Depression loss of feelings

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Alexithymia: an emotional gap hiding under the mask of normality

Alexithymia is a psychological state of a person in which a person, having lost the ability to determine and display his own emotions, is forced to try to look normal in the eyes of others. The psychiatrist Saito Satoru talks about this disorder using examples from his own practice, as well as the example of the heroes of the novel "Man of the convenience store" ( Kombini ningen , by Murata Sayaka), awarded the Akutagawa Prize for 2016.

In psychiatry there is a term "alexithymia". It consists of the negative prefix "ἀ" and two stems: "λέξις" (word) and "θυμός" (feelings, emotions). This term describes a psychological state where a person is unable to evaluate and describe their own emotions. In order to have a holistic view of one's own life, the individual must be aware of and distinguish what he feels. However, there are people who are incapable of this - they do not understand in what situations this or that emotion arises in them. Features of alexithymia appear in such people in those moments when they are overcome by anger, sadness, or any other strong feeling that they are not able to define and express.

It consists of the negative prefix "ἀ" and two stems: "λέξις" (word) and "θυμός" (feelings, emotions). This term describes a psychological state where a person is unable to evaluate and describe their own emotions. In order to have a holistic view of one's own life, the individual must be aware of and distinguish what he feels. However, there are people who are incapable of this - they do not understand in what situations this or that emotion arises in them. Features of alexithymia appear in such people in those moments when they are overcome by anger, sadness, or any other strong feeling that they are not able to define and express.

In fact, with the exception of babies, there are practically no people in modern society who would cry or scream, completely without restraint. It is understood that an adult member of society should control himself and not show such primitive emotions outwardly. And if he is not able to restrain himself, then he needs treatment.

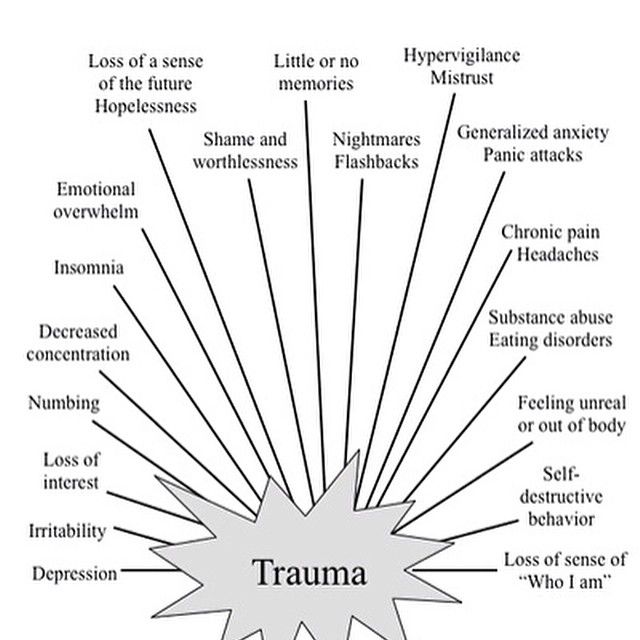

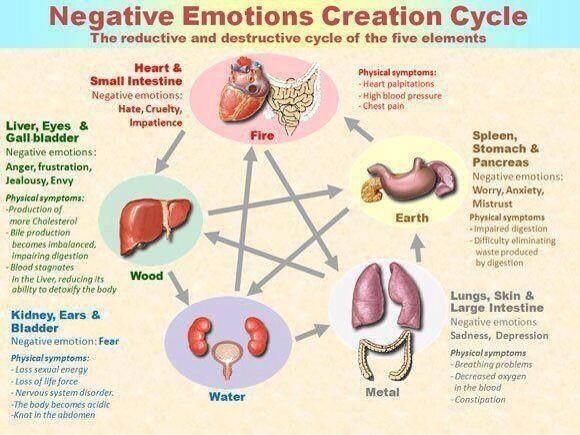

Young people striving to conform to the notions of "normality" learn from the older generation to suppress the expression of emotions. Over time, some of them lose the ability to recognize their own feelings. Suppressed anger, sadness become the cause of psychosomatic diseases and hypochondriacal disorders. Hypochondriacs are characterized by a clear manifestation of somatic symptoms in the absence of any significant pathological abnormalities. As a result of an anxious set and constant concern about health, the functions of the heart, gastrointestinal tract and other autonomically innervated systems can be disturbed. And this, in turn, leads to the development of arterial hypertension, peptic ulcer, etc. That is why hypochondria is considered a psychosomatic disease.

Over time, some of them lose the ability to recognize their own feelings. Suppressed anger, sadness become the cause of psychosomatic diseases and hypochondriacal disorders. Hypochondriacs are characterized by a clear manifestation of somatic symptoms in the absence of any significant pathological abnormalities. As a result of an anxious set and constant concern about health, the functions of the heart, gastrointestinal tract and other autonomically innervated systems can be disturbed. And this, in turn, leads to the development of arterial hypertension, peptic ulcer, etc. That is why hypochondria is considered a psychosomatic disease.

