Cbt for body dysmorphia

A Therapist’s Guide for the Treatment of Body Dysmorphic Disorder

by Andrea Hartmann, PhD, Jennifer Greenberg, PsyD, & Sabine Wilhelm, PhD

Overview of CBT for BDD and its empirical support

Most patients with body dysmorphic disorder (BDD) do not seek psychiatric/psychological care, but look for costly surgical, dermatologic, and dental treatments to try to fix perceived appearance flaws (e.g., Phillips, et al., 2000), that often worsen BDD symptoms (e.g., Sarwer & Crerand, 2008). Two empirically-based treatments are available for the treatment of BDD: serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SRIs) (click here to learn more about medication treatment for BDD) and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT). Several studies have found CBT to successfully reduce BDD severity and related symptoms such as depression (McKay, 1999; McKay et al., 1997; Rosen et al., 1995; Veale et al., 1996; Wilhelm et al., 1999; Wilhelm et al., 2011; Wihelm et al., 2014).

CBT models of BDD (e. g., Veale, 2004; Wilhelm et al., 2013) incorporate biological, psychological, and sociocultural factors in the development and maintenance of BDD. The model proposes that individuals with BDD selectively attend to minor aspects of appearance as opposed to seeing the big picture. This theory is informed by clinical observations and neuropsychological (Deckersbach et al., 2000) and neuroimaging findings (Feusner et al., 2007; Feusner et al., 2010). Individuals with BDD also overestimate the meaning and importance of perceived physical imperfections. For example, when walking into a restaurant, a patient with BDD who has concerns about his nose might think, “Everyone in the restaurant is staring at my big, bulbous nose.” Patients are also more likely misinterpret minor flaws (e.g., perceived asymmetry) as major personal flaws (e.g., “If my nose is crooked, I am unlovable”) (Buhlmann et al., 2009; Veale, 2004). Self-defeating interpretations foster negative feelings (e.g., anxiety, shame, sadness) that patients try to neutralize with rituals (e.

g., excessive mirror checking, surgery seeking) and avoidance (e.g., social situations). Because rituals and avoidance may temporarily reduce painful feelings they are negatively reinforced and thus maintain maladaptive beliefs and coping strategies.

g., excessive mirror checking, surgery seeking) and avoidance (e.g., social situations). Because rituals and avoidance may temporarily reduce painful feelings they are negatively reinforced and thus maintain maladaptive beliefs and coping strategies.

CBT for BDD typically begins with assessment and psychoeducation, during which the therapist explains and individualizes the CBT model of BDD. In addition, CBT usually includes techniques such as cognitive restructuring, exposure and ritual prevention, and relapse prevention. Some CBT for BDD includes perceptual (mirror) retraining. A modular CBT manual (CBT-BDD; Wilhelm et al., 2013) has been developed to target core symptoms of BDD and to flexibly address symptoms that affect some, but not all, patients. Additional modules might address depression, skin picking/hair plucking, weight and shape concerns, and cosmetic surgery seeking (e.g. Wilhelm et al., 2013). CBT-BDD has been shown to be effective in open (Wilhelm et al., 2011) and randomized control trials (Wilhelm et al. , 2014).

, 2014).

Assessment, motivational assessment, and psychoeducation

CBT begins with an assessment of BDD and associated symptoms. Clinicians should inquire about BDD-related areas of concern, thoughts, behaviors, and impairment. It is important to ask specifically about BDD symptoms as it often goes undetected in clinical settings (e.g., Grant et al., 2002) due to embarrassment and shame. Clinicians should be aware of clues in clinical presentation such as appearance (e.g., scarring due to skin picking) and behaviors (e.g, wearing camouflage), ideas or delusions of reference (e.g., feelings that people talk about them, stare at them), panic attacks (e.g., when looking into the mirror), depression, social anxiety, substance abuse and suicidal ideation as well as being housebound. Additionally, differential diagnosis should be clarified in a structured clinical interview including eating disorders, obsessive compulsive disorder, depression, and social phobia. Given the high rates of depression and suicidality in BDD, it is critical to evaluate depression and suicidality at the onset and regularly throughout treatment.

Given the high rates of depression and suicidality in BDD, it is critical to evaluate depression and suicidality at the onset and regularly throughout treatment.

For patients reluctant to try CBT or who hold highly delusional appearance beliefs, the therapist should incorporate techniques from motivational interviewing (MI; Miller & Rollnick, 2003) that have been adapted for the use in BDD (Wilhelm et al., 2013). In a first step, the therapist should empathize with the patient’s body image-related distress instead of directly questioning the validity of the beliefs (“I see that you really suffer because you are so worried because of the way you look. Let’s try to reduce this distress.”). Also, non-judgmental Socratic questioning can be employed (“What might be the advantages of trying CBT for BDD?“). The therapist can also discuss the discrepancy between BDD symptoms and the patient’s goals (“What should your life look like 10 years from now?“). In particular, for patients with poor insight it might be more helpful to address the usefulness of beliefs instead of the validity (e. g., “Are your beliefs preventing you from participating in activities you enjoy?“). MI strategies often need to be used throughout treatment.

g., “Are your beliefs preventing you from participating in activities you enjoy?“). MI strategies often need to be used throughout treatment.

Next, the therapist should provide psychoeducation about BDD, such as its prevalence, common symptoms, and differences between body image and appearance. Then, the therapist and patient develop an individualized model of BDD based on the patient’s specific symptoms. Such models include theories of how body image problems develop (including biological, sociocultural and psychological factors) (Wilhelm et al., 2013). It is important to explore factors in the patient’s current life that are serving to maintain body image concerns, including triggers for negative thoughts about appearance, interpretations of these thoughts, emotional reactions, and (maladaptive) coping strategies. This will help to inform the treatment and which specific modules are needed.

Cognitive strategies

Cognitive strategies include identifying maladaptive thoughts, evaluating them, and generating alternative thoughts. Therapists introduce patients to common cognitive errors in BDD, such as “all-or-nothing thinking” (e.g., “This scar makes me completely disgusting”) or “mindreading” (e.g., “I know my girlfriend wishes I had better skin”). Patients are then encouraged to monitor their appearance-based thoughts in and outside of the session and identify cognitive errors (e.g., “Why am I so nervous about riding the subway?” “I know others are staring at my nose and thinking how ugly it looks”. Cognitive distortion: “personalization”). After the patient has gained some skill in identifying maladaptive thoughts and cognitive errors, the therapist can start to evaluate thoughts with the patient (e.g., Rosen et al., 1995; Veale et al., 1996; Wilhelm et al., 2013). While it is often helpful to evaluate the validity of a maladaptive thought (e.g., “What is the evidence others are noticing or judging my nose?”), it can also be beneficial to examine its usefulness (e.g. “Is it really helpful for me to think that I can only be happy if my nose were straight?”; Wilhelm et al.

