Elizabeth kubler ross stages of grieving

5 stages of grief: What they are and how to get through them

CNN —

When someone you love dies, the world as you’ve known it is totally upended.

One way people cope, added psychologist Sherry Cormier, is by trying to find some sort of certainty. This need for structure is probably one factor behind the popularity that latched onto the “five stages of grief” over 50 years ago and hasn’t yet let up, said David Kessler, who founded grief.com, a resource aiming to help people deal with uncharted territory related to grief. Kessler coauthored “On Grief and Grieving” with the late Dr.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

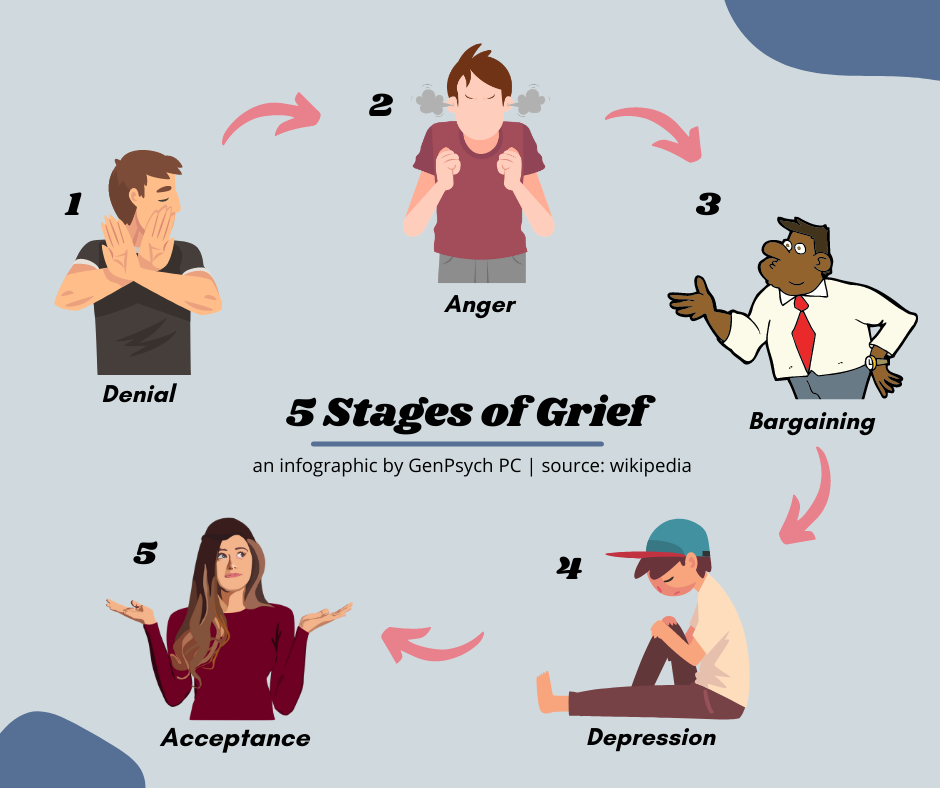

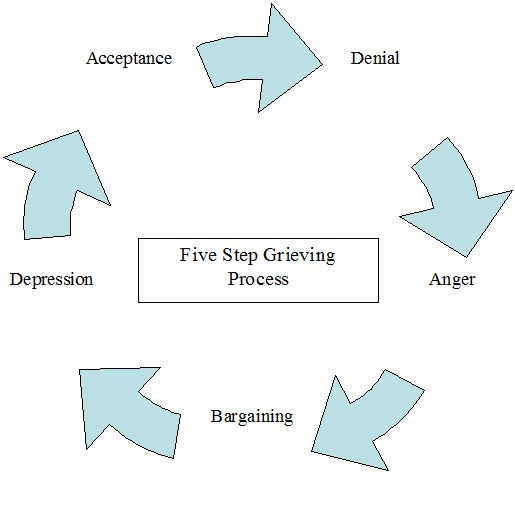

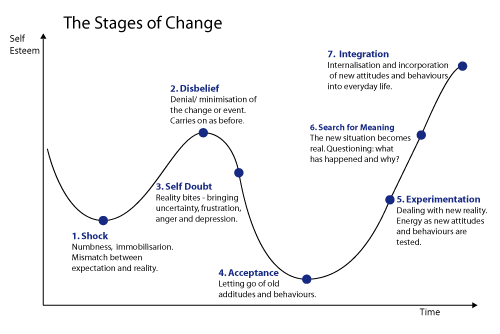

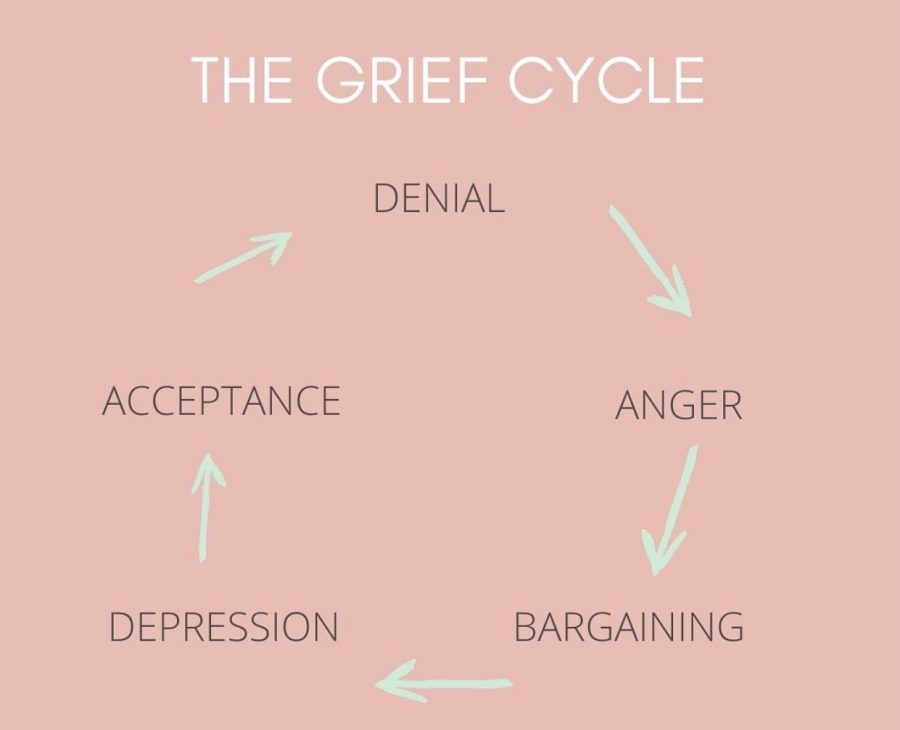

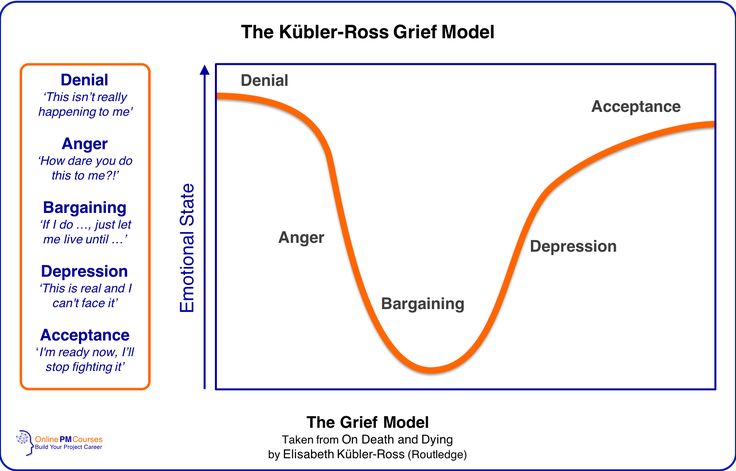

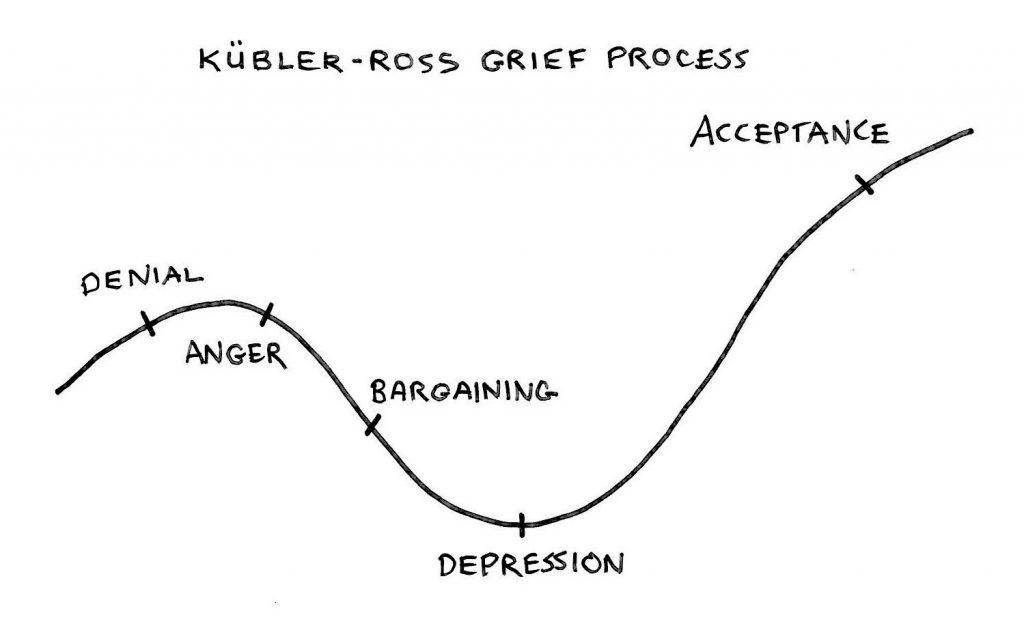

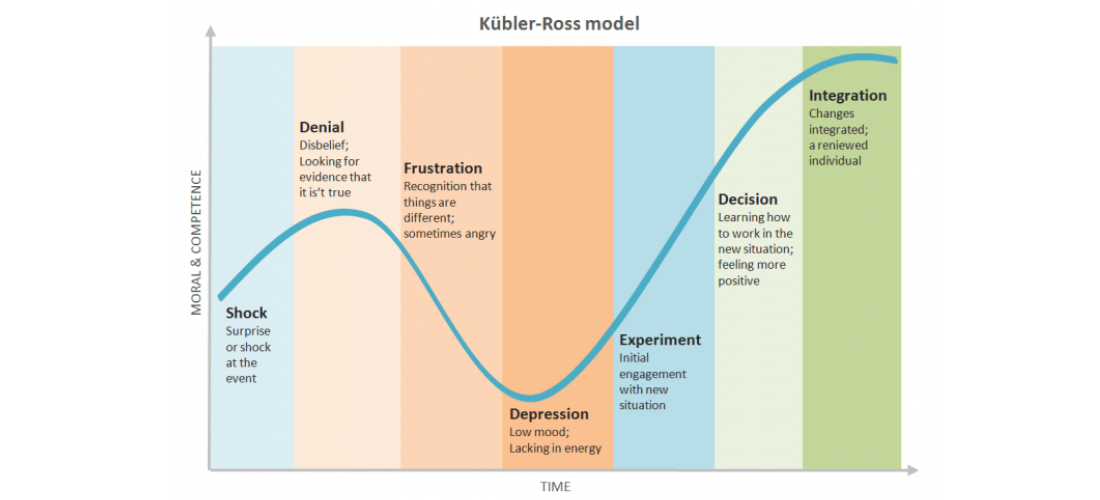

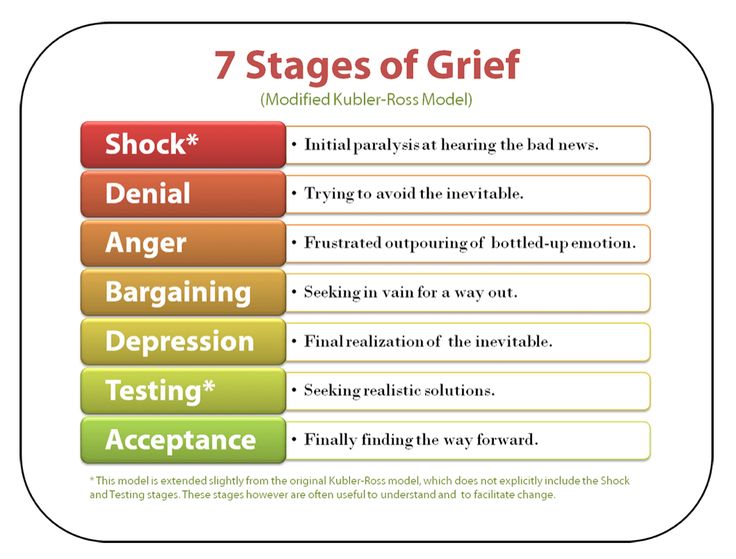

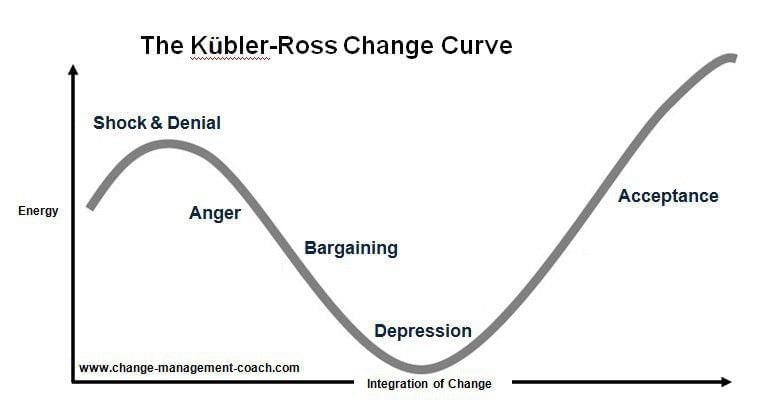

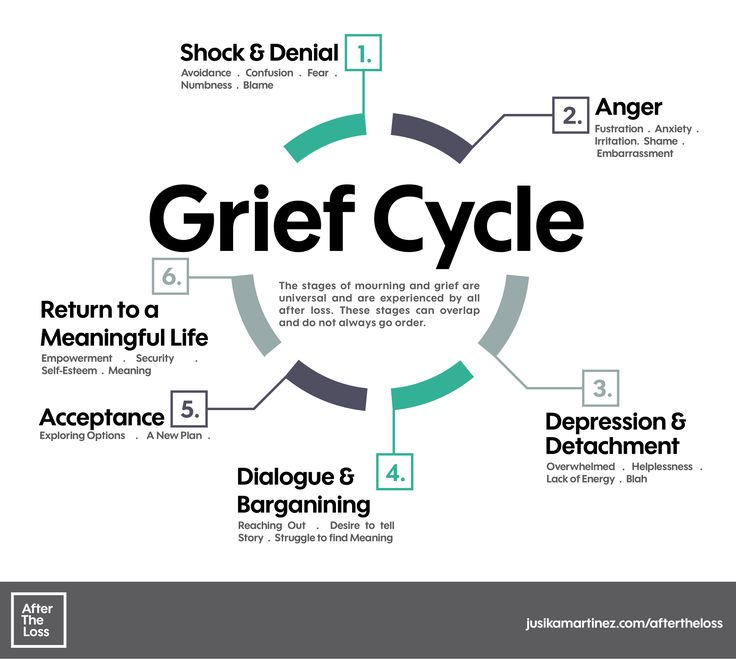

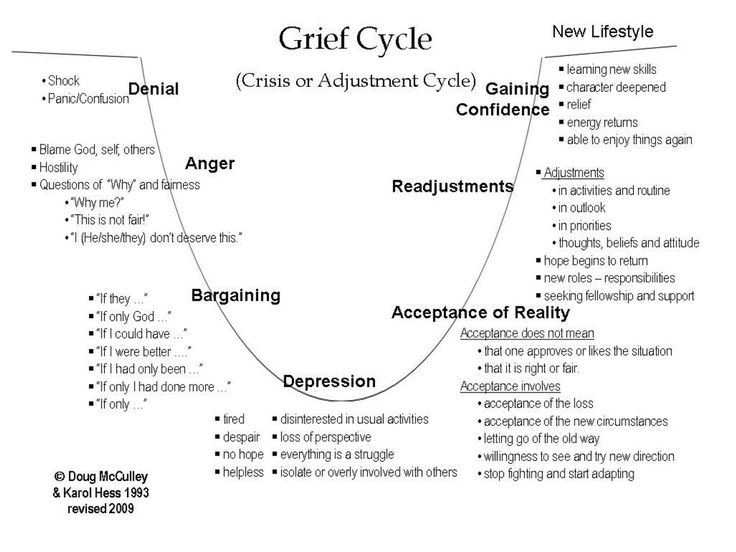

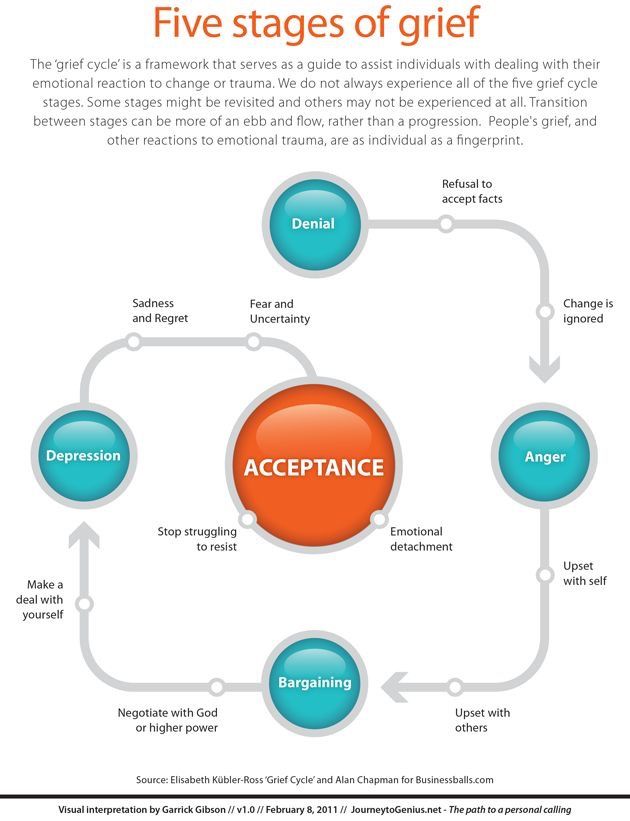

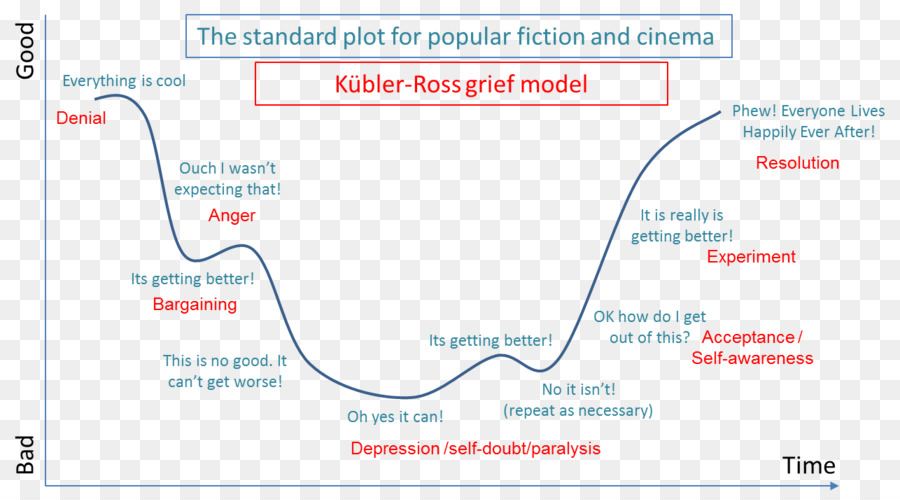

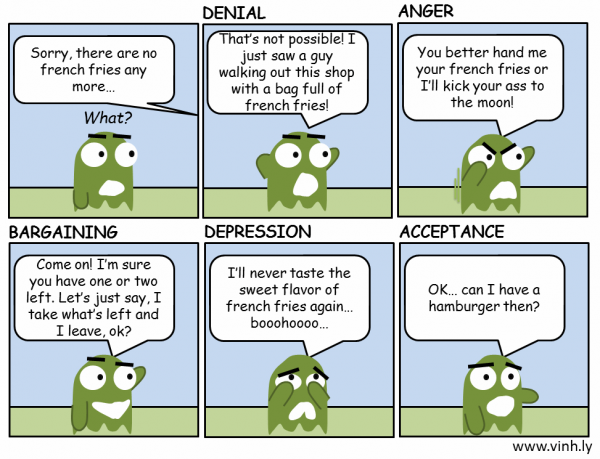

