Growing up fast

The Effects of Trauma from Growing up Too Fast

One of the most common euphemisms and justifications for a certain type of childhood trauma is growing up too fast. It is a euphemism because it is used to minimize the pain that the person felt as a child when their needs werent being met by describing it in seemingly neutral or even positive language. Its a justification because it is often used to argue that growing up faster and becoming mature beyond your years is indeed a good thing.

We will explore and address all of this here.

The Origins and the MechanismWhat is frequently called growing up too fast or being mature beyond your years is simply neglect and abuse. Many children grow up in an environment where they are neglected and abused in such ways that they become little adults who, not only can take care of themselves better or are wiser than others, but also take care of their parents, siblings, or other family members.

Its origins can be summarized in two main points.

Firstly, it happens because parents attribute unfair responsibility and unrealistic standards onto their children. Consequently, the child is expected, for example, to perform a task without anybody actually teaching them how to do it, and is punished if they fail. Or they are expected to be perfect, and if, naturally, they are imperfect, they then receive harsh negative consequences for it. This is not a one-time thing, but a persistent atmosphere the child has no choice but to live in.

And secondly, the child grows up too fast because of role-reversal. Role-reversal means that the caregiver assigns their role onto the child and therefore the child is seen as somebody who has to take care of the caregiver and possibly others. The adult, in contrast, takes on the role of the child. The child internalizes this role and it becomes their self-understanding. And so they start to act as a mature, responsible adult while the actual adult is taken care of as though they were the child.

As a result of this appalling psychological dynamic, the person eventually develops a myriad of psychological, emotional, intellectual, and social problems that can haunt them for the rest of their life.

Here are some of the more common beliefs and emotional issues related to it.

One, believing that you always have to be strong. This results in being disconnected from your needs, sometimes to the degree where you ignore being tired, hungry, full, depressed, and so on. Or, you become counter-depended, where you emotionally act in an overly protective manner and people cant get close to you, which leads to unsatisfying relationships.

Two, believing that you cant ask for help and have to do everything yourself. This often leads to you feeling lonely, isolated, unnecessarily distrustful, or that youre alone against the world. Its very hard for you to express your needs to others, or sometimes even recognize that you have needs.

Three, believing that if you recognize the trauma, abuse, or other injustices you suffered, that you will be weak, flawed, a victimand thats totally unacceptable. This blocks empathy for yourself, and especially empathy for the child that you once were because you are unable to connect with the feelings you felt when you were a child, and by extension makes it impossible to fully heal the original trauma that led you to have these problems in the first place.

Four, feeling empathy for the people who hurt you before feeling empathy for yourself. This also makes it impossible to resolve childhood trauma for the same reason. It is vital to emotionally connect and empathize with your childhood experiences without justifying the people who failed to meet your needs. It also leads to relationships and social environments where you may be mistreated in the same ways you were mistreated as a child.

The most common general effects of it all are poor self-care or even self-harm, workaholism, trying to take care of everybody else, people-pleasing, self-esteem issues, constantly trying to doing more than you are physically capable of, having standards for yourself that are too high or completely unrealistic, feeling toxic guilt and false responsibility, chronic stress and anxiety, lack of closeness in relationships, codependency, staying inor even unconsciously seeking abusive or otherwise toxic social environments.

Heres a quick example of a hypothetical person who had to grow up too fast.

Olivia says she was a strong-willed, curious, and intelligent child. She describes her mother as a weak, incompetent person who always had numerous problems and tried to gather pity from those around her. She blamed her husband, Olivias father, for drinking and pitied herself for being in such an unfortunate situation where she had to take care of two children and constantly worry about everything.

Whenever Olivia expressed her dissatisfaction about how she was being treated, her parents used to shame and guilt-trip her by saying that shes making her mother upset by saying such hurtful things. Olivia felt sad, anxious, and even guilty when her parents were fighting, usually because her father was drinking again. When she grew a little older, she was often expected to take care of her drunk father: help him get home from a local bar, hide all the drinks at home, help him get undressed and ready for bed.

