Celexa and depakote

Lexapro, Zoloft, Celexa, and More

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

In this Article

- SSRI Side Effects

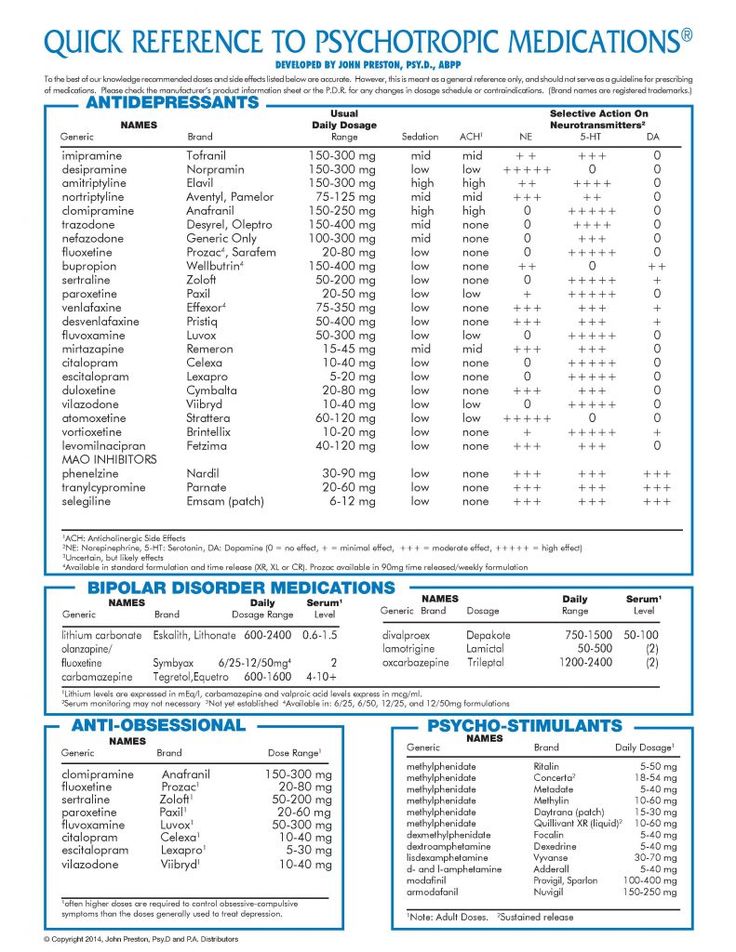

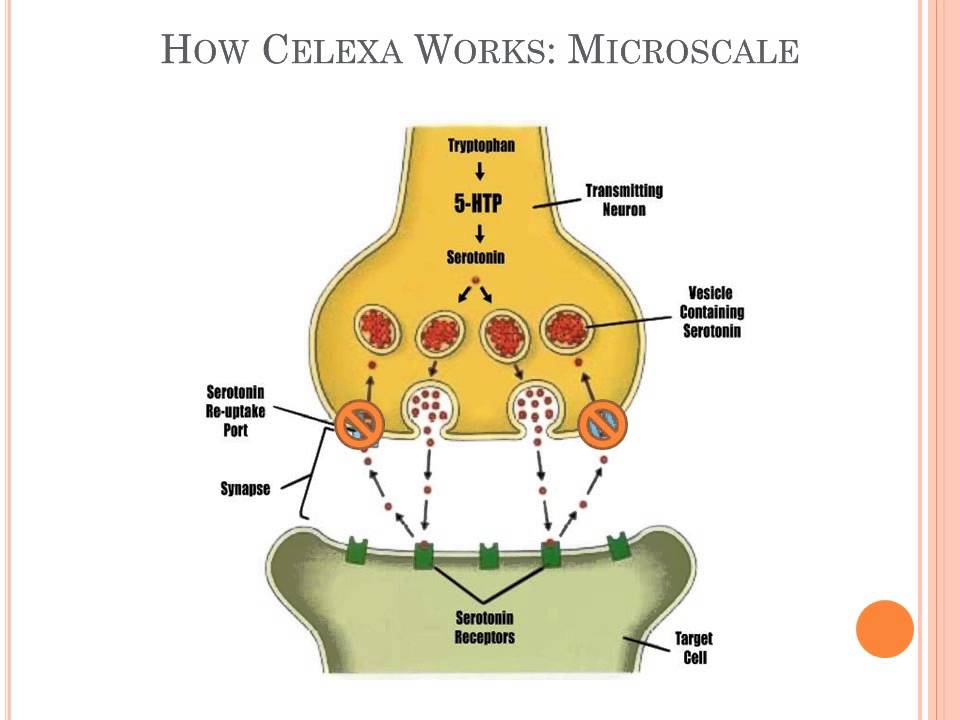

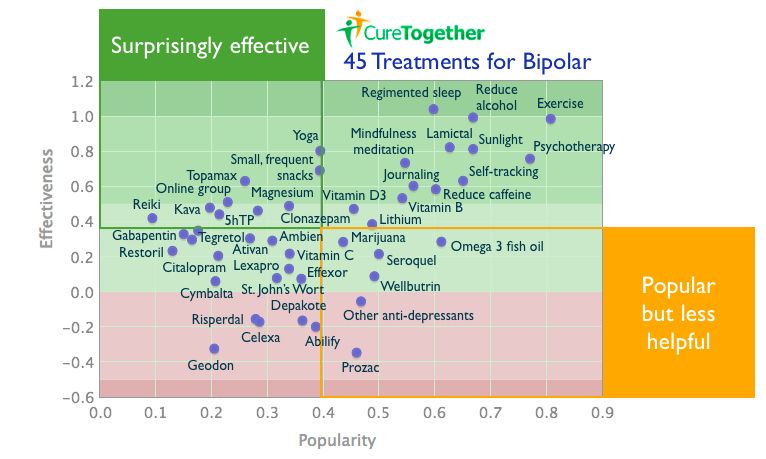

Traditional antidepressants are considered "experimental" for treating bipolar depression in that none has been proven to be more effective than a placebo (sugar pill) in bipolar I disorder. If taken alone, some may actually worsen symptoms of bipolar or uncover a manic episode. Studies also have shown that they may not provide additional benefit for bipolar depression if they're taken along with a mood stabilizer such as lithium or Depakote. Nevertheless, your doctor may prescribe newer antidepressants known as SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) for treating depression in bipolar disorder -- along with lithium or other mood stabilizing drugs such as valproate, carbamazepine or an atypical antipsychotic.

