Does birth control cause depression

Consumers react to coronavirus crisis, increasingly move online

Study debunks common myth that hormonal contraceptives cause depression, suicide in women

November 9, 2020 | By Kristin Samuelson

- Feinberg School of Medicine

- Mental Health

- Women’s Health

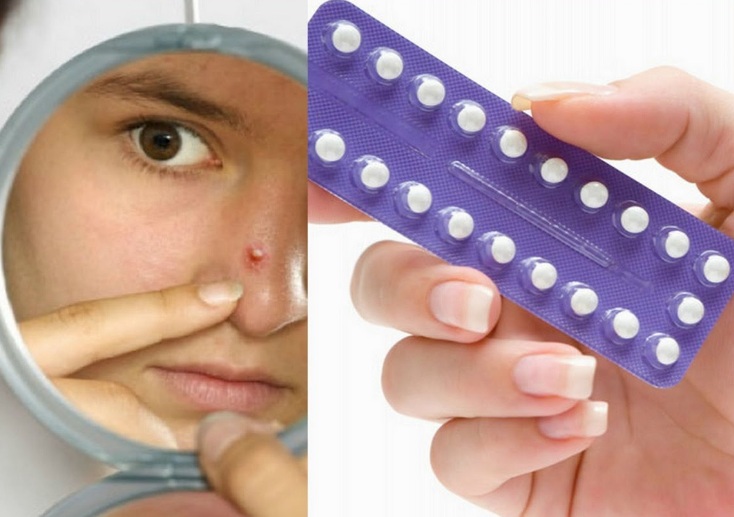

Women who struggle with mental illness often don’t take the most effective birth control methods because they worry the hormones in these contraceptives can trigger depression and suicide, a myth that has been perpetuated by recent studies.

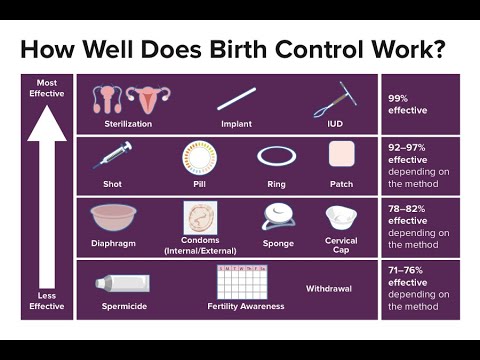

A new Northwestern Medicine study has found hormonal contraceptives — the pill, IUDs, vaginal rings, etc. — do not cause depression, and women should feel free to choose from the wide variety of effective birth control methods available.

“This is a very common concern,” said senior author Dr. Jessica Kiley, chief of general obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and a Northwestern Medicine gynecologist. “For some patients with anxiety disorders, when you discuss a contraceptive’s potential side effect, they get very worried. We’re hoping to encourage women to focus on their contraceptive needs and learn about options that are unlikely to cause depression.”

The study is the first to provide guidance in the official journal of the American Psychiatric Association on the choice of contraceptives for women with depression and other psychiatric disorders. The study is a comprehensive review of published research of contraceptives for women with psychiatric disorders. The authors’ goal is to help women plan pregnancy for when they can manage both their mental and reproductive health. It was published November 10 in the American Journal of Psychiatry.

“When you review the entirety of the literature and ask, ‘Do hormonal contraceptives cause depression?,’ the answer is definitely no,” said corresponding author Dr. Katherine Wisner, the Norman and Helen Asher Professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the director of the Asher Center for the Study and Treatment of Depressive Disorders.

Katherine Wisner, the Norman and Helen Asher Professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences and obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and the director of the Asher Center for the Study and Treatment of Depressive Disorders.

Common concern: Hormones in the pill, IUDs, vaginal rings, etc. cause depression

Debunking the myth

“While contraceptives don’t cause depression, there is an association with depression and contraceptive use,” Kiley said. “But even saying that is controversial because association is not the same as cause, and it isn’t found in all studies. The lack of data on this topic is quite challenging, which is why we were so motivated to conduct this study.”

Clinical studies and randomized placebo-controlled trials of women with psychiatric disorders have reported similar rates of mood symptoms in hormonal contraceptive users compared with nonusers, Wisner said. In some cases, hormonal contraceptives may even help stabilize or reduce the rates of mood symptoms in women with psychiatric disorders, the study found.

