Christian marrying jew

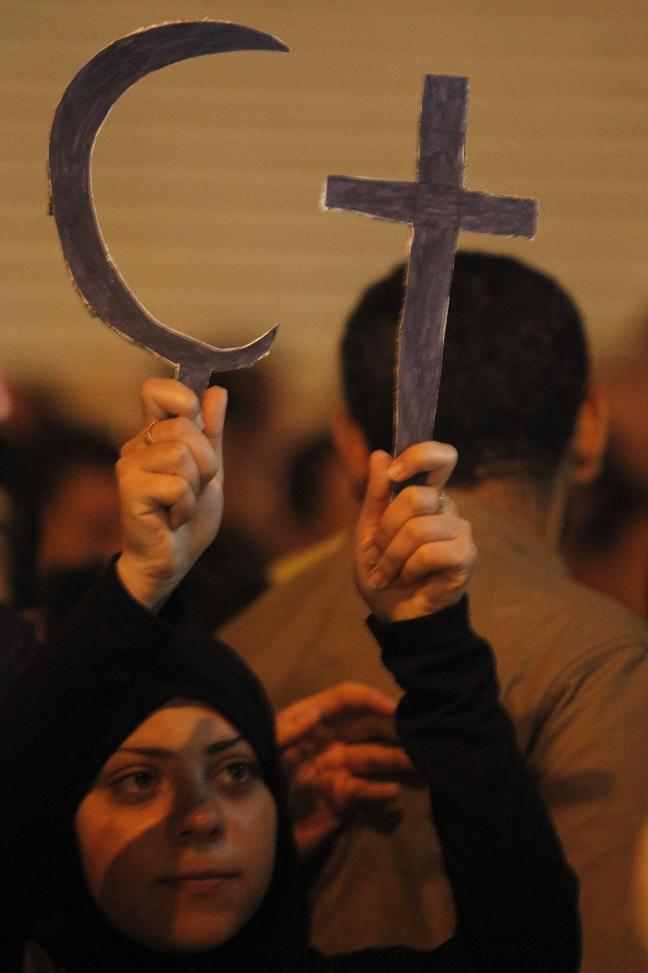

When Jews and Christians Wed

No one was particularly surprised that my sister and I -- like half of all American Jews since 1985 -- ended up marrying outside of our religion, she to a Quaker and I to a Catholic. Finding a Jewish mate just didn't matter much to us.

Our parents grew up with a strong sense of Jewish identity; how could they not? They still vividly recall the aftermath of the Second World War, when the horror of the Holocaust was revealed and the state of Israel was created. Coming out of school, they faced discriminatory quotas and restrictions that limited their life choices. And during those years, most of their friends and dates were Jewish.

My sister and I never assumed the same degree of Jewish identity. We assimilated easily, joined whichever groups we chose, dated both Jews and Gentiles. Marrying outside our religion was an uncomplicated decision.

And yet each of our interfaith marriages has created profound dilemmas. In Strangers to the Tribe: Portraits of Interfaith Marriage (Houghton Mifflin, 1997; $24), Gabrielle Glaser, '86, captures the reality of intermarriage, with all its challenges and complications. Glaser presents the stories of a dozen Jewish-Gentile couples from around the country, each grappling in their own way with disappointed parents, marital tension and questions over how to raise children. Glaser, a journalist, writes smoothly, shows a keen eye for detail and withholds judgment on her subjects.

One thread that runs through Glaser's stories is the reluctance of parents to accept an "outsider" into the family. "It'll never work -- you'll end up divorced," one anguished Jewish mother tells her son. "This will kill your father." Glaser even suggests that at least one of the mixed-faith relationships she profiles was fueled by rebellion against intolerant parents.

The absence of spirituality among many of those who opt to marry outside their religion emerges as another theme. The Christians in Strangers to the Tribe frequently seem like strangers to their own church. And the Jews, while identifying culturally with Judaism, don't seem, for the most part, to have strong religious beliefs. "When it comes right down to it," says a Jewish husband, "it's more being a member of a tribe than even being a member of a religion." The Jewish son of one interfaith couple says that while he feels comfortable in temple, he can't remember the last time he went.

"When it comes right down to it," says a Jewish husband, "it's more being a member of a tribe than even being a member of a religion." The Jewish son of one interfaith couple says that while he feels comfortable in temple, he can't remember the last time he went.

Some of the deepest thinking about Judaism comes from those who, as converts, chose their religion. Rick, a Methodist of Irish-Italian descent, married a Jew and then studied Judaism prior to converting. According to Glaser, he was taken by "the Jewish notion of man's responsibility to atone for his wrongdoings to his fellow man, rather than praying to God for forgiveness. He was impressed that Jews see rabbis as learned peers, not as intermediaries to God." Ironically, by the end of his studies, Rick appeared to have accepted the tenets of Jewish faith far more seriously than his father-in-law, who had tried to prevent his daughter from marrying Rick because he wasn't Jewish.

The most vexing issues for many interfaith couples center on child rearing. "The arrival of a baby," notes Glaser, "forces parents to confront their religious legacies, to reconsider decisions made long ago and to revisit the spiritual dilemmas of their own youth." Glaser's couples reflect this turmoil. In one scene, a Jewish man who married a Catholic sits somberly in the pew watching as his wife holds their son at the baptismal font. Later he confides to her, "When I saw you up there, I felt all the love I had for you and Zachary drain out of me."

"The arrival of a baby," notes Glaser, "forces parents to confront their religious legacies, to reconsider decisions made long ago and to revisit the spiritual dilemmas of their own youth." Glaser's couples reflect this turmoil. In one scene, a Jewish man who married a Catholic sits somberly in the pew watching as his wife holds their son at the baptismal font. Later he confides to her, "When I saw you up there, I felt all the love I had for you and Zachary drain out of me."

So how do Glaser's subjects couples raise their children? Every way you could possibly imagine. Some of the couples she profiles are raising them as Jews, others as Christians. Many attempt to expose their children to both parents' religions. ("Although Zack and Danielle go to Sunday school and love Christmas and Easter, they also light candles . . . on Friday nights.") One couple has even chosen to raise their first child Catholic (Catholic school, first communion at age 8) and their second child Jewish (Hebrew school, bar mitzvah at age 13). "The kids could become confused at some point," the father allows.

"The kids could become confused at some point," the father allows.

