Becoming mentally tough

How to Make Yourself Mentally Strong This Year - Lolly Daskal

In business, there are times when you need to be mentally acute to make tough decisions.

In leadership, there are times when you need to be mentally tough to navigate through complex information.

In life, there are times when you need to be mentally sharp, to make good decisions fast.

In those times you need to be mentally strong. That means managing your emotions, adjusting your thinking, and choosing to take positive action whatever your circumstances.

But like any physical strength, mental strength doesn’t just happen. It has to be developed.

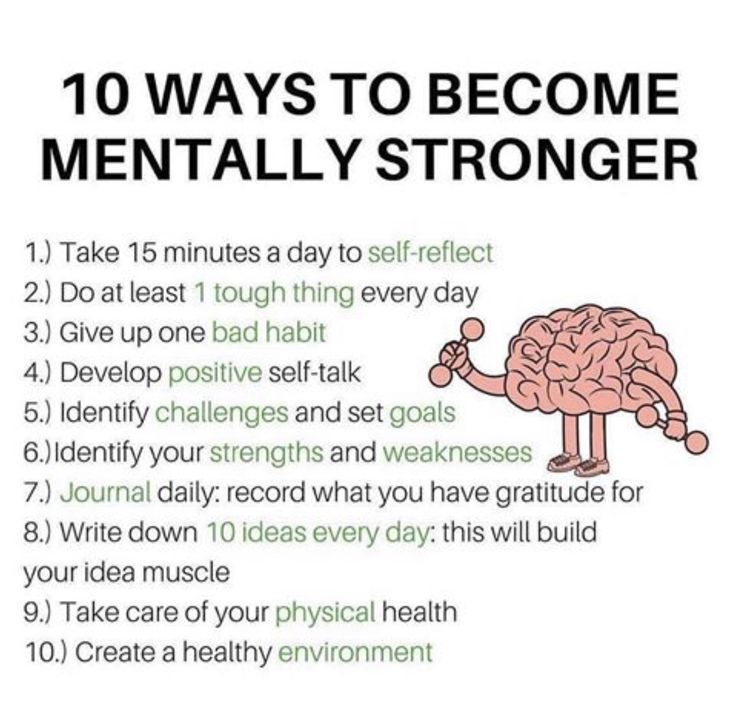

Here are 15 effective ways to become more mentally strong:

1. Focus on the moment. The challenges that come along from time to time are a test of our willingness to stretch and change. The worst thing you can do is to ignore the situation or procrastinate in developing solutions. The challenge is here and the difficulty is now.

Focus your energy on the present moment; don’t lose what is right before you. When you focus on the moment you come to realize where you have the most power to make things right.

2. Embrace adversity. Mental strength gives us the ability to see the obstacles in our path as stepping stones. When we encounter struggle, and we all do, we can be inspired by the knowledge that it’s not a dead end but a path to deeper knowledge and understanding.

3. Exercise your mind. Just like your muscles, your mind needs to be exercised to gain strength. Growth and development take consistent work, and if you have not pushed yourself recently, you might not be growing as much as you can. Mental strength is built through lots of small wins, maintained through the choices we make every day. To gain stamina, take on a daily task that stretches your mental endurance.

4. Challenge yourself. Albert Einstein once said, “One should not pursue goals that are easily achieved. One must develop an instinct for what one can just barely achieve through one’s greatest efforts.” Underestimating yourself and playing it safe hold you back from success. When you believe in yourself and your abilities, you often can go beyond the imaginable.

One must develop an instinct for what one can just barely achieve through one’s greatest efforts.” Underestimating yourself and playing it safe hold you back from success. When you believe in yourself and your abilities, you often can go beyond the imaginable.

5. Respond positively. You cannot control everything that comes your way, but you are in absolute control of how you react to everything that comes your way. What happens to you is important–but not as important as your response. Incredible progress can happen in your life and leadership when you take control of your reactions.

6. Be mindful. Mindfulness means taking control of your focus and being intentional about what you give your attention to. Whether it’s an emotion, a thought, a belief, an impulse, or something in the environment, mindfulness calls us to approaching everything with a curious, nonjudgmental, open, and accepting attitude. To be the most resilient and mentally strong, make the time to be mindful so you can focus on what you truly want.

7. Don’t be defeated by fear. To be resilient and mentally strong means knowing how to deal with fear. When you enter frightening situations with the awareness that it’s an opportunity for you to grow, trust outweighs fear.

8. Be aware of self-talk. We’re often so busy worrying about how we talk to others that we sometimes lose track of the way we talk to ourselves. Make a point of being as positive and supportive of yourself as you are of others, because when times get tough you have to be able to believe you can make it through. Replace self-doubt with positivity.

9. Rid yourself of can’t. When you feel like you can’t do something, keep your focus positive. You just have to do it. The mentally strong weed out the words like can’t, never, and should–replacing them with can, could, and when.

10. Stumble toward success. Winston Churchill once said, “Success is stumbling from failure to failure with no loss of enthusiasm. ” Perseverance gives you the ability to face any difficulty, any challenge, any setback without being defeated. It’s better to have a lifetime full of small failures that you learned from rather than one filled with the regret of never having tried.

” Perseverance gives you the ability to face any difficulty, any challenge, any setback without being defeated. It’s better to have a lifetime full of small failures that you learned from rather than one filled with the regret of never having tried.

11. Find solutions. There will be always problems– every business has complications and any endeavor has hurdles, but if you can learn to focus 90 percent of your time on solutions and only 10 percent on problems, you’ll be able to respond effectively instead of spinning your wheels.

12. Be grateful. In the business of our busy lives we neglect many of the basic concept of recognition but gratitude gives us fortitude. Gratitude can transform any common day into a thanks giving day and turn routine jobs onto joy and change ordinary opportunities into something we get grateful about.

13. Brace yourself for the storms. Adversity is inevitable. Be as well-prepared as you can so you can fight them with strength and push through to blue skies.

14. Define your moments. When you find yourself doubting how far you can go, remember how far you have come. Give yourself credit for everything you have faced, for the battles you have won, for the fears you’ve overcome.

15. Make it an everyday pursuit. Most mental strength is built and demonstrated not in exceptional circumstances but in the day-to-day of life and leadership.

Positivity, preparation, willingness, discipline, focus, and a long view will all serve you well. Practice mental toughness and you’ll soon be amazed at how strong you’ve become.

N A T I O N A L B E S T S E L L E R

What Gets Between You and Your GreatnessAfter decades of coaching powerful executives around the world, Lolly Daskal has observed that leaders rise to their positions relying on a specific set of values and traits. But in time, every executive reaches a point when their performance suffers and failure persists. Very few understand why or how to prevent it.

Very few understand why or how to prevent it.

buy now

Additional Reading you might enjoy:

- 12 Successful Leadership Principles That Never Grow Old

- A Leadership Manifesto: A Guide To Greatness

- How to Succeed as A New Leader

- 12 of The Most Common Lies Leaders Tell Themselves

- 4 Proven Reasons Why Intuitive Leaders Make Great Leaders

- The One Quality Every Leader Needs To Succeed

- The Deception Trap of Leadership

Photo Credit: Getty Images

Lolly Daskal is one of the most sought-after executive leadership coaches in the world. Her extensive cross-cultural expertise spans 14 countries, six languages and hundreds of companies. As founder and CEO of Lead From Within, her proprietary leadership program is engineered to be a catalyst for leaders who want to enhance performance and make a meaningful difference in their companies, their lives, and the world.

Of Lolly’s many awards and accolades, Lolly was designated a Top-50 Leadership and Management Expert by Inc. magazine. Huffington Post honored Lolly with the title of The Most Inspiring Woman in the World. Her writing has appeared in HBR, Inc.com, Fast Company (Ask The Expert), Huffington Post, and Psychology Today, and others. Her newest book, The Leadership Gap: What Gets Between You and Your Greatness has become a national bestseller.

14 Ways to Build Mental Toughness

How resilient are you?

Some people seem to quickly bounce back from personal failures and setbacks, while others find it much more difficult.

When life knocks you down, are you quick to pick yourself up and adapt to the circumstances? Or do you find yourself completely overwhelmed with little confidence in your ability to deal with the challenge?

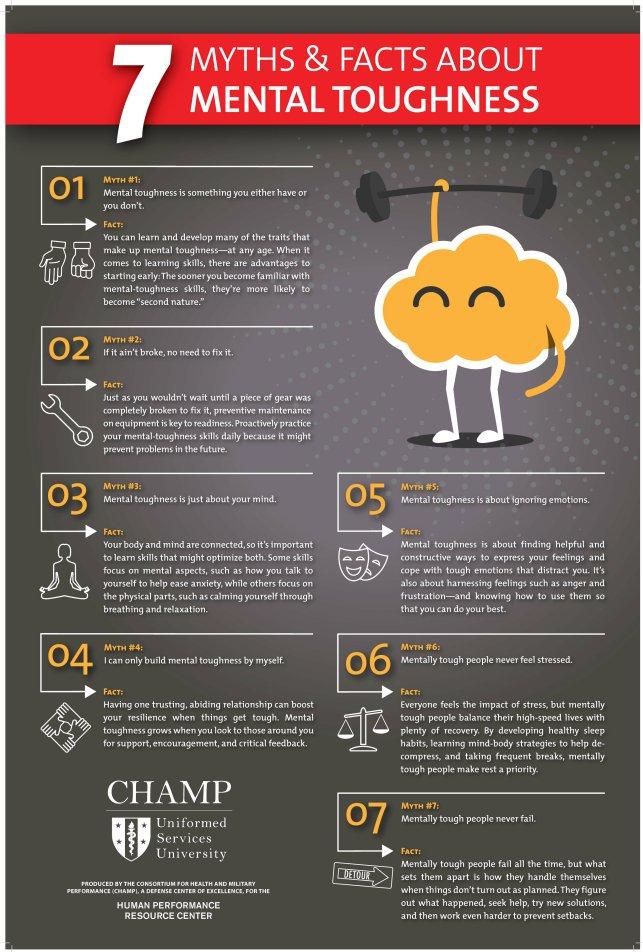

If you find yourself in the latter category, not to worry. Luckily there are many practical strategies for building mental resilience; it is a quality that can be learned and honed through practice, discipline and hard work.

