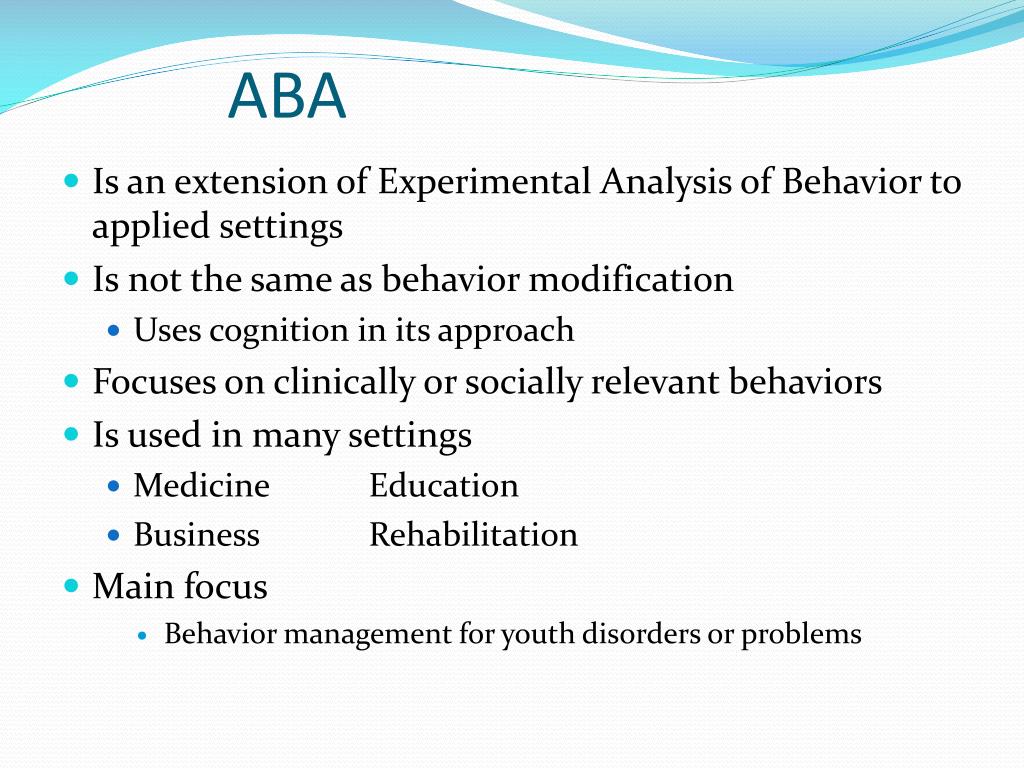

5 functions of behavior aba

Complete Guide – Master ABA

ABA uses the functions of behavior to understand behavior and why it occurs. When you accurately identify the function of a behavior, you answer the question: What does this person “get” out of engaging in this behavior. This answer allows you to select function-based interventions to address the behavior.

All behavior occurs because the individual gets something out of it. In Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA), the reason a behavior continues is called the function of that behavior. These functions are reinforcers for the child. If the behavior no longer works for that purpose, the behavior will stop and a new behavior will take its place.

In this article we will use examples related to challenging behavior; however, the information here can be applied to teaching new skills. Once the appropriate function of a child’s behavior has been identified, you can use this information to identify potential reinforcers for more appropriate behaviors.

The examples in this article are available in this free download for your reference:

Functions of BehaviorDownload

Contents

Functions of Behavior

Access and Escape in Action

How Many Functions Are There, Really?

Try it for Yourself

Related Posts

Functions of Behavior

Accurately identifying function allows you to make informed decisions to change behavior. Understanding why a behavior occurs leads to meaningful change. You can then use this information to alter the conditions surrounding the behavior.

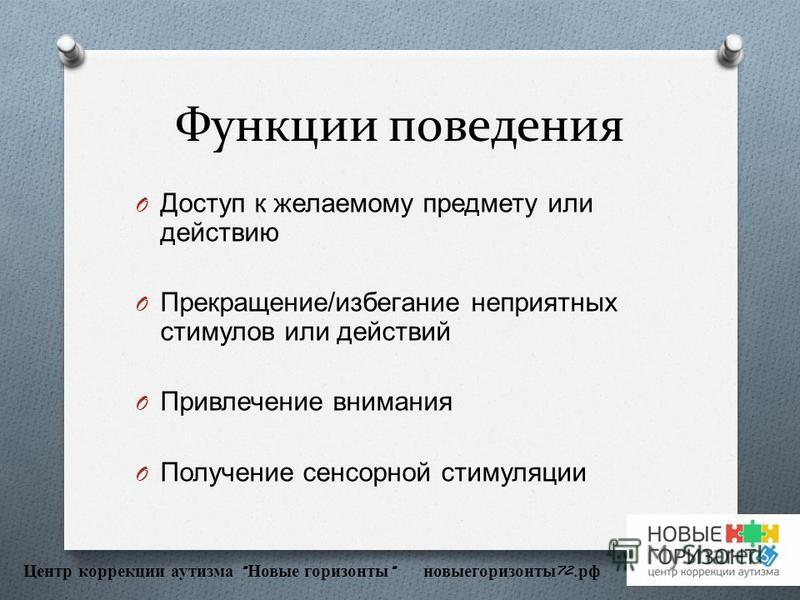

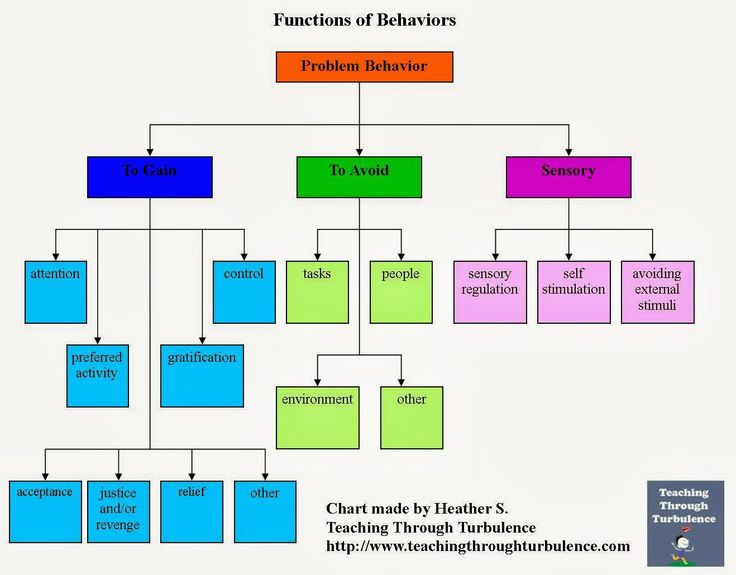

While there are many factors that motivate behavior, there are 2 primary functions of behavior that make a behavior more likely to happen in the future:

- Access

- Escape

Looking further at these primary functions, you can dig a little deeper to determine if the reinfocer is received directly or is socially mediated (provided by someone else). Knowing how the individual accesses the reinforcer assists you in determining how best to change the behavior.

Knowing how the individual accesses the reinforcer assists you in determining how best to change the behavior.

Start with this quick overview and see below for more detail:

Access Maintained Behaviors

Many behaviors occur because the individual gains access to something that is of value to them. The individual can gain access to a variety of different reinforcers including:

- Something tangible

- An activity

- A sensory experience

- Attention

Access to Tangibles

A tangible is something the person can touch or pick up. It could be anything from a toy to a piece of candy or even something that appears uninteresting to you. Young children with autism often develop intense interests in items that appear random such as flags, straws or pipes.

Access to Activities

Many children are motivated by activities that they find enjoyable. Does your client enjoy any of the following?

- Bubbles

- Tickles

- TV

- Music

Access to these activities may reinforce behavior. Other activities may also reinforce a behavior without you being aware of it.

Access to a Sensory Experience

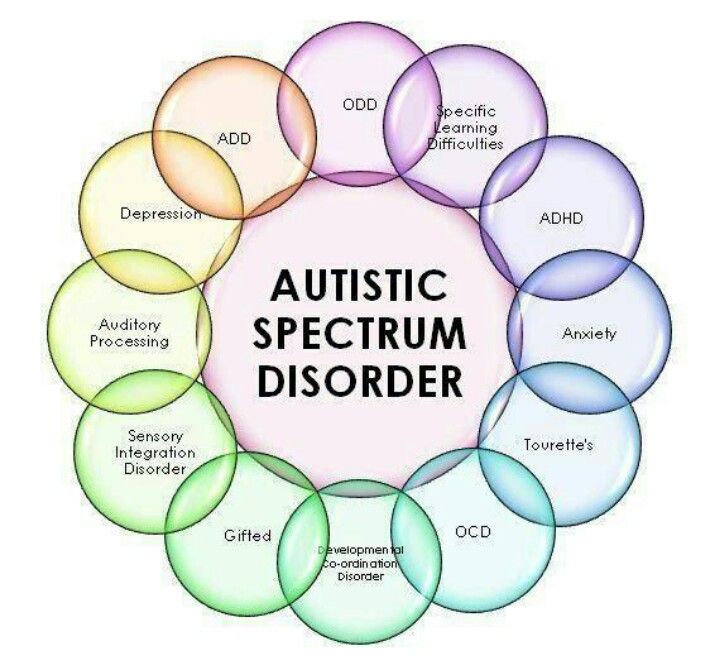

Another type of activity that your client might find reinforcing is stereotype. This might look like hand flapping, arm waving, hand tapping or finger wiggling. These types of behaviors, often referred to as “nonfunctional,” feel good to the individual. In this case, “nonfunctional” means that they don’t serve a useful purpose. Stereotypies are often considered in their own category of function of behavior called Automatic Reinforcement. For the purposes of this article, we will include them in the Access category and discuss their counterpart: escape from a sensory experience. Although some children with autism avoid extraneous sensory input, many seek sensory input from a variety of activities.

Access to Attention

Attention and social interactions reinforce many behaviors. Some children have positive reactions when an adult delivers praise or even provides a reprimand. Inappropriate behaviors can be unintentionally reinforced by attention such as reprimands if the learner is reinforced by access to attention.

Once you determine if a behavior is maintained by access, you can look deeper to determine how the individual is gaining access to the reinforcer. There are 2 ways that the individual gains access to the reinforcer:

- Direct access

- Socially mediated access

Direct Access

Many times individuals are able to directly access a reinforcer without the help of another individual. The child who takes a toy out of the hands of a peer has gotten direct access to the toy. The child who runs to the swing on the playground and swings on his belly has direct access to that activity. When a child spins in circles, she has access to that sensory experience.

While direct access is easy to understand, it may be difficult to prevent. A child who struggles with overeating but knows how to get into the refrigerator and cabinet can directly access food unless his parents find a way to block this behavior or teach an alternative.

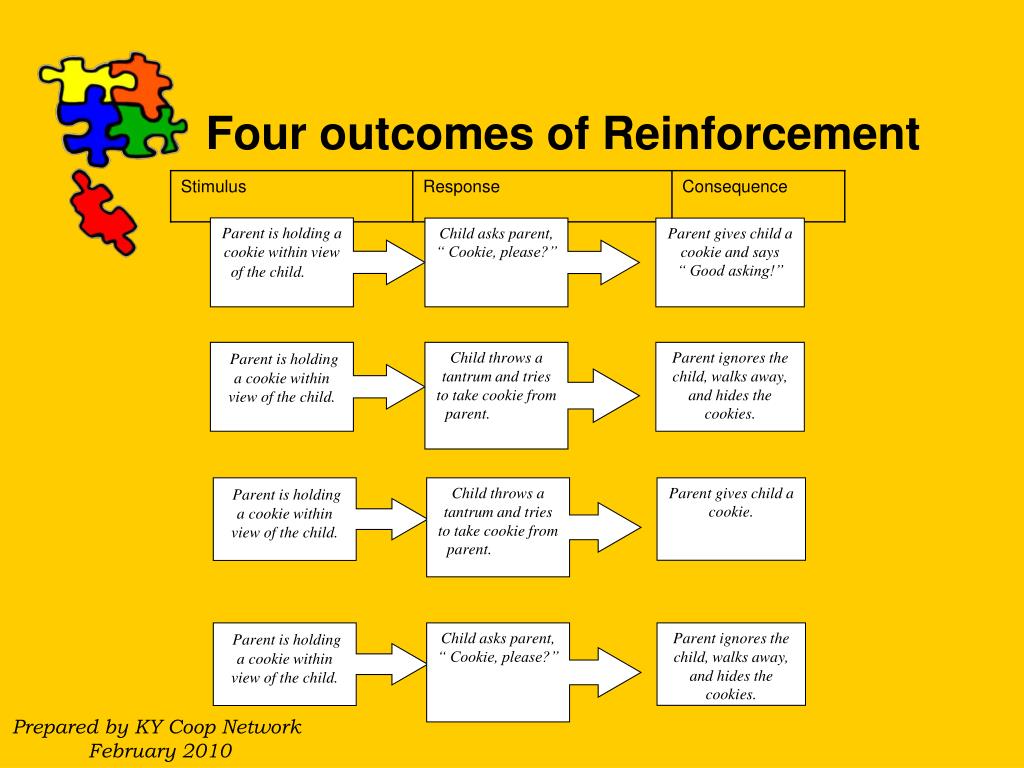

Socially mediated access requires a bit deeper look. This mode provides access to the reinforcer through another person. Whether that access is granted intentionally or inadvertently, the other person is necessary for the individual to gain access to the tangible, activity, sensory experience or attention. Why would anyone reinforce a challenging behavior by giving access to a reinforcer? Often the person mediating (providing) the access is not aware of the potential consequences. It may also be that the benefits for that person are greater than the perceived risk of granting access.