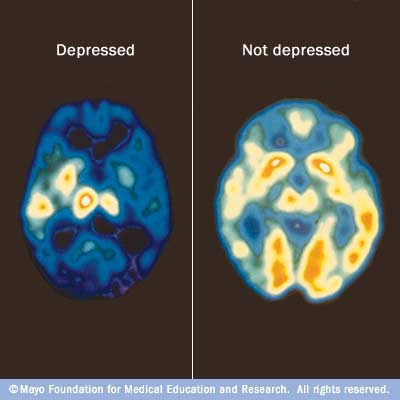

If and when an antidepressant is effective for someone with bipolar depression, it is believed that the medicine works by boosting the functioning of nerve cells in the brain that communicate through the chemical (neurotransmitter) serotonin.

This class of antidepressants includes:

- citalopram (Celexa)

- escitalopram (Lexapro)

- fluoxetine (Prozac)

- fluvoxamine (Luvox)

- paroxetine (Paxil)

- sertraline(Zoloft)

Vilazodone (Viibryd) and vortioxetine (Trintellix, formerly called Brintellix) are two newer antidepressants that affect the serotonin transporter as well as other serotonin receptors in the brain.

Most antidepressants take several weeks to start working. Though the first one that is prescribed works in the majority of people, others may need to try two or three to find the right one. Your doctor may also prescribe a sedative to help relieve anxiety, agitation, or sleep problems while the antidepressant begins to work.

SSRI side effects are generally milder than those of the older classes of antidepressants. There are many strategies to counteract the common side effects of SSRIs if they develop, and some side effects may occur only briefly at the beginning of treatment.

Common SSRI side effects may include:

- Nausea

- Nervousness

- Insomnia

- Diarrhea

- Rash

- Agitation

- Erectile dysfunction

- Loss of libido

- Weight gain or loss

In people with bipolar disorder, SSRIs and other antidepressants carry a risk of inducing mania, making it essential to monitor for signs of excess energy, decreased need for sleep, or abnormal and excessive mood elevation. The FDA also recommends closely observing young people treated with SSRIs or other antidepressants for worsening depression or the emergence of suicidal tendencies. It is sometimes difficult to know whether suicidal thoughts or behaviors that occur or worsen during antidepressant treatment are the result of the antidepressant itself or of the ongoing depression that the antidepressant may not be effectively treating. For this reason, the FDA recommends careful monitoring of patients being treated with these drugs -- especially at the beginning of therapy and during dose changes.

© 2022 WebMD, LLC. All rights reserved. View privacy policy and trust info

Today on WebMD

Recommended for You

Citalopram (Celexa) | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness

Brand names:

- Celexa®

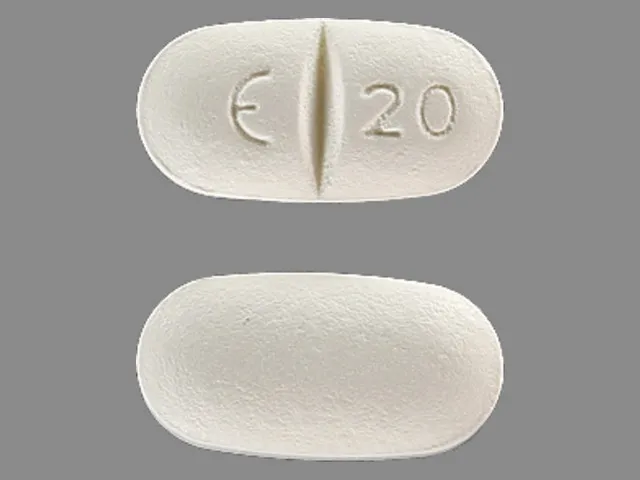

- Tablets: 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg

- Citalopram

- Tablets: 10 mg, 20 mg, 40 mg

- Liquid: 10 mg/5 ml

Generic name: citalopram (sye TAL oh pram)

All FDA black box warnings are at the end of this fact sheet. Please review before taking this medication.

What Is Citalopram And What Does It Treat?

Citalopram is an antidepressant medication that works in the brain. It is approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD).

Symptoms of depression include:

- Depressed mood - feeling sad, empty, or tearful

- Feeling worthless, guilty, hopeless, and helpless

- Loss of interest or pleasure in your usual activities

- Sleep and eat more or less than usual (for most people it is less)

- Low energy, trouble concentrating, or thoughts of death (suicidal thinking)

- Psychomotor agitation (‘nervous energy’)

- Psychomotor retardation (feeling like you are moving and thinking in slow motion)

- Suicidal thoughts or behaviors

Citalopram may also be helpful when prescribed “off-label” for obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, panic disorder, social phobia (also known as social anxiety disorder), posttraumatic stress disorder, eating disorders such as binge eating disorder, and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD). “Off-label” means that it hasn’t been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this condition. Your mental health provider should justify his or her thinking in recommending an “off-label” treatment. They should be clear about the limits of the research around that medication and if there are any other options.

“Off-label” means that it hasn’t been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this condition. Your mental health provider should justify his or her thinking in recommending an “off-label” treatment. They should be clear about the limits of the research around that medication and if there are any other options.

