Dsm 5 categories of mental disorders

DSM | Psychology Today

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

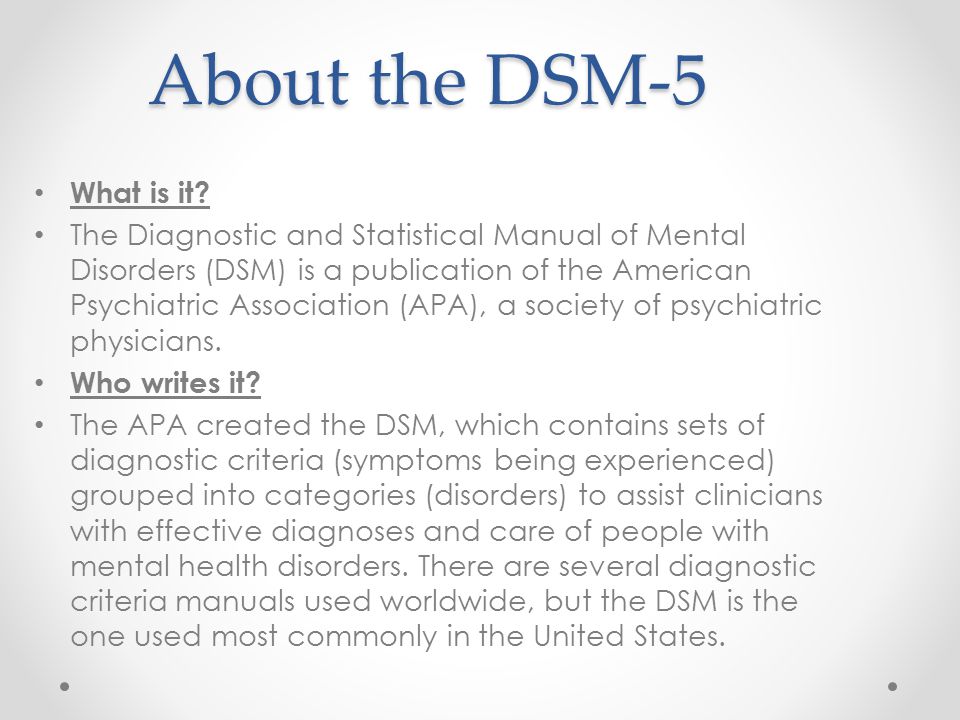

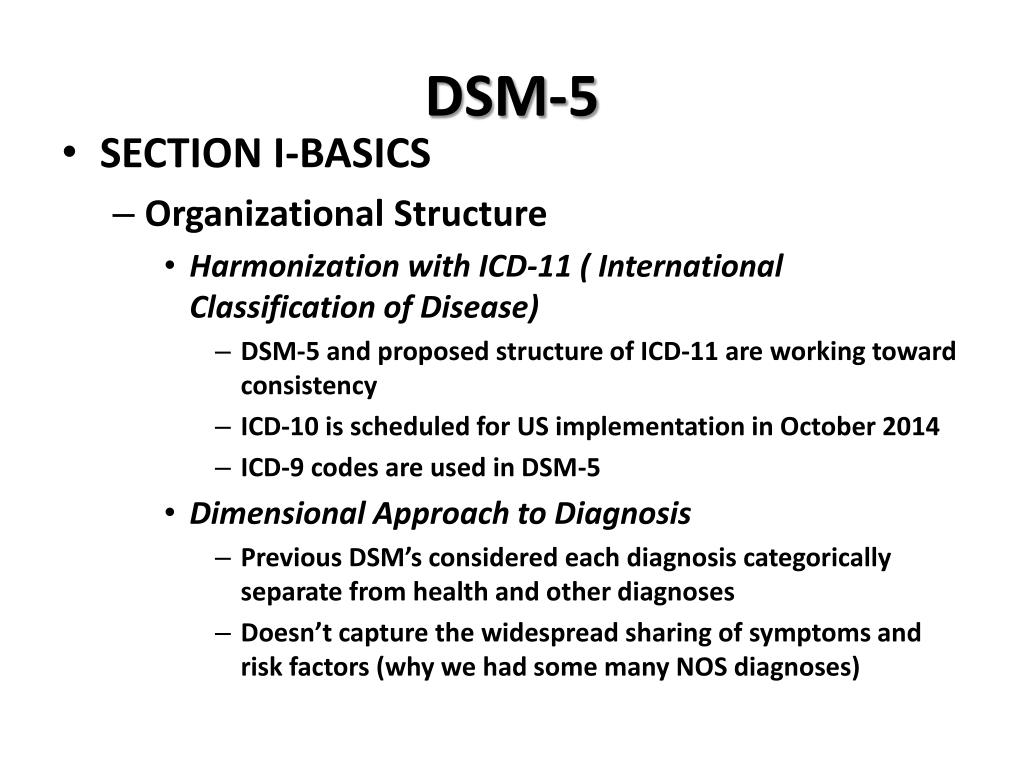

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) is a guidebook widely used by mental health professionals—especially those in the United States—in the diagnosis of many mental health conditions. The DSM is published by the American Psychiatric Association and has been revised multiple times since it was first introduced in 1952. The most recent edition is the fifth, or the DSM-5. It was published in 2013.

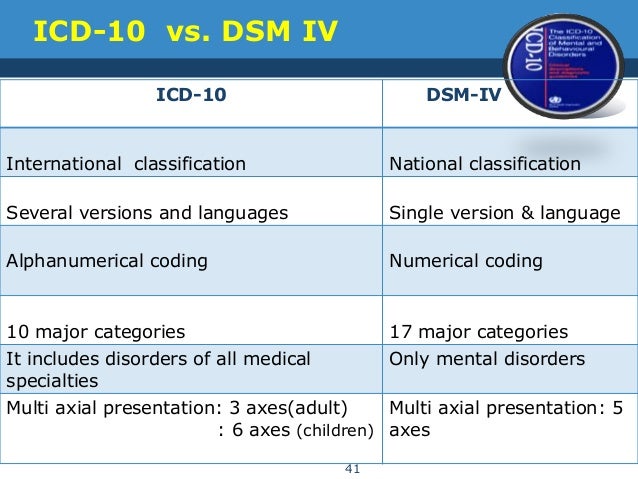

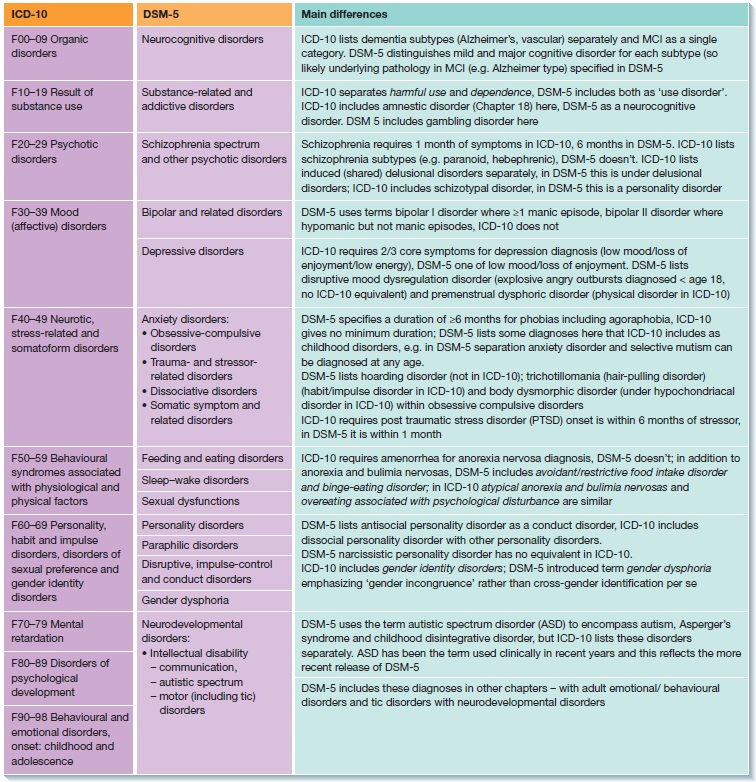

The DSM coexists with various alternative diagnostic tools, although these other guides are generally less commonly used in the U.S. The most widely consulted counterpart of the DSM, the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD), covers mental health disorders along with a vast number of other health conditions. The ICD is the primary diagnostic tool for mental health professionals outside the U.

S.