Therapists introduce patients to common cognitive errors in BDD, such as “all-or-nothing thinking” (e.g., “This scar makes me completely disgusting”) or “mindreading” (e.g., “I know my girlfriend wishes I had better skin”). Patients are then encouraged to monitor their appearance-based thoughts in and outside of the session and identify cognitive errors (e.g., “Why am I so nervous about riding the subway?” “I know others are staring at my nose and thinking how ugly it looks”. Cognitive distortion: “personalization”). After the patient has gained some skill in identifying maladaptive thoughts and cognitive errors, the therapist can start to evaluate thoughts with the patient (e.g., Rosen et al., 1995; Veale et al., 1996; Wilhelm et al., 2013). While it is often helpful to evaluate the validity of a maladaptive thought (e.g., “What is the evidence others are noticing or judging my nose?”), it can also be beneficial to examine its usefulness (e.g. “Is it really helpful for me to think that I can only be happy if my nose were straight?”; Wilhelm et al. , 2013), particularly for patients with poor insight. Once the patient has become adept at identifying and restructuring automatic appearance-related beliefs, deeper level (core) beliefs should be addressed. Common core beliefs in BDD include I’m unlovable” or “I’m inadequate” (Veale et al., 1996). These deeply held beliefs filter a patient’s experiences, and if not addressed, can thwart progress and long-term maintenance of gains. Core beliefs often emerge during the course of therapy. They can also be identified using the downward arrow technique, which involves the therapist asking repeatedly about the worst consequences of a patient’s beliefs (e.g., for the thought “People will think that my nose is huge and crooked,” the therapist would ask the patient, “What would it mean if people noticed your nose was big/crooked?”) until the core belief is reached (e.g., “If people noticed that my nose was big/crooked, they wouldn’t like me and this would mean that I am unlovable.”; Wilhelm et al.

, 2013), particularly for patients with poor insight. Once the patient has become adept at identifying and restructuring automatic appearance-related beliefs, deeper level (core) beliefs should be addressed. Common core beliefs in BDD include I’m unlovable” or “I’m inadequate” (Veale et al., 1996). These deeply held beliefs filter a patient’s experiences, and if not addressed, can thwart progress and long-term maintenance of gains. Core beliefs often emerge during the course of therapy. They can also be identified using the downward arrow technique, which involves the therapist asking repeatedly about the worst consequences of a patient’s beliefs (e.g., for the thought “People will think that my nose is huge and crooked,” the therapist would ask the patient, “What would it mean if people noticed your nose was big/crooked?”) until the core belief is reached (e.g., “If people noticed that my nose was big/crooked, they wouldn’t like me and this would mean that I am unlovable.”; Wilhelm et al. , 2013). Negative core beliefs can be addressed through cognitive restructuring, behavioral experiments, and strategies such as the self-esteem pie, which helps patients learn to broaden the basis of their self-worth to include non-appearance factors (e.g., skills, achievements, moral values).

, 2013). Negative core beliefs can be addressed through cognitive restructuring, behavioral experiments, and strategies such as the self-esteem pie, which helps patients learn to broaden the basis of their self-worth to include non-appearance factors (e.g., skills, achievements, moral values).

Exposure and ritual prevention (E/RP)

Prior to beginning E/RP, the therapist and patient should review the patient’s BDD model to help identify the patient’s rituals (e.g., excessive mirror checking) and avoidance behaviors (e.g., avoiding riding the subway) and discuss the role of rituals and avoidance in maintaining his symptoms. The therapist and patient jointly develop a hierarchy of anxiety provoking and avoided situations. Patients often avoid daily activities, or activities that could reveal one’s perceived flaw, including shopping (e.g., changing in a dressing room), going to the beach, intimate sexual encounters, going to work or class, or accepting social invitations. The hierarchy should include situations that would broaden a patient’s overall social experiences. For example, a patient might be encouraged to go out with friends twice per week instead of avoiding friends on days when he thought his nose looked really “huge.” The first exposure should be mildly to moderately challenging with a high likelihood for success. Exposure can be very challenging for patients, therefore, it is important for the therapist to provide a strong rationale for exposure, validate the patient’s anxiety while guiding him towards change, be challenging and encouraging, be patient and a cheerleader, and quickly incorporate ritual prevention. To reduce rituals, patients are encouraged to monitor the frequency and contexts in which rituals arise. The therapist then teaches patients strategies to eliminate rituals by first learning how to resist rituals (e.g., waiting before checking the mirror) or reduce rituals (e.g., wearing less makeup when out in public). The patient should be encouraged to use ritual prevention strategies during exposure exercises. It is often helpful to set up exposure exercises as a “behavioral experiment” during which they evaluate the validity of negative predictions (e.

For example, a patient might be encouraged to go out with friends twice per week instead of avoiding friends on days when he thought his nose looked really “huge.” The first exposure should be mildly to moderately challenging with a high likelihood for success. Exposure can be very challenging for patients, therefore, it is important for the therapist to provide a strong rationale for exposure, validate the patient’s anxiety while guiding him towards change, be challenging and encouraging, be patient and a cheerleader, and quickly incorporate ritual prevention. To reduce rituals, patients are encouraged to monitor the frequency and contexts in which rituals arise. The therapist then teaches patients strategies to eliminate rituals by first learning how to resist rituals (e.g., waiting before checking the mirror) or reduce rituals (e.g., wearing less makeup when out in public). The patient should be encouraged to use ritual prevention strategies during exposure exercises. It is often helpful to set up exposure exercises as a “behavioral experiment” during which they evaluate the validity of negative predictions (e. g., if I don’t wear my hat, someone will laugh at my thinning hair”). The goal of E/RP is to help patients practice tolerating distress and acquire new information to evaluate their negative beliefs (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

g., if I don’t wear my hat, someone will laugh at my thinning hair”). The goal of E/RP is to help patients practice tolerating distress and acquire new information to evaluate their negative beliefs (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

