Fight flight freeze fawn test

Fight, Flight, Freeze, or Fawn? Understanding Trauma Responses

Trauma, whether it’s momentary or long term, affects people in different ways. This probably isn’t news to you.

But did you know four distinct responses can help explain how your experiences show up in your reactions and behavior?

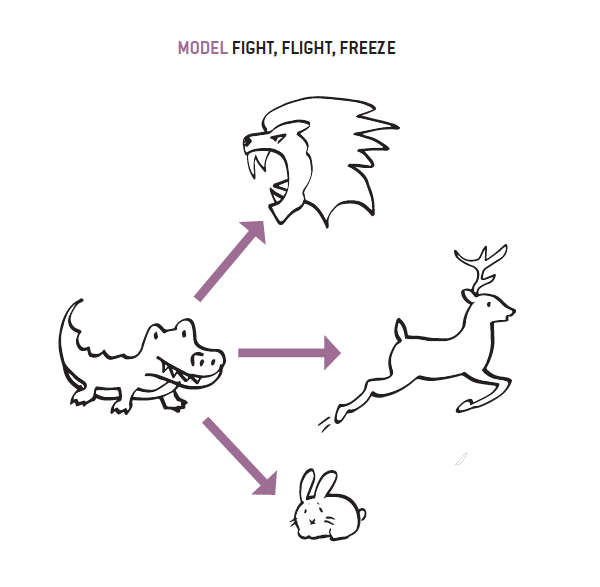

First, there’s fight-or-flight, the one you’re probably most familiar with. In basic terms, when you encounter a threat, you either resist or retaliate, or simply flee.

Maybe you’ve also heard this called fight, flight, or freeze. You can think of the freeze response as something akin to stalling, a temporary pause that gives your mind and body a chance to plan and prepare for your next steps.

But your response to trauma can go beyond fight, flight, or freeze.

The fawn response, a term coined by therapist Pete Walker, describes (often unconscious) behavior that aims to please, appease, and pacify the threat in an effort to keep yourself safe from further harm.

We’ll explain these four trauma responses in depth below, plus offer some background on why they show up and guidance on recognizing (and navigating) your own response.

As you might already know, trauma responses happen naturally.