Contents

- How the DSM Is Used

- How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

How the DSM Is Used

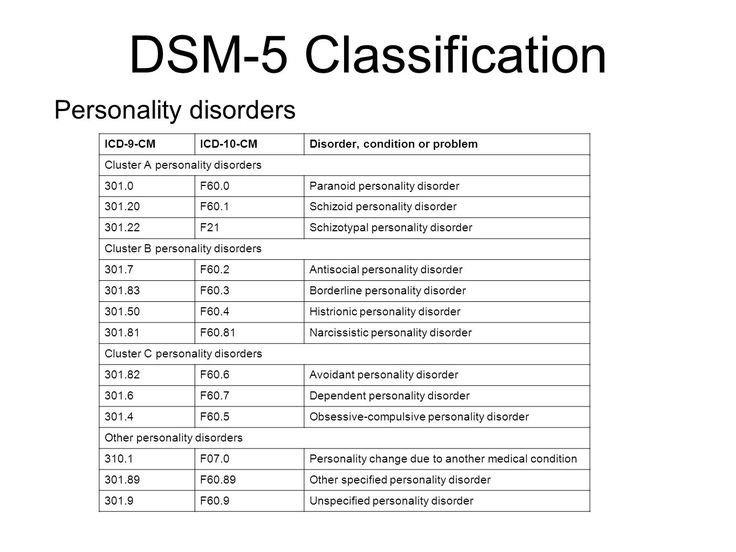

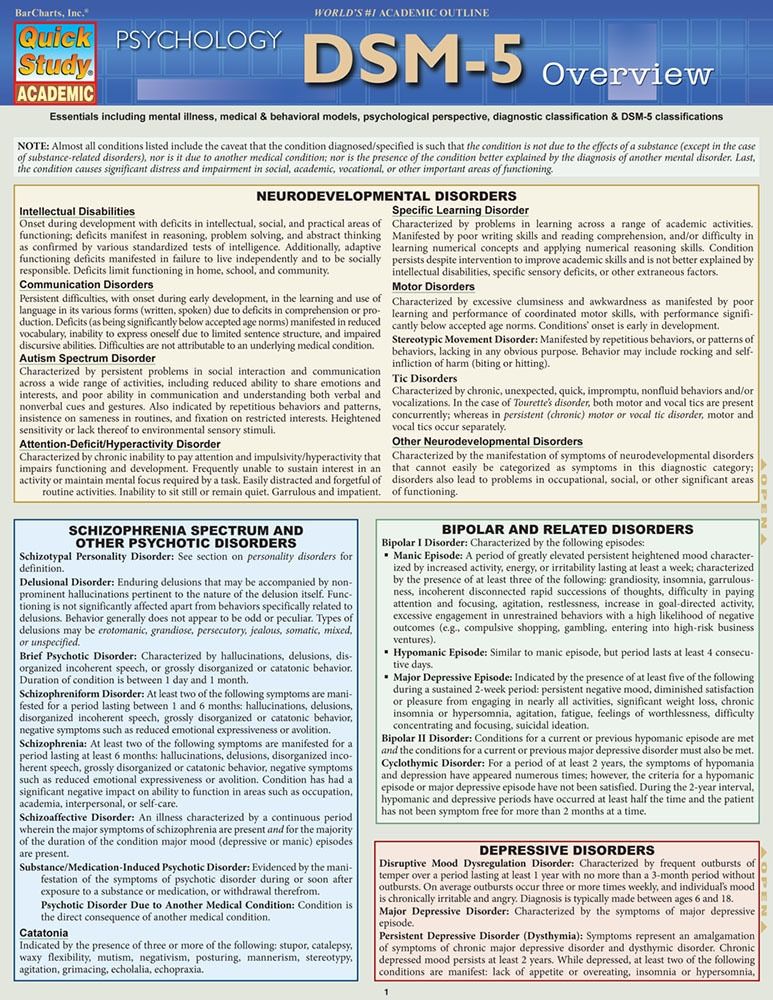

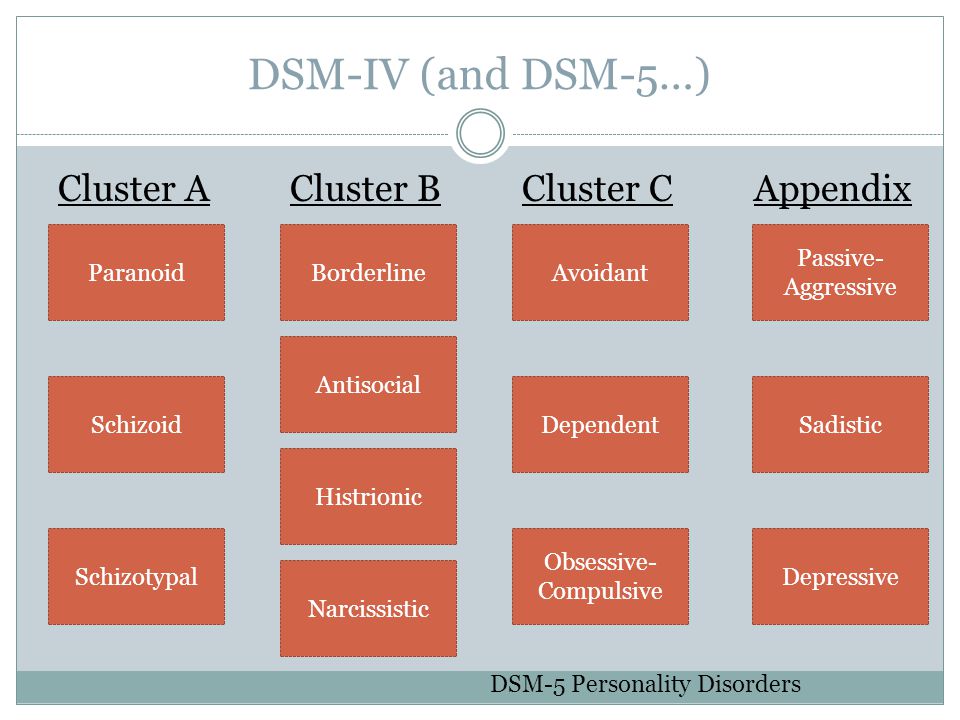

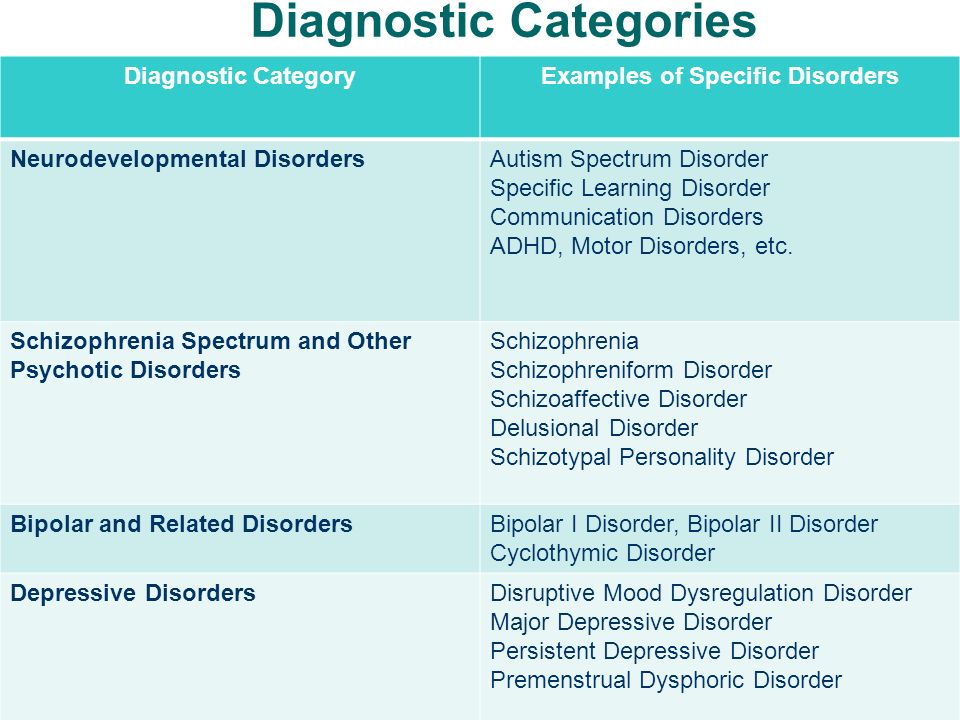

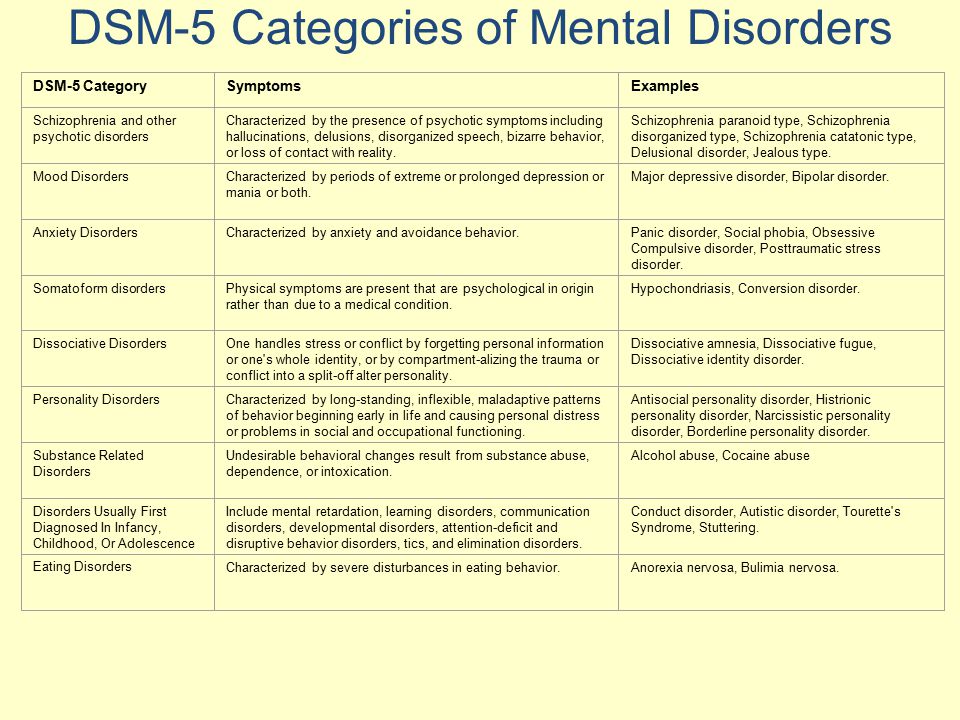

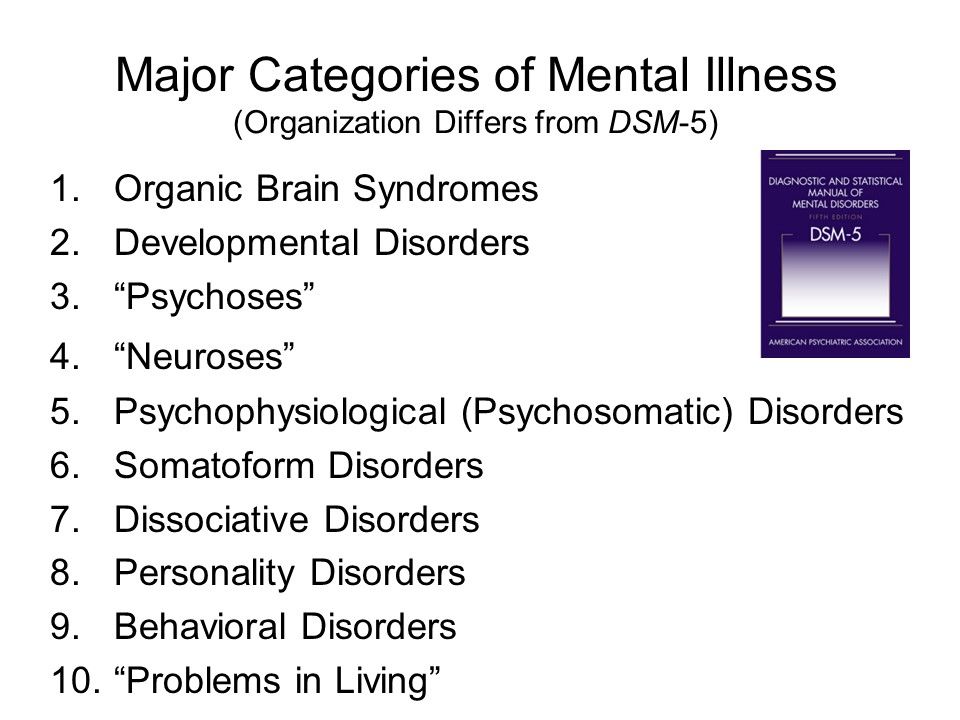

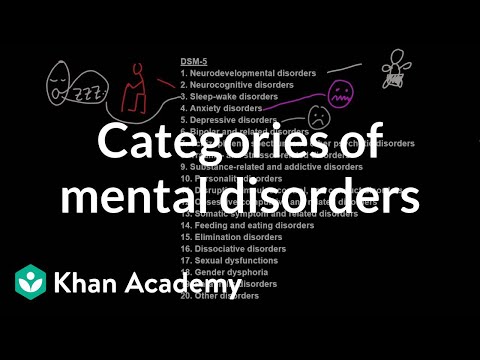

The DSM features descriptions of mental health conditions ranging from anxiety and mood disorders to substance-related and personality disorders, dividing them into categories such as major depressive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, and narcissistic personality disorder. These disorders are grouped into chapters based on shared features, e.g., Feeding and Eating Disorders; Depressive Disorders; Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders.

