Why do people feel guilty

What Causes Guilt & How To Overcome It

Written by Dr. Mark Winwood

Dr Mark Winwood is a leading figure in the mental health field and AXA Health’s Consultant Psychologist.

Find out moreMost of us feel guilt from time to time – it’s part of our human nature and completely normal. From guilt about not spending as much time as we’d like with loved ones, saying no to friends or colleagues, to cheating on a partner. And because we’re all unique, we respond to it in different ways.

In its true sense, guilt is a feeling of remorse or sadness over a past action, experienced when we think we’ve caused harm or breached our moral code. It’s our moral compass. Our values and how we process our emotions will all inform the way we react to certain situations. So while one person might catastrophise about a situation, another may not think twice about it.

Types of guilt

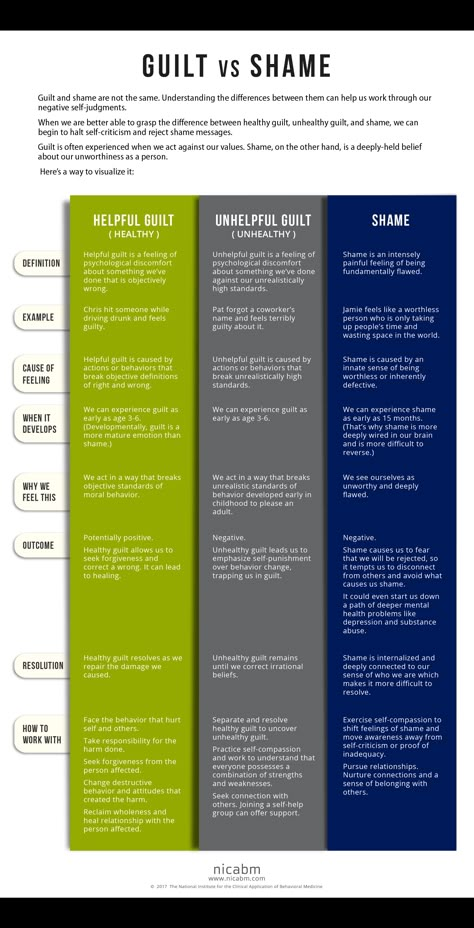

Guilt falls into two categories – healthy, appropriate guilt and unhealthy, irrational guilt.

Appropriate guilt

Although an unpleasant feeling, ‘appropriate’ guilt helps to regulate our social behaviour1. Feeling guilty for a justifiable reason is a sign that our conscience and cognitive abilities are working properly to stop us repeating or making mistakes. This gives us the opportunity to learn and change our behaviour in the future.

The perpetual feeling of guilt is known as ‘guilt-proneness’ and people who experience guilt prone-ness are believed to have a strong connection with their own – and others’ – emotions.

Irrational guilt

The irrational kind – when we mistakenly assume responsibility for a situation, or overestimate the suffering caused – is another matter entirely and can be very damaging if we don’t take steps to resolve it.

