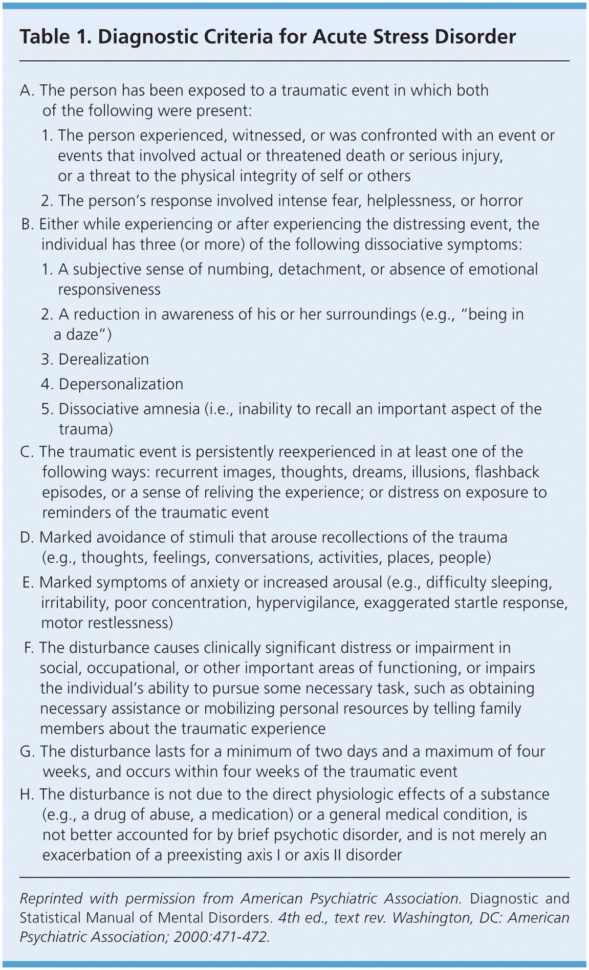

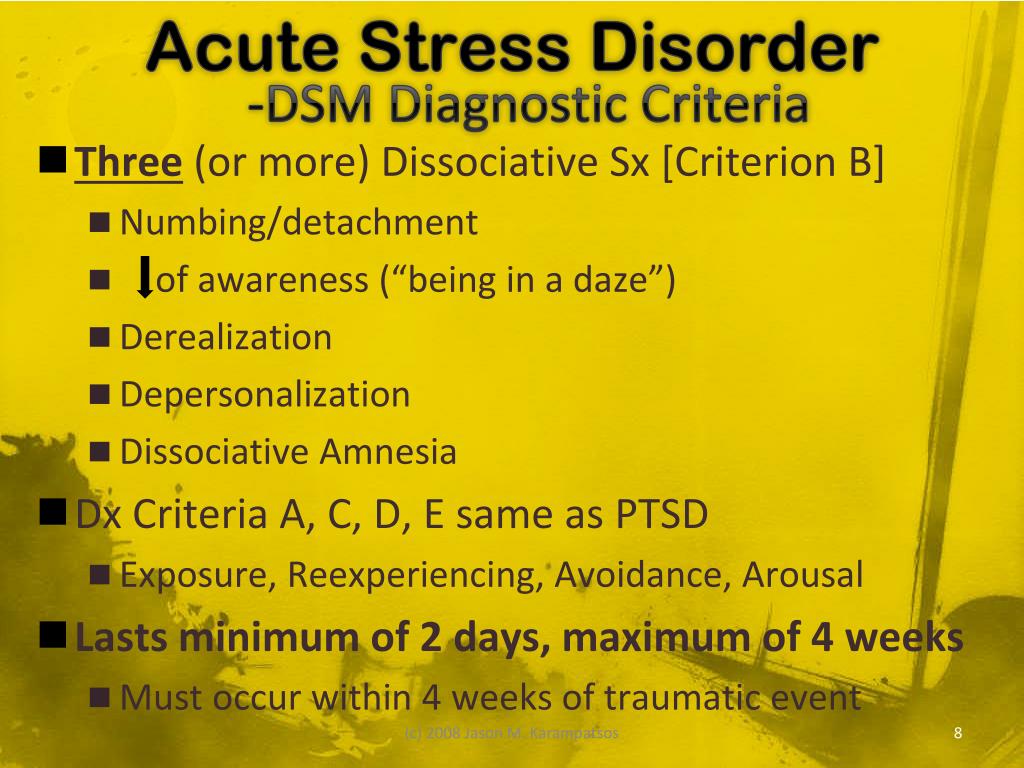

Acute stress disorder diagnostic criteria

Acute Stress Disorder / Reaction, DSM 5 Code 308.3

Acute Stress Disorder

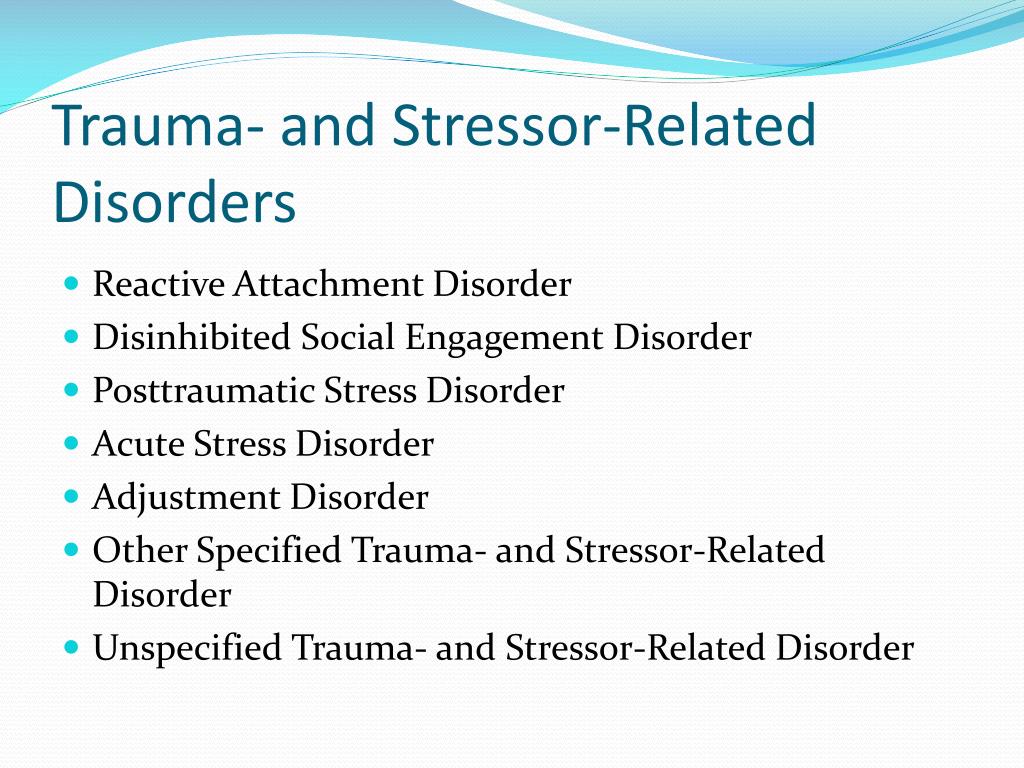

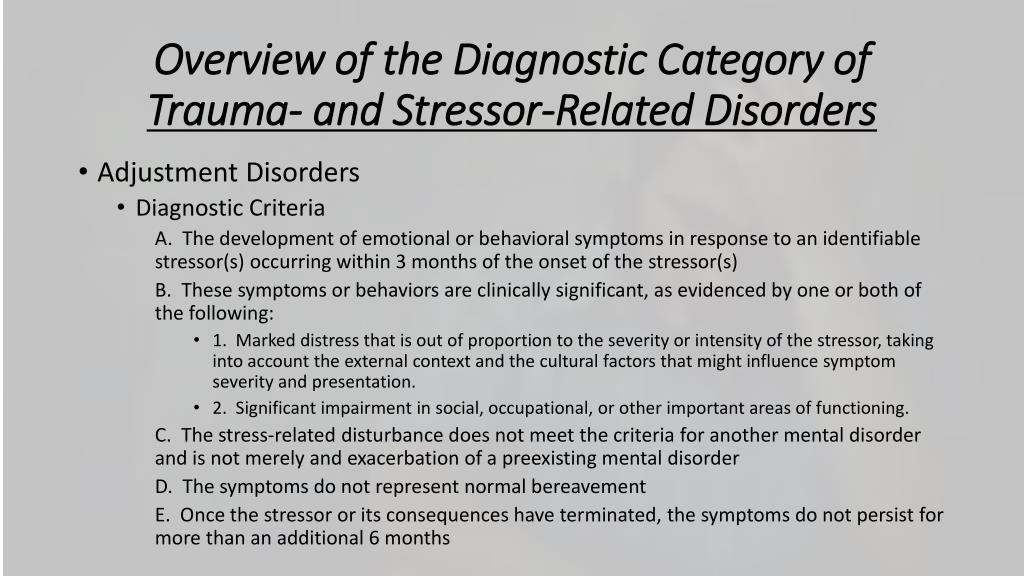

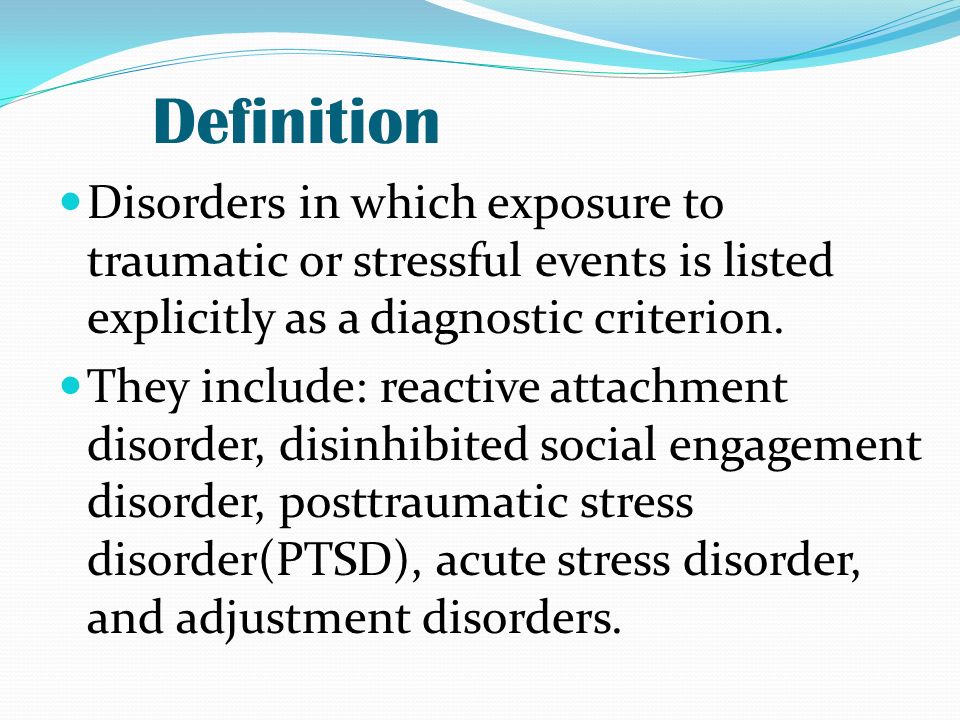

Acute Stress Disorder is a caused by trauma (traumatic stress) and lasts at least 3 days. The DSM-5 manual states that stressful events which do not include severe and traumatic components do not lead to Acute Stress Disorder; Adjustment Disorder may be an appropriate diagnosis.

Acute Stress Disorder explained

Acute Stress Disorder develops after exposure to one or more traumatic events, e.g., exposure to war (both civilians and military personnel), rape or sexual violence, physical attack, mugging, childhood physical or sexual violence, kidnapping or being taken hostage, terrorist attacks, torture, nature disasters and severe accidents. Many other causes of trauma are possible. [1]

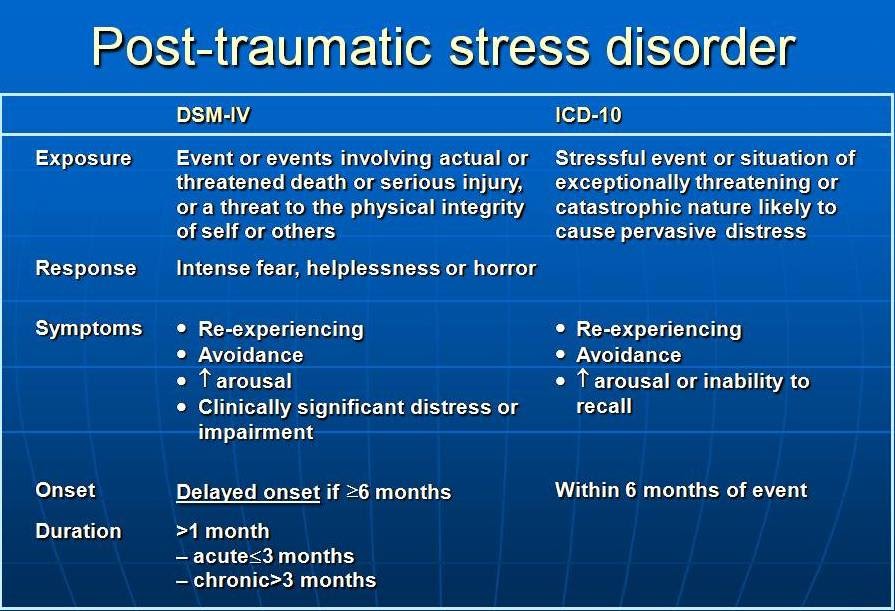

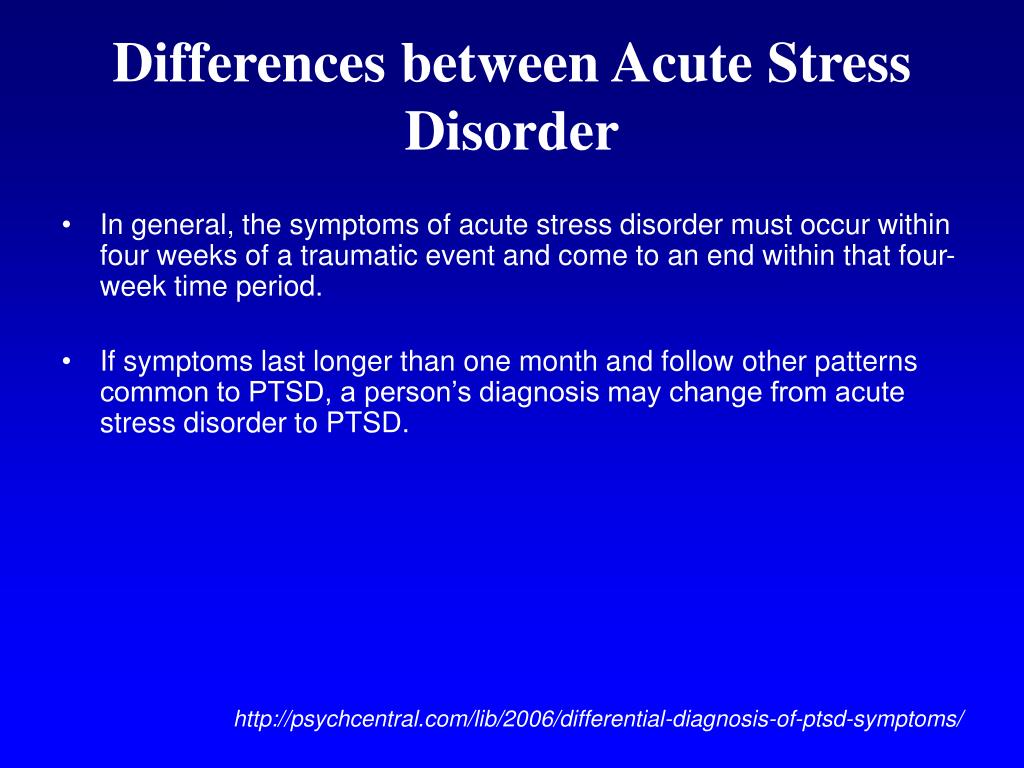

Note: The International Classification of Diseases refers to Acute Stress Reaction,[2] [4] which is slightly different and results from an "exceptionally stressful life event" or "continous trauma", and typically lasts between a few hours and a few days. [3] Both Acute Stress Disorder and Acute Stress Reaction have symptoms which are similar to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.