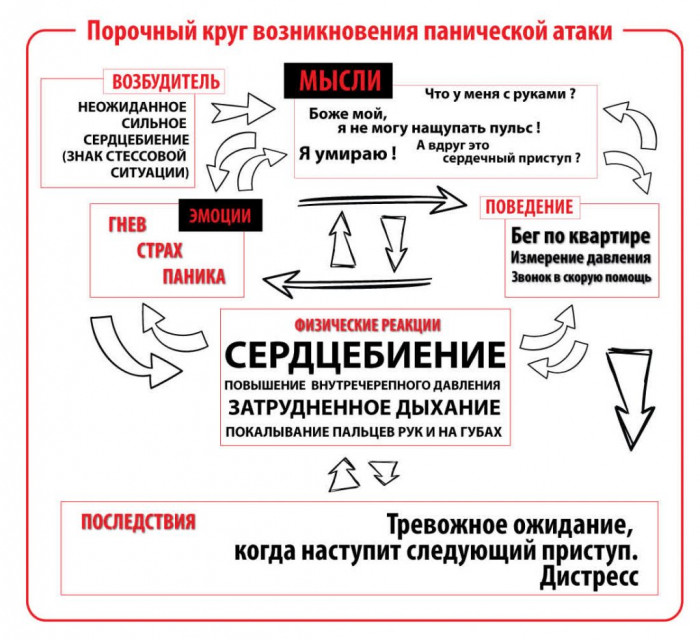

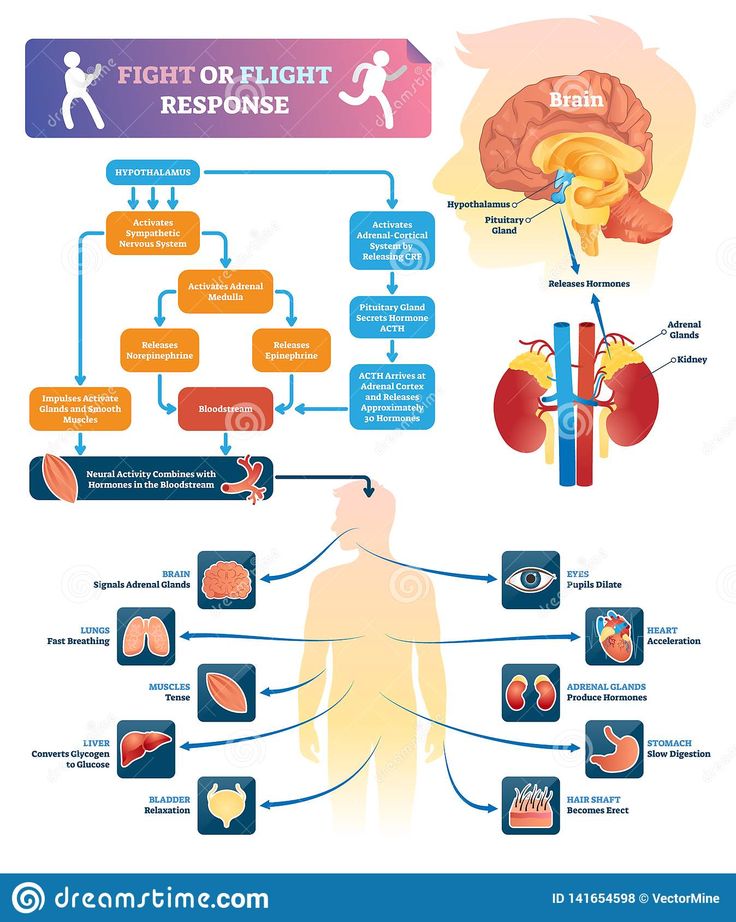

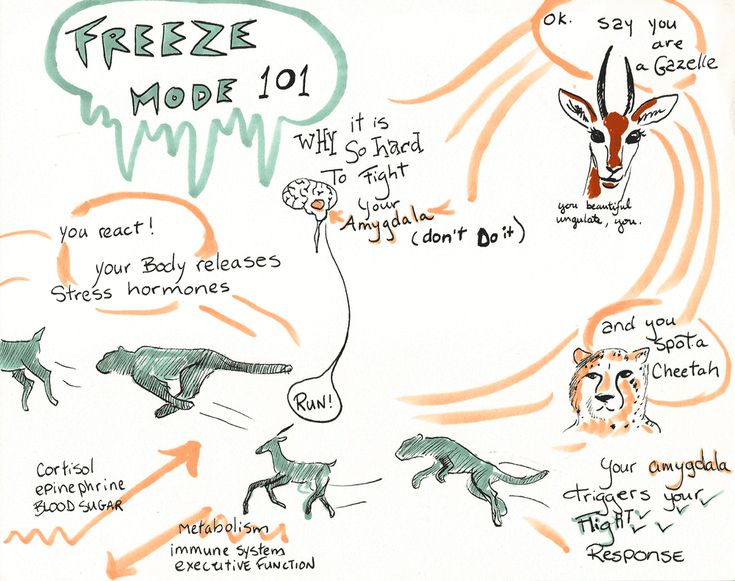

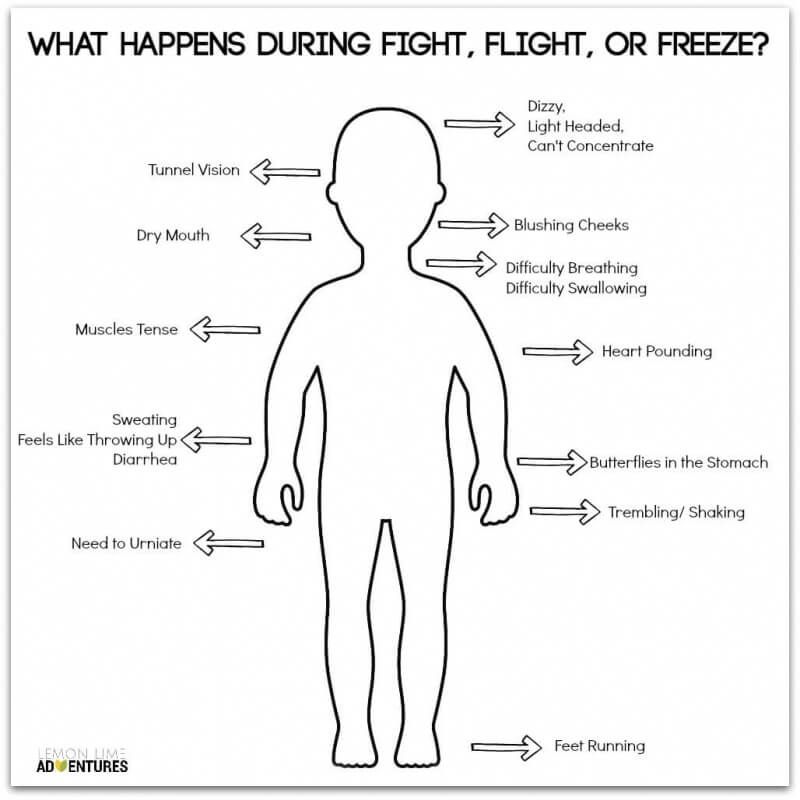

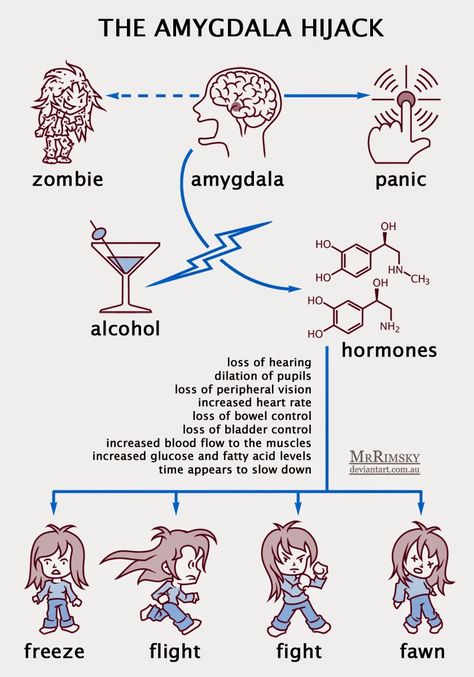

When your body recognizes a threat, your brain and autonomic nervous system (ANS) react quickly, releasing hormones like cortisol and adrenaline.

These hormones trigger physical changes that help prepare you to handle a threat, whether it involves actual physical or emotional danger, or perceived harm.

You might, for example:

- argue with a co-worker treating you unfairly

- flee from the path of a car running a red light

- freeze when you hear an unexpected noise in the dark

- keep quiet about how you really feel to avoid starting a fight

It’s also possible to have an overactive trauma response. In a nutshell, this means day-to-day occurrences and events most people don’t find threatening can trigger your go-to stress response, whether that’s fight, flight, freeze, fawn, or a hybrid.

Overactive trauma responses are pretty common among survivors of trauma, particularly those who experienced long-term abuse or neglect.

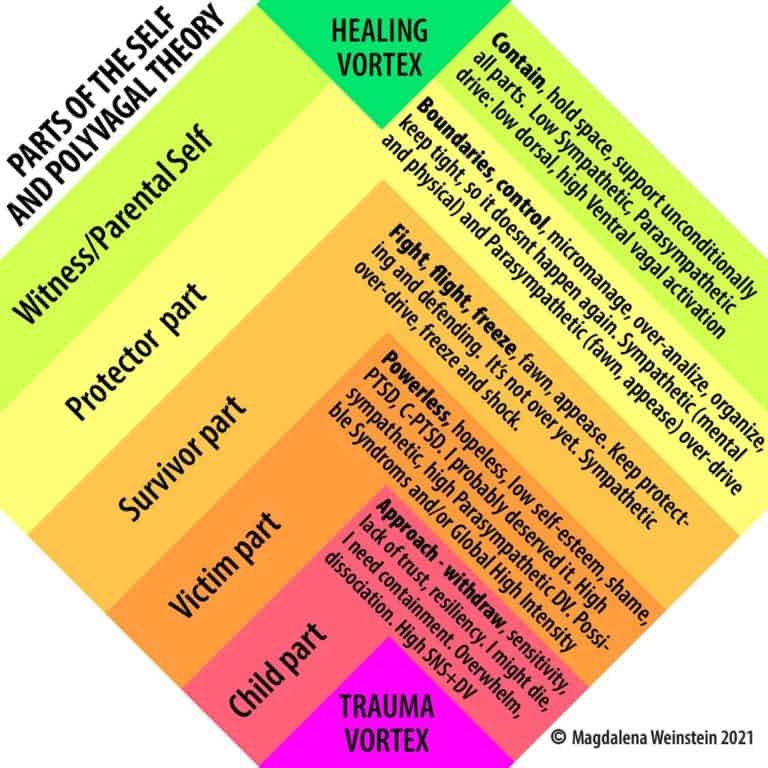

In fact, an overactive trauma response — getting stuck in fight, flight, freeze, or fawn, in other words — may happen as part of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or complex post-traumatic stress disorder (C-PTSD).

