Can ms cause bipolar disorder

Bipolar Disorder and Multiple Sclerosis: A Case Series

Behav Neurol. 2014; 2014: 536503.

Published online 2014 Mar 17. doi: 10.1155/2014/536503

,,,,,, and *

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

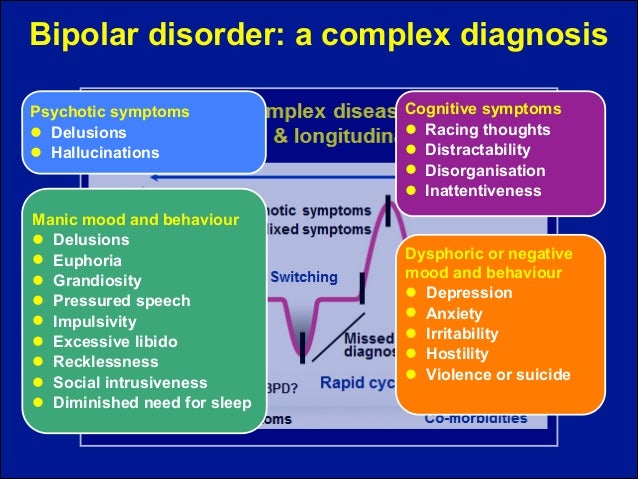

Background. The prevalence of psychiatric disturbance for patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) is higher than that observed in other chronic health conditions. We report three cases of MS and bipolar disorder and we discuss the possible etiological hypothesis and treatment options. Observations. All patients fulfilled the McDonald criteria for MS. Two patients were followed up in psychiatry for manic or depressive symptoms before developing MS. A third patient was diagnosed with MS and developed deferred psychotic symptoms. Some clinical and radiological features are highlighted in our patients: one manic episode induced by high dose corticosteroids and one case of a new orbitofrontal MRI lesion concomitant with the emergence of psychiatric symptoms.

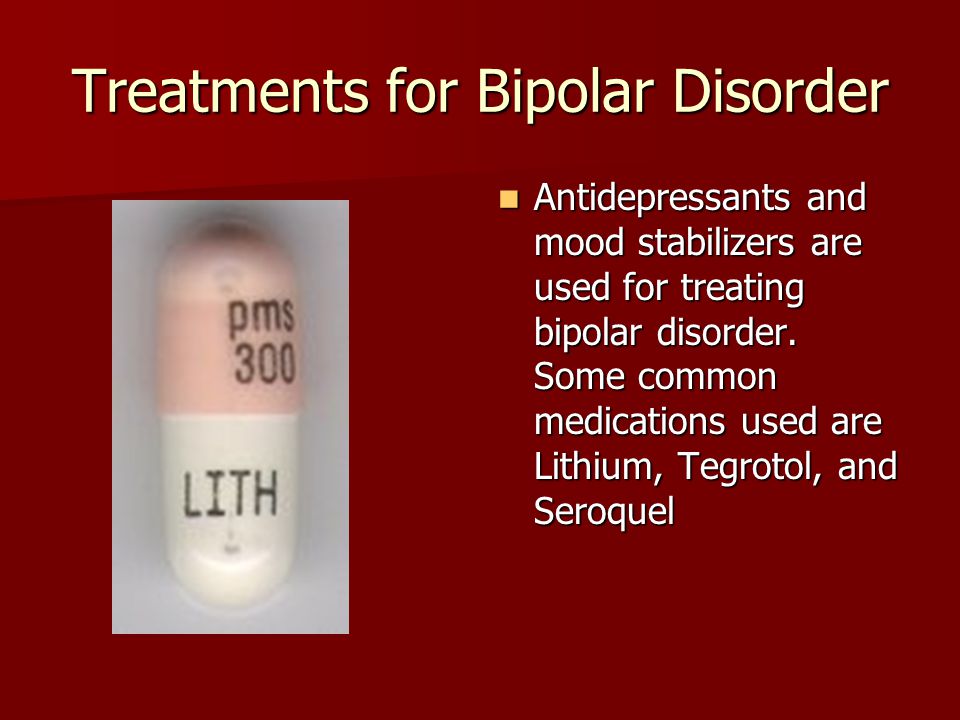

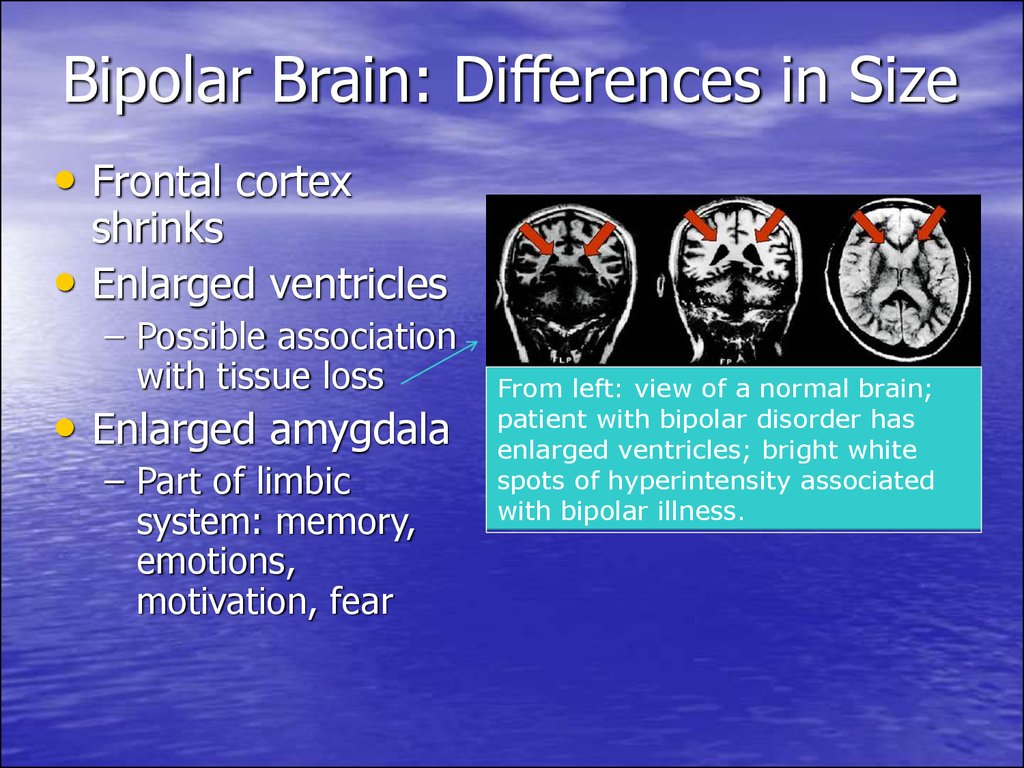

All patients needed antipsychotic treatment with almost good tolerance for high dose corticosteroids and interferon beta treatment. Conclusions. MRI lesions suggest the possible implication of local MS-related brain damage in development of pure “psychiatric fits” in MS. Genetic susceptibility is another hypothesis for this association. We have noticed that interferon beta treatments were well tolerated while high dose corticosteroids may induce manic fits.

