Axis 5 disorders

DSM-5 Changes: Personality Disorders (Axis II)

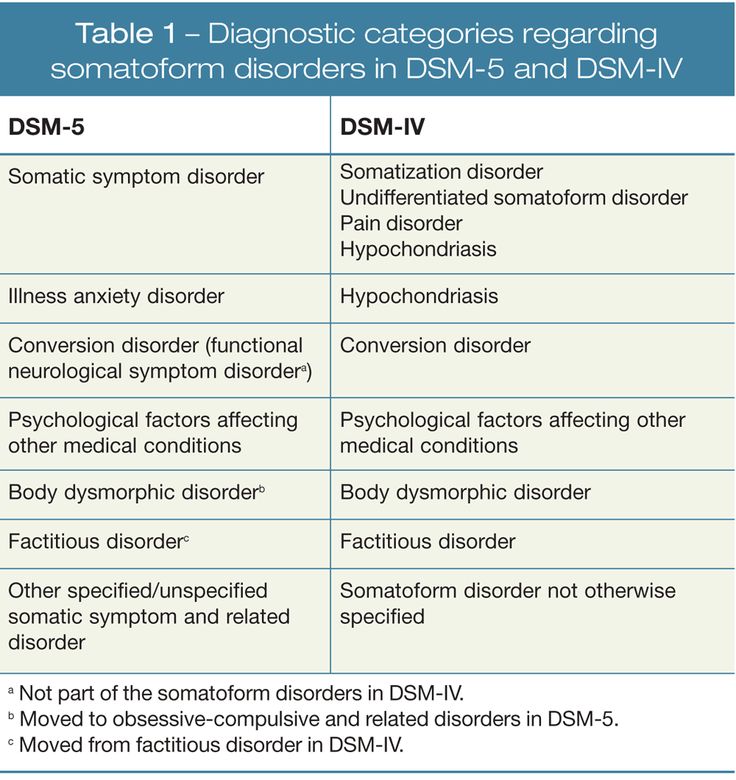

The new Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) has some changes related to personality disorders, which were coded on Axis II under the DSM-IV. This article outlines some of the major changes to these conditions.