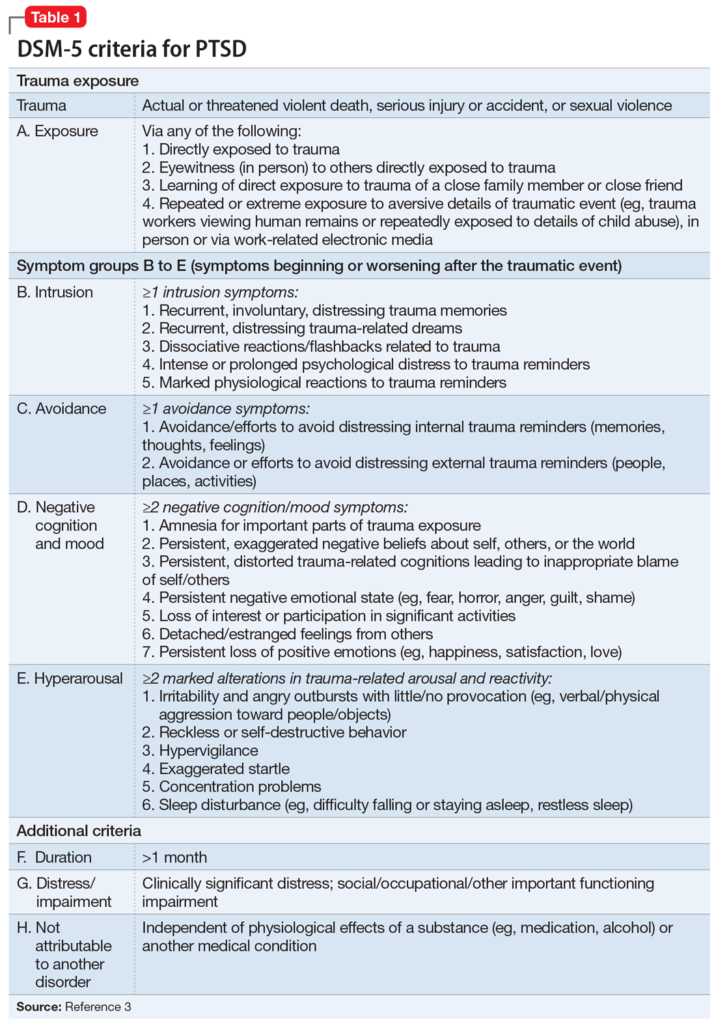

Acute Stress Disorder DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Code 308.3

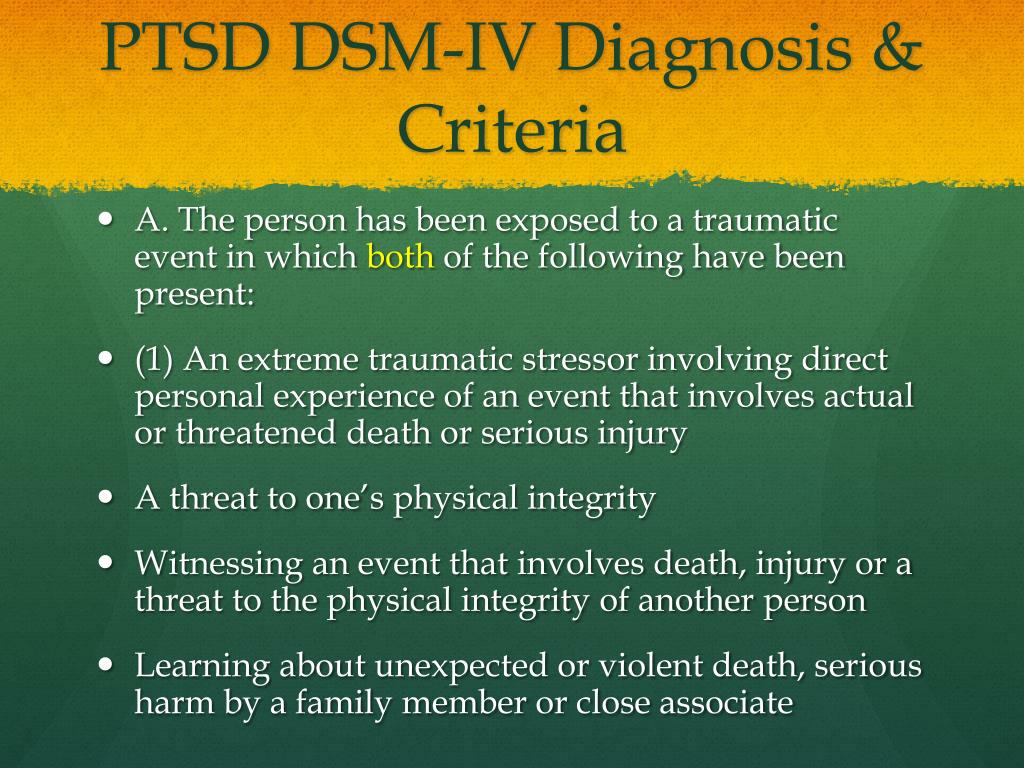

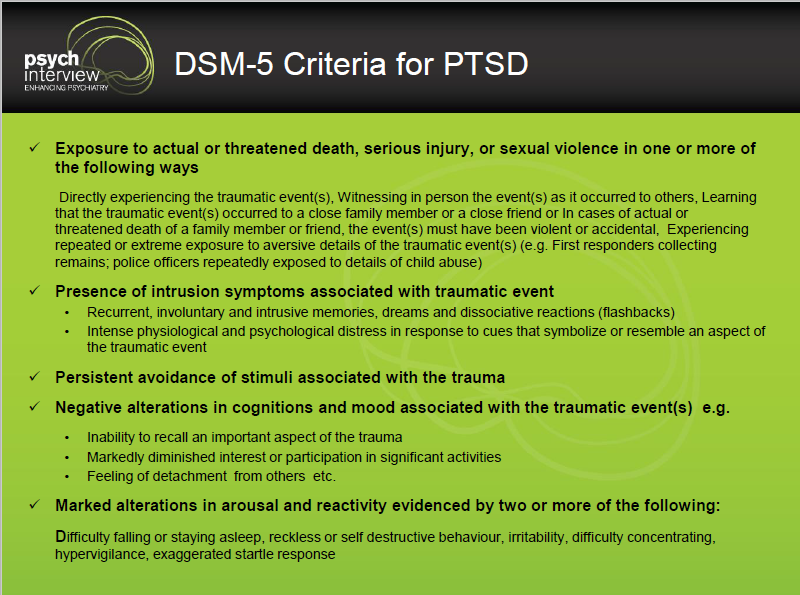

" A. Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violation in one (or more) of the following ways:

- Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s).

- Witnessing, in person, the events(s) as it occurred to others.

- Learning that the traumatic events(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend. Note: In cases of actual or threatened by death of a family member or friend, the events(s) must have been violent or accidental.

- Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) (e.g., first responders collecting human remains; police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse). Note: This does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies, or pictures unless this exposure is work related.

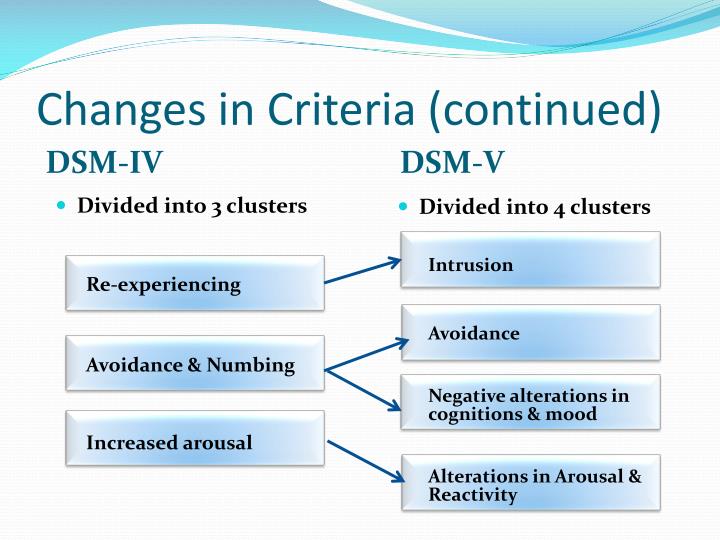

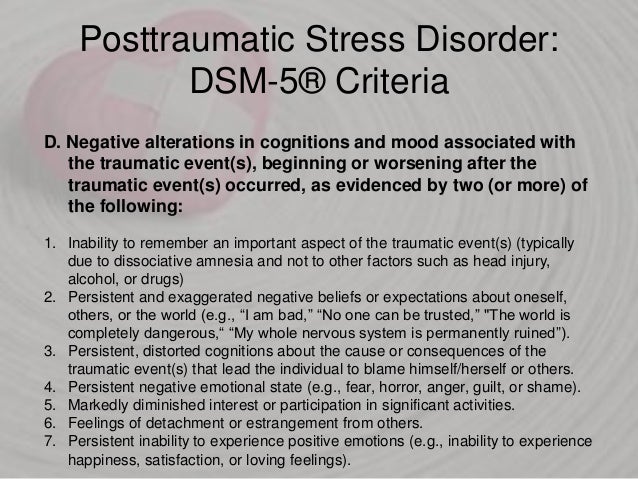

B. Presence of nine (or more) of the following symptoms from any of the five categories of intrusion, negative mood, dissociation, avoidance, and arousal, beginning or worsening after the traumatic event(s) occurred:

- Intrusion symptoms

- Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s). Note: In children, repetitive play may occur in which themes or aspects of the traumatic event(s) are expressed.

- Recurrent distressing dreams in which the content and/or affect of the dream are related to the events(s). Note: In children older than 6, there may be frightening dreams without recognizable content.

- Dissociative reactions (e.g., flashbacks) in which the individual feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring. (Such reactions may occur on a continuum, with the most extreme expression being a complete loss of awareness of present surroundings). Note: In children, trauma-specific reenactment may occur in play.

- Intense or prolonged psychological distress or marked physiological reactions in response to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic events.

- Negative Mood

- Persistent inability to experience positive emotions (e.g., inability to experience happiness, satisfaction, or loving feelings).

- Dissociative Symptoms

- An altered sense of the reality of one's surroundings or oneself (e.g., seeing oneself from another's perspective, being in a daze, time slowing.)

- Inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic events(s) (typically due to dissociative amnesia and not to other factors such as head injury, alcohol, or drugs).

- Avoidance symptoms

- Efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).

- Efforts to avoid external reminders (people, places, conversations, activities, objects, situations) that arouse distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s).

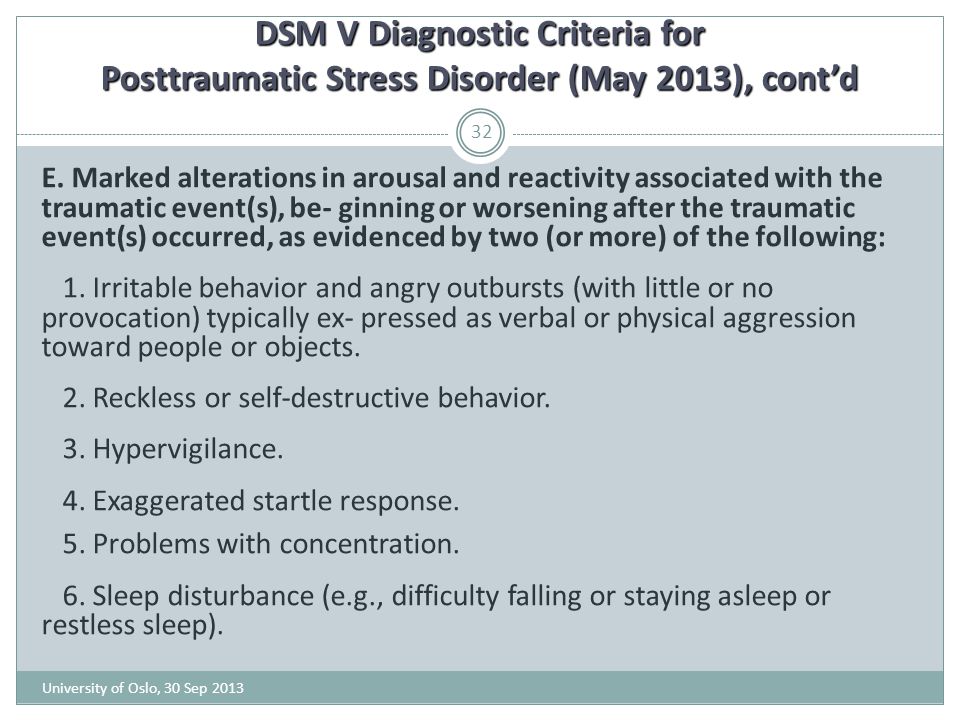

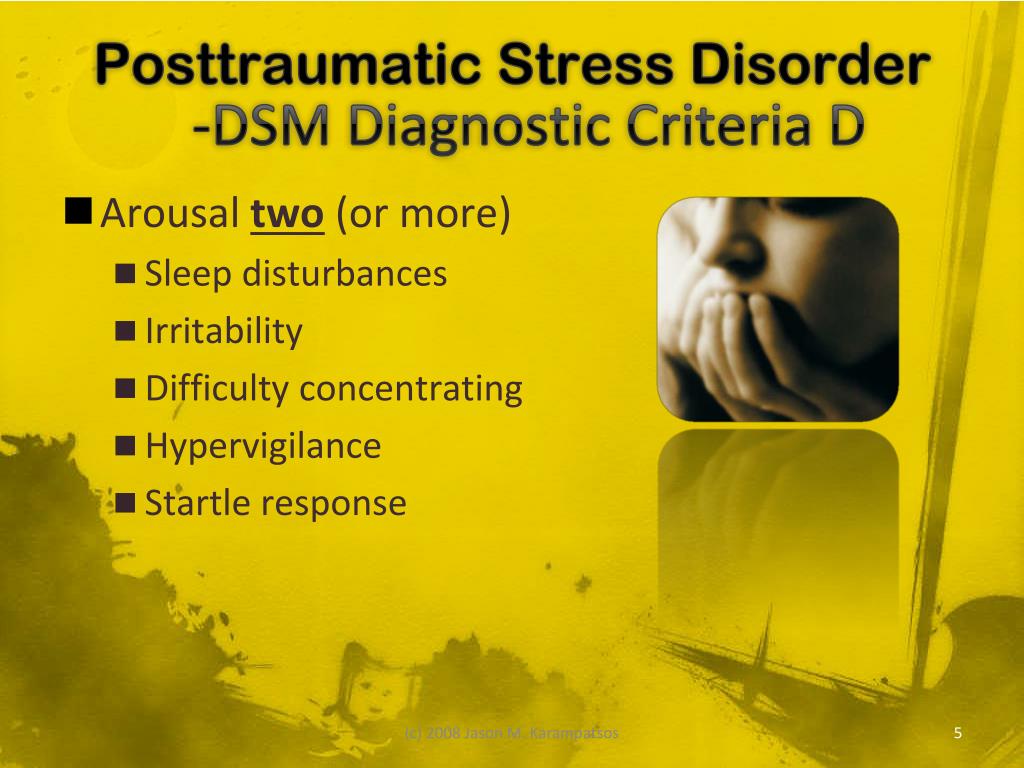

- Arousal symptoms

- Sleep disturbance (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep, restless sleep)

- Irritable behavior and angry outbursts (with little or no provocation) typically expressed as verbal or physical aggression toward people or objects.

- Hypervigilance

- Problems with concentration

- Exaggerated startle response

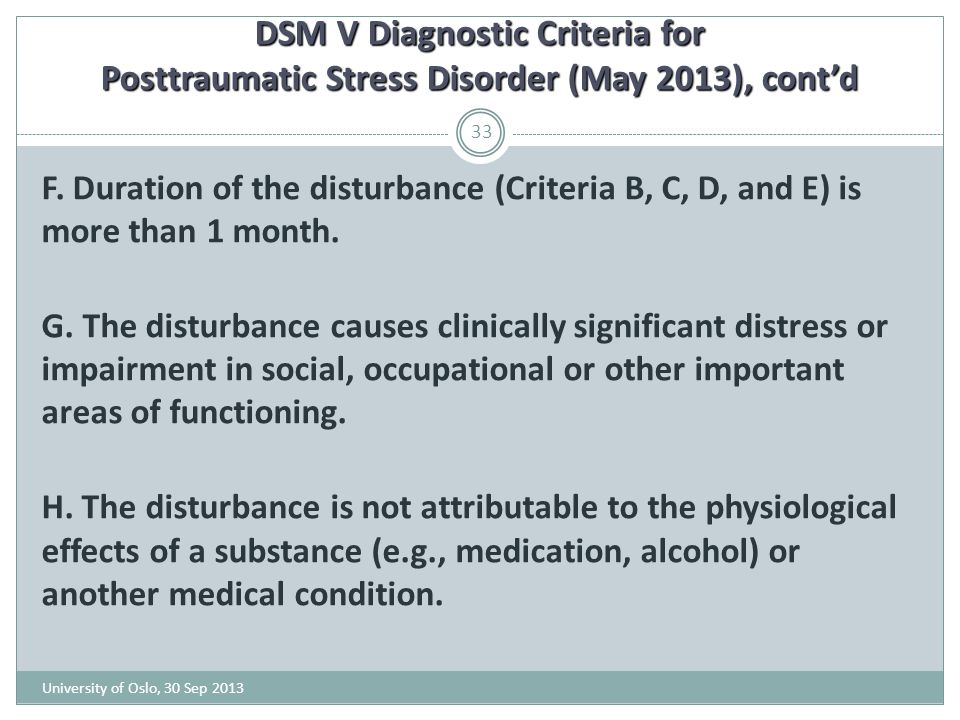

C. The duration of the disturbance (symptoms in Criterion B) is 3 days to 1 month after trauma exposure. Note: Symptoms typically begin immediately after the trauma, but persistence for at least 3 days and up to a month is needed to meet disorder criteria.