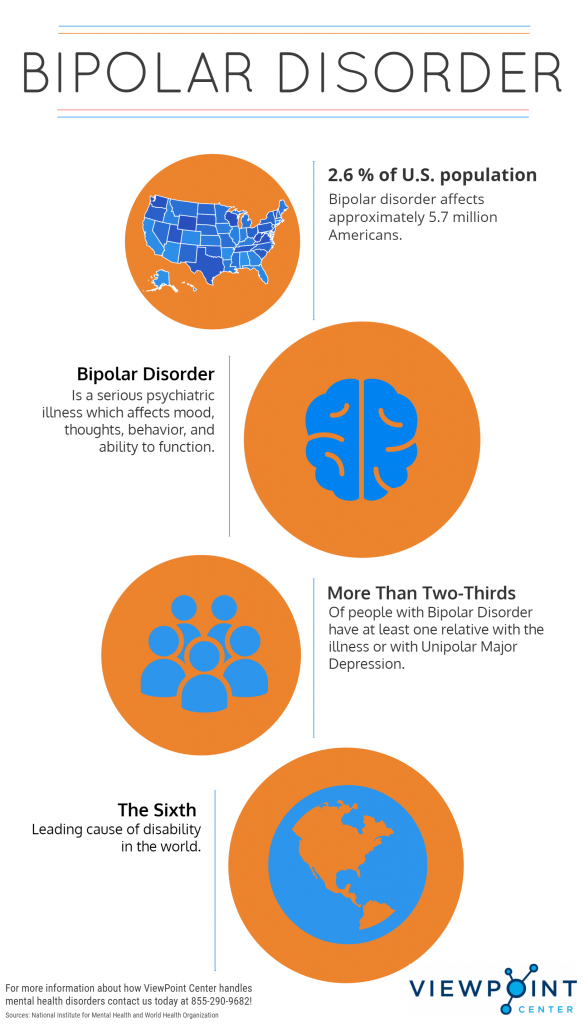

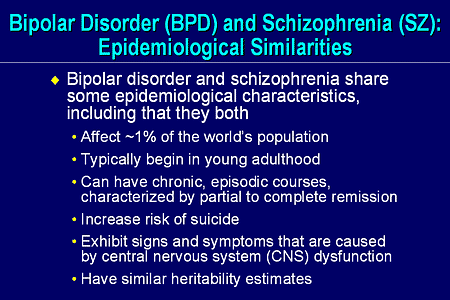

Emotional disturbances are highly prevalent with an early onset in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) [1]. The presence of psychiatric symptoms in MS was underlined and systematically described as early as in 1877 by Charcot. However, it was only in the last two decades that more detailed studies were carried out [2]. Many of these symptoms are described and are not necessarily related to the psychological impact of such a chronic and disabling disease. Depression is the most common psychiatric manifestation with a prevalence of 22–54% [3]. Other manifestations are anxiety, euphoria, and psychosis [4]. Bipolar disorder and MS coexistence is not common but well proven. A few cases have been already reported [5–8]. The link between these two disorders is not fully determined. Herein, we present three cases of MS and bipolar disorder and we discuss the possible etiological hypothesis and treatment options.

Other manifestations are anxiety, euphoria, and psychosis [4]. Bipolar disorder and MS coexistence is not common but well proven. A few cases have been already reported [5–8]. The link between these two disorders is not fully determined. Herein, we present three cases of MS and bipolar disorder and we discuss the possible etiological hypothesis and treatment options.

2.1. Case 1

A 39-year-old man, with no family medical history, was followed up since 1992 at the age of 20 for bipolar disorder with mainly manic fits. He was treated with a mood stabilizer (lithium carbonate). In October 2003, he presented a decrease in visual acuity that resolved spontaneously after 15 days. In September 2004, he reported paresthesia and weakness of the left side of the body associated with urinary incontinence. The symptoms regressed after a five-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g per day). Neurological examination revealed a left hemiparesis and left pyramidal syndrome. Cerebrospinal MRI showed multiple T2-weighted hyperintense lesions in periventricular white matter and in corpus callosum, as well as the cervical spine at C2 and C3 (). Radiological Barkhof criteria for MS were fulfilled. Autoantibody (ANA, anti-DNA, anti-SSA, anti-SSB, and anti-SM) and serology (syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV) tests were negative. Visual evoked potentials showed increased latencies. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, and interferon beta-1A treatment had been initiated since December 2004. During the seven years of follow-up, the patient presented two neurological fits in December 2005 and February 2007. His last EDSS score was 1. He repeatedly discontinued his mood stabilizer treatment and had concomitant manic fits.

Radiological Barkhof criteria for MS were fulfilled. Autoantibody (ANA, anti-DNA, anti-SSA, anti-SSB, and anti-SM) and serology (syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV) tests were negative. Visual evoked potentials showed increased latencies. Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with relapsing-remitting MS, and interferon beta-1A treatment had been initiated since December 2004. During the seven years of follow-up, the patient presented two neurological fits in December 2005 and February 2007. His last EDSS score was 1. He repeatedly discontinued his mood stabilizer treatment and had concomitant manic fits.

Open in a separate window

Axial cerebral T2-weighted image showing multiple lesions in periventricular and subcortical white matter. Dawson's finger (arrow) is a characteristic finding in multiple sclerosis.

2.2. Case 2

A 38-year-old woman, with a family history of bipolar disorder in a maternal uncle, has been followed up since the age of 20 for manic depressive psychosis with mainly manic episodes. A mood stabilizer treatment was prescribed (lithium carbonate). She consulted in 2005 about an episode of weakness of both lower limbs. She reported a similar episode in 2004 that resolved spontaneously after a few days. Neurological examination revealed a quadripyramidal syndrome with right kinetic cerebellar syndrome. Cerebrospinal MRI displayed multiple ovoid and confluent T2 hyperintense lesions in periventricular and semioval white matter and a cervical lesion at the level of C6. No gadolinium-enhanced lesions were identified. Serological tests for syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV, inflammatory tests, and anti-nuclear antibodies were negative. The diagnosis of clinically definite MS was made. On follow-up, she presented one motor fit per year and was treated with high doses of methylprednisolone in each episode. The last fit was in June 2010. She consulted about an episode of weakness of both lower limbs. A three-day course of high doses of intravenous methylprednisolone was prescribed.

A mood stabilizer treatment was prescribed (lithium carbonate). She consulted in 2005 about an episode of weakness of both lower limbs. She reported a similar episode in 2004 that resolved spontaneously after a few days. Neurological examination revealed a quadripyramidal syndrome with right kinetic cerebellar syndrome. Cerebrospinal MRI displayed multiple ovoid and confluent T2 hyperintense lesions in periventricular and semioval white matter and a cervical lesion at the level of C6. No gadolinium-enhanced lesions were identified. Serological tests for syphilis, hepatitis B and C, and HIV, inflammatory tests, and anti-nuclear antibodies were negative. The diagnosis of clinically definite MS was made. On follow-up, she presented one motor fit per year and was treated with high doses of methylprednisolone in each episode. The last fit was in June 2010. She consulted about an episode of weakness of both lower limbs. A three-day course of high doses of intravenous methylprednisolone was prescribed. Two days later, she presented a manic fit requiring hospitalization in a psychiatric department. Cerebrospinal MRI showed no new lesions. The patient was treated with atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine) associated with lithium carbonate with resolution of the manic episode.

Two days later, she presented a manic fit requiring hospitalization in a psychiatric department. Cerebrospinal MRI showed no new lesions. The patient was treated with atypical antipsychotics (olanzapine) associated with lithium carbonate with resolution of the manic episode.

2.3. Case 3

A 23-year-old woman, with a family history of bipolar disorder in a sister, had no past personal history. In April 2005, she presented clumsiness in the right side of her body that completely regressed after two months. In February 2007, she reported weakness in her left hemibody with blurred vision, completely regressed after one month. In November 2008, the patient was hospitalized for a motor deficiency in the right hemibody associated with diplopia and bladder dysfunction. Neurological examination showed right hemiparesis with quadripyramidal syndrome and static and kinetic cerebellar syndrome. Cerebral MRI revealed multiple T2 hyperintense lesions in periventricular and subcortical “white matter”, mainly in frontal and temporal lobes, right cerebellar peduncle, and corpus callosum and two cervical lesions at the level of C2 and C3. Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) detected the presence of oligoclonal bands. The diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS was confirmed according to McDonald criteria. The patient received a 5-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g per day). Six months later, the patient developed psychiatric symptoms with irritability, frequent crying, social withdrawal, and insomnia. She has not consulted and received no treatment. A few months later, the clinical picture changed spontaneously and the patient was hospitalized for a manic episode with euphoria, grandiosity, hyperactivity, and reduced need to sleep. Neurological examination was normal. Cerebral MRI showed a right orbitofrontal active lesion with gadolinium enhancement (). She was treated with an antipsychotic (haloperidol 15 mg t.i.d) in association with a mood stabilizer (sodium valproate 600 mg t.i.d) with resolution of the manic episode. An interferon beta-1A treatment was started in April 2011 with good tolerance.

Analysis of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) detected the presence of oligoclonal bands. The diagnosis of relapsing-remitting MS was confirmed according to McDonald criteria. The patient received a 5-day course of intravenous methylprednisolone (1 g per day). Six months later, the patient developed psychiatric symptoms with irritability, frequent crying, social withdrawal, and insomnia. She has not consulted and received no treatment. A few months later, the clinical picture changed spontaneously and the patient was hospitalized for a manic episode with euphoria, grandiosity, hyperactivity, and reduced need to sleep. Neurological examination was normal. Cerebral MRI showed a right orbitofrontal active lesion with gadolinium enhancement (). She was treated with an antipsychotic (haloperidol 15 mg t.i.d) in association with a mood stabilizer (sodium valproate 600 mg t.i.d) with resolution of the manic episode. An interferon beta-1A treatment was started in April 2011 with good tolerance.

