First line treatment panic disorder

Panic attacks and panic disorder - Diagnosis and treatment

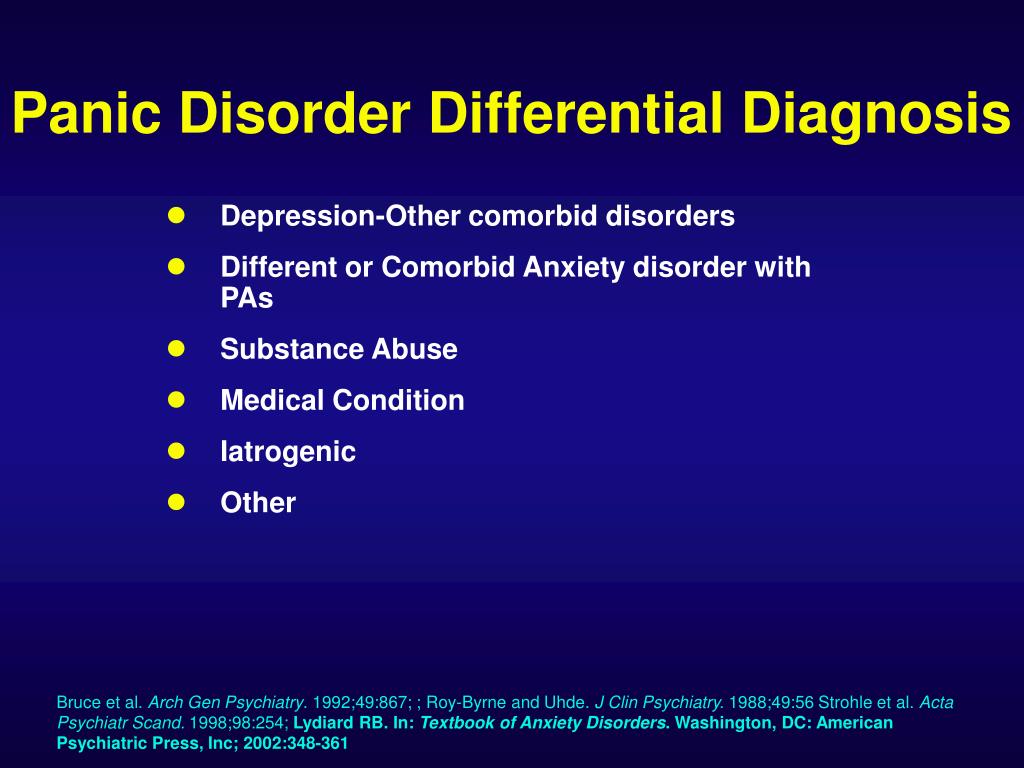

Diagnosis

Your primary care provider will determine if you have panic attacks, panic disorder or another condition, such as heart or thyroid problems, with symptoms that resemble panic attacks.

To help pinpoint a diagnosis, you may have:

- A complete physical exam

- Blood tests to check your thyroid and other possible conditions and tests on your heart, such as an electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG)

- A psychological evaluation to talk about your symptoms, fears or concerns, stressful situations, relationship problems, situations you may be avoiding, and family history

You may fill out a psychological self-assessment or questionnaire. You also may be asked about alcohol or other substance use.

Criteria for diagnosis of panic disorder

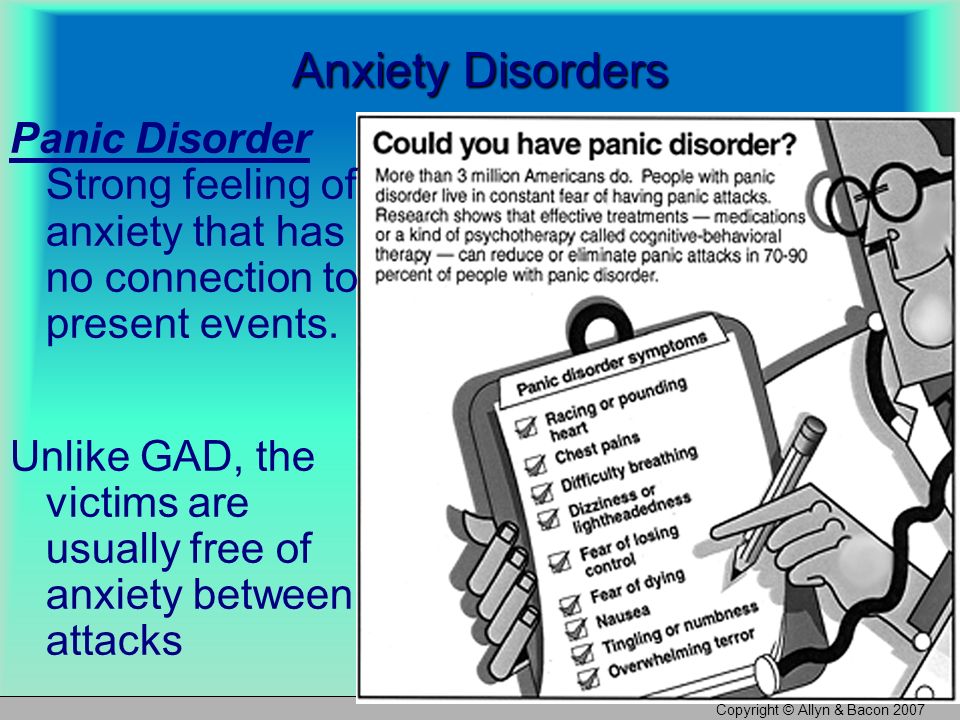

Not everyone who has panic attacks has panic disorder. For a diagnosis of panic disorder, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association, lists these points:

- You have frequent, unexpected panic attacks.

- At least one of your attacks has been followed by one month or more of ongoing worry about having another attack; continued fear of the consequences of an attack, such as losing control, having a heart attack or "going crazy"; or significant changes in your behavior, such as avoiding situations that you think may trigger a panic attack.

- Your panic attacks aren't caused by drugs or other substance use, a medical condition, or another mental health condition, such as social phobia or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

If you have panic attacks but not a diagnosed panic disorder, you can still benefit from treatment. If panic attacks aren't treated, they can get worse and develop into panic disorder or phobias.

More Information

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG)

