Becoming more introverted

Yes, You Do Become More Introverted With Age

Source: Fizkes/Shutterstock

People tell me all the time: “I’ve gotten more introverted as I’ve gotten older.”

On many levels, the same is true for me. In high school and college, it was normal for me to spend almost every Friday and Saturday night out with friends (even though as an introvert, it often drained me). Now, in my 30s, the perfect weekend is one with zero social plans.

And I'm not the only one who's slowed down a bit. Even my very extroverted childhood friend is more content to spend the night in, hanging out with her family. In fact, she and I hardly ever go out anymore.

Do we get more introverted as we get older?

Probably, according to Susan Cain, author of Quiet

. In a post on Quiet Revolution, Cain confirms what you've probably suspected all along—we act more “introverted” as we age. Psychologists call this phenomenon “intrinsic maturation,” and it means our personalities become more balanced as we get older—“a kind of fine wine that mellows with age,” writes Cain.

Generally, people become more emotionally stable, agreeable, and conscientious as they leave their youth behind. They also become quieter and more self-contained, needing less socializing and excitement to be happy.

Psychologists have observed intrinsic maturation in people from Germany, the UK, Spain, the Czech Republic, and Turkey. They’ve also seen it happen in chimps and monkeys.

It’s why we slow down and start enjoying a quieter, calmer life—both introverts and extroverts.

Becoming More Introverted Is a Good Thing

From an evolutionary standpoint, becoming more “introverted” as we age makes sense. And it’s probably a good thing.

“High levels of extroversion probably help with mating, which is why most of us are at our most sociable during our teenage and young adult years,” writes Cain.

In other words, acting somewhat more extroverted when you’re young helps you make important social connections and ultimately meet a life partner. (It's also why young adults often ask me if they might be an "extroverted introvert" or an ambivert, despite showing all of the signs of being true introverts.)

(It's also why young adults often ask me if they might be an "extroverted introvert" or an ambivert, despite showing all of the signs of being true introverts.)

Then—theoretically—by the time we've reached our 30s, we’ve settled down into a committed relationship. So it becomes less important to constantly be meeting new people.

“If the task of the first half of life is to put yourself out there, the task of the second half is to make sense of where you’ve been,” writes Cain.

In the married-with-children years, just think of how difficult it would be to raise a family and love the one you’re with if you were constantly popping into the next party. So it’s probably a good thing—for the sake of our families, relationships, and careers—that we become more introverted.

Once an Introvert, Always an Introvert

But there’s a catch. Our personalities can only change so much. In fact, in my book, The Secret Lives of Introverts, I like to say that our personalities change, but our

temperaments don’t.

That means, if you’re an introvert, you’ll probably always be an introvert, even when you’re 85 years old. And if you’re an extrovert—even though you’ll slow down a bit as you age—you’ll always be extroverted at your core.

Research confirms this idea. In 2004, Harvard psychologists Jerome Kagan and Nancy Snidman began studying individuals as babies and later as adults. In one study, they presented babies with unfamiliar stimuli and recorded their reactions. Some babies got upset, crying and thrashing their arms and legs. These babies were highly reactive to their environment.

Other babies didn’t get upset and remained calm around the new stimuli. These were the “low reactive” babies.

Later, Kagan and Snidman returned to these people when they were older. What they found was the babies who were “highly reactive” grew up to be more cautious and fearful—traits that overlap with being introverts or even highly sensitive people. The “low reactive” babies remained sociable and daring even as adults.

The babies’ basic temperaments—cautious or sociable—didn’t change much, even as they got older.

An Example: Your High School Reunion

If all of this sounds confusing, take your high school reunion as an example.

Let’s say you were a very introverted teenager in high school—perhaps the fifth most introverted person in your class.

As you’ve gotten older, you’ve become more comfortable in your own skin, but you’ve also become somewhat more introverted. If you liked hanging out with friends, say, once a week in high school, by the time you're in your mid-30s, you’re fine with seeing friends only once or twice a month.