Luckily there are many practical strategies for building mental resilience; it is a quality that can be learned and honed through practice, discipline and hard work.

Our resilience is often tested when life circumstances change unexpectedly and for the worse — such as the death of a loved one, the loss of a job, or the end of a relationship. Such challenges, however, present the opportunity to rise above and come back even stronger than you were before.

Read on to learn techniques to build and improve your mental resilience, and deal effectively with the challenges of life.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our 3 Resilience Exercises for free. These engaging, science-based exercises will help you to effectively deal with difficult circumstances and give you the tools to improve the resilience of your clients, students or employees.

This Article Contains:

- How to Be Mentally Strong

- On Building Resilience and Mental Toughness

- How to Build Resilience in Adults

- Increase Mental Strength in Students

- 14 Ways to Build and Improve Resilience

- The Road to Resilience (APA)

- The Resilience Builder Program

- The Realizing Resilience Masterclass

- Improving Mental Stamina

- Enhancing Resilience in the Community

- What Builds Resilient Relationships?

- How Do People Learn to Become Resilient for Life?

- Case Study Showing Ways to Build Resilience

- How to Get a Better, Stronger and More Confident Mind

- 3 YouTube Videos on How to Be Mentally Strong

- A Take-Home Message

- References

How to Be Mentally Strong

Mental Strength is the capacity of an individual to deal effectively with stressors, pressures and challenges and perform to the best of their ability, irrespective of the circumstances in which they find themselves (Clough, 2002).

Building mental strength is fundamental to living your best life. Just as we go to the gym and lift weights in order to build our physical muscles, we must also develop our mental health through the use of mental tools and techniques.

Optimal mental health helps us to live a life that we love, have meaningful social connections, and positive self-esteem. It also aids in our ability to take risks, try new things, and cope with any difficult situations that life may throw at us.

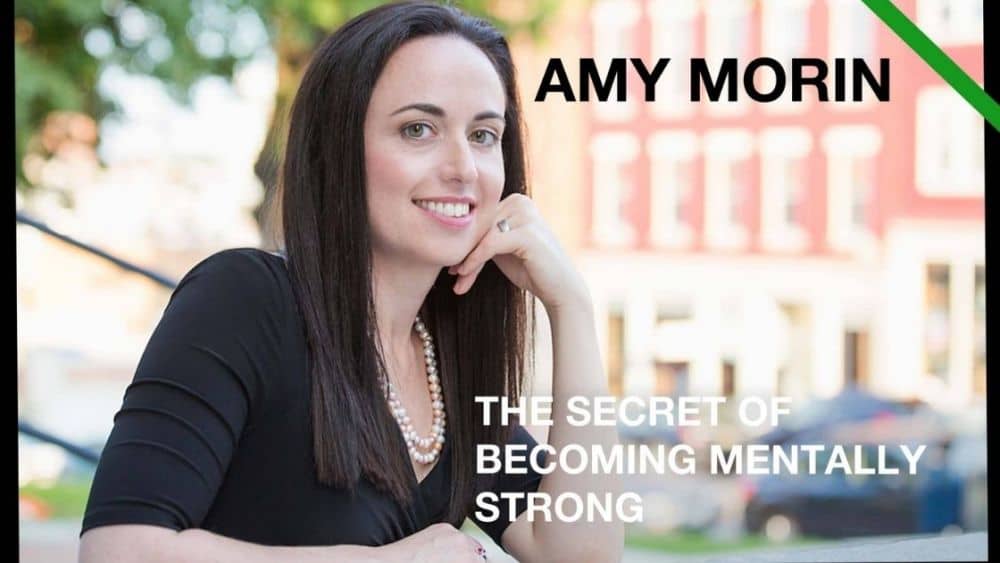

Mental strength involves developing daily habits that build mental muscle. It also involves giving up bad habits that hold you back.

Morin, 2017

In order to be mentally healthy, we must build up our mental strength! Mental strength is something that is developed over time by individuals who choose to make personal development a priority. Much like seeing physical gains from working out and eating healthier, we must develop healthy mental habits, like practicing gratitude, if we want to experience mental health gains.

Likewise, to see physical gains we must also give up unhealthy habits, such as eating junk food, and for mental gains, give up unhealthy habits such as feeling sorry for oneself.

We are all able to become mentally stronger, the key is to keep practicing and exercising your mental muscles — just as you would if you were trying to build physical strength!

On Building Resilience and Mental Toughness

The term “Resilience,” commonly used in relation to positive mental health, is actually borrowed from engineering, where it refers to the ability of a substance or object to spring back into shape (“Resilience,” 2019). In the same way that a material object would require strength and flexibility in order to bounce back, so too does an individual require these characteristics in order to be mentally resilient.

The American Psychological Association (2014) defines Mental Resilience as:

“The process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or even significant sources of stress.

”