How does attachment factor in?

Your attachment style reflects your childhood bond with your parent or primary caregiver. This early relationship plays an important role in how you relate to others over the course of your life.

If your caregiver generally took care of your needs and you could count on them for physical and emotional support, you probably grew up with the confidence to trust others and build healthy relationships with friends and partners.

You’ll also, as Walker’s theory suggests, find it mostly possible to weather stress, challenges, and other threats by reaching for the trauma response that works best in a given situation.

Living through repeated abuse, neglect, or other traumatic circumstances in childhood can make it harder to use these responses effectively.

Instead, you might find yourself “stuck” in one mode, coping with conflict and challenges just as you coped in childhood: favoring the response that best served your needs by helping you escape further harm.

This can, without a doubt, further complicate the process of building healthy relationships.

When you’ve experienced emotional abuse or physical neglect, a number of factors can affect the way you respond:

- the type of trauma

- the specific pattern of neglect and abuse

- your role in the family and relationships with other family members

- genetics, including personality traits

Example

Say you want to protect your younger siblings from your parent’s anger and aggression. You don’t want to flee and leave them alone. But you also know you have to take action somehow, which rules out freezing.

This leaves two options:

- fight, or taking action against your parent in some way

- fawn, or doing something to soothe them and keep them calm so they won’t become violent

You might naturally gravitate toward one or the other based on your underlying personality traits, but the situation can also make a difference. If your parent is much bigger and stronger, and you can’t think of any way to subtly take action, you might resort to fawning.

If the response proves effective, it can easily become automatic — in all your relationships, even years down the line.

Now, here’s a closer look at the four main reactions.

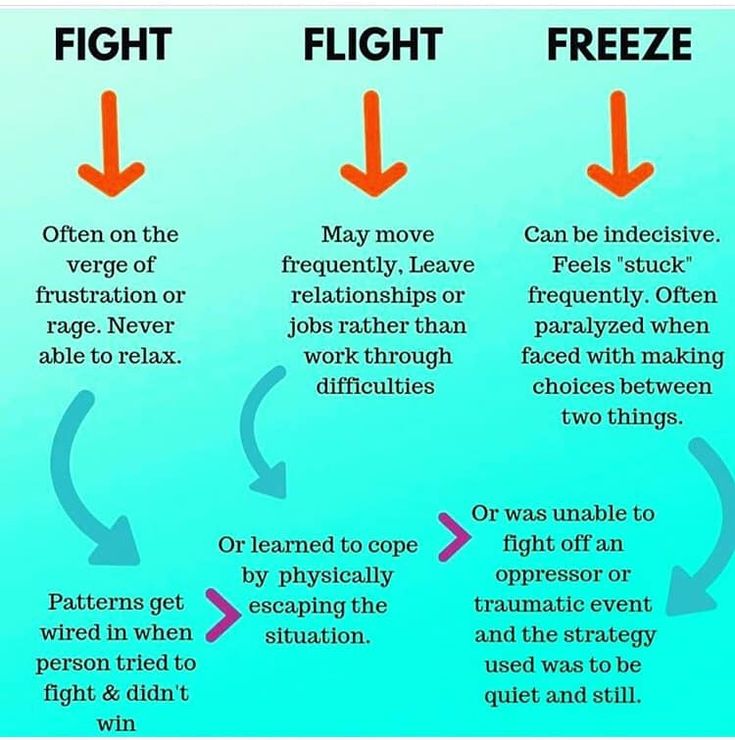

This response tends to stem from the unconscious belief that maintaining power and control over others will lead to the acceptance, love, and safety you need but didn’t get in childhood, according to Walker.

This response tends to show up more commonly when your caregivers:

- didn’t provide reasonable and healthy limits

- gave you whatever you asked for

- shamed you

- demonstrated narcissistic rage, bullying, or disgust

While fight often refers to actual physical or verbal aggression, it can encompass any action you take to stand up to a threat or negate it, like:

- making a public social media post after your partner cheats to let everyone know what they did

- shouting at your friend when they accidentally mention something you wanted to keep private

- spreading a rumor about a co-worker who criticized your work

- refusing to speak with your partner for a week when they lose your favorite sunglasses

Walker also notes that a fixed fight response can underlie narcissistic defenses. Indeed, experts recognize childhood abuse as a potential cause of narcissistic personality disorder, though other factors also play a part.

Indeed, experts recognize childhood abuse as a potential cause of narcissistic personality disorder, though other factors also play a part.

In your relationships, you might tend more toward ambivalent or avoidant attachment styles.

A flight response, in short, is characterized by the desire to escape or deny pain, emotional turmoil, and other distress.

You might find yourself trapped in flight mode if, as a child, escaping your parents helped you dodge most of their unkindness and ease the impact of the abuse you experienced.

