Coping with guilt feelings

10 Tips for Dealing with Guilt I Psych Central

Overcoming guilt is possible, even if it’s been lingering for a while.

Guilt is a sense of regret or responsibility for thoughts, words, or actions. It can happen when you perceive you’ve harmed someone, think you’ve made a mistake, or have gone against your personal moral code of conduct.

Feeling guilty can be a positive emotion in some cases and may even help you learn from your mistakes.

But you can also feel guilty for situations that you believe were your fault or even incidents that were not your fault at all. People can also use guilt-provoking tactics to manipulate someone into doing things they’d rather not do.

Whether it’s misplaced guilt, appropriate guilt, or guilt brought on by others, there are effective ways to deal with and overcome it — even if you’ve carried it for a while.

A 2018 study suggests that guilt is a learned social emotion that may play a role in successful interaction and cooperation within a group.

When guilt is present, it could be a sign telling you to look closer at specific situations or behaviors. It can also help guide you in repairing any perceived wrongdoings.

Guilt can also arise from assumed and not actual responsibility for an event or situation.

Toxic guilt is a type of guilt that no longer motivates you to make positive changes.

A 2018 study suggests that guilt can expand past the guilt-inducing incident and become generalized to the whole self. This means that you may end up feeling bad about yourself instead of just feeling remorseful for your behavior.

In addition, toxic guilt can result from not knowing how to effectively manage guilty feelings and from guilt other people may place on you.

If you often find yourself allowing guilt to guide your choices or behaviors, you may be experiencing toxic guilt.

Guilt can feel heavy and difficult to offload. Determining where it’s coming from can also be a challenge.

Still, it is possible to move past guilty feelings no matter how long they’ve lingered.

Learning to manage guilt starts with identifying its source. Some questions you can ask yourself to help understand the root of your guilt include:

- What happened to cause this guilty feeling?

- What specific aspect of this do I feel guilty about?

- Did I really do something wrong, or am I just perceiving I did something wrong?

- Is someone else making me feel guilty?

- Is it in my control to fix the situation?

- Could fixing the situation help?

The answers to these questions may help you understand where the guilt is coming from and the best way to manage it.

But keep in mind that guilt can also be associated with mental health conditions such as depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

If you have difficulty managing guilt, it might be helpful to talk with a mental health professional about your concerns.

Once you understand why you may be feeling guilt, the next step is to figure out how to manage it. Consider trying some of these strategies.

Consider trying some of these strategies.

Acknowledge it exists

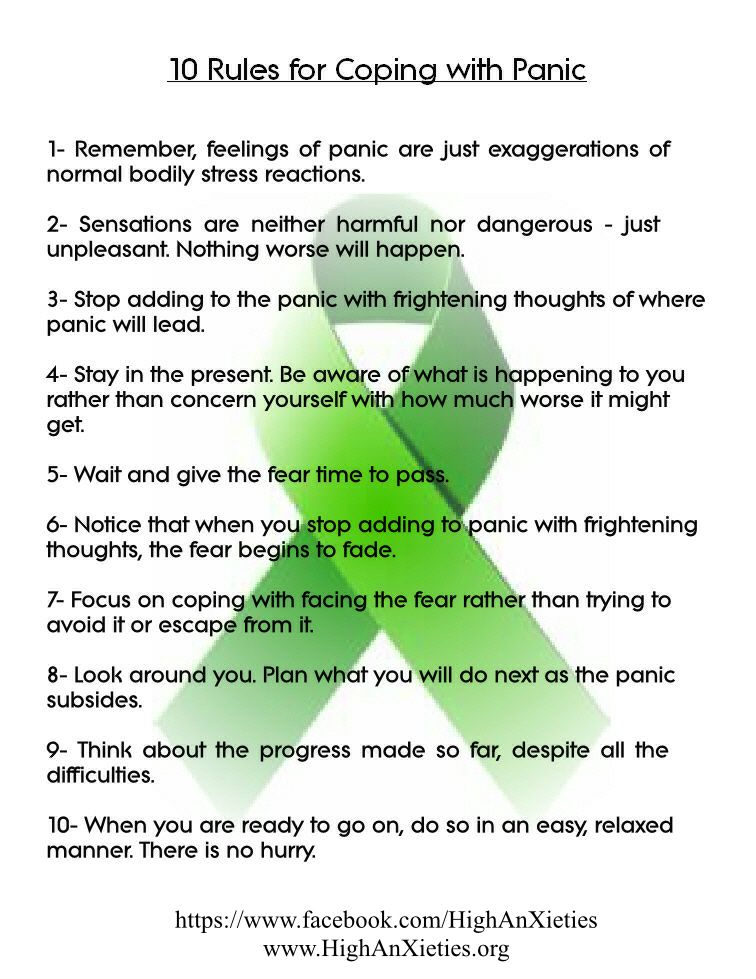

Sometimes guilt can remain hidden underneath other symptoms such as anxiety or sleeplessness. This can make it challenging to determine what’s really bothering you.

Identifying whether guilt is the root cause of these challenges can clarify the situation and help you figure out the next steps you need to take.

Eliminate negative self-talk

Though guilt can initiate positive action, it can also cause you to associate your behavior with who you are as a person. This can lead to inaccurate self-assessment and negative self-talk such as “I’m a bad person.”

Try to remember that although the behavior may have been less than ideal, it doesn’t define who you are.

Find out if there’s a reason to feel guilty

Guilt can at times be unwarranted because the person involved has moved on from the incident or has already forgiven you.

So, think about asking the person how they really feel. You might be surprised to find out that you’ve been carrying guilt for no reason.

You might be surprised to find out that you’ve been carrying guilt for no reason.

Remind yourself of all that you do

When feeling guilty, you might have trouble remembering all the positive things you do. Consider making a list of all the acts of kindness you bestow onto others.

You may find that the number of positive actions on the list far outweigh any perceived transgressions.

Realize it’s OK to have needs

Guilt is often rooted in worries that you’re selfish with your time, money, or energy. However, it’s helpful to remember that no one can be everything to everybody all the time.