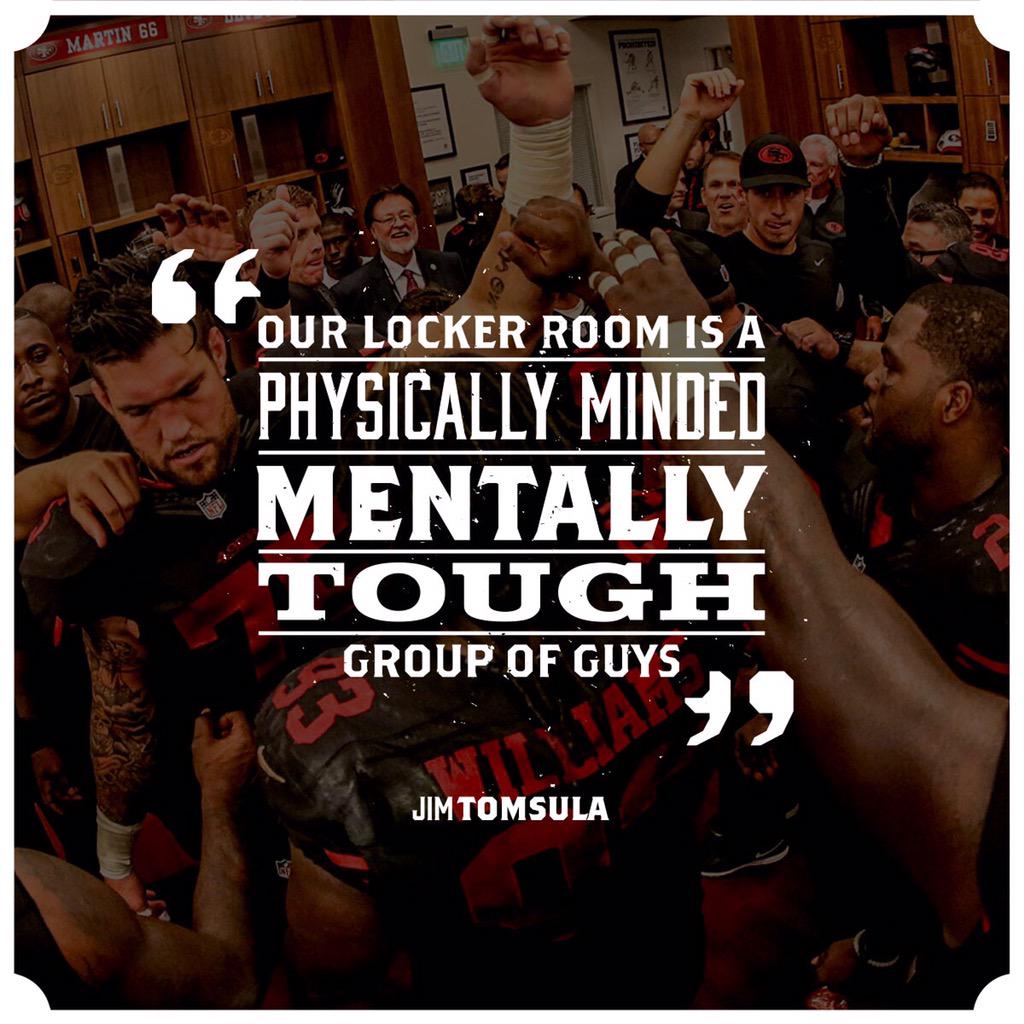

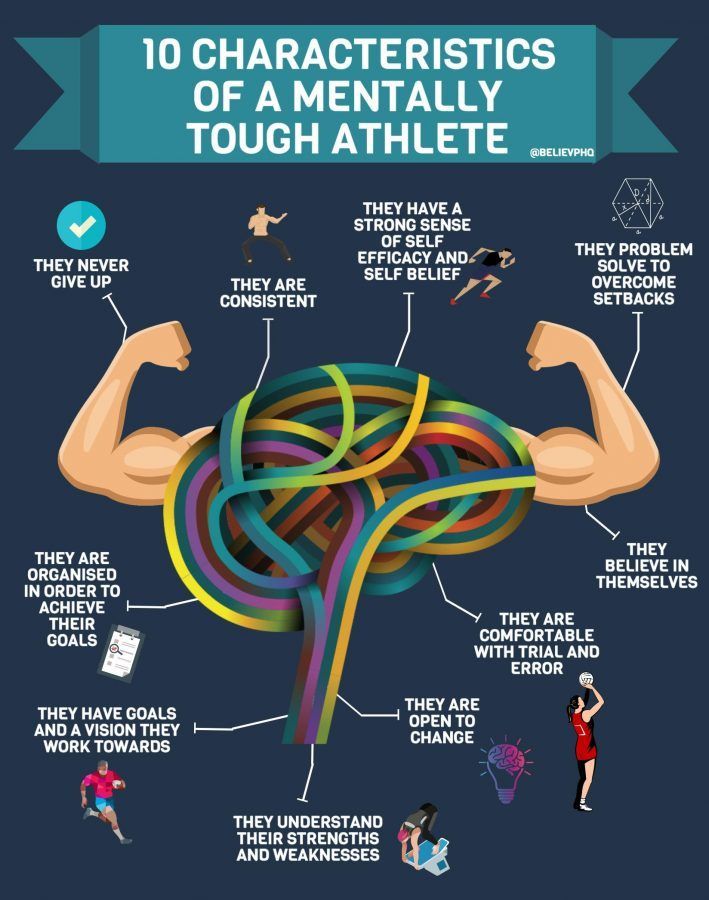

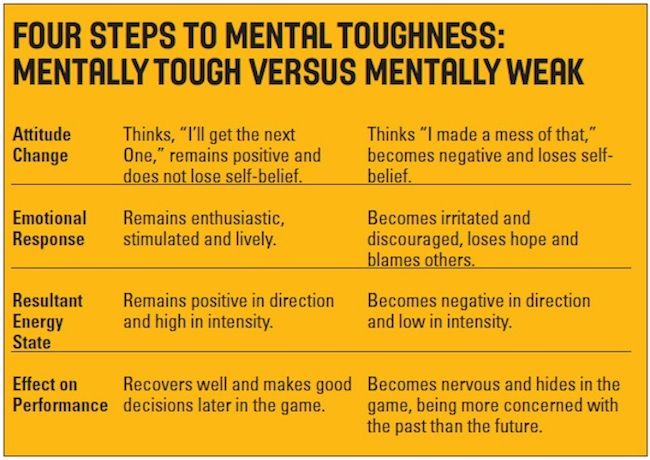

A similar concept, Mental Toughness, refers to the ability to stay strong in the face of adversity; to keep your focus and determination despite the difficulties you encounter. A mentally tough individual sees challenge and adversity as an opportunity and not a threat, and has the confidence and positive approach to take what comes in their stride (Strycharczyk, 2015).

To be mentally tough, you must have some degree of resilience, but not all resilient individuals are necessarily mentally tough. If you think of it as a metaphor, resilience would be the mountain, while mental toughness might be one of the strategies for climbing that mountain.

Strycharczyk (2015) finds it useful to think of the difference in terms of the phrase ‘survive and prosper.’ Resilience helps you to survive, and mental toughness helps you to prosper.

Mental toughness begins when you choose to take notice of what’s passing through your mind, without identifying personally with those thoughts or feelings. Then, finding the determination to evoke optimistic thoughts about the situation at hand.

Then, finding the determination to evoke optimistic thoughts about the situation at hand.

According to Strycharczyk and Cloughe (n.d.), techniques for developing mental toughness revolve around five themes:

- Positive Thinking

- Anxiety Control

- Visualization

- Goal Setting

- Attentional Control

As with building mental strength, developing mental toughness does require self-awareness and commitment. Generally speaking, mentally tough individuals appear to achieve more than the mentally sensitive and enjoy a greater degree of contentment.

Turner (2017) describes four important traits of mental toughness, which he calls the 4C’s: Control, Commitment, Challenge, and Confidence. One may possess a few of these traits, but having the four qualities in combination is the key to success.

Mental toughness can be measured using the MTQ48 Psychometric Tool, constructed by Professor Peter Clough of Manchester Metropolitan University. The MTQ48 Tool is scientifically valid and reliable and based on this 4C’s framework, which measures key components of mental toughness.

The MTQ48 Tool is scientifically valid and reliable and based on this 4C’s framework, which measures key components of mental toughness.

The 4 C’s of Mental Toughness: (Turner, 2017)

1. Control

This is the extent to which you feel you are in control of your life, including your emotions and sense of life purpose. The control component can be considered your self-esteem. To be high on the Control scale means to feel comfortable in your own skin and have a good sense of who you are.

You’re able to control your emotions — less likely to reveal your emotional state to others — and be less distracted by the emotions of others. To be low on the Control scale means you might feel like events happen to you and that you have no control or influence over what happens.

2. Commitment

This is the extent of your personal focus and reliability. To be high on the Commitment scale is to be able to effectively set goals and consistently achieve them, without getting distracted. A high Commitment level indicates that you’re good at establishing routines and habits that cultivate success.

A high Commitment level indicates that you’re good at establishing routines and habits that cultivate success.

To be low on the Commitment scale indicates that you may find it difficult to set and prioritize goals, or adapt routines or habits indicative of success. You might also be easily distracted by other people or competing priorities.

Together, the Control and Commitment scales represent the Resilience part of the Mental Toughness definition. This makes sense because the ability to bounce back from setbacks requires a sense of knowing that you are in control of your life and can make a change. It also requires focus and the ability to establish habits and targets that will get you back on track to your chosen path.

3. Challenge

This is the extent to which you are driven and adaptable. To be high on the Challenge scale means that you are driven to achieve your personal best, and you see challenges, change, and adversity as opportunities rather than threats; you are likely to be flexible and agile. To be low on the Challenge scale means that you might see change as a threat, and avoid novel or challenging situations out of fear of failure.

To be low on the Challenge scale means that you might see change as a threat, and avoid novel or challenging situations out of fear of failure.

4. Confidence

This is the extent to which you believe in your ability to be productive and capable; it is your self-belief and the belief that you can influence others. To be high on the Confidence scale is to believe that you will successfully complete tasks, and to take setbacks in stride while maintaining routine and even strengthening your resolve. To be low on the

Confidence scale means that you are easily unsettled by setbacks, and do not believe that you are capable or have any influence over others.

Together, the Challenge and Confidence scales represent the Confidence part of the Mental Toughness definition. This represents one’s ability to identify and seize an opportunity, and to see situations as opportunities to embrace and explore. This makes sense because if you are confident in yourself and your abilities and engage easily with others, you are more likely to convert challenges into successful outcomes.

How to Build Resilience in Adults

As mentioned earlier, mental resilience is not a trait that people either have or don’t have. Rather, it involves behaviors, thoughts, and actions that can be learned and developed in everyone. Of course, there may be a genetic component to a person’s level of mental resilience, but it is certainly something that can be built upon.

In a paper inspired by the 2013 panel of the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies, Drs. Southwick, Bonanno, Masten, Panter-Brick, and Yehuda (2013) tackled some of the most pressing current questions in the field of resilience research.

The panelists had slightly different definitions of resilience, but most of the definitions included a concept of healthy, adaptive, positive functioning in the aftermath of adversity. They agreed that “resilience is a complex construct and it may be defined differently in the context of individuals, families, organizations, societies, and cultures. ”

”

There was also a consensus that one’s ability to develop resilience is based on many factors, including genetic, developmental, demographic, cultural, economic, and social variables; but that resilience can be cultivated, nonetheless (Southwick et al., 2013).

Simply put, resilience can be cultivated through will-power, discipline, and hard work; and there are many strategies by which to do so. The key is to identify ways that are likely to work well for you as part of your own personal strategy for cultivating resilience.