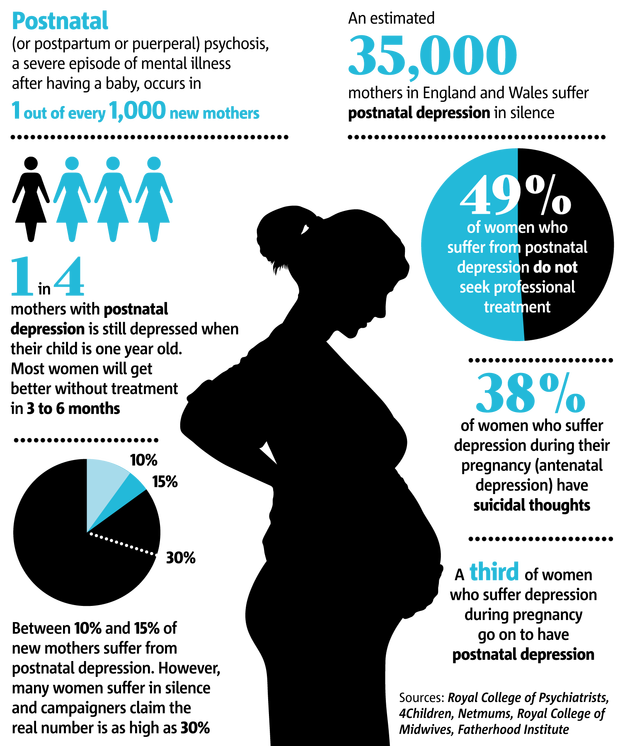

Avoiding unintended pregnancies, which trigger more depression

The mental and physical stress of an unintended pregnancy could trigger a new and recurrent bout of depression, including postpartum depression, Wisner added.

“Women should know they always have access to many types of birth control, regardless of their history or likelihood of mental illness,” Wisner said. “They shouldn’t feel like they’re out there flailing on how to not get pregnant.”

The highest prevalence of mental illness (22.3%) is in women in their prime reproductive years (age 18 to 25), yet psychiatrists don’t typically receive enough training in contraceptive management to properly counsel these women on the choices of birth control for them, the authors said. The study authors hope the findings will lead to better collaboration between gynecologists and psychiatrists, so they can work together to help women decide what contraceptive is best for them.

“Psychiatrists should feel well versed and comfortable talking with patients about their goals for fertility, pregnancy planning and starting a family down the road,” Kiley said. “The default should not be, ‘I just told her to use condoms.’ It should be that there are a lot of safe and effective options out there. We should also develop better communication systems between psychiatrists and gynecologists, who care for the same patients.”

“The default should not be, ‘I just told her to use condoms.’ It should be that there are a lot of safe and effective options out there. We should also develop better communication systems between psychiatrists and gynecologists, who care for the same patients.”

“Contraceptive care should be viewed as preventative health, so women can make active and deliberate decisions about timing of pregnancies. It’s a novel concept to some, though.”

Women should be screened for depression at routine appointments, as is recommended by the American College of Obstetrician and Gynecologists, Wisner said. They also should bring up contraceptive and family-planning questions with any provider, including their psychiatrists.

It is important to get a baseline sense of a woman’s mental health before taking a contraceptive, so her psychiatrist can monitor her symptoms after starting it, Wisner said. This is especially critical for women with bipolar disorder, who have mood fluctuations around their menstrual cycle.

Although interactions between psychotropic drugs and contraceptives are infrequent, doctors need to be aware of important exceptions, such as clozapine (an antipsychotic drug), lamotrigine, valproic acid and carbamazepine (for bipolar disorder and seizures), which can sometimes interfere negatively with certain contraceptives, Wisner said. Additionally, natural compounds such as Echinacea and St. John’s Wort may decrease the effectiveness of hormonal contraceptives.

Other Northwestern authors include Dr. Leanne McCloskey and Dr. Catherine Stika.

For Journalists: view the news release for media contacts

Editor’s Picks

A campus resource that helps first-generation and low-income students succeed at Northwestern

October 27, 2022

Northwestern invites community feedback on new Ryan Field plan

October 28, 2022

Practice the art of looking — at art

October 27, 2022

Never miss a story:

Get the latest stories from Northwestern Now sent directly to your inbox.