You also have needs, and they’re equally as valid as the needs of others.

Establish boundaries

Guilt can result from unclear boundaries. For example, you may feel guilty when trying to communicate your needs to others, or you may feel pangs of guilt when you don’t do what others ask.

Establishing healthy boundaries involves making your expectations clear. It establishes what behaviors you will accept from others and what behaviors others can expect from you.

It establishes what behaviors you will accept from others and what behaviors others can expect from you.

Having these boundaries in place can help prevent guilt when dealing with others.

Make amends

Sometimes, the presence of guilt may indicate the need to apologize for your behavior — a call to action, so to speak. Once these amendments are made, remorseful feelings often seem to fade away.

If you can no longer make amends to someone, maybe because they’ve passed away, you can try journaling or writing a letter to say what you couldn’t say at the time.

You can then discard it in some way — such as ripping it up or burning it — afterward as an act of closure.

Understand what you can control

It might be beneficial to examine the source of the guilt and determine what aspects you can manage.

For example, suppose you feel responsible for something that happened years ago. It might be more helpful at this point to focus on determining what you can do now to help the situation.

If nothing can change the situation, bear in mind that holding onto guilt won’t likely deliver the change you’re looking for. Try to have some compassion for yourself.

Remember that some things are unchangeable, and that’s OK!

Address any mental health challenges

If mental health conditions or past trauma are playing a role in your guilt, it might be a good idea to talk with a mental health professional.

They can work with you to identify areas you may need help with and offer strategies to manage your guilty feelings.

Acknowledge that perfection doesn’t exist

If you hold yourself to a high standard, and even the slightest infraction leaves you riddled with guilt, it might be beneficial to remind yourself that no one is perfect.

We all make mistakes.

Making mistakes doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. It simply means that you’re learning and growing as you navigate through this thing called life — just like everyone else.

Getting rid of guilt may require self-reflection to identify where the remorse is coming from and why you’re feeling it. It also involves determining if you’re experiencing misplaced guilt, toxic guilt, or actual regret for something you’ve done.

It also involves determining if you’re experiencing misplaced guilt, toxic guilt, or actual regret for something you’ve done.

Whether your guilt is justified or based on imagined responsibility, remember that you’re human, and we all make mistakes.

Try to acknowledge your feelings, make amends if necessary, and then forgive yourself. If you need help letting go of persistent guilty feelings, consider reaching out to a mental health professional.

Not sure where to start? You can check out Psych Central’s hub for finding mental health support.

How to Stop Feeling Guilty: 10 Tips

Sometimes we feel guilty for setting boundaries or relaxing. Or, we don’t know how to move forward after we do something wrong.

Over the course of your life thus far, you’ve probably done a thing or two you regret.

Most people have, since mistakes are a natural part of human growth. Still, the guilt that creeps in and stakes out space in your consciousness can cause plenty of emotional and physical turmoil.

You might know guilt best as the nauseating twist in your stomach that accompanies the knowledge you’ve hurt someone else. Perhaps you also deal with recurring self-judgment and criticism related to your memories of what happened and your fear of others finding out.

As an emotion, guilt has a lot of power.

Guilt can help you acknowledge your actions and fuel your motivation to improve your behavior. It might also lead you to fixate on what you could have done differently.

If you’ve never felt able to come clean about a mess-up, your guilt might feel magnified to an almost unbearable degree.

Though guilt can sometimes promote positive growth, it can also linger and hold you back — long after others have forgotten or forgiven what happened.

Grappling with the weight? These 10 tips can help lighten your load.

In the moment, ignoring your guilt or trying to push it away might seem like a helpful strategy. If you don’t think about it, you might reason, it will eventually dwindle and disappear. Right?

Right?

This is actually not the case.

Like other emotions, unaddressed guilt can stick around, making you feel worse over time.

Refusing to acknowledge your guilt might temporarily keep it from spilling into your everyday life, but masking your emotions generally doesn’t work as a permanent strategy. Truly addressing guilt requires you to first accept those feelings, however unpleasant they are.

Give this exercise a try:

- Set aside some quiet time for yourself.

- You can bring along a journal to keep track of your thoughts.

- Say to yourself, or write down, what happened: “I feel guilty because I shouted at my kids.” “I broke a promise.” “I cheated on a test.”

- Mentally open the door to guilt, frustration, regret, anger, and any other emotions that might come up. Writing down what you feel can help.

- Sit with those feelings and explore them with curiosity instead of judgment. Many situations are more complex than they first appear.

Picking apart the knot of distress can help you get a better handle on what you’re really feeling.

Picking apart the knot of distress can help you get a better handle on what you’re really feeling.

If you have a hard time acknowledging guilt, regular mindfulness meditation or guided journals may make a difference. These practices can help you become more familiar with emotions, making it easier to accept and work through even the most uncomfortable ones.

Guilt can happen on an individual or collective level. Some people shift in and out of each type throughout their lifetime. Others may feel one or more type of guilt at the same time:

- Natural guilt: Natural guilt, simply put, is what you feel after you think you did something wrong. For example, if you break a promise to a friend, you might convince yourself you’re a bad friend. You chastise and think about what you should have done. You made a promise, and naturally, you feel guilty, prompting you to want to apologize. Natural guilt is often temporary and goes away after resolution.

- Chronic guilt: This type happens from prolonged exposure to stress.

Chronic guilt affects a person’s ability to regulate their emotions. A teacher, for example, may feel overworked and emotionally drained, which can affect relationships with students. The resulting guilt becomes a symptom of chronic-work related stress, or burnout. Some researchers argue for the inclusion of guilt in clinical evaluations of burnout. Chronic guilt can also occur with episodes of major depression.