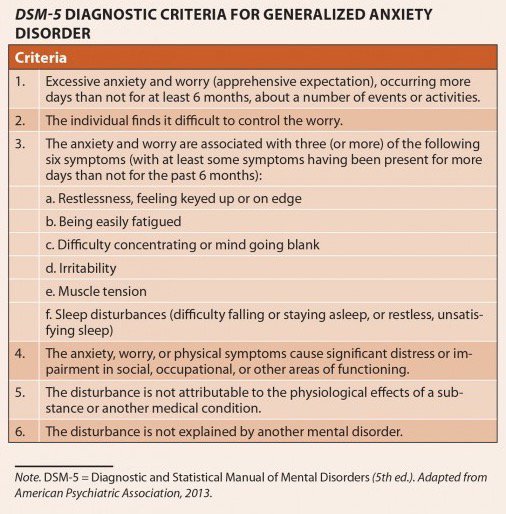

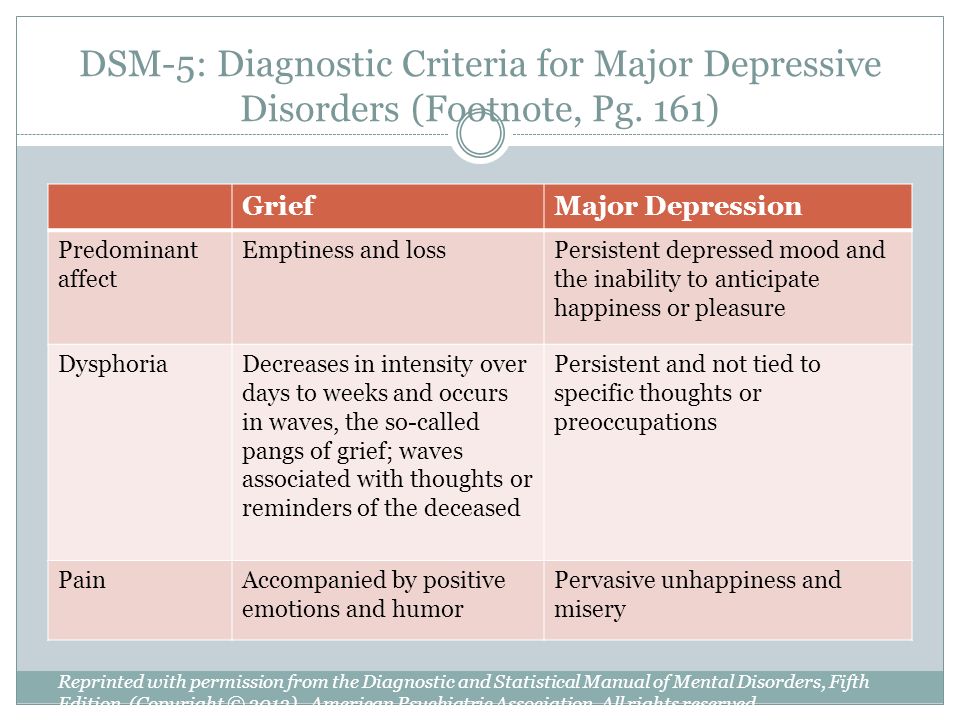

For each disorder category, the manual includes a set of diagnostic criteria—lists of symptoms and guidelines that psychiatrists, psychotherapists, and other health professionals use to determine whether a patient or client meets the criteria for one or more diagnostic categories. For diagnosis of major depressive disorder, for example, the current DSM states that a person shows at least five of a list of nine symptoms (including depressed mood, diminished pleasure, and others) within the same two-week period. It also requires that the symptoms cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,” along with other stipulations.

For diagnosis of major depressive disorder, for example, the current DSM states that a person shows at least five of a list of nine symptoms (including depressed mood, diminished pleasure, and others) within the same two-week period. It also requires that the symptoms cause “clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning,” along with other stipulations.

Updates to these diagnostic categories and criteria are made through a years-long research and revision process that involves groups of experts focusing on distinct areas of the manual.

What are the benefits of DSM?

The DSM is important for several reasons. First, it creates a common language to describe mental disorders; developing consistency is key because diagnoses are primarily based on symptoms and family history rather than more objective measures like blood tests or brain scans.

Second, diagnosis makes it possible to study treatments for mental illnesses. When people present to mental health services, professionals need to have some guide as to which treatments will best address particular collections of symptoms. Third, diagnosis facilitates research into the causes of mental disorders. If research in Peru links depression with poverty, a common concept of depression is necessary to investigate similar links in Canada.

When people present to mental health services, professionals need to have some guide as to which treatments will best address particular collections of symptoms. Third, diagnosis facilitates research into the causes of mental disorders. If research in Peru links depression with poverty, a common concept of depression is necessary to investigate similar links in Canada.

Is the DSM helpful for clinicians?

Diagnostic criteria help students and early-career professionals build templates of mental disorders that go beyond a layperson’s impressions—for instance that bipolar disorder describes abnormal moods sustained over weeks or months, not moods that shift over an hour or a day. The DSM establishes a common language for professional communication and research, not to mention insurance codes.

However, there are also ways in which mental health professionals don’t view the DSM as clinically useful. After seeing many patients, clinicians gradually form their own mental models of common diagnoses that might differ from the DSM, for example that the published criteria for a particular diagnosis is a little too wide or too narrow. In the end, clinicians may privilege the nosology of their own experience over the official manual that approximates it.

In the end, clinicians may privilege the nosology of their own experience over the official manual that approximates it.

Is the DSM helpful for researchers?

The criterion-based diagnoses listed in the DSM have improved consistency and reliability in classifying mental health conditions over time; clinicians around the world can now largely agree whether a particular patient “meets DSM criteria.” This shift in the DSM has been useful for research, in which the homogeneity of study groups is crucial.

What are some criticisms of the DSM?

Some believe that the failure to develop effective treatments for mental health disorders can in part be traced to a failure of classification, embodied by the long-standing reliance on the DSM. The DSM labels clusters of co-occurring symptoms and sorts them into disorder categories, but there is little evidence that these categories correspond to distinct biological realities. DSM categories may thereby hamper rather than facilitate psychology’s understanding of mental disorders.

DSM categories may thereby hamper rather than facilitate psychology’s understanding of mental disorders.

How the DSM Has Changed Over Time

The DSM has always been a lightning rod for debate about psychiatric diagnosis and classification. Since the 1950s, various categories of disorders have been added to the manual, altered, or removed altogether based on evolving clinical expertise and research and changes in the field of psychiatry, including a pivot away from psychoanalysis.

As the DSM is the dominant text for making mental health diagnoses in America, many of these changes are considered historically significant, such as when the DSM ceased to classify homosexuality as a form of mental illness in 1973. Other shifts have been controversial, including the omission of Asperger’s disorder from the DSM-5 in favor of a broader autism spectrum disorder category.

What are the current disorder categories in the DSM-5?

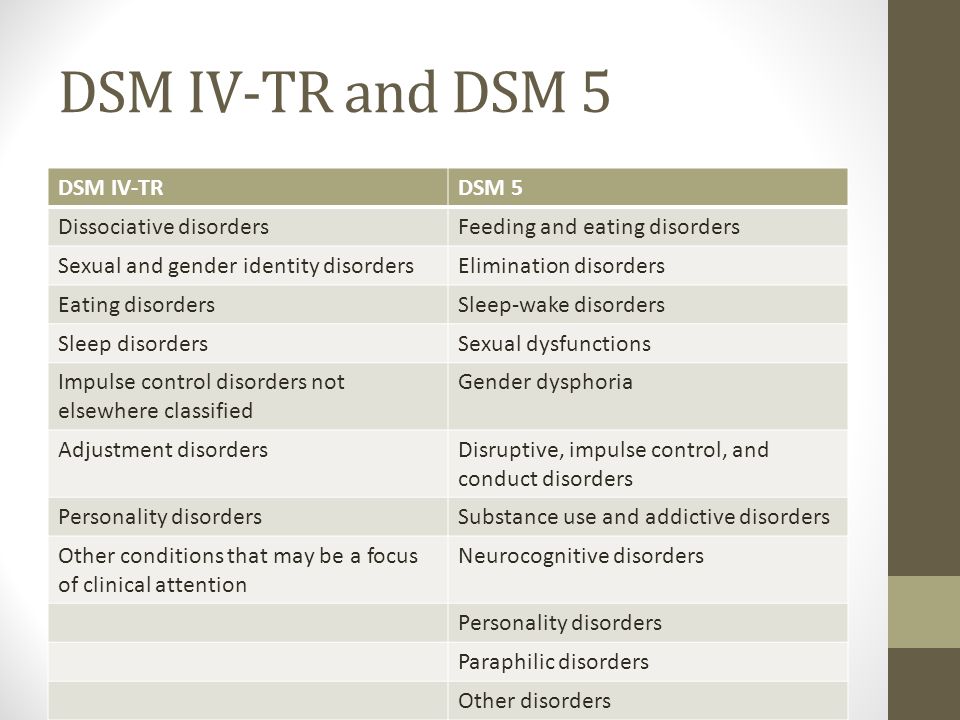

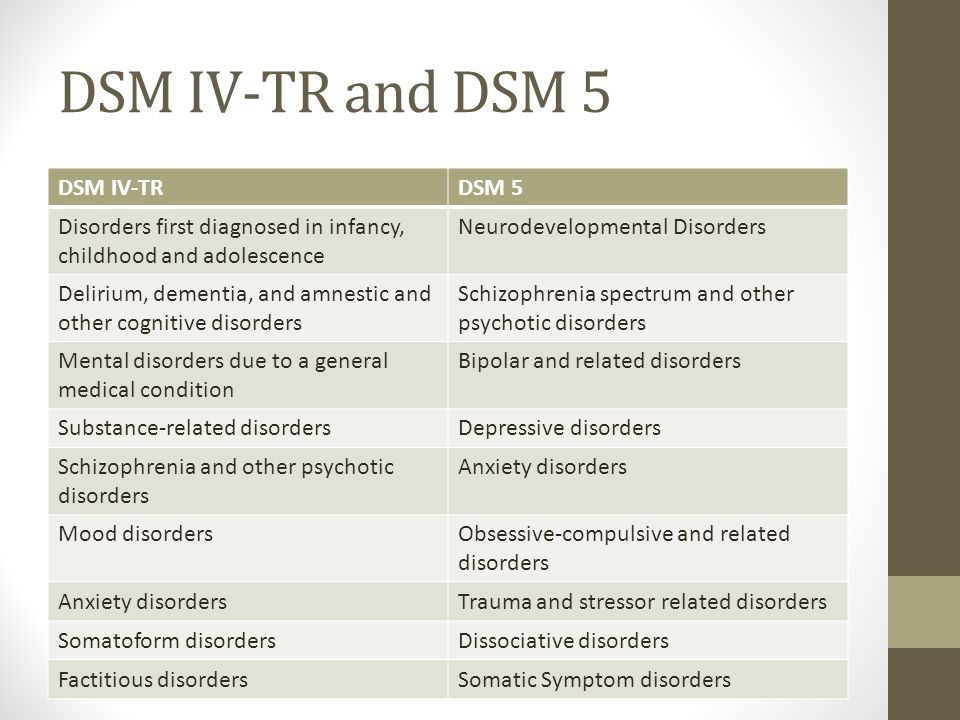

The DSM-5 organizes mental disorders into the following chapters: Neurodevelopmental Disorders, Schizophrenia Spectrum and Other Psychotic Disorders, Bipolar and Related Disorders, Depressive Disorders, Anxiety Disorders, Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders, Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders, Dissociative Disorders, Somatic Symptom and Related Disorders, Feeding and Eating Disorders, Elimination Disorders, Sleep-Wake Disorders, Sexual Dysfunctions, Gender Dysphoria, Disruptive, Impulse-Control, and Conduct Disorders, Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders, Neurocognitive Disorders, Personality Disorders, Paraphilic Disorders, Other Mental Disorders, Medication-Induced Movement Disorders and Other Adverse Effects of Medication, and Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention.

What changes were incorporated into the DSM-5?