D. The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

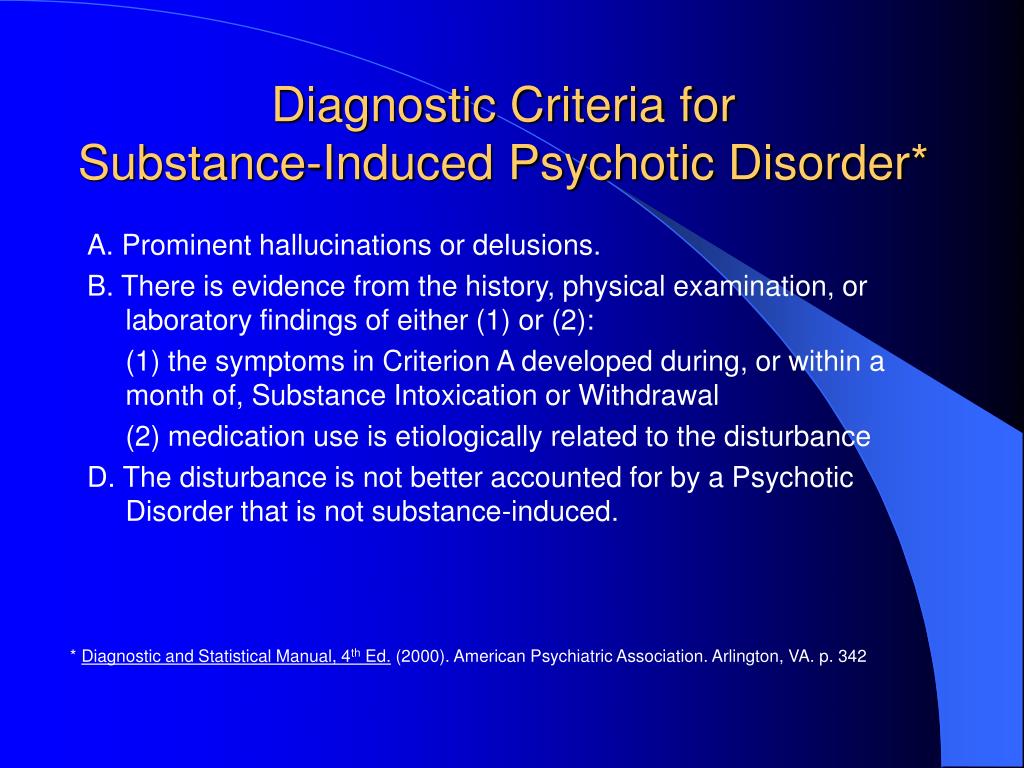

E. The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., medication or aocohol) or other medical condition (e.g., mild traumatic brain injury) and is not better explained by brief psychotic disorder. " [1]

" [1]

ICD Diagnostic Criteria

The most recent approved version of the International Classification of Diseases, the diagnostic guide published by the World Health Organization is the ICD-10, published in 1992.[2] The draft ICD-11 criteria for Acute Stress Disorder gives this description:

ICD 11 draft - Acute Stress Reaction

Code QA32.2

"Acute Stress Reaction refers to the development of transient emotional, cognitive and behavioural symptoms in response to an exceptional stressor such as an overwhelming traumatic experience involving serious threat to the security or physical integrity of the individual or of a loved person(s) (e.g. natural catastrophe, accident, battle, criminal assault, rape), or an unusually sudden and threatening change in the social position and/or network of the individual, such as the loss of one's family in a natural disaster. The symptoms are considered to be within the normal range of reactions given the extreme severity of the stressor. The symptoms usually appear within hours to days of the impact of the stressful stimulus or event, and typically begin to subside within a week after the event or following removal from the threatening situation." [4] Last updated November 2014.

The symptoms usually appear within hours to days of the impact of the stressful stimulus or event, and typically begin to subside within a week after the event or following removal from the threatening situation." [4] Last updated November 2014.

Alternative terms for Acute Stress Reaction include Acute: crisis reaction, Acute: reaction to stress, Psychic shock, Combat fatigue and Crisis state. [4]

ICD 10 Diagnostic Criteria

Code F43.0

Acute Stress Reaction

"A transient disorder that develops in an individual without any other apparent mental disorder in response to exceptional physical and mental stress and that usually subsides within hours or days. Individual vulnerability and coping capacity play a role in the occurrence and severity of acute stress reactions. The symptoms show a typically mixed and changing picture and include an initial state of "daze" with some constriction of the field of consciousness and narrowing of attention, inability to comprehend stimuli, and disorientation. This state may be followed either by further withdrawal from the surrounding situation (to the extent of a dissociative stupor - F44.2), or by agitation and over-activity (flight reaction or fugue). Autonomic signs of panic anxiety (tachycardia, sweating, flushing) are commonly present. The symptoms usually appear within minutes of the impact of the stressful stimulus or event, and disappear within two to three days (often within hours). Partial or complete amnesia (F44.0) for the episode may be present. If the symptoms persist, a change in diagnosis should be considered." [3]

This state may be followed either by further withdrawal from the surrounding situation (to the extent of a dissociative stupor - F44.2), or by agitation and over-activity (flight reaction or fugue). Autonomic signs of panic anxiety (tachycardia, sweating, flushing) are commonly present. The symptoms usually appear within minutes of the impact of the stressful stimulus or event, and disappear within two to three days (often within hours). Partial or complete amnesia (F44.0) for the episode may be present. If the symptoms persist, a change in diagnosis should be considered." [3]

Alternative terms for Acute Stress Reaction include Acute: crisis reaction, Acute: reaction to stress, Psychic shock, Combat fatigue and Crisis state. [4]

