Checking into mental hospital

What I Wish I Knew

Bipolar DisorderLiving with Bipolar Disorder

Would you put yourself on voluntary psychiatric hold? One woman shares her story of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and what she wishes she knew before she was admitted.

Katie Dale

How to Admit Yourself Into A Mental Hospital

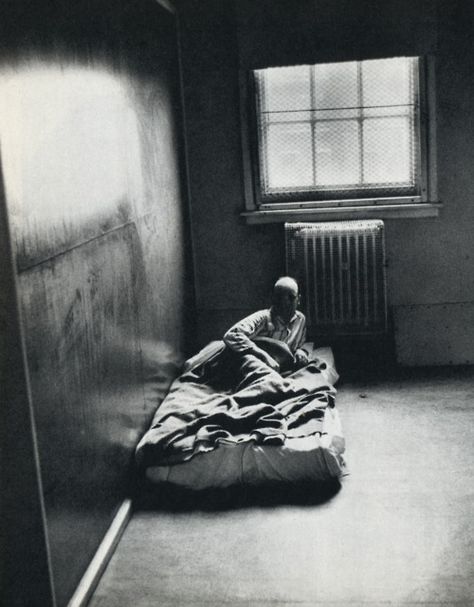

The first time I was admitted to the psych ward, I was 16. I was still a minor, so I had the benefit of boarding with the youth in the juvenile behavioral unit in the local hospital. I wasn’t prepared in the least for what I would see and encounter, nor was my mind in a state to readily accept this place.

Leading up to admission, I had the tell-tale behaviors of mania and depression. But at first, my family and I didn’t recognize these moods as symptoms of bipolar disorder.

While I waited for what seemed like hours in a hospital gown on a cold metal table in an ER admissions room by myself, Mom and Dad signed papers and consulted with the administration to see what could be done for my extraordinary outbursts and melancholy “suicidal” ideations—which, by the way, were not actually suicidal ideations or intentions.

I simply had a sense of my life being cut short—a symptom of manic paranoia—which the hospital interpreted as a threat of harm to myself or others. Another check on the list of criteria for admission.

How Long Is An Inpatient Stay?

An inpatient stay made sense for me. My behavior wasn't making sense and my parents were afraid to leave me alone.

I had been seeing a psychiatrist but she was hesitant to diagnose me at such a young age for reasons of liability and caution, I think. She had met with us a few times prior, but because I now needed around-the-clock monitoring, she advised my parents to take me to the local hospital.

I was scared and confused. I didn't realize where they were taking me—my symptoms were that bad. I had no concept of what a psych ward was and no clue that extended stays were possible. They told me I'd probably spend a long weekend there. It turned out to be three weeks.

The length of stay depends on your needs and can range from a few days to a few weeks and more. The amount of time you spend in an inpatient facility depends on your doctor's recommendation.

The amount of time you spend in an inpatient facility depends on your doctor's recommendation.

My stay was rough because of the illness, but good for me.

I don’t have regrets about the choices I made, or my willingness to go there, to begin with. It was the best place for me to be at that time, with the best help possible. Someone had to figure out what was wrong with me, as I clearly couldn’t. Bipolar disorder sort of snuck up on me at the height of my teenage years and hijacked my mind.

Bipolar Disorder: Finally A Diagnosis

The diagnosis took a while. In fact, I wasn't diagnosed with bipolar disorder until I was released from the psychiatric hospital after my three-week stay. The diagnosis came during consultations while I was being treated in an outpatient program.

The first time I heard the term “bipolar disorder” was the previous year, but I knew it was manifesting in me after speaking to my psychiatrist at the hospital when my symptoms emerged.

Finally being diagnosed was a relief. I think I knew all along that something wasn't right. I could sense I was sick before receiving the official diagnosis but I hadn't been educated yet about mental illness. It felt good to know there was a reason my brain was malfunctioning and it wasn't my fault.

I think I knew all along that something wasn't right. I could sense I was sick before receiving the official diagnosis but I hadn't been educated yet about mental illness. It felt good to know there was a reason my brain was malfunctioning and it wasn't my fault.