The DSM-5 departed from the previous version in several ways. A few of the key changes include:

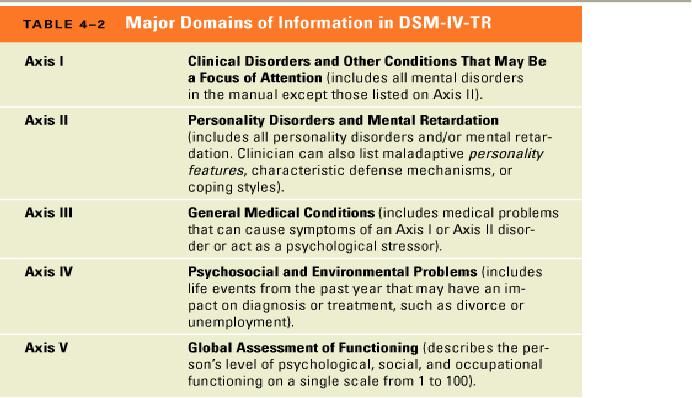

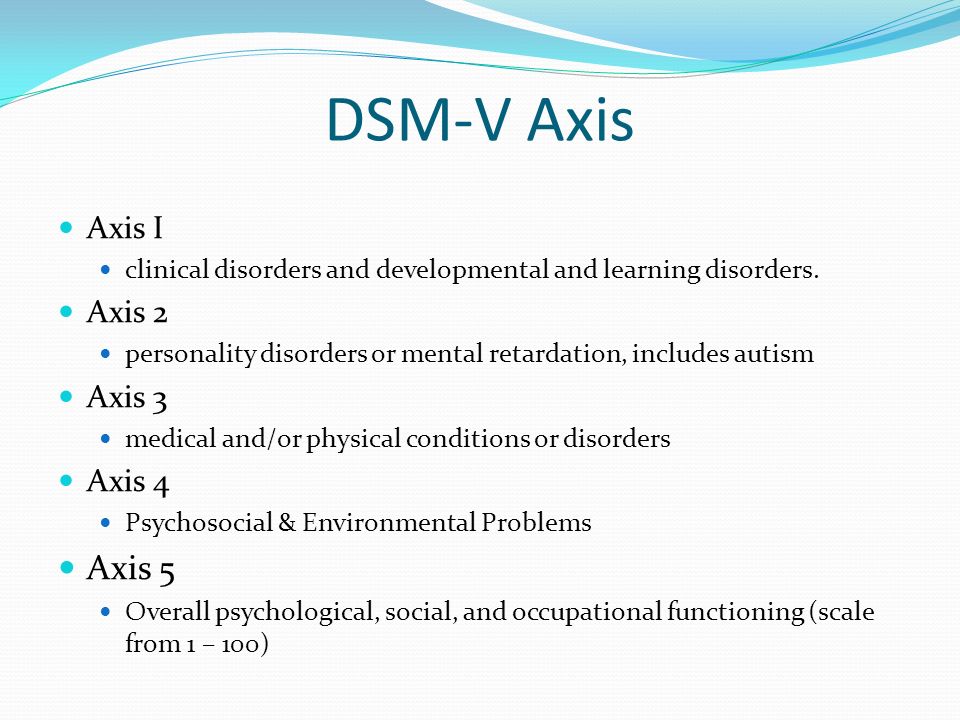

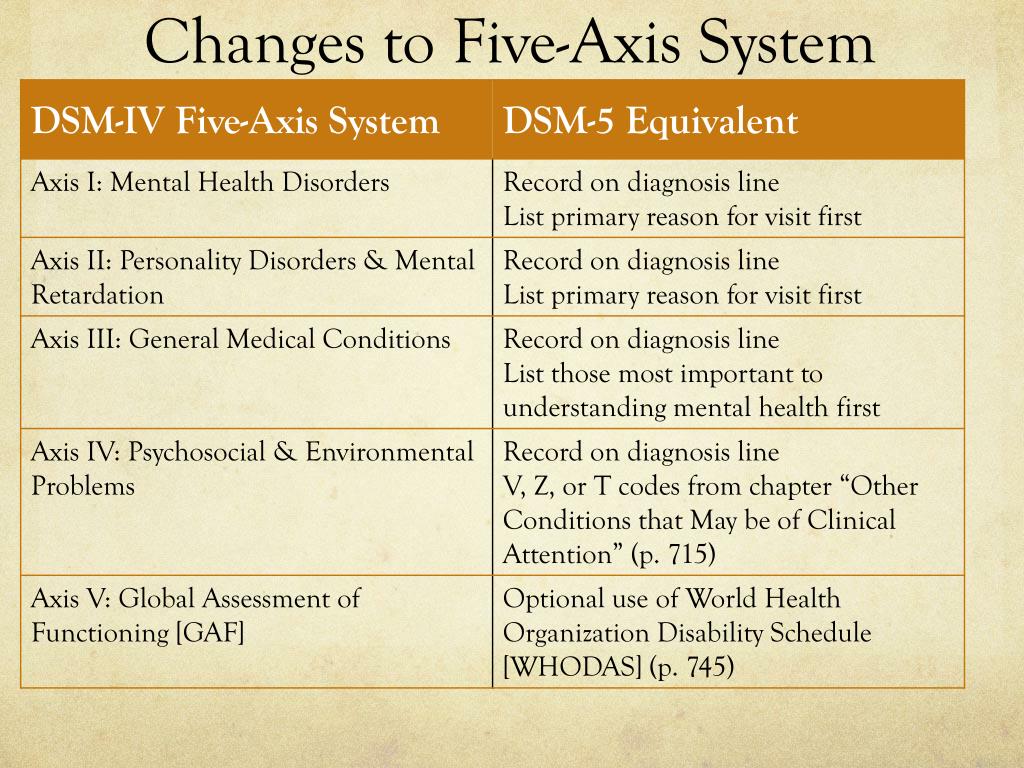

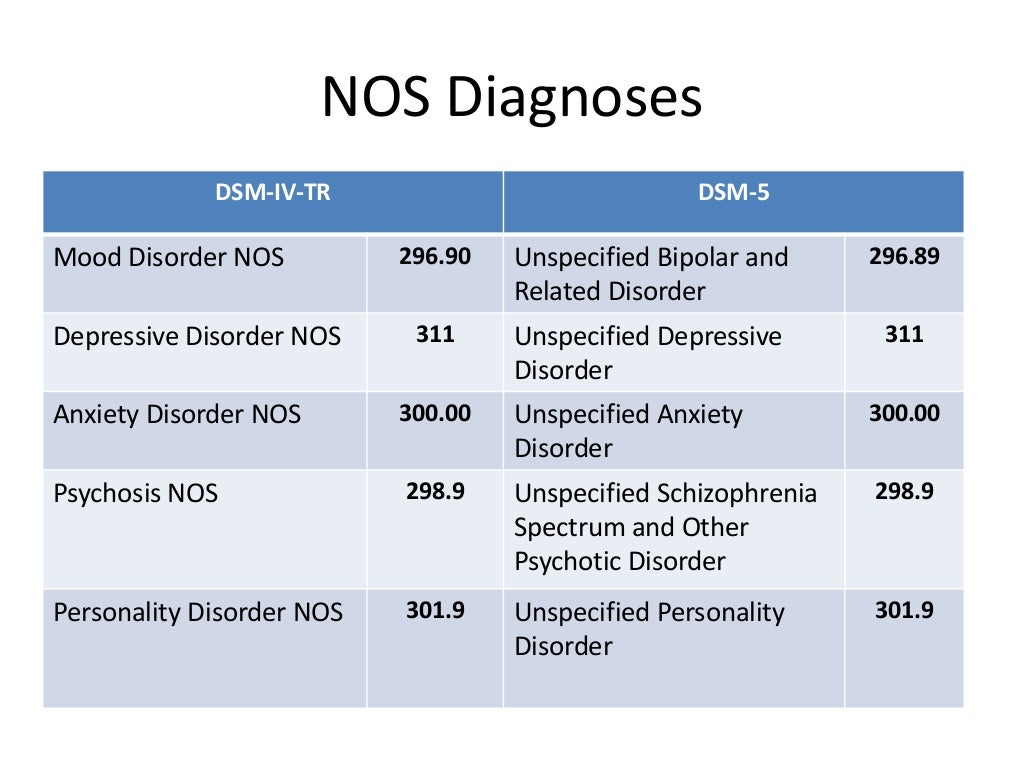

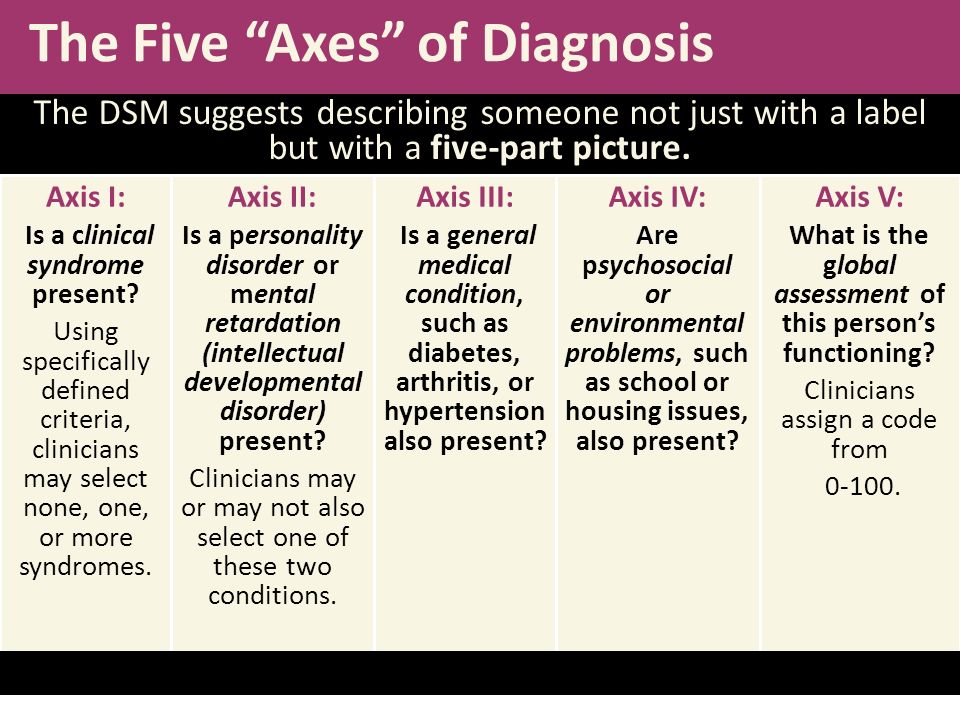

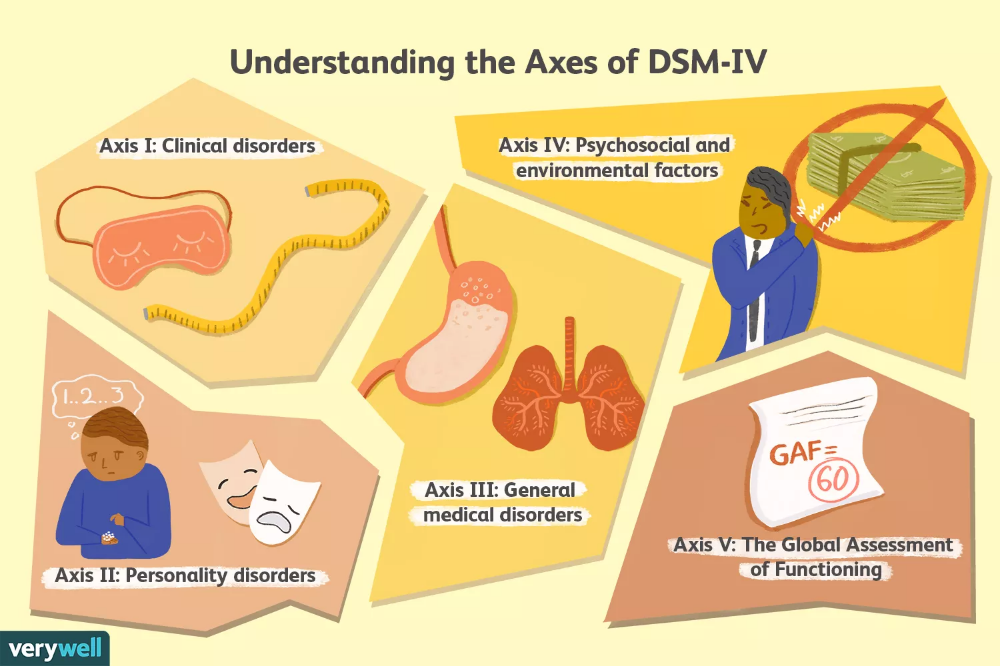

• Eliminating the multi-axial diagnostic system that required clinicians to rate each client according to criteria other than their main psychological disorder.

