Pyromania. |

| Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders | Alcohol use disorder. Inhalant use disorder. Opioid use disorder. Withdrawal-related symptoms. |

| Neurocognitive Disorders | Delirium. Alzheimer’s disease. Parkinson’s disease. Huntington’s disease. Traumatic brain injury. |

| Personality Disorders | Borderline personality disorder (BPD). Narcissistic personality disorder. |

| Paraphilic Disorders | Sexual behavior disorders. |

| Other Mental Disorders and Additional Codes | Conditions that don’t match the definition of another condition, but that still significantly affect someone’s life. |

| Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication | Tardive dyskinesia. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. |

| Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention | These include circumstances or behaviors that aren’t conditions, but that may affect or happen in relation to diagnosable conditions. Examples include self-harm and suicidal behaviors, a history of any type of abuse, unemployment, etc. Examples include self-harm and suicidal behaviors, a history of any type of abuse, unemployment, etc. |

When will the APA publish the next edition of the DSM?

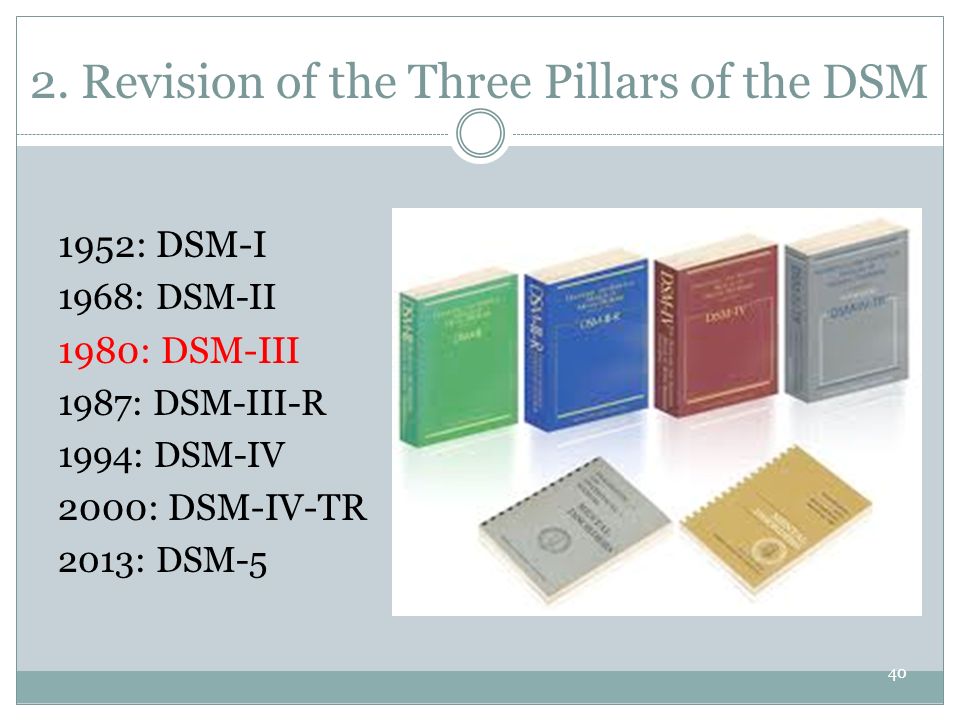

The APA doesn’t publish editions of the DSM on a regular schedule. Instead, they update the DSM as necessary. The APA published past editions of the DSM (which used Roman numerals before the fifth edition) in the following years:

- DSM-I®: 1952.

- DSM-II®: 1968.

- DSM-III®: 1980. The APA published a revised version, the DSM-III-R®, in 1987.

- DSM-IV®: 1994. The APA published a text revision version, the DSM-IV-TR®, in 2000.

- DSM-5: 2013. The APA published a text revision version, the DSM-5-TR, in 2022.

Is DSM-5 available to the public?

Yes. The DSM-5 is available for purchase in many bookstores and online stores. Many public libraries also have a copy (your local library may restrict this book to in-library use only, meaning you can’t check it out).