What I Wish I Knew Before I Admitted Myself

I've had two inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations in my life—the first when I was 16 and in the juvenile ward. The second, when I was 24 and admitted to the adult ward. I've gleaned some wisdom that may be helpful if you are readying yourself to enter a behavioral unit:

Bring your best advocate with you. It may be your spouse, parent, close friend, or relative—someone who knows you and is familiar with your situation.

Breathe. Recognize that the staff wants to help you, not hurt you.

Be patient. It's a process—there are steps to go through and paperwork to be completed

Once inside, advocate for yourself. The doctor will see you.

Be honest with him.

Be honest with him.Your picture will be taken, and no, they are not stealing your soul.

You will be in a secured unit, locked in. At times they let you out of the unit for visits or short excursions.

Do your best to cooperate with staff and your fellow patients. It may be a while before you are discharged, so bear in mind you are there to get better. Plus, you'll earn extra "points" for being polite and pleasant.

Read your patient rights and understand them.

Your personal belongings will be inventoried, so they will take out shoestrings, belts, hoodies, nail clippers, razors, and anything else deemed potentially dangerous.

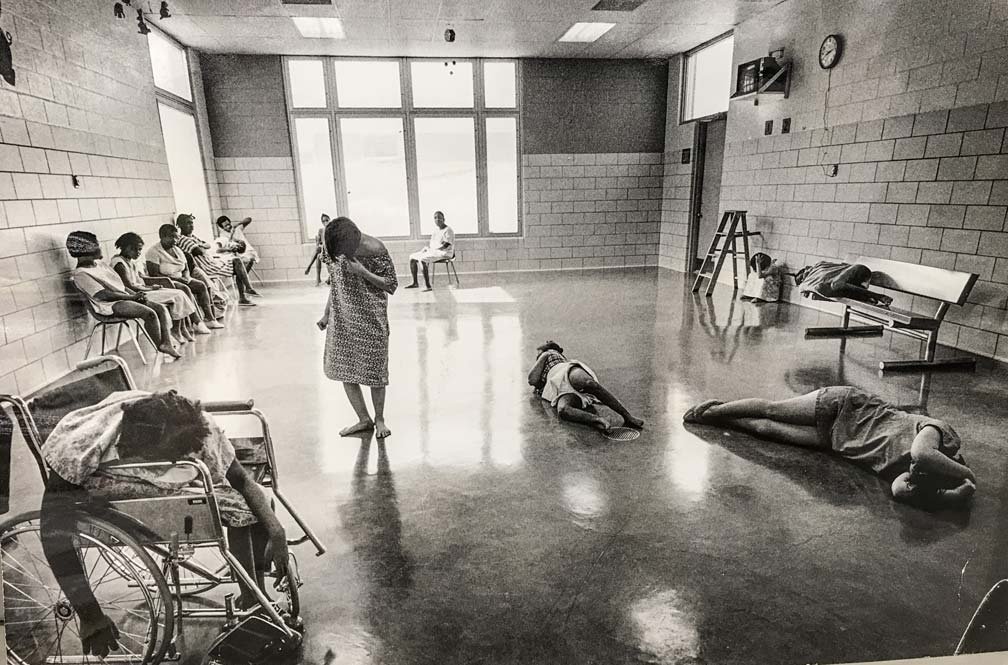

Don't mind the eccentric behaviors of the other patients, they're fighting a similar battle.

Accept that the insides of the building may not be the most aesthetically pleasing. (That said, don't concentrate on abstract paintings if they have them. Abstract art is a bad idea for psychotic symptoms).

If you are in a state of psychosis, the TV may sound as if it's calling your name. It's not, but if the AV stimulation is too much, try to leave the room or focus on a different activity.

Be mindful of the opposite sex (or the same sex if you're so inclined). Establish personal boundaries and adhere to them; the psych ward is not a place to start a romance.

Listen to the staff and don't give them a hard time.

Be friendly and polite. Remember, there are human beings here with feelings.

Seek out a friend and get to know some people.

Read.

Give yourself time and space. You are on a journey to getting better and that takes time and space.

Take a photograph in your mind's eye. Journal about it. Capture the chaotic and colorful journey. Write about it. Express yourself. Get to know who you are at this time.

Be kind, regardless. Don't expect people to respect you because a.

) everyone's imperfect and b.) they can't respect others if they don't respect themselves.

) everyone's imperfect and b.) they can't respect others if they don't respect themselves.Challenge your mind and do a puzzle, but don't read into it—it's just a brain exercise.