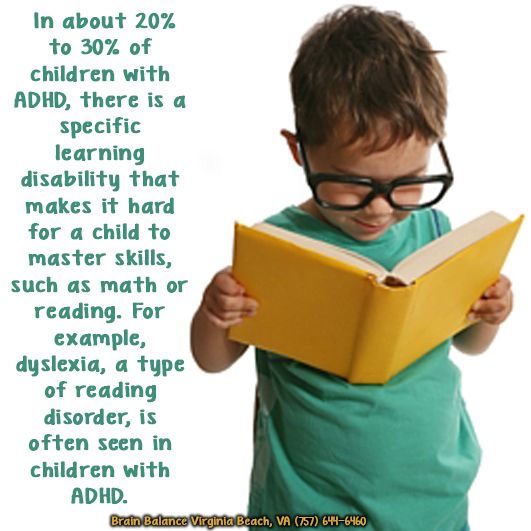

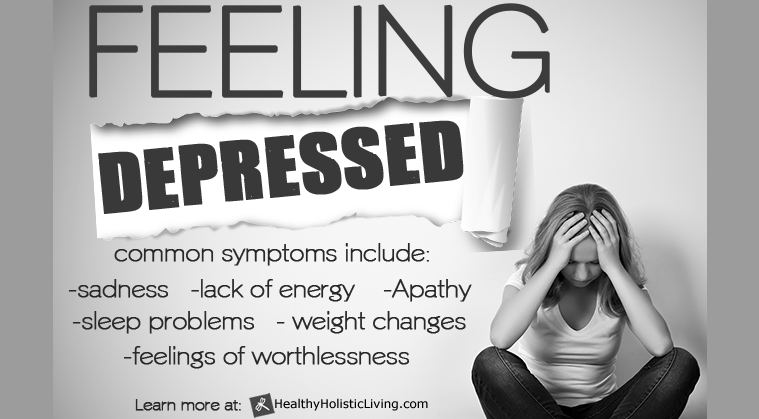

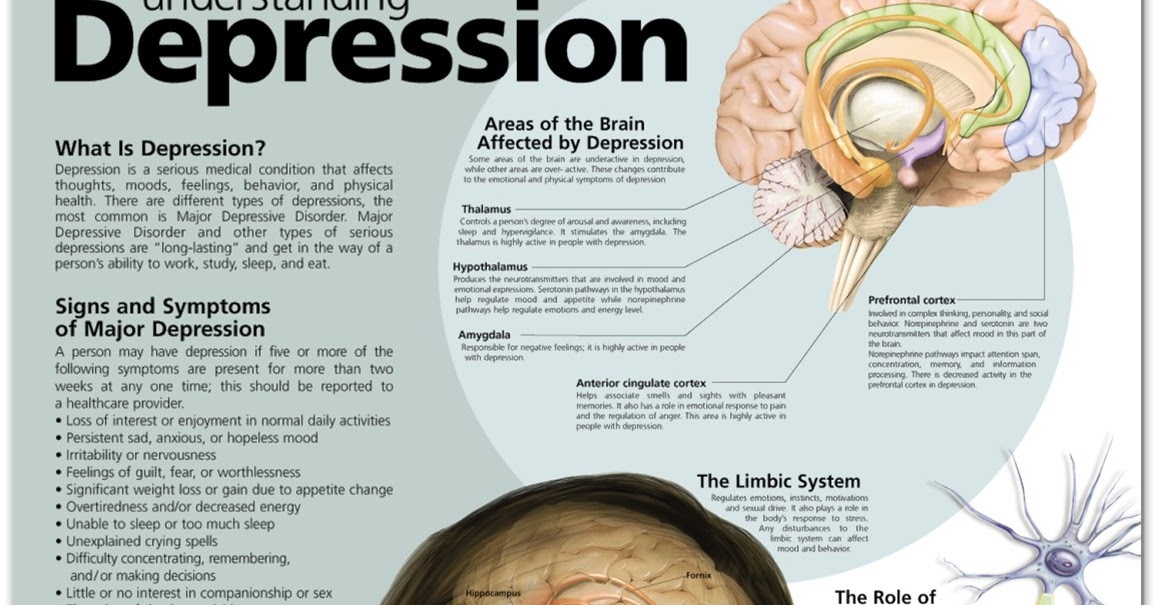

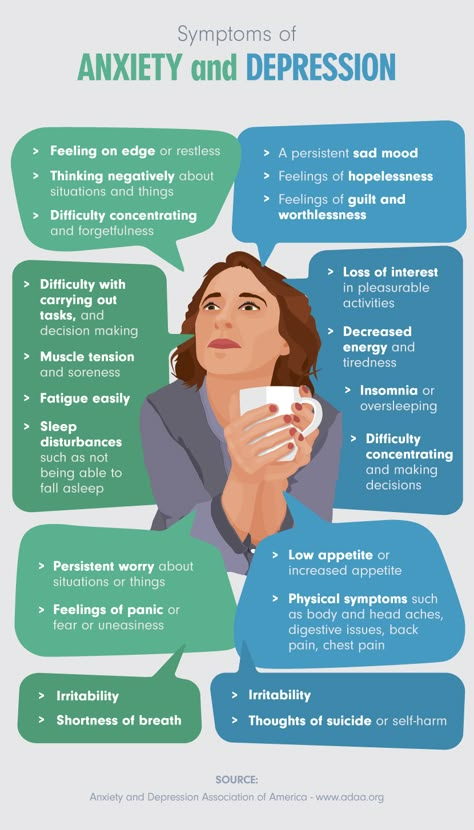

However, with alexithymia, not only negative emotions are blurred, but also positive ones - a person is not able to experience such feelings as joy or inspiration. The loss of the ability to experience pleasure is called anhedonia. This disorder is characterized by a loss of motivation for activities that the individual enjoyed in the past. The development of anhedonia is an important indicator in the diagnosis of pathological depression.

Under the guise of normality

I have my own psychiatric practice in Tokyo, and I encounter people suffering from depression and hypochondria on a daily basis at work. During the first meeting, most of them show no signs of suffering or despair. And I have to pull off their mask of normality, under which they hide their illness, which needs treatment.