The most engaging story in Glaser's book is her own. She was raised as a Protestant in the small farm-and-mill town of Albany, Ore., but felt distanced from her more devout peers. From an early age, she was fascinated by modern Jewish history, notably the Holocaust and the massacre of 11 Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics. She later married a Jew and embarked on an investigative journey that indicated her great-grandfather was a Polish Jew. She ultimately converted to Judaism, a move that "stunned, hurt and disappointed" her mother.

As a result, Glaser's mother wondered how she had failed to give her kids a stronger faith. "She had the wrong question, I thought," Glaser writes. "It was exactly what she'd done right, in exposing us to other cultures, in fostering understanding and in imbuing us with a need for religion that made me seek my own."

The author is equally sanguine about the future of American Judaism, dismissing arguments that interfaith marriage will be its undoing. "Judaism survived the travails of exile in Egypt, forced conversion in Spain and the Holocaust," she writes. "It will surely survive modern intermarriage."

"Judaism survived the travails of exile in Egypt, forced conversion in Spain and the Holocaust," she writes. "It will surely survive modern intermarriage."

Charlie Gofen, '87, is a frequent contributor to Stanford.

I Married a Jew - The Atlantic

“‘Mother,’ I said quietly, ‘remember the greatest Man who ever lived was a Jew – Jesus.’ That held her for a minute. ‘Yes,’ she murmured, ‘it is the great paradox.’”

By Anonymous[Editor's note: This article was published in January 1939.]

My husband's father and mother are Jews. My parents are both what Mr. Hitler would be pleased to call 'Aryan' Germans. I am an American-born girl, and the first to defend my Americanism in an argument; yet so strong are family ties, and the memory of a happy thirteen-month sojourn in the Vaterland a few years ago, that I frequently find myself trying to see things from the Nazis' point of view and to find excuses for the things they do—to the dismay of our liberal-minded friends and the hurt confusion of my husband.

Here we are then, Ben and I, a Jew and a German-American, married for four years, supremely happy, with a three-year-old son who has his father's quick brown eyes and my yellow hair. Ours was a fervent love match, made more fervent by the fact that we had to wait in secret for two years until Ben earned enough at his profession to support a family. He had known other girls and, as I was twenty-five before we married, I had had my share of other men's attention. Consequently our marriage was not the hasty, impassioned leap of two people soaring on the Icarian wings of a first love. That which was between us was calm as the night, deep as the sea; in the light of it we both knew that forever afterwards he would look upon other women, and I upon other men, as pale wraiths. We determined that no obstacle should prevent our union, and obstacles there were a-plenty as soon as our families learned our intention.

'Child,' entreated my mother, who deep in her heart had always hoped that what she referred to as my superior intelligence, careful upbringing, talents, and attractiveness, would land me a husband well up in the social levels, ‘bethink yourself what this means. Married to a Jew, you will be barred from certain circles. They can say what they like about Germany, but democratic America is far from wholeheartedly accepting the Jews. Remember that Ben couldn't join a fraternity at his university. Remember there are clubs and resorts and residential districts that bar Jews. Remember there are a dozen other less tangible discriminations against them.'

Married to a Jew, you will be barred from certain circles. They can say what they like about Germany, but democratic America is far from wholeheartedly accepting the Jews. Remember that Ben couldn't join a fraternity at his university. Remember there are clubs and resorts and residential districts that bar Jews. Remember there are a dozen other less tangible discriminations against them.'

'That makes not a whit of difference, to me,' I stubbornly maintained. 'I love Ben. I'd marry him if he were a Hottentot.'

'But, child, remember the racial and religious differences between you. Remember that your children will be pulled in two different directions.'

Ben's mother and father attend an orthodox synagogue, observe the dietary rules and all the ritual holy days. Ben, however, like a large percentage of modern and intelligent young Jews, looks with affectionate tolerance on these parental habits but eschews them for himself. He goes to synagogue on Rosh Hashana to please his mother, and during the rest of the year wavers between agnosticism and downright atheism.

All this I pointed out to my mother, adding, 'Ben does not ask me to cook kosher, if that's any comfort to you. And remember that, although I love the teachings of Jesus, I belong to no sect or church. It's not as if the shadows of a priest and a rabbi stood between us.'

Then my mother pulled out the oldest and bitterest chestnuts that have been hurled against the Jews, accusations as old as the Roman Empire.

'The Jews are essentially an Oriental race,' she stormed, 'East is East, and Jews and Christians cannot really meet any more than Christians and Chinese. Jews are sensual, aggressive, ostentatious, cunning—that is a heritage they can never overcome. They accomplish things in business because they are shrewder than Christians and never hesitate to seize an unfair advantage. They accomplish things in science yes, but mostly windy theories like those of Einstein and Freud. Jewish painters like Picasso and Modigliani are clever but never great. Jews in the theatre—well, you have seen what they have done to Hollywood. The moving pictures are full of sex and sensuality, and cater solely to the Jews' god, money. Has there ever been a Jew who could approach Beethoven or Raphael? Has there ever…’

The moving pictures are full of sex and sensuality, and cater solely to the Jews' god, money. Has there ever been a Jew who could approach Beethoven or Raphael? Has there ever…’

It must not be inferred that Mother, because of her German background, was particularly anti-Semitic. I have heard the same things from the lips of plenty of one-hundred-per-cent Americans,

'Mother,' I said quietly, 'remember the greatest Man who ever lived was a Jew—Jesus.' That held her for a minute. 'Yes,' she murmured, 'it is the great paradox.'

'And other great Jews,' I added quickly. 'Spinoza, for instance, and Epstein.'

Mother looked at me a little sadly. She wasn't licked, but she was for the moment out of arguments.

What Ben's mother said to him I can only conjecture, for he has never told me. 'Ben,' she most likely said, 'it grieves my old heart to have you marry a Shiksa rather than one of us. The old persecutions are rising again throughout the world. We have need, as never before, to stick to our own people and traditions. '

'

But, loving Ben above the rest of her children, she probably also said, 'Well, then, if you love her and are sure that she is the one woman for you, you have my blessing. Above everything I want you to be happy.'