Olivia grew up thinking that she hadand still hasto take care of both her mother because shes so weak and dependent, and of her father since hes a drunk and a danger to himself and others. Olivia tries to stay strong no matter what because she doesnt want to be weak like her pitiful, child-like mother.

Now, as an adult, Olivia struggles with intimacy in her romantic relationship as she has found a partner who is emotionally immature and self-unaware, just like her father. She works way too many hours, oftentimes missing on sleep or overworking herself into terrible physiological symptoms because of lack of proper rest, an excess of coffee and energy drinks, poor diet, and chronic stress. Its an extension of her history of anorexia and self-mutilation that started in early adolescence as a response to her overwhelming home environment.

Olivia associates things like living a slower, more relaxed, more self-connected life, or even participating in basic self-care, with being weak. She doesnt even consider it as viable options because she doesnt want to feel weak. And so she continues living a life she feels she has no choice but to live in the way its always been.

She doesnt even consider it as viable options because she doesnt want to feel weak. And so she continues living a life she feels she has no choice but to live in the way its always been.

Growing up too fast or being mature beyond your years is often seen as a neutral or even a positive thing. In actuality, it is a psychological prison that the child is put into by their caregivers, where they are expected to be perfect, meet unrealistic standards, or fit a role that doesnt belong to them.

As a result, they develop many devastating problems that they often struggle with for the rest of their lives. Different people experience these things differently, and not everyones story is the same as Olivias, but the underlying tendencies are always the same, and the origins are always the same.

Some argue that all of it makes the person stronger, more mature, but we cant ignore the fact that while some of the qualities the person develops can have positive effects, it fundamentally robs the child of their childhood and innocence. Moreover, you can get the sameand oftentimes much betterpositive results by meeting the childs needs and helping them develop a healthy sense of self-esteem without traumatizing them.

Moreover, you can get the sameand oftentimes much betterpositive results by meeting the childs needs and helping them develop a healthy sense of self-esteem without traumatizing them.

As an adult, the person can finally start identifying the origins of these issues and working on them to finally become free of them.

Kids getting older younger: Are children growing up too fast?

Loading

Family Tree | How We Live

(Image credit: Getty Images)

By Katie Bishop24th March 2022

Social media, pampering parents, increased pressure to succeed – ‘kids these days’ deal with a lot. But is it making them grow up faster or slower than previous generations?

K

Kids these days don’t get to be kids anymore, say the adults who remember a childhood free from the rules, oversight and digital pressures today’s young people navigate. In some ways, it may be true. The average parent allows their child a smartphone at age 10, opening up a world inaccessible to previous generations, with unlimited access to news, social media and other privileges previously reserved for adults, forcing them into emotional maturity before they reach adulthood.

There’s a term for it: ‘KGOY’ or ‘kids getting older younger’, meaning children are more savvy than previous generations.

Rooted in marketing, the idea is because of KGOY, kids have greater brand awareness, so products should be advertised to children rather than their parents. The theory has been around since the noughties, and ever since, experts have attempted to prove out the early demise of childhood by pointing to causes ranging from the age at which they get a smartphone, to the fact that kids are now watching more adult television programmes, to the problem of teenage girls being pressured to think about their appearance due to greater exposure to beauty ideals on social media.

Yet though many worry that kids may seem to be growing up too quickly, there’s also evidence that they could, in fact, be maturing more slowly. Gen Z are consistently reaching traditional markers of adulthood such as finishing education and leaving home later than previous generations, and studies have shown that teenagers are engaging in ‘adult’ activities such as having sex, dating, drinking alcohol, going out without their parents and driving much later than previous generations.

Technology may be exposing kids to more, making them intellectually savvier. Yet whether they are actually growing up more quickly may be a matter of perspective. It may also be time to update what we think of as the milestones of maturation, and what it really means to grow up fast.

