Catfish personality disorder

Understanding the Psychology of Catfishing

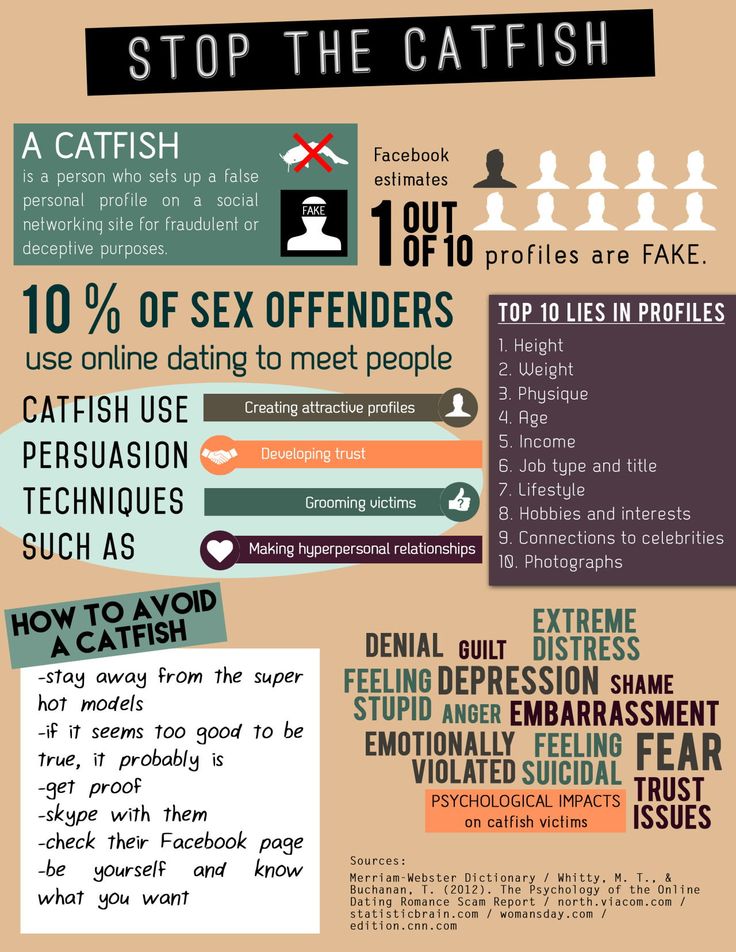

This past Valentine’s Day, the Federal Trade Commission released a warning that online romance scams were at an all-time high. These scams involved a predator adopting a fake persona and pursuing an online relationship with an unsuspecting victim.

Online romance scams are also known as “catfishing,” based on the 2010 documentary (and subsequent MTV reality series) about a young man who believed he was communicating with a Michigan woman named “Megan.” In reality, Megan was Angela, a married woman in her 40s who used photos she found online to construct a complex, fictional persona. Megan felt very real to her victim, who spent months texting, emailing and speaking with her. Angela also created dozens of Facebook profiles for Megan’s supposed family members, and she later admitted her characters felt very real to her, as well.

Social scientists understand many of the reasons why perpetrators catfish. Catfishing predators often say their own troubles lead them to adopt fake personas for entertainment purposes, to make themselves seem more attractive or to bully others. Other times, predators build the relationship with the intent of asking the victim for money. In 2021, those targeted by online romance scams lost a median of $2,400.

But why do their victims fall for the scam? There are several theories about what motivates a victim to continue a questionable digital relationship. These theories involve psychological processes that operate deep in the subconscious, which means victims can be unaware when they are in the midst of a catfishing scam — and lack understanding about how they fell prey in the first place.

‘You Should Run’

On the MTV reality series Catfish: The TV Show, multiple hosts help young people who are in an online relationship they suspect might be fake. On the show, victims often admit they never video call with their supposed romantic partner, and they accept their excuses for this; say, that the other person’s web camera is broken. Victims also reveal they never meet in-person with their online love interest, even when they live in the same city.

One of the series’ earlier hosts often became frustrated by the victims’ ongoing tolerance for excuses and once exclaimed: “Time out. If you are talking to someone who lives in your city, and they don’t want to meet up with you, they are a catfish and you should run.”

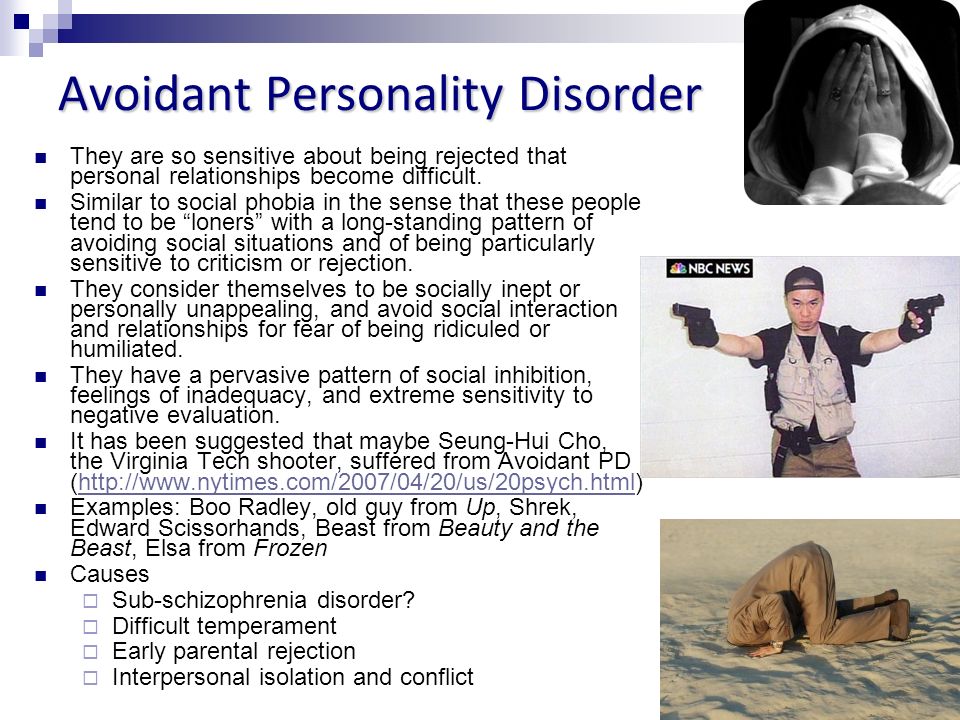

So why don’t the victims run? Scientists studying attachment theory have suggested that these victims may struggle to form romantic ties in real life, and thus subconsciously seek to keep potential partners at a distance. Attachment theory was first explored by in the aftermath of World War II, when psychologist John Bowlby was investigating how babies bonded with their mothers. While it was initially used to study the ways that children become attached to their caregivers, in the 1980s, that framework expanded to include bonds among adults, like romantic relationships.