Subscribe

What to Know About Birth Control and Depression

Written by Alexandra McCray

Medically Reviewed by Traci C. Johnson, MD on August 17, 2022

In this Article

- Hormonal Birth Control and Depression

- Picking Your Birth Control

- When to Talk to Your Doctor

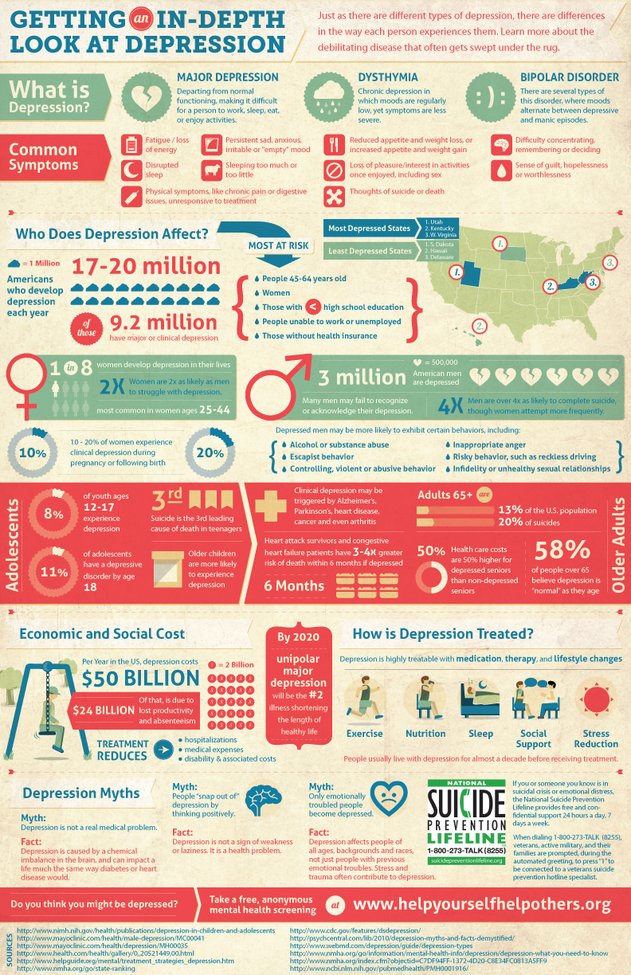

Some women who are on hormonal birth control get mood swings and other emotional side effects. Sometimes the changes may help, such as easing your crankiness or anxiety. But other women report feeling depressed or going through such a severe emotional roller coaster that they quit their hormonal contraceptives.

What’s going on?