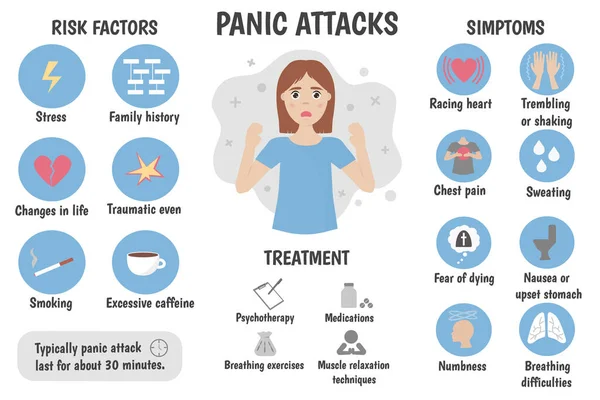

Treatment

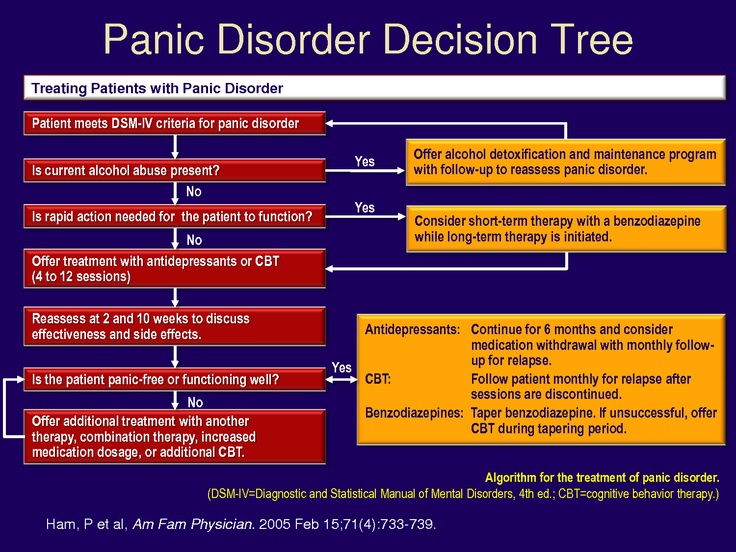

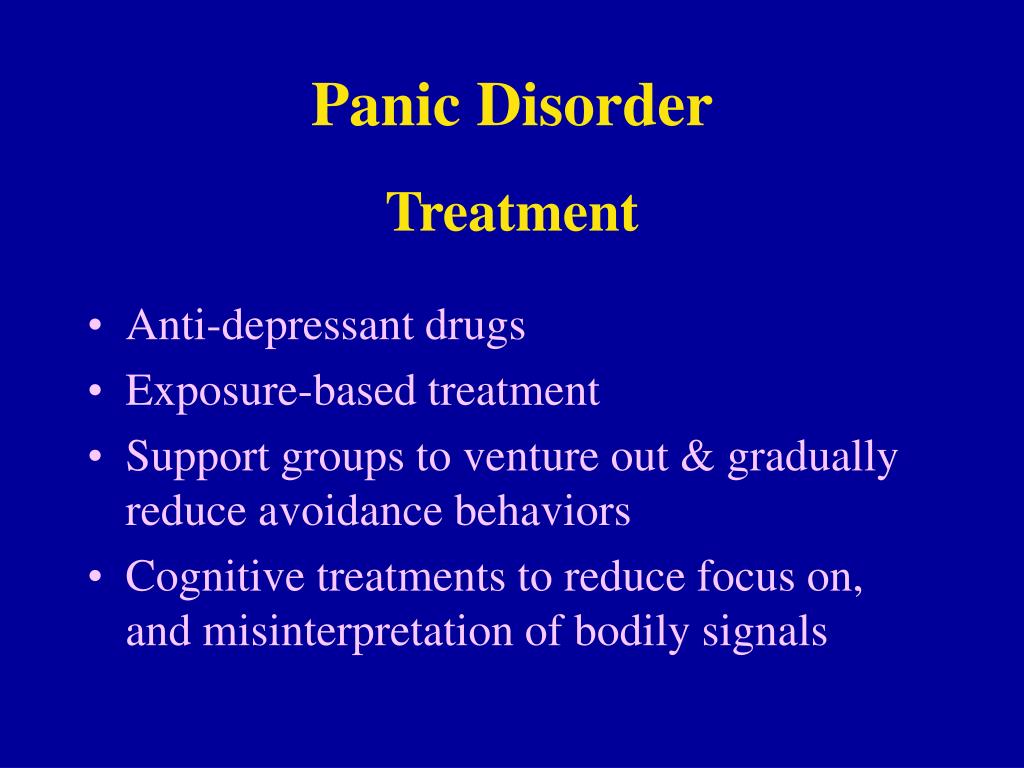

Treatment can help reduce the intensity and frequency of your panic attacks and improve your function in daily life. The main treatment options are psychotherapy and medications. One or both types of treatment may be recommended, depending on your preference, your history, the severity of your panic disorder and whether you have access to therapists who have special training in treating panic disorders.

One or both types of treatment may be recommended, depending on your preference, your history, the severity of your panic disorder and whether you have access to therapists who have special training in treating panic disorders.

Psychotherapy

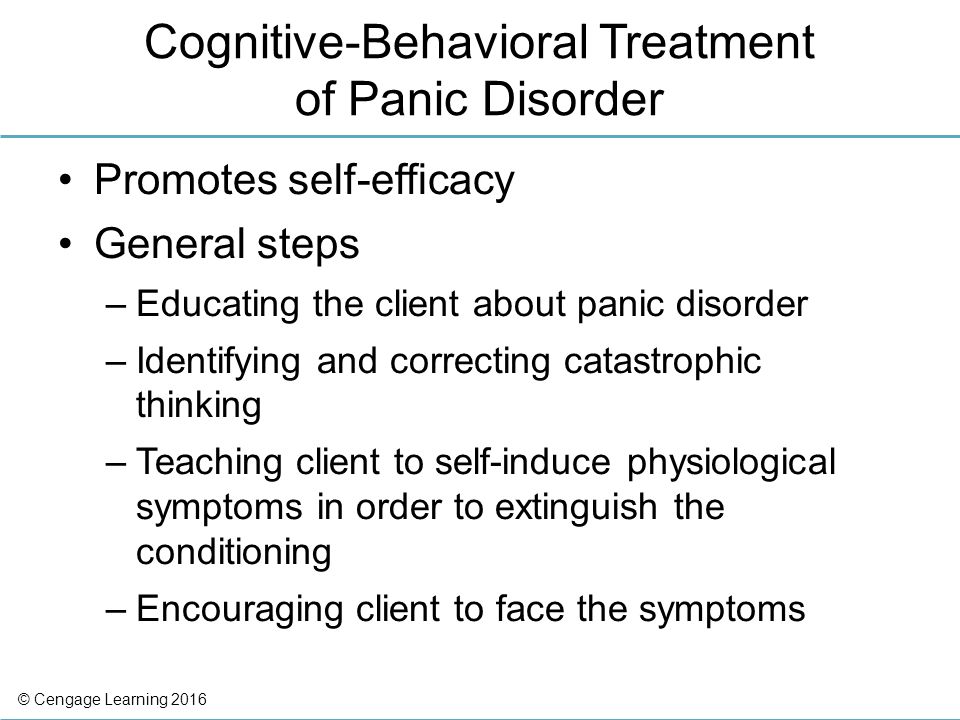

Psychotherapy, also called talk therapy, is considered an effective first choice treatment for panic attacks and panic disorder. Psychotherapy can help you understand panic attacks and panic disorder and learn how to cope with them.

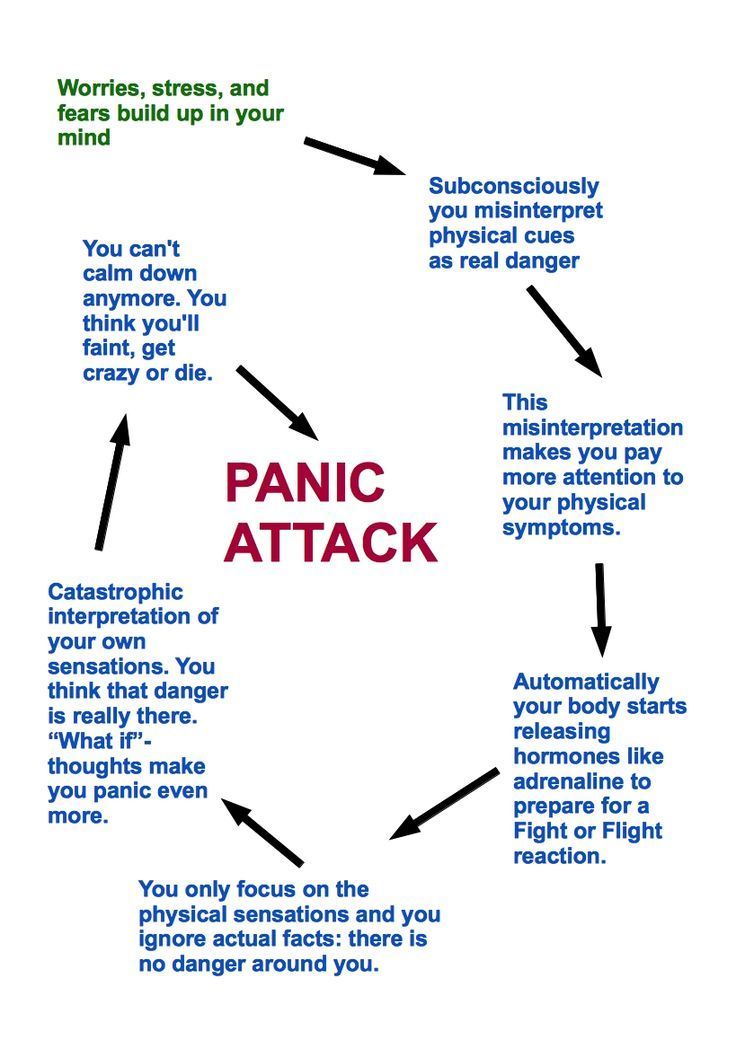

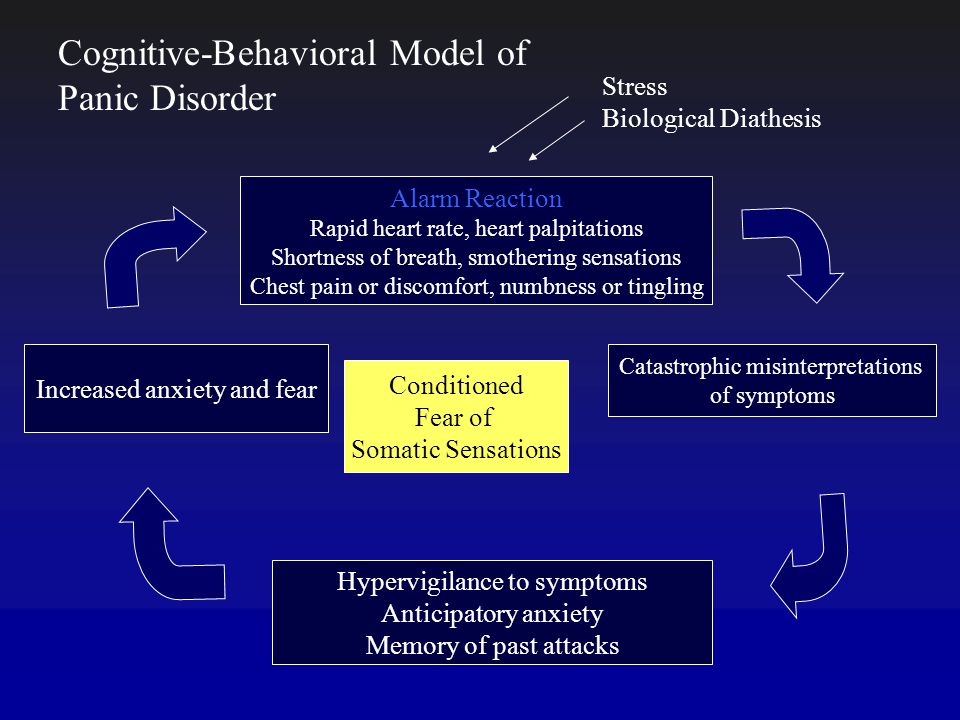

A form of psychotherapy called cognitive behavioral therapy can help you learn, through your own experience, that panic symptoms are not dangerous. Your therapist will help you gradually re-create the symptoms of a panic attack in a safe, repetitive manner. Once the physical sensations of panic no longer feel threatening, the attacks begin to resolve. Successful treatment can also help you overcome fears of situations that you've avoided because of panic attacks.

Seeing results from treatment can take time and effort. You may start to see panic attack symptoms reduce within several weeks, and often symptoms decrease significantly or go away within several months. You may schedule occasional maintenance visits to help ensure that your panic attacks remain under control or to treat recurrences.