• Replacing the diagnoses “Autistic Disorder” and “Asperger’s Disorder” with the overarching label “Autism Spectrum Disorder.”

• Establishing “Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders” as its own group of disorders rather than an anxiety disorder.

• Establishing PTSD as a “Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorder” rather than an anxiety disorder.

• Replacing the diagnoses "Alcohol Abuse" and "Alcohol Dependence" with the overarching label "Alcohol Use Disorder," characterized as mild, moderate, or severe based on the number of symptoms present. The same goes for other diagnoses related to addiction.

• Changing diagnoses with stigmatizing terminology, such as replacing the diagnosis “Mental Retardation” with “Intellectual Disability. ”

”

• Removing the exception of bereavement for the diagnosis of Major Depressive Disorder.

• Adding the diagnosis “Mild Neurocognitive Impairment” to categorize cognition problems in old age.

• Reclassifying childhood disorders such as ADHD as neurodevelopmental disorders.

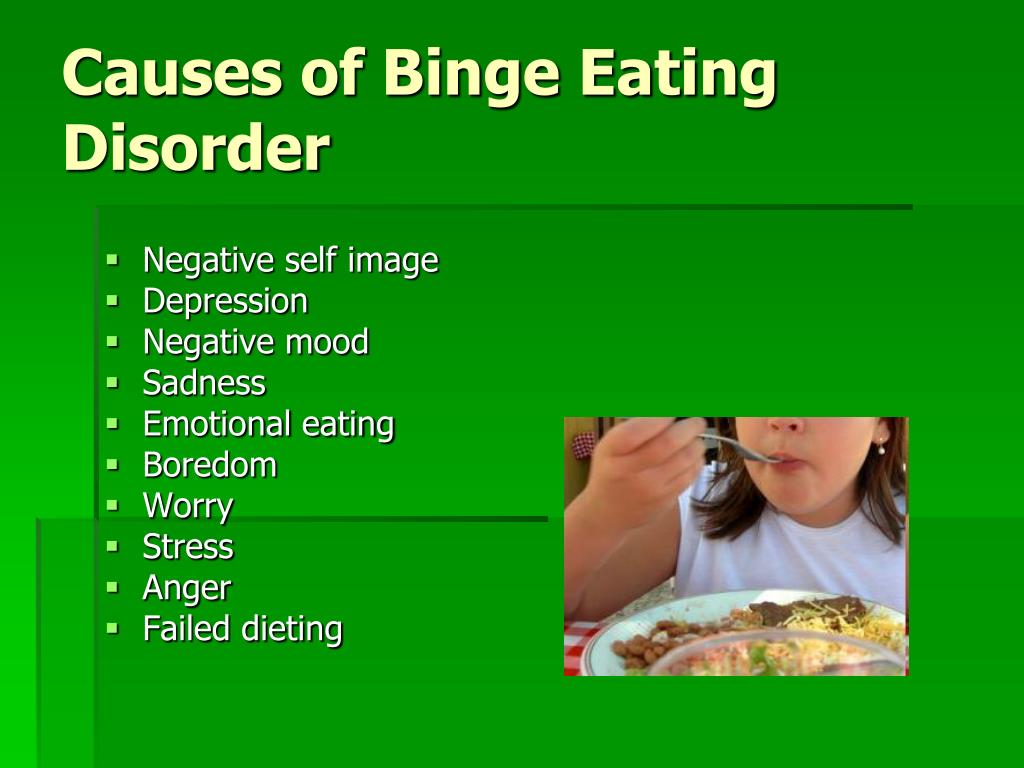

• Adding the diagnosis of “Binge-Eating Disorder.”

What are some criticisms of the changes made to the DSM-5?

Some psychiatrists believe that elements of the DSM-5 are deeply flawed. “Excessive ambition combined with disorganized execution led inevitably to many ill-conceived and risky proposals,” writes Allen Frances, chair of the DSM-IV Task Force and a professor emeritus at Duke, which could lead to misdiagnosis and overprescribing, especially for children.

The most concerning changes of the DSM-5, Frances believed, include incorporating grief into major depressive disorder, diagnosing typical forgetting in old age as Minor Neurocognitive Disorder, and introducing the concept of behavioral addictions.

Are there alternative diagnostic manuals to the DSM?

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD), published by the World Health Organization, is the best known and most popular alternative to the DSM. It contains diagnostic codes used for tracking incidence and prevalence rates, as well as for health insurance reimbursement, for mental and physical disease diagnoses.

Other alternatives to the DSM include the Psychodynamic Diagnostic Manual (PDM), Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP), Research Domain Criteria (RDoC), and Power Threat Meaning Framework (PTMF).

What is HiTOP?

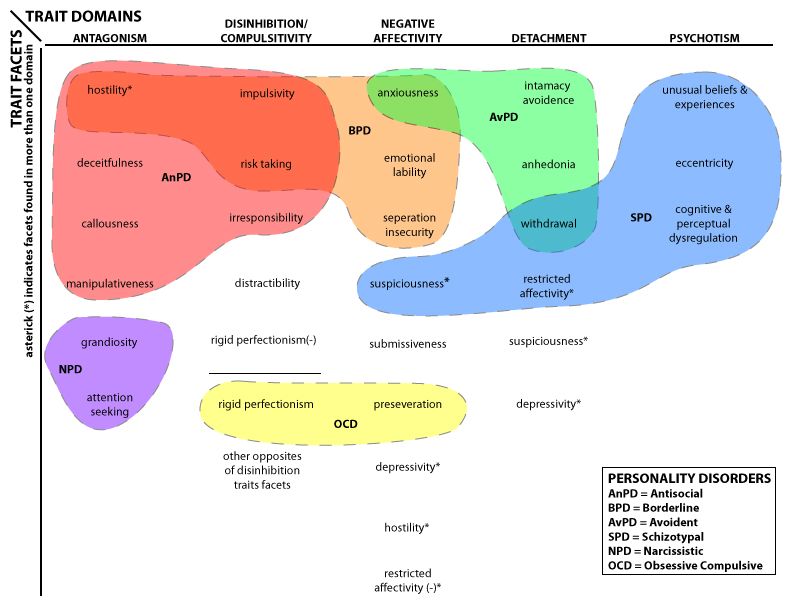

The Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP)—accounts for mental illness at multiple conceptual levels. It covers specific symptoms (such as avoidance, social anxiety, and suicidality) and traits (callousness, distractibility), but also more general factors with names such as Distress and Fear. The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The DSM, by contrast, tends to be categorical and binary.

The HiTOP model is dimensional: A person can score low, high, or somewhere in between on various measures. These severity scores can apply to the more general factors of psychopathology as well as to the narrower ones. As proponents of the model note, evidence suggests that most kinds of psychopathology lie on a continuum with normality.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

What Are the New Classifications in the DSM-5?

Diagnosis is the cornerstone of any mental health clinician’s patient care. To make an accurate diagnosis of any mental health disorder, you need the most up-to-date inf

ormation available in the DSM. The most recent DSM is the fifth edition, which introduced a host of changes from the previous version. Understanding the updates is essential to providing correct diagnoses and selecting appropriate treatment in clinical practices.

Table of Contents

- What Is the DSM?

- What Have Been the Major Changes of DSM-5?

- New and Updated Diagnoses

- Classifications With New DSM-5 Criteria

- DSM-5 Codes and ICD-10-CM

- Strengths and Weaknesses of DSM-5

- Viability for Research

- Developments for the Next DSM

- Updates to Intellectual Disability

- ICANotes: Your Source for DSM Information

What Is the DSM?

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition, also known as DSM-5, is the handbook currently used by U. S. behavioral and mental health professionals to make diagnoses. Many people consider the DSM the “Bible” of the mental health field, providing descriptions and classifications of mental disorders, including their symptoms and other criteria required for diagnosis. The DSM gives clinicians a common language to use when communicating information about patients, and researchers a shared basis to study disorders and recommend potential revisions. The DSM has been instrumental in driving advanced research on every aspect of mental and behavioral health. The first DSM came out in 1952 and has undergone several revisions as researchers’ knowledge of mental disorders has evolved. DSM-5 arrived in 2013, bringing multiple updates to mental illness classification that have, in some cases, stirred controversy in the field. The revision process that created DSM-5 lasted nearly a decade and involved nearly 400 scientists and more than 160 renowned clinicians and researchers from around the world. The American Psychiatric Association approved all proposed changes, and a Scientific Review Committee reviewed the strength of the evidence of each modification with a template of validators.

S. behavioral and mental health professionals to make diagnoses. Many people consider the DSM the “Bible” of the mental health field, providing descriptions and classifications of mental disorders, including their symptoms and other criteria required for diagnosis. The DSM gives clinicians a common language to use when communicating information about patients, and researchers a shared basis to study disorders and recommend potential revisions. The DSM has been instrumental in driving advanced research on every aspect of mental and behavioral health. The first DSM came out in 1952 and has undergone several revisions as researchers’ knowledge of mental disorders has evolved. DSM-5 arrived in 2013, bringing multiple updates to mental illness classification that have, in some cases, stirred controversy in the field. The revision process that created DSM-5 lasted nearly a decade and involved nearly 400 scientists and more than 160 renowned clinicians and researchers from around the world. The American Psychiatric Association approved all proposed changes, and a Scientific Review Committee reviewed the strength of the evidence of each modification with a template of validators.

What Have Been the Major Changes of DSM-5?

Broadly, the DSM’s overhaul entails five overarching changes meant to make diagnostics easier and more accurate for clinicians. These changes for mental and behavioral disorders include the following.

- Developmental focus: DSM-5 places disorders according to the age at which they are most likely to appear, starting in childhood and ending with disorders that usually occur in old age. Descriptions of disorders also include the different ways they might present according to age.

- New diagnostic criteria: Criteria for some disorders will change, including the addition of new disorders and removal of subtypes of schizophrenia.

- Dimensional measures: DSM-5 includes measures of a disorder’s severity to help clinicians think about what dimensions of disorders are similar. These measures aim to benefit patients with multiple diagnoses by providing more nuanced insight into their continuum of symptoms.