"Children can communicate with strangers without supervision, which leads to an increased risk of cyberbullying or adult conversations" – Willough Jenkins (Credit: Getty Images)

Family Tree

This story is part of BBC's Family Tree series, which examines the issues and opportunities parents, children and families face today – and how they'll shape the world tomorrow. Find more on BBC Future.

What is childhood?

To understand how we measure growing up, it’s important to think about what most people mean by “childhood” and “adulthood”. Excluding biological measures such as when children hit puberty, our understanding of childhood is largely a social construction. People have different views of what it means depending on when and where they’ve grown up, making it difficult to measure or quantify.

People have different views of what it means depending on when and where they’ve grown up, making it difficult to measure or quantify.

In most countries, people are considered adults from the age of 18, but this varies. In Japan, you are legally a child until you are 20, while in other countries such as Iran, individuals as young as nine years old can be treated as adults in law. Definitions of childhood have also varied historically: in the 19th Century, it was common for children under the age of 10 to work, and the idea of being a “teenager” didn’t really exist until the 1940s. Before then, adolescents were simply seen to transition straight from childhood to adulthood.

How, then, do we understand the idea of growing up more quickly – and is it really the case? “The basic stages of children’s development aren’t changing,” says Shelley Pasnik, senior vice president and director of the Center for Children and Technology, a research group based at the Education Development Center, New York. “The external world is constantly shifting, but children’s cognitive and emotional milestones stay the same.

“The external world is constantly shifting, but children’s cognitive and emotional milestones stay the same.

And Pasnik points out, it’s difficult to measure and quantify the idea of “growing up” in a social and cultural sense. There are so many cross-cultural, linguistic and developmental aspects to childhood that it’s almost impossible to pinpoint any one thing as being the primary influence on how quickly children grow and age.

There’s also evidence people tend to idealise their own childhood, imagining it as a more carefree and happy time. It’s possible adults who complain that children today are maturing more rapidly may well be comparing them to a skewed and nostalgic view of their own youth that doesn’t quite compare to reality.

‘Media-delivered ideas’

“What has changed is [kids’] exposure to information,” says Pasnik, “through video platforms to caregiver phones; social media platforms and interactive speakers with unlimited capacity to push content. ” Children are now constantly getting what Pasnik calls “media-delivered ideas” – content aimed at adults and viewed mostly over the internet – much sooner than previous generations.

” Children are now constantly getting what Pasnik calls “media-delivered ideas” – content aimed at adults and viewed mostly over the internet – much sooner than previous generations.

“There is increased exposure to violent or sexual content at a younger age, which causes a desensitisation and normalisation, because children’s brains aren’t fully developed to process this in a way that an adult brain can,” says Dr Willough Jenkins, an inpatient director of psychiatry at Rady Children’s Hospital, San Diego. “Of course, part of the exposure is to other people, too. Children can communicate with strangers without supervision, which leads to an increased risk of cyberbullying or adult conversations that they are not equipped to handle.”

All of this, says Pasnik, can lead to children confronting adult realities before they are developmentally ready to do so – something that is often interpreted as ‘growing up too quickly’.

Jenkins is quick to point out, however, that technology is neither bad nor good, and that there’s plenty of scaremongering around youth’s increased access to social media. It’s an oft-cited anecdote that in previous generations parents worried about their children watching television, and now social media has become the new societal ill for people to fear.

It’s an oft-cited anecdote that in previous generations parents worried about their children watching television, and now social media has become the new societal ill for people to fear.

In fact, exposure to content not available to previous generations can be a good thing. Technology enables children to independently seek knowledge and to think critically, due to their access to a wider range of sources. For children in remote areas, the ability to find more knowledge and social connections outside their immediate family can be invaluable, as can accessing support and community for minority groups.

Or staying young longer?

