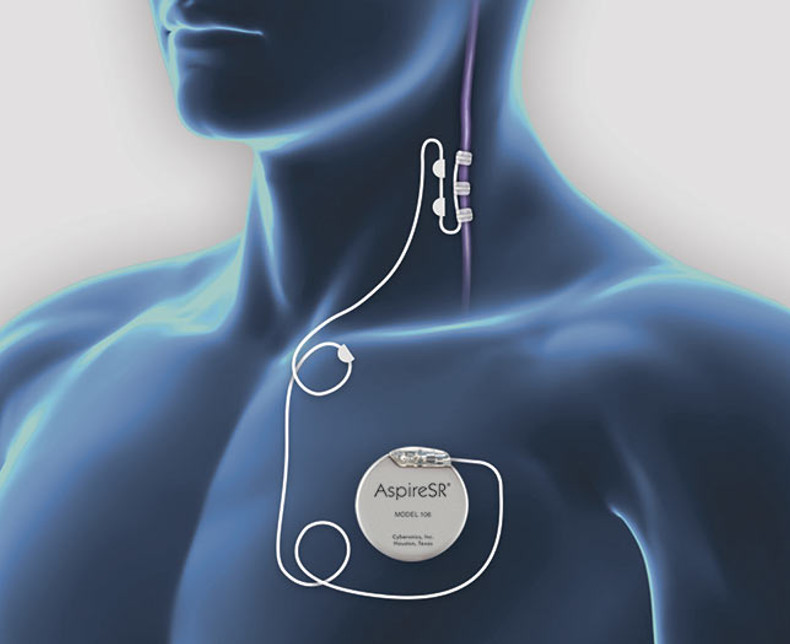

Vns for depression

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Autonomic dystonia syndrome or depression? Depressive disorders in general somatic practice | Akarachkova E.S., Vershinina S.V.

For many years in Russia and the CIS countries, the term “vegetative dystonia syndrome” (VSD) has been actively used in the designation of a number of patients, by which most practitioners understand psychogenically caused polysystemic autonomic disorders [1]. It is the psychovegetative syndrome that is defined as the most common variant of SVD, which is followed by anxiety, depression, and adaptation disorders. In such cases, we are talking about somatized forms of psychopathology, when patients consider themselves somatically ill and turn to doctors of therapeutic specialties [2]. Based on a survey of 206 neurologists and general practitioners in Russia 97% of respondents use the diagnosis "SVD" in their practice, of which 64% use it constantly and often. In more than 70% of cases, SVD is classified as the main diagnosis under the heading of somatic nosology G90.9 - disorder of the autonomic (autonomic) nervous system, unspecified or G90.8 - other disorders of the autonomic nervous system.

Based on a survey of 206 neurologists and general practitioners in Russia 97% of respondents use the diagnosis "SVD" in their practice, of which 64% use it constantly and often. In more than 70% of cases, SVD is classified as the main diagnosis under the heading of somatic nosology G90.9 - disorder of the autonomic (autonomic) nervous system, unspecified or G90.8 - other disorders of the autonomic nervous system.

At the same time, epidemiological studies demonstrate the high prevalence of depressive disorders among patients in the primary care network [3], but they are often ignored by general practitioners [4,5]. According to the Russian epidemiological program KOMPAS (2004), the prevalence of depressive disorders in general medical practice ranges from 24 to 64%. The researchers emphasize that the identified high prevalence of depressive spectrum disorders (45.9%) and depressive conditions (23.8%) among patients of the general medical network requires the widespread introduction of the screening procedure for affective (depressive) disorders in the work of institutions of the general medical healthcare network [4]. However, according to another large-scale Russian study PARUS, conducted two years later, the diagnosis of depressive conditions in general medical practice is actually not carried out, which is associated not only with the existing system of organization of care, when there are no clear diagnostic criteria for designating manifestations of non-somatic origin (and this leads to subsequent difficulties in explaining symptoms), but also with the inability to apply psychiatric diagnoses by general practitioners.

However, according to another large-scale Russian study PARUS, conducted two years later, the diagnosis of depressive conditions in general medical practice is actually not carried out, which is associated not only with the existing system of organization of care, when there are no clear diagnostic criteria for designating manifestations of non-somatic origin (and this leads to subsequent difficulties in explaining symptoms), but also with the inability to apply psychiatric diagnoses by general practitioners.

According to the academician of the Russian Academy of Medical Sciences, prof. A.B. Smulevich, an important contribution is made by practitioners' underestimation of the role of psychotraumatic situations, which, as demonstrated in the SAIL study, occurred in 86.5% of patients during the year preceding the study.

It was also found that the diagnosis of depressive states is difficult due to the clinical features of depression, a significant part of which is of the so-called "masked" nature. In most of the examined patients, depression corresponds to a mild degree of severity, which is characterized by the obliteration of the key diagnostic manifestations of hypothymia (sadness, depression, etc.). At the same time, they have a wide range of psycho-vegetative (somato-vegetative) symptoms, which are considered within the framework of general mental and somatic pathology. These symptoms occurred in all patients of the study sample. Moreover, some of them are fatigue, headaches, irritability, lethargy, loss of strength, decreased ability to work, memory and attention impairment, insomnia, dizziness, heart pain, back pain, palpitations, neck pain, sweating, joint pain, shortness of breath, pain in the legs, drowsiness, lack of air, abdominal pain, interruptions in the heart - noted in more than half of the patients. The researchers suggested that these symptoms are regarded by general practitioners only as a manifestation of a somatic disease and are not associated with depression [5].

In most of the examined patients, depression corresponds to a mild degree of severity, which is characterized by the obliteration of the key diagnostic manifestations of hypothymia (sadness, depression, etc.). At the same time, they have a wide range of psycho-vegetative (somato-vegetative) symptoms, which are considered within the framework of general mental and somatic pathology. These symptoms occurred in all patients of the study sample. Moreover, some of them are fatigue, headaches, irritability, lethargy, loss of strength, decreased ability to work, memory and attention impairment, insomnia, dizziness, heart pain, back pain, palpitations, neck pain, sweating, joint pain, shortness of breath, pain in the legs, drowsiness, lack of air, abdominal pain, interruptions in the heart - noted in more than half of the patients. The researchers suggested that these symptoms are regarded by general practitioners only as a manifestation of a somatic disease and are not associated with depression [5]. It is the somatization of mental disorders in the clinic of internal diseases that makes a significant contribution to underdiagnosis, when, behind a multitude of somatic and autonomic complaints, it is difficult for a general practitioner to identify psychopathology, which is often subclinically pronounced and does not fully meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder [6], but leads to a significant decrease in quality of life, professional and social activity [7,8] and is widespread in the population. According to Russian and foreign researchers, about 50% of individuals in society have either threshold or subthreshold disorders [4,9,ten].

It is the somatization of mental disorders in the clinic of internal diseases that makes a significant contribution to underdiagnosis, when, behind a multitude of somatic and autonomic complaints, it is difficult for a general practitioner to identify psychopathology, which is often subclinically pronounced and does not fully meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental disorder [6], but leads to a significant decrease in quality of life, professional and social activity [7,8] and is widespread in the population. According to Russian and foreign researchers, about 50% of individuals in society have either threshold or subthreshold disorders [4,9,ten].

