Childhood trauma nightmares

Adverse Childhood Experiences and Nightmares

Are you a survivor of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) who has frequent, disturbing nightmares? Know that you are not alone. There is much you can do to alleviate nightmares.

About nightmares

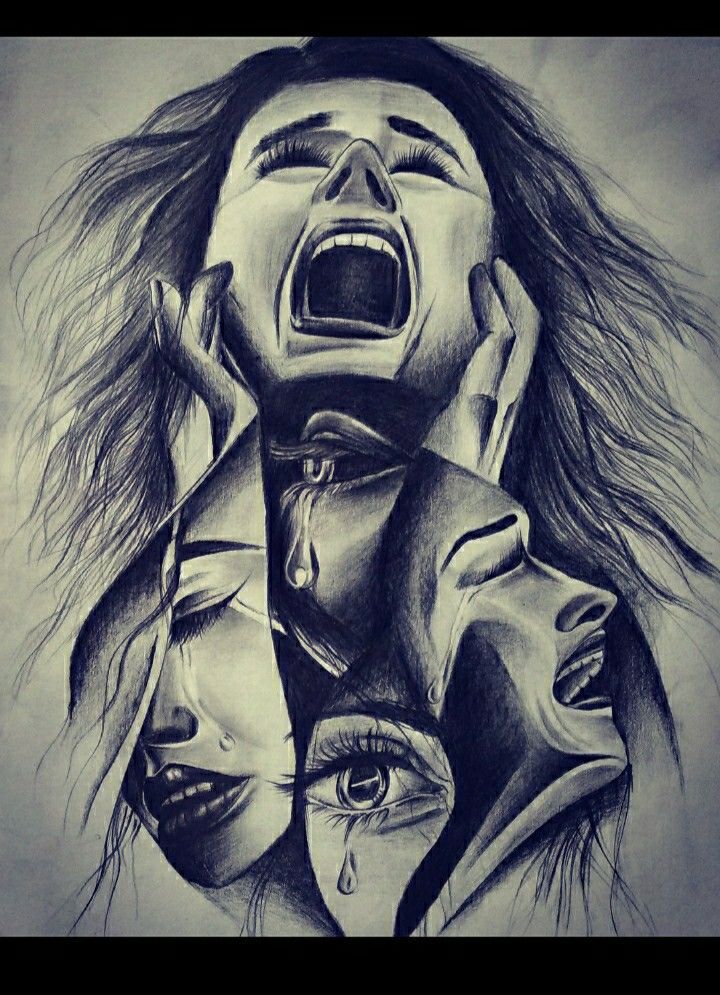

Nightmares.

Source: Vero Vesalainen/iStock Photo

Nightmares disrupt sleep. People might awaken in the night with a racing heart, breathing difficulty, sweating, haunting images, inability to move, and inability to get back to sleep.

Recurring nightmares are obviously distressing and exhausting. They increase arousal and cortisol secretion. The next day, people often feel fatigued and have problems with mood, memory, and performance. Common emotions during and after nightmares include fear, sadness, grief, guilt, shame, and disgust.

Many who suffer nightmares begin to fear going to bed, leading to insomnia. The combination of disrupted sleep and the distress caused by nightmares can increase the risk of several stress-related conditions, such as anxiety and depression.

How Often?

Many ACEs survivors experience nightmares weekly or even more often. Some studies indicate up to 80% of those with PTSD report nightmares that repeat for months or years following a trauma.

Nightmare Content

Nightmares might be literal or symbolic replays of ACEs. Sometimes they seem unrelated to ACEs—perhaps triggered by recent stress and having related themes.

Nightmares signal that there is memory material that the mind is trying to sort out. Normally, dreams help the brain process and settle distressing memory material. However, when people are extremely distressed, dreams can get stuck, replaying without change or resolution.

In addition, nightmares can be re-traumatizing. Like a path worn through a meadow, recurring nightmares reinforce negative neural pathways in the brain. The long-term solution is not sleep medication, but resolving the nightmare and forging new neural pathways.