You may start to see panic attack symptoms reduce within several weeks, and often symptoms decrease significantly or go away within several months. You may schedule occasional maintenance visits to help ensure that your panic attacks remain under control or to treat recurrences.

Medications

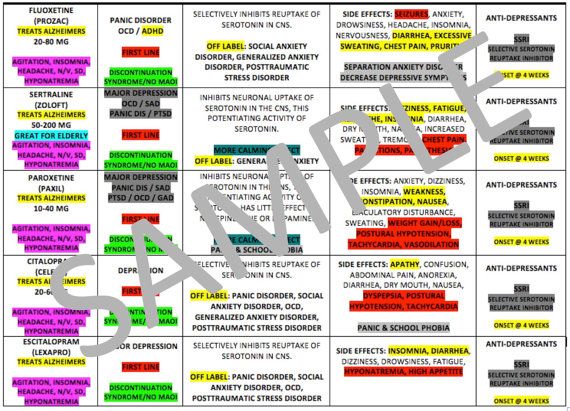

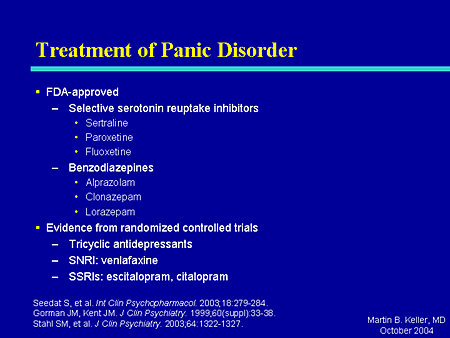

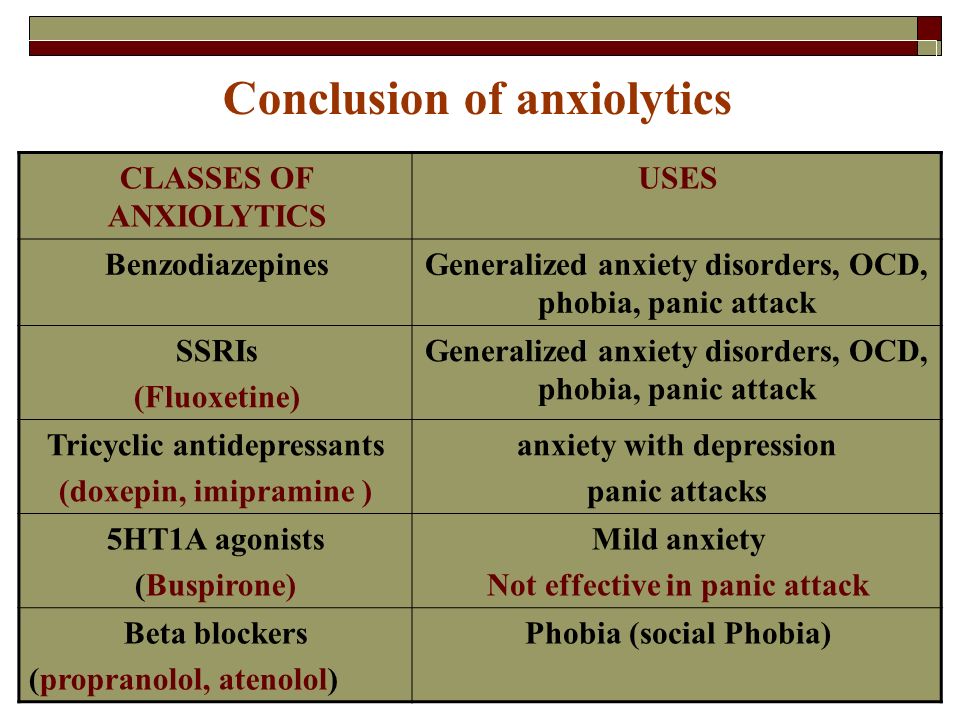

Medications can help reduce symptoms associated with panic attacks as well as depression if that's an issue for you. Several types of medication have been shown to be effective in managing symptoms of panic attacks, including:

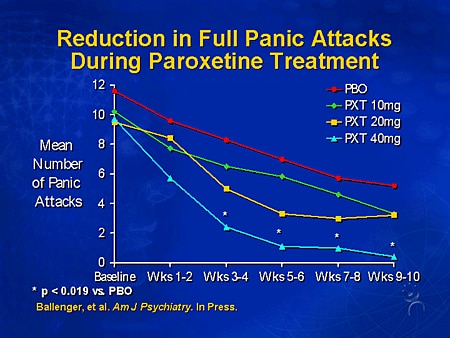

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Generally safe with a low risk of serious side effects, SSRI antidepressants are typically recommended as the first choice of medications to treat panic attacks. SSRIs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of panic disorder include fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva) and sertraline (Zoloft).

- Serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs).

These medications are another class of antidepressants. The SNRI venlafaxine (Effexor XR) is FDA approved for the treatment of panic disorder.

These medications are another class of antidepressants. The SNRI venlafaxine (Effexor XR) is FDA approved for the treatment of panic disorder. - Benzodiazepines. These sedatives are central nervous system depressants. Benzodiazepines approved by the FDA for the treatment of panic disorder include alprazolam (Xanax) and clonazepam (Klonopin). Benzodiazepines are generally used only on a short-term basis because they can be habit-forming, causing mental or physical dependence. These medications are not a good choice if you've had problems with alcohol or drug use. They can also interact with other drugs, causing dangerous side effects.

If one medication doesn't work well for you, your doctor may recommend switching to another or combining certain medications to boost effectiveness. Keep in mind that it can take several weeks after first starting a medication to notice an improvement in symptoms.

All medications have a risk of side effects, and some may not be recommended in certain situations, such as pregnancy. Talk with your doctor about possible side effects and risks.

Talk with your doctor about possible side effects and risks.

More Information

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Psychotherapy

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Lifestyle and home remedies

While panic attacks and panic disorder benefit from professional treatment, these self-care steps can help you manage symptoms:

- Stick to your treatment plan. Facing your fears can be difficult, but treatment can help you feel like you're not a hostage in your own home.

- Join a support group. Joining a group for people with panic attacks or anxiety disorders can connect you with others facing the same problems.

- Avoid caffeine, alcohol, smoking and recreational drugs. All of these can trigger or worsen panic attacks.

- Practice stress management and relaxation techniques. For example, yoga, deep breathing and progressive muscle relaxation — tensing one muscle at a time, and then completely releasing the tension until every muscle in the body is relaxed — also may be helpful.

- Get physically active. Aerobic activity may have a calming effect on your mood.

- Get sufficient sleep. Get enough sleep so that you don't feel drowsy during the day.

Alternative medicine

Some dietary supplements have been studied as a treatment for panic disorder, but more research is needed to understand the risks and benefits. Herbal products and dietary supplements aren't monitored by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) the same way medications are. You can't always be certain of what you're getting and whether it's safe.

Before trying herbal remedies or dietary supplements, talk to your doctor. Some of these products can interfere with prescription medications or cause dangerous interactions.

Preparing for your appointment

If you've had signs or symptoms of a panic attack, make an appointment with your primary care provider. After an initial evaluation, he or she may refer you to a mental health professional for treatment.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Your symptoms, including when they first occurred and how often you've had them

- Key personal information, including traumatic events in your past and any stressful major events that occurred before your first panic attack

- Medical information, including other physical or mental health conditions that you have

- Medications, vitamins, herbal products and other supplements, and the dosages

- Questions to ask your doctor

Ask a trusted family member or friend to go with you to your appointment, if possible, to lend support and help you remember information.

Questions to ask your primary care provider at your first appointment

- What do you believe is causing my symptoms?

- Is it possible that an underlying medical problem is causing my symptoms?

- Do I need any diagnostic tests?

- Should I see a mental health professional?

- Is there anything I can do now to help manage my symptoms?

Questions to ask if you're referred to a mental health professional

- Do I have panic attacks or panic disorder?

- What treatment approach do you recommend?

- If you're recommending therapy, how often will I need it and for how long?

- Would group therapy be helpful in my case?

- If you're recommending medications, are there any possible side effects?

- For how long will I need to take medication?

- How will you monitor whether my treatment is working?

- What can I do now to reduce the risk of my panic attacks recurring?

- Are there any self-care steps I can take to help manage my condition?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can have?

- What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask any other questions.

What to expect from your doctor

Your primary care provider or mental health professional may ask:

- What are your symptoms, and when did they first occur?

- How often do your attacks occur, and how long do they last?

- Does anything in particular seem to trigger an attack?

- How often do you experience fear of another attack?

- Do you avoid locations or experiences that seem to trigger an attack?

- How do your symptoms affect your life, such as school, work and personal relationships?

- Did you experience major stress or a traumatic event shortly before your first panic attack?

- Have you ever experienced major trauma, such as physical or sexual abuse or military battle?

- How would you describe your childhood, including your relationship with your parents?

- Have you or any of your close relatives been diagnosed with a mental health problem, including panic attacks or panic disorder?

- Have you been diagnosed with any medical conditions?

- Do you use caffeine, alcohol or recreational drugs? How often?

- Do you exercise or do other types of regular physical activity?

Your primary care provider or mental health professional will ask additional questions based on your responses, symptoms and needs.![]() Preparing and anticipating questions will help you make the most of your appointment time.