What Is The Most Important Information I Should Know About Citalopram?

Do not stop taking citalopram even when you feel better. With input from you, your health care provider will assess how long you will need to take the medicine.

Missing doses of citalopram may increase your risk for relapse in your symptoms.

Stopping citalopram abruptly may result in one or more of the following withdrawal symptoms: irritability, nausea, feeling dizzy, vomiting, nightmares, headache, and/or paresthesias (prickling, tingling sensation on the skin).

Depression is also a part of bipolar illness. People with bipolar disorder who take antidepressants may be at risk for "switching" from depression into mania. Symptoms of mania include "high" or irritable mood, very high self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, pressure to keep talking, racing thoughts, being easily distracted, frequently involved in activities with a large risk for bad consequences (for example, excessive buying sprees).

Symptoms of mania include "high" or irritable mood, very high self-esteem, decreased need for sleep, pressure to keep talking, racing thoughts, being easily distracted, frequently involved in activities with a large risk for bad consequences (for example, excessive buying sprees).

Medical attention should be sought if serotonin syndrome is suspected. Please refer to serious side effects for signs/symptoms.

Are There Specific Concerns About Citalopram And Pregnancy?

If you are planning on becoming pregnant, notify your health care provider to best manage your medications. People living with MDD who wish to become pregnant face important decisions. Untreated MDD has risks to the fetus, as well as the mother. It is important to discuss the risks and benefits of treatment with your doctor and caregivers. For women who take antidepressant medications during weeks 13 through the end of their pregnancy (second and third trimesters), there is a risk that the baby can be born before it is fully developed (before 37 weeks).

For mothers who have taken SSRIs during their pregnancy, there appears to be less than a 1% chance of infants developing persistent pulmonary hypertension. This is a potentially fatal condition that is associated with use of the antidepressant in the second half of pregnancy. However, women who discontinued antidepressant therapy were five times more likely to have a depression relapse than those who continued their antidepressant. If you are pregnant, please discuss the risks and benefits of antidepressant use with your health care provider.

Caution is advised with breastfeeding since citalopram does pass into breast milk.

What Should I Discuss With My Health Care Provider Before Taking Citalopram?

- Symptoms of your condition that bother you the most

- If you have thoughts of suicide or harming yourself

- Medications you have taken in the past for your condition, whether they were effective or caused any adverse effects

- If you experience side effects from your medications, discuss them with your provider.

Some side effects may pass with time, but others may require changes in the medication.

Some side effects may pass with time, but others may require changes in the medication. - Any other psychiatric or medical problems you have, including a history of bipolar disorder

- All other medications you are currently taking (including over the counter products, herbal and nutritional supplements) and any medication allergies you have

- Other non-medication treatment you are receiving, such as talk therapy or substance abuse treatment. Your provider can explain how these different treatments work with the medication.

- If you are pregnant, plan to become pregnant, or are breastfeeding

- If you drink alcohol or use drugs

How Should I Take Citalopram?

Citalopram is usually taken one time per day with or without food.

Typically patients begin at a low dose of medicine and the dose is increased slowly over several weeks.

The dose usually ranges from 20 mg to 40 mg once daily. For patients older than 60 years, the maximum recommended dose is 20 mg once daily. Only your health care provider can determine the correct dose for you.

Only your health care provider can determine the correct dose for you.

The liquid should be measured with a dosing spoon or oral syringe which you can get from your pharmacy.

If you are taking citalopram, you should not take other medications that include escitalopram (Lexapro®).

Consider using a calendar, pillbox, alarm clock, or cell phone alert to help you remember to take your medication. You may also ask a family member or friend to remind you or check in with you to be sure you are taking your medication.

What Happens If I Miss A Dose Of Citalopram?

If you miss a dose of citalopram, take it as soon as you remember, unless it is closer to the time of your next dose. Discuss this with your health care provider. Do not double your next dose or take more than what is prescribed.

What Should I Avoid While Taking Citalopram?

Avoid drinking alcohol or using illegal drugs while you are taking antidepressant medications. They may decrease the benefits (e. g., worsen your condition) and increase adverse effects (e.g., sedation) of the medication.

g., worsen your condition) and increase adverse effects (e.g., sedation) of the medication.

What Happens If I Overdose With Citalopram?

If an overdose occurs, call your doctor or 911. You may need urgent medical care. You may also contact the poison control center at 1-800-222-1222.

A specific treatment to reverse the effects of citalopram does not exist.

What Are The Possible Side Effects Of Citalopram?

Common side effects

Headache, nausea, diarrhea, dry mouth, increased sweating, feeling nervous, restless, fatigue, or having trouble sleeping (insomnia). These will often improve over the first week or two as you continue to take the medication.

Sexual side effects, such as problems with orgasm or ejaculatory delay often do not diminish over time.

Rare/serious side effects

Low sodium blood levels (symptoms of low sodium levels may include headache, weakness, difficulty concentrating and remembering), teeth grinding, angle closure glaucoma (symptoms of angle closure glaucoma may include eye pain, changes in vision, swelling or redness in or around eye), serotonin syndrome (symptoms may include shivering, diarrhea, confusion, severe muscle tightness, fever, seizures, and death), seizure

SSRI antidepressants including citalopram may increase the risk of bleeding events. Combined use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen), warfarin, and other anti-coagulants may increase this risk. This may include symptoms such as gums that bleed more easily, nose bleed, or gastrointestinal bleeding. Some cases have been life threatening.

Combined use of aspirin, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (e.g., ibuprofen, naproxen), warfarin, and other anti-coagulants may increase this risk. This may include symptoms such as gums that bleed more easily, nose bleed, or gastrointestinal bleeding. Some cases have been life threatening.