Increase Mental Strength in Students

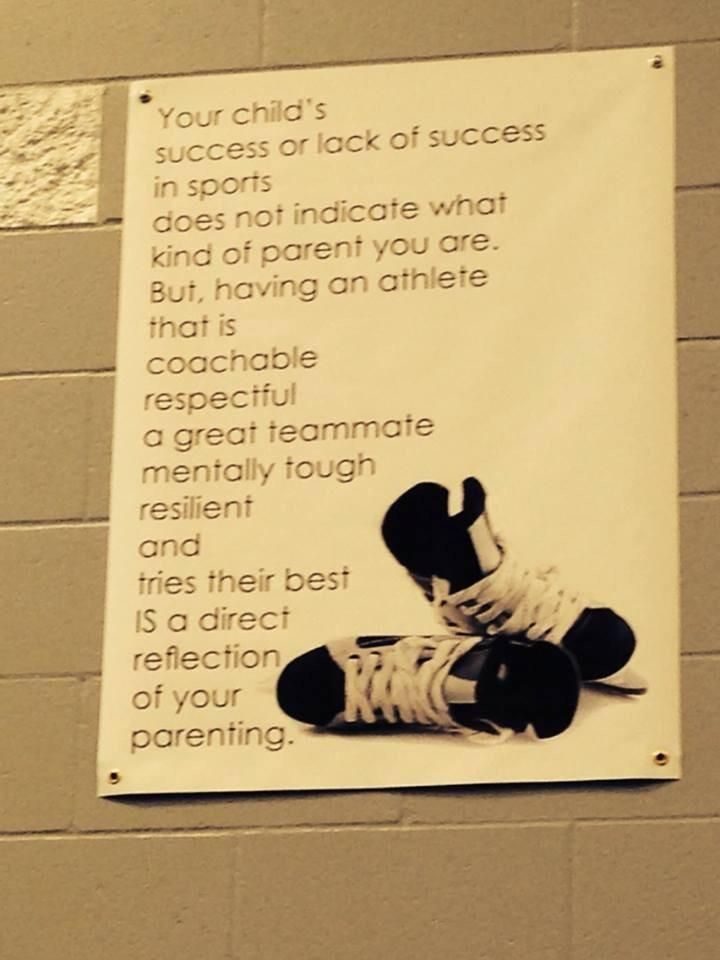

Just like adults, mentally strong children and adolescents are able to tackle problems, bounce back from failure, and cope with life’s challenges and hardships. They are resilient and have the courage and confidence to reach their full potential.

Developing mental strength in students is just as important, if not more important, as developing mental strength in adults. According to Morin (2018), helping kids develop mental strength requires a three-pronged approach, teaching them how to:

- Replace negative thoughts with positive, more realistic thoughts

- Control their emotions so their emotions don’t control them

- Take positive action.

Though there are many strategies, discipline techniques, and teaching tools that help children to build their mental muscle, here are 10 strategies to help students develop the strength they need to become a mentally strong adult:

1. Teach Specific Skills

Rather than making kids suffer for their mistakes, discipline should be about teaching kids how to do better next time. Instead of punishment, use consequences that teach useful skills, such as problem-solving and impulse control.

2. Let Your Child Make Mistakes

Mistakes are an inevitable part of life and learning. Teach your child or student that this is so and that they shouldn’t be embarrassed or ashamed about getting something wrong.

3. Teach Your Child How to Develop Healthy Self-Talk

It’s important to help children develop a realistic and optimistic outlook on life, and how to reframe negative thoughts when they arise. Learning this skill early in life will help them persevere through difficult times.

4. Encourage Your Child to Face Fears Head-On

Enabling a child to face their fears head-on will help them gain invaluable confidence. One way to do this is to teach your child to step outside of their comfort zone and face their fears one small step at a time while praising and rewarding their efforts.

5. Allow Your Child to Feel Uncomfortable

It can be tempting to soothe or rescue your child or student whenever they are struggling, but it’s important to allow them to sometimes lose or struggle, and insist that they are responsible even when they don’t want to be. Dealing with small struggles on their own can help children to build their mental strength.

6. Build Character

Children with a strong moral compass and value system will be better able to make healthy decisions. You can help by instilling values such as honesty and compassion, and creating learning opportunities that reinforce these values, regularly.

7. Make Gratitude a Priority

Practicing gratitude is one of the greatest things you can do for your mental health, and it’s no different for children (for more, see our Gratitute Tree for Kids. ) Gratitude helps us to keep things in perspective, even during the most challenging times. To raise a mentally strong child you should encourage them to practice gratitude on a regular basis.

) Gratitude helps us to keep things in perspective, even during the most challenging times. To raise a mentally strong child you should encourage them to practice gratitude on a regular basis.

8. Affirm Personal Responsibility

Accepting responsibility for your actions or mistakes is also part of building mental strength involves. If your student is trying to blame others for the way he/she thinks, feels or behaves, simply steer them away from excuses and allow for explanations.

9. Teach Emotion Regulation Skills

Instead of soothing or calming down your child every time they are upset, teach them how to deal with uncomfortable emotions on their own so that they don’t grow up depending on you to regulate their mood. Children who understand their range of feelings (see the Emotion Wheel) and have experience dealing with them are better prepared to deal with the ups and downs of life.

10. Be A Role Model for Mental Strength

There’s no better way to teach a child than by example. To encourage mental strength in your students or children, you must demonstrate mental strength. Show them that you make self-improvement a priority in your life, and talk about your goals and steps you take to grow stronger.

To encourage mental strength in your students or children, you must demonstrate mental strength. Show them that you make self-improvement a priority in your life, and talk about your goals and steps you take to grow stronger.

14 Ways to Build and Improve Resilience

As we’ve learned, your level of mental resilience is not something that is decided upon at birth — it can be improved over the course of an individual’s life. Below we will explore a number of different strategies and techniques used to improve mental resilience.

Rob Whitley, Ph.D. (2018), suggests three resilience-enhancing strategies:

1. Skill Acquisition

Acquiring new skills can play an important part in building resilience, as it helps to develop a sense of mastery and competency — both of which can be utilized during challenging times, as well as increase one’s self-esteem and ability to problem solve.

Skills to be learned will depend on the individual. For example, some might benefit from improving cognitive skills such as working memory or selective attention, which will help with everyday functioning. Others might benefit from learning new hobbies activities through competency-based learning.

Others might benefit from learning new hobbies activities through competency-based learning.

Acquiring new skills within a group setting gives the added benefit of social support, which also cultivates resilience.

2. Goal Setting

The ability to develop goals, actionable steps to achieve those goals, and to execute, all help to develop will-power and mental resilience. Goals can be large or small, related to physical health, emotional wellbeing, career, finance, spirituality, or just about anything. Goals that involve skill-acquisition will have a double benefit. For example, learning to play an instrument or learning a new language.

Some research indicates that setting and working towards goals beyond the individual, i.e. religious involvement or volunteering for a cause, can be especially useful in building resiliency. This may provide a deeper sense of purpose and connection, which can be valuable during challenging times.

3. Controlled Exposure

Controlled exposure refers to the gradual exposure to anxiety-provoking situations, and is used to help individuals overcome their fears. Research indicates that this can foster resilience, and especially so when it involves skill-acquisition and goal setting — a triple benefit.

Research indicates that this can foster resilience, and especially so when it involves skill-acquisition and goal setting — a triple benefit.

Public speaking, for example, is a useful life skill but also something that evokes fear in many people. People who are afraid of public speaking can set goals involving controlled exposure, in order to develop or acquire this particular skill. They can expose themselves to a small audience of one or two people, and progressively increase their audience size over time.

This type of action plan can be initiated by the individual, or it can be developed with a therapist trained in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. Successful efforts can increase self-esteem and a sense of autonomy and mastery, all of which can be utilized in times of adversity.

11 Further Strategies From The APA

The American Psychology Association (“Road to Resilience,” n.d.) shares 11 strategies for building mental resilience:

1. Make connections.

Resilience can be strengthened through our connection to family, friends, and community. Healthy relationships with people who care about you and will listen to your problems, offer support during difficult times and can help us to reclaim hope. Likewise, assisting others in their time of need can benefit us greatly and foster our own sense of resilience.

Healthy relationships with people who care about you and will listen to your problems, offer support during difficult times and can help us to reclaim hope. Likewise, assisting others in their time of need can benefit us greatly and foster our own sense of resilience.

2. Avoid seeing crises as insurmountable problems.

We cannot change the external events happening around us, but we can control our reaction to these events. In life, there will always be challenges, but it’s important to look beyond whatever stressful situation you are faced with, and remember that circumstances will change. Take notice of the subtle ways in which you may already start feeling better as you deal with the difficult situation.

3. Accept that change is a part of living.

They say that the only thing constant in life is change. As a result of difficult circumstances, certain goals may no longer be realistic or attainable. By accepting that which you cannot change, it allows you to focus on the things that you do have control over.

4. Move toward your goals. (*also suggested by Whitley, 2018)

Though it is important to develop long-term, big-picture goals, it is essential to make sure they’re realistic. Creating small, actionable steps makes our goals achievable, and helps us to regularly work towards these goals, creating small “wins” along the way. Try to accomplish one small step towards your goal every day.

5. Take decisive actions.

Instead of shying away from problems and stresses, wishing they would just go away, try to take decisive action whenever possible.

6. Look for opportunities for self-discovery.

Sometimes tragedy can result in great learnings and personal growth. Living through a difficult situation can increase our self-confidence and sense of self-worth, strengthen our relationships, and teach us a great deal about ourselves. Many people who have experienced hardship have also reported a heightened appreciation for life and deepened spirituality.

7.

Nurture a positive view of yourself.

Nurture a positive view of yourself.Working to develop confidence in yourself can be beneficial in preventing difficulties, as well as building resilience. Having a positive view of yourself is crucial when it comes to problem-solving and trusting your own instincts.

8. Keep things in perspective.

When times get tough, always remember that things could be worse; try to avoid blowing things out of proportion. In cultivating resilience it helps to keep a long-term perspective when facing difficult or painful events.