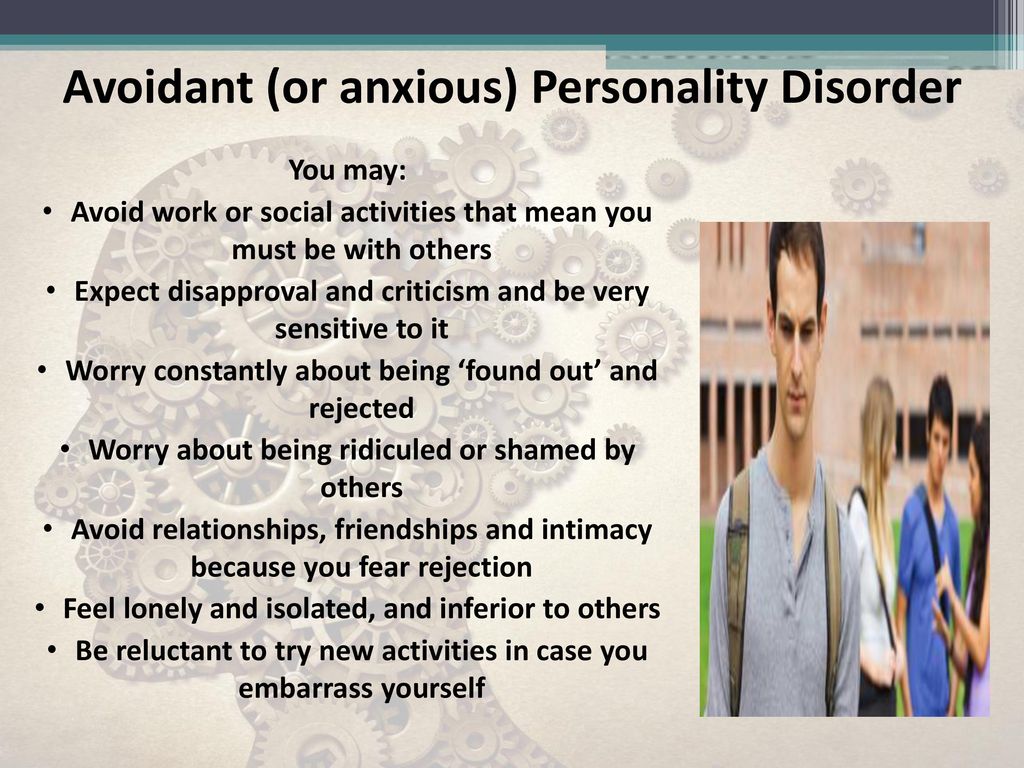

It wasn't until 2020 that researchers used attachment theory as a lens for interpreting the motivations of catfishing victims, according to a study published in Sexual and Relationship Theory that year. The scientists surveyed 1,107 adults with an average age of 24.9 years, where almost 75 percent described themselves as a victim of a catfish scam. The participants filled out an assessment to determine their attachment style, which can be categorized as avoidant, anxious or secure. The researchers found that having an anxious attachment style — often expressed as clinginess in romantic relationships — was a predictor for being a catfish target. Beyond that, having both high avoidance and high anxiety increased their likelihood of being a victim.

The scientists surveyed 1,107 adults with an average age of 24.9 years, where almost 75 percent described themselves as a victim of a catfish scam. The participants filled out an assessment to determine their attachment style, which can be categorized as avoidant, anxious or secure. The researchers found that having an anxious attachment style — often expressed as clinginess in romantic relationships — was a predictor for being a catfish target. Beyond that, having both high avoidance and high anxiety increased their likelihood of being a victim.

The participants with both avoidant and and anxious attachment styles, the study authors suggested, were drawn to online-only relationships because they allowed the victim to be regularly “soothed from a safe distance” while maintaining a comfortable commitment level.

Other studies have supported these findings, and surveys with victims of online romance scams have found they expressed high levels of loneliness and low levels of openness, meaning they sought relationships with others but had trouble connecting. The online romance filled the void, even if it wasn’t real.

The online romance filled the void, even if it wasn’t real.

A Love Story

Scholars who study scams have found the swindlers often create convincing scenarios that lead the victim to err in their decision making. Online relationship researcher Monica Whitty applied a theory of decision making called the Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM) to digital romance scams to test that idea. ELM holds that people have different ways of processing information: either central or peripheral. With the central route, a person carefully considers the situation and elaborates in their thought process. With the peripheral route, the person relies on associations they have made with certain cues related to the message.

In a study published in the British Journal of Criminology, Whitty argued that ELM can be applied to catfish victims. She interviewed 20 catfish victims — with the longest fake relationship lasting three years — and found they tended to hold romanticized beliefs about their scammer. Within the ELM framework, Whitty suggested the victims used the peripheral route when processing the messages they received. In other words, they paid more attention to the romantic messages themselves, and ignored any troubling content not consistent with the idealized narrative they had created.

Within the ELM framework, Whitty suggested the victims used the peripheral route when processing the messages they received. In other words, they paid more attention to the romantic messages themselves, and ignored any troubling content not consistent with the idealized narrative they had created.

Several of the victims, for example, thought they were in an online relationship with an American soldier stationed in Iraq. They believed their supposed soldier was going to soon retire from the military, move to the UK, and marry them. The victims then focused on the romantic messages consistent with both the soldier’s narrative and their romanticized ideals. They ignored red flags, like the soldier asking for money for a plane ticket or to ship his luggage.

Many of the victims refused to acknowledge the romance was a scam, even after authorities became involved. Victims in other studies also describe the loss of the relationship as a death, with some more upset at the loss of the relationship itself than any financial losses, regardless of how much lighter their wallet became.

Catfishing’s Effects On Your Brain, According To Experts

In the internet age, nearly everybody has some kind of catfishing story — a paramour on a dating app who turned out to be an entirely different person, an aunt duped by handsome photos, some pre-teen bullies pretending to be somebody’s crush over Snapchat. Catfishing, where a person assumes an entirely different identity online to befriend or romance others, first became a mainstream term in 2010, when a documentary by Nev Schulman revealed that the woman he’d been romancing online for months was in fact an older woman using photographs of a model. Now, shows like Catfish UK and The Circle are built around the effects of playing another person online, and reports suggest that catfishing may have risen during the COVID pandemic, with people restricted from face-to-face meetings. Experts tell Bustle that the psychology of catfishing reveals a lot about the brain, from the impact of betrayal to the realities of pathological liars.

The Psychology Of Catfishers

It can be hard to get into the brain of a catfish, but research can help. A study published in Sexual & Relationship Therapy in 2020 found that men are more likely than women to be catfishers, and that people who had anxious attachment styles — meaning they found it hard to feel secure or loved in a relationship, and needed reassurance and attention — were more likely both to catfish and be catfished.

An investigation of 27 catfishers by researchers at the University of Queensland also found that they were motivated by loneliness, struggles with social connection, dissatisfaction with their bodies, a desire to escape, or a need to explore aspects of their gender or sexual identity. While some were wracked with guilt and wished to confess, others said they started doing it for a practical reason, like getting access to an age-restricted website. Media stories about catfish often revolve around monetary gain, but these people didn’t really fit that stereotype; they exploited the trust of others for psychological reasons. Scientific American also notes that catfish can be motivated by a phenomenon called the “online disinhibition effect,” where online anonymity makes people less likely to adhere to the moral codes they use in real life.

Scientific American also notes that catfish can be motivated by a phenomenon called the “online disinhibition effect,” where online anonymity makes people less likely to adhere to the moral codes they use in real life.

Lying repeatedly can change the brain gradually, too. “We learn to lie over time by the way it rewards or punishes us,” neuropsychologist Dr. Sanam Hafeez Ph.D. tells Bustle. “Researchers have also found that the part of the brain, the amygdala, that would otherwise send out guilt signals, stops responding when a liar becomes a natural at deceiving.” That means they don’t feel discomfort about lying, whether they get caught or not.