Risk of abnormal heart rhythms with citalopram

August 2011: Citalopram at doses greater than 40 mg per day could potentially cause a dangerous abnormality in the electrical activity of the heart. Citalopram use is discouraged in patients with congenital long QT syndrome. Patients with low levels of potassium and magnesium in the blood are also at increased risk. If you are currently taking citalopram at a dose greater than 40 mg per days, talk to your health care professional. Seek immediate care if you experience an irregular heartbeat, shortness of breath, dizziness, or fainting while taking citalopram. If you are taking citalopram, your health care professional may occasionally order an electrocardiogram (ECG, EKG) to monitor your heart rate and rhythm. Your health care provider may also order tests to check levels of potassium and magnesium in your blood.

Your health care provider may also order tests to check levels of potassium and magnesium in your blood.

Are There Any Risks For Taking Citalopram For Long Periods Of Time?

To date, there are no known problems associated with long term use of citalopram. It is a safe and effective medication when used as directed.

What Other Medications May Interact With Citalopram?

Citalopram should not be taken with or within 2 weeks of taking monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs). These include phenelzine (Nardil®), tranylcypromine (Parnate®), isocarboxazid (Marplan®), rasagiline (Azilect®), and selegiline (Emsam®).

Although rare, there is an increased risk of serotonin syndrome when citalopram is used with other medications that increase serotonin, such as other antidepressants, migraine medications called “triptans” (e.g., Imitrex®), some pain medications (e.g., tramadol (Ultram®), the antibiotic linezolid (Zyvox®), and amphetamines.

Citalopram may increase the effects of other medications that can cause bleeding (e. g., ibuprofen (Advil®, Motrin®), warfarin (Coumadin®) and aspirin).

g., ibuprofen (Advil®, Motrin®), warfarin (Coumadin®) and aspirin).

Increased risk of QT prolongation when used with:

- Certain antiarrhythmics: quinidine (Quinidex Extentabs®, Quinaglute®, Quinalan®), procainamide (Procanbid®, Pronestyl®, Pronestyl-SR®), amiodarone (Cordarone®, Pacerone®), sotalol (Betapace®, Sorine®)

- Certain antipsychotics: chlorpromazine (Thorazine®), thioridazine (Mellaril®)

- Certain antibiotics: gatifloxacin (Tequin®), moxifloxacin (Avelox®)

- Methadone®

How Long Does It Take For Citalopram To Work?

Sleep, energy, or appetite may show some improvement within the first 1-2 weeks. Improvement in these physical symptoms can be an important early signal that the medication is working. Depressed mood and lack of interest in activities may need up to 6-8 weeks to fully improve.

Summary of FDA Black Box Warnings

Suicidal thoughts or actions in children and adults

Depression and certain other psychiatric disorders are themselves associated with increases in the risk of suicide. Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications. This risk may persist until significant remission occurs.

Patients with major depressive disorder (MDD), both adult and pediatric, may experience worsening of their depression and/or the emergence of suicidal ideation and behavior (suicidality) or unusual changes in behavior, whether or not they are taking antidepressant medications. This risk may persist until significant remission occurs.

In short-term studies, antidepressants increased the risk of suicidality in children, adolescents, and young adults when compared to placebo. Short-term studies did not show an increase in the risk of suicidality with antidepressants compared to placebo in adults beyond age 24. Adults age 65 and older taking antidepressants have a decreased risk of suicidality. Patients, their families, and caregivers should be alert to the emergence of anxiety, restlessness, irritability, aggressiveness and insomnia. If these symptoms emerge, they should be reported to the patient’s prescriber or health care professional. All patients being treated with antidepressants for any indication should watch for and notify their health care provider for worsening symptoms, suicidality and unusual changes in behavior, especially during the first few months of treatment.

Provided by

(December 2020)

©2020 The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists (CPNP) and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). CPNP and NAMI make this document available under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives 4.0 International License. Last Updated: January 2016.

This information is being provided as a community outreach effort of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. This information is for educational and informational purposes only and is not medical advice. This information contains a summary of important points and is not an exhaustive review of information about the medication. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified medical professional with any questions you may have regarding medications or medical conditions. Never delay seeking professional medical advice or disregard medical professional advice as a result of any information provided herein. The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists disclaims any and all liability alleged as a result of the information provided herein.

The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists disclaims any and all liability alleged as a result of the information provided herein.

Epilepsy drug caused congenital diseases in 450 children in France - Vademecum magazine

Epilepsy drug caused congenital diseases in 450 children in France

Olga Chesnokova

February 24, 2016, 22:37

Photo:

www.bbc.co.uk

3936

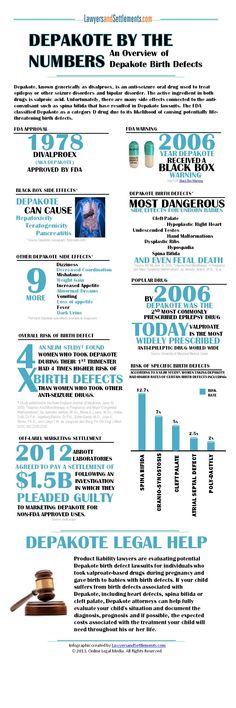

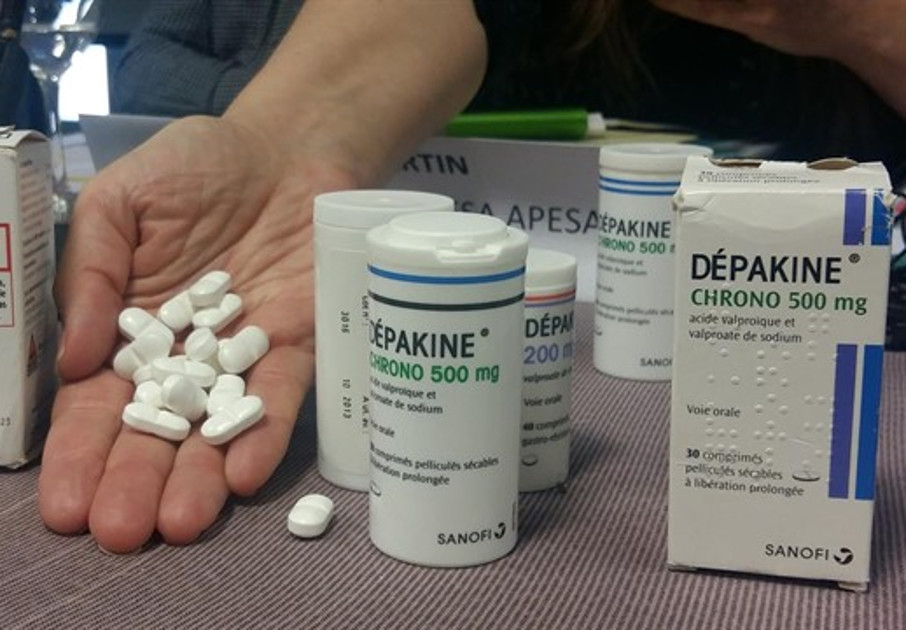

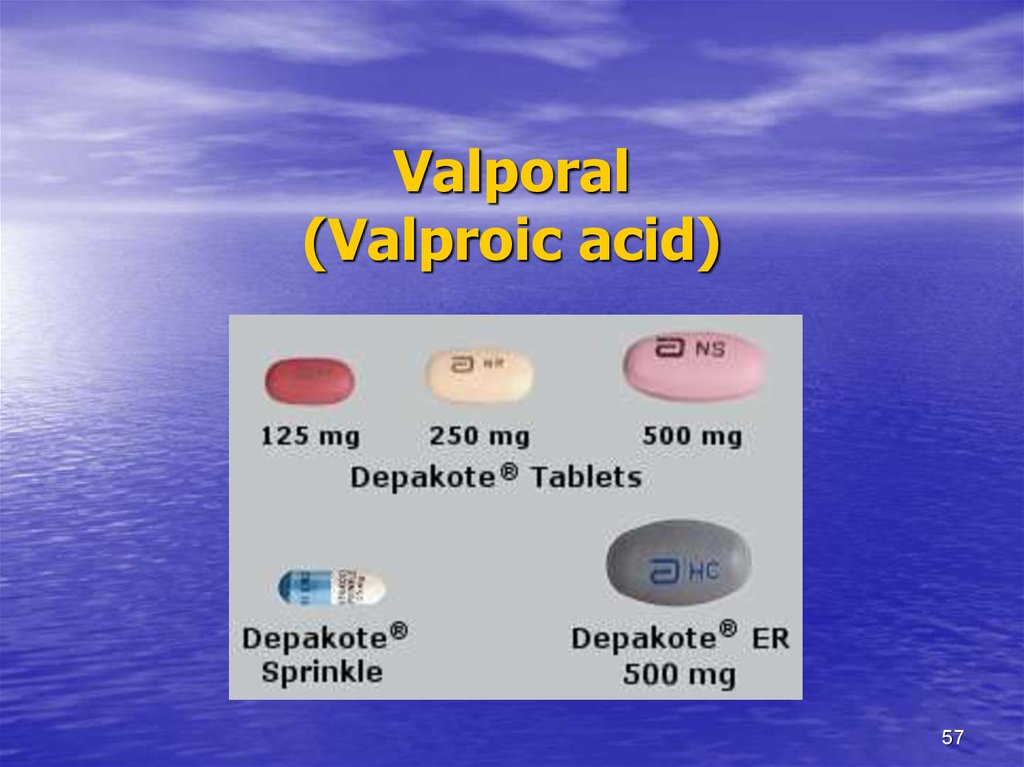

The French Inspectorate General of Social Affairs (IGAS) presented a study on the drug valproate, sold under the trade names Depakine, Depakote, Depamid and Micropakine. According to the report of the department, the drug caused the development of congenital diseases in at least 450 children born in 2006-2014.

Valproate is used as an anticonvulsant in epilepsy and bipolar disorder. The production of the original anticonvulsant drug Depakine was started by the pharmaceutical company Sanofi in 1967, after the appearance of generics, the drug became available to residents of more than 120 countries.

For the first time, the risk of fetal developmental anomalies (defects in the development of the facial and cerebral parts of the skull, heart, kidneys, urinary tract, genital organs, and limbs) when taking Depakine by pregnant women was discovered back in the 80s of the XX century, however, Depakine therapy then was mandatory for patients with epilepsy. In the 2000s, it became known that the drug was associated with a slow development of the nervous system in children, and in 2013 its connection with autism was suspected. In 2015, it was found that the IQ was reduced in 40% of children taking valproate.

Valproate attracted the attention of the French authorities after it became known that one of the inhabitants of the country, who had suffered from epilepsy since the age of six, took Depakine during two pregnancies. Doctors did not tell the woman about the risks of taking the medicine during this period, and her two sons were born with severe congenital diseases. As a result, the Frenchwoman sued Sanofi, and also founded APESAC, a support association for parents of children suffering from serious illnesses due to Depakine. During the five years of its existence, the parents of 500 affected children have joined the association.

During the five years of its existence, the parents of 500 affected children have joined the association.

In this high-profile case, French Minister of Health Marisol Touraine commissioned IGAS to prepare a reassessment of the risk-benefit ratio of valproate during pregnancy and for women of reproductive age (15-49 years). The document also provides an overview of the measures that have been taken regarding the anticonvulsant drug in other European countries.

The head of the French Ministry of Health also plans to establish a compensation fund for residents of the country affected by Depakine, Figaro reports, and to further reduce the number of women taking this drug during pregnancy.