Cover of "Convenience Store Man" (illustration courtesy of Bungei Shunju)

I thought about this when I read the novel "Convenience Store Man" for which Murata Sayaka recently won the Akutagawa Prize. Indeed, in this story we are talking about a person suffering from alexithymia. The heroine, a woman named Kokura Keiko, worked for 18 years as a saleswoman in the same minimarket ( combi) - it is on her behalf that the story is being told. She made it a rule never to show her feelings or express judgment. Instead, she has created a "patchwork personality" by copying the behavior and adopting the habits and mannerisms of the women around her (mostly work colleagues), whom she considers correct and admires for their style. This effective and convenient strategy allows it to adapt to its own environment. The moment she arrives at work shortly before the start of her shift and changes into her work uniform, Keiko becomes a function, a convenience store man. Now all that is required of her is to perform the prescribed duties for the appointed time, using the skills she has learned and the judgments she has borrowed appropriate to the occasion. The school years of the heroine passed under the endless complaints of parents who were dissatisfied with their individualistic daughter, and constant pressure from school teachers. As an adult, she is grateful for the opportunity to hide her identity under a faceless uniform.

This effective and convenient strategy allows it to adapt to its own environment. The moment she arrives at work shortly before the start of her shift and changes into her work uniform, Keiko becomes a function, a convenience store man. Now all that is required of her is to perform the prescribed duties for the appointed time, using the skills she has learned and the judgments she has borrowed appropriate to the occasion. The school years of the heroine passed under the endless complaints of parents who were dissatisfied with their individualistic daughter, and constant pressure from school teachers. As an adult, she is grateful for the opportunity to hide her identity under a faceless uniform.

However, when Keiko suddenly realizes that those around her feel sorry for her - a single woman who worked as a saleswoman in a minimarket for 18 consecutive years - she becomes extremely worried. At this moment, she meets a new minimarket employee, a man who is the complete opposite of her. He is convinced that society has turned its back on him and that everyone is hounding and persecuting him. So he doesn't even try to appear normal, and very soon he is fired from the convenience store. Keiko invites him to stay with her. At first glance, it seems that they are a very harmonious couple, but their relationship is built on a cold calculation. For a workaholic Keiko, this is an opportunity to create the appearance of a romantic relationship; for a lazy man, life with Keiko is an excellent hiding place from the injustice of a cruel world. But their life together upsets the fragile mental balance that Keiko has maintained and strengthened in herself throughout all these eighteen years.

He is convinced that society has turned its back on him and that everyone is hounding and persecuting him. So he doesn't even try to appear normal, and very soon he is fired from the convenience store. Keiko invites him to stay with her. At first glance, it seems that they are a very harmonious couple, but their relationship is built on a cold calculation. For a workaholic Keiko, this is an opportunity to create the appearance of a romantic relationship; for a lazy man, life with Keiko is an excellent hiding place from the injustice of a cruel world. But their life together upsets the fragile mental balance that Keiko has maintained and strengthened in herself throughout all these eighteen years.

The caustic remarks of her roommate expose her spiritual emptiness, the gaping emptiness of her personal space, which Keiko had refused to notice for so many years. Refusal, denial is a primitive psychological defense mechanism, a subconscious attempt to ignore the problem, the existence of which is obvious to any outside observer. And the one who denies the obvious looks infantile and eccentric in the eyes of others.

And the one who denies the obvious looks infantile and eccentric in the eyes of others.

Realizing the hopelessness of his situation, Keiko quits his job and ceases to be a "man of the convenience store". She has no choice but to lie all day under the covers, on the futon, which she spread out inside the closet. I call this phase "bed addiction" and I believe that it is the starting point for the development of other types of addiction: from drug or alcohol addiction to sexual addiction. In fact, both addictive behavior and "show normality" are desperate attempts to get out of the quicksands of the emotional vacuum.

This story has a somewhat happy ending - Keiko starts working at the convenience store again. But I do not think that this will make many readers laugh too much, as they notice the connection between excessive obsession with work and the meaninglessness of the heroine's personal space.

Refusal to feel

"Bed addiction" is essentially a regression to the so-called "primal sleep" - a dream-like state characteristic of infants. This is exactly the state that heroin addicts so passionately desire to achieve. A similar process of regression is also experienced by recluses.0003 hikikomori . Every day this quagmire sucks in hikikomori more and more, and getting them out of it is not an easy task.

This is exactly the state that heroin addicts so passionately desire to achieve. A similar process of regression is also experienced by recluses.0003 hikikomori . Every day this quagmire sucks in hikikomori more and more, and getting them out of it is not an easy task.

Here it is important to pay attention to one point. A baby who falls asleep while nursing and wakes up to find that he has been taken from his mother's breast will feel restless, angry, flushed and crying.

Older babies (between one and one and a half years of age) also live in a world of basic emotions such as anger, anxiety, depression or sadness. But adults hikikomori are deaf to these emotions. At first they themselves refuse to feel anything, and then they simply lose this ability and fall into a state of alexithymia.

Break free from the spell of "normality"

Such people sometimes come to my clinic for help, mistaking their condition for depression. For example, a housewife came to me who told me that after graduating from university she got a job at a firm right away, but worked for only a year, because office work seemed boring to her. She then found a part-time job at a sadomasochistic (SM) club, a place she liked so much that she worked there for four years. Shortly before she turned thirty, she resigned from the club, judging that sooner or later she would have to do it anyway. Some time later, after an active search for a suitable party ( konkatsu ) she got married, had a baby, and began to lead a "normal" life as a housewife. And then she suddenly found that she spends most of the day in bed or in close proximity to it.

She then found a part-time job at a sadomasochistic (SM) club, a place she liked so much that she worked there for four years. Shortly before she turned thirty, she resigned from the club, judging that sooner or later she would have to do it anyway. Some time later, after an active search for a suitable party ( konkatsu ) she got married, had a baby, and began to lead a "normal" life as a housewife. And then she suddenly found that she spends most of the day in bed or in close proximity to it.