Open in a separate window

Axial cerebral T1-weighted image revealing a right orbitofrontal active lesion with gadolinium enhancement (arrow).

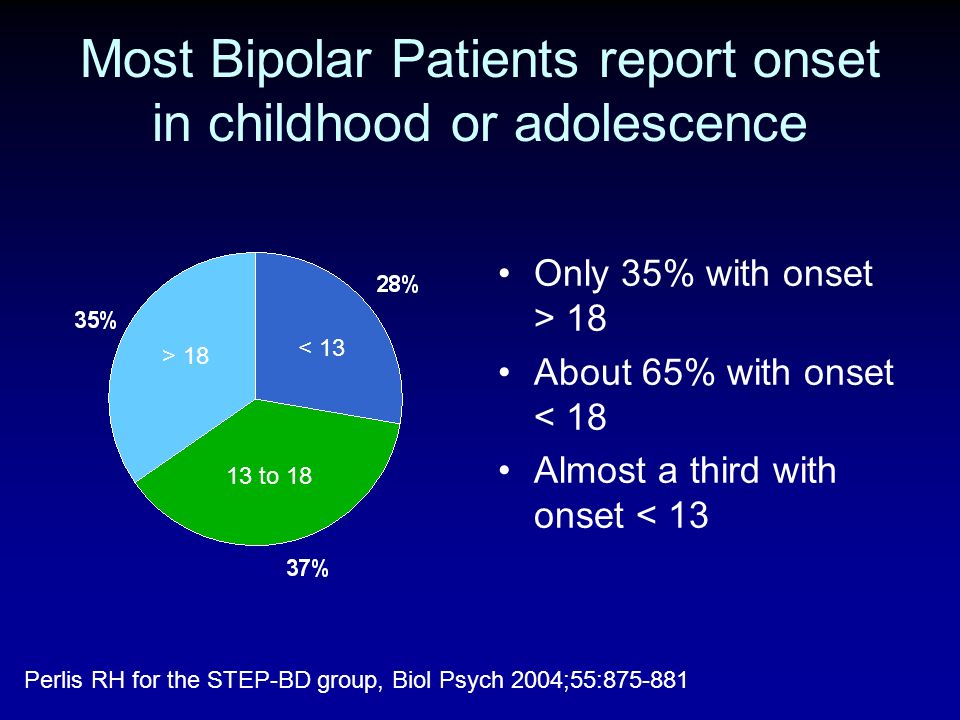

The first case report describes a man with a long term history of bipolar disorder who developed MS. In this case, the most likely hypothesis advanced to explain this comorbidity would be a casual association. In fact, MS is a relatively rare disease with an estimated prevalence in Tunisia of 20.1 per 100,000 inhabitants [9], yet bipolar disorder affects 1% of the population [10]. As patients with bipolar disorder have at least the same risk of developing MS as subjects not suffering from bipolar disorder, it is possible that both conditions coexist with no direct link between them. However, Joffe et al. have shown that manic depressive psychosis appears to be significantly more common in MS patients than in the general population, prompting the search for alternative hypotheses [11]. Etiopathogenic bases explaining this association are not yet understood. One hypothesis is that mood disorders could be an inaugural manifestation in MS [12] or may be the presenting symptom of MS years before the development of neurological signs as shown in the first two patients [13]. In fact, Lyoo et al. performed brain MRI on 2783 patients who were referred as part of their psychiatric evaluation. Their findings indicated that 0.83% of the patients had T2-weighted white matter hyperintensities consistent with MS, which was almost 15 times the reported prevalence of MS in the general population in the United States [14]. These results suggest the possibility of pure “psychiatric fits” in MS. This hypothesis has been reported by several authors [15, 16]. However, a study of 7301 autopsies of patients followed in psychiatry has led to the anatomopathological confirmation of MS in 14 patients, none of whom has a pure psychiatric form without any associated neurological manifestations [17].

In fact, Lyoo et al. performed brain MRI on 2783 patients who were referred as part of their psychiatric evaluation. Their findings indicated that 0.83% of the patients had T2-weighted white matter hyperintensities consistent with MS, which was almost 15 times the reported prevalence of MS in the general population in the United States [14]. These results suggest the possibility of pure “psychiatric fits” in MS. This hypothesis has been reported by several authors [15, 16]. However, a study of 7301 autopsies of patients followed in psychiatry has led to the anatomopathological confirmation of MS in 14 patients, none of whom has a pure psychiatric form without any associated neurological manifestations [17].

The second case report illustrates the occurrence of a manic episode following high doses of methylprednisolone. Corticosteroids have long been implicated in the precipitation of the onset of certain psychiatric symptoms. The most common adverse effects of short-term corticosteroid therapy are mood disorder, euphoria, and hypomania. Conversely, long-term therapy tends to induce depressive symptoms [18]. Dosage is directly related to the incidence of adverse effects but is not related to the timing, severity, or duration of these effects [19]. Among MS patients treated with corticosteroids or ACTH, two systematic studies reported that 40% became depressed, 31% hypomanic, and 11% developed a mixed state and 16% a psychotic state [20]. Interestingly, these symptoms do not occur with every drug exposure and appear more frequently in case of a discontinuous treatment [21].

Conversely, long-term therapy tends to induce depressive symptoms [18]. Dosage is directly related to the incidence of adverse effects but is not related to the timing, severity, or duration of these effects [19]. Among MS patients treated with corticosteroids or ACTH, two systematic studies reported that 40% became depressed, 31% hypomanic, and 11% developed a mixed state and 16% a psychotic state [20]. Interestingly, these symptoms do not occur with every drug exposure and appear more frequently in case of a discontinuous treatment [21].

Although research of the etiopathogenesis of the association between MS and bipolar disorder is still limited, a common genetic susceptibility to both diseases was discussed. In a series of 56 patients, Schiffer et al. noted a higher frequency of the HLA-DR2 and -DR3 haplotype and a decrease in the frequency of HLA-DR1 and -DR4 in patients with both MS and bipolar disorder with a family history of affective disorders [5]. More recently, Bozikas et al. investigated this possible association based on the study of the HLA system in family members of a patient with both MS and bipolar disorder and family history of bipolar disorder. This study showed that HLA-DR2 haplotype appears to be a susceptible locus for bipolar disorder. These studies suggest that genes near the HLA region on chromosome 6 could be involved in the multifactorial pathogenesis underlying the clinical comorbidity of the two disorders [7]. Our patient in the third case has a family history of bipolar disorder and could therefore have a genetic susceptibility for this disorder. The hypothesis of a common vulnerability between MS and bipolar disorder could be advanced.

investigated this possible association based on the study of the HLA system in family members of a patient with both MS and bipolar disorder and family history of bipolar disorder. This study showed that HLA-DR2 haplotype appears to be a susceptible locus for bipolar disorder. These studies suggest that genes near the HLA region on chromosome 6 could be involved in the multifactorial pathogenesis underlying the clinical comorbidity of the two disorders [7]. Our patient in the third case has a family history of bipolar disorder and could therefore have a genetic susceptibility for this disorder. The hypothesis of a common vulnerability between MS and bipolar disorder could be advanced.

The manic symptoms may also be related to white matter lesions location [22]. Indeed, the orbitofrontal cortex is the main structure involved in regulating social behavior. Its disconnection from subcortical structures due to white matter damage in MS may explain, at least in part, the symptoms in the manic syndrome (exalted mood and disinhibition). This was noted in the third case as a new active lesion was found in the orbitofrontal cortex concomitant with the manic episode.

This was noted in the third case as a new active lesion was found in the orbitofrontal cortex concomitant with the manic episode.