According to foreign studies, up to 29% of patients in general somatic clinics have subthreshold manifestations of depression in the form of somatic symptoms that are difficult to explain by existing somatic diseases [11], and their isolation is disputed by numerous cross and syndromic diagnoses, which contributes to a negative iatrogenic effect in the form of a possible increase or exacerbation of somatovegetative complaints. In clinical practice, there are frequent situations when doctors react negatively to symptoms that they cannot explain from the standpoint of organic pathology. The patient is subjected to intensive examination. And if the results do not confirm the presence of a physical illness, doctors tend to underestimate the severity of symptoms (eg, pain or disability) [12]. For their part, patients may view intensive medical diagnosis as pushy and sometimes hostile towards them. In such cases, the expectations of patients from a medical consultation may differ from those of a doctor [13]. Along with this, somatized patients actively use medical terminology to describe their symptoms. They may be deeply convinced of their physical (somatic) origin, as well as that the doctor erroneously assesses their sensory symptoms [14]. It should be noted that the diagnostic label is very important for the patient and can either suit (if the diagnosis is perceived as confirmation of the reality of the problem) or offend the patient (if the “psychological” term is used) [15].

In clinical practice, there are frequent situations when doctors react negatively to symptoms that they cannot explain from the standpoint of organic pathology. The patient is subjected to intensive examination. And if the results do not confirm the presence of a physical illness, doctors tend to underestimate the severity of symptoms (eg, pain or disability) [12]. For their part, patients may view intensive medical diagnosis as pushy and sometimes hostile towards them. In such cases, the expectations of patients from a medical consultation may differ from those of a doctor [13]. Along with this, somatized patients actively use medical terminology to describe their symptoms. They may be deeply convinced of their physical (somatic) origin, as well as that the doctor erroneously assesses their sensory symptoms [14]. It should be noted that the diagnostic label is very important for the patient and can either suit (if the diagnosis is perceived as confirmation of the reality of the problem) or offend the patient (if the “psychological” term is used) [15]. Considering that it is very difficult for a general practitioner in the absence of experience to find differences, most researchers are of the opinion that psychiatric diagnoses should be made by specialist psychiatrists. In practice, however, most of these patients are referred to those with very limited psychiatric experience. As a result, the severity of the pathology is underestimated, which can lead to detrimental consequences in the form of a high risk of developing iatrogenic harm [16].

Considering that it is very difficult for a general practitioner in the absence of experience to find differences, most researchers are of the opinion that psychiatric diagnoses should be made by specialist psychiatrists. In practice, however, most of these patients are referred to those with very limited psychiatric experience. As a result, the severity of the pathology is underestimated, which can lead to detrimental consequences in the form of a high risk of developing iatrogenic harm [16].

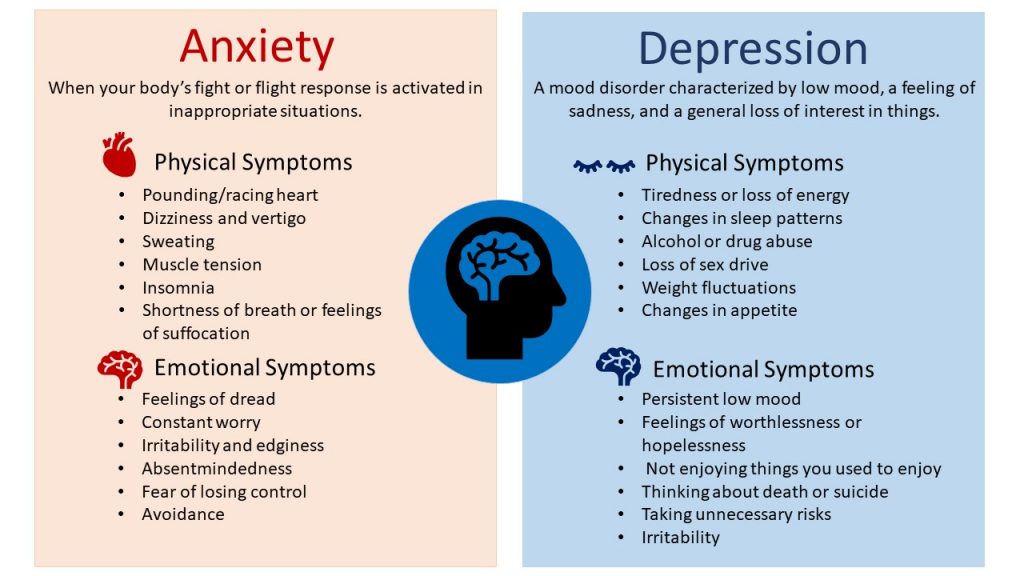

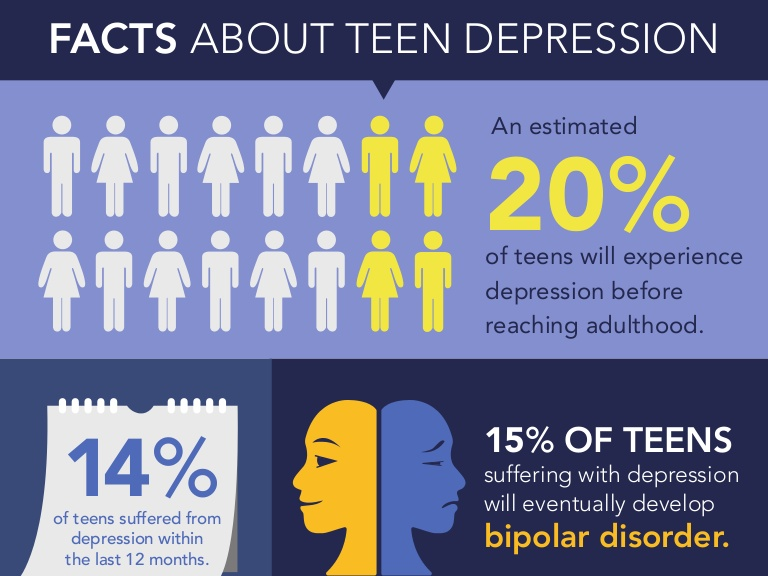

Thus, clinically significant depression is the most common psychiatric condition observed in the population in 20% of women and 10% of men. Among patients with chronic diseases, this percentage is much higher - from 15 to 60%. More than 40% of patients suffer from clinically significant depressive disorders, most of which can be classified as major depressive disorder (in ICD-10 this condition is classified as recurrent depressive disorder - F33). However, the contrast between high comorbidity of depression and disease burden, on the one hand, and insufficient diagnosis and treatment of depression, on the other hand, still persists in the primary health care system [17]. At the same time, “bodily” (somatic) symptoms of depression are often associated with concomitant anxiety, which, in turn, further increases somatic and emotional distress and contributes to diagnostic difficulties [18]. To date, sufficient evidence has been accumulated that anxiety disorders usually precede depression, increasing the risk of its development by about 3 times. It is known that in the first three decades of life there is a high risk of developing anxiety disorders, which, as a rule, are primary and lead to the development of secondary depression.