A Swiss American psychiatrist and pioneer of studies on dying people, Kübler-Ross wrote “On Death and Dying,” the 1969 book in which she proposed the patient-focused, death-adjustment pattern, the “Five Stages of Grief.” Those stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

“In the actual book, she talked about more than five stages,” Kessler said. “Think about the context of 1969 – doctors and hospital personnel were not talking about the end-of-life process. … Elisabeth really hoped ‘On Death and Dying’ would start the conversation.”

Since then, there has been extensive media coverage of the five stages; use in television shows including “Grey’s Anatomy” and “House”; clinician support; and criticism. Those five stages are what people clung to, Kessler said.

Those five stages are what people clung to, Kessler said.

Grief and psychology experts and academics have criticized the framework for not being thoroughly supported by research, suggesting that the bereaved move through grief sequentially or implying one correct way to grieve. But these suggestions weren’t Kübler-Ross’ intentions, and she stated these caveats on the first page of the book, Kessler said.

While there’s debate among experts about the stages of grief, “people who are in the pain of grief are just saying, ‘Help me,’” Kessler said. Here’s what the five stages of grief are, and how you can consider and process them in whichever order you experience them.

In denial there is grace, in that we can’t fully register the total pain, shock and disbelief over our loss in one moment or day, so the pain is spread over time, Kessler said.

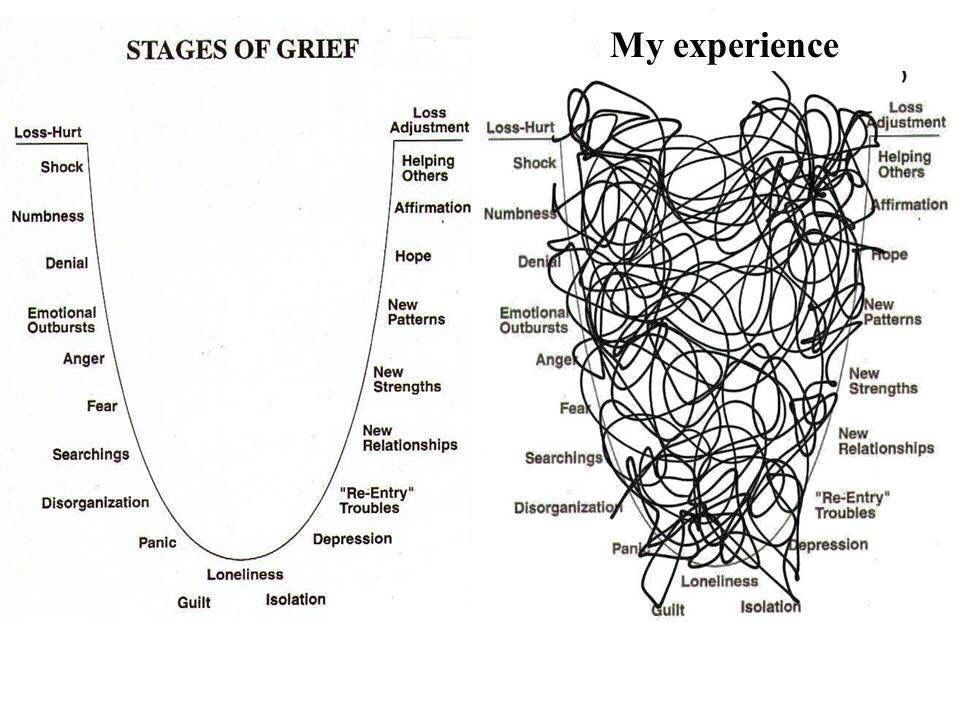

Grief isn't linear, as you might experience each stage within one moment, out of order or cyclically.

Getty ImagesWhile denial in a literal and dysfunctional sense would be trying to convince yourself your loved one isn’t dead, an inability to comprehend the loss for a while is healthy – not something you need to quickly snap out of, he added.

If you’re struggling with overwhelming denial, you can try to stop fighting the reality you’ve been presented with, said Cormier, who is also a bereavement trauma specialist and consultant.

Anger is another natural reaction to loss, whether it’s anger at the cause of death, the deceased, the god of your religion, yourself or the randomness of the universe, Kessler said.

“Anger is pain’s bodyguard. It’s how we express pain,” he said. “That stage gives people permission to be angry in healthy ways, and to know it’s not bad.”

Courtesy of Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid

The art of processing our collective grief

Anger “can be an anchor, giving temporary structure to the nothingness of loss. At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything,” according to Kessler’s website. “Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – your anger toward them.”