Technology is far from the only social force affecting how children develop, and at what pace. Over the past few decades, parenting has become more intensive in the US and many other countries, and children today can expect more structured play, extracurricular activities and parental supervision than previous generations.

The topic of how this affects children is hotly debated – one argument is that heightened expectations placed on children to optimise their time in adult-like ways lead to unnecessary stress (and a loss of an important, carefree stage of childhood), while another argument is that they lead to a generation of pampered young adults unable to think for themselves (and a prolonged and unhealthy childhood).

Experts say technology is neither bad nor good, and that there’s plenty of scaremongering around youth’s increased access to social media (Credit: Getty Images)

“There’s been quite a bit of discussion especially in recent years, about children’s lives becoming more institutionalised and controlled,” says William Corsaro, a professor emeritus of sociology at Indiana University. He points to hovering parents and children’s involvement in extracurricular activities and lessons outside school, and to “overstated” fears about children’s safety and lower birth rates (meaning fewer at-home playmates) as factors that make children mature more slowly.

This theory is echoed by Jean Twenge in her 2017 book iGen. Based on a survey of 11 million US-based young people, Twenge argued that kids born after 1995 are, contrary to much popular wisdom, growing up more slowly, engaging in milestones traditionally considered “adult” far later than their older counterparts.

This is, in part, because smartphones allow children to socialise from their own home, making them less likely to engage in activities such as drinking with peers or sex, but she also points to an evolutionary idea known as ‘life history theory’, which classifies maturation of species into “slow” and “fast” strategies – the safer the environment, the more slowly they have to mature.

Today, in an age of low birth-rates and high life-expectancies, children tend to be closer to their parents and grow up in a safer environment, and thus can mature more slowly. This means that they aren’t pushed towards independence in the same way that children growing up in a fast maturation environment – what previous generations experienced – might be.

Although something of a wildcard, the pandemic also seems to be exacerbating this trend. Children stayed at home instead of going to school, weren’t able to travel to attend university and were furloughed from the jobs that offered a first taste of independence. By most traditional measures they were unable to grow up at the rate that children just a few years ahead of them had done – yet by other measures they were exposed to uncomfortable truths and social responsibilities such as mask-wearing that forced them to confront the adult world more quickly.

A matter of perspective

Though evidence indicates that in a cultural and social sense children aren’t growing up any more quickly than they ever have, this may be to do with how we understand what it means to grow up.

Viewed one way, children really are growing up more slowly, seemingly kept young by a socially distanced and digital world where their parents are their closest real-life companions. Viewed another way, children are simply showing how it looks to mature in today’s world. In fact it could be easy to argue that a broader view of life outside a hometown and local friendship circles given by technology, or an ability to navigate an online world, is just as valid a set of milestones and markers of growing up as having sex, drinking, driving and moving out of the family home.

Ultimately there are many factors that influence the rate at which children mature, and the circumstances are highly individual. Our understanding of where childhood ends and adulthood begins – and the line that separates them – is blurry, and subjective. Society isn’t static – it’s constantly evolving, and so what childhood looks and feels like is constantly evolving too. Getting ‘older’ might seem more complicated these days, but kids don’t know the difference, just as their parents didn’t know a life without the internet or television or telephones – or whatever it was their own parents worried was making them grow up too fast or slow.

Additional reporting by Jessica Gross

;Growing up... Or maybe not?

Know thyself A man among men

“How and when did I become an adult? I don't have the slightest idea! Although I consider myself neither a child nor an infantile, writes the philosopher André Comte-Sponville. But this transition happened very gradually and imperceptibly. It was not an event, but a process, work, a long recovery. I never felt that childhood is a happy time. To become an adult was to finally choose happiness as opposed to childhood.

Perhaps we want to leave our childhood behind. But are we ready to be adults? Which of us (no matter how old we are) is not sometimes seized by the fear of not coping, not being able to stand up for ourselves, the desire to hide under the covers? Aren't adults turning into an endangered species, into a club that fewer people want to join? Is this surprising in our time, when seriousness and maturity are not highly valued?

