Have eased worry or anxiety

How I've Eased My Anxiety by Being More Present: 4 Practices to Try

“Breathe. Let go. And remind yourself that this very moment is the only one you know you have for sure.” ~Oprah Winfrey

In 2012, during my community college years, I began to experience mild anxiety.

I assume it was the stress and fear that came with maintaining a good GPA in hope of transferring to a well-known university, alongside deciding what I wanted to do for the rest of my life. Or perhaps it was because of the time I knew I’d wasted slacking in high school to fit in with what I was surrounded by and to preserve my loud-mouthed drama-seeking status.

The next few years, I thought about the past and future a lot, cried, and grasped for many breaths during anxiety attacks near the campus pond.

In late 2016 I faced my first severe anxiety attack in the laundry room of my parents’ home while sitting against the washing machine and holding onto my legs curled up against my chest.

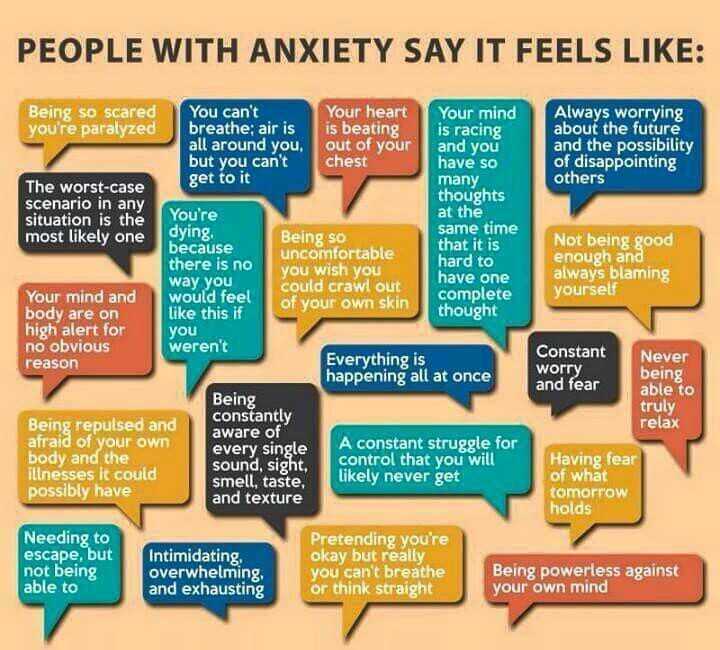

For the first time ever, I felt a heavy pain in the core of my body as if there were rocks piling up all the way to my throat and closing my airway to breathe. I had never felt so disheartened, lost, empty, and hopeless.

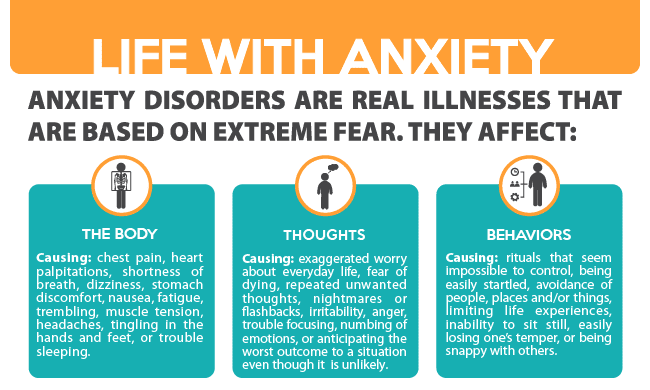

Soon, my anxiety attacks got to the point where I faced numbing and tingling sensations in my head, face, hands, and feet.

It wasn’t until countless severe anxiety attacks in that I had a glimpse of awareness behind my ongoing stream of thoughts. I found that I was experiencing stress and fear about what had happened in the past or would happen in the future and realized that I’d lost the present moment.

Many of us face day-to-day suffering through anxiety. We worry about progressing in our careers, getting an education, making a decent income, being there for our families, putting food on the table, and always working toward a means to an end.

I realized that many of us are constantly on the run to the future trying to be certain about what’s next, and if we slip and fall along the way, we worry about why it happened, which takes us into the past—eventually emerging from an egoic-state of fears, wants, needs, and expectations. That was me.

That was me.

There’s always going to be something new that we’ll want, need, and expect while trying to stay up to par with the people and situations that surround us. We’ll spend a lot of time sulking over setbacks, failures, and loss. Ultimately, suffering from stress and anxiety will bury what we’re meant to experience, learn, and grow from in this moment, the present moment. Because we can’t fully immerse ourselves in this moment if we’re worrying about the next or regretting the one prior.

I’ve spent the last few years exploring, reading, learning, and practicing how to heal stress and anxiety with the simple, yet profound practice of being present, conscious, and aware.

With this practice, I’ve strengthened my ability to acknowledge and allow suffering to take its course when facing life’s inevitable difficulties and challenges.

The following are a handful of ways I practice presence, which has not only dissolved my anxiety, but also awakened my gratitude for the great joy and peace we can experience once we become conscious and aware in this moment.

4 Ways to Practice Presence

1. Practice non-judgment, non-attachment, and non-resistance.

You can lose yourself into the past and future when you’re judging, getting attached to, and resisting what is. This is because we become fixated on our wants, needs, and expectations of the moment instead of fully experiencing it. If we want to minimize our suffering, we need to be here in the present moment and allow what is to be and pass.

I know this practice is easier said than done.

I’ve had days where I was over the moon with immense joy during moments of achievements, when sharing laughs with family, and while celebrating milestones like my wedding. I also became attached, wanting the moments to last forever and feeling saddened that they had to come to an end.

On the contrary, I’ve also had days where I felt gutted and devastated over the loss of my dad, and I couldn’t help but judge and resist the experience of losing him. I had expected him to be around for future milestones and heartfelt moments.

Yet, I’ve learned that moments are undeniably and inevitably temporary. Joy doesn’t last forever, but neither does pain. Allow the painful moments to be and pass and truly savor the good ones with your presence and full attention.

Practice being and experiencing this moment as it is without judgment, attachment, and resistance. Enjoy the good moments and learn and grow from the ones that aren’t that great.

This will allow you to surrender to and accept the process and flow of life, which is the key to decreasing your suffering.

2. Focus on your breath.

Realize that you have no control over your past or future breath, only the one in this moment right now. Similarly, you have no control over what happened in the past and can never be certain of the future.