Hormonal Birth Control and Depression

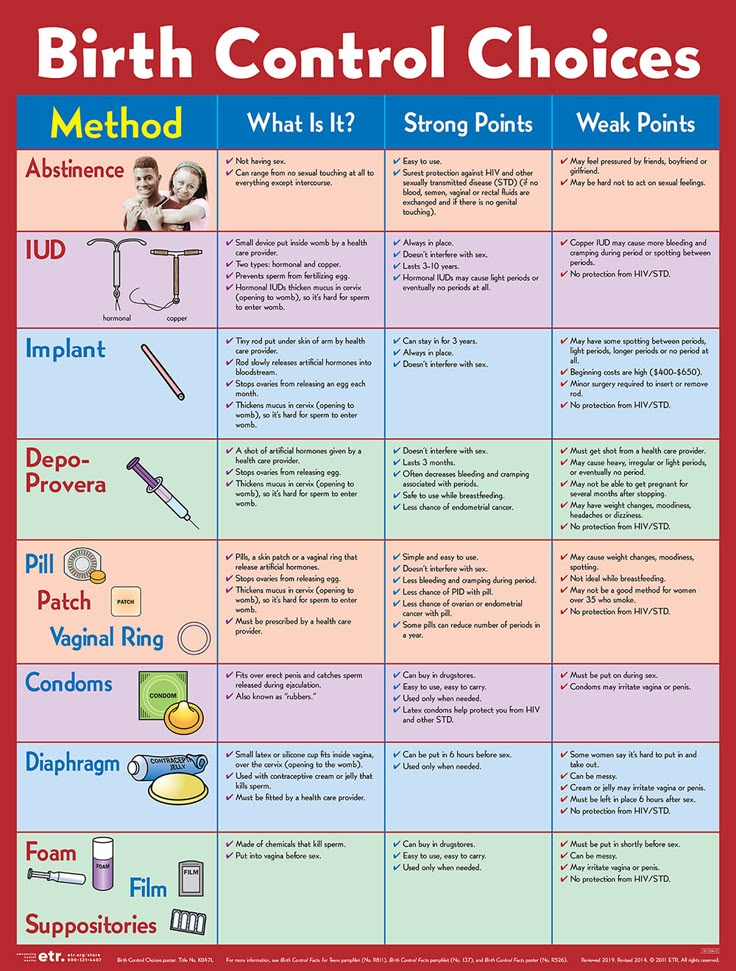

Contraceptives that use hormones to keep you from getting pregnant come in many forms. They include the pill, the mini pill, implant, shot, intrauterine device (IUD), patch, and vaginal ring.

Researchers don’t have enough evidence to say for sure if hormonal birth control causes depression. But most of the information available suggests that the answer is likely a no. Still, researchers can’t rule out that there may be a link between those contraceptives and depression.

But most of the information available suggests that the answer is likely a no. Still, researchers can’t rule out that there may be a link between those contraceptives and depression.

Part of the uncertainty stems from the fact that every woman reacts differently to hormones. Another reason is that studies have turned up conflicting findings.

For example, some research says that women get extra benefits from hormonal birth control, such as fewer depressive symptoms or lessened emotional symptoms from premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

But other studies have found a link between women, especially adolescents, who used hormonal birth control and their rates of depression and antidepressant use. Sixteen-year-olds in one study who took birth control pills cried more and had trouble sleeping.

Researchers think that hormonal contraceptives may have a bigger effect if a woman already has a mood disorder. But more studies are needed.

Picking Your Birth Control

Your choice will depend on things like your lifestyle, ease of use, cost, and when and if you plan to have a baby.

If you’re worried about how hormonal birth control may affect your mood, ask your doctor if you might have other options. They might include:

- Birth control that has fewer androgenic progestins (a type of hormone)

- Continuous combination hormonal contraception. There is a version of the pill that allows you to take a hormone pill every day and not have a period each month.

- Combination hormonal contraceptives you don’t take by mouth. The patch and vaginal ring are examples of this.

- Hormone-free alternatives like a copper intrauterine device, condoms, and diaphragm/cervical cap