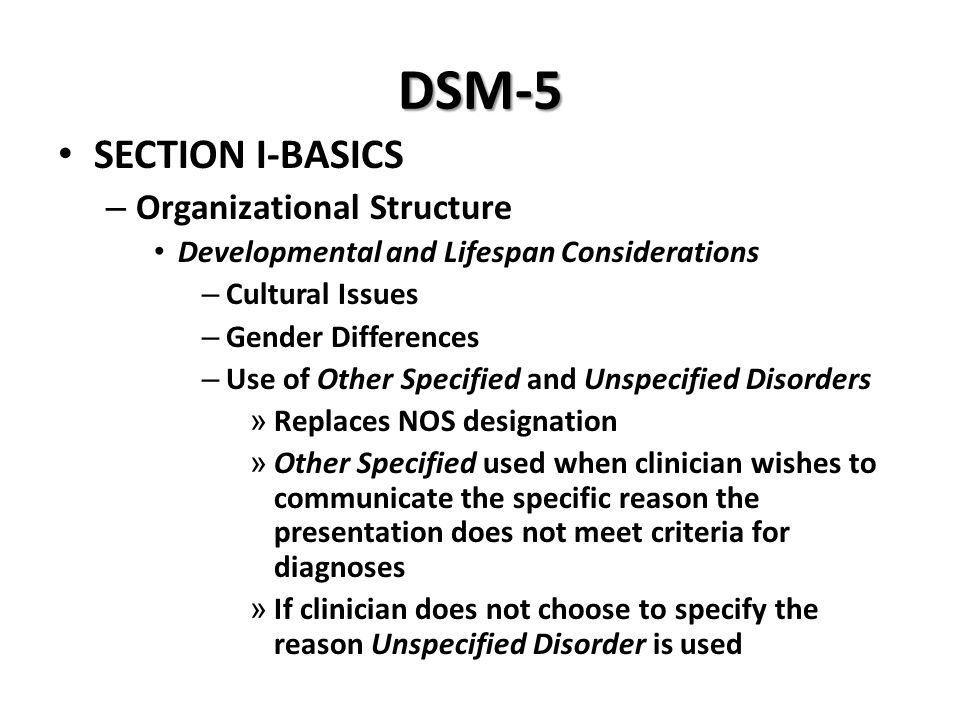

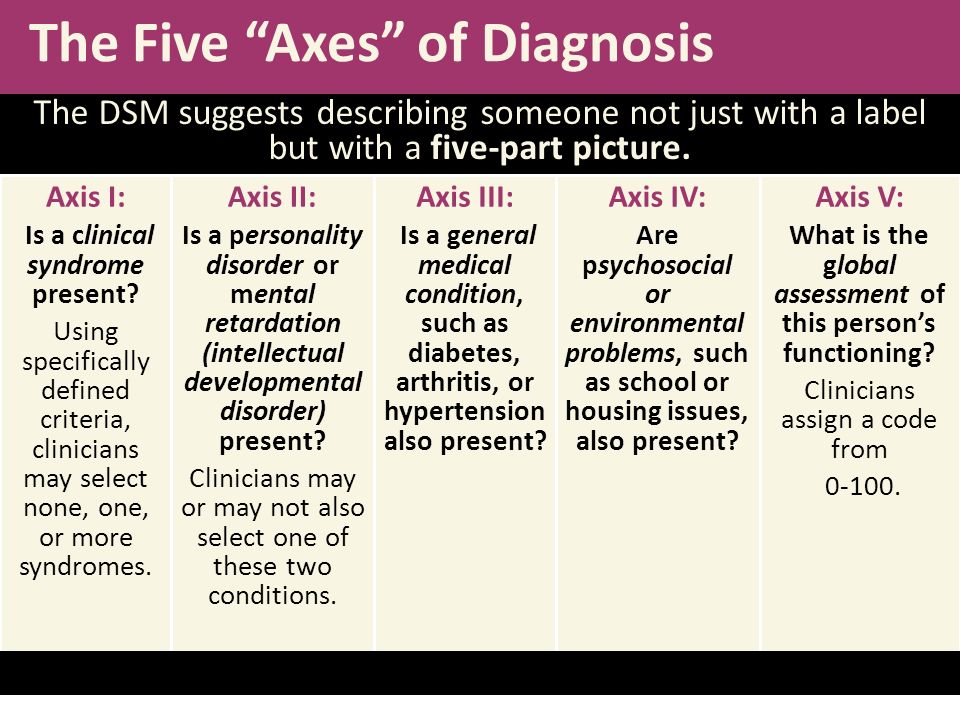

According to the American Psychiatric Association (APA), the publisher of the DSM-5, the major change with personality disorders is that they are no longer coded on Axis II in the DSM-5, because DSM-5 has done away with the duplicative and confusing nature of “axes” for diagnostic coding.

Prior to the DSM-5, mental disorders and health concerns of a person were coded in five separate areas — or axes — in the DSM. According to the APA, this multiaxial system was “introduced in part to solve a problem that no longer exists: Certain disorders, like personality disorders, received inadequate clinical and research focus. As a consequence, these disorders were designated to Axis II to ensure they received greater attention.

”

Since there really was no meaningful difference in the distinction between these two different types of mental disorders, they axis system became unnecessary in the DSM-5. The new system combines the first three axes outlined in past editions of DSM into one axis with all mental and other medical diagnoses. “Doing so removes artificial distinctions among conditions,” says the APA, “benefiting both clinical practice and research use.”

Personality Disorders in the DSM-5

The good news is that none of the criteria for personality disorders have changed in the DSM-5. While several proposed revisions were drafted that would have significantly changed the method by which individuals with these disorders are diagnosed, the American Psychiatric Association Board of Trustees ultimately decided to retain the DSM-IV categorical approach with the same 10 personality disorders.

A new hybrid personality model was introduced in the DSM-5’s Section III (disorders requiring further study) that included evaluation of impairments in personality functioning (how an individual typically experiences himself or herself as well as others) plus five broad areas of pathological personality traits. In the new proposed model, clinicians would assess personality and diagnose a personality disorder based on an individuals particular difficulties in personality functioning and on specific patterns of those pathological traits.

In the new proposed model, clinicians would assess personality and diagnose a personality disorder based on an individuals particular difficulties in personality functioning and on specific patterns of those pathological traits.

The hybrid methodology retains six personality disorder types:

- Borderline Personality Disorder

- Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder

- Avoidant Personality Disorder

- Schizotypal Personality Disorder

- Antisocial Personality Disorder

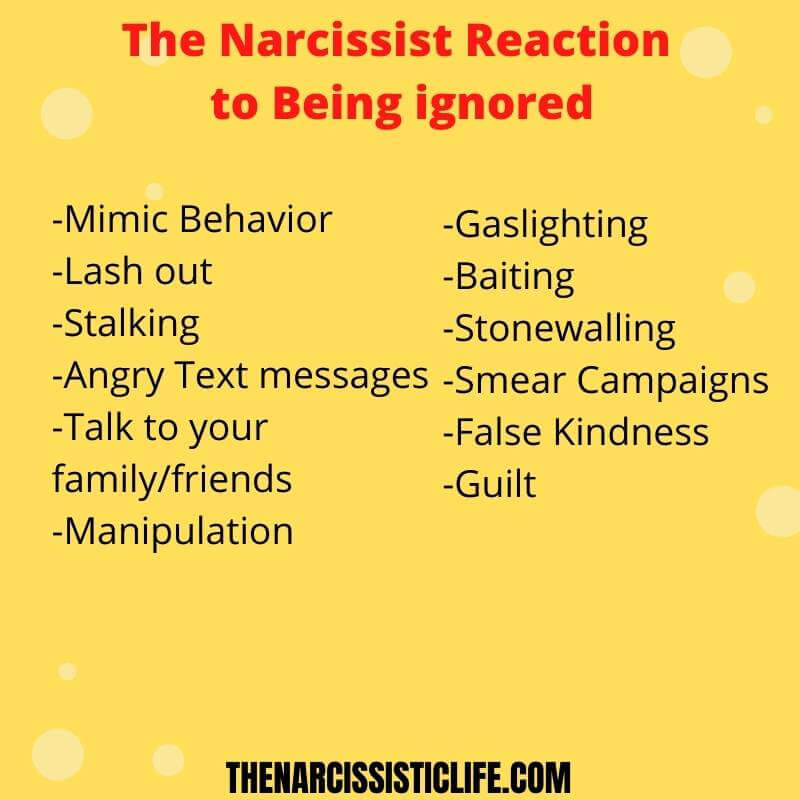

- Narcissistic Personality Disorder

According to the APA, each type is defined by a specific pattern of impairments and traits. This approach also includes a diagnosis of Personality DisorderTrait Specified (PD-TS) that could be made when a Personality Disorder is considered present, but the criteria for a specific personality disorder are not fully met. For this diagnosis, the clinician would note the severity of impairment in personality functioning and the problematic personality trait(s).

This hybrid dimensional-categorical model and its components seek to address existing issues with the categorical approach to personality disorders. APA hopes that inclusion of the new methodology in Section III of DSM-5 will encourage research that might support this model in the diagnosis and care of patients, as well as contribute to greater understanding of the causes and treatments of personality disorders.

Furthermore, the APA notes:

For the general criteria for personality disorder presented in Section III, a revised personality functioning criterion (Criterion A) has been developed based on a literature review of reliable clinical measures of core impairments central to personality pathology. Furthermore, the moderate level of impairment in personality functioning required for a personality disorder diagnosis was set empirically to maximize the ability of clinicians to identify personality disorder pathology accurately and efficiently.

The diagnostic criteria for specific DSM-5 personality disorders in the alternative model are consistently defined across disorders by typical impairments in personality functioning and by characteristic pathological personality traits that have been empirically determined to be related to the personality disorders they represent.

Diagnostic thresholds for both Criterion A and Criterion B have been set empirically to minimize change in disorder prevalence and overlap with other personality disorders and to maximize relations with psychosocial impairment.

A diagnosis of personality disordertrait specified — based on moderate or greater impairment in personality functioning and the presence of pathological personality traits — replaces personality disorder not otherwise specified and provides a much more informative diagnosis for patients who are not optimally described as having a specific personality disorder. A greater emphasis on personality functioning and trait-based criteria increases the stability and empirical bases of the disorders.

Personality functioning and personality traits also can be assessed whether or not an individual has a personality disorder, providing clinically useful information about all patients. The DSM-5 Section III approach provides a clear conceptual basis for all personality disorder pathology and an efficient assessment approach with considerable clinical utility.