Settling Nightmares

This five-step process can help you lessen the number and intensity of your nightmares, and perhaps eliminate them. These steps parallel Imagery Rehearsal Training (IRT), which studies have generally found to reduce the frequency and intensity of nightmares, PTSD symptoms, and insomnia and anxiety related to nightmares. These steps avoid the side effects of sleep and anxiety medications, and the benefits are usually long-lasting. It is wise to start with less intense nightmares, and work up to more distressing ones. You might wish to try these steps for a week or two to give them a fair trial. If this process feels overwhelming at any point, enlist the help of a trauma specialist.

These steps parallel Imagery Rehearsal Training (IRT), which studies have generally found to reduce the frequency and intensity of nightmares, PTSD symptoms, and insomnia and anxiety related to nightmares. These steps avoid the side effects of sleep and anxiety medications, and the benefits are usually long-lasting. It is wise to start with less intense nightmares, and work up to more distressing ones. You might wish to try these steps for a week or two to give them a fair trial. If this process feels overwhelming at any point, enlist the help of a trauma specialist.

1. Normalize your nightmares. Acknowledge that nightmares are common and often chronic in ACEs survivors. (However, don’t accept the belief that nightmares can’t be changed.) Think of your nightmares as simply distressing memory material that needs to be processed and settled, not avoided. It is reassuring to realize your nightmares probably contain themes similar to those of people who have also experienced difficult experiences like yours. Dream researchers have described the following common themes in nightmares (Barrett 1996):

Dream researchers have described the following common themes in nightmares (Barrett 1996):

- Danger, terror, death, or fear of death.

- Being chased; being threatened again by a person or event that harmed you.

- Being rescued.

- Monsters (who might chase, harm, or frighten you).

Source: sara5/iStock Photo

- Revenge.

- Failure.

- Being punished.

- Being alone.

- Being trapped, powerless, helpless, or confused (e.g., freezing, can’t protect yourself; being lost).

- Physical injury (e.g., losing teeth might symbolize losing control or being wounded emotionally).

- Filth, garbage, excrement (might symbolize disgust, shame, loss of dignity or meaning in life, or evil).

- Sexual themes (e.g., following abuse, one might dream of good or bad sex, shadowing figures, worms, snakes going into holes, blood, shame, disgust, anger, hurting the assailant, being shunned).

- Violence, gore, killing, injury.

- Relationship conflict.

2. Confide your dreams. The principle of reconsolidation states that when we bring all aspects of a memory to conscious awareness, the brain can change the memory. The goal is to fully describe all the elements of the nightmare in great detail from the beginning to the end to gain the sense that the memory is completed and in the past. You might imagine that you are viewing the nightmare from a safe distance, like watching it on television.

You might describe your nightmare verbally. Telling the story in words can help to neutralize, integrate, and settle a difficult memory. You might relate it to a supportive person. You might also keep a small audio recorder or a journal beside your bed to briefly capture the nightmare. (You might use a lighted pen, so that bright light or blue light from a screen does not prevent you from going back to sleep.) During the day, turn the abbreviated recollections into a detailed narrative.

Relax and describe the following details:

- Facts. What is the setting? Who are the characters: What is happening? How did the nightmare begin and end? What’s the most disturbing part? What are you doing? Are there symbols and what do they represent?

- Bodily sensations. Include inner (visceral) sensations; sounds, smells, tastes, and tactile sensations.

- Feelings, such as sadness or fear.

- Thoughts. What are you thinking?

Some prefer to use artistic expression because the hand can often express what the mouth cannot. You might draw the various phases of a dream on separate sheets of paper from beginning, to middle, to end. You might draw how your body is reacting. The quality of the art is not what counts.

When you are finished describing the nightmare, take a few easy breaths to relax. Then read the description (or describe the drawings) aloud.

3. Rehearse a different, calmer response in the dream. For example, you might imagine calming yourself in the dream by kneading your forearm, breathing slowly, and saying to yourself, “This is just a dream. I’m safe now.” (Some find it helpful to draw the new response.) Before going to sleep, mentally rehearse this new response so that it is in place should the dream recur.

For example, you might imagine calming yourself in the dream by kneading your forearm, breathing slowly, and saying to yourself, “This is just a dream. I’m safe now.” (Some find it helpful to draw the new response.) Before going to sleep, mentally rehearse this new response so that it is in place should the dream recur.