Preparing and anticipating questions will help you make the most of your appointment time.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

Pharmacological Therapy in Panic Disorder: Current Guidelines and Novel Drugs Discovery for Treatment-resistant Patient

1. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, Walters EE. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of twelve-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:617–627. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. King M, Nazareth I, Levy G, Walker C, Morris R, Weich S, et al. Prevalence of common mental disorders in general practice attendees across Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:362–367. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039966. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Prevalence of common mental disorders in general practice attendees across Europe. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;192:362–367. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.039966. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Marchesi C. Pharmacological management of panic disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2008;4:93–106. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S1557. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Masi G, Favilla L, Mucci M, Millepiedi S. Panic disorder in clinically referred children and adolescents. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2000;31:139–151. doi: 10.1023/A:1001948610318. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-IV-TR. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

7. Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Jin R, Ruscio AM, Shear K, Walters EE. The epidemiology of panic attacks, panic disorder, and agoraphobia in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:415–424. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.4.415. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Gorman JM, Kent JM, Sullivan GM, Coplan JD. Neuroanatomical hypothesis of panic disorder, revised. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:493–505. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.4.493. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Freire RC, Hallak JE, Crippa JA, Nardi AE. New treatment options for panic disorder: clinical trials from 2000 to 2010. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:1419–1428. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2011.562200. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Perna G, Guerriero G, Caldirola D. Emerging drugs for panic disorder. Expert Opin Emerg Drugs. 2011;16:631–645. doi: 10.1517/14728214.2011.628313. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Nardi AE, Freire RC, Zin WA. Panic disorder and control of breathing. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2009;167:133–143. doi: 10.1016/j.resp.2008.07.011. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Gorman JM, Docherty JP. A hypothesized role for dendritic remodeling in the etiology of mood and anxiety disorders. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22:256–264. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.3.256. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22:256–264. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.3.256. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Klein DF. False suffocation alarms, spontaneous panics, and related conditions. An integrative hypothesis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:306–317. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820160076009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Esquivel G, Schruers KR, Maddock RJ, Colasanti A, Griez EJ. Acids in the brain: a factor in panic? J Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:639–647. doi: 10.1177/0269881109104847. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Austin D, Blashki G, Barton D, Klein B. Managing panic disorder in general practice. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:563–571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Marchesi C, De Panfilis C, Cantoni A, Fontò S, Giannelli MR, Maggini C. Personality disorders and response to medication treatment in panic disorder: a 1-year naturalistic study. Prog NeuroPsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:1240–1245. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006. 03.010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

03.010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Bakker A, van Balkom AJ, Stein DJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of panic disorder. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;8:473–482. doi: 10.1017/S1461145705005201. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Stein MB. Panic disorder. Lancet. 2006;368:1023–1032. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69418-X. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Batelaan NM, Van Balkom AJ, Stein DJ. Evidence-based pharmacotherapy of panic disorder: an update. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15:403–415. doi: 10.1017/S1461145711000800. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Bystritsky A, Kerwin L, Niv N, Natoli JL, Abrahami N, Klap R, et al. Clinical and subthreshold panic disorder. Depress Anxiety. 2010;27:381–389. doi: 10.1002/da.20622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Kroenke K. Patients presenting with somatic complaints: epidemiology, psychiatric comorbidity and management. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2003;12:34–43. doi: 10.1002/mpr.140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2003;12:34–43. doi: 10.1002/mpr.140. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Starcevic V. Treatment of panic disorder: recent developments and current status. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8:1219– 1232. doi: 10.1586/14737175.8.8.1219. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE), National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, National Collaborating Centre for Primary Care. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder (with or without agoraphobia) in adults: management in primary, secondary and community care [CG113] London: NICE; 2011. [Google Scholar]

24. Mitte K. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of psycho- and pharmacotherapy in panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:27–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Imai H, Tajika A, Chen P, Pompoli A, Furukawa TA. Psychological therapies versus pharmacological interventions for panic disorder with or without agoraphobia in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD011170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;10:CD011170. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Gould RA, Ott MW, Pollack MH. A meta-analysis of treatment outcome for panic disorder. Clin Psychol Rev. 1995;15:819– 844. doi: 10.1016/0272-7358(95)00048-8. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Bighelli I, Trespidi C, Castellazzi M, Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Girlanda F, et al. Antidepressants and benzodiazepines for panic disorder in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;9:CD011567. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Otto MW, Tuby KS, Gould RA, McLean RY, Pollack MH. An effect-size analysis of the relative efficacy and tolerability of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors for panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1989–1992. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.12.1989. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Bakker A, van Balkom AJ, Spinhoven P. SSRIs vs. TCAs in the treatment of panic disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106:163–167. doi: 10.1034/j. 1600-0447.2002.02255.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1600-0447.2002.02255.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Andrisano C, Chiesa A, Serretti A. Newer antidepressants and panic disorder: a meta-analysis. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;28:33–45. doi: 10.1097/YIC.0b013e32835a5d2e. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. American Psychiatric Association. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with panic disorder. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 2009. [Google Scholar]

32. Bandelow B, Zohar J, Hollander E, Kasper S, Möller HJ, Zohar J, et al. WFSBP Task Force on Treatment Guidelines for Anxiety, Obsessive-Compulsive and Post-Traumatic Stress Disoders. World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry (WFSBP) guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and post-traumatic stress disorders - first revision. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2008;9:248–312. doi: 10.1080/15622970802465807. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Serretti A, Chiesa A, Calati R, Perna G, Bellodi L, De Ronchi D. Novel antidepressants and panic disorder: evidence beyond current guidelines. Neuropsychobiology. 2011;63:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000321831. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Novel antidepressants and panic disorder: evidence beyond current guidelines. Neuropsychobiology. 2011;63:1–7. doi: 10.1159/000321831. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Freire RC, Machado S, Arias-Carrión O, Nardi AE. Current pharmacological interventions in panic disorder. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2014;13:1057–1065. doi: 10.2174/1871527313666140612125028. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Susman J, Klee B. The role of high-potency benzodiazepines in the treatment of panic disorder. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7:5–11. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v07n0101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Ferguson JM. SSRI antidepressant medications: adverse effects and tolerability. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;3:22–27. doi: 10.4088/PCC.v03n0105. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Serretti A. The present and future of precision medicine in psychiatry: focus on clinical psychopharmacology of antidepressants. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16:1–6. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.1.1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16:1–6. doi: 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.1.1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Perna G, Schruers K, Alciati A, Caldirola D. Novel investigational therapeutics for panic disorder. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2015;24:491–505. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2014.996286. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Gupta S, Nihalani N, Masand P. Duloxetine: review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic use in depression and other psychiatric disorders. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2007;19:125–132. doi: 10.1080/10401230701333319. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Simon NM, Kaufman RE, Hoge EA, Worthington JJ, Herlands NN, Owens ME, et al. Open-label support for duloxetine for the treatment of panic disorder. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15:19–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00076.x. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Anttila SA, Leinonen EV. A review of the pharmacological and clinical profile of mirtazapine.

42. Carpenter LL, Leon Z, Yasmin S, Price LH. Clinical experience with mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 1999;11:81–86. doi: 10.3109/10401239909147053. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Boshuisen ML, Slaap BR, Vester-Blokland ED, den Boer JA. The effect of mirtazapine in panic disorder: an open label pilot study with a single-blind placebo run-in period. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16:363–368. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200111000-00008. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. Carli V, Sarchiapone M, Camardese G, Romano L, DeRisio S. Mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:661–662. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.7.661. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Sarchiapone M, Amore M, De Risio S, Carli V, Faia V, Poterzio F, et al. Mirtazapine in the treatment of panic disorder: an open-label trial. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:35–38. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200301000-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:35–38. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200301000-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Ribeiro L, Busnello JV, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Madruga M, Quevedo J, Busnello EA, et al. Mirtazapine versus fluoxetine in the treatment of panic disorder. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2001;34:1303–1307. doi: 10.1590/S0100-879X2001001000010. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Moñtanes-Rada F, Bilbao-Garay J, de Lucas-Taracena MT, Ortiz-Ortiz ME. Venlafaxine, serotonin syndrome, and differential diagnoses. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25:101–102. doi: 10.1097/01.jcp.0000150236.45361.e1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Wong EH, Sonders MS, Amara SG, Tinholt PM, Piercey MF, Hoffmann WP, et al. Reboxetine: a pharmacologically potent, selective, and specific norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:818–829. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00291-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Dannon PN, Iancu I, Grunhaus L. The efficacy of reboxetine in the treatment-refractory patients with panic disorder: an open label study. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:329–333. doi: 10.1002/hup.421. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Hum Psychopharmacol. 2002;17:329–333. doi: 10.1002/hup.421. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Versiani M, Cassano G, Perugi G, Benedetti A, Mastalli L, Nardi A, et al. Reboxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, is an effective and well-tolerated treatment for panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:31–37. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v63n0107. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Seedat S, van Rheede van Oudtshoorn E, Muller JE, Mohr N, Stein DJ. Reboxetine and citalopram in panic disorder: a single-blind, cross-over, flexible-dose pilot study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;18:279–284. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200309000-00004. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Bertani A, Perna G, Migliarese G, Di Pasquale D, Cucchi M, Caldirola D, et al. Comparison of the treatment with paroxetine and reboxetine in panic disorder: a randomized, single-blind study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2004;37:206–210. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-832593. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Davis R, Whittington R, Bryson HM. Nefazodone. A review of its pharmacology and clinical efficacy in the management of major depression. Drugs. 1997;53:608–636. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753040-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Davis R, Whittington R, Bryson HM. Nefazodone. A review of its pharmacology and clinical efficacy in the management of major depression. Drugs. 1997;53:608–636. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199753040-00006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. DeMartinis NA, Schweizer E, Rickels K. An open-label trial of nefazodone in high comorbidity panic disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57:245–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Bystritsky A, Rosen R, Suri R, Vapnik T. Pilot open-label study of nefazodone in panic disorder. Depress Anxiety. 1999;10:137–139. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6394(1999)10:3<137::AID-DA8>3.0.CO;2-7. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Papp LA, Coplan JD, Martinez JM, de Jesus M, Gorman JM. Efficacy of open-label nefazodone treatment in patients with panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:544–546. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200010000-00009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Grant S, Fitton A. Risperidone. A review of its pharmacology and therapeutic potential in the treatment of schizophrenia. Drugs. 1994;48:253–273. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448020-00009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Drugs. 1994;48:253–273. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199448020-00009. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Prosser JM, Yard S, Steele A, Cohen LJ, Galynker II. A comparison of low-dose risperidone to paroxetine in the treatment of panic attacks: a randomized, single-blind study. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Kim H, McGrath BM, Silverstone PH. A review of the possible relevance of inositol and the phosphatidylinositol second messenger system (PI-cycle) to psychiatric disorders--focus on magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) studies. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2005;20:309–326. doi: 10.1002/hup.693. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Benjamin J, Levine J, Fux M, Aviv A, Levy D, Belmaker RH. Double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial of inositol treatment for panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1084–1086. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1084. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Palatnik A, Frolov K, Fux M, Benjamin J. Double-blind, controlled, crossover trial of inositol versus fluvoxamine for the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:335–339. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Palatnik A, Frolov K, Fux M, Benjamin J. Double-blind, controlled, crossover trial of inositol versus fluvoxamine for the treatment of panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;21:335–339. doi: 10.1097/00004714-200106000-00014. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Shekhar A, Keim SR. LY354740, a potent group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist prevents lactate-induced panic-like response in panic-prone rats. Neuropharmacology. 2000;39:1139–1146. doi: 10.1016/S0028-3908(99)00215-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