In 2015, Sanofi issued new recommendations for the use of valproate and its derivatives in women of childbearing age and pregnant women, stating that they should not use this drug "unless other treatments have failed or are not well tolerated by the patient." In addition, when prescribing the drug, the doctor should inform the patient about the risks of its use.

In June 2015, it became known that another popular drug, Pfizer's antidepressant Zoloft, could also cause birth defects in children if their mothers took the drug during pregnancy. Then the pharmaceutical company was accused of hiding information about the serious side effects of the drug.

- #congenital diseases

- #valproate

- #france

Subscribe to our channels

Telegram Telegram LiveOpen_yaschik_Skinnera - Page 30

|

| 2 93 |

kry"? Most of those operated on did not cling to toys or scream obscenities, or at least did so for a short time, but there were lasting effects: many of them became less bright, as if they had ceased to be themselves, turning into black-and-white photocopies, unable to reproduce the shades of their personalities.

However, something can be said in favor of the loss of brightness: a spark, if it burns too hot, can burn. One of the lobotomized psychiatrists was able to open his own psychiatric clinic. Another patient set up an extremely profitable business and flew his own aircraft. So who can make the final verdict? The value of the lobotomy is not in what it has or has not been able to achieve, but in drawing attention to medical ethics: what is informed consent? Is it ethical to replace one form of organic brain dysfunction with another? Is an intervention that destroys healthy tissue in the human body justified? Shouldn't the inner sanctity of the brain be respected? Won't surgeons (and hasn't they already) become the long arm of the law? There is some irony in the fact that fears about an operation that could deprive a person of a soul, extinguish a spark, lead us to the crucible of doubts about what we are ready to lose and how difficult the treatment we will agree to.

The press, never thinking too hard about the complexities, picked up the news and advertised the lobotomy. In 1948 The New York Times wrote:

In 1948 The New York Times wrote:

Surgery for the mentally ill: cures for obsessions reported. The new technique is said to have helped 65% of those suffering from mental illness, to whom it was applied as a last resort, but some leading experts in the field of neuroscience express serious doubts.

| 2 9 4 | Lauryn Slater |

"Harpers" in 1941 called the lobotomy a revolutionary technique. The Saturday Evening Post joined him. Patient testimonies began to appear similar to those we read today: half advertising, half speculation. One such patient, Harry Dannecker, wrote an article in 1945 called "Psychosurgery Cured Me" for the Coronet Magazine. He described his condition before the operation as a hopeless suicidal urge with nothing left to live for; after the lobotomy, he left the "terrible dungeon of the diseased mind." Harry Dannecker plunged headlong into the auto mechanic business, where he claims to have achieved significant success. In his article, he writes: “My goal is simple: to inspire and give courage to those readers who suffer from the same disorders that I had, or whose friends are haunted by painful obsessions.”

In his article, he writes: “My goal is simple: to inspire and give courage to those readers who suffer from the same disorders that I had, or whose friends are haunted by painful obsessions.”

Why then do we continue to regard lobotomy as pure evil? Her vices are obvious: seizures occurred in almost 30% of cases, and her American apostle Freeman, the famous cowboy surgeon with a high scalpel, did not even bother to sterilize instruments or cover the patient with a sheet before a ten-minute operation to cut nerve fibers. . Freeman did a lot to compromise the lobotomy: like modern doctors who prescribe antidepressants as a remedy for any disease, he operated on all patients in a row, although he later showed a certain attention to them - he sent Christmas greetings and visited, traveling in a truck around the whole country.

Despite the reported failures, despite Freeman's myopic approach to seeing the scalpel as a universal remedy, there is no doubt that psychosurgery has helped many people.

| congressional committee formed to ban the opening of Skinner's box

|

found, to her own surprise, that psychosurgery is a well-established procedure of "considerable therapeutic value in the treatment of certain diseases or in the alleviation of certain symptoms." The commission went even further and declared that psychosurgery is a "potentially beneficial method of treatment." Elliot Wallenstein, one of the most vocal critics of the lobotomy, writes: “After the lobotomy, many of the anxiety patients experienced marked relief from their most distressing symptoms. In the best cases, behavior normalized.”

Why did the lobotomy end up in the wastebasket of history, remained a long terrible phase in the development of somatic methods of treatment, a dangerous deviation? Maybe we look at the lobotomy this way because of our brains. Maybe we are programmed to prefer black and white over gray. Perhaps we will never overcome the naive belief that if one thing is bad, the other must be good. We take pleasure in polarization, in making sure that things at opposite ends of the axis are necessarily clear and, it would seem, finally determined. Therefore, in order to recognize the general beneficence of modern psychiatric treatments, we emphasize the barbarity of what they once were. Dark and light. We didn't know what we were doing then, but now we do. We say this while swallowing Prozac, swallowing Ritalin, playing with hormones and hoping that estrogen will make us happy. But are our modern medicines really so different from their former counterparts? Lobotomy has been particularly criticized for its lack of specificity. Surgeons drilled holes, thrust sharp instruments into them, and cut through the unyielding fabric of dreams and thoughts, not knowing what they were cutting. They had vague ideas, of course - something about

Maybe we are programmed to prefer black and white over gray. Perhaps we will never overcome the naive belief that if one thing is bad, the other must be good. We take pleasure in polarization, in making sure that things at opposite ends of the axis are necessarily clear and, it would seem, finally determined. Therefore, in order to recognize the general beneficence of modern psychiatric treatments, we emphasize the barbarity of what they once were. Dark and light. We didn't know what we were doing then, but now we do. We say this while swallowing Prozac, swallowing Ritalin, playing with hormones and hoping that estrogen will make us happy. But are our modern medicines really so different from their former counterparts? Lobotomy has been particularly criticized for its lack of specificity. Surgeons drilled holes, thrust sharp instruments into them, and cut through the unyielding fabric of dreams and thoughts, not knowing what they were cutting. They had vague ideas, of course - something about

2 9 6 Lauryn Slater

thalamus and anterior lobes, emotions and intellect, but they had no idea what undergrowth in the brain was actually uprooted.