Perceptual retraining

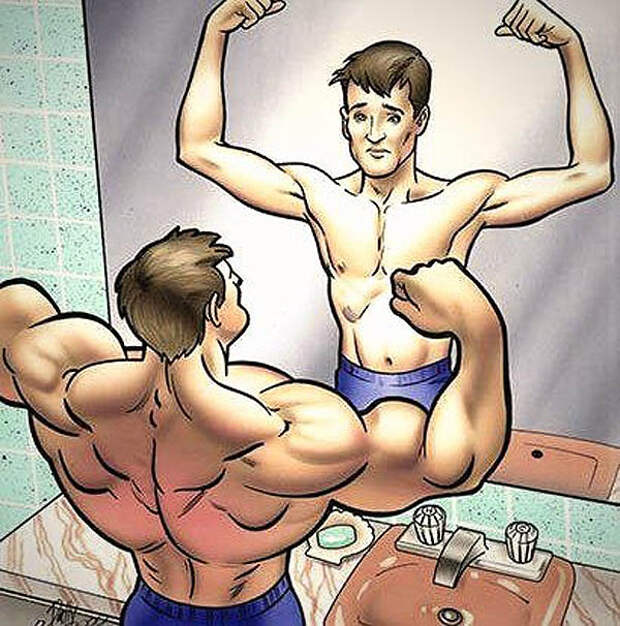

Individuals with BDD often have a complex relationship with mirrors and reflective surfaces. A patient may vacillate between getting stuck for hours in the mirror scrutinizing, grooming, or skin picking, and active avoidance of seeing his reflection. Usually patients focus only on the body parts of concern and get very close to the mirror, which magnifies perceived imperfections and maintains maladaptive BDD beliefs and behaviors. Furthermore, patients tend to engage in judgmental and emotionally charged self-talk (“Your nose looks so disgusting”). Perceptual retraining helps to address distorted body image perception and helps patients learn to engage in healthier mirror-related behaviors (i.e., not getting too close to the mirror, not avoiding the mirror entirely). The therapist helps to guide the patient in describing his whole body (head to toe) while standing at a conversational distance from the mirror (e.g., two to three feet). Instead of judgmental language (e.g., “My nose is huge and crooked.”), during perceptual (mirror) retraining, patients learn to describe themselves more objectively (“There is a small bump on the bridge of my nose”). The therapist encourages the patient to refrain from rituals, such as zoning in on disliked areas or touching certain body parts. Perceptual retraining strategies can also be used to broaden patients attention in other situations in which the patient selectively attends to aspects of their and others’ appearance (e.g., while at work or out with friends). Patients are encouraged to practice attending to other things in the environment (e.g., the content of the conversation, what his meal tastes like) as opposed to his own or others’ appearance (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

The therapist helps to guide the patient in describing his whole body (head to toe) while standing at a conversational distance from the mirror (e.g., two to three feet). Instead of judgmental language (e.g., “My nose is huge and crooked.”), during perceptual (mirror) retraining, patients learn to describe themselves more objectively (“There is a small bump on the bridge of my nose”). The therapist encourages the patient to refrain from rituals, such as zoning in on disliked areas or touching certain body parts. Perceptual retraining strategies can also be used to broaden patients attention in other situations in which the patient selectively attends to aspects of their and others’ appearance (e.g., while at work or out with friends). Patients are encouraged to practice attending to other things in the environment (e.g., the content of the conversation, what his meal tastes like) as opposed to his own or others’ appearance (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

Brief overview over additional modules

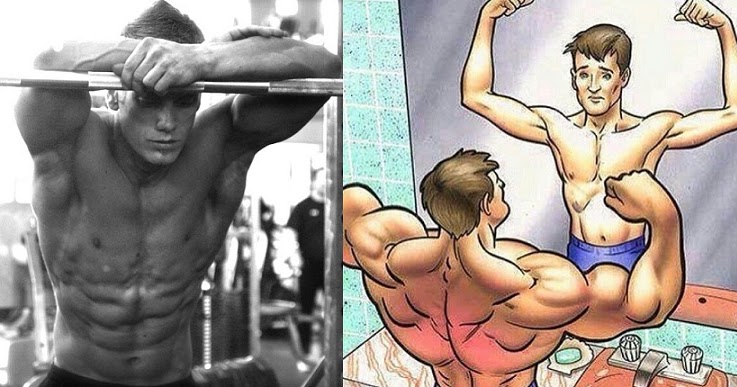

Specific treatment strategies may be necessary to address symptoms affecting some but not all patients including: skin picking/hair pulling, muscularity and shape/weight, cosmetic treatment, and mood management (Wilhelm et al. , 2013). Habit reversal training can be used to address BDD-related skin picking or hair pulling. Patients with significant shape/weight concern, including those suffering from muscle dysmorphia often benefit from psychoeducation and cognitive-behavioral strategies tailored to shape/weight concerns. Therapists can use cognitive and motivational strategies to address maladaptive beliefs about the perceived benefits of surgery while at the same time helping the patient to nonjudgmentally explore the pros and cons of pursuing cosmetic surgery (Wilhelm et al., 2013). Depression is common in patients with BDD and may become treatment interfering (Gunstad & Phillips, 2003). Patients with significant depression can benefit from activity scheduling, as well as cognitive restructuring techniques for more severely depressed patients (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

, 2013). Habit reversal training can be used to address BDD-related skin picking or hair pulling. Patients with significant shape/weight concern, including those suffering from muscle dysmorphia often benefit from psychoeducation and cognitive-behavioral strategies tailored to shape/weight concerns. Therapists can use cognitive and motivational strategies to address maladaptive beliefs about the perceived benefits of surgery while at the same time helping the patient to nonjudgmentally explore the pros and cons of pursuing cosmetic surgery (Wilhelm et al., 2013). Depression is common in patients with BDD and may become treatment interfering (Gunstad & Phillips, 2003). Patients with significant depression can benefit from activity scheduling, as well as cognitive restructuring techniques for more severely depressed patients (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

Relapse Prevention

Treatment ends with relapse prevention focused on consolidation of skills and helping patients plan for the future. Therapists help patients expect and respond effectively to upcoming challenges (e.g., starting college, job interview, dating). Therapists may recommend self-therapy sessions in which patients set time aside weekly to review skills and set upcoming BDD goals. Booster sessions can be offered after treatment ends as a way to periodically assess progress and review CBT skills as needed (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

Therapists help patients expect and respond effectively to upcoming challenges (e.g., starting college, job interview, dating). Therapists may recommend self-therapy sessions in which patients set time aside weekly to review skills and set upcoming BDD goals. Booster sessions can be offered after treatment ends as a way to periodically assess progress and review CBT skills as needed (Wilhelm et al., 2013).

References

Buhlmann, U., Teachman, B. A., Naumann, E., Fehlinger, T., & Rief, W. (2009). The meaning of beauty: implicit and explicit self-esteem and attractiveness beliefs in body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 23, 694-702.

Deckersbach, T., Savage, C. R., Phillips, K. A., Wilhelm, S., Buhlmann, U., & Rauch, S. L. (2000). Characteristics of memory dysfunction in body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of the International Neuropsychology Society, 6, 673-681.

Feusner, J. D., Bystritsky, A., Hellemann, G. , & Bookheimer, S. (2010). Impaired identity recognition of faces with emotional expressions in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatry Research, 179, 318-323.

, & Bookheimer, S. (2010). Impaired identity recognition of faces with emotional expressions in body dysmorphic disorder. Psychiatry Research, 179, 318-323.

Feusner, J. D., Townsend, J., Bystritsky, A., & Bookheimer, S. (2007). Visual information processing of faces in body dysmorphic disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 1417-1425.

Grant, J. E., Kim, S. W., & Crow, S. J. (2001). Prevalence and clinical features of body dysmorphic disorder in adolescent and adult psychiatric inpatients. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 62, 517-522.

Gunstad, J., & Phillips, K.A. (2003). Axis I comorbidity in body dysmorphic disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 44, 270-276.