When to Talk to Your Doctor

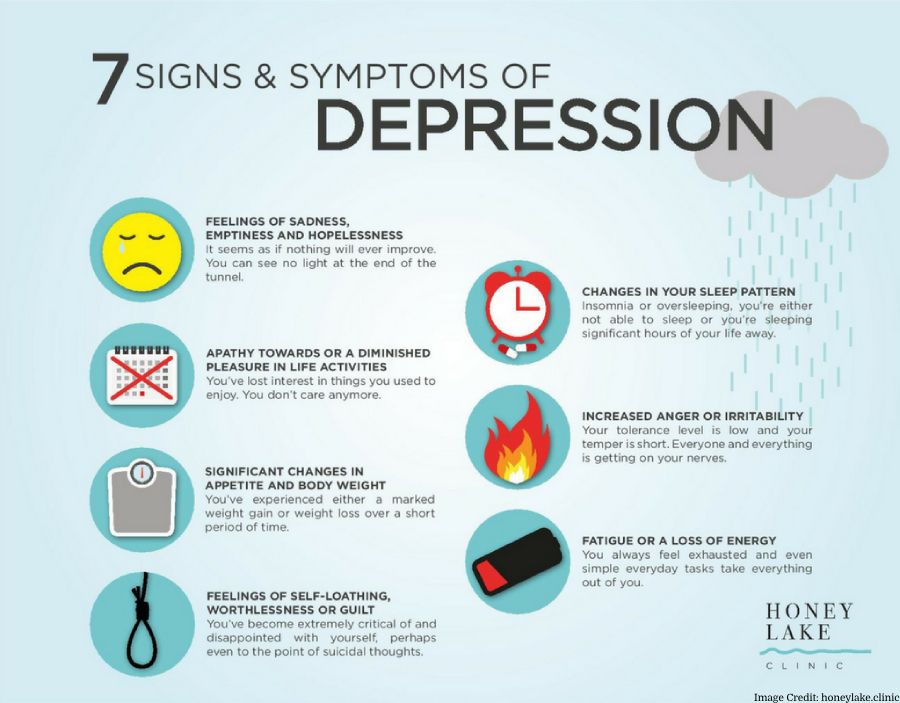

Be alert to any mood swings or changes you have when you take hormonal birth control. Symptoms of possible depression include:

- Having a hard time concentrating or making a decision

- Lack of energy

- Feeling more tired

- Feeling “empty” or hopeless

- Not enjoying your usual hobbies or activities

- Trouble sleeping or sleeping too much

Call your doctor right away if:

- You have any of the above symptoms for more than 2 weeks

- Your symptoms feel more severe than regular mood changes

- Your mood is affecting your work, school, or home

Birth control pills have not been proven to be linked to depression

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you sort things out.

Image copyright, BSIP

Image caption,Some of the side effects of birth control pills have been well known since they were on the market in the 1960s

One scientific study recently postulated an association between birth control pills and risk of depression .

This is not the first study purporting to find unwanted side effects of birth control pills.

But, as Elisabeth Kassin writes, an illiterate interpretation of statistics poses a much greater danger to women's health.

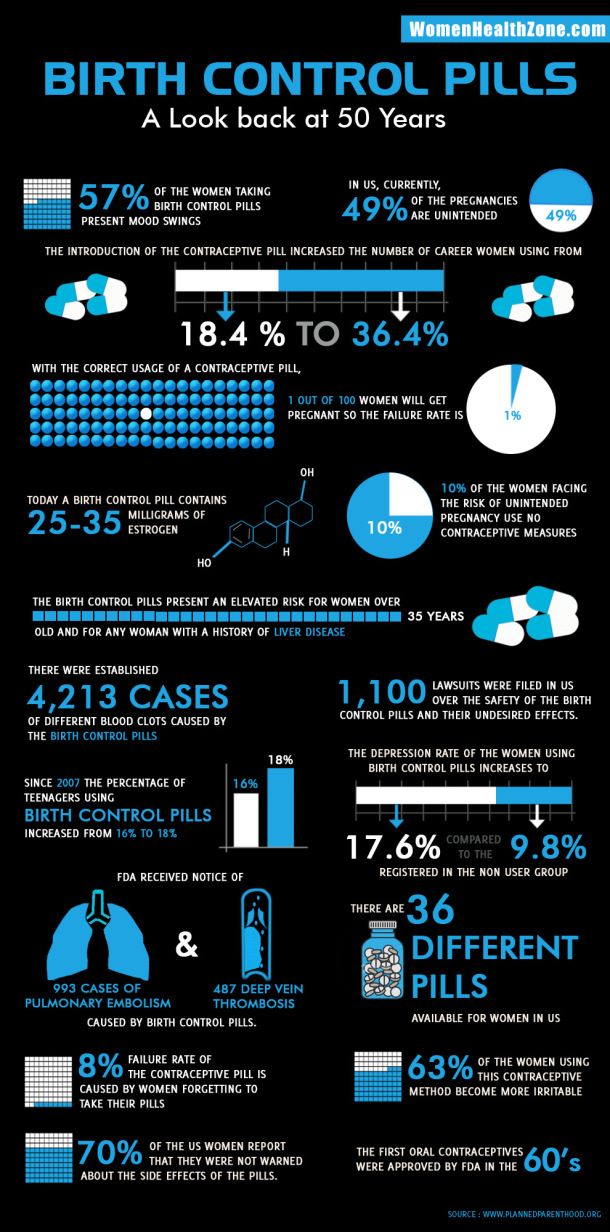

According to the World Health Organization, over 100 million women around the world use combined oral contraceptives, also known as birth control pills.

Some of the side effects of these tablets have been well known since they were introduced to the market in the 1960s. But a recent study allegedly established a link between birth control pills and depression.

Danish scientists studied the medical records of more than a million women aged 15 to 34 who had never suffered from depression in the past.