Chronic guilt affects a person’s ability to regulate their emotions. A teacher, for example, may feel overworked and emotionally drained, which can affect relationships with students. The resulting guilt becomes a symptom of chronic-work related stress, or burnout. Some researchers argue for the inclusion of guilt in clinical evaluations of burnout. Chronic guilt can also occur with episodes of major depression. - Collective guilt: This type involves a sense of group or shared responsibility. Residents of a city may experience collective guilt about people experiencing homelessness in their neighborhood. In this scenario, the residents feel personal responsibility and guilt about not taking action to help. Collective guilt is harder to resolve since it’s embedded within systemic problems.

- Survivor guilt: Traumatic events, such as witnessing a large-scale tragedy, may cause feelings of remorse and sadness. This could look like someone surviving an accident and then feeling guilty for the people who did not.

Conversely, you may also feel guilty for being happy to be alive. Survivor guilt is characterized by conflicting emotional states.

Conversely, you may also feel guilty for being happy to be alive. Survivor guilt is characterized by conflicting emotional states.

Before you can successfully navigate guilt, you need to recognize where it comes from.

It’s natural to feel guilty when you know you’ve done something wrong. But guilt can also take root in response to events you didn’t have much, or anything, to do with.

Owning up to mistakes is important, even if you only admit them to yourself. It’s equally important to take note when you unnecessarily blame yourself for things you can’t control.

People often experience guilt over things they can’t be faulted for. You might feel guilty about breaking up with someone who still cares about you, or because you have a good job and your best friend can’t seem to find work.

Guilt can also stem from the belief that you’ve failed to fulfill expectations you or others have set. Of course, this guilt doesn’t reflect the effort you’ve put in to overcome the challenges keeping you from achieving those goals.

Some common causes of guilt include:

- surviving trauma or disaster

- conflict between personal values and choices you’ve made

- mental or physical health concerns

- thoughts or desires you believe you shouldn’t have

- taking care of your own needs when you believe you should focus on others

Is someone else constantly making you feel guilty? Check out our article on how to address guilt-tripping.

Guilt manifests in different ways. You may experience guilt when you feel responsible for a mistake. Or, you may feel guilty if you feel responsible for something that happened to someone else.

Guilt is not the same as shame, which implies feelings of inadequacy for not meeting self-imposed expectations. For example, you might feel shame for posting a selfie and later regret how you look in the picture, but this doesn’t necessarily make you a “bad” person or morally irresponsible.

Although shame and guilt share overlapping characteristics, signs of guilt tend to imply a moral wrongdoing. This can include:

This can include:

- feelings of responsibility for one’s actions

- desire to “fix” situations

- self-esteem issues

- negative self-criticism

Signs of unacknowledged guilt may include:

- downplaying

- defensiveness

- lying

- negative beliefs about yourself and your character

Physical signs of guilt often overlap with symptoms of mood disorders, like anxiety and depression:

- muscle tension

- fatigue

- insomnia

- digestive issues

- crying

A 2020 study further explains that frowning and neck touching may be associated with non-verbal patterns of guilt—at least when someone else observes a guilty individual.

Taking responsibility for guilt is one of the first steps to finding resolve.

A sincere apology can help you begin repairing damage after a wrongdoing. By apologizing, you convey remorse and regret to the person who was hurt, and let them know how you plan to avoid making the same mistake in the future.

You may not receive forgiveness immediately — or ever — since apologies don’t always mend broken trust.

Sincerely apologizing still helps you heal, though, since it offers you the chance to express your feelings and hold yourself accountable after messing up.

To make an effective apology, you’ll want to:

- acknowledge your role

- show remorse

- avoid making excuses

- ask for forgiveness

Follow through by showing regret in your actions.

The most heartfelt apology means nothing if you never do things differently going forward.

Making amends means committing to change.

Maybe you feel guilty for not spending enough time with your loved ones or failing to check in when they needed support. After apologizing, you might demonstrate your desire to change by asking “What can I do to help?” or “How can I be there for you?”

You may not always have the ability to apologize directly. If you can’t get in touch with the person you hurt, try writing a letter instead. Getting your apology out on paper can still be beneficial, even if they never see it.

Getting your apology out on paper can still be beneficial, even if they never see it.

You might owe yourself an apology, too. Instead of clinging to guilt and punishing yourself after an honest mistake, remember: No one does everything right all the time.

To make amends, commit to self-kindness instead of self-blame going forward.

You can’t mend every situation, and some mistakes might cost you a treasured relationship or a close friend. Guilt combined with sadness over someone or something you’ve lost often feels impossible to escape.

Before you can leave the past behind, you need to accept it. Looking back and ruminating on your memories won’t fix what happened.

You can’t rewrite events by replaying scenarios with different outcomes, but you can always consider what you’ve learned:

- What led to the mistake? Explore triggers that prompted your action and any feelings that tipped you over the edge.

- What would you do differently now?

- What did your actions tell you about yourself? Do they point to any specific behaviors you can work on?

It’s pretty common to feel guilty over needing help when you’re coping with challenges, emotional distress, or health concerns. Remember: People form relationships with others to build a community that can offer support.

Remember: People form relationships with others to build a community that can offer support.

Imagine the situation in reverse. You’d probably want to show up for your loved ones if they needed help and emotional support. Most likely, you wouldn’t want them to feel guilty about their struggles either.

There’s nothing wrong with needing help. Life isn’t meant to be faced alone.

Instead of feeling guilty when you need support, cultivate gratitude by:

- thanking loved ones for their kindness

- making your appreciation clear

- acknowledging any opportunities you’ve gained as a result of their support

- committing to paying this support forward once you’re on more solid ground

A mistake doesn’t make you a bad person — everyone messes up from time to time.

Guilt can provoke some pretty harsh self-criticism, but lecturing yourself on how catastrophically you messed up won’t improve things. Sure, you might have to face some external consequences, but self-punishment often takes the heaviest emotional toll.

Instead of shaming yourself, ask yourself what you might say to a friend in a similar situation. Perhaps you’d point out good things they’ve done, remind them of their strengths, and let them know how much you value them.

You deserve the same kindness.

People, and the circumstances they find themselves in, are complex. You may have some culpability for your mistake, but so might the others involved.

