Abcd cognitive therapy

Psychology Tools: A-B-C-D Model for Anger Management

The A-B-C-D model is a classic cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) technique developed by one of CBT’s founders, Albert Ellis. When applied effectively, this can help address a variety of emotional difficulties, including anger management problems. This post explains how the model works and how to start using it.

Overview of the A-B-C-D Model in Context of Anger Management

Below is an overview of the A-B-C-D cognitive-behavioral therapy model, using anger as the problem focus:

A = Activating Event

This refers to the initial situation or “trigger” to your anger.

B = Belief System

Your belief system refers to how you interpret the activating event (A). What do you tell yourself about what happened? What are your beliefs and expectations of how others should behave?

C = Consequences

This how you feel and what you do in response to your belief system; in other words, the emotional and behavioral consequences that result from A + B. When angry, it’s common to also feel other emotions, like fear, since anger is a secondary emotion. Other “consequences” may include subtle physical changes, like feeling warm, clenching your fists and taking more shallow breaths. More dramatic behavioral displays of anger include yelling, name-calling and physical violence.

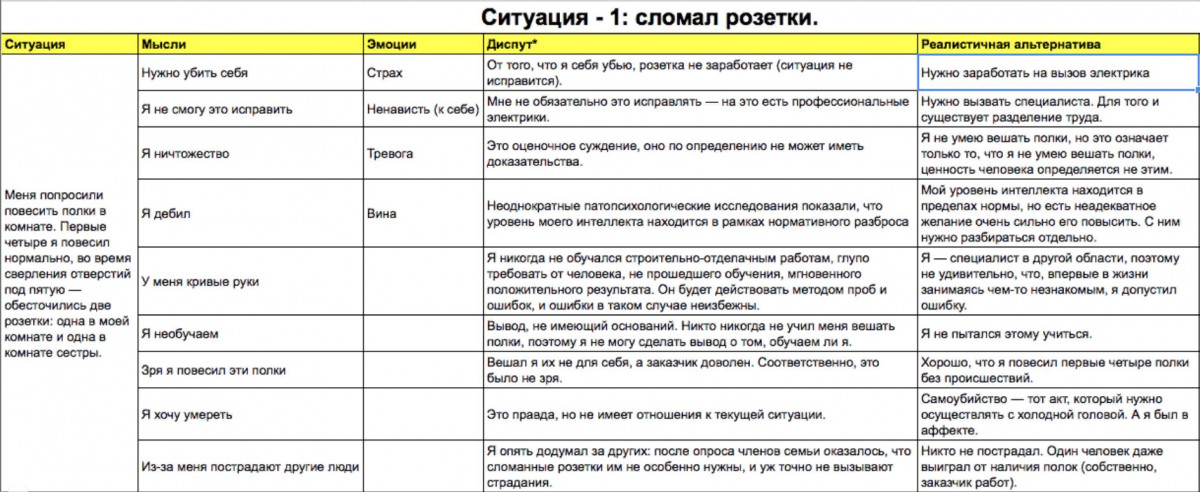

D = Dispute

D refers to a very important step in the anger management process. You need to examine your beliefs and expectations. Are they unrealistic or irrational? If so, what may be an alternative and calmer way to relate to the situation? By “disputing” those knee-jerk beliefs about the situation, you can take a more rational and balanced approach, which can help you control your anger.

Example of the A-B-C-D Model

Let’s look at an example to illustrate how this model can be applied to anger management.

A = Activating Event

You’re driving to work and somebody cuts you off, almost causing a collision. You were already feeling stressed to begin with because you were running late and had a big day ahead of you.

B = Belief System

You think to yourself, “people shouldn’t drive like that,” “I’m a courteous driver, I don’t do that,” “everybody on the road these days is a reckless driver,” “if that car hit me, I would have been really late to work or even worse, I could have gotten injured.”

C = Consequences

After the triggering event (i.e., being cut-off in traffic), you roll down your window and yell an expletive out at the other driver, while giving the bird. You notice that your muscles are tense, your heart rate is high and you feel like you want to hit the steering wheel. You also notice that you feel some fear.

D = Dispute

In response to the triggering situation and its sequelae, rather than reinforce what’s fueling the anger, you could shift your thinking (this is the “D”/dispute part of the model). For example, you could say to yourself: “It’s a bummer that some people drive recklessly, but that’s just a fact of life. Most people actually do obey the rules of the road and I’m glad that I do as well. Who knows, maybe that driver had some emergency that he was responding to…probably not, but you never know. That was scary to almost get hit, but even if we got into a fender bender, I would have eventually gotten to work and probably nothing drastic would have happened because of it.”

Who knows, maybe that driver had some emergency that he was responding to…probably not, but you never know. That was scary to almost get hit, but even if we got into a fender bender, I would have eventually gotten to work and probably nothing drastic would have happened because of it.”

As you can see, using this type of rational self-talk is likely to diffuse some of the anger and help you calm down.

How to Apply this Model to Anger Management

The first step in using this anger management tool is to increase your awareness of what is happening in each step. To review:

A.) Identify what initially triggered the anger

B.) Reflect on how you related to the triggering situation (e.g., what did you say to yourself about it)

C.) Identify all of the specific emotional and behavioral responses that followed

Because our minds work so fast, we can get to C – the consequences – very quickly. So, to start applying this model, it can be helpful to do some analyses of prior situations that have triggered anger by writing down the information in each category. You can use a simple format in this form here: A-B-C-D Model Worksheet.

You can use a simple format in this form here: A-B-C-D Model Worksheet.

Taking the time to write out these steps can help get this learning into the subconscious mind, so that you can later draw upon it in the heat of the moment. In essence, you are practicing anger management tools when you are reviewing prior incidents and coming up with more positive solutions that help calm you down, rather than ratchet up the anger.

Writing out the A-B-C-D information is good practice, even though it’s after the fact. This reflective process helps retrain your mind, by increasing your awareness of patterns and ways to respond to them more effectively. For example, you may start to notice that there are somewhat similar situations that continually bring up anger for you – these are essentially places of “vulnerability” to be aware of and work hard on. After you write down the A-B-Cs, fill-in the D-dispute area, by identifying more rational, realistic and calming things to say to yourself about the situation. You can also put specific behaviors in this box. For example, you might want to write down reminders to yourself like “take some deep breaths” or “count to 10 before saying anything.”

You can also put specific behaviors in this box. For example, you might want to write down reminders to yourself like “take some deep breaths” or “count to 10 before saying anything.”

Oftentimes, people have insight after an angry incident, regretting what they did or said. But, in the moment, things just happen so quickly. This added awareness could help you slow down a bit, which is a key factor in anger management. Being able to pause, take a deep breath and then decide how to respond, rather than reacting to the situation can help you avoid negative consequences of your anger.

Source: Anger Management: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Manual” by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

What is Albert Ellis' ABC Model in CBT Theory? (Incl. PDF)

Albert Ellis’s ABC Model is a significant part of the form of therapy that he developed, known as Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy (REBT).

REBT served as a sort of precursor to the widely known and applied Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and the ABC Model is still commonly used as a treatment in CBT interventions.

This article will cover what the ABC Model is, how it and REBT relate to CBT, and finally, how the ABC Model works to target dysfunctional thoughts and beliefs.

Before you read on, we thought you might like to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will provide you with a detailed insight into Positive CBT and will give you the tools to apply it in your therapy or coaching.

This Article Contains:

- A Brief History on CBT & REBT

- What Is The ABC Model?