Often socially mediated access to a tangible reinforces challenging behavior because the adult didn’t anticipate a problem developing by allowing access to that tangible. Here’s an example:

Here’s an example:

Jim enjoys small fidget toys, especially ones that are squishy. Jim often struggles during group activities where there are no hands-on activities such as circle time or story time. The OT recommends watching his behavior and once he shows signs of distress (calling out, increased motor movement, crying), the teacher should give him a fidget toy to help him remain part of the group. Over time, Jim starts showing signs of distress earlier in circle and story time and he has begun to display these behaviors during other times as well.

In this example, the OT had good intentions. However, she did not consider the unintended effects of waiting for Jim to engage in problematic behavior before giving him access to the fidgets. Jim’s teacher was unaware that she inadvertently reinforced this behavior until it started to become a problem.

At times, nearly all parents have been guilty of “giving in” in order to make a behavior stop or to head off an impending explosion. When working with parents, it’s essential to remember that it’s unrealistic to expect that parents will never do this. Help parents identify the situations where they need to be consistent and where they might choose to “pick their battles” and let things slide a little.

When working with parents, it’s essential to remember that it’s unrealistic to expect that parents will never do this. Help parents identify the situations where they need to be consistent and where they might choose to “pick their battles” and let things slide a little.

Many of the activities listed above motivate both desired and undesired behaviors depending on the context within which the child has gained access to the activities in the past. In much the same way as socially mediated access to a tangible occurs without intentionally reinforcing maladaptive behavior, socially mediated access to activities develops along a similar path. Here’s an example:

Tara’s mother can always tell when she’s getting “amped up” because she starts yelling at her brother and taking toys away from him. In order to avoid a massive meltdown, Tara’s mother turns on the TV as soon as Tara starts these behaviors. Over time, Tara’s mother has noticed that Tara is becoming “amped up” more often and she’s not sure what to do about it.

While many sensory experiences don’t require another person in order to gain access, some do. Some children like deep pressure in the form of head squeezes, tight hugs or even tight fitting clothing. Other sensory experiences might include running fingernails along an arm or being spun on a swing. Take a look at this example:

Jennifer often has dramatic tantrums that include self-injurious behavior (SIB) and aggression. It’s difficult for her parents to identify what triggers these tantrums and they have become afraid of them as she has gotten bigger. They have found that providing deep pressure in the form of head and hand squeezes usually calms her. Each time she escalates, they begin to provide that pressure and they will often take turns when one gets tired.

Attention always requires social mediation, but it is a powerful reinforcer. Many parents, caregivers and professionals feel the need to “correct” challenging behavior. They may feel that the child won’t learn that the behavior is undesirable unless they tell the child every time it occurs. Often adults feel as though they are letting the child “get away with” the behavior by not doing something to address it.

Often adults feel as though they are letting the child “get away with” the behavior by not doing something to address it.

Many traditional parenting techniques require the parent to provide an extensive amount of attention contingent on problem behavior. Think about this example:

Jaime often throws toys when her parents ask her to clean up. Her parents have read many parenting books that recommend consistent consequences when challenging behaviors occur and they have decided to try “time out.” From what they read, Jaime should receive 1 minute of “time out” for each year of her age. Since she’s 5, she should be in “time out” for 5 minutes. They have chosen their “time out” spot, a hard chair in the corner of the living room.

The next time Jaime throws toys, her parents direct her to “time out.” She gets up repeatedly and her parents have to redirect her back to the chair. Finally, not knowing how else to keep her in “time out,” her mother sits in the time out chair with Jaime on her lap and holds her there for the full 5 minutes.

Escape Maintained Behaviors

Escape from something aversive can be a powerful motivator. Individuals will go to great lengths to escape or avoid things that are unpleasant such as:

- A relatively lengthy task

- A relatively difficult task

- Unpleasant sensory experience

- Attention or social interaction

Escape from a Relatively Lengthy Task

Some children find tasks that take a long time aversive. What constitutes a long time varies by the individual. One child might think that sitting at a table for 5 minutes is a long time. Another finds sitting for 30 seconds aversive. The aversiveness of the task is specific to the perspective of the individual. Even though you might feel as though it’s a quick task, the child might feel that it will take an unachievable amount of time.

Escape from a Relatively Difficult Task

For some children, it’s not how long the task will take but how difficult they expect the task to be. Again, this is specific to the child’s perception of the task, not how easy or difficult you think the task is for the child.

Again, this is specific to the child’s perception of the task, not how easy or difficult you think the task is for the child.

Escape from an Unpleasant Sensory Experience

While some children seek sensory experiences, many find specific sensations highly aversive. Unexpected loud noises, strobe lights, light touches or strong smells might appeal to one child and be aversive to another. A scent or sound you find pleasant might trigger a strong reaction from your client.

Attention and social interactions reinforce many behaviors; however, for some children, these are aversive experiences. Some children have strong negative reactions when an adult delivers praise or provides a reprimand. Others engage in behaviors to avoid social interactions because socializing with others is an unpleasant experience.

Modes of Escape

As with access maintained behaviors, escape maintained behaviors can be either:

- Direct escape

- Socially mediated escape

Direct Escape

As with direct access, direct escape is pretty straightforward. Direct escape involves the individual being able to escape without the help of another person. A child who walks away from the dinner table escapes having to sit at the table for the whole duration of mealtime. The child who rips up her math homework escapes completing this difficult task. When a child covers his ears when the hand dryer starts in the public restroom, he directly escapes the sound of the dryer. Hiding under a blanket when someone walks into the room effectively escapes that social interaction.

Direct escape involves the individual being able to escape without the help of another person. A child who walks away from the dinner table escapes having to sit at the table for the whole duration of mealtime. The child who rips up her math homework escapes completing this difficult task. When a child covers his ears when the hand dryer starts in the public restroom, he directly escapes the sound of the dryer. Hiding under a blanket when someone walks into the room effectively escapes that social interaction.

Socially mediated escape maintained behaviors are a bit more complex than direct escape maintained behaviors because they require the assistance of another person. As with socially mediated access maintained behaviors, undesired behaviors are often inadvertently reinforced by the adult for a variety of reasons.

When an adult presents a lengthy task and subsequently allows the child to complete only a portion of the task or even escape the task altogether in response to the child’s objections, the child’s behavior is reinforced. Take a look at this example:

Take a look at this example:

Kevin has been playing in his room for the last hour and has strewn trains, cars and blocks all over his room. Kevin’s mother comes in and tells him to clean up. Kevin begins to kick his legs, cry and throw toys. Kevin’s mother knows that the mess might seem overwhelming to him so she begins to help him clean up. When there are only a few blocks left to pick up, she has him complete the task. Kevin has successfully used his behavior to reduce the length this task will take. Understanding this contingency, you can begin to teach Kevin to use language (functional communication training) to reduce the length of the task. Teach Kevin to say “can you help me clean up?” rather than using maladaptive behavior.

Socially mediated escape from a relatively difficult task is similar to the above condition except another person is required to reduce the difficulty of the task or to escape the task altogether. Everyone likes to feel successful and when faced with a task that appears too difficult, challenging behavior can emerge. Consider this example:

Consider this example:

Katie hates doing homework, especially reading because she has a hard time sounding out the words in new books. Her father does homework with her every night. Katie screams and cries through the process and repeatedly says she can’t do it. Usually the book ends up on the floor. Her father feels bad that she’s struggling and speaks to her teacher about reducing her homework. The teacher says that for homework Katie can read familiar books rather than the new ones she has been sending home with her. Katie’s father has helped her escape the task of reading new books for homework. Katie will be more likely to engage in these behaviors in the future when she is faced with difficult tasks.

Many children will engage in serious maladaptive behavior in order to escape from an unpleasant sensory experience. Especially for young children, this behavior often requires the help of another person making this a socially mediated escape maintained behavior. Look at the following example:

The automatic hand dryers in public restrooms are extremely aversive to Juan. Each time his mother takes him into a public restroom and sees one of these hand dryers, Juan begins to scream and hit his mother’s arm. His mother immediately takes him out of the restroom and avoids restrooms with automatic hand dryers in the future. Juan’s mother didn’t intentionally reinforce his screaming and aggression; however, Juan will likely engage in these behaviors if she takes him into a restroom with these hand dryers in the future. This is another great opportunity for functional communication training to teach Juan to escape the unpleasant sensory experience using more adaptive behavior.

Each time his mother takes him into a public restroom and sees one of these hand dryers, Juan begins to scream and hit his mother’s arm. His mother immediately takes him out of the restroom and avoids restrooms with automatic hand dryers in the future. Juan’s mother didn’t intentionally reinforce his screaming and aggression; however, Juan will likely engage in these behaviors if she takes him into a restroom with these hand dryers in the future. This is another great opportunity for functional communication training to teach Juan to escape the unpleasant sensory experience using more adaptive behavior.

Just as some attention and social interactions are reinforcing for some children, the same attention or social interactions may be aversive for others. When an adult helps the child escape from these situations, the child’s behavior is potentially reinforced. For example:

Sam loves to play at the playground; however, she does not enjoy other children playing with her. Sam’s mother sits near her and watches as she plays in the sandbox digging holes. When another child approaches and tries to play with Sam, Sam begins to scream and throw sand. Sam’s mother tells the other child that Sam has autism and would rather play alone. When the other child leaves, Sam’s behavior may be reinforced.

When another child approaches and tries to play with Sam, Sam begins to scream and throw sand. Sam’s mother tells the other child that Sam has autism and would rather play alone. When the other child leaves, Sam’s behavior may be reinforced.

Back to Top

Access and Escape in Action

To see some of the functions of behavior in action watch Functions of Behaviour by Tara Rodas:

Back to Top

How Many Functions Are There, Really?