Reminding yourself of your worth can boost confidence, making it easier to consider situations objectively and avoid being swayed by emotional distress.

Guilt can serve as an alarm that lets you know when you’ve made a choice that conflicts with your personal values. Instead of letting it overwhelm you, try putting it to work.

When used as a tool, guilt can cast light on areas of yourself you feel dissatisfied with.

Maybe you find it difficult to be honest, and someone finally caught you in a lie. Perhaps you want to spend more time with your family, but something always gets in the way.

Taking action to address those circumstances can set you on a path that’s more in line with your goals.

If you feel guilty for not spending enough time with friends, you might make more of an effort to connect. When stress distracts you from your relationship, you might improve the situation by devoting one night a week to your partner.

It’s also worth paying attention to what guilt tells you about yourself.

Regret over hurting someone else suggests you have empathy and didn’t intend to cause harm. Creating change in your life might involve focusing on ways to avoid making that mistake again.

If you tend to feel bad about things you can’t control, it may be beneficial to explore the reasons behind your guilt with the help of a professional.

Self-forgiveness is a key component of self-compassion. When you forgive yourself, you acknowledge that you made a mistake, like all other humans do. Then, you can look to the future without letting that mistake define you. You grant yourself love and kindness by accepting your imperfect self.

You grant yourself love and kindness by accepting your imperfect self.

Self-forgiveness involves four key steps:

- Take responsibility for your actions.

- Express remorse and regret without letting it transform into shame.

- Commit to making amends for any harm you caused.

- Practice self-acceptance and trust yourself to do better in the future.

People often have a hard time discussing guilt, which is understandable. After all, it’s not easy to talk about a mistake you regret. This means guilt can isolate you, and loneliness and isolation can complicate the healing process.

You might worry others will judge you for what happened, but you’ll often find that isn’t the case. In fact, you may find loved ones offer a lot of support.

The people who care for you will generally offer kindness and compassion. And sharing unpleasant or difficult feelings often relieves tension.

Friends and family can also help you feel less alone by sharing their experiences. Nearly everyone has done something they regret, so most people know what it’s like to feel guilty.

Nearly everyone has done something they regret, so most people know what it’s like to feel guilty.

An outside perspective can also make a big difference, especially if you’re dealing with survivor guilt or guilt about something you had no control over.

Severe or persistent guilt doesn’t always lift easily. Some people find it difficult to work through feelings of guilt that relate to:

- intrusive thoughts

- depression

- trauma or abuse

It’s tough to open up about guilt if you fear judgment. However, avoiding these feelings will usually worsen the situation.

Over time, guilt can affect relationships and add stress to daily life. It can also play a part in sleep difficulty and mental health conditions. Or it can lead to negative coping methods, like substance use.

When an undercurrent of misery, rumination, and regret threads through your daily interactions, keeping you from staying present with yourself and others, professional support might be a good next step.

Finding a therapist or mental health professional can help. They can offer guidance by helping you identify and address the causes of guilt, explore effective coping skills, and develop greater self-compassion.

Guilt belongs in the past. You can begin letting it go by strengthening your resilience and building confidence to make better choices in the future.

If you’re struggling to resolve feelings of guilt, know you don’t need to do it alone. Therapy can offer a safe space to learn how to forgive yourself and move forward.

Crystal Raypole has previously worked as a writer and editor for GoodTherapy. Her fields of interest include Asian languages and literature, Japanese translation, cooking, natural sciences, sex positivity, and mental health. In particular, she’s committed to helping decrease stigma around mental health issues.

Dealing with Guilt - Snob

In the new book Mood Therapy, published by Alpina Publisher, British professor of psychology and behavioral sciences, David Burns, talks about how to identify the first signs of depression, deal with feelings of guilt and how to understand yourself. "Snob" publishes one of the chapters of

"Snob" publishes one of the chapters of

No book on depression is complete without a chapter on guilt. What is the function of guilt? Writers, spiritual leaders, psychologists and philosophers have been trying to answer this question for centuries. What is guilt based on? Maybe it was the concept of "original sin" that gave rise to it? Or the Oedipal incest fantasies and other taboos that Freud talked about? Is guilt a realistic and useful component of the human experience? Or is it a "useless emotion" that humanity would be better off without, as some modern writers in the field of popular psychology suggest?

When computational mathematics was introduced, scientists found that they could now easily solve complex motion and acceleration problems that were extremely difficult to solve with the old methods. Cognitive theory has similarly given us a kind of emotional "calculus" tool that facilitates progress through the thorns of philosophical and psychological questions.

Let's see what can be learned from the cognitive approach. Guilt is the emotion you feel when you have the following thoughts:

- I did something that I shouldn't have done (or didn't do that I should have) that doesn't meet my moral standards or notions of justice.

- Such "bad behavior" shows that I am a bad person (or I have a tendency to do harm, I have a spoiled character, a rotten gut, etc.).

The idea of one's own "badness" is the main cause of feelings of guilt. Without it, actions that cause harm lead to healthy feelings of remorse, but not guilt. Remorse arises from an adequate understanding that you intentionally and unreasonably harmed yourself or another person, which violates your personal ethical standards. Remorse is different from guilt because it does not mean that your wrongdoing shows how bad, evil, or immoral you are. In short, you feel remorse or regret about your behavior, while guilt is directed at your Self.

If, in addition to feelings of guilt, you feel depressed, ashamed, or anxious, you are probably following one of the following mental assumptions:

- My "bad behavior" makes me inferior or worthless (this interpretation leads to depression).

- If others knew what I did, they would begin to despise me (this thought causes a feeling of shame).

- I may be avenged, or I may be punished (this thought is disturbing).

The easiest way to assess whether these feelings are beneficial or destructive is to determine whether they contain any of the ten cognitive distortions described in Chapter 3. If these thought errors are present, your guilt, anxiety, depression, or shame are certainly not justified. and unrealistic. I suspect you will find that many of your negative feelings are actually based on such thinking errors.