- How To Treat Cognitive Distortions & Irrational Beliefs

- 5 ABC Model Worksheets (PDF)

- A Take-Home Message

- References

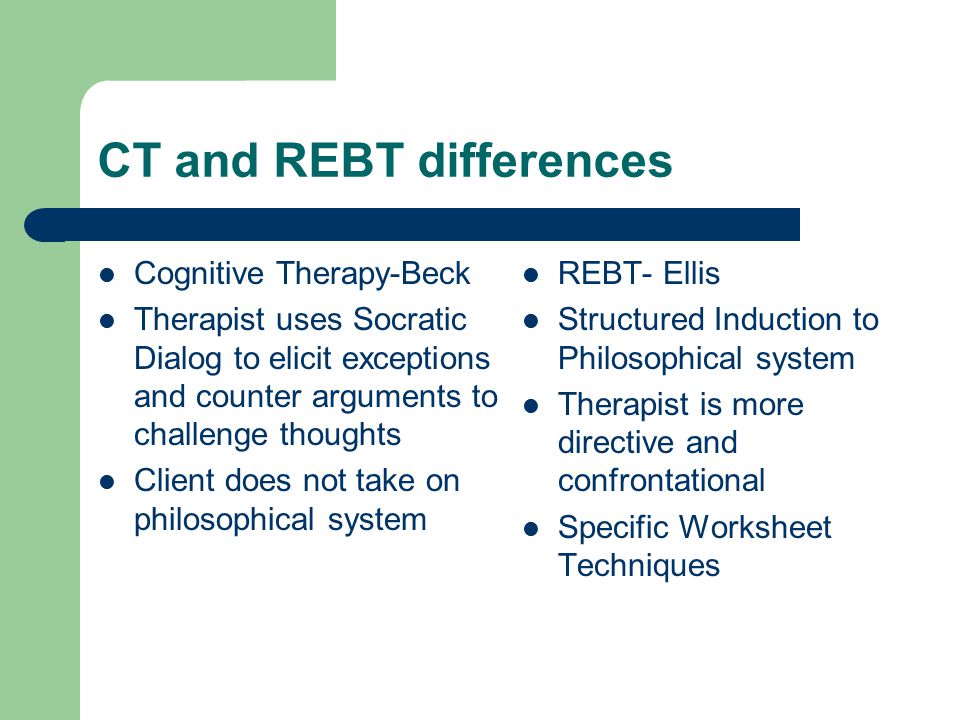

A Brief History on CBT & REBT

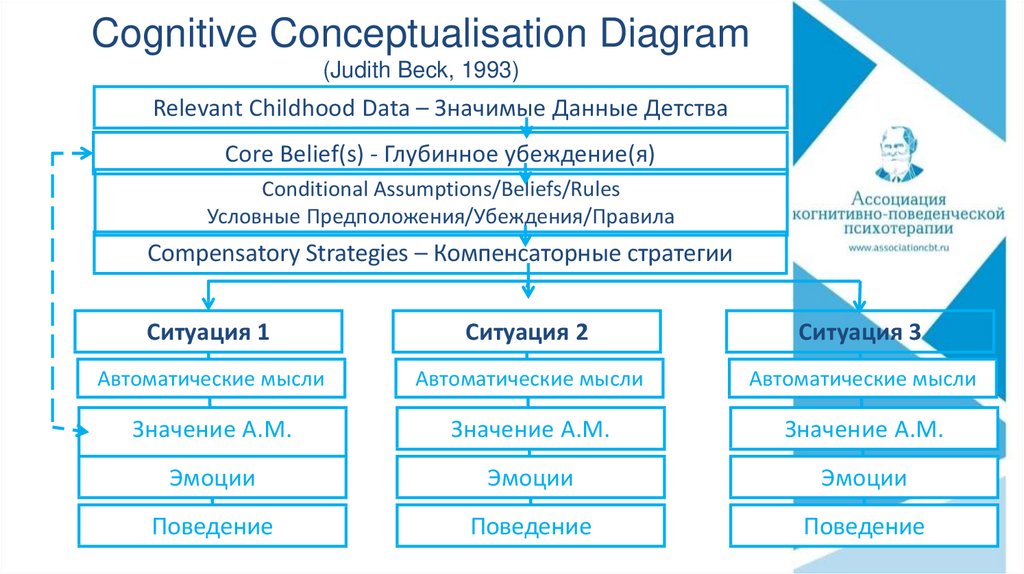

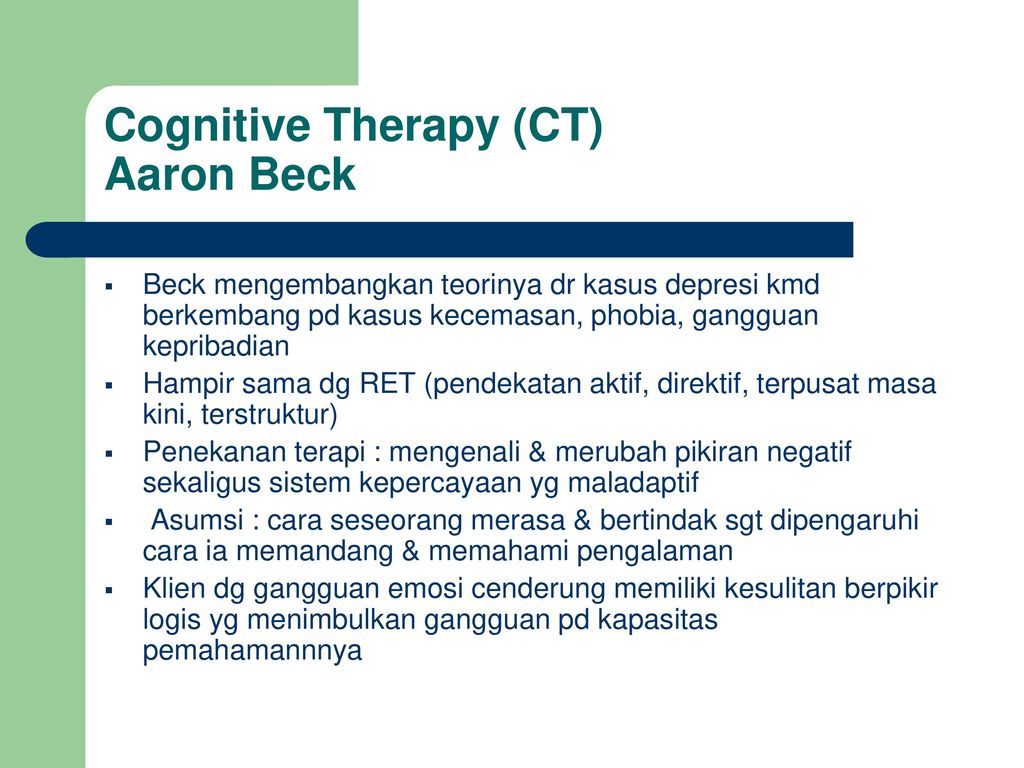

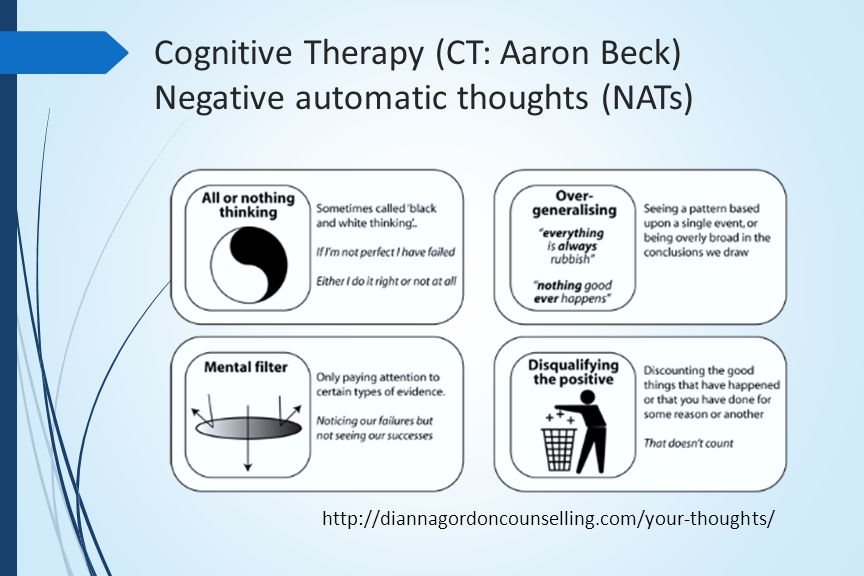

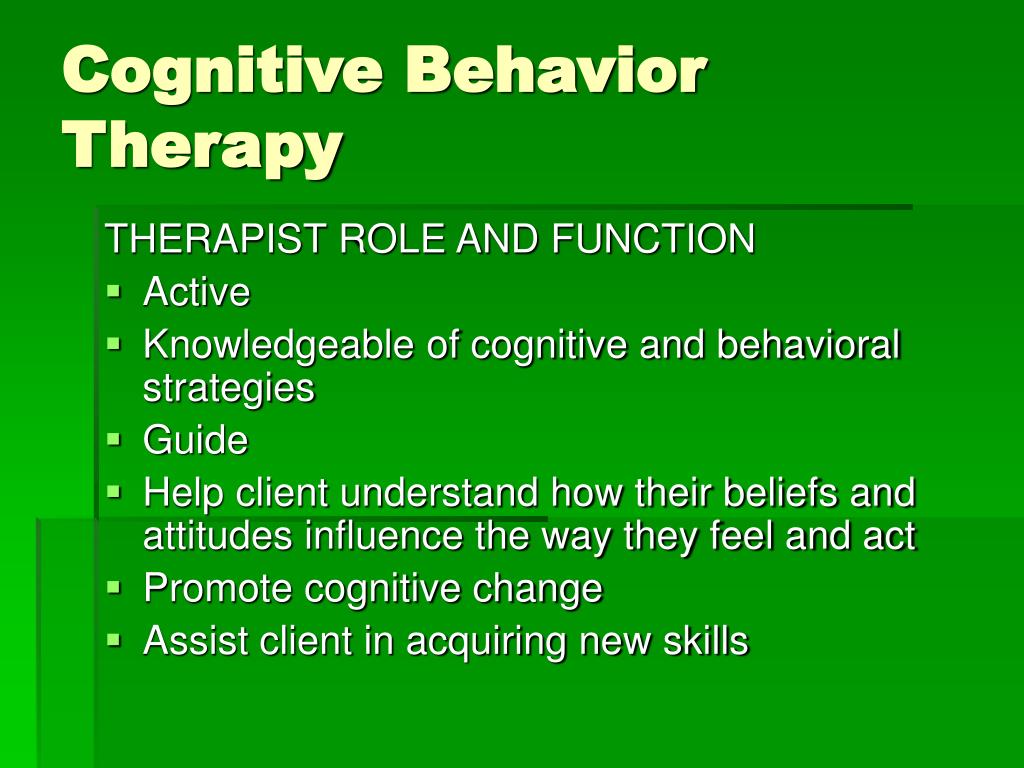

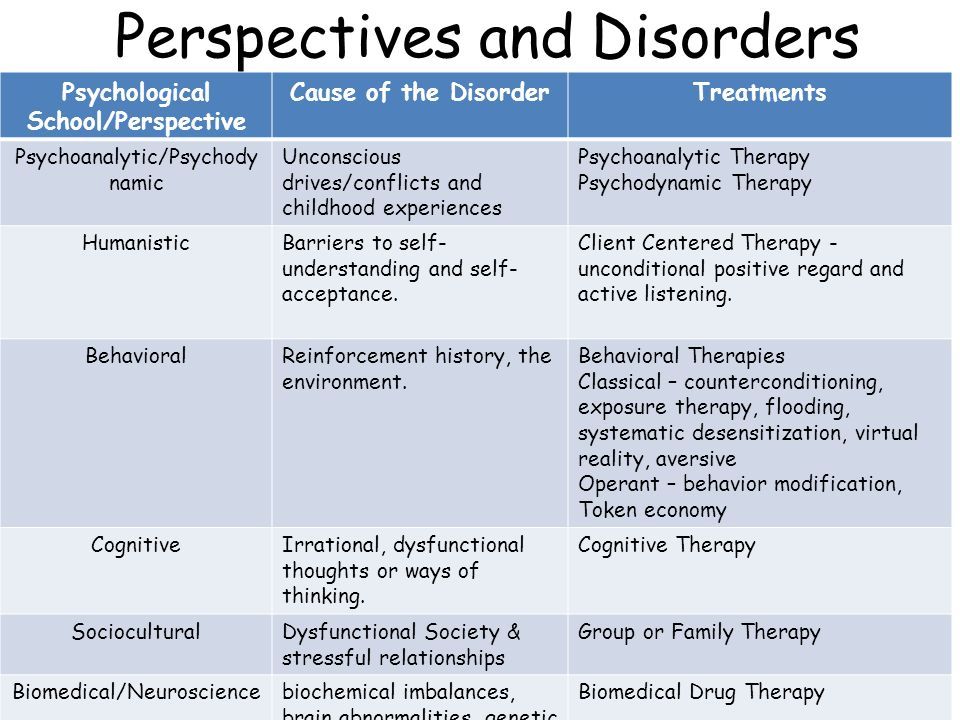

Modern CBT has its direct roots in Aaron Beck’s Cognitive Therapy (CT), which he developed when he decided that contemporary treatments for depression focused too much on past events rather than current beliefs (such as the belief that one is not good enough or not worthy of love and respect. ) (Beck, 2011).

) (Beck, 2011).

Beck’s CT has its own roots, though, and Albert Ellis’s REBT is one of those roots. Specifically, REBT is “the original form and one of the main pillars of cognitive-behavioral therapies (CBT)” (David et al., 2018).

In other words, REBT is both a precursor to and a form of CBT; it is still used today as a standalone form of therapy in some cases. The main thing that sets REBT and CBT apart from preceding cognitive therapies is that REBT and CBT both target beliefs as a fundamental course of treatment.

For the purposes of this article, we can consider REBT to be a subset of CBT, and we can consider the ABC Model to be a core component of many treatment plans in both REBT and CBT.

What Is The ABC Model?