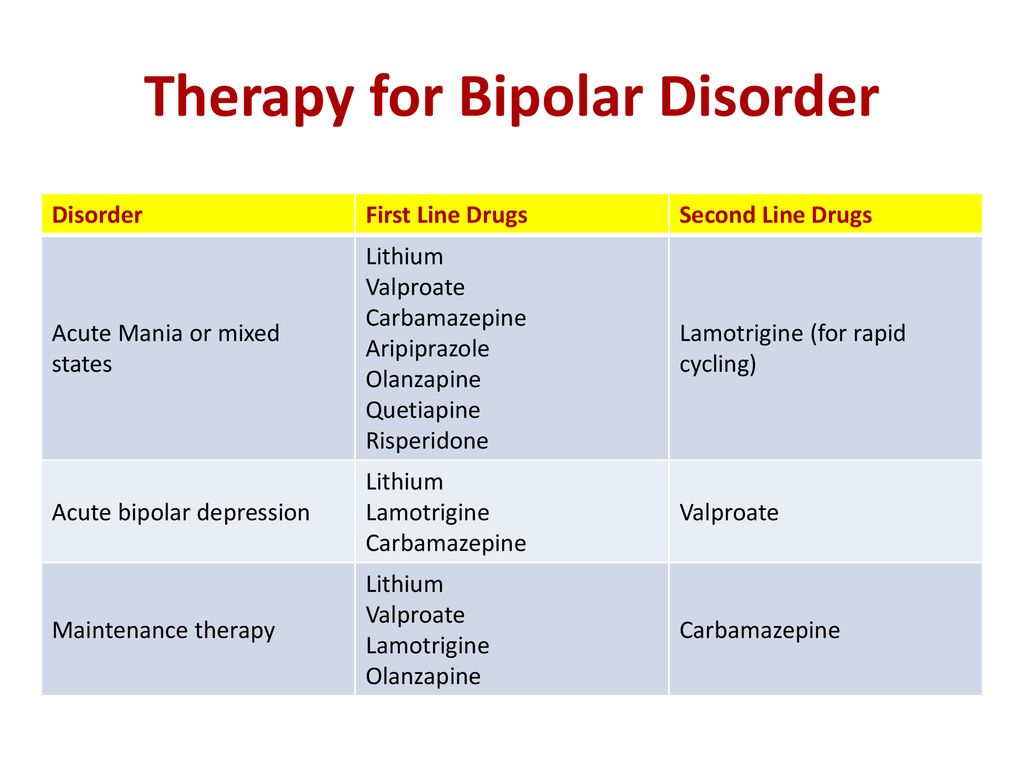

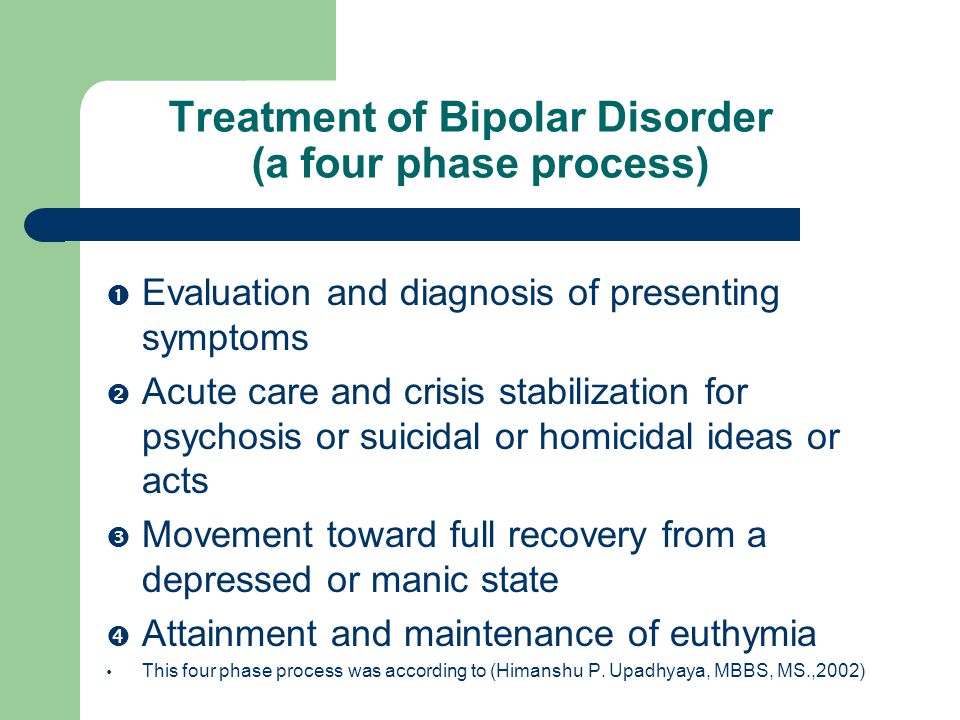

Bipolar disorder in MS patients is usually treated in the same way as in the general population. A treatment with mood stabilizers (sodium valproate, carbamazepine, and lithium) associated with atypical antipsychotics is generally effective on manic fits. This was the case in our three patients. The use of lithium must be with caution in patients with sphincter disorders since they tend to reduce their fluid intake and may thus have high serum levels of lithium approaching toxic doses [23]. Remission of psychiatric symptoms was noted using high doses of methylprednisolone even when fits were purely psychiatric [10]. This positive effect of corticosteroids against psychological fits supports the hypothesis of an organic cause for MS and bipolar comorbidity. It should be emphasized that the risk of exacerbation of psychiatric disorders using corticosteroids, which are not constant and occur more frequently in case of a discontinuous treatment, should not delay their use. In fact, patients manifesting psychiatric symptoms could still be treated with mood stabilizers, neuroleptics, or antidepressants with simultaneous steroid taper, as seen in Case 2. Thus, the main lesson for clinicians is that they should be aware of the possibility of steroid psychosis and be ready to treat it.

In fact, patients manifesting psychiatric symptoms could still be treated with mood stabilizers, neuroleptics, or antidepressants with simultaneous steroid taper, as seen in Case 2. Thus, the main lesson for clinicians is that they should be aware of the possibility of steroid psychosis and be ready to treat it.

Interferon beta (IFN-β) treatment has been proposed to our patients to prevent relapses with good tolerance. Although initial studies have reported cases of suicide and depression in patients treated with IFN-β, none of the randomized controlled trials using standardized and validated measures of depression showed a significantly increased risk of depression in patients treated with IFN-β [24]. Other studies did not show a worsening of mood disorders in MS patients treated with IFN-β for a long period [25]. We can therefore conclude that the presence of major depression is not an absolute contraindication to treatment with IFN-β. Neurologists should, however, always be alert to the possible development of depression in all patients with MS, whether they are on disease-modifying treatment or not.

Neurologists should, however, always be alert to the possible development of depression in all patients with MS, whether they are on disease-modifying treatment or not.

These three case reports highlighted the possible association between MS and bipolar disorder, an association that is still not well studied. We conclude that interferon beta treatments are well tolerated while high dose corticosteroids may induce manic fits. MS and bipolar association may be due to local MS-related brain damage or due to common genetic vulnerability. More studies focusing on specific response to treatment and genetic susceptibility are mandatory.

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

1. Minden SL. Mood disorders in multiple sclerosis: diagnosis and treatment. Journal of Neurovirology. 2000;6(2):S160–S167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Iacovides A, Andreoulakis E. Bipolar disorder and resembling special psychopathological manifestations in multiple sclerosis: a review. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2011;24(4):336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2011;24(4):336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Lebrun C, Cohen M. Depression in multiple sclerosis. Revue neurologique. 2009;165:S156–S162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Ghaffar O, Feinstein A. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: a review of recent developments. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20(3):278–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Schiffer RB, Wineman NM, Weitkamp LR. Association between bipolar affective disorder and multiple sclerosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1986;143(1):94–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Casanova MF, Kruesi M, Mannheim G. Multiple sclerosis and bipolar disorder: a case report with autopsy findings. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1996;8(2):206–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Bozikas VP, Anagnostouli MC, Petrikis P, et al. Familial bipolar disorder and multiple sclerosis: a three-generation HLA family study. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2003;27(5):835–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2003;27(5):835–839. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. De Cerqueira AC, Nardi AE, Souza-Lima F, Godoy-Barreiros JM. Bipolar disorder and multiple sclerosis: comorbidity and risk factors. Revista Brasileira de Psiquiatria. 2010;32(4):454–456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Ammar N, Gouider-Khouja N, Hentati F. A comparative study of clinical and paramedical aspects of multiple sclerosis in Tunisia. Revue Neurologique. 2006;162(6):729–733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Rouillon F. Bipolar disorders: epidemiology. Annales Medico-Psychologiques. 2009;167(10):793–795. [Google Scholar]