At the same time, “bodily” (somatic) symptoms of depression are often associated with concomitant anxiety, which, in turn, further increases somatic and emotional distress and contributes to diagnostic difficulties [18]. To date, sufficient evidence has been accumulated that anxiety disorders usually precede depression, increasing the risk of its development by about 3 times. It is known that in the first three decades of life there is a high risk of developing anxiety disorders, which, as a rule, are primary and lead to the development of secondary depression.

Anxiety disorders and depression are associated with a wide range of psychosocial disorders in the form of a negative impact on treatment, career, work productivity, partnership and interpersonal interactions, quality of life, suicidal behavior [19]. It has been found that about 10% of depressive disorders can be prevented through successful early intervention for social phobia [20]. If all anxiety disorders among 12–24 year olds are successfully treated, then 43% of all depressive episodes in early adult life could be prevented [21].

Despite the impossibility of using psychiatric diagnoses by general practitioners, somatovegetative manifestations of depression in a large number of patients can be detected at the syndromic level in the form of a psychovegetative syndrome. Similar syndromic diagnosis includes:

1. Active detection of polysystemic autonomic disorders.

2. Exclusion of somatic diseases based on the patient's complaints.

3. Identification of the relationship between the dynamics of the psychogenic situation and the appearance or aggravation of vegetative symptoms.

4. Clarification of the nature of the course of vegetative disorders.

Active detection of mental symptoms associated with autonomic dysfunction, such as reduced (dreary) mood, anxiety or guilt, irritability, sensitivity and tearfulness, a sense of hopelessness, decreased interests, impaired concentration, as well as a deterioration in the perception of new information, changes in appetite, a feeling of constant fatigue , sleep disturbance.

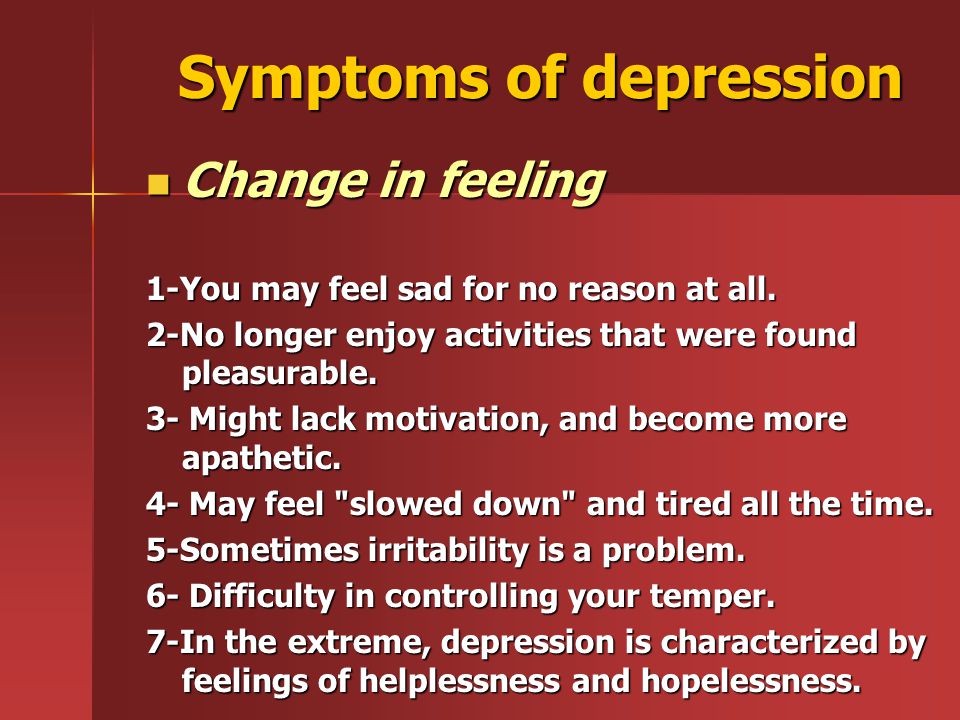

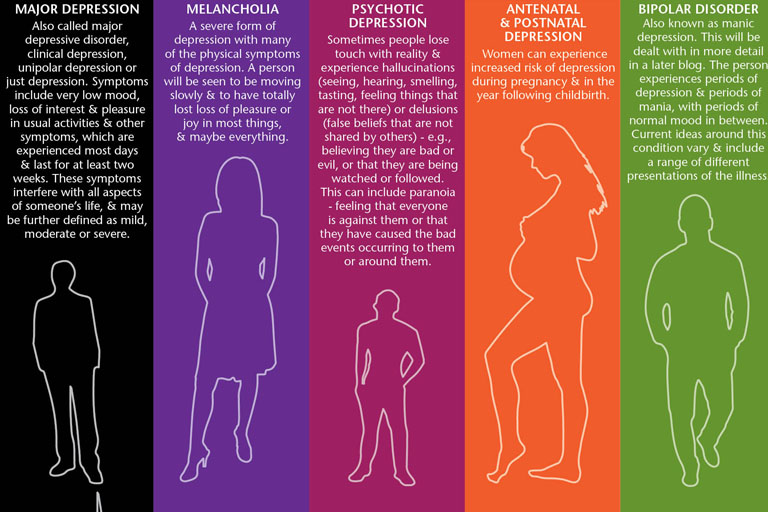

It is important for the doctor to identify psychopathology and assess its severity. In the classical sense, depression is a mental disorder characterized by depressed mood (hypothymia) with a negative, pessimistic assessment of oneself, one's position in the present, past and future. Along with depression (in typical cases in the form of vital melancholy), depression includes ideational and motor inhibition with a decrease in urges to activity or anxious excitation (up to agitation). Mental hyperalgesia (mental pain) characteristic of depressive patients is associated with feelings of guilt, decreased self-esteem, suicidal tendencies, and painful physical self-feeling is associated with “somatic” symptoms (sleep disorders; a sharp decrease in appetite up to depressive anorexia with a decrease in body weight by 5% or more from baseline within a month; decreased libido, menstrual disorders up to amenorrhea; headaches; decreased salivation; dryness of the tongue and other mucous membranes and skin, and other somatovegetative dysfunctions). Decreased mood persists throughout the entire depressive episode and is little subject to fluctuations depending on changes in the circumstances of the patient's life. A typical sign of depression is also an altered circadian rhythm: improvement or (rarely) worsening of well-being in the evening [22]. Clear diagnostic criteria contribute to the identification of depression. The main symptoms of depression according to ICD-10 include:

Decreased mood persists throughout the entire depressive episode and is little subject to fluctuations depending on changes in the circumstances of the patient's life. A typical sign of depression is also an altered circadian rhythm: improvement or (rarely) worsening of well-being in the evening [22]. Clear diagnostic criteria contribute to the identification of depression. The main symptoms of depression according to ICD-10 include:

• depression of mood, obvious in comparison with the patient's inherent norm, prevailing almost daily and most of the day and lasting at least 2 weeks, regardless of the situation;

• a distinct decrease in interest or pleasure in activities usually associated with positive emotions;

• Decreased energy and increased fatigue.