Take advantage of physical activity when there's recreation time. Your body needs a physical outlet to help process the stress your mind is going through.

The admission and experience of staying in the psych ward was quite an adventure. I offer these pointers because knowing what I know now back then would have helped me get through the experience with less angst. While it was at times an unfamiliar and uncomfortable place to be, it was also the best place for me and worth it for my mental health.

Notes: This article was originally published July 15, 2021 and most recently updated July 26, 2021.

Katie Dale

Katie Dale is a 30-year old writer and blogger living with bipolar disorder. After having her first bipolar episode at 16, the experience of entering the juvenile unit of a psychiatric hospital in a wheelchair wrapped head-to-toe in a thin blanket is seared into her memory. Katie has recounted her story in a soon-to-be-released memoir. For more information on the book and other tips on dealing with bipolar disorder in yourself or loved ones, visit Katie's blog, BipolarBrave.com.

Katie has recounted her story in a soon-to-be-released memoir. For more information on the book and other tips on dealing with bipolar disorder in yourself or loved ones, visit Katie's blog, BipolarBrave.com.

What I Wish I Knew

Bipolar DisorderLiving with Bipolar Disorder

Would you put yourself on voluntary psychiatric hold? One woman shares her story of inpatient psychiatric hospitalization and what she wishes she knew before she was admitted.

Katie Dale

How to Admit Yourself Into A Mental Hospital

The first time I was admitted to the psych ward, I was 16. I was still a minor, so I had the benefit of boarding with the youth in the juvenile behavioral unit in the local hospital. I wasn’t prepared in the least for what I would see and encounter, nor was my mind in a state to readily accept this place.

Leading up to admission, I had the tell-tale behaviors of mania and depression. But at first, my family and I didn’t recognize these moods as symptoms of bipolar disorder.

But at first, my family and I didn’t recognize these moods as symptoms of bipolar disorder.

While I waited for what seemed like hours in a hospital gown on a cold metal table in an ER admissions room by myself, Mom and Dad signed papers and consulted with the administration to see what could be done for my extraordinary outbursts and melancholy “suicidal” ideations—which, by the way, were not actually suicidal ideations or intentions.

I simply had a sense of my life being cut short—a symptom of manic paranoia—which the hospital interpreted as a threat of harm to myself or others. Another check on the list of criteria for admission.

How Long Is An Inpatient Stay?

An inpatient stay made sense for me. My behavior wasn't making sense and my parents were afraid to leave me alone.

I had been seeing a psychiatrist but she was hesitant to diagnose me at such a young age for reasons of liability and caution, I think. She had met with us a few times prior, but because I now needed around-the-clock monitoring, she advised my parents to take me to the local hospital.

I was scared and confused. I didn't realize where they were taking me—my symptoms were that bad. I had no concept of what a psych ward was and no clue that extended stays were possible. They told me I'd probably spend a long weekend there. It turned out to be three weeks.

The length of stay depends on your needs and can range from a few days to a few weeks and more. The amount of time you spend in an inpatient facility depends on your doctor's recommendation.

My stay was rough because of the illness, but good for me.

I don’t have regrets about the choices I made, or my willingness to go there, to begin with. It was the best place for me to be at that time, with the best help possible. Someone had to figure out what was wrong with me, as I clearly couldn’t. Bipolar disorder sort of snuck up on me at the height of my teenage years and hijacked my mind.

Bipolar Disorder: Finally A Diagnosis

The diagnosis took a while. In fact, I wasn't diagnosed with bipolar disorder until I was released from the psychiatric hospital after my three-week stay. The diagnosis came during consultations while I was being treated in an outpatient program.

The diagnosis came during consultations while I was being treated in an outpatient program.

The first time I heard the term “bipolar disorder” was the previous year, but I knew it was manifesting in me after speaking to my psychiatrist at the hospital when my symptoms emerged.

Finally being diagnosed was a relief. I think I knew all along that something wasn't right. I could sense I was sick before receiving the official diagnosis but I hadn't been educated yet about mental illness. It felt good to know there was a reason my brain was malfunctioning and it wasn't my fault.