4. Change the nightmare in any way you’d like. You’ll know how. You might change the story and give it a new, positive ending. Write or draw and then talk out what you did to change your dream. Then mentally rehearse in great detail the new dream for five to 20 minutes at least once daily for a week or two. Make sure you actually experience the new images, bodily sensations, feelings, and thoughts. Make sure your new version has a beginning, middle, and end. You might imagine:

- Being rapidly rescued or protected by good and powerful people.

- The assailant caught.

- Healing severe injury by moving your hand over the wounds (anything is possible in imagery).

- Finishing business—perhaps saying what was needed; bidding farewell to loved ones who died and seeing them now well off (for instance, in heaven, smiling).

- Stopping, turning toward the scary monster chasing you, and asking in a friendly way, “What do you want to tell me?” Maybe make it smile, laugh, or dance. Stroke its pain. Or clap your hands and see it disappear.

- A new future, like walking through a peaceful meadow, calmly enjoying the warm sun and the scent of flowers, meeting friendly people, or thinking, “I’m safe and whole now. I survived!”

The only caution is that you not include violence in your changed dream. Violence does not usually settle nightmares.

End the rehearsal with deep relaxation. Tell yourself, “lf any nightmare starts, I’ll soften to it and shift to my newer version.”

5. Expect changes in dream content. As you rehearse different responses and changes to your nightmares, it is likely that you’ll notice shifts in your dream content. Perhaps your dreams of deceased persons now contain assurances that they are well off. Or perhaps your dreams now have other more positive outcomes. Maybe you realize you did your best under those difficult circumstances and simply now feel somewhat better or brighter about the future.

Perhaps your dreams of deceased persons now contain assurances that they are well off. Or perhaps your dreams now have other more positive outcomes. Maybe you realize you did your best under those difficult circumstances and simply now feel somewhat better or brighter about the future.

Note: Research indicates that IRT is superior to medications. You can apply these steps on your own, although structured application with a mental health professional appears to yield even better results.

How to Manage Trauma-Related Nightmares

Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

By Dr. Gabriela Sadurní Rodríguez

With the current climate in 2020, such as COVID-19, the fight against racism and racial injustice (i.e. protests), and Black Lives Matter movement, many people are experiencing an increase in trauma-related nightmares, more anxiety, and many other trauma-related symptoms.

Interestingly, a lot of people go through life-threatening events or potentially traumatic experiences in their lives and successfully recover over time; however, an important minority of people do not recover as easily and develop Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

If you are experiencing trauma-related nightmares, this article is for you.

June is PTSD awareness month!

Did you know that currently there are approximately 8 million people in the United States with PTSD?

People with PTSD can experience a wide range of symptoms like:

- Frequently having thoughts about the traumatic event(s)

- Feeling like they are reliving the traumatic event(s)

- Being constantly on alert

- Being easily startled

- Having increased negative feelings or

- Avoiding triggers that remind them of what happened

Among the re-experiencing symptoms, nightmares are very common. The rate of nightmares in individuals with PTSD can be as high as 72%, while other research suggests that it can range from 71%-96%. Regardless, it is a very high number.

Many people report that their nightmares include:

- Replaying the traumatic experience(s) exactly as it happened

- Going through similar experiences or situations (it can be directly or symbolically related to the event) or

- Having the emotions they experienced when the incident happened

Sound familiar?

“PTSD nightmares aren’t always exact replays of the event.

-Alice CarivSometimes they replay the emotions you felt during the event, such as fear, helplessness, and sadness.”

Impact of nightmares

Trauma-related nightmares generally occur during REM sleep, which is when we tend to have vivid dreams. When you wake up from these nightmares, you may experience fear, anxiety, panic, distress, frustration, or sadness. You can also wake up soaked in sweat and with your heart pounding.

As you may imagine, these nightmares tend to be very distressing. Because they’re so stressful, you may begin to fear going to sleep or attempt to aid your sleep by drinking, using drugs, or using/abusing prescribed medications.

You may also start exhibiting behaviors such as:

- Staying up late

- Leaving the lights or the tv on at night or

- Avoiding sleep as best as you can

Nightmares affect your overall quality of sleep, as it may impact your ability to fall or to stay asleep (which can also contribute to potentially developing other sleep disorders).