Additional symptoms include:

• reduced ability to concentrate and attention;

• Decreased self-esteem and feelings of self-doubt;

• ideas of guilt and self-abasement;

• a gloomy and pessimistic vision of the future;

• disturbed sleep;

• disturbed appetite;

• excitation or retardation of movements or speech;

• ideas or actions about self-harm or suicide;

• decrease in sexual desire.

For a reliable diagnosis, the presence of any 2 main and 2 additional symptoms is sufficient. It is important that information about the presence of the listed criteria can be obtained primarily from answers to questions that are not posed in terms of the presence of specific symptoms (do you experience sadness, depression, anxiety or indifference), but related to changes in general well-being, mood, lifestyle (not whether the joy of life has disappeared, whether tears are near, how long has a pessimistic assessment of events prevailed) [22]. Manifestations of ideomotor agitation or lethargy, suicidal ideas or attempts, as well as a decrease in sexual desire indicate the presence of severe depression in the patient, which requires the immediate help of a psychiatrist.

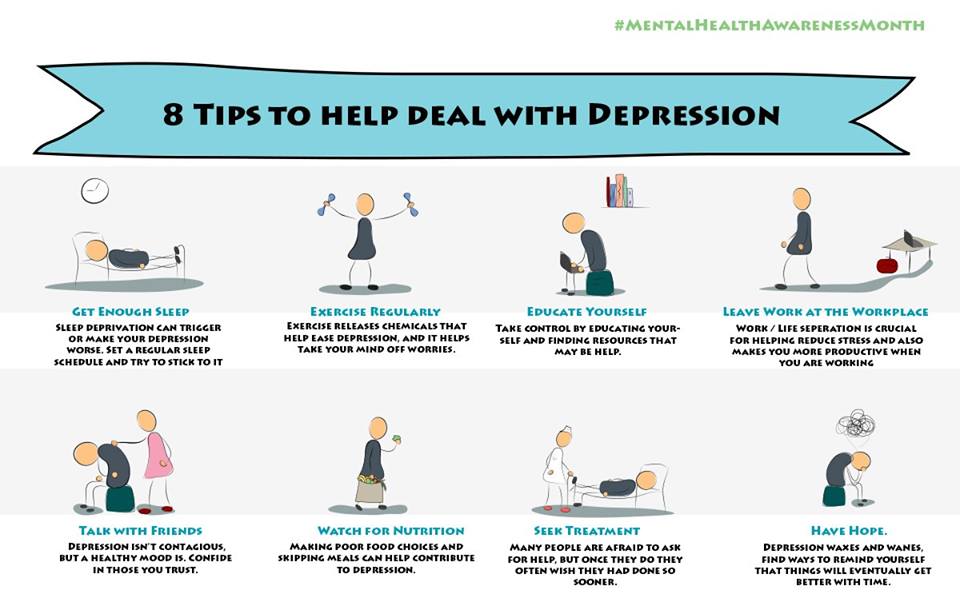

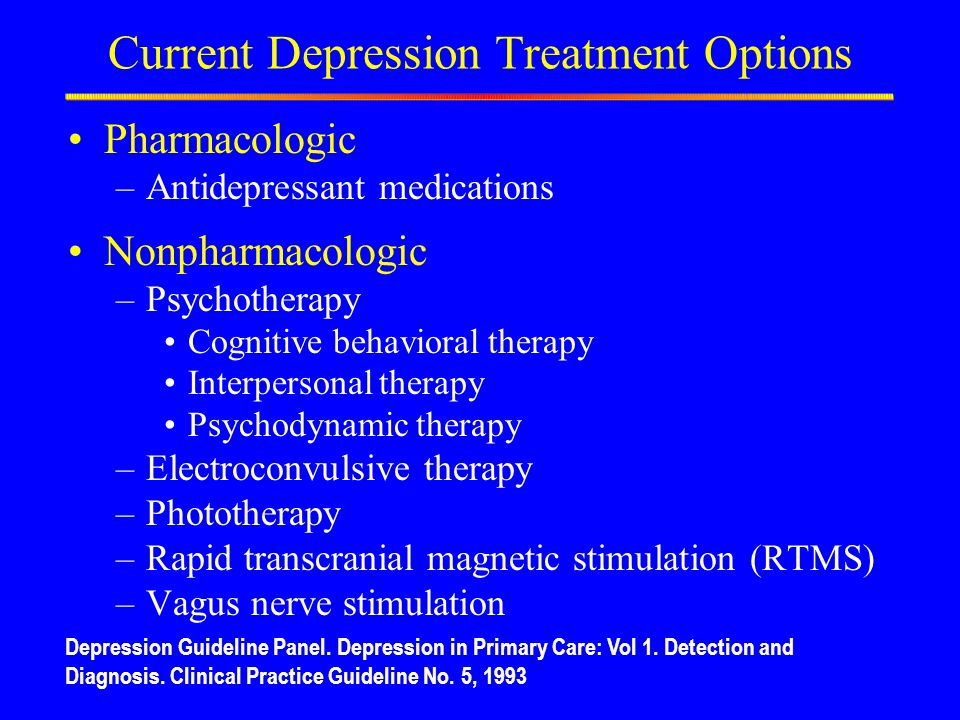

The success of the treatment of depressive disorders depends on the correct diagnosis and the choice of adequate therapeutic tactics. The current standards for the treatment of patients with "SVD", and in particular, with a diagnosis defined by the ICD-10 code G90. 8 or G90.9, along with symptomatic agents (ganglioblockers, angioprotectors, vasoactive agents) recommend the use of sedatives, tranquilizers , antidepressants, small antipsychotics [23]. It should be noted that most symptomatic drugs are ineffective. Patients need to prescribe psychotropic drugs. Explaining the essence of the disease to the patient allows one to argue the need for prescribing psychotropic therapy.

8 or G90.9, along with symptomatic agents (ganglioblockers, angioprotectors, vasoactive agents) recommend the use of sedatives, tranquilizers , antidepressants, small antipsychotics [23]. It should be noted that most symptomatic drugs are ineffective. Patients need to prescribe psychotropic drugs. Explaining the essence of the disease to the patient allows one to argue the need for prescribing psychotropic therapy.

Antidepressants from the group of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are currently the first choice for the treatment of depressive, anxiety and mixed anxiety-depressive disorders. predominantly the deficiency of this neurotransmitter implements psychovegetative manifestations of psychopathology. Among the advantages of SSRIs, one can single out a small number of side effects, the possibility of long-term therapy and a wide therapeutic spectrum with a fairly high safety. However, despite all their positive aspects, SSRIs also have a number of disadvantages. Among the side effects of SSRIs are increased anxiety, nausea, headaches, dizziness during the first few weeks of treatment, as well as their frequent lack of effectiveness. In the elderly, SSRIs may lead to unwanted interactions. SSRIs should not be prescribed to patients taking NSAIDs, because the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding increases, as well as for patients taking warfarin, heparin, tk. SSRIs enhance the antithrombotic effect, which is a threat of bleeding.