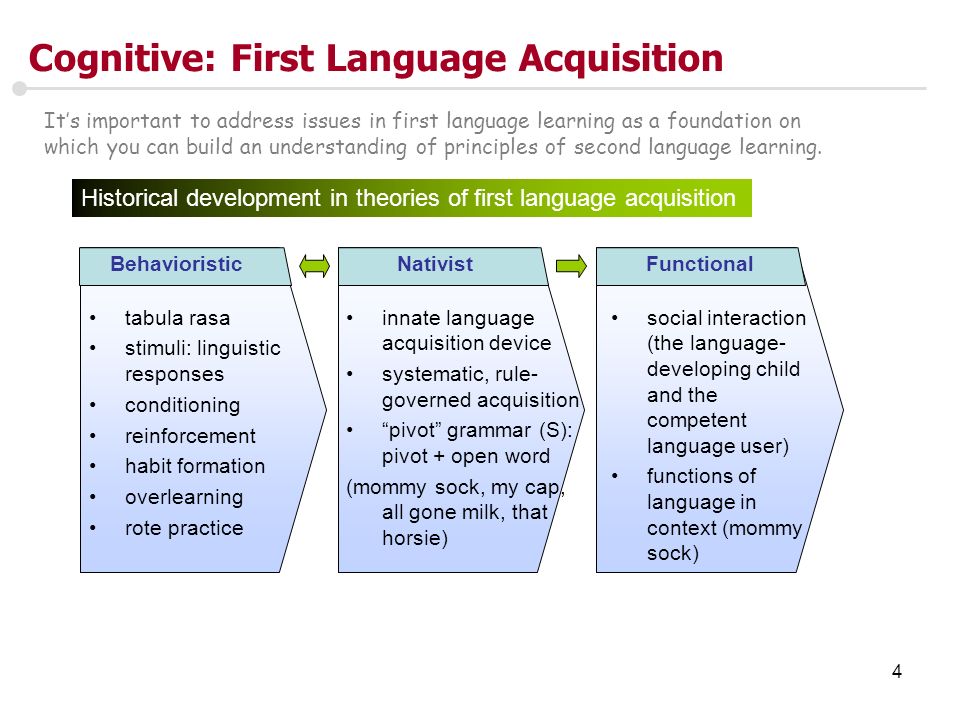

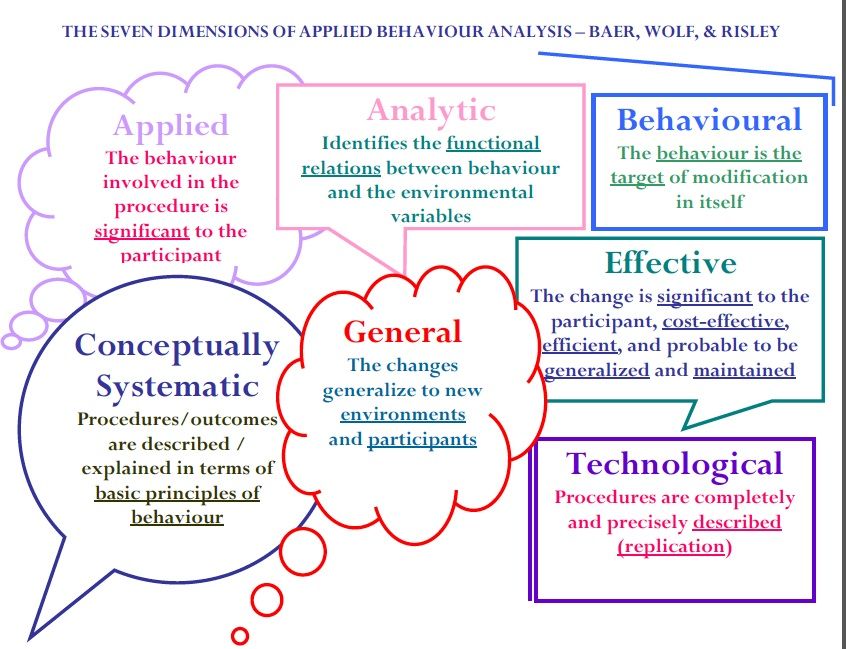

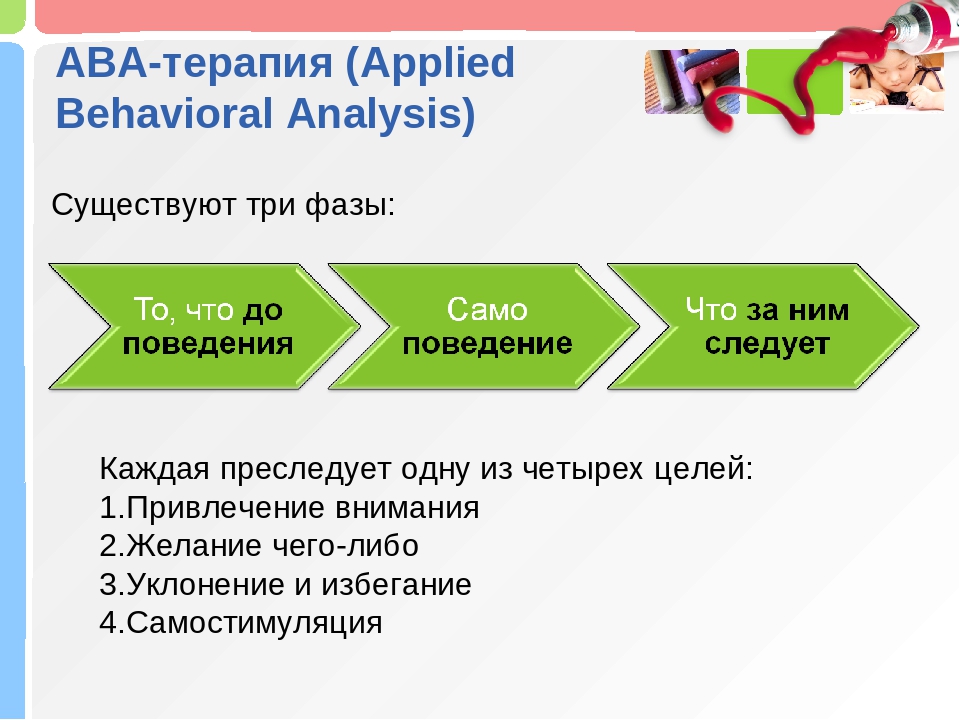

Traditional sources say there are 3-4 functions of behavior (access, escape, attention and automatic), however there is a better way to conceptualize the functions of behavior. Cipani and Schock (2010) created a behavioral diagnostic system that expands on traditional models to help us understand behavior on a deeper level. They describe 2 primary functions: access and escape then go on to identify the type of reinforcer and the mode of access (direct or socially-mediated). This method provides a comprehensive approach to understanding the functions of behavior.

They describe 2 primary functions: access and escape then go on to identify the type of reinforcer and the mode of access (direct or socially-mediated). This method provides a comprehensive approach to understanding the functions of behavior.

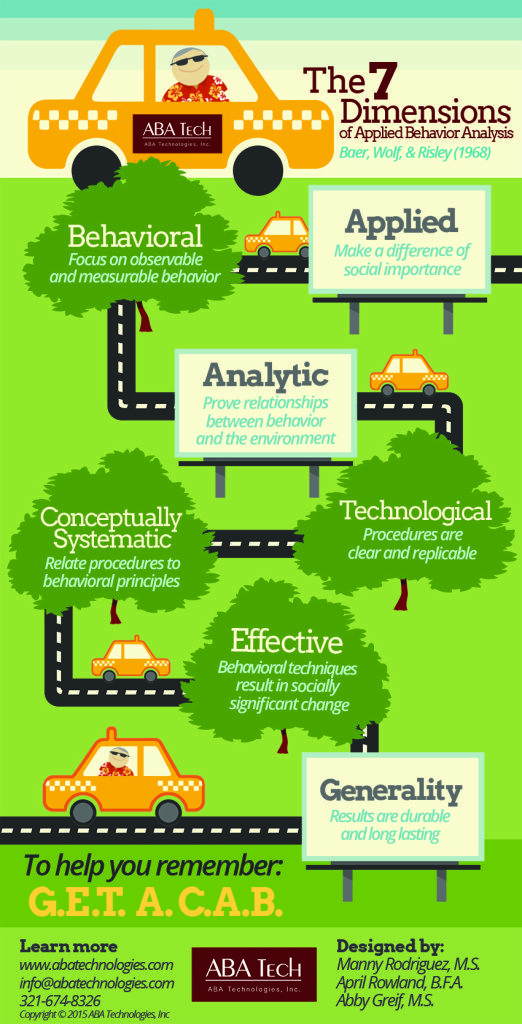

Depending on your source, the functions are presented in different ways which can make understanding this concept confusing for students new to the field. Many traditional resources as well as current ones, reference 3-4 functions of behavior: Access, Escape, [Attention] and Automatic. Some resources group attention with access, others present it as a separate behavioral function. Tools, including questionnaires like the Question About Behavioral Function (QABF) and the Functional Assessment Screening Tool (FAST) also provide different behavioral categories. Here we will compare just 3 common models of describing behavioral funciton.

Classic Functions of Behavior

Jamison et al. (2016) present this limited view of function in their presentation ABA in 2016. They describe the 4 primary functions of behavior as access, attention, escape and automatic reinforcement. In this model, behaviors that receive positive reinforcement in the form of an activity or something tangible fall in the access category. The attention category covers behaviors maintained by positive reinforcement in the form of attention. Escape includes behaviors that are negatively reinforced through escaping or avoiding an aversive stimulus. Automatic describes behaviors maintained by a pleasant sensory experience.

They describe the 4 primary functions of behavior as access, attention, escape and automatic reinforcement. In this model, behaviors that receive positive reinforcement in the form of an activity or something tangible fall in the access category. The attention category covers behaviors maintained by positive reinforcement in the form of attention. Escape includes behaviors that are negatively reinforced through escaping or avoiding an aversive stimulus. Automatic describes behaviors maintained by a pleasant sensory experience.

Three of these categories cover positive reinforcement, leaving one to describe negative reinforcement. A benefit to this perspective is the simplicity, but the categories of access, attention and automatic are somewhat redundant and unclear. Instructors in many ABA courses present this model when teaching about the functions of behavior. Students of these instructors may feel confused when they encounter alternative conceptualization of this critical concept.

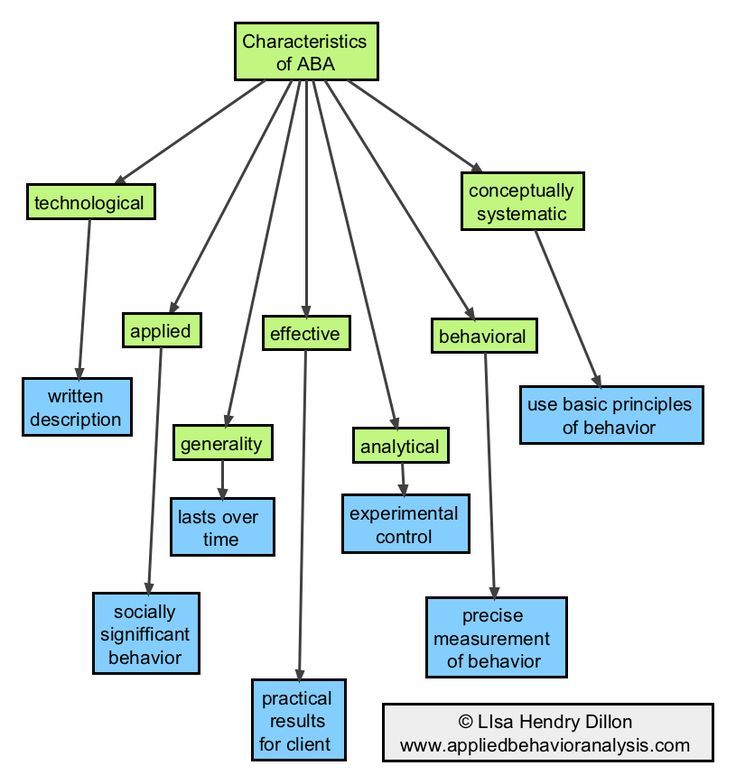

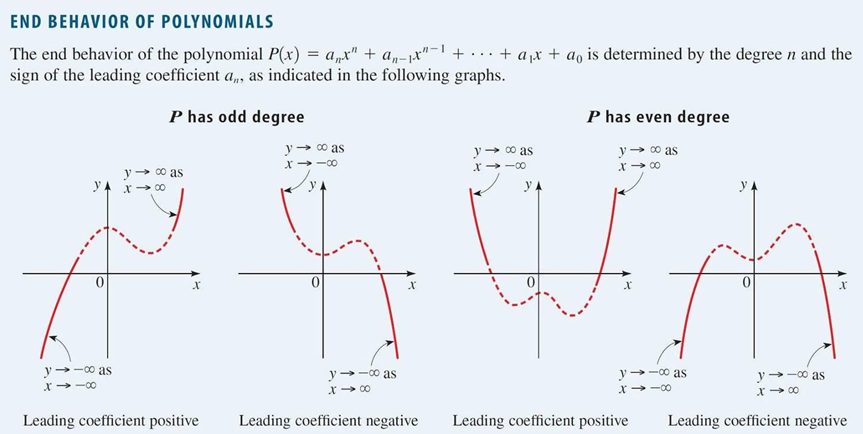

The image below shows the extent to which this model describes behavioral function. The analyst may include more narrative information to further clarify maintaining variables, but the categories themselves fail to provide much description.