- Culture and gender emphasis: A multitude of cultural and social factors can impact diagnosis. DSM-5 has a new section describing cultural syndromes, their potential causes and how people express them.

- Further research: The DSM now contains a section that describes conditions that need further research. Future editions of the DSM may or may not add these conditions based on the results of ongoing research. They currently do not have ICD codes clinicians can use to diagnose patients and receive reimbursement from insurance companies.

New and Updated Diagnoses

The DSM-5 classifications include updates and additions for many mental disorders. Clinicians and researchers have eliminated some classifications and combined others. The following 17 mental disorders are new or updated in DSM-5.

- Social communication disorder: This addition allows clinicians to diagnose speech and language issues that aren’t symptoms of reduced cognitive ability or autism.

- Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder: This diagnosis applies to children under 18 who display extreme rages and frequent outbursts, eliminating the classification of childhood bipolar disorder.

- Premenstrual dysphoric disorder: This extremely controversial addition affects up to 5% of premenopausal women.

- Hoarding disorder: This condition, depicted in multiple TV shows, is now an official diagnosis listed under obsessive-compulsive disorders.

- Caffeine withdrawal: Another divisive addition, caffeine withdrawal has moved from the appendix of DSM-IV to “Caffeine-Related Disorders” in DSM-5.

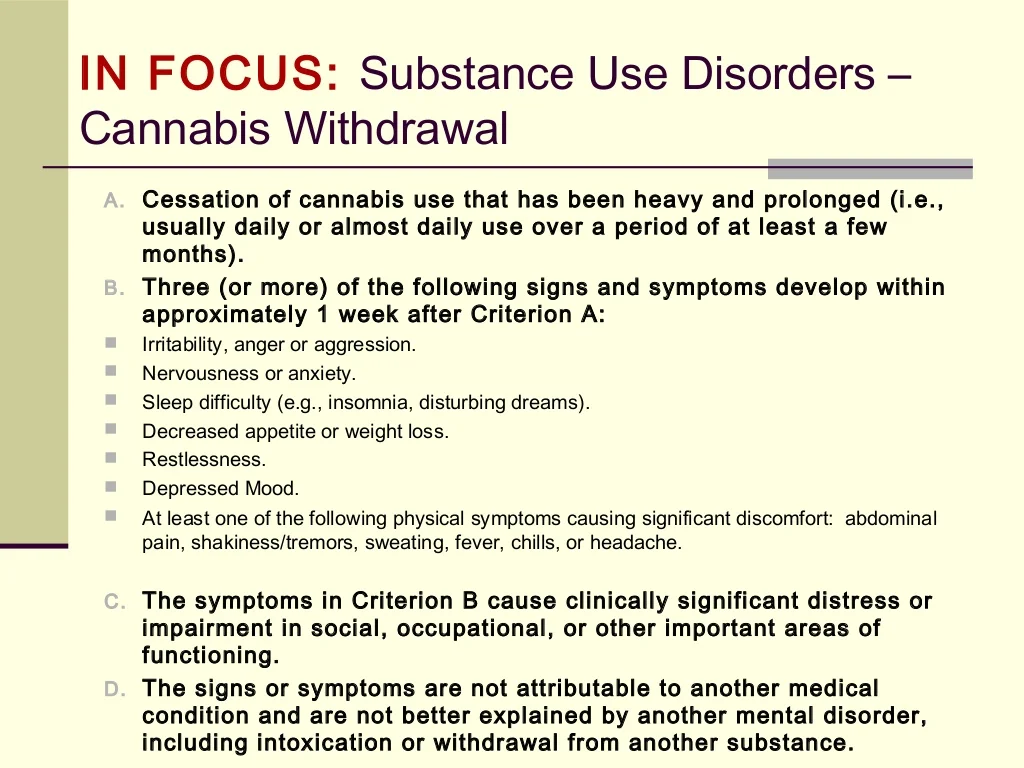

- Cannabis withdrawal: The proliferation of legal cannabis led to a pronounced increase in people experiencing cannabis withdrawal, which now falls under “Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders.”

- Excoriation disorder: This diagnosis addresses chronic scratching and picking at the skin, and is under “Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders.

”

” - Binge eating disorder: Binge eating even once a week now qualifies a patient for this diagnosis, rather than biweekly.

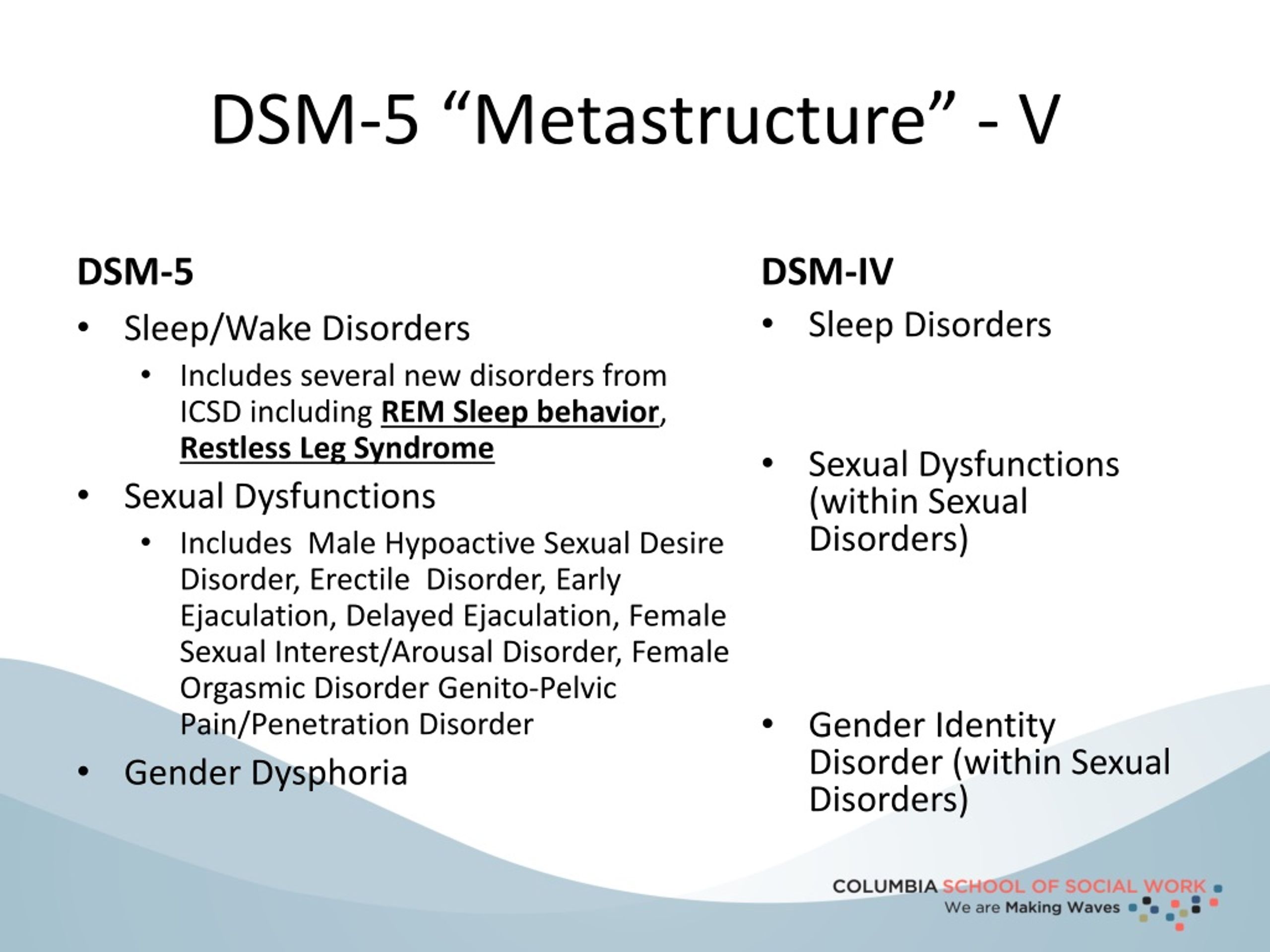

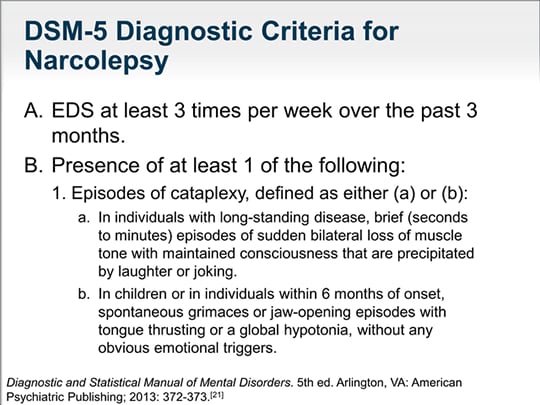

- Rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: This disorder causes people to act out dreams in potentially dangerous ways, and is now separate from the parasomnia category it occupied in the previous DSM.

- Restless leg syndrome: Previously classified as a form of dyssomnia, restless leg syndrome now has full DSM status as a separate diagnosis.

- Major neurocognitive disorder with Lewy body disease: This classification differentiates major and mild neurocognitive disorders, allowing for more specific treatment.

- Disinhibited social engagement disorder: This classification previously fell under reactive attachment disorder, but is now under a separate category because children with it do not necessarily lack attachment.

- Additional eating disorders: In addition to recognizing binge eating disorder, the newest edition of the DSM adds rumination, pica and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder.

- Gender dysphoria: Individualswhose gender at birth is contrary to the one they identify with will now receive a diagnosis of gender dysphoria instead of gender identity disorder. The shift in language intends to represent these individuals’ experiences more accurately and reduce stigma. Gender dysphoria will also now have a dedicated chapter separate from sexual dysfunctions and paraphilic disorders.

- Specific learning disorder: Specific learning disorder is now a single, stand-alone category. It contains different specifiers to indicate more narrowly defined types of learning disorders, such as dyslexia, that affect reading, writing or math. It also replaces the IQ-achievement discrepancy requirement with characteristic-based criteria.

- Gambling disorder: The chapter on addictive disorders now includes gambling disorder as a diagnosable condition. The DSM-IV included a section on pathological gambling but did not classify it as an official addictive disorder.

- Somatic symptom disorder: DSM-5 replaces the old somatoform disorders — such as somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder and undifferentiated somatoform disorder — with somatic symptom disorder. It makes substantial changes to the disorder criteria to clarify the distinctions between similar conditions and minimize overlap.

Classifications With New DSM-5 Criteria

In addition to the diagnoses added to DSM-5, several mental disorders in the fifth edition have new criteria, including:

- Autism spectrum disorder: One of the most crucial changes involving collapsing diagnoses deals with autism spectrum disorder. In DSM-IV, there were four categories: autism, Asperger’s, childhood disintegrative disorder and pervasive developmental disorder. DSM-5 collects all four under the umbrella of autism spectrum disorder.

- ADHD: Revisions to the ADHD diagnosis have broadened the criteria to allow for adult-onset cases.

Because adult brains are more developed and adults have better impulse control, clinicians can diagnose them with fewer symptoms than children.

Because adult brains are more developed and adults have better impulse control, clinicians can diagnose them with fewer symptoms than children. - PTSD: Due to the new research on PTSD available, DSM-5 has expanded detail on this diagnosis. The new criteria add more information on diagnosing children and create four separate classes of symptoms: arousal, avoidance, flashbacks and negative impacts on mood and thought patterns.