11. Joffe RT, Lippert GP, Gray TA, Sawa G, Horvath Z. Mood disorder and multiple sclerosis. Archives of Neurology. 1987;44(4):376–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Blanc F, Berna F, Fleury M, et al. Inaugural psychotic events in multiple sclerosis? Revue Neurologique. 2010;166(1):39–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Jongen PJ. Psychiatric onset of multiple sclerosis. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2006;245(2):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 2006;245(2):59–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Lyoo K, Seol HY, Byun HS, Renshaw PF. Unsuspected multiple sclerosis in patients with psychiatric disorders: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 1996;8(1):54–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Skegg K, Corwin PA, Skegg DC. How often is multiple sclerosis mistaken for a psychiatric disorder? Psychological Medicine. 1988;18(3):733–736. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Asghar-Ali AA, Taber KH, Hurley RA, Hayman LA. Pure neuropsychiatric presentation of multiple sclerosis. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161(2):226–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Johannsen LG, Stenager E, Jensen K. Clinically unexpected multiple sclerosis in patients with mental disorders: a series of 7301 psychiatric autopsies. Acta Neurologica Belgica. 1996;96(1):62–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Bolanos SH, Khan DA, Hanczyc M, Bauer MS, Dhanani N, Brown ES. Assessment of mood states in patients receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy and in controls with patient-rated and clinician-rated scales. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2004;92(5):500–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Assessment of mood states in patients receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy and in controls with patient-rated and clinician-rated scales. Annals of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. 2004;92(5):500–505. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Warrington TP, Bostwick JM. Psychiatric adverse effects of corticosteroids. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2006;81(10):1361–1367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Ybarra MI, Moreira MA, Araújo CR, Lana-Peixoto MA, Teixeira AL. Bipolar disorder and multiple sclerosis. Arquivos de Neuro-Psiquiatria. 2007;65(4):1177–1180. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Minden SL, Orav J, Schildkraut JJ. Hypomanic reactions to ACTH and prednisone treatment for multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 1988;38(10):1631–1634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Hutchinson M, Stack J, Buckley P. Bipolar affective disorder prior to the onset of multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 1993;88(6):388–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, Koutsis G, Papadimitriou GN. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. International Review of Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paparrigopoulos T, Ferentinos P, Kouzoupis A, Koutsis G, Papadimitriou GN. The neuropsychiatry of multiple sclerosis: focus on disorders of mood, affect and behaviour. International Review of Psychiatry. 2010;22(1):14–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Wilken JA, Sullivan C. Recognizing and treating common psychiatric disorders in multiple sclerosis. Neurologist. 2007;13(6):343–354. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Porcel J, Río J, Sánchez-Betancourt A, et al. Long-term emotional state of multiple sclerosis patients treated with interferon beta. Multiple Sclerosis. 2006;12(6):802–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bipolar disorder in MS - switching between overly joyful and extremely sad

Background

About half of people with MS experience depression at some time. Depression can be the result of living with MS but can also be a symptom caused directly by MS if there is a lesion in an area of the brain involved in mood.

Bipolar disorder, previously known as manic depression, is characterised by alternating times when the person feels depressed and periods when they feel overly joyful (manic). These are different from the normal ups and downs that everyone goes through from time to time.

These are different from the normal ups and downs that everyone goes through from time to time.

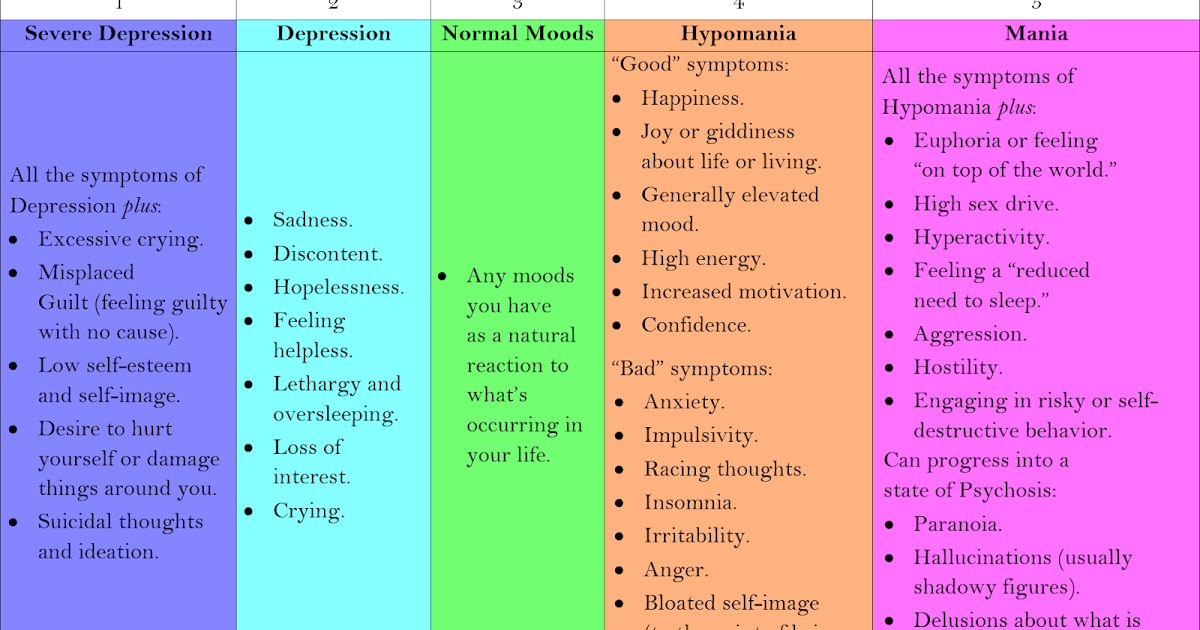

An overly joyful or overexcited state is called a manic episode, and an extremely sad or hopeless state is called a depressive episode. Extreme changes in energy, activity, sleep and behaviour go along with these changes in mood. A person may be having an episode of bipolar disorder if they have a number of manic or depressive symptoms for most of the day, nearly every day, for at least one or two weeks. Sometimes symptoms are so severe that the person cannot function normally at work, school or home.

How this study was carried out

This study looked at the risk of mood disorders in 201 people with MS attending a clinic in Italy alongside four times as many age and sex-matched controls without MS.

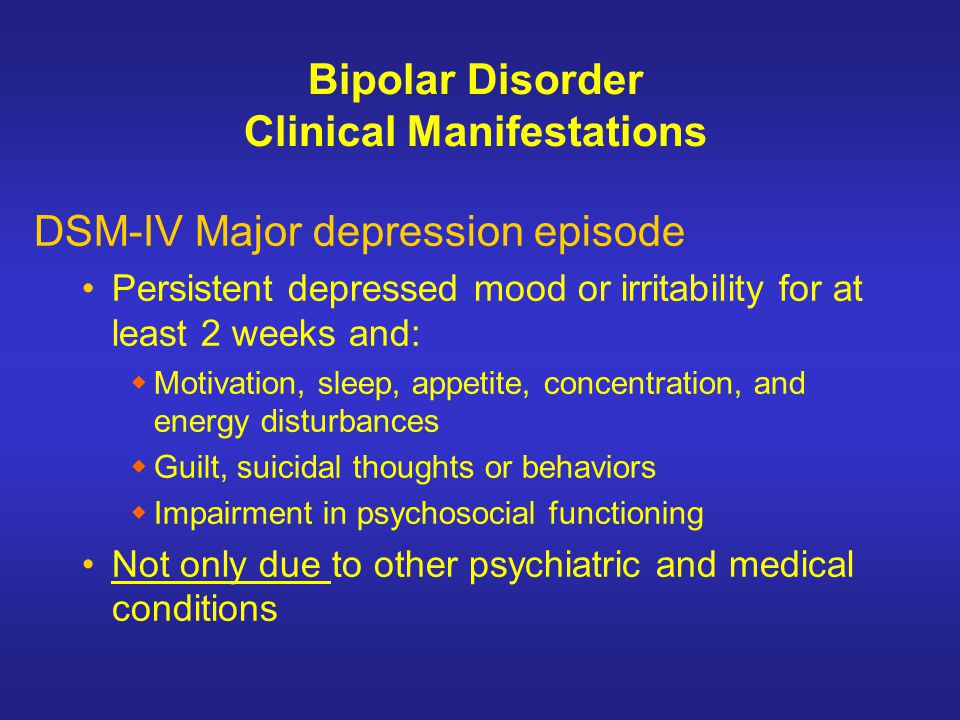

The participants were assessed for mood disorders using DSM-IV, a standard way of diagnosing and classifying mental health conditions, and interview-based assessment tools called ANTAS, SCID and MDQ. Each group was assessed for the likelihood of a range of mood disorders over their whole lifetime. The conditions assessed were:

Each group was assessed for the likelihood of a range of mood disorders over their whole lifetime. The conditions assessed were:

- major depressive disorder

- bipolar disorder type 1 and 2 (see below)

- cyclothymic disorder (see below)

- mood disorder due to general medical condition (depressive symptoms that are a direct physiological result of the medical condition)

- substance induced mood disorder

- dysthymic disorder.