What Being Catfished Does To Your Brain

If you discover that the cottagecore angel you’ve been falling for on Snapchat is in fact a total illusion — and using your trust for their own gain — you’ll likely feel completely shattered. And your brain will reflect that. “When we are betrayed, our brains show an elevation in stress, likely an overproduction of stress hormones to combat this perception of an 'attack', hypervigilance, and anxiety,” Dr. Hafeez says.

Hafeez says.

A partner revealed to be a catfish can also alter brain activity in the future. “Our brains have set paths that help us to operate, with thousands of automatic thoughts and assumptions every day,” Catherine Richardson LPC, a Talkspace therapist, tells Bustle. “When it comes to relationships, if there has been trust, we assume there will continue to be trust, until that trust is broken.” Being catfished, she says, may create new brain pathways that cause people to distrust what that person, and future partners, say and do. That can make people more vulnerable to paranoia and pessimism.

“Our brains are wired to seek out people who will protect us from harm, and when we are betrayed, this cycle is disrupted,” Dr. Hafeez says. People who are prone to anxiety or depression may be more deeply impacted by the trauma of catfishing, she says, and the continual suspicion of others may be harder to heal.

How To Heal From Being Catfished

“In order to heal from a betrayal, you first have to name the feelings that are coming up,” Richardson says. These could be hurt, anger, confusion, or other emotions. It can be a long process to heal from catfishing, but Richardson recommend that people use some self-reflection alongside anger, including asking themselves honestly about warning signs that they didn’t notice or ignored.

These could be hurt, anger, confusion, or other emotions. It can be a long process to heal from catfishing, but Richardson recommend that people use some self-reflection alongside anger, including asking themselves honestly about warning signs that they didn’t notice or ignored.

“These questions are not meant to shame you but to help you grow,” she says. “Being lied to is devastating in any situation, but you can use the experience to learn more about yourself and how you interact with others.” Anybody who’s struggling with the after-effects of catfishing can also seek professional support from a therapist, who can help them learn to trust again.

Experts:

Dr. Sanam Hafeez Ph.D.

Catherine Richardson LPC

Studies cited:

Garrett, N., Lazzaro, S. C., Ariely, D., & Sharot, T. (2016). The brain adapts to dishonesty. Nature neuroscience, 19(12), 1727–1732. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4426

Mosley, M. A., Lancaster, M., Parker, M.L., & Campbell, K. (2020) Adult attachment and online dating deception: a theory modernized. Sexual and Relationship Therapy,35:2,227-243,DOI: 10.1080/14681994.2020.1714577

A., Lancaster, M., Parker, M.L., & Campbell, K. (2020) Adult attachment and online dating deception: a theory modernized. Sexual and Relationship Therapy,35:2,227-243,DOI: 10.1080/14681994.2020.1714577

Yang, Y., Raine, A., Narr, K. L., Lencz, T., LaCasse, L., Colletti, P., & Toga, A. W. (2007). Localisation of increased prefrontal white matter in pathological liars. The British journal of psychiatry : the journal of mental science, 190, 174–175. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.025056

3 Disorders We Must Stop Hating"

When I was 19, I enrolled in the Abnormal Psychology course. It was a review course on mental disorders and was the first step on my path to becoming a social worker and a psychotherapist

Although at the time I wasn't particularly interested in learning how to analyze others, I was interested in understanding myself

All my life I had problems with behavior and emotions that I knew were "bad ", but I couldn't control them.

I compulsively lied about nonsensical things. I was so afraid that other people would leave me that I could get angry with them, sometimes with rage and insults, if I thought that my friends were walking without me. I was full of self-hatred and anger that built up inside of me and then turned into self-harm.

I was charming and made friends easily, but friendships never lasted more than a year or two - and every time my friends left, I hated myself so much that I wanted to die.

Of course I grew up as a secretive trans girl of color in a white cis supremacy society. For as long as I can remember I have been filled with rage, fear and self-hatred due to constant messages from society and family that I am perverted, bad and completely wrong.

Many of my fellow psychotherapists joke that we choose this profession to heal ourselves first. Remembering my studies, I definitely looked for myself in that textbook "Anomalous Psychology" - I needed answers to questions that I had struggled with all my life.