They found that those who took birth control pills were more likely to be prescribed antidepressants or diagnosed with depression later on by doctors.

The results of the study were reported in the press around the world. "Do you take birth control pills? You are more likely to be depressed: women who take contraceptives are 70% more likely to suffer from depression," one newspaper loudly declared. "Contraceptive pills are associated with depression. Why didn't a scandal erupt?" asked another.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Birth control pill randomized trial impossible

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

However, as Phil Hannaford of the University of Aberdeen points out, the Danish study showed only "a small effect, if any. "

"

Of every 100 women not taking birth control pills, 1.7 were using antidepressants. Among every 100 women taking oral contraceptives, this number is slightly higher - 2.2.

According to Hannaford, this is a very small difference. "The difference is 0.5, which is one woman in every 200," he says.

Although these data indicate a statistical relationship, they do not indicate a causal relationship, as some other factors may be at work in this case.

"For example, some of the women who take birth control pills may have separated from their partners. This, in turn, can lead to depression," he notes.

Such studies are sufficient to suggest a hypothesis, but we should not forget that they do not provide evidence for a causal relationship, adds Phil Hannaford.

This requires a large randomized controlled trial in which one group of women is given the test substance and another is given a placebo.

In this case, this is not possible (and unethical) because women who receive a placebo would think they are taking contraceptives and would not take other steps to prevent conception.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Birth control pills from the 70s

This is not the first time scientists have been talking about the possible side effects of birth control pills.

Rare cases of blood clots, which can be life-threatening, attract the most attention.

But a poor understanding of the degree of risk can lead to undesirable consequences.

Professor Gerd Gigerenzer of the Harding Center for Risk Literacy in Berlin says that “There are many traditions in the UK, including scaring people about the risks associated with birth control pills. lead to thrombosis.

In 1995, the British Medicines Safety Board issued an official warning, citing a study showing third-generation birth control pills "doubled the risk of thrombosis".

"Alarms have been sounded all over the country," says Prof. Gigerenzer.

As a result of this panic, some women stopped taking contraceptives. According to some estimates, this led to an increase in the birth rate by 12,400 babies in 1996 and 13,600 additional abortions.

"This is an example of a lack of risk literacy - not understanding the difference between relative and absolute risk leads to an emotional reaction, which in turn leads to negative consequences for the women themselves," he says.

Image copyright, SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Photo caption,Pregnancy and childbirth lead to thrombosis more often than the birth control pill

What is the absolute risk? And how should women understand it?

The Guardian recently published a film about young women who died of blood clots after using hormonal contraceptives - birth control pills, vaginal rings and patches.

The authors of the film argue that if women knew about the mortality rate, they would stop using hormonal contraceptives. They also state that out of 10,000 women who use vaginal rings, at least a few die.

They also state that out of 10,000 women who use vaginal rings, at least a few die.

"It's not certain that a few out of 10,000 women will die," says Dr Sarah Hardman of the Department of Sexual and Reproductive Health at the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

"It would be more accurate to say that a few out of 10,000 women - between five and 12 - will develop thrombosis. But not all of them will die from this. In fact, only about 1% of women who develop thrombosis die" she says.

"We are talking about the fact that three to 10 out of every million women die due to blood clots resulting from the use of hormonal contraception," - emphasizes Hardman.

For women of reproductive age who do not use hormonal contraceptives, only two out of 10,000 women per year face a fatal outcome.

But, of course, not using birth control pills to avoid thrombosis increases the risk of pregnancy. And pregnancy, in turn, in itself dramatically increases the risk of thrombosis.

"Among pregnant women, it's about 29 per 10,000," says Dr. Hardman.

"In the first few weeks after giving birth, 300 to 400 out of 10,000 women are at risk of developing blood clots," she continues.

In other words, pregnancy and childbirth are much more likely to cause thrombosis than the birth control pill.

In addition, the birth control pill is very effective in preventing pregnancy. Only the intrauterine device, implants or sterilization are more effective.

Swallowing tablets. How are birth control pills related to depression?