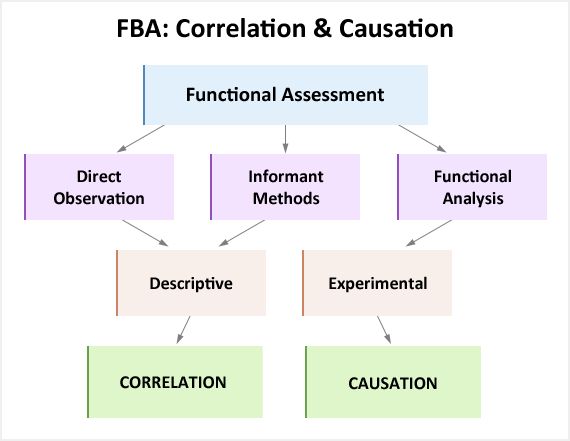

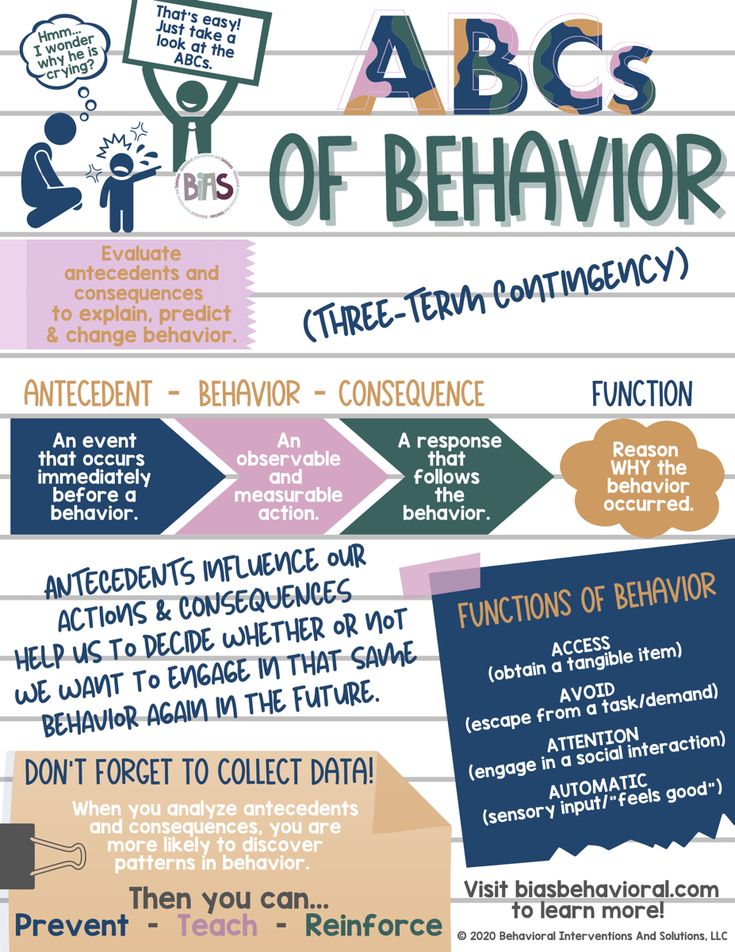

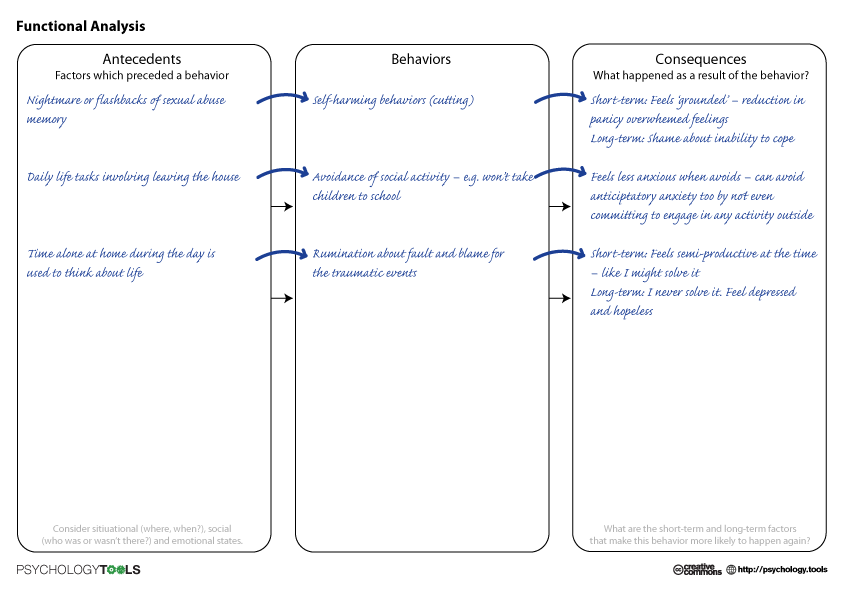

To identify the function of a particular behavior, professionals conduct a functional analysis or functional behavior assessment. This involves either manipulating variables surrounding the behavior of interest or collecting data when the behavior occurs in a more natural setting. The analysts consider what reinforcer occurs as a result of that behavior (or at least within a temporal relation to that behavior).

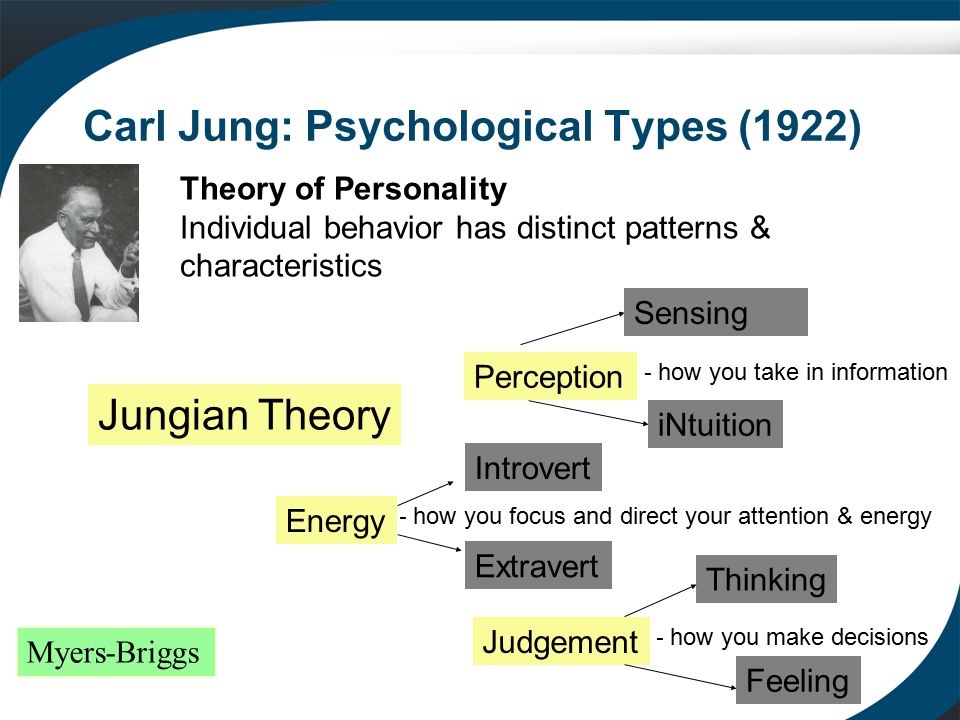

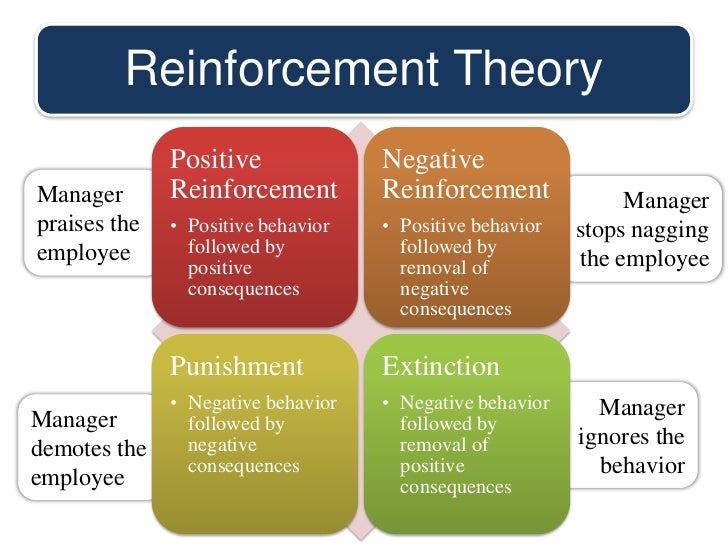

In their book Applied Behavior Analysis, which is often referred to as the ABA bible, Cooper, Heron and Heward (1987, p. 501-502) describe 2 primary categories of behavioral function with subcategories for each: Positive Reinforcement and Negative Reinforcement. Remember that reinforcement is a stimulus that follows behavior AND strengthens that behavior along some measure (i. e. frequency, intensity, duration, etc.). Positive reinforcement refers to the addition of a stimulus and negative reinforcement refers to the removal of a stimulus.

e. frequency, intensity, duration, etc.). Positive reinforcement refers to the addition of a stimulus and negative reinforcement refers to the removal of a stimulus.

This view of behavioral function is more detailed than the one described above and starts to dig more specifically into what stimulus is added (positive) or removed (negative) to strengthen the behavior (reinforcement). The subcategories included by the authors are represented in the image below. These subcategories provide more information about the maintaining variables which leads to more accuracy when selecting function-based interventions.

Diagnosis of Function

Cipani and Schock (2010) use a slightly different model when describing behavioral function. Their comprehensive approach avoids redundancy while thoroughly capturing all possibilities. This system specifies not only positive reinforcement (access) or negative reinforcement (escape) but also the type of reinforcer and whether another person provides access to the reinforcer (direct or socially-mediated). The authors include additional descriptive language when appropriate such as describing whether attention from peers or adults maintains the behavior.

The authors include additional descriptive language when appropriate such as describing whether attention from peers or adults maintains the behavior.

Understanding behavior at this level helps you develop a plan that effectively addresses that behavior. Grey and Hastings (2005) emphasized the use of function in selecting evidenced-based interventions. Functional behavioral assessment and functional analysis allow the analyst to identify or hypothesize the function of challenging behavior. Once you collect data to determine controlling variables, use this diagnostic tool to describe those variables in detail.

First, identify if the reinforcer is positive or negative. Then, determine what type of reinforcer controls the behavior. Finally, determine if access to that reinforcer requires the presence of another person. Although this model requires 3 steps, it becomes fluid with some practice.

Look at this example:

Your client engages in aggression when asked to perform a task he doesn’t want to do. After looking at descriptive analysis data and observing the behavior yourself, you see that his aggression results in a delay of the task and staff altering how long they expect him to perform the task.

After looking at descriptive analysis data and observing the behavior yourself, you see that his aggression results in a delay of the task and staff altering how long they expect him to perform the task.

Without conducting a full analysis of the behavior, you can only hypothesize the function. In this example, the behavior is maintained by both the direct escape (delay of onset of the task) and socially-mediated escape (staff shortening the task) of a relatively lengthy task. The task might not actually take a long time to complete, but consider the task from his perspective.

This quick example highlights the benefit of describing function in this way. Now you understand more specifically what aspect of the task he finds aversive. Teaching him to request a delay in starting the task or a shorter task or a even break during the task provides an alternative that addresses the details of what maintains the challenging behavior.

Comparing the 3 Models

While the model you choose may impact your ability to choose effective, function-based interventions, they aren’t necessarily mutually exclusive. You may choose to use Cipani and Schock’s model when selecting interventions, but a simpler one when speaking with or training parents or caregivers.

You may choose to use Cipani and Schock’s model when selecting interventions, but a simpler one when speaking with or training parents or caregivers.

Look at the following example and how each model describes the function of the behavior:

You conduct a functional behavior assessment and determine that your client’s spitting most often results in attention from both his peers and classroom teacher.