References

Acute Stress Disorder - PsychDB

Table of Contents

Acute Stress Disorder

Primer

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Specifiers

Signs and Symptoms

Screening and Rating Scales

Pathophysiology

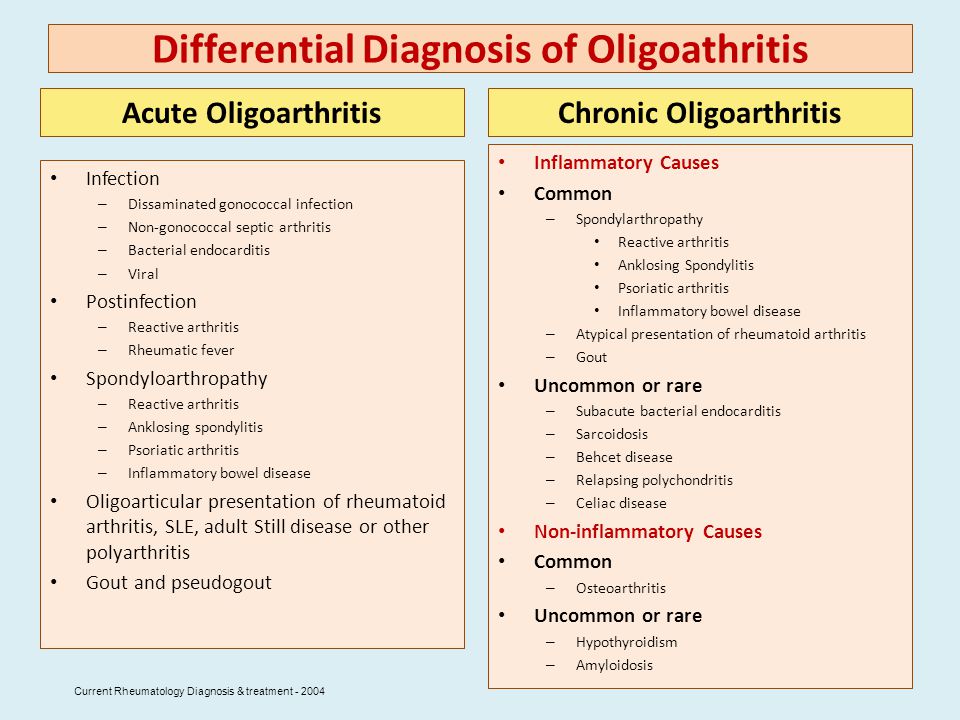

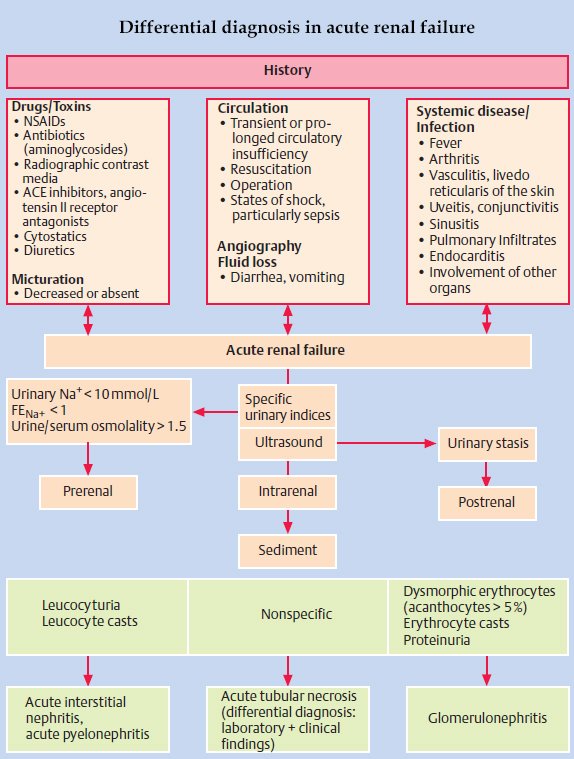

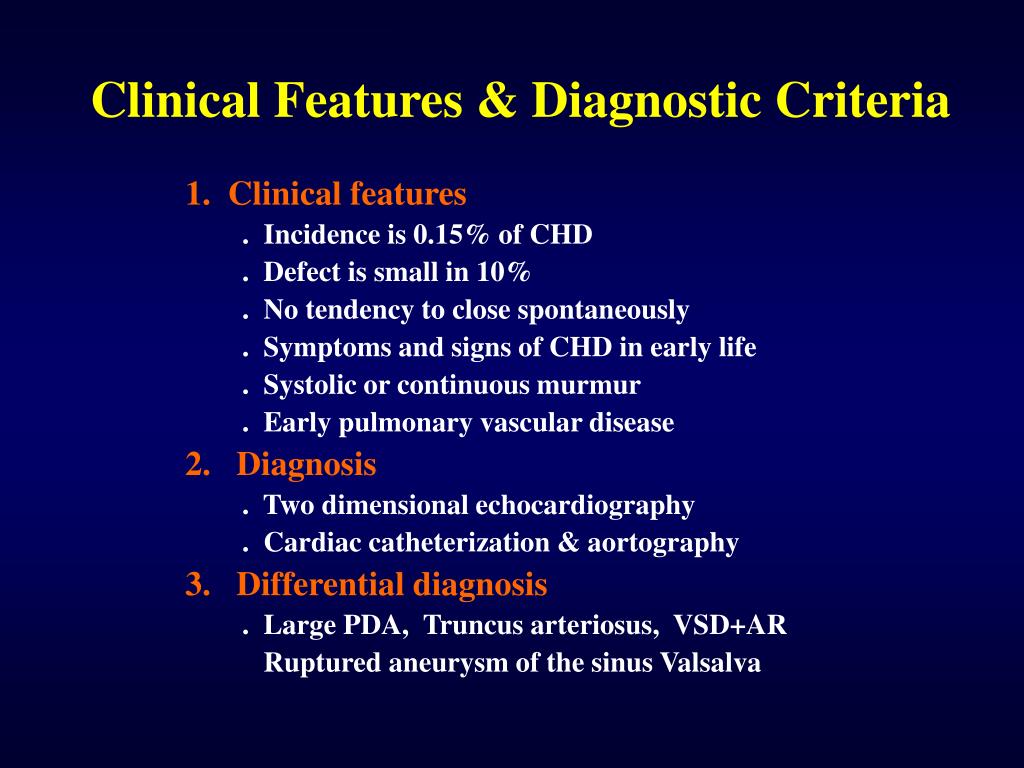

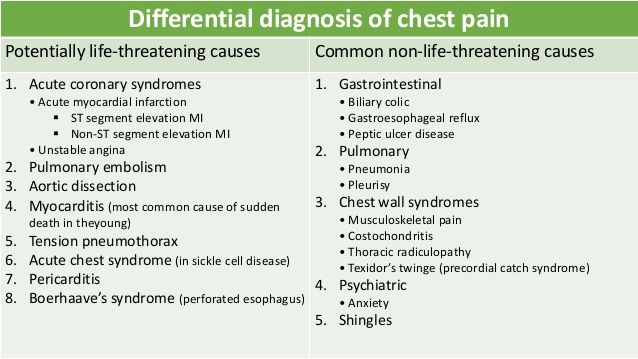

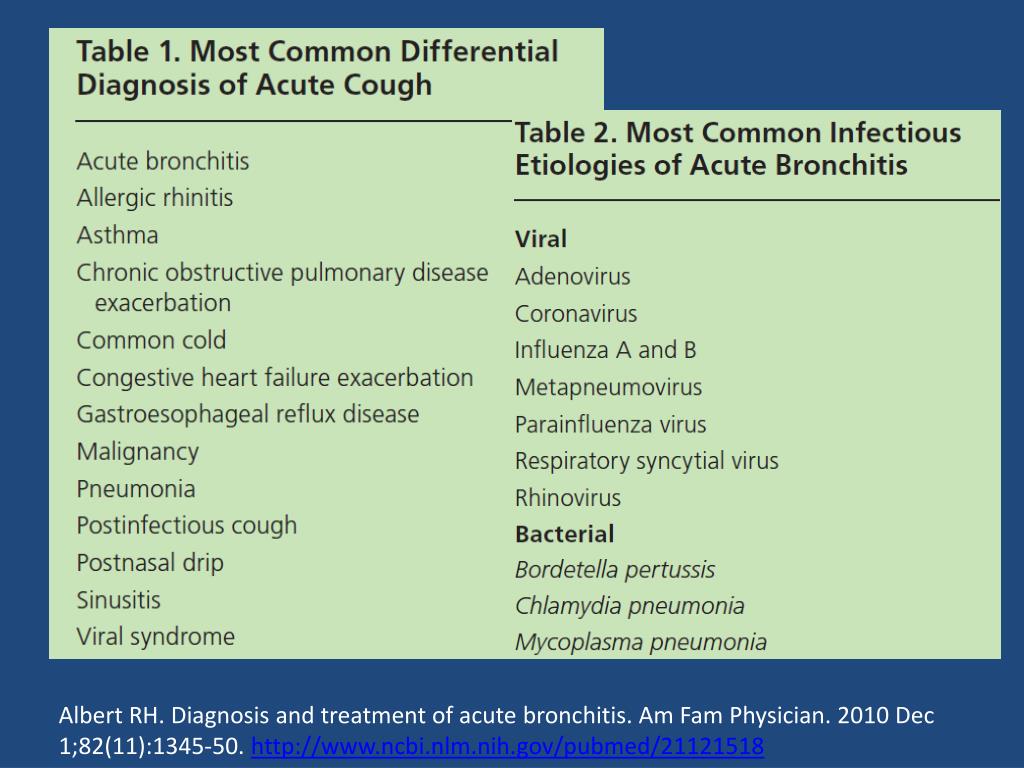

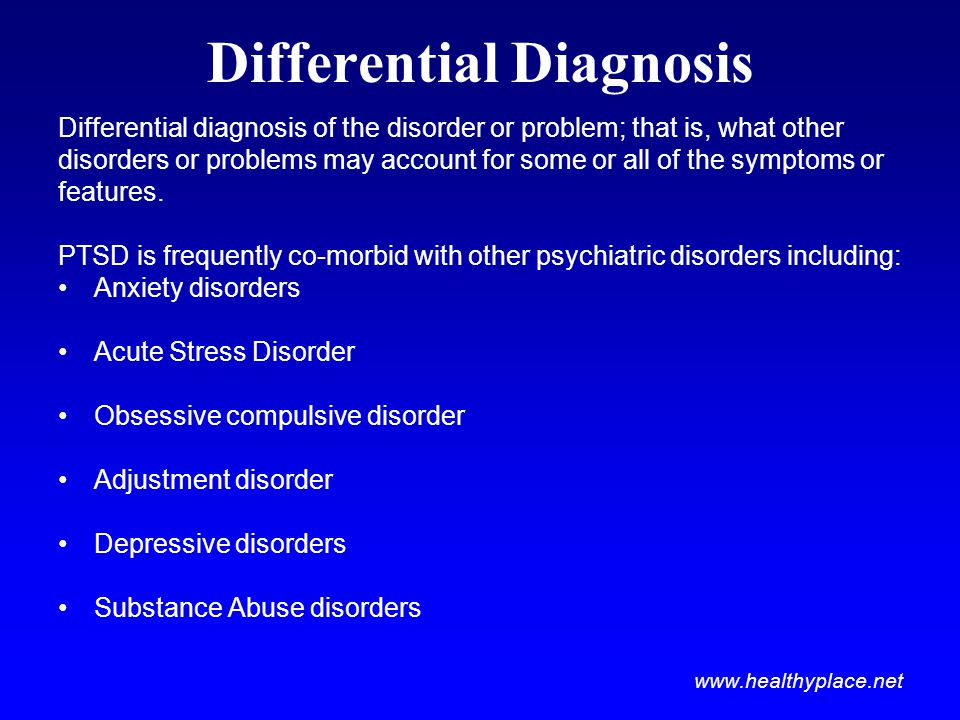

Differential Diagnosis

PTSD

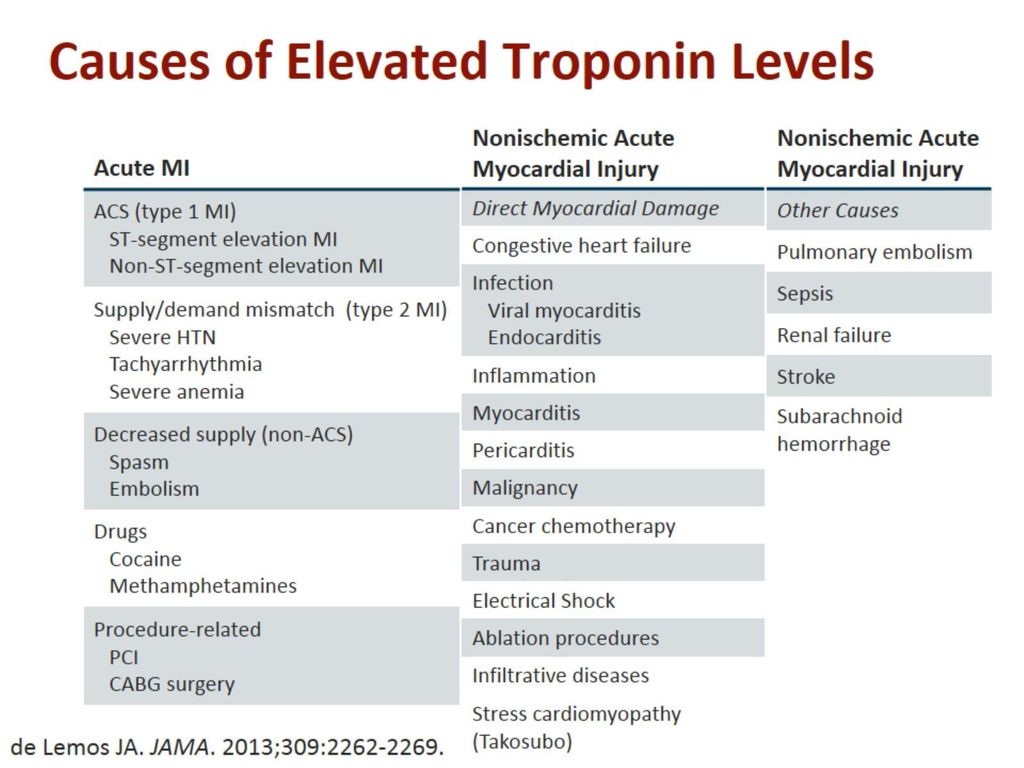

Investigations

Physical Exam

Treatment

Psychotherapy

Pharmacotherapy

Guidelines

Resources

Primer

Acute Stress Disorder (acute stress reaction, psychological shock) is a mental disorder that arises in response to experiencing or witnessing a traumatic event that induces a strong emotional response within the individual. Common traumas include combat/war in males, assault/rape in females, torture, natural disasters, and serious accidents. Acute stress disorder is a “precursor” diagnosis to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), as symptoms last less than 1 month.

Common traumas include combat/war in males, assault/rape in females, torture, natural disasters, and serious accidents. Acute stress disorder is a “precursor” diagnosis to Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), as symptoms last less than 1 month.

Epidemiology

Acute stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorders have a lifetime prevalence of 7%, and up to 30% in US Vietnam veterans.

Prognosis

Comorbidity

Risk Factors

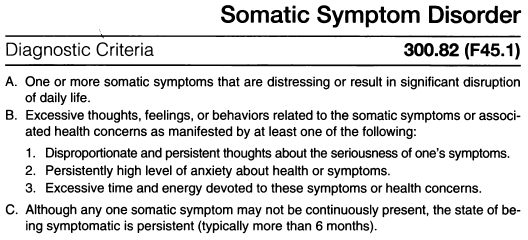

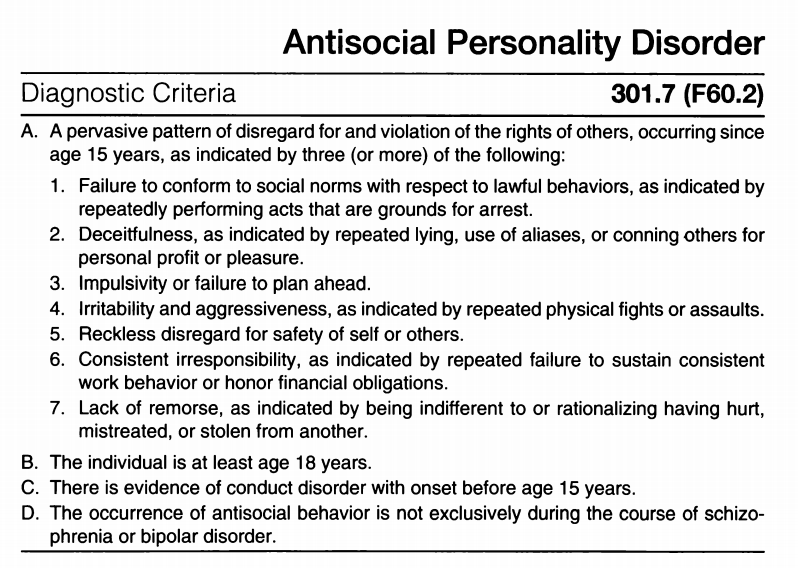

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria

Criterion A (Exposure)

Exposure to actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence in at least 1 of the following ways:

Directly experiencing the traumatic event(s).

Witnessing, in person, the event(s) as it occurred to others.

Learning that the traumatic event(s) occurred to a close family member or close friend. In cases of actual or threatened death of a family member or friend, the event(s) must have been violent or accidental.

Experiencing repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event(s) (e.g., first responders collecting human remains: police officers repeatedly exposed to details of child abuse).

Criterion B

Presence of at least 9 of the following symptoms from any of the five categories of (1) intrusion, (2) negative mood, (3) dissociation, (4) avoidance, and (5) arousal, beginning or worsening after the traumatic event(s) occurred:

1. Intrusion Symptoms

Recurrent, involuntary, and intrusive distressing memories of the traumatic event(s). In children older than 6 years, repetitive play may occur in which themes or aspects of the traumatic event(s) are expressed.

Recurrent distressing dreams in which the content and/or affect of the dream are related to the traumatic event(s). In children, there may be frightening dreams without recognizable content.

Dissociative reactions (flashbacks) in which the individual feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring. (Such reactions may occur on a continuum, with the most extreme expression being a complete loss of awareness of present surroundings.) In children, trauma-specific reenactment may occur in play.

Intense or prolonged psychological distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s)

2. Negative Mood

Persistent inability to experience positive emotions (e.g. - inability to experience happiness, satisfaction, or loving feelings)

3. Avoidance Symptoms

Efforts to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s)

Efforts to avoid external reminders (people, places, conversations, activities, objects, situations) that arouse distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings about or closely associated with the traumatic event(s)

4.

Arousal Symptoms

Arousal SymptomsSleep disturbance (e.g., difficulty falling or staying asleep, restless sleep)

Irritable behaviour and angry outbursts (with little or no provocation), typically expressed as verbal or physical aggression toward people or objects

Hypervigilance

Problems with concentration

Exaggerated startle response

5. Dissociative Symptoms

An altered sense of the reality of one’s surroundings or oneself (e.g. - seeing oneself from another’s perspective, being in a daze, time slowing)

Inability to remember an important aspect of the traumatic event(s) (typically due to dissociative amnesia and not to other factors such as head injury, alcohol, or drugs)

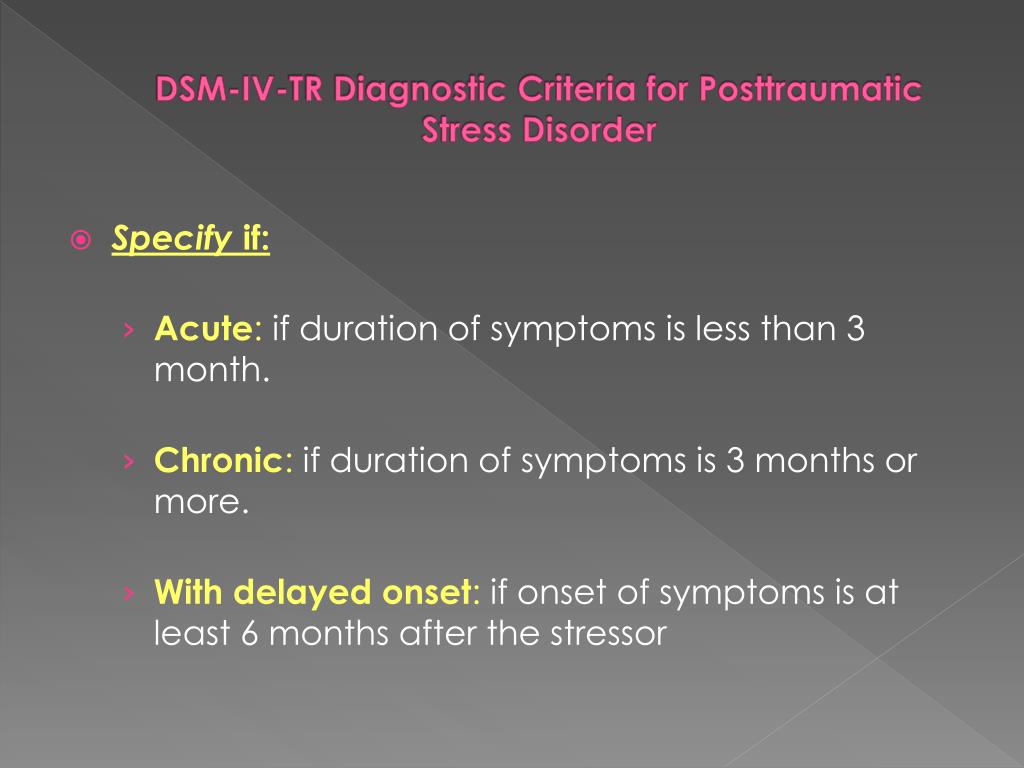

Criterion C

Duration of the disturbance (symptoms in Criterion B) is 3 days to 1month after trauma exposure.

Note: Symptoms typically begin immediately after the trauma, but persistence for at least 3 days and up to a month is needed to meet disorder criteria.

Criterion D

The disturbance causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning.

Criterion E

The disturbance is not attributable to the physiological effects of a substance (e.g., medication or alcohol) or another medical condition (e.g., mild traumatic brain injury) and is not better explained by brief psychotic disorder.

Specifiers

Episode Specifier

Severity Specifier

Specify if:

Signs and Symptoms

Screening and Rating Scales

Pathophysiology

Differential Diagnosis

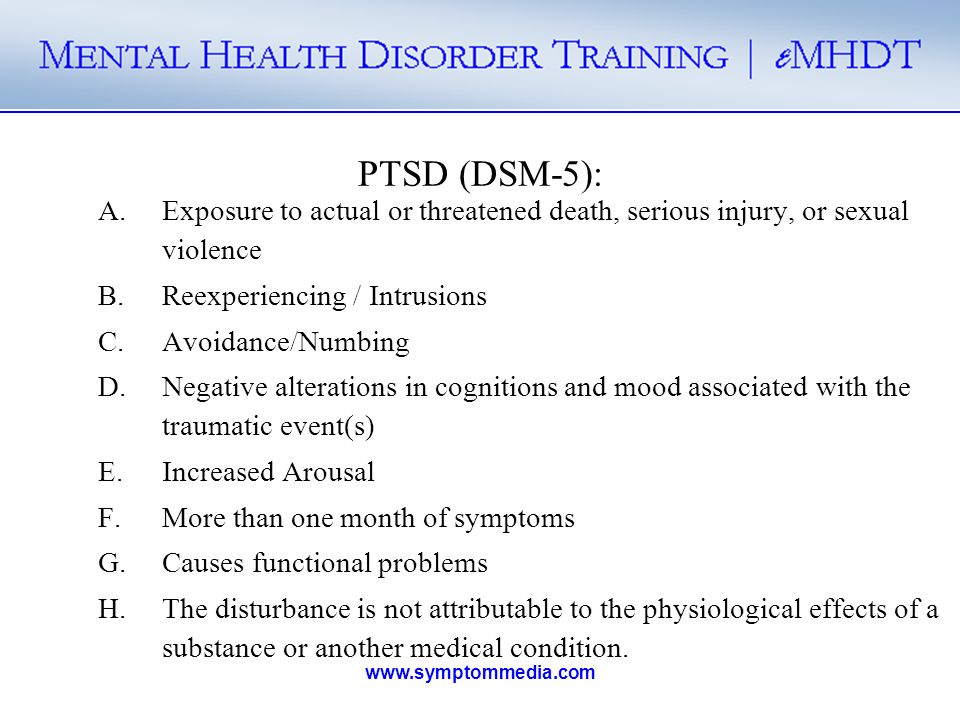

PTSD

PTSD can develop after ASD, but it can also also develop even if ASD does noccur. PTSD can only be diagnosed if the symptoms have lasted longer than 1 month.

Investigations

Physical Exam

Treatment

Psychotherapy

Pharmacotherapy

Guidelines

See also: Psychiatry Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs)

Resources

For Patients

For Providers

Articles

Research

References

1)Reisman, M. (2016). PTSD Treatment for Veterans: What’s Working, What’s New, and What’s Next. Pharmacy and Therapeutics, 41(10), 623.

ᐈ PTSD Diagnosis ~【Post Traumatic Stress Disorder】

Post-traumatic stress disorder, or PTSD, is a severe mental condition that progresses as a result of a single or recurring event that has a negative impact on a person's mental health. Symptoms of PTSD can appear immediately or several months after the injury.

The likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress disorder is the same for patients of different age groups. The main risk factor is the severity of the injury, the initial state of the psyche, psychological and biological predisposition.