Limits of life

Adulthood is, of course, a fact of personal biography, an inner feeling that can come at any moment. Public opinion tends to suggest that we become adults between 16 and 24 years old.

Public opinion tends to suggest that we become adults between 16 and 24 years old.

“In general, for the majority of our fellow citizens, adulthood lasts from 16 to 60 years old,” explains sociologist Alexei Levinson. “These boundaries roughly coincide with obtaining a matriculation certificate at the beginning and a pension certificate (for women) at the end.” True, 29% of young people aged 18 to 26 do not consider themselves adults, and in the next age group (26-35) there are also quite a few of them - 10% 1 .

But there is another perception, less tied to passport age. “Now youth has significantly supplanted adulthood, and until the age of 20 teenagers are considered children,” notes social psychologist Margarita Zhamkochyan. - Before our eyes actively, I would even say aggressively, due to adulthood, youth is lengthening. Many predict the gradual disappearance of this concept in general: adults do not age, children do not grow up.

Advertising relentlessly appeals to young people, and it has gotten to the point where young people have become the main reference group. Creative advertising people living in the artificial world that Frédéric Beigbeder described in the bestseller "99 francs" and Victor Pelevin in "Generation P" find it hard to get used to the idea that purchasing power is now shifting more and more to older people. age.

Creative advertising people living in the artificial world that Frédéric Beigbeder described in the bestseller "99 francs" and Victor Pelevin in "Generation P" find it hard to get used to the idea that purchasing power is now shifting more and more to older people. age.

One of the three states of our "I"

Parent, Adult, Child - transactional analysis states that these three are present in each of us. Here is what the founder of this direction of psychotherapy, Eric Berne, says:

“The adult state of the “I” is essentially nothing but a computer. This is the rational and logical part of the personality, occupied mainly with data processing, like a large electronic brain; feelings and emotions thus have nothing to do with the Adult.

We see the Adult when a scientist presents his findings to a group of colleagues, or when a housewife checks her bank account. The adult is the one who works. The mental process required for a carpenter to hammer in a nail is an Adult's responsibility.

But when he misses and bruises his finger, the Adult gives way to another state of "I". It is not always, however, best to be in the adult state of "I"; at parties it is in most cases painful.

Confusion of landmarks

Are we able to give an exact definition of an adult ourselves? Until we grow up, he appears to us as a kind of "man in a case" - a reasonable, but boring character, embodying rules, restrictions, prohibitions.

For example, Pippi Longstocking from Astrid Lindgren's children's book thinks so: “Adults never have real fun. And what are they doing: boring work or fashion, and they only talk about calluses and income taxes ... And they also spoil their mood because of all sorts of stupid things ... "

Or does being an adult have its own joys, its own harmony? “An adult is one who does not need parents,” said the Hindu mystic Osho. - An adult is one who does not need to cling to anyone and rely on anyone. An adult is someone who is happy alone with himself.

André Comte-Sponville's definition: "Growing up means being faithful to childhood and at the same time giving up the desire to remain forever in childhood."

This rejection is not easy for many of us. Before our eyes, the generally accepted boundaries between teenagers and “young adults” who continue to listen to the same music, wear the same jeans and sneakers are disappearing ... Children increasingly cannot afford to leave their parental home due to the high cost of housing or soon return to their native nest.

In the meantime, many adults continue to receive financial assistance from their parents, because they study longer and start working later. And why rush when, according to many, life is just beginning at 40?

Take reality into account

A century ago, a child had no recognized status. Apprentices of about eight or ten years of age were in many ways adult. After all, the only way to express yourself was to enter the circle of adults, and as early as possible. Now everything is practically the opposite: the young are considered a privileged social group.

Now everything is practically the opposite: the young are considered a privileged social group.