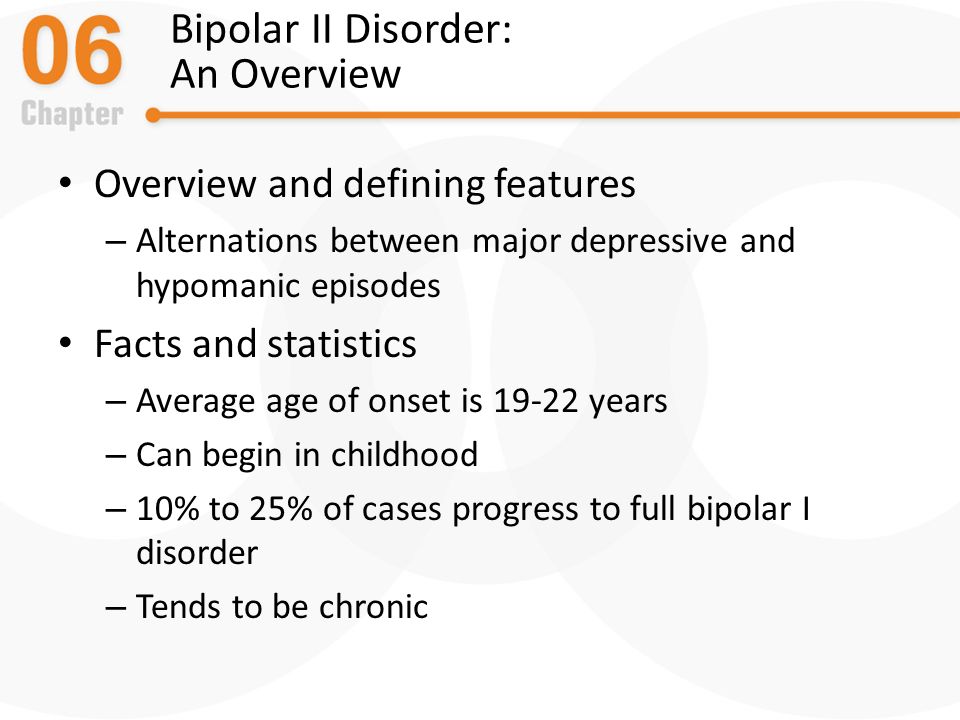

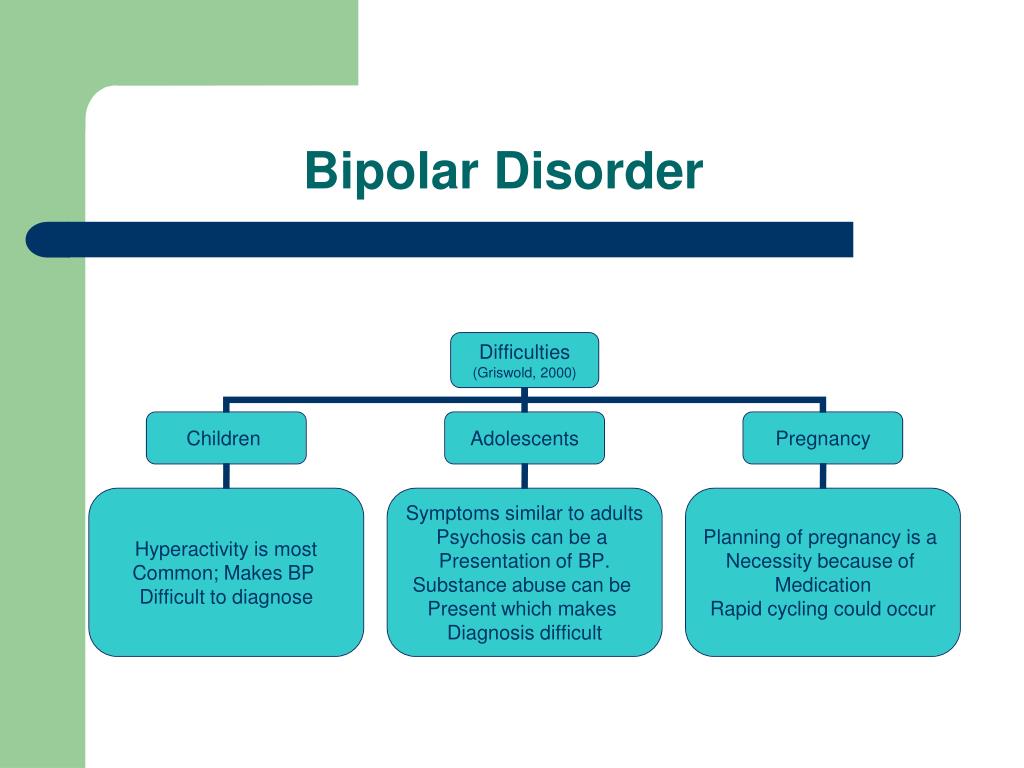

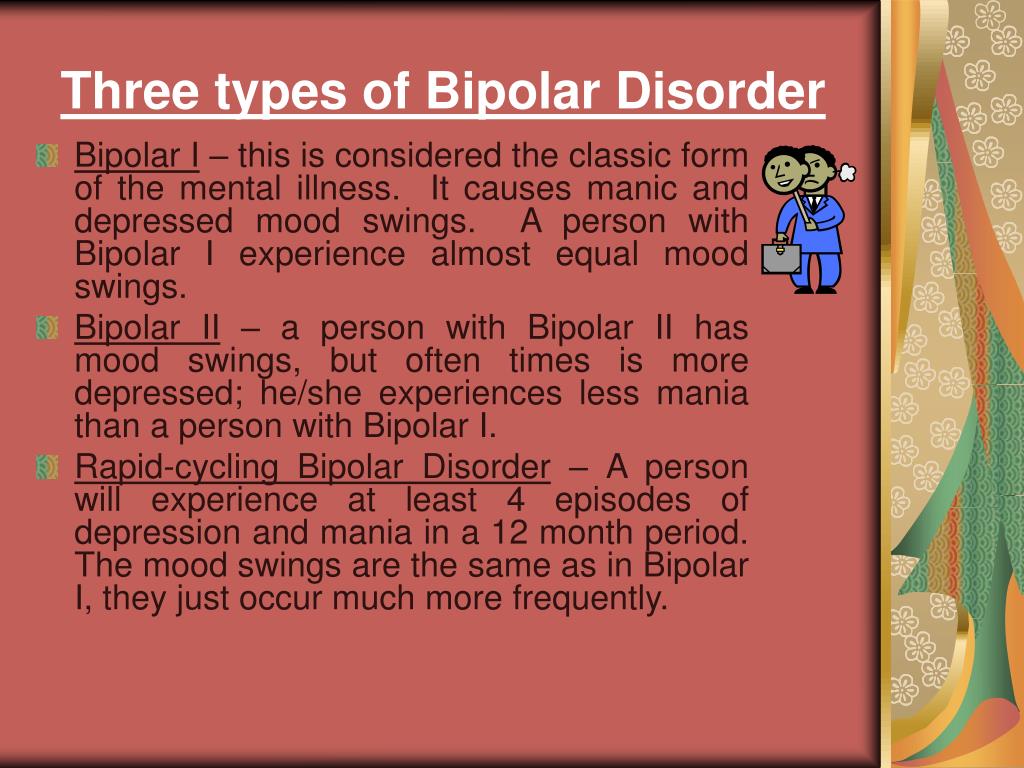

There are three types of bipolar disorder:

- Bipolar type 1 disorder, in which the primary symptom presentation is manic, or rapid (daily) cycling episodes of mania and depression

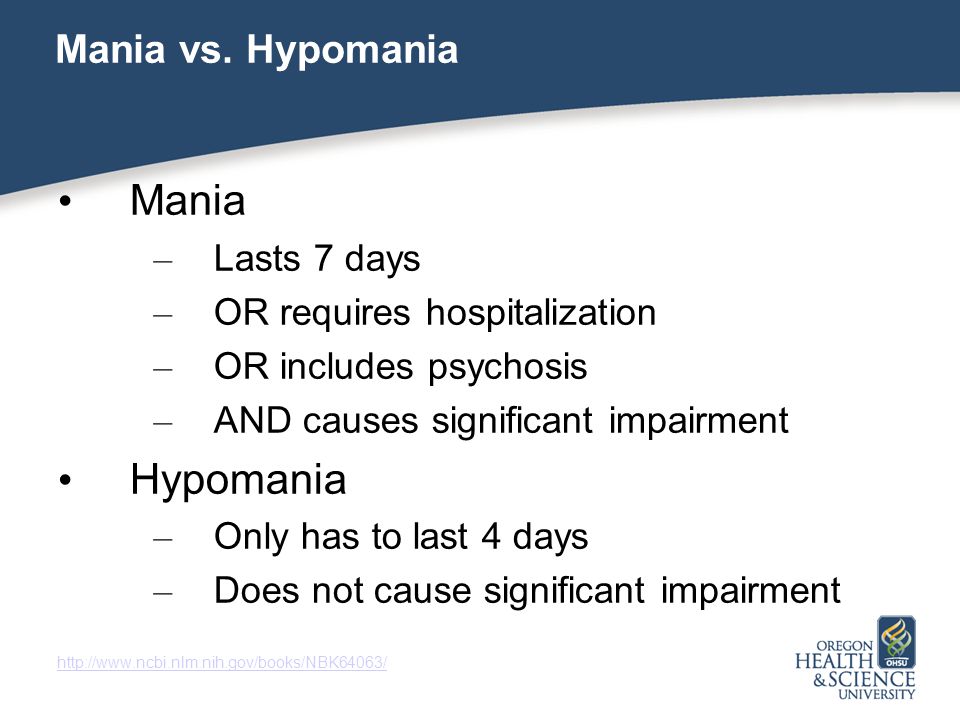

- Bipolar type 2 disorder, in which the primary symptom presentation is recurrent depression accompanied by hypomanic episodes (a milder state of mania in which the symptoms are not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or need for hospitalisation, but are sufficient to be observable by others)

- Cyclothymic disorder, a chronic state of cycling between hypomanic and depressive episodes that do not reach the diagnostic standard for bipolar disorder

Detailed diagnostic criteria for all the conditions can be found using the links for each above.

What was found

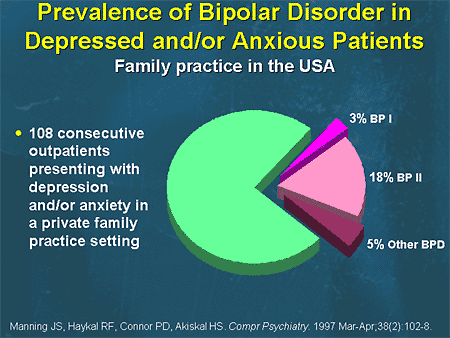

Almost half of people with MS (47%) in the study had experienced a mood disorder which was more than in the control group. The conditions experienced most often by people with MS were major depressive disorders, bipolar disorders type 1 and 2, cyclothymic disorder, mood disorder due to general medical condition and substance induced mood disorders. Bipolar disorders were the most strongly associated with having MS.

What does it mean?

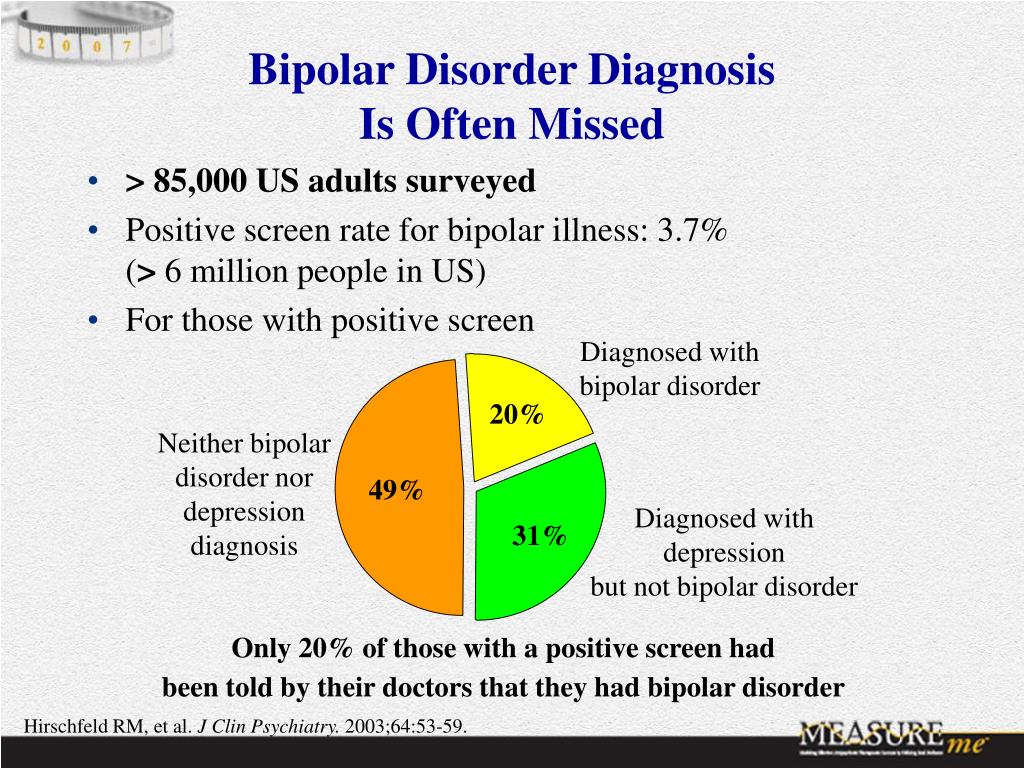

The authors comment that this is the first case controlled study to show that bipolar disorder is associated with MS. They believe that bipolar disorder is often unrecognised and so under-diagnosed. They suggest that health professionals should take care to assess people with MS for bipolar disorder when prescribing antidepressants. However, they acknowledge that bipolar disorder is difficult to diagnose as people are more likely to report symptoms of depression and to visit their doctor when depressed. Manic symptoms are often seen by the person experiencing them as times of well-being, or periods between episodes of depression, and not viewed as unusual or unwelcome.

Carta MG, Moro MF, Lorefice L, et al.

The risk of bipolar disorders in multiple sclerosis..

J Affect Disord. 2013 Nov 19 [Epub ahead of print]

abstract

Bipolar Disorder | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

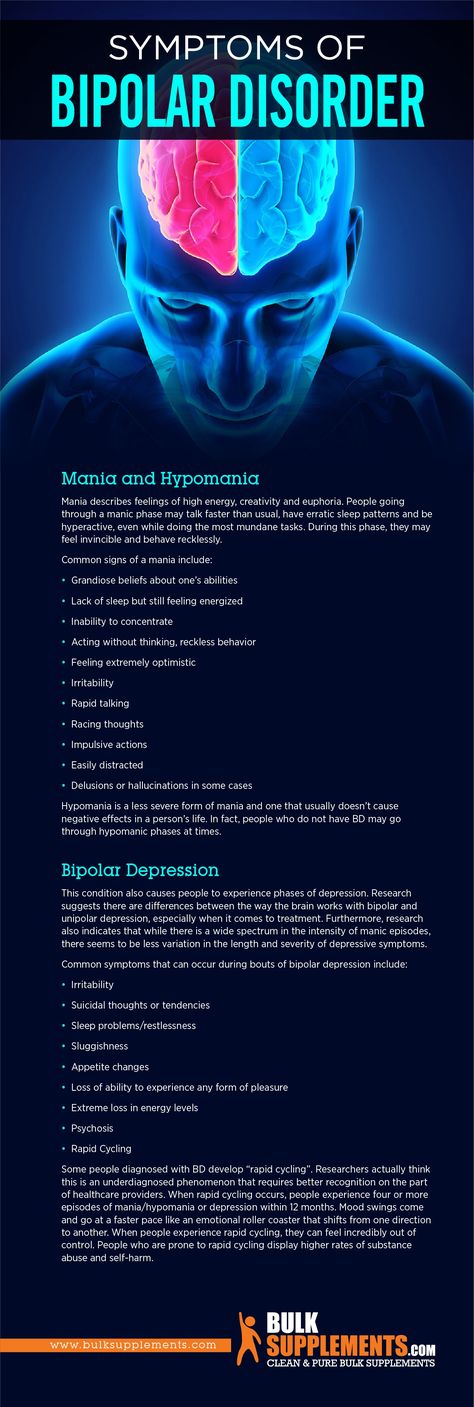

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Episodes of mood swings may occur infrequently or several times a year.