63. Javitt DC. Glutamate as a therapeutic target in psychiatric disorders. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:984–997. 979. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001551. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Grillon C, Cordova J, Levine LR, Morgan CA., 3rd Anxiolytic effects of a novel group II metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist (LY354740) in the fear-potentiated startle paradigm in humans. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:446–454. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1444-8. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Schoepp DD, Wright RA, Levine LR, Gaydos B, Potter WZ. LY354740, an mGlu2/3 receptor agonist as a novel approach to treat anxiety/stress. Stress. 2003;6:189–197. doi: 10.1080/1025389031000146773. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

66. Bergink V, Westenberg HG. Metabotropic glutamate II receptor agonists in panic disorder: a double blind clinical trial with LY354740. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;20:291–293. doi: 10.1097/00004850-200511000-00001. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

67. Rorick-Kehn LM, Perkins EJ, Knitowski KM, Hart JC, Johnson BG, Schoepp DD, et al. Improved bioavailability of the mGlu2/3 receptor agonist LY354740 using a prodrug strategy: in vivo pharmacology of LY544344. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;316:905–913. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.091926. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Kellner M, Muhtz C, Stark K, Yassouridis A, Arlt J, Wiedemann K. Effects of a metabotropic glutamate(2/3) receptor agonist (LY544344/LY354740) on panic anxiety induced by cholecystokinin tetrapeptide in healthy humans: preliminary results. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:310–315. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2025-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:310–315. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2025-1. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

69. Crepeau AZ, Treiman DM. Levetiracetam: a comprehensive review. Expert Rev Neurother. 2010;10:159–171. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Mula M, Pini S, Cassano GB. The role of anticonvulsant drugs in anxiety disorders: a critical review of the evidence. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;27:263–272. doi: 10.1097/jcp.0b013e318059361a. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Lamberty Y, Falter U, Gower AJ, Klitgaard H. Anxiolytic profile of the antiepileptic drug levetiracetam in the Vogel conflict test in the rat. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;469:97–102. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(03)01724-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. Papp LA. Safety and efficacy of levetiracetam for patients with panic disorder: results of an open-label, fixed-flexible dose study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:1573–1576. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v67n1012. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

clinical phenomena and treatment options

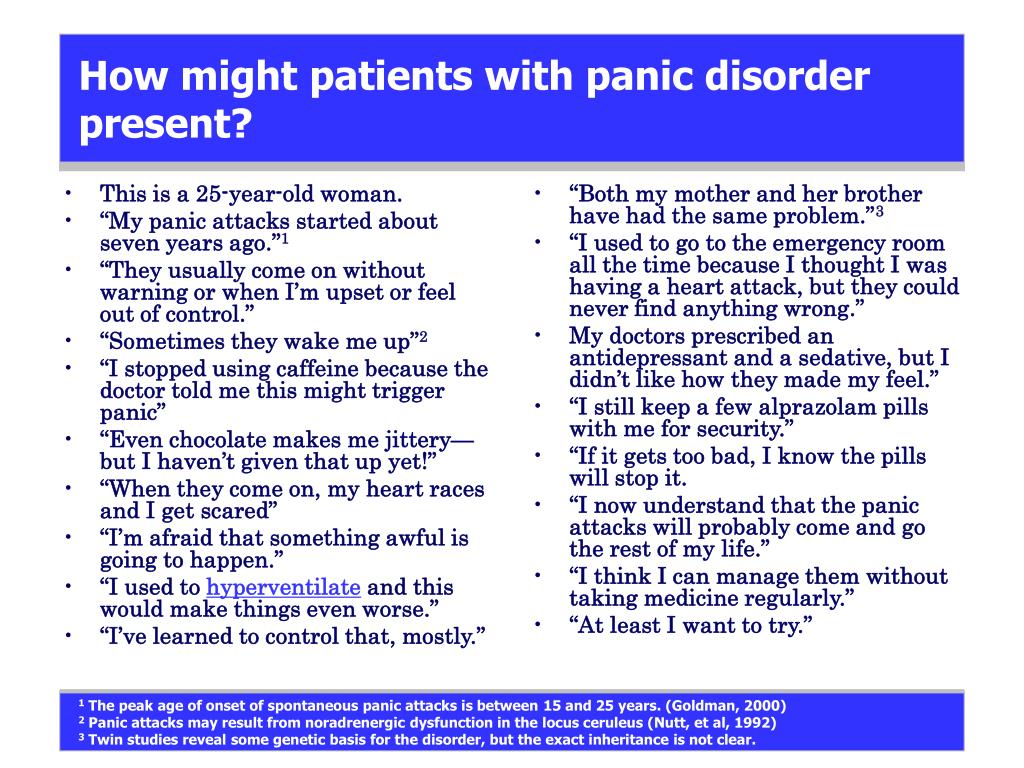

Panic disorder is an anxiety-related mental disorder. It is manifested by recurring sudden attacks, called panic attacks.

It is manifested by recurring sudden attacks, called panic attacks.

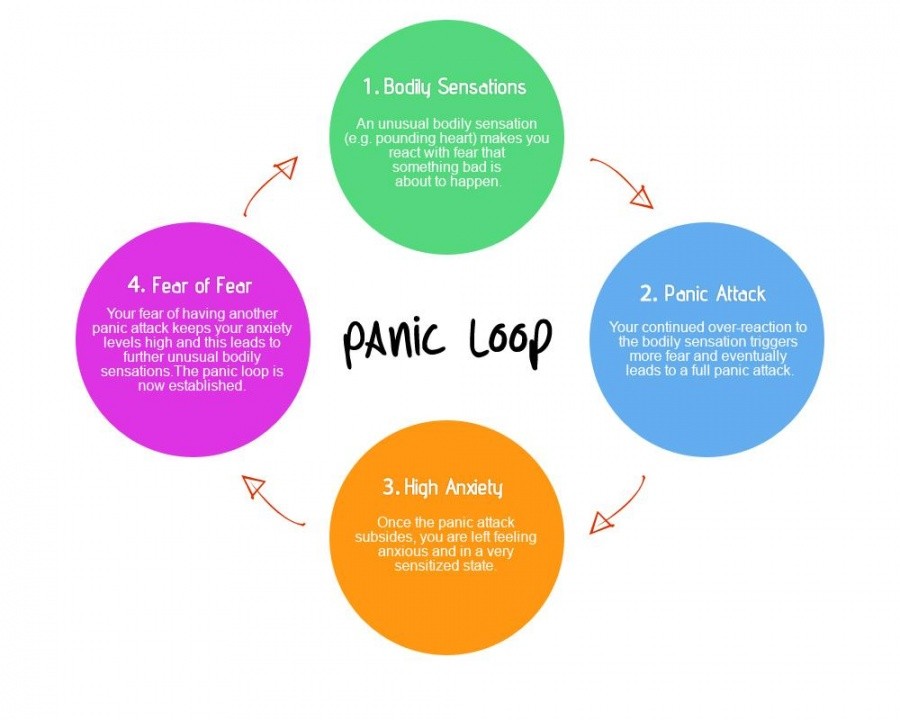

Panic attacks can be isolated, and only when they reappear and other symptoms are added, the presence of a panic disorder is stated.