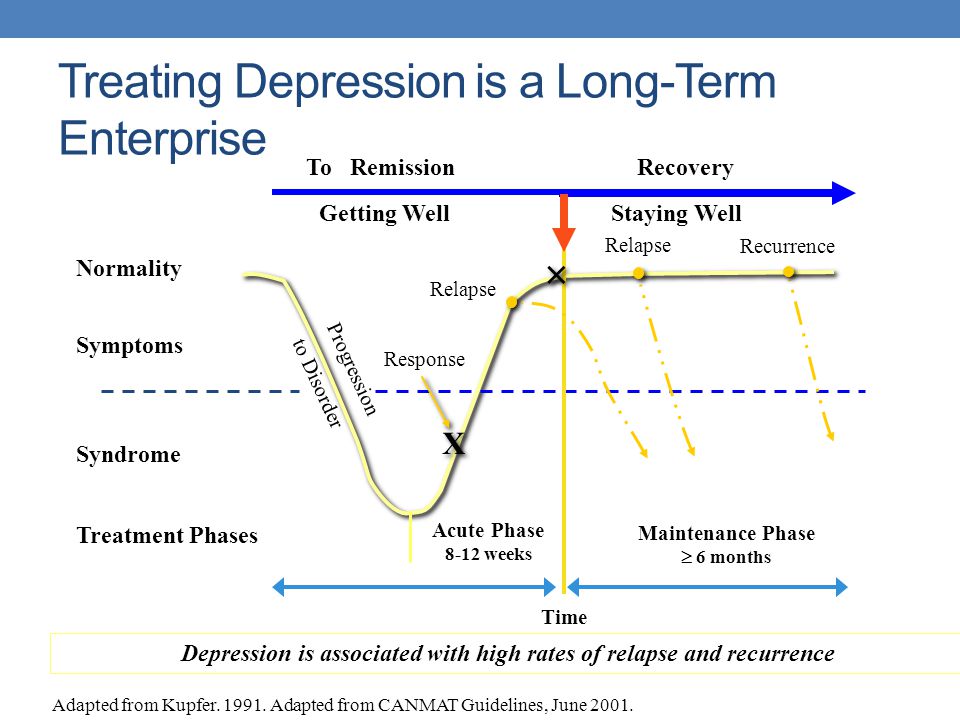

Treatment

MedicineCondomsSex

29 November 2018

Independent0125 The serious mental illness side effects of oral contraceptives have been highlighted in a new documentary by Olivia Petter for the BBC. AIDS.CENTER publishes the translation.

Birth control pills have been controversial since they were introduced in the UK in 1961.

Despite existing research linking their use to breast cancer, blood clots, decreased libido and weight gain, they remain the most popular form of contraception, with over a hundred million women worldwide taking them.

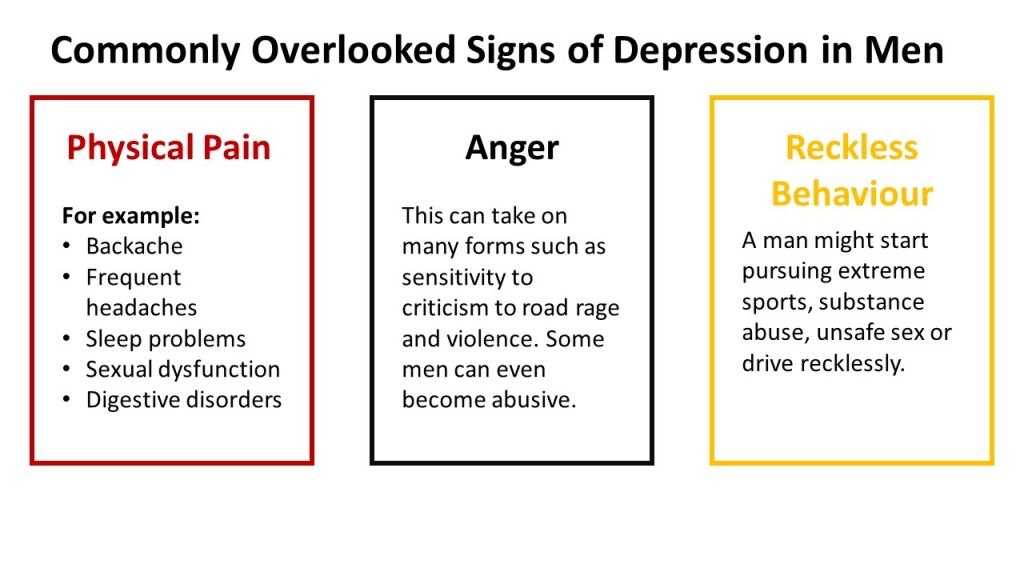

At the same time, a large body of research shows a strong correlation between the use of birth control pills and the development of psychiatric disorders, and a new BBC Two documentary sheds light on the severity of the problem, showing how taking them has driven some women to depression and suicidal thoughts.

