Breathing related sleep disorder dsm 5

Breathing-Related Sleep Disorders | Abnormal Psychology

Learning Objectives

- Describe sleep apnea and other breathing-related sleep disorders

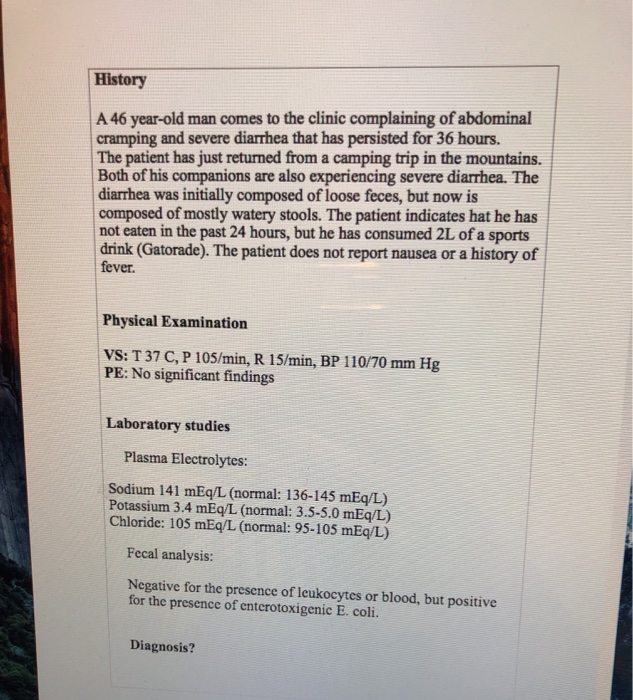

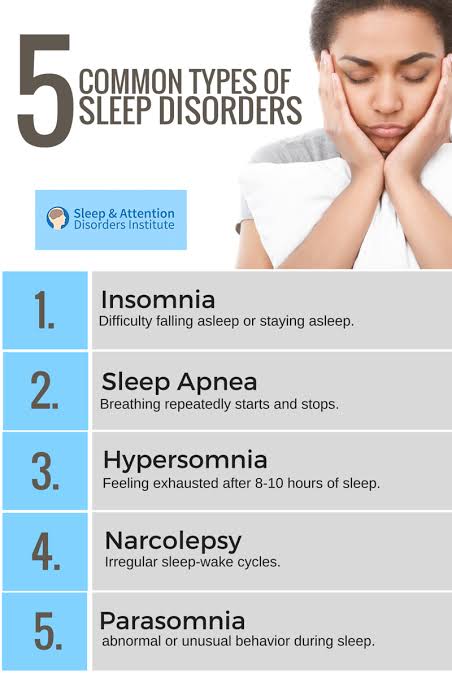

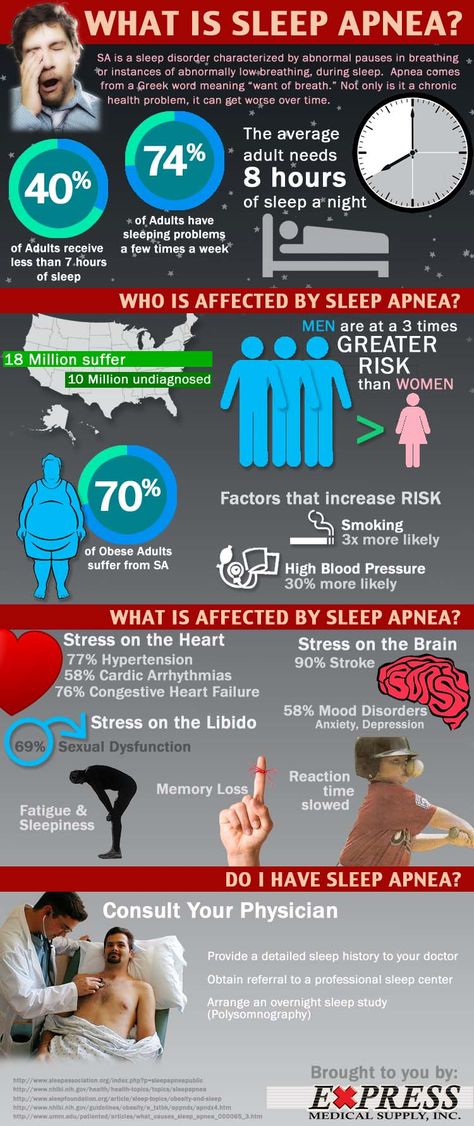

Sleep Apnea

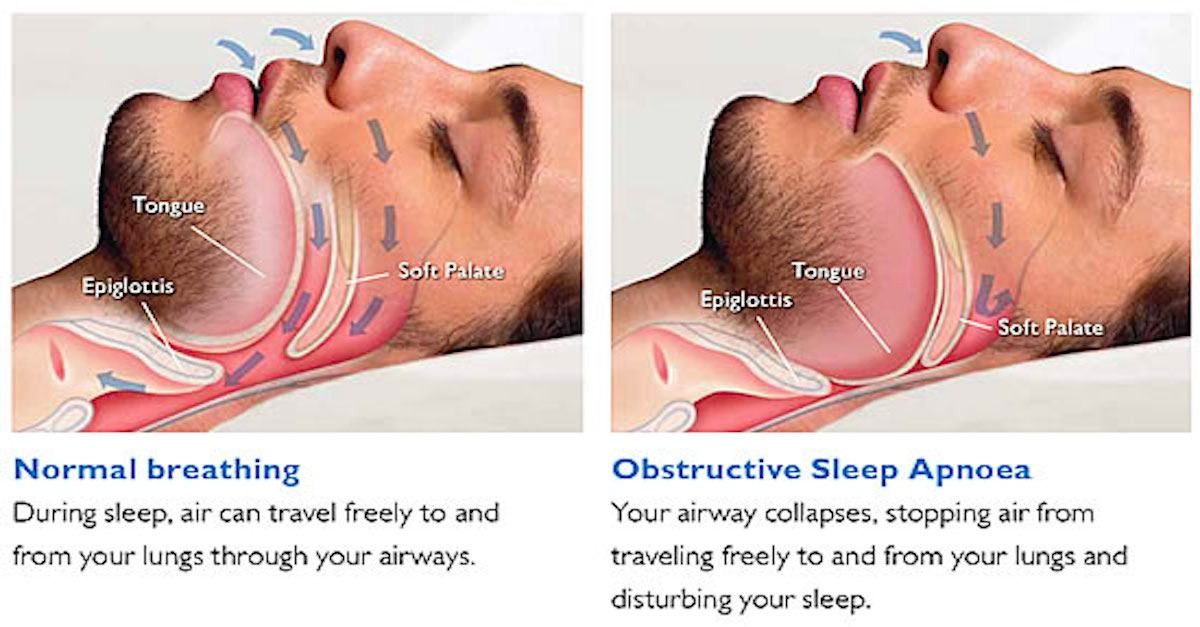

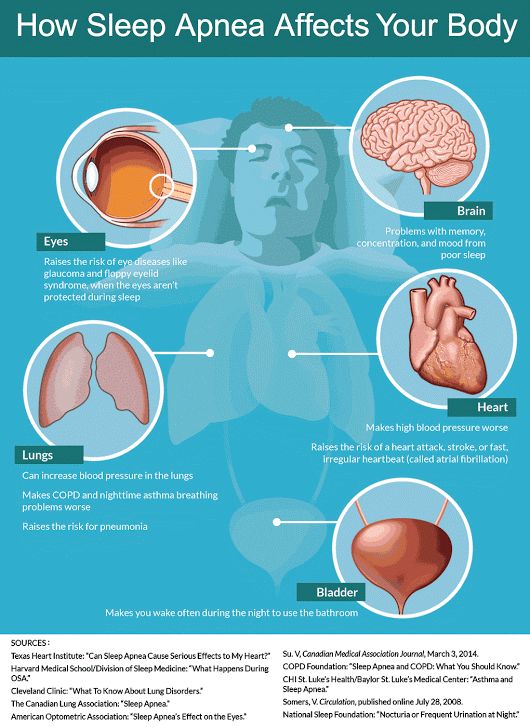

Sleep apnea is defined by episodes during which a sleeper’s breathing stops. Sleep apnea episodes can last 10–20 seconds or longer and often are associated with brief periods of arousal. While individuals suffering from sleep apnea may not be aware of these repeated disruptions in sleep, they do experience increased levels of fatigue. Many individuals diagnosed with sleep apnea first seek treatment because their sleeping partners indicate that they snore loudly and/or stop breathing for extended periods of time while sleeping (Henry & Rosenthal, 2013).