Consequently, poor sleep affects all aspects of your life. From your mood (causing irritability and stress) to increased arousal caused by the anxiety. This ends up being a vicious cycle that ends up continuing to affect your sleep and adds to your PTSD symptoms.

The cycle keeps feeding itself because nightmares can be triggered by many factors like stress, sleep deprivation, medications, substance use, and other medical or mental health conditions.

As you can see, nightmares can begin due to trauma and then increase or continue from the side-effects of the nightmares themselves. It can be a complicated phenomenon.

Typically, the first step is addressing the cause of the nightmares (in this case, PTSD).

There are evidence-based treatments for trauma or PTSD that are known to be very effective in reducing symptoms (including trauma-related nightmares; learn more about them here). An individual evaluation would be important to address if medication is necessary and to rule out any health risks.

If trauma-related nightmares persist, here are specific evidence-based treatments to address them:

- Imagery Rehearsal Therapy (IRT) and

- Exposure, rescripting, and relaxation therapy (ERRT).

These treatments share some basic aspects like visual imagery (visualizing a scene or activity in your mind) and nightmare rescripting.

Here is an example of how visual imagery and nightmare rescripting work:

- Think about a nightmare that comes up frequently

(Where are you? What is happening? Who is present?)

- What are you feeling? (during the nightmare and when you wake up)

- How would you like to feel instead?

- How would the story need to change to feel this way?

It’s hard to convey the nuances in this technique. A trained therapist can help you further by teaching you the specific strategies to rescript the nightmares properly (to address the last two points).

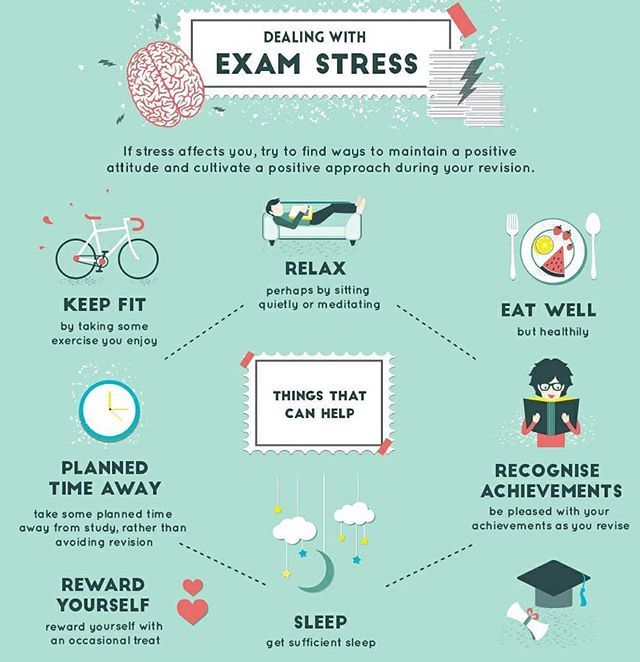

Skills for managing nightmares

Although individual treatment is very powerful in managing trauma-based nightmares, there are skills that you can try yourself. Such as grounding, and relaxation or breathing exercises.

Such as grounding, and relaxation or breathing exercises.

Grounding and Relaxation skills to try yourself:

Grounding techniques are helpful to distract or temporarily get some distance from the distress caused by nightmares by focusing on the present moment.

First, be sure to completely wake up after having a nightmare. The idea is to help you get oriented in the here and now and to re-establish your sense of safety before you go back to sleep (which you can’t really do if you are drowsy or sleepy).

Tip: it is useful to have a nightlight or a lamp near your bedside to aid you in getting oriented in the present moment

After waking up, begin this grounding technique.

It’s all about your senses. Focus on:

- 5 things you can see

- 4 things you can feel

- 3 things you can hear

- 2 things you can smell

- 1 thing you can taste

If you need a little more help, you can follow a grounding technique with a simple breathing exercise.

Breathing Exercise skill to try yourself:

- Start by sitting or lying down in a comfortable position

- When comfortable, gently close your eyes (or set your gaze to a point in your surrounding)

- Inhale through your nose for 4 counts (1-2-3-4)

- Exhale through your nose for 4 counts (1-2-3-4)

- Repeat at least 3-4 times or as needed

If you or someone you know is experiencing trauma-related nightmares, I hope this article has been helpful.