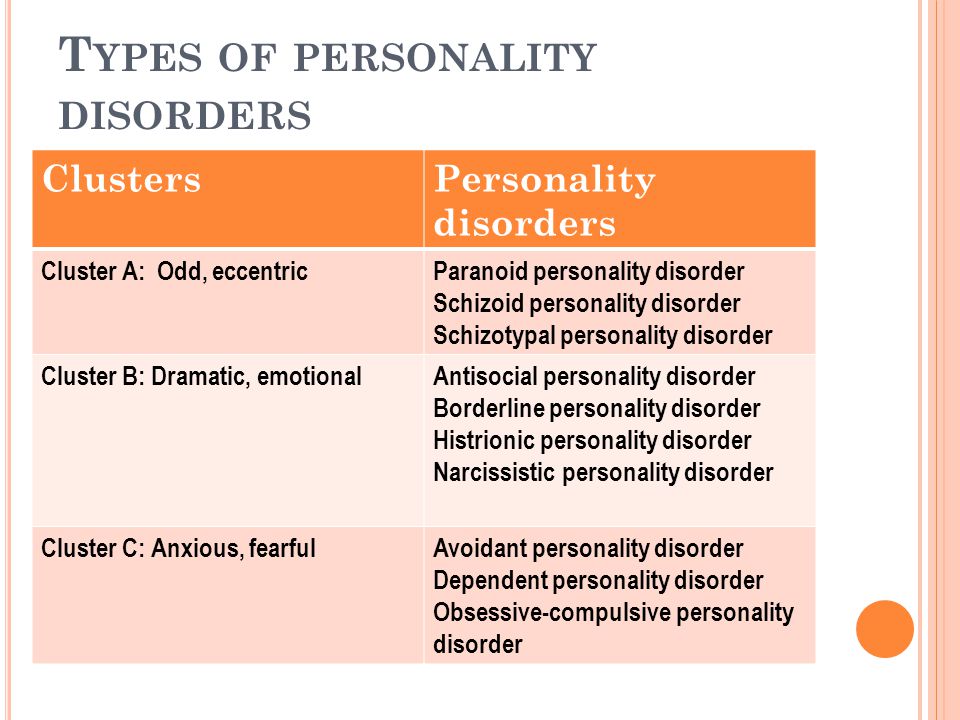

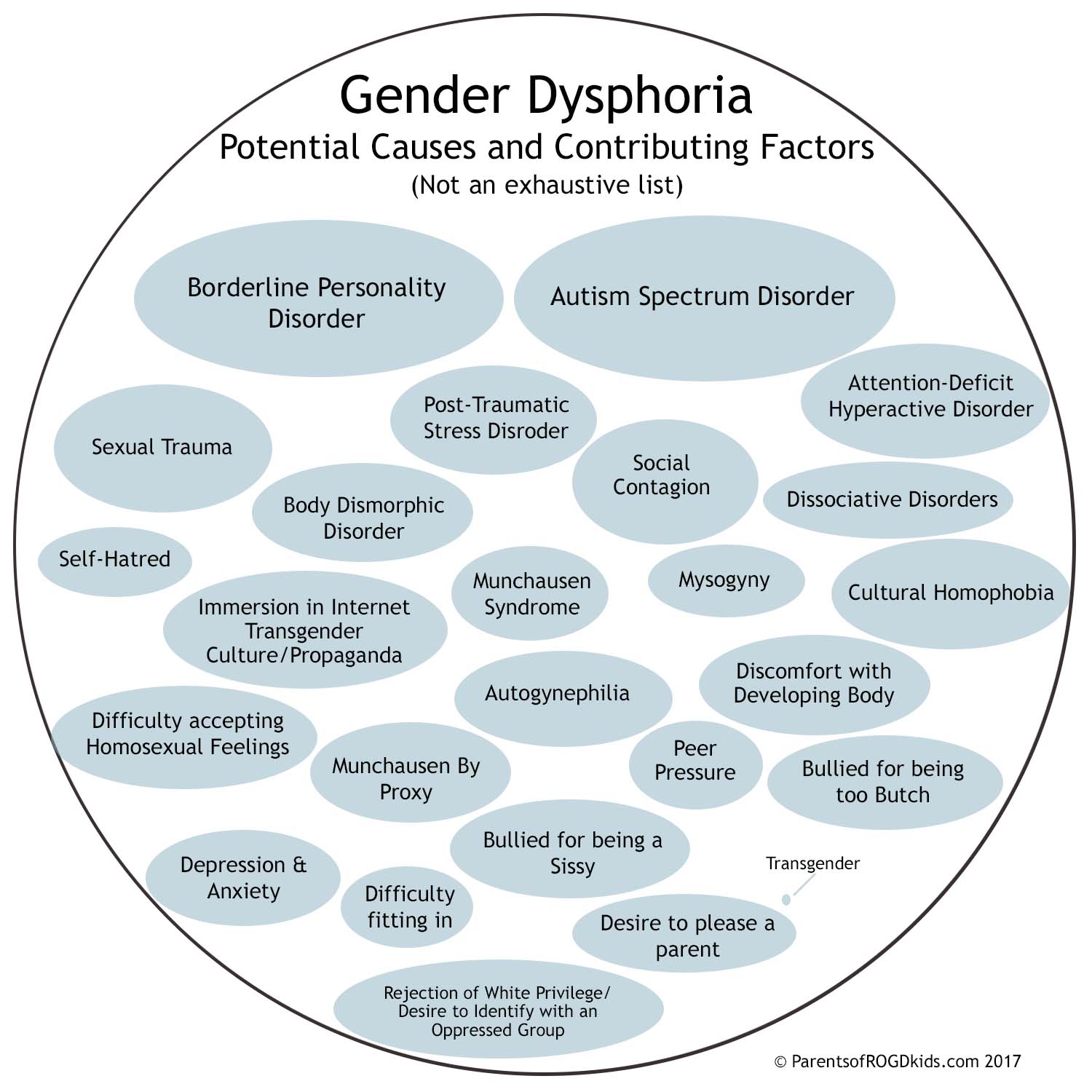

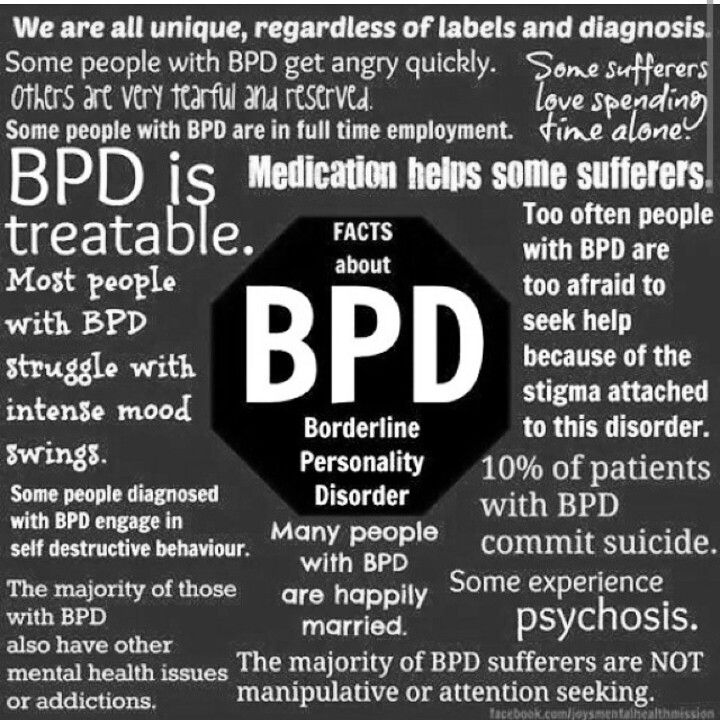

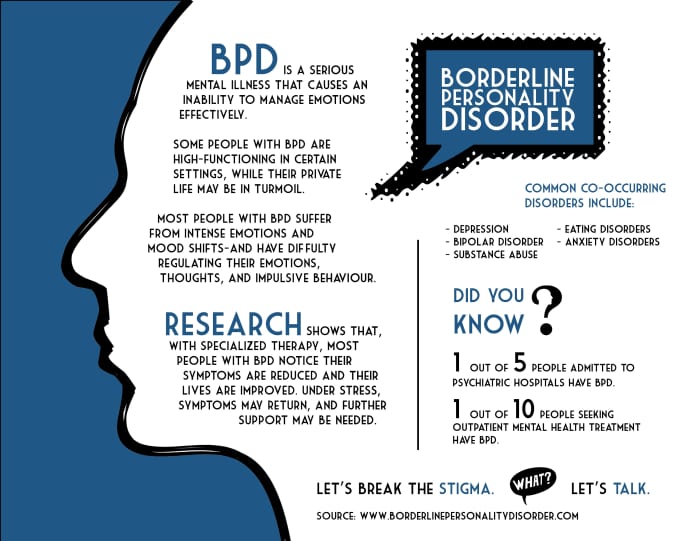

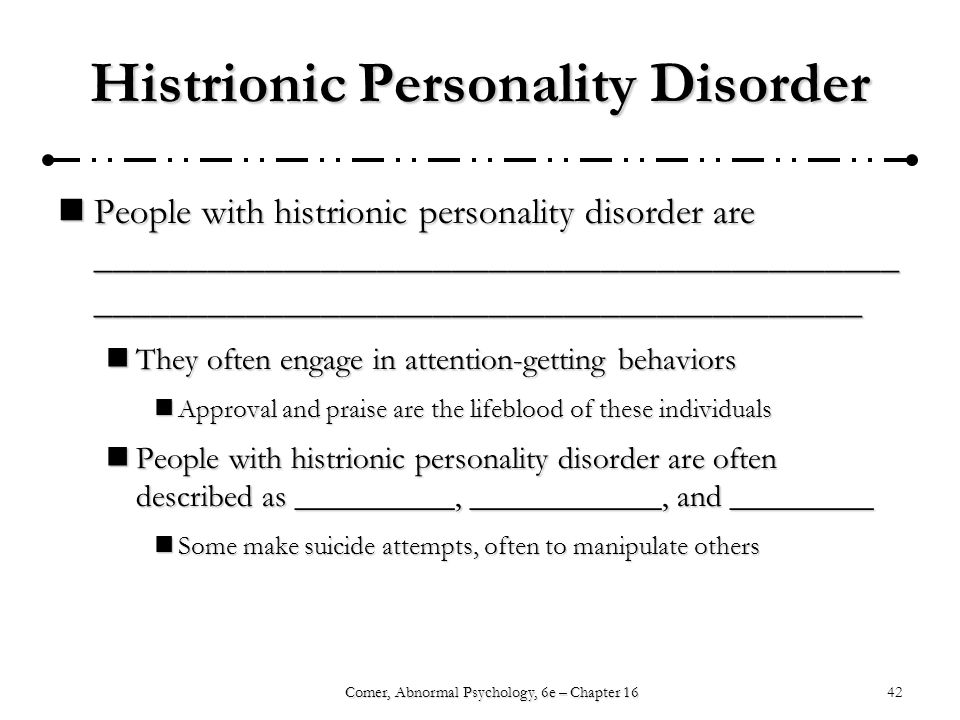

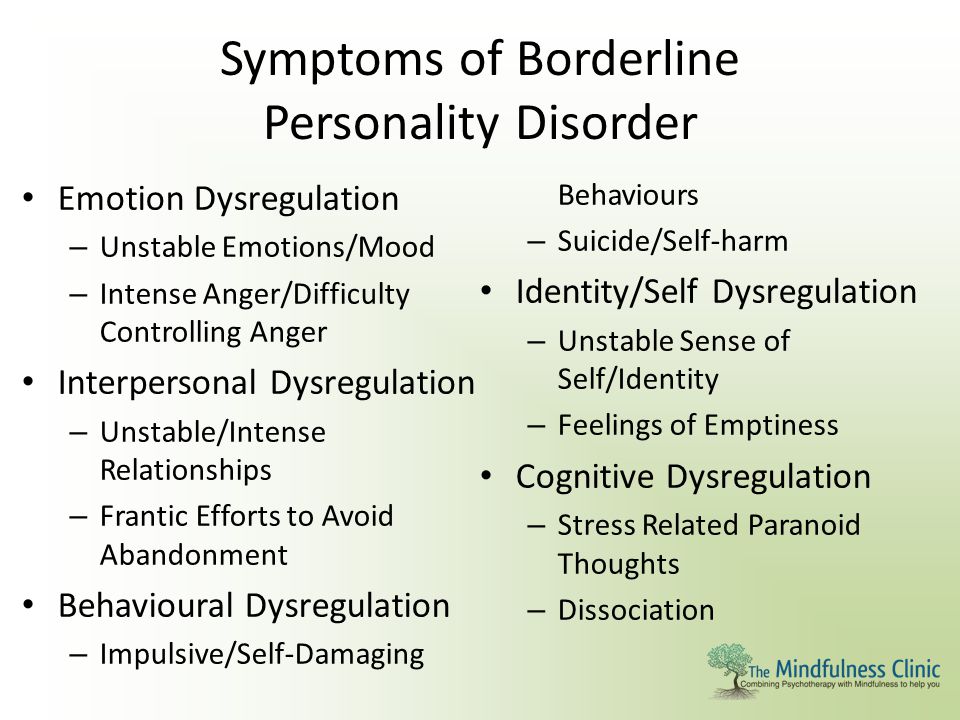

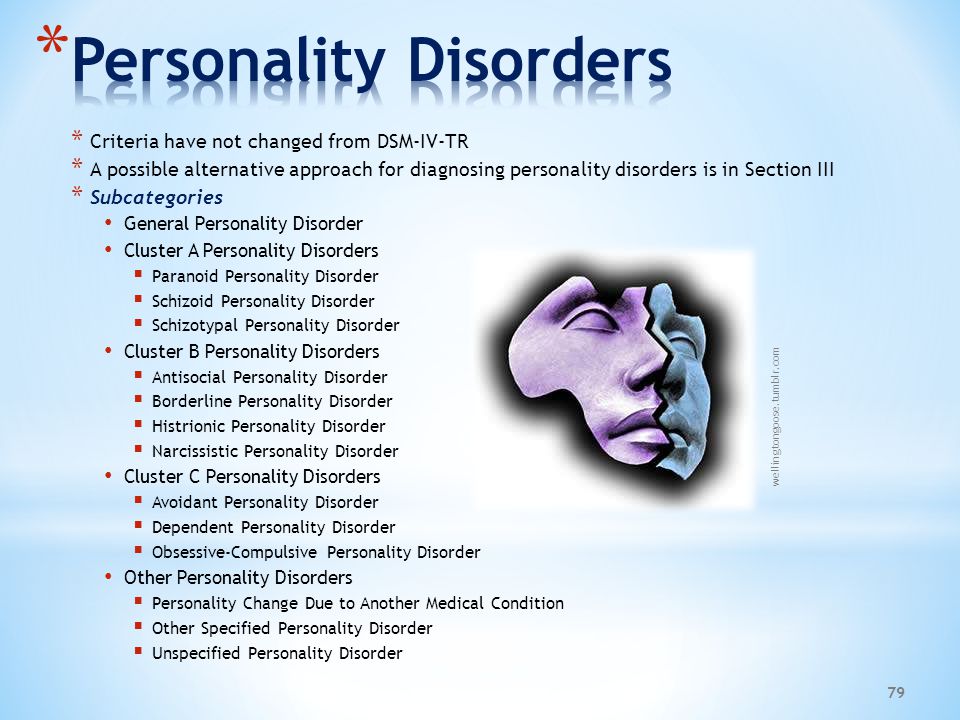

I found the answers in that textbook, subtitled "Personality Disorders Cluster B". My symptoms fit the profile of a mental disorder called Borderline Personality Disorder, a condition associated with psychopathy. And the textbook said that this disorder was considered incurable.

As a responsible mental health professional, I must say that I would not recommend that you self-diagnose using an introductory textbook. Don't try this at home.