Sleep apnea is much more common in people who are overweight and it may exacerbate cardiovascular disease (Sánchez-de-la-Torre, Campos-Rodriguez, & Barbé, 2012). While sleep apnea is less common in people who are thin, anyone, regardless of their weight, who snores loudly or gasps for air while sleeping, should be checked for sleep apnea.

While people are often unaware of their sleep apnea, they are keenly aware of some of the adverse consequences of insufficient sleep. One person explained that the sleep apnea affected his daily life saying, “I’m in a job where there’s a premium on being mentally alert. I was really sleepy . . . and having trouble concentrating. . . . It was getting to the point where it was kind of scary” (Henry & Rosenthal, 2013, p. 52).

There are two main types of sleep apnea: obstructive sleep apnea, listed as obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea (OSAH) in the DSM-5, and central sleep apnea. Obstructive sleep apnea occurs when an individual’s airway becomes blocked during sleep and air is prevented from entering the lungs. It is diagnosed if a person has at least five obstructive apneas per hour of sleep combined with breathing disturbances such as snoring and daytime sleepiness or at least fifteen obstructive apneas per hour of sleep without other symptoms. The apnea is characterized by at least ten-second disturbances in breathing. In central sleep apnea (CSA), disruption in signals sent from the brain that regulate breathing cause periods of interrupted breathing (White, 2005). Central sleep apnea is less common than obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea (OSAH) and is more commonly associated with illnesses.

The apnea is characterized by at least ten-second disturbances in breathing. In central sleep apnea (CSA), disruption in signals sent from the brain that regulate breathing cause periods of interrupted breathing (White, 2005). Central sleep apnea is less common than obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea (OSAH) and is more commonly associated with illnesses.

Approximately 2%-9% of adults in the United States have obstructive sleep apnea and about 0.9% of adults over the age of 40 are diagnosed with central sleep apnea, but many cases are estimated to be undiagnosed. Both are more common in men than women. There are multiple factors that contribute to being at risk for sleep apnea, including obesity, hormonal imbalances, smoking cigarettes, family history, and the size and positioning of the jaw, throat, and tongue.[1]

Watch It

Watch this video to learn about sleep apnea, including its causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, and pathology.

https://www. youtube.com/watch?v=cjQPGs_tvDY

youtube.com/watch?v=cjQPGs_tvDY

You can view the transcript for “Sleep apnea – causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, pathology” here (opens in new window).

Treatment

One of the most common treatments for sleep apnea involves the use of a special device during sleep. A continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device includes a mask that fits over the sleeper’s nose and mouth, which is connected to a pump that pumps air into the person’s airways, forcing them to remain open, as shown in Figure 1. Some newer continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) masks are smaller and cover only the nose. This treatment option has proven to be effective for people suffering from mild to severe cases of sleep apnea (McDaid et al., 2009). However, alternative treatment options are being explored because consistent compliance by users of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) devices is a problem. EPAP (excitatory positive air pressure) device has shown promise in double-blind trials as one such alternative (Berry, Kryger, & Massie, 2011). Treatment of sleep apnea also involves treading comorbid medical conditions, sometimes through surgery or medications.

Treatment of sleep apnea also involves treading comorbid medical conditions, sometimes through surgery or medications.

Figure 1. (a) A typical CPAP device used in the treatment of sleep apnea is (b) affixed to the head with straps and a mask that covers the nose and mouth.

- Tongue Surgery

- This procedure involves advancing one of the main tongue muscles, the genioglossus muscle, forward, thereby limiting the backward fall of the tongue during sleep. This procedure addresses the same sites of potential obstruction as the hyoid advancement, and numerous studies have shown a high success rate.

- Nasal Surgery

- Both daytime nasal obstruction and nocturnal nasal congestion have been shown as risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing. Therefore, the treatment of nasal obstruction plays an important role in sleep apnea surgery. Three anatomic areas of the nose that may contribute to obstruction are the septum, the turbinates, and the nasal valve.

The most common nasal surgical procedure consists of straightening out the septum and reducing the size of the turbinates, which creates more room in the nose and allows air to pass smoothly and without effort.

The most common nasal surgical procedure consists of straightening out the septum and reducing the size of the turbinates, which creates more room in the nose and allows air to pass smoothly and without effort.

- Both daytime nasal obstruction and nocturnal nasal congestion have been shown as risk factors for sleep-disordered breathing. Therefore, the treatment of nasal obstruction plays an important role in sleep apnea surgery. Three anatomic areas of the nose that may contribute to obstruction are the septum, the turbinates, and the nasal valve.

- Tongue Surgery

- The tongue has an established role in obstruction in sleep apnea. One treatment involves moving one of the main tongue muscles, the genioglossus muscle, forward; thereby limiting the backward fall of the tongue during sleep. This procedure addresses the same sites of potential obstruction as the hyoid advancement, and numerous studies have shown a high success rate. Another effective surgical treatment to reduce is to reduce the amount of tissue at the tongue base.

- UPPP

- UPPP, or in full, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, has been the most common sleep apnea surgical procedure performed during the past 25 years. This procedure was developed to remove excess tissue from the soft palate and pharynx to remove the obstruction from the upper airway.

Patients who suffer from snoring gain a great deal of improvement from this procedure as snoring is often due to the reverberation of the soft palate with the back wall of the pharynx.

Patients who suffer from snoring gain a great deal of improvement from this procedure as snoring is often due to the reverberation of the soft palate with the back wall of the pharynx.

- UPPP, or in full, uvulopalatopharyngoplasty, has been the most common sleep apnea surgical procedure performed during the past 25 years. This procedure was developed to remove excess tissue from the soft palate and pharynx to remove the obstruction from the upper airway.

- Hyoid Advancement

- The hyoid bone is a small bone in the neck where the muscles of the tongue base and pharynx attach. Patients with sleep apnea often have a large tongue base. During the deep stages of sleep, normal muscle tone is relaxed, and the base of the tongue falls back and can make contact with the back wall of the pharynx resulting in obstruction. Through a very minimally invasive procedure, the hyoid bone is surgically repositioned anteriorly by placing a suture around it and suspending it to the front of the jaw bone. This procedure results in an expansion of the airway and prevents collapse.

- Lower Jaw Advancement

- Abnormality of the maxillofacial skeleton is a well-recognized risk factor of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep apnea patients usually have small, narrow jaws that result in diminished airway dimension, which leads to nocturnal obstruction.

Maxillomandibular advancement achieves enlargement of the entire upper airway through the expansion of the skeletal framework that encircles the airway.

Maxillomandibular advancement achieves enlargement of the entire upper airway through the expansion of the skeletal framework that encircles the airway.

- Abnormality of the maxillofacial skeleton is a well-recognized risk factor of obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep apnea patients usually have small, narrow jaws that result in diminished airway dimension, which leads to nocturnal obstruction.

- Tracheostomy

- Tracheostomy is a technique that creates a passageway for air to get to the lungs directly from the trachea in the neck. This technique bypasses any potential sites of obstruction from the upper airway. Permanent tracheostomy as a long-term treatment of obstructive sleep apnea remains an option when all other forms of non-surgical and surgical treatments have failed. Though it may seem excessive, it is an extremely effective surgical option reserved for the very sick patient.[2]

Key Takeaways: Sleep Apnea

SIDS

Figure 2. The Safe to Sleep campaign educates the public about how to minimize risk factors associated with SIDS. This campaign is sponsored in part by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

In sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), an infant stops breathing during sleep and dies. Infants younger than 12 months appear to be at the highest risk for SIDS, and boys have a greater risk than girls. A number of risk factors have been associated with SIDS, including premature birth, smoking within the home, and hyperthermia. There may also be differences in both brain structure and function in infants that die from SIDS (Berkowitz, 2012; Mage & Donner, 2006; Thach, 2005).

Infants younger than 12 months appear to be at the highest risk for SIDS, and boys have a greater risk than girls. A number of risk factors have been associated with SIDS, including premature birth, smoking within the home, and hyperthermia. There may also be differences in both brain structure and function in infants that die from SIDS (Berkowitz, 2012; Mage & Donner, 2006; Thach, 2005).

The substantial amount of research on SIDS has led to a number of recommendations to parents to protect their children (Figure 2). For one, research suggests that infants should be placed on their backs when put down to sleep, and their cribs should not contain any items that pose suffocation threats, such as blankets, pillows, or padded crib bumpers (cushions that cover the bars of a crib). Infants should not have caps placed on their heads when put down to sleep in order to prevent overheating, and people in the child’s household should abstain from smoking in the home. Recommendations like these have helped to decrease the number of infant deaths from SIDS in recent years (Mitchell, 2009; Task Force on Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, 2011).