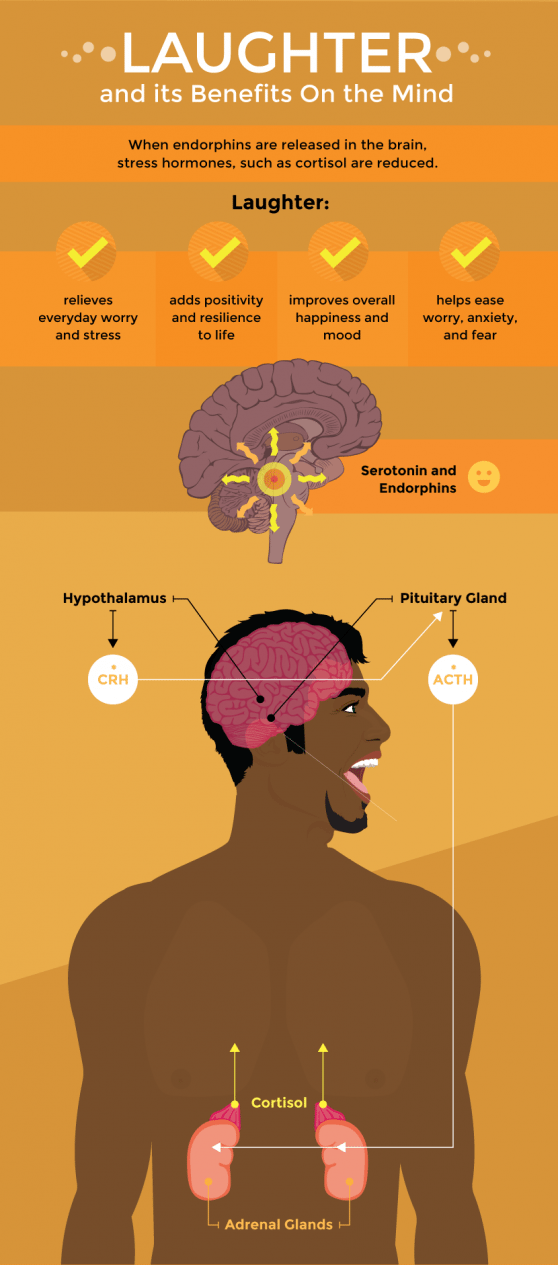

In many experiences in life, from meditation, yoga, exercise regimes, and sports to childbirth and even suffering, we’re always reminded to just breathe. It’s the breath that guides us into the present moment where the actual being and doing is.

Try your best to concentrate on the inhaling and exhaling momentum at a gentle and patient pace throughout your day. It’s a form of meditation that can be done anywhere and anytime to dissolve any stress and anxiety you face.

I practice this throughout my day all the time whether I’m at work or on the couch, just to redirect my focus into the now, especially when I become aware of nonstop thoughts, which can set the stage for suffering.

This practice brings you out of your head and into your body and allows you to immediately shift your focus away from your worries, fears, and regrets.

3. Immerse yourself in nature.

Have you ever felt immense peace while looking at the sunrise or sunset and a calmness when around trees, flowers, plants, rivers, lakes, and waterfalls?

When you’re with nature, you instantly become connected to its stillness, silence, and simplicity.

Even during the roughest storms, nature reminds us to become in sync with what is to allow the storm to take its course and pass.

To be in nature, you don’t have to go far. Step into the backyard or take a walk around the block. Pay attention to the beauty of the flowers or the rustling wind in the trees and embrace the peace and joy that arises from it.

You’ll find that nature truly has a way of reconnecting you to this moment.

4. Be grateful and trust what is.

So grateful, I whispered to myself as I stood outside in the backyard watching my puppy Oakley running back and forth on the grass, my husband playing with him and the sun setting.

It would have been easy to lose myself to thoughts about what’s next and why I still at times feel lost and hopeless, but those thoughts never resolve how I feel and only ignite my anxiety. I decided to instead be grateful for the blessings in that moment, trust that what’s next will get here when it does, and for now, practice being present with what is.

Be grateful for what is right now, even if you’re going through challenging times. Let your trust for the process be bigger than your fear, stress, and anxiety. When you trust the process, you tell life that you are one with its flow and allow the experience to make you stronger, teach you something new, and guide you onto a path of growth.

Let your trust for the process be bigger than your fear, stress, and anxiety. When you trust the process, you tell life that you are one with its flow and allow the experience to make you stronger, teach you something new, and guide you onto a path of growth.

Take a breath to recenter yourself into this moment and look around to see what you can appreciate. Perhaps it’s this blog, a family member, your pet, a plant, a cup of coffee, or a meal. Maybe it’s the sun or rain.

It’s easier to let go of the past and stop trying to control the future when you’re fully immersed in the now. Whatever your life entails in this moment, be present with it, because that is the ultimate path to healing and finding your power in life.

About Jasmine Randhawa

Jasmine Randhawa is a writer, a creative, an author of a self-published children’s picture book, and a former personal injury law paralegal. With more than seven years of education and experience in research, writing, and working with many who suffered from stress, anxiety, trauma, and loss, she now shares work around embracing the journey beyond pain and suffering to harvest the sweetness of life with more presence, joy, and peace. See more at: https://linktr.ee/Jasminekaurtoday

See more at: https://linktr.ee/Jasminekaurtoday

See a typo or inaccuracy? Please contact us so we can fix it!