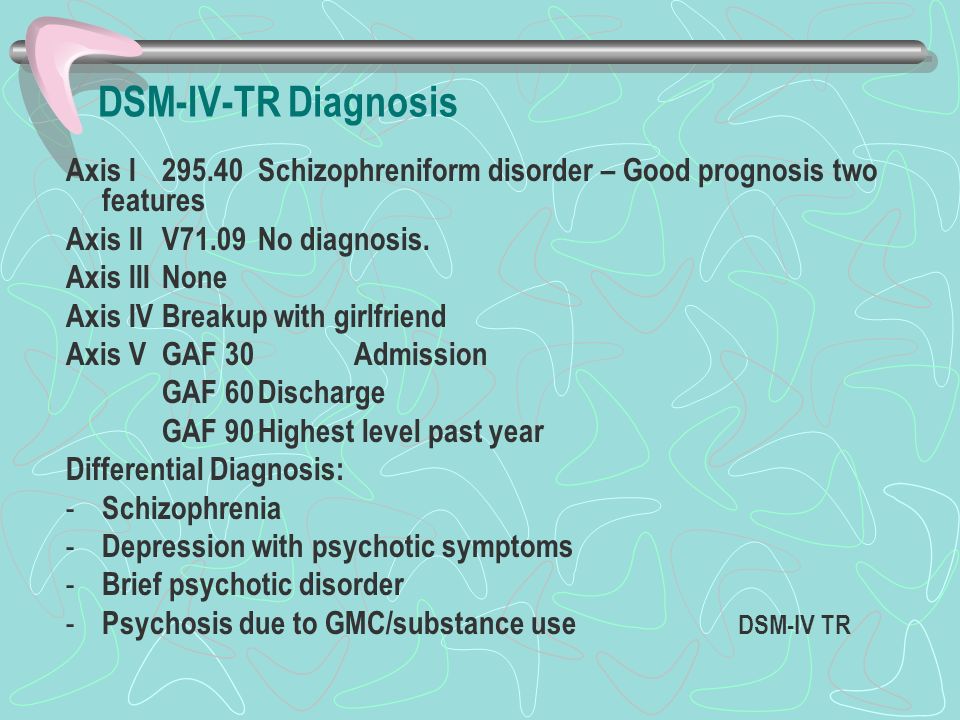

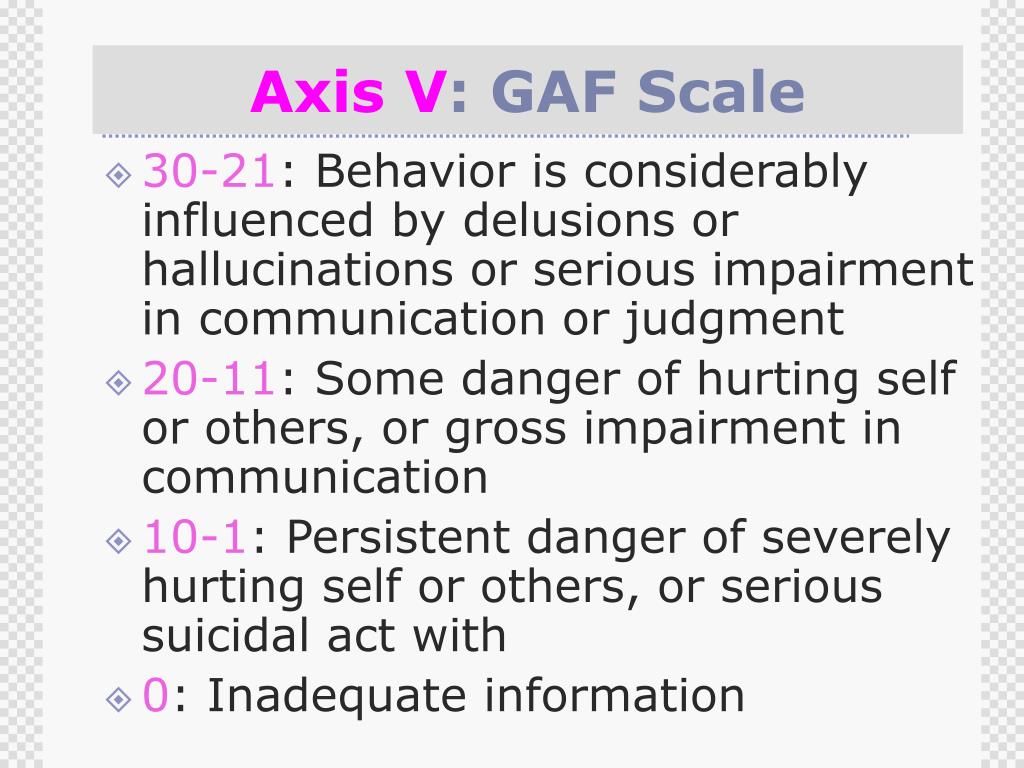

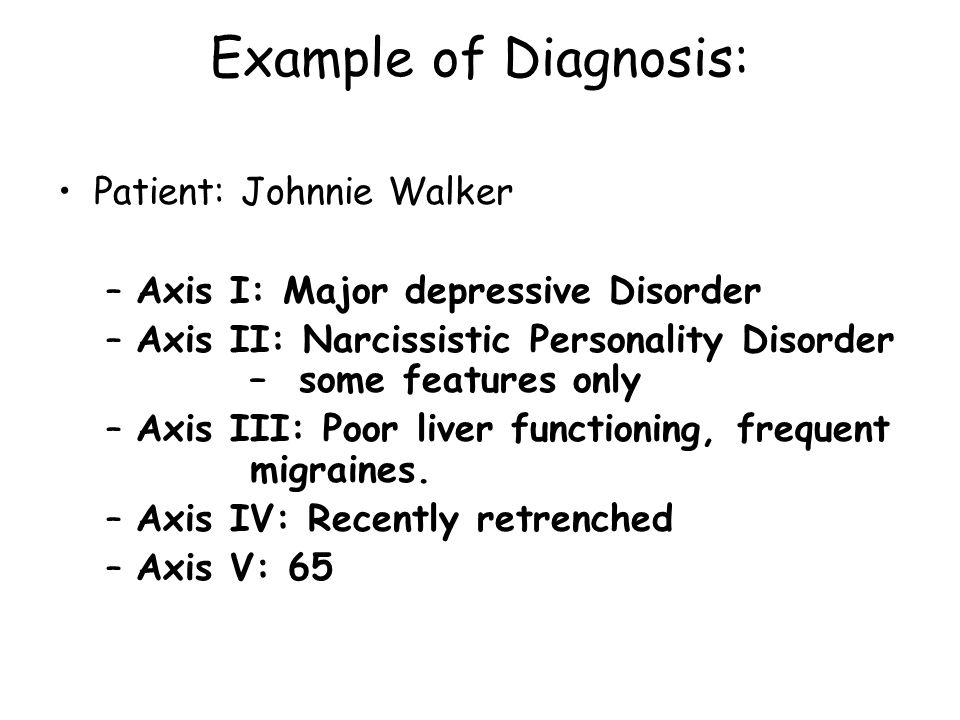

Axis I, Axis II, Axis III, Axis IV, Axis V Diagnosis

IMPRESSION:

Axis I: Dementia with delusions, probable.

Axis II: Deferred.

Axis III:

1. Weakness.

2. History of cerebrovascular accident.

3. History of diabetes mellitus.

Axis IV: Extreme.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning 35.

ASSESSMENT:

Axis I: Bipolar disorder, not otherwise specified; history of polysubstance dependence.

Axis II: Deferred.

Axis III: Atypical chest pain and hypertension.

Axis IV: Stressors multiple, severe, related to primary support group.

Axis V: Global assessment functioning of 45.

ASSESSMENT:

Axis I: Opioid withdrawal, opioid dependence, adjustment disorder with depressed mood.

Axis II: Deferred.

Axis III: Crohn disease, pulmonary emboli.

Axis IV: Stressors related to the patient’s medical condition.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning of 45.

ASSESSMENT:

Axis I: Rule out adjustment reaction, not otherwise specified, secondary to medical complications (309.9).

Axis II: Deferred.

Axis III: See above.

Axis IV: Current psychosocial stressors include prolonged hospitalization.

Axis V: Current global assessment of functioning equals 75-80.

DIAGNOSTIC IMPRESSION:

Axis I: Major depression, recurrent type.

Axis II: Neurological factors affecting physical condition, histrionic personality.

Axis III:

1. Atypical chest pain.

2. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

3. Hypertension.