Her husband - a typical sissy, who also suffers from atopic dermatitis - quickly realized that his wife would not take care of him to the same extent as his mother did, and divorced her. At the time of her visit to me, about a month had passed since the divorce.

I think some of my colleagues would have diagnosed this patient with depression or adjustment disorder and would have given her antidepressants. But I noticed how strong her desire to be, or at least seem normal. It was it that made her suppress her individuality and doom herself to life in a world that causes nothing but boredom in her.

It was it that made her suppress her individuality and doom herself to life in a world that causes nothing but boredom in her.

Daily work in the SM club was fraught with danger, but at the same time excited her – the idea that she was working in a “non-standard”, “abnormal” job served as a strong source of emotional excitement. Thus, "normality" is just an illusion, an ideal that can be different for different people.

My patient says that she is already thirty-five, the figure is no longer the same, and that "what was in the past cannot be returned." I do not dispute this point of view. But whether she returns to work at the SM club or not, I think she needs to remember and rethink the strong, exciting feelings that she experienced while working at a job she loved. My task is to return to this woman the ability to feel strong emotions, restoring her connection with her own eroticism. I have to convince her that she doesn't need to hide behind a mask of normality.

Title illustration: Design Pics/AFLO

(Japanese article published November 18, 2016)

NTSPZ.

‹‹Depression and depersonalization››

‹‹Depression and depersonalization›› The allocation of this section to a separate chapter is due to the following reasons: depressive-depersonalization syndrome is much worse than other depressive syndromes; its recognition is fraught with certain difficulties!. and it is relatively often incorrectly qualified: errors and difficulties are also encountered in determining its nosological affiliation. In addition, in recent years there have been almost no special studies of depressive-depersonalization states.

As noted above, a thorough psychopathological examination of patients with severe melancholic syndrome almost always reveals elements of depersonalization in them: anaesthesia dolorosa psychica, less often somatopsychic depersonalization (lack of sleep, hunger, satiety and etc.). Therefore, we referred to the depressive-depersonalization syndrome only those cases when depersonalization (A detailed description of the depersonalization symptoms of tics is given in Chapter 8. ) occupied a leading place in the psychopathological structure of the depressive syndrome, displacing or, rather, blocking the affects of vital melancholy and anxiety, and manifested itself in the form of autopsychic and somatopsychic experiences, as well as in violation of the sense of time. The following is the case history of such a patient.

) occupied a leading place in the psychopathological structure of the depressive syndrome, displacing or, rather, blocking the affects of vital melancholy and anxiety, and manifested itself in the form of autopsychic and somatopsychic experiences, as well as in violation of the sense of time. The following is the case history of such a patient.

Observation 3. Patient L., born in 1899. He does not know about cases of mental illness in his family, his father died early, he grew up and developed normally. He graduated from high school, financial courses, worked as an accountant. Was married twice.

By nature soft, sociable, cheerful, but at the same time impressionable, suspicious, anxious. At the age of 13, discharge from the urethra appeared; thought he was ill

gonorrhea, was in a depressed state for several months, suicidal thoughts arose. After that, for many years he feared the consequences of a venereal disease. In childhood, frequent sore throats. In 1945, an increase in blood pressure was discovered, in 1954-1957. and in May 1958 suffered a myocardial infarction, in September 1958 - dynamic cerebrovascular accident. He died in 1965 after the 4th myocardial infarction.

In childhood, frequent sore throats. In 1945, an increase in blood pressure was discovered, in 1954-1957. and in May 1958 suffered a myocardial infarction, in September 1958 - dynamic cerebrovascular accident. He died in 1965 after the 4th myocardial infarction.

He suffered the first pronounced depressive phase in 1945 at the age of 46 after troubles at work: being an auditor, he did not find a major theft in one of the institutions inspected. There were insomnia, anxiety, fears that he would be put on trial, then his mood dropped sharply. The disease was characterized by an anxiety-depressive syndrome with pronounced motor restlessness, melancholy, suicidal thoughts, auto- and somatopsychic depersonalization phenomena. The phase lasted about 1.5 years, ending after a course of ECT. After being discharged, he returned to work, feeling good. The next depressive state arose on May - June 1958 following a myocardial infarction in May. At first, anxiety and insomnia appeared, then — melancholy, suicidal thoughts; was hospitalized. The condition was characterized by depressive-depersonalization syndrome : mood was lowered, there were anxiety, massive depersonalization experiences — loss of feelings of attachment to loved ones, decrease in tactile, pain and olfactory sensitivity, feeling that the passage of time had drastically slowed down.

At first, anxiety and insomnia appeared, then — melancholy, suicidal thoughts; was hospitalized. The condition was characterized by depressive-depersonalization syndrome : mood was lowered, there were anxiety, massive depersonalization experiences — loss of feelings of attachment to loved ones, decrease in tactile, pain and olfactory sensitivity, feeling that the passage of time had drastically slowed down.

Medical treatment was ineffective. Since January 1959 some improvement spontaneously occurred: daily fluctuations of mood appeared, melancholy and anxiety decreased. In May, ECT was started (11 electric shocks), psychopathological symptoms disappeared completely.

After l .5 years of a full-fledged intermission, in December 1960 a depressive phase began, similar to the previous one in terms of symptoms and course, and lasting 18 months. From March 1961 years old was treated with tofranil (up to 575 mg per day), but the improvement was insignificant, and ECT was started in June. After 2 sessions of ECT, the patient recovered completely and was discharged home. 1-2 weeks ate was in a hypomanic state after discharge.

After 2 sessions of ECT, the patient recovered completely and was discharged home. 1-2 weeks ate was in a hypomanic state after discharge.