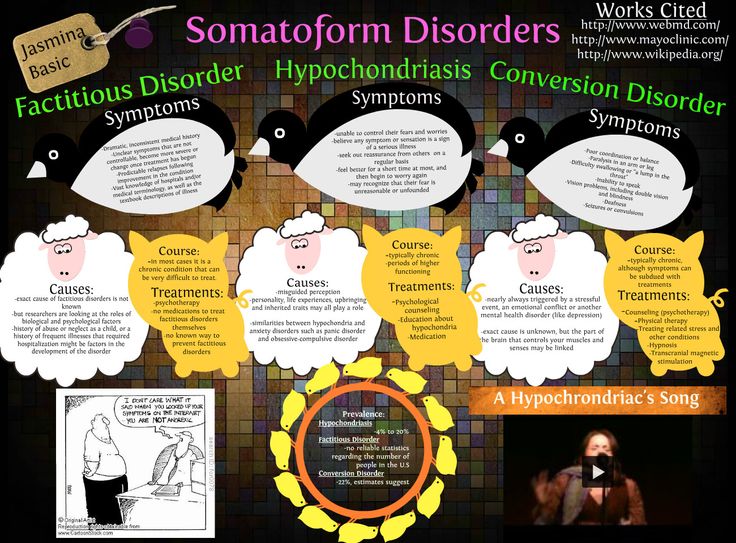

Comorbidity

Panic states are often accompanied by agoraphobia: 30-50% of cases in population studies and up to 75% of clinical observations [1].

Notably, the ICD-10 and DSM deal with the relationship between panic disorder and agoraphobia in the opposite way. In the ICD-10, agoraphobia (F40.0) is considered primary, which can either be combined with panic disorder (F41.0) or develop independently. In the DSM-IV classification, panic disorder is considered primary, which may be accompanied by agoraphobia or occur on its own. The DSM-5 does not address the issue of primacy, but the description of agoraphobia, as in the DSM-IV, follows the description of the panic state and states the frequent comorbidity of both disorders.

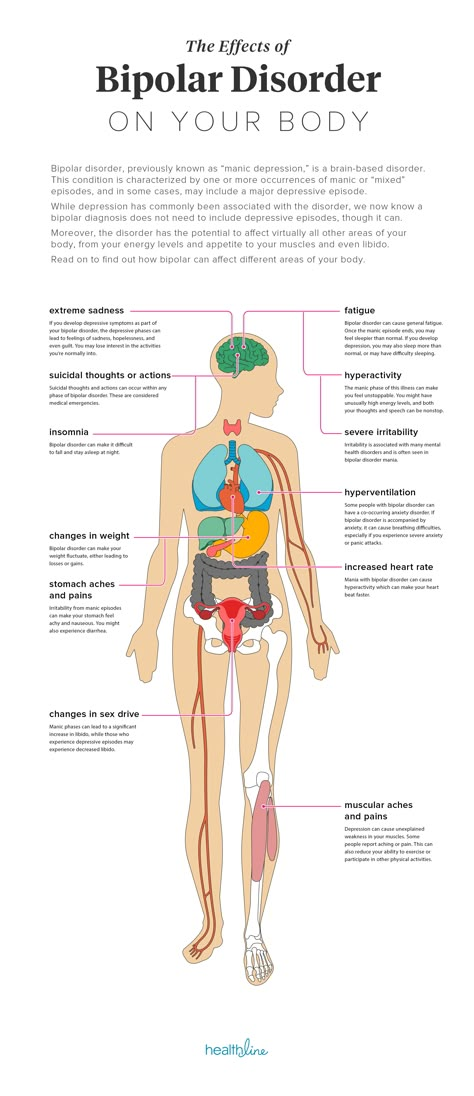

The list of the most common mental disorders comorbid with panic also includes (in descending order of frequency) depression - 68%, other anxiety disorders - 50%, alcohol abuse - 30%, bipolar affective disorder - 20% [1]. In addition, panic disorder may be accompanied by visceral disorders (eg, mitral valve prolapse) and diseases of the nervous system.

It has been shown that single panic attacks are rarely complicated by comorbid disorders, while repeated attacks are much more likely to lead to the appearance of other mental disorders, and with a formed panic disorder, the frequency of psychiatric comorbidity is at least 80% [2].

According to R. Kessler et al. [3], the frequency of psychiatric comorbidity in four groups of patients with panic conditions (isolated panic attacks, panic attacks with agoraphobia without signs of panic disorder, panic disorder without agoraphobia, panic disorder with agoraphobia) progressively increases from the first group to the fourth [3].

Epidemiology

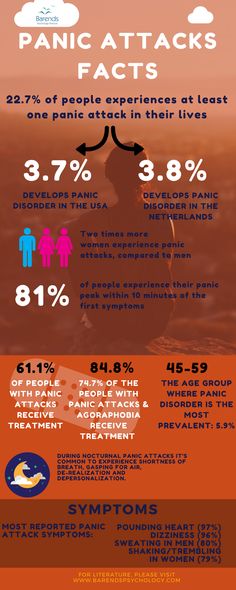

According to the epidemiological study of psychiatric comorbidity (National Comorbidity Survey), in the United States, panic disorder develops at least once in a lifetime in 5% of women and 2% of men [4].

It appears that the prevalence of panic disorder is much lower than the prevalence of panic attacks; in addition, there are indicators of the prevalence of isolated panic attacks and attacks accompanied by agoraphobia.

An American study conducted in 2006 [3] included 9282 people aged at least 18 years. It allowed us to identify, in accordance with the DSM-IV criteria, indicators of the prevalence of the following panic phenomena during the life: isolated panic attacks - in 22.7% of the persons included in the study, panic attacks in combination with agoraphobia, but without signs of panic disorder - in 0.8 %, panic disorder without agoraphobia in 3.74%, panic disorder with agoraphobia in 1. 1%. At the same time, such indicators as the frequency of panic attacks, their number during life and duration, measured in years, progressively increased from the first of the listed groups to the fourth. Similarly, the severity of panic symptoms increased; the frequency of moderate and severe forms approached 90% in panic disorder in combination with agoraphobia and did not exceed 7% in isolated panic attacks [3].

1%. At the same time, such indicators as the frequency of panic attacks, their number during life and duration, measured in years, progressively increased from the first of the listed groups to the fourth. Similarly, the severity of panic symptoms increased; the frequency of moderate and severe forms approached 90% in panic disorder in combination with agoraphobia and did not exceed 7% in isolated panic attacks [3].

Cross-national study [2] involving 142,949 patients aged 18 years and older from 24 countries (Netherlands, New Zealand, Romania, USA, South Africa, Australia, Bulgaria, Portugal, Israel, Iraq, Spain, Brazil, Mexico, UK, Italy, Belgium, Nigeria, Japan, China, Lebanon, Poland, France, Peru, Colombia) showed that the average prevalence of panic attacks is 13.2%; in 66.5% of individuals with panic attacks, the latter are recurrent, but only in 12.8% of patients the clinical picture meets the criteria for diagnosing panic disorder according to DSM-5 [2].

Etiology

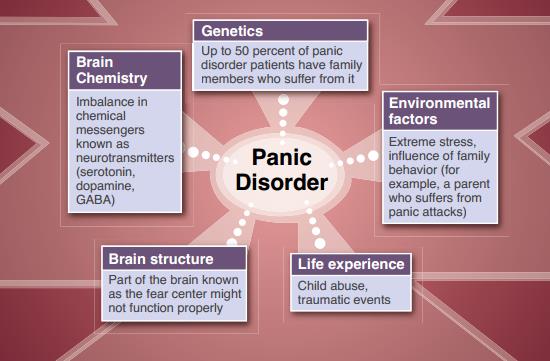

It is believed that a combination of hereditary predisposition and special mental vulnerability plays a key role in the onset of panic and the formation of panic disorder. Moreover, hereditary predisposition is often common for both anxiety and mood disorders.

Moreover, hereditary predisposition is often common for both anxiety and mood disorders.

According to various sources, hereditary burden of anxiety disorders in people with panic conditions is characterized by a wide range - from 25 to 50% [1].

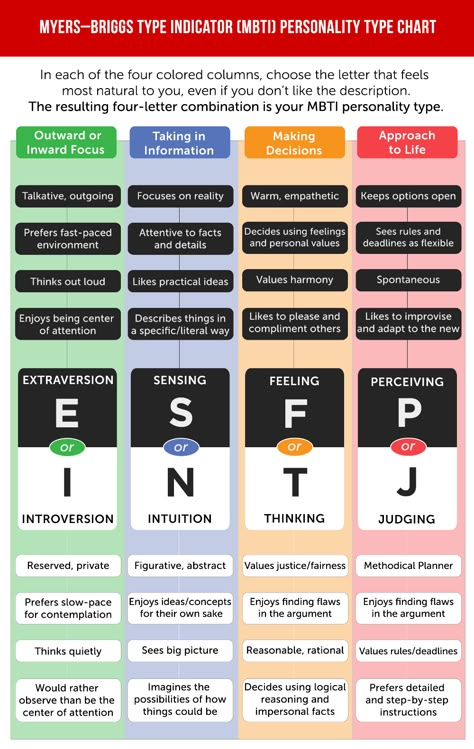

The special mental vulnerability that forms the susceptibility to panic disorder is associated with a number of personality traits and psychological characteristics, which include neuroticism, extraversion, increased sensitivity to emotional distress and intolerance to uncertainty [5-8].

There is reason to believe that one of the key biological factors predisposing to panic is a change in the activity of various neurotransmitter systems. The most convincing of the etiological hypotheses are, in our opinion, the hypotheses of impaired serotonin neurotransmission and GABA neurotransmission, the legitimacy of which is partly proved by the effectiveness of serotonergic antidepressants and benzodiazepines, which are GABA agonists A receptor, in the treatment of panic disorder.