The first model described above would put this behavior in the attention category. The second model puts this behavior in the social positive reinforcement category. The third model describes this behavior as maintained by socially-mediated access to attention from both adults and peers. Sure, the information is reasonably similar, but the third example provides a bit more detail that assists you in your search for effective interventions.

Choose the model of functions of behavior that makes the most sense to you and meets the needs of your specific situation. Each model presents unique advantages, but your audience’s understanding of the model might be the most important consideration. Although you use this information to select appropriate function-based interventions, other people likely need to understand your analysis. Parents, RBTs, and payers each read and process your documentation for different purposes. Avoid using language from one of the models that will confuse your intended audience, if possible.

Each model presents unique advantages, but your audience’s understanding of the model might be the most important consideration. Although you use this information to select appropriate function-based interventions, other people likely need to understand your analysis. Parents, RBTs, and payers each read and process your documentation for different purposes. Avoid using language from one of the models that will confuse your intended audience, if possible.

Back to Top

Determining the Function of a Behavior

How do you know what the function of an individual’s behavior is? Unfortunately we can’t just ask them because even if they could tell us, they’re likely not aware of it themselves. Consider your own behavior for a minute:

Most people could probably tell you why they go to work: to get a paycheck, right? So the function of the behavior “going to work” would be pretty obvious.

But let’s dig a little deeper. What if you consistently work hard to go above and beyond what’s expected of you at work? What might the function of this behavior be? There are actually several possibilities. You might get:

You might get:

- Satisfaction from the work you’re doing

- Praise from your boss, parents, coworkers, teachers, clients, etc.

- Compensated for doing your job well (i.e. a raise, bonus or commissions)

Unless you stop to think about this, you might not even realize what you’re doing, or why you’re doing it.

Your learners likely don’t know why they do what they do, so how can you figure it out?

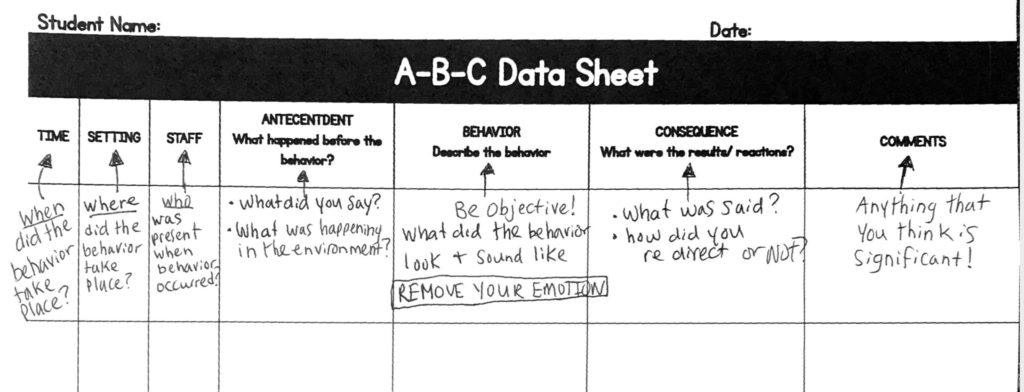

ABC Data

ABA relies heavily on ABC data to understand the context of a behavior. Our post ABC Data: The Key to Understanding Behavior goes into detail about what ABC data is and how to collect it…but then what?

Well, that depends on whether the ABC data alone provides a clear function of the behavior. Let’s look at an example.

On an ABC data sheet the data looks like this:

- In the antecedent column, you write what happened just before the behavior, Debra said it was time for school.

- In the behavior column, you write Jake yelled no and threw his toy toward Debra.

- And in the consequence column you write what happened right after the behavior, Debra gasped and Jake delayed going to school.

There might be other antecedents and consequences that also influence the behavior that you might make note of. Maybe Debra forgot to bring Jake’s lunchbox into the room or it’s already in his backpack and he doesn’t know it. Maybe the airplane made a cool noise when it hit the floor.

Which factors might be impacting his behavior? With this data, you can ask yourself, “what is he telling me with his behavior?” What is he accessing or avoiding with the behavior? He gets a small reaction from Debra and he delays going to school. Maybe he’s saying, “I don’t want to stop playing. I would rather stay with you.”

While this example seems pretty clear, often the data is more complex, and a series of challenges may build on each other.

Let’s take this example a little further. The consequence for the first behavior might become the antecedent for the next behavior.

Jake might be upset that his routine was disrupted by missing the bus and that could trigger another behavior.

Here we write down what behavior Jake engages in, he cries, stomps his feet and then pushes Debra. The consequence of this behavior is Debra says, “we have to go now. I’m going to be late for work.” This consequence becomes the antecedent for the next behavior which is Jake hitting Debra and then running to his room. The consequence to this behavior is that Debra follows him and offers to stop to get a doughnut on the way to school.

We can see through this example that Jake’s behavior escalated pretty quickly and Debra was doing whatever she could just to get him out the door. What is Jake saying with his behavior? How about, “I don’t know how to handle sudden changes in my routine and I want you to help me.” He also gets a doughnut out of the deal.

The data sheet might look like this:

While all this is important information, you may find that ABC data alone isn’t enough to determine the function, and you need to collect other types of data such as questionnaires and scatterplot data.

Questionnaires

There are several questionnaires available to help determine the function of a behavior: Motivational Assessment Scale (MAS) and Questions about Behavioral Function (QAFB). In Assessment of the convergent validity of the Questions About Behavioral Function scale with analogue functional analysis and the Motivation Assessment ScaleT. R. Paclawskyj,, J. L. Matson,, K. S. Rush,, Y. Smalls, T. R. Vollmer (2008) determined that these two questionnaires provide similar results.

As an alternative, we have created interactive “quiz” to help determine the function of a behavior.

Scatterplot Data

Scatterplot data can also provide insight into the time of day, or day of the week behaviors are more likely to happen. Using a grid to map out the time of day and the day of the week, simply record the number of instances of a behavior in the allotted time.

Download a blank template now!

ScatterplotDownload

Analyzing the Data

Once you have all the data assembled, you need to understand what it all means. If you’ve collected the data in a tool, either through your employer, or one you’ve purchased like our AID Document Creation Tool (an add on to the ABLE Support for BCBAs , the program can likely do a lot of the analysis for you. AID, for example, takes the data and creates graphs that make it easy for you to find patterns in the data.

If you’ve collected the data in a tool, either through your employer, or one you’ve purchased like our AID Document Creation Tool (an add on to the ABLE Support for BCBAs , the program can likely do a lot of the analysis for you. AID, for example, takes the data and creates graphs that make it easy for you to find patterns in the data.

For a less technical approach, you can use something like the Data Triangulation Chart pictured here to collect your findings. While this document has a fancy title, it’s simply a form where you can make notes about the most common antecedents and consequences from each source of data. Download a blank template here:

Data Triangulation ChartDownload

Let AID Document Creation Tools Do It for You!

AID Document Creation Tools is an add on feature of our ABLE Support for BCBAs membership. With AID you will be able to collect data directly in the program from any computer, tablet or smart phone. The tool will then generate graphs to make it easy for you to analyze the data and identify the best interventions for your clients.

Cipani, E., & Schock, K. M. (2010). Functional behavioral assessment, diagnosis, and treatment: A complete system for education and mental health settings. Springer Publishing Company.

Cooper, J. O., Heron, T. E., & Heward, W. L. (1987). Applied behavior analysis. Merrill Publishing Co.

Grey, I. M., & Hastings, R. P. (2005). Evidence-based practices in intellectual disability and behaviour disorders. Current opinion in psychiatry, 18(5), 469-475.

Jamison, W. J., Hard, A., B. A.,Tara, Allen, C., Clark, J. & Hagy, S. (2016). ABA in 2016. [PowerPoint slides].

Paclawskyj, Theodosia Renata, “Questions About Behavioral Function (QABF): A Behavioral Checklist for Functional Assessment of

Aberrant Behavior.” (1998). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 6855. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/6855

T. R. Paclawskyj,, J. L. Matson,, K. S. Rush,, Y. Smalls, T. R. Vollmer. (2008). Assessment of the convergent validity of the Questions About Behavioral Function scale with analogue functional analysis and the Motivation Assessment Scale. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00364.x

Journal of Intellectual Disability Research. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2788.2001.00364.x

Functions of Behavior

Functions of Behavior

"The function of a behavior refers to the source of environmental reinforcement for it." - Tarbox et al (2009, p. 494)

Four Common Functions of Behavior

Before getting more technical about the functions of behaviour we’re going to outline four common behavioural functions below.

#1 Social Attention

A person may engage in a certain behaviour to gain some form of social attention or a reaction from other people. For example, a child might engage in a behaviour to get other people to look at them, laugh at them, play with them, hug them or scold them.

While it might seem strange that a person would engage in a behaviour to deliberately have someone scold them it can occur because for some people it’s better to obtain “bad” attention than no attention at all (Cooper, Heron & Heward, 2007).

#2 Tangibles or Activities

Some behaviours occur so the person can obtain a tangible item or gain access to a desired activity. For example, someone might scream and shout until their parents buy them a new toy (tangible item) or bring them to the zoo (activity).

#3 Escape or Avoidance

Not all behaviours occur so the person can “obtain” something; many behaviours occur because the person wants to get away from something or avoid something altogether (Miltenberger, 2008).

For example, a child might engage in aggressive behaviour so his teachers stop running academic tasks with him or another child might engage in self-injury to avoid having to go outside to play with classmates.

#4 Sensory Stimulation

The function of some behaviours do not rely on anything external to the person and instead are internally pleasing in some way – they are “self-stimulating” (O’Neill, Horner, Albin, Sprague, Storey, & Newton, 1997). They function only to give the person some form of internal sensation that is pleasing or to remove an internal sensation that is displeasing (e. g. pain).

g. pain).

For example, a child might rock back and forth because it is enjoyable for them while another child might rub their knee to sooth the pain after accidentally banging it off the corner of a table. In both cases, these children do not engage in either behaviour to obtain any attention, any tangible items or to escape any demands placed on them.

Behaviours Occur for a Reason

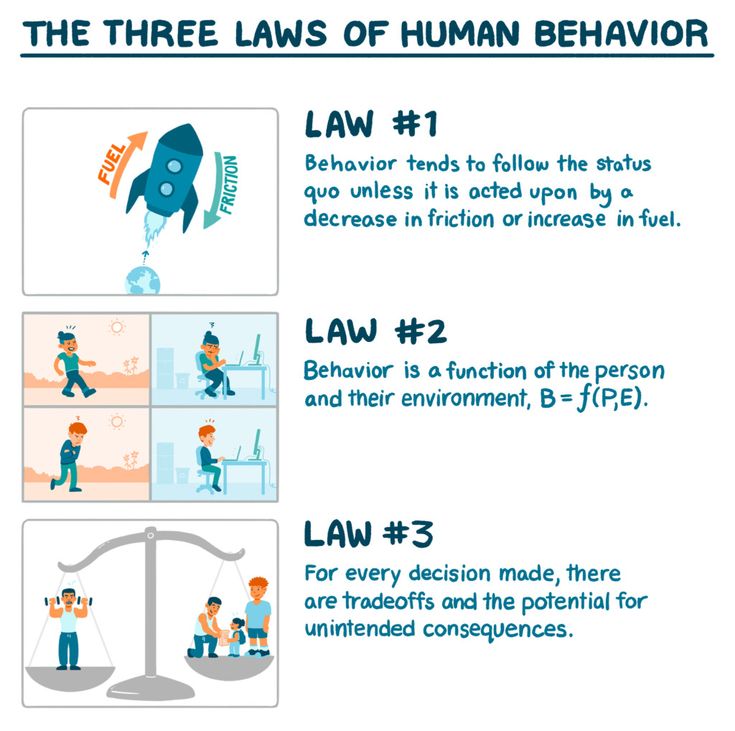

A behaviour that a person engages in repeatedly will typically serve some kind of purpose or function for them (O’Neill, et al, 1997). Note the word “repeatedly” is used because people engage in all kinds of behaviours but unless a behaviour serves some kind of function for them it wouldn’t typically continue to occur.