If you’re interested in getting to know more about improving sleep habits and routines (sleep hygiene tips), check out our downloadable document below for more information.

Learn more about PTSD and the treatments we offer here!

Thank you and sleep well!

"*" indicates required fields

License: PY10619

Copyright © 2020 The Psychology Group Fort Lauderdale, LLC

CHILDREN-ADULTS NIGHTMARES, WHY? | by @elinakrebs

We all understand the essence and importance of sleep. Sometimes I wondered why, when I was little, I had more nightmares. As I got older it became very rare. What is the reason? Just in the December issue of the German magazine "Soul and Brain" (Gehirn und Geist) I came across an interesting study, which I believe is relevant for understanding nightmares and our feelings. At least one of the "facets" of the perception of the issue. Short reviews on Instagram. nine0003 kellepics from pixabay

Sometimes I wondered why, when I was little, I had more nightmares. As I got older it became very rare. What is the reason? Just in the December issue of the German magazine "Soul and Brain" (Gehirn und Geist) I came across an interesting study, which I believe is relevant for understanding nightmares and our feelings. At least one of the "facets" of the perception of the issue. Short reviews on Instagram. nine0003 kellepics from pixabay

In this study, rodents were subjected to an “unpleasant” experience over the course of a day: for example, there was an unpleasant odor in the air at a certain point in a rat's enclosure. In his study, György Buzsáki from New York University recorded electrical signals in the nerve cells of the brain of mice using electrodes implanted there in two areas:

- amygdala , which is responsible for processing emotions, such as anxiety

- hippocampus , which is responsible for the formation of memory

and our “navigation” system in space

Cerebral cells also create in our brain some “ map of space ”. If a rodent learns that it is experiencing “unpleasant air” in a certain area of its enclosure, this is reflected in the activation of some combination of the corresponding hippocampal cells (memory and navigation) simultaneously with the cells of the amygdala (emotions).

If a rodent learns that it is experiencing “unpleasant air” in a certain area of its enclosure, this is reflected in the activation of some combination of the corresponding hippocampal cells (memory and navigation) simultaneously with the cells of the amygdala (emotions).

As a result, scientists noted that in sleep time in mice, the “lived” experience was activated in the same sequence of brain work, as when they experienced it during wakefulness . It looked as if animal had again covered the same distance, but already in dream . The scientists noted that amygdala nerve cells (emotions) were also activated when the representation of "dangerous places" in the enclosure occurred during the rodent's sleep. In this way, the diversity of connections in the brain was shown as the connection of these regions and indicated that this provides transfer of experience to long-term storage in our memory compartments .

Of course, it is impossible to say exactly how the rodent feels (the situation when the hippocampus is activated in this way during sleep): does he see nightmares? It is possible that activation of this area can also be observed in humans. It is possible that this activation of the amygdala neurons would be tantamount to "unpleasant emotions" experienced during wakefulness .

It is possible that this activation of the amygdala neurons would be tantamount to "unpleasant emotions" experienced during wakefulness .

The author noted that the need to repeat this experience in order to “record” it in the depths of memory can be a potential cause of nightmares .

Further, I thought, perhaps children, as “carriers” of a sensitive nervous system, therefore, see nightmares more often in their sleep, since, firstly, they do not have such a rich experience of coping with the complexities of the outside world, the ability to interpret this experience more calmly and rationally, find an explanation and expression, and secondly, the limbic system (emotions) to a certain age prevails over “logical reason”. It is important to note that all sleep research is carried out using the analysis of wave activity during sleep and children's interviews or reports (which is not always valid, since a child at 4 years old can verbally express what he sees very difficult). Therefore, this study from the very weighty journal Nature is important. nine0003

Therefore, this study from the very weighty journal Nature is important. nine0003

Muris and his colleagues interviewed children 4–12 years of age and found that typical nightmares were dreams of imaginary creatures , personal harm, and animals.

Hawkins and Williams' study indicated that frequent nightmares were associated with bedtime anxiety itself, night terrors, but little or no association with life events and behavioral problems .

Bauer also described child development through childhood fears, including frightening dreams. He interviewed children between the ages of four and twelve. 74% of preschoolers (4-6 years old) reported having nightmares. nine Preschoolers tended to experience fears of imaginary beings and things poorly defined by them , while schoolchildren reported much more specific and realistic fears associated with bodily injury and physical danger .