Clinical manifestations and diagnosis

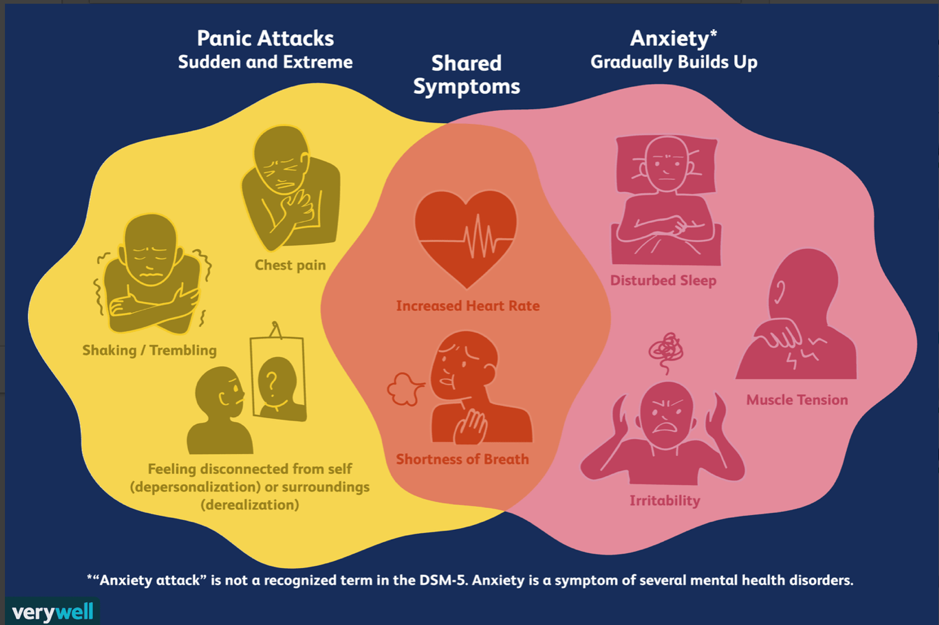

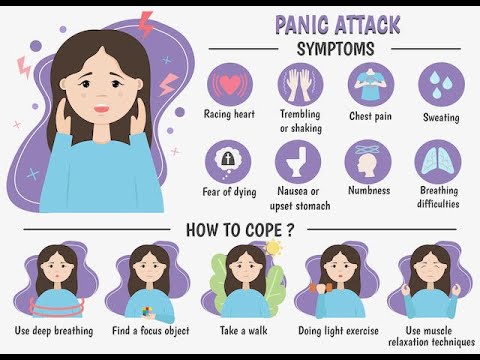

A panic attack is understood as a sudden (in a calm or anxious state) attack of intense fear or intense discomfort, reaching a maximum expression within a few minutes.

According to DSM-5 criteria 1 , a diagnosis of panic attack is possible if at least 4 out of 13 symptoms are present [9]: cardiopalmus; tremor; shortness of breath or shortness of breath; feeling of suffocation; chest pain or discomfort; nausea or stomach discomfort; dizziness, unsteadiness, lightness in the head or weakness; chills or feeling hot; paresthesia; derealization or depersonalization; fear of losing control or going crazy; fear of death.

The DSM-5 emphasizes that a panic attack is not a mental disorder per se and can occur in a variety of anxiety and other psychiatric disorders, as well as physical and neurological conditions.

The above (far from complete) list of possible symptoms of panic attacks makes it understandable that patients suffering from them often seek help not only from psychiatrists, but also from neurologists and internists.

Statement of panic disorder, in accordance with the DSM-5 criteria, is considered possible in the presence of 4 signs, denoted by Latin letters from A to D [9]:

A . Recurrent sudden panic attacks, manifested by four or more symptoms from the list above.

B . At least one of the attacks results in one or both of the following occurring for 1 month or more:

a) persistent fear or concern about the possibility of new attacks or their consequences;

b) inappropriate behavior changes to avoid the possibility of new attacks.

C . The symptoms are not related to the physiological effects of substance use or physical ill health.

D . The symptoms cannot be better explained by another mental disorder, including an anxiety disorder or a reaction to a fearful social situation.

Treatment

Benzodiazepines and antidepressants have proven clinical efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder and are included in most international and national clinical guidelines.

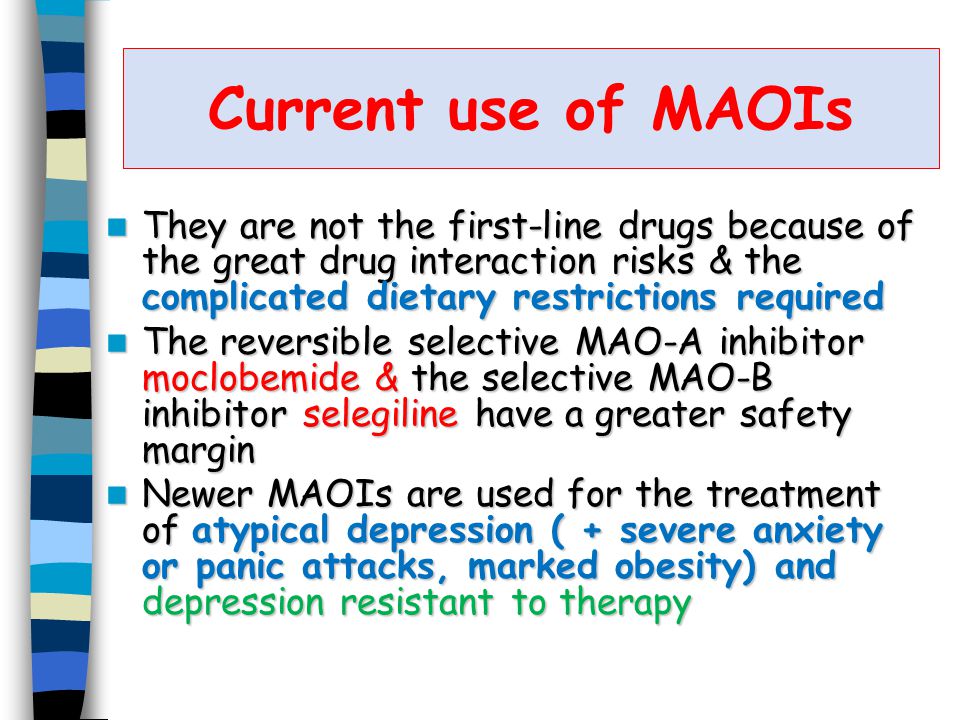

According to D. Semple and R. Smyth [1], the data obtained to date do not allow us to speak about the indisputable superiority in the effectiveness of benzodiazepines, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). Despite approximately equal clinical efficacy, the listed groups of drugs have obvious differences in purpose and tolerability, which makes it possible to distinguish both between benzodiazepines and any antidepressants, and between different groups of antidepressants.

Benzodiazepines are comparable to antidepressants in the treatment of panic disorder in major therapeutic endpoints, including panic attack frequency, global anxiety, and agoraphobic avoidance [10]. Benzodiazepines are characterized by a rapid onset of pharmacological action, which determines their successful use in the prevention and termination of a panic attack. The downside of the rapid effects of benzodiazepines is a possible withdrawal state, with increased anxiety upon discontinuation. Benzodiazepines can be added to antidepressants in the first weeks of treatment before the therapeutic effects of the latter appear in order to alleviate the condition of patients [11].

The downside of the rapid effects of benzodiazepines is a possible withdrawal state, with increased anxiety upon discontinuation. Benzodiazepines can be added to antidepressants in the first weeks of treatment before the therapeutic effects of the latter appear in order to alleviate the condition of patients [11].

Long-term use of benzodiazepines is undesirable due to their adverse effects on neuromotor and cognitive functions, as well as a certain risk of addiction and dependence.

The therapeutic potential of benzodiazepines in the treatment of panic disorder with comorbid mood disorders can be assessed in two ways: on the one hand, in eliminating anxiety, benzodiazepines lose to antidepressants in the possibility of influencing comorbid depression (antidepressants have a therapeutic effect on both types of disorders), and on the other hand, precisely due to the absence of a thymoanaleptic effect, benzodiazepines lack the ability to induce a manic state in patients prone to bipolar affective disorder.

It is believed that all benzodiazepines have similar efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder when prescribed at sufficiently high doses [12], however, in most clinical guidelines, alprazolam and clonazepam are primarily assigned specific “anti-panic” properties [13, 14].

Currently, three benzodiazepine tranquilizers are available in Russian practice suitable for the treatment of panic disorder: alprazolam and clonazepam already mentioned above, as well as phenazepam 2 .

Alprazolam has a proven ability to prevent and terminate a panic attack and can be used in short courses [14]. Among the disadvantages of alprazolam is the ability to cause addiction and dependence, which is associated with the rapid onset of its pharmacological effects. The high addictive potential of alprazolam and the frequency of its non-medical use are the reasons why this drug, along with oxycodone and hydrocodone 3 , is included in the triad of drugs, an overdose of which can cause death [15].

Clonazepam is primarily used in the treatment of myoclonic epilepsy 4 ; the second indication for its use is panic disorder. Like alprazolam, clonazepam effectively prevents and relieves panic attacks, while showing a more pronounced sedative effect.

The use of alprazolam and clonazepam in Russian clinical practice is significantly complicated due to the special rules for their storage and dispensing from pharmacies.