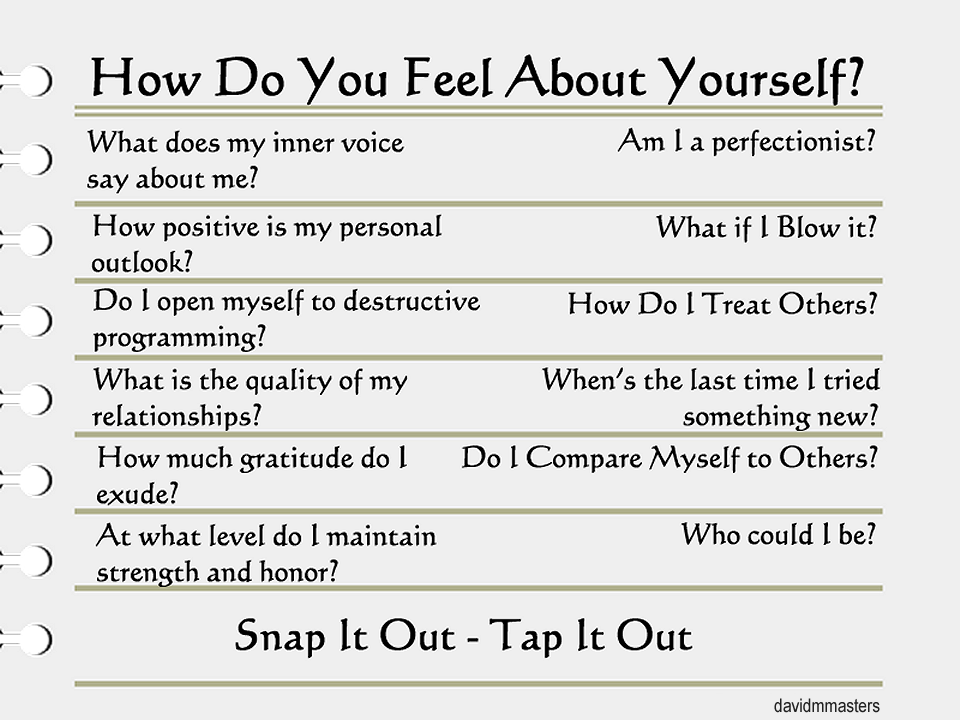

Worry and Anxiety: Do You Know the Difference? | Henry Ford Health

Posted on August 21, 2020 by Henry Ford Health Staff

1952

Share

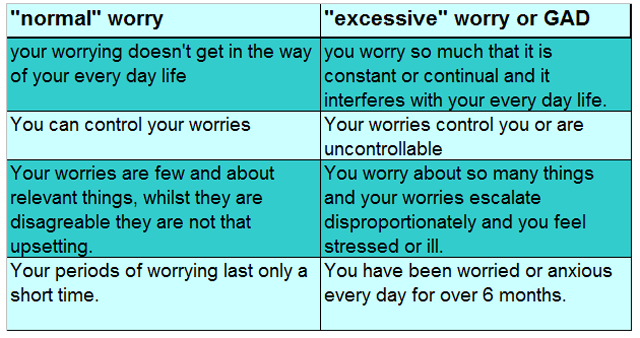

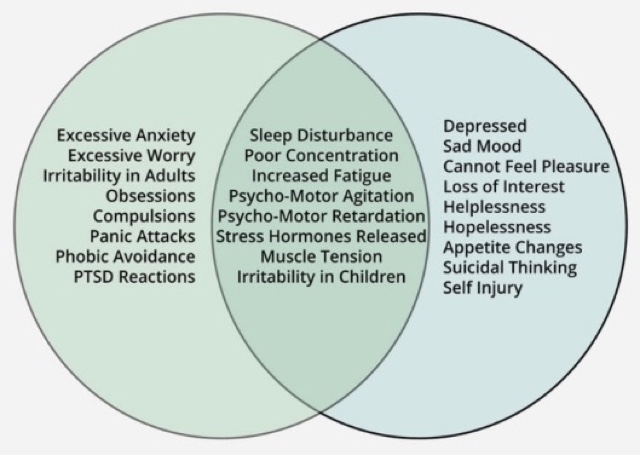

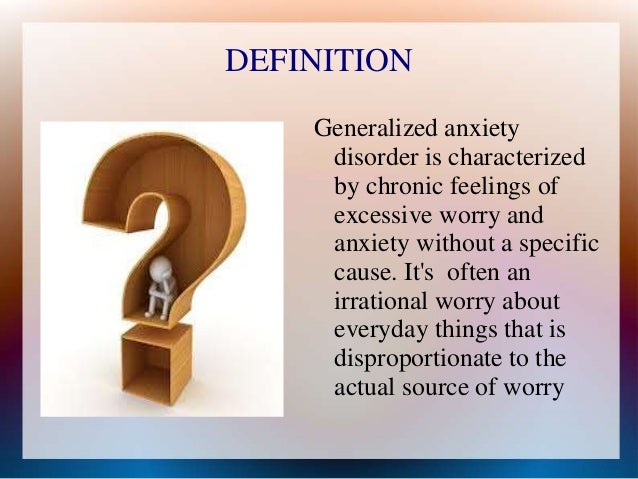

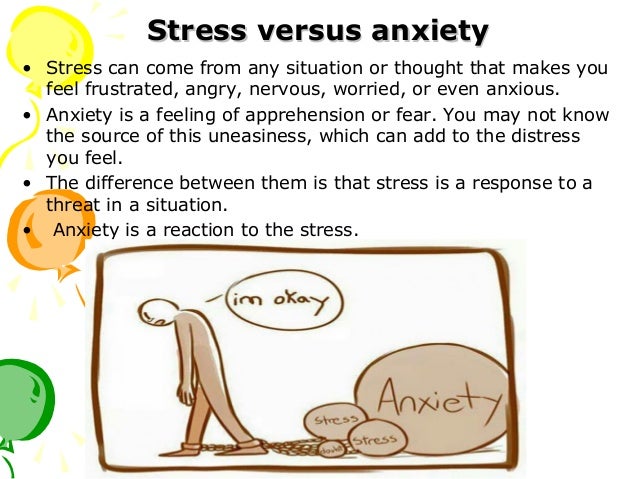

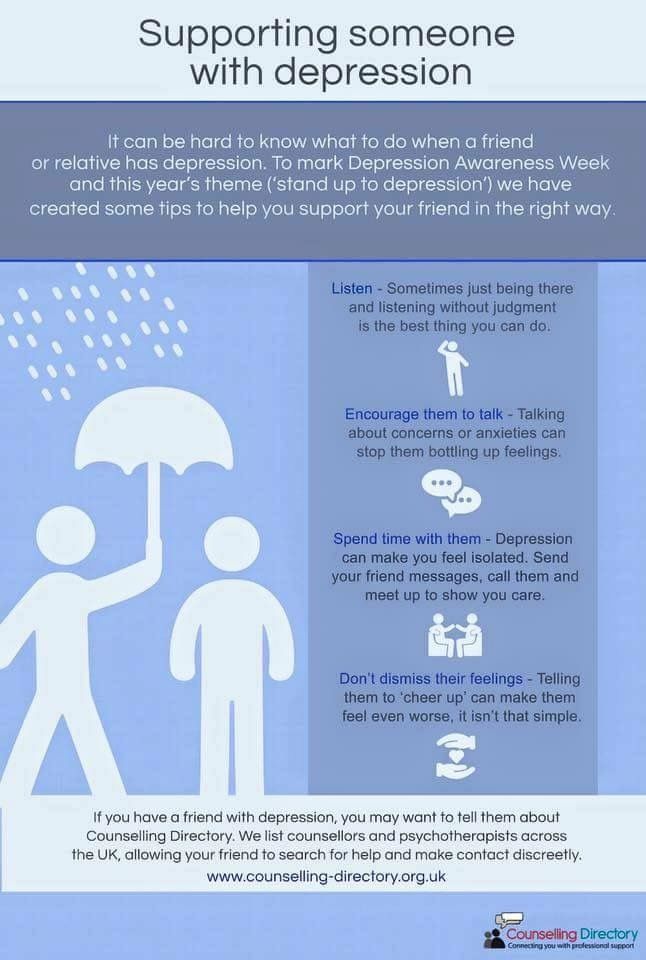

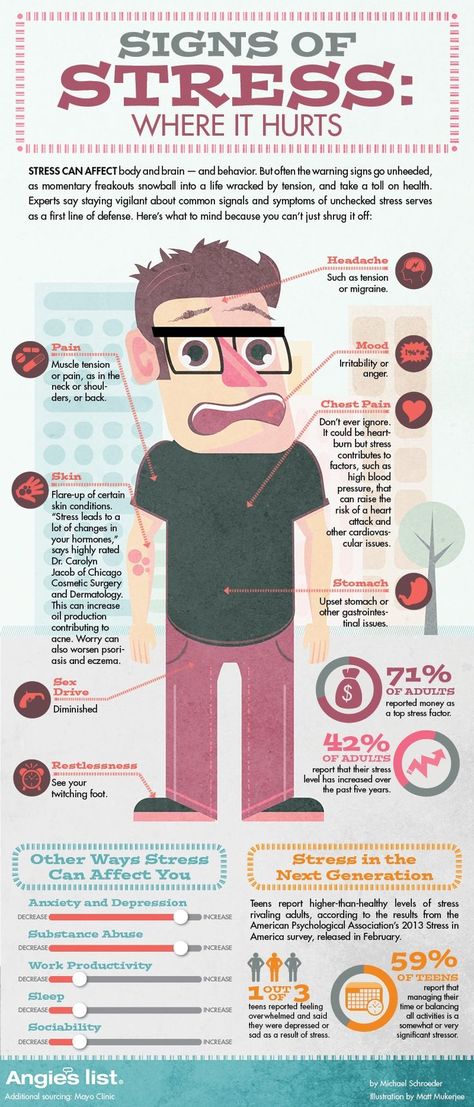

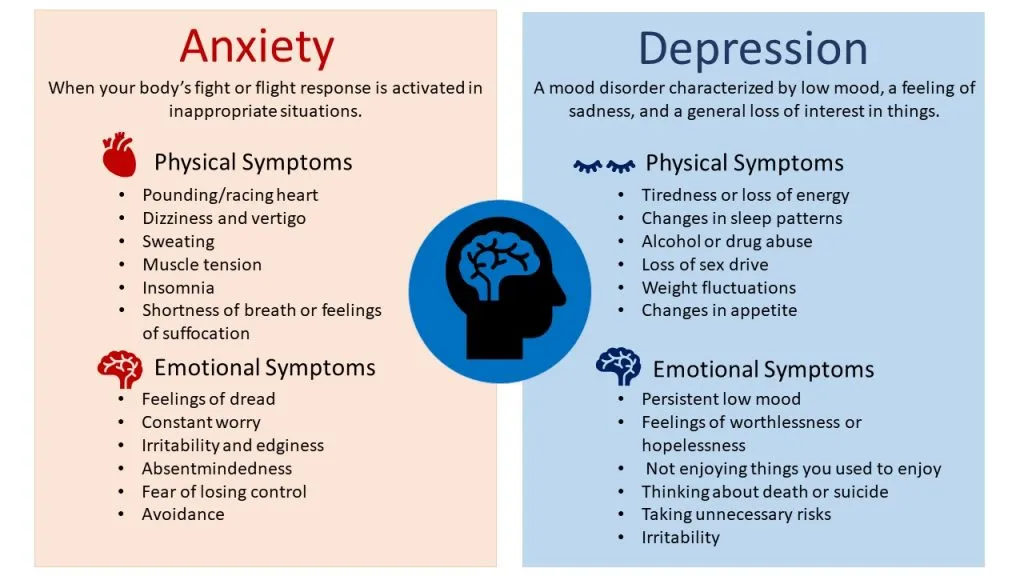

With today's tumultuous and uncharted climate, a certain amount of worry and anxiety are normal. While we use these terms interchangeably, they are entirely different animals — and they have different implications for health and well-being.

"If people aren't a little bit worried right now, that's a problem," says Jeffrey Devore, MSW, a behavioral health social worker at Henry Ford Health. "Worry and anxiety fall on a spectrum. They're different states, but they're also interrelated. "

"

Worry Versus Anxiety

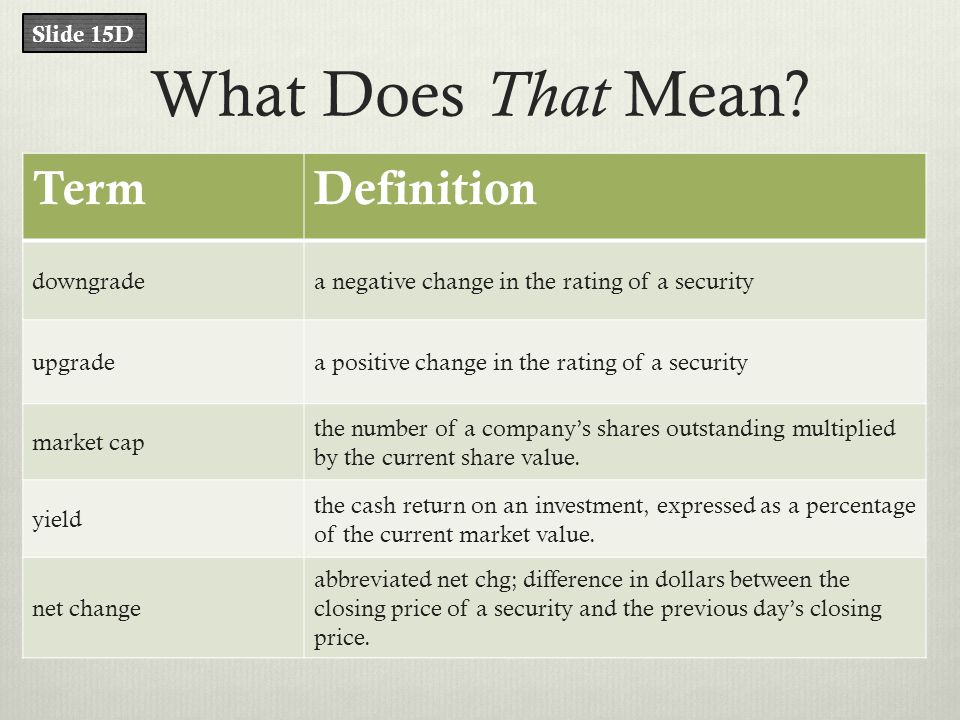

Chances are good that you regularly experience some level of worry (or even anxiety). But what do these terms really mean? Both states are marked by a sense of concern, disquiet and possibly stress. But they're not the same.

Here are five key differences between worry and anxiety:

- Worry tends to reside in our minds. | Anxiety affects both body and mind.

"Everyday worries take place in your thoughts, while anxiety often manifests physically in the body," Devore explains. "You might feel faint or lightheaded. Some people even hyperventilate." People who are anxious are also more likely to suffer from digestive problems like nausea, indigestion and irritable bowel syndrome. - Worry is specific. | Anxiety is more generalized.

Whether you're fixating on your odds of contracting the coronavirus or trying to figure out how you'll be able to homeschool three children, worry is distinct and concrete. Anxiety is generally vague. You feel unsettled, but you can't pinpoint what you're really anxious about — and that can make problem-solving difficult.

Anxiety is generally vague. You feel unsettled, but you can't pinpoint what you're really anxious about — and that can make problem-solving difficult. - Worry is grounded in reality. | Anxiety is marked by catastrophic thinking.