Among the side effects of SSRIs are increased anxiety, nausea, headaches, dizziness during the first few weeks of treatment, as well as their frequent lack of effectiveness. In the elderly, SSRIs may lead to unwanted interactions. SSRIs should not be prescribed to patients taking NSAIDs, because the risk of gastrointestinal bleeding increases, as well as for patients taking warfarin, heparin, tk. SSRIs enhance the antithrombotic effect, which is a threat of bleeding.

Dual acting antidepressants and tricyclic antidepressants are the most effective drugs. In neurological practice, these drugs, in particular, selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), have shown high efficacy in patients suffering from chronic pain syndromes of various localizations [24–26]. However, with increasing efficacy, the tolerability and safety profile may deteriorate. Along with a wide range of positive effects, these drugs have a wide list of contraindications and side effects, as well as the need for dose titration, which limits their use in the general somatic network.

In this regard, of particular interest is the domestic original drug Azafen (pipofezin), including its new retarded form, Azafen-MB, which was created specifically for use in therapeutic practice and has been widely used since 1969. The drug competes with modern antidepressants: being a representative of TCAs, it has a fairly pronounced antidepressant and sedative (anxiolytic) effect, stopping both mental and somatic symptoms of anxiety. At the same time, Azafen does not cause pronounced sedation, relaxation and drowsiness during the daytime. At the same time, it practically does not have Manticholinergic activity and does not affect the activity of monoamine oxidase, does not have a cardiotoxic effect, which makes it well tolerated and can be widely used on an outpatient basis, in somatic patients, and in the elderly [27]. Taking the drug in the evening hours contributes to better falling asleep. Azafen is well tolerated, which allows it to be used in elderly patients, including those with somatic pathology, and for long-term courses as a relief and maintenance therapy. Treatment can be carried out both in the hospital and on an outpatient basis. The creation of a new form of the drug, Azafen-MV, seems promising not only in terms of ease of use, but also in terms of obtaining new indicators of efficacy and safety. Simple Azafen at a dose of 75–100 mg/day has established itself as an effective drug for mild depression, at a dose of 100–150 mg/day for moderate depression. Azafen-MB at a dose of 150–300 mg/day is effective in moderate depression, and at a dose of 300–400 mg/day it significantly reduces symptoms in severe depression [28]. Own experience with the use of Azafen at a dose of 100 mg / day, divided into 2 doses, shows that the psychotropic effect of Azafen is associated with a combination of thymoanaleptic, activating and tranquilizing properties. According to our data, the antidepressant effect of Azafen is not accompanied by a negative effect on attention, speed and accuracy of the task, as well as on the state of the cardiovascular system. It is important to note that in patients with initial tachyarrhythmia during treatment, normalization of the heart rhythm took place.

Treatment can be carried out both in the hospital and on an outpatient basis. The creation of a new form of the drug, Azafen-MV, seems promising not only in terms of ease of use, but also in terms of obtaining new indicators of efficacy and safety. Simple Azafen at a dose of 75–100 mg/day has established itself as an effective drug for mild depression, at a dose of 100–150 mg/day for moderate depression. Azafen-MB at a dose of 150–300 mg/day is effective in moderate depression, and at a dose of 300–400 mg/day it significantly reduces symptoms in severe depression [28]. Own experience with the use of Azafen at a dose of 100 mg / day, divided into 2 doses, shows that the psychotropic effect of Azafen is associated with a combination of thymoanaleptic, activating and tranquilizing properties. According to our data, the antidepressant effect of Azafen is not accompanied by a negative effect on attention, speed and accuracy of the task, as well as on the state of the cardiovascular system. It is important to note that in patients with initial tachyarrhythmia during treatment, normalization of the heart rhythm took place. Subjective improvement in patients began on average from the 12th day of therapy. In our practice, side effects occurred in 7% of patients, which manifested itself in general weakness, drowsiness, and dizziness. The severity of these phenomena was weak. However, it was not possible to establish a clear connection with taking the drug, because. these patients initially complained of general weakness, dizziness and drowsiness during the day due to night sleep disturbances [29].

Subjective improvement in patients began on average from the 12th day of therapy. In our practice, side effects occurred in 7% of patients, which manifested itself in general weakness, drowsiness, and dizziness. The severity of these phenomena was weak. However, it was not possible to establish a clear connection with taking the drug, because. these patients initially complained of general weakness, dizziness and drowsiness during the day due to night sleep disturbances [29].

Thus, Azafen is effective in depressive states of various origins, has a beneficial effect on patients with borderline neurotic states, especially in anxiety-depressive (reduces feelings of anxiety, internal tension, reduces stiffness of movements) and asthenic disorders, with anorexia nervosa, climacteric syndrome, with masked depression, manifested by algic phenomena (cephalgia), sleep disturbances. The drug has the ability to normalize sleep with the absence of subsequent drowsiness [30, 31]. Azafen can be used as a corrector for the prevention and relief of extrapyramidal disorders that occur with long-term use of antipsychotics [27].

Given the complexity of managing patients in the initial period of antidepressant treatment, the use of a "benzodiazepine bridge" is recommended. Optimal means in this situation are GABA-ergic, serotonin-, norepinephrine or drugs with multiple actions. Among GABAergic drugs, benzodiazepines can be called the most suitable. However, according to the profile of portability and safety, this group is not the means of the first line of choice. Much more often, high-potential benzodiazepines, such as alprazolam, clonazepam, and lorazepam, are used in the treatment of patients with pathological anxiety. They are characterized by a rapid onset of action, they do not cause an exacerbation of anxiety at the initial stages of therapy (unlike selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors). But these drugs are not without drawbacks common to all benzodiazepines: the development of sedation, the potentiation of the action of alcohol (which is often taken by these patients), lead to the formation of dependence and withdrawal syndrome, and also have an insufficient effect on comorbid anxiety symptoms. This makes it possible to use benzodiazepines only in short courses (in the first 2-3 weeks of the initial period of antidepressant therapy).

This makes it possible to use benzodiazepines only in short courses (in the first 2-3 weeks of the initial period of antidepressant therapy).