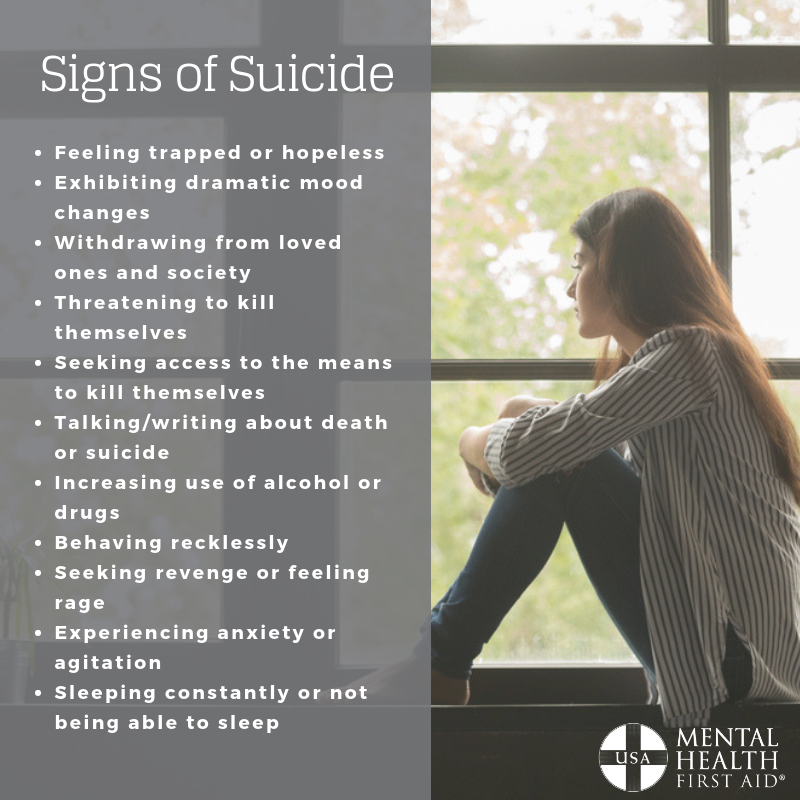

Excessive irrational guilt has been linked to mental illnesses, such as anxiety, depression, dysphoria (feelings of constant dissatisfaction) and obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)2. It can cause sufferers to believe they’re a burden to their loved ones and those around them. Unchecked guilt can also result in flagging concentration and productivity, low mood, increased stress and lack of sleep. As a result, our relationships, daily actions and overall outlook on life can be badly affected.

Unchecked guilt can also result in flagging concentration and productivity, low mood, increased stress and lack of sleep. As a result, our relationships, daily actions and overall outlook on life can be badly affected.

So what can we do to stop these feelings spiralling out of control?

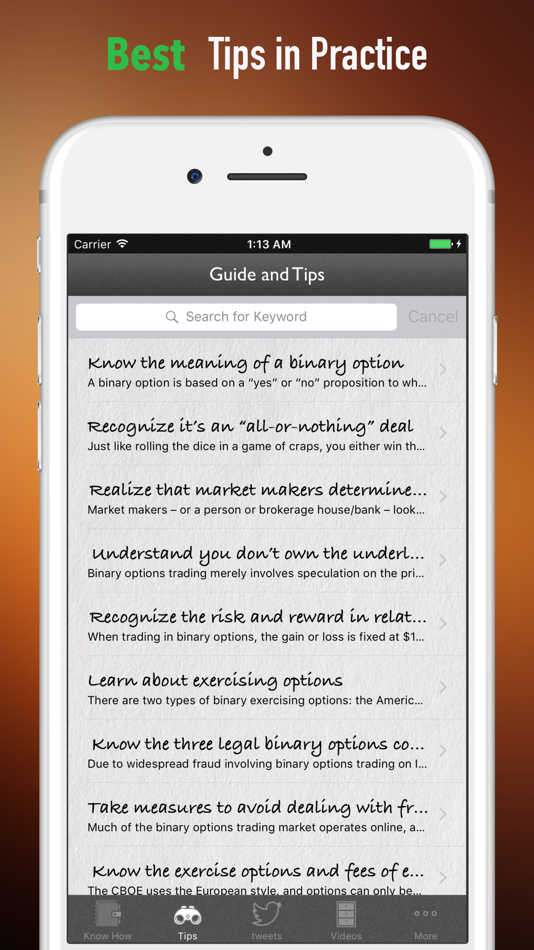

Clinical Lead for Mental Health Services at AXA Health, Dr Mark Winwood has come up with some tips for handling guilt

- Practise mindfulness. Mindful meditation focuses on breathing as a way of paying attention to the moment. This can connect the mind and body and help put your guilt into perspective.

- Distract yourself with whatever helps you relax – your favourite music, a book, some exercise or just a breath of fresh air.

- Be proactive: if you feel that your guilt is justified, and you’ve come to this decision through rational thinking, take action. Learn from your mistakes, make amends and move on.

- Don’t beat yourself up about it.

Constantly revisiting past mistakes won’tbenefit anyone, least of all yourself.

Constantly revisiting past mistakes won’tbenefit anyone, least of all yourself. - Remember that perfection doesn’t exist: looking for the perfect solution can lead to mental ‘gridlock’, which is unhelpful. Learn to accept the ‘best’ solution for the circumstances instead and keep a sense of perspective.

There’s no magical solution to guilty feelings. But if they’re justified, it’s much healthier not to try and get rid of them. Instead, accept them and use them to behave more positively in the future.

Sources

- Jarrett, C (2015). British Psychological Society Research Digest: ”Guilt-prone people are highly skilled at recognising other people’s emotions.”

- Amodio D.M, Devine, P.G, Harmon-Jones, E (2007). A dynamic model of guilt implications for motivation and self-regulation in the context of prejudice. Volume 18, Number 6, p.524/ pre-approved guilt copy for Bella magazine

- Beck, S.J and Niler, E.R (1989). “The relationship among guilt, dysphoria, anxiety and obsessions in a normal population.

” Behaviour Research and Therapy 213-220.