What I Wish I Knew Before I Admitted Myself

I've had two inpatient psychiatric hospitalizations in my life—the first when I was 16 and in the juvenile ward. The second, when I was 24 and admitted to the adult ward. I've gleaned some wisdom that may be helpful if you are readying yourself to enter a behavioral unit:

Bring your best advocate with you. It may be your spouse, parent, close friend, or relative—someone who knows you and is familiar with your situation.

Breathe. Recognize that the staff wants to help you, not hurt you.

Be patient. It's a process—there are steps to go through and paperwork to be completed

Once inside, advocate for yourself. The doctor will see you. Be honest with him.

Your picture will be taken, and no, they are not stealing your soul.

You will be in a secured unit, locked in. At times they let you out of the unit for visits or short excursions.

Do your best to cooperate with staff and your fellow patients. It may be a while before you are discharged, so bear in mind you are there to get better. Plus, you'll earn extra "points" for being polite and pleasant.

Read your patient rights and understand them.

Your personal belongings will be inventoried, so they will take out shoestrings, belts, hoodies, nail clippers, razors, and anything else deemed potentially dangerous.

Don't mind the eccentric behaviors of the other patients, they're fighting a similar battle.

Accept that the insides of the building may not be the most aesthetically pleasing. (That said, don't concentrate on abstract paintings if they have them. Abstract art is a bad idea for psychotic symptoms).

If you are in a state of psychosis, the TV may sound as if it's calling your name. It's not, but if the AV stimulation is too much, try to leave the room or focus on a different activity.

Be mindful of the opposite sex (or the same sex if you're so inclined). Establish personal boundaries and adhere to them; the psych ward is not a place to start a romance.

Listen to the staff and don't give them a hard time.

Be friendly and polite. Remember, there are human beings here with feelings.

Seek out a friend and get to know some people.

Read.

Give yourself time and space. You are on a journey to getting better and that takes time and space.

Take a photograph in your mind's eye.

Journal about it. Capture the chaotic and colorful journey. Write about it. Express yourself. Get to know who you are at this time.

Journal about it. Capture the chaotic and colorful journey. Write about it. Express yourself. Get to know who you are at this time.Be kind, regardless. Don't expect people to respect you because a.) everyone's imperfect and b.) they can't respect others if they don't respect themselves.

Challenge your mind and do a puzzle, but don't read into it—it's just a brain exercise.

Take advantage of physical activity when there's recreation time. Your body needs a physical outlet to help process the stress your mind is going through.

The admission and experience of staying in the psych ward was quite an adventure. I offer these pointers because knowing what I know now back then would have helped me get through the experience with less angst. While it was at times an unfamiliar and uncomfortable place to be, it was also the best place for me and worth it for my mental health.

Notes: This article was originally published July 15, 2021 and most recently updated July 26, 2021.

Katie Dale

Katie Dale is a 30-year old writer and blogger living with bipolar disorder. After having her first bipolar episode at 16, the experience of entering the juvenile unit of a psychiatric hospital in a wheelchair wrapped head-to-toe in a thin blanket is seared into her memory. Katie has recounted her story in a soon-to-be-released memoir. For more information on the book and other tips on dealing with bipolar disorder in yourself or loved ones, visit Katie's blog, BipolarBrave.com.

Article 23. Psychiatric examination \ ConsultantPlus

Article 23. Psychiatric examination

(1) A psychiatric examination is carried out to determine whether the subject suffers from a mental disorder, whether he needs psychiatric assistance, and to decide on the type of such assistance.

(2) Psychiatric examination is carried out with the informed voluntary consent of the person being examined to conduct it. A psychiatric examination of a minor under the age of fifteen or a drug addicted minor under the age of sixteen is carried out with the informed voluntary consent of one of the parents or other legal representative, and in relation to a person recognized in the manner prescribed by law as legally incompetent, if such a person is is unable to give informed voluntary consent to his condition - if there is informed voluntary consent to conduct a psychiatric examination of the legal representative of such a person. In case of objection of one of the parents or in the absence of parents or other legal representative, a psychiatric examination of a minor is carried out by decision of the guardianship and guardianship body, which can be appealed to the court. The legal representative of a person recognized as incapacitated in accordance with the procedure established by law shall notify the guardianship and guardianship authority at the place of residence of the ward of giving informed voluntary consent to a psychiatric examination of the ward no later than the day following the day the said consent was given. nine0003