McKay, D. (1999). Two-year follow-up of behavioral treatment and maintenance for body dysmorphic disorder. Behavior Modification, 23, 620-629.

McKay, D., Todaro, J., Neziroglu, F., Campisi, T., Moritz, E.K., Yaryura-Tobias, J.A. (1997). Body dysmorphic disorder: A preliminary evaluation of treatment and maintenance using exposure with response prevention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 67-70.

Body dysmorphic disorder: A preliminary evaluation of treatment and maintenance using exposure with response prevention. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 35, 67-70.

Miller, W.R. & Rollnick, S. (2002). Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change (2nd edition). New York: Guilford Press.

Phillips, K. A., Dufresne, R. G., Jr., Wilkel, C. S., & Vittorio, C. C. (2000). Rate of body dysmorphic disorder in dermatology patients. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatolology, 42, 436-441.

Phillips, K. A., & Hollander, E. (2008). Treating body dysmorphic disorder with medication: evidence, misconceptions, and a suggested approach. Body Image, 51, 13-27.

Rosen, J.C., Reiter, J., & Orosan, P. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral body image therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 263-269.

Sarwer, D. B., & Crerand, C. E. (2008). Body dysmorphic disorder and appearance enhancing medical treatments. Body Image, 5, 50-58.

Body Image, 5, 50-58.

Veale, D. (2004). Advances in a cognitive behavioural model of body dysmorphic disorder. Body Image, 1, 113-125.

Veale, D., Gournay, K., Dryden, W., Boocock, A., Shah, F., Willson, R. & Walburn, J. (1996).Body dysmorphic disorder: A cognitive behavioural model and pilot randomized control trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 34, 717-729.

Wilhelm, S., Otto, M. W., Lohr, B., & Deckersbach, T. (1999). Cognitive behavior group therapy for body dysmorphic disorder: a case series. Behavior Research and Therapy, 37, 71-75.

Wilhelm, S., Phillips, K. A., Didie, E., Buhlmann, U., Greenberg, J. L., Fama, J. M., Keshaviah, A., & Steketee, G. (2014). Modular Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Body Dysmorphic Disorder: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Behavior Therapy, 45, 314–327.

Wilhelm, S., Phillips, K. A., Fama, J. M., Greenberg, J. L., & Steketee, G. (2011). Modular cognitive-behavioral therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Behavior Therapy, 42, 624-633.

Behavior Therapy, 42, 624-633.

Wilhelm S., Phillips K.A., & Steketee G. (2013). A cognitive behavioral treatment manual for body dysmorphic disorder. New York: Guilford Press.

More Than Alphabet Soup |

Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD)

- Understanding BDD

- Symptoms & Related Disorders

- Treatment

- ACT with CBT

- Resources

Jessica, 16, is overly concerned with the size of her head. She believes it is larger than the average person’s head. She goes out of her way to camouflage her head by wearing glasses and her hair down. In public she is convinced that others are staring at her and reacting with disgust. As a result of her preoccupation and her distress, she avoids school and socializing and prefers to spend her days in her room.