I want to write about the experience of living with mental problems that are considered "ugly" or socially undesirable in society. About living with disorders like psychopathy or paranoid schizophrenia, which are usually considered bad, weird, dangerous and disgusting - even in those social circles that consider themselves "progressive" in matters of mental health.

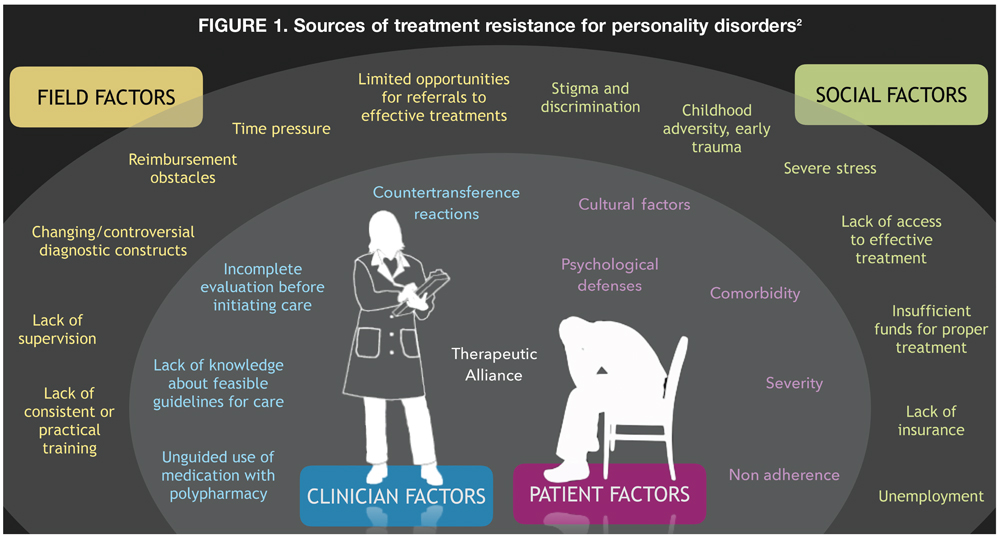

I want to focus on the fact that social systems that oppress us, such as poverty, racism, and systemic violence, as well as childhood traumas, such as abuse and neglect, are actually responsible for creating and maintaining the symptoms of the most hated and frightening mental disorders.