Our mothers met, embraced, and promptly forgot their differences in purely feminine discussions of wedding plans (we were to be married by a civil judge to eliminate difficulties), motherly landings of their respective offspring, and the honeymoon. Once marriage loomed up as a certainty, not another word against Ben's race or religion escaped my mother's lips. She could have maintained this negative attitude and still have preserved the family peace. But gradually, as she learned to know Ben better and saw how fine he was, and how good to her daughter, there came shy words of affection and admiration.

'He's a fine young man with a great future,' I hear her tell her friends, with pride in her voice. 'The Jews make excellent husbands; so I've always maintained. '

'

'But,' she always adds, 'I am happy to say Ben is not at all Jewish in his make-up. He doesn't look Jewish and his ways are not Jewish, In fact, you wouldn’t think he was a Jew at all.'

Naturally, to our friends, the most interesting aspect of our marriage is its interracial side, I know that even now many of them, aware of my pro-German leanings, still chuckle behind our backs; 'Well, well, our little Nazi Gertrude had to go and marry a Jew, of all people.'

At, one time at another almost every one of my intimates has asked me sotto voce, ‘What is it like, living with a Jew? Is he very Jewish? Do you ever discuss the differences between you?'

It was this that finally propelled me to our typewriter—to tell the world how it really is between a Jew and a Christian, since the world is evidently so intensely interested. I wish I could say that, because Ben and I have worked through to complete happiness, there is no reason why Jews and Gentiles everywhere cannot live peaceably and happily side by side. But I am afraid that this harmonious relationship can come about only when Gentiles stop being one-hundred-per-cent Gentiles and Jews one-hundred-per-cent Jews—when both sides drop their false pride of race, their hidebound, worn-out, traditions, and meet each other halfway.

But I am afraid that this harmonious relationship can come about only when Gentiles stop being one-hundred-per-cent Gentiles and Jews one-hundred-per-cent Jews—when both sides drop their false pride of race, their hidebound, worn-out, traditions, and meet each other halfway.

Yes, we discuss our differences. Our discussions are not frequent because I seldom think of Ben as being Jewish, and he seldom thinks of me as a Gentile. We are just Ben and Gertrude to each other. It is that way when you love. But when we do have discussions we fire away freely. I know that in many Christian-Jewish alliances it is thought wiser and more conducive to marital harmony to treat these differences as nonexistent, to shroud them in a veil of silence. Ben and I have always looked upon this as an unhealthy practice. To throttle a subject and make it forbidden, we think, leads to distortion and often to explosion.

However, in our discussions, it is always I who must choose the more tactful way, for Ben, poor darling, still has the Jewish hypersensitivity toward all criticism of his race, for which he and his people are not to be blamed. In the beginning he couldn't take it at all, though he loudly proclaimed that he invited argument, that he wanted to learn the Christian point of view in order to understand more clearly the century-old friction between the two groups.

In the beginning he couldn't take it at all, though he loudly proclaimed that he invited argument, that he wanted to learn the Christian point of view in order to understand more clearly the century-old friction between the two groups.

All right, we would have at it. He would start by saying there was this and that about the Christians that he never could stomach. I would agree with him or condone the matter as the case might be, then point out a few Jewish traits that have irritated Gentiles. The moment I did that, he began to look like a crushed and visual embodiment of the 'Eli, Eli.' The least word against anything Jewish he took as a personal criticism of himself. 'Ben, dear,' I told him, 'when you attack the prevalence of crime in America, do you suppose I think that you are implying that I am myself a criminal?' It took some little time to drive this point home. But then up shot another one. Every criticism of Jewry was a vaunting of Christian superiority. 'In their hearts most Christians think of us as "dirty Jews,"' he mourned.

And I had to comfort him: 'Ben, if I say the English are too smug, the Germans too clumsy and pig-headed, the French too material, does that mean that I see no good in them at all, that I call them "dirty English" or "dirty French" or "dirty Germans"?' That too, took time to penetrate.

Of course we argue about religion. I have been to synagogue with him on the day when he goes, Rosh Hashana. I have found the singing, the music, and the preaching fine, and not so different from Catholic or Episcopal services. I find little difference between Catholic saints and Jewish angels, between the miracles encountered by Moses and Elijah and those by Jesus. I have admitted that I found strange, and a little comical, the presence of men in black derbies at the altar, the squeaky notes of the Shofar, or ram's horn, the continuous giggling and gossiping throughout the long services (Ben has told me you cannot expect people to keep quiet for six hours at a stretch), the absence of that reverent hush that makes the Catholic or Episcopal service inspiring.

For his part, Ben finds genuflections, incense, the intricacies of the Mass, choir boys, processions, holy statues, holy water, and prayers to Christ as a divinity, equally strange, he does not understand how anybody can believe in the Immaculate Conception and the Virgin Birth of Jesus.

'Well,' I parry, 'but you believe that the Jews, and nobody else, are God's chosen people. That sounds funny to us.'

My personal belief, which really has no place here, is that these are symbolical rather than literal truths. To me the Immaculate Conception and the Virgin Birth mean that the Christ consciousness can be born only in the heart that is immaculate and pure, even as 'Israel' means any and all who live in the ways of God.

Ben says there may be something in that, but he does not really believe it because he is not at all sure there is a God.

Again, I must tread softly when we talk about religion because, while Ben thinks it perfectly enlightened and proper to ridicule the various aspects of Christian religions, his lips clamp shut when I venture to suggest that Judaism is at least as dogmatic as Catholicism and as jealous of its own, that the Jewish church plays politics quite as much as Rome, wields an international influence equally strong, and, to an avowed agnostic like himself, should present at least as much ritual balderdash—the prohibiting of milk or butter at a meal where meat is eaten, the wearing of prayer shawls and hats by men worshipers at services, the tearful wailing of the cantor, the swaying back and forth of the worshipers at synagogue prayer. No, Ben is not a churchgoer, but instinct says that the Jewish church is of his people and as such should not be ridiculed or criticized.

No, Ben is not a churchgoer, but instinct says that the Jewish church is of his people and as such should not be ridiculed or criticized.

Like most Gentiles, I read both the Old and the New Testament of the Bible, but neither Ben nor any of his Jewish friends have, so far as I can ascertain, ever honored the New Testament with so much as a glance. I find much in the Old Testament to make me understand the Hebrew character, and I believe a Jew could find much in the New Testament to help him understand the Christian character, though he does not believe in the divinity of Christ, and though he may not believe that Christ ever trod this earth. Even if the New Testament were sheer fantasy, Saint Matthew and Saint Luke speak as much wisdom as Moses or Solomon.