Try It

Glossary

central sleep apnea: sleep disorder with periods of interrupted breathing due to a disruption in signals sent from the brain that regulate breathing

continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP): device used to treat sleep apnea; includes a mask that fits over the sleeper’s nose and mouth, which is connected to a pump that pumps air into the person’s airways, forcing them to remain open

obstructive sleep apnea: sleep disorder defined by episodes when breathing stops during sleep as a result of blockage of the airway

sleep apnea: sleep disorder defined by episodes during which breathing stops during sleep

sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS): infant (one-year-old or younger) with no apparent medical condition suddenly dies during sleep

- Sleep Apnea - Causes & Symptoms. Sleep Foundation. (2020, September 25). https://www.sleepfoundation.

org/sleep-apnea. ↵

org/sleep-apnea. ↵ - Sleep Apnea - Treatment Options. Sleep Foundation. (2020, September 25). https://www.sleepfoundation.org/sleep-apnea. ↵

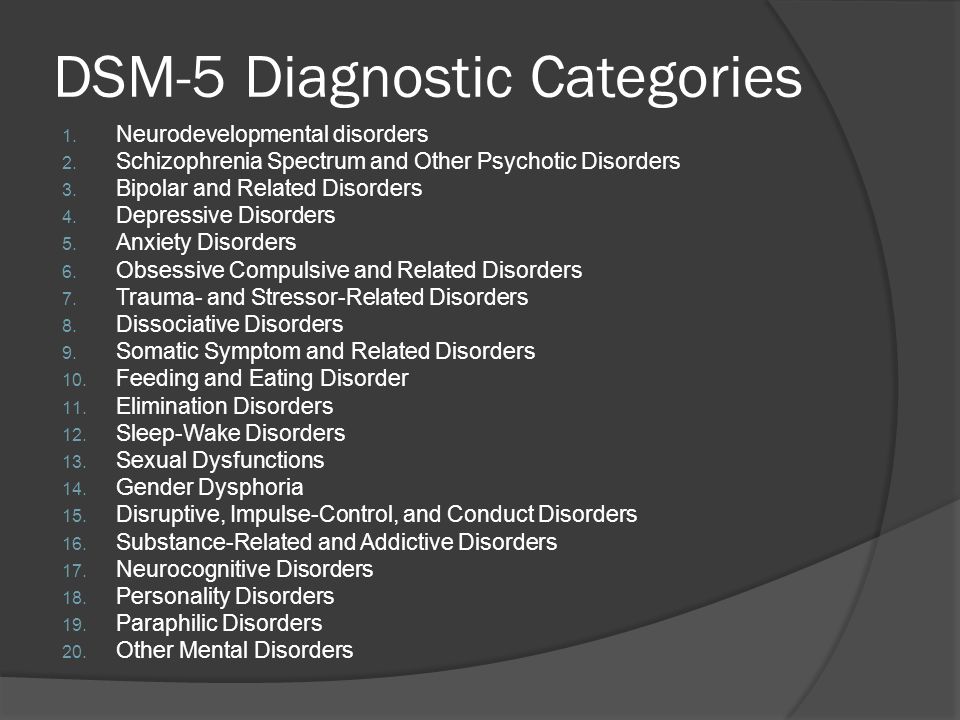

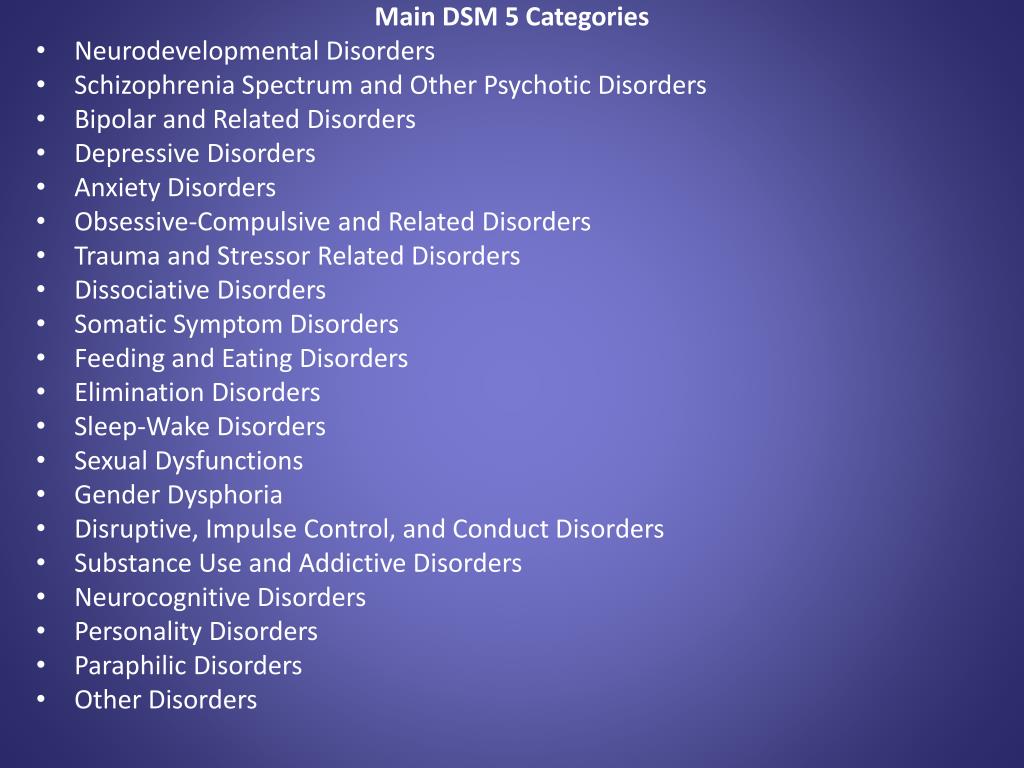

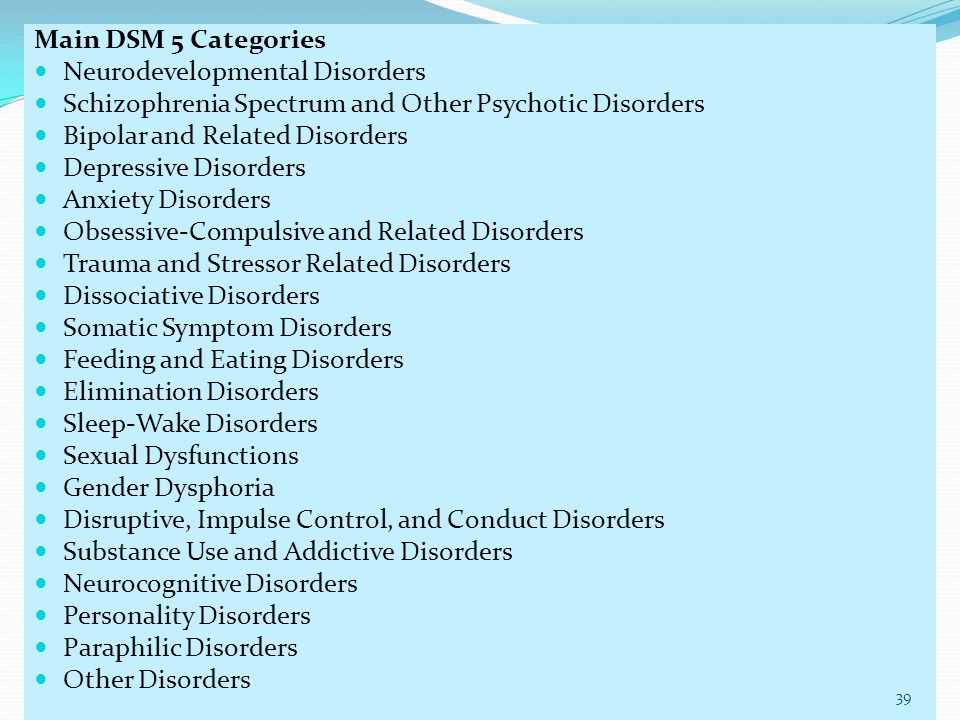

DSM 5 Sleep Disorders: Names and Classifications

The DSM-5 Sleep Disorders workgroup has been especially busy. They are calling for a nearly complete overhaul of the sleep disorders category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (“DSM”).

According to a presentation at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in May, Charles Reynolds, MD, suggested that the reworking of this category will make sleep problems easier for professionals to diagnose and discriminate between different sleep disorders.