While the DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR are available to the public in multiple ways, it’s important to remember that the intended users of this book are medical professionals. As a result, the content in this book is extremely technical. That means the average person will probably find this book difficult to understand.

You shouldn’t use the DSM-5 or DSM-5-TR as a substitute for seeing a medical or mental health professional. It’s best to look at the DSM-5 and DSM-5-TR like you’d look at a book about how to fly a plane. You might find it interesting to read that book, but that’s no substitute for the formal education and training required to become a pilot.

Is DSM-5 still used?

Yes, but there are two variants of this book. The APA published the DSM-5 in 2013. In 2022, the APA published a text revision version, the DSM-5-TR. This text revision version includes updates and changes to the DSM-5 that reflect changes and updates in mental health practice since 2013. That makes the DSM-5-TR the preferred version, as it’s the most current and accurate version of this resource.

Among mental health providers, especially psychiatrists and psychologists, the DSM-5-TR is the most important resource for diagnosing mental health- and brain-related conditions. While it’s a publication of a United States-based organization, the DSM-5 is also an essential resource for providers worldwide, with translations into more than 18 languages available.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

The DSM-5 and its revised version, the DSM-5-TR, are key resource books for mental health professionals. This book is widely available for purchase, and many libraries may also make it available to their patrons. This book is intended for medical and mental health professionals, which is why it’s extremely detailed and very technical.

While the average person might find it interesting or informative, it’s not meant for casual use or self-diagnosis. If you think you or a loved one might have a condition defined in the DSM-5 or DSM-5-TR, you or your loved one should see a healthcare or mental health provider. Just like you wouldn’t perform surgery on yourself, it’s best to seek care from a trained, qualified mental health provider.

Just like you wouldn’t perform surgery on yourself, it’s best to seek care from a trained, qualified mental health provider.

Symptoms, Tests, Causes & Treatments

Overview

Social anxiety disorder (formerly known as social phobia) is a mental health condition where you experience intense and ongoing fear of being judged negatively and/or watched by others.

Social anxiety disorder is a common anxiety disorder.

If you have social anxiety disorder, you have anxiety or fear in specific or all social situations, including:

- Meeting new people.

- Performing in front of people.

- Taking or making phone calls.

- Using public restrooms.

- Asking for help in a restaurant, store or other public place.

- Dating.

- Answering a question in front of people.

- Eating in front of people.

- Participating in an interview.

A core feature of social anxiety disorder is that you’re afraid of being judged, rejected and/or humiliated.

Social anxiety disorder is a common mental health condition that can affect anyone. Most people who have social anxiety disorder experience symptoms before they’re 20 years old. Women and people designated female at birth (DFAB) experience higher rates of social anxiety than men or people designated male at birth (DMAB).

Social anxiety disorder isn’t uncommon. Approximately 5% to 10% of people across the world have social anxiety disorder. It’s the third most common mental health condition behind substance use disorder and depression.

A person with social anxiety disorder can have a mild, moderate or extreme form of it. Some people with social anxiety only experience symptoms with one type of situation, like eating in front of others or performing in front of others, while other people with social anxiety experience symptoms in several or all forms of social interaction. In general, the different levels of social anxiety include:

- Mild social anxiety: A person with mild social anxiety may experience the physical and psychological symptoms of social anxiety but still participate in, or endure, social situations.

They may also only experience symptoms in certain social situations.

They may also only experience symptoms in certain social situations. - Moderate social anxiety: A person with mild social anxiety may experience physical and psychological symptoms of social anxiety but still participate in some social situations while avoiding other types of social situations.

- Extreme social anxiety: A person with extreme social anxiety may experience more intense symptoms of social anxiety, such as a panic attack, in social situations. Because of this, people with extreme social anxiety usually avoid social situations at all costs. A person with extreme social anxiety likely has symptoms in all or many types of social situations.