Ben will often excoriate a member of his race—and he disagrees with those who hold that the Jews represent a religion rather than a race. As he points out, you can baptize a Jew and turn him into an outward Christian, but you cannot take away his feeling for his people, his racial appearance, or his tastes.

Ben will often call Mr. Finklelteinier or Mr. Salornor a 'rat' if he sees fit. But if I should do the same he would not like it. He does not care for the Eddie Cantor programme; I do. He likes the Walter Winchell programme, and I don't. But if I say I don't like Walter Winchell he thinks it is because Winchell is a Jew. Ben's family beams whenever there is mention of such great Jews as Einstein, Epstein, Freud. They nod and smile as if to say, 'Ah yes, where would the world be today if it had not been for our Jewish greats?' But never do you hear them speak of Jewish scoundrels or criminals. If you merely mention that So-and-so is a Jew, they suspect you of anti-Semitism.

Often Ben voices the age-old complaint of his race: the Gentiles think they are superior to the Jews. Face to face, they are polite to the Hebrews, take their money, hold jobs in their firms, buy from Jewish stores, eat at the tables of Jewish friends—then turn around to snicker and sneer behind their backs. This is true, I admit it to Ben, terribly true and terribly wrong, and certainly one of the major causes for the centuries-old friction between the two races. But then, conversely, it is also true of the Jews. They, in their turn, think they are immensely superior to the Gentiles. If they did not think so, would they still remain Jews after generations of living among Gentiles? Even Ben frequently lets slip the opinion that Jews are much smarter than Christians. And who among the Jews will deny that, while he also does business with Gentiles, eats at their tables, and calls them friend, he also goes away privately rejoicing in his superiority?

This is true, I admit it to Ben, terribly true and terribly wrong, and certainly one of the major causes for the centuries-old friction between the two races. But then, conversely, it is also true of the Jews. They, in their turn, think they are immensely superior to the Gentiles. If they did not think so, would they still remain Jews after generations of living among Gentiles? Even Ben frequently lets slip the opinion that Jews are much smarter than Christians. And who among the Jews will deny that, while he also does business with Gentiles, eats at their tables, and calls them friend, he also goes away privately rejoicing in his superiority?

Unfortunately the Jewish publications and the church are not so private about it; they openly vaunt the superiority of their race and do not mince words when it comes to criticizing the Goy in whose land they live. And so the friction has continued through the ages, both sides firmly entrenched in self-righteousness. And so the friction will continue, now dormant, now bubbling uneasily, now flaring into riots and persecutions.

Ben is willing to concede that if it is true that Christians, in the mass, have seldom tried to understand the Jews, to read what they have written about their predicament, it is also true that the Jews have not tried to understand the Christians and to meet them halfway. The Jew seldom tries to mingle with the masses. Because of his religion and his traditions he is content to live a life apart from the community, And when persecutions come he bows his head and says it is the will of God.

Ben's family speak not without a certain pride when they allude to the curse of Israel and call themselves the martyred race. They honestly regard themselves as holy victims. They are only too willing to tell you what is wrong with the Gentiles, but neither in the family nor among other Jews have I met one who is willing to admit that some repairs might also be made in the house of Israel. Almost any intelligent Gentile will admit that our attitude toward the Jews has often been unjust and shameful, though, making the admission, we do nothing at all about it.

However, it seems to me that, since both cannot be right in this quarrel of the centuries, adjustments must be made on both sides, and so I tell Ben. We must root out our groundless and arrogant feelings of superiority. They must pluck out the fixed and mystical idea that the Jew is forever doomed to be a wanderer and accursed; instead of turning their faces to the Wailing Wall every time sparks of the ancient friction catch fire, they must make some practical and rational effort to adapt their ways more graciously to the Gentile pattern, since they prefer to live in Gentile lands.

Our hottest argument concerns the question whether there exists such a thing as a Jewish problem. Ben is ready to discuss the separate differences between Jews and Christians, but when I lump them all together as constituting the world's Jewish problem he flares up. Oh, there's a problem all right, he allows, but it concerns only the Jews, and he'd thank the Gentiles to mind their own business and keep their hands off. To which I reply, 'How can we ignore it when it concerns us as much as the Jews? How can the host ignore the quarrels of the guest in his house?' To which Ben answers with some heat; 'We are not guests; we are good citizens of the countries in which we live.'

To which I reply, 'How can we ignore it when it concerns us as much as the Jews? How can the host ignore the quarrels of the guest in his house?' To which Ben answers with some heat; 'We are not guests; we are good citizens of the countries in which we live.'

Here the fencing really becomes fast and furious. 'What constitutes a first class citizen?' I ask. The answer, according to Plato, is one who places his country and that country's interests above his owns. Is that true of the Jew? Barely. Instinctively he desires first the welfare and advancement of his own people. So long as a country gives him a living and lets him alone, he doesn't much care what happens to it. When things go well, he stays; when things go wrong, he packs up and moves to another country. Where is the Jew who says, 'My country, right or wrong'?

'All right,' says Ben, 'but can you blame us? Outside of England and America, what country has ever made us feel we could belong?'

'You are right,' I reply, 'and I don't blame you. I should feel the same if I were Jewish, But what does this prove? That a Jew is, with few exceptions, first a Jew, and second a citizen of the country where he happens to pitch his tent. After two thousand years of living with Gentiles he still retains his identity as a Jew—as an alien, if an alien means one who has not been absorbed into the main stream. It is certainly not a different religion that has kept him alien, nor a prominent nose. There are plenty of Gentiles with prominent noses, and the difference between the Jewish church and, say, the Catholic is no greater than the difference between the Catholic and the Greek Orthodox church. No, what keeps the Jew alien is his alien culture, his alien tradition, his fierce pride in belonging to what he believes a superior race.'

I should feel the same if I were Jewish, But what does this prove? That a Jew is, with few exceptions, first a Jew, and second a citizen of the country where he happens to pitch his tent. After two thousand years of living with Gentiles he still retains his identity as a Jew—as an alien, if an alien means one who has not been absorbed into the main stream. It is certainly not a different religion that has kept him alien, nor a prominent nose. There are plenty of Gentiles with prominent noses, and the difference between the Jewish church and, say, the Catholic is no greater than the difference between the Catholic and the Greek Orthodox church. No, what keeps the Jew alien is his alien culture, his alien tradition, his fierce pride in belonging to what he believes a superior race.'