In case of objection of one of the parents or in the absence of parents or other legal representative, a psychiatric examination of a minor is carried out by decision of the guardianship and guardianship body, which can be appealed to the court. The legal representative of a person recognized as incapacitated in accordance with the procedure established by law shall notify the guardianship and guardianship authority at the place of residence of the ward of giving informed voluntary consent to a psychiatric examination of the ward no later than the day following the day the said consent was given. nine0003

(Part 2 as amended by the Federal Law of November 25, 2013 N 317-FZ)

(see the text in the previous edition)

(3) A doctor conducting a psychiatric examination must introduce himself to the subject and his legal representative as a psychiatrist except for the cases provided for in paragraph "a" of the fourth part of this article.

(4) A psychiatric examination of a person may be carried out without his consent or without the consent of his legal representative in cases where, according to the available data, the person being examined commits actions that give grounds to assume that he has a severe mental disorder, which causes:

a) his immediate danger to himself or others, or

b) his helplessness, that is, his inability to satisfy his basic needs on his own, or

c) significant harm to his health due to deterioration of his mental state, if the person is left without psychiatric care .

(5) A psychiatric examination of a person may be carried out without his consent or without the consent of his legal representative, if the person being examined is under dispensary observation on the grounds provided for in Section 27, Paragraph one of this Law. nine0003

(6) The data of the psychiatric examination and the conclusion on the state of mental health of the person being examined shall be recorded in the medical records, which also indicate the reasons for contacting a psychiatrist and medical recommendations.

(7) A psychiatric examination of a citizen specified in Article 15 of this Law is carried out within the framework of a military medical examination in accordance with Article 61 of the Federal Law of November 21, 2011 N 323-FZ "On the Fundamentals of Protecting the Health of Citizens in the Russian Federation". nine0003

(Part 7 was introduced by Federal Law No. 317-FZ of November 25, 2013)

The Investigative Committee began an inspection of the Gannushkin hospital on the grounds of illegal hospitalization - RT in Russian

illegal hospitalization of 44-year-old Svetlana Gudkova. According to her, forced placement in a hospital was used after a divorce by her ex-husband, who made sure that the woman was limited in parental rights and deprived of access to a common apartment. Gudkova voluntarily underwent an independent examination, which did not confirm the diagnoses made to her in the hospital. nine0003

According to her, forced placement in a hospital was used after a divorce by her ex-husband, who made sure that the woman was limited in parental rights and deprived of access to a common apartment. Gudkova voluntarily underwent an independent examination, which did not confirm the diagnoses made to her in the hospital. nine0003

The Main Investigative Committee of the Investigative Committee for Moscow has begun an inspection of the Gannushkin Psychiatric Clinical Hospital No. 4 on the grounds of a crime under Article 128 of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation (“Illegal hospitalization in a medical organization providing psychiatric care in an inpatient setting”). A report on the discovery of signs of a crime is at the disposal of RT.

The check began in connection with the admission to the hospital of 44-year-old Muscovite Svetlana Gudkova, whom RT previously wrote about. After a divorce from her husband, the woman was forcibly hospitalized, a psychiatric diagnosis was made, and her parental rights were limited. Also, she is not allowed into a shared apartment, the majority of which belonged to Svetlana. nine0003

Also, she is not allowed into a shared apartment, the majority of which belonged to Svetlana. nine0003

According to Gudkova, the pre-investigation check is still going on.

“About a month later I will undergo a psychiatric examination. I hope the UK will be able to sort out the situation and those responsible for my illegal hospitalization will be punished, and I will be able to remove the diagnosis, ”the woman said.

According to her, the psychiatric hospital refused to issue medical records to the investigation, so now they are being seized. In the Gannushkin Design Bureau, RT was unable to promptly comment on the situation. RT also sent a request to the Russian Investigative Committee. nine0003

“My husband cut me off from finances”

As RT previously reported, Svetlana and Maxim Gudkov have been married for 16 years. The family has three children (18, 16 and seven years old). According to Svetlana, problems with her husband began after the birth of her third child, when the woman left work to take care of the children, and her husband at that time “cut her off from finances. ” “I found myself in a completely dependent position, so I decided to file for divorce,” she explained.