Axis IV: Husband’s illness.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning 44 upon evaluation, past year 55.

DIAGNOSTIC IMPRESSION:

Axis I: Bipolar mood disorder with psychotic features, rule out schizoaffective disorder.

Axis II: Borderline personality traits.

Axis III:

1. Hypertension.

2. Gastroesophageal reflux disease.

Axis IV: Unsatisfactory living condition.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning 42 upon evaluation, past year 45.

DIAGNOSTIC IMPRESSION:

AXIS I: 294.9. Cognitive disorder, not otherwise specified; rule out adjustment reaction, not otherwise specified.

AXIS II: Deferred.

AXIS III: See above.

AXIS IV: Current psychosocial stressors include being away from primary support, having limited access to health care and prior substance abuse.

AXIS V: Current global assessment of functioning equals 60, past year 80.

DIAGNOSTIC IMPRESSION:

Axis I: 296.33. Major depressive disorder, recurrent, without psychotic features.

Axis II: Borderline intellectual functioning and borderline personality features, provisional.

Axis III: None reported.

Axis IV: Problems related to his legal status and social environment.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning currently equals 30. Highest past year equals unknown.

DIAGNOSES:

Axis I:

1. Generalized anxiety disorder, currently in remission with medications.

Generalized anxiety disorder, currently in remission with medications.

2. Depressive disorder, in remission.

3. History of posttraumatic stress disorder, also in good remission.

4. Opioid dependence, in forced remission.

Axis II: Antisocial personality disorder.