Phenazepam is the original domestic benzodiazepine derivative used for many decades in the treatment of anxiety and related disorders. Phenazepam exhibits a strong anxiolytic effect, making it possible to achieve a reduction in anxiety and a significant improvement in the condition of patients with anxiety disorders in at least 50% of cases and a moderate improvement in every fourth case [16]. In accordance with the research data of A.A. Pribytkov [17], phenazepam is comparable to sertraline in terms of the effectiveness of treatment of somatoform disorders, and the combination of them allows to achieve a more rapid improvement in the condition of patients with somatoform disorders than sertraline monotherapy. Along with the treatment of anxiety, phenazepam is prescribed to alleviate the state of alcohol withdrawal, as well as to prevent and treat delirium tremens. In addition, due to the pronounced anxiolytic effect, phenazepam enhances the effect of neuroleptics in the treatment of acute psychoses accompanied by severe anxiety, including psychoses in patients with schizophrenia.

Along with the treatment of anxiety, phenazepam is prescribed to alleviate the state of alcohol withdrawal, as well as to prevent and treat delirium tremens. In addition, due to the pronounced anxiolytic effect, phenazepam enhances the effect of neuroleptics in the treatment of acute psychoses accompanied by severe anxiety, including psychoses in patients with schizophrenia.

Low narcotic potential determines the relative safety of phenazepam in the treatment of panic disorder and other anxiety disorders 5 .

The undoubted practical advantage of phenazepam, in comparison with alprazolam and clonazepam, is the usual order of storage and facilitated dispensing from pharmacies, which greatly simplifies its use in clinical practice compared to the two mentioned tranquilizers.

Unlike benzodiazepines, antidepressants, when taken once or at the beginning of therapy, are not able to prevent or abort a panic attack. Moreover, in the first days of treatment, antidepressants (especially at an excessive initial dose) can cause or increase anxiety and sleep disturbances, and even cause a new panic attack, which, apparently, is explained by a sharp increase in serotonin neurotransmission. At the same time, long-term use of modern antidepressants in 70-80% of cases leads to a pronounced weakening, a significant decrease in the frequency or complete disappearance of panic attacks with a significantly less adverse effect on neuromotor and other cerebral and mental functions compared to benzodiazepines [18].

At the same time, long-term use of modern antidepressants in 70-80% of cases leads to a pronounced weakening, a significant decrease in the frequency or complete disappearance of panic attacks with a significantly less adverse effect on neuromotor and other cerebral and mental functions compared to benzodiazepines [18].

TCAs, MAOIs, SSRIs and SNRIs show approximately equal efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder panic conditions, but also any mental disorders that are indications for prescribing antidepressants, including depression and the entire spectrum of disorders associated with anxiety [1, 13, 14].

In accordance with the opinion of a number of authors [18, 19], it is for panic disorder (but not for other anxiety conditions) that SSRIs plus venlafaxine belonging to the SNRI category should be considered first-line treatment, despite the fact that in general SNRIs are somewhat inferior to SSRIs in terms of tolerability with close clinical efficacy. In addition to these drugs, antidepressants of other pharmacological groups, including mirtazapine, agomelatine, and vortioxetine, show some effectiveness in the treatment of panic disorder [20–22].

An indisputable advantage of antidepressants is their ability as a monotherapy to influence both panic disorder and its accompanying psychiatric disorders, including agoraphobia, other anxiety disorders, and depression.

Certain prospects in the treatment of panic disorder are associated with calcium channel modulators - gabapentin and pregabalin [22-24], although convincing data on the comparability of the clinical effects of these drugs with the clinical effects of benzodiazepines and antidepressants have not yet been obtained.

In cases of drug-resistant panic disorders, antipsychotics are used. In particular, it has been reported [25, 26] that risperidone and aripiprazole differ from placebo in the treatment of refractory anxiety disorders, including panic disorder. In this regard, a strategy has been developed to increase the insufficient therapeutic effect of first-line treatments with atypical antipsychotics. It should be borne in mind that, despite the ability of antipsychotics to enhance the effects of benzodiazepines and antidepressants, these drugs should by no means be used as the first choice in the treatment of panic disorder, which, unfortunately, is often observed in Russian psychiatric practice.

Along with psychopharmacological approaches, psychotherapy is used in the treatment of panic disorder.

In a Cochrane review based on a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of 16 studies selected from four resources (Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, MEDLINE, Embase and PsycINFO), H. Imai et al. [27] report no difference in the effectiveness of psychotherapy compared with SSRIs, TCAs, other antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and antidepressants alone or with a combination of antidepressants and benzodiazepines. The authors report the need for further research in this direction and suggest that antidepressant-assisted psychotherapy may be more effective than drug-free psychotherapy.

According to another point of view [28], based on the analysis of the results of treatment of 150 patients with panic disorder, both with and without accompanied by agoraphobia of varying severity, the effectiveness of the combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in combination with SSRIs is only marginally effective. outperforms isolated CBT. It is noted that the effect of CBT occurs later than the effect of CPT + SSRIs or SSRIs, and stops a little earlier. The results of this and some other studies [29, 30] suggest that the combination of pharmacotherapy and CBT is the best approach to the treatment of panic disorder.

outperforms isolated CBT. It is noted that the effect of CBT occurs later than the effect of CPT + SSRIs or SSRIs, and stops a little earlier. The results of this and some other studies [29, 30] suggest that the combination of pharmacotherapy and CBT is the best approach to the treatment of panic disorder.

A certain counterbalance to the pharmacotherapeutic concept of treatment of panic conditions is the statement [31] that CBT is the first line treatment for panic disorder, and only in the absence or limited availability of this method should drugs be prescribed, but this postulate has not yet been received. proper scientific confirmation.

Thus, panic disorder is characterized by a sufficient prevalence, a high frequency of comorbidity with other mental disorders, and often manifests itself with neurological and visceral symptoms, which is the reason why patients often turn to neurologists and internists.

Benzodiazepines and antidepressants have proven clinical efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder, the former being more likely to prevent and terminate panic attacks, while the latter are preferred for long-term treatment.

The first-line antidepressants in the treatment of panic disorder (as well as other anxiety-associated disorders and depression), due to the optimal ratio of efficacy and tolerability, are SSRIs; if necessary, antidepressants of other pharmacological groups can be used.

When panic disorder has not been successfully treated with first-line drugs, their effects are enhanced by atypical antipsychotics.

Psychotherapy is a distinct alternative and adjunct to antidepressants in the treatment of panic disorder, with CBT being the first choice.

Conflict of interest: the article was prepared with the support of the pharmaceutical company Valenta.

1 Diagnosis of panic disorder according to ICD-10 is not considered here due to the expected appearance of the next, 11th, version of the classifier; in addition, the DSM-5 criteria, according to the author of the article, are more clear and more in line with clinical reality than the ICD-10 criteria.

2 Sibazon, a generic drug of diazepam, is not considered in this article.

3 Oxycodone and hydrocodone are opioid analgesics approved in the US for the outpatient treatment of chronic pain.

4 Widespread use of clonazepam in domestic epileptology, which goes beyond its prescription for myoclonic epilepsy, is considered by some experts to be unjustified.

5 The combined use of alcohol and phenazepam in cases of complicated alcohol dependence most often occurs in patients with anxiety-hypochondriacal warehouse and, as is usually the case with benzodiazepines, reflects a medical need for relief from anxiety and insomnia.

6 The first antidepressants to demonstrate clinical efficacy in the treatment of panic disorder were the typical TCAs imipramine and the MAOI phenelzine.

Benzodiazepines for panic disorder in adults

Why is this review important?

Panic disorder is common in the general population and is characterized by recurrent, unexpected panic attacks consisting of a wave of intense fear that peaks within minutes. Agoraphobia often develops after one or more panic attacks and is the fear of being in situations where escape may be difficult or help unavailable. Psychological interventions and medications are used to treat panic disorder, often in combination. Benzodiazepines are often used in the treatment of panic disorder, although they are not usually recommended as a first line treatment. Benzodiazepines have a rapid onset of action but also a high risk of dependence and withdrawal symptoms.

Agoraphobia often develops after one or more panic attacks and is the fear of being in situations where escape may be difficult or help unavailable. Psychological interventions and medications are used to treat panic disorder, often in combination. Benzodiazepines are often used in the treatment of panic disorder, although they are not usually recommended as a first line treatment. Benzodiazepines have a rapid onset of action but also a high risk of dependence and withdrawal symptoms.

Who might be interested in this review?

Patients and general practitioners.

What questions does this review seek to answer?

How effective is benzodiazepine treatment versus placebo (sham intervention) in treating panic disorder with or without agoraphobia?

How acceptable are benzodiazepines compared to placebo in the treatment of panic disorder with or without agoraphobia?

How many people with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia treated with benzodiazepines experience side effects compared to placebo?

What studies were included in the review?

We searched electronic databases and registries to find all relevant studies. We included only randomized controlled trials (a type of study in which participants are assigned to groups at random) that compared benzodiazepine treatment with placebo in adults diagnosed with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. We included only those studies in which patients and clinicians did not know what treatment they were receiving. We included 24 studies with 4,233 participants in our review.

We included only randomized controlled trials (a type of study in which participants are assigned to groups at random) that compared benzodiazepine treatment with placebo in adults diagnosed with panic disorder with or without agoraphobia. We included only those studies in which patients and clinicians did not know what treatment they were receiving. We included 24 studies with 4,233 participants in our review.

What does the evidence from this review say?

We found consistent evidence for a possible benefit of benzodiazepines in reducing panic symptoms and the number of participants who stopped treatment. In addition, benzodiazepines may improve social functioning more than placebo. However, there may be more withdrawals from studies due to side effects, as well as participants who experienced at least one side effect of benzodiazepine treatment. We found several major limitations in the design of the included studies. For example, in at least a few studies, participants and clinicians could guess which group the participants fell into, which means that some trials were not actually blind.