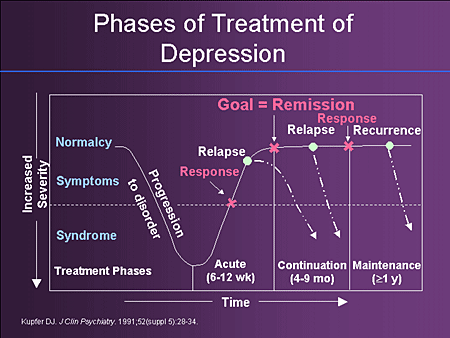

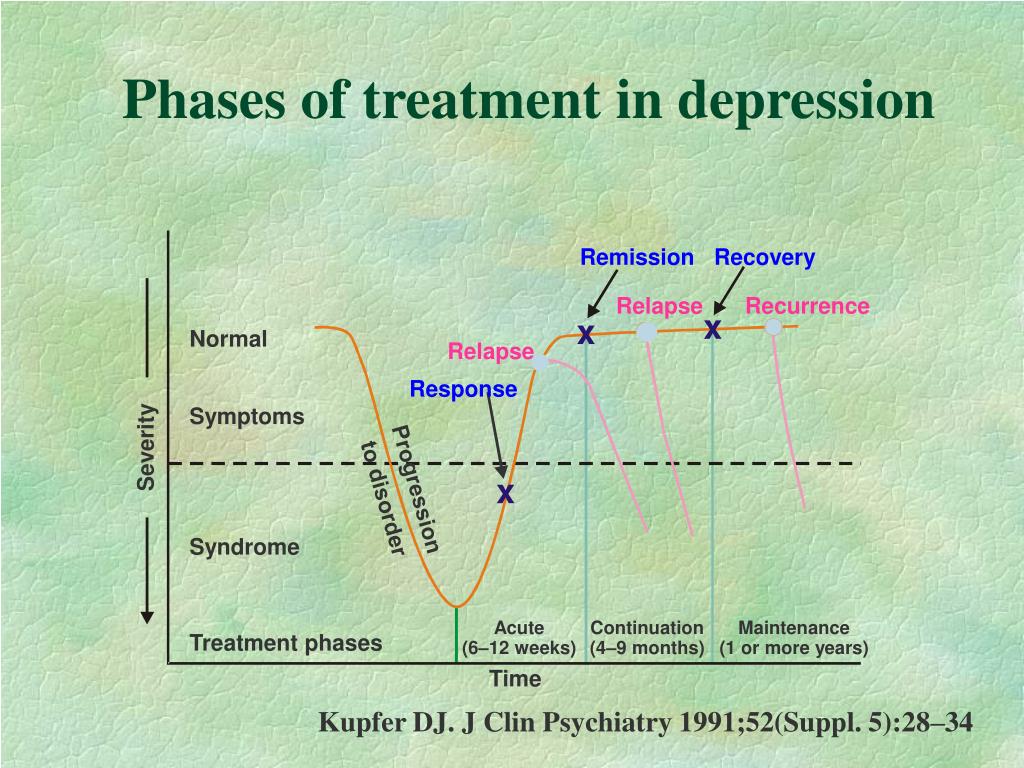

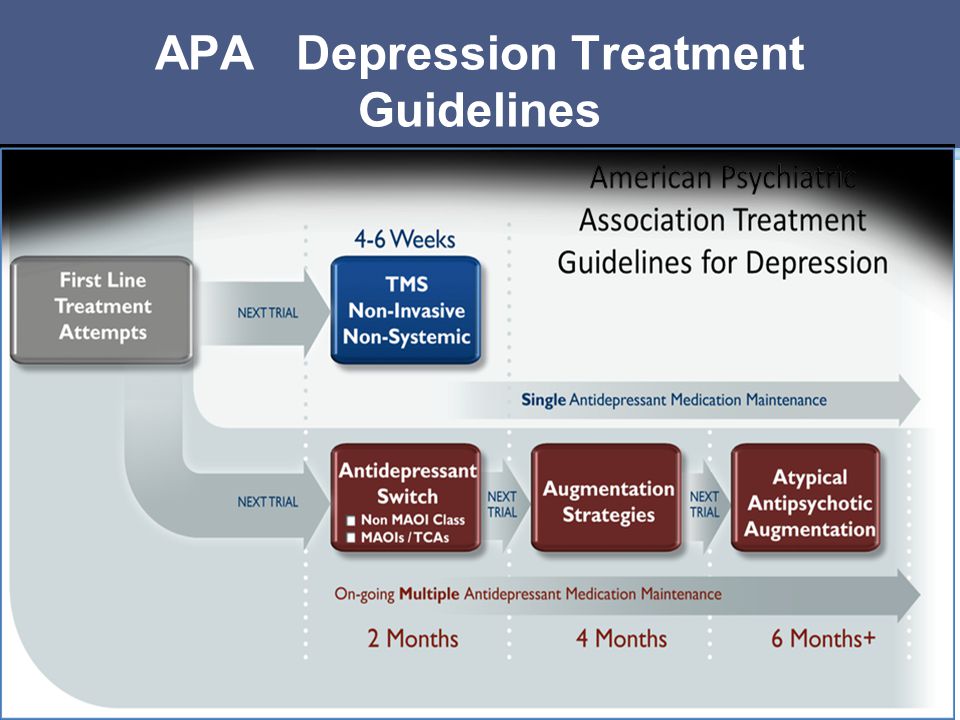

General practitioners often face difficulties in determining the duration of prescribed therapy. This is due to the lack of information about the optimal duration of treatment and the lack of standards for its duration. It is important to remember that short courses (1-3 months) often lead to a subsequent exacerbation. For a practicing physician, the following therapy regimen can be recommended:

- after 2 weeks from the start of using a full therapeutic dose of an antidepressant, one can judge the initial effectiveness and side effects of treatment. During this period, the use of a "benzodiazepine bridge" is possible;

- with good and moderate tolerance, as well as in the presence of signs of positive dynamics in the patient's condition, it is necessary to continue therapy for up to 12 weeks;

- after 12 weeks, the issue of continuing therapy for the next 6-12 months or finding alternative methods should be decided;

– management of patients with resistant conditions by general practitioners is undesirable. In these situations, the help of a psychiatrist or psychotherapist is needed. There are no clear recommendations in this regard. In the absence of specialized care and the existing need, a switch to antidepressants with a different mechanism of action is recommended.

In these situations, the help of a psychiatrist or psychotherapist is needed. There are no clear recommendations in this regard. In the absence of specialized care and the existing need, a switch to antidepressants with a different mechanism of action is recommended.

Cancellation of the drug can occur abruptly (the so-called "break" of treatment) or gradually (graded withdrawal), or by switching to "soft" anxiolytics. It is important to note that the choice of drug withdrawal tactics depends primarily on the psychological mood of the patient. In the presence of fear in the patient before the abolition of a long-term drug, the very withdrawal of the drug can cause a worsening of the condition. In this regard, the most appropriate would be methods of gradual withdrawal or transfer of the patient to soft, including herbal remedies.

As non-drug interventions and with the abolition of antidepressants, various methods of psychotherapy can be used, in particular, cognitive-behavioral and rational psychotherapy, as well as relaxation techniques: autogenic training, respiratory-relaxation training, progressive muscle relaxation, relaxation techniques using biofeedback.

Thus, the high representation of patients with depression in general somatic practice makes it necessary to detect these disorders in time and determine their severity. In his practice, the doctor can synodromically determine the identified psychopathology in the form of psychovegetative disorders against the background of autonomic dystonia syndrome, followed by the appointment of adequate psychotropic therapy, and also refer patients for consultation to psychiatrists.

Literature

1. Vegetative disorders: clinic, treatment, diagnostics./ed. A.M. Wayne. – M.: 1998. – 752 p.

2. Krasnov V.N., Dovzhenko T.V., Bobrov A.E., Veltshchev D.Yu., Shishkov S.N., Antipova O.S., Yaltseva N.V., Bannikov G.S., Kholmogorova A.B., Garanyan N.G., Kovalevskaya O.B. “Improving the methods of early diagnosis of mental disorders (based on interaction with primary health care specialists) / Ed. V.N. Krasnova.–M.: ID MEDPRAKTIKA–M, 2008. 136 p.