When you attend your 10-year high school reunion, you notice that everyone has slowed down a bit. They’re all enjoying a somewhat more calm, stable, quieter life. But the people you remember as being quite extroverted in school are still more extroverted than you.

You’re still approximately the fifth most introverted person in your class. It’s just that the whole set has moved a little more to the introverted side.

It’s just that the whole set has moved a little more to the introverted side.

And that’s not a bad thing. In fact, it might be just what we need to flourish as adults. If there's one thing we introverts know, it's just how satisfying a quiet, calm life can be.

A version of this post originally appeared on my blog, Introvert, Dear.

LinkedIn image: goodluz/Shutterstock

You Get More Introverted With Age, According to Science

We all get more introverted as we get older, even the most extroverted among us.

I’m a classic introvert, but in my teens and twenties, it was normal for me to spend almost every weekend with friends. Now, in my thirties, the perfect weekend is one with zero social plans.

I’m not the only one socializing less now. My extroverted friend, for example, used to run through her entire contact list calling friends every time she was alone in her car. She told me she hated the quiet, the emptiness of it, because being alone was just so boring.

You know, for the entire 10-15 minutes it took to drive to the grocery store. Oh, the horror.

These days, I can rarely get her out for brunch or coffee. She’s content spending most nights at home with her husband and two kids. And I haven’t gotten one of her infamous calls in years.

So what gives? Do we get more introverted as we get older?

Probably, according to Susan Cain, author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking — and this is actually a good thing. Let me explain.

Why We Become More Introverted With Age

In a post on Quiet Revolution, Cain confirmed my suspicions: We act more introverted as we get older. Psychologists call this “intrinsic maturation.” It means our personalities become more balanced “like a kind of fine wine that mellows with age,” writes Cain.

Other research shows that our personalities do indeed change over time, and lucky for us, it’s usually for the better. For example, we become more emotionally stable, agreeable, and conscientious as we grow up, with the largest change in agreeableness happening during our thirties, and continuing to improve into our sixties. “Agreeableness” is one of the traits measured by the Big Five personality scale, and people who are high in it are warm, friendly, and optimistic.

“Agreeableness” is one of the traits measured by the Big Five personality scale, and people who are high in it are warm, friendly, and optimistic.

We also become quieter and more self-contained, needing less “people time” and excitement to feel a sense of happiness.

Psychologists have observed intrinsic maturation in people around the world, from Germany, the UK, Spain, the Czech Republic, and Turkey. And it’s not just humans; they’ve seen it happen to chimps and monkeys, too.

It’s why we slow down as we get older and start enjoying a quieter, calmer life. And yes, this happens to both introverts and extroverts.

Becoming More Introverted Is a Good Thing

From an evolutionary standpoint, becoming more introverted as we age makes sense, and it’s probably a good thing.

“High levels of extroversion probably help with mating, which is why most of us are at our most sociable during our teenage and young adult years,” writes Cain.

In other words, acting more extroverted when you’re young helps you make important social connections and ultimately meet a life partner. (Cue the flashbacks to awkward high school dances and “welcome week” in college.)

(Cue the flashbacks to awkward high school dances and “welcome week” in college.)

Then (at least in theory), by the time we reach our 30s, we’ve committed to a life path and a long-term relationship. We may have kids, a job, a spouse, and a mortgage — our lives are stable. Thus it becomes less important to constantly be branching out in new directions and meeting new people.

(Note that I said, “in theory.” In my 30s, I still don’t have kids, a mortgage, and a wedding ring. These days we have the luxury of not following evolution’s “script.”)

“If the task of the first half of life is to put yourself out there, the task of the second half is to make sense of where you’ve been,” explains Cain.

In the married-with-children years, think of how difficult it would be to raise a family and love the one you’re with if you were constantly popping into the next party. Even if you don’t marry and/or have kids, it would be hard to focus on your career, your health, and your life goals in general if you were constantly hanging out with friends.

Once an Introvert, Always an Introvert

But there’s a catch. Our personalities only change so much.

In my book, The Secret Lives of Introverts, I like to say that our personalities change but our temperaments don’t.