The same pattern of childhood fears was described by Jersild's study, who also found (like Hawkins and Williams) that children's unpleasant dreams reflect these subjective fears rather than their objective life experiences .

In one Dutch study, 96% of children aged 7-9, 68% of children 4-6, and 76% of children 10-12 reported having nightmares, and almost 70% of children said their dreams were about something they saw on TV .

Night Terrors: How to Identify and What to Do Evaluation of the relationship between waking life and nightmares Li and colleagues found that frequent nightmares were associated with factors such as comorbid sleep disorders, parental predisposition, childhood hyperactivity, mood disturbances and poor academic performance . Extreme living conditions, such as war injury , have an impact on children's dreams. They note a high level of aggression and the appearance of scenes of death in dreams .

Helminen and Punamäki also found evidence of influence in the analysis of the dreams of Palestinian children from traumatic and non-traumatic environments aged 6 to 16 years . They found the ability to remember dreams with vivid contextual images in 90% versus 74% among severely traumatized children. Severe trauma exposure was generally associated with a higher level of post-traumatic symptoms and a high intensity of negative emotional dream images. However, this was not the case for the children in the group, whose dreams included very strong positive emotional images. This relationship between emotional processing of traumatic events and dreams also appears in the dreams of children who have been injured in traffic accidents: 2-6 months after the accident, the frequency of post-traumatic nightmares decreased in parallel with the decrease in post-traumatic stress disorder .

Similarly Terr, dealt with children who were abducted and found that all children had dreams about the traumatic event , including night terrors (60% of children), exact recurring dreams (52%), modified dream replay (52%) and masked dreams (17%) that symbolically reflected some aspect of the traumatic event. He found that those children who had good ability to verbalize their feelings , had more variety of dreams related to trauma, had more memories of their dreams and could use their associations to gain relief during therapy .

He found that those children who had good ability to verbalize their feelings , had more variety of dreams related to trauma, had more memories of their dreams and could use their associations to gain relief during therapy .

Ever had a nightmare you couldn't shake off? | UNICEFStudies evaluating nightmares in schoolchildren highlight the relationship between feelings, emotional regulation, and coping mechanisms. They note that dreams correlate [Avila-White et al., 1999, Foster et al., 1936] or even contribute to emotional processing and processing of various phenomena in the child's life. nine0003

In adulthood, sleep disturbances, or rather the appearance of nightmares, may be associated with the processing of emotional experience for a person, with some neurobiological changes against the background of severe stress or trauma, as well as re-sensitization to trauma signals (biological sensitization is the acquisition by the body of a specific hypersensitivity to foreign substances, and in psychology - an increase in the sensitivity of the nerve centers under the influence of the action of the stimulus)

Thus, the appearance of nightmares in adult or childhood life is associated with the processing of an emotional experience that could have happened long ago or recently, which we accidentally saw on TV or heard from someone for a split second, without even registering the event. When a serious traumatic event occurs in life (accident, death, illness, violence, etc.), the algorithm for working with this condition is different. Now it's not about that. Unconsciously, our nervous system independently "determines" the significance and "understanding" of this or that incident during the day. If upon awakening you start flipping through the dream book in order to understand the image you saw in a dream, then from the point of view of neuroscience it is better to use a different method. Namely, try to understand the true reason for what you saw in a dream, try to interpret and explain for yourself what this could mean. Perhaps tell someone else about it, draw it on a piece of paper, describe it in your diary, discuss it with a therapist if the dream tends to recur. nine0003

When a serious traumatic event occurs in life (accident, death, illness, violence, etc.), the algorithm for working with this condition is different. Now it's not about that. Unconsciously, our nervous system independently "determines" the significance and "understanding" of this or that incident during the day. If upon awakening you start flipping through the dream book in order to understand the image you saw in a dream, then from the point of view of neuroscience it is better to use a different method. Namely, try to understand the true reason for what you saw in a dream, try to interpret and explain for yourself what this could mean. Perhaps tell someone else about it, draw it on a piece of paper, describe it in your diary, discuss it with a therapist if the dream tends to recur. nine0003

If we are talking about a child, then you need to provide him with a “safe” perception of sleep. Relaxing procedures before going to bed, reading, sleeping, dimmed lights, if you sleep better that way, reading good stories from children, which tells about nightmares or bad dreams. Some tricks:

Some tricks:

- “A box of experiences”. In this box, every time a child is afraid to go to sleep, he throws off a piece of paper where he draws or describes his experiences. This box is locked, after "placing fears in it." The parent takes it away from the child, or hide it with the child, so that the child feels safe. nine0010

- “Monster Spray”. If the child is very young, you can take any spray, fill a bottle with water and a relaxing aroma of oil, or buy it together at the store, and spray it in the room every time before going to bed.