” Behaviour Research and Therapy 213-220.

Guilt | Psychology Today

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

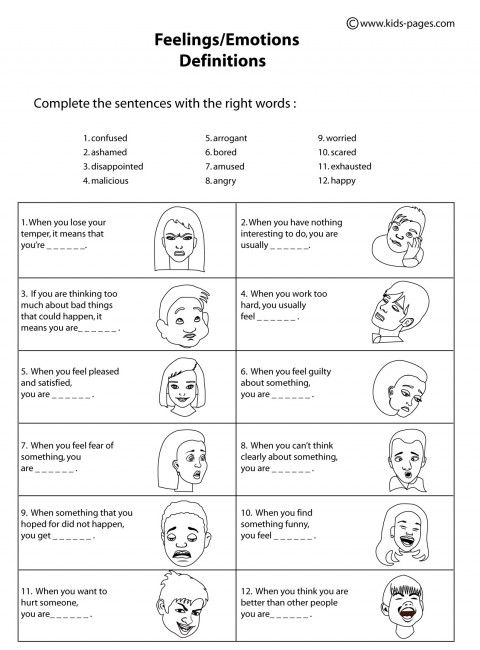

Guilt is aversive and—like shame, embarrassment, or pride—has been described as a self-conscious emotion, involving reflection on oneself. People may feel guilt for a variety of reasons, including acts they have committed (or think that they committed), a failure to do something they should have done, or thoughts that they think are morally wrong.

Contents

- What Is Guilt?

- Coping With Guilt

What Is Guilt?

When one causes harm to another, guilt is a natural emotional response. Guilt is self-focused but also highly socially relevant: It’s thought to serve important interpersonal functions by, for example, encouraging the repair of valuable relationships and discouraging acts that could damage them. But in excess, guilt may needlessly burden those who experience it.

But in excess, guilt may needlessly burden those who experience it.

Can guilt be helpful?

Given how uncomfortable guilt can feel, it can provide a strong motivation to apologize, correct or make up for a wrong, and behave responsibly. Since doing so helps preserve social bonds and avoid harm to others, guilt, despite being a “negative” feeling, can sometimes be good. Research suggests that guilt-proneness may be related to empathy as well as trustworthiness.

Does everyone feel guilt?

Not necessarily. The degree to which people feel guilt varies, and those with certain personalities may experience relatively little (if any) guilt. A lack of guilt and remorse is one characteristic that experts have used to diagnose psychopathy.

What is the difference between guilt and shame?

Shame and guilt are two closely related concepts. While each has been defined in different ways, guilt is typically linked to some specific harm, real or perceived, and shame involves negative feelings about one's self more generally.

While each has been defined in different ways, guilt is typically linked to some specific harm, real or perceived, and shame involves negative feelings about one's self more generally.

Are some people prone to guilt and shame?

Excessive guilt can be a feature of certain forms of mental illness, including depression and post-traumatic stress disorder. The tendency to feel shame has also been associated with depression, anxiety, and other psychological symptoms. Factors such as social stigma related to one’s characteristics may also make shame more likely

When do children begin to feel guilt?

Children begin to feel guilt and may try to make up for guilt-inducing acts by their second year, research suggests, though the experience of guilt and associated behaviors appear to continue developing throughout childhood.

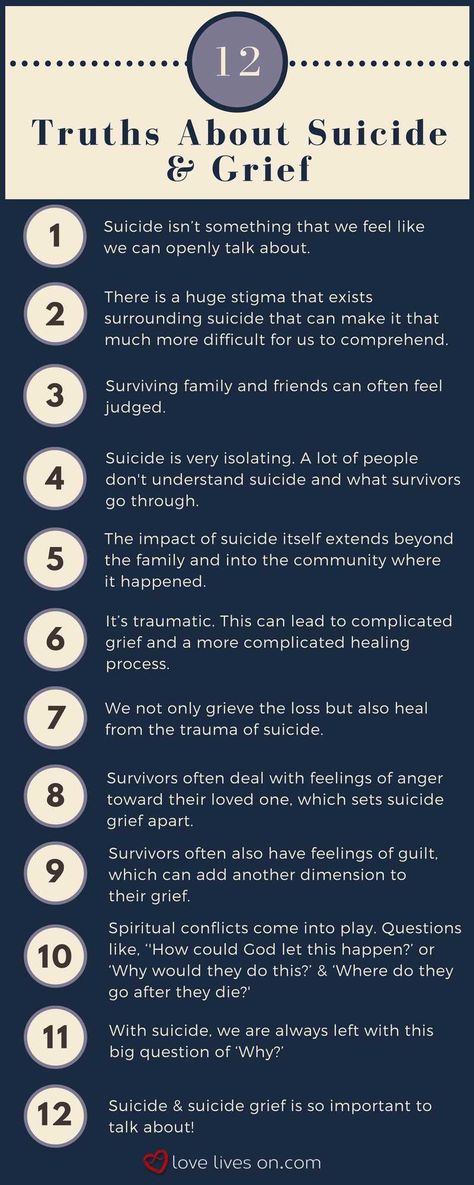

What is survivor’s guilt?