That means, if you’re an introvert, you’ll always be an introvert, even when you’re 90 years old. And if you’re an extrovert — even though you’ll slow down with age — you’ll always be an extrovert.

I’m talking big-picture here. Who you are at your core.

(Read more about why you can’t stop being an introvert here.)

Research confirms this phenomenon. In 2004, Harvard psychologists Jerome Kagan and Nancy Snidman studied individuals as babies, then checked in with them years later when they grew into adults. In one study, they presented the babies with unfamiliar stimuli and recorded their reactions. Some babies got upset, crying and thrashing their arms and legs; these babies were deemed “highly reactive” to their environment.

Other babies didn’t get upset at all and remained calm around the new stimuli; these were the “low reactive” babies.

Later, when Kagan and Snidman returned to these same people, they found that the individuals who were “highly reactive” as babies grew up to be more cautious and fearful. The “low reactive” babies generally remained sociable and daring as adults.

The bottom line? Our most basic temperament — cautious or sociable, introverted or extroverted — doesn’t change dramatically with age.

Join the introvert revolution. Subscribe to our newsletter and you’ll get one email, every Friday, of our best articles. Subscribe here.

An Example: Your High School Reunion

Consider, for example, your high school reunion.

Let’s say you were very introverted in high school — perhaps the third most introverted person in your graduating class. As you’ve aged, you’ve become more confident, agreeable, and comfortable in your own skin, but you’ve also become somewhat more introverted. If you liked hanging out with friends, say, once a week in high school, maybe in your thirties, you’re fine with seeing them only once a month.

If you liked hanging out with friends, say, once a week in high school, maybe in your thirties, you’re fine with seeing them only once a month.

When you attend your ten-year high school reunion, you notice everyone has slowed down a bit. They’re all enjoying a more calm, stable life. But the people who you remember as being very extroverted in high school are still much more extroverted than you.

You’re still approximately the third most introverted person in your class — but the whole group has moved a little more to the introverted side.

That’s not a bad thing. In fact, it might be the very thing we need to flourish as adults. If there’s one thing we introverts know, it’s just how satisfying a quiet life can be.

Have you become more introverted as you’ve gotten older? Let me know in the comments below.

You might like:

- Introverts and Loners Will Save Us, According to Science

- Can You Stop Being an Introvert? Probably Not, According to Science

- 25 Illustrations That Perfectly Capture the Joy of Living Alone as an Introvert

We participate in the Amazon affiliate program..jpg)

Do we become introverts with age?

35,861

A person among peopleKnow yourself

Many people notice that over time they become more and more immersed in themselves and less and less ready for active socialization. “It happens to me, too,” writes Jenn Granneman, who has devoted most of her career to studying and supporting introverts. “In high school and college, I spent every Friday and Saturday evening and night away from home. I hung out with friends - even though as an introvert it exhausted me. And now, having exchanged my fourth decade, I can say that I have a minimum of social activity in my plans.

And Jenn is not the only one who slows down the rhythm of communication over the years. She talks about her very extrovert childhood friend, who now also spends evenings at home with her family.

Are we really becoming more and more introverted? Yes exactly. In any case, Susan Cain, author of the book “Silence. The power of introverts in a world that can't stop talking." As we get older, we really start to lead a more solitary lifestyle.

The power of introverts in a world that can't stop talking." As we get older, we really start to lead a more solitary lifestyle.

Both introverts and extroverts begin to enjoy a quiet life over the years.

Psychologists call this phenomenon internal maturation: as the years go by, the personality becomes more and more balanced, “like wine that ages noblely aging,” Kane writes. Leaving adolescence behind, we gain greater emotional stability, awareness, and the ability to negotiate with others.

Many of us are becoming more peaceful and self-sufficient, and socialization is much less needed for happiness. Both introverts and extroverts begin to enjoy a quiet life over the years.

Scientists observe the process of internal maturation not only in humans (such studies were carried out in Germany, Great Britain, the Czech Republic and Turkey), but also in monkeys, in particular, in chimpanzees.