The first distortion when you feel guilty may be that you did something wrong. Perhaps it is, but perhaps not. Is the behavior that you condemn in yourself really so terrible, immoral, wrong? Or are you exaggerating the scale of the problem? A charming medical laboratory assistant recently brought me a sealed envelope with a sheet of paper on which she wrote something so terrible about herself that she could not say it out loud. When she handed me the envelope with trembling hands, she made me promise not to read it aloud and not to laugh at her. Inside was a message: "I pick my nose and eat boogers!" The premonition of catastrophe and the horror on her face contrasted so strikingly with the trifle written on a piece of paper that I began to laugh. I lost all professional self-control and laughed. Luckily, she laughed heartily, too, and felt relieved.

When she handed me the envelope with trembling hands, she made me promise not to read it aloud and not to laugh at her. Inside was a message: "I pick my nose and eat boogers!" The premonition of catastrophe and the horror on her face contrasted so strikingly with the trifle written on a piece of paper that I began to laugh. I lost all professional self-control and laughed. Luckily, she laughed heartily, too, and felt relieved.

Am I saying that you never misbehave? No. Such a position would be highly unrealistic. I just want to emphasize that the more you exaggerate the scale of your mistakes, the greater will be the needless torment and self-criticism.

The second key distortion that leads to guilt is the tendency to label yourself a "bad person" because of what you have done. It was this superstitious destructive thinking that led to witch hunts in the Middle Ages! You may have actually done something bad, spiteful, hurtful, but it's inappropriate to call yourself "bad" or "spoiled" because you'll end up wasting energy on worrying and self-blaming rather than creatively looking for the best problem-solving strategy.

Another common guilt-producing distortion is personalization. You unreasonably take responsibility for something you didn't do. Let's say you offer constructive criticism to your boyfriend, who reacts defensively and offended. You may blame yourself for being upset and jump to the conclusion that your comment was inappropriate. In fact, it was his own negative thoughts that upset him, not your comment. Moreover, these thoughts are probably distorted. Perhaps he thought that your criticism implied that he was not good enough, and concluded that you did not respect him.

And besides, did you put this illogical thought into his head? Obviously not. He did it himself, so you can't take responsibility for his reaction.

Since cognitive therapy claims that it is thoughts that create feelings, you may come to the nihilistic conclusion that you cannot harm anyone no matter what you do, and therefore you have the right to do anything. After all, why not leave the family, cheat on your wife, or cheat on a business partner? If they're upset, it's their problem, it's their thoughts, right?

No! Here we again emphasize the importance of the concept of "cognitive biases". As long as a person's feelings of frustration are caused by distorted thoughts, you can say that he himself is responsible for his suffering. If you blame yourself for this person's pain, it's a personalization error. Conversely, if a person's suffering is caused by valid, undistorted thoughts, then it is real and may indeed have an external cause. For example, if you hit me in the stomach, I will probably think, “You hit me! It hurts you!” In this case, you are responsible for my pain, and your opinion that you hurt me is in no way the result of a distorted perception. Your remorse and my discomfort are real and authentic.

As long as a person's feelings of frustration are caused by distorted thoughts, you can say that he himself is responsible for his suffering. If you blame yourself for this person's pain, it's a personalization error. Conversely, if a person's suffering is caused by valid, undistorted thoughts, then it is real and may indeed have an external cause. For example, if you hit me in the stomach, I will probably think, “You hit me! It hurts you!” In this case, you are responsible for my pain, and your opinion that you hurt me is in no way the result of a distorted perception. Your remorse and my discomfort are real and authentic.

Inadequate demands with the word "should" is a direct path to guilt. Irrational demands on yourself mean that you should be perfect, omniscient or omnipotent. Such perfectionist “rules of life” harm you by creating impossible expectations and making you inflexible. One such example is "I should always be happy." And here is the corollary of this rule: every time you are upset, you feel like a failure. Since it is obvious that the goal of achieving eternal happiness is unrealistic for any person, such a rule only harms and replaces the real responsibility for oneself.

Since it is obvious that the goal of achieving eternal happiness is unrealistic for any person, such a rule only harms and replaces the real responsibility for oneself.

Other inadequate "should" requirements are based on the premise that you know everything. They assume that you have all the knowledge in the universe and can predict the future with absolute accuracy. For example, you think, “I shouldn't have gone to the beach this weekend because I started to get the flu. What a fool I am! Now I'm so sick I'll have to lie in bed for a week." Such reproaches are unrealistic, because you did not know for sure that due to a trip to the beach, the condition would worsen so much. If you knew this, you would have acted differently. You are human and made that decision, later realizing that your guess was wrong.

The third kind of "must" requirement is based on the premise that you are omnipotent. They assume that, like God, you have limitless possibilities, you can control yourself and other people and achieve whatever goal you want. You miss a tennis pitch and startle, exclaiming, "I shouldn't have missed that shot!" Why not? Is your tennis game so perfect that you can't miss a serve?

You miss a tennis pitch and startle, exclaiming, "I shouldn't have missed that shot!" Why not? Is your tennis game so perfect that you can't miss a serve?

It is clear that these three categories of demands with the word “must” create an inadequate sense of guilt, since they are not based on reasonable arguments.

In addition to distortions, several other criteria can help distinguish abnormal guilt from healthy feelings of remorse or regret. It is the intensity, duration and consequences of your negative emotions. Let's apply them to assess the unbearable guilt of a married 52-year-old high school teacher named Janice. For many years, Janice was in severe depression. Her problem was that she was relentlessly tormented by the memories of two cases of shoplifting that happened when she was 15. Having led a completely honest life since then, she could not overcome the memory of those two incidents. She was haunted by guilt-creating thoughts: "I am a thief, a liar, a bad person, I am a fake. " The agony of her guilt was so intense that every night she prayed that God would let her die in her sleep. Every morning, waking up alive, she experienced bitter disappointment and said to herself: “I am such a bad person that even God does not want to take me away.” In desperation, she loaded her husband's gun, pointed it at her heart, and pulled the trigger. The weapon misfired. She didn't cock the trigger properly. Janice felt the final fiasco: she couldn't even kill herself! Throwing down the gun, she sobbed in despair.