The status of an adult is either devalued or, conversely, becomes unattainable. The road of adult life passes through the acceptance of a reality (far from our wishes) and leads to the horizon, beyond which is death. And many would prefer to avoid entering this path for as long as possible. After all, giving up dreams, carelessness and simple joys of childhood is not a very attractive program.

We feel mature when an important event happens

When does this transition take place, which we usually realize after the fact? It seems to be later and later, after thirty, and sometimes closer to fifty. However, it all depends on the circumstances.

“I began to consider myself an adult very early, from the age of seven, and I stopped being one long ago,” admits neuropsychologist Boris Tsiryulnik. He lost his relatives (and he himself was miraculously saved) in 1942. Much later, when he got married and became a father, he "understood that life is a huge game and in this mortal world there is nothing more important than playing."

Much later, when he got married and became a father, he "understood that life is a huge game and in this mortal world there is nothing more important than playing."

The onset of adulthood is an event in a personal history, which is different for everyone. Often we feel that we have matured when an important event happens - the birth of a child or the death of a loved one. Contrary to popular belief, women are more willing than men to accept their adult status.

The ideal adult is one who has finally managed to know and accept himself

everything you need,” recalls 36-year-old Olga. A baby waits for the world to fulfill his every desire, so an adult knows that he will have to give his child his attention, time, money, and even his life ...

Sometimes, however, the feeling of maturity is deceptive. “Over the years, I realized that I considered myself an adult much earlier than I learned adult behavior,” says journalist and founder of Psychologies Jean-Louis Servan-Schreiber. - If in relation to childhood I do not feel any nostalgia, it is because then I was dependent, and today I love my independence and freedom of action too much.

- If in relation to childhood I do not feel any nostalgia, it is because then I was dependent, and today I love my independence and freedom of action too much.

I felt that I was reaching maturity when I stopped being afraid of my shortcomings, other people's opinions, I stopped being afraid to tell the truth, to be afraid of the traps of life, and death too. And I learned that the ideal adult is the one who has finally managed to know and accept himself. And this guarantees us that we will never become fully grown…”

Is it ideal?

It is sometimes thought that the goal of psychoanalysis is to make adults who are not yet fully grown up, because Freud wanted to free us from the painful captivity of childhood. The writer Oscar Wilde said it beautifully: “Little children love their parents, then they judge them; sometimes they forgive them. The teenager is the one who judges; the adult is the one who forgives."

This does not mean that we should or can be adults all the time. A solid, "solid" adult exists only in the child's imagination. This illusion now passes in children earlier and earlier, as well as the desire to grow up. Face to face with life, we quickly realize that it is equally impossible to refuse to be an adult, nor to become one completely.

A solid, "solid" adult exists only in the child's imagination. This illusion now passes in children earlier and earlier, as well as the desire to grow up. Face to face with life, we quickly realize that it is equally impossible to refuse to be an adult, nor to become one completely.

Being an adult means being able to drop armor

And this is only for the best. Isn't it all about personal development, to know yourself for real, to be able to combine responsibility and carelessness, seriousness and play, openness to others and the necessary distance?

“From personal perspectives, only old age or nothingness lies ahead for an adult,” says André Comte-Sponville. “But that doesn't bother him too much. He has something much more urgent. More important. There is something present that goes on and on. There is a reality that remains."

After all, being an adult also means being able to shed armor, open up, be real. And this is not easy not only for each of us, but also for our society, says film director Pavel Lungin: “I have not matured yet and I hope to remain a child until the end of my life. But our society is maturing.

And this is not easy not only for each of us, but also for our society, says film director Pavel Lungin: “I have not matured yet and I hope to remain a child until the end of my life. But our society is maturing.

For the previous 10 years it was a child, and we built relations with the authorities according to the principle: “Daddy, punish me, I'm bad! Dad, praise, give me candy! Now we are teenagers. The main questions for a teenager are: “Dad, do you respect me?! Why do you lie to me?!" But there is no program - what kind of program can a teenager have? Now we need to move on - to adulthood.