He stated that the current DSM-IV puts too much emphasis on presumed causes of symptoms, something that the rest of the DSM-IV does not do. Bringing the sleep disorder section more in line with the other sections in the DSM should make it less confusing.

Primary and commonly diagnosed sleep disorders are being organized in the DSM-5 into three major categories: insomnia, hypersomnia and arousal disorder. The new DSM will allow professionals to choose amongst sub-types in each category, as can be done with many other major disorders in the manual.

The new DSM will allow professionals to choose amongst sub-types in each category, as can be done with many other major disorders in the manual.

Here’s a summary of some of the proposed additions and changes in the sleep disorders category for the DSM-5, slated for publication in May 2013.

These sleep disorders criteria are summarized from the proposed changes found on the DSM 5 website.

Kleine Levin Syndrome

This syndrome is characterized by a person who experiences recurrent episodes of excessive sleep (more than 11 hours/day). These episodes occur at least once a year, and are between 2 days and 4 weeks in duration.

During one of these episodes, when awake, cognition is abnormal with feeling of unreality or confusion. Behavioral abnormalities such as megaphagia or hypersexuality may occur in some episodes.

The patient has normal alertness, cognitive functioning, and behavior between the episodes.

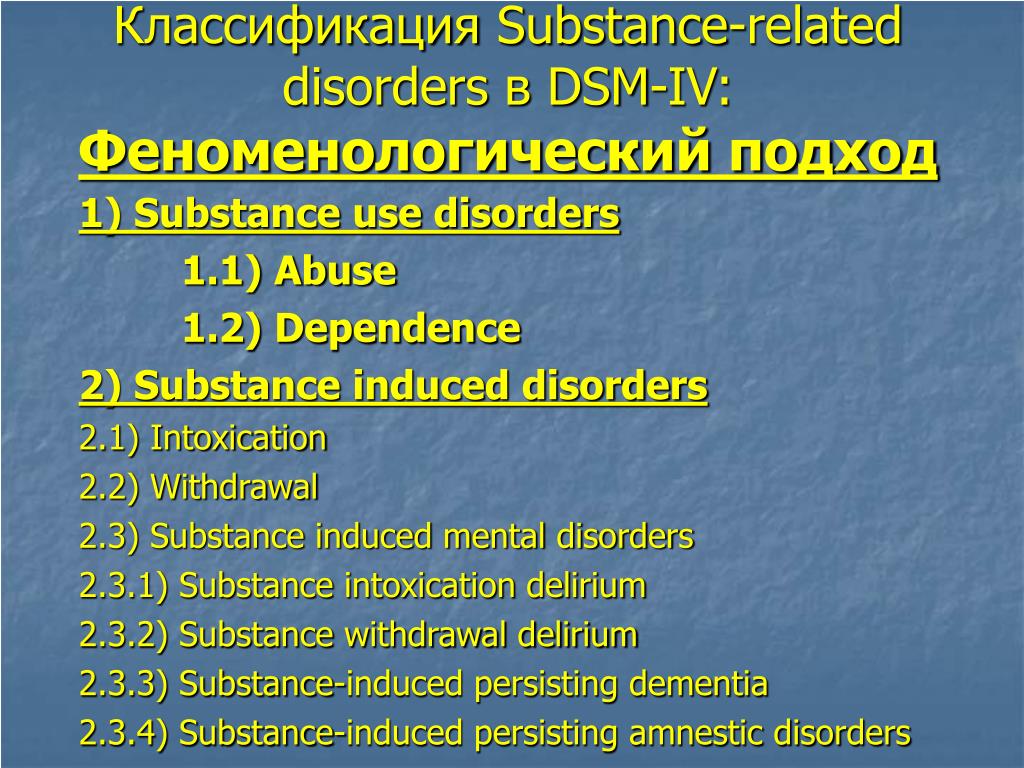

Obstructive Sleep Apnea Hypopnea Syndrome

(Previously known as Breathing Related Sleep Disorder)

- Symptoms of snoring, snorting/gasping or breathing pauses during sleep

- Symptoms of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or unrefreshing sleep despite sufficient opportunities to sleep and unexplained by another medical or psychiatric morbidityAND

- Evidence by polysomnography (a type of measurement of sleep breathing used in a sleep lab) of 5 or more obstructive apneas or hypopneas per hour of sleep or evidence by polysomnography of 15 more obstructive apneas and/or hypopneas per hour of sleep.

Primary Central Sleep Apnea

(Previously known as Breathing Related Sleep Disorder)

At least one of the following is present:

- Excessive daytime sleepiness

- Frequent arousals and awakenings during sleep or insomnia complaints

- Awakening short of breath

Polysomnography (a type of measurement of sleep breathing used in a sleep lab) shows five or more central apneas per hour of sleep.

Primary Alveolar Hypoventilation

(previously Breathing Related Sleep Disorder)

Polysomnographic (a type of measurement of sleep breathing used in a sleep lab) monitoring demonstrates episodes of shallow breathing longer than 10 seconds in duration associated with arterial oxygen desaturation and frequent arousals from sleep associated with the breathing disturbances or brady-tachycardia. Note: although symptoms are not mandatory to make this diagnosis, patients often report excessive daytime sleepiness, frequent arousals and awakenings during sleep, or insomnia complaints.

Rapid Eye Movement Behavior Disorder

This disorder is characterized by repeated episodes of arousal during sleep associated with vocalization and/or complex motor behaviors which may be sufficient to result in injury to the individual or bed partner.

These behaviors arise during REM sleep and therefore usually occur greater that 90 minutes after sleep onset, are more frequent during the later portions of the sleep period, and rarely occur during daytime naps.

Upon awakening, the individual is completely awake, alert, and not confused or disoriented.

The observed vocalizations or motor behavior often correlate with simultaneously occurring dream mentation leading to the report of “acting out of dreams”.

The behaviors cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social or other important areas of functioning — particularly pertaining to distress to bed partner or injury to self or bed partner.

At least one of the following is present: 1) Sleep related injurious, potentially injurious, or disruptive behaviors arising from sleep and 2) Abnormal REM sleep behaviors documented by polysomnographic recording.

Restless Legs Syndrome

The exact criteria used to diagnose Restless Legs Syndrome has not been decided. But one set of criteria proposed include a patient meeting all of the following:

- An urge to move the legs usually accompanied or caused by uncomfortable and unpleasant sensations in the legs (or for pediatric RLS the description of these symptoms should be in the child’s own words).

- The urge or unpleasant sensations begin or worsen during periods of rest or inactivity.

- Symptoms are partially or totally relieved by movement

- Symptoms are worse in the evening or at night than during the day or are present only at night or in the evening. (The worsening occurs independently of any differences in activity, which is important for pediatric RLS as children are sitting much of the day at school).

These symptoms are accompanied by significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, academic, behavioral or other important areas of functioning indicated by the presence of at least one of the following:

- Fatigue or low energy

- Daytime sleepiness

- Cognitive impairments (e.

g., attention, concentration, memory, learning)

g., attention, concentration, memory, learning) - Mood disturbance (e.g., irritability, dysphoria, anxiety)

- Behavioral problems (e.g., hyperactivity, impulsivity, aggression)

- Impaired academic or occupational function

- Impaired interpersonal/social functioning

Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder

This disorder is characterized by a persistent or recurrent pattern of sleep disruption leading to excessive sleepiness, insomnia, or both that is primarily due to an alteration of the circadian system or to a misalignment between the endogenous circadian rhythm and the sleep-wake schedule required by a person’s physical environment or social/professional schedule.

Disorder of Arousal

(Includes previous diagnoses of Sleepwalking Disorder and Sleep Terror Disorder)

Recurrent episodes of incomplete awakening from sleep usually occurring during the first third of the major sleep episode.

Subtypes:

- Confusional Arousals: Recurrent episodes of incomplete awakening from sleep without terror or ambulation, usually occurring during the first third of the major sleep episode.

There is a relative lack of autonomic arousal such as mydriasis, tachycardia, rapid breathing, and sweating during an episode.

There is a relative lack of autonomic arousal such as mydriasis, tachycardia, rapid breathing, and sweating during an episode. - Sleepwalking: Repeated episodes of rising from bed during sleep and walking about, usually occurring during the first third of the major sleep episode. While sleepwalking, the person has a blank, staring face, is relatively unresponsive to the efforts of others to communicate with him or her, and can be awakened only with great difficulty.

- Sleep terrors: Recurrent episodes of abrupt awakening from sleep, usually occurring during the first third of the major sleep episode and beginning with a panicky scream. There is intense fear and signs of autonomic arousal, such as mydriasis, tachycardia, rapid breathing, and sweating, during each episode.