Intermission lasted about l .5 years. The last phase began in November 1962 with anxiety and insomnia. Then the mood dropped sharply, melancholy appeared, and depersonalization phenomena quickly began to grow. January 25 1963, the patient was hospitalized.

Mental state: slow, facial expressions are poor, mournful, speech is somewhat slowed down, voice is muffled, poorly modulated. The mood is clearly lowered, but he does not feel longing, since "all feelings have become dull, even longing and pain." Experiencing internal anxiety: "as if something should happen, although I myself know that nothing could be worse." Complains of "complete atrophy of the senses", even the hospitalization of his wife in the Cancer Institute is not caused a commotion, "all human attachments were lost. " The whole world seems to have moved away, it is perceived as dull, pale, "as if through a cloudy glass." The feelings of sleep, hunger, satiety were completely lost, the urge to defecate and urinate disappeared. Does not feel the taste of food and odors. The sense of touch was disturbed: “an insulating layer appeared between the hand and the object, objects are not tactile, the same layer exists between the leg and the floor”). The pain is felt blunted, “the skin does not seem to be its own, it tightens like a rubber shirt”, “pads appeared under the skin, the body became wooden, it feels nothing”, “time has stopped”, and he himself has become “immortal”. He understands that from the point of view of the laws of nature, it seems ; ridiculous, but it is a fact, and he is "doomed to eternal torment." “Even when the earth disappears and the solar system disintegrates, I will exist and suffer forever.”

" The whole world seems to have moved away, it is perceived as dull, pale, "as if through a cloudy glass." The feelings of sleep, hunger, satiety were completely lost, the urge to defecate and urinate disappeared. Does not feel the taste of food and odors. The sense of touch was disturbed: “an insulating layer appeared between the hand and the object, objects are not tactile, the same layer exists between the leg and the floor”). The pain is felt blunted, “the skin does not seem to be its own, it tightens like a rubber shirt”, “pads appeared under the skin, the body became wooden, it feels nothing”, “time has stopped”, and he himself has become “immortal”. He understands that from the point of view of the laws of nature, it seems ; ridiculous, but it is a fact, and he is "doomed to eternal torment." “Even when the earth disappears and the solar system disintegrates, I will exist and suffer forever.”

With a sad smile, he says that the doctors suspect he has depression, he even thinks it's funny to listen to it. He has "gonorrhea, the brain ... gonococci have flooded the entire brain, and the head has become empty, without feelings and thoughts, the lining under the skin also consists of gonococci, and all the insides are corroded and have long disappeared." This explains the lack of a sense of saturation (“everything falls into the void”), January 19At the age of 63, treatment with chloracizin up to 200 mg and a day was started, then, due to the lack of effect, it was gradually replaced with melipramine. During this period, when melipramine was combined with chloracizin, there was an improvement: by the evening the mood became less depressed, began to smell, there was a partial criticism of the ideas of "immortality". However, later on, when treated with high doses of melipramine alone, the condition worsened again. ECT had to be abandoned after 4 shocks due to a medical condition, and large doses of niamide (1000 mg parenteral n) only exacerbated the symptoms.

He has "gonorrhea, the brain ... gonococci have flooded the entire brain, and the head has become empty, without feelings and thoughts, the lining under the skin also consists of gonococci, and all the insides are corroded and have long disappeared." This explains the lack of a sense of saturation (“everything falls into the void”), January 19At the age of 63, treatment with chloracizin up to 200 mg and a day was started, then, due to the lack of effect, it was gradually replaced with melipramine. During this period, when melipramine was combined with chloracizin, there was an improvement: by the evening the mood became less depressed, began to smell, there was a partial criticism of the ideas of "immortality". However, later on, when treated with high doses of melipramine alone, the condition worsened again. ECT had to be abandoned after 4 shocks due to a medical condition, and large doses of niamide (1000 mg parenteral n) only exacerbated the symptoms.

The newly started treatment with meliprimine (up to 450 mg) did not lead to an effect, and only after adding 90 mg of chloracizin to it, the patient's condition began to gradually improve: mood began to level off in the evening, manifestations of somatopsychic depersonalization decreased, then the sense of time was partially restored, “time began to move, although still slowly”, at the same time the thoughts of “immortality” disappeared and criticism of them appeared. Then he began to be critical of the ideas of contracting gonorrhea, admitting that he had "depression, like other patients who can be cured." There was a feeling of satiety, hunger, sleep, the mood completely leveled off. At the end of December he was discharged, a full remission continued until the death of the patient, which followed at the beginning of 1965 years after myocardial infarction.

Then he began to be critical of the ideas of contracting gonorrhea, admitting that he had "depression, like other patients who can be cured." There was a feeling of satiety, hunger, sleep, the mood completely leveled off. At the end of December he was discharged, a full remission continued until the death of the patient, which followed at the beginning of 1965 years after myocardial infarction.

In the case of patient L., despite the atypicality of symptoms, the diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis is based on the phase course of psychosis and the usefulness of the intermission, despite the long duration of the disease and the patient's advanced age. All attacks of the disease are characterized by a distinct affective component, and after one of them a hypomanic state arose.

The fact that psychosis attacks are based on affective disorders is confirmed by a comparative assessment of the phases, the sequence of the development of symptoms and the nature of its regression: transferred to 1945, the attack was characterized by an anxiety-depressive syndrome with ideas of guilt, combined with fear of punishment. In addition, there were pronounced depersonalization phenomena. In subsequent attacks, depersonalization increased, although even in the last phase, both in the statements and in the facial expressions of the patient, a depressive mood was clearly defined. All phases began with anxiety, then melancholy quickly increased and depersonalization appeared. Along the sea, increased depersonalization smoothed out the sharpness of melancholy and ideas of infection with gonorrhea and "immortality". These delusional statements are based on the interpretation of the severe depersonalization sensations described by Kotard, which is confirmed by their regression: the ideas of immortality began to decrease after the sense of time began to recover, but as tactile sensitivity was restored and a feeling of fullness appeared, the patient’s statements about “gonococcal pads” began to disappear. under the skin, that the insides are rotten. Thus, the psychopathological symptoms of seizures are based on melancholy, anxiety and depersonalization.