Axis III: Physical examination not done.

Axis IV: Legal problems.

Axis V: Past global assessment of functioning of 70. Current global assessment of functioning of 70.

DIAGNOSES:

Axis I:

1. Schizoaffective disorder, bipolar type.

2. Alcohol dependence, in a controlled environment.

3. Polysubstance dependence, in a controlled environment.

4. Nicotine dependence.

Axis II: Antisocial personality disorder.

Axis III: Hyperlipidemia.

Axis IV: Limited support system.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning of 60.

DIAGNOSTIC ASSESSMENT:

Axis I:

1. Adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

2. Polysubstance dependence, currently in remission in a controlled environment.

3. Substance-induced mood disorder.

4. Alcohol dependence syndrome, currently in remission in a controlled environment.

Axis II: Antisocial personality disorder.

Axis III: Human immunodeficiency virus positive.

Axis IV: Psychosocial stressors, severe. Lack of social skills, poor social support, chronic mental illness.

Axis V: Current global assessment of functioning of 60-65.

DIAGNOSES:

Axis I: Schizophrenia, paranoid type, with chronic delusions and partial refractoriness to treatment.

Axis II: None.

Axis III: Hypertension and residual chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Axis IV: Limited support system.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning of 51-55.

DIAGNOSTIC IMPRESSION:

Axis I:

1. History of agoraphobia, in remission.

2. Substance abuse, mixed type, per history.

Axis II: Antisocial personality disorder.

Axis III: Splenectomy.

Axis IV: Legal problems.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning of 70.

DIAGNOSES:

Axis I: Mood disorder, not otherwise specified; rule out generalized anxiety disorder with agoraphobia; rule out major depressive disorder; rule out schizophreniform disorder; rule out substance-induced mood disorder.

Axis II: Deferred.

Axis III: Possible history of anticholinergic delirium and dextromethorphan toxicity.

Axis IV: Severe problems with primary and social support, occupation, finances and education.

Axis V: Current global assessment of functioning is 30 to 35.

DIAGNOSES:

AXIS I: Chronic schizophrenia, undifferentiated type, posttraumatic stress disorder, impulse control disorder, not otherwise specified.

AXIS II: Mild mental retardation.

AXIS III: History of seizure disorder and diabetes mellitus.

AXIS IV: Moderate.

AXIS V: Global assessment of functioning is 40.

DIAGNOSES:

AXIS I:

1. Major depression, recurrent, severe with intermittent stress related visual hallucinations, symptoms in remission.

2. Rule out bipolar disorder.

3. Medication noncompliance.

AXIS II: Narcissistic features.

AXIS III:

1. Hypertension, stable.

2. Gastroesophageal reflux disease, stable.

AXIS IV: Moderate.

AXIS V: Global assessment of functioning 65 on discharge.

DIAGNOSES:

AXIS I:

1. Bipolar disorder, mixed features, symptoms in remission.

2. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder by history, symptoms in remission.

3. Rule out intermittent explosive disorder.

AXIS II: No diagnosis.

AXIS III:

1. Hypercholesterolemia, stable on discharge.

2. Increased bilirubin, stable on discharge.

AXIS IV: Mild.

AXIS V: Global assessment of functioning 65 on discharge.

DISCHARGE DIAGNOSIS:

AXIS I:

1. Bipolar disorder, depressed, symptoms in remission.

2. Attention deficit disorder, symptoms in remission.

AXIS II: Deferred.

AXIS III: Asthma, stable.

AXIS IV: Moderate history of noncompliance with medications.

AXIS V: Global assessment of functioning 65 on discharge.

INITIAL IMPRESSION:

Axis I:

1. 300.4. Dysthymic disorder, early onset. Rule out 309.81, posttraumatic stress disorder.

2. Polysubstance dependence.

Axis II: Deferred.

Axis III: No diagnosis.

Axis IV: Psychosocial stressors, severe.

Axis V: Current global assessment of functioning of 60 to 70, past year 60 to 70.

DIAGNOSTICS:

Axis I:

1. Obsessive-compulsive disorder (primarily obsession).

2. Generalized anxiety disorder.

Axis II: Borderline personality disorder with history of self-mutilation, which is stable at this time.

Axis III: Medical history.

Axis IV: Stressors severe due to past psychiatric history and personality pathology as well as anxiety related symptoms.

Axis V: Global assessment of functioning of 51-55.