- “Magic ointment for good dreams”. before going to bed, rub a relaxing baby cream, you can use oil, which can also be placed in a “magic” bottle that “protects the baby”.

- “Rescue toy. If there is a toy that “protects” others, usually in play, you can use its “super power” or keep a so-called security object nearby in the form of a toy (security object) that calms the child. nine0010

- “Magic lamp”. Turn on a night light that can be chosen together or given to a child that scares away “evil monsters”

- Treasure Hunt.

If the child is afraid of the dark, you can play “treasure hunt” with a flashlight in some dark places in the house, thereby changing the perception of darkness.

If the child is afraid of the dark, you can play “treasure hunt” with a flashlight in some dark places in the house, thereby changing the perception of darkness. - “Welcome good dreams!” sign. Draw and brightly decorate together a sign or sign on the door of the room, or a picture on the wall in the room: “Welcome good dreams!”. Use it before bed as a trigger for good dreams only”

- Do not avoid what scares you. If this is a specific image, then you can draw it, you can look at the picture or cut it into pieces. If a child is afraid of a fire or some event, you can try to figure out what to do in such a situation, develop some kind of escape plan, check the “safety” of the room together. Or bring it to the point of absurdity, for example, the monster will become chocolate and you can eat it.

- If there is any specific stress (kindergarten, parental divorce, frightening incident, etc.), it is very important to communicate and help the child find an explanation.

It is important not to downplay the event, but to evaluate and understand its “scope”. If the child does not remember the nightmare, then it is better not to “pull” this memory. nine0010

Of course, following simple bedtime rules can also help a child or adult deal with nightmares: turn off the media , remove the “blue” light from monitors and gadgets a few hours before bedtime, air the room, sing a lullaby to a child or read a good fairy tale, and an adult can read a relaxing book.

"Children of survivors have nightmares of their parents" - Such cases

- Victims of violence

- Context

- Such a question nine0016

- 22.

10. 2017

10. 2017

Should children be told about repressions? And if so, how?

the executioners did not escape the “witness trauma” and also passed it on to their children

We often underestimate, simply do not notice the social, public consequences that this collective trauma still has. One of the most terrible is the conspiracy of silence around her. In fact, it is very scary to admit that ordinary men and women around us can turn into tormentors. They can torture and kill with impunity, and the law will cover them up, and no retaliatory aggression against them will be possible. It is terrible to look at the other side of human nature. And we prefer not to do this, "not to rock the boat" of our own psyche. Someone uses defensive aggression: “How much you can whine and complain, this has already been said a thousand times!” Someone defensive denial: "It was and has passed, and has nothing to do with us, it will not happen again with us, why stir up. " Someone (still!) paradoxical rationalization: “Still, they didn’t take it in vain, apparently, those who were taken away were really to blame.” nine0003

" Someone (still!) paradoxical rationalization: “Still, they didn’t take it in vain, apparently, those who were taken away were really to blame.” nine0003

In any case, when we start talking about it, with each other or with children, feelings come, and these are heavy feelings, sometimes unbearable. Anger, fear, anxiety, horror, pain... It is clear that everyone will have their own set, but this is definitely not the set with which I would like to spend a family evening.

Talking about trauma

Trauma is incredibly difficult to talk about, even when we are separated from it by two or three generations. Because trauma destroys the ability to create a coherent story in the first place. Meaningful. nine0014 And here some formulas developed by society for condemnation, humility, repentance, what is called "public space" for processing horror, could help. It was created in Germany after the war and is practically absent in Russia.

This is a rather concise explanation of why it is difficult to talk about repression with children. But absolutely necessary.