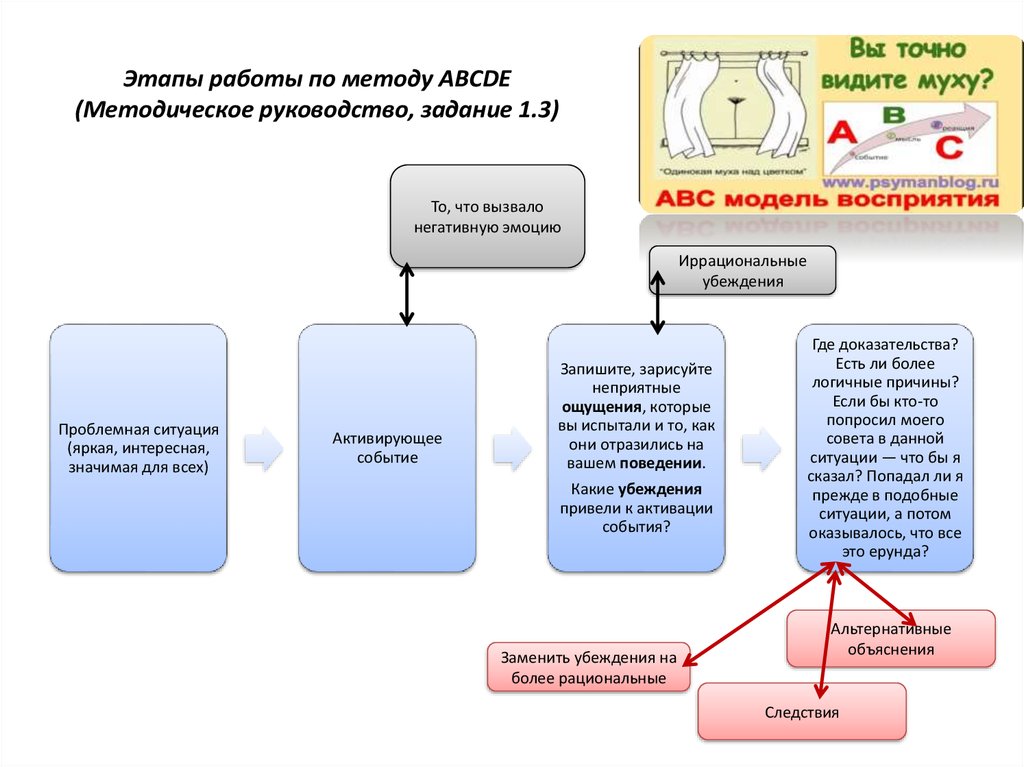

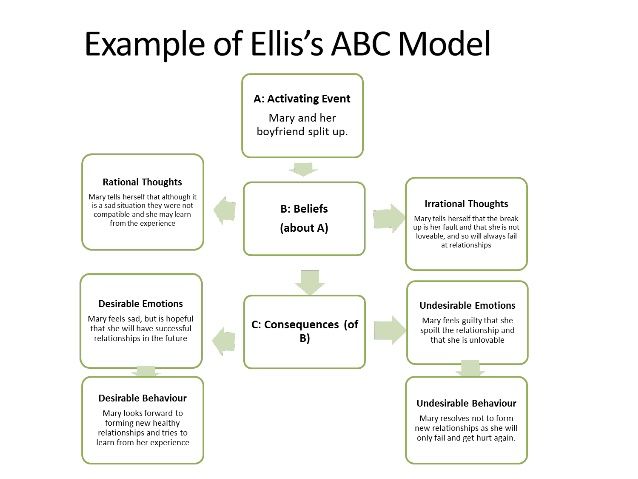

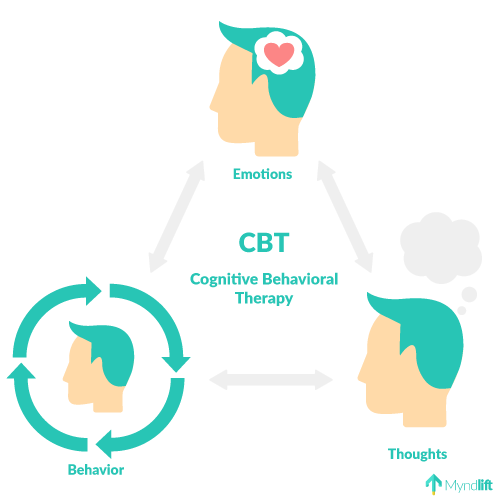

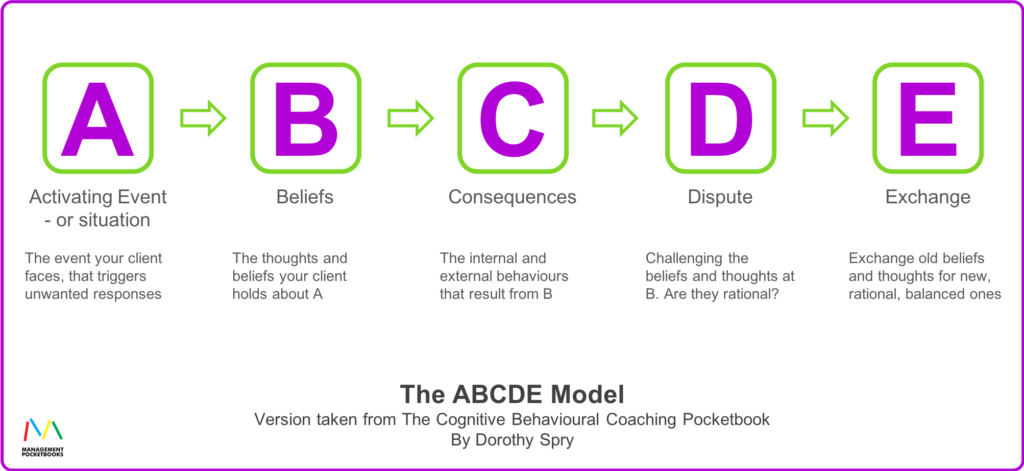

The basic idea behind the ABC model is that “external events (A) do not cause emotions (C), but beliefs (B) and, in particular, irrational beliefs (IB) do” (Sarracino et al., 2017).

Another way to think about it is that “our emotions and behaviors (C: Consequences) are not directly determined by life events (A: Activating Events), but rather by the way these events are cognitively processed and evaluated (B: Beliefs)” (Oltean et al. , 2017).

, 2017).

Further, the model states that it’s not a simple matter of an unchangeable process in which events lead to beliefs that result in consequences; the type of belief matters, and we have the power to change our beliefs. REBT divides beliefs into “rational” and “irrational” beliefs. The goal when using the ABC model in treatment is to help the client accept the rational beliefs and dispute the irrational beliefs.

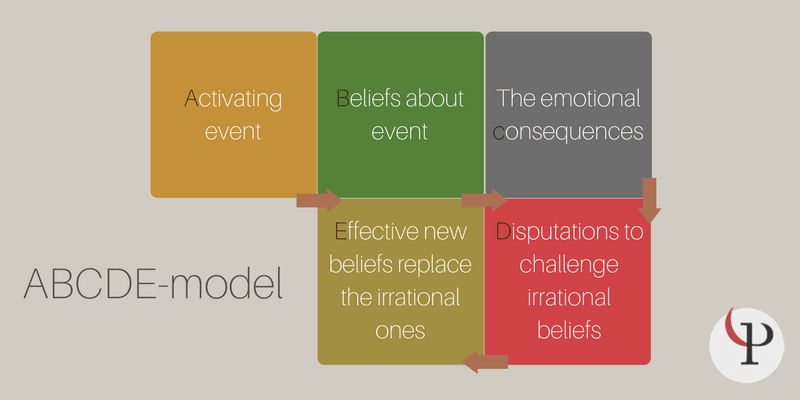

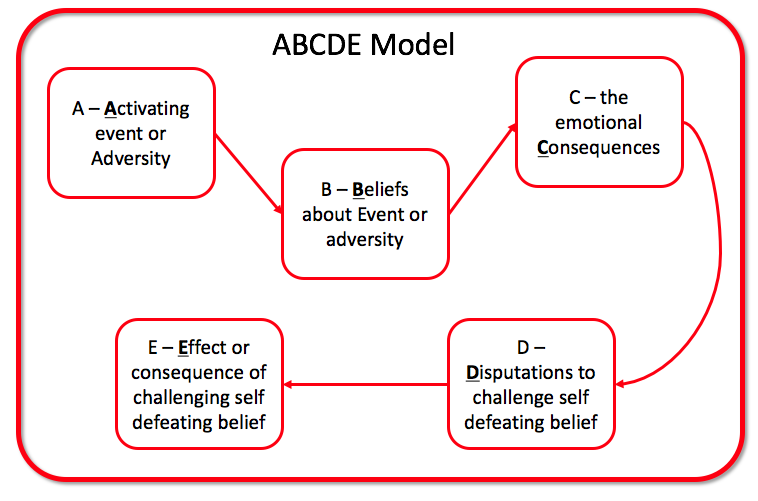

This disputation process is what results in the model often being referred to as the “ABCDE” Model. In this updated model, the D stands for the Disputation of Beliefs and E stands for the new Effect, or the result of holding healthier beliefs (Jorn, 2016).

Disputation is not an original part of the ABC Model, as it happens outside of the “ABC” part (such as in the case of disputing an irrational belief to turn it into a rational belief), and the new Effect is another subsequent factor: the result of that disputation.

Calling it the “ABCDE” Model instead of the “ABC” Model simply makes these two steps more explicit, but they are present regardless of what one calls it.

In these models, this is what a typical series of thoughts might look like:

- A: Activating Event (something happens to or around someone)

- B: Belief (the event causes someone to have a belief, either rational or irrational)

- C: Consequence (the belief leads to a consequence, with rational beliefs leading to healthy consequences and irrational beliefs leading to unhealthy consequences)

- D: Disputation (if one has held an irrational belief which has caused unhealthy consequences, they must dispute that belief and turn it into a rational belief)

- E: New Effect (the disputation has turned the irrational belief into a rational belief, and the person now has healthier consequences of their belief as a result)

How To Treat Cognitive Distortions & Irrational Beliefs

When it comes to applying the ABC Model (whether that’s in CBT, REBT, or any other form of therapy or coaching):

A key element is helping clients see the connection between an event that may serve as a trigger, and how irrational evaluations may cause emotional and/or behavioral consequences that often in turn lead to increased distress or conflict.

(Malkinson & Brask—Rustad, 2013)

This is the main idea behind the ABC Model and a popular notion in most forms of therapy; one does not necessarily have to change their environment to become happier and healthier, they simply have to recognize and change their reactions to their environment. This takes a little self-awareness, but that’s something we are all able to do with a bit of effort.

This theory is supported by the fact that three 45-minute learning sessions about the ABC Model have been shown to be effective in reducing symptoms of depression and anxiety as well as reducing dysfunctional thinking while increasing self-esteem and feelings of hope (Saelid & Nordahl, 2017).

This finding is even more impressive with the added note that 90% of the participants in this study “reported not having had any previous knowledge of the links between thoughts, feelings, and behavior.” Simply becoming more aware of the relationship between them made it a powerful tool!