9. Maintain a hopeful outlook.

When we focus on what is negative about a situation and remain in a fearful state, we are less likely to find a solution. Try to maintain a hopeful, optimistic outlook, and expect a positive outcome instead of a negative one. Visualization can be a helpful technique in this respect.

10. Take care of yourself.

Self-care is an essential strategy for building resilience and helps to keep your mind and body healthy enough to deal with difficult situations as they arise. Taking care of yourself means paying attention to your own needs and feelings, and engaging in activities that bring you joy and relaxation. Regular physical exercise is also a great form of self-care.

Taking care of yourself means paying attention to your own needs and feelings, and engaging in activities that bring you joy and relaxation. Regular physical exercise is also a great form of self-care.

11. Additional ways of strengthening resilience may be helpful.

Resilience building can look like different things to different people. Journaling, practicing gratitude, meditation, and other spiritual practices help some people to restore hope and strengthen their resolve.

The Road to Resilience (APA)

The American Psychological Association (2014) defines resilience as the process of adapting well in the face of adversity, trauma, tragedy, threats or significant sources of stress — such as family and relationship problems, serious health problems or workplace and financial stressors. In other words, “bouncing back” from difficult experiences. Resilience is not a trait that people either have or do not have.

It involves behaviors, thoughts, and actions that can be learned and developed in anyone.

Research has shown that resilience is ordinary, not extraordinary and that people commonly demonstrate resilience. A good example of this is the response of many Americans to the September 11 2001, terrorist attacks, and individuals’ efforts to rebuild their lives.

According to the APA, being resilient does not mean that a person doesn’t experience hardships or adversities. In fact, a considerable amount of emotional distress is common in people who have dealt with difficulties and trauma in their lives.

Factors in Resilience

Many factors contribute to resilience, but studies have shown that the primary factor is having supportive relationships within and outside of the family. Relationships that are caring, loving, and offer encouragement and reassurance, help cultivate a person’s resilience.

The APA suggests several additional factors that are associated with resilience, including:

- The capacity to make realistic plans and actionable steps to carry them out.

- A positive self-view and confidence in your strengths and abilities.

- Communication and problem-solving skills.

- The capacity to manage and regulate strong feelings and impulses.

All of these are factors that people can develop within themselves.

Strategies For Building Resilience

When it comes to developing resilience, strategies will vary between each individual. We all react differently to traumatic and stressful life events, so an approach that works well for one person might not work for another. For example, some variation as to how one might communicate feelings and deal with adversity may reflect cultural differences, etc.

Learning from your Past

Taking a look at past experiences and sources of personal strength may provide insight as to which resilience building strategies will work for you. Below are some guiding questions from the American Psychology Association, that you can ask yourself about how you’ve reacted to challenging situations in the past. Exploring the answers to these questions can help you develop future strategies.

Exploring the answers to these questions can help you develop future strategies.

Consider the following:

- What types of events have been most stressful for me?

- How have those events typically affected me?

- Have I found it helpful to think of important people in my life when I am distressed?

- To whom have I reached out for support in working through a traumatic or stressful experience?

- What have I learned about myself and my interactions with others during difficult times?

- Has it been helpful for me to assist someone else going through a similar experience?

- Have I been able to overcome obstacles, and if so, how?

- What has helped make me feel more hopeful about the future?

Staying Flexible

A resilient mindset is a flexible mindset. As you encounter stressful circumstances and events in your life, it is helpful to maintain flexibility and balance in the following ways:

- Let yourself experience strong emotions, and realize when you may need to put them aside in order to continue functioning.

- Step forward and take action to deal with your problems and meet the demands of daily living; but also know when to step back and rest/reenergize yourself.

- Spend time with loved ones who offer support and encouragement; nurture yourself.

- Rely on others, but also know when to rely on yourself.

Places to Look for Help

Sometimes the support of family and friends is just not enough. Know when to seek help outside of your circle. People often find it helpful to turn to:

- Self-help and community support groups

Sharing experiences, emotions, information and ideas can provide great comfort to those who may feel like they’re alone during difficult times. - Books and other publications

Hearing from others who have successfully navigated adverse situations like the one you’re going through, can provide great motivation and inspiration for developing a personal strategy. - Online resources

There is a wealth of resources and information on the web about dealing with trauma and stress; just be sure the information is coming from a reputable source.

- A licensed mental health professional

For many, the above suggestions may be sufficient to cultivate resilience, but sometimes it’s best to seek professional help if you feel like you are unable to function in your daily life, as a result of traumatic or other stressful life events.

Continuing on your Journey

To help summarize the APA’s main points, a useful metaphor for resilience involves taking a journey on a kayak. On a rafting trip, you can encounter all kinds of different waters — rapids, slow water, shallow water and all kinds of crazy turns.

Much like in life, these changing circumstances affect your thoughts, mood, and the ways in which you will navigate yourself. In life, as in traveling down a river, it helps to have past experience and knowledge from which to draw on. Your journey should be guided by a strategy that is likely to work well for you.

Other important aspects include confidence and belief in your abilities to navigate the sometimes choppy waters, and perhaps having trusted companions to accompany and support you on the ride.

The Resilience Builder Program

The Resilience Builder Program for Children and Adolescents — Enhancing Social Competence and Self-Regulation is an innovative program designed to increase resilience in youth. The book is based on a 12-week resilience-based group therapy program and applies Cognitive Behavioral Theory and strategies.

The program outlines 30 group sessions that work on the areas of self-esteem, self-control, confidence and coping strategies (Karapetian Alvord, Zucker, Johnson Grados, 2011).

Key competencies addressed in each session include self-awareness, flexible thinking, and social competence. Through discussion and hands-on techniques such as role-playing, group members learn about anger/anxiety management, problem-solving, personal space awareness, self-talk, friendship skills, and other essential topics pertaining to social and personal wellbeing.

These group activities help develop specific protective factors associated with resilience.

The program includes relaxation techniques such as visualization, calm breathing, progressive muscle relaxation, and yoga, to enhance self-regulation. In order to apply their learnings to the outside world, the program assigns homework, community field trips, as well as a parent’s involvement component.

Resilience Builder Program is inventive, well thought out, sequenced and formatted, and offers a well-structured group framework, concrete enough for beginners. If you are looking for a detailed program to teach your child or student how to be resilient, this is an excellent option.

The Realizing Resilience Masterclass

If you are a coach, teacher or counselor and it is your passion to help others become more resilient, then the Realizing Resilience Masterclass© is exactly what you need.

Consisting of six modules which include positive psychology, resilience, attention, thoughts, action and motivation, this comprehensive online course will provide you with key psychological concepts, in an easily digestible manner for anyone that is new to the field.

Upon completion of the self-paced course, you will be awarded a certificate and can use the extensive library of tools, worksheets, videos, and presentations to teach resiliency.

Improving Mental Stamina

“Stamina” is defined by The Oxford Dictionary as the ability to sustain prolonged physical or mental effort (“Stamina,” 2019).

Mental Stamina is the single defining trait that enables us to endure the adversities of life. It is essential for withstanding both long-term challenges or unforeseen and unexpected struggles, concerns or trauma, and is only developed by practice and repetition.

Mental stamina requires planning, strength, perseverance, and concentration (Walkaden, 2016).

Mental Stamina is like an evolved hybrid between grit and resilience.

(Walkaden, 2016).

Often when we talk about stamina we reference elite athletes and sports teams, as both physical and mental stamina is crucial for this type of performance. However, everyone can benefit from increased mental stamina, not just athletes. Although no one builds mental stamina overnight, below Corb (n.d.) offers 5 tips for building your mental stamina over time:

However, everyone can benefit from increased mental stamina, not just athletes. Although no one builds mental stamina overnight, below Corb (n.d.) offers 5 tips for building your mental stamina over time:

1. Think Positively

Self-confidence and the belief in one’s ability to perform and to make decisions is one of the most important characteristics of a healthy mind. Training yourself to think optimistically and find the positive in every situation will most certainly help to build mental stamina over time.

2. Use Visualization

Visualization is an excellent tool for managing stress, overwhelming situations, and performance anxiety. Close your eyes and imagine a time that you succeeded in a similar situation. This includes remembering the feeling that accompanied that achievement, not just the visual.

3. Plan for Setbacks

Life most certainly does not always go the way we hoped or planned that it would. It’s important to re-center yourself and regain focus after a setback, as opposed to dwelling on the loss or misfortune. We cannot control the external events that happen around us, but we can control what we do afterward. It’s a good idea to have a plan in place that will help you to deal when things don’t go according to plan.

We cannot control the external events that happen around us, but we can control what we do afterward. It’s a good idea to have a plan in place that will help you to deal when things don’t go according to plan.

4. Manage Stress

Our ability to manage stress plays a large role in our ability to build mental stamina. Though not all stress is bad — positive stress (excitement) can be a motivating factor — it has the same physical effects on our bodies.

Useful techniques for managing stress include meditation and progressive muscle relaxation. It’s important to remember that you are in control and of your mental state, and how you will handle the stressor at hand.

5. Get More Sleep

It’s no secret that getting enough sleep is vital to our physical and mental functioning in everyday life. Sufficient sleep can help with on-the-spot decision making and reaction time. A sufficient amount of sleep is said to be seven to nine hours, or more if you are performing high-stress activities, both physical and mental.