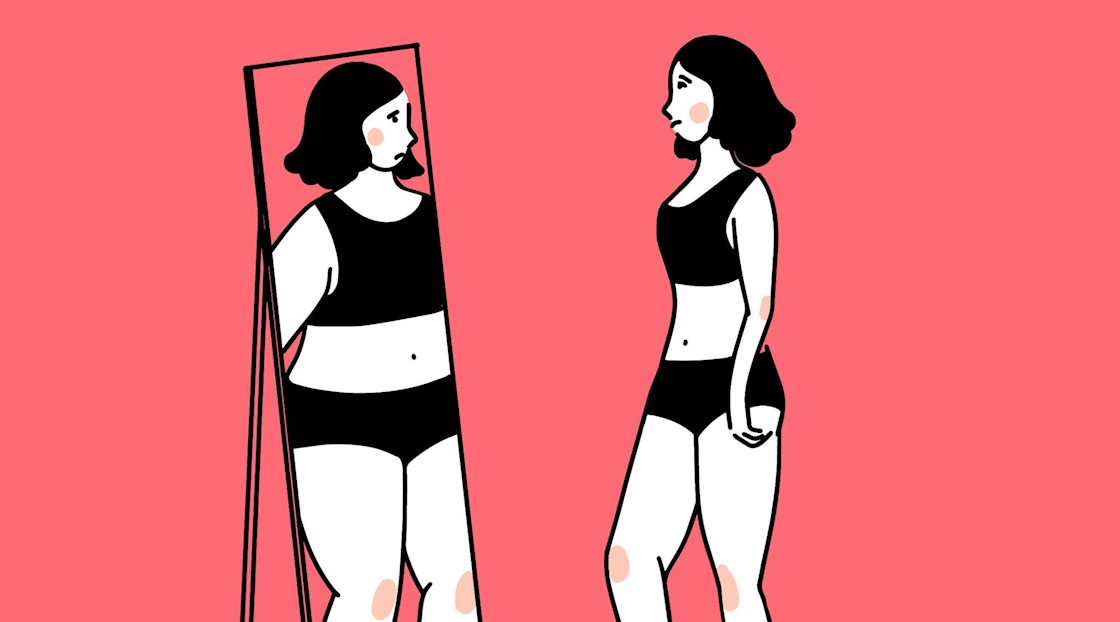

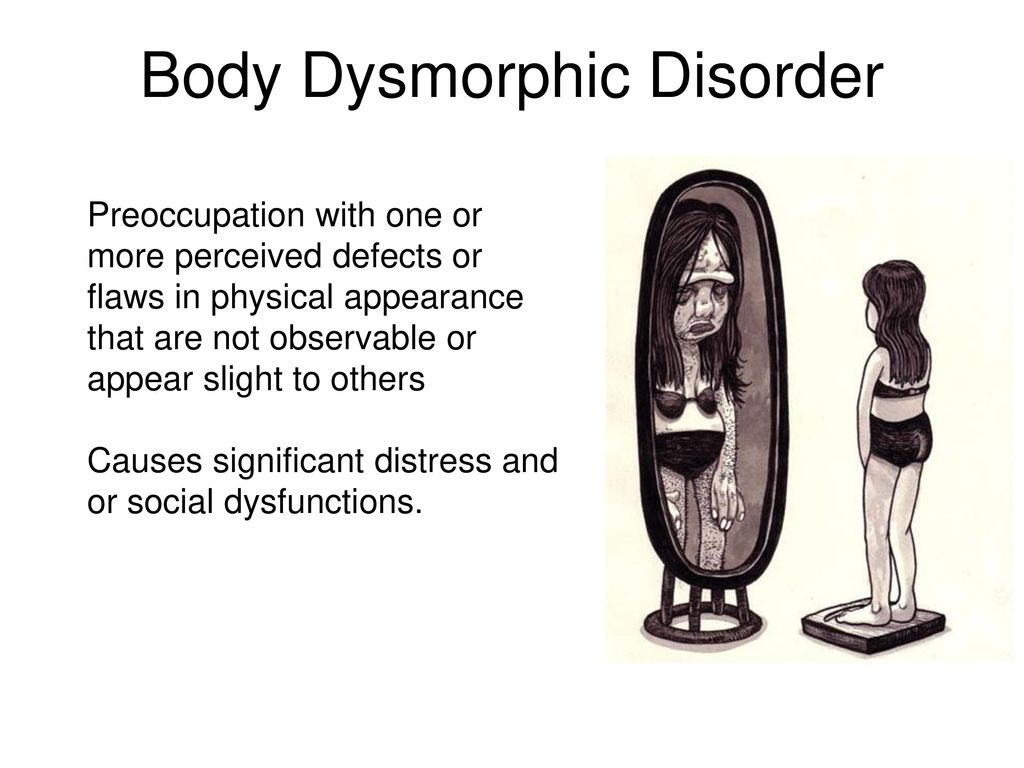

Jessica suffers from body dysmorphic disorder, often referred to as BDD, which is a preoccupation with an imagined or slight defect in appearance.

Treatment

Cognitive-behavioral therapy, or CBT, is the first line of treatment for BDD. This type of treatment typically involves a technique known as exposure and response prevention (ERP).

In BDD, exposure aims to decrease mirror checking, camouflaging, and other compulsive behaviors. It is also intended to prevent behaviors such as avoiding social situations. CBT is effective, but some people with BDD fail to respond. Some improve slightly, and some are unwilling to participate in ERP. For these reasons, it is useful to consider a different approach in conjunction with CBT.

Acceptance and commitment therapy, or ACT, is one such treatment. ACT focuses on tolerating thoughts and symptoms, rather than trying to change, dispute, and generate alternative interpretations to problems. People with resistant BDD may benefit from ACT because it teaches how to tolerate anxiety-provoking situations.

This type of therapy incorporates the core concepts of mindfulness, acceptance, and value-based living.

- Mindfulness: Developing the ability to be present in the moment and the ability to observe without making judgments.

- Acceptance: The ability to distinguish between pain and suffering and being able to tolerate and live with pain.

- Value-based living: The ability to live according to your values and not your symptoms; living fully now instead of waiting to reduce your symptoms

Mindfulness

The mindfulness aspect of ACT entails learning skills that aid in accepting thoughts and feelings. In the case of BDD, you practice the acceptance of thoughts such as “I have a big head” and feelings such as “I am unlovable.” This is achieved by engaging in a variety of mindfulness exercises such as taking a silent walk and simply observing thoughts, feelings, and sensations as they come up. Mindfulness allows you to realize that you can experience many events but that you are never defined by these events.

Acceptance

Many people with BDD experience intense feelings of suffering as a result of their preoccupation. In moments of struggle they avoid and try to control unpleasant thoughts. ACT helps them ride out moments of suffering and struggle.

First it addresses your willingness to experience common symptoms such as unwanted thoughts, images, and situations. Next comes the introduction of the idea that unpleasant internal stimuli are not as harmful as you assume.

With time, you will learn more flexible ways to respond to stressful thoughts that decrease suffering and struggle. ACT focuses on changing your reaction to triggers such as thoughts about your head instead of changing your thoughts about it.

Some people with BDD also suffer from depression. ACT aims to differentiate between a label and a thought.

Label: “I am depressed.”

vs.

Thought: “I am having the thought that I am depressed.”

This helps you learn the difference between a thought and a sense of self. In ACT, it is important to be aware that we are not our thoughts. This process assists in decreasing the emotion attached to such thoughts.

In ACT, it is important to be aware that we are not our thoughts. This process assists in decreasing the emotion attached to such thoughts.

Value-based Living

The third component of ACT involves value-based living. For many with BDD, their appearance is their only value. ACT helps identify other values, which can serve as guides to live your life. Clarification of values involves distilling urges and feelings to see what is truly meaningful to you.

For example, someone with BDD might appear to value appearance, but values-clarification exercises might reveal that the true values are human connectedness with corresponding desires to be loved and wanted. Therapeutically, this value can be pursued in ways that de-emphasize the importance of attractiveness. Part of this component includes an agreement to live life for its values and not for symptom reduction. In turn, this increases commitment to living a healthy life and assists in commitment to therapy.

Conclusion: A Meaningful Existence

ACT treatment goals include living a meaningful existence according to your values, focusing on the present moment, and tolerating emotions. It is clear that including ACT with CBT serves to increase the acceptance and motivation to engage in treatment.

It is clear that including ACT with CBT serves to increase the acceptance and motivation to engage in treatment.

Agnes Selinger, PhD, Southwestern Vermont Consortium

Fugen Neziroglu, PhD, ABBP, Director, Bio-Behavioral Institute

Treatment of body dysmorphic disorder【 Psychologist's consultation 】

Recently, there has been a steady increase in people's dissatisfaction with various areas of their lives, and especially with their own bodies. More and more people of all ages express dissatisfaction with their appearance. Typically, complaints relate to minor, imaginary or barely noticeable imperfections in the face, the size of body features (too small or too large), thinning hair, acne, wrinkles, scarring, spider veins, pallor or redness of the face, asymmetry or lack of proportionality. Sometimes the complaint can be extremely vague. For example, a person may describe themselves as having a nasty or extremely ugly face.

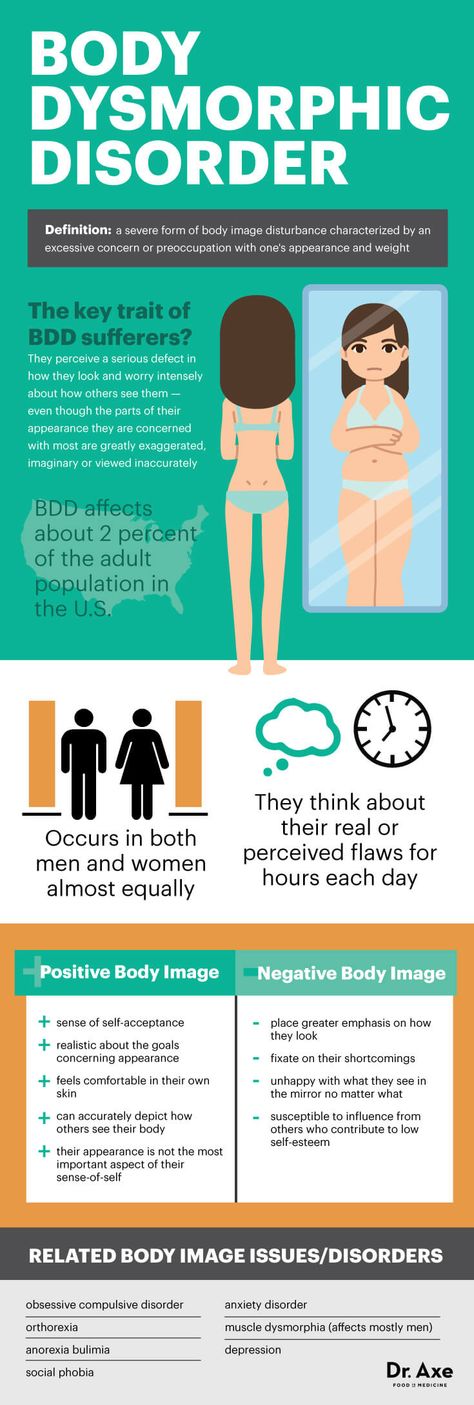

So what is body dysmorphic disorder? Or as it is also called - dysmorphophobia. This is a disorder in which a person is overly concerned about a minor defect, a feature of their body, or an imaginary flaw.