It’s very common to have anticipatory anxiety when facing these situations. It’s possible to fluctuate between different levels of social anxiety throughout your life. No matter which type of social anxiety you have, it’s important to seek treatment because this type of anxiety affects your quality of life.

Anyone can experience shyness from time to time. Having social anxiety disorder consistently interferes with or prevents you from doing everyday activities such as going to the grocery store or talking to other people. Because of this, social anxiety disorder can negatively affect your education, career and personal relationships. Being shy from time to time doesn’t affect these things.

In general, the three main factors that distinguish social anxiety from shyness are:

- How much it interferes with your day-to-day life.

- How intense your fear and anxiety are.

- How much you avoid certain situations.

Many people with social anxiety disorder don’t try to get help or seek treatment because they think social anxiety is just part of their personality. It’s important to reach out to your healthcare professional if you’re experiencing ongoing and intense symptoms when in social situations.

Symptoms and Causes

Researchers and healthcare professionals are still trying to figure out the cause of social anxiety disorder. Social anxiety disorder can sometimes run in families, but researchers aren’t sure why some family members get it and others don’t. Many parts of your brain are involved with fear and anxiety, so social anxiety disorder is a complex condition to study. Researchers are also looking into how stress and environmental factors could contribute to social anxiety.

Social anxiety disorder can sometimes run in families, but researchers aren’t sure why some family members get it and others don’t. Many parts of your brain are involved with fear and anxiety, so social anxiety disorder is a complex condition to study. Researchers are also looking into how stress and environmental factors could contribute to social anxiety.

When people with social anxiety have to perform in front of or be around other people, they tend to experience certain symptoms, behaviors and thoughts. A person with social anxiety disorder can have these symptoms during specific types of social situations or they can have them in several or all social interactions.

Physical and physiological symptoms of social anxiety disorder can include:

- Blushing, sweating, shaking or feeling your heart race in social situations.

- Feeling very nervous to the point of feeling nauseated in social situations.

- Not making much eye contact when interacting with others.

- Having a stiff body posture when you’re around other people.

Thoughts and behaviors that can be signs of social anxiety disorder include:

- Being very self-conscious in front of other people.

- Feeling embarrassed or awkward in front of other people.

- Feeling your mind “go blank” and not knowing what to say to other people.

- Feeling very afraid or worried that other people will judge you negatively or reject you.

- Finding it scary and hard to be around other people, especially strangers.

- Avoiding places where there are people.

Diagnosis and Tests

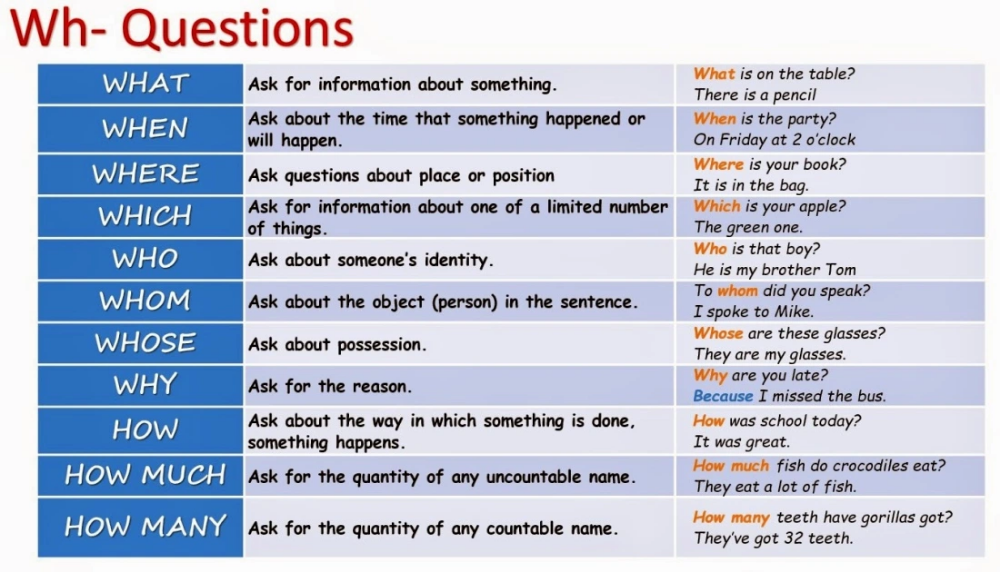

A healthcare provider such as a clinician, psychologist, psychiatrist or therapist can diagnose a person with social anxiety disorder based on the criteria for social anxiety disorder listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) published by the American Psychiatric Association. The criteria for social anxiety disorder under the DSM-5 includes:

- Experiencing continuing, intense fear or anxiety about social situations because you believe you may be judged negatively or humiliated by others.

- Avoiding social situations that may cause you anxiety, or enduring them with intense fear or anxiety.

- Experiencing intense anxiety that's out of proportion to the situation.

- Experiencing anxiety and/or distress from social situations that interfere with your day-to-day life.

- Experiencing fear or anxiety in social situations that aren’t better explained by a medical condition, medication or substance abuse.

Your healthcare provider or another clinician will likely see if the DSM-5 criteria match your experience by asking questions about your symptoms and history. They may also ask you questions about your medications and do a physical exam to make sure your medication or a medical condition isn’t causing your symptoms.

A person typically has to have had symptoms of social anxiety disorder for at least six months in order to be diagnosed.

Healthcare professionals and psychologists can use certain tools or tests — usually a series of questions — to learn more about what you’re experiencing to gauge whether or not you could have social anxiety disorder.

Based on the responses, your healthcare provider can then make a social anxiety disorder diagnosis.

Management and Treatment

Social anxiety disorder is highly treatable with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or medication such as antidepressants (typically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors also known as SSRIs or beta-blockers).

What is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)?

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is a form of psychological treatment. Your psychologist or therapist works with you to change your thinking and behavioral patterns that are harmful or unhelpful.

CBT usually takes place over multiple sessions. Through talking and asking questions, your therapist or psychologist helps you gain a different perspective. As a result, you learn to respond better to and cope with stress, anxiety and difficult situations.

Antidepressants are effective for depression and anxiety disorders and are a frontline form of treatment for social anxiety disorders. Anti-anxiety medications are typically used for shorter periods of time. Blood pressure medication known as beta-blockers can be used for symptoms of social anxiety disorder as well. Specific medications that are used to treat social anxiety disorder include:

- SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors): SSRIs are a type of antidepressant. Common SSRIs used to treat social anxiety disorder include fluoxetine (Prozac®), sertraline (Zoloft®), paroxetine, citalopram and escitalopram.

- SNRIs (serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors): SNRIs are another type of antidepressant. Venlafaxine or duloxetine (Cymbalta®) are common SNRIs used to treat social anxiety disorder.

- Benzodiazepines: These medications are used for short periods of time, either while the antidepressants start to work or used on-demand in situations that provoke anxiety. They aren’t intended to be used for long periods. Lorazepam or alprazolam are examples of benzodiazepines.

- Beta-blockers: Some beta-blockers are used to treat or prevent physical symptoms of anxiety, such as a fast heart rate. Propranolol or metoprolol are examples of beta-blockers.

It could take time to figure out the best dosage and type of medication for you. Know that starting the process of treating your social anxiety disorder brings you one step closer to feeling better.

Yes, there can be side effects from the antidepressants, anti-anxiety medication and beta-blockers used to treat social anxiety disorder. The type of side effects depends on the medication and how your body responds to it. Ask your healthcare provider or psychiatrist about what you can expect after you’ve started a medication.

Antidepressants (SSRIs and SNRIs) can take weeks to start working. Although it might be difficult to have to wait until you start feeling better, it’s important to begin treatment if you have social anxiety disorder, and to stick with it. Ask your healthcare provider or psychiatrist when you can expect to feel better after starting an antidepressant.