Annotated index of articles of the National Psychological Journal

Risks of psychological security of the individual in the context of the introduction of digital educational technologies at the stage of vocational training

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. p.132–143

No. 4. p.132–143

Khudyakova T.L. Gridyaeva L.N. Klepach Yu.V. Petrosyants V.R.

moreDownload PDF0003

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. pp.116–131

Shoigu Yu. S.

moreDownload PDF

119

Labor interests as a key factor in the involvement and effectiveness of educational technology workers

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. p.102–115

Lobanova T. N.

moreDownload PDF

77

Psychological predictors of procrastination in psychology students

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. p.91–101

Boyarinov D.M. Gubaidulina L.M. Novikova Yu.A. Kachina A.A. Barabanshchikova V.V.

moreDownload PDF

144

Chronic stress and temporary self-regulation in sales managers

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. c.80–90

No. 4. c.80–90

Shirokaya M.Yu. Gorbatykh M.V.

moreDownload PDF

132

Adaptability as a predictor of changes in the functional states of participants in a marine scientific expedition to the Arctic

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. p.65–79

Simonova N.N. Tunkina M.A. Korneeva Ya.A. Trofimova A.A.

moreDownload PDF

42

Contribution of Dispositional Mindfulness to Acute and Chronic Stress Resilience in Medical Staff During the COVID’19 Pandemic

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. p.53–64

Blinnikova I.V. Matyushin V.V. Gushchin M.V. Lange M.D.

moreDownload PDF

66

Self-presentation strategies in author's texts of specialists with different professional experience

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. pp.42–52

No. 4. pp.42–52

Abdullaeva M. M.

moreDownload PDF

39

Meaningfulness of life and professional experience as predictors of professional self-determination of future teachers

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. p.29–41

Belyakova E.G. Bykov S.A.

moreDownload PDF

41

The status of professional identity as a factor in the psychological adaptation of a person in adolescence

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 4. p.19–28

Karabanova O.A. Molchanov S.V. 2022. No. 4. p.9–18

Emelin V.A.

moreDownload PDF

52

Current trends in the development of psychological studies of labor and the worker in a dynamic professional and organizational environment

National Psychological Journal . No. p.3–8

No. p.3–8

Barabanshchikova V.V. Kuznetsova A.S.

moreDownload PDF

40

How our word will respond

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.126-130

Zuckerman G.A.

moreDownload PDF

718

Life with love as the meaning of being in the existential paradigm of relationships

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. p.119-125

Utrobina V.G.

moreDownload PDF

742

Ecopsychological interactions of young children with other subjects of the social environment

National Psychological Journal 2022. No. 3. c.108-118

Lidskaya E.V. Panov V.I.

moreDownload PDF

700

DSM-5 Personality Disorders: Controversies in the Classification System

Personality Disorders in DSM-5: Controversies in the Classification System - yes, therapy helps!clinical psychology

December 30, 2022

Various updates published by the American Psychiatric Association that produced versions of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders have traditionally been subject to criticism and controversy. Although each new publication has attempted to reach a higher consensus index among experts, the truth is that the existence of a sector of the professional community of psychology and psychiatry cannot be denied. nine0163 shows his reservations about this psychiatric classification system.

Although each new publication has attempted to reach a higher consensus index among experts, the truth is that the existence of a sector of the professional community of psychology and psychiatry cannot be denied. nine0163 shows his reservations about this psychiatric classification system.

With respect to the most recent versions of the DSM (DSM-IV TR 2000 and DSM-5 2013), several well-known authors such as Echeburua of the University of the Basque Country have already demonstrated to this manual, DSM-IV-TR. Thus, one paper with Esbec (2011) showed the need for a complete reformulation of both diagnostic nosologies and the criteria to be included for each of them. According to the authors, this process can have a positive impact on increasing the reliability of diagnoses, as well as reducing the duplication of multiple diagnoses applied to the clinical population. nine0003

- Related Article: 10 Types of Personality Disorders

DSM Classification Issues for Personality Disorders 5

In addition to Echeburúa, other experts in the field such as Rodríguez-Testal et al. (2014) argue that there are various elements that, despite little theoretical support, were on the move from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5 such as categorical methodology in three groups of personality disorders (so-called clusters), rather than opting for a larger approximation where scales of symptomatic severity or intensity are added. nine0003

(2014) argue that there are various elements that, despite little theoretical support, were on the move from DSM-IV-TR to DSM-5 such as categorical methodology in three groups of personality disorders (so-called clusters), rather than opting for a larger approximation where scales of symptomatic severity or intensity are added. nine0003

The authors confirm the existence of problems in the operational definition of each diagnostic label, stating that there is significant overlap between some of the criteria included in some of the mental disorders included in Axis I of the guidelines, as well as the heterogeneity of profiles that can be obtained in different organizations. clinical population under a common diagnosis.