Escape might take a literal form:

- staying longer hours at school and friends’ houses

- wandering the neighborhood

Or a more figurative one:

- throwing yourself into your studies to occupy yourself

- creating endless plans for escape

- drowning out arguments with music

As an adult, you might continue to flee challenging or difficult situations by:

- working toward perfection in all aspects of life so no one can criticize or challenge you

- ending relationships when you feel threatened, before the other person can break up with you

- avoiding conflict, or any situation that brings up difficult or painful emotions

- using work, hobbies, or even alcohol and substances to fend off feelings of fear, anxiety, or panic

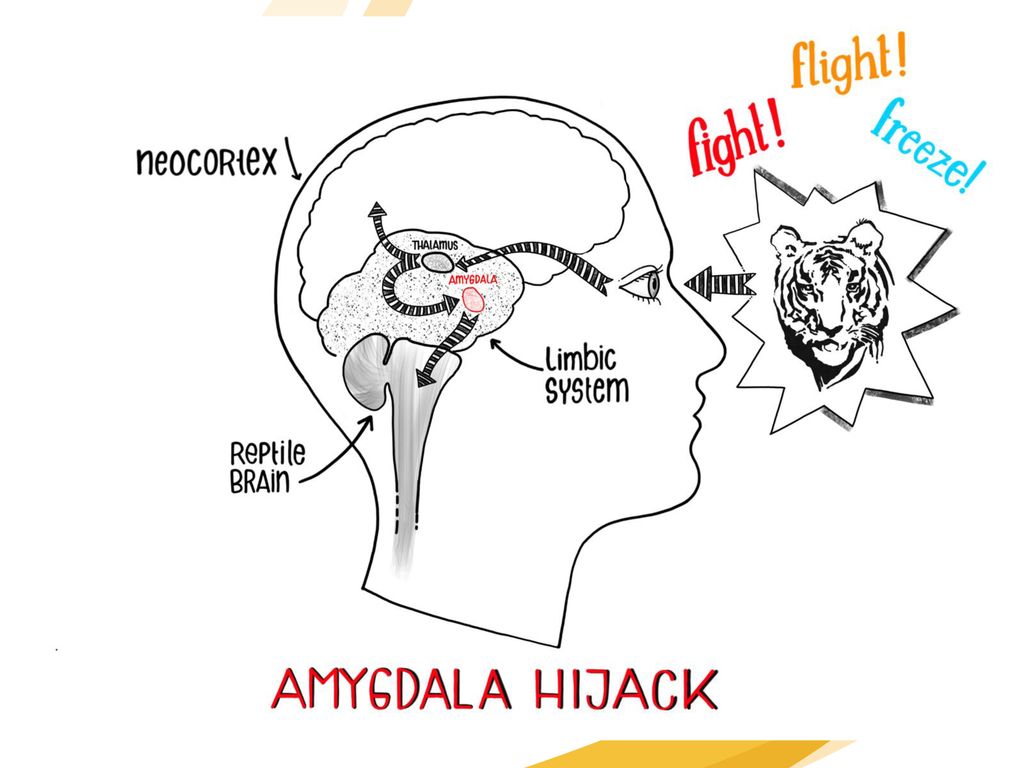

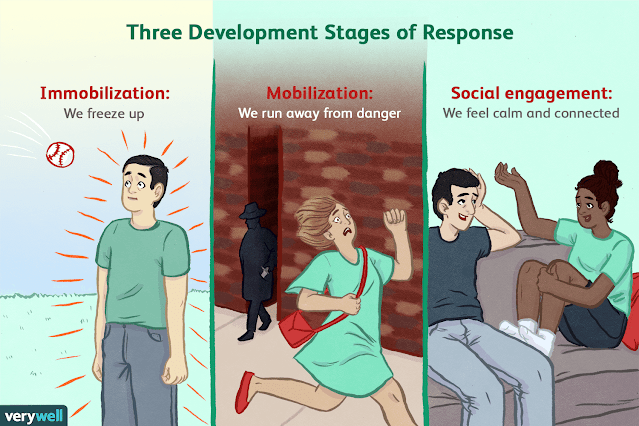

The freeze response serves as a stalling tactic. You brain presses the “pause” button but remains hypervigilant, waiting and watching carefully until it can determine whether fleeing or fighting offers a better route to safety.

You brain presses the “pause” button but remains hypervigilant, waiting and watching carefully until it can determine whether fleeing or fighting offers a better route to safety.

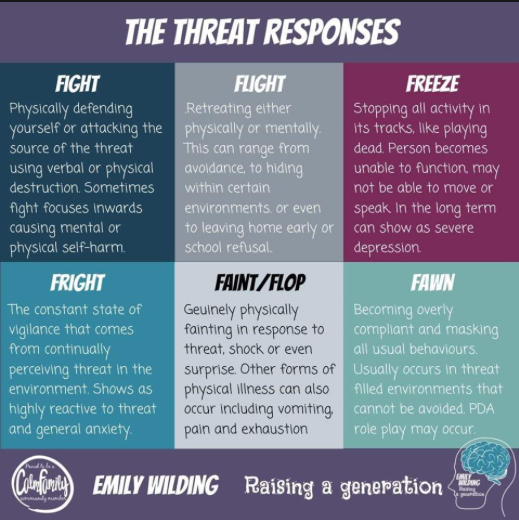

Some experts have pointed out this response actually takes place first, before you decide to flee or fight. And when either action seems less than feasible? You might then “flop” in response to your fright.

What’s the ‘flop’ response?

Your body might go limp. You might even dissociate or faint, which could appear to benefit you in the moment:

- If you pass out, you don’t experience the trauma directly.

- If you dissociate, you might feel removed or mentally disconnected from the situation, or fail to remember it fully.

- If you go limp, the person attacking or abusing you might use less force or even lose interest completely. As a result, you might find it easier to get to safety.

Of course, flopping (also known as tonic immobility) isn’t exactly a good thing, though it does serve some purpose.

It can leave you completely numb, unable to move or call out for help. Plus, while it might seem helpful to lack memories of abuse, those blank spaces can still cause emotional distress.

A long-term freeze response can come to resemble a mask you use to protect yourself when you can’t identify any means of fighting back or escaping.

Behind the mask, you might:

- use fantasy or imagination to escape day-to-day distress

- prefer solitude and avoid close relationships

- hide emotions and feelings

- physically detach from the world through sleep, or by staying in your room or house

- mentally “check out” from situations that feel painful or stressful

Walker identified a fourth trauma response through his experiences helping survivors of childhood abuse and trauma.

This response, which he termed “fawning,” offers an alternate path to safety. You escape harm, in short, by learning to please the person threatening you and keep them happy.

In childhood, this might involve:

- ignoring your own needs to take care of a parent

- making yourself as useful and helpful as possible

- neglecting or failing to develop your own self-identity

- offering praise and admiration, even when they criticize you

You might learn to fawn, for example, to please a narcissistically defended parent, or one whose behavior you couldn’t predict.

Giving up your personal boundaries and limits in childhood may have helped minimize abuse, but this response tends to linger into adulthood, where it often drives codependency or people-pleasing tendencies.