Relative unresponsiveness to efforts of others to comfort the person during the episode.

No detailed dream is recalled and there is amnesia for the episode.

Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorder

This disorder is characterized by a persistent or recurrent pattern of sleep disruption leading to excessive sleepiness, insomnia, or both that is primarily due to an alteration of the circadian system or to a misalignment between the endogenous circadian rhythm and the sleep-wake schedule required by a person’s physical environment or social/professional schedule.

Subtypes:

- Free-Running Type: a persistent or recurrent pattern of sleep and wake cycles that are not entrained to the 24 hour environment, with a daily drift (usually to later and later times) of sleep onset wake times

- Irregular Sleep –Wake Type: a temporally disorganized sleep and wake pattern, so that sleep and wake periods are variable throughout the 24 hour period.

As with all mental disorders, sleep disorders must cause a significant impact or distress in the person’s normal, everyday functioning in their life — work, at home, and at play. All of the sleep disorders listed above are proposed to generally not be diagnosed if directly caused by a known medical condition, disease, or impairment in the person’s health.

All of the sleep disorders listed above are proposed to generally not be diagnosed if directly caused by a known medical condition, disease, or impairment in the person’s health.

New American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 released to the world

Home > News > The new American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 is released to the world

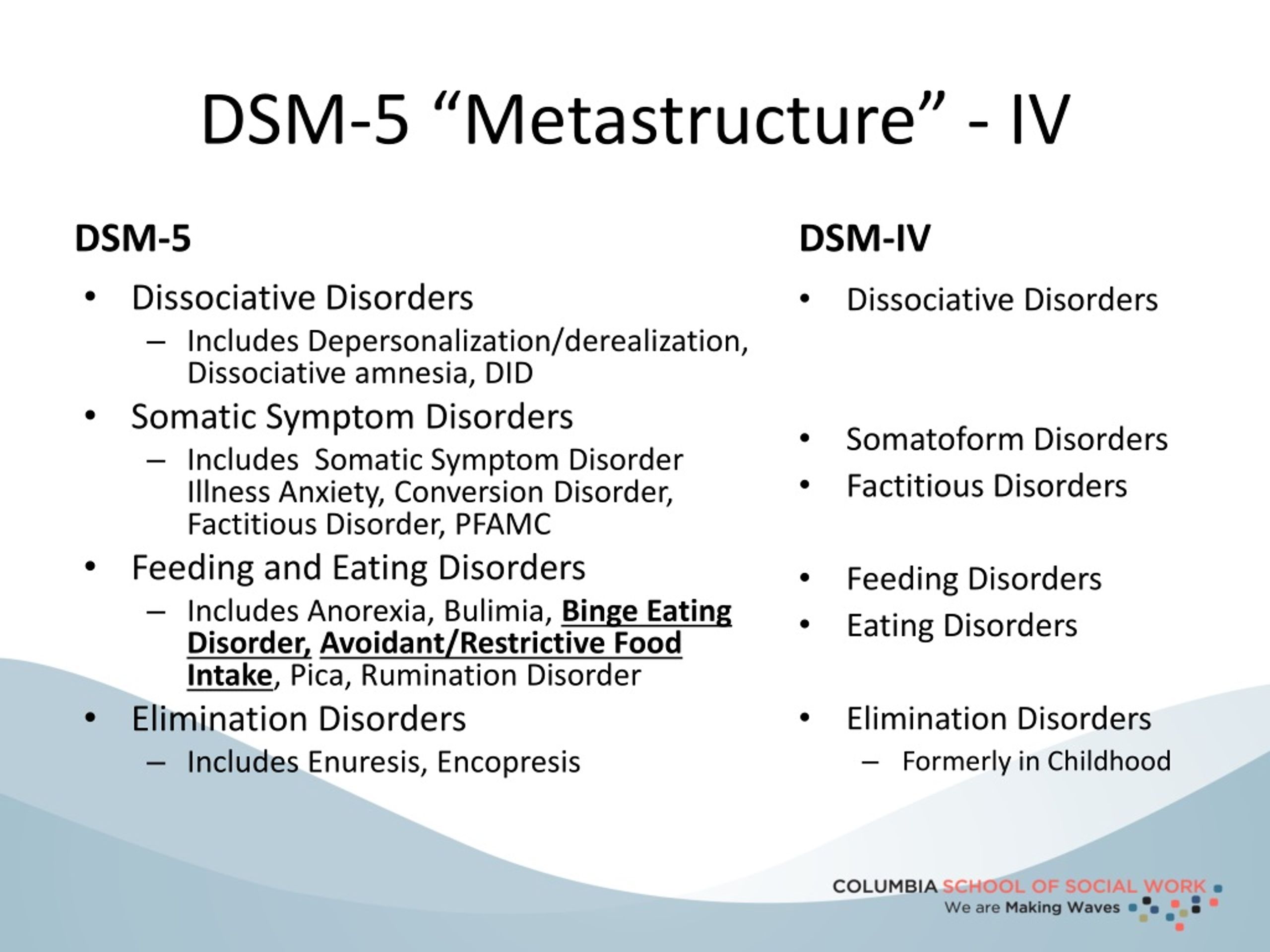

| DSM-5 consists of three sections: it is (1) an introductory part with instructions for use and a warning about the forensic psychiatric use of the DSM-5; (2) diagnostic criteria and codes for routine clinical use; and (3) tools and techniques to inform clinical decision making. nine0003 Major changes:

The severity of the disorder is not determined by IQ, but by the level of adaptive functioning. Speech disorders have entered the new category "social communication disorder", in which some of the syndromes coincide with "autism spectrum disorder".

For the diagnosis of schizophrenia, symptoms of the first Schneider rank lose their special weight. One positive symptom is required for a diagnosis to be made. Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately. The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders.

Bipolar and related disorders are now separated from depressive disorders and placed in a separate category. A clearer definition of mania is given and refinements for mixed episodes are introduced, which lowers the threshold for disorder. Added a residual subcategory ""other"" and a qualifying score for anxiety symptoms.