Survivor’s guilt (or survivor guilt) is an emotional experience that results from being relatively unharmed by a situation, compared to others. When one emerges from an accident or a conflict alive while others have died, for example, that person may experience survivor’s guilt—despite not being responsible for the others’ deaths.

When one emerges from an accident or a conflict alive while others have died, for example, that person may experience survivor’s guilt—despite not being responsible for the others’ deaths.

How to Cope With Guilt

Feeling guilt after a misdeed is normal and can often be remedied by apologizing and taking steps to make up for whatever pain or offense has been caused. But many feel guilt that is out of proportion to the harm they have caused, or even disconnected from any real harm. In such cases, it may be necessary to reflect on the reasons for one’s feelings of guilt—perhaps in conversation with a counselor or therapist, especially when an underlying mental health condition may be involved.

Why do I feel guilty about everything?

Though pervasive feelings of guilt are not necessarily a sign of an underlying mental health condition, they can be. Widely used criteria include regular feelings of “excessive or inappropriate guilt” among the symptoms of major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder, and guilt plays a role in other disorders as well. The guilt may be related to repeatedly thinking about minor failures or stem from things that are not actually within a person’s control.

The guilt may be related to repeatedly thinking about minor failures or stem from things that are not actually within a person’s control.

Can you feel guilty for something that isn’t your fault?

Yes. Someone may feel survivor guilt despite bearing no responsibility for circumstances that have harmed others. People with certain kinds of mental illness may feel unwarranted guilt as part of their condition—such as guilt for “bad” intrusive thoughts, in the case of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD).

What are some ways to feel less guilt?

When guilt stems from something you did to someone, apologizing and seeking to avoid repeating your behavior is one clear way to respond and could help you achieve self-forgiveness. But sometimes guilt is unrelated to actual misbehavior or becomes counterproductive. Remedies for unnecessary guilt may include reflecting on factors that were beyond your control, acknowledging what you know now that you didn’t in the past, and considering whether your standards for yourself are too unforgiving.

Can therapy help with guilt?

Yes. Given that guilt can be excessive or undeserved and that guilt can be an aspect of some mental health conditions, therapy can be helpful for addressing intense guilt. There are evidence-supported treatments for depression, for post-traumatic stress disorder, and for other conditions that involve pronounced feelings of guilt (though therapy may be helpful even in the absence of a diagnosed condition).

What are some ways to deal with a “guilt trip”?

When someone tries to instill guilt to get another to behave a certain way—an act often associated with mothers and their children—responding with empathy, while also setting limits when necessary, could help in getting out of the guilt trip. That may include acknowledging the importance of what the guilt-tripping person wants while also asking them to express their wants directly and to respect your decisions.

Essential Reads

Recent Posts

Why do we constantly feel guilty?

Sex, money, work, family, friends, health, food, politics: the only things we don't feel guilty about, including our own reasons for feeling guilty.

I feel guilty about everything. The day hasn't started yet, and the guilt that I told a friend something wrong is already gnawing at me. But it doesn't stop there: I'm guilty of avoiding this friend all day just because I told him. Besides, I didn't have time to call my mother today: it's my fault. I was supposed to come up with something special in honor of my husband's birthday, but I didn't: it's my fault again. I don't always cook healthy food for my child: it's my fault. Lately, I've been frankly hacking at work: I'm to blame. Today I did not have time to have breakfast: it's my fault. Instead, I had a bite to eat on the go: doubly guilty. Feeling that I'm wasting my precious place in this world: I'm guilty, I'm guilty, I'm guilty!

It's not that I like feeling sorry for myself. Certainly not when my sophisticated friends keep reminding me that guilt makes us selfish, conceited, politically conservative, and morally backward. Poor thing: I feel guilty for feeling guilty. Guilt extends to all social roles: we feel like a bad daughter, sister, spouse, mother, bad friend, colleague, middle-class, white, liberal and Jew: and guilt gnaws at us for all this!