At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything,” according to Kessler’s website. “Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – your anger toward them.”

Beneath anger can be feelings of hopelessness or powerlessness, Cormier said, sometimes prompting guilt and blame that some people use to maintain an illusion of control or express frustration.

“Our minds would always rather feel guilty than helpless,” Kessler said.

Depending on how your loved one died, one way to overcome guilt- and blame-related anger is by realizing that as horrific as your loss is, it wasn’t personally done to you, Kessler said.

“The reality is the death rate in families is 100%,” he said. “Everyone is going to die eventually, but our minds just can’t fathom that.”

Allow yourself to express anger in healthy ways, Kessler advised, whether it’s “grief yoga,” screaming in your car, using a punching bag, running or other forms of exercise.

Often also stemming from guilt, bargaining after a loss typically involves “if only” statements, focused on regrets about what you did or didn’t do before the person died, Kessler said.

Shutterstock

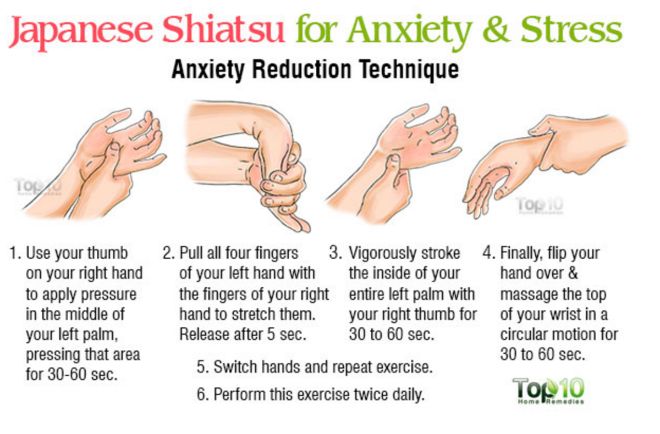

Grief-induced anxiety: Calming the fears that follow loss

“We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss,” Kessler’s site says. “People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. ”

”

Remember that we live in a world where sometimes bad things happen despite our best efforts, Kessler said.

Depression, or an acute sadness, is when the great loss begins more deeply affecting your life. Maybe the sadness feels as if it will last forever, or you’ve withdrawn from life or are wondering if life is worth living alone.

Sadness hits people at different times, Cormier said. She has known people who aren’t distraught in the first year after loss, but by year three are consumed with sadness. Why? Because for a time, some can maintain the illusion that their loved one is away on vacation and may be returning, she said.

Why? Because for a time, some can maintain the illusion that their loved one is away on vacation and may be returning, she said.

Overcoming Depression: Facts and Resources

Often, the eventual, deep sadness “is really an expression of, ‘my loved one is gone and not coming back,’” Cormier said.

But those feelings shouldn’t always be labeled as clinical depression, Kessler said. If you think you’re depressed around a death, see a psychiatrist for an evaluation, he advised.

If you think you’re depressed around a death, see a psychiatrist for an evaluation, he advised.

To cope with sadness, you can also seek support from friends, family or grief support groups, and regularly practice self-care, Cormier suggested.

Acceptance doesn’t mean you’re OK with your loved one being gone. “It just means that I now accept the new reality of my life. I’m a widow, I live alone. I don’t have siblings to call up anymore. I don’t have parents to call up anymore,” said Cormier, who wrote “Sweet Sorrow: Finding Enduring Wholeness After Grief and Loss” after losing her husband and immediate family.

Acceptance isn’t grief’s end, either. You might have many little moments of acceptance over time, Kessler said, such as when you plan and attend the funeral.

“One of the questions I get asked most is, ‘When will this grief be over?’” Kessler added. “Very gently, I’ll ask, ‘How long is the person going to be dead? Because if the person is going to be dead for a long time, you’re going to grieve for a long time. It doesn’t mean you will always grieve with pain. To me, the goal of grief work is to eventually remember the person with more love than pain.”

Courtesy Ruedi Habegger

My friend chose an assisted death in Switzerland. Her dying wish was to tell you why

Her dying wish was to tell you why

Arriving at acceptance means you’re healing, Cormier said. But if you can’t get there, you need to seek professional help. Intense and persistent grief that causes problems and interferes with everyday functioning, in a way that typical grief doesn’t after some time has passed, is known as prolonged grief disorder, according to the American Psychiatric Association. The disorder is the newest disorder to be added to the revised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders released in March.

To be diagnosed with prolonged grief disorder, a loved one’s death had to have occurred at least a year prior for adults, and at least six months ago for children and adolescents, according to the association, which publishes the DSM. One symptom is difficulty with reintegration, such as pursuing interests or interacting with friends.

One symptom is difficulty with reintegration, such as pursuing interests or interacting with friends.

Cormier doesn’t think we ever “get over” grief. Our task is different than moving on – it’s learning to integrate the loss into our lives so that we can move forward with a new reality, she added. “It’s sort of offensive to grievers to say, ‘Oh, you’ve really moved on.’ No, I don’t think grievers move on. We move forward.”

After Kessler’s son died at age 21 nearly five years ago, Kessler wanted something beyond acceptance. He had studied late neurologist, psychiatrist and philosopher Dr. Viktor Frankl’s work on meaning, and wondered how meaning related to grief – which inspired his book “Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief. ”

”

Meaning didn’t eliminate Kessler’s pain, but it did cushion it, he said.

Meaning is in what we later do or realize as the bereaved people, Kessler explained. Maybe you recognize the fragility of life, try to change a law or donate money to research so no one dies the way your loved one did, or make a change in your life.

Sign up for CNN’s Stress, But Less newsletter. Our six-part mindfulness guide will inform and inspire you to reduce stress while learning how to harness it.

Five Stages of Grief by Elisabeth Kubler Ross & David Kessler

A Message from David Kessler

I was privileged to co-author two books with the legendary, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, as well as adapt her well-respected stages of dying for those in grief. As expected, the stages would present themselves differently in grief. In our book, On Grief and Grieving we present the adapted stages in the much needed area of grief. The stages have evolved since their introduction and have been very misunderstood over the past four decades. They were never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages. They are responses to loss that many people have, but there is not a typical response to loss as there is no typical loss.