There's a logical component to worry. Your brain is trying to make sense of a real and present danger. Worrying when your fears are actionable makes sense. It’s worry that can lead you to take coronavirus precautions, like washing your hands and wearing a mask. Anxiety, on the other hand, overestimates risk. "So if the real risk of a negative outcome is 10%, someone who is anxious may perceive the risk closer to 70%," Devore explains. To make matters worse, people who are suffering from anxiety may underestimate their ability to cope with a negative outcome. - Worry is temporary. | Anxiety is longstanding.

Worry is usually short term. There's a concerning situation (like COVID-19) and you worry about it. Worry prods you to use problem-solving skills to address your concerns. Anxiety is persistent, even when concerns are unrealistic. It often compromises your ability to function.

Worry prods you to use problem-solving skills to address your concerns. Anxiety is persistent, even when concerns are unrealistic. It often compromises your ability to function. - Worry doesn't impair function. | Anxiety does.

You probably won't be forced to take a sick day due to worries about finances or weight gain. Anxiety, however, seeps into your psyche and can make it difficult to focus and get stuff done.

"Worry and anxiety are not all bad. In fact, they can motivate change," Devore says. "The key is using problem-solving skills to address what you're worried about and reduce the risk of your fears being realized."

Related Topic: Is It Depression? Your Questions Answered

What to Do if You're Worrying Excessively

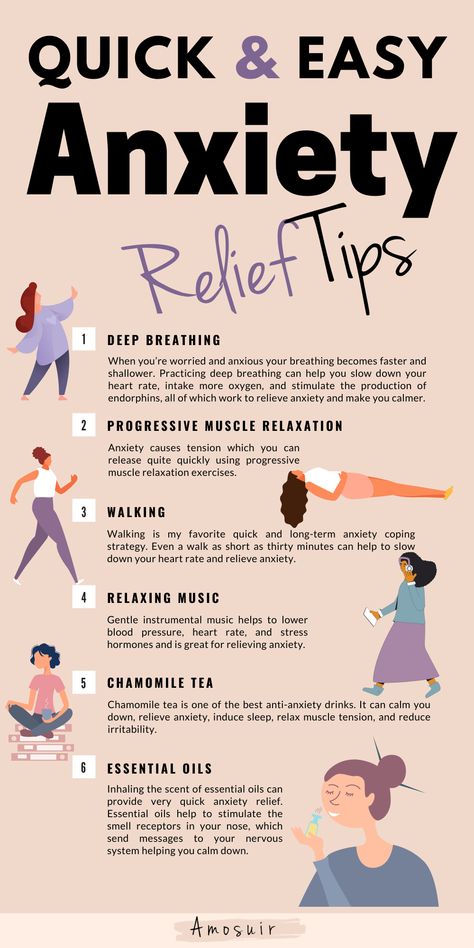

If you worry excessively, or if you're struggling with anxiety, there are a number of things you can do on your own or with the help of a professional to quiet your reactions. A few things you can do at home:

- Turn off the news: Watching the news increases feelings of stress.

You can learn the basics and discover what's going on in the world with only two minutes of screen time. "Anything more than that, and you're just watching the same anxiety-provoking news on a loop," Devore says.

You can learn the basics and discover what's going on in the world with only two minutes of screen time. "Anything more than that, and you're just watching the same anxiety-provoking news on a loop," Devore says. - Practice mindfulness: Taking five or 10 minutes a day to tune into yourself and your surroundings can have powerful anxiety-quelling effects. "Many of my clients use apps like Calm or Thrive to help reduce stress and anxiety," Devore says.

- Challenge negative thoughts: If you frequently think, “I can't do this” or, “I'm stuck,” try challenging that thought with two other thoughts: (1) Is it true? And (2) Is it helpful? In most cases, negative thoughts are fueled by an anxious brain. Stopping them with a challenge test can help reset your mind.

- Get comfortable: Since one of the hallmarks of anxiety is avoidance, exposing yourself to what you're anxious about — in small doses — can help you build up tolerance.

"The idea is to desensitize yourself to discomfort, to sit in the emotion until you acclimate," Devore says. This type of "exposure treatment" works best when patients also learn relaxation and calming skills.

"The idea is to desensitize yourself to discomfort, to sit in the emotion until you acclimate," Devore says. This type of "exposure treatment" works best when patients also learn relaxation and calming skills. - Take steps to decompress: It's important to do things each day that help you decompress and manage uncomfortable emotions. Maybe you go fishing on the weekend. Maybe you like to hike or shoot hoops with your kids. No matter what you do, make sure you take time to recharge and regroup.

Related Topic: Hangxiety: The Link Between Alcohol and Anxiety

Worry and anxiety shouldn't be your default zone. If you're struggling with constant fears and concerns, talk to your doctor. "Most primary care providers can address generalized anxiety," Dr. Devore says. Concerned about visiting the doctor? A number of mental health providers offer video visits or other types of virtual care.

To find a doctor or therapist at Henry Ford, visit henryford. com or call 1-800-HENRYFORD (436-7936).

com or call 1-800-HENRYFORD (436-7936).

Jeffrey Devore is a clinical social worker who sees patients at Henry Ford Medical Center - Troy.

Categories : FeelWell

Tags : Behavioral Health, Jeffrey Devore, Coronavirus, Primary Care

How to overcome worry and anxiety

Why do people worry

Seneca considered the ability to plan for the future one of the most amazing gifts of man. The ability to plan for the future and create many values depends on foresight, that is, on the internal representation of the future.

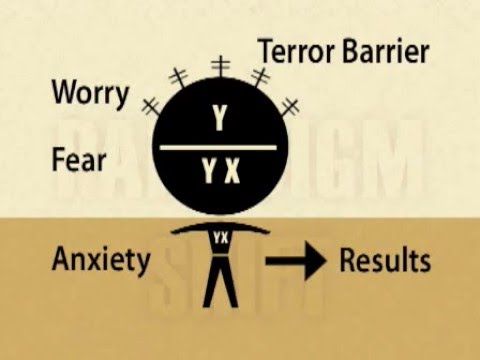

Comparing foresight with the gift of the gods, Seneca believes that there is nothing worse than worry about the future (about what could happen), since for most people this is the main cause of anxiety. In this state, they take "foresight, the greatest blessing given to man", turn it into a source of anxiety.

In this state, they take "foresight, the greatest blessing given to man", turn it into a source of anxiety.

In all his writings, Seneca goes into detail about how anxiety and restlessness arise and how to get rid of this kind of excitement - or at least significantly reduce it. He even describes specific exercises that readers can do to get rid of anxieties, fears, and worries.

Seneca speaks of two main fears that a person must overcome: the fear of death and the fear of poverty (or the desire for wealth). We will explore these important topics in more detail elsewhere in the book. For the time being, suffice it to say that this assertion looks undeniable. But how the Stoics extended this idea is much more difficult to explain.

According to the Stoics, the next step is to realize that all the external, beyond our control things that happen to us should not be considered “bad”, since they are just dispassionate natural facts. They become "bad" due to our judgments, which cause an emotional reaction. Indeed, the cause of almost all negative emotions is judgment or opinion. Modern psychologists call this approach the cognitive theory of emotions , and the ancient Stoics laid the foundation for it.