In fact, the ABC Model partially works by making clear this connection between their beliefs and their emotions, which helps people see that the events around them do not need to dictate their emotions.

The ABC Model has not only been successful in treating anxiety, depressive symptoms, and self-esteem issues; it has been shown to target anger issues as well effectively (Fuller et al., 2010). This treatment is especially promising because participants in the study were able to deal with their anger while confronting potential anger triggers, rather than by merely avoiding anger triggers.

After all, there are some anger triggers we simply can’t avoid if we want to live a full, meaningful life–things like traffic, confrontations with people we love, etc.

In cases of unhealthy anger and other instances of unhealthy negative emotions, the key thing to understand is the difference between rational and irrational beliefs (Ziegler & Smith, 2004). However, in certain situations, the ABC Model cannot merely be deployed as-is.

In mild situations, the ABC Model works by turning irrational beliefs about activating events into rational beliefs, which in turn leads to better consequences and emotions. In some cases, such as grief, it is not about turning irrational beliefs into rational beliefs, but it is instead about legitimizing, validating, and normalizing the beliefs that are present.

In some cases, such as grief, it is not about turning irrational beliefs into rational beliefs, but it is instead about legitimizing, validating, and normalizing the beliefs that are present.

For example, treating someone who is grieving, such as someone in mourning from losing a child, requires a modification. This is because, in the case of grief, “‘logical’ disputation is not useful, but instead, legitimizing and normalizing is used: losing a child is in and by itself not logical” (Malkinson & Brask-Rustad, 2013).

Grief is not an emotion that heeds logic, and it should not be attacked with the same vigor with which things like anger and negative self-talk can be confronted. In such cases, the ABC model should be applied with care, and only after validating the difficult emotions the client is facing.

In less acute cases, where the issues are more garden-variety irrational beliefs, this model has great success. Even the most rational and reasonable among us have struggled with irrational beliefs, it’s simply a matter of degree.

These irrational beliefs must be examined and confronted if the client is to experience relief from them, and that is what the ABC model does. There are many types of irrational beliefs–known formally as “cognitive distortions”–that have been identified, and all can benefit from this treatment.

The image below gives a short demonstration on the ABC model in action. In this case, the negative event is that a student doesn’t get selected for choir after her audition. The event (A) leads to this thought: “I have a terrible voice. I’m never going to be any good at singing.” This is the belief (B), which results in the consequences (C): the student is sad about her singing and gives up practicing instead of continuing to work on it.

Let’s expand on this idea with an example of the ABC model in action during treatment for a cognitive distortion. Imagine a counselor is working with a woman who suffers from black-and-white thinking; when she makes a mistake, she thinks to herself, “I’m such a failure. I’m not good at anything.”

I’m not good at anything.”

The counselor informs her about the ABC model and walks her through how to tackle it.

Unexamined, her cognitive distortion plays out like this:

A – Activating Event – the client makes a mistake.

B – Belief – the client has a thought that says she is a failure and that she is not good at anything. She accepts it uncritically.

C – Consequence – the client feels awful about her mistake and about herself in general, leading to depressive symptoms and making it tough for her to try again.

With her counselor’s help, the woman realizes that she is not a helpless victim to this process; she can do something about the “B” part of the model. She does not need to accept the thought as true, she can decide that it’s just a thought and treat it as such.

Her new process looks like this:

A – Activating Event – the client makes a mistake.

B – Belief – the client has a thought that says she is a failure and that she is not good at anything.

C – Consequence – the client feels awful about her mistake and about herself in general, but she remembers that she can question the cognitive distortion.

D – Disputation – she questions the thought. She tells herself that everyone makes mistakes and that one mistake does not mean she is worthless or that she is not good at anything.

E – New Effect – the client accepts that we all make mistakes and replace the negative thoughts with this positive thought. She commits to learning from her mistake and trying again in the future.

You can see the important work happening in D (Disputation). The client has realized that her thoughts are simply thoughts, they do not determine who she is. She takes control by rejecting the thought and purposely replacing it with a more realistic and more positive thought.

5 ABC Model Worksheets (PDF)

Make use of these worksheets to build appropriate ABC models.

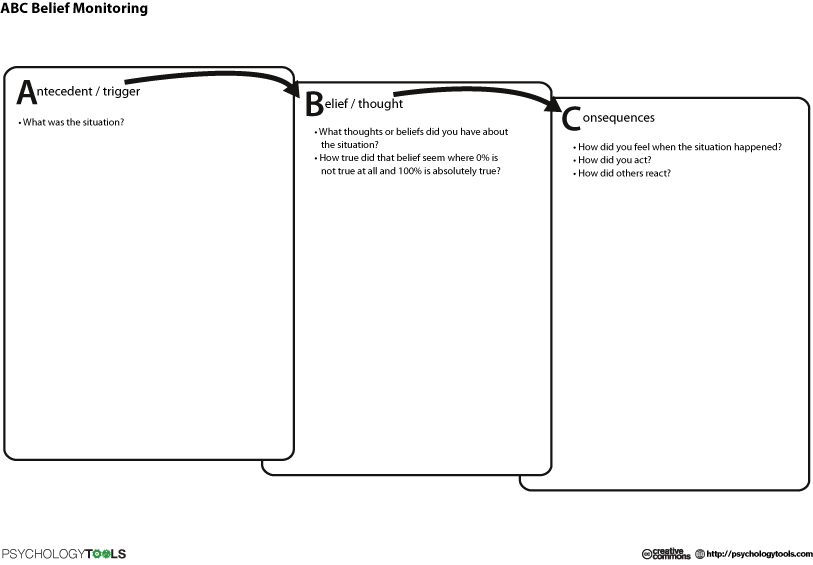

ABC Model

This extremely short worksheet simply lists the five steps of the ABC model in descending order.

It starts with the Activating Event — something happens to you or in the environment around you — where you have space to write down your activating event.

Next is Beliefs — you have a belief of interpretation regarding the activating event — followed by space for you to identify your own belief or interpretation that you would like to change.

The third step is Consequences, described as “Your belief has consequences than include feelings and behaviors.” Here you can write down what happens to you as a result of the belief you identified.

Next, the worksheet describes Disputations of Beliefs: “Challenge your beliefs to create new consequences.” This is where you look critically at the belief you wrote down and see whether it’s accurate and helpful. If it is not accurate, not helpful, or neither accurate nor helpful, this is your opportunity to craft a new belief.

Finally, the worksheet ends with Effective New Beliefs: “Adoption and implementation of new adaptive beliefs. ” This is where you have a chance to create new, more helpful beliefs and think about how you are going to incorporate them. It might help to write out a commitment to choosing one of your new beliefs the next time a specific activating event happens.

” This is where you have a chance to create new, more helpful beliefs and think about how you are going to incorporate them. It might help to write out a commitment to choosing one of your new beliefs the next time a specific activating event happens.

This worksheet does not offer too much explanation but could be a good resource to hand out in an office or classroom when you have time to walk your student or client through it.

Understanding our Response to Stress and Adversity Handout

This three-page informational handout, which is part of a more extensive resource created by Dartmouth College, is a great standalone way to learn about the ABC Model. The worksheet starts with a very relatable scenario (being stuck in traffic) and discusses why we have different responses to stress. It clearly and briefly explains what the ABC Model is, provides an example, and describes how to use it effectively.

This is a good option for someone looking to quickly learn about the ABC Model and how to use for themselves or to give their clients to take home.

ABC Problem Solving Worksheet

This worksheet serves as a prompt to help someone work through the ABC Model in the moment when they are experiencing a challenging belief and difficult consequences.

It’s a detailed worksheet to walk through each step, which is great if you don’t have time to explain everything in a session or if your client isn’t big on writing down notes. It also changes the C and the B, which can be an exciting way to look at the model. We typically notice the consequences before the beliefs so that this format can be more intuitive to people new to the ABC model.

There are several questions for each step, including:

- Activating Event

- What is the Activating event?

- What has happened?

- What did I do?

- What did others do?

- What idea occurred to me?

- What emotions was I feeling?

- Consequence

- Am I feeling anger, depression, anxiety, frustration, self-pity, etc.?

- Am I behaving in a way that doesn’t work for me (drinking, attacking, moping, etc.

)?

)?