In addition, there were pronounced depersonalization phenomena. In subsequent attacks, depersonalization increased, although even in the last phase, both in the statements and in the facial expressions of the patient, a depressive mood was clearly defined. All phases began with anxiety, then melancholy quickly increased and depersonalization appeared. Along the sea, increased depersonalization smoothed out the sharpness of melancholy and ideas of infection with gonorrhea and "immortality". These delusional statements are based on the interpretation of the severe depersonalization sensations described by Kotard, which is confirmed by their regression: the ideas of immortality began to decrease after the sense of time began to recover, but as tactile sensitivity was restored and a feeling of fullness appeared, the patient’s statements about “gonococcal pads” began to disappear. under the skin, that the insides are rotten. Thus, the psychopathological symptoms of seizures are based on melancholy, anxiety and depersonalization.

In addition to delirium, the recognition of MDP is hampered by the low expressiveness with which the patient talks about his painful experiences (“splitting”), and the verbosity and apparent pretentiousness in their description resemble reasoning. However, the presence of massive autopsychic depersonalization explains the monotony and lack of emotionality in the patient's statements, and the unusual experiences and the lack of a sense of contact and understanding characteristic of depersonalization force the patient to repeat the same thing over and over and look for complex metaphors and analogies in order to bring his feelings to the interlocutor.

A feature of this observation is a positive reaction to ECT, which requires special analysis, since in most cases protracted depressive states with massive depersonalization symptoms are resistant even to this type of therapy (Kalinowslky L., 1959, etc.), which is confirmed by the following observations. However, it should be noted that in all cases, ECT was used in the patient in the second half of the depressive phase. Treatment with high doses of imipramine, chloracizin and niamid, used separately, was ineffective. Only about the combination therapy with imipramine and chloracizine was it possible to achieve improvement.

Treatment with high doses of imipramine, chloracizin and niamid, used separately, was ineffective. Only about the combination therapy with imipramine and chloracizine was it possible to achieve improvement.

Further testing of this empirically found technique for the treatment of treatment-resistant depressive states showed its effectiveness in some patients.

The following observation illustrates the formation of long-term depersonalization in a patient with a bipolar course of MDP.

Observation 4. Patient V., born in 1939, engineer. There were no mental patients in the family. Father is gloomy, withdrawn, died early from a myocardial infarction. My mother's aunt is diabetic. Developed normally. At work, he was considered a capable, promising employee, he has several inventions. By nature emotional, soft, sociable.

As a child suffered from spasmophilia and pneumonia. At the age of 16-17, a non-toxic goiter was discovered, in 1960, due to the occurrence of a state of anxiety associated by endocrinologists with a thyroid disease, a strumectomy was performed.

From the age of 8-10 years, according to the patient, there were short-term periods of "sadness" and "arrogance". From the age of 14, mood swings took on a distinct seasonal character: in summer he was sad, depressed, with little initiative, in winter - energetic, enterprising, self-confident. For the first time he turned to a psychiatrist in 1968, at the age of 29. He was hospitalized due to a depressive state, characterized by a melancholic syndrome with elements of anxiety and lasting from June to October 1968. From December 1968 to May 1969, the manic phase lasted. During this period, he was very productive at work, performed several studies well, but conflicts often arose with colleagues, whom the patient irritated with categoricalness, intolerance, and self-confidence.

There was almost no bright interval, since June 1969 a protracted depressive state has paid off.

Due to the ineffectiveness of drug therapy in February 1971, ECT (up to 30 bilateral and unilateral currents) was started, but due to severe memory disorders, it had to be interrupted, despite a moderate but short-term improvement in mood.

Treatment with MAO inhibitors (iprazide followed by parenteral niamid) resulted in a marked increase in psychomotor activity and improved mood, but depersonalization disorders remained unchanged. With an increase in the doses of MAOIs, serious side effects occurred: hypotension with collaptoid conditions, urinary retention, the symptom of “cotton legs”. Therefore, MAOIs began to be combined with the precursor of serotonin - tryptophan (up to 3 g per day),

During the first 2 days and the patient's condition significantly improved — first of all, the duration of sleep increased; , working capacity increased, the ability to concentrate appeared, ideas of low value disappeared, for the first time during the illness he asked for an extract. However, he still complained of "insensitivity", lack of emotion, but in contrast to all previous history of the disease. Depersonalization disorders did not burden the patient. April 1971, the patient was discharged with maintenance combination therapy (1-tryptophan with MAO inhibitors). Attempts to reduce doses of 1-tryptophan led to a rapid resumption of depressive symptoms.

April 1971, the patient was discharged with maintenance combination therapy (1-tryptophan with MAO inhibitors). Attempts to reduce doses of 1-tryptophan led to a rapid resumption of depressive symptoms.

Over the next year, he continued to receive supportive therapy, his mood was even with slight subdepressive fluctuations, the main complaints of the patient — were loss of feelings and "a film on the soul", aimlessness and joylessness of existence.

In the summer of 1972, a shallow depressive state without acute melancholy, but with complaints of "absence of any mood", with distinct mental and motor retardation. After a period of relatively even mood at the end of 1972, irritability increased sharply, came into conflict with relatives, in public places. In connection with a quarrel in the store was hospitalized.