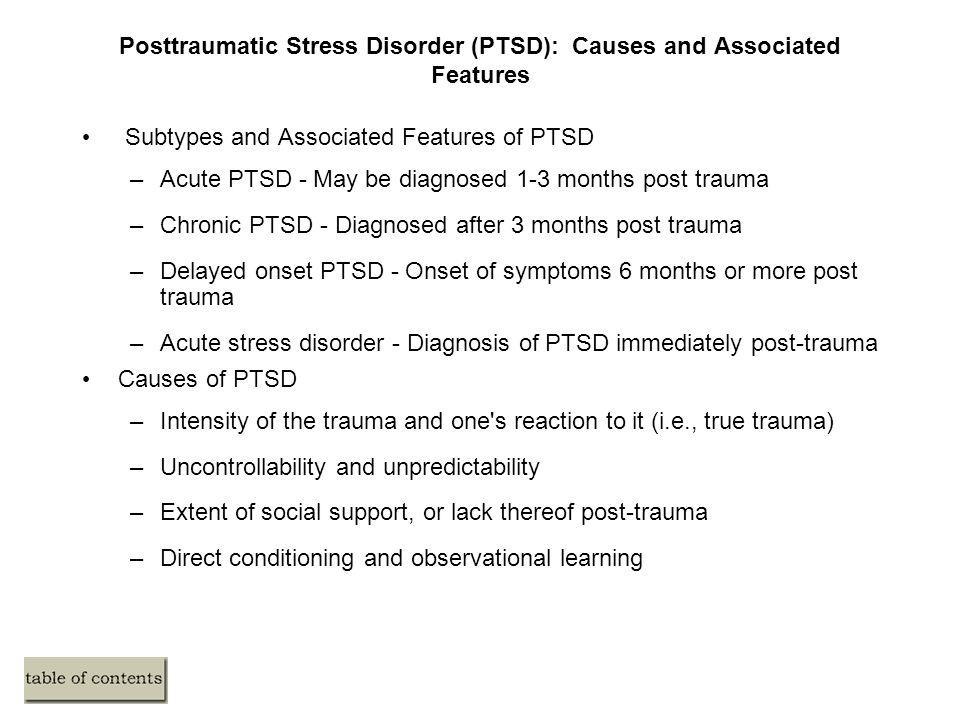

Classification

In the modern classification, 4 types of post-traumatic syndrome are distinguished:

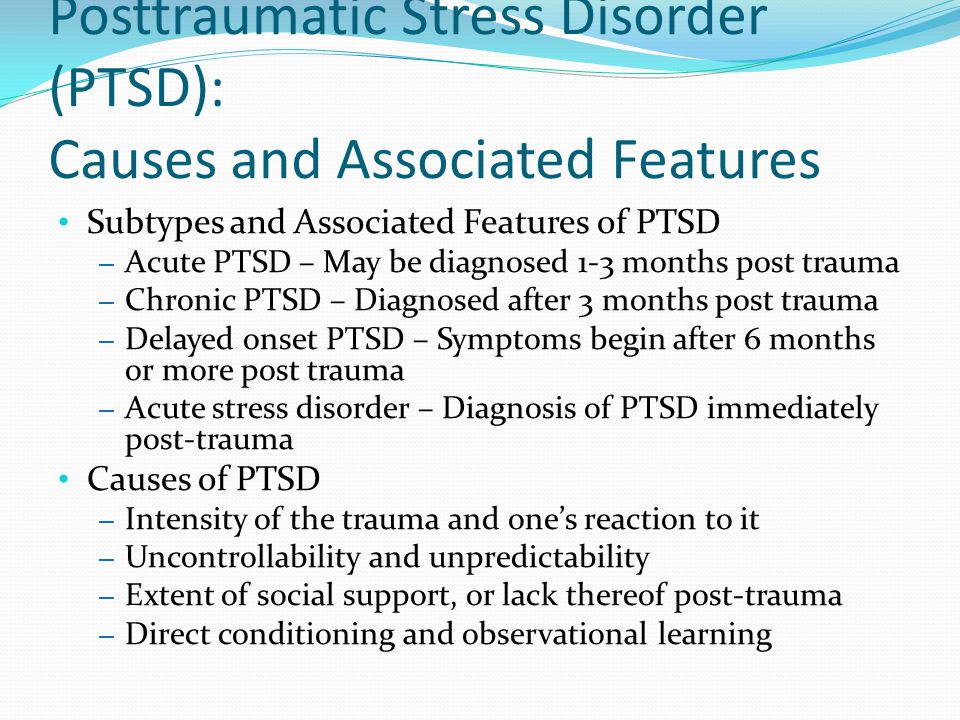

Acute.

Appears in the first days after a stressful situation. Symptoms appear very brightly within 2-3 months.

Chronic.

Characterized by a gradual increase in signs of pathology, exhaustion of the nervous system, changes in character and interests.

Deformation.

Manifested in patients with a long-term chronic mental disorder. Progress leads to the formation of phobias, neuroses, feelings of anxiety.

Delayed.

The clinical picture becomes apparent 3-6 months after the injury. Various external stimuli can provoke the progress of PTSD.

There are also 3 stages of PTSD: acute, chronic and delayed.

In the first case, this is the period of the beginning of an extreme situation. The state is saved until it ends. Characterized by excessive anxiety for one's own life, lethargy, confusion.

A chronic condition occurs after the trigger has been removed if the patient feels restless. It is possible that the clouding of the mind persists, the person does not understand what happened. Often there are changes in speech and motor functions.

In some cases, with PTSD, the stages of such a plan are not observed, a delayed form appears, that is, the characteristic symptoms appear after a few months, and before that the patient feels normal.

This medical problem also varies in severity. With a mild course of post-traumatic syndrome, the patient's state of health remains unchanged, the ability to work professionally and the ability to communicate with other individuals is preserved. With a severe degree of damage, chronic mental disorders are diagnosed, schizophrenia is possible. With prolonged progress, PTSD leads to malfunctions of the brain, affects the functioning of the endocrine and nervous systems.

Post-traumatic syndromes are characterized by diverse signs, depending on which the division into clinical types is provided: When detecting post-traumatic stress disorder, the main task of a specialist is to correctly differentiate the diagnosis by establishing the type and type. The main factor provoking post-traumatic stress disorder is a tragic event, a traumatic situation. A psychologically healthy person can face PTSD, but the course of the disease will be easier for him than for a person with a shaken psyche. In all cases, the syndrome has an undulating course, often leading to a permanent change in personality. The list of PTSD symptoms includes the following changes: According to statistics, the disease in children is detected no more often than in adults, but experts in the field of psychotherapy assure that the disorder in children progresses faster. Children are a risk group due to an increased predisposition to post-traumatic stress syndrome, impressionability and sensitivity. Pathology is diagnosed by a child psychiatrist. The doctor determines what traumatic event occurred and what changes in the nervous system it provoked. During the diagnosis, the patient's reaction to the impact of stimuli is assessed, the presence of memories reproduced in a dream, during a game or in stories is clarified. A consultation with a child psychologist will allow you to establish the type of disorder, determine the scheme of influence and establish a prognosis for recovery. Treatment of PTSD in children is a long-term work with a child psychologist or psychotherapist. Complex therapy requires the combined use of several techniques. The patient is shown cognitive-behavioral correction, psychotherapy and drug treatment aimed at stabilizing the work of the central nervous system. The diagnosis of PTSD should not be ignored. Post-traumatic stress disorder is established on the basis of the patient's complaints about psychological trauma, tragic events in the past. Diagnosis of PTSD is provided with the help of special questionnaires confirming the presence of criteria similar to the disease. Self-testing for PTSD is not always accurate because some factors may be hidden. Often the psychiatrist recommends an additional consultation in the presence of relatives or people from close circle. This allows you to differentiate the diagnosis and exclude the presence of other, symptomatically similar diseases. The treatment of PTSD is determined individually, taking into account the characteristics of the patient, the type of pathology and the presence or absence of concomitant disorders. The most effective are cognitive behavioral therapy and hypnotherapy. According to the indications, psychotherapy is combined with medication. Treatment of PTSD often requires the use of adrenergic blockers, antidepressants, tranquilizers, neuroleptics. As auxiliary methods, therapeutic massage is used. A rehabilitation doctor or psychotherapist can help prevent the development of serious problems. The main task is to start the impact immediately after the injury, to work out the event in a quality manner in order to prevent the problem from becoming chronic. Also, to prevent the development of post-traumatic stress disorder will help: The doctor should explain to the patient that an acute reaction to stress is normal for the human body. Another prevention of PTSD is to avoid possible stress and maintain mental balance. The article is for informational purposes only. Please remember: self-medication can harm your health. The author of the article: Kulik Maria Sergeevna Doctor-psychologist of the second category If a problem is found, the patient should consult a psychiatrist. If signs of PTSD are found in a child, consultation with a child psychiatrist or psychologist is necessary. The consequences of PTSD can be irreversible, so it is very important to undergo a full examination, determine the type of pathology, establish the cause and work out a treatment regimen. Specialists of the MEDICOM clinic working with the latest techniques will help you to undergo high-quality diagnostics and treatment of PTSD in Kyiv. You can seek help and take a test for PTSD at the clinic's subdivisions located in Obolon and Pechersk. Mental health requires careful attention, so it is better to turn to professionals! all specialists

The main causes of PTSD

Causes of PTSD include:

There is a reassessment of one's own ideals, one's importance in life, a change in old ideas.

There is a reassessment of one's own ideals, one's importance in life, a change in old ideas. Clinical symptoms of PTSD

PTSD in children: features

The reasons for the development of the problem in children are psychological trauma, unfavorable social conditions and individual developmental characteristics.

The reasons for the development of the problem in children are psychological trauma, unfavorable social conditions and individual developmental characteristics. Complications

Over time, the problem can worsen and lead to irreversible complications. Only acute disorders can be corrected, after the transition to a chronic form, therapy is complicated, a pathological change in personality is observed. A person manifests pronounced narcissistic qualities, the development of alcoholism and drug addiction is not excluded. Together, these factors are unfavorable signs, and therefore aggravate the prognosis for recovery.

Over time, the problem can worsen and lead to irreversible complications. Only acute disorders can be corrected, after the transition to a chronic form, therapy is complicated, a pathological change in personality is observed. A person manifests pronounced narcissistic qualities, the development of alcoholism and drug addiction is not excluded. Together, these factors are unfavorable signs, and therefore aggravate the prognosis for recovery. Diagnostics

Treatment

Prevention of PTSD

Sources

Which doctor treats PTSD?

Certificates

Reviews

10/23/2021 18:14

Alexander

To the author. Definitely, PTSD is really serious. Skoda, which doctors know, do not outperform neither sick nor relatives. I broke my ankle for 3 years: 4 operations, then 3 fates in the police, fear that I would become disabled, depression, and the pressure of my relatives simply made me crazy. I don’t show how self-tapping can come in. Obov'yazkovo idit to the psychologist.

11.09.2021 20:40

Galina Andriivna Sinyavska

She licked on the wet bed near the kitchen. I had a compression fracture of the ridge, I wanted to die. I had to visit a psychologist. Without її help, I would not have run into it. The psychologist gave a reason to overcome fears and come to the solution of the problem.

I had a compression fracture of the ridge, I wanted to die. I had to visit a psychologist. Without її help, I would not have run into it. The psychologist gave a reason to overcome fears and come to the solution of the problem.

07/30/2021 10:47

Valentina

Thank you majesty, that important article was written with grace. I learned a lot of new things. At once, I’ll lie on the knight with a fracture, I’ll be respectful to the new. I would not have thought before that about the mental state of a person after a serious injury, you also need to be turbulent.

15.06.2021 18:26

Vitaly

Thank you for the information and help. Kulik Maria Sergeevna is a very good specialist. So far, we have come to the consultation without the child, in order to reconnoiter the situation, so to speak. The doctor was very friendly, asked a lot of questions, then gave recommendations on how to behave with our son after being beaten by classmates at school. He is very closed, and we are slowly slipping into despair. Now the only hope is for Maria Sergeevna.

Now the only hope is for Maria Sergeevna.

05/22/2021 11:55

Olga

I thank Kulik Mariya Sergievna for help. We have fired houses, it became late at night. Thank you to relatives from Kiev, who gave them a seat. Alesina became unrecognizable. The axis of infection from Sergiyk seems to be a psychologist, who at night finds uncontrollable panic on him, and it is unrealistic to calm down. Already after the third session, I remembered the progress.

05/01/2021 12:21

Mikhailo Valentinovich

Thank you for the information. Children are especially susceptible to mental trauma at a time. Recently, my team died of cancer, I can’t know the language of the child, although earlier we were closer. At the nearest future, I will turn to her for help to a psychologist.

04/11/2021 13:32

Leonid

I like a good article and service, I often look in when something hurts for information on symptoms and diseases. But I'm interested in PTSD. How did we experience stress in our childhood without psychologists and corrective methods? Like normal grew.

12/16/2020 18:16

Grigory Titov

Very good service, they cover a lot of relevant topics, and most importantly, they immediately write which specialist you can contact for help. We went to MEDIKOM to Maria Sergeevna, a cool psychologist. The child stuttered and was very complex about this. But with the joint efforts of a speech therapist and a psychologist, the situation was corrected. Nikita is now studying, and successfully, in the 8th grade. He became very cheerful and sociable.

Show 3 more

Total 8 reviews

leave feedback

variant of the dynamics of post-traumatic stress disorder

Combat stress and organic brain damage: a variant of the dynamics of post-traumatic stress disorderSukiasyan S.G.

Medical rehabilitation center "Artmed";

Armenian Medical Institute

Tadevosyan M. Ya.

Ya.

Medical rehabilitation center "Artmed";

Armenian Medical Institute

Combat stress and organic brain damage: a variant of the dynamics of post-traumatic stress disorder

Journal: Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2020;120(9): 19‑27

DOI 10.17116/jnevro202012009119

How to quote

Sukiasyan S.G., Tadevosyan M.Ya. Combat stress and organic brain damage: a variant of the dynamics of post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. 2020;120(9):19-27.

Sukiasyan SG, Tadevosyan MYa. Combat stress and organic brain injury: type of the dynamics of posttraumatic stress disorder. Zhurnal Nevrologii i Psikhiatrii imeni S.S. Korsakova. 2020;120(9):19‑27. (In Russ.).

https://doi.org/10.17116/jnevro202012009119

Authors:

Sukiasyan S.G.

Medical Rehabilitation Center "Artmed";

Armenian Medical Institute

All authors (2)

Read metadata

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

To study the role of traumatic brain injury (TBI) in the development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in combat veterans.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

87 combat veterans were examined. The follow-up period ranged from 15 to 18 years. The diagnosis of mental illness was carried out on the basis of the ICD-10 diagnostic criteria. According to the diagnoses, two groups of patients were formed: with the presence of PTSD (main group) and with organic brain damage with reduced symptoms of PTSD (comparison group). Along with the psychopathological research method, a set of scales and questionnaires were used, including those adapted to study the effects of combat trauma.

RESULTS AND CONCLUSION

The identified clinical manifestations of the studied groups of patients in the post-traumatic period indicate the similarity and homogeneity of post-traumatic disorders in both groups. In the future, the pathogenetic role of the intensity of TBI becomes more clear, which, depending on the severity, leads to the formation of an organic brain lesion or performs only a pathoplastic role, giving some features to the clinical picture of PTSD. It has been established that the more severe the injury, the more likely it is that PTSD will transform into an organic brain lesion. It is emphasized that the treatment of post-stress disorders is a continuous, long-term, complex and step-by-step process that includes pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and psychosocial interventions.

It has been established that the more severe the injury, the more likely it is that PTSD will transform into an organic brain lesion. It is emphasized that the treatment of post-stress disorders is a continuous, long-term, complex and step-by-step process that includes pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, and psychosocial interventions.

Key words:

post-traumatic stress disorder

somatization of mental processes

exogenous organic disorders

craniocerebral injury

Authors:

Sukiasyan S.G.

Medical rehabilitation center "Artmed";

Armenian Medical Institute

Tadevosyan M.Ya.

Medical rehabilitation center "Artmed";

Armenian Medical Institute

References:

- Sukiasyan S.G., Tadevosyan M.Ya. Post-traumatic stress disorder: from functional to organic. Psychiatry. 2011;1:59-69.

- Petrakov B.D. The main patterns of the prevalence of mental illness in the modern world and in the Russian Federation.

Materials of the XII Congress of Psychiatrists of Russia. M., 1995;98-99.

Materials of the XII Congress of Psychiatrists of Russia. M., 1995;98-99. - Boyko A.N., Batysheva T.T., Kostenko E.V., Zaitsev K.A. Traumatic brain injury. Neurology. M, 2007;5-11.

- Kachkov I.A., Filimonov B.A. Minor brain injury. Russian medical journal. 1997;5:8:483-488.

- Volykova M.A., Kokorina N.P. Psychosomatic disorders in military personnel who served in local wars: Problems of providing medical, social and psychological support to the population in emergency situations. Materials of the scientific-practical conference. Kemerovo: Publishing House "Medicine and Education", 2004; 6-7.