- Beliefs (Dysfunctional)

- What do I believe about the Activating event?

- Which of my beliefs are my helpful/self-enhancing beliefs, and which are my dysfunctional/self-defeating beliefs?

- Dispute

- What is the evidence that my belief is true?

- In what ways is my belief helpful or unhelpful?

- What helpful/self-enhancing belief can I use to replace each self-defeating or dysfunctional belief?

- Effective New Belief and Emotional Consequence

- What helpful/self-enhancing new belief can I use to replace each self-defeating or dysfunctional belief?

- What are my new feelings?

This would be a great resource to hang in a classroom or office as a reminder of the connection between beliefs and emotions. This worksheet is useful for people brand new to cognitive therapy or cognitive distortions because it does not require any prior knowledge about the ABC Model to use it successfully.

CBT Exercise – The ABCD Method

This exercise is similar to the above worksheet, as it also walks one through the ABC Model whenever one may need it. It may be more appropriate for adults; however, while the preceding worksheet may be more suitable for younger people (only because it is more colorful and includes more specific prompts), this worksheet breaks it down in a slightly different way:

- Activating Event – What happened? What’s stressing me out?

- Belief – What is my negative self-talk? What distorted or irrational thinking style am I using? What negative belief am I clinging to? What interpretations am I making?

- Consequence – What am I feeling? What is my behavior as a result of my beliefs?

- Dispute – Counter-thought. What realistic and grounding statement can I use instead? Is there an alternative way of thinking here that is reality-based?

For each section, there are multiple spaces to write about what happened, what you’re thinking, what the consequences are, and what better alternative thoughts would be.

This worksheet can also help regardless of one’s prior knowledge of the ABC Model.

ABC Functional Analysis Worksheet

This final worksheet presents an alternative version of the ABC Model that draws on similar cause-and-effect processes. The difference is that this worksheet does so at the level of one’s behaviors, thereby serving as a useful supplement to the worksheets above, which focus on cognitions and emotions.

If your clients find mapping the links between activating events and beliefs challenging to begin with, starting at the level of their behaviors using this worksheet may serve as a useful stepping stone to exploring self-defeating beliefs and emotional consequences.

This exercise may also be useful if your client’s motivation for engaging your services involves addressing specific problematic behaviors.

The worksheet itself comprises three columns to be filled in. These columns are labeled as follows:

- (A)ntecedents – What factors preceded the problematic behavior?

- (B)ehavior – What is the problematic behavior?

- (C)onsequences – What was the outcome of the problematic behavior?

It is recommended that you begin the worksheet at the ‘Behavior’ column, then work to assess the antecedents and consequences in turn.

A Take-Home Message

The main takeaway from the ABC Model is that while environmental factors can undoubtedly harm our lives, we do have some control over how we react and respond to those factors. For the most part, the more positively we respond, the more positive our outcomes will be.

This does not mean that no harm can come to someone with a positive attitude, but it does mean that a positive attitude can get someone through rough times quicker and more effectively. Having a positive attitude also does not cost anything, so it cannot hurt to try to keep a positive outlook.

In the true spirit of positive psychology, we would all be better off if we remembered the principles of the ABC Model. In many situations, we may not be able to change the environmental factors (or Activating Events) that occur in our daily lives; however, we can keep in mind the immense power of our own beliefs in shaping our everyday experiences.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. For more information, don’t forget to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free.

For more information, don’t forget to download our 3 Positive CBT Exercises for free.

- Beck, JS (2011). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond (2nd ed.), New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

- David, D., Cotet, C., Matu, S., Mogoase, C., Stefan, S. (2018). 50 years of rational-emotive and cognitive-behavioral therapy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 304-318.

- Ellis, A. (2000). Can rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT) be effectively used with people who have devout beliefs in God and religion? Professional Psychology-Research and Practice, 31(1), 29-33.

- Fuller, J.R., DiGiuseppe, R., O’Leary, S., Fountain, T., Lang, C. (2010). An Open Trial of a Comprehensive Anger Treatment Program on an Outpatient Sample. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 38(4), 485-490.

- Jorn, A. (2016). Rational Emotive Behavior Therapy. Psych Central. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.

com/lib/rational-emotive-behavior-therapy/

com/lib/rational-emotive-behavior-therapy/ - Malkinson, R., Brask-Rustad, T. (2013). Cognitive Behavior Couple Therapy-REBT Model for Traumatic Bereavement. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 31(2), 114-125.

- Oltean, H.R., Hyland, P., Vallieres, F., David, D.O. (2017). An Empirical Assessment of REBT Models of Psychopathology and Psychological Health in the Prediction of Anxiety and Depression Symptoms. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 45(6), 600-615.

- Saelid, G.A., Nordahl, H.M. (2017). Rational emotive behavior therapy in high schools to educate in mental health and empower youth health. A randomized controlled study of a brief intervention. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 46(3), 196-210.

- Sarracino, D., Dimaggio, G., Ibrahim, R., Popolo, R., Sassaroli, S., Ruggiero, G.M. (2017). When REBT Goes Difficult: Applying ABC-DEF to Personality Disorders. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 35(3), 278-295.

- Ziegler, D.J., Smith, P.N. (2004). Anger and the ABC model underlying Rational-Emotive Behavior Therapy. Psychological Reports, 94(3), 1009-1014.

Cognitive Therapy: Thinking Out Loud | PSYCHOLOGIES

33,377

Each of us perceives ourselves, the people around us, and the world in a very special, individual way. And this makes us very different from each other: we don’t just react to a color or a sound, we don’t just automatically register the meaning of the words we hear, but we actively choose what is important only to us.

For example, the memories of spouses about their acquaintance often sound like stories about completely different events: she remembers how both were dressed and what they talked about that day, and he remembers how worried and uncomfortable he felt. Cognitive psychotherapists believe that by understanding how a person perceives and “processes” information, how he forms his own view of the world, it is possible to determine why he encounters specific psychological problems. And, by changing the way of thinking, these problems can be solved.

And, by changing the way of thinking, these problems can be solved.

Game of the mind… with reality

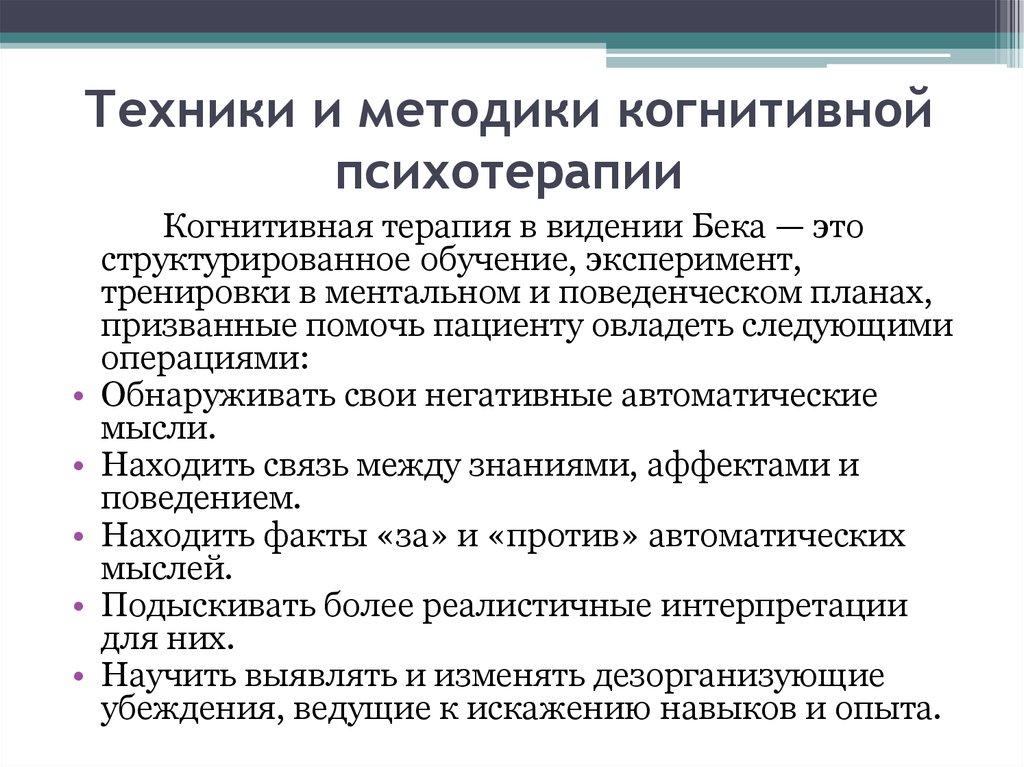

Outstanding American psychologist Aron Beck, the founder of cognitive psychotherapy, combined in his method the ideas of psychoanalysis about the influence of the unconscious on our thoughts and actions and behaviorists that a new type of reactions to external events can be taught to a person. Aron Beck believed that psychological problems arise due to the fact that we make incorrect conclusions that can greatly distort real events.