Changes for the better

From the point of view of evolution, becoming more introverted with age is natural, logical and generally good. And that's why. According to Kane, “High levels of extraversion encourage mating. Most of us are most socially active during adolescence and adolescence.” In other words, it is active socialization that helps in young years to find a partner and form a family. This task is inherent in us by nature.

And that's why. According to Kane, “High levels of extraversion encourage mating. Most of us are most socially active during adolescence and adolescence.” In other words, it is active socialization that helps in young years to find a partner and form a family. This task is inherent in us by nature.

It seems that gradually becoming more introverted is for the better. For family, relationships, and careers

Then, usually around the age of 30, we settle down and remain in a permanent relationship. Accordingly, meeting a lot of new people is no longer necessary. “If the goal of the first half of life is to find yourself and your place in it, then in the second it is important to find the meaning of existence.”

In what Jenn Granneman calls "married with kids," it would be difficult to stay faithful to one partner, let alone raise kids, while continuing to move from party to party. So it seems to gradually become more introverted - for the better. For family, relationships and career.

For family, relationships and career.

I was born an introvert, and I remain an introvert

But there is an important nuance here. Only our personality traits can change dramatically, Granneman argues. The temperature remains unchanged. This means that, most likely, an introvert will always remain an introvert, either at 8 or at 80 years old. And an extrovert, even if it slows down with age, will always remain an extrovert in its essence.

This idea is supported by a study conducted at Harvard. Psychologists Jerome Kagan and Nancy Sneedman began monitoring young children back in 2004. In particular, scientists recorded on video the reactions of babies to unfamiliar stimuli. Some children were crying and waving their arms and legs. This part of the group was very sensitive to the environment - "highly reactive". Others, when faced with the same stimuli, remained calm. These were "low-reactive" children.

A few years later, Kagan and Sneedman conducted an experiment with the same subjects who had grown up. Highly reactive children, even at an older age, were cautious and shy. Low-reactive remained contact and bold. This confirmed that our basic temperament does not change even as we grow older.

Highly reactive children, even at an older age, were cautious and shy. Low-reactive remained contact and bold. This confirmed that our basic temperament does not change even as we grow older.

Alumni Reunion - Visual Proof

"If you still have doubts about this, think back to the last Alumni Reunion," suggests Granneman.

Let's say you were a very introverted teenager in high school—say, the fifth most withdrawn student in your class. Now you have grown up and feel much more comfortable, but moreover, you have become more introverted due to age. If you once liked to hang out once a week, now, in your 40s, meeting up with friends once a month is enough.

If anyone knows what a truly calm and quiet life can be like, it's the introverts. All of the former classmates now enjoy a quieter, more stable adult life. But those who were extroverts in their youth are now much more active in communication than you are.So you are still fifth in class in terms of introversion.

It's just that you as a whole class moved a little in this direction.

And that's not bad at all, concludes Jenn Granneman. Perhaps this is exactly what we should mature to as adults. If anyone knows what a truly calm and quiet life can be like, it's introverts.

Text: Elena Sivkova Photo credit: Getty Images

New on the site

“I am in a relationship, but sometimes I dream with my high school crush”0003

“It was like getting to know each other again”: a touching story of a mother and daughter bonding

“My daughter wants a piercing and a tattoo”: how to talk to a teenager

6 steps to an easy work week: doing Sunday right

“I live with a terrible person, but I don’t dare to leave”

“A man courted me for a long time, and after sex he began to insult me”

59 ways to confess your love to yourself

Together is boring: what is a melancholy marriage and how to revive relationships

BIOLOGICAL SUBSTANTIATION OF INTRO- AND EXTRAVERTITY • EVO Medical Center

"Introvert hangover" and what are we wrong about introverts?

An introvert person has a special psychological personality, focused on his inner world.

An extrovert, respectively, its opposite, is directed “outward”, that is, into the environment and external objects.

When you hear the term "introvert", you imagine a quiet, introverted person who prefers solitude and avoids social situations. However, introverts are capable of deep interpersonal relationships, including meaningful friendships.