You might:

- agree to whatever your partner asks of you, even if you’d rather not

- constantly praise a manager in hope of avoiding criticism or negative feedback

- feel as if you know very little about what you like or enjoy

- avoid sharing your own thoughts or feelings in close relationships for fear of making others angry

- have few, if any, boundaries around your own needs

Learn more about the fawn response.

Trauma doesn’t just affect you in the moment. More often, it has long lasting effects that can disrupt well-being for years to come.

Just one instance of abuse can cause deep pain and trauma. Repeated abuse can take an even more devastating toll, damaging your ability to form healthy friendships and relationships, not to mention your physical and mental health.

But you can work through trauma and minimize its impact on your life.

Recognizing your trauma response is a great place to start. Just keep in mind, though, that your response may not fall neatly into one of these four categories.

As Walker’s theory explains, most people navigating long-term trauma drift toward more of a hybrid response, such as fawn-flight or flight-freeze.

Therapy is often key

While help from loved ones can always make a difference for trauma and abuse recovery, most people need a little more support. In fact, PTSD and C-PTSD are recognized mental health conditions that generally don’t improve without professional support.

With guidance from a mental health professional, you can:

- challenge and break out of a fixed trauma response

- learn to access more effective responses when facing actual threats

- begin healing emotional pain

- learn to establish healthy boundaries

- reconnect with your sense of self

Learn more about finding the right therapist.

Your trauma response may be a relic of a painful childhood, but it’s not set in stone.

Support from a trained therapist can go a long way toward helping you address deep-seated effects of past trauma, along with any mental health symptoms you experience as a result.

Crystal Raypole writes for Healthline and Psych Central. Her fields of interest include Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health, along with books, books, and more books. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues. She lives in Washington with her son and a lovably recalcitrant cat.

Fight, Flight, Freeze, Fawn: Examining The 4 Trauma Responses

What is a trauma response?

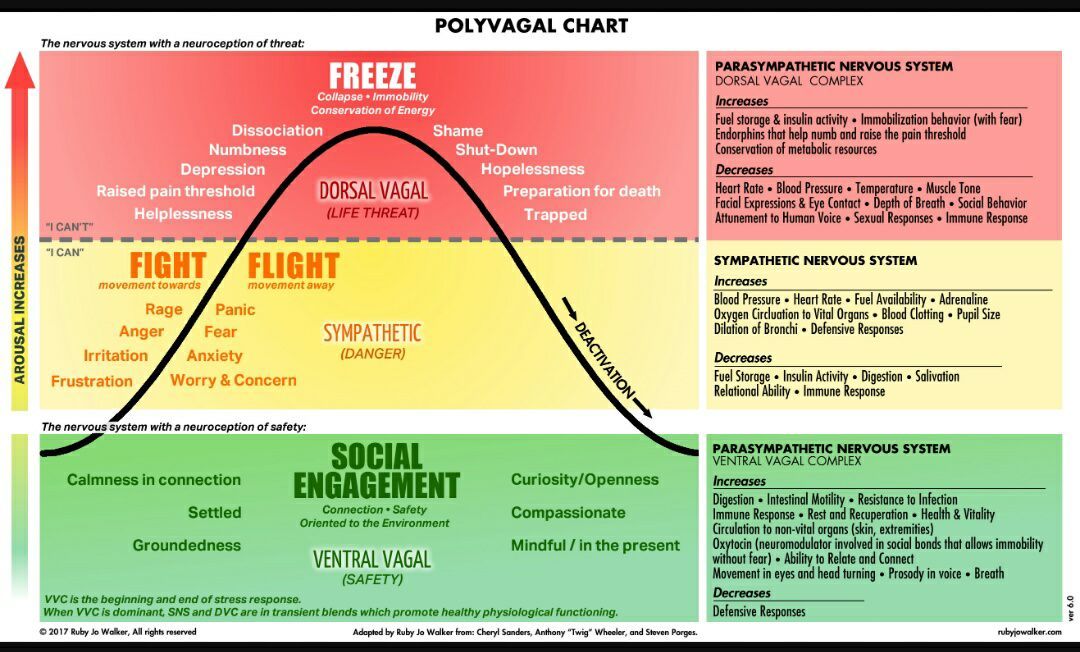

A trauma response is the reflexive use of over-adaptive coping mechanisms in the real or perceived presence of a trauma event, according to trauma therapist Cynthia M.A. Siadat, LCSW. The four trauma responses most commonly recognized are fight, flight, freeze, fawn, sometimes called the 4 Fs of trauma.