- Falger PRJ, Op den Velde W, Hovens JE, Schouten EGW, De Groen JHM, Van Duijn H. Current posttraumatic stress disorder and cardiovascular disease risk factors in Dutch Resistance veterans from World War II. Psychother. Psychosom. 1992;57:4:164-171. https://doi.org/10.1159/000288594

- Voloshin V.M. Typology of chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal.

neurol, and psychiatrist. 2004;104:1:17-23.

neurol, and psychiatrist. 2004;104:1:17-23. - Gill J, Vythilingam M, Page GG. High DHEA, and High Levels of Stimulated TNF-α, and IL-6 in Women With PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2008;21:6:530-539. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.20372

- Spitzer C, Barnow S, Völzke H, Wallaschofski H, Freyberger HJ, John U, Bernd L, Löwe B, Grabe HJ. Association of posttraumatic stress disorder with low-grade elevation of C-reactive protein: evidence from the general population. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44(1):15-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2009.06.002

- Wessa M, Rohleder N. Endocrine and inflammatory alterations in post-traumatic stress disorder. Expert Review of Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2007;2:1:91-122. https://doi.org/10.1586/17446651.2.1.91

- Romodanov A.P., Pedachenko G.A., Pedachenko E.G., Polishchuk N.E. Traumatic brain injury and general somatic pathology. K .: Health, 1992; 152.

- Pogodina T.G. The structure of post-traumatic neuropsychiatric disorders in participants in local armed conflicts.

Neurological Bulletin. 2004;36:1-2:16-20.

Neurological Bulletin. 2004;36:1-2:16-20. - Berg GE, Watson CG, Nugent B, Gearhart LP, Juba M, Anderson D. A comparison of combat's effects on PTSD scores in veterans with high and low moral development. J. Clin. Psychol. 1994;50:5:669-676. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199409)50:5<669::aid-jclp2270500502>3.0.co;2-o "> 3.0.co;2-o" target="_blank"> https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199409)50:5<669::aid-jclp2270500502>3.0.co;2-o

- Bryant RA. Disentangling Mild Traumatic Brain Injury and Stress Reactions. NEJM. 2008;358(5):525-527. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMe078235

- Kennedy JE, Jaffee MS, Leskin GA, Jan E, Stokes JW, Lea FO, Fitzpatrick PJ. Posttraumatic stress disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder-like symptoms and mild traumatic brain injury. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44(7):895-920. https://doi.org/10.1682/JRRD.2006.12.0166

- Breuer J, Freud S. Studies on hysteria. Harmondsworth: Penguin books. 1978;425.

- Sukiasyan S.G., Manasyan N.

G., Chshmarityan S.S. Babakhanyan A.A., Kirakosyan A.L. Somatoform dynamics of post-traumatic stress disorders in combatants. Russian psychiatric journal. 2006;3:78-85.

G., Chshmarityan S.S. Babakhanyan A.A., Kirakosyan A.L. Somatoform dynamics of post-traumatic stress disorders in combatants. Russian psychiatric journal. 2006;3:78-85. - Alexander F. Psychosomatic medicine. New York: Norton and Co, 1987;300.

- Ginzburg K, Solomon Z. Trajectories of stress reaction and somatization among war veterans: a 20-year longitudinal study. Psychol Med. 2011;41(2):352-436. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710000528

- Marilov V.V. The transition of a functional disorder to organic psychosomatosis. Journal. nevrol. and psychiatrist. 2006;1:21-23.

- Sukiasyan S.G. On some aspects of the dynamics of post-traumatic stress disorders in combatants. Social and clinical psychiatry. 2009;19:1:12-18. Date of access: 24.02.2019. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/o-nekotoryh-aspektah-dinamiki-posttravmaticheskih-stressovyh-rasstroystv-u-uchastnikov-boevyh-deystviy

- Wayne A.M. Cerebral-vegetative shifts in somatic diseases of a neurogenic nature.

In: Disorders of the nervous system and mental activity in somatic diseases. M., 1979; 80-82.

In: Disorders of the nervous system and mental activity in somatic diseases. M., 1979; 80-82. - Weiner H. What the future holds for psychosomatic medicine. Psychother Psychosom. 1984;42(1-4):15-25. https://doi.org/10.1159/000287820

- Zatzick DF, Kang SM, Müller HG, Russo JE, Rivara FP, Katon W, Jurkovich GJ, Roy-Byrne P. Predicting posttraumatic distress in hospitalized trauma survivors with acute injuries. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(6):941-946. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.159.6.941

- Bryant RA. Posttraumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury: can they co-exist? Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2001;21:931-945. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(00)00074-X

- Meares S, Shores EA, Taylor AJ, Batchelor J, Bryant RA, Baguley IJ, Chapman J, Gurka J, Dawson K, Capon L , Marosszeky JE. Mild traumatic brain injury does not predict acute postconcussion syndrome. J. Neurol. neurosurgery. Psychiatry. 2008;79:300-306. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.2007.126565

- Hoge CW, McGurk D, Thomas JL, Anthony L, Cox AL, Engel ChC, Castro CA.

Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(5):453-463. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa072972

Mild traumatic brain injury in U.S. Soldiers returning from Iraq. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(5):453-463. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa072972 - Sukiasyan S.G., Tadevosyan M.Ya. The ratio of post-traumatic stress and exogenous organic mental disorders. Journal. nevrol. i Psychiatr., 2010;110:11:63-70.

- Korchagina E.V. Consequences of a combat craniocerebral injury and disability in former servicemen of working age in modern conditions: Abstract of the thesis. dis... cand. honey. Sciences. St. Petersburg, 2008;25.

- Shalev AY, Freedman S, Peri T, Brandes D, Sahar T, Orr SP, Pitman RK. Prospective study of posttraumatic stress disorder and depression following trauma. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(5):630-637. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.5.630

- Zhislin S.G. Essays on clinical psychiatry. 2nd ed. M.: Medicine, 1965; 320.

- Ushakov G.K. Borderline neuropsychiatric disorders: 2nd ed., Revised. and additional M.: Medicine. 1987;304.

- Gill JM, Saligan L, Woods S, Page G.

PTSD is associated with an excess of inflammatory immune activities. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2009;45(4):262-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2009.00229.x

PTSD is associated with an excess of inflammatory immune activities. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care. 2009;45(4):262-277. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6163.2009.00229.x - Rademaker AR, Kleber RJ, Geuze E, Vermetten E. Personality dimensions harm avoidance and self-directedness predict the cortisol awakening response in military men. Biol Psychol. 2009;81(3):177-183. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2009.04.002

- Kovalev V.V. Psychiatry of childhood. M.: Medicine, 1979; 607.

- Osetrov A.S. To the characteristics of the psycho-vegetative syndrome in the consequences of a closed TBI. Journal. neuropatol. and psychiatrist. 1995;6:7-9.

- Piven B.N. Exogenous organic diseases of the brain. M.: Medicine, 1998; 136.

- Shternberg E.Ya. Gerontological psychiatry. M.: Medicine, 1977; 216.

- Hibbard MR, Uysal S, Kepler K, Bogdany J, Silver J. Axis I psychopathology in individuals with traumatic brain injury. J. Head Trauma Rehabil. 1998;13(4):24-39.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-199808000-00003

https://doi.org/10.1097/00001199-199808000-00003 - Rao V, Lyketsos CG. Psychiatric aspects of traumatic brain injury. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2002;25:43-69. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-953X(03)00052-2

- Tadevosyan M.Ya. The role of traumatic brain injury in the dynamics of combat post-traumatic stress disorder: thesis ... cand. honey. Sciences. Yerevan, 2013;142.

- Classen C, Koopman C, Hales R, Spiegel D. Acute stress disorder as a predictor of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155:620-624. https://doi.org/10.1176/ajp.155.5.620

- O’Donnell ML, Creamer M, Pattison Ph, Atkin Ch. Psychiatric morbidity following injury. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2004;161:507-514. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.3.507

- Jorge RE, Robinson RG, Moser D, Tateno A, Crespo-Facorro B, Arndt S. Major depression following traumatic brain injury. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 2004;61(1):42-50. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.61.1.42

- Lanius RA, Bluhm R, Lanius U, Pain C.

A review of neuroimaging studies in PTSD: heterogeneity of response to symptom provocation. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:709-729.

A review of neuroimaging studies in PTSD: heterogeneity of response to symptom provocation. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40:709-729. - Ehlers A, Clark DM. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2000;38:319-345. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(99)00123-0

- Landre N, Poppe CJ, Davis N, Schmaus B, Hobbs SE. Cognitive functioning and postconcussive symptoms in trauma patients with and without mild TBI. Arch Clinic Neuropsychol. 2006;21:255-273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2005.12.007

- Sheremetyeva I.I. Exogenous organic mental disorders in the general structure of mental illness (clinical and epidemiological study): dis. doc. honey. Sciences. Moscow, 2008;144.

- Snedkov E.V. The problem of nosological independence of post-traumatic stress disorder. Journal. nevrol. and psychiatrist. 2009;109:2:8-11.

- Chukhlovina M.L. Features of diagnosis and treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with mild traumatic brain injury.

Neurosurgery, 2011;3:1:53-56.

Neurosurgery, 2011;3:1:53-56. - Sukiasyan S.G., Harutyunyan G.S. To the problem of biological therapy of traumatic stress: succinic acid and post-traumatic somatized mental disorders. Abstracts of reports and messages of the jubilee scientific conference dedicated to the 35th anniversary of the Yerevan State Institute for the Improvement of Doctors - NIH MH RA. Yerevan, 1998;100.

- Sukiasyan S.G., Manasyan N.G., Babakhanyan A.A., Kirakosyan A.L. Efficacy of ivadala in sleep disorders in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry. 2004;5:50-56.

- Dhawan J, Benveniste H, Luo Z, Nawrocky M, Smith SD, Biegon A. A new look at glutamate and ischemia: NMDA agonist improves long-term functional outcome in a rat model of stroke. Future Neurol. 2011;6:6:823-834. https://doi.org/10.2217/fnl.11.55

- Gusev E.I., Kamchatnov P.R. Plasticity of the brain in normal and pathological conditions. Zhurn nevrol and psychiatrist. 2004;104:2:73-80.

- Gavrilova S.

I., Selezneva N.D., Roshchina I.F., Kalyn Ya.B., Kolykhalov I.V., Mikhailova N.M., Zharikov G.D. Akatinol memantine: a new approach in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy. 2002;3:109-113.

I., Selezneva N.D., Roshchina I.F., Kalyn Ya.B., Kolykhalov I.V., Mikhailova N.M., Zharikov G.D. Akatinol memantine: a new approach in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Psychiatry and psychopharmacotherapy. 2002;3:109-113. - Damulin I.V. New neuroprotective and therapeutic strategy for dementia: NMDA receptor antagonist Akatinol Memantine. Rus. honey. magazine 2001;25:1178-1179.

- Selezneva N.D. Therapy of dementia in Alzheimer's disease: abstract of the thesis. dis. Dr. med. Sciences. M., 2002.

- Winblad B, Poritis N. Memantine in severe dementia: results of the 9M-Best Study (Benefit and efficiency in severely demented patients during treatment with memantine). Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(2):135-146. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199902)14:2<135::AID-GPS906>3.0.CO;2-0 "> 3.0.CO;2-0" target=" _blank">https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199902)14:2<135::AID-GPS906>3.0.CO;2-0

- Ditzler K. Efficacy and tolerability of memantine in patients with dementia syndrome.

A double blind, placebo controlled trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 1991;41(8):773–780.

A double blind, placebo controlled trial. Arzneimittelforschung. 1991;41(8):773–780. - Krupitsky E.M., Maslov D.M., Burakov A.M., Didenko T.Yu. et al. The use of memantine for the treatment of post-abstinence disorders (anhedonia syndrome) in patients with heroin addiction. Questions of narcology. 2002;3:19-25.

- Chawla P, Kochar M. What's new in clinical pharmacology and therapeutics. Wisconsin Medical Journal. 2006;105:3:24-29.

- Robinson D, Keating G. Memantine: a review of its use in Alzheimer's disease. drugs. 2006;66:11:1515-1534. https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-200666110-00015

Close metadata

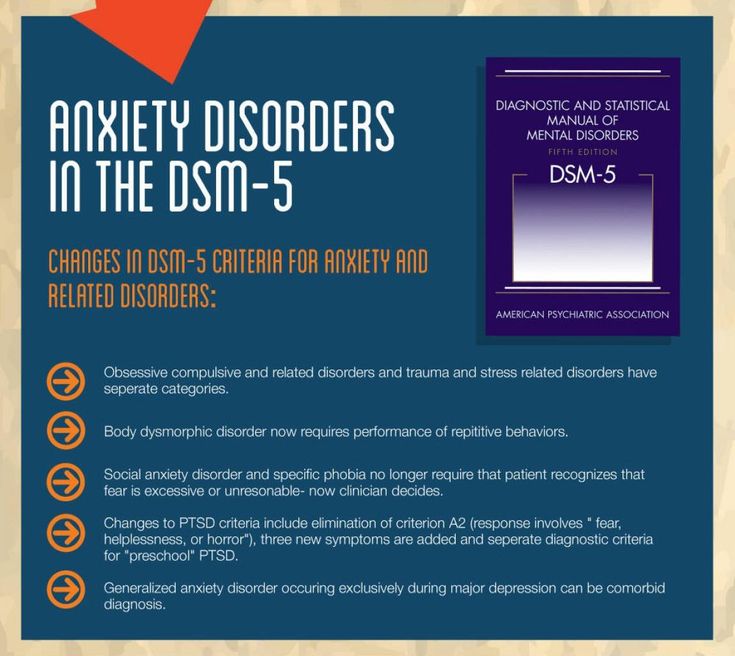

The concept of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) originated in the second half of the 19th century, but in its modern sense it was formed in the 80s of the last century, which was reflected in the American DSM-3 manual. One of the main criteria for diagnosing PTSD was the absence of any mental and somatic pathology. But subsequent studies of the problem showed the failure of many previous approaches and criteria. Moreover, it has been shown that PTSD as a psychopathological rather than a psychological category almost always manifests itself as a comorbid pathology.

Moreover, it has been shown that PTSD as a psychopathological rather than a psychological category almost always manifests itself as a comorbid pathology.

Follow-up and dynamic observations of patients with PTSD have revealed changes that are not entirely consistent with traditional ideas about PTSD as a pathology caused only by mental trauma. The studies conducted by us on the basis of the Stress Mental Health Center have shown that in the dynamics of the clinical picture of post-stress disorders, against the background of specific post-traumatic and personality disorders, the development of organic symptoms is noted. This was confirmed by the results of a study conducted at our suggestion at the Institute of Molecular Biology of the National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia, which stated the presence of inflammatory changes in the brain after exposure to extraordinary stress factors [1].

The whole variety of concepts about the development of PTSD can be represented in two approaches - cerebrotraumatic and psychosomatic.

According to the cerebrotraumatic approach, in the dynamics of combat PTSD, an initially functional disorder is replaced by an organic brain lesion, the formation of various organic changes: asthenic, psychopathic, cerebral, psychoorganic, involving many organs and systems [2]. Traumatic brain injury (TBI), depending on the severity and type, leads to structural and functional brain damage of varying degrees at the subcellular, cellular, tissue, and other levels [3]. The severity of TBI and the basis for prognosis are the depth and duration of impaired consciousness [3, 4]. With this approach, a large role is also assigned to massive psychogenic effects, vascular factors and concomitant somatic pathology.

Clinical variants of PTSD can be very different: somatoform (with gastrointestinal, cardiovascular manifestations) [5, 6], dysphoric [7], neurosis- and psychopathic-like with polymorphic psychovegetative, psychosomatic and psychoorganic states, etc. In dynamics PTSD is dominated by progressive cerebro-organic disorders and there is a transition to a general organic decline in personality.

In dynamics PTSD is dominated by progressive cerebro-organic disorders and there is a transition to a general organic decline in personality.

According to V.M. Voloshin [7], residual organic burden in patients with PTSD is detected in almost 1 / 3 patients. It should be noted that in this case, in almost 21% of cases, there were long-term consequences of closed TBI, which distinguished this type of PTSD from the others. Many authors [8–10] noted that even a mild inflammatory process can play a certain role in these cases.

Disorders caused by physical trauma are characterized by a chronic, progressive and disabling course [11]. But, what is very important, from our point of view, the combination of neurological (organic) and psychopathological syndromes gives a significant feature in the context of PTSD - pronounced neurotic (or behavioral) disorders can obscure clinically less pronounced neurological (organic) symptoms, while severe neurological disturbances may mask post-stress disturbances [12]. Assessing the long-term consequences of a traumatic brain injury, T.G. Pogodina [12] notes that organic neurological symptoms are gradually decreasing, vascular pathology comes to the fore, which over time becomes the main pathogenetic factor causing clinical decompensation.