1 Poll of the Public Opinion Foundation, 2010, fom.ru

New on the website

“Repairs in the nursery caused quarrels with my husband. How to find a compromise?

“After two years of relationship, I lost attraction to the guy. What does this have to do with it?

Wealth changes women: we publish unusual results of a new study

“A miniskirt is a provocation?”: What does clothes really mean? child sexual abuse

Why we get into emotional swings

How to successfully deal with insecure people: 7 tips that are easy to apply

Why are we so poor? Part 1. How family history affects finances

How family history affects finances

10 films for those who do not want to grow up

10 films for those who do not want to grow up-

thirty 235759

-

1950

-

1 1797

-

4730

-

74 405321

Christopher Robin

Photo: film. ru

ru

One Hundred Days After Childhood

Photo: knigi516.ru

"Big and kind giant"

Photo: film.ru

Beauty and the Beast

Photo: zen.yandex.ru

The Jungle Book

Photo: lostpic.net

Alice in Wonderland

Photo: zen. yandex.com

yandex.com

Unusual concerts in the Peter and Paul Cathedral. 12+

Jazz, medieval and classical music on the organ. Advertising. IP Romanenko Oleg Ivanovich. TIN 771471613250

See schedule

"The Adventures of Paddington-2" / Paddington 2 (2017) 6+

A family comedy directed by Paul King based on a series of children's novels by Michael Bond about the adventures of Paddington Bear. The furry visitor from Peru has successfully settled into the home of the Brown family, but has not lost his ability to get involved in incredible adventures. This time, the source of all the trouble was an old book stolen by someone from Mr. Gruber's antique shop.

This time, the source of all the trouble was an old book stolen by someone from Mr. Gruber's antique shop.

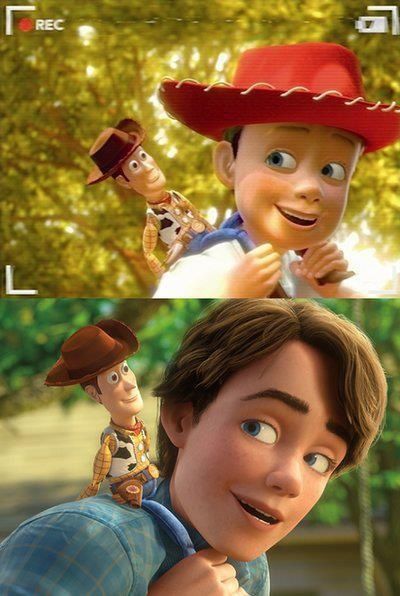

"Christopher Robin" / Christopher Robin (2018) 6+

Life-affirming family fantasy about the grown-up hero Alan Milne. Christopher Robin grew up, he had a family and a serious job that takes up all his free time, and he forgot to think about childhood friends. But Winnie's teddy bear will appear on a secluded bench in a London square at the most unexpected moment - and will carry him into the Hundred Acre Forest. The adult Christopher Robin was played by Ewan McGregor.

The adult Christopher Robin was played by Ewan McGregor.

"One Hundred Days After Childhood" (1975) 12+

Mitya Lopukhin will remember this summer for the rest of his life. It marked the end of childhood and gave the boy his first love and first disappointment. In this film, director Sergei Solovyov groped for topics that later turned into a trilogy: “One Hundred Days of Childhood”, “Rescuer”, “Heir in a Straight Line”.

"Big and kind giant" / The BFG (2016) 6+

A family fantasy film from Hollywood director Steven Spielberg (ET, Schindler's List), based on the book of the same name by Roald Dahl. Waking up in the middle of the night, an inquisitive orphan named Sophie accidentally witnesses the appearance of a huge giant who, according to urban legends, takes naughty children to his country. This happened to the young heroine, but, fortunately, the 15-meter giant turned out to be friendly and not at all dangerous. The world premiere took place on May 14, 2016 as part of the Cannes Film Festival.