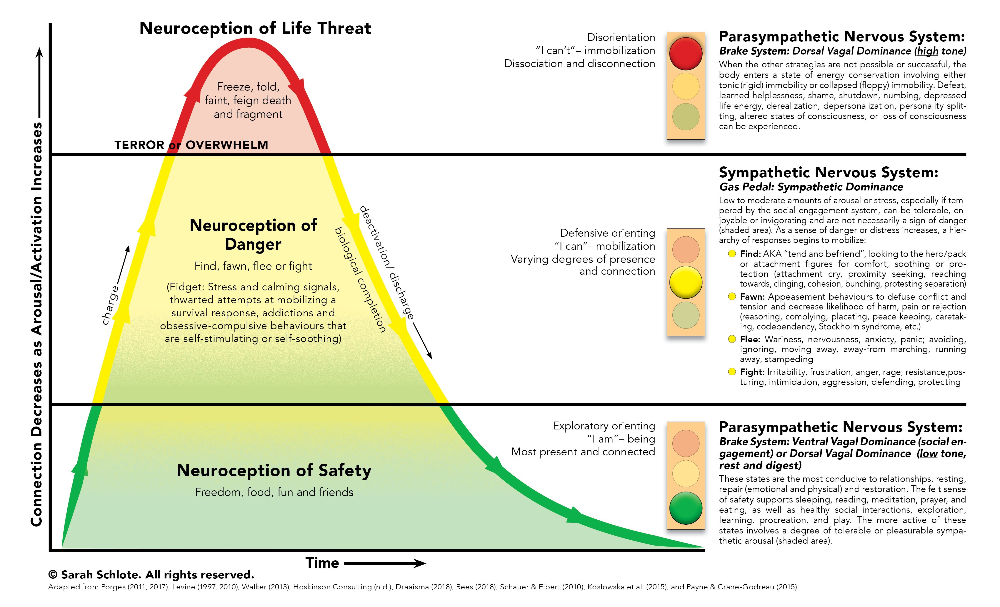

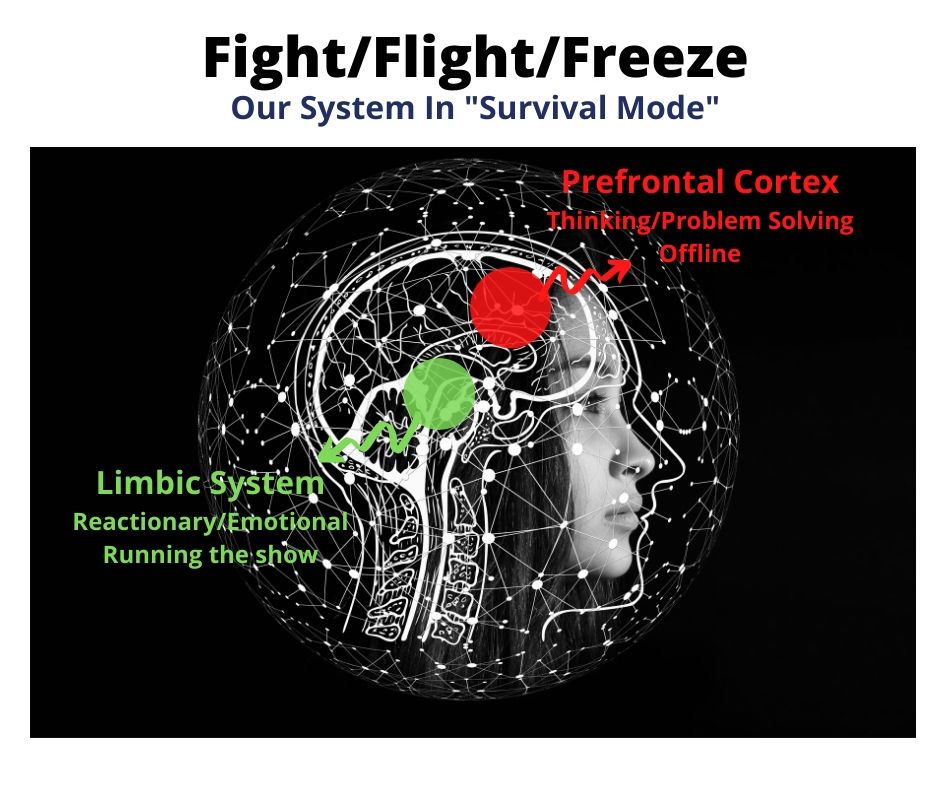

"When we experience something traumatic or have been exposed to prolonged stress, it causes part of our brain, the amygdala, to go into hyperdrive where we see and feel threats in nonthreatening situations," licensed therapist Chioma Moronu, LCSW, tells mbg. "This causes us to act in ways that we don't understand and can leave us feeling like we no longer have control over ourselves. The [trauma] response is often based on what your brain thinks will help you survive the current situation."

In a study about the neurobiological effects of psychological trauma1, researchers note our bodies are designed to respond to perceived threats through a constellation of near-instantaneous, reflexive survival behaviors. Via a short-term strategy, chemicals are sent into our bloodstream to activate the sympathetic nervous system's defenses. But when stress responses are constantly triggered, there's not enough time to metabolize the chemicals, and our nervous system overloads and dysregulates—putting us squarely in the survival zone. The temporary defenses become sustained as our body shifts into a state of sympathetic nervous system dominance.

Via a short-term strategy, chemicals are sent into our bloodstream to activate the sympathetic nervous system's defenses. But when stress responses are constantly triggered, there's not enough time to metabolize the chemicals, and our nervous system overloads and dysregulates—putting us squarely in the survival zone. The temporary defenses become sustained as our body shifts into a state of sympathetic nervous system dominance.

Notably, these trauma responses aren't exclusive to people who've experienced those big "T" events (such as war, death, or disaster) commonly linked to meaningful trauma. The reality is that trauma exists across a continuum of stress. Little "T" events, sometimes called micro-traumas, can also be profoundly affecting since trauma is a subjective and individualized experience. For example, some traumatic stressors can include events such as a bad breakup, a betrayal of trust, a chronically abusive workplace, or undergoing something subtly frightening over a period of time. They may not feel particularly injurious, but the complex effects of trauma can still affect you significantly when it's not emotionally processed and integrated—somatically, spiritually, and mentally. If it's not resolved, trauma can essentially convert into stuck, frozen energy that your body will uniquely respond to physiologically in the form of a trauma response.

They may not feel particularly injurious, but the complex effects of trauma can still affect you significantly when it's not emotionally processed and integrated—somatically, spiritually, and mentally. If it's not resolved, trauma can essentially convert into stuck, frozen energy that your body will uniquely respond to physiologically in the form of a trauma response.

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

Fight, flight, freeze, fawn: the four types of trauma response.

Healthy stress responses aren't inherently bad as it helps you assert yourself in short-term situations. However, in the face of trauma, it can be taken to the extreme and become something wearing and unhealthy for your body.

The fight response.

When healthy, the fight response can allow for assertion and solid boundaries. When unhealthy—i.e., when used as a trauma response—it's an active self-preservation function where you move reactively toward conflict with anger and aggression. It's a fear state where you confront the threat to stand up and assert yourself.

It's a fear state where you confront the threat to stand up and assert yourself.

"People who respond with fight are utilizing conflict to navigate the situation," Moronu explains. "A fight trauma response is when we believe that if we are able to maintain power over the threat, we will gain control. This can look like physical fights, yelling, physical aggression, throwing things, and property destruction. It can also look like balling your hands into fists, feeling a knot in your stomach, crying, being argumentative, or experiencing a tight jaw."

If you notice yourself exhibiting the above behaviors, take a moment to slow down and think about how you are positioning yourself at the moment. It may feel good to access your physicality to gain mobility in the situation and have your insides reflect your outsides, but it comes at the cost of connection and others feeling secure around you.