When we say the “function” of a behaviour we basically mean “why” the behaviour is occurring. While it might be difficult to understand why a person does something (e.g. challenging behaviours such as self-injury or aggression) there will always be an underlying function (O’Neill, et al, 1997).

It’s worth noting that a behaviour can serve more than one function (Miltenberger, 2008). For example, a child might learn to hurt themselves during class to get out of having to complete academic tasks and then also hurt themselves in the playground to get attention from the teachers. Here the same behaviour – self-injury – serves two different functions depending on the environment the child is in.

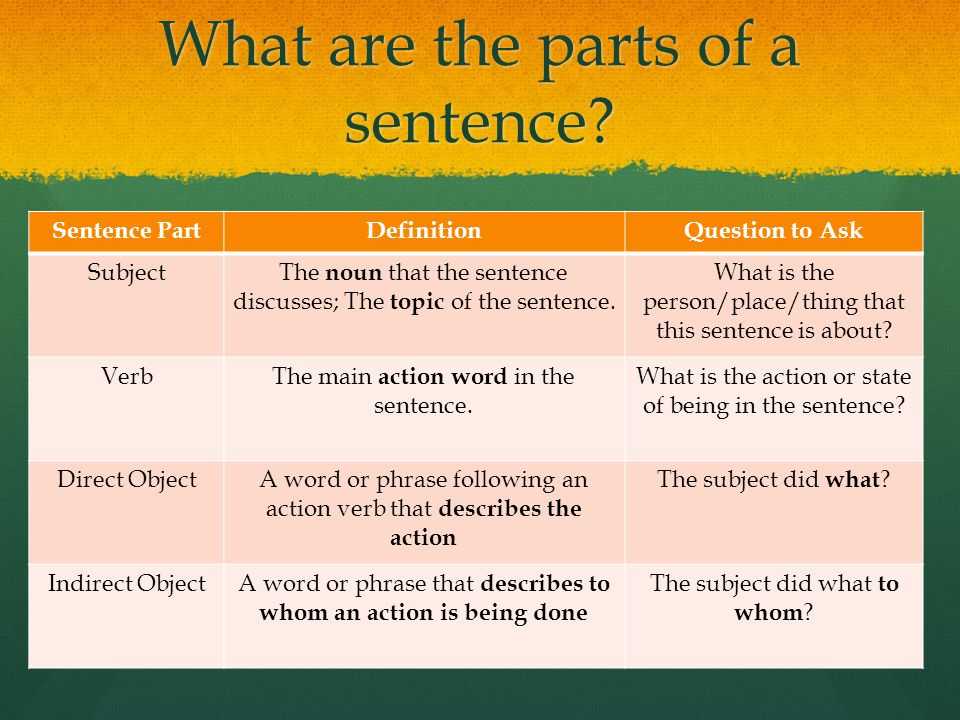

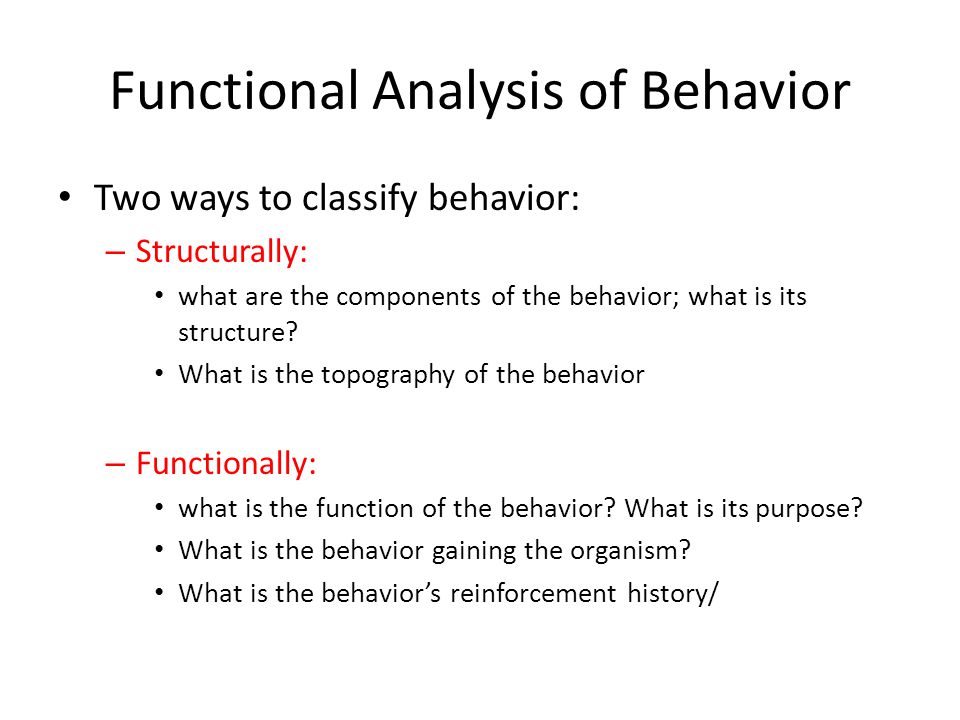

Function (Why) vs. Topography (What)

If a child hurts themselves and we describe that behaviour as “self-injury” then we are describing the topography of the behaviour. Topography only describes “what” behaviour is occurring but it says nothing about “why” the behaviour occurs; this is where the function of the behaviour is needed because the function will describe “why” it is occurring (Cooper et al, 2007).

Another example would be if we said the person is “talking”. To say someone is talking is describing the topography of the behaviour but tells us nothing about the function. Someone might talk to another person to ask for directions, another person might talk to teach a class of students while another person might talk to chat up someone they want to date.

Someone might talk to another person to ask for directions, another person might talk to teach a class of students while another person might talk to chat up someone they want to date.

While a clear definition of the behaviour’s topography is needed, it is important to identify and describe the function of the behaviour through a Functional Behaviour Assessment (FBA). Without understanding the function of a behaviour any intervention put in place could be ineffective and/or make the behaviour worse (O’Neill et al, 1997).

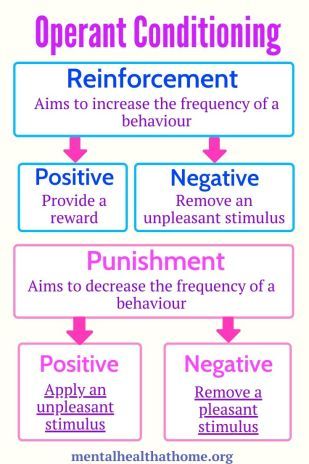

Function and Reinforcement

The reason for a behaviour occurring can be described in terms of the function it serves or the reinforcement that is maintaining it (Miltenberger, 2008).

When we say the “reinforcement that is maintaining it”, this just means we can describe the reason the behaviour occurs in terms of the favourable outcome that the behaviour creates for the person (Miltenberger, 2008).

It doesn’t really matter whether you choose to describe the function of the behaviour or the reinforcement maintaining the behaviour because either way you are saying the same thing but just using different terminology.

That said, it can useful to use both terms when describing the function of a behaviour. For example, you could say: “the behaviour is being maintained by positive reinforcement; he is hitting his peers in the playground and the function of this behaviour is to obtain access to the swing set during lunch break”.

Two Broad Behavioural Functions

Broadly speaking, behaviours serve two functions; they either get a person something or get a person out of or away from something (Cooper et al, 2007).

When a behaviour gets a person something this is called positive reinforcement and when a behaviour gets a person away from something or results in an item being taken away from them this is called negative reinforcement.

Initial breakdown of reinforcement into positive and negative forms.To say a behaviour occurs because it either gets a person something or gets the person away from something isn’t really telling you all that much.

To get a clearer and more descriptive understanding of behavioural functions we need to be much more specific. To do this, we need to break down both positive and negative reinforcement into two more specific classes.

To do this, we need to break down both positive and negative reinforcement into two more specific classes.

Social and Automatic Reinforcement

Positive reinforcement can be broken down into “social” and “automatic” positive reinforcement, while negative reinforcement can be similarly broken down into “social” and “automatic” negative reinforcement.

Breaking down positive and negative reinforcement into their respective social and automatic forms.Social Positive Reinforcement

The first specific class of reinforcement is called “social positive reinforcement” and occurs when a behaviour gets a person something through the action of another person. Three examples of social positive reinforcement include:

Example One: A boy asking his mother for a glass of milk and then getting the milk from his mother. Here the boy’s behaviour of asking for milk required another person (his mother) to mediate his ability to obtain the glass of milk.

Examples Two: A comedian telling jokes and making people laugh. Here the comedian’s behaviour of telling jokes occurred in order to create a favourable outcome for him (people laughing) and this behaviour required other people.

Examples Three: A child asking their parents if they can go to the zoo at the weekend and then being told she can go. Similar to the boy asking for a glass of milk, here the girl wants access to an activity and the behaviour of requesting to go to the zoo requires another person/s for reinforcement to occur.

Automatic Positive Reinforcement

The second specific class of reinforcement is called “automatic positive reinforcement” and occurs when a behaviour gets a person something as a result of their own actions i.e. no-one else was involved in any way. Three examples of automatic positive reinforcement include:

Example One: A boy pouring his own glass of milk. Here his behaviour produced its own reinforcement by the fact that he got what he wanted and no-one else was in any way needed for reinforcement to occur.

Example Two: A child hand-flapping for personal enjoyment (self-stimulation). It’s important to note that just because a person engages in hand-flapping does not mean the behaviour is maintained by automatic reinforcement; this is why we specify that the hand-flapping occurs for personal enjoyment. Some people could engage in hand-flapping for various different reasons (e.g. to obtain attention).

Example Three: A child turning on a computer to play a game. Here the child’s behaviour of turning on the computer gets them access to the computer game and no-one else was needed.

Social Negative Reinforcement

The third specific class of reinforcement is called “social negative reinforcement” and this occurs when a behaviour gets a person away from something or gets something taken away from the person through the actions of another person. Three examples of social negative reinforcement include:

Example One: A boy asking his mother to take the vegetables off his dinner plate and his mother then taking them off the plate. Here the boy’s behaviour required another person (his mother) to mediate his ability to get rid of the vegetables.

Here the boy’s behaviour required another person (his mother) to mediate his ability to get rid of the vegetables.

Example Two: If you crossed the road to avoid talking to someone you don’t like. Here your behaviour is occurring to avoid an aversive situation that involves another person.

Example Three: A child at the playground screams at her Dad that she wants to leave and her father dutifully takes her away. Here the girl’s behaviour is occurring to avoid being at the playground but she needed another person (her father) to mediate the outcome.

Automatic Negative Reinforcement

The fourth specific class of reinforcement is called “automatic negative reinforcement” and this occurs when a behaviour gets a person away from something or gets something taken away from them through their own actions i.e. another person is in no way involved. Three examples of automatic negative reinforcement include:

Example One: When you brush your teeth to remove dirt. Here your own behaviour is reinforced by the fact that you get what you wanted – the removal of dirt from your teeth – and as you did the brushing yourself and no-one else was involved, it is termed “automatic”.

Here your own behaviour is reinforced by the fact that you get what you wanted – the removal of dirt from your teeth – and as you did the brushing yourself and no-one else was involved, it is termed “automatic”.

Example Two: Scratching an itch (Cooper et al, 2007). Here the function of the behaviour is to stop, reduce or avoid any kind of unpleasant internal stimulation or feeling. So before the behaviour occurs the person would be “feeling” some kind of unpleasant stimulation e.g. pain, and then after the behaviour this internal stimulation is gone.

Example Three: Avoiding having to complete a school report by tidying your room. Here the function of the behaviour is to get away from or avoid having to engage in some kind of activity as a result of your own actions i.e. no one else was involved with the avoidance of the activity. So before the behaviour occurs the person may be currently engaging in an unpleasant activity or be about to engage in the activity and then after the behaviour the person is able to get away from the activity or get out of having to engage in the activity

References

- Cooper, J.

, Heron, T., & Heward, W. (2007). Applied Behaviour Analysis. New Jersey: Pearson Education.

, Heron, T., & Heward, W. (2007). Applied Behaviour Analysis. New Jersey: Pearson Education. - Miltenberger, R. (2008). Behaviour Modification. Belmont, CA. Wadsworth Publishing.