Assessing the long-term consequences of a traumatic brain injury, T.G. Pogodina [12] notes that organic neurological symptoms are gradually decreasing, vascular pathology comes to the fore, which over time becomes the main pathogenetic factor causing clinical decompensation.

Thus, combat PTSD (in one of the variants of dynamics) is closely related to exogenous organic mental disorders (EOPD), representing one of the most significant medical and social problems of general and military psychiatry, psychiatry and emergency medicine [11, 13 -fifteen].

The psychosomatic approach reflects the ideas that exist in modern psychosomatic medicine, from the point of view of which an emotional reaction (especially “repressed emotion” in case of psychic trauma) can manifest itself as somatic symptoms [16]. Under normal conditions, intense emotional experience is blocked to the necessary extent by various psychological defense mechanisms. In the absence of such protection, somatization of certain disorders occurs through the autonomic nervous system [17]. According to many authors, functional psychosomatic disorders, being a stage or stage of the general psychosomatic process, precede the development of organic pathology [18, 19]. According to F. Alexander [18], the psychosomatic process consists of two phases: 1) functional - represented by reversible disorders of organs or tissues; 2) organic - characterized by irreversible disorders, in fact already a manifestation of organic psychosomatosis.

According to many authors, functional psychosomatic disorders, being a stage or stage of the general psychosomatic process, precede the development of organic pathology [18, 19]. According to F. Alexander [18], the psychosomatic process consists of two phases: 1) functional - represented by reversible disorders of organs or tissues; 2) organic - characterized by irreversible disorders, in fact already a manifestation of organic psychosomatosis.

Despite differences of opinion on this process, most researchers are still inclined to believe that in patients with functional disorders there is a transition to organic somatic pathology. T. Marx (quoted from [20]) notes that in patients with functional disorders of the heart and gastrointestinal tract (neurotic, somatoform disorders in the modern sense), 10 years later, symptoms of organic diseases of these systems were already present: in 10% of patients with neuroses of the heart and 20% of the stomach and intestines. The possibility of the transition of functional disorders to organic ones and the identification of the role of affective disorders and personality traits of patients is also confirmed by the studies of V. V. Marilov [20].

V. Marilov [20].

As the intensity of the affective component of the disorder decreases, the process of somatization of mental pathology increases [2, 21]. At the same time, as studies by A.M. Wayne [22], neuropsychic tension (stress) is transformed into somatic suffering through the autonomic nervous system. Physiological and neurophysiological mechanisms of such transformation are insufficiently studied to date and in many respects require further development [23, 24]. Mental and physical trauma in combat PTSD enter into certain interactions. The severity of brain injury may have a prognostic value in terms of predicting subsequent complications and developments [25]. Moderate brain injury can predict the possible development of PTSD [26]. And the psychological stress experienced at the same time affects the course of brain injury [1]. It follows that the deterioration of the condition occurs due not only to neurological damage, but also to mental causes (which is often ignored by general practitioners) [27].

Taking into account the two presented approaches to the dynamics of PTSD, let us now consider how PTSD and EOPD correlate and how the initially socio-psychological phenomenon of psychic traumatization in a combat situation “grows” into a medical, clinical phenomenon (disease), in the structure of which psychological and somatic organic manifestations, i.e. transformation of an initially functional disorder into an organic pathology of the brain [1, 28].

But in this case, it must be taken into account that TBI can be of varying severity [15, 29], which is why it is customary to divide the victims during the hostilities into three groups: those who had a severe head injury, the development of which was subsequently accompanied by the formation of organic symptoms of brain damage, and often without obvious and actual signs of PTSD; persons who have undergone mild TBI, who have experienced acute stress reactions, developing in their dynamics into PTSD; persons without TBI, but who survived a mental trauma and show a complete clinical picture of PTSD [28].

In the literature, there are two views on this issue, and contradictory ones. Supporters of the first believe that "severe TBI eliminates the possibility of encoding a traumatic experience, and this prevents subsequent signs of overcoming", and hence the development of PTSD [25]. The authors, who hold a different point of view, emphasize that any trauma can be complicated independently by depression or PTSD [30].

The relationship between PTSD and exogenous organic pathology, from our point of view, is explained by the concept of "pathologically altered soil" by S.G. Zhislin [31]. According to the concept, long-term chronic somatic and infectious diseases (rheumatism, tuberculosis, purulent and septic processes, organic brain diseases suffered in childhood and left a mark in the form of disorders in the dynamics of cerebrospinal fluid) create pathological interceptive impulses that disrupt the functional state of cortical cells and elements of the reticular formations. These changes are the "pathological soil" that manifests itself when neurosis-like disorders occur [28]. "Soil" creates an altered brain reactivity that manifests itself under certain conditions. The “reaction-soil” continuum is the cornerstone that underlies almost all changes in the vital activity of an organism [32].

These changes are the "pathological soil" that manifests itself when neurosis-like disorders occur [28]. "Soil" creates an altered brain reactivity that manifests itself under certain conditions. The “reaction-soil” continuum is the cornerstone that underlies almost all changes in the vital activity of an organism [32].

It is appropriate to note here the works shedding light on the process that explains the organic dynamics of PTSD. Many studies [10, 33, 34] have shown that the development of PTSD is associated with dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and disorders of the immune system, with disorders in the sympathetic-adrenal medullary system (decrease in cortisol levels, increased levels of dehydroepiandrosterone, necrotic tumor factor, interleukin-6). These changes underlie inflamatory (inflammatory) processes, the regulation of which can reduce the risk of developing PTSD [8, 33]. Thus, PTSD at a certain stage of its development acquires the features of an exogenous organic cerebral pathology.

Within the framework of this article, we will not dwell on the analysis of many approaches to the interpretation and understanding of such an important clinical category as EOPD [4, 35-40]. EOPD is characterized by a certain pattern of syndromic dynamics: initial asthenic, neurosis-like states are replaced by syndromes of disorders of consciousness and acute psychotic syndromes, they can be followed by protracted psychoses that turn into psychoorganic syndromes. Thus, in PTSD, which are considered as initially functional psychogenic disorders, in the context of current trends, changes are also noted at the level of neurotransmitters and hormones, pronounced structural and morphological changes in the nervous tissue are revealed [28, 41]. These changes suggest that a psychogenic (post-stress) disorder may tend to develop into an organic pathology of the brain. As shown by our studies and a number of other similar studies, such dynamics of the state occurs depending on the severity of the TBI. Data from neuroimaging studies and neuropsychological testing confirm the development of functional deficits in patients with TBI [4, 14, 24, 42, 43, 44].

Data from neuroimaging studies and neuropsychological testing confirm the development of functional deficits in patients with TBI [4, 14, 24, 42, 43, 44].

Prognostic value in terms of predicting subsequent complications and developments in TBI, especially in relation to the development of PTSD and depression, is the severity of the injury [14, 26]. This is a very important aspect in the study of PTSD; it is based on the assumption that mild brain injury takes place in the context of a traumatic event, and that the psychological stress experienced in this case affects the course of brain injury. Therefore, it is necessary to proceed from the fact that the clinical picture of the disorder and its dynamics are due not only to neurological, organic damage, but also to mental (psychological) causes [27]. But this assumption raises the question of the extent to which the symptoms of combat PTSD (post-concussion symptoms) are the result of organic and psychological factors or their interaction [25], especially since some studies [26] show that post-concussion symptoms occur as in patients with moderate TBI. gravity, and without brain injury.

gravity, and without brain injury.

Establishing the fact of the connection between TBI of moderate severity and an increase in the level of PTSD raises, from our point of view, the problem of causing PTSD TBI. This assumption is supported not only by clinical observations (as mentioned above), but also by biological and psychological studies of PTSD. According to a biological model, patients with PTSD show a decrease in the activity of the middle prefrontal cortex in the process of experiencing fear [45]. It is assumed that in the process of brain injury there is damage to the neural network involved in the processes of anxiety regulation [15]. The psychological (cognitive) model assumes that PTSD is maintained when survivors of trauma have inadequate (weakened) cognitive resources to manage memories of the trauma and are unable to involve adaptive cognitive strategies in managing traumatic experiences (for example, they are unable to assess the state of distress as a temporary phenomenon and, therefore, increase anxiety) [46, 47]. This may be why patients with mild TBI have insufficient cognitive resources to engage appropriate cognitive strategies that lead to greater levels of PTSD.

This may be why patients with mild TBI have insufficient cognitive resources to engage appropriate cognitive strategies that lead to greater levels of PTSD.

We should especially emphasize a fact that is very important, from our point of view: there are significant differences between combat and non-combat injuries. Distinctive features of combat injuries in the acute period are due to the peculiarities of the pathogenesis of mine-explosive injuries and the state of long-term chronic stress [29]. The structure of modern combat TBI is dominated by mild concussions and contusions of the brain, repeated in more than 30% of cases. The combination of factors such as trauma and stress (which is not present in other PTSD) explains the more pronounced and persistent neurological symptoms of brain injuries of combat origin, despite the commonality of morphological damage with peacetime injuries. According to E.V. Korchagin [29], "the time that has passed since the injury determines the complex nature of the consequences of the injury. " In the context of the dynamics of exogenous-organic disorders, time (age) plays a pathogenetic role. With age, from the point of view of B.N. Piven [37], the addition of the so-called vascular factor is noted, as the age increases in the process of life, the number of transferred exogenous influences increases, in many cases even insignificant; I.I. Sheremetyeva [48] believes that traces of exogenous exposure are significantly revived and turn into a pathological process.

" In the context of the dynamics of exogenous-organic disorders, time (age) plays a pathogenetic role. With age, from the point of view of B.N. Piven [37], the addition of the so-called vascular factor is noted, as the age increases in the process of life, the number of transferred exogenous influences increases, in many cases even insignificant; I.I. Sheremetyeva [48] believes that traces of exogenous exposure are significantly revived and turn into a pathological process.

Thus, the “outgrowth” of clinical manifestations of PTSD into exogenous organic traumatic disorders is a clinical reality. But the question remains whether there is a transformation of one psychopathological structure into another, or whether the initially “silent” clinic of exogenous organic pathology eventually becomes the leading one under the influence of a number of complicating external and internal factors and determines the entire clinical picture of the pathology [49].

The purpose of this study is to study the role of TBI in the development of PTSD in combat veterans.

Material and methods

A representative sample of 87 war veterans in Karabakh was surveyed. The follow-up period ranged from 15 to 18 years.

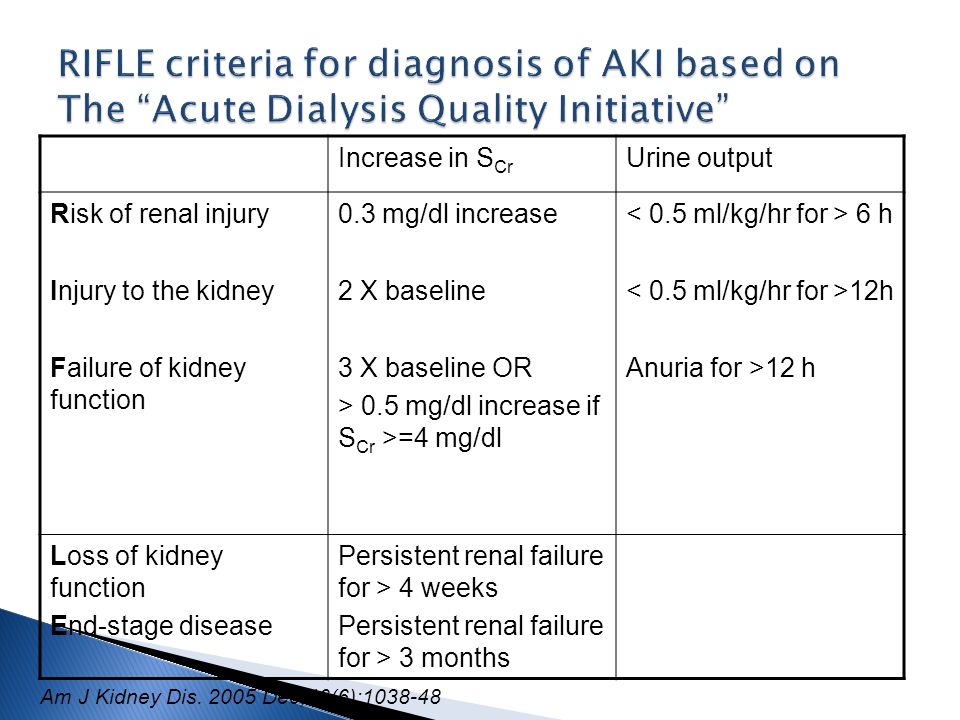

Mental status was diagnosed based on ICD-10 diagnostic criteria.

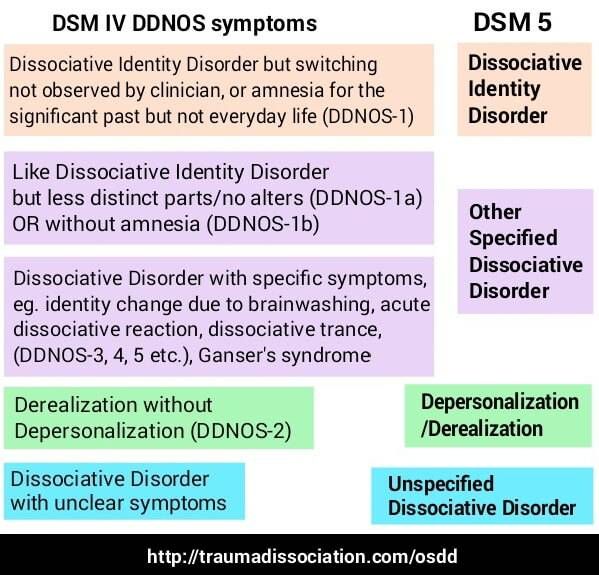

The study included patients diagnosed with "post-traumatic stress disorder" (F43.1 according to ICD-10), "chronic personality changes after experiencing a catastrophe" (F62.0). After establishing early and mid 9In the early 1900s, the diagnoses of "acute stress disorder" and "PTSD" were revised in a number of cases during re-examination.

Inclusion criteria : the presence of an extraordinary (extreme) psycho-traumatic situation, a statement of the status of a war veteran in Nagorno-Karabakh, a diagnosis of PTSD, a history of TBI, male sex, age. Exclusion criteria: presence of severe combat TBI, signs of dependence on psychoactive substances (alcohol, drugs, medications), convulsive and psychotic disorders, female sex, late (senile) age.

When examining patients, along with the general psychopathological method, a number of scales, questionnaires, as well as an examination card for a patient who was a participant in hostilities (Table 1) were used.

Table 1 . Main methods of examination of patients

| Method | Purpose |

| Hamilton scales | |

| Assessment of the degree and type of anxiety | |

| Schmishek questionnaire (adult version) | Identification of the types of accentuations of character |

Two groups of patients were formed for diagnoses: Patients with the presence of PTSRA (basic group) with reduced symptoms of PTSD (comparison group). These groups were comparable in terms of basic socio-demographic and other indicators

These groups were comparable in terms of basic socio-demographic and other indicators

Age 45.8 ± 6.4 years

Age 47.3 ± 7.1 years

The duration military operations 2-3 years

Combined trauma:

witness or participant in severe psychotraumatic situations associated with the death or injury of comrades, a threat to one's own life; mild physical trauma

Combined injury:

witness or participant in severe psychotraumatic situations associated with the death or injury of comrades, the threat to one's own life; moderate physical injury

Mississippi scale (military version): 128±11.44 points

Mississippi scale (military version): 94.3±13.90 points

But they differed statistically significantly according to all criteria of the CAPS scale.

The results of the examination of both groups were compared with the control group of 37 apparently healthy men.