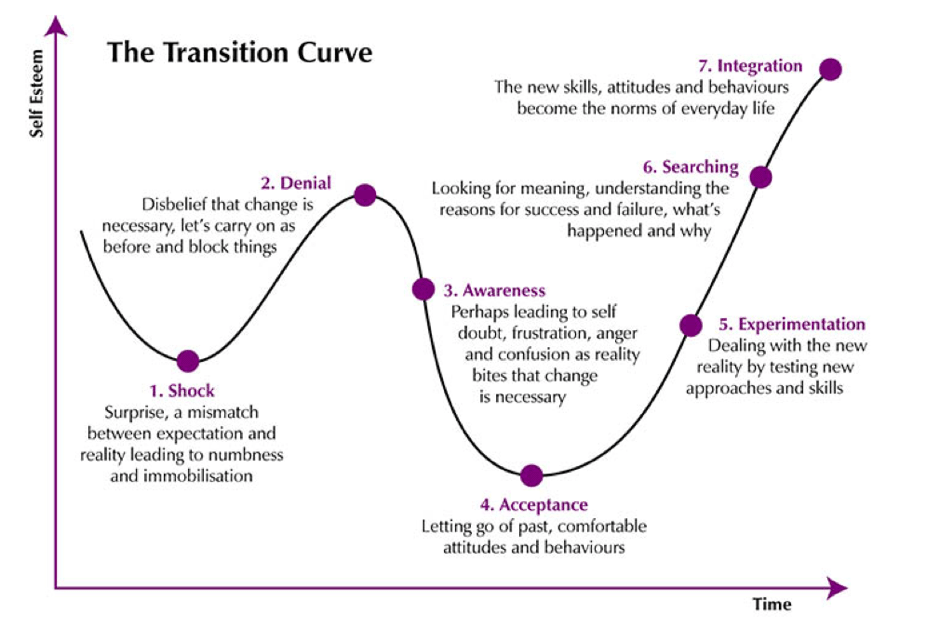

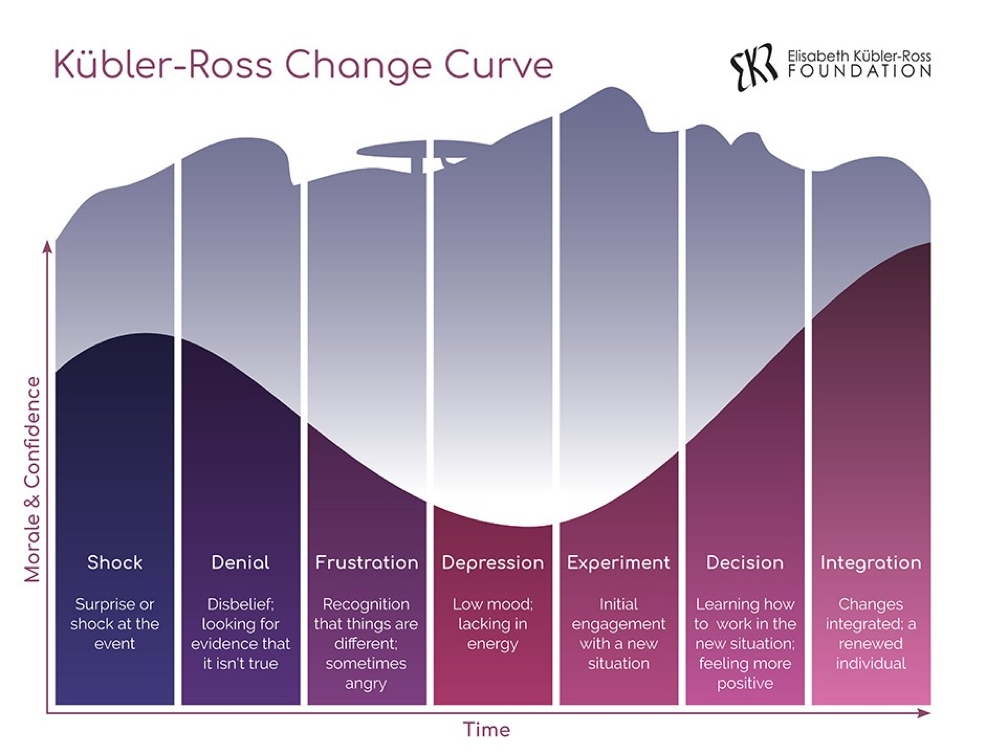

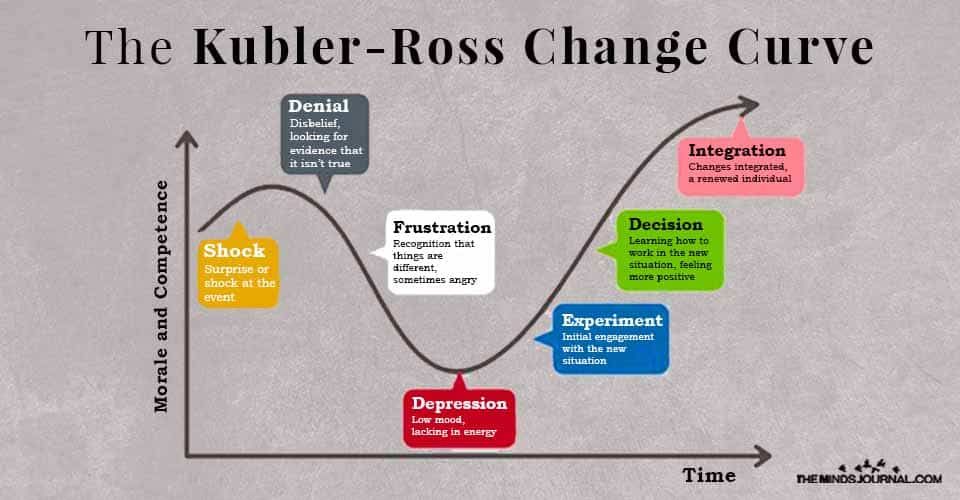

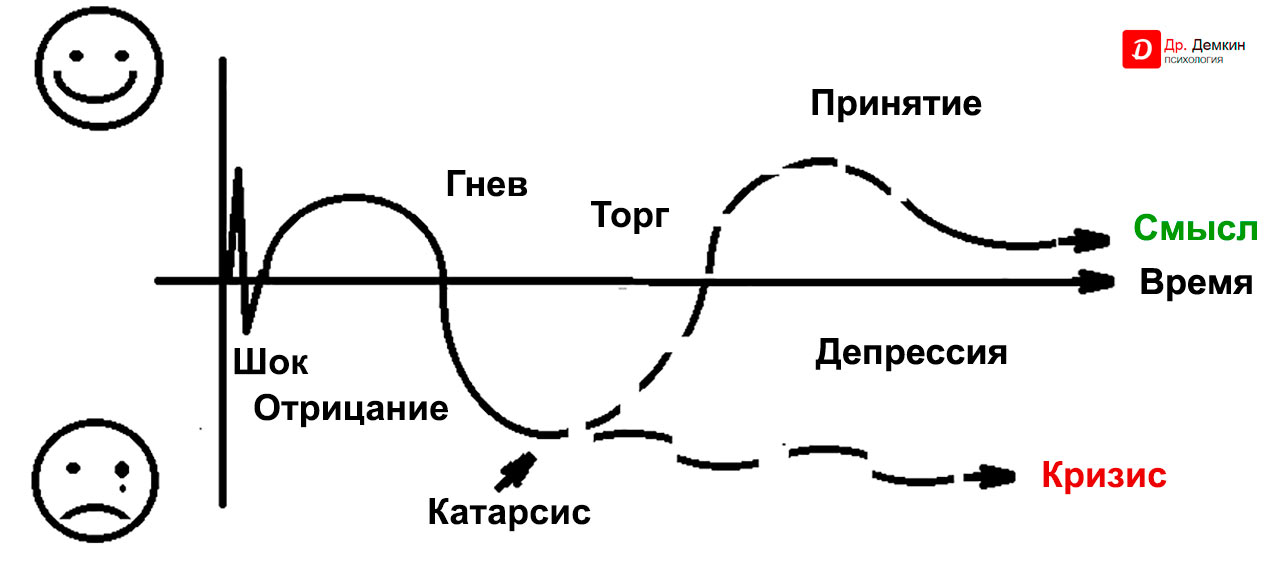

The five stages, denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance are a part of the framework that makes up our learning to live with the one we lost. They are tools to help us frame and identify what we may be feeling. But they are not stops on some linear timeline in grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order. Our hope is that with these stages comes the knowledge of grief ‘s terrain, making us better equipped to cope with life and loss. At times, people in grief will often report more stages. Just remember your grief is an unique as you are.

But they are not stops on some linear timeline in grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order. Our hope is that with these stages comes the knowledge of grief ‘s terrain, making us better equipped to cope with life and loss. At times, people in grief will often report more stages. Just remember your grief is an unique as you are.

NEW BOOK

Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief

In this groundbreaking new work, David Kessler—an expert on grief and the coauthor with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross of the iconic On Grief and Grieving—journeys beyond the classic five stages to discover a sixth stage: meaning.

In this book, Kessler gives readers a roadmap to remembering those who have died with more love than pain; he shows us how to move forward in a way that honors our loved ones. Kessler’s insight is both professional and intensely personal. His journey with grief began when, as a child, he witnessed a mass shooting at the same time his mother was dying. For most of his life, Kessler taught physicians, nurses, counselors, police, and first responders about end of life, trauma, and grief, as well as leading talks and retreats for those experiencing grief. Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

For most of his life, Kessler taught physicians, nurses, counselors, police, and first responders about end of life, trauma, and grief, as well as leading talks and retreats for those experiencing grief. Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

How does the grief expert handle such a tragic loss? He knew he had to find a way through this unexpected, devastating loss, a way that would honor his son. That, ultimately, was the sixth state of grief—meaning. In Finding Meaning, Kessler shares the insights, collective wisdom, and powerful tools that will help those experiencing loss. Read More

DENIAL Denial is the first of the five stages of grief™️. It helps us to survive the loss. In this stage, the world becomes meaningless and overwhelming. Life makes no sense. We are in a state of shock and denial. We go numb. We wonder how we can go on, if we can go on, why we should go on. We try to find a way to simply get through each day. Denial and shock help us to cope and make survival possible. Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It is nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle. As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

Denial and shock help us to cope and make survival possible. Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It is nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle. As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

ANGERAnger is a necessary stage of the healing process. Be willing to feel your anger, even though it may seem endless. The more you truly feel it, the more it will begin to dissipate and the more you will heal. There are many other emotions under the anger and you will get to them in time, but anger is the emotion we are most used to managing. The truth is that anger has no limits. It can extend not only to your friends, the doctors, your family, yourself and your loved one who died, but also to God. You may ask, “Where is God in this? Underneath anger is pain, your pain. It is natural to feel deserted and abandoned, but we live in a society that fears anger. Anger is strength and it can be an anchor, giving temporary structure to the nothingness of loss. At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

It is natural to feel deserted and abandoned, but we live in a society that fears anger. Anger is strength and it can be an anchor, giving temporary structure to the nothingness of loss. At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

BARGAININGBefore a loss, it seems like you will do anything if only your loved one would be spared. “Please God, ” you bargain, “I will never be angry at my wife again if you’ll just let her live. ” After a loss, bargaining may take the form of a temporary truce. “What if I devote the rest of my life to helping others. Then can I wake up and realize this has all been a bad dream?” We become lost in a maze of “If only…” or “What if…” statements. We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion.