" The agony of her guilt was so intense that every night she prayed that God would let her die in her sleep. Every morning, waking up alive, she experienced bitter disappointment and said to herself: “I am such a bad person that even God does not want to take me away.” In desperation, she loaded her husband's gun, pointed it at her heart, and pulled the trigger. The weapon misfired. She didn't cock the trigger properly. Janice felt the final fiasco: she couldn't even kill herself! Throwing down the gun, she sobbed in despair.

Janice's guilt is not justified not only because of the obvious distortions, but also because of the intensity, duration and consequences of what she felt and said to herself. Her feelings are nothing like healthy remorse or regret about shoplifting, it's an irresponsible destruction of her self-esteem that blinds her, does not allow her to live in the here and now, and does not correspond to any real transgression. The consequences of her guilt create the ultimate paradox: the belief that she is a bad person forced her to attempt suicide, the most destructive and senseless act in the world.

The vicious cycle of guilt

Even if you experience unhealthy guilt based on distortions, you can become trapped in the illusion that your guilt is justified as soon as you start to feel guilty. Such illusions can be very powerful and convincing. Here are your thoughts:

- I feel guilty and condemned. It means I'm really bad.

- Because I am bad, I deserve to suffer.

Thus, guilt convinces you of your own worthlessness and leads to even greater feelings of guilt. This cognitive-emotional connection locks your thoughts and feelings into each other. You are caught in a vicious circle that I call the "vicious circle of guilt."

This vicious cycle is fueled by emotional rationale (see the chapter on cognitive distortions). You automatically assume that because you feel guilty, you must have failed somewhere and therefore deserve to suffer. You probably think like this: "I'm bad, so I'm probably bad." This is irrational because your self-hatred does not necessarily prove that you did something wrong. Your guilt only reflects your opinion that you behaved badly. Perhaps this is true, but often this is far from the truth. For example, children are often punished for no reason when parents are tired, irritated, and misinterpret their behavior. Under these circumstances, the child's feelings of guilt obviously do not prove that he or she has done something so terrible.

Your guilt only reflects your opinion that you behaved badly. Perhaps this is true, but often this is far from the truth. For example, children are often punished for no reason when parents are tired, irritated, and misinterpret their behavior. Under these circumstances, the child's feelings of guilt obviously do not prove that he or she has done something so terrible.

Self-flagellation only fuels the cycle of guilt. Guilty thoughts lead to unproductive actions that reinforce your belief that you are worthless. For example, a guilt-prone female neurologist was trying to study for her certification exam. It was difficult for her to study for the test, and she felt guilty that she did not study well. Therefore, she spent a lot of time every evening watching TV, and at this time the following thoughts were spinning in her head: “I should not watch TV. I have to prepare for the exam. I am lazy. I don't deserve to be a doctor. I'm too selfish. I deserve punishment." These thoughts made her feel great guilt. Then she reasoned like this: "This guilt only proves that I am a lazy, bad person." Her self-flagellation and guilt only fueled each other.

Then she reasoned like this: "This guilt only proves that I am a lazy, bad person." Her self-flagellation and guilt only fueled each other.

Like many people who are prone to guilt, she held to the idea that if she punished herself enough, she would eventually be set free. Unfortunately, the opposite is true. Guilt simply sapped her strength and reinforced her belief that she was lazy and inept. The only result of her self-hatred was obsessive nightly raids on the refrigerator, during which she gorged herself on ice cream or peanut butter.

The vicious circle she got into is shown in figure 8.1. Her negative thoughts, feelings, and behaviors combined to create a self-destructive, cruel illusion that she was "bad" and couldn't control herself.

Guilt is irresponsible

If you really did something inappropriate or harmful, does it follow that you deserve to suffer? If you feel the answer to this question is yes, ask yourself, “How long must I suffer? Day? Year? For the rest of your life?" What judgment would you choose to pass on yourself? Are you ready to end your own suffering and stop torturing yourself when your sentence is up? This would at least be a responsible form of time-limited punishment. But first, what is the point of torturing yourself with guilt? If you make a mistake and cause harm, your guilt will not magically undo the mistake. It will not speed up the learning process, nor will it make you less likely to do it again in the future. Other people won't love and respect you more because you feel guilty and put yourself down that way. Guilt will not lead to a productive life. So what's the point?

But first, what is the point of torturing yourself with guilt? If you make a mistake and cause harm, your guilt will not magically undo the mistake. It will not speed up the learning process, nor will it make you less likely to do it again in the future. Other people won't love and respect you more because you feel guilty and put yourself down that way. Guilt will not lead to a productive life. So what's the point?

Many people ask, "But how can I act morally and control my impulses if I don't feel guilty?" This is the prison guard's approach. Apparently, you think that you are so malicious and out of control that you must constantly punish yourself so as not to break loose. Of course, if your behavior hurts others, a small dose of agonizing remorse will help you realize the consequences of your actions than a neutral, non-emotional admission of wrongdoing. But without a doubt, it never helped anyone to consider themselves a bad person. Most often, the belief in one's own worthlessness only contributes to further "bad" behavior.

Change and learning happen faster when you a) recognize that a mistake has occurred and b) develop a strategy to correct the problem. You will make the process much easier if you treat yourself with love and relax. And guilt will only get in the way.

For example, I am sometimes criticized by patients for making a harsh comment that causes them to think in the wrong way. This criticism usually hurts me and makes me feel guilty only if there is some truth in it. If I feel guilty and call myself "bad," I tend to react defensively. I have a desire to deny the mistake, to justify it or to go on the counterattack, because it is disgusting to feel like a “bad person”. This makes it difficult to admit your mistake and correct it. If, on the contrary, I do not scold myself and do not feel that my self-esteem is hurt, it is easy for me to admit a mistake. Then I can easily fix the problem and learn something. The less guilt I feel, the more effectively I deal with the situation.