There is a misconception that introverts avoid social situations. In fact, this is not entirely true, it’s just that the classic introvert needs a little more time for a kind of “recharge” after social stimulation. The model of relaxation after participation in a social situation of an extrovert and an introvert is also different.

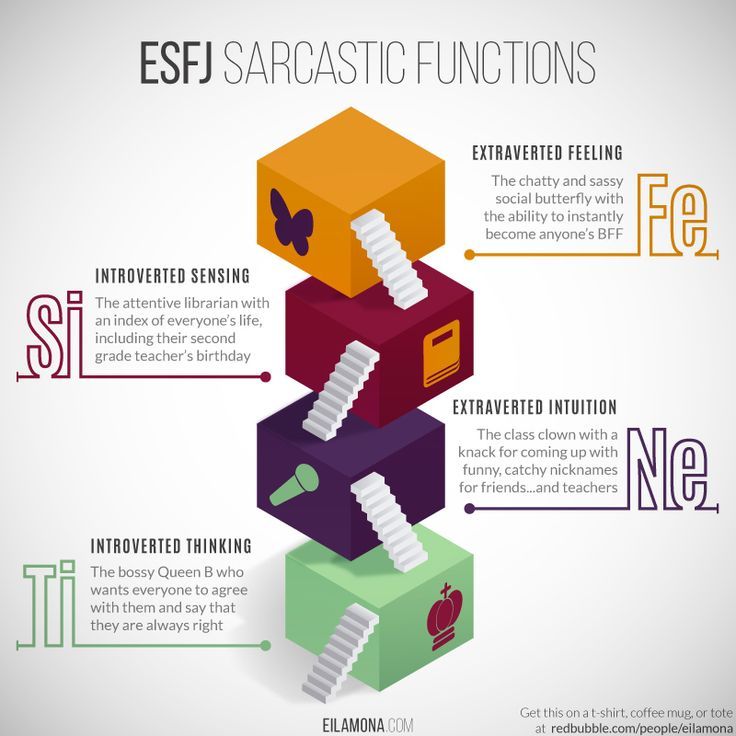

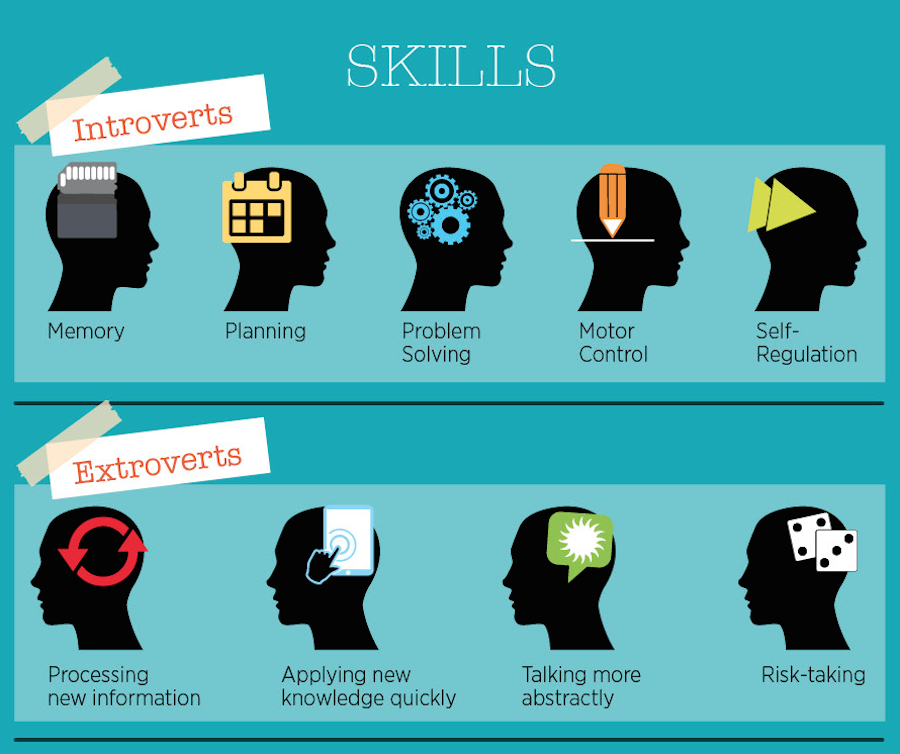

How the brain “chemizes”