Hospital — revived , talkative, carried himself with some arrogance. Subsequently, he said that during this period there was no joy, a feeling of high spirits, but only "cold anger."

Subsequently, he said that during this period there was no joy, a feeling of high spirits, but only "cold anger."

Next hospitalization in the summer of 1974 due to depression: mood was low, complained of "stiffness of mind and body", expressed ideas of low value, sluggish, slow movements, tears in his eyes. However, the main complaints were about “lack of life instinct”, loss of feelings for mother, complete absence of any emotions, “I do everything only out of a sense of duty”, “I don’t feel my body”, “time passes slowly, but I look back and see how everything gone quickly." As a result of treatment with Leponex at a daily dose of 500 mg, short-term states of confusion and orientation appeared, followed by a significant improvement: mood completely normalized, activity appeared, and the intensity of depersonalization experiences, especially somatopsychic ones, decreased. but he continued to complain about the feeling of a film separating living life from him.

In the spring of 1975 - manic state: sociable, willing and talks a lot about himself, speech is accompanied by lively facial expressions; often smiles, responds appropriately to jokes, often interferes in other people's conversations, tries to look after nurses, expresses hope for a cure, but at the same time complains about the lack of a sense of joy; “I work like an automaton, out of a sense of duty”, there is no feeling of contact with the interlocutor, there are no feelings for loved ones, “everything is only in my mind”.

After discharge, the patient continued to receive prophylactic therapy with lithium salts. In subsequent years, the affective fluctuations subsided completely, although depersonalization, mostly autopsychic, continued to persist. In the last 2 years, there has been a significant mitigation of the phenomena of depersonalization: he again started creative work and met a woman for whom he had warm feelings. However, he continues to complain about some blunting of emotions, the lack of full-fledged joy, a feeling of inadequacy in the face of life's difficulties.

In the case of patient V., the diagnosis of MDP (about a bipolar course) is confirmed by distinct depressive and manic states that appeared at the age of 14 and deepened with age. At the age of 30, in the debut of the depressive phase, after a sharp anxiety, depersonalization arose. This phase, unlike the previous ones, was characterized by a depressive-depersonalization syndrome and lasted about 2 years. She was also distinguished by significant resistance to almost all types of antidepressant therapy: tricyclic antidepressants, MAOIs, ECT. in only the combination of tryptophan with MAOIs led to the disappearance of depressive symptoms, although depersonalization remained unchanged. Depersonalization acquired a long-term, protracted course, and under its icy crust, affective attacks continued to occur, not only depressive, but also manic: the patient suffered two distinct manic states (angry and solar mania), in which, however, he did not experience either a feeling of joy or feelings of own mood, no attachments. Such a "cold mania" could suggest a schizophrenic process, but the history of the disease and, most importantly, the constant experience of mental pain due to the loss of emotions indicate that in this case there is not an emotional defect, but depersonalization. The affective seizures completely disappeared after the start of prophylactic lithium treatment, and the onset of a gradual mitigation of depersonalization coincided with Leponex therapy.

She was also distinguished by significant resistance to almost all types of antidepressant therapy: tricyclic antidepressants, MAOIs, ECT. in only the combination of tryptophan with MAOIs led to the disappearance of depressive symptoms, although depersonalization remained unchanged. Depersonalization acquired a long-term, protracted course, and under its icy crust, affective attacks continued to occur, not only depressive, but also manic: the patient suffered two distinct manic states (angry and solar mania), in which, however, he did not experience either a feeling of joy or feelings of own mood, no attachments. Such a "cold mania" could suggest a schizophrenic process, but the history of the disease and, most importantly, the constant experience of mental pain due to the loss of emotions indicate that in this case there is not an emotional defect, but depersonalization. The affective seizures completely disappeared after the start of prophylactic lithium treatment, and the onset of a gradual mitigation of depersonalization coincided with Leponex therapy. The gradual mitigation of depersonalization and the return of the patient to creative work, his desire to restore personal attachments are also indicate the absence of an emotional-volitional defect characteristic of schizophrenia.

The gradual mitigation of depersonalization and the return of the patient to creative work, his desire to restore personal attachments are also indicate the absence of an emotional-volitional defect characteristic of schizophrenia.

Thus, the most characteristic of this observation is that the depersonalization that appeared at the onset of an anxiety-depressive attack continued to exist for almost 10 years during the period of depression, and in remission, and during the period of mania. We observed only 3 patients with distinct manic and depersonalization symptoms: one of them was diagnosed with MDP, the other had fairly typical manic and depressive phases, as well as minor epileptic seizures since childhood. After the operation on the temporal lobe, the series of seizures disappeared, but affective attacks acquired extreme intensity and tension, depressive states began to proceed with a depressive-depersonalization syndrome, then depersonalization began to constantly capture light intervals, and then spread to manic periods. When analyzing this case, the question arises of what causes the therapeutic resistance of patient V. - depersonalization or a protracted course. The fact that resistance to treatment was incomplete (in the initial period of therapy there was some improvement) suggests that the very duration of the phase and, accordingly, treatment causes addiction to the drug. But this reasoning does not apply to est. It should also be noted that all MDP patients resistant to various types of antidepressant therapy, examined by us in the women's department of one of the city hospitals, had a depressive-depersonalization syndrome, and the phases were protracted (more than 1 year) in 16 out of 17 of these patients, and 12 - more than 2 years (Barshtein E. and Nuller Yu. L., 1975).