Waking up in the middle of the night, an inquisitive orphan named Sophie accidentally witnesses the appearance of a huge giant who, according to urban legends, takes naughty children to his country. This happened to the young heroine, but, fortunately, the 15-meter giant turned out to be friendly and not at all dangerous. The world premiere took place on May 14, 2016 as part of the Cannes Film Festival.

The Jungle Book (2016) 12+

Disney animated adaptation of Kipling's collection of short stories, remake of the 1967 cartoon of the same name. The protagonist is an Indian boy Mowgli, adopted into a family of wild wolves and brought up according to the laws of the jungle. But the irreconcilable enmity with the evil Sher Khan forces him to leave the pack and embark on a journey full of unexpected discoveries and fateful meetings. In the original version, Scarlett Johansson (Kaa), Christopher Walken (King Louie), Bill Murray (Balu) and others gave voices to the heroes of the animated film.

The protagonist is an Indian boy Mowgli, adopted into a family of wild wolves and brought up according to the laws of the jungle. But the irreconcilable enmity with the evil Sher Khan forces him to leave the pack and embark on a journey full of unexpected discoveries and fateful meetings. In the original version, Scarlett Johansson (Kaa), Christopher Walken (King Louie), Bill Murray (Balu) and others gave voices to the heroes of the animated film.

"Alice in Wonderland" / Alice in Wonderland (2010) 12+

Tim Burton's fantasy adventure film based on the works of Lewis Carroll. In the center of the fairy tale plot, familiar from childhood, is the story of the grown-up girl Alice. In an attempt to escape from an imposed marriage, the 19-year-old heroine finds herself in a beautiful but gloomy kingdom, headed by a fantastically cruel and domineering Red Queen. The film won two Academy Awards in 2011.

In the center of the fairy tale plot, familiar from childhood, is the story of the grown-up girl Alice. In an attempt to escape from an imposed marriage, the 19-year-old heroine finds herself in a beautiful but gloomy kingdom, headed by a fantastically cruel and domineering Red Queen. The film won two Academy Awards in 2011.

Mary Poppins Returns (2018) 6+

The Banks children have grown up a long time ago, and Michael even got his own children. So, the new generation is waiting for a meeting with the most magical nanny in the world.

So, the new generation is waiting for a meeting with the most magical nanny in the world.

Miss Peregrine's Home for Peculiar Children (2016) 16+

Fantasy adventure directed by Tim Burton, best known for his films Dark Shadows, Edward Scissorhands and Big Fish. The plot revolves around sixteen-year-old boy Jacob Portman, who accidentally ends up on an island where children with supernatural powers live. All of them are under the supervision of the strict Miss Peregrine, from whom the young hero will learn the secret of his origin. The film is based on the novel of the same name by Ransom Riggs.

The film is based on the novel of the same name by Ransom Riggs.

"I fight the giants" / I Kill Giants (2017) 12+

Fantastic film adaptation of the comic book series of the same name by Joe Kelly about a young girl Barbara Thompson with unusual abilities. She knows how to be transferred to the world of giants, eager to exterminate people. Despite the skepticism of others who believe that Barbara's stories are nonsense and an attempt to escape from reality, the girl does not give up and is ready to fight her enemies in order to save humanity.

"Beauty and the Beast" / Beauty and the Beast (2017) 16+

Fantasy film produced by Walt Disney Pictures, which is a remake of the 1991 Disney cartoon of the same name. The search for the missing father leads the beautiful girl Belle to a mysterious castle, where the enchanted prince lives, whom everyone fears and hates. The guest asks the host to let go of his beloved dad, in return promising to stay in the palace forever. The beauty was played by the star of the Potter series Emma Watson, and Dan Stevens hid behind the mask of the monster.