In addition, each of us not only perceives and evaluates the situation, but also mentally continuously comments on what he thinks about, what he feels. Such comments Beck called "automatic thoughts" and believed that they can also be the source of our experiences and inappropriate behavior. All passions and painful emotions arise from wrong conclusions. We build cause and effect relationships, but they are just a game of our mind, and therefore can be erroneous. It's not that the world is bad, argued Aron Beck, but that we see it as such.

It's not that the world is bad, argued Aron Beck, but that we see it as such.

Today, Aron Beck's cognitive therapy is one of the main methods of the cognitive-behavioral approach in psychotherapy, which is effective in working with many psychological problems.

Who needs it

Cognitive therapy is effective in dealing with many personal problems: anxiety, self-doubt, difficulties in establishing relationships, eating disorders ... Helps those who have experienced violence, stress. The method of cognitive therapy can be applied both in individual work and in work with families.

Seeing differently

How we think ultimately determines how we feel, how we treat ourselves and others, how we make decisions, and how we act. For example, upon discovering that a new acquaintance is taciturn, some will explain this as a reluctance to communicate and give up trying to establish contact. Others will perceive silence as evidence of shyness and will try to encourage the interlocutor. And still others will not attach any importance to how a person speaks, but will pay more attention to his appearance. If a person sees only one facet in a situation, picks out only familiar features in the stream of events, this impoverishes his life, deprives him of freedom of choice and can lead to unpleasant misunderstandings.

And still others will not attach any importance to how a person speaks, but will pay more attention to his appearance. If a person sees only one facet in a situation, picks out only familiar features in the stream of events, this impoverishes his life, deprives him of freedom of choice and can lead to unpleasant misunderstandings.

22-year-old Svetlana felt a strong resentment towards everyone she came into contact with. One day, the father-in-law remarked: “What a pale little thing you are!” These words seemed insulting: for her, they meant that the interlocutor did not respect her - “after all, they don’t talk to women like that.” And in other situations, she took offense every time she thought she had been treated without due respect. The store clerk didn’t smile, the teacher didn’t set the test “automatically” – Svetlana seemed to be specifically looking for something to be offended by, and, of course, she found it. It took her several months of work with a psychotherapist to stop seeing evil intent in other people's actions and begin to react more calmly.

One-sided interpretation of events, distortions of thinking, as a rule, are accompanied by unpleasant experiences — fear, irritation, resentment, guilt. Unsubstantiated generalizations: “If a friend hurt me, then all men are traitors” and polarized thinking: “Either hit or miss” (either perfectly good or disastrously bad) limit our perception. Personification is another way of perception (when a person takes everything that happens on his own account: “She frowns - I did something wrong ...”), which makes life unbearable. At the same time, each of us, having got rid of such stereotypes of thinking, is able to look at the event from different points of view, to see it in its entirety.

Stages of work

The client, together with the psychotherapist, explores under what circumstances the problem manifests itself: how “automatic thoughts” arise and how they affect his ideas, experiences and behavior. He learns to soften rigid beliefs, to see different facets of a problem situation. Homework - exercises offered by the therapist allow the client to consolidate new skills. So gradually he learns, without the support of a therapist, to live in accordance with new, more flexible views.

Homework - exercises offered by the therapist allow the client to consolidate new skills. So gradually he learns, without the support of a therapist, to live in accordance with new, more flexible views.

Cognitive therapy is usually short-term (5-10 to 24 sessions 1-2 times a week). The number of meetings depends on the willingness of the client to work, on the complexity of the problem and the conditions of his life.

Where does this thought come from?

In childhood, when we study the world, some conclusions and connections become the most important for us and further determine our ideas about how people should behave, how we should interpret their actions, how we should act in certain situations. When these beliefs are too general and categorical (for example, “All people should be kind” or “If I can’t do the best, then I’m a failure”), they limit our freedom of choice, deprive us of the ability to realistically evaluate ourselves and those around us, and do not allow us to be ourselves. It is important for a cognitive therapist in his work to understand: how, under the influence of what events, such beliefs were formed? To do this, he analyzes the past of the client, including his childhood experience.

It is important for a cognitive therapist in his work to understand: how, under the influence of what events, such beliefs were formed? To do this, he analyzes the past of the client, including his childhood experience.

32-year-old Marina felt physically very fragile, worried about any, even the slightest ailment. As a child, she suffered the usual set of childhood illnesses. Where did anxiety come from? During psychotherapy, it turned out that the pediatrician in the clinic every time met her with the words: “Here we have a bouquet of diseases ...”

Over time, my mother quit her job and devoted herself to treating her daughter. Long hours spent with doctors, endless visits to treatment rooms made Marina believe that she was really seriously and hopelessly ill. Once she heard her father say that he wanted a second child, and her mother screamed loudly: “You are crazy, we already have a disabled child!”

She lived with this self-image. She managed to regain her strength and feel like a healthy person only after, in the course of psychotherapy, she gradually saw her life differently: Marina graduated from mathematical and music schools, then a difficult university. She was finally able to give up her childhood beliefs about her illness and stopped ignoring her huge energy resource.

She was finally able to give up her childhood beliefs about her illness and stopped ignoring her huge energy resource.

However, our beliefs can be quite stable (rigid): in working with a cognitive psychotherapist, we are not always able to completely change them, but we can become more open to alternative ideas, learn to behave more flexibly.

Fifth Column Exercise

By analyzing what happens to us in a problem situation, we can learn to respond differently.

Draw a sheet of paper into five columns. In the first, describe the problem, for example: "I'm afraid to speak in public." In the second, note what feelings you have in this situation (anxiety, shame). Try to catch the “automatic” thoughts that arise (“I can’t speak clearly and distinctly”) and write them down in the third column. In the fourth column, write down what beliefs led you to have these "automatic thoughts." For example, you are sure that "all people laugh at those who are insecure." Then, in the fifth column, enter the cons—short and concise statements that challenge the statements in the fourth column. For example, "If I make a mistake, nothing terrible will happen" or "I am able to explain to others what I want." Use these statements as support for a new way of interpreting problem situations. Repeat these phrases to yourself to stop the flow of "automatic thoughts".

For example, "If I make a mistake, nothing terrible will happen" or "I am able to explain to others what I want." Use these statements as support for a new way of interpreting problem situations. Repeat these phrases to yourself to stop the flow of "automatic thoughts".

Open conversation

From the very beginning, the cognitive therapist "plays with open cards": he not only discusses his problem with the client, but also talks about the possible causes of it, about how it can be dealt with. 44-year-old Ekaterina, who sought help for depression and was confident in the exceptional nature of her problem, on the instructions of a psychotherapist, began to look for information about famous people who suffered from this disorder. Almost half of the classics of Russian culture were on the list. This fact amused her, talking about him, she exclaimed: “There are too many of us like that!” The realization that her case was not extraordinary was a turning point in therapy and enabled Ekaterina to cope with her depression.

The therapist is a patient and benevolent partner and explores with the client how the misinterpretation of events gives rise to emotional, physiological and behavioral reactions, that is, how the problem arises. And above all, he believes that each person is able to look at the situation differently.

Reserve for the future

The goal of cognitive therapy, in the words of the philosopher Bertrand Russell, is "to break free from the tyranny of early beliefs." After all, they are not biologically determined (like, for example, eye color), which means that we can change, master new behavior, become more flexible in perceiving ourselves and other people. Of course, unpleasant events and experiences cannot be completely excluded from life.

The task of cognitive therapy is precisely to teach a person to understand how he comprehends the situation, interprets it, what he notices and what he ignores, why such an assessment causes him certain feelings and actions. This allows you to cope with yourself without cutting off the path to solving the problem, without depriving yourself of contact with other people.