- O'Neill, R., Horner, R., Albin, R., Sprague, J., Storey, K., & Newton, J. (1997). Functional Assessment and Programme Development for Problem Behaviour: A Practical Handbook. Pacific Grove, CA. Brooks/Cole Publishing Company.

- Tarbox, J., Wilke, A., Najdowski, A., Findel-Pyles, R., Balasanyan, S., Caveney, A., Chilingaryan, V., King, D. et al (2009). Comparing Indirect, Descriptive, and Experimental Functional Assessments of Challenging Behavior in Children with Autism. Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 21, 493-514. DOI: 10.1007/s10882-009-9154-8

Stages of functional assessment of behavior. ~ Autism | ABA

Some ABA professionals are not always able to break down complex, professional terminology into simpler concepts, and explain behavior in such a way that a busy mother of three or a tired 2nd teacher after a working week would be able to put ABA methods into practice. Professionals need to think about the fact that most of the advice they write or say out loud will be implemented by someone else. Hours can be spent writing the most effective, evidence-based intervention program, but if family members or teachers end up unable to deliver such an intervention, then what's the point?

Professionals need to think about the fact that most of the advice they write or say out loud will be implemented by someone else. Hours can be spent writing the most effective, evidence-based intervention program, but if family members or teachers end up unable to deliver such an intervention, then what's the point?

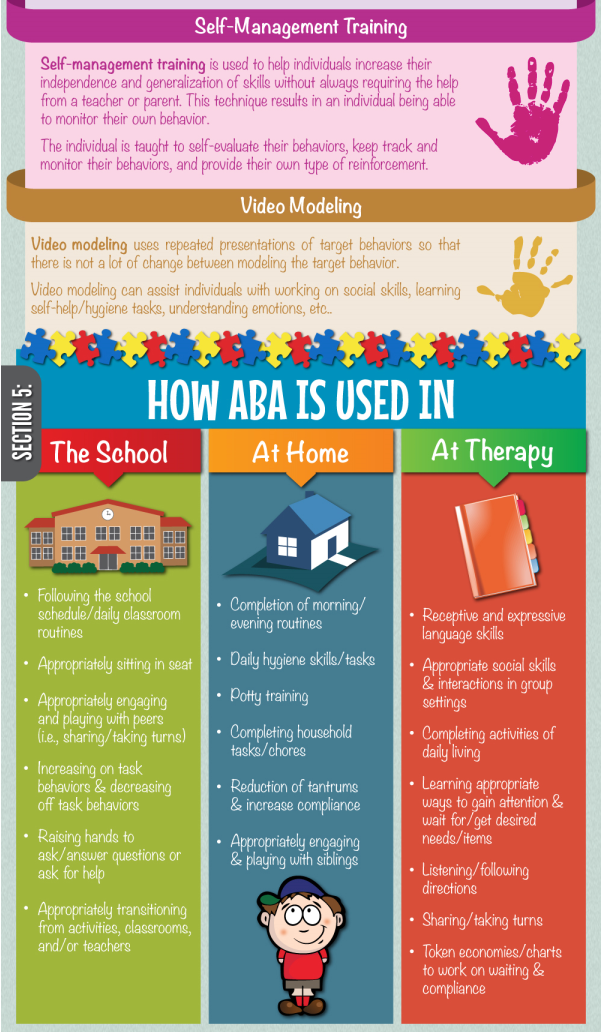

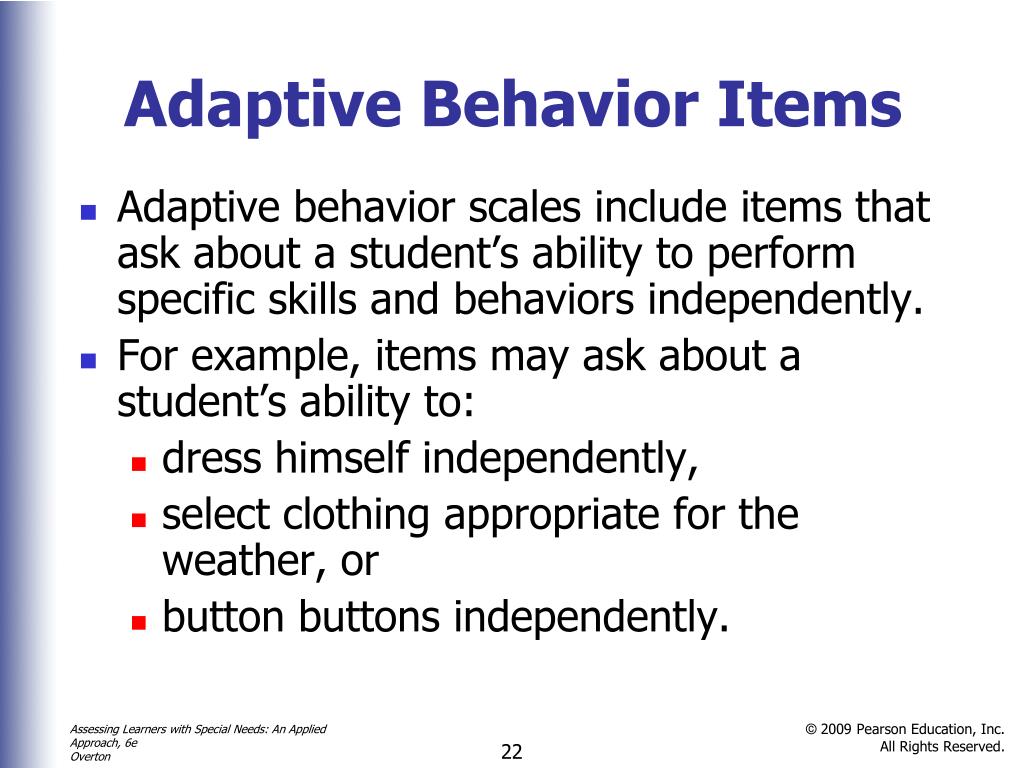

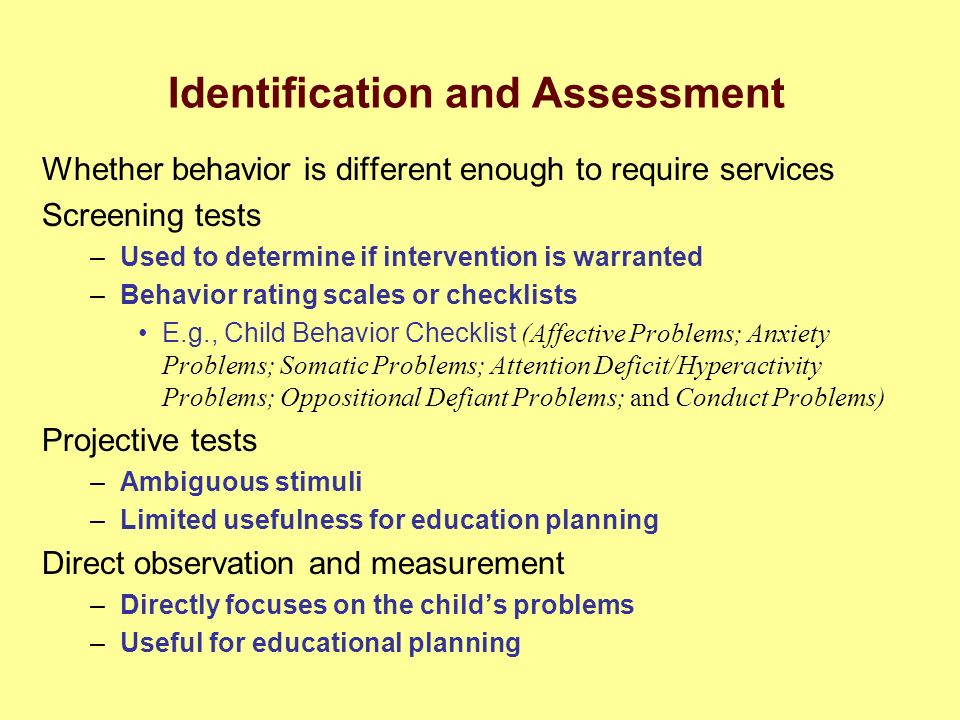

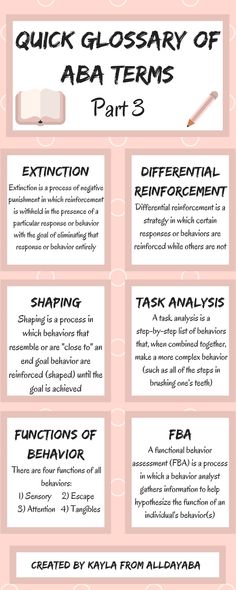

Part of the responsibilities of an ABA professional is to educate and train people to a level that makes applied behavior analysis procedures easy to understand and implement. This is part of the delivery of effective therapeutic services. Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) is the behavioral analytical tool that will be discussed in this publication (Functional Behavior Analysis is a more complex and sophisticated way of determining the function of behavior through the manipulation of environmental factors; a full Functional Behavior Analysis is always performed by an experienced ABA specialist ). All people involved in the care and education of an autistic child should be familiar with the concept of functional behavioral assessment.

Functional Behavior Assessment is a tool used to determine the function of a behavior and then develop an intervention based on that function. This publication is for informational purposes only and if you are experiencing significant behavioral problems with your child or student, we encourage you to contact the BCBA for a full and comprehensive functional assessment of that child's behavior and to develop a professional behavioral intervention program.

To understand what a functional assessment of behavior is, it is first necessary to define the concept of "behavior". Behavior is something an organism does in response to a stimulus. Simply put, behavior is observable activity. According to this definition, speaking is behavior, but thinking is not, because we cannot observe someone else's thoughts.

All behavior occurs for a reason, and the goal of FBA is to identify that reason. Once the cause is identified, the development of an intervention, or plan of action, can begin. The need for a functional assessment of behavior arises whenever a reduction in some behavior is required.

The need for a functional assessment of behavior arises whenever a reduction in some behavior is required.

ABA practitioners are often asked the question, "Should I do a functional behavioral assessment in order to intervene in behavior?". The answer is no, you shouldn't. However, people working with problem behaviors in children should understand that without FBA and determining the factors that support this behavior, they can only guess. And then, on the basis of such guesses, build an intervention program.

In addition, research has shown that when people intervene in behavior without first having an FBA, they tend to focus on easing or punishing. In other words, parents or professionals only focus on stopping the behavior, but do not pay enough attention to teaching alternative, replacement behavior. A real life example that probably every specialist has come across in their practice is the mother or father of an autistic child who does not like the fact that their child exhibits auto-stimulating behavior, for example, putting his fingers in his mouth. Every time parents see this behavior, they forcefully pull the child's fingers out of their mouths. What this strategy lacks is teaching the child the behavior that the parents would like to see instead of sticking fingers in their mouths.

Every time parents see this behavior, they forcefully pull the child's fingers out of their mouths. What this strategy lacks is teaching the child the behavior that the parents would like to see instead of sticking fingers in their mouths.

A functional behavioral assessment is done to reduce or eliminate problematic behaviour. Problematic behavior is usually attributed to aggression, tantrums, disobedience, auto-aggression, running away, swearing, absenteeism from school, etc. Ideally, in such a situation, the entire process of functional behavior analysis should be conducted by a certified behavioral therapist. However, some school districts or families may not be able to hire a BCBA, or the child may live in an area where such professionals simply do not exist. If for some reason you do not have direct access to professional behavioral therapists, the information in this publication will help each person to understand the main stages of the FBA.

Functional behavior assessment has 3 main steps:

- Gathering information, consultation

- Direct observation, development of a hypothesis

- Creation of an action plan, consultation

Stage 1:

behavioral problems, about the environment and the possible functions of behavior. As a rule, specialists conduct 1-2 interviews with parents (or teachers, if the request for FBA was made by the school), review the child's records (educational documents, Individualized Education Plan (IEP), recent conclusions of a psychologist, doctor, etc.), and also collect information from parents about possible replacement alternative behaviors.

As a rule, specialists conduct 1-2 interviews with parents (or teachers, if the request for FBA was made by the school), review the child's records (educational documents, Individualized Education Plan (IEP), recent conclusions of a psychologist, doctor, etc.), and also collect information from parents about possible replacement alternative behaviors.