” After a loss, bargaining may take the form of a temporary truce. “What if I devote the rest of my life to helping others. Then can I wake up and realize this has all been a bad dream?” We become lost in a maze of “If only…” or “What if…” statements. We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion. We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

DEPRESSIONAfter bargaining, our attention moves squarely into the present. Empty feelings present themselves, and grief enters our lives on a deeper level, deeper than we ever imagined. This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever. It’s important to understand that this depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone? Why go on at all? Depression after a loss is too often seen as unnatural: a state to be fixed, something to snap out of. The first question to ask yourself is whether or not the situation you’re in is actually depressing. The loss of a loved one is a very depressing situation, and depression is a normal and appropriate response. To not experience depression after a loved one dies would be unusual. When a loss fully settles in your soul, the realization that your loved one didn’t get better this time and is not coming back is understandably depressing. If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

ACCEPTANCEAcceptance is often confused with the notion of being “all right” or “OK” with what has happened. This is not the case. Most people don’t ever feel OK or all right about the loss of a loved one. This stage is about accepting the reality that our loved one is physically gone and recognizing that this new reality is the permanent reality. We will never like this reality or make it OK, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. We must try to live now in a world where our loved one is missing. In resisting this new norm, at first many people want to maintain life as it was before a loved one died. In time, through bits and pieces of acceptance, however, we see that we cannot maintain the past intact. It has been forever changed and we must readjust. We must learn to reorganize roles, re-assign them to others or take them on ourselves. Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies. Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies. Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Learn More About The Five Areas of Grief

Watch The FREE Video Now Click Here

Books About the Five Stages by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler

Download Chapter One Click Here

Download Chapter One Click Here

Five stages of grief. The Rise and Fall of Kübler-Ross

- Lucy Burns

- BBC

Image copyright Getty Images

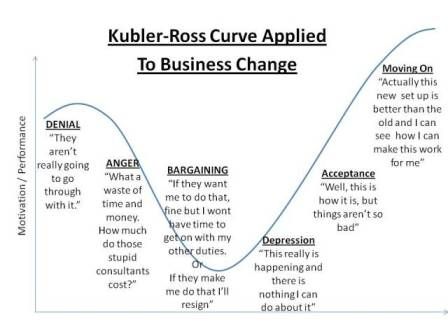

Denial. Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

A recent interview with a psychologist in English on the Internet proves that the perception of the current quarantine is subject to the same rules. But do we all experience the same?

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began working in American hospitals in 1958, she was struck by the lack of methods of psychological care for dying patients.

- A method that can predict your death

"Everything was impersonal, the attention was paid exclusively to the technical side of things," she told the BBC at 1983 year. “Terminally ill patients were left to their own devices, no one talked to them.”

She started a workshop with Colorado State University medical students based on her conversations with cancer patients about what they thought and felt.

Author photo, LIFE/Getty Images

Photo caption,Elisabeth Kübler-Ross talks to a woman with leukemia in Chicago, 1969. Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Despite the misunderstanding and resistance of a number of colleagues, soon there was nowhere for an apple to fall at the Kübler-Ross seminars.

In 1969 she published a book, On Death and Dying, in which she quoted typical statements from her patients and then moved on to discuss how to help doomed people pass from life as free of fear and pain as possible.

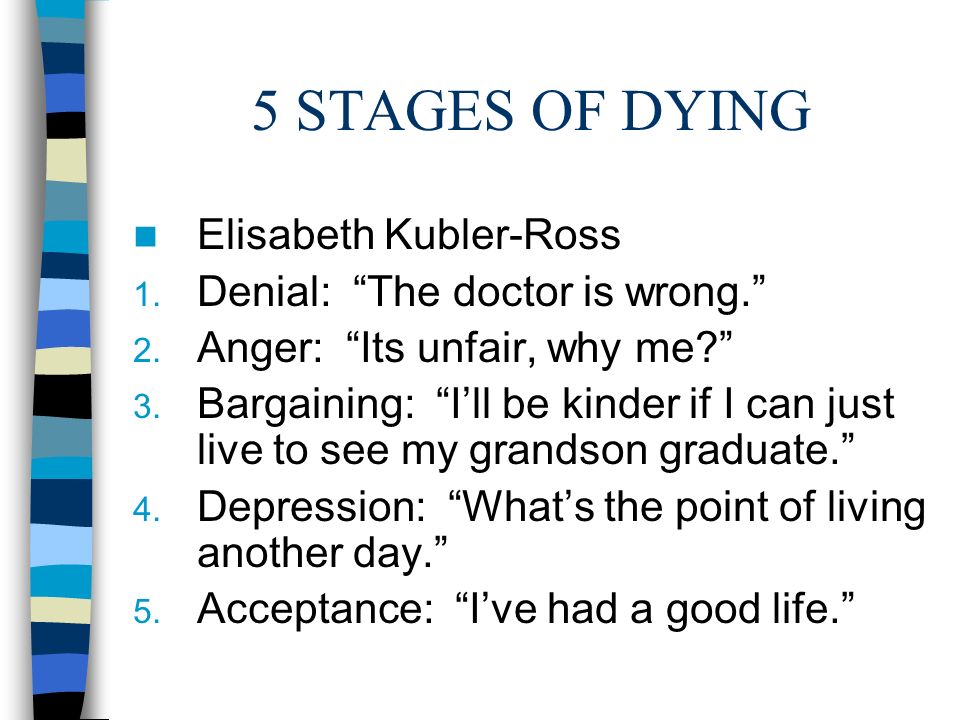

Kübler-Ross described in detail the five emotional states that a person goes through after being diagnosed with a terminal diagnosis:

- Denial: "No, that can't be true"

- Anger: "Why me? Why? It's not fair!!!"

- Bargaining: "There must be a way to save myself, or at least improve my situation! I'll think of something, I'll behave properly and do whatever is necessary!"

- Depression: "There is no way out, everything is indifferent"

- Acceptance: "Well, we must somehow live with this and prepare for the last journey"

difficult situation.

A separate chapter of the book is devoted to each of the stages. In addition to the five main ones, the author identified intermediate states - the first shock, preliminary grief, hope - from 10 to 13 types in total.

Image copyright Getty Images

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross died in 2004. Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

"It was a flexible framework, not a panacea for dealing with grief. If people wanted to use other theories and models, the mother did not object. She wanted to start a discussion of the topic first," he says.

- Last will: how did the photo of a dying American touch the world?

- "You hear everything, Fernando." How was the evening in honor of the terminally ill football player

The book "On Death and Dying" became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon inundated with letters from patients and doctors from all over the world.

"The phone kept ringing, and the postman started visiting us twice a day," recalls Ken Ross.