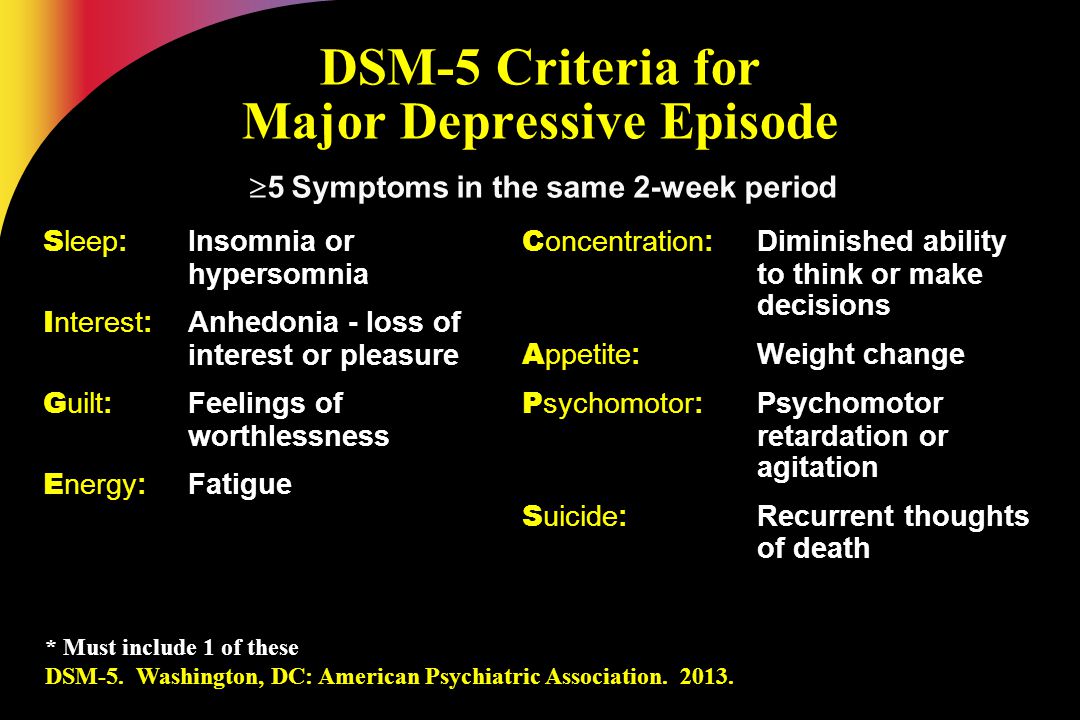

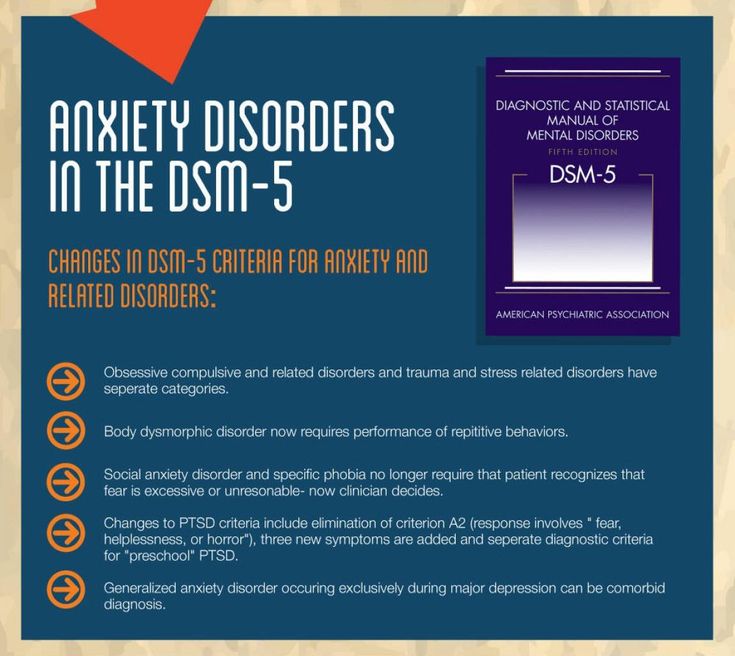

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder added. Chronic depression and dysthymia are combined into one diagnosis, now it is ""persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)"" with a number of clarifying indicators. Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator ""mixed manifestations"" was introduced. A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. nine(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled.

|

ISSN 2588-0519 (Print)

ISSN 2618-8473 (Online)

The structure of breathing disorders during sleep and cognitive disorders in cerebrovascular diseases | Geraskina

1. Yakhno NN, Zakharov VV, Lokshina AB, etc. Dementia. Moscow: Medpress-inform. 2011. [Yakhno NN, Zakharov VV, Lokshina AB et al. Dementii. Moscow: Medpress-inform. 2011. (In Russian)]. nine0003

2. Yakhno NN. Cognitive impairment in neurological practice. Neurological journal. 2006;11(1):4–12. [Yakhno NN. Cognitive impairment in neurological practice. Neurologicheskii Zhurnal. 2006;11(1):4–12. (In Russian)].

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013:992.

Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing. 2013:992.

4. Parfenov VA. Vascular cognitive impairment and chronic cerebral ischemia (dyscirculatory encephalopathy). Neurology, neuropsychiatry, psychosomatics. 2019;11(3):61–67. [Parfenov V.A. Vascular cognitive impairment and chronic cerebral ischemia (dyscirculatory encephalopathy). Neurology, Neuropsychiatry, Psychosomatics. 2019;11(3):61–67. (In Russian)]. Doi: 10.14412/2074-2711-2019-3S-61-67.

5. Suslina ZA, Varakin Yuya. Clinical guide for early diagnosis, treatment and prevention of cerebrovascular diseases. M. 2015:440. [Suslina ZA, Varakin UA. Clinical guidelines for early diagnosis, treatment and prevention of vascular diseases of the brain. M. 2015:440. (In Russian)]. nine0003

6. Bucks RL, Olaithe M, Rosenzweig I, Morreli MJ. Reviewing the relationship between OSA and cognition: where do we go from here? Respirology. 2017;22(7):1253–1261. DOI: 10.1111/resp.13140. PMID: 28779504.

7. Daurat A, Huet N, Tiberge M. Metamemory beliefs and episodic memory in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Psychol. Rep. 2010;107(1):289–302. DOI:10.2466/10.13.20.22.PR0.107.4.289-302. PMID: 20923074.

Metamemory beliefs and episodic memory in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Psychol. Rep. 2010;107(1):289–302. DOI:10.2466/10.13.20.22.PR0.107.4.289-302. PMID: 20923074.

8. Leng Y, McEvoy CT, Allen IE et al. Association of sleepdisorder breathing with cognitive function and risk of cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(10):1237–1245. DOI: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2017.2180. PMID: 28846764.

9. Kielb SA, Ancoli-Israel S, Rebok GW et al. Cognition in obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome (OSAS): Current clinical knowledge and the impact of treatment. neuromolecular medicine. 2012;14(3):180–193. DOI: 10.1007/S12017-012-8182-1. PMID: 22569877. PCMID: PMC3823054.

10. Rosenzweig I, Williams SC, Morrell MJ. The impact of sleep and hypoxia on the brain: potential mechanisms for the effects of obstructive sleep apnea. Current Opinion in Pulmonary Medicine. 2014;20(6):565–571. DOI: 10.1097/MCP.0000000000000099. PMID: 25188719.

11. Rosenzweig I, Glasser M, Polsek D et al. Sleep apnea and the brain: a complex relationship. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2015;3(5):404–414. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00090-9. PMID: 25887982.

Rosenzweig I, Glasser M, Polsek D et al. Sleep apnea and the brain: a complex relationship. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine. 2015;3(5):404–414. DOI: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00090-9. PMID: 25887982.

12. Orr JE, Malhotra A, Sands SA. Pathogenesis of central and complex sleep apnea. Respirology. 2017;22(1):43–52. DOI: 10.1111/resp.12927. PMID: 27707160.

13. Drager LF, McEvoy RD, Barbe F et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: lessons from recent trials and need for team science. circulation. 2017;136(19):1840–1850. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029400. PMID: 29109195.

14. Munoz R, Duran-Cantolla J, Martinez-Vila E et al. Central sleep apnea is associated with increased risk of ischemic stroke in the elderly. acta. Neurol. Scand. 2012;126(3):183–1888. DOI: 10.1111/j.1600-0404.2011.01625.x. PMID: 22150745.

15. Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V et al. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: a brief screening tool for mild cognitive impairment. J. Am. Geriatr. soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. PMID: 15817019.

Am. Geriatr. soc. 2005;53(4):695–699. DOI: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53221.x. PMID: 15817019.

16. Berry RB, Budhiraja R, Gottlieb DJ et al. Rules for scoring respiratory events in sleep: update of the 2007 AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Deliberations of the Sleep Apnea Definitions Task Force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J.Clin. Sleep Med. 2012;8(5):597–619. DOI: 10.5664/jcsm.2172. PMID: 23066376.

17. Jennum P, Riha RL. Epidemiology of sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome and sleep-disordered breathing. Eur. Respir. J. 2009;33(4):907–914. DOI: 10.1183/09031936.00180108. PMID: 19336593.

18. Wu Z, Chen F, Yu F, Guo Z. A meta-analysis of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with cerebrovascular disease. Sleep Breath. 2018;22(3):729–742. DOI: 10.1007/s11325-017-1604-4. PMID: 29248975.

19. Dong R, Dong Z, Liu H et al. Prevalence, risk factors, outcomes, and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea in patients with cerebrovascular disease: A systematic review. J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018;27(6):1471–1480. DOI:10.1016/j.jstrok ecerebrovasdis.2017.12.048. PMID: 29555400.

J. Stroke Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2018;27(6):1471–1480. DOI:10.1016/j.jstrok ecerebrovasdis.2017.12.048. PMID: 29555400.

20. Davis AP, Billings ME, Longstreth WT, Jr., Khot SP. Early diagnosis and treatment of obstructive sleep apnea after stroke: Are we neglecting a modifiable stroke risk factor? Neurol. Clin. Pract. 2013;3(3):192–201. DOI: 10.1212/CPJ.0b013e318296f274. PMID: 23914326/ PMCID: PMC3721244.

21. Lutokhin GM, Geraskina LA, Fonyakin AV, Maksimova MYu. Optimization of early rehabilitation of patients with ischemic stroke and respiratory failure during sleep. Annals of clinical and experimental neurology. 2017;2:5–13. [Lutohin GM, Geraskina LA, Fonakin AV, Maksimova MU. Optimization of early rehabilitation of patients with ischemic stroke and sleep breathing disorders. Annals of clinical and experimental neurology. 2017;2:5–13. (In Russian)]. DOI: 10.18454/ACEN.2017.2.1. nine0003

22. Van der Flier WM, Skoog I, Schneider JA et al. Vascular cognitive impairment. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2018;4:18003. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.3. PMID: 29446769.

Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2018;4:18003. DOI: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.3. PMID: 29446769.

23. Yaneva-Sirakova T, Traykov L, Petrova J et al. Screening for mild cognitive impairment in patients with cardiovascular risk factors. Neuropsychiatr. Dis. treat. 2017;13:2925–2934. DOI: 10.2147/NDT.S144264. PMID: 29255360.

24. Siebert JS, Wahl HW, Degen C et al. Attitude toward own aging as a risk factor for cognitive disorder in old age: 12-year evidence from the ILSE study. Psychol. Aging. 2018;33(3):461–472. DOI: 10.1037/pag0000252. PMID: 29756803.

25. Alkan A, Sharifov R, Akkoyunlu ME et al. MR spectroscopy features of brain in patients with mild and severe obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Clin. Imaging. 2013;37(6):989–992. DOI: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2013.07/010. PMID: 23993754.

26. Xia Y, Fu Y, Xu H et al. Changes in cerebral metabolites in obstructive sleep apnea: a systemic review and meta-analysis. sci. Rep. 2016;6:23712. DOI: 10.1038/srep28712. PMID: 27349417.

27. Yaouhi K, Bertran F, Clochon P et al. A combined neuropsychological and brain imaging study of obstructive sleep apnea. J. Sleep. Res. 2009;18(1):36–48. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00705.x. PMID: 19250174.

Yaouhi K, Bertran F, Clochon P et al. A combined neuropsychological and brain imaging study of obstructive sleep apnea. J. Sleep. Res. 2009;18(1):36–48. DOI: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00705.x. PMID: 19250174.

28. Lim DC, Pack AI. Obstructive sleep apnea and cognitive impairment: addressing the blood-brain barrier. Sleep Med. Rev. 2014;18(1):35–48. DOI: 10.1016/j.smrv.2012.12.003. PMID: 23541562. PCMID: PMC3758447.

29. Morisson F, Decary A, Petit D et al. Daytime sleepiness and EEG spectral analysis in apneic patients before and after treatment with continuous positive airway pressure. Chest. 2001;119(1):45–52. DOI: 10.1378/chest.119.1.45. PMID: 11157583.

30. Bucks RS, Olaithe M, Eastwood P. Neurocognitive function in obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-review. Respirology. 2013;18(1):61–70. DOI: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2012.02255.x. PMID: 22913604.

31. Xue M, Xu W, Ou YN et al. Diabetes mellitus and risk of cognitive impairment and dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 144 prospective studies. Aging Res. Rev. 2019;55:100944. DOI: 10.106/j.arr.2019.100944. PMID 31430566.

Aging Res. Rev. 2019;55:100944. DOI: 10.106/j.arr.2019.100944. PMID 31430566.

32. Terpening Z, Lewis SJ, Yee BJ et al. Association between sleepdisordered breathing and neuropsychological performance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment. J. Alzheimers. Dis. 2015;46(1):157–165. DOI: 10.3233/JAD-141860. PMID: 25720400.

33. Li N, Wang J, Wang D et al. Correlation of sleep microstructure with daytime sleepiness and cognitive function in young and middle-aged adults with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276(12):3525–3532. DOI: 10.1007/s00405-019-05529-y. PMID: 31263979.

34. Nopmaneejumruslers C, Kaneko Y, Hajek V et al. Cheynestokes respiration in stroke: Relationship to hypocapnia and occult cardiac dysfunction. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2005;171(9):1048–1052. DOI: 10.1164/rccm.200411-1591OC. PMID: 15665317.

35. Duning T, Deppe M, Brand E et al. Brainstem involvement as a cause of central sleep apnea: pattern of microstructural cerebral damage in patients with cerebral microangiopathy.

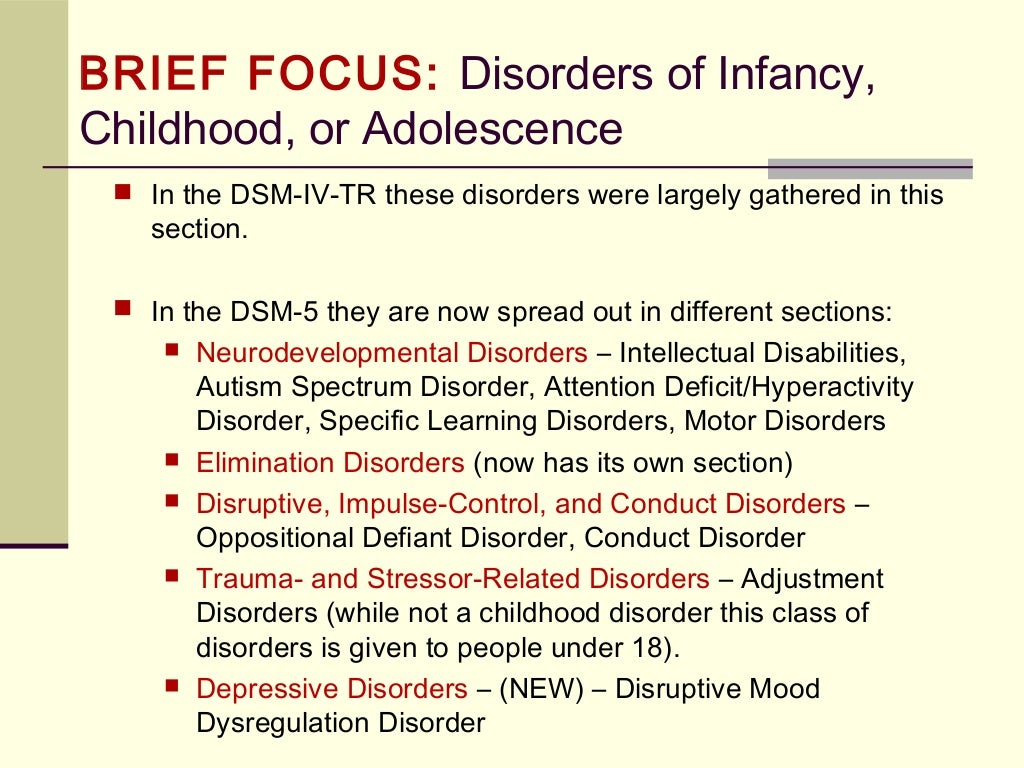

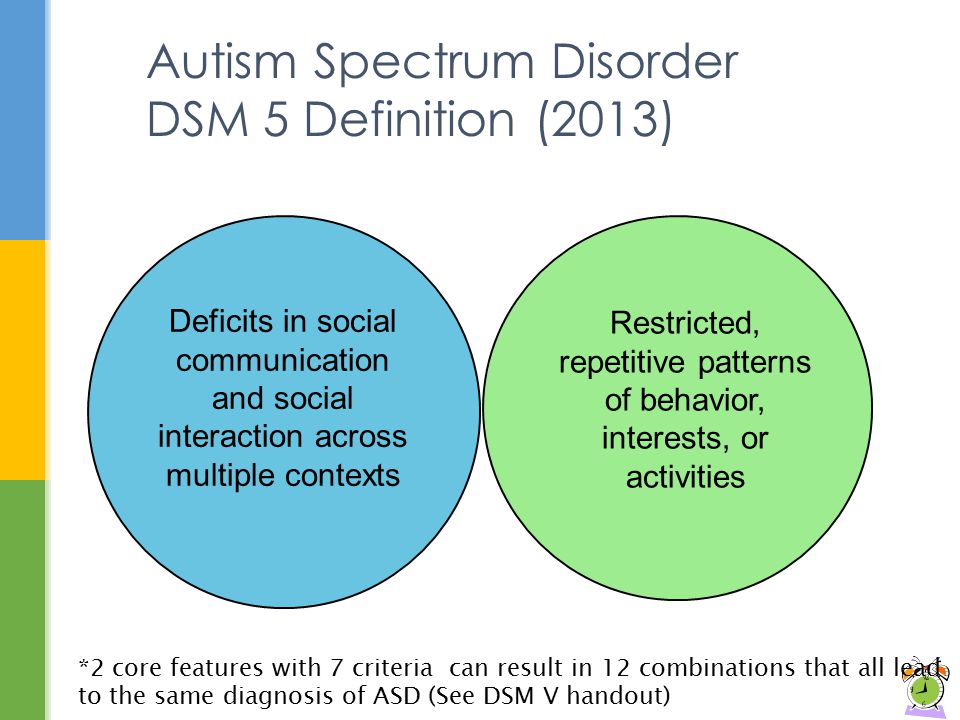

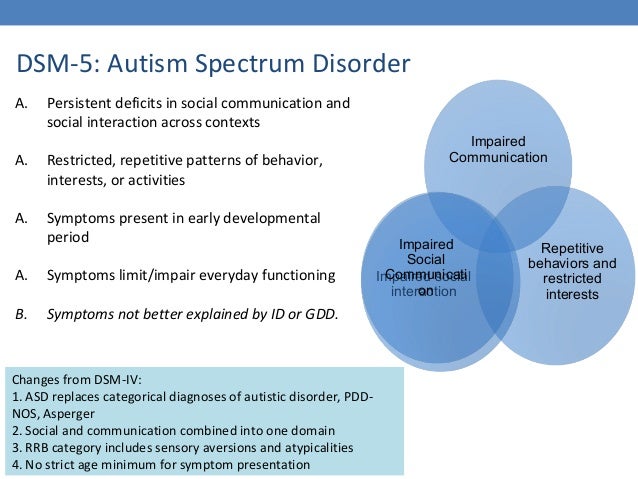

The category "Autism Spectrum Disorders" replaces the DSM-4 diagnoses of autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and an unspecified general developmental disorder, all of which cease to exist as separate diagnoses. ADHD can start later (before 12) and is treated differently in different areas. Learning disorders and movement disorders are organized differently in this chapter and somewhat combined. nine0003