Anti-anxiety medications usually take effect quickly. They’re usually not taken for long periods of time because people can build up a tolerance to them. Over time, higher and higher doses are needed to get the same effect. Anti-anxiety medications can be prescribed for short periods while the antidepressant starts to work.

Beta-blockers also work quickly to help with specific symptoms of anxiety, such as tremors or feeling like your heart is racing. However, like the anti-anxiety medications, they can’t treat depressive symptoms that may coexist with social anxiety disorder.

Prevention

Healthcare professionals and researchers are still trying to figure out the cause of social anxiety disorder. So far, they’ve found that the risk factors for developing social anxiety disorder can include:

- Genetic, when social anxiety disorder runs in your family.

- If you experienced parenting that’s overly controlling or invasive as a child.

- If you experienced stressful of fearful events in your life.

Outlook / Prognosis

People with social anxiety disorder respond very well to treatment, whether that’s in the form of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), medication or both. Some people who have social anxiety disorder may have to take medication for the rest of their life to manage their social anxiety. Others may only need to take medication or be in psychological therapy for a certain amount of time.

If left untreated, social anxiety disorder can be debilitating and can result in poor education outcomes, declining job performance, lower-quality relationships and an overall decreased quality of life. A large percentage of people who have social anxiety disorder and don’t get treatment can develop major depression and/or alcohol use disorder. Because of this, it’s very important to contact your healthcare provider and seek treatment if you have symptoms of social anxiety.

If left untreated, a person with social anxiety disorder could have it for the rest of their life. People who are on medication and/or participate in psychological therapy for their social anxiety are often able to drastically lessen or overcome their symptoms and anxiety. They learn how to live with the social anxiety but not let it overwhelm them.

People who are on medication and/or participate in psychological therapy for their social anxiety are often able to drastically lessen or overcome their symptoms and anxiety. They learn how to live with the social anxiety but not let it overwhelm them.

It’s almost impossible to overcome social anxiety without treatment. Social anxiety disorder is a medical condition. Like all other medical conditions, it requires treatment. Evidence has shown that cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and medications like antidepressants are very successful in treating and managing social anxiety disorder. Treatment can help you drastically lessen or overcome your symptoms and anxiety in social situations.

Living With

It can be uncomfortable and scary, but it’s important to tell your healthcare provider if you’re experiencing signs and symptoms of social anxiety disorder.

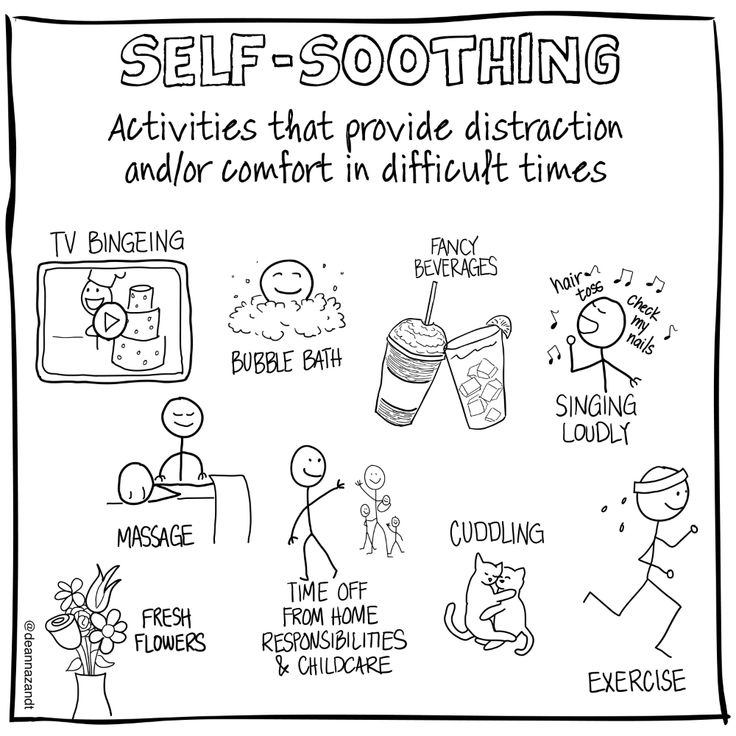

If you’ve already been diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, there are some things you can do to manage your symptoms and feel well, including:

- Get enough sleep and exercise.