Enhancing Resilience in the Community

Community resilience is the sustained ability of a community to utilize available resources (energy, communication, transportation, food, etc.) to respond to, withstand, and recover from adverse situations (e.g. economic collapse to global catastrophic risks) (Bosher, L. & Chmutina, K., 2017).

Successful adaptation in the aftermath of a disaster ensures that a community can return to normal life as effortlessly as possible. Community adaptation is largely dependent on population wellness, functioning, and quality of life (Norris, Stevens, Pfefferbaum, Wyche, & Pfefferbaum, 2007).

As is the case when faced with any problem, a community should implement a plan of action in order to come together and rebuild after a disaster. Below are the key components necessary for a community to build collective resilience after a tragedy:

- Reduce risk and resource inequities

- Engage local people in mitigation

- Create organizational linkages

- Boost and protect social supports

- Plan for not having a plan, which requires flexibility, decision‐making skills, and trusted sources of information that function in the face of unknowns.

What Builds Resilient Relationships?

Resilience is a very important aspect of any relationship. Relationships require ongoing attention and cultivation, especially during times of adversity. Have you ever wondered what makes some friendships or romantic relationships more likely to survive than others? Below, Everly (2018) suggests certain factors which seem to foster resiliency in relationships, and increase their likelihood of survival.

Seven Characteristics of Highly Resilient Relationships

1. Active Optimism

Active optimism is not just hoping that things will turn out well, rather, it is believing that things will turn out well and then taking action that will lead to a better outcome. In a relationship, this means an agreement to avoid critical, hurtful, cynical comments, and to instead, work together to harness the power of a positive self-fulfilling prophecy.

2. Honesty, Integrity, Accepting Responsibility for One’s Actions, and the Willingness to Forgive

When we commit to accepting responsibility for our actions, being loyal to one another and forgiving each other (and ourselves), we are bound to cultivate resilience within our relationships. This includes the old adage that honesty is the best policy, regardless of the outcome and consequences.

This includes the old adage that honesty is the best policy, regardless of the outcome and consequences.

3. Decisiveness

This means having the courage to take action, even when the action is unpopular or provokes anxiety in a relationship. Decisive action sometimes means leaving a toxic relationship or one that is not serving you well anymore, often times promoting one’s own personal resilience.

4. Tenacity

Tenacity is to persevere, especially in the face of discouragement, setbacks, and failures. It is important in relationships to remember that there will always be ebbs and flows, good times as well as hard times.

5. Self-Control

As it pertains to relationships, the ability to control impulses, resist temptations and delay gratification are clearly important qualities. Self-control helps one to avoid practices that will negatively impact their relationship, while promoting healthy practices, especially in the face of adversity.

6. Interpersonal Connectedness Through Honest Communication

The sense of “belonging” and connectedness in a relationship is maintained and honed through open, honest communication. Often times the most difficult conversations to have are the most important ones.

Often times the most difficult conversations to have are the most important ones.

7. Presence of Mind

Present mindedness has many positive implications for the individual, and this is also true for partners in a relationship. Present-minded awareness within a relationship leads to a calm, non-non-judgmental thinking style and open communication. Presence of mind enables collaborative thinking and openness to new solutions, rather than shooting them down and projecting blame.

These are just some of the characteristics that predict resilience in a relationship and increase the likelihood of a relationship rebounding after difficult situations.

How Do People Learn to Become Resilient for Life?

If you want to become resilient for life, it’s best to start with building your resilience in the present moment! Practice and commitment to the strategies and tips discussed above, will over time increase your ability to bounce back and adapt once life has presented you with hardships.

The silver lining to experiencing adverse life events is that the more you are able to flex your resiliency muscle, the better you will be able to bounce back again the next time life throws you a curveball!

Case Study Showing Ways to Build Resilience

In this study, Lipaz Shamoa-Nir (2014) presents a description of building organizational and personal resilience at three levels of institution: management, faculty, and students of a multi-cultural college. To do so, the college utilized three different framework models: the contact hypothesis model, the joint projects model, and the theoretical model.

The study discusses the complexities of constructing this multi-dimensional framework for improving communication between a radically diverse group of students with opposing political and cultural views. The students are immigrants living under a continuous threat of social and economic crisis, with tension and conflicts both internally and externally.

Each level of the institution must contribute to developing coping strategies for crisis situations as well as everyday reality. For faculty, this includes building a program that considers the strengths and weaknesses of students from social minority groups. For students, this includes social projects that express their cultural and national diversity.

For faculty, this includes building a program that considers the strengths and weaknesses of students from social minority groups. For students, this includes social projects that express their cultural and national diversity.

Most importantly, the process requires leadership from management-focused solutions and activities intended to instill a sense of confidence and certainty at all levels of the organization.

Some key takeaways from the case study are that although processes for building resilience may take several years, they can be accelerated by changes or crises that arise; and that while aspects of resilience are built-in routine situations, most of them are only tested in crisis situations.

Although every individual develops their own unique coping style, the proposed multi-dimensional resilience model references these six factors that comprise each style:

- Beliefs and Values

- Affect

- Social

- Imagination

- Cognition

- Physiology

Lastly, the case study may very well be relevant to other organizations or communities during or post-conflict.

How to Get a Better, Stronger and More Confident Mind

Confidence is one of the 4C’s of mental toughness! Nurturing a positive self-view and developing confidence in your ability to solve problems and in trusting your instincts, is one of the main factors in building resiliency. So how do we cultivate a more confident mind?

Below are 10 surefire ways that you can begin building your confidence (Bridges, 2017):

1. Get Things Done

Confidence and accomplishment go hand-in-hand. Accomplishing goals, and even taking small steps towards your goals, can help build your self-esteem and confidence in your abilities.

2. Monitor Your Progress

When working towards a goal, big or small, it is important to break it down into smaller, more manageable steps. In doing so, one will find it easier to monitor their progress and build confidence as they see the progress happening in real time. It helps to quantify your goals, as well as the actionable steps towards those goals.

3. Do The Right Thing

Highly confident people tend to live by a value system and make decisions based on that value system, even when it’s not necessarily in their best interest. When your decisions are aligned with your highest self, it can cultivate a more confident mind.

4. Exercise

Exercise not only benefits your physical body but your mind as well. Mental benefits of exercise include improved focus, memory retention, and stress and anxiety management. Exercise is also said to prevent and aid in depression. Confidence from exercising comes not only from the physical, visible benefits but also from the mental benefits.

5. Be Fearless

To be fearless in the pursuit of your dreams and goals requires a level of confidence. Conversely, challenging yourself by diving head first into things that scare you, will help to build your confidence. Often when we set big goals for ourselves it is easy to get overwhelmed and be fearful of failure. In these instances, it is important to gather up your courage and just keep going, one step at a time.

6. Stand-up For Yourself

To stand up for yourself when someone tells you that you can’t accomplish something is an effective way to develop your confidence. All too often we may end up believing the naysayers, as they are echoing the self-doubt we may be hearing in our heads. To nurture a positive self-view is to replace those negative thoughts with positive ones. Try to do so as well when someone does not believe in you.

7. Follow Through

Following through on what you say you’re going to do, not only helps to earn the respect of others but also respect for and confidence in yourself. Developing your follow-through skills will also help you accomplish your goals and likely strengthen your relationships, too.

8. Think Long-term

Often times, we trade in long-term happiness for more immediate gratification. We can build up our confidence by making sacrifices and decisions based on long-term goals rather than short-term comforts. Finding the discipline to do so will bring greater happiness in the long-term and a higher likelihood of achieving the goals you’ve set for yourself.

9. Don’t Care What Others Think

It is easy to fall into the trap of wondering what others may think of you, but it’s important to remember that what others think actually means nothing in the pursuit of your dreams. Build your confidence by believing in yourself and continuing to move forward, even when others might not agree with you.

10. Do More Of What Makes You Happy

When we take time for self-care and doing the things that bring us joy, it helps to enrich our lives and becomes our best selves. Confidence comes when we are aligned with our highest selves and proud of it.

3 YouTube Videos on How to Be Mentally Strong

A Take-Home Message

At the root of many of these tools and strategies for building your mental fitness, are Self-Awareness and Acceptance. In order to enhance, improve or build upon our existing mental strength, we must be aware of where we are at, and also accept that this is where we are at. Only then can we begin to take steps toward a stronger, healthier mental state.

Another key takeaway is that you cannot control everything that happens to you but you absolutely can control how you react to what happens. In these cases, your mind can be your biggest asset or your worst enemy. When you learn how to train it well, you can bounce back from difficult situations and can accomplish incredible feats.

In these cases, your mind can be your biggest asset or your worst enemy. When you learn how to train it well, you can bounce back from difficult situations and can accomplish incredible feats.

If you want to experience greater overall life satisfaction, you must be in good mental health. Mental fitness includes strength, toughness, and resilience. Building these muscles may be very challenging, and might take years of effort and commitment, but the benefits of being mentally fit and resilient will be seen in all aspects of your life.

Enhanced performance, better relationships, and a greater sense of wellbeing can all be achieved by developing healthy mental habits while giving up unhealthy mental habits.