'Well,' argues Ben, 'suppose my people are what you call aliens. What is to prevent them from living with others in peace, so long as they behave themselves? And most Jews do behave themselves. Shall not the lion lie down with the lamb?'

From a moral standpoint, Ben is completely right. It is sad and unjust that, the world over, the alien thing is regarded with suspicion. Because it is 'different' it cannot be as good as the familiar. It is the butt for the jibes of the narrow-minded, for the deprecation of the smug.

It is sad and unjust that, the world over, the alien thing is regarded with suspicion. Because it is 'different' it cannot be as good as the familiar. It is the butt for the jibes of the narrow-minded, for the deprecation of the smug.

'But look at the matter from the political side,' I advise Ben. 'When a Swede or a Chinese settles down in a foreign land, such as the United States, the Swede makes haste to become a thorough American—at any rate he lets his children become thorough Americans; the Chinese, realizing that this is impossible, lives aloofly in Chinatown, minds his own business, and keeps out of American political affairs. The Jew, however, wants to have his cake and eat it, too. Like the Chinese, he clings to his own race, culture, and tradition; he trains his children to cling to these just as tenaciously. Then, like the Swede, he sets out to annex all the privileges of Americanism. He wants to rise to the top of the Gentile social structure, to wield power in Gentile politics of the community, state and nation. He wants to be left alone, but he also wants the country in which he lives to take good care of him. He wants to have full citizenship in that country, yet retain his citizenship in the Jewish nation.

He wants to be left alone, but he also wants the country in which he lives to take good care of him. He wants to have full citizenship in that country, yet retain his citizenship in the Jewish nation.

'Certainly it is sanctimonious for society to reject him, I admit, to resent his success in business and the professions, his dabbling in politics, his strong international alliances. No one can deny that the Jew is often more brilliantly talented in these pursuits than the Gentile. Why should he be punished for his intelligence? The answer is simply that human nature resents the ascendancy of the alien. So long as the Jew wears the cloak of alien colors, so long will his predominance in any tier of the Gentile structure be resented.'

After we get this far, Ben inquires: 'You seem to be able to dissect the problem, but can you construct a solution?'

'Yes,' I answer, 'but it's only my personal opinion, and probably not worth much.'

'Well, let's have it,' he growls. And I tell him: the Jews must come off the fence and make up their minds whether they want to be primarily citizens of, say, France or England or primarily citizens of Jewry. They cannot be Jewish in their homes and French or English outside. They cannot pledge their pride and loyalty to Israel and expect Frenchmen and Englishmen to treat them exactly like other Frenchmen and Englishmen. If they decide it is more important to preserve the Hebrew culture, tradition, and pride of race, then they must accept more graciously the distinction accorded them as aliens. In that case they would encounter less friction if they adhered to their own society, community centers, clubs, and so forth. At the same time, we on our side should give them the greatest respect as remarkable and admirable aliens. We must conquer our own feelings of superiority and learn to regard and treat them as our equals, for that they certainly are.

They cannot be Jewish in their homes and French or English outside. They cannot pledge their pride and loyalty to Israel and expect Frenchmen and Englishmen to treat them exactly like other Frenchmen and Englishmen. If they decide it is more important to preserve the Hebrew culture, tradition, and pride of race, then they must accept more graciously the distinction accorded them as aliens. In that case they would encounter less friction if they adhered to their own society, community centers, clubs, and so forth. At the same time, we on our side should give them the greatest respect as remarkable and admirable aliens. We must conquer our own feelings of superiority and learn to regard and treat them as our equals, for that they certainly are.

On the other hand, if they decide that they would rather be entirely one with us and be treated as such, they must throw off a large share of their (to Gentiles) dead and outmoded culture and traditions, their false pride of race. The Hebrew religion must be divorced from the promulgation of that race consciousness which every synagogue and temple considers as important a part of Judaism as prayer; it should be mortified at least to the point where it does not belittle the great ideal of western culture and civilization: Christ.

'But,' demurs Ben, 'some of us have tried to become Gentiles at various times in history. We have changed our names, even our religion, and we have not been accepted.'

To this I can only answer: 'True, the prejudice of Gentiles against Jews in ages past has been a two-edged sword that has knifed the Jew when he has left his race as well as when he adhered to it. But I also maintain that there have been periods when almost all doors have been opened to Jews—a period in Poland, a period in Austria, and most notably, a liberal period in England which culminated its the rise of the Jew, Disraeli, to the post of Prime Minister.

'Had the Jews seized these opportunities for amalgamation, eventually all the barriers would have been broken down. But the Jews did not seize the opportunity. They chose to retain their identity and remained in intact as before. Today it is America that is offering the children of Israel the greatest opportunity in history for absorption. Intermarriage between Jews and Gentiles, business partnerships, and Jewish statesmen excite no more than passing comment. A few barriers remain, but they could be made to break like straws in this young, iconoclastic land. And still the synagogues and temples exhort their flocks to remember that they are Jews, that they have been Jews for 4000 years and, please God, will still be Jews 4000 years hence. A few cultural, intellectual Jews announce they are first Americans and then Jews, but they are voices crying in the wilderness.'

A few barriers remain, but they could be made to break like straws in this young, iconoclastic land. And still the synagogues and temples exhort their flocks to remember that they are Jews, that they have been Jews for 4000 years and, please God, will still be Jews 4000 years hence. A few cultural, intellectual Jews announce they are first Americans and then Jews, but they are voices crying in the wilderness.'

Of course we eventually come to Hitler, Ben and I. In the eyes of Ben, as in the eyes of all his people, Hitler stands for the Jewish equivalent of the Antichrist—a little, strutting monster whose sole purpose and pleasure in life is to flog, imprison, impoverish, humiliate, and plague Israel. Few history books trace the path of persecutions against the Jews as they have occurred throughout the ages. They have occurred in ancient Rome, Poland, Russia, Spain, England, and France, usually whenever Jewry becomes too numerous and too powerful, whenever it becomes, in the eyes of Gentiles, a threat, potential or actual, to Gentile supremacy. I try to tell Ben that Hitler is merely writing another page in a history that will continue so long as the status quo between Jews and Gentiles remains—a status that only the willing shoulders of both protagonists can remove.