3. Fink P., Rosendal M., Olesen F. Classificatin of somatization and functional somatic symptoms in primary care.// Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;39(9):772–81

Classificatin of somatization and functional somatic symptoms in primary care.// Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2005 Sep;39(9):772–81

4. Oganov R.G., Olbinskaya L.I., Smulevich A.B., Drobizhev M.Yu., Shalnova S.A., Pogosova G.V. Depression and depressive spectrum disorders in general medical practice. Results of the KOMPAS program // Cardiology, 2004, No. 9, pp. 1–8

5. Smulevich A.B., Dubnitskaya E.B., Drobizhev M.Yu., Burlakov A.V., Makukh E.A., Gorbushin A.G. Depression and the possibilities of their treatment in general medical practice (preliminary results of the SAIL program)//Consilium of Medicine.–2007.–vol. 2.–No. 2.–Mental disorders in general medicine.–p.23–25

6. Stein MB, Kirk P, Prabhu V, Grott M, Terepa M. Mixed anxiety–depression in a primary–care clinic.//J Affect Disord. 1995 May 17;34(2):79–84

7. Katon W, Hollifield M, Chapman T et al. Infrequent panic attacks: psychiatric comorbidity, personal characterisitics and functional disability. J Psych Research 1995; 29:121–131

8. Broadhead W, Blazer D, George L, Tse C. Depression, disability days and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiological survey. JAMA 1990; 264:2524–8

Broadhead W, Blazer D, George L, Tse C. Depression, disability days and days lost from work in a prospective epidemiological survey. JAMA 1990; 264:2524–8

9. Vorobieva O.V. Clinical features of depression in general medical practice (according to the results of the KOMPAS program). Consilium Medicum 2004; 6:2:84-87

10. Sansone RA, Hendricks CM, Gaither GA, Reddington A. Prevalence of anxiety symptoms among a sample of outpatients in an internal medicine clinic. Depression and Anxiety 2004;19 (133–136

11. Page LA, Wessely S// J R Soc Med 2003; 96: 223–227 Medically unexplained symptoms: exacerbating factors in the doctor–patient encounter

12. van Dulmen AM, Fennis JF, Mokkink HG, van der Velden HG, Bleijenberg G. J Psychosom Res 1994;38:581 –90 Doctors’ perception of patients’ cognitions and complaints in irritable bowel syndrome at an out–patient clinic

13. Peters S, Stanley I, Rose M, Salmon P. Patients with medically unexplained symptoms: sources of patients’ authority and implications for demands on medical care // Soc Sci Med 1998; 46:559 –565

14. Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D, Carson A, Lewis S, MacKenzie L, Warlow CP, Sharpe M What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The “number needed to offend.”//BMJ 2002; 325:1449–1450

Stone J, Wojcik W, Durrance D, Carson A, Lewis S, MacKenzie L, Warlow CP, Sharpe M What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The “number needed to offend.”//BMJ 2002; 325:1449–1450

15. Chambers J, Bass C, Mayou R Heart 1999; 82: 656–657 Noncardiac chest pain

16. Arolt V, Rothermundt M. Depressive disorders with somatic illnesses//Nervenarzt. 2003 Nov;74(11):1033–52; quiz 1053–4

17. Sayar K, Kirmayer LJ, Taillefer SS. Predictors of somatic symptoms in depressive disorder// Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2003 Mar–Apr;25(2):108–14

18. Wittchen H–U, Carter RM, Pfister H, Montgomery SA, Kessler RC. Disabilities and quality of life in pure and comorbid generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in a national survey. //Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;15:319-28

19. Kessler RC, Stang P, Wittchen H–U, Stein MB, Walters EE. Lifetime comorbidities between social phobia and mood disorders in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med 1999;29:555–67

20. Goodwin R, Olfson M. Treatment of panic attack and risk of major depressive disorder in the community. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158: 1146–8

Goodwin R, Olfson M. Treatment of panic attack and risk of major depressive disorder in the community. Am J Psychiatry 2001;158: 1146–8

21. Mosolov S.N. Anxiety and depressive disorders: comorbidity and therapy. Artinfo Publishing, Moscow 2007

22. Zigmond A.S., Snaith R.P. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression scale/|| Acta Psychitr. Scand. 1983 – Vol.67 – P.361–370 Adapted by Drobizhev M.Yu., 1993

23. Appendix No. 1 to ORDER OF THE HEALTH COMMITTEE OF THE GOVERNMENT OF MOSCOW DATED 03.22.2000 N 110 “ON MOSCOW CITY STANDARDS OF CONSULTATIVE AND DIAGNOSTIC ASSISTANCE FOR ADULTS

24. Akarachkova E.S., Vorob'eva O.V., Filatova E.G., Artemenko A.R., Toropina G.G., Kurenkov A.L. Pathogenetic aspects of the treatment of chronic headaches. //Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. Korsakova, 2007, Issue 2, Practical neurology (supplement to the journal), p. 8–12

25. Akarachkova E.S., Drobizhev M.Yu., Vorobieva O.V., Makukh E.A. Nonspecific pain and depression in neurology // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. Korsakova, 2008 No. 12, pp. 4–10

Korsakova, 2008 No. 12, pp. 4–10

26. Solovieva A.D., Akarachkova E.S., Toropina G.G., Nedostup A.V. Pathogenetic aspects of the treatment of chronic cardialgia.//Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakova 2007; Vol. 107, No. 11:41–44

27. Damulin I.V. Features of depression in neurological diseases // Farmateka 2005; 17:25–34

28. Mashkovsky M.D. “Medications. In two parts. Part 1.–12th ed., Rev. and add.–M.: Medicine, 1993.–736 p.

29. Morozov P.V. Antidepressants in the practice of a polyclinic therapist//District therapist No. 5 / 2009 Consilium-Medicum

30. Akarachkova E.S., Shvarkov S.B., Shirshova E.V. Experience of outpatient use of the antidepressant Azafen in neurological patients.//Special issue Man and Medicine Farmateka No. 7(142), 2007, p.74–78

31. Tyuvina N.A., Prokhorova S.V., Kruk Ya.V. The effectiveness of Azafen in the treatment of a depressive episode of mild and moderate severity // Consilium-Medicum 2005; 4(7): 198–200

32. Shinaev N.N., Akzhigitov R.G. The return of azafen to clinical practice // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakova 2001; 10(101): 55–56

Shinaev N.N., Akzhigitov R.G. The return of azafen to clinical practice // Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakova 2001; 10(101): 55–56

Psycho-emotional disorders — School of Health — GBUZ City Polyclinic 25, Krasnodar MH KK

Depressive disorders

The prevalence of neurotic disorders in the European and North American population reaches 10-20%. Depressive disorders make a significant contribution to this indicator. 7-12% of men and 20-25% of women suffer from depression during their lifetime (Kay, 2000). One of the most common neurotic conditions is depression. Depression is a mental disorder characterized by a depressive triad: decreased mood, loss of the ability to experience joy (anhedonia), impaired thinking (negative judgments, pessimistic view of what is happening, etc.) and motor retardation. Depression affects 10% of the population over the age of 40, of which 2/3 are women. It is three times more common among people over 65 years of age. The risk of depression is highest in patients with cardiovascular diseases: among patients with coronary artery disease, their frequency is on average 20%, among hospitalized patients - more than 30%. In the acute period of myocardial infarction (MI), symptoms of depression are observed in 65% of patients, within 18-24 months after myocardial infarction - in every fourth. About 5% of patients who seek medical help suffer from depression, 15% of people with depression attempt suicide. Every eighth person in the population needs antidepressant treatment at least once in their life.