This is a disorder in which a person is overly concerned about a minor defect, a feature of their body, or an imaginary flaw.

In the population, this disease is 2.4% [1]. It usually begins in adolescence and affects both men and women in the same way [2]. In most cases, the disease remains undiagnosed. Which doctor will a person turn to with help if he thinks that she has skin problems or is not satisfied with the shape of her nose? To a dermatologist and a plastic surgeon or an otolaryngologist. Because of this, many cases are not considered from a mental health standpoint. Dysmorphophobia can be called a hidden disease, due to the lack of knowledge about it, both specialists and the general public.

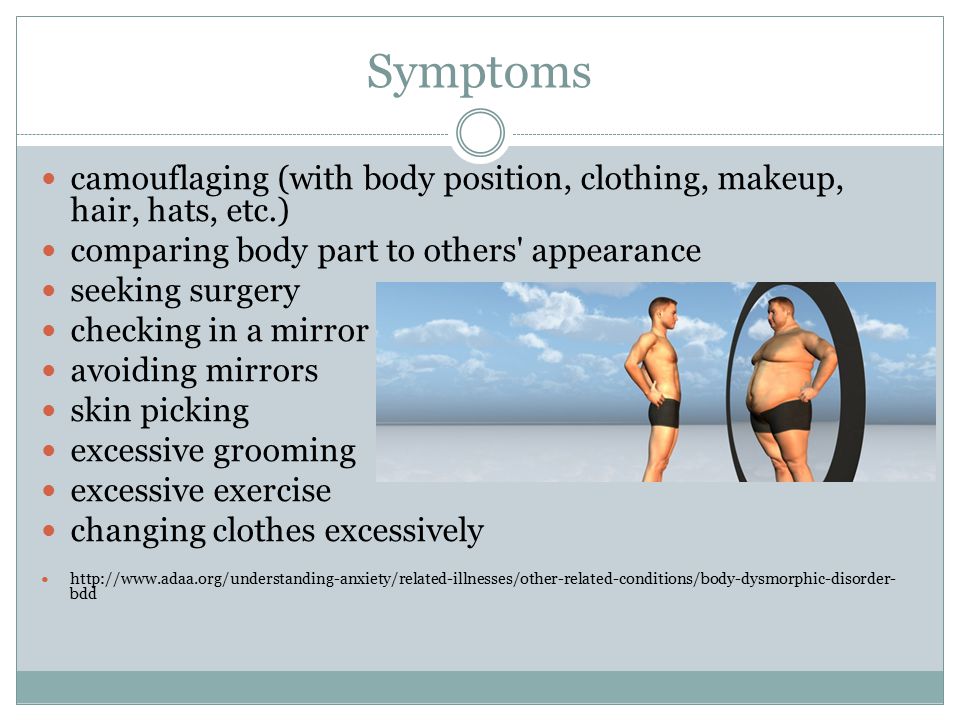

What are the symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder?

People with body dysmorphic disorder are overly concerned with their appearance. But let's think and remember something. Have we ever had thoughts in our heads that we are somehow different? Or have we always been satisfied with everything in our own body? Especially when we were teenagers, following fashion trends and trying to go for "ours". If you're happy with yourself, that's fine, and if not, why not?

If you're happy with yourself, that's fine, and if not, why not?

There are a lot of symptoms of dysmorphophobia. Each person can have something different. The most common “alarm calls”, noticing which, in yourself or a loved one, you should contact a specialist:

Frequent contemplation of one's own reflection in the mirror, trying to find an advantageous angle in which the probable defect is not visible, and it is possible to determine what kind of correction "flaws" is needed.

- Refusal to be photographed. Under various justifications and explanations lies the fear of "perpetuating ugliness."

- Attempts to hide a possible defect. Using makeup, wearing oversized, baggy clothes or hats.

- Excessive grooming. Constant combing, cleaning the skin, pulling hair, shaving and so on.

- Obsessive touch of "defect".

- Inquiries of loved ones about the "defect".

- Excessive diet and exercise.

- Refusing to leave the house or going out only at certain times, such as at night, so that no one sees the "shortcomings".

- Alcohol and/or drug abuse. Often as an attempt at self-medication or sedation.

- Persistently low self-esteem.

The new behavior that occurs during this disorder takes a lot of effort and time. This can change the quality of life, lead to a number of problems in professional, social and personal life.

To find solace, you can use countless cosmetic, surgical or folk procedures to "correct" a flaw. In the end, you can get temporary satisfaction, but often the attention returns to the "problem" areas. And at this moment everything starts all over again.

What are the treatments for BDD?

Treatment may include medication and cognitive behavioral therapy. [3]

Medical therapy are antidepressants. This method seems very attractive, since all the work is done by drugs.

During treatment, symptoms and feelings may decrease in intensity or disappear altogether. Health, social and personal well-being improves.

But what happens after a person stops taking medication?

After all, beliefs about yourself and your appearance cannot be changed by drugs.

9 comes to the rescue here0007 cognitive behavioral therapy.

How can CBT help?

People with body dysmorphic disorders have something in common - they all have certain ideas about their appearance. At this point, an important question arises: are these representations 100% true? Or people are so preoccupied with their "illness" that they have already forgotten how it could be otherwise. How can you relate to this differently and rethink your attitude to certain things.

So, the work begins with finding twisted representations.

What could give impetus to these thoughts, why it could not catch them before, but at a certain moment - all attention was focused precisely on this.

Many people with body dysmorphic disorder also have other problems. For example, low self-esteem, depression, may be invisible to others, or to the person himself, and as a result, thoughts of suicide. The suffering that people feel can take on incredible proportions. Thus, work can be focused on several targets at once.

The suffering that people feel can take on incredible proportions. Thus, work can be focused on several targets at once.

It is important to be able not only to identify, but also to change attitudes towards certain thoughts or beliefs. This skill will be with you throughout your life, which will help you live a fulfilling life.

What are the steps to overcome BDD?