But absolutely necessary.

Why? Anna-Maria Levin wrote: "It is said that the children of survivors have nightmares of their parents." There are practically no studies on this topic in Russia, all we have is work with children and grandchildren of victims of the Holocaust and other genocides of the 20th century, but judging by these studies, such traumas have a very long-term effect and affect not only those who survived them, but but also for future generations. Changes in the level of hormones and the psyche, recorded in those who survived the camps, are reproduced in a large percentage of children and grandchildren. nine0003

That is, speaking about some "people of that time", we can safely talk about ourselves.

Our task - and this is an incredibly difficult task - is to create a meaningful story for ourselves and the child about the experience of hell.

Your own words for each age

Here, as in stories with adopted children, or as in conversations with children about sex, or about the death of a loved one, you should never hide and keep silent, but each age should have its own truth. I would protect a preschooler from heartbreaking details. I myself am very carefully now telling my daughter (she is six) about the events 1968 years in Czechoslovakia. And it turns out that it is very difficult to explain why the “Russians” (that is, their own, relatives, ours) behaved like villains from the Star Wars movie, and not the way we teach her to behave. Here, careful wording like: “Sometimes some people make a decision, while others are simply forced to follow an order, and there is nowhere for them to go,” or: “Sometimes people, out of fear that it will be even worse for them, can act very cruelly.”

I would protect a preschooler from heartbreaking details. I myself am very carefully now telling my daughter (she is six) about the events 1968 years in Czechoslovakia. And it turns out that it is very difficult to explain why the “Russians” (that is, their own, relatives, ours) behaved like villains from the Star Wars movie, and not the way we teach her to behave. Here, careful wording like: “Sometimes some people make a decision, while others are simply forced to follow an order, and there is nowhere for them to go,” or: “Sometimes people, out of fear that it will be even worse for them, can act very cruelly.”

“Sometimes people, out of fear that it will be even worse for them, can act very cruelly”

Accordingly, a child of 9-10 years old and older can already be given as many details as he himself is ready to learn. The child's psyche is quite capable of self-regulation, and usually where the child intuitively feels that he can't "digest" anymore, cognitive interest ends. He stops asking, switches to something else. While the child is asking - answer, do not be silent. Answer carefully, ask: what does he think about it? Does he think he would be very frightened in the place of those people? And now this would be possible? And what, it seems to him, needs to be done so that this never happens again? nine0003

He stops asking, switches to something else. While the child is asking - answer, do not be silent. Answer carefully, ask: what does he think about it? Does he think he would be very frightened in the place of those people? And now this would be possible? And what, it seems to him, needs to be done so that this never happens again? nine0003

Of course, it is most useful to talk about repressions and about this historical period in general through the prism of the history of one's own kind. Usually, even in those families where no one was exiled, arrested, or shot, there is something to tell and something to think about. And this is generally a very powerful experience, compiling such stories about the experience of your ancestors in the context of time. If there were no bloody and destructive stories there, if no one was taken away at night, no one was tortured in the dungeons and dragged like a bloody bag across the concrete floor, you can just be glad. nine0003

I don't really believe in "museum education", in the benefit of going to museums and some kind of art exhibitions on the topic of repression. They are very necessary for adults, they help the authors themselves to relive and get rid of the nightmares of the past, but for children it is often too abstract and boring. Nightmare stories, like any scary tales, must be passed from mouth to mouth, from person to person, then they "work".

They are very necessary for adults, they help the authors themselves to relive and get rid of the nightmares of the past, but for children it is often too abstract and boring. Nightmare stories, like any scary tales, must be passed from mouth to mouth, from person to person, then they "work".

What not to do

It seems to me that in no case should we deny this terrible piece of the country's experience, and especially - react with irritation to questions or to those who talk about it. There is no need to hush up, believing that the child will find out about everything himself or they will tell him at school. As experience shows, in the modern Russian school they tell rather strange things about this. nine0003

But you shouldn't go to the other extreme, putting a seven or eight year old child to watch a film about Auschwitz or the horrors of the Holocaust. In general, it is better to be careful with films. If with photographs, texts and live stories it is easier for a child to step back at the moment when it is already too much for him, then it is difficult to step back from the film in the middle, and there is a higher risk of “overshooting”.