” “I found myself in a completely dependent position, so I decided to file for divorce,” she explained.

The Gudkovs divorced in May 2018. At the same time, two years before the divorce, Maxim filed a lawsuit against his wife demanding that she pay for a communal apartment. The corresponding document was registered in the Savyolovsky court. As follows from the materials of the instance, the claim was left without consideration. nine0003

After the Gudkovs divorced, courts began, connected with the division of property and the payment of alimony. All this time, the couple lived in a common apartment. The ongoing quarrels had a detrimental effect on the condition of the woman. In June 2018, after another scandal, Svetlana decided to see a doctor. As Svetlana recalls, she could not sleep for several days due to nervousness, so she called an ambulance.

She was hospitalized at the Gannushkin Hospital. There, Gudkova was diagnosed with a serious diagnosis - paranoid schizophrenia. Through the court, the hospital achieved involuntary hospitalization. The woman was released only after 50 days. nine0003

Through the court, the hospital achieved involuntary hospitalization. The woman was released only after 50 days. nine0003

Svetlana believes that her ex-husband, who distorted information about her behavior, had a hand in this. “He got into the confidence of the doctor and spun fables. That supposedly I've been out of my mind for a long time, but he used to hide it. He took a real situation and inflated it to a fantastic scale. Everything has been flipped. Describing that I was financially completely dependent on my husband, I said that I was a hostage of the situation. In a figurative sense, and this was interpreted, that I have delusions of persecution and I believe that I was kidnapped and physically held hostage. Which, of course, is not so, ”Gudkova explained. nine0003

The diagnosis was challenged

Later, she underwent a voluntary examination at the Pomoshch outpatient clinic, where the diagnosis was refuted. Doctor of Medical Sciences Mikhail Drobizhev came to the conclusion that the diagnosis was made erroneously, pointing out a number of gross inconsistencies in the previous conclusion of the doctors. For example, a vivid manifestation of schizophrenia occurs before the age of 30, and Svetlana was diagnosed at 44. As Drobizhev noted, if a woman really suffered from schizophrenia, it is not clear how she could work and raise children for so many years without attracting the attention of psychiatrists. nine0003

For example, a vivid manifestation of schizophrenia occurs before the age of 30, and Svetlana was diagnosed at 44. As Drobizhev noted, if a woman really suffered from schizophrenia, it is not clear how she could work and raise children for so many years without attracting the attention of psychiatrists. nine0003

In a new study, hospitalization was attributed solely to severe stress. “At the time of observation, there are no signs of a mental disorder. Gudkova does not pose a danger to children ... She does not need treatment with psychotropic drugs and observation by a psychiatrist, ”the conclusion says.

From the psychiatric hospital, Svetlana returned to the common housing with her ex-husband. And in December 2019, she was hospitalized again, this time, as she said, at the call of Maxim Gudkov. The woman was again forcibly kept for 50 days, but this time the diagnosis was changed to a milder one - schizotypal personality disorder. nine0003

It was also subsequently refuted by an independent expert. According to the conclusion, Svetlana's "in the past had strange beliefs that did not correspond to cultural norms" as the main sign of the disorder, but this in itself cannot be a sign of disorder, which is specifically enshrined in the law. But other obvious symptoms that should have manifested throughout life (obsessive states, depersonalization, etc.) were absent in Gudkova, the experts concluded. nine0003

According to the conclusion, Svetlana's "in the past had strange beliefs that did not correspond to cultural norms" as the main sign of the disorder, but this in itself cannot be a sign of disorder, which is specifically enshrined in the law. But other obvious symptoms that should have manifested throughout life (obsessive states, depersonalization, etc.) were absent in Gudkova, the experts concluded. nine0003

“Achieve cancellation”

Maxim Gudkov, meanwhile, filed a lawsuit to restrict Svetlana's parental rights. He justified this precisely by the fact that the woman “has a mental illness“ paranoid schizophrenia ”, in July 2018 and in December 2019 she was placed in a psychiatric hospital.” As Gudkov pointed out in the lawsuit, his ex-wife refuses to take pills and is a danger to children.

The court considered these arguments convincing, and after being discharged from the hospital, Svetlana could not go home. Now she lives with relatives and seeks through the court the restoration of parental rights, and is also trying to regain the right to use the common living space.

![]()

Learn more