We can all improve our mental health by implementing these strategies and committing to the process for the long-term.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our 3 Resilience Exercises for free.

- Bosher, L. & Chmutina, K.

(2017). Disaster Risk Reduction for the Built Environment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

(2017). Disaster Risk Reduction for the Built Environment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons. - Bridges, F. (2017, July 21). 10 Ways To Build Confidence. Forbes.com. Retrieved from https://www.forbes.com/sites/francesbridges/2017/07/21/10-ways-to-build-confidence/#6f1a4a293c59

- Clough, P.J., Earle, K., & Sewell, D. (2002). Mental toughness: The concept and its measurement. In Kobasa SC, 1979. Stressful events, Personality, and health: An inquiry into hardiness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 7: 413-423.

- Corb, R.E. (n.d.). 5 Tips for Building Mental Stamina. Retrieved from

https://www.webmd.com/fitness-exercise/features/mental-stamina#1 - Everly, Jr., G.S. (2018, April 24). 7 Characteristics of Resilient Relationships. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/when-disaster-strikes-inside-disaster-psychology/201804/7-characteristics-resilient

- Karapetian Alvord, M., Zucker, B.

, & Johnson Grados, J. (2011). Resilience Builder Program for Children and Adolescents — Enhancing Social Competence and Self-Regulation. Retrieved from https://www.researchpress.com/books/682/resilience-builder-program-children-and-adolescents

, & Johnson Grados, J. (2011). Resilience Builder Program for Children and Adolescents — Enhancing Social Competence and Self-Regulation. Retrieved from https://www.researchpress.com/books/682/resilience-builder-program-children-and-adolescents - Morin, A. (2017, April 29). Is It Best to Be Emotionally Intelligent or Mentally Strong? Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/what-mentally-strong-people-dont-do/201704/is-it-best-be-emotionally-intelligent-or-mentally

- Morin, A. (2019, January 24). 10 Tips for Raising Mentally Strong Kids. Retrieved from https://www.verywellfamily.com/tips-for-raising-mentally-strong-kids-1095020

- Norris, F.H., Stevens, S.P., Pfefferbaum, B., Wyche, K.F., & Pfefferbaum, R.L. (2007). Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness. Wiley Online Library. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6

- Resilience.

(2019). In OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/resilience

(2019). In OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/resilience - Shamoa-Nir, L. (2014). Defining Resilience from Practice: Case Study of Resilience Building in a Multi-Cultural College. ScienceDirect, Procedia Economics and Finance, (18), 279–286. Retrieved from https://ac.els-cdn.com/S2212567114009411/1-s2.0-S2212567114009411-main.pdf?_tid=f1e9af4b-1736-458c-9117-6f7f5dc4f8d2&acdnat=1549855807_4ac22ce951b98528e8eb289bc387018a

- Southwick, S.M., Bonanno, G.A., Masten, A.S., Panter-Brick, C., & Yehuda, R. (2014). Resilience definitions, theory, and challenges: interdisciplinary perspectives. Eur J Psychotraumatol. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4185134/

- Stamina. (2019). In OxfordDictionaries.com. Retrieved from http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/stamina

- Strycharczyk, D. (2015, July 31). Resilience and Mental Toughness: Is There a Difference and Does it Matter? Retrieved from https://www.

koganpage.com/article/resilience-and-mental-toughness-is-there-a-difference-and-does-it-matter

koganpage.com/article/resilience-and-mental-toughness-is-there-a-difference-and-does-it-matter - Strycharczyk, D. & Clough, P. (n.d.). Resilience, Mental Toughness. Retrieved from https://www.fahr.gov.ae/Portal/Userfiles/Assets/Documents/4d12e7a0.pdf

- The Road to Resilience. (n.d.). American Psychology Association. Retrieved from https://www.apa.org/helpcenter/road-resilience.aspx

- Turner, I. (2017, October 14). Mental Toughness – The “Grit” Behind the 4Cs. Retrieved from https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/mental-toughness-grit-behind-4cs-ian-turner/

- Walkaden, C. (2017, July 14). What is Mental Stamina. Retrieved from https://www.cwcounselling.com.au/what-is-mental-stamina-watch-free-webinar/

- What is Mental Toughness? (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.mentaltoughnessinc.com/what-is-mental-toughness/

- Whitley, R. (2018, February 15). Three Simple Ways to Enhance Mental Health Resilience. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.

psychologytoday.com/us/blog/talking-about-men/201802/three-simple-ways-enhance-mental-health-resilience

psychologytoday.com/us/blog/talking-about-men/201802/three-simple-ways-enhance-mental-health-resilience

FGBNU NTsPZ. ‹‹Selected Works››

The group of mental or mental illnesses includes all those morbid processes in which mental disorders, resp. neuropsychic activity, in other words, disorders in the field of those functions, thanks to which the attitude of the individual to the world around is established. From this definition it is not difficult to see that mental illnesses are not in the least expressed solely by changes in the sphere of the psyche (resp. neuro-psyche), but that they can also be accompanied by other disorders and, among other things, changes in certain conductive functions of the nervous system. systems. And indeed, getting to know the various forms of mental or mental illnesses and, in particular, with the disorders by which they are expressed, it is easy to see that in essence there is not a single mental illness, or almost none, in which, along with disorders of the mental sphere, there are no certain disturbances would be found on the part of the conductive functions of the nervous system and organs of the body subordinate to the activity of the nervous system, albeit mildly expressed.

This fact becomes quite understandable if we take into account that both diseases, i.e., the so-called mental and proper nervous ones, refer to the defeat of the same nervous system.

Modern medicine, contrary to the recent past, even combines mental and nervous diseases, since it turned out that mental activity is completely and unconditionally dependent on the activity of the higher cortical centers of the nervous system and their mutual connections with each other, while defeat other centers and conductors of the nervous system causes a variety of nervous diseases.

Regardless of this anatomical and physiological point of view, which establishes, so to speak, a natural connection between mental and nervous diseases, there is an undeniable etiological relationship between the two. Particularly conclusive facts in this respect can be gleaned from heredity. As is known, it has now been precisely established that in families weighed down by unfavorable or pathological heredity, we encounter, along with mental, also various nervous diseases.

On the other hand, it is known that from persons suffering from mental illnesses, offspring occur that differ not only in one or another deviation of the mental sphere, but are also affected by nervous diseases, especially general neuroses, and, conversely, from persons suffering from nervous diseases, especially by general neuroses, offspring usually occur in which one or another number of psychopaths can be noted.

In a word, between mental and nervous diseases there is the closest relationship that can be imagined in terms of heredity.

Similarly, the most important etiological factors, in addition to heredity, are common to the development of mental and nervous diseases. Take, for example, trauma, moral shock, syphilis, various acute infections and other poisonings, as well as various self-poisonings. As is known, all these conditions contribute to one degree or another to the development of both mental and nervous diseases. Often, even the result of the influence of the above causes are diseases in which mental and nervous symptoms seem to be mixed with each other.

Such are traumatic neuropsychoses, neurites with mental disorders, syphilitic lesions of the brain with mental defects, alcoholic false paralysis, etc.

disorders. This position is true not only in relation to the so-called organic psychoses, but also to the group of hysterical, epileptic, neurasthenic, and also, to a certain extent, to the group of degenerative and other psychoses.

On the other hand, in many nervous diseases, especially in the so-called general neuroses, as well as in various brain lesions (tumors, softening, hemorrhages, sclerosis, etc.), certain disorders of the mental sphere can be discovered.

Further, the relationship between mental and nervous diseases is quite clearly established by the fact that in certain cases nervous diseases are complicated by mental disorders. Mention should be made here of the psychoses that develop on the basis of tabes, Huntington's chorea, hemorrhagic encephalitis, etc. On the other hand, there are morbid mental forms during which certain nervous lesions develop. These include arteriosclerotic psychoses, syphilitic psychoses, etc.

These include arteriosclerotic psychoses, syphilitic psychoses, etc.

We then know a whole series of morbid forms in which mental and nervous disorders go hand in hand to such an extent that it is even difficult to decide where it is more correct to attribute these disorders to nervous or mental diseases. These include certain general or major neuroses, such as hysteria, myasthenia gravis and neurasthenia, partly epilepsy, certain family nervous diseases accompanied by dementia, etc.

, Janet, Reymond, and others, the view is more and more established that despite a number of symptoms that bring this form of the disease closer to purely nervous lesions, it must be considered as a mental illness, not only because purely mental symptoms are found here, as peculiar character traits, a tendency to develop hallucinations, obsessions, etc., but also because a number of symptoms in hysteria, which at first seem nervous, like paralysis, convulsions, contractures, etc., can be caused and eliminated by so-called mental influence. In fact, if we take into account the fact that all the main symptoms of hysteria can be caused by simple suggestion and can be eliminated by suggestion, then there is no reason to doubt the psychic nature of these symptoms. But, on the other hand, there are still some manifestations of hysteria, especially in plant functions, which are difficult to explain in a purely psychic way. In view of this, guided by physiological and chemical research, we are inclined to look at hysteria as an metabolic disease in which the entire nervous system is affected in general, and especially its mental functions.