Contained in pills (both contraceptive and mini-pill) hormone - progesterone - scientists associate with the development of mental complications: depression, anxiety, mood deterioration.

However, researchers have yet to find an ethical way to prove causation, because such studies would have to include a control group taking a placebo, which can lead to unwanted pregnancies, which in turn raises many moral complexities.

The BBC collaborative team conducted a survey that read: "Contraceptive pills: how safe are they?" The results showed that one in four women who took the pill reported a negative impact on their mental health.

Related

Prevention

Spit in the frog's mouth, eat the bee: A history of contraception since ancient times

- Condoms Sex

One of these women is Danielle, she is 31 years old. In an episode titled "Horizon," she recalls how the side effects were "terrible and debilitating," clarifying that she never had any mental health problems before starting birth control. “I went from normal to suicidal in just 6 months,” she adds.

Grazia Editor-in-Chief Vicky Spratt had a similar experience and recalls how her mental health began to deteriorate soon after starting birth control when she was 14 years old. This led her to depression and regular panic attacks.

"I remember thinking, 'If this is what the rest of my life is going to be like, I don't want to live like this,'" Spratt, 30, says in the documentary.

Spratt is now scheduled to take antidepressants and undergo cognitive behavioral therapy, but she explains that no doctor has linked her worsening mental state to birth control.

After extensive research on the Internet, she found several research materials linking depression to birth control. Vicki decided to take a break from her appointment to see if her condition would improve. Bottom line: She began to feel better “in just a few weeks.”

In the BBC story, Spratt talks to Copenhagen professor Øyvind Lidegaard, who has access to a unique database of medical records—in Denmark, each patient's data is entered into a centralized system. This allowed him to observe the recordings of more than a million Danish women aged 15 to 34 over a period of sixteen years and to conduct two studies on the relationship between mental health and hormonal contraception.

related

Prevention

“There is no sex in the USSR”: A review of Soviet condoms

- HIVCondomsPrevention

One study showed that women taking contraceptives, whether combined drugs or drugs based on progesterone alone, are more likely to be prescribed antidepressants than those who do not take birth control. The difference is especially noticeable among women aged 15 to 19 who take combination drugs.

The difference is especially noticeable among women aged 15 to 19 who take combination drugs.

Another study links hormonal contraceptive use to suicide attempts and suicide. Lidegard's research is supported by a separate study from Sweden covering over 800,000 women, which was published in March 2018.

Despite the number of women experiencing mental health problems due to birth control, Spratt notes that too little has been done in the UK to combat this problem. This is due to a lack of data and the apparent reluctance of the UK National Health Service (NHS) to take action to correct the situation.

She has been studying the link between the birth control pill and mental illness for almost two years and after several inquiries, she found out that this is not an area where the NHS has any data at all.

This means that the NHS does not monitor women who take oral contraceptives and are treated for mental disorders at the same time, at least not to the extent that the Danish medical system does.

The paper also concludes that women may not be fully informed about these side effects before starting treatment - without any mention of depression or anxiety disorders. Instead, leaflets distributed to women at sexual health clinics only mention "mood changes" as a possible side effect.

“What does that even mean? It could mean anything,” Spratt says in an interview with The Independent. “I think the NHS has become attached to 'mood swings' because they're worried that stopping birth control could cause a huge spike in unwanted pregnancies. It surprises me that despite the known link between progesterone and depression, the NHS doesn't even look into it and as a result we don't know anything about how many women in the UK experience these side effects."

related

Treatment

Will this help? How safe is sex with antiseptics

- HIVSTI Sex

Spratt describes the seeming reluctance as "weird", adding that this is why she chose to take part in the BBC documentary.