Results and discussion

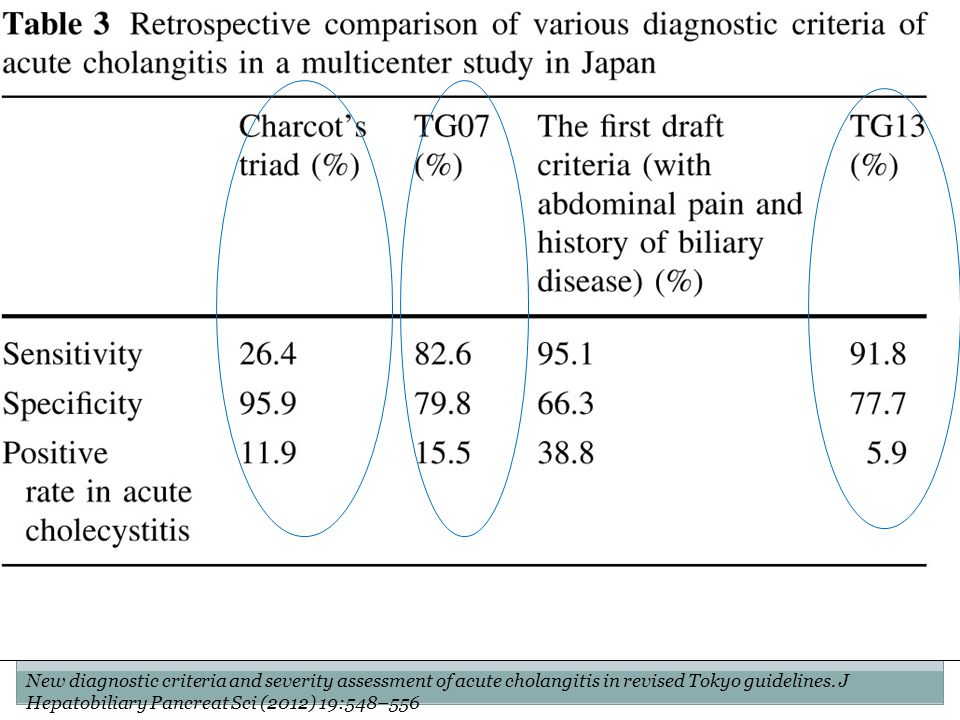

Clinical comparison of the two groups of patients revealed both their similarities and certain differences in the manifestations and dynamics of disorders. Evaluation of the manifestations of the disease, depending on belonging to one or another cluster according to CAPS, made it possible to identify the psychopathological features of each symptom of PTSD both in frequency and severity (Table 3) . The revealed features, apparently, are due to the fact that, on the one hand, all patients experienced combat traumatic stress (criterion "A" of the CAPS scale), and on the other hand, TBI.

Table 3 . Comparative analysis of PTSD symptoms in two groups

| Index, scores | 5. | 4.0 ± 2.3 | 0.0002* | |

| “Flashbek”-crossing | 3.1 3.1 3.1 3.1 5 | 2.3±2.5 | 0.144 | |

| 0003 | 4.8 ± 2.0 | 3.7 ± 2.2 | 0.015* | |

| 3.6±2.0 | 0.002* | |||

| Cluster C: “numbing” of general responsiveness | ||||

| effort to avoid thoughts, feelings, etc. associated with the trauma | 4± .2 | 3.5±2.5 | 0. | |

| effort to avoid activities, places or people that cause injury | 2.8 ± 3.0 | 1.7 ± 2.7 | 0.105 | |

| Inability to remember the important aspects of the injury | 904 | 4.2±1.9 | 0.010 | |

| Decrease in interest in significant types of activities | 5.0 ± 2.3 | 3.3 ± 2.2 | 0.001* | |

| FELLOWS OR CONSTOM .5±1.6 | 3.2±2.8 | 0.00006* | 0.0005* | |

| cluster D: symptoms of increased excitability | ||||

| Difficulties with sleeping and preservation of sleep | 7. | 0.002* | ||

| irritability or outbursts of anger | 6.7 ± 1.3 | 5.7 ± 1.8 | 0.002* | |

| Difficulties with concentration of attention | 5. | 4.0±2.2 | 0.002* | |

| excessive alertness (hypervigilance) | 3.7 ± 2.5 | 2.3 ± 2.7 | 0.002* | |

| 9041 4,1 4,1 4,1 4,1 4,1 4.1 | 2.7±2.4 | 0.001* | ||

* — differences between the values of the feature are statistically significant.

In patients with PTSD in the "post-traumatic" period, no signs of organic brain damage were detected (according to medical records, they were transient and occurred only in the first hours after TBI). The clinical picture of the disorder met the diagnostic criteria for acute stress disorder, which subsequently transformed into PTSD. In the group of patients with organic brain damage, cerebrasthenic and psychoorganic disorders were identified both in the acute period of TBI, along with symptoms of acute stress disorder, and in subsequent stages of the development of the pathological process.

The clinical picture of the disorder met the diagnostic criteria for acute stress disorder, which subsequently transformed into PTSD. In the group of patients with organic brain damage, cerebrasthenic and psychoorganic disorders were identified both in the acute period of TBI, along with symptoms of acute stress disorder, and in subsequent stages of the development of the pathological process.

In the mental status of patients of the main group, cognitive disorders were revealed in the form of deterioration in attention, absent-mindedness, memory loss for recent events, loss of interest in favorite activities, as well as indifference, irritability, hypervigilance, somatovegetative symptoms. In patients of the comparison group, cognitive disorders were manifested by a slowdown and increased exhaustion of mental processes, inertia, thoroughness of thinking, significant fatigue, as well as affective instability, increased fatigue, a “feeling of heaviness”, “brokenness” after waking up, intolerance to sound manifestations, conflict.

Analysis of the features of the clinical picture of the disorder 15–18 years later in patients with PTSD allowed us to identify several variants of PTSD. Against the background of the main manifestations of post-traumatic disorder, the dominant ones were identified: asthenic, depressive, obsessive, psychopathic disorders. In patients with organic brain damage against the background of leading symptoms, it turned out to be possible to isolate almost the same variants of the disorder (asthenic, depressive, psychopathic).

The identified clinical manifestations of the studied groups of patients suggest the presence of similarity and homogeneity of post-traumatic disorders in both groups and indicate the pathogenetic role of the intensity of TBI, which, depending on the severity, leads to the formation of an organic brain lesion or performs only a pathoplastic role, giving some features to the clinical picture PTSD. It seems natural that affective (depressive) disorders predominate in patients with PTSD, given the genetic closeness of emotional manifestations and stress ( p = 0. 025). Accordingly, psychopathic disorders were detected 2 times more often in patients with organic brain damage, which is consistent with modern concepts of organic mental disorders.

025). Accordingly, psychopathic disorders were detected 2 times more often in patients with organic brain damage, which is consistent with modern concepts of organic mental disorders.

When considering the role of TBI in the cases studied by us, it should be taken into account that we are talking about trauma not only physical (craniocerebral), but also mental. Nevertheless, from our point of view, the factor of physical (craniocerebral) injury plays a leading role in the formation of organic mental disorders in the patients examined by us. A retrospective analysis of the data obtained in the course of this study, as well as the development of clinical manifestations of PTSD, allows us to agree with B.N. Pivenem [37], who argues that the formation of a psychoorganic syndrome occurs as a result of a concussion and contusion of the brain. Clinical manifestations of exogenous organic disorders, identified in all examined patients, in the group of patients with organic brain damage were observed even in the acute period of TBI and subsequent stages of the development of the pathological process in the form of cerebrasthenic and psychopathic manifestations. Patients with PTSD in the "post-traumatic" period showed no signs of organic brain damage, but after 15-18 years they began to show symptoms of organic brain damage in the form of the same cerebrosthenic and psychopathic manifestations. The relationship between mental and physical trauma in the patients examined by us is confirmed by neurological examination data

Patients with PTSD in the "post-traumatic" period showed no signs of organic brain damage, but after 15-18 years they began to show symptoms of organic brain damage in the form of the same cerebrosthenic and psychopathic manifestations. The relationship between mental and physical trauma in the patients examined by us is confirmed by neurological examination data

45

100

–

immediately after the end of hostilities, they showed an exclusively functional pole of the psychosomatic continuum. Immediately after the injury in both groups, the symptoms of PTSD were present in all examined. The clinical picture was expressed by a psychogenic neurotic (post-stress) range of disorders: irritability, exhaustion, hypersensitivity to various external stimuli (light, sound, smells), dissomnia, conflict, somatovegetative complaints, elements of behavioral intoxication, symptoms of guilt, grief, nightmares, "stupor" , withdrawal from the situation, agitation, amnestic symptoms.

When examining them 15-18 years later, a decrease in the intensity of PTSD symptoms was found in both groups. In the comparison group (with organic brain damage and reduced symptoms of PTSD), the decrease in intensity was more significant than in the group with PTSD. Here, the dominance of disorders of the organic pole of the psychosomatic continuum was also revealed. The latter circumstance is determined by the severity of the traumatic brain injury: the more severe the injury, the more likely it is that the condition identified as PTSD will transform into an organic brain lesion.

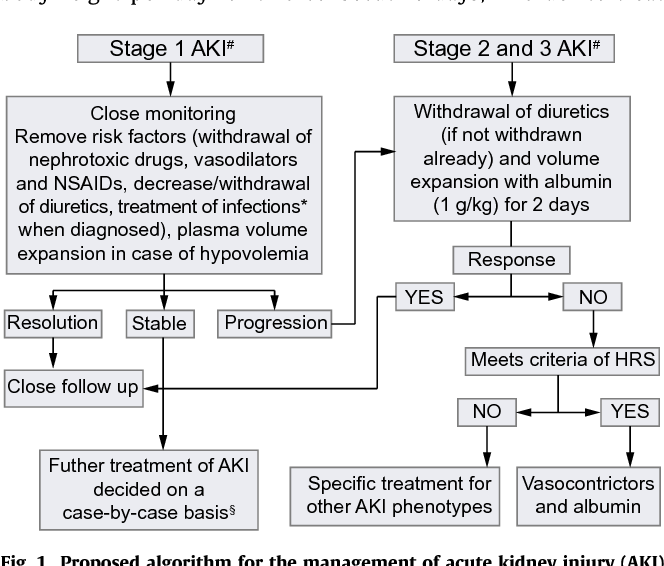

Such a complex phenomenon as PTSD requires an integrated approach to the organization of therapy and rehabilitation of these patients. Undoubtedly, the most effective method of treating patients with combat PTSD is the prevention of all wars, the solution of the pressing socio-psychological problems associated with them, which today is an insoluble task. Therefore, one should proceed from some fundamental principles and approaches available for implementation: 1) stress and post-stress disorders generally do not cause severe dysfunction and confrontation with reality, so a patient with PTSD has the opportunity to turn to a wide range of specialists - a psychotherapist, psychiatrist, neurologist; 2) carrying out a wide range of preventive measures in all forms and directions - medical measures, educational and educational work among professionals (doctors, rescuers, leaders) and large groups of the population; 3) one of the aspects of the prevention of post-stress disorders is the solution of such a most difficult task as the problem of managing extreme situations.

Therapy of post-stress disorders is a continuous, long, complex and step-by-step process that includes pharmacotherapy, psychotherapy, psychosocial interventions.

The unique biological profile of these disorders, consisting of disorders of sympathetic excitability, neuroendocrine and immune systems, requires somatic treatment and correction.

Drug treatment alleviates the symptoms of PTSD and creates the possibility of including patients in the psychotherapeutic process - group and family psychotherapy, behavioral psychotherapy, crisis intervention, relaxation techniques.

The results of the study indicate the need for early detection of PTSD after TBI and the inclusion of modern drugs with antioxidant and anxiolytic properties in complex therapy [50].

In many aspects of therapy, we have little experience, in particular, positive results on the use of succinic acid for the treatment of asthenic and adynamic conditions in PTSD [51].

An urgent problem is the therapy of sleep disorders in patients with PTSD. The drug ivadal (zolpidem), well-known in clinical practice, has proved to be a fairly effective hypnotic agent. It was found that, while accelerating the onset of sleep, inducing deep and physiological sleep, increasing the activity and performance of patients with PTSD, the drug, at the same time, did not have a significant effect in cases where there were actual "traumatic experiences" before bedtime (flashbacks, obsessive nightmares ) [52].

But in the context of this report and in connection with the above clinical and dynamic features of PTSD, it seems important to us to dwell on such an aspect of therapy as the use of nootropic drugs in the therapeutic practice of PTSD. This is a fairly diverse group of drugs that has a positive effect on the integrative functions of the brain: it activates learning processes, improves memory and mental activity, and increases the brain's resistance to aggressive influences. Nootropics are traditionally included in the complex of treatment of patients with the consequences of TBI, due to their stimulating effect on metabolic processes and improvement of microcirculation in the brain.

Nootropics are traditionally included in the complex of treatment of patients with the consequences of TBI, due to their stimulating effect on metabolic processes and improvement of microcirculation in the brain.

In addition to a number of pathophysiological mechanisms, an important role in damage to the medulla is currently assigned to excitotoxicity, which is considered as excessive exposure to excitatory neurotransmitters (glutamate and aspartate) or hyperstimulation of their receptors, which leads to damage or death of neurons. Glutamate and aspartate are among the main stimulatory neurotransmitters in the neocortex and some subcortical formations [53]. Due to their action on postsynaptic membranes, conditions are created for the formation of stable connections between neurons. Their functioning largely ensures the processes of neuroplasticity, including the functional and structural reorganization of the brain tissue in response to various influences [54].

In connection with the above, a comparatively new drug for the post-Soviet space, akatinol memantine, is of considerable interest, long-term use of which allows to some extent to stop the progression of a cognitive defect in many debilitating brain diseases of neurodegenerative, vascular and traumatic origin. Akatinol memantine has been used since 1976 in European countries and the USA for the treatment of movement disorders (cerebral palsy, parkinsonism), in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease [55-58], in patients with mild and moderate vascular dementia [59], for the treatment of post-abstinence disorders (anhedonia syndrome) in patients with heroin addiction [60]. At the same time, there are no works on the therapy of PTSD, especially those that give the so-called organic dynamics in dynamics.

Akatinol memantine has been used since 1976 in European countries and the USA for the treatment of movement disorders (cerebral palsy, parkinsonism), in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease [55-58], in patients with mild and moderate vascular dementia [59], for the treatment of post-abstinence disorders (anhedonia syndrome) in patients with heroin addiction [60]. At the same time, there are no works on the therapy of PTSD, especially those that give the so-called organic dynamics in dynamics.

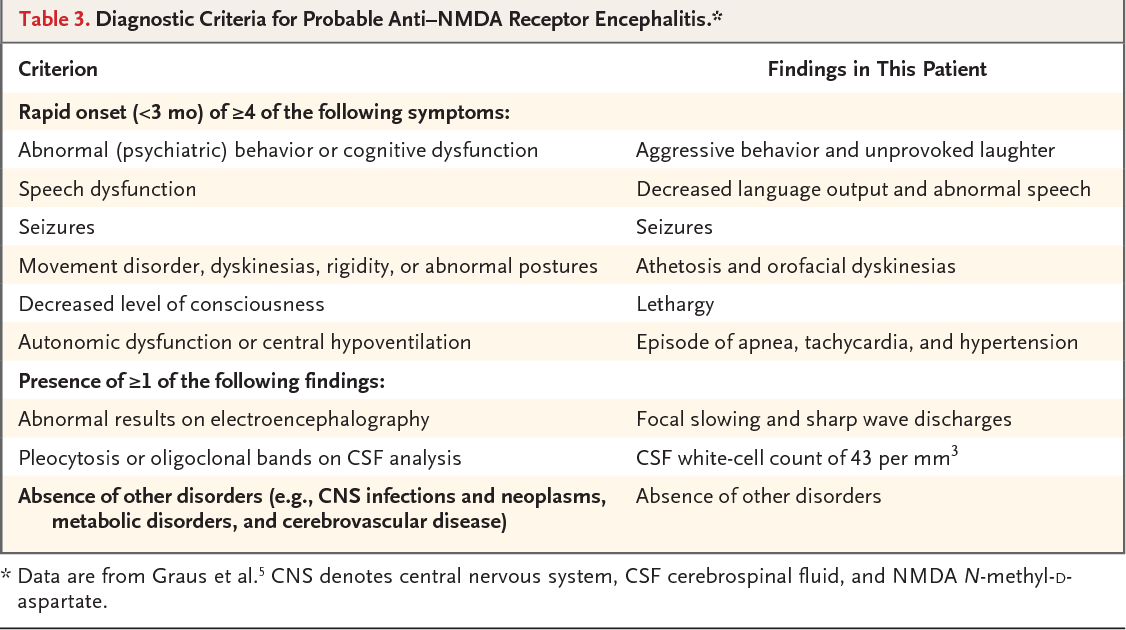

The mechanism of action of memantine suggests that the drug may be an effective treatment for at least the forms of PTSD discussed here. Memantine is a non-competitive N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonist, improves brain metabolism, has a neuroprotective effect, reducing the toxic effect of elevated glutamate concentrations on neurons, regulates ion transport, blocks calcium channels, normalizes membrane potential, improves the process of nerve impulse transmission, cognitive processes, memory and learning ability, increases daily activity, slows down the progression of dementia.

7 ± 1.8

7 ± 1.8  006*

006*  1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 2.0

1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 7.1 # 2.0