The notorious five steps took on a life of their own. Following the doctors, patients and their relatives learned about them. They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in cartoons, they gave food for creativity to the mass of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

Literally thousands of scientific papers have been written that have applied the theory of the five steps to a wide variety of people and situations, from athletes suffering career-incompatible injuries to Apple fans' worries about the release of the 5th iPhone.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

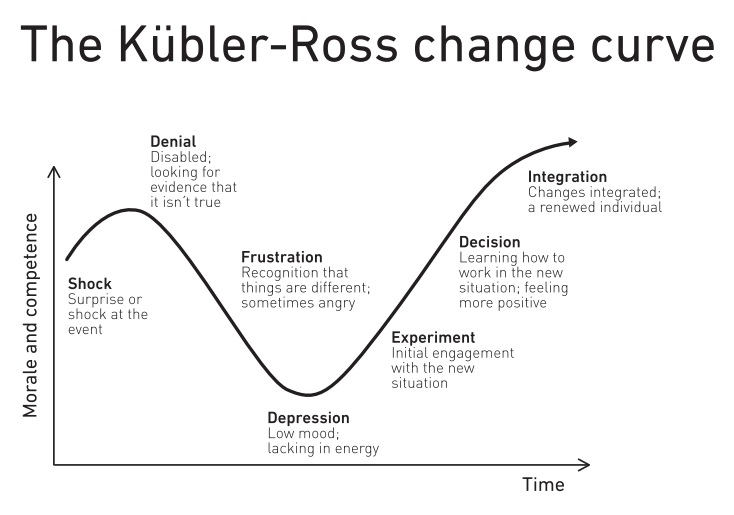

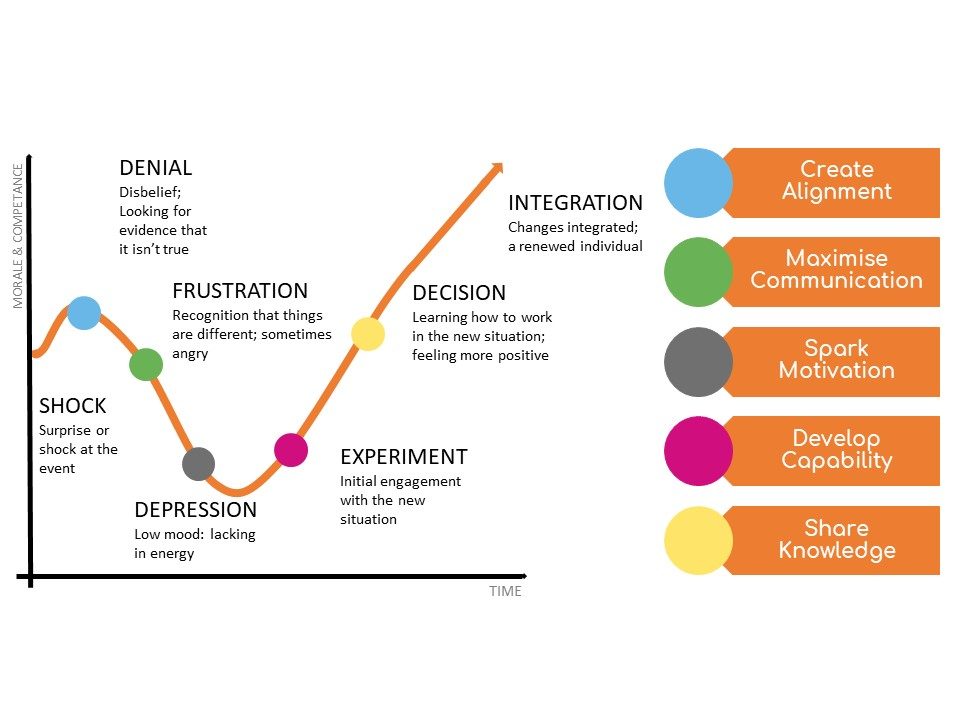

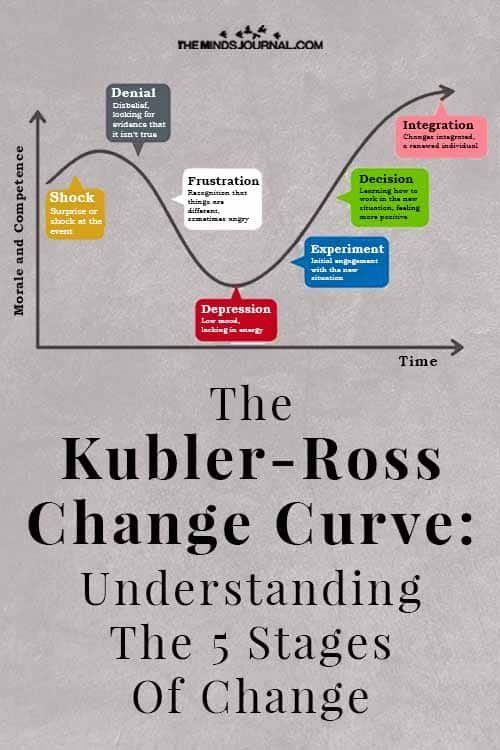

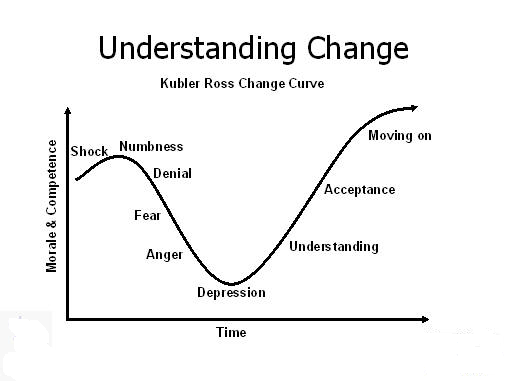

Kübler-Ross's legacy has found its way into corporate governance: Big companies from Boeing to IBM (including the BBC) have used her "change curve" to help employees at times of great business change.

And during the coronavirus pandemic, it applies, says psychologist David Kessler.

Kessler worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve. His interview with the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic garnered a lot of attention online as people everywhere searched for solutions to their emotional problems.

"And here, first comes denial: the virus is not terrible, nothing will happen to me. Then anger: who dares to deprive me of my usual life and force me to stay at home?! Then an attempt to find a compromise: okay, if after two weeks of social distancing it gets better, then why not? Followed by sadness: no one knows when it will end. And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

"As you can see, strength comes with acceptance. It gives you control: I can wash my hands, I can keep a safe distance, I can work from home," he says.

"It's a roadmap," says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Laboratory at Columbia University. "When people are in pain, they want to know: how long will it last? What will happen to me? something to grab on to. And the five-step model gives them that opportunity."

"This scheme is seductive," notes Charles Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Being. "It offers an easy solution: sort everyone, and it takes no more than the fingers of one hand to label each one." .

George Bonanno sees this as a possible harm.

"People who don't fit exactly into these stages - and I've seen the majority of them - may decide they're grieving the wrong way, so to speak," he explains.

According to him, over the years he has seen many cases when people themselves inspired that they must certainly experience this and that, or they were convinced of this by friends and relatives, but they did not feel it and decided, that they need a doctor.

Experimental evidence of the existence of the five stages of grief is not enough. The longest and most extensive bereavement interview was conducted in 2007.

According to him, the most common state at any time is acceptance, only a few go through the stage of denial, and the second most common emotion is longing.

However, according to David Kessler, while scientists debate the nuances and terms, people who experience grief continue to find meaning in the Kübler-Ross scheme.

"I meet people who tell me, 'I don't know what's wrong with me. Now I'm angry, and a minute later I'm sad. I must be crazy.” And I say, “It has names. These are called the stages of grief. ” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

Image copyright, Getty Images

"People need catchy statements. If Kübler-Ross hadn't called it stages and stated that there are exactly five of them, then she probably would have been closer to the truth. But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

He believes that talking about the five stages distracts from the main scientific legacy of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

"She wanted to take on the topic of death and dying in the broadest sense: how to help terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnosis, how to help those who care for them, support these patients and cope with their own emotions, how to help everyone live a full life, realizing that we are not eternal,” says Charles Corr.

"The terminally ill can teach us everything: not only how to die, but also how to live," said Elisabeth Kübler-Ross at 1983 year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, she traveled the world, giving lectures and giving workshops to thousands of people. She was a passionate supporter of the hospice idea pioneered by British nurse Cecily Saunders.

Kübler-Ross has established hospices in many countries, the first in the Netherlands in 1999. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Professor Kübler-Ross' scientific reputation was shaken after she became fascinated with theories about the afterlife and began to experiment with mediums.

One of them, a certain Jay Barham, practiced non-standard religious-erotic therapy, in particular, he persuaded women to have sex, assuring that he was possessed by a person close to them from the afterlife. In 1979, because of this, a loud scandal arose.

In the late 1980s, she tried to set up a hospice for children with AIDS in rural Virginia, but faced strong local opposition to the idea.

In 1995, her house caught fire under suspicious circumstances. The next day Kübler-Ross had her first stroke.

She spent the last nine years of her life with her son in Arizona, moving around in a wheelchair.

In her last interview with the famous TV presenter Oprah Winfrey, she said that at the thought of her own death she feels only anger.

"The public wanted the famed expert on death and dying to be some kind of angelic personality and quickly get to the stage of acceptance," says Ken Ross. "But we all deal with grief and loss as best we can."

The theory of the five stages of grief is not widely taught in medical schools these days. It is more popular at corporate trainings under the name "Curve of Change".

Since then, there have been many theories about how to deal with your grief.

David Kessler, with the consent of Kübler-Ross's family, added a sixth stage to the five: the understanding that everything that is done makes sense.