The reason why introverts differ from “others” is the low dopamine threshold. Dopamine is a hormone produced by the adrenal glands - a neurotransmitter that is an important component of the "reward system" of the brain and one of the chemical factors of internal reinforcement.

Causing a feeling of pleasure or satisfaction, dopamine affects motivation, as well as switching attention. The low dopamine threshold of the introvert - entails rapid overload from stimuli. On the contrary, the high threshold of this hormone in extroverts allows them to continue to conduct any social activity much longer.

Curiously, introverts can learn to use these biological differences to their advantage, turning them into a skill rather than an obstacle.

In an interview with Business Insider, Perpetua Neo, Ph.D., says that in terms of brain chemistry, a lower dopamine threshold makes you more easily stimulated. As an introvert, you are more energetic and full of energy when you spend time on your own or in small, "intimate" groups of people you know and trust. In a large social environment with many stimuli, the extravert becomes more "hot and magnetic", while the introvert "shrinks and shrinks."

Being in the same society and receiving the same stimuli from the outside, they pass a very short path in the brain of an extravert, while in introverts, stimuli in the brain pass a long acytylcholine path through different parts of the brain.

One of them is the right frontal insular cortex, which "sees mistakes." That is why introverts tend to pay attention to all sorts of details, to be shy about their perfect mistakes, to be afraid of making a new mistake. Another site of "visiting" is the frontal lobe, which evaluates the results. This is what causes an introvert to have a tense mind that constantly worries about what might happen, as well as constantly knocking and disturbing their long-term memory "bank".

Thus, for an introvert, an event is never just an event. Extroverts can afford to instantly react to the environment, introverts who have “so much in their heads” are forced to “dig into it”, becoming vulnerable once, socially preoccupied twice, and in a certain sense more “neurotic”, as the people say . Regardless of the noise, activity, mood and size of the “company”, the introvert’s nervous system is always overloaded precisely because of the brain chemistry.

About the “hangover” of an introvert

All of the above forces the introvert to spend some time alone in order to have time to “recharge” his brain and nervous system.

This period is called the "introverted hangover". During this period, another pathway in the brain is activated that stimulates the parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for the functions of "rest and digestion", allowing introverts to "turn aside" from the attack of cortisol and adrenaline. Dr. Neo says that the opportunity to spend time recharging while sitting at home, reading a book, cleaning, or watching a non-news channel on TV calms the introvert's body and makes him happy.

How introverted or extroverted you are, or perhaps somewhere in between, is just your own neurodivium and has nothing to do with how shy or socially disturbed you are. Psychologists say that "social anxiety" is caused only by fear, which makes one avoid social situations, and not by an extra-/intro-type of personality.

"Believing themselves to be stupid, poorly versed in the matter, fearing ridicule, socially preoccupied people are deceived by their own "fraudster brain", which is excessively looking for mistakes and scolds itself," says Dr.

Perpetua. At the end of the event - "the socially preoccupied person begins to grind everything that happened in one boiler with all the things that should have been done, but not done, not done well enough, while all the good things and details are completely ignored." The foregoing makes you avoid any future social interactions because of the fear of repetition, as well as because of inconvenience, discomfort, fatigue.

“Many people mistakenly conflate introversion with social anxiety. You can be an extrovert and have social anxiety, or be painfully shy or socially awkward. The difference is that an introvert will tend to recharge on their own, while an extrovert needs busy environments and busy situations to recharge themselves.”

Introverts hate small talk

Introverts excel at social interactions on par with other people They just do it differently. For example, an extrovert tends to attend an event and interact with 50 or more people, making "as much noise as possible" out of it.

Learn more