Stigma accompanies all mental disorders to some extent. But in recent years some disorders have been better represented. For example, depression is often covered in the media, from webcomics to full-length documentaries.

Typically these references followed the trend of social activism to destigmatize emotional disorders. They refuted the notion that people with depression were to blame and argued that depression was caused by a chemical imbalance in the brain.

However, this media attitude and public dialogue rarely extends to those mental disorders that are not so easy to empathize with. I would say that many people sympathize with people with depression, because they themselves felt depressed at some point in their lives.

I doubt that as many people will say they sympathize with psychopaths, pathological liars, or narcissists.

In a society in love with the rhetoric of positive thinking, so-called "toxic people" like people with these disorders have become the scarecrows and horrors of any mental health conversation - despite the fact that almost one in ten people in the United States have traits associated with with these disorders.

On the other hand, popular culture is obsessed with caricatured and fetishized representations of psychopathy and psychosis, examples of which can be seen in film and television throughout the 20th century: Dexter, Girl, Interrupted, Law & Order, The Silence of the Lambs ", "Hannibal" are just a few names that come to mind.

It would be politically incorrect to claim (at least in the leftist circles in which I move) that people with depression and anxiety are bad and do not deserve sympathy and support.

But the worst part is that even the most correct social justice activists can use the term "psychopath" as an accusation.

It's the same with psychiatrists who use terms like "borderline patient" as a synonym for "recalcitrant patient I don't like."

As a child psychiatric social worker, I have heard professionals talk about aggressive or manipulative children, some as young as 5, using words like "talented psychopaths", "bad business" or "future killers".

And almost always no one thinks about the fact that people are not aggressive or manipulative just like that. There are no “just evil” people who were born to harm others. An aggressive or manipulative personality most often results from a combination of childhood trauma, other environmental trauma, and genetic vulnerabilities. are not acceptable, we need to find ways to understand why people become violent, manipulative and abusive in order to help them stop - because imprisonment and ostracism are completely inappropriate measures.0003

The social determinants of health, such as access to housing, education, nutrition, upbringing, and health care, are essential to maintaining the conditions that allow people to develop mentally in a pro-social and non-violent manner.

If you look under aggression and manipulation, there is always fear, and often trauma. When we open ourselves to this world, we create the opportunity to help others heal from trauma, aggressiveness and manipulativeness - and we can see and heal our distortions as well.

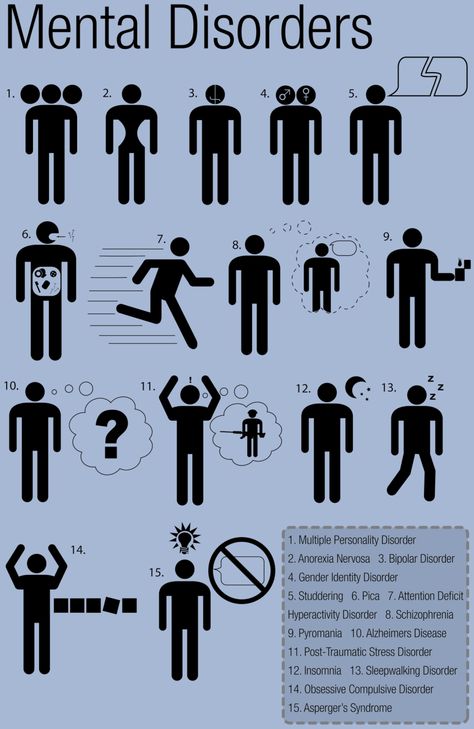

The following three mental disorders are commonly misunderstood and vilified by society - and here's how to think about them with compassion.