When analyzing this case, the question arises of what causes the therapeutic resistance of patient V. - depersonalization or a protracted course. The fact that resistance to treatment was incomplete (in the initial period of therapy there was some improvement) suggests that the very duration of the phase and, accordingly, treatment causes addiction to the drug. But this reasoning does not apply to est. It should also be noted that all MDP patients resistant to various types of antidepressant therapy, examined by us in the women's department of one of the city hospitals, had a depressive-depersonalization syndrome, and the phases were protracted (more than 1 year) in 16 out of 17 of these patients, and 12 - more than 2 years (Barshtein E. and Nuller Yu. L., 1975).

In order to find out whether the therapeutic resistance of depressive-depersonalization states is associated only with a protracted course, or whether other factors also matter, the results of therapy of patient L. , suffering from manic-depressive with depressive-depersonalization syndrome.

, suffering from manic-depressive with depressive-depersonalization syndrome.

A distinctive feature of the depressive states of patient L was their low therapeutic sensitivity. Despite the variety of treatment methods used: imipramine, amitriptyline, perofran, transamine, ECT, etc., the duration of the depressive phases remained unchanged, and improvements occurred only when antidepressant therapy was used at the end of the spontaneous course of the phases. In this case, the therapeutic resistance of a patient with depressive-depersonalization syndrome cannot be explained by the protracted course of depression, as in observation 2, since the duration of the phases in patient L. usually did not exceed 3 months. Thus, the extremely low curability of depressive-depersonalization states is inherent in this syndrome, regardless of the duration of the attacks. Protracted depressions are also characterized by therapeutic resistance, and since depressive-depersonalization states, as already mentioned above, are characterized by a long course (E. I. Barshtein, Yu. L. Nuller, 1975), then the difficulties that arise in their treatment are usually due to two factors: both the structure of the syndrome and the duration of the phase.

I. Barshtein, Yu. L. Nuller, 1975), then the difficulties that arise in their treatment are usually due to two factors: both the structure of the syndrome and the duration of the phase.

Of the 315 patients with MDP under our long-term observation, in 14 depressive phases were characterized by a depressive-depersonalization syndrome (i.e., approximately 4.5%), and in 3 of them the phases lasted from 2 to 4 years, in 7 from 1 up to 2 years, 2 - from 9 to 12 months and only 2 - less than 6 months. In the remaining 300 patients with MDP, whose depressive states were characterized by other syndromes, phases lasting more than 1 year occurred only in 32 people, i.e. in 11%, and while in the subgroup with depressive-depersonalization syndrome, protracted phases were observed in 71% of patients, these differences are highly significant (p < 0.001). The average duration of the phases characterized by depressive-depersonalization syndrome was 13.4 months, while in the remaining 300 patients with MDP it was 6 months (p < 0. 05).

05).

Of all the methods of antidepressant therapy used (except for phenazepam and leponex), the empirically found combination of chloracizine with imipramine (melipramine) gave a relatively better effect: a positive effect was observed in 4 out of 12 patients, in 2 there was a sharp exacerbation of anxiety and melancholy, and in 6 treatment turned out to be ineffective. Usually we used the following scheme: during the week melipramine up to 250-300 mg, then during the week the combined use of 150-200 mg of melipramine with 45-75 mg of chloracizin, then during the week chloracizin 90-120 mg, and then re-appointed melipramine. Similar cycles of treatment were carried out 1-3 times.

When treating patients with depersonalization-depressive syndrome, one should always remember that these patients are the most dangerous in terms of suicide. Therefore, the use of antidepressants recommended by some authors with a pronounced stimulating component of action is not only ineffective, but also very dangerous, since a possible exacerbation of symptoms often leads to suicidal attempts. But even in the treatment with anxiolytic drugs, a short-term increase (more precisely, release) of melancholy during the period of reduction of depersonalization is possible, which is also accompanied by an increased risk of suicide.

But even in the treatment with anxiolytic drugs, a short-term increase (more precisely, release) of melancholy during the period of reduction of depersonalization is possible, which is also accompanied by an increased risk of suicide.

The most effective means in the treatment of such conditions are powerful anxiolytics, in particular, we studied clozepine (leponex) and phenazepam. The results of such therapy were superior to the results of the traditional use of antidepressants. More details are given below.

Difficulties and failures encountered in clinical practice in the treatment of patients with depressive-depersonalization syndrome are also largely due to the difficulties that arise in its psychopathological qualification, and, in particular, the fact that it often “masks” as asthenic-depressive-hypochondriac states. Relatively often, patients with severe depersonalization are diagnosed with schizophrenia during the initial examination. This is facilitated by the following features of such states: the unusualness of sensations, the inability to describe them in everyday terms, leads to the fact that patients resort to complex metaphors, unusual comparisons, producing, at first glance, the impression of pretentiousness, deliberateness. In addition, hidden anxiety and, most importantly, the loss of a sense of contact with the interlocutor, the fear that the doctor cannot understand his condition, force the patient to repeatedly repeat the same thought in different expressions, looking for new terms. This verbosity, which is not characteristic of patients with a classic depressive syndrome, is sometimes regarded as schizophrenic reasoning.

In addition, hidden anxiety and, most importantly, the loss of a sense of contact with the interlocutor, the fear that the doctor cannot understand his condition, force the patient to repeatedly repeat the same thought in different expressions, looking for new terms. This verbosity, which is not characteristic of patients with a classic depressive syndrome, is sometimes regarded as schizophrenic reasoning.

Some of the statements of patients, arising from their feelings, for example, caused by a violation of the sense of time, thoughts about immortality in patient L. (observation 3), can be regarded as primary nonsense. And, finally, the assessment of the state of such patients is significantly complicated by the absence of typical depressive symptoms in them: they experience acute melancholy and are not inclined to attach importance to low mood, since they consider it a logical consequence of the main, from their point of view, manifestation of the disease (“death” , "losing yourself", etc.