It is important to involve parents in every step of the FBA as it helps to ensure that parents are active participants in the intervention. The goal at this stage is to collect information about the problem behavior, when it occurs, how long it lasts, what it looks like, whether there has been a recent deterioration, what typically triggers it, and how parents respond to the child's problem behavior. It is worth asking what strategies parents have already tried in an attempt to stop unwanted behavior.

Step 2:

The next step is to observe the child's behavior directly. Sometimes this can be a difficult task. Since the evaluator is usually unknown to the child and the child has no experience of reinforcement of unwanted behavior by the evaluator, it often happens that during the observation the child does not show any behavioral problems, which bewilders his parents. If it is still possible to observe problematic behavior of the child, it is necessary to pay special attention to the antecedent factors and consequences of such behavior. If the undesirable behavior does not occur, you can make direct trials. For example, if the parents say that the child has tantrums every time they bathe him, then you can ask the parents to bathe him in your presence. However, if we are talking about potentially unsafe situations, for example, when parents say that after the word "No" the child starts banging his head, then it would be unethical to artificially recreate such situations. In such a case, either schedule more follow-up visits or ask the parents to videotape the behavior the next time it occurs.

Since the evaluator is usually unknown to the child and the child has no experience of reinforcement of unwanted behavior by the evaluator, it often happens that during the observation the child does not show any behavioral problems, which bewilders his parents. If it is still possible to observe problematic behavior of the child, it is necessary to pay special attention to the antecedent factors and consequences of such behavior. If the undesirable behavior does not occur, you can make direct trials. For example, if the parents say that the child has tantrums every time they bathe him, then you can ask the parents to bathe him in your presence. However, if we are talking about potentially unsafe situations, for example, when parents say that after the word "No" the child starts banging his head, then it would be unethical to artificially recreate such situations. In such a case, either schedule more follow-up visits or ask the parents to videotape the behavior the next time it occurs.

At this stage, the professional should already have some hypotheses about problem behavior based on observation and data collected.

There are 4 main functions of problematic behavior: receiving attention or a desired object, automatic reinforcement (sensing), avoidance or evasion of a demand, and the individual's expression of his desires or needs. Often a behavior performs several functions, however, as a rule, there is a main function (primary) and a secondary (secondary).

Stage 3:

After completing the functional behavioral assessment, the next step is to develop a behavioral plan.

A behavior plan is a "plan of action" or intervention that will reduce or eliminate behavioral problems. Typically, the problem behavior reduction plan makes up 50% of the intervention program, with the other 50% of the program devoted to teaching alternative behaviors. In other words, when the child stops showing the problem behavior, what kind of behavior do you expect from him in return? The interventions that are developed should be directly related to the function of the problem behavior. If a child is screaming for sensory input, then ignoring their screams may not be the best choice for an intervention program. The best choice would be, for example, to teach the child to sing songs, which will satisfy his need for sensory sensations.

If a child is screaming for sensory input, then ignoring their screams may not be the best choice for an intervention program. The best choice would be, for example, to teach the child to sing songs, which will satisfy his need for sensory sensations.

Step 3 also needs to be consulted as it is important to involve parents in developing behavioral plans and creating replacement behaviors. If parents feel insecure about your proposed intervention, then you need to find out why this is happening. What exactly do one or both parents disagree with? For example, some parents are reluctant to use blanking procedures, not always understanding the difference between blanking and ignoring. In any case, if the parents disagree fundamentally on any items of the intervention program, it must be rewritten. The child's behavior will still improve, it just might take longer.

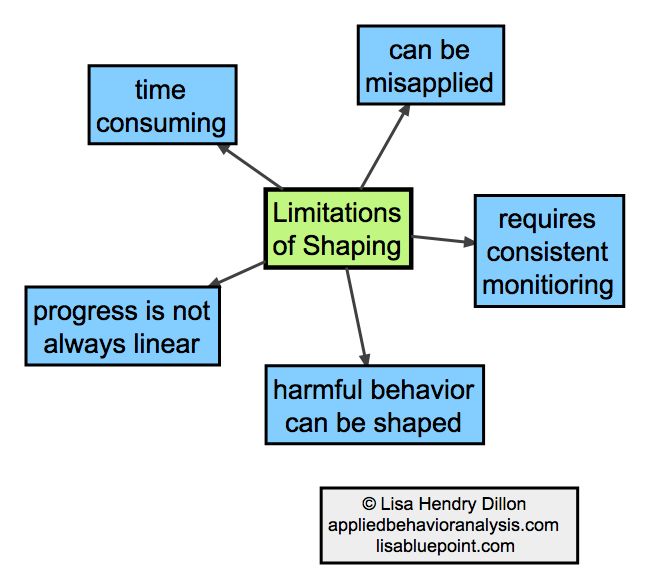

Prompt : Implementing a functional behavioral assessment and developing an intervention program can be a very complex process. Do not be discouraged if learning this skill requires a lot of time and repeated attempts. There is a wealth of information online and in books that can give some insight into FBA design, but these are just examples. All children are unique, and a behavior plan that works for one child may not necessarily work for another.

Do not be discouraged if learning this skill requires a lot of time and repeated attempts. There is a wealth of information online and in books that can give some insight into FBA design, but these are just examples. All children are unique, and a behavior plan that works for one child may not necessarily work for another.

Source: http://www.iloveaba.com/2012/02/everyday-fba.html

Behavior function: automatic gain. ~ Autism | ABA

Functional Behavior Assessment (FBA) is a very individual and unique process that is different for every child. This publication contains some recommendations for implementing the functional assessment process, but they are not universal for all children and all situations. In addition, it is important to note that functional behavior assessment can be used to identify the causes of problem behavior in anyone, not just children with autism.

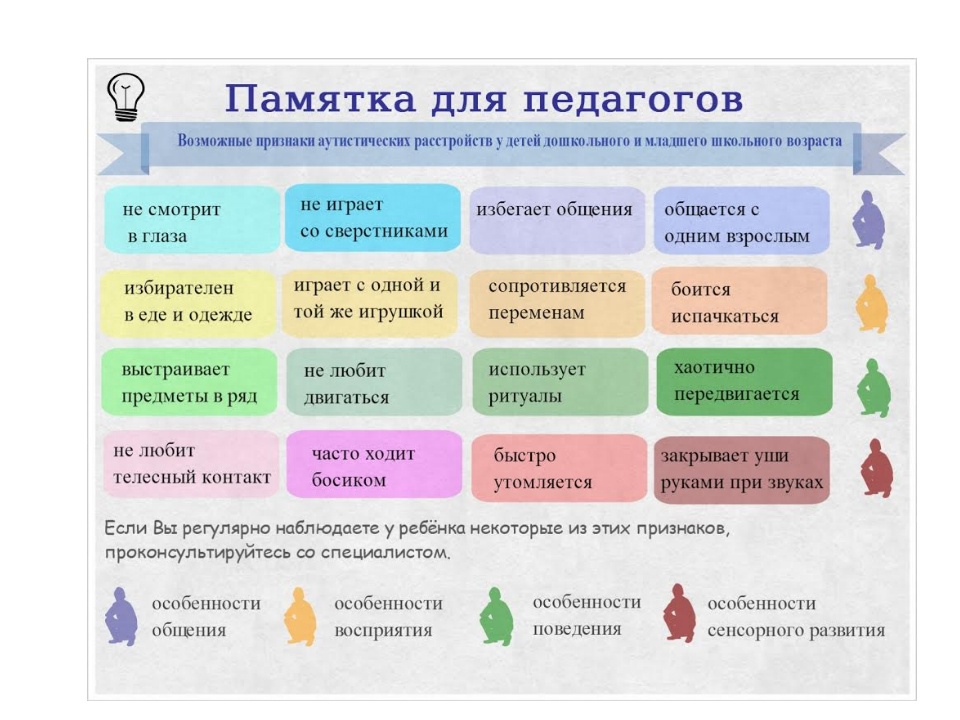

Today's publication is intended for caregivers of autistic children (may be parents, teachers, therapists, etc. ) who have gone through the stages of functional behavioral assessment and have determined that a function of a child's problem behavior is automatic reinforcement.

) who have gone through the stages of functional behavioral assessment and have determined that a function of a child's problem behavior is automatic reinforcement.

Problematic behaviors whose function is sensory stimulation are often referred to as self-reinforcing behaviors. Autostimulation is an example of a behavior that is automatically reinforced. This behavior does not depend on receiving any tangible object/attention or removing the requirement; for the child, it in itself has reinforcing characteristics.

This means:

• The child will exhibit this behavior when alone

• The child will exhibit this behavior if no demands are placed on it

• The child will exhibit this behavior if they lose any rewards, privileges or enhancers

The self-reinforcing behavior serves to stimulate or calm the child's body, and the act of participating in the behavior is its own enhancer. Sometimes it is quite difficult to determine whether the cause of the problematic behavior is really related to the receipt of sensory sensations. If you think that a behavior may have a sensory function, it is recommended that you seek the services of qualified counselors for a functional assessment or functional behavior analysis. It happens that sensory sensations are mistaken as the cause of problem behavior, and if the function of the unwanted behavior is not properly defined, then the intervention is likely to be ineffective.

If you think that a behavior may have a sensory function, it is recommended that you seek the services of qualified counselors for a functional assessment or functional behavior analysis. It happens that sensory sensations are mistaken as the cause of problem behavior, and if the function of the unwanted behavior is not properly defined, then the intervention is likely to be ineffective.

Children whose sensory system is understimulated or easily overstimulated will go to great lengths to bring that system into balance. If the child does not have access to appropriate ways or methods to balance it, problematic behavior appears.

What does sensory stimulation behavior look like?

A feature of sensory behavior is that sometimes it can look like ordinary problematic behavior or sensory deficits. When dealing with this type of behavior, close observation and study of the child is necessary to ensure that the behavior is not supported by positive or negative reinforcement.

Information for Parents and Teachers: If a child engages in problem behaviors when they are alone or when no demands are made, it is likely that this is a sensory stimulation behavior.

Information for ABA Professionals: If there is no clear pattern in the results of the functional behavior assessment or in the data collected, then it may be a sensory stimulation behavior.

Sensory stimulation can occur in any of the sensory systems: visual, tactile, auditory, olfactory, gustatory, vestibular, and proprioceptive. It is important to know the specifics of each of these systems, as any intervention needs to be tailored to the specific needs of each child (visual, tactile, etc.). The amount of stimulation required to maintain these systems depends on the individual child. Some children may stare at fluorescent lights for long periods of time to satisfy their visual need, making it difficult for the teacher to concentrate on the learning process. Others will repeatedly hit themselves on the head with their hands in order to satisfy the needs of the vestibular apparatus.

The most common sensory stimulation behaviors include:

Hand clapping, rocking, bouncing, repeated or continuous vocal noises, fingers in ears, walking on tiptoes, playing with saliva, stuffing food behind cheeks, chewing fingers or clothes , screaming, smearing or playing with feces, licking objects, instantaneous or delayed echolalia, and auto-aggressive behavior.

Why do children engage in sensory stimulation behavior?

Sensory stimulation has the function of modulating the child's sensory system, so children are most likely to exhibit this behavior when they are understimulated or experiencing sensory overload. Problem behavior occurs when there is a mismatch between a child's internal sensory system and their environment.

For example, if at the moment when the child is overstimulated and hyperactive, the parents take him to church and make him sit quietly there for two hours, or, conversely, when the child is low, he is taken to a crowded children's birthday party it is likely that he will exhibit problematic behavior in order to correct this imbalance.

How to deal with sensory stimulation behavior?

Once you have determined the function of the problem behavior, there are two steps to reduce its intensity: 1) stop reinforcing (feeding) the unwanted behavior and 2) teach the child what to do INSTEAD of the behavior . When dealing with sensory-based behavior, it can be difficult to produce true blanking (blanking means breaking the link between gain and behavior). This is because certain types of protective equipment are used to truly damp sensory behavior. For example, the procedure for dampening the sensory behavior of a child who bangs his head would require the use of a special helmet. Generally, most parents of autistic children are reluctant to use protective clothing at home or in public places. For this reason, work on self-reinforcing behavior is typically done by combining response blocking with functionally equivalent replacement behavior. That is, if a child hits a table because he likes the sound it makes, giving him a puzzle to play with is not a functionally equivalent proposal.