Indeed, the cause of almost all negative emotions is judgment or opinion. Modern psychologists call this approach the cognitive theory of emotions , and the ancient Stoics laid the foundation for it.

This conviction was shared by absolutely all the Stoics, and Marcus Aurelius expressed it this way: “Take off your confession - “offended me” is removed; removed “offended” - removed the insult.

This idea can be formulated in another way: we have no power over external events, but we can control our reaction to them. For example, you probably had a case in your life when you were walking along the road on a rainy day, and a car passing by sprayed you. You could not dodge the splashes, but your reaction is already your choice. You can just think: “Damn, I got splashed,” or you can shout after the car: “You ruined my whole day!” The natural consequence of your outburst of indignation will be rage and fantasies about how you will take revenge on the driver.

For the Stoic, the first reaction - "I've been splashed" - is an objective statement of a phenomenon that is not in our control. But the second reaction is “you ruined my whole day!” - is a judgment or belief that generates anger and emotional suffering.

But the second reaction is “you ruined my whole day!” - is a judgment or belief that generates anger and emotional suffering.

When we get upset, we usually think that we are reacting to factors in the outside world, but in reality it is a reaction to what is happening inside ourselves: to judgments, beliefs, or opinions. Emotions are the result of internal judgments that we constantly make. Seneca and other Stoics believed that there was no point in getting annoyed at manifestations of the outside world that might be perfectly normal and expected, such as being splashed or people misbehaving. It is better to deal with internal judgments, which are the cause of our irritation. This is a way to make your life more peaceful.

Seneca understood that people have a rich imagination, which determines their feelings and inner judgments. If the power of foresight, which is also a form of imagination, is misused, it creates anxiety or fear that has nothing to do with legitimate, rational reasons. Therefore, we are more likely to worry about the fact that may happen in the future, and the “what if” story is an example of this. What if she leaves me? What if I get into a car accident and can no longer work? What if I don't have enough money to live on after I retire?

Therefore, we are more likely to worry about the fact that may happen in the future, and the “what if” story is an example of this. What if she leaves me? What if I get into a car accident and can no longer work? What if I don't have enough money to live on after I retire?

These fears may be quite justified, requiring serious, rational analysis. But when we lose our cool, they turn into something else - into sources of fear and internal disorder. Seneca considered fear a kind of slavery, and for him there was "nothing more pitiful than doubting how the coming day will end." Because of them, "an anxious spirit will be tormented by an inexplicable fear." The only way to avoid this is not to try to anticipate events, but to live in the present moment, realizing that the present itself is complete and perfect. Seneca often repeats that you can only worry about the future if you are not satisfied with the present.

Speaking about fear or anxiety, Seneca necessarily indicates how to overcome these feelings: instead of mentally “traveling in time” to an imaginary moment in the future, when something bad might happen , and worrying about it now, you need to live in the present, here and now. Reading the works of Seneca, Marcus Aurelius agreed with him. He wrote that "everyone lives only in the present."

Reading the works of Seneca, Marcus Aurelius agreed with him. He wrote that "everyone lives only in the present."

I do not know if Mark Twain read Seneca's works, but he is credited with a similar thought: "I am an old man, and I have had many troubles in my life, but most of them never happened." In other words, these troubles were imaginary.

Seneca explains how to return to the present. He also describes other remedies for restlessness and anxiety. But before proceeding to a detailed analysis of them, it is worth taking a close look at how anxiety arises.

Imagination mirror room

Seneca in his works very often relies on the imagination. He composes great landscape descriptions to set the mood or context for what he wants to explain. Being a rational thinker, he sometimes uses the imagination to convey an image of extraordinary beauty, for example: “Oh, if all philosophy could appear like the universe, when it reveals its whole face to us! How similar those spectacles would be!” In addition, Seneca, like other Stoic philosophers, sometimes offers mental exercises, or visualization, to help find psychological balance. One such exercise, made famous by Marcus Aurelius, is today called "view from above": we imagine that we are in space and look at the Earth below us from afar, see how small we are, and realize the insignificance of our personal troubles on the scale of the universe.

One such exercise, made famous by Marcus Aurelius, is today called "view from above": we imagine that we are in space and look at the Earth below us from afar, see how small we are, and realize the insignificance of our personal troubles on the scale of the universe.

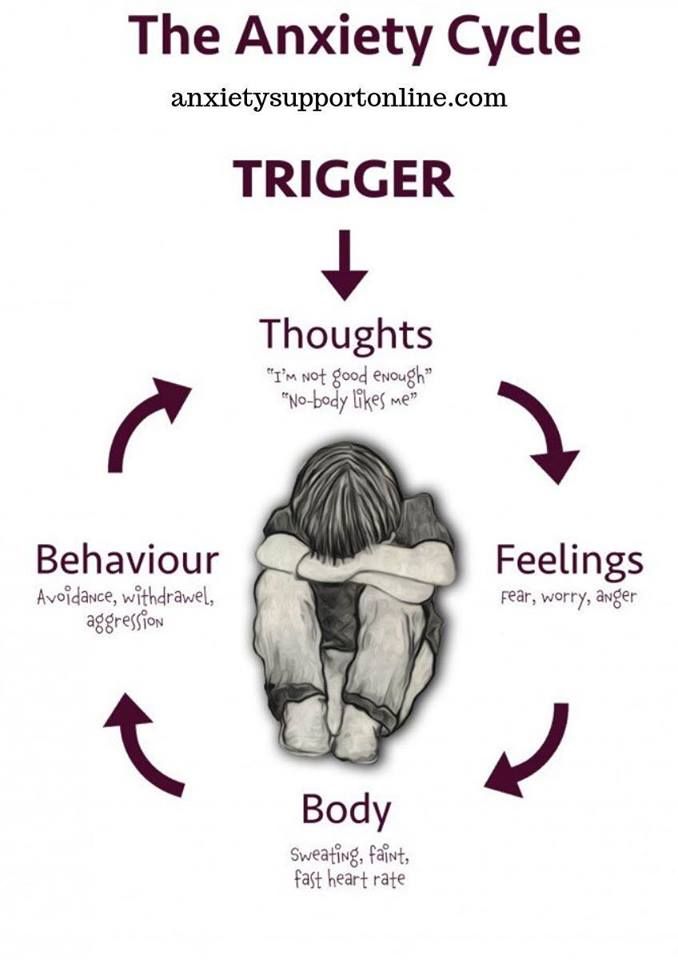

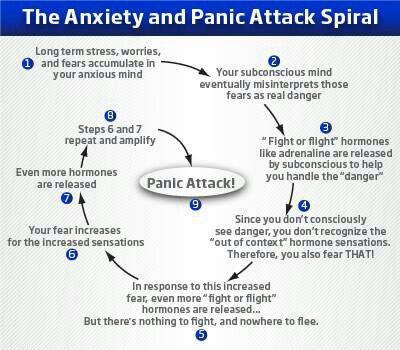

Seneca appreciates the power of foresight that allows us to shape the future. But he sees not only the benefits of imagination, but also its negative aspects. It can cause obsessions, anxiety and fears that spiral out of control. Most people, writes Seneca, "throw around in excitement, even if nothing bad happens to them, and probably does not threaten them."