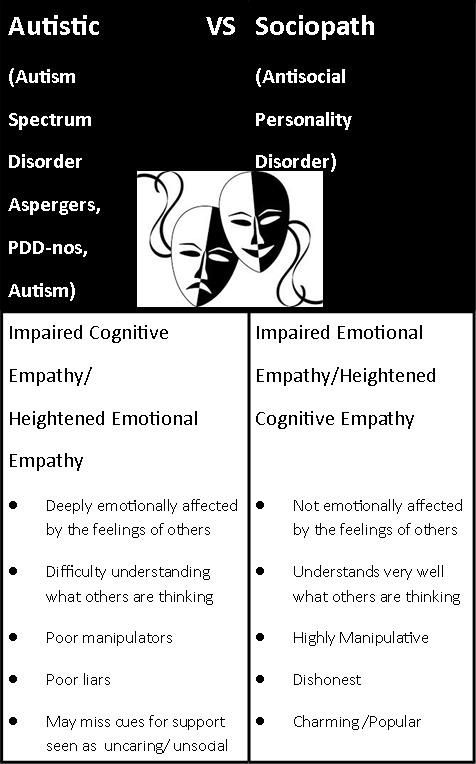

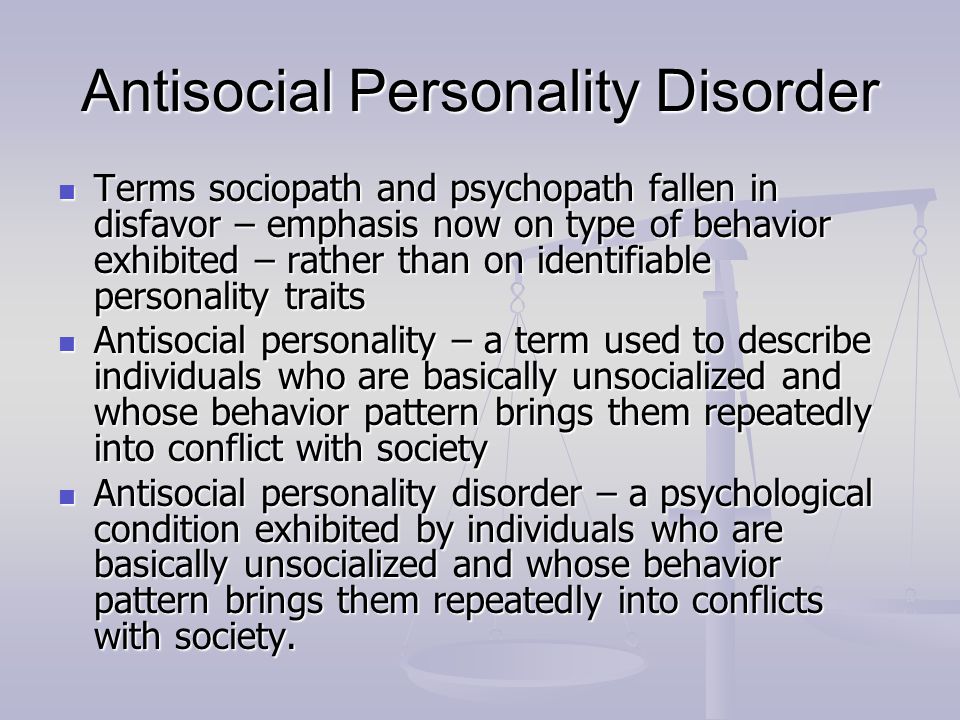

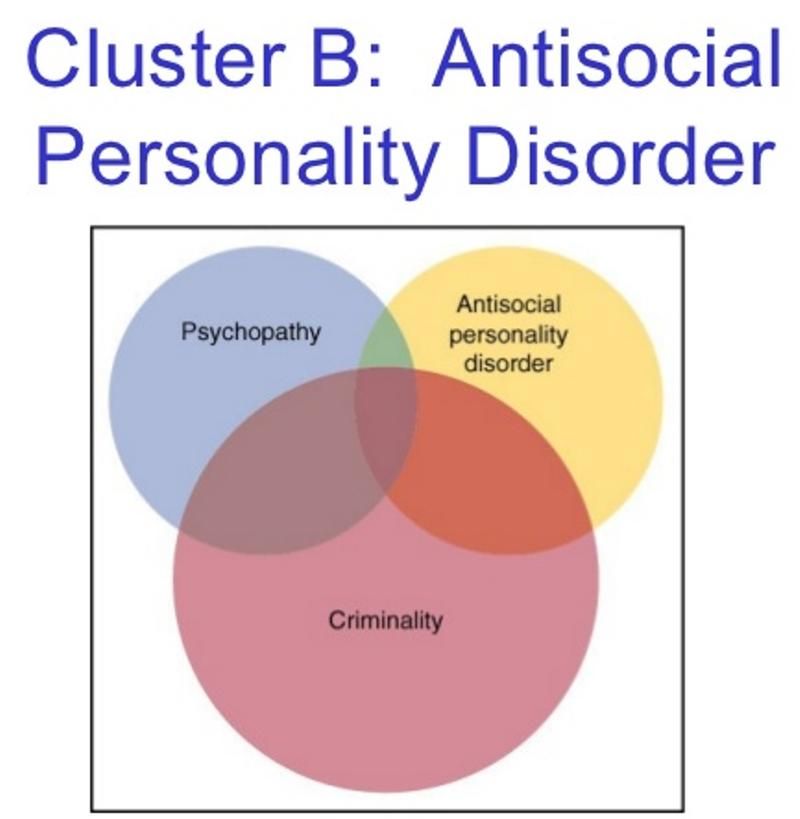

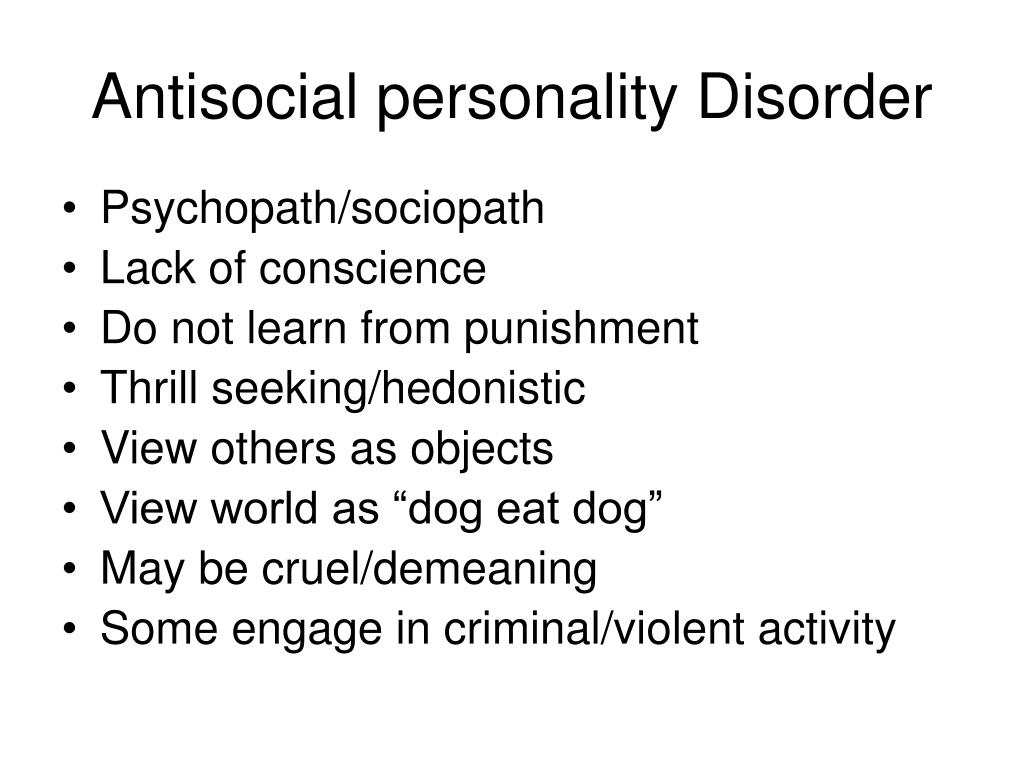

1. "Psychopathy", "sociopathy" or antisocial personality disorder.

Perhaps no other psychological term fires the public imagination more than the terms "psychopath" and "sociopath." In popular usage, the words have become associated with anything from high school bullies to Hollywood supervillains to serial killer myths.

All this hype tells us that psychopaths and sociopaths are predators, wolves in sheep's clothing, who walk among us unnoticed, and are constantly looking for an opportunity to lure unsuspecting people into their devilish games.

With so much media attention on psychopathy and sociopathy, it may come as a surprise to you that neither clinical psychology nor psychiatry has ever considered "psychopathy" and "sociopathy" to be real diagnoses.

Indeed, all these stories about psychopathic killers and "crazy exes" only support a fantasy, a cultural construct that has no roots in real psychiatric science.

A real diagnostic term that comes close to these ideas of psychopathy and sociopathy is antisocial personality disorder. This disorder is characterized by difficulty forming relationships, violent and impulsive behavior, and a marked lack of remorse or concern for others. People diagnosed with antisocial disorder are often involved in criminal offenses ranging from "petty" assaults to a series of murders.

But antisocial personality disorder does not occur in a vacuum. Research has shown that in adulthood this disorder is highly correlated with being the victim of childhood trauma, abuse, and neglect.

People with antisocial traits react to the external world with an intensity and violence that is consistent with their internal experience of insecurity - that sense of physical insecurity that is ingrained in their psyche.

Of course, this does not justify their violent behavior. But it helps us understand that violence is a symptom of a system that is larger than individuals. And mindless hatred and rejection of those people we consider too aggressive to function in society may not be a good enough solution.

We need to stop relying on the psychiatric practice of involuntary hospitalization and the prison system to cleanse society of all the violence they create.

We need to find better ways to understand each other and live together.