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Symptoms

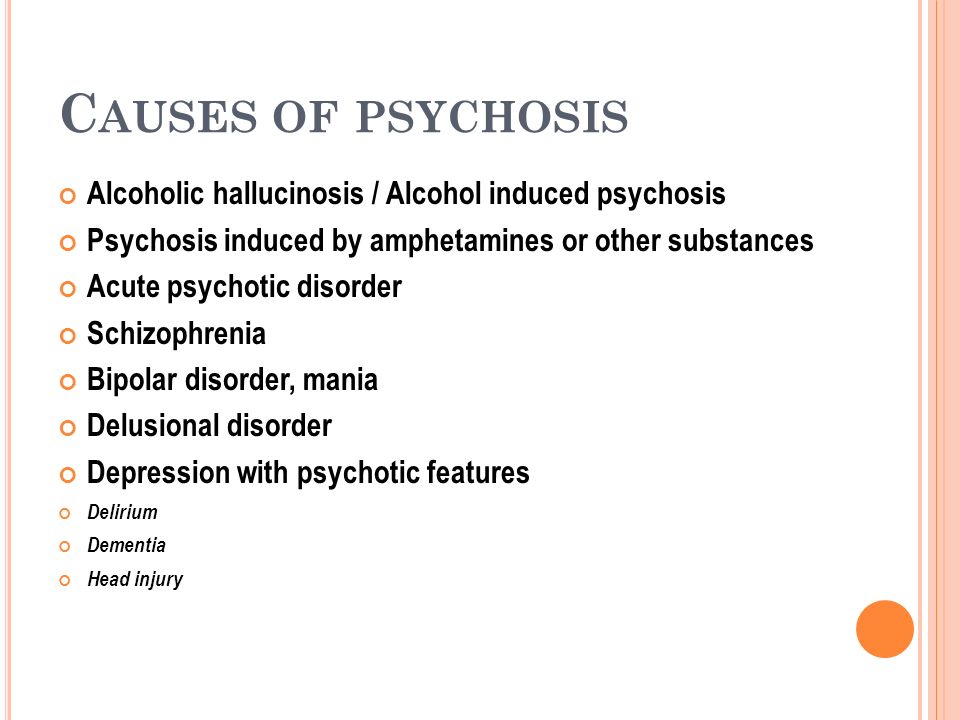

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. They may include mania, hypomania, and depression. The symptoms can lead to unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, leading to significant stress and difficulty in life.

- Bipolar disorder I. You have had at least one manic episode, which may be preceded or accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania can cause a break with reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar disorder II. You have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but never had a manic episode.

- Cyclothymic disorder. You have had at least two years - or one year in children and adolescents - many periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders caused by certain drugs or alcohol, or due to health conditions such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis, or stroke.

Bipolar II is not a milder form of Bipolar I but is a separate diagnosis. Although bipolar I manic episodes can be severe and dangerous, people with bipolar II can be depressed for longer periods of time, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in adolescence or early twenties. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time.

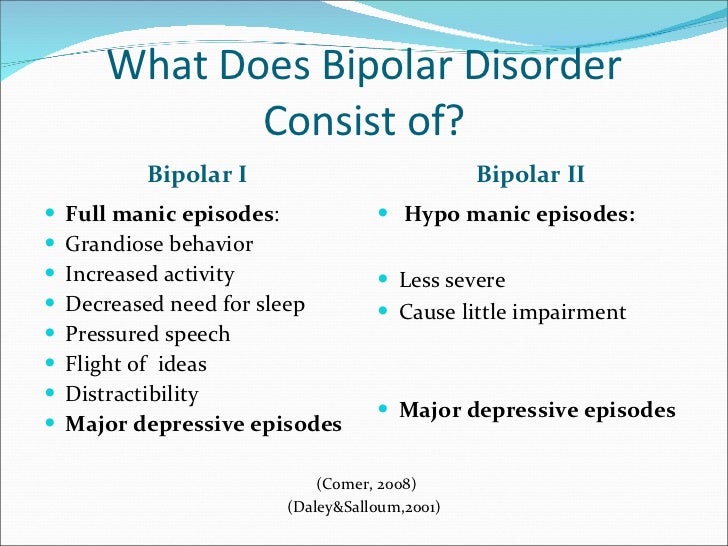

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes, but they share the same symptoms. Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic episode and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally optimistic or nervous

- Increased activity, energy or excitement

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making - for example, in speculation, in sexual encounters or in irrational investments

Major depressive episode

Major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in daily activities such as work, school, social activities, or relationships. Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or tearful (in children and adolescents, depressed mood may manifest as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling of displeasure in all (or nearly all) activities

- Significant weight loss with no diet, weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected may be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either anxiety or slow behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder may include other signs such as anxiety disorder, melancholia, psychosis, or others. The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic markers such as mixed or fast cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or with the change of seasons.

The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic markers such as mixed or fast cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or with the change of seasons.

When to see a doctor

Despite extreme moods, people with bipolar disorder often do not realize how much their emotional instability disrupts their lives and the lives of their loved ones and do not receive the necessary treatment.

And if you are like people with bipolar disorder, you can enjoy feelings of euphoria and be more productive. However, this euphoria is always accompanied by an emotional disaster that can leave you depressed and possibly in financial, legal, or other bad relationships.

If you have symptoms of depression or mania, see your doctor or mental health professional. Bipolar disorder does not improve on its own. Getting mental health treatment with a history of bipolar disorder can help control your symptoms.

Aggression in Bipolar Disorder: From Stigma to Reality - GSD

What is Bipolar Disorder?

"Bipolar disorder is a chronic disorder that causes severe changes in mood at certain times and affects about 1 in 100 people a year," explains Dr. Raffaella Zanardi.

Raffaella Zanardi.

Patients with bipolar disorder experience the following mood swings:

- depressive episodes accompanied by intense sadness, despair, loss of energy and interest in activities that were once enjoyable;

- manic episodes characterized by high spirits, feelings of well-being, euphoria, arousal, and extremely heightened self-esteem.

Typically, people with bipolar disorder have periods of neutral mood called euthymic mood.

During manic episodes, some patients become irritable and most often unable to accept criticism or other people's opinions. This episode may lead patients to engage in verbally aggressive behavior or even physical abuse of objects or people.

Bipolar disorder and aggression

Contrary to what people and the press usually mean by the word "manic", the likelihood that a patient with bipolar disorder will behave aggressively is quite rare. Patients with bipolar disorder are most often harmless.

A variety of scientific reports of variable aggressive behavior may have confused most of us. Dr. Raffaella Zanardi, the first author of the study, continues:

“The results of the research change significantly if we analyze the concept of aggression in terms of its different types:

- violent behavior towards oneself or other people;

- irritability and agitation.

Although irritability and agitation are not truly aggressive behaviors, they contribute to the maintenance of social stigma towards psychiatric patients.”

San Raffaele: Aggression Study

Dr. Zanardi and Prof. Colombo coordinated a research team that followed 151 patients with bipolar disorder for 12 months.

Research suggests that the perception of bipolar patients as aggressive individuals is the result of social stigma rather than clinical reality.

The San Raffaele-Turro study highlights that the number of aggressive episodes is comparable to or less than the total reported cases during previous studies on this topic.