And if strong emotions are added to the imagination, it creates a feedback loop where the imagination amplifies the emotions, and the emotions, in turn, amplify the imagination. (Modern psychologists call this state of "worry about worry" meta-anxiety , or meta-anxiety .) In this state, when imagination and emotions reinforce each other, the entire system can get out of control, which manifests itself in the form of increased anxiety, panic attacks and other psychological symptoms. A situation where imagination reflects fear and fear reflects imagination can be compared to a mirrored room filled with emotions. Moments of anxiety or anxiety are familiar to everyone, but people with high levels of anxiety often find themselves in just such a room. Seneca wrote: "Everyone is as unhappy as he considers himself unhappy."

A situation where imagination reflects fear and fear reflects imagination can be compared to a mirrored room filled with emotions. Moments of anxiety or anxiety are familiar to everyone, but people with high levels of anxiety often find themselves in just such a room. Seneca wrote: "Everyone is as unhappy as he considers himself unhappy."

Seneca did not use the image of a mirrored room, but the metaphor of a labyrinth. He says that a happy life is available here and now, in the present moment. But when people look for it elsewhere or in other things, they lose the freedom and confidence they would have if they lived in the present. Seneca compares this state, when the feeling of one's own "I" is lost, with the state of a person running through a maze: "It happens with those who are in a hurry to get through the labyrinth: the very haste confuses them."

How to beat anxiety

The philosophy of Seneca indicates several ways to overcome anxiety, and they are all quite simple. But Stoicism involves exercise—it is as much a practical philosophy as Buddhism—and so these methods require conscious application.

But Stoicism involves exercise—it is as much a practical philosophy as Buddhism—and so these methods require conscious application.

One of the main and most effective ways to reduce anxiety is simply to pay attention to internal judgments and the emotions they cause - right in the process as soon as you feel anxious about future events. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus called this exercise prosochē , or "attention." When we understand how emotions arise and are able to monitor this process in real time, from the moment we begin to feel anxiety, we can make a conscious choice and follow the advice of Seneca. That is, we stop thinking about the future and start living in the present, because the future does not even exist.

The Stoics, in particular Seneca, considered reasonable care about future events, but it would be a mistake to worry ahead of time about what might not happen. Here is the advice Seneca gave to Lucilius: “I only teach you not to be unhappy before the time when what you are anxiously waiting for right now may not come at all and certainly has not come. ” This idea is repeatedly found in various works of Seneca. Marcus Aurelius also agreed with this point of view: “Let the future not bother you, you will come to it, if necessary, with the same mind that you now have for the present.”

” This idea is repeatedly found in various works of Seneca. Marcus Aurelius also agreed with this point of view: “Let the future not bother you, you will come to it, if necessary, with the same mind that you now have for the present.”

Second, believing that anxiety, fear, and psychological discomfort stem from misjudgment, erroneous opinions, or misuse of the imagination, Seneca suggests doing a key exercise in Stoicism: carefully analyzing your thought process to identify the source of suffering. If anxiety is caused by false beliefs, then a rational analysis of these beliefs and their debunking will help to cure it. Seneca notes that “we immediately join the general opinion, without checking what makes us afraid, and, without understanding anything, we tremble and take flight ...”, and advises to carefully understand everything. Modern specialists in the field of cognitive psychology call this kind of analysis with the Socratic dialogue is another tribute to ancient philosophy.

Albert Ellis, one of the founders of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), studied the philosophy of Stoicism. When starting work on a new patient, Ellis gave him a piece of paper with the famous Stoic maxim: “People are not confused by things themselves, but by their own ideas about these things.” This is the key to all cognitive therapy. Ellis used a simplified scheme known as the ABC Theory of Emotions, which is directly based on the philosophy of Stoicism. It all starts with an activator (A), that is, an event, a situation, an act. Then judgment, opinion, or belief (B) comes into play. Next comes the consequences (C), the emotional outcome of the judgment.

If on a rainy day you get splashed by a car and you judge, "I got splashed," the main consequence is that you will feel wet. But if you think “I was ruined all day”, which is equivalent to the conclusion “I was harmed”, and the consequence is likely to be intense anger. Thus, emotional reactions are caused by our untested, often irrational beliefs. Fortunately, we are able to identify and even rid ourselves of these false beliefs through analysis through Socratic dialogue, either on our own or with the help of a therapist or mentor.

Fortunately, we are able to identify and even rid ourselves of these false beliefs through analysis through Socratic dialogue, either on our own or with the help of a therapist or mentor.

Nearly 20 percent of the United States population suffers from anxiety disorders. But many people who study Stoicism and use the Stoic Attention Technique report experiencing negative emotions such as anxiety and anger much less frequently.

It is surprising to see how strong the influence of Stoicism has been on cognitive therapy, especially if one considers some of Seneca's letters to Lucilius as brief sessions of psychotherapy. Seneca knew Lucilius and his inner convictions well enough that it is now useful for us to observe how the philosopher questions some of his assumptions. Interestingly, Seneca also explains how other beliefs can lead to more favorable outcomes. This is the process that the modern cognitive therapist uses.

Thus, Stoicism is the forerunner of modern CBT, and the founders of CBT, in particular Albert Ellis and Aaron T. Beck, drew directly on the teachings of the Stoics when developing modern therapeutic methods. In the first serious textbook on cognitive therapy, Beck explicitly states: "The philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to the Stoic philosophers." Both Stoicism and CBT demonstrate that being aware of, and confronting, the distorted thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes that cause suffering can greatly reduce psychological discomfort and anxiety. It is noteworthy that this cognitive "passion therapy", based on stoicism, does indeed eliminate many psychological disorders. For example, CBT is the most studied form of psychotherapy and has become the "gold standard" in the treatment of anxiety. Some studies show that CBT has helped 75 to 80 percent of patients recover from various types of anxiety disorders, including panic attacks.

Beck, drew directly on the teachings of the Stoics when developing modern therapeutic methods. In the first serious textbook on cognitive therapy, Beck explicitly states: "The philosophical origins of cognitive therapy can be traced back to the Stoic philosophers." Both Stoicism and CBT demonstrate that being aware of, and confronting, the distorted thoughts, beliefs, and attitudes that cause suffering can greatly reduce psychological discomfort and anxiety. It is noteworthy that this cognitive "passion therapy", based on stoicism, does indeed eliminate many psychological disorders. For example, CBT is the most studied form of psychotherapy and has become the "gold standard" in the treatment of anxiety. Some studies show that CBT has helped 75 to 80 percent of patients recover from various types of anxiety disorders, including panic attacks.