This allows you to cope with yourself without cutting off the path to solving the problem, without depriving yourself of contact with other people.

About the expert

Natalya Garanyan — cognitive and family therapist, senior researcher at the Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry.

Text: Yuliana Puchkova Photo source: Getty Images

New on the site

How to stay in a state of psychological comfort at any time: 7 rules how to break up with a married lover

Mental clues: what your anger says

“I wrote a book and my friends turned their backs on me. Is it out of jealousy?

“People always call me ‘you’: how can I explain that this is a violation of my boundaries?”

What do recurring dreams hide

How to let a child realize his talent without hurting him: opinions of psychologists and the jury of the Blue Bird competition

Cognitive psychotherapy. What is Cognitive Psychotherapy? The concept and definition of the term "Cognitive Psychotherapy" - Glossary

Glossary. Psychological dictionary.

Psychological dictionary.

- A

- B

- B

- G

- D

- F

- Z

- and

- K

- L

- M

- H

- O

- P

- R

- C

- T

- W

- F

- X

- C

- H

- W

- E

- I

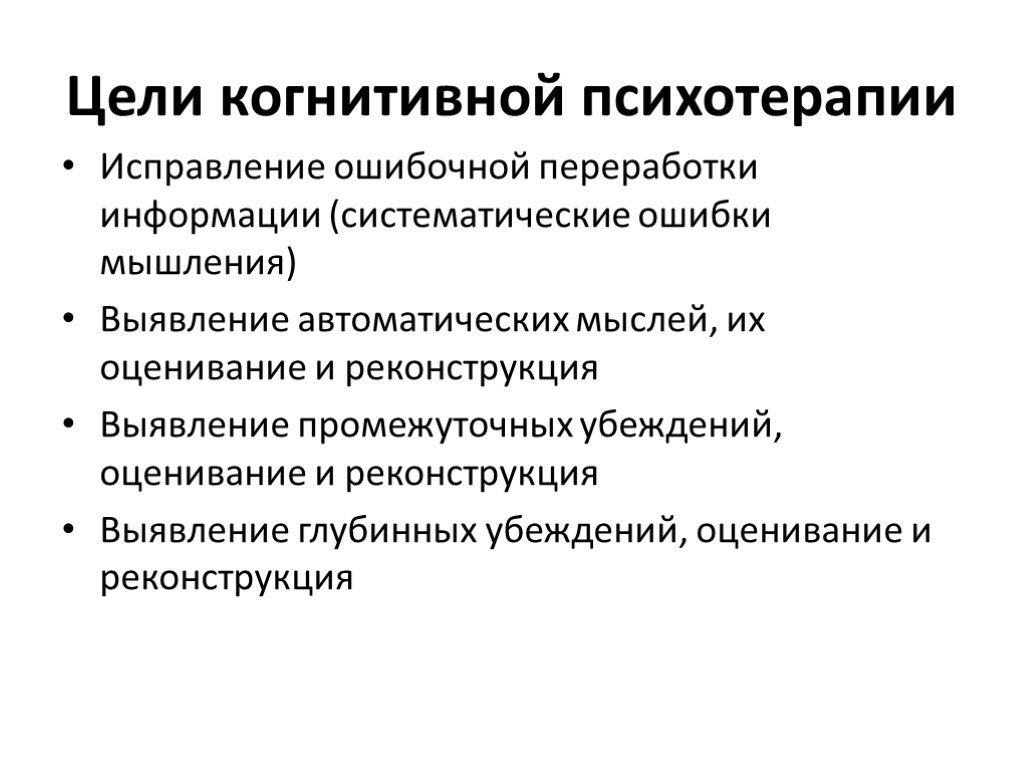

Cognitive psychotherapy - a psychotherapeutic method aimed at improving the personal and social adaptation of the client through the awareness and correction of non-adaptive thought patterns (beliefs). Cognitive psychotherapists work on the principle that by understanding how a person perceives and processes information, you can determine why he encounters specific psychological problems. And by changing the habitual way of thinking, these problems can be solved. The creator of the method Aaron Beck (Aaron Beck, 1921) believed that psychological problems arise due to the fact that we make incorrect conclusions that can greatly distort real events. At the same time, a person not only perceives and evaluates the situation, but also mentally constantly comments on what he thinks about, what he feels. Such comments Beck called "automatic thoughts" and believed that they can also be the source of our experiences and inappropriate behavior.

At the same time, a person not only perceives and evaluates the situation, but also mentally constantly comments on what he thinks about, what he feels. Such comments Beck called "automatic thoughts" and believed that they can also be the source of our experiences and inappropriate behavior.

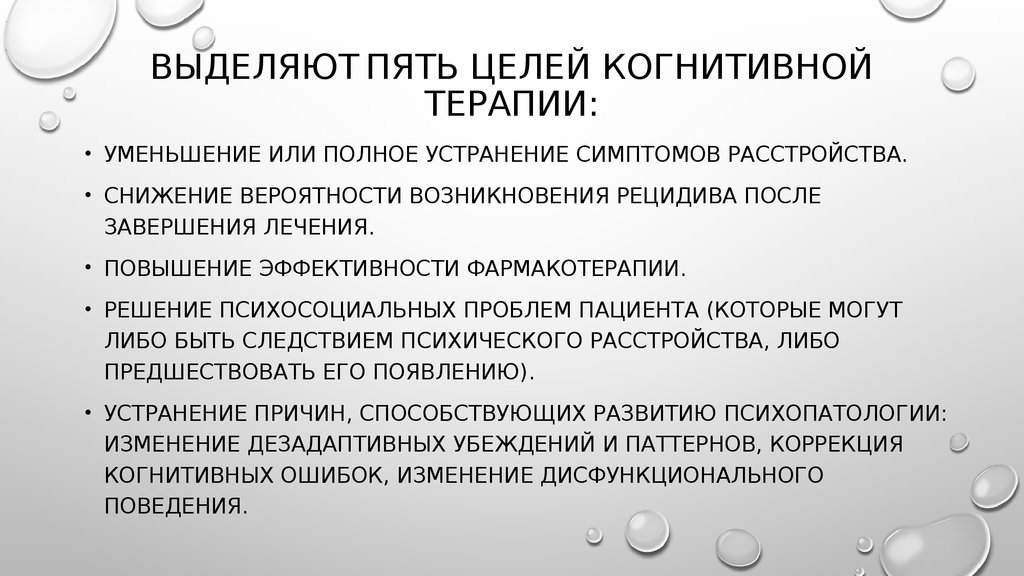

In a session of cognitive psychotherapy, the patient, together with the therapist, explores under what circumstances the problem manifests itself, how "automatic thoughts" arise and how they affect his ideas, experiences and behavior. He learns to soften his rigid beliefs, to see different facets of a problem situation. The goal of cognitive psychotherapy is to help a person get rid of the thought patterns that interfere with him (which are often formed in early childhood). The task of therapy is to teach a person to understand how he interprets the situation, what he notices and what he ignores, why such an assessment causes him certain feelings and actions.

Main representatives of the direction: Aaron Beck (Aaron Beck), Albert Ellis (Albert Ellis), George Kelly (George Kelly).

During the compilation of a vocabulary, data from the Big Psychological Dictionary edited by B. G. Meshcheryakov, V.P. Zinchenko

Collectivism> Popular terms 9000 thoughts out loud

To feel freer, to begin to perceive ourselves and the events of the world around us more openly, we need to understand what individual stereotypes of perception and thinking prevent us from doing this and get rid of them. Psychologist Natalya Garanyan talks about the method of cognitive psychotherapy.

Media news2

new on site

- How to stay in a state of psychological comfort at all times: 7 rules

- "Caught my husband cheating, now I can't trust him"

- If the heart demands love: how to break up with a married lover

- Psychic Clues: What Your Anger Says

- “I wrote a book and my friends turned their backs on me. Is it out of jealousy?

- "People always refer to me as 'you': how do I explain that this is a violation of my boundaries?"

- What Recurring Dreams Hidden

- How to let a child realize his talent without injuring him: the opinions of psychologists and the jury of the Blue Bird competition

Today they are reading

- “The ex-husband volunteered for a special operation, and I realized that I was not ready to lose him”

- “Expecting a child from an African.