For example, if you take modern Prozac... It's praised for its supposed specificity, and we like it. We get the feeling that we know what we are doing, directing projectiles at a clearly defined target in the brain - this is not like a primitive cut with a scalpel. However, the truth is that no one really knows how Prozac affects the brain, no one knows how it works.

“Pharmacological specificity,” says researcher Harold Sackheim, “is a myth.

As with the lobotomy, no one knows exactly why Prozac works. This is about the same blunt instrument as the ones used by Moniz. When doctors prescribe Prozac, they act in the same way that Moniz did - blindly, but with deep faith, with a sincere desire to help ... and relying more on their desires than on facts.

Lobotomy is also criticized because it does not allow you to return to what was. However, who can say whether modern pills do not cause serious and irreparable harm, which we have yet to learn about? Psychiatrist Joseph Glenmullen warns that Prozac use can cause Alzheimer's plaques in the brain; maybe that's why so many prozac users complain about memory—they can't remember anything but

. only where the car keys were put, but also where the car was parked. It is also possible that long-term use of the newest remedies will lead to irreversible dyskinesias, so that twenty years from now a nation relying on Prozac will stumble through unconsciousness. We still take them, these pills, because we feel bad, because there is no other way out - but the patients who went under the lobotomy knife did exactly the same. Did they lose their lives after the operation?

only where the car keys were put, but also where the car was parked. It is also possible that long-term use of the newest remedies will lead to irreversible dyskinesias, so that twenty years from now a nation relying on Prozac will stumble through unconsciousness. We still take them, these pills, because we feel bad, because there is no other way out - but the patients who went under the lobotomy knife did exactly the same. Did they lose their lives after the operation?

| Skinner Opener | 2 9 7 |

spark? This is what caused the most serious objections of the public: by invading the frontal lobes, that part of the brain that is most developed in humans and becomes less and less as we move down the phylogenetic line, doctors invaded the core of the soul and made it empty.

Whether this is true or not is of less interest to us than the fact that the same fears and objections apply to modern methods of treatment. Throughout history, whenever we have been offered the opportunity to achieve psychic well-being, we have immediately become afraid of losing the dividends that darkness brings. Rilke was unwilling to resort to psychoanalysis for fear that he would recover and be unable to write poetry anymore. The hero of the play "Equus", for whom the love of horses is the meaning of life, agrees to psychotherapy and finds that he has been deprived of his passion. Contemporary novelists, athletes, mothers, business people complain that small pills make them "less intense", "less creative".

Throughout history, whenever we have been offered the opportunity to achieve psychic well-being, we have immediately become afraid of losing the dividends that darkness brings. Rilke was unwilling to resort to psychoanalysis for fear that he would recover and be unable to write poetry anymore. The hero of the play "Equus", for whom the love of horses is the meaning of life, agrees to psychotherapy and finds that he has been deprived of his passion. Contemporary novelists, athletes, mothers, business people complain that small pills make them "less intense", "less creative".

When one notices the persistence of complaints about any kind of psychiatric treatment, one begins to think that it is not the intervention as such, but our complex relationship to suffering, which we hate and at the same time consider humanizing us. Whether or not the lobotomy killed the spark of life, perhaps the steps we take today to feel better are doing the same. As to whether a vital spark is necessary for being human, it is better to ask Harry Dannecker or Mrs. M. I think that they, suffering from such serious illnesses, would answer: “Who needs this vital spark? Most importantly, relieve me of these painful symptoms>.

M. I think that they, suffering from such serious illnesses, would answer: “Who needs this vital spark? Most importantly, relieve me of these painful symptoms>.

Unbearable suffering extinguishes the spark...or makes it irrelevant.

- We want to be free from suffering.

| 2 98 | Lauryn Slater |

** *

In 1949, when Moniz was awarded the Nobel Prize for the invention of the lobotomy, it became so popular that twenty thousand operations were performed in the United States alone; The Nation wrote that the emergence of conglomerates of citizens of a country with damaged

causes anxiety in the brain. It is estimated that between 1937 and 1978 thirty-five thousand people were lobotomized in the United States; The greatest peak came at the time of Moniz's Nobel Prize, and after 1950 the number of operations began to decline rapidly - it was then that the first antipsychotic drugs appeared. The 1950s saw the birth of the pharmacotherapy of mental illness, with all its benefits, and this, coupled with the persistent public resentment of the lobotomy, led to its unpopularity. Drugs seemed much more preferable, even though they had such side effects as stupor, sweating, acute motor disturbances. We have chosen to get to our brains through our stomachs rather than directly, just as we often choose to speak terrible truths rather than act.

The 1950s saw the birth of the pharmacotherapy of mental illness, with all its benefits, and this, coupled with the persistent public resentment of the lobotomy, led to its unpopularity. Drugs seemed much more preferable, even though they had such side effects as stupor, sweating, acute motor disturbances. We have chosen to get to our brains through our stomachs rather than directly, just as we often choose to speak terrible truths rather than act.

Other factors were at work. The nation became increasingly suspicious of uncontrolled medical experiments. Stanley Milgram's shock machine has sparked ethical controversy over what is acceptable with test subjects; even more fuss was raised by the Tuskegee experiment, where doctors denied treatment to several Negroes with syphilis in order to be able to observe the degradation of their brains. Perhaps the greatest role was played by the press, which presented pharmacology, as once the lobotomy, as the latest achievement, so that the public became aware of a new object of our hopes and despair.