Another Seneca method, also used in CBT, is to reduce the level of emotions, especially those related to the future. In Letter 5, Seneca remarks that "it is good for us to put an end to all desires for the healing of fear. " He then quotes the words of the Stoic philosopher Hekaton: "You will cease to be afraid if you cease to hope."

" He then quotes the words of the Stoic philosopher Hekaton: "You will cease to be afraid if you cease to hope."

Seneca explains that hope and fear are inextricably linked, since both of these emotions are generated by fantasies about the future. He writes: “... both of them are inherent in the soul of an insecure, anxious expectation of the future. And the main reason for hope and fear is our inability to adapt to the present and the habit of sending our thoughts far ahead.

Our fears about the future may be well founded, and Seneca recommends carefully analyzing them. We can respond to them intelligently, avoiding emotional suffering. So, for example, Seneca notes that people have an irrational fear of death, although death is part of life. Death is natural and inevitable, and therefore it is a cognitive error to consider it something terrible. The Stoic philosopher Epictetus agrees with him:

It is not the things themselves that confuse people, but their own ideas about those things. For example, there is nothing terrible in death, because otherwise it would have seemed so to Socrates. However, since the idea of death inspires fear, it is the cause of fear. So whenever we happen to experience difficulties, be in confusion or sadness, let us not blame anyone else but ourselves, that is, our opinions.

For example, there is nothing terrible in death, because otherwise it would have seemed so to Socrates. However, since the idea of death inspires fear, it is the cause of fear. So whenever we happen to experience difficulties, be in confusion or sadness, let us not blame anyone else but ourselves, that is, our opinions.

Thus, the Stoics did not believe in the existence of real blows of fate, but they perfectly understood that we can perceive what is happening to us in this way - as a consequence of our judgments or opinions. In addition, Seneca pointed out that in some cases it will not be possible to avoid emotional shock. This is a natural, instinctive reaction, not based on opinion. But even in such situations, it is possible to weaken the psychological impact and prevent the emotional shock from developing into something more serious.

For certain conditions, such as the fear of poverty, Seneca suggested specific exercises that will allow you to loosen or break out of the grip of fear, prepare for feelings of failure or negative emotions. Actually, Seneca recommends analyzing in advance all the troubles that we may encounter. And then we will be psychologically prepared if the trouble really happens, and its blow is weakened. However, Seneca does not associate anticipation or even rehearsal of possible troubles with anxiety or fear. It is a way for him to calmly and rationally consider the events that can happen , and deprive future troubles - if they happen - of emotional impact. (Similar techniques are used by modern psychologists.)

Actually, Seneca recommends analyzing in advance all the troubles that we may encounter. And then we will be psychologically prepared if the trouble really happens, and its blow is weakened. However, Seneca does not associate anticipation or even rehearsal of possible troubles with anxiety or fear. It is a way for him to calmly and rationally consider the events that can happen , and deprive future troubles - if they happen - of emotional impact. (Similar techniques are used by modern psychologists.)

All this requires awareness and practice. However, when we feel anxiety about the future, we are able to question it, analyze it, and make a conscious decision to return to the present. But for Seneca, living in the present is not a psychological device, but one of the main principles of a full human life.

Find yourself in the present

And no one is unhappy only from the current causes.

Seneca. Moral Letters to Lucilius .

5.9

Do you want to know why people are so greedy for the future?

Because no one belongs to himself!

Ibid . 32.4

If you live in the present, then you have found yourself and are guided by your true desires and needs. The idea of living your true self, and only in the present, without desiring future states or external things, is one of the keys to achieving stoic happiness or joy. Living in the present, according to the inner self, we experience a feeling of joy, happiness and satisfaction. A metaphor that can be used is that the soul shines like the sun, and that sun will continue to shine as long as we are able to maintain a sense of presence and self-sufficiency. It is impossible to protect oneself from external influences, but they are like clouds floating below the serene and radiant face of the sun. These clouds float by but are unable to change or disturb the sun or its light.

The image of the sun and clouds appears in two of Seneca's letters, and in both cases the sun personifies virtue and joy: any trouble or unrest that we experience, writes Seneca, is "as powerless as the clouds are against the sun. " In the same way, if we experience true joy, "everything that interferes with it is like a cloud that rushes low and cannot overcome the light of day."

" In the same way, if we experience true joy, "everything that interferes with it is like a cloud that rushes low and cannot overcome the light of day."

This powerful symbolic image helps me to assess my psychological state at any moment. Do I have the inner serenity of the sun shining in the present moment when outer troubles seem to be just harmless clouds passing by? Am I experiencing the joy of being and focusing on the present without worrying about an imaginary future event that might not even happen?

If I am not focused, if I do not radiate joy, then I can remember the sun of Seneca and identify myself with it. And then the return to the radiance of the present will not be difficult.

In fact, this "lasting and sure joy" of which Seneca speaks and which is symbolized by the sun is a by-product of the Stoic exercises, and the only way to experience it is to live in the present. But in order for it to become permanent - as far as it is possible due to the imperfection of man - the cultivation of virtue in oneself, the improvement of the soul and the exercises of introspection are necessary. This allows the Stoic to find peace of mind, no matter what troubles they encounter along the way of life.

This allows the Stoic to find peace of mind, no matter what troubles they encounter along the way of life.

Psychologist called exercise to relieve anxiety and stress | Society news | Izvestiya

Natalya Bekhtereva, a psychotherapist at the Clinic of the Institute of the Human Brain of the Russian Academy of Sciences, a member of the coordinating council of the Russian Psychotherapeutic Association, granddaughter of the famous brain researcher academician Natalia Petrovna Bekhtereva, told Izvestiya how to reduce stress and anxiety.

The specialist expressed confidence that in the face of stressful factors, such as an epidemic, a political or military crisis, the negative impact can be reduced by diligently doing everyday things, exercising, watching less TV and spending more time communicating with loved ones.

“Life in a routine, playing sports, limiting news content, recognizing one's emotions is the basis for the prevention of stress and anxiety-depressive disorders,” she emphasized.

Manifestations of anxiety and stress are different for everyone. Someone has insomnia, someone cannot do their usual work, someone neglects daily duties, spending time on the Internet and being afraid to miss something from the flow of events. The number of people who need psychological help is on the rise.

According to Bekhtereva, “we should not pretend that we are not afraid. This is even worse, because then fear and anger, as a result, loss of control, begin to control us, leading to devastating consequences.

But trying to accept and realize your emotions, communicate with loved ones and ask for support, do routine things - this can help.

“When you ask for support, try to clearly articulate what kind of support you want – whether you want to be listened to, hugged, or just kept silent. If you are aware of what emotional state you are in, you thereby expand the sphere that you can control. And by endlessly reading the news that is generated continuously, you increase the chance to raise the level of anxiety and fear very high, and at the same time get a fair amount of unverified information, ”the specialist emphasized.