"In order to release this, you can use deep breathing, warm baths, routines, mindfulness, and being [gentle] with yourself," Moronu suggests. The fight response preps you to be physical, so you can also lean into exercise to allow the body to calm and achieve homeostasis. By practicing mindfulness and a burst of constructive activity like yoga or stretching, it activates your parasympathetic system. It releases anxiety and helps you sink back into the immediate environment so you feel safe to reconnect.

The fight response preps you to be physical, so you can also lean into exercise to allow the body to calm and achieve homeostasis. By practicing mindfulness and a burst of constructive activity like yoga or stretching, it activates your parasympathetic system. It releases anxiety and helps you sink back into the immediate environment so you feel safe to reconnect.

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

The flight response.

When faced with a dangerous situation, the flight response corresponds with avoidant behavior. When you're healthy, you're able to be discerning in stressful situations and disengage within limits. However, as a trauma response, you take it a step further by isolating yourself entirely.

"The flight response is when we believe that if we are able to escape the threat and avoid conflict, then we will not be harmed. This can look like running away and avoiding interactions with others," notes Moronu. To avoid uncomfortable feelings, you may escape the situation by staying busy or fleeing for the exit whenever things get tough.

To avoid uncomfortable feelings, you may escape the situation by staying busy or fleeing for the exit whenever things get tough.

To drop back into yourself, do things that create an immediate, visceral reaction with your body. Pay attention to any tense muscles and relax them to relax the mind. Siadat recommends bodywork and intentional movements to halt the stress response so you can think about how you want to respond instead of your initial impulse to react.

Moronu advises coping techniques that are tactile and grounding, like drinking a warm beverage or eating crunchy food. Moronu also encourages the importance of building connections with those around you, which increases feel-good, happy chemicals like endorphins and serotonin.

The freeze response.

When healthy, the freeze response can help you slow down and appraise the situation carefully to determine the next steps. When unhealthy, the freeze response relates to dissociation and immobilizing behaviors. When this defense is enacted, it often results in literally "freezing"—feeling frozen and unable to move or finding yourself spacing out as if you're in a haze or detached from reality. You don't feel like you're really there, and you're mentally checked out as you leave out what's happening in your surroundings and what you're feeling in an attempt to find emotional safety.

When this defense is enacted, it often results in literally "freezing"—feeling frozen and unable to move or finding yourself spacing out as if you're in a haze or detached from reality. You don't feel like you're really there, and you're mentally checked out as you leave out what's happening in your surroundings and what you're feeling in an attempt to find emotional safety.

"A freeze trauma response is when parts of your sympathetic nervous system have reached a point of overwhelm causing a neurological shutdown," Siadat says. "I liken this response to our animal friends who play dead in the presence of a predator. When we freeze, it might look like being at a loss for words, retreating into your mind, having a hard time breaking out and being present, sleeping, dissociating/spacing out, and going emotionally or physically numb."

It's the equivalent of temporary paralysis and disconnecting with your body to prevent further stress.

To counteract that loss of connection with yourself, Siadat recommends doing grounding exercises if you catch yourself starting to dissociate. "My favorite one is what my own therapist taught me. I call it 'See Red.' Scan around your immediate surroundings for a red object. For me at the moment, I see my husband's red hoodie. Then what I'll do is focus my eyes on it, say red hoodie, and take one deep, slow breath. Then I'll scan the room for a second red item and do the same. I repeat this five times. Doing this can help bring us back to our present moment and the environment we are currently in versus the environment we create when we're in a trauma response that's taking us out of the present moment."

"My favorite one is what my own therapist taught me. I call it 'See Red.' Scan around your immediate surroundings for a red object. For me at the moment, I see my husband's red hoodie. Then what I'll do is focus my eyes on it, say red hoodie, and take one deep, slow breath. Then I'll scan the room for a second red item and do the same. I repeat this five times. Doing this can help bring us back to our present moment and the environment we are currently in versus the environment we create when we're in a trauma response that's taking us out of the present moment."

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

The fawn response.

At its core, fawning is about people-pleasing and engaging in pacifying behaviors. It's characterized by prioritizing people above all else by doing whatever they want to diffuse conflict and receive their approval. It seems good to be well liked and defer to others to secure safety, but not when it's at the cost of losing yourself. It can reach a point where you abandon yourself and your needs by merging so thoroughly with others. Most likely, you don't feel seen by others and may feel eclipsed by the people in your life.

It can reach a point where you abandon yourself and your needs by merging so thoroughly with others. Most likely, you don't feel seen by others and may feel eclipsed by the people in your life.

"The fawn response is people-pleasing to the degree of forgetting yourself entirely; thoughts, emotions, body sensations," Siadat says. "I know I'm encountering a fawn response when someone tells me what I'd like to hear and when I ask how they're feeling, they respond 'I'm OK, how are you?' or 'I'm all right, so-and-so did this to me, and I felt pretty bad.' I'll receive a brief response about how they're doing and then a lengthier response about how someone else in their life is doing."

If you're noticing that you're fawning often, be extra compassionate with yourself as you begin to separate what feelings belong to you and what belongs to other people. Observe yourself when you're around others to add in buffering time to help prevent resorting to fawning. The first step is awareness and learning how to start putting up boundaries to take up space.

"Through my own work, I know that bringing it into my awareness when I'm doing it is challenging, and when called out, it can feel embarrassing," Siadat says. "Know that your body and mind did what it needed to protect you but you can reestablish safety within yourself. You are capable and worth it."

Can you have more than one trauma response?

Trauma responses don't always neatly fit into a category, so you may not over-rely on the same defenses whenever you encounter fear. It's more likely to primarily identify with one or two but still toggle between the 4 Fs depending on the situation-specific context that you are in. For people who suffered severe trauma, responses pair up creating hybrids like fight/fawn and flight/freeze.

"Another factor contributing to our responses are the real or perceived consequences of our actions," Siadat notes. "One trigger for trauma may elicit more of a fleeing instance, where another that's present may want you to fight—an example of this is an age-old argument with a loved one where you both want to hang up the phone and yell. Or if you're fawning, you want to tell them they are right and you are wrong just to keep the peace."

Or if you're fawning, you want to tell them they are right and you are wrong just to keep the peace."

Advertisement

This ad is displayed using third party content and we do not control its accessibility features.

The bottom line.

If you identify with one of the 4 F trauma responses, know you aren't alone. Siadat points to social support and journaling as self-soothing tools to learn about your behaviors, figure out how to better deal with tough situations, and move toward recovery.