In fact, if we take into account the fact that all the main symptoms of hysteria can be caused by simple suggestion and can be eliminated by suggestion, then there is no reason to doubt the psychic nature of these symptoms. But, on the other hand, there are still some manifestations of hysteria, especially in plant functions, which are difficult to explain in a purely psychic way. In view of this, guided by physiological and chemical research, we are inclined to look at hysteria as an metabolic disease in which the entire nervous system is affected in general, and especially its mental functions.

On the other hand, a condition described under the name of various kinds of phobias, especially by Equirol, Falre, Westphal, Kraft-Ebing, Ballem, Tamburini, Magnan, me, Pieter and Régy, etc., recently by some of the French authors , especially Janet, Reymond, and others, stands out from the usual forms of neurasthenia called psychasthenia. For my part, in Russian literature, as early as 1885, I described in detail the same form of the disease under the name of psychopathy or psychoneurasthenia.

It must be borne in mind that the form of neurasthenia proper refers to manifestations of irritable weakness and general suppression of the nervous system. At the same time, elementary symptoms are found on the mental side, reflecting a general decrease in nervous activity in the form of rapid mental fatigue, internal restlessness and melancholy, an excessive tendency to develop affects, mood instability, etc. To psychasthenia, resp. psychoneurasthenia, include those painful conditions in which the above physical manifestations recede into the background and completely special mental disorders come to the fore in the form of various kinds of obsessive states, the so-called phobias and obsession, in the form of amazing lack of will, causeless longing and fear, systematic tics etc. In etiological terms, both morbid forms must also be isolated from each other, since the first neurosis usually develops in adults from various random causes of a physical or moral nature, which sharply weaken the nervous system. At the same time, there is often a hereditary predisposition, but for the most part it is insignificant and hidden, while psychasthenia usually develops in people who are deeply predisposed, who have acquired degeneration from birth or by inheritance, and its features are already found at a relatively young age.

At the same time, there is often a hereditary predisposition, but for the most part it is insignificant and hidden, while psychasthenia usually develops in people who are deeply predisposed, who have acquired degeneration from birth or by inheritance, and its features are already found at a relatively young age.

Be that as it may, both of these forms of the disease, and especially psychoneurasthenia or psychasthenia, appear not so much as neuroses as psychoses, and therefore they have recently quite rightly been called psychoneuroses.

With regard to epilepsy, we must keep in mind that, along with major seizures, in which a temporary complete loss of neuropsychic activity is detected, therefore, a symptom is undoubtedly of a mental nature, and at the same time tonic clonic convulsions, which are a symptom of a nervous nature, there are usually also attacks of minor or so-called mental epilepsy, in which all phenomena occur in the so-called mental sphere. If we then take into account the existence of special character changes in epileptics, the frequent development of mental weakness and the temporary appearance of mental disorders in the form of so-called epileptic psychoses, it becomes clear that we are dealing here with a neurosis in which purely nervous symptoms are often inferior in its strength and significance to the symptoms of a mental nature.![]()

In addition, it is impossible not to take into account that real psychosis, like psychoneurosis, come close to each other, not only because the symptom complex of both has much in common with each other, but at the same time also because general psychoneuroses give rise to the development of so-called transitional or mixed forms. And in fact, neurasthenia, psychasthenia, melancholia, hypochondria, and even hysteria at the beginning of their development have so much in common with each other that often long-term observation is required to finally settle on one or another diagnosis.

If we then delve into the pathogenesis of diseases known as psychoneuroses or major neuroses, then we will have in mind mainly this or that metabolic disorder, leading to a change in the functions of the nervous system in general and the cerebral cortex in particular. At least this view, based on metabolic studies, has recently acquired more and more rights in relation to the so-called genuine epilepsy. Similarly, there are clear indications of the dependence of hysteria and neurasthenia on disturbances in metabolism.

Similarly, there are clear indications of the dependence of hysteria and neurasthenia on disturbances in metabolism.

On the other hand, many of the mental disorders, especially melancholia, mania, acute amentia and some others, also have an underlying metabolic disorder, in favor of which at least much evidence can be given.

So, there can be no doubt that mental diseases and general nervous, and in particular, craniocerebral diseases in the pathological and biological sense are, if not one whole, then at least difficult to separate from each other areas of pathology, as a result of which they are often studied in the course of medical sciences in one clinic, divided into two departments, one of which serves for mental, and the other for nervous patients.

Translating all of the above into practical language, it can be asserted without the risk of falling into exaggeration that one cannot claim to be a thorough study of mental illness without acquaintance with nervous diseases and, on the other hand, one cannot be a good neuropathologist without being familiar with mental disease states.

Nevertheless, the practical importance of separating mental patients from patients of all other categories, including nervous ones, leads to the need to distinguish mental patients from both nervous and other somatic Solo. In this regard, we must say that although in many cases it is impossible to strictly scientifically separate mental disease states from nervous ones, in practical terms, all those cases where changes in the mental sphere are found during the entire disease state and where they have a predominant significance can be recognized mental diseases, while other disorders of the nervous system, in which mental changes are of lesser importance than nervous ones or appear to be episodic during the course of a diseased state, can and should be recognized as nervous diseases.

On the same basis, some somatic diseases, for example, typhoid fever, etc., despite the frequent detection of clear symptoms from the neuropsychic sphere during the course of the disease, do not belong to the category of mental diseases.

The close relationship that exists between mental and nervous diseases naturally brings psychiatry closer to the rest of medicine, since nervous diseases have always been in close connection with other medical sciences. But no less, if not more, psychiatry is brought closer to the rest of the medical sciences by the latest views on the origin of many mental illnesses, as the result of self-poisoning of the body.

Together with this, for the vast majority of mental illnesses, it must be recognized that the damage to the brain functions underlying them is not primary and independent, but is due to autointoxications and the action of toxic principles that affect the entire body in general, including those that disrupt the functions of the higher centers of the nervous system and their associations. In other words, in these cases it is not a question of a primary lesion of the brain itself, but of the lesion of the whole organism; mental illnesses themselves are combinations of functional disorders either associated with the general conditions of the organism’s vital activity and a violation of its functions in the form of autointoxication of one kind or another, or associated with the influence of a general infection and the action of certain toxins on the brain. In these cases, the changes occurring in the brain can be considered only as derivatives of the main lesion of the body, which has its own etiology, its own development, course, and even outcome, to the extent that it is not affected by certain therapeutic measures.

In these cases, the changes occurring in the brain can be considered only as derivatives of the main lesion of the body, which has its own etiology, its own development, course, and even outcome, to the extent that it is not affected by certain therapeutic measures.

If organs such as the central nervous system are affected to a greater extent than other parts of the body, then this may be due to the infection itself or autointoxication and its selective property, like other poisons that have this feature, further, the extreme tenderness of the tissue itself of the brain, special functional and other conditions that put the brain under these conditional conditions in the position of locus minoris resistentiae, individual characteristics of a given organism acquired by inheritance and conditions of a past life, etc.

Moreover, even those anatomical changes in the brain that are revealed in such cases are only in a certain number the direct culprits of mental disorders, more often they are derivatives of autointoxication, like those mental disorders that are its consequences. In this case, it is a matter of a change in the composition of the blood and the development of chemical products and toxins in it, which, poisoning the nervous tissue, on the one hand, cause a breakdown in its functional activity, and on the other, acting for a certain time in the form of more or less long-term influences, cause changes in the brain tissue.

In this case, it is a matter of a change in the composition of the blood and the development of chemical products and toxins in it, which, poisoning the nervous tissue, on the one hand, cause a breakdown in its functional activity, and on the other, acting for a certain time in the form of more or less long-term influences, cause changes in the brain tissue.

In these cases, the latter cannot serve as an explanation for the painful symptoms, just as changes in the brain tissue when external, so-called intellectual poisons are introduced into the body, do not explain to us those functional disorders of the neuropsychic sphere that are caused by them. The fact is that intoxications, like autointoxications, can cause functional disorders in the activity of brain cells, producing temporary changes in cerebral circulation and dynamic changes in the nutrition of brain cells without persistent structural changes. If later, during chronic poisoning, more persistent structural changes are found in the cells, then they are the result of prolonged malnutrition and cell poisoning and, therefore, in themselves, as secondary phenomena, cannot be taken as the basis for functional disorders of the mental sphere.

To this it should be added that the changes in the nervous tissue produced by various poisons may be more or less similar and even the same, since in essence the influence of poisons does not so much act directly on the protoplasm of the cell, but on the conditions of its nutrition, the violation of which and leads to more or less the same changes in the structure of the cell, despite the difference in the action of poisons.

It goes without saying that the aforementioned structural changes in brain cells due to autointoxications are not indifferent to neuropsychic functions, but for the most part we cannot definitely indicate their significance in the overall picture of the disease, until we are talking about irreparable atrophy of nerve cells and fibers, accompanied by the development of dementia.

All of the above leads us to the conclusion that the roots of mental illness, if we exclude relatively rare cases of mental disorders caused by traumatic injuries of the skull, lie not in the brain, but in a violation of the vital activity of the organism, due to certain internal defects or introduced from outside common pathogenic principles, and they differ from all other disease states only in that as a result of the disturbed vital activity of the organism, a functional or organic disturbance of brain activity, leading to mental disorders, comes to the fore in terms of the sharpness of external manifestations.