Certainly not when my sophisticated friends keep reminding me that guilt makes us selfish, conceited, politically conservative, and morally backward. Poor thing: I feel guilty for feeling guilty. Guilt extends to all social roles: we feel like a bad daughter, sister, spouse, mother, bad friend, colleague, middle-class, white, liberal and Jew: and guilt gnaws at us for all this!

Fortunately, there are those who promise to save us from compulsive guilt. According to popular personal growth coach, Denis Duffield-Thomas, author of Get Rich, Lucky Bitch!, guilt is "one of the most common experiences women experience." Absorbed by this feeling, women themselves put obstacles on the way to the growth of wealth, influence, prestige and happiness; they just don't seem to be able to take advantage of the benefits that are available to them.

“You may feel guilty,” writes Duffield-Thomas, “for wanting something more, for wanting to spend money on yourself, or for snatching up a little bit of family time for self-improvement. You can blame yourself for the fact that other people are poor, that your friend is jealous of you in some way, that there are millions of hungry people in the world. Of course, I feel guilty for all of the above. But, it is a relief to say that I can be helped - I can help myself. For this to happen, I must first understand that:

You can blame yourself for the fact that other people are poor, that your friend is jealous of you in some way, that there are millions of hungry people in the world. Of course, I feel guilty for all of the above. But, it is a relief to say that I can be helped - I can help myself. For this to happen, I must first understand that:

a) I deserve it;

b) none of the global problems such as historical inequality can be my fault.

In other words, the feeling of guilt is not a sign of my involvement in something bad, but rather the opposite - innocence, even some kind of sacrifice on my part. In Duffield-Thomas's words, only by forgiving myself for mistakes for which I am not directly responsible can I free myself from "the fear of spending extra money and living in a big way."

Imagine a first class life. This kind of idea turns guilt into an emotion that we nip in the bud and takes its roots in psychoanalysis and feminist thinking and eventually turns them into a tool for business motivation. The point is that our guilt can be redeemed by making money.

The point is that our guilt can be redeemed by making money.

This thought is vividly reflected in the German language, where guilt and duty are the same word: "schuld". We can cite as an example the thesis of Max Weber about how the "spirit of capitalism" unites our worldly and spiritual wealth, based on the fact that what you earn in this world also serves as a measure of your spiritual virtue, since it directly depends on your diligence, discipline and self-denial.

However, what Weber calls "anxiety relief" within the Protestant work ethic has the opposite effect on a promising self-reliance policy designed to liberate entrepreneurs from guilt. For Weber, in fact, the capitalist pursuit of profit not only does not reduce guilt, but actively exacerbates it - for in an economy that condemns stagnation, there is no place for lazy people.

So the guilt that holds us back also motivates us to work, work, work, continually improve our performance, in the hope that by doing good deeds we can get rid of oppressive guilt. Thus, guilt makes us productive and unproductive, workaholics and slackers, a contradiction that can explain the sometimes extreme measures and fierce efforts that people make, scapegoating others or engaging in self-sacrifice to get rid of the most unbearable emotion, as many believe.

Thus, guilt makes us productive and unproductive, workaholics and slackers, a contradiction that can explain the sometimes extreme measures and fierce efforts that people make, scapegoating others or engaging in self-sacrifice to get rid of the most unbearable emotion, as many believe.

What is the power of guilt? Like inflation, guilt tends to increase and accumulate over time. While we tend to blame religion for condemning man as a sinner, the guilt that was once associated with specific vices—vices for which religious communities could prescribe appropriate punishment—now, in a more secular age, seems to be reflected in almost everything: in food, sex, money, work and unemployment, leisure, health, sports, politics, family, friends, co-workers, strangers, entertainment, travel, the environment, you name it.

In the same way, those who are tempted to assume that public humiliation is a grim relic of the medieval past clearly do not attach sufficient importance to our life online. Being on the Internet, you do not have to wait long until someone starts pointing fingers at you, trying to accuse you of something. But it is hard to imagine that the image of the envious and resentful troll that dominates our time will be such an easy prey, because already at first it can catch the smell of guilt that makes people vulnerable, emanating from its victim.

Being on the Internet, you do not have to wait long until someone starts pointing fingers at you, trying to accuse you of something. But it is hard to imagine that the image of the envious and resentful troll that dominates our time will be such an easy prey, because already at first it can catch the smell of guilt that makes people vulnerable, emanating from its victim.