"Noticing and then speaking about your trauma response to someone who cares for you doesn't leave you judged and won't give unsolicited advice can help a great deal. Our first step toward healthier living is by identifying our current behaviors and then knowing in due time, we can make adjustments as we need to," she says.

In tandem, embodied healing is integral to processing and feeling safe in your body. Managing your mental and physical health helps chart a new path forward to cultivate responses that attune to you healthily. Moronu strongly recommends leaning on yoga to calm down the survival brain and looking for a trauma-informed therapist.

Moronu strongly recommends leaning on yoga to calm down the survival brain and looking for a trauma-informed therapist.

"Remember to show yourself grace, kindness, and compassion," Moronu affirms. "You have been doing what is needed to survive. It will take time to unlearn some of these behaviors, and that's OK."

Tutorial

Tutorial 1.3.3. Stages of combat flight and their characteristics

Air formations, units, subunits perform combat missions in combat flights. A combat flight is a flight to perform a combat mission.

A combat flight includes the following main stages: takeoff and formation of battle order; flight to the area of the combat mission; actions in the area of the combat mission; flight from the combat mission area to the landing airfield(s); disbandment of battle formations and landing. nine0007 Rise and formation of battle order. The take-off of aviation units, subunits and crews is carried out at the estimated time or on a signal from the command post. The takeoff order is set by the commander.

The takeoff order is set by the commander.

After takeoff, the formation of the combat order of the aviation unit (units) is carried out. The formation of the combat formation of a unit (subunit) is carried out in the area of the airfield or on the flight route in the manner prescribed by the commander. At the same time, reliability and simplicity of construction, the least expenditure of time, maximum advance along the route to the area of the combat mission, secrecy, freedom of maneuver of the unit (subunit, crews) and the safety of aircraft from collision with each other must be ensured. nine0007 The flight to the combat mission area is carried out over one's own territory and the territory of the enemy, or only over one's own territory. The actions of the unit (subunit, crews) at this stage of the combat flight should be aimed at the exact exit to the area of the combat mission without loss.

Flight over one's own territory is carried out, as a rule, at altitudes that make it difficult or preclude early radar detection by the enemy of the combat order, while observing the measures of radio and radio technical masking. In all cases, the flight over its territory and the flight of the front line is carried out with the identification equipment turned on. nine0007 Flight over the territory of the enemy is carried out with overcoming his air defense. It consists in carrying out supporting actions and performing tactics aimed at reducing the effectiveness of enemy air defense systems.

In all cases, the flight over its territory and the flight of the front line is carried out with the identification equipment turned on. nine0007 Flight over the territory of the enemy is carried out with overcoming his air defense. It consists in carrying out supporting actions and performing tactics aimed at reducing the effectiveness of enemy air defense systems.

Actions in the combat mission area should be aimed at its unconditional fulfillment and be based on a plan (variant) developed in advance and taking into account the actual situation.

Access to the objects of action must be carried out exactly at the place and time. Depending on the types of aircraft, their equipment, the nature of the objects and the conditions of visibility, access to the objects of action can be carried out:

- using autonomous sighting and navigation systems;

- with the help of radio equipment;

- according to the course and time from the characteristic landmark;

- guidance and target designation from ground, air (ship) control posts and guidance aircraft (helicopters).

Access to action objects can be performed from one direction, in a given sector, or from different directions.

An attack is a decisive stage of an air strike or offensive air combat, which is a rapprochement with a target in combination with aiming and using aviation weapons against it. It begins from the moment the initial (calculated) position is taken for the use of aviation weapons and ends with a lapel (leaving) from it after the targeted use of aviation weapons. nine0007 The attack of the target can be carried out simultaneously or sequentially by crews (subunits, tactical groups). If it is necessary to perform repeated attacks, maneuvering is carried out to occupy the starting position.

The flight from the combat mission area to the landing airfield (airfields) is carried out along the shortest distance in the lanes where enemy air defense is suppressed. The passage of the front line is carried out in the corridors and at heights agreed with the air defense forces of the front. nine0007 The dissolution of battle formations and landing. The approach to the landing airfield and the disbandment of combat formations should be carried out, as a rule, at heights that exclude radar observation by the enemy. The order of dissolution and landing approach is established by the commander.

nine0007 The dissolution of battle formations and landing. The approach to the landing airfield and the disbandment of combat formations should be carried out, as a rule, at heights that exclude radar observation by the enemy. The order of dissolution and landing approach is established by the commander.

After landing, the commander must take all measures to disperse the aircraft and prepare them for a second flight as soon as possible.

Test flights and operator evaluations | Air transport review

Aviation Business Portal

Boeing experimental aircraft crashed during test flight

News

Ansat" with different layouts

Mi-171A2 - first reviews

Analytics

05/14/2019 UTair Helicopter Services shared their experience in operating the latest helicopter

"Increasing the payload by 400 kg will allow us to offer 17–18 seats for sale"

Interview

24. 04. shared his opinion with the ATO about the new Aircraft Industries product

04. shared his opinion with the ATO about the new Aircraft Industries product

Dassault FalconEye: to a new level of situational awareness

Analytics

News

04/20/2017Inozhnaya aircraft will help the airline to roll out routes before receiving MS-21

"Saratov Airlines" completed the formation of the An-148

9000 9000-2017-Russian carrier will increase the intensity of the four-aircraft in this type ofNew generation in the air

Analytics

04/19/2017 Flight report on the newest Bombardier CS300

Yakutia: road to recovery

News

03/24/2017, 2017 Athletic airline increased passenger transportation and fell in love with conjugated contracts

Yakut "Elki"

Analytics

9000.2017 Vespen of new L-410 "Polar Airlines" Poems " technological bar in business aviationAnalytics

01/06/2017What will be the new business jet

Record August

Analystation

10/28/2016V The last summer month of E195 "Saratov Airlines" spent more than 10 hours a day

Piston regional aircraft Tecnam P2012 made the first flight

07/28/2016VS is offered for replacement CESSNA 402C and 208B

Pages

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- >

- Last

Google thinks you'll be interested

Think you missed the right material?

105th Anniversary of the Russian Air Force

On August 12, 2017, the Russian Air Force (VVS; successor to the Air Force in 2015) celebrated its 105th anniversary with pomp.