Science does not stand still, and with it, cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy (CBT) [4]. Therefore, we can say that at the moment therapy includes the following steps [5]:

1. Understanding body dysmorphic disorder. Psychoeducation.

This step provides general information about body image and body dysmorphic disorder. We consider how this problem can develop, and discuss certain negative consequences of the disorder.

2. What makes body dysmorphic to be with us?

This step looks at how past experiences can affect you in the present and explores how body dysmorphia can be maintained in the long term.

3. Reducing anxiety about appearance

This step explores ways in which you can begin to reduce the amount of time you spend on your appearance and thus begin to break the cycle of body dysmorphic disorder.

4. Reducing checking and seeking reassurance

This step explores different ways of checking and seeking reassurance in people based on their appearance, discusses the difference between helpful and unfriendly checks, and introduces strategies to reduce and eliminate these behaviors.

5. Overcoming negative predictions, avoidance and defensive behaviors

This stage introduces strategies to challenge and experiment with negative predictions, as well as reduce anxiety, avoidance and defensive behaviors, often associated with certain types of thinking.

6. Adjusting Appearance Assumptions

In this step, we will focus on challenging unworthy rules and assumptions that can keep you in the vicious cycle of disorder.

7. Self-management planning. Learning to be your own therapist.

This final step brings together all the concepts of the information above, introduces the new model you are working with, and includes a self-management plan to help you stay on track and prevent relapses.

Even though body dysmorphic disorder is a test for a person, it must be remembered that there are already proven treatments. One of them is antidepressants. The other is cognitive behavioral therapy. Psychotherapy can not only help you overcome body dysmorphic disorder, but it can also give you a perspective to reassess certain things in your life.

Dysmorphophobia - treatment

UARU

Our specialization - treatment of Dysmorphophobia Obsessive-compulsive disorder and associated anxiety disorders

- Read this article

- What is Dysmorphophobia

- Dysmorphia and eating disorders

- Dysmorphophobia - symptoms

- Dysmorphophobia treatment

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Hypnosis

- Individual treatment

- Group treatment

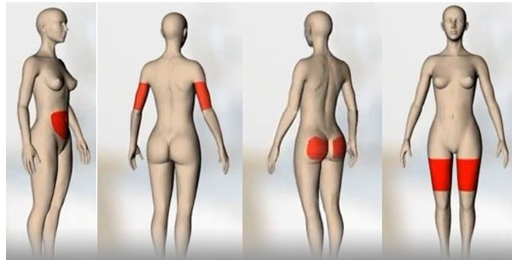

The main distinguishing feature of body dysmorphic disorder (body dysmorphophobia) is obsessions, an exaggerated concern about the perception of minor defects in one's own appearance. Body Dysmorphophobia (BDD) - obsessions can be observed as excessive, exaggerated worry about minor defects, or as repetitive, uncomfortable thoughts about a completely imaginary defect. The obsessions in BDD are primarily focused on the head and face, but may be associated with any other part of the body. Dysmorphophobia goes beyond the normal preoccupation with one's own appearance, and can significantly impair professional performance, education, and interpersonal relationships as well. In extremely severe cases, a person who has Dysmorphophobia may try to completely avoid all contact with people in order to protect himself from the fact that another person can observe his defects.

Body Dysmorphophobia (BDD) - obsessions can be observed as excessive, exaggerated worry about minor defects, or as repetitive, uncomfortable thoughts about a completely imaginary defect. The obsessions in BDD are primarily focused on the head and face, but may be associated with any other part of the body. Dysmorphophobia goes beyond the normal preoccupation with one's own appearance, and can significantly impair professional performance, education, and interpersonal relationships as well. In extremely severe cases, a person who has Dysmorphophobia may try to completely avoid all contact with people in order to protect himself from the fact that another person can observe his defects.

Body dysmorphic rates are 12 times higher among gym goers with nutritional problems

According to a new study published in the journal Eating and Weight Disorders, people with eating disorders are 12 times more likely to be preoccupied with perceived imperfections in their appearance than people without them. .

.

Researchers at Anglia Ruskin University (ARU) interviewed more than 1,600 health club members recruited through social media. They found that the number of people with body dysmorphic disorder was 12 times higher among people with a suspected eating disorder.

About 30% of the participants reported eating disorders, and the researchers noted that 76% of these people also suffered from body dysmorphia (body dysmorphia).

Journal reference:

Mike Trott, James Johnstone, Joe Firth, Igor Grabovac, Daragh McDermott, Lee Smith. Prevalence and correlates of body dysmorphic disorder in health club users in the presence vs absence of eating disorder symptomology . Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity , 2020; DOI: 10.1007/s40519-020-01018-y

Dysmorphophobia or body dysmorphic disorder and its symptoms

Symptoms of a person diagnosed with Dysmorphophobia can vary significantly from one person to another.

Dysmorphophobia - examples of general obsessions:

- Obsessions / ideas that moles and freckles have become too large or noticeable

- Acne

- Obsessive anxiety/fear/fear that minor scars are actually more visible

- Obsessions that a person has too much facial or body hair

- Obsessive thoughts that a person is about to go bald or that he has too little hair on his head

- Obsessions that he has the wrong (small or large) size and / or shape of the genitals

- Obsessive concern that the breast size is too small or large

- The person thinks their muscles are too small (also known as Muscle Dysmorphia or "Bigorexia")

- Obsessions/thoughts that the person has the wrong size, shape and/or symmetry of the face or other body part

Dysmorphophobia - common examples of obsessive behavior:

- Repeated checks for minor and/or imagined flaws/defects in the mirror

- Avoidance of looking at yourself in the mirror

- Attempts to prevent someone from taking a photo of a person

- Repetitive grooming activities such as shaving, combing hair, etc.

- Repetitive attempts to check, touch and/or measure minor or imagined imperfections

- Use of excessive amounts of cosmetics to hide minor or imagined flaws/defects

- A person tries to wear certain clothes to hide minor or imaginary defects

- Multiple visits to doctors, especially dermatologists

- Repetitive medical procedures to correct minor and/or imaginary defects

As shown above, body dysmorphic disorder has certain obsessive-compulsive characteristics that are very similar to those of OCD. One recent study showed that 24% of people who develop BDD also had OCD. The most significant similarity that links disorders such as OCD and body dysmorphic disorder is the cyclical process that results in an increase in symptoms. In this process, which is called the obsessive-compulsive cycle, the obsessive and avoidant behavior that a person uses to reduce their anxiety actually worsens and reinforces their obsessions (thoughts).

Dysmorphophobia - treatment

Dysmorphophobia - treating people using Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The same Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy (CBT) techniques that are so effective in treating OCD are also used in the treatment of body dysmorphic disorder (Body Dysmorphic Disorder) . In fact, several recent studies have shown a significant reduction in symptoms in people diagnosed with Body Dysmorphophobia when treated with cognitive behavioral psychotherapy (CBT). The main technique that is used both in the treatment of OCD and in the treatment of people who present with Body Dysmorphophobia is a type of cognitive behavioral psychotherapy (CBT) called Exposure and Response Prevention (EPR). Another CBT technique that is extremely effective is called Cognitive Restructuring, which trains clients to challenge the validity of their thoughts that cause them to perceive their own body in a distorted way.