Thus, if you make a mistake, you need to recognize it, learn from it and change the situation. Does guilt help here? I do not believe in this. Instead of helping to admit one's own mistake, guilt only obscures the tracks. You don't want to hear any criticism. You can't stand your own mistakes because they make you feel terrible. This is why guilt is unproductive.

You might object, “How can I know if I did something wrong if I don't feel guilty? What if I start to indulge in blind excesses, uncontrollable, destructive selfishness, if I don’t feel guilty?

Anything is possible, but I honestly doubt it. You can replace guilt with a more conscious basis of moral behavior - empathy. Empathy is the ability to visualize the consequences of your behavior, both good and bad. This is the ability to realize the impact of your actions on you and on other people, and to feel reasonable, sincere sadness and regret, without calling yourself bad in essence. Empathy creates the necessary mental and emotional climate to regulate behavior in a moral and self-learning way, without having to use the whip of guilt.

Using the following criteria, you can easily determine whether your feelings are normal and healthy remorse or self-destructive, distorted guilt. Ask yourself:

- Did I do something “bad”, “unfair”, hurt knowingly and intentionally? Or am I unreasonably demanding of myself to be perfect, omniscient, or omnipotent?

- Do I call myself a bad or nasty person because of this? Do my thoughts also contain other cognitive distortions such as exaggeration, overgeneralization, etc.?

- Is my regret or repentance realistic? Does it stem from an empathic awareness of the negative consequences of my actions? Is the intensity and duration of my painful emotional reaction appropriate to the act?

- Am I ready to learn from my mistake? What am I doing for this? Do you think how to fix the current situation? Or whine, scrolling through the thoughts of what happened? Or maybe I am punishing myself unjustifiably?

Now let's look at some methods that will help you get rid of misplaced guilt and build self-respect.

1. Diary of recording automatic thoughts. In the previous chapters, you have been introduced to the Automatic Thought Journal, which helps you overcome low self-esteem and feelings of worthlessness. This method gracefully handles many unwanted emotions, including guilt. Write down the event that makes you feel guilty in the Situation column. For example, "I was rude to a colleague" or "Instead of putting in ten dollars, I threw the alumni fundraiser in the trash." Then "tune in" to the tyrant's voice in your head and write down the specific accusations that make you feel guilty. Finally, identify distortions and write down more objective thoughts. You will feel better.

An example of such operation is shown in Table 8.1. Shirley was a sensitive young woman who decided to move to New York to start her career as an actress. After spending a long and exhausting day looking for an apartment, he and his mother took the train back to Philadelphia. Boarding the train, they discovered that no food was provided. Shirley's mother began to complain about the lack of service, and Shirley felt guilt and a wave of self-criticism engulf her. When she wrote down the guilt-producing thoughts and answered them, she experienced significant relief. She told me that by dealing with her guilt, she avoided the tantrum she usually threw in such unpleasant situations (see Table 8.1).

Shirley's mother began to complain about the lack of service, and Shirley felt guilt and a wave of self-criticism engulf her. When she wrote down the guilt-producing thoughts and answered them, she experienced significant relief. She told me that by dealing with her guilt, she avoided the tantrum she usually threw in such unpleasant situations (see Table 8.1).

2. Techniques for neutralizing demands on oneself. Here are some methods for neutralizing the irrational "should" demands you make on yourself. First, ask yourself, “Who said I should? Where is that written?" The point is for you to realize that you are not justified in criticizing yourself. Ultimately, you are the one who sets your own rules. As soon as you see that the rule does not benefit you, you have the right to revise or cancel it. Suppose you tell yourself that you must be able to make your spouse happy all the time. If you understand from experience that this is unrealistic and useless to even try, then you can rewrite this rule, bringing it closer to reality. For example: “I can sometimes make my spouse happy, but of course not all the time. Ultimately, his happiness depends on himself. And I am no more perfect or perfect than he is. Therefore, I will not expect constant gratitude for what I do.

For example: “I can sometimes make my spouse happy, but of course not all the time. Ultimately, his happiness depends on himself. And I am no more perfect or perfect than he is. Therefore, I will not expect constant gratitude for what I do.

When deciding how useful a particular rule is, ask yourself: “What are the advantages and disadvantages of this rule?”, “How does the requirement to always keep my spouse happy helps me, and what is the price of such a belief?” You can evaluate the pros and cons of this internal rule using two columns, as shown in Table 8.2.

Another simple but effective way to save yourself from excessive demands on yourself involves replacing the word “should” with others, also using the two-column technique. For this, the expressions "It would be nice if" or "If I could, I would ..." are well suited. They often turn out to be more realistic and not as frustrating. For example, instead of "I should make my wife happy," you could say, "It would be great if I could make my wife happy because she's upset. I can ask her what's upsetting her and think about how I might be able to help." Or instead of "I shouldn't have eaten ice cream," you could say, "It would have been better if I hadn't eaten that ice cream, but what I did is not the end of the world."

I can ask her what's upsetting her and think about how I might be able to help." Or instead of "I shouldn't have eaten ice cream," you could say, "It would have been better if I hadn't eaten that ice cream, but what I did is not the end of the world."

And another method is to show yourself that your claim is not true. For example, when you say "I shouldn't have done this," you're assuming 1) that you really shouldn't have done it, and 2) it would help if you told yourself that. The Reality Method will reveal, to your surprise, that the exact opposite is true: a) you really should have done exactly what you did and b) it will hurt you if you tell yourself you shouldn't have done it.

Translation: Anna Kogteva

How to get rid of guilt

How to get rid of guilt?

Finding now such a person who could not feel guilty for something in his life is almost impossible. Everyone perceives such a psychological state differently.

First of all, you should listen to yourself and understand the nature of the appearance of guilt in you. If you feel guilty for some specific action in which it was objectively worth doing otherwise, this is normal. If some act torments you and does not allow you to live in peace, you need to understand the issue, because this thought can sit in your head for a long time. You can ask for forgiveness from the person you might have offended, visit a psychologist, and analyze the findings in order to make the right choice in a similar situation.