- Mental retardation: Asa result of DSM-5’s new focus on cultural relevance, it has reclassified the collection of issues called “mental retardation” as “Intellectual Development Disorder” to reflect changes in everyday language. The criteria for diagnosis have also shifted to focus more on level of function, instead of relying so heavily on IQ score.

- Major depressive disorder: The new addition removes the exclusion that prevented many recently bereaved individuals from receiving a major depressive disorder diagnosis.

- Conduct disorder: The update to conduct disorder adds a descriptive features specifier to the diagnosis. The specifier identifies symptoms, such as limited empathy and little concern for others’ feelings and well-being, that extend beyond the general presence of negative behavior. It will help clinicians identify and diagnose individuals who experience a more severe form of this disorder and require more individualized, intensive treatment.

- Minor neurocognitive disorder: Minor neurocognitive disorder previously required only a single criterion —neuropsychological testing results — for diagnosis. DSM-5 defines this disorder using several cognitive and related criteria instead. The revision will enable early detection and treatment of cognitive decline before it develops into major neurocognitive disorder, or dementia.

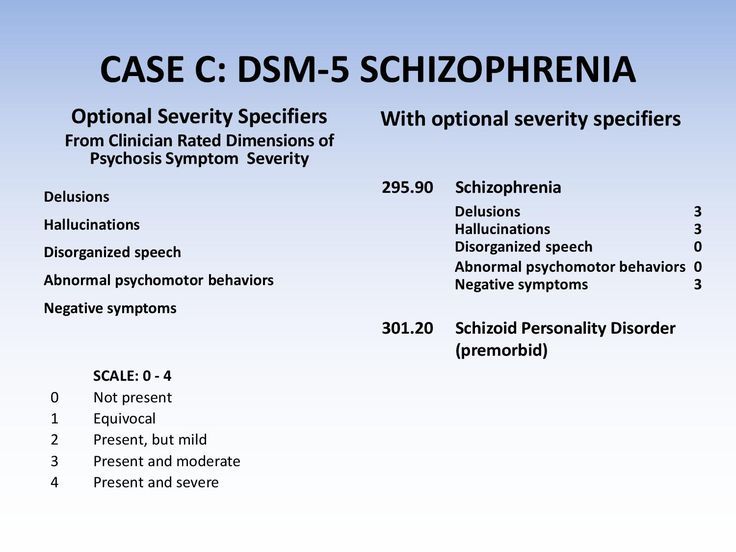

- Schizophrenia: For schizophrenia, DSM-5 raises the symptom threshold for diagnosis. An individual must now exhibit at least two of the potential symptoms to receive a diagnosis.

The diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia also no longer identify subtypes, since these predominant symptoms tended to shift throughout the patient’s life. Some of the subtypes, such as catatonia, have now become specifiers for schizophrenia and other disorders.

The diagnostic criteria for schizophrenia also no longer identify subtypes, since these predominant symptoms tended to shift throughout the patient’s life. Some of the subtypes, such as catatonia, have now become specifiers for schizophrenia and other disorders. - Sleep-wake disorders: The sleep-wake disorders in the DSM have undergone a few diagnostic updates, many of which remove the distinction between primary and secondary disorders.

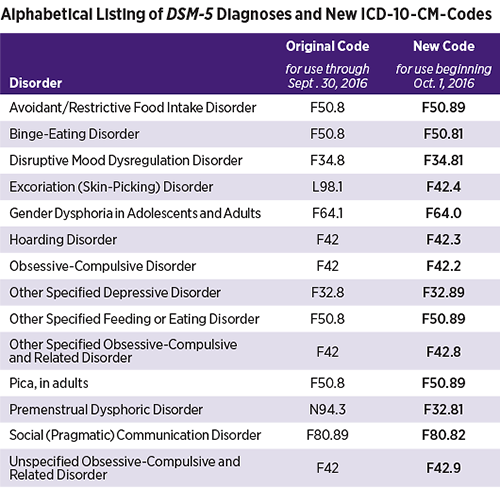

DSM-5 Codes and ICD-10-CM

The DSM and the World Health Organization’s International Classification of Disease are companion publications. The DSM contains diagnostic criteria, while the ICD codes monitor mortality and morbidity statistics and are necessary for insurance reimbursement. There are no DSM codes. Instead, the numbers you will find next to diagnoses in the manual are ICD codes. The manual contains ICD-9 codes in bold and new ICD-10 codes in parentheses. Many codes stayed the same between ICDs, but it is vital to note any changes between ICD codes, as clinicians switched to using ICD-10 in 2015. Several disorders have recently received coding updates. The following disorders or conditions initially had no ICD-10-CM codes in DSM-5. They have now had recommended codes since October 2020.

Several disorders have recently received coding updates. The following disorders or conditions initially had no ICD-10-CM codes in DSM-5. They have now had recommended codes since October 2020.

- Alcohol withdrawal, uncomplicated, with mild use disorder: F10.130

- Alcohol withdrawal, delirium, with mild use disorder: F10.131

- Alcohol withdrawal, with perceptual disturbance, with mild use disorder: F10.132

- Alcohol withdrawal, with mild use disorder: F10.139

- Alcohol withdrawal, uncomplicated, with use disorder: F10.930

- Alcohol withdrawal, delirium, without use disorder: F10.931

- Alcohol withdrawal, with perceptual disturbance, without use disorder: F10.932

- Alcohol withdrawal, without use disorder: F10.939

- Opioid withdrawal, with mild use disorder: F11.13

- Cannabis withdrawal, with mild use disorder: F12.

13

13 - Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic withdrawal, uncomplicated, with mild use disorder: F13.130

- Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic withdrawal, delirium, with mild use disorder: F13.131

- Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic withdrawal, with perceptual disturbance, with mild use disorder: F13.132

- Sedative, hypnotic or anxiolytic withdrawal, unspecified, with mild use disorder: F13.139

- Cocaine withdrawal, with mild use disorder: F14.13

- Cocaine withdrawal, without use disorder: F14.93

- Amphetamine or other stimulant withdrawal, with mild use disorder: F15.13

- Other (or unknown) substance withdrawal, uncomplicated, with mild use disorder: F19.130

- Other (or unknown) substance withdrawal, delirium, with mild use disorder: F19.131

- Other (or unknown) substance withdrawal, with perceptual disturbance, with mild use disorder: F19.

132

132 - Other (or unknown) substance withdrawal, unspecified, with mild use disorder: F19.139

Strengths and Weaknesses of DSM-5

There is always some disagreement between professionals on the best diagnostic and treatment approaches, and continuing research brings more information that drives revisions to the DSM. Some clinicians have enthusiastically greeted many new classifications in DSM-5, while others insist the same changes are detrimental. Some of the most significant controversies and problems with DSM-5 include the following.

1. Grief and Major Depression

The previous DSM had a bereavement exclusion for major depressive disorder. Using DSM-IV, clinicians could not diagnose people who had recently experienced a loved one’s death with depression unless:

- Symptoms lasted longer than two months.

- Symptoms produced functional impairment.

- The patient had a morbid preoccupation with worthlessness.

- There was suicidal ideation, psychotic symptoms or psychomotor retardation.

DSM-5 has replaced the bereavement exclusion with a note that provides further guidance on how to tell grief apart from major depression. There is now another guide for recording reactions to a loved one’s death, found in the chapter “Other Conditions That May Be a Focus of Clinical Attention.” Clinicians who oppose eliminating the bereavement exclusion are concerned that removing it will lead to people with normal grief receiving an inappropriate depression diagnosis.

2. Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Oppositional defiant disorder was highly controversial when added to DSM-IV, and the outcry has continued, as it remains a diagnosis in DSM-5. The condition has these characteristics:

- Using obscene language

- Angry outbursts

- Frequent resentment

- Intentionally irritating or hurting others

- Being easily angered

- Refusing to follow instructions or rules

- Throwing temper tantrums repeatedly

The DSM-5 stipulates that these behavioral patterns must last for six months or more and not result from a different mental health issue. The controversy here is that the relatively lax criteria may lead to over-diagnosis of what may only be bad behavior. It can be severely damaging to label a child or teen “mentally ill” when they may not be.

The controversy here is that the relatively lax criteria may lead to over-diagnosis of what may only be bad behavior. It can be severely damaging to label a child or teen “mentally ill” when they may not be.

3. Pediatric Bipolar Disorder

While ODD remained in the DSM, a diagnosis some clinicians have been asking for is still missing. Rather than adding a diagnosis for pediatric bipolar disorder, also known as child-onset bipolar disorder, DSM-5 introduced disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. DMDD focuses on temper tantrums and general anger rather than addressing all the symptoms of pediatric bipolar disorder, so clinicians must create a workaround. The closest thing to a diagnosis of pediatric bipolar disorder is a combination of DMDD diagnosed alongside major depression. These two diagnoses can occur together, but clinicians cannot combine DMDD and bipolar.

Viability for Research

While the DSM’s creators intended it to function as a common language for researchers to use, it seems the manual has not accomplished part of its mission. According to many experts, DSM-5 does not provide a strong foundation for studying mental illnesses. The National Institute of Mental Health has rejected DSM-5 for research purposes and has shifted its funding away from DSM categories to more neuroscience-based sources. However, this announcement was not a rejection of the DSM outright. Instead, NIMH clarified that while the DSM may no longer be sufficient for researchers, it remains the gold standard for clinical diagnosis.

According to many experts, DSM-5 does not provide a strong foundation for studying mental illnesses. The National Institute of Mental Health has rejected DSM-5 for research purposes and has shifted its funding away from DSM categories to more neuroscience-based sources. However, this announcement was not a rejection of the DSM outright. Instead, NIMH clarified that while the DSM may no longer be sufficient for researchers, it remains the gold standard for clinical diagnosis.

Developments for the Next DSM

One of the most substantial changes for the next DSM is the shift in revision processes. The APA recognizes the need to make more timely updates to the DSM in response to breakthroughs in research. The change from the Roman numerals used through DSM-IV to the Arabic numerals in DSM-5 reflects the intention to publish incremental updates. We may soon be seeing a DSM-5.1, DSM-5.2 and more until enough cumulative updates necessitate a whole new edition.

The eight conditions identified as needing further study in DSM-5 are:

- Attenuated psychosis syndrome

- Caffeine use disorder

- Depressive episodes with short-duration hypomania

- Internet gaming disorder

- Neurobehavioral disorder associated with prenatal alcohol exposure

- Non-suicidal self-injury

- Persistent complex bereavement disorders

- Suicidal behavior disorder

Though these conditions do not have formal diagnoses in DSM-5, they will be the first up for consideration in updates to mental illness classification. The information on them is in the DSM to give clinicians more details that may influence the diagnosis of other conditions. For example, someone addicted to caffeine can only receive a diagnosis of a substance-related and addictive disorder, but the diagnosing clinician can gain more insight into the situation by reading the caffeine use disorder section.

The information on them is in the DSM to give clinicians more details that may influence the diagnosis of other conditions. For example, someone addicted to caffeine can only receive a diagnosis of a substance-related and addictive disorder, but the diagnosing clinician can gain more insight into the situation by reading the caffeine use disorder section.

Updates to Intellectual Disability

One of the formally proposed DSM-5 updates regards the diagnostic features section of intellectual developmental disorder. At present, the criteria for diagnosing an intellectual disability are:

- Deficiency in adaptive daily life skills or functioning.