In addition, a variant of EPR has been developed that is also extremely effective in treating patients diagnosed with Dysmorphophobia. This method is called the "imagination" method and uses short stories based on the obsessions/thoughts of the patient who has Dysmorphophobia. These stories are audio-recorded and used as an EPR tool, allowing the client to experience situations that would not be possible with standard EPR tools. By combining this method with standard EPR methods, as well as with other cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques such as Cognitive Restructuring. This type of imaginary representation can significantly reduce the frequency and extent of obsessions, in case of body dysmorphic disorder (body dysmorphic disorder), as well as reduce individual sensitivity to obsessive thoughts and images, when diagnosed with body dysmorphia (dysmorphophobia).

This method is called the "imagination" method and uses short stories based on the obsessions/thoughts of the patient who has Dysmorphophobia. These stories are audio-recorded and used as an EPR tool, allowing the client to experience situations that would not be possible with standard EPR tools. By combining this method with standard EPR methods, as well as with other cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) techniques such as Cognitive Restructuring. This type of imaginary representation can significantly reduce the frequency and extent of obsessions, in case of body dysmorphic disorder (body dysmorphic disorder), as well as reduce individual sensitivity to obsessive thoughts and images, when diagnosed with body dysmorphia (dysmorphophobia).

One of the most effective CBT developments for treating people diagnosed with Body Dysmorphophobia is Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. The main goal of mindfulness-based cognitive-behavioral therapy is to learn how to stop the subjective perception of uncomfortable psychological experiences. From the point of view of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, much of our psychological stress is nothing more than the result of trying to control and eliminate the discomfort caused by unwanted thoughts, feelings, sensations, and beliefs. To paraphrase, we can say that the discomfort we experience is not the problem - the problem is our attempts to control and eliminate our discomfort. For people who exhibit Body Dysmorphia (Dysmorphophobia), the main goal of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy is to develop the ability to more willingly / calmly experience their own uncomfortable, obsessive thoughts / ideas, feelings, sensations and beliefs, without using obsessive behavior, avoidance behavior, reassurance seeking, and/or thought rituals. To learn more about mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy for people diagnosed with Body Dysmorphic Disorder / Body Dysmorphophobia, click here.

From the point of view of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, much of our psychological stress is nothing more than the result of trying to control and eliminate the discomfort caused by unwanted thoughts, feelings, sensations, and beliefs. To paraphrase, we can say that the discomfort we experience is not the problem - the problem is our attempts to control and eliminate our discomfort. For people who exhibit Body Dysmorphia (Dysmorphophobia), the main goal of mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy is to develop the ability to more willingly / calmly experience their own uncomfortable, obsessive thoughts / ideas, feelings, sensations and beliefs, without using obsessive behavior, avoidance behavior, reassurance seeking, and/or thought rituals. To learn more about mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy for people diagnosed with Body Dysmorphic Disorder / Body Dysmorphophobia, click here.

Using these tools, people learn to challenge their own imagined body problems, as well as get rid of the compulsive and avoidant behaviors they use to deal with their own bodily discomfort. If you would like to learn more about cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder), Dysmorphophobia (body dysmorphic disorder/body dysmorphia) and comorbid anxiety disorders click here.

If you would like to learn more about cognitive behavioral therapy for the treatment of OCD (obsessive compulsive disorder), Dysmorphophobia (body dysmorphic disorder/body dysmorphia) and comorbid anxiety disorders click here.

Dysmorphophobia - treatment of people using the method Hypnosuggestive psychotherapy (hypnosis and suggestion)

Hypnosuggestive psychotherapy (hypnosis and suggestion) is used to treat people diagnosed with Dysmorphophobia / Body Dysmorphic Disorder. Hypno-suggestive psychotherapy is very effective and allows you to fix the results achieved with the help of cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy at an unconscious level. This is achieved due to the fact that during hypnotization a person is immersed in a certain state of consciousness, which is characterized by a sharp narrowing of the volume of consciousness and focus on suggestion. Thus, it is possible not only to introduce the necessary attitude to the unconscious level, but also to do it bypassing the human consciousness. In addition, we teach self-hypnosis skills to a person who suffers from body dysmorphia, which allows him to independently consolidate and strengthen the results achieved during work. Hypnosis when working with a person who manifests Dysmorphophobia, in the end result, allows you to replace unwanted ideas (thoughts) with more adaptive ones, build in new behaviors instead of obsessive behaviors, avoidance behaviors, search for reassurances. Thus, hypnosis (hypnosuggestive psychotherapy) allows a person to be more free in situations where he previously experienced unwanted obsessions, images, feelings and sensations. To learn more about treating a person diagnosed with Dysmorphophobia (body dysmorphia) using hypnosis.

In addition, we teach self-hypnosis skills to a person who suffers from body dysmorphia, which allows him to independently consolidate and strengthen the results achieved during work. Hypnosis when working with a person who manifests Dysmorphophobia, in the end result, allows you to replace unwanted ideas (thoughts) with more adaptive ones, build in new behaviors instead of obsessive behaviors, avoidance behaviors, search for reassurances. Thus, hypnosis (hypnosuggestive psychotherapy) allows a person to be more free in situations where he previously experienced unwanted obsessions, images, feelings and sensations. To learn more about treating a person diagnosed with Dysmorphophobia (body dysmorphia) using hypnosis.

Body Dysmorphophobia / Body Dysmorphia: individual treatment / psychotherapy

Kyiv OCD Center offers individual psychotherapy for the treatment of adults and adolescents who manifest Dysmorphophobia / Body dysmorphia, the main methods are cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy (CBT) and hypno-suggestive psychotherapy (hypnosis and suggestion) ). If you would like to discuss treatment options at the Kiev OCD Center, you can call us at +380678364590 or click here to write to us.

If you would like to discuss treatment options at the Kiev OCD Center, you can call us at +380678364590 or click here to write to us.

Dysmorphophobia/Body Dysmorphia: Group Treatment/Psychotherapy

In addition to providing individual Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy (CBT) and Hypno-Suggestive Psychotherapy (hypnosis and suggestion), the Kiev OCD Center provides weekly support/treatment groups for adults with OCD, Body dysmorphic disorder (Dysmorphophobia), as well as comorbid anxiety disorders. Studies have shown that group treatment is extremely effective for treating OCD and related anxiety disorders, including people diagnosed with Dysmorphophobia (Body Dysmorphia). All groups in the Kiev OCD Center are conducted by our specialists, the same treatment methods are used as in individual treatment. It should be noted that before you can enter the group, you must undergo an individual diagnosis, groups are open only to adults over 18 years of age with diagnoses of OCD, Body Dysmorphia (Dysmorphophobia), and comorbid anxiety disorders.