I try to tell Ben that Hitler is merely writing another page in a history that will continue so long as the status quo between Jews and Gentiles remains—a status that only the willing shoulders of both protagonists can remove.

But it is hard for Ben to take the long view. He looks upon Hitler as something malignantly unique, and it is no use trying to tell him that a hundred years hence the world will no more call Hitler a swine for expelling the Jews than it does Edward I of England, who did the same thing in the thirteenth century—an expulsion that remained in strict effect until the time of Cromwell, because a hundred years hence another country will be having its Jewish problem, unless…

It must not be inferred that because my husband and I have these discussions our domestic life is one long dialectic on the differences between Jews and Gentiles. Our arguments are comparatively rare, because they are not prohibited by false feelings of tact, and, like fruits that are not forbidden, they hold no more than casual allure. We argue when we feel impelled to do so, when we read or hear something that touches the vital nerve of the Jewish-Gentile problem. The rest of the time we lead the even-toned lives of two people who are happily married and deeply in love.

We argue when we feel impelled to do so, when we read or hear something that touches the vital nerve of the Jewish-Gentile problem. The rest of the time we lead the even-toned lives of two people who are happily married and deeply in love.

Since I am writing about Ben as a Jew, I should describe one of his traits—his pride in his non-Jewish appearance, mannerisms, and surname. His father changed the unpronounceable last name to something more Anglicized. People have known Ben casually for two or three years without discovering he was Jewish. It pleases him that he looks and acts like other people. His friends are preponderantly Gentile, not for reasons of expediency, but because, he says, 'We modern Jews ought to work out of our narrow, clannish ways and become more at one with the rest of the world. The Ghetto no longer exists in the physical world, but it still walls in the minds of too many of our older people.'

It is only when Ben is surrounded by his family that he lapses into Jewish ways, and then, no doubt, because of his early Jewish training. The family are extremely clannish. Every Sunday and holiday they gather in the home of this or that member. Vacations, too, instead of being spent in the mountains or at the shore, getting away from relations, are spent visiting one another. They over whelm me with kindness, urge me to enter more fully into the family life. This goes against the grain for several reasons. In the first place, my own family relations have always been more or less casual, and I lack entirely the clannish instinct. Moreover, deny it as I will, seek to overcome it though I try, there is something a little 'alien' in the atmosphere for me where so many orthodox members of Israel are gathered together, even though they are my husband's kin and blood. Separately I am fond of them; individually I welcome them to my home; but in a large group of them I feel like a fish out of water.

The family are extremely clannish. Every Sunday and holiday they gather in the home of this or that member. Vacations, too, instead of being spent in the mountains or at the shore, getting away from relations, are spent visiting one another. They over whelm me with kindness, urge me to enter more fully into the family life. This goes against the grain for several reasons. In the first place, my own family relations have always been more or less casual, and I lack entirely the clannish instinct. Moreover, deny it as I will, seek to overcome it though I try, there is something a little 'alien' in the atmosphere for me where so many orthodox members of Israel are gathered together, even though they are my husband's kin and blood. Separately I am fond of them; individually I welcome them to my home; but in a large group of them I feel like a fish out of water.

I can never quite put my finger on the reason for this. It is not the fact that Yiddish words like meshuge and zimmis and chassah fall plentifully into the conversation. It is not the continuous babel of voices—many of my friends chatter more, Nor is it the Jewish intensity of outlook which lacks what we call broad-mindedness, because I know other people who are not broad-minded.

It is not the continuous babel of voices—many of my friends chatter more, Nor is it the Jewish intensity of outlook which lacks what we call broad-mindedness, because I know other people who are not broad-minded.

I think—if I can express it—it is the fact that they make no concession to me as a Gentile. They pass that fact over as if it did not exist. They go about their Jewish ways, tales of their Jewish problems, and consider me aloof if I do not enter whole-heartedly into all this and become as one of them. Out of courtesy I try to do as they do when I am among them, but their not reaching out to meet me halfway becomes a strain after a while. The result has been that I cut down my visits to a minimum; and in fairness I pare down my husband's visits to my own family to the same minimum. This is the one compromise my husband and I have reached by tacit understanding rather than by open discussion. You can discuss abstract problems, no matter how delicate; but, when it comes to anything as concrete as the family, the fewer the spoken words, the wiser, as any married couple knows.

The moment Ben is away from his family, his Jewishness drops away from him like a cloak. Not that his non-Jewishness then becomes another cloak. It is, I think, far more his real attitude than the other than the other, which is a relic of his childhood; for Ben is one of those who feel themselves first Americans, then Jews.

For all that, however, before our baby was horn Ben announced one day that if it were a boy he would like to have it brought up as a Jew. If it were a girl, then I could 'stuff it full of Christian beliefs.' And he did not mean this unkindly.

‘But, Ben,’ I asked, ‘why if it is a boy, do you want to make him race-conscious? You do not believe actively in the religion, and you say that most of the Jewish traditions are as unrelated to modern life as those of the ancient Christians.'

'Well—er,' he fumbled, 'well, I was born a Jew, and I went to Hebrew school, and—er—well, I want him to be like me.’

But it eventually turned out that his real wish was to please his mother. What that man wouldn’t do to please his mother! Of all sons, surely the Jews are the best and the most loyal. But when I pointed out to Ben that it was I, the baby’s mother, who would have the upbringing of the child, that what the child learns at its mother’s knee sinks in far deeper than what would be superimposed at Hebrew school, and that I, who am not versed in Judaism, could hardly be expected to teach it to the child—then he gave up on the idea.

What that man wouldn’t do to please his mother! Of all sons, surely the Jews are the best and the most loyal. But when I pointed out to Ben that it was I, the baby’s mother, who would have the upbringing of the child, that what the child learns at its mother’s knee sinks in far deeper than what would be superimposed at Hebrew school, and that I, who am not versed in Judaism, could hardly be expected to teach it to the child—then he gave up on the idea.

It is a curious thing that the most pronounced agnostics or atheists nevertheless want their children to grow up believing in ‘something.’ And that was the way with Ben.