- Deficits in intelligence.

- Onset during childhood.

DSM-5 requires that the intellectual impairments must directly relate to the deficiency in adaptive functioning. However, the APA has recommended replacing this with a criterion that specifies a lack of adaptive functioning is due to intellectual deficits. One example given by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities is the case of the state of Texas seeking to execute a man with an intellectual disability. According to the state, the man’s adaptive functions likely resulted from a lack of learning opportunities and were unrelated to his intellectual function. Therefore, he did not have any intellectual disability. In 2016, the Supreme Court ruled against the state, found that the man does have an intellectual disability, then disallowed his execution. The CEO of AAIDD, Margaret Nygren, says that experts agree it is inaccurate to connect or conflate intellect and adaptive behavior because it is impossible to determine which elements of behavior result from mental health issues, IQ or a lack of educational opportunities. The use of the current DSM-5 language in Moore v. Texas is a clear indicator that the DSM is not perfect and needs updates in this area.

One example given by the American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities is the case of the state of Texas seeking to execute a man with an intellectual disability. According to the state, the man’s adaptive functions likely resulted from a lack of learning opportunities and were unrelated to his intellectual function. Therefore, he did not have any intellectual disability. In 2016, the Supreme Court ruled against the state, found that the man does have an intellectual disability, then disallowed his execution. The CEO of AAIDD, Margaret Nygren, says that experts agree it is inaccurate to connect or conflate intellect and adaptive behavior because it is impossible to determine which elements of behavior result from mental health issues, IQ or a lack of educational opportunities. The use of the current DSM-5 language in Moore v. Texas is a clear indicator that the DSM is not perfect and needs updates in this area.

Understanding the latest DSM classifications is crucial to providing accurate diagnoses and the most appropriate course of treatment for your patients. The most recently updated ICD codes, ICD 11, became available in June 2018, and clinicians will also need to become familiar with those since they will be a reporting requirement starting in 2022. Keeping up with crucial information on the DSM and ICD codes can be time-consuming and confusing, which is why ICANotes works hard to provide up-to-date resources and information for mental and behavioral health clinicians. For additional information on DSM-5 updates and ICD changes, contact ICANotes today.

The most recently updated ICD codes, ICD 11, became available in June 2018, and clinicians will also need to become familiar with those since they will be a reporting requirement starting in 2022. Keeping up with crucial information on the DSM and ICD codes can be time-consuming and confusing, which is why ICANotes works hard to provide up-to-date resources and information for mental and behavioral health clinicians. For additional information on DSM-5 updates and ICD changes, contact ICANotes today.

Watch a Live Demo

Start a Free Trial

Related Posts

Mental & Behavioral Healthcare Billing: How to Maximize Your Reimbursement Rate

Understanding the Mental Health Crisis Facing Young People

CPT Code Basics: What You Should Know

What Is Evidence-Based Health Care?

What You Need to Know About MIPS in 2019

Sources:

- https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/feedback-and-questions/frequently-asked-questions

- https://www.

apa.org/monitor/2013/04/dsm

apa.org/monitor/2013/04/dsm - https://ajp.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11081302

- https://www.naswma.org/page/ICD10andDSM5

- https://www.aafp.org/afp/2014/1115/p690.html

- https://www.apa.org/monitor/2013/07-08/nimh

- https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/dsm/proposed-changes

- https://www.disabilityscoop.com/2019/08/12/psychiatrists-considering-change-intellectual-disability-criteria/27000/

- https://www.oyez.org/cases/2018/18-443

- https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/18-06-2018-who-releases-new-international-classification-of-diseases-(icd-11)

Last updated May 21, 2021.

October Boyles, MSN, BSN, RN

Clinical Director October has been a Registered Nurse for over 15 years. She is board certified in Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing. She holds a Bachelor of Arts from the University of North Carolina at Greensboro. She also graduated with bachelor and master degrees in Nursing from Western Governors University.

Not Found (#404)

hide menu

Issues of the current year

-

7-8 (136)

-

5-6 (135)

-

3-4 (134)

-

2 (133)

-

1 (132)

7-8 (136)

Issue content 7-8 (136), 2022

- nine0009

War Wikis: help in crisis situations

-

Ethical and legal problems of mental health: Ukraine at the focus of international respect

Yu.A. Kramar

-

Screening, diagnosis and treatment of diabetic sensorimotor polyneuropathy: consensus recommendations

-

Influx of mass information on delinquent behavior

R.

І. Isakov

І. Isakov -

Stopping programs for rukhovo ї rehabilitation for the normalization of the psychoemotional sphere of patients with Parkinson's disease

N.P. Voloshin, I.V. Bogdanova, I.K. Voloshin-Gaponov, S.V. Fedosiev, L.P. Tereshchenko, T.V. Bogdanova

-

Trauma management algorithm

-

Tipi for neuropathic pain according to the International Classification of Orofacial Pain

-

Management of patients with dementia: key provisions for diagnosis, examination and observation of life

-

Significant Pre-Raphaelism: John Ruskin and Effi Gray

5-6 (135)

3-4 (134)

2 (133)

1 (132)

Other projects of the Health of Ukraine publishing house

Specialization medical portal

nine0009 Child doctorMedical aspects of women's health

Clinical Immunology, Allergology, Infectology

Rational pharmacotherapy

nine0000 New American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 released to the worldHome > News > New American Classification of Mental Disorders DSM-5 released to the world

| DSM-5 consists of three sections: it is (1) an introductory part with instructions for use and a warning about the forensic psychiatric use of the DSM-5; (2) diagnostic criteria and codes for routine clinical use; and (3) tools and techniques to inform clinical decision making. Main changes:

The severity of the disorder is determined not by IQ, but by the level of adaptive functioning. Speech disorders have entered the new category "social communication disorder", in which some of the syndromes coincide with "autism spectrum disorder". The category "Autism Spectrum Disorders" replaces the DSM-4 diagnoses of autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and an unspecified general developmental disorder, all of which cease to exist as separate diagnoses. ADHD can start later (before 12) and is treated differently in different areas. Learning disorders and movement disorders are organized differently in this chapter and somewhat combined. nine0004

For the diagnosis of schizophrenia, symptoms of the first Schneider rank lose their special weight. One positive symptom is required for a diagnosis to be made.

Bipolar and related disorders are now separated from depressive disorders and placed in a separate category. A clearer definition of mania is given and refinements for mixed episodes are introduced, which lowers the threshold for disorder. Added a residual subcategory ""other"" and a qualifying score for anxiety symptoms.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder added. Chronic depression and dysthymia are combined into one diagnosis, now it is ""persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)"" with a number of clarifying indicators.

|

nine0004

nine0004  Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately. The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders. nine0004

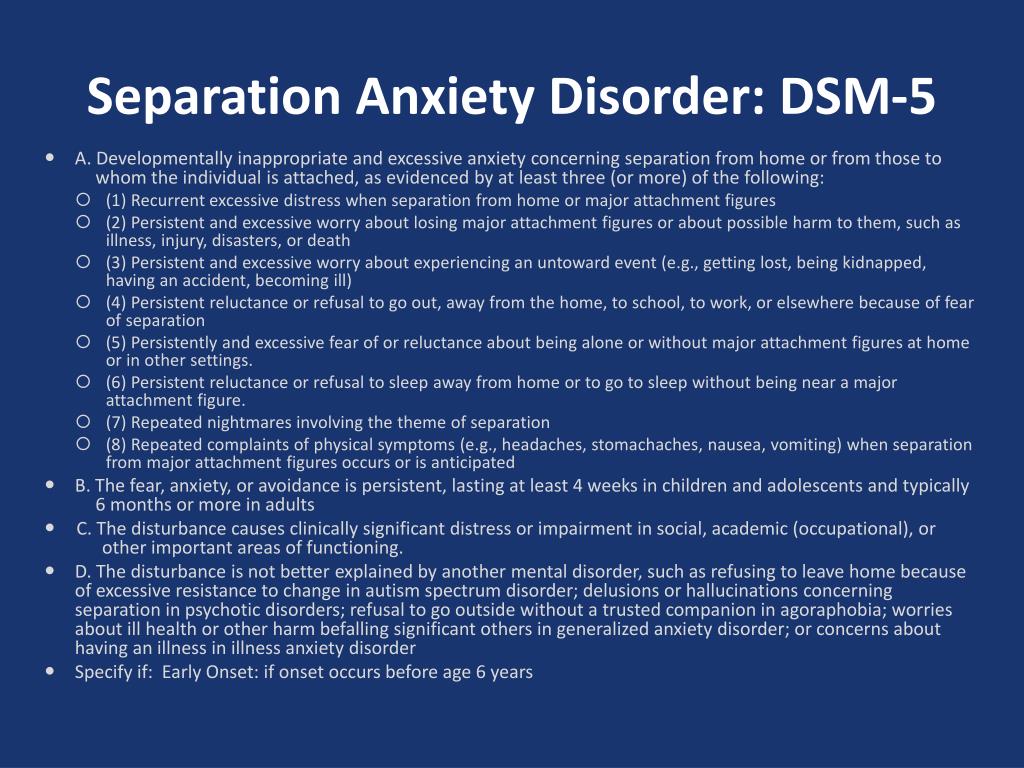

Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately. The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders. nine0004  Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator "mixed manifestations" was introduced. A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. nine(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses. nine0004

Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator "mixed manifestations" was introduced. A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. nine(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses. nine0004  nine0004

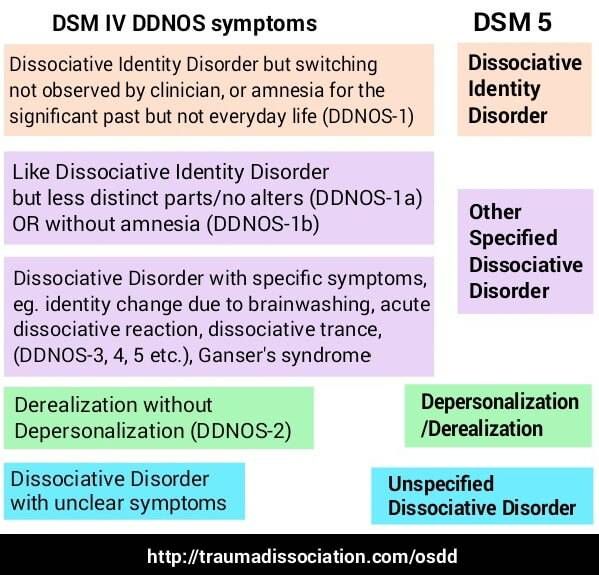

nine0004  Depersonalization and derealization are combined into one disorder. Dissociative fugues have ceased to be a separate diagnosis, and have become a clarifying indicator in ""dissociative amnesia"".

Depersonalization and derealization are combined into one disorder. Dissociative fugues have ceased to be a separate diagnosis, and have become a clarifying indicator in ""dissociative amnesia"".  Anorexia no longer requires amenorrhea and binge eating episodes, although for bulimia nervosa and the new Binge-Eating Disorder category, binge eating episodes must occur at least once a week. nine0004

Anorexia no longer requires amenorrhea and binge eating episodes, although for bulimia nervosa and the new Binge-Eating Disorder category, binge eating episodes must occur at least once a week. nine0004  All disorders are subtyped according to psychological or combined factors, situation, and achievement.

All disorders are subtyped according to psychological or combined factors, situation, and achievement.