"Understanding can come in a million different ways. Let's say I've become a better person after losing a loved one. Maybe my loved one passed away in a different way than it should have happened, and I can try to make the world a better place to this has not happened to others," says David Kessler.

Charles Corr recommends the "double process model". It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

George Bonanno talks about four trajectories of grief. Some people have great stamina and do not fall into depression, or it is weakly expressed in them, others remain morally broken for many years, others recover relatively close, but then a second wave of grief rolls over them, and finally, the fourth becomes stronger from the loss.

Over time, one way or another, the vast majority of people get better.

But Professor Bonanno admits that his approach is less clear-cut than the five-stage theory.

"I can say to a person: 'Time heals.' But that doesn't sound so convincing," he says.

Grief is difficult to control and hard to endure. The thought that there is some kind of road map that suggests a way out is comforting, even if it is an illusion.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve, wrote that she did not expect to sort out the tangled human emotions.

Everyone experiences grief in their own way, even if some patterns can sometimes be deduced. Everyone goes their own way.

Stages of accepting the inevitable: description, examples, who invented it

Everyone has heard that there are 5 stages of accepting the inevitable. They are mentioned in a variety of contexts, often giving them a comic meaning. At the same time, not everyone knows that initially this concept was applied to hopeless patients who gradually came to terms with their condition. Today we will talk in detail about what the 5 stages of acceptance are from the point of view of psychology.

Today we will talk in detail about what the 5 stages of acceptance are from the point of view of psychology.

Kübler-Ross Model or 5 Stages of Acceptance

The concept of 5 stages of accepting the inevitable in the scientific community is better known as the "Kubler-Ross model". It is named after the author, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who described it in her book On Death and Dying, published in 1969.

It should be taken into account that official psychology does not consider the Kübler-Ross model to be reliable, despite the fact that it was created by a professional psychologist on the basis of empirical observations. The results of modern studies partially agree with this model, but at the same time, there are discrepancies in some aspects.

In the book, the author defines this model as a description of the emotional experience of a terminally ill person or a person who has lost someone close. In a broader sense, it can be interpreted as a description of the experiences of any person who is faced with irreversible loss or change.

Kübler-Ross 5 stages of accepting the inevitable:

- Negative. Upon learning the tragic news, a person experiences a shock and for some time loses the ability to adequately perceive reality. Gradually, adequate perception returns to him, but he refuses to believe that something so bad could happen to him. As a rule, at this stage, people come up with different explanations for how such a mistake could have occurred. And they believe to the last that everything will clear up, and everything will be fine again, as before.

- Anger. Realizing that there is no mistake, a person is filled with indignation and anger. He no longer denies what is happening, but does not understand why this is happening to him. The feeling of injustice causes him strong irritation, because of which he is angry at everyone: at himself, at his relatives, at doctors and even at God.

- Trade.

At this stage, a person is trying to please God, the Universe or fate, promising that from now on he will behave very well if a miracle happens. Sometimes it's just a matter of changing your lifestyle. For example, a smoker who has been diagnosed with lung cancer decides to quit smoking permanently, hoping that the fatal disease will recede. At this stage, both believers and atheists are trying to make a deal with fate, hoping to receive a reward for good behavior.

At this stage, a person is trying to please God, the Universe or fate, promising that from now on he will behave very well if a miracle happens. Sometimes it's just a matter of changing your lifestyle. For example, a smoker who has been diagnosed with lung cancer decides to quit smoking permanently, hoping that the fatal disease will recede. At this stage, both believers and atheists are trying to make a deal with fate, hoping to receive a reward for good behavior. - Depression. Realizing that being angry and bargaining is useless, a person falls into depression. At the same time, the Kübler-Ross classification describes two forms of depression: reactive and "preparatory grief". The first form is that a person is very emotionally sorry about the past. In this state, he longs for communication with loved ones, wants to explain to them everything that he feels. Preparatory grief is depression before humility. It differs from reactive depression in that the person becomes silent.

- Humility. The essence of this stage is clear from the title. The person is no longer in denial, angry, bargaining, or depressed. By this time, he had already thrown out all his feelings, so he humbles himself and feels calm. Often this calmness is accompanied by emptiness and fatigue from previously overwhelmed emotions.

Keep in mind that the 5 stages of acceptance is a greatly simplified version of the model described in the book. There, the author points out that there are actually more stages and they are not replaced sequentially. For example, reactive depression may come earlier than bargaining. And after bargaining comes preparatory grief, which, after several alternations with reactive depression, nevertheless passes into the stage of humility.

The history of the creation of the model

The author of the theory about the 5 stages of accepting the inevitable is the American psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross. It all started in 1965, when four students at the Chicago Theological Seminary approached her with a request to help them write an unusual term paper. They wanted to understand the experiences of dying people and to know and, if possible, meet their needs.

It all started in 1965, when four students at the Chicago Theological Seminary approached her with a request to help them write an unusual term paper. They wanted to understand the experiences of dying people and to know and, if possible, meet their needs.

Together with students, Kübler-Ross visited hopeless patients and had conversations with them, which were recorded on a tape recorder for subsequent detailed analysis. To many hospital staff, these visits seemed morally dubious. However, over time, they agreed that conversations with a psychologist and theology students could be useful for dying people.

The hospital staff stopped preventing patients from visiting, and literally the following year, about 50 students attended seminars. For this, a special chamber with a Gesell mirror was even equipped. Kübler-Ross communicated with patients, with whom the priest sometimes came. And the seminary students watched the conversation through translucent glass.

In 1967 (that is, 2 years after the start) these classes became the official course for many medical schools and theological seminaries. And in 1969, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross published On Death and Dying , in which she summarized her truly unique observations. In the same book, she described the 5 stages of accepting the inevitable.

At the same time, the book dealt exclusively with the experiences of dying people and their relatives. But later it turned out that the proposed concept is applicable to any experiences associated with irreversible losses and changes in life. It could be a serious career setback, separation from a loved one, physical injury, or any other situation that is difficult for a person to accept.

Who is Elisabeth Kübler-Ross?

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross is a highly controversial person. Her contribution to the development of palliative care cannot be overestimated, but there are dark spots in her biography. However, first things first. Glory came to her in 1969 , when the book mentioned above became a bestseller, and the course she created began to be taught not only in theological seminaries, but also in medical institutes.

However, first things first. Glory came to her in 1969 , when the book mentioned above became a bestseller, and the course she created began to be taught not only in theological seminaries, but also in medical institutes.

Kubler-Ross decided to devote her life to correcting a serious problem that she saw in the medicine of that time: as soon as it became obvious that a person was dying, they literally stopped paying attention. In other words, then there was practically no such thing as palliative care. Medicine set itself the task of helping patients who could be cured, but paid almost no attention to alleviating the suffering of those who can no longer be helped .

Thanks to the efforts of Kübler-Ross, more than 2500 hospices have been opened in the USA. In addition, it is thanks to her that modern medicine pays such significant attention to palliative care.

Alas, despite all the merits, her reputation was completely destroyed. The reason was that in dealing with dying patients, as well as with those who have recently lost loved ones, she paid considerable attention to the spiritual aspects. She believed in an afterlife, so she often brought people who turned to her with charlatan mediums.

The reason was that in dealing with dying patients, as well as with those who have recently lost loved ones, she paid considerable attention to the spiritual aspects. She believed in an afterlife, so she often brought people who turned to her with charlatan mediums.

In particular, she collaborated with a certain Jay Barham, who offered widows communication, and attractive sex, with their dead husbands (the husband's soul, of course, “infused” Barham himself). Due to dubious connections, by the end of the 1970s, all colleagues turned their backs on Kübler-Ross, and she was forced to stop her activities.

An example of using the model

American psychologist David Kessler, who co-authored a book by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, recently published an example of applying her model to the hot topic of the COVID-19 pandemic.. He formulated the 5 steps of accepting the coronavirus as follows:

- Denial. "The virus is not terrible, and I certainly will not get sick!".

- Anger. "How dare you impose all these restrictions?!"

- Trade. “Okay, I will wear a mask and keep my distance. Surely nothing will happen to me then?”

- Depression. "Everything is bad, and the situation is getting worse every month."

- Humility. “The world has changed. But you just have to learn to live with it."

Criticism of the Kübler-Ross model

In the 1970s, this model became extremely popular and seemed very promising. However, today neither psychology, nor gerontology or other branches of medicine consider it reliable. Moreover, it is often directly criticized by well-known scientists. In particular, Professor Robert Kastenbaum, a recognized expert in gerontology, notes that the model is a product of a particular culture, and therefore cannot be considered universal and applicable to all cultures.