- Don’t use alcohol or recreational drugs.

- If you take medication for your social anxiety, be sure to take it regularly and don’t miss doses.

- If you participate in talk therapy, be sure to see your therapist regularly.

- Reach out to family and friends for support.

- Consider joining a support group for people who have social anxiety.

- See your healthcare provider regularly.

When should I see my healthcare provider?

If you’re experiencing signs or symptoms of social anxiety disorder, be sure to talk to your healthcare provider. Getting treatment for social anxiety is crucial to feeling better and reaching your full potential.

If you’ve already been diagnosed with social anxiety disorder, be sure to see your healthcare provider regularly. If you’re experiencing worsening or concerning symptoms, or think your treatment isn’t working, contact your healthcare provider as soon as possible. Don’t discontinue medications on your own without discussing it with your healthcare provider first.

What questions should I ask my doctor?

Asking for help or talking about your mental health can be uncomfortable. But your mental health is just as important as your physical health, so it’s important to talk to your healthcare provider about your symptoms. Some questions that may be helpful to ask your healthcare provider if you have or think you might have social anxiety disorder include:

- Should I see a therapist, psychologist and/or psychiatrist?

- Do you have any recommendations for psychologists, psychiatrists or therapists that I could see?

- Is there medication I can take for social anxiety disorder?

- Do you know of any support groups for social anxiety disorder?

- Do you know of any books I could read about social anxiety disorder?

- What are the next steps after I’ve been diagnosed with social anxiety disorder?

Frequently Asked Questions

While social anxiety disorder and agoraphobia both involve anxiety and public places, they’re different mental health conditions.

Social anxiety disorder is an anxiety disorder where you have intense and ongoing fear or anxiety that you’ll be judged, watched or humiliated by other people in social situations.

A person with agoraphobia experiences feelings of panic or helplessness when they’re in certain places or in certain situations, not necessarily because of other people. They fear situations where escape might be difficult if something were to go wrong. Agoraphobia is an anxiety disorder that typically develops after one or more panic attacks.

There isn’t a significant difference between social anxiety disorder and social phobia. Social anxiety disorder used to be called social phobia. Prior to 1994, a diagnosis of social phobia meant you experienced fear and anxiety when performing in front of people. In 1994, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) changed the name to “social anxiety disorder” and expanded the criteria for diagnosis. It was changed to include the fear and anxiety of being judged or watched by others in social situations, not just when performing.

There are multiple things you can do to help and support someone with social anxiety, including:

- Learn about social anxiety disorder: Educate yourself about social anxiety disorder to better understand what they’re going through. Don’t assume you know what they’re experiencing.

- Be empathetic: Don’t downplay or dismiss their feelings and experiences. Let them know that you’re there to listen and support them. Try putting yourself in their shoes.

- Encourage them to seek help and/or treatment: While having an understanding and supportive friend or family member is helpful to a person with social anxiety, social anxiety disorder is a medical condition. Because of this, people with social anxiety disorder need cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or medication to treat and manage their social anxiety. Encourage them to talk to their healthcare provider if they’re experiencing signs and symptoms of social anxiety.

- Be patient: It can take a while for someone with social anxiety disorder to get better once they’ve started treatment. Know that it’s a long and complex process and that their symptoms and behaviors will eventually improve.

A note from Cleveland Clinic

Social anxiety disorder is a common condition that affects people all over the world. If you experience signs of social anxiety disorder or have been diagnosed, know that you’re not alone. While experiencing social anxiety can be scary, the good news is that it’s treatable. Your mental health is just as important as your physical health, so be sure to talk to your healthcare provider about what you’re experiencing. The sooner you get help and treatment, the sooner you’ll feel better.