The category "Autism Spectrum Disorders" replaces the DSM-4 diagnoses of autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and an unspecified general developmental disorder, all of which cease to exist as separate diagnoses. ADHD can start later (before 12) and is treated differently in different areas. Learning disorders and movement disorders are organized differently in this chapter and somewhat combined. nine0003  nine0003

nine0003  Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses. nine0003

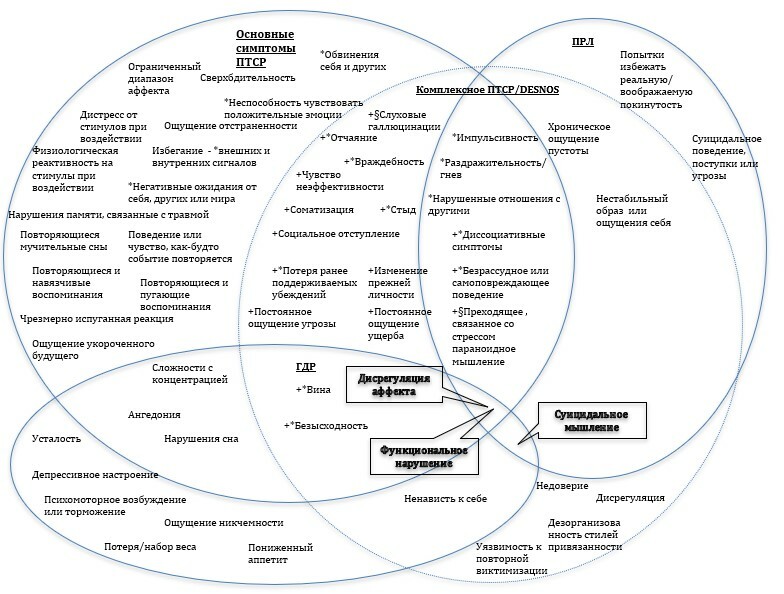

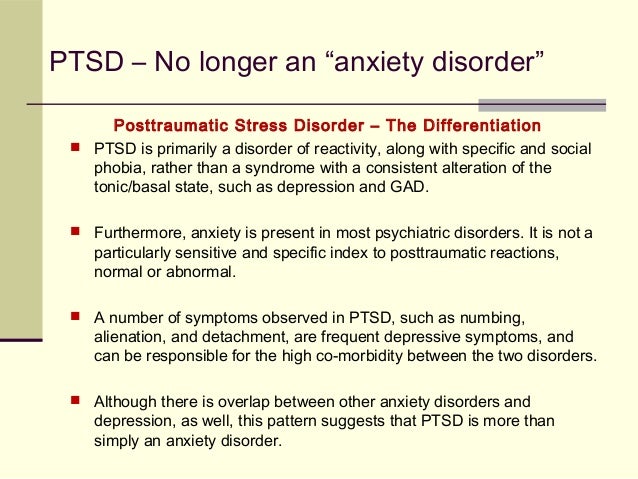

Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses. nine0003  Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter. nine0003

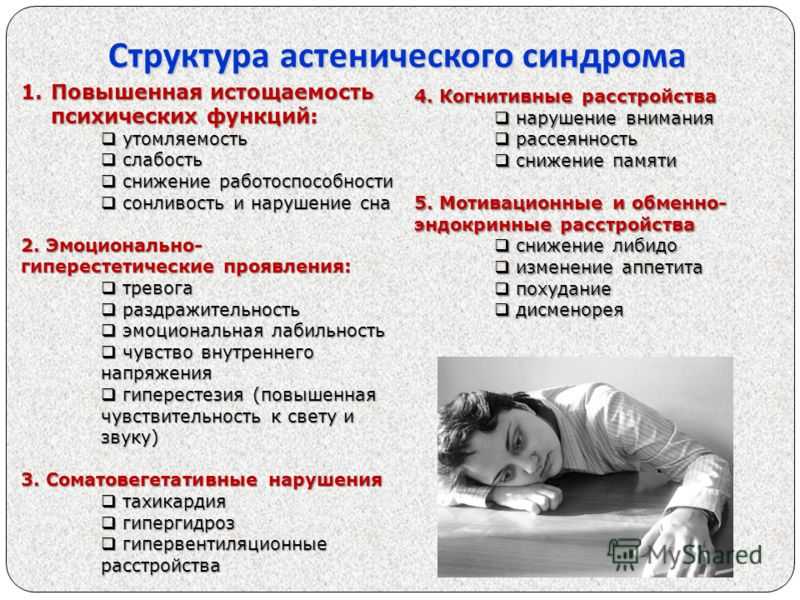

Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter. nine0003  A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group. nine0003

A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group. nine0003  The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses. nine0003

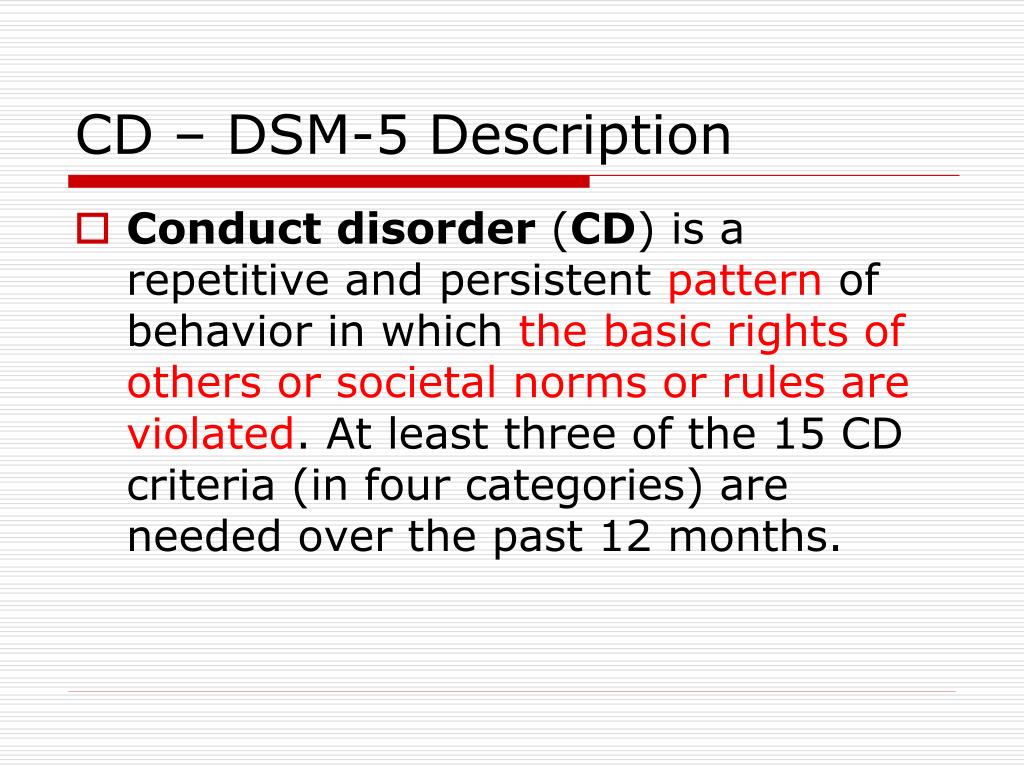

The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses. nine0003  In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined. nine0003

In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined. nine0003  nine0003

nine0003