No one expected that everything would be like this. The great crusaders of modern times had to eradicate our guilt. Guilt, the subject of countless highly intellectual articles, has been denounced by thinkers for draining the life out of us and contributing to psychological destruction. Nietzsche said that guilt makes us weak, Freud causes neuroses, Sartre makes us feigned.

In the second half of the 20th century, various critical theories gained academic recognition, especially in the humanities. These theories sought to show, by referring to class relations, race relations, relations between the sexes, that we are all just cogs in a more complex mechanism of the power system. We may play our part in a regime of oppression, but we are also at the mercy of forces greater than ourselves.

We may play our part in a regime of oppression, but we are also at the mercy of forces greater than ourselves.

In turn, there are questions about the extent of personal responsibility: if all this is true and every situation is based on a complex network of socio-economic relations, then how can each of us be sure that he controls or bears full responsibility for his own life? In such an impersonal light, guilt seems like a useless hangover from a less conscious time.

As a teacher of critical theory, I know how important, decisive for understanding the conclusions it contains. But sometimes I suspected that our desire for systematization and structuring might be fueled by our anxiety about the prospect of discovering that we were on the wrong track. Indirectly empowered, explanatory theories can offer their adherents a reliable system for knowing exactly what point of view to hold, with impunity, on almost everything—as if one could issue an insurance policy that proved that its owner is always right. Also, it often happens that critical thinking takes us far in reasoning - in the right thoughts, which do not necessarily go from words to real actions.

Also, it often happens that critical thinking takes us far in reasoning - in the right thoughts, which do not necessarily go from words to real actions.

The concept that our intellectual box can be as much a response to our guilt as a defense against it may sound familiar to a religious person. In the Bible, ultimately, man commits the fall by being tempted by the fruit from the tree of knowledge. This "knowledge" results in him being expelled from the Garden of Eden, with no way to return. His guilt is a constant, burning reminder of how he once took a wrong turn.

Even in this example, we see that a person's guilt can be deceptive - slippery and seductive, like a snake that led him astray. For if a person has sinned by tasting “knowledge”, the guilt that punishes him, in fact, repeats his crime: shaking his finger and shaking the air with the phrase “I told you so,” the realization of guilt itself appears as a terrible knowledge. This leaves us, as the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips wrote, trapped in this boring and repetitive voice in our head that endlessly corrects, criticizes, censors, judges and accuses us, but "never gives us proper self-knowledge" . Guilt seems to have already shaped our idea of who we are and what we are capable of.

Guilt seems to have already shaped our idea of who we are and what we are capable of.

Could this be the cause of our feelings of guilt? Not our lack of knowledge, but rather our presumption of lack of information? Our desperate need to feel confident, even when we consider ourselves unworthy and worthless, just empty space? When we feel guilty, we can at least be sure of something definitely - finally, to know exactly how we feel - we feel bad.

Perhaps that's why we love crime dramas: they satisfy our longing for certainty, however dark it may be. So, at the beginning of the detective story, we already know about the crime committed, but we still do not know who committed it. By the end of the story, it turns out which criminal is guilty: the case is closed. Thus guilt, in its broadest sense of the role, is what turns our ignorance into knowledge.

However, for the psychoanalyst, guilt is not necessarily related to how guilt is defined by law. Our sense of guilt may be a confession, but it usually precedes an accusation of some kind of crime, the details of which even the perpetrator himself may not be sure.

Although the stories we prefer tend to reveal guilt, it is equally likely that our own guilt is a cover for something else.

Although the "fall" is originally a biblical story, let's forget about religion for a moment. One can simply recall a later and not religious, but undoubtedly secular story about the fall of man. This "story", which has countless narrators, and perhaps one of the most beautiful and compelling, is the German Jew, post-war critic Theodor Adorno. Adorno is famous to this day when he formulated the aftermath of the Holocaust: whoever survived in the world who was able to create Auschwitz is already to blame, at least because they are still part of the same civilization that created the conditions for Auschwitz .

In other words, guilt is our enduring historical heritage. This is our fate, modern people. Thus, says Adorno, we all have a common responsibility, after what happened at Auschwitz, to be vigilant so that we do not again fall into a pattern of thinking, belief and behavior that would bring down this guilty verdict on ourselves. To try to make sense of the Auschwitz affair is to risk becoming an accomplice in the barbarity committed there.

To try to make sense of the Auschwitz affair is to risk becoming an accomplice in the barbarity committed there.