ICD-10 and DSM-V: differences in the diagnosis of eating disorders

“Today there are 2 main guidelines that specialists from different countries rely on to classify and diagnose all existing diseases, including eating disorders. These are the ICD (International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems) and the DSM (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders).

Of course, there are also national guidelines and classifications. For example, in Soviet psychiatry, such a type of schizophrenia as sluggish schizophrenia was separately distinguished, although such a diagnosis is generally absent in international classifications.

Nevertheless, qualified specialists are guided by the ICD or DSM in their work.

The ICD has more than three hundred years of history and is currently the official regulatory document of the World Health Organization.

ICD went through 10 editions. The current ICD-10 is used, which has been in use in WHO Member States since 1994. And work is already underway on the ICD-11, which is planned to be introduced after 2018.

It is important to note that ICD-10 covers all diseases. Mental and behavioral disorders are presented there only in a separate chapter. And eating disorders are not singled out in a separate rubric in this chapter, but are included in a broader rubric - Behavioral Syndromes Associated with Physiological Disorders and Physical Factors.

This heading has a subheading "Eating Disorders" (code F50), which includes:

- anorexia nervosa

- bulimia nervosa

- overeating associated with other psychological disorders

- Vomiting associated with other psychological disorders

- other eating disorders

- Eating disorder, unspecified

The fundamental point is that in the ICD-10 there is only a classification and key features of eating disorders. And that's it! Data on detailed description of criteria, prevalence, differential diagnosis, etc. in the ICD, unfortunately, you will not find.

Regarding the DSM, this guide was originally developed by the American Psychiatric Association. The first edition (DSM-I) was in 1952. Now the 5th edition (DSM-V), released in 2013, is already in use. This edition is not available in Russian.

A distinctive feature of this manual is the detailed classification and, most importantly, the description of mental disorders (hence the name).

In particular, a separate section is devoted to eating disorders.

The following eating disorders are distinguished in it:

- “peak” (perverted appetite)

- chewing disorder

- avoidant/restrictive eating disorder

- anorexia nervosa

- bulimia nervosa

- overeating

- other specific eating or eating disorders

- non-specific eating or eating disorders

An important difference of the DSM-V is that, unlike the ICD-10, for each of the major eating disorders are given:

- criteria for diagnosing eating disorders

- extended explanation for each criterion

- subtypes or severity of disorder

- diagnostic features

- data on the prevalence of the disorder

- information on the course and development of the disease

- risk factors

- specific diagnostic markers

- suicide risk data

- consequences of an eating disorder

- differential diagnosis

- relationship with other psychiatric disorders (not related to eating disorders).

In addition, DSM-V is the most current version released in 2013. It presents the latest data on the criteria for mental disorders, some of which differ from those in earlier versions of the guide.

This also applies to eating disorders.”

The author of the article is Sergei Leonov, source https://www.b17.ru/article/mkb10-i-dsm5-otlichiya-v-diagnostike/

* — required fields

By submitting an application, you agree to the terms

of the privacy policy

See also

Self-injurious behavior (selfharm)

Self-harm is a form of auto-aggression, which is expressed in a deliberate or subconscious desire ...

Read more »

On the OTR TV channel about anorexia

Chief Physician of the Center for the Study of Eating Disorders, psychiatrist, psychotherapist …

Read more »

Interview of the chief physician to the portal anorexia. pro

Maksim Sologub, head physician of the Moscow Center for the Study of Eating Disorders, tells…

Read more »

Anorexia. The plot of the program "Live healthy" on the First channel

We are on the first!

Read more »

Release of the Good Morning program on Channel One

Watch the episode of the Good Morning program on Channel One dedicated to the Day of Struggle against …

Read more » On October 13, the program “Live Healthy” was released, where the psychiatrist of the Center took part ...

Read more »

Autism Spectrum Disorder in DSM-5 code 299.00

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition) is a nosological system used in the United States since 2013, a “nomenclature” of mental disorders. Developed and published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). DSM-5 published May 18, 2013, supersedes DSM-IV-TR 2000.

Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) is a spectrum of psychological characteristics describing a wide range of abnormal behaviors and difficulties in social interaction and communication, as well as severely limited interests and frequently repetitive behaviors.

Entered "Autism Spectrum Disorder":

- autism (Kanner syndrome)

- Asperger's syndrome

- childhood disintegrative disorder

- non-specific pervasive developmental disorder

DSM-5 includes for autism spectrum disorders (Autism Spectrum Disorder, ASD) 299.00 (F84.0) the following diagnostic criteria:

A. context, manifesting at the moment or in history in the following (examples are given for clarity and are not exhaustive, see text):

1. Deficiencies in social-emotional reciprocity; starting, for example, with abnormal social convergence and failures to maintain normal dialogue; to reduce the exchange of interests, emotions, as well as the impact and response; to the inability to initiate or respond to social interactions.

2. Deficiencies in non-verbal communicative behavior used in social interaction; starting, for example, with poor integration of verbal and non-verbal communication; to anomalies in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and using non-verbal communication; to the complete absence of facial expressions or gestures.

3. Deficits in establishing, maintaining and understanding social relationships; starting, for example, with difficulties in adjusting behavior to different social contexts; to difficulty participating in imaginative games and making friends; to a visible lack of interest in peers.

B. Limited, repetitive pattern of behavior, interests, or activities, as manifested by at least two of the following (examples are provided for illustrative purposes and are not meant to be exhaustive; see text):

1. Stereotypical or repetitive motor movements, speech, or use of objects (eg, simple motor stereotypes, lining up toys or waving objects, echolalia, idiosyncratic phrases).

2. Excessive need for consistency, inflexible adherence to rules or patterns, ritualized forms of verbal or non-verbal behavior (eg, extreme stress at the slightest change, difficulty shifting attention, inflexible thought patterns, congratulatory rituals, insistence on a fixed route or meal ).

3. Extremely limited and fixed interests that are abnormal in intensity or direction (for example, strong attachment to or excessive preoccupation with and infatuation with unusual objects, extremely limited scope of activities and interests, or perseveration).

4. Over- or under-reacting to sensory input or unusual interest in sensory aspects of the environment (eg, apparent indifference to pain or ambient temperature, negative response to certain sounds or textures, excessive sniffing or touching of objects, fascination with light sources or objects in motion).

Specify severity:

Severity is based on impaired social interaction and limited, repetitive behaviors (see Table 2).

p. Symptoms must be present early in development (but may not become fully apparent until social demands exceed limited capacity, or be masked by learned strategies later in life).

D. Symptoms cause clinically significant impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of daily functioning.

E. These disorders are not explained by intellectual disability (mental retardation) or general developmental delay. Intellectual disability and autism spectrum disorders often coexist; in order to diagnose comorbidity between autism spectrum disorder and mental retardation, social communication must be below what is expected for the general level of development.

Note:

Individuals with well-established DSM-IV autism, Asperger's syndrome, or non-specific pervasive developmental disorder (PDD-NOS) under the DSM-V will be diagnosed with an autism spectrum disorder. Individuals with significant social communication and interaction impairments whose symptoms do not meet criteria for autism spectrum disorder should undergo a diagnostic evaluation for social communication (pragmatic) disorder (315.39(F80.89)).

Additionally specify:

With/Without accompanying mental retardation (developmental delay).

With/Without an accompanying defect (speech disorder).

A disorder associated with a medical condition, or genetics, or a known environmental factor. (Coded note: Use additional code(s) to identify associated medical or genetic conditions.)

A disorder associated with impaired development, behavior, mental or other abilities of a neurological nature. (Coded note: Use additional code(s) to define neurodevelopmental mental or behavioral disorders.)

With/Without catatonia(s) (see criteria for catatonia associated with another psychiatric disorder, pp. 119-120, for a definition). (Coded note: Use additional code 293.89 [F06.1] for autism-related catatonia to indicate the presence of comorbid catatonia.) Severity