'Ben,' I said, 'you don't believe in anything. I believe in the teachings of Christ as well as in the teachings of the Old Testament. You have admitted that His teachings sound beautiful, even if you do not believe He ever lived. Then, since I believe in Him so strongly, let me teach to the child His precepts without the formulas of any religion. Let me also teach him the beauty of the Psalms of David, the wisdom of Solomon, the inspired sayings of Elijah and Samuel and Isiah. I shall teach him that Solomon and David and Jesus are all of the same illustrious race as his father, that to belong to that race is something to be proud of—when that feeling does not become overemphasized.’

I shall teach him that Solomon and David and Jesus are all of the same illustrious race as his father, that to belong to that race is something to be proud of—when that feeling does not become overemphasized.’

Ben beamed. ‘Yes, that’s it. That’s about right.’ And so it has been with our little Joseph.

When one of my husband-hunting girl friends asks me, ‘Do the Jews make good husbands?’ I think of Ben, respecter of women, generous to a fault, kind to every creature, open-minded, witty, sober of habit but gay of manner, imaginative and ambitious, and say with all my heart, ‘The best in the world!’

"We will circumcise our son and baptize our daughter." How mixed families live - Snob

Society

Anna Alekseeva

More than a million marriages are registered in Russia every year. However, statistics do not take into account what religion the spouses adhere to. There are about 15 million representatives of religious minorities in Russia - Muslims, Buddhists, Catholics and Lutherans. "Snob" found out why a Jewish woman is better off with a Muslim than with an Orthodox one, and what a Catholic mother-in-law and a Buddhist mother-in-law will never give the go-ahead to

There are about 15 million representatives of religious minorities in Russia - Muslims, Buddhists, Catholics and Lutherans. "Snob" found out why a Jewish woman is better off with a Muslim than with an Orthodox one, and what a Catholic mother-in-law and a Buddhist mother-in-law will never give the go-ahead to

10 July 2017 11:03

Avigal, 25 years old, teacher, Krasnoyarsk:

I am a purebred Jew. My maternal relatives fled Poland during the Holocaust.

Almost 29 years ago my mother came from Zheleznogorsk to Krasnoyarsk to enter the university. There she met her father, an Orthodox Tatar, they were on the same mountain tourism team. Dad was married then, but fell in love with mom. Dad's relatives at first were not happy with the new marriage: mom was 19, dad is already 30, besides, mom is from a Jewish family, although not religious. My grandmother also did not accept my father, but not because of religion, but because he made unkind jokes about the Jews. By the way, now the grandmother does not have a soul in dad.

By the way, now the grandmother does not have a soul in dad.

When my mother married my father, she wanted to observe Jewish rites, but my father was against it: he did not particularly like Jews, although he married a Jewish woman. I think that my mother should have stepped over everything and went to the synagogue. But she was young, succumbed to the influence of her father, and then she didn’t care.

When they told me that I was Jewish, I became interested and started studying Torah and going to the synagogue. At the age of 13 she began to wear the Star of David. Dad was against it. He said that I had nothing to do. When his friends asked him what this daughter was wearing around her neck, he said that the Jews were luring me to their place. Over time, dad came to terms with the fact that I chose my birth path. When I visit him for the weekend, he asks how things are in the synagogue. Jokes about Jews sometimes slip through him, but he always apologizes.

At the age of 20, I fell in love with a Muslim Azeri. By the way, Muslims treat Jews a million times better than Christians. Of course, a rabbi will not be friends with a mullah, but ordinary Jews and Muslims can communicate.

By the way, Muslims treat Jews a million times better than Christians. Of course, a rabbi will not be friends with a mullah, but ordinary Jews and Muslims can communicate.

When I fell in love, I had not yet thought about religion: what difference does it make - this is love! We moved in together and lived together for six months, I got pregnant, but we started having disagreements on religious grounds, and we parted.

When his daughter was born, he began to resent. He did not like that his daughter wears the Star of David. I say: what are you presenting to me, we no longer live together!

- I'm a Muslim! Why is she Jewish?

- I'm Jewish, it's passed down from my mother!

- And we have a dad!

— If your wife is Jewish, then the child is automatically Jewish!

Now the father of my child lives in Baku, he does not communicate with his daughter. And I became observant, I work as a kindergarten teacher at the synagogue and give my child what I didn’t get in childhood. The daughter knows that on Friday we light candles, she knows what Shabbat is, when and what prayer to read.

The daughter knows that on Friday we light candles, she knows what Shabbat is, when and what prayer to read.

Now I am for the husband and wife to be of the same faith. Well, either a man should understand who he marries: I am a religious person, when I get married, I will cover my head, and the children will go to the synagogue. If there is a boy, I will definitely circumcise him.

I know Jewish women who are married to Russians. We have circumcision done on the eighth day after birth, and our husbands are hysterical: no, that's all! And what are you going to do here?

Photo: vk.com/followmenatalyNatalia Osmann, 30 years old, co-author of the #FollowMeTo photo project, Moscow:

I am baptized and have been going to church since childhood. I treat faith with respect, but without fanaticism. Before meeting with Murad, I never communicated with Caucasian families, and even more so, I didn’t think that I would marry a Caucasian. I was afraid that Caucasian men were tyrants. But all my fears were only in my head. Once in a Dagestan family, I saw that a woman has great strength and is often more important than a man, it’s just not customary to demonstrate it.

I was afraid that Caucasian men were tyrants. But all my fears were only in my head. Once in a Dagestan family, I saw that a woman has great strength and is often more important than a man, it’s just not customary to demonstrate it.

We are both lucky to have parents. They are very reasonable people. They even go on holiday together. I was very touched that on Easter the whole Murad family congratulated me on a holiday that has nothing to do with them at all: I am the first Orthodox girl in the Murad family.

When I got married, somehow I myself began to dress more modestly. Perhaps Murad even misses the old me. I also have an unspoken rule: when I go to my husband's grandparents, I will never allow myself a neckline. But I decided this for myself. I have not heard anything like this from Murad or his family.

Murad's family has been living in Moscow for 25 years. These are very intelligent and erudite people. Murad has lived in London for many years, he is open-minded in a good way. We respect each other's faith. Only those who do not respect their own religion can afford to disparage the religion of other people. I learned with interest how the Murad family lives, learned new things about religion and culture. Thus, I rose to a new level of spiritual development. Murad and I travel a lot, meet people of different faiths, go to Buddhist temples, mosques, churches, churches, and through this we learn the culture of other countries and peoples. This is a normal healthy relationship between two educated people.