Adorno also believes that our knowledge makes us guilty rather than keeps us safe. For a modern person, this may seem shocking. However, perhaps the most surprising feature of Adorno's view of wine is the idea expressed in his question: “Is it really possible to continue living after Auschwitz, especially for someone who managed to escape by chance, someone who by all rights should have been killed? How can he continue to live? The mere survival of such people requires indifference, the basic principle of bourgeois subjectivity, without which there might not have been Auschwitz; it is the grave fault of those who escaped death.”

According to Adorno, the blame for Auschwitz lies with the whole of Western civilization, but the feeling of guilt is most acutely felt by “those who accidentally managed to get out, those who should have been killed” - a Jew who survived the Second World War.

Adorno's decision to leave Europe to come to New York in early 1938 probably confirms his own sense of guilt. However, his presentation is one of those received by psychologists working with concentration camp victims after the war; they found that "guilt, accompanied by shame, self-judgmental tendencies, are experienced by victims of persecution and apparently far less (if at all) by their perpetrators."

What does it mean if the victims feel guilty and the perpetrators feel innocent? Perhaps objective guilt (for committing an illegal act) and subjective guilt (feeling of guilt) completely contradict each other?

In the post-war years, the concept of "guilt for being alive" was generally seen as a side effect of identifying the victim with his aggressor. It can be difficult for a survivor to forgive themselves afterwards because others have died in their place - why am I still here when they are gone? Guilt may also arise from the fact that he was forced to collude for his own survival. This does not imply any compromising action on the part of the survivor; his guilt may simply be an unconscious way of acknowledging an earlier choice that allowed him to survive while others suffered in his stead.

This does not imply any compromising action on the part of the survivor; his guilt may simply be an unconscious way of acknowledging an earlier choice that allowed him to survive while others suffered in his stead.

Based on this, one can speak of survivor's guilt as a special case of guilt for which we are all responsible, when, realizing or not suspecting it, we are easier to relate to the suffering of others than to our own. Obviously, this is an unpleasant feeling, but it is not difficult to understand. And yet, there remains something very awkward about admitting that survivors of horrific atrocities must feel guilty about their own survival. Instead, shouldn't we try to save the survivor from this (in our opinion) erroneous sense of guilt and thus establish, without fuss and unnecessary argument, his absolute innocence?

This understandable desire, according to historian Ruta Leys, who studies history through the prism of famous cultural bearers of the corresponding era, was embodied in the image of the “survivor” that emerged after the Second World War, along with a shift in attention from the guilt of the victim to the assertion of her innocence. This transformation, according to Leys, is associated with the replacement of the concept of guilt with its close relative - a sense of shame.

This transformation, according to Leys, is associated with the replacement of the concept of guilt with its close relative - a sense of shame.

The difference is of great importance. A victim who feels guilty definitely has his own desires and intentions, while a victim weighed down with a sense of shame is subject to the imposition of opinions from outside. Victims of inflicted trauma are usually the objects of history rather than its subjects.

Shame tells us a lot about who a person is, not about what he does or would like to do. Thus, the effect of deliberate shifting of emphasis is to deprive the survivor of the cover.

It may be very tempting to suggest that survivors' feelings of guilt are something extraordinary, especially given the pitiful impotence of the victims of such traumas. But, you can also notice that all attempts to deny someone else's guilt very often are also a denial of other people's intentions. It is worth considering the case of "liberal guilt". The guilt we all just hate.

The guilt we all just hate.

The concept of liberal guilt most often refers to those who acutely feel the lack of social, political and economic justice, but not those who directly suffer from it. According to cultural critic Julie Ellison, the term first emerged in the US in the 1990s, after the end of the Cold War, amid a split on the left and a loss of faith in the utopian politics of collective action that characterized the previous generation of radicals. The guilty liberal renounces the collective and begins to act on the basis of his own interests. Guilt shows the gap between how a person relates to other people's suffering and his specific actions to alleviate them - which, as it turns out, are not so many.

Thus, the feeling of guilt kindles more enmity in others than in the person who feels himself the object of liberal guilt. This so-called "victim" is well aware of how rarely the pity he feels leads to any significant structural or political changes for himself.

Source: The Guardian

Why guilt poisons life, how it is masked and what to do with it

cause other people's troubles) has a variety of manifestations and is not always directly related to "guilt" or "guilty". This feeling can appear not only where a person could be guilty. It can occur in any situation where there was severe stress (in the language of psychology - trauma).

Having arisen in the human psyche, this unpleasant feeling performs an important function - it helps to adapt to a difficult situation in order to survive it with less damage: instead of focusing on a traumatic situation, we look at guilt, because it is not so painful and requires less inner work. It can be said that the feeling of guilt itself is almost accidental and any other negative attitude could have formed in its place. But why is guilt so popular and why do we talk about it so often?