The latter is due to the fact that the DSM requires a minimum number of criteria to be met (half plus one), but does not specify any as mandatory. More specifically, a large correspondence has been found between schizotypal personality disorder and schizophrenia; between paranoid personality disorder and delusional disorder; between personality disorder and mood disorders; Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder, basically. nine0003

nine0003

On the other hand, it is very difficult to distinguish between a continuum of noted personality trait (normality) and an extreme and pathological personality trait (personality disorder). Even if it is indicated that there must be a significant functional deterioration in personal and social indicators of the individual, as well as the manifestation of a stable psychological and behavioral repertoire over time of an inflexible and maladaptive nature, it is difficult and difficult to determine which population profiles belong to the first category or the second. nine0003

Another important point relates to the reliability scores obtained from the scientific studies supporting this classification. just studies to support these data have not been conducted just as the distinction between clusters (aggregates of A, B and C) does not seem to be justified:

Furthermore, as regards the correspondence between the descriptions given for each personality disorder diagnosis, they do not maintain sufficient agreement with the signs observed in clinical patients at consultation, as well as with overlapping clinical pictures that are overly broad. nine0163 The result of all this is an over-diagnosis phenomenon that has a harmful and stigmatizing effect on the patient himself, in addition to complications at the level of communication between mental health professionals who serve the indicated clinical group.

nine0163 The result of all this is an over-diagnosis phenomenon that has a harmful and stigmatizing effect on the patient himself, in addition to complications at the level of communication between mental health professionals who serve the indicated clinical group.

Finally, there does not seem to be enough scientific rigor to confirm the temporal stability of some personality traits . For example, studies show that typical TP symptoms of cluster B tend to decrease over time, while signs of TP clusters A and C tend to to an increase. nine0003

Suggestions for improving the TA classification system

To address some of the difficulties described, Tyrer and Johnson (1996) already proposed a system that added graded scoring to the previous traditional methodology a couple of decades ago. more specifically to establish the degree of presence of a personality disorder :

- Emphasizing personal qualities without taking into account TP.

- Simple personality disorder (one or two TPs of the same cluster). nine0175

- Complex personality disorder (two or more TPs from different clusters).

- Severe personality disorder (in addition, there is major social dysfunction).

Another type of intervention considered at APA meetings during the preparation of the final DSM-5 was to consider including six more specific personality areas (negative emotionality, introversion, antagonism, disinhibition, coercion, and schizotypy), refined from 37 more specific aspects. Both domains and facets were to be rated in intensity on a scale of 0 to 3 to ascertain in greater detail whether each trait was present in a given individual. nine0003

Finally, due to the reduction in overlap between diagnostic categories, overdiagnosis, and elimination of the least supported nosologies at the theoretical level, Echeburúa and Esbec found that the likelihood of APA is decreasing from the ten collected in DSM-IV. -TR up to five as described below along with their most salient features:

-TR up to five as described below along with their most salient features:

1. Schizotypal Personality Disorder

Eccentricity, altered cognitive regulation, unusual perceptions, unusual beliefs, social isolation, limited attachment, avoidance of intimacy, suspicion and anxiety. nine0003

2. Antisocial / psychopathic personality disorder

Insensitivity, aggression, manipulation, hostility, deceit, narcissism, irresponsibility, carelessness and impulsivity .

3. Personality disorder

Emotional lability, self-harm, fear of loss, anxiety, low self-esteem, depression, hostility, aggression, impulsivity and dissociation.

4. Evolutionary personality disorder

Anxiety, fear of loss, pessimism, low self-esteem, guilt or shame, intimacy avoidance, social isolation, limited attachment, anhedonia, social withdrawal and risk aversion.

5. Obsessive-compulsive personality disorder

Perfectionism, rigidity, order, persistence, anxiety, pessimism, guilt or shame , limited attachment and negativism.

As a conclusion

Despite the interesting proposals described here, DSM-V retained the same structure as its previous version A fact that persists in controversy or problems arising from the description of personality disorders and their diagnostic criteria. It remains to be expected that the new formulation of the guidelines may include some of these initiatives (or others that may be formulated in the course of development) to facilitate the implementation of the clinical practice of the psychology and psychology professional group in the future. psychiatry. nine0003

References

- American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th ed.). Washington DC: Author.

- Esbek E. and Echeburua E. (2011). Reformulation of personality disorders in the DSM-V. Spanish Act of Psychiatry, 39, 1-11.

- Esbek E. and Echeburua E. (2015). The DSM-5 Hybrid Classification Model for Personality Disorders: A Critical Review.