If you feel guilty for some specific action in which it was objectively worth doing otherwise, this is normal. If some act torments you and does not allow you to live in peace, you need to understand the issue, because this thought can sit in your head for a long time. You can ask for forgiveness from the person you might have offended, visit a psychologist, and analyze the findings in order to make the right choice in a similar situation.

There are situations in which a person is not guilty, but feels in such a way that it has a destructive effect on the psyche and self-esteem.

Guilt has certain functions. More about this:

The first – guilt itself can act as a so-called moral regulator to support the already accepted norms of social behavior.

The second - guilt can be an emotion of self-attitude or a self-evaluative emotion, and will act as an internal regulator. An individual is capable of a responsible or moral act and can judge for himself how lawful or just or how lawful this or that step was. Therefore, based on this, J. Tangney defined guilt as a sense of self-attitude, that guilt can arise as a result of a person’s negative assessment of his specific behavior and will be accompanied by tension, repentance and regret, and will also motivate a person to make up for or correct what he has done.

Therefore, based on this, J. Tangney defined guilt as a sense of self-attitude, that guilt can arise as a result of a person’s negative assessment of his specific behavior and will be accompanied by tension, repentance and regret, and will also motivate a person to make up for or correct what he has done.

Third - our sense of guilt contributes to the prevention of mental disorders.

There are such forms of guilt:

reactive

Reactive guilt will be a person's emotional reaction to the violation of his own norms of acceptable behavior, which is explained in psychology as an emotion or guilt - a state.

preventive

And preventive - will be an emotional experience that may be associated with a possible violation of norms, and therefore is explained in psychology as a feeling or guilt - a trait. Also, preventive guilt can enable us to prevent the exercise of guilt. Therefore, guilt will be experienced by us as a state of discomfort, which is associated with a violation of the moral and legal norms that exist in our society.

Causes of guilt

Classical psychoanalytic theory pays more attention to guilt than to shame. In his structural model of the psyche, Freud noted that guilt arises as a result of conflict between self and superego (Freud, 1923).

Ultimately, he reduces all feelings of guilt to oedipal guilt. Klein, on the contrary, believed that the emerging feeling of guilt is a consequence of the realization that aggressive impulses can harm those close to the person. She called this phase of psychological development the depressive position (Klein, 1935).

Winnicott later described this phase as the anxiety phase, emphasizing the psychological significance in reaching this level of awareness (Pedder, 1982). Thus, the ability to feel guilt develops with the growing awareness of a person, by her actions she can affect others.

From a cognitive (cognitive) point of view, Gilbert (2005) describes guilt as "a warning that we are close to harming someone, or an incentive to correct the situation if we have already offended someone. " He cites research showing that the impulse to avoid harm is in rats.

" He cites research showing that the impulse to avoid harm is in rats.

He suggests that in a person this impulse develops in order to embrace the feeling of guilt. Thus, guilt supports prosocial behavior and builds interpersonal bonds. But an increased sense of responsibility can lead to depression (O'Connor, 2002).

How to get rid of guilt before yourself

It is very difficult to do this on your own, but it is quite possible. The origins of guilt are hidden far in the subconscious, and any insignificant event can become a “trigger” for actualizing this state.

It is necessary to distinguish between such concepts as being guilty of something and feeling guilty. If you have harmed someone with your actions - no matter material or moral - it is quite natural to feel that you are wrong. In this case, it is enough to realize your mistake, correct it if possible, ask for forgiveness from the victim and, perhaps, somehow punish yourself. It is not always easy to walk this path, but in the end, these unpleasant emotions disperse.

Another thing is if the feeling of guilt is rooted in your mind, and you feel it all the time, regardless of their actions.

How to get out of a state of absolute apathy?

To get rid of the constant feeling of guilt, you need:

- Understanding whether you feel guilty for your actions, in which you are not really guilty.

- Recognize that there are no perfect people. Many try to live up to standards, failing which they become disappointed in themselves, and carry that guilt from one day to the next. You have to remember that you don't have to live up to anyone's expectations. You need to develop and be the best not for anyone, but for yourself.

- Don't take the blame for the feelings of others. For example, if you are with a person because you are afraid to offend her with your refusal, by doing so you are destroying both your life and hers. You cannot be responsible for how other people perceive your words or actions.

- Do not take the blame for the actions of others. If someone has made a certain decision, even thanks to your advice, remember that only he is responsible for his actions.

- Errors are normal. If a person is not mistaken, she does not develop and does not learn, so you should not feel guilty for every wrong step.

- Replace guilt with responsibility. Often blame is imposed on us from childhood, “if you don’t clean the room, then you don’t love me,” etc. It can make a person feel guilty and it is embedded in our subconscious. An adult should be responsible for his own actions, and not guilt and remorse.

- Often people manipulate guilt. If someone assures you that you are to blame, it may be manipulation for personal gain. Therefore, you need to defend your opinion.

- You can help get rid of the constant feeling of guilt with the help of a specialist, or you can find various methods on your own.

- For example, write down your situations on a piece of paper, think about each item, and then burn the piece of paper.

You can work on yourself at any age, for this you need a desire! The feeling of guilt cannot be completely removed, but by working with it we will no longer spend a lot of energy on it.

Psychological consultation in our center will help you change your life for the better.

How to get rid of guilt if you are not guilty

Very often, in fact, a person may not be guilty in a given situation. Therefore, you need to pay attention to the following rules:

1) Stop constantly making excuses. When you are accused of something, he will catch himself when you want to be true and try to restrain yourself in any way. You have already been accused, so you don’t need to justify yourself to this person, these excuses will not be accepted anyway.

2) Don't idealize. The dining room does not have people, so it is pointless to strive for this.

3) Learn to say “no” to others. Saying “no” does not mean completely refusing, you can simply always transfer a certain offer to when it is convenient for you, without sacrificing your needs.