In the 1970s, less than twenty lobotomies were performed in the country a year, although a small group of neurosurgeons continued to improve the technique, so that the brain was inflicted

| n e ra | 2 9 9 |

less and less damage, and the number of negative side effects decreased accordingly. The 1950s and 1960s saw the development of the stereotaxic method: it became possible to introduce a miniature electrode into the brain that destroys a strictly defined small volume of tissue, in contrast to the more or less blind intervention of a scalpel. In addition, surgeons began to pay more attention not to the frontal lobes, but to the limbic system, also known as the “emotional brain”. They targeted a specific region of the limbic system, the cingulate gyrus, which is thought to be responsible for reducing anxiety. It is important to note, however, that both at the beginning of the lobotomy era and now there is a significant divergence of opinion about which fibers to cut, and this circumstance emphasizes the continuing experimental nature of psychosurgery. Different surgeons show a preference for different brain structures, a preference that precedes familiarity with the patient. Some, for example, believe that amygdalatomy - the removal of the amygdala, a subcortical structure that influences the flow of emotional processes - works wonders, while others continue to consider the cingulate gyrus, and still others the caudate nucleus, to be the most important. The combination of divergence of opinion and a rather dark history of the subject makes the modern lobotomy, often under a different name, the last straw for the most seriously ill patients, a procedure that is ashamed and kept secret.

Different surgeons show a preference for different brain structures, a preference that precedes familiarity with the patient. Some, for example, believe that amygdalatomy - the removal of the amygdala, a subcortical structure that influences the flow of emotional processes - works wonders, while others continue to consider the cingulate gyrus, and still others the caudate nucleus, to be the most important. The combination of divergence of opinion and a rather dark history of the subject makes the modern lobotomy, often under a different name, the last straw for the most seriously ill patients, a procedure that is ashamed and kept secret.

Part Two

The Massachusetts General Hospital is located on Fruit Street on the outskirts of Boston. Its modern buildings and gleaming glass doors contrast with the cobblestone pavements and old houses, each window sill full of colorful flowers in boxes

3 0 0 Lauryn Slater

. If you stop just a block from the hospital, on historic Beacon Hill, you'll never guess how close you are to one of the most technically advanced medical facilities in the country.

It is not easy to undergo psychosurgical intervention in the USA; in some states, including California and Oregon, it is prohibited by law. In the USSR, when it still existed, psychosurgery was completely rejected as inconsistent with Pavlovian teachings. Patients who wish to receive this kind of help have to make great efforts: they must prove that they have exhausted all other possibilities to the ethics committee; only then can holes be drilled in their heads.

Emily Este of Brooklyn, New York, has suffered from depression all her life, but she was unable to obtain the consent of the ethics committee because she had not tried enough electrotherapy sessions. Charlie Newitz of Austin, Texas, on the other hand, got permission. He's had more than thirty shock therapy sessions and tried more than twenty-three drugs: he can list them by bending his fingers—Luvox, Celexa, Lamictal, Effexor, Lithium, Depakote, Prozac, Risperdal, Haldol, Serzon, Zoloft, Remeron, Wellburtin, Cytomel, Dexedrin, Imipramine, Parnate, Nortiptyline, then Razin. .. Charlie recites the names of the drugs as if he were a poem of his own life, a life of disease.

.. Charlie recites the names of the drugs as if he were a poem of his own life, a life of disease.

Charlie is a bear-sized forty-one-year-old man with a hint of a mustache and glassy eyes that seem hazy from all the drugs that he and his psychiatrist poured into his body like a barrel. When Charlie was twenty-two years old and working on an exploration team in Texas, obsessive-compulsive psychosis hit him like a bolt from the blue. An irresistible desire to count, to check, to tap out swallowed up his mind, tied his hands, so that he was unable to do anything - not even a worker.0003

| Skinner Opener | 3 0 1 |

love or love: he seems to be frozen into endlessly repeating rituals.

“It's amazing how unexpected it happened,” says Charlie. Everything was fine with me, but the next day it was gone.

And so it went from then on... A skilled engineer who could tell by the appearance of the rocks whether there was oil underneath, turned into a hermit, hiding in his miserable apartment in Dallas and able only to spin on one leg.

Charlie considers himself unlucky: he was one of the few who did not help with any of the medicines prescribed by his doctor, Dr. Roberts. In some ways he is right, in some ways he is not. Charlie is really unlucky, but there are not so few people who are not helped by drugs, no matter how hard the advertising of pharmaceutical companies tries to convince us otherwise. Psychopharmacologists proudly claim to have opened up a wonderful new world of mental illness treatment, that pea-sized pills have fabulous powers, that they can lift our burdens of confusion and anxiety, help us sleep, energize us, make us more or less sensitive; every pill from every company is packed full of vitamins and proteins that will take us to the skies...

These are the statements of the advertisement, but they lie, and not only because they

• oversimplify the situation. They cause deeper harm. The statistics that pharmaceutical companies and many psychopharmacologists are so fond of citing say that seventy percent of those who take drugs get better . .. well, if thirty percent of the drugs do not help, then there is nothing to worry about: you have a very good chance. However, a closer look reveals a completely different picture. Indeed, seventy percent of those who take drugs have an effect, but only

.. well, if thirty percent of the drugs do not help, then there is nothing to worry about: you have a very good chance. However, a closer look reveals a completely different picture. Indeed, seventy percent of those who take drugs have an effect, but only

| 3 0 2 | Lauryn Slater |

ko for thirty - expressed; for the rest, the effect is indicated as moderate or minimal. By some estimates, sixty percent of those on treatment develop tolerance to the drugs, which eventually renders the drugs useless. Here, do the recalculation. Most people who take pills either stay seriously ill or get some relief, and "some relief" when you're suffering terribly is not something to celebrate. Pharmacology provides assistance, but it is completely insufficient. The statistics should make us wonder why we both criticize psychosurgery and respect its place in modern medicine.

Charlie Nevitz and Dr.