2. Borderline personality disorder

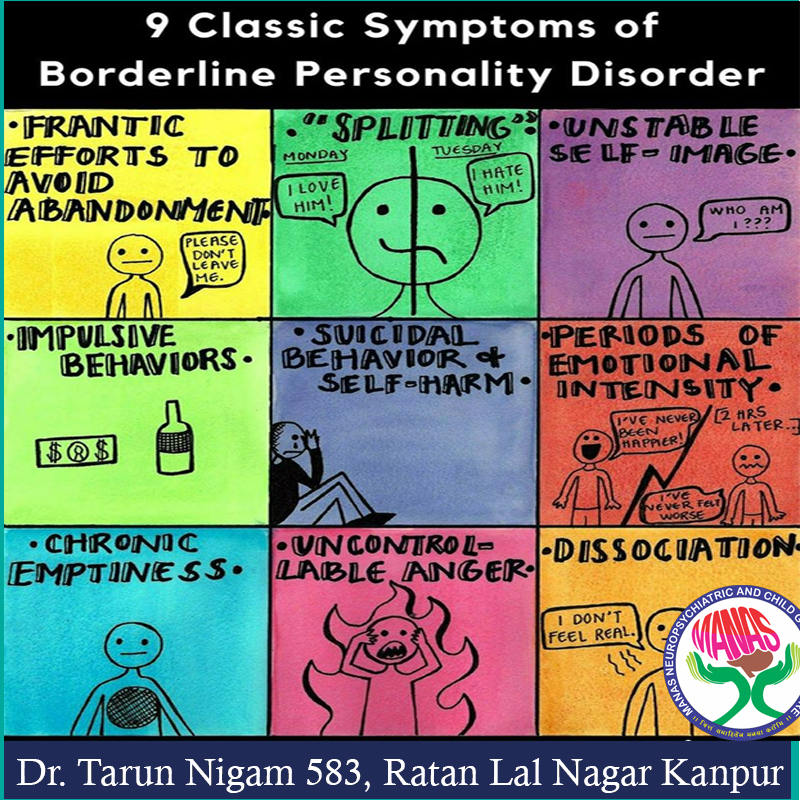

Another mental disorder closely related to the cultural concept of psychopathy is borderline personality disorder. This diagnosis is associated with emotional instability and self-loathing, with a strong sense of inner emptiness and desire for intimacy, with the manipulation of other people and self-harm.

Common cultural tropes associated with borderline personality disorder include "crazy ex", "crazy mother" and almost all "crazy women" stereotypes.

It is no coincidence that the vast majority of patients diagnosed with borderline disorder are women—this in itself indicates that there is more going on than meets the eye.

In professional psychiatric culture, borderline patients are considered the scourge of most physicians. For example, if some of the patients are difficult to work with, if they are rude, then most likely they will be dismissively called "borderline" at some meeting of the clinical team.

This contempt also exists in popular culture, where borderline people are often seen as "too needy", "toxic", and/or "emotionally manipulative".

What is usually not mentioned about borderline personality disorder is that it is highly correlated with trauma experiences, especially sexual abuse and childhood deprivation.

And this is where my inner feminist is bound to intervene: what if the diagnosis of borderline disorder is just a sexist way of discounting women's and other people's healthy reactions to traumatic experiences by calling these reactions mental illness?

Of course, this is not the first time psychiatric discourse has been used to maintain a patriarchal dominion over women's physical and mental realities—there were times when women who claimed to have been sexually abused by their husband or father were diagnosed as "hysterical. "

"

When I think about my childhood and how my life experiences contributed to who I am today, it really makes sense that I fit the borderline personality disorder profile (and it's amazing that no one had diagnosed me with this before). how I found it).

Here's the thing - it makes sense for you to become a liar if you are told that your truth is bad, worthless, and that it will only hurt you.

It makes sense for you to manipulate others into giving you love if you could never get it in any other way. It makes sense for you to hate yourself and hurt yourself if no one bothered to tell you that the bad things that happened to you weren't always your fault.

Sometimes I wonder who is really "sick"? People who have experienced psychological and physical suffering that cause them to react with rage, fear and even violence to the traumatic actions of a society that oppresses them?

Are people sick who are stigmatized, sensitized and criminalized beyond measure, and who have no hope of receiving adequate and compassionate mental health care?

Or is this society really sick?

Is the borderline a mental disorder, or is it just how people react to it? You decide.

3. Psychosis

In the mid-1950s, my grandmother moved from China to a small town in rural Canada. She did not speak English, she had no friends or work, and she was cut off from most of her family.

Shortly after arriving there, she developed a severe psychosis - what is described in psychiatry as a "break with reality" - which remained with her for the rest of her life.

At her worst, she was mercilessly paranoid, incomprehensible, and angry at the world.

To this day, the stigma and fear that surrounds this story continues to haunt my family. Even many years later, it still remains a fresh, raw wound. In my work as a psychotherapist, I have come to understand that the same aura of shame arises in many families in which one or more relatives have experienced psychosis.

Psychosis is usually defined as the experience of hallucinations (seeing, hearing, feeling, smelling, or tasting things that "are not really there") and/or delusions (beliefs that are inconsistent with popular notions of reality - such as belief that you are God, or that you are contacted by aliens from outer space).

Being a part of many mental disorders such as schizophrenia, schizophrenic disorder, mania and others, it is often considered a sign of the most severe psychiatric illnesses.

Such “crazy” is not only difficult to hide, but it is also the most frequently rejected by society, perceived as something frightening, bizarre, dangerous and disgusting.

People with psychosis, often misinterpreted as very violent by the public and law enforcement, are actually no more violent than anyone else. But this does not protect them from excessive job and housing discrimination, as well as from police brutality and imprisonment.

Not surprisingly, we don't see psychosis mentioned in the same mental health campaigns that advocate destigmatizing depression, anxiety, and other "common" disorders.

It's hard enough to publicize even for those mental disorders that prevent people from being happy or socializing in groups - and it's almost impossible to get public sympathy for the disorders that force people to live in alternate realities.

People with psychosis are commonly referred to as "morons", "nuts", "lunatics", and other derogatory terms for mental illness. I hear this all the time in both casual and professional conversations.

And quietly and imperceptibly I remember my grandmother - a young girl, alone, frightened, suffering in a foreign country from poverty, sexism and racism, and infected with nightmares and voices. I think that psychosis is often inherited between generations.

And I wonder how much her "madness" was caused by the circumstances of her life - oppression and systemic violence, apathy and rejection from the people around her?

And the interesting thing is that if I ever have grandchildren, will they think of me, their crazy grandmother, with pride instead of shame.

Love the madness

Nothing is easy when it comes to complex mental disorders—no easy answers, no political slogans, no webcomics and awareness campaigns that could fully capture the complex reality of living with a disorder considered scary or harmful to others.

According to Jade Campbell, writer and mother:

"It's easy to share memes on Facebook that you support mental illness. But until you've met them in person, you won't know what it is. Would you support them if a mental illness incident happened right in front of you?" "Will you feel compassion, or condemnation?"

The truth is that many of us, and many of those we love, live in fear of our own minds. We live in horror at the possibility that we, too, can be "spoiled" people, incapable of bringing anything but pain and shame to ourselves and others.

I believe that no one "goes crazy" just like that - we live in a society that creates insanity in people with its ability to hurt them, and with its denial and refusal of its own complicity in creating people prone to violations and violence.

If everyone had access to security and health care, if society were more open to a variety of psychological experiences and manifestations, then I doubt that such mental disorders would exist at all.