The risk of depression is highest in patients with cardiovascular diseases: among patients with coronary artery disease, their frequency is on average 20%, among hospitalized patients - more than 30%. In the acute period of myocardial infarction (MI), symptoms of depression are observed in 65% of patients, within 18-24 months after myocardial infarction - in every fourth. About 5% of patients who seek medical help suffer from depression, 15% of people with depression attempt suicide. Every eighth person in the population needs antidepressant treatment at least once in their life.

Depressive disorder begins when a person loses the taste for life, the ability to experience pleasure, there is a feeling of sadness and despair, the inability to act, sometimes there are suicidal thoughts. A person feels irritated, lonely, tired, insignificant, useless, at any moment can burst into tears for no reason. The world seems gray and empty, and one's own life is unhappy, self-esteem decreases. Often the first signs of depression, even before the patient realizes his condition, are sleep disturbances - difficulty falling asleep, accompanied by heavy thoughts, short, sensitive sleep, early awakenings (at 3-4 in the morning) and daytime sleepiness. Eating habits are also violated - a person begins to eat a lot or, on the contrary, loses his appetite.

Often the first signs of depression, even before the patient realizes his condition, are sleep disturbances - difficulty falling asleep, accompanied by heavy thoughts, short, sensitive sleep, early awakenings (at 3-4 in the morning) and daytime sleepiness. Eating habits are also violated - a person begins to eat a lot or, on the contrary, loses his appetite.

Currently, the problem of depression can be considered as a general medical problem, which is facilitated by the high comorbidity of depression with many somatic diseases, especially diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular pathologies (Whooley, 2006). Recently, a link has been established between depressive disorders and cardiovascular risk factors. Kinder et al. (2004) analyzed data from the third NHANES (National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey, 1988-1994), which included 3186 men and 3003 women aged 17-39. It turned out that women with a history of "major" depression were twice as likely to be diagnosed with the metabolic syndrome than among participants with an uncomplicated history of depression. Among women, depression was often associated with increased blood pressure (BP) and hypertriglyceridemia, as well as a trend towards lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and an increase in waist circumference. Atherosclerotic lesions of the common carotid artery are more pronounced and progress faster in pessimistic women (Matthews, 2004). Possible mechanisms of the relationship between depression and cardiovascular risk factors are disorders of the autonomic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation, increased levels of inflammation and hemostasis markers, as well as a tendency to an unhealthy lifestyle (smoking, unbalanced diet). Insulin resistance also contributes to a decrease in serotonergic activity in the central nervous system, which leads to the development of depressive disorders (Pirkola et al., 2005). An analysis of the frequency of depressive disorders in a population of people with three cardiovascular risk factors showed the presence of depression in 61.

Among women, depression was often associated with increased blood pressure (BP) and hypertriglyceridemia, as well as a trend towards lower high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and an increase in waist circumference. Atherosclerotic lesions of the common carotid artery are more pronounced and progress faster in pessimistic women (Matthews, 2004). Possible mechanisms of the relationship between depression and cardiovascular risk factors are disorders of the autonomic nervous system, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal regulation, increased levels of inflammation and hemostasis markers, as well as a tendency to an unhealthy lifestyle (smoking, unbalanced diet). Insulin resistance also contributes to a decrease in serotonergic activity in the central nervous system, which leads to the development of depressive disorders (Pirkola et al., 2005). An analysis of the frequency of depressive disorders in a population of people with three cardiovascular risk factors showed the presence of depression in 61. 5%, which is significantly higher than in the general population (Skilton et al., 2007). One of the main pathological processes in depressive disorders is the imbalance of the autonomic nervous system with the activation of the sympathetic division. In patients with depression, the level of intracellular free calcium, hyperproduction of platelet factor IV and b-thromboglobulin are increased, which contributes to more active platelet aggregation (Ozdoeva, 2003). In persons with depression, endothelial function is impaired, which affects the regulation of vascular tone, sensitivity to norepinephrine and acetylcholine, and a tendency to hemocoagulation (Omelyanenko, 2002). Pathophysiological changes in the body in depressive disorder lead to the fact that despondency and pessimism increase overall mortality by 19% (Bobryshev, 2012).

5%, which is significantly higher than in the general population (Skilton et al., 2007). One of the main pathological processes in depressive disorders is the imbalance of the autonomic nervous system with the activation of the sympathetic division. In patients with depression, the level of intracellular free calcium, hyperproduction of platelet factor IV and b-thromboglobulin are increased, which contributes to more active platelet aggregation (Ozdoeva, 2003). In persons with depression, endothelial function is impaired, which affects the regulation of vascular tone, sensitivity to norepinephrine and acetylcholine, and a tendency to hemocoagulation (Omelyanenko, 2002). Pathophysiological changes in the body in depressive disorder lead to the fact that despondency and pessimism increase overall mortality by 19% (Bobryshev, 2012).

Chronically elevated levels of cortisol and noradrenaline are an important mechanism of the pathogenetic relationship between depression and cardiovascular disease.

In the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with depression, the content of corticotropin-releasing factor, produced in the hypothalamus, is increased, which stimulates the release of adrenocorticotropic hormone in the anterior pituitary gland, which leads to stimulation of the release of glucocorticoids (cortisol) from the cortex and catecholamines (norepinephrine) from the adrenal medulla ( Vasyuk, Lebedev, 2007). Such a humoral reaction is accompanied by an increase in vascular tone, an increase in heart rate (HR), and increased platelet aggregation. In post-MI patients, such changes can significantly affect prognosis.

Along with an increase in cardiovascular risk, depression is also associated with cognitive decline, which is especially important in elderly and senile patients. Depression is associated with general lethargy in the elderly, and its manifestations can be hidden behind signs of cognitive decline, exacerbating them.

S.A. Malyarov cites data that 2025% of patients with pathological changes in the coronary vessels, confirmed by coronary angiography, had signs of depression sufficient to diagnose an affective disorder. This may indicate a role for depression in the progression of atherosclerosis. It should be taken into account that autonomic disorder (sympathoadrenal activation, increased heart rate, platelet aggregation) against the background of depression in such patients can be a triggering factor for acute coronary syndrome. In a study by R.M. Carney (19)87) showed that comorbid depression was an independent predictor of cardiac events within a year after coronary angiography.

Depression is not only associated with a higher level of cardiovascular risk (greater frequency and severity of risk factors), but also has a high comorbidity with cardiovascular disease. It has been shown that 17-27% of patients with coronary artery disease undergoing coronary angiography have depression, and in patients in the post-infarction period they are found in 16-45% of cases.