We respect each other's faith. Only those who do not respect their own religion can afford to disparage the religion of other people. I learned with interest how the Murad family lives, learned new things about religion and culture. Thus, I rose to a new level of spiritual development. Murad and I travel a lot, meet people of different faiths, go to Buddhist temples, mosques, churches, churches, and through this we learn the culture of other countries and peoples. This is a normal healthy relationship between two educated people.

We want many children. I joke that the boy will be a Muslim, and the girl will be baptized. But our child will choose what to believe in. We will not impose anything.

We will teach children three points of view: Buddhism, Orthodoxy and atheism. And the choice will be for the children

Alamzhi, 27 years old, businessman, Ulan-Ude:

I am a Buryat from a Buddhist family. My wife is Russian, from an Orthodox family. We ourselves are atheists.

We ourselves are atheists.

My wife and I have been friends since school. When Julia brought me to meet her parents, there were no problems because of faith. I was accepted right away. Now we have two children.

We have different holidays: the Orthodox have Easter, the Buddhists have Sagaalgan. We celebrate this and that. We celebrate Buryat Sagaalgan together with our parents, on Orthodox holidays we try to visit my wife's parents. And so neither my wife goes to church, nor I go to datsan. Children, respectively, too. Orthodox Buddhists don't discuss parenting, they just follow traditions, but my wife and I have a constant dialogue, we always make compromises.

My mother often asks why I don't take my family to the datsan, why I should go and pray. But we don't go. We will teach children three points of view: Buddhism, Orthodoxy and atheism. And the choice will be for the children.

My friend has an orthodox family, where the mother destroyed her son's relationship with a mestizo. The Buryats do not want to interfere with blood because of the difference in mentality. The Buryats are more restrained, less emotional, rarely when the Buryats get into a fight. Russian people are expressive, emotional, can speak rudely, quick-tempered, but very quick-witted. And if you yell at a Buryat, he will take it very close to his heart, because he is not used to being shouted at. The Buryats will be silent for a long time and accumulate discontent in themselves, and then they will explode and will not talk for a long time.

The Buryats do not want to interfere with blood because of the difference in mentality. The Buryats are more restrained, less emotional, rarely when the Buryats get into a fight. Russian people are expressive, emotional, can speak rudely, quick-tempered, but very quick-witted. And if you yell at a Buryat, he will take it very close to his heart, because he is not used to being shouted at. The Buryats will be silent for a long time and accumulate discontent in themselves, and then they will explode and will not talk for a long time.

We have Russian Semey Old Believers in Buryatia, they do not accept mixed marriages at all, even with Orthodox ones. But that's a completely different story. They say that if they give a Buryat a drink of water, then the glass will be thrown away. I haven't seen it myself, but I've been told.

When we decided to get married at a silver wedding, my mother-in-law was categorically against it: this is not our church! We could not disobey

Valentina, 60 years old, pensioner, Kem:

On August 5, my husband and I will celebrate 40 years of family life. I am Orthodox, he is Catholic. In the first place, when they fall in love, they don’t know the history of birth and other things. He is from Belarus. When he was little, his parents took him to church. And he grew up big - he left for Karelia, met me, fell in love, signed, the children went.

I am Orthodox, he is Catholic. In the first place, when they fall in love, they don’t know the history of birth and other things. He is from Belarus. When he was little, his parents took him to church. And he grew up big - he left for Karelia, met me, fell in love, signed, the children went.

There were no questions about what faith to baptize them. Definitely Orthodoxy. The husband did not mind, the mother-in-law did not mind either. One of the daughters was baptized by the father at home.

Now we have 12 grandchildren - all baptized in Orthodoxy. The children called for baptism, the husband went to church. No problem. I have never been to a Catholic church.

We celebrated Christmas and Easter both Orthodox and Catholic. We took turns visiting our parents. The youth then did not particularly adhere to religious holidays, they followed their parents. Now I cook delicious food for his Easter, and for ours.

My husband didn't have any difficulties because of different confessions. Only when we decided to get married at a silver wedding, my mother-in-law was categorically against it: this is not our church! We could not disobey. Now the mother-in-law, the kingdom of heaven to her, is no longer alive, and I again returned to the thought of the wedding. They wanted everything to be beautiful, to go to Petrozavodsk, to the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. But the priest did not approve of our idea. He says that either my husband should come to the Orthodox faith, or I should come to the Catholic one. We dismissed this idea. It didn’t work out for 25 years of marriage, it won’t work out for 40 - well, okay, if only there was happiness in the house!

Only when we decided to get married at a silver wedding, my mother-in-law was categorically against it: this is not our church! We could not disobey. Now the mother-in-law, the kingdom of heaven to her, is no longer alive, and I again returned to the thought of the wedding. They wanted everything to be beautiful, to go to Petrozavodsk, to the Alexander Nevsky Cathedral. But the priest did not approve of our idea. He says that either my husband should come to the Orthodox faith, or I should come to the Catholic one. We dismissed this idea. It didn’t work out for 25 years of marriage, it won’t work out for 40 - well, okay, if only there was happiness in the house!

If you find out that they (women) are believers, then do not return them to unbelievers, for they are not allowed to marry them, and they are not allowed to marry them[2].

Ibn Taymiyyah, may Allah have mercy on him, said: All Muslims are unanimous that a disbeliever does not inherit from a Muslim, and a disbeliever does not marry a Muslim woman[3].

Because Islam is exalted and nothing is above it[4], as the Prophet (peace and blessings of Allaah be upon him) said.

A man dominates a woman, and it is impossible for an unbeliever to dominate a Muslim woman, since only Islam is the true religion.

If a Muslim woman marries a non-Muslim, knowing that it is forbidden, then she is considered an adulterer who deserves punishment. If she did not know about the prohibition of marrying a non-Muslim, then this serves as an excuse for her, but they must be separated. There is no need for a divorce, since the marriage was not originally faithful.

Therefore, a Muslim woman whom Allah has blessed with Islam and her guardian should be wary of this, observing the laws of Allah and being proud that they observe Islam. Allah Almighty said:

من كان يريد العزة فلله العزة جميعا

Whoever craves power (greatness), then power (greatness) belongs entirely to Allah [5].

We advise this woman to stop communicating with this Christian, because a Muslim woman should not have a relationship with a man who is not her own.