Advertising on RBC www.adv.rbc.ru

It is believed that at an unconscious level, self-blame can already happen in an infant, that is, this mechanism is familiar to us from the time when we could neither express something in words, nor fully realize what was happening. With the advent of mature thinking, the “guilt feeling” tool becomes even more convenient to use.

With the advent of mature thinking, the “guilt feeling” tool becomes even more convenient to use.

For a small child, parents are a bulwark of security, strength and stability. They ensure its survival and development. Unconsciously, infants and young children place implicit trust in the authority of their parents. But if for some reason the child suffers from the behavior of the parents, he is faced with a dilemma: who is wrong? His almighty parents, whom he still unconditionally adores and reveres, or is the problem in himself? In order not to shake the stability of his existence, the child unconsciously turns the blame on himself for the fact that something went wrong between him and his parent. In some situations, this attitude remains with a person for many years to come and may dictate his line of behavior.

The good news is that psychotherapy helps to process this problem and stop living the pattern of the traumatic event that has settled in the unconscious. Contrary to rumors, psychotherapy is not designed to penetrate into every corner of the subconscious and get to the memories of the infancy period. Often it is enough to pay attention to the external manifestations of the problem in order to get closer to understanding the causes of guilt, to work through them and change the behavior to a safe and productive one.

Often it is enough to pay attention to the external manifestations of the problem in order to get closer to understanding the causes of guilt, to work through them and change the behavior to a safe and productive one.

Working with guilt is the cultivation of new, healthy habits in the perception of reality and behavior.

© Caleb Woods/Unsplash

Guilt has many faces and takes many forms besides the direct feeling of "one's own guilt".

- Apologies

First, notice if you have a habit of being overly apologetic. "Excuse me, can I come in?", "I'm sorry if I'm taking up your time." In such situations, using an apology, we try to soften our intervention, although this can be done with other courtesies.

If you are familiar with this behavior, try to think about what you are really apologizing for. For yourself, who bothered someone more important than yourself, or maybe for yourself, who has no right to count on something?

The mechanism of inappropriate apologies, disproportionate to the situation, can also be used by people who are prone to self-blame.

- "I don't deserve happiness" attitude

A chronic sense of one's "badness", inconsistency with ideals (invented by oneself or instilled by other people) may indicate that you are controlled by a sense of guilt. It makes you think that you are not worthy of any praise, or a happy life, or anything that you would really like.

An example is the continuation of an unhappy relationship or marriage “for the sake of children” (“so as not to upset the mother”, “in order to preserve the union”), “a positive image in the eyes of others”. For such people, the idea that you can defend your interests and be happy is almost sinful, because your own well-being takes the last place among all other "more important" motives.

Existing next to an unloved person for the sake of some higher goal is a clear reflection of the inner attitude “I am not worthy of happiness”, which directly relates to guilt.

- Aggression

Another pole of guilt is aggression directed both at other people and at oneself.

Aggression in guilt is an unexpressed complaint against an offender who once harmed your self-esteem, self-respect and positive self-image. Here we are talking about unconscious perception, and if you cannot say for sure what the problem is, then the conflict remains in your psyche and all its participants with their roles are immortalized at an unconscious level.

If after the conflict there was no "revenge" (for example, a constructive showdown), it is likely that the subconscious desire to punish the enemy will follow on the heels until it finds a way out.

Obvious examples of undisguised aggression include the habit of criticizing others and the desire to be right, to have the last word in any situation. Such behavior is characteristic of those people who internally despises the right to make a mistake, who considers even their most insignificant imperfection to be a weakness. By criticizing others, people often ward off the danger that someone they think might see their imperfections. They seem to attack first. Or they make excessive demands on themselves, strictly follow them and cannot forgive everyone else for other behavior.

They seem to attack first. Or they make excessive demands on themselves, strictly follow them and cannot forgive everyone else for other behavior.

So if you notice a habit of criticizing others (inwardly or out loud), remember the feeling you get when you do it. Try to understand how this feeling is useful to you, what it gives, for what reason you need to experience it over and over again.

Quite often the feeling of guilt is accompanied by unexpressed aggression. If in the case of the habit of criticizing we see its clear manifestation, then repressed aggression is not so straightforward. It can take the form of mild hostility (for example, some people bristle in a stressful situation), conflict at work, aggressive driving style - that is, those manifestations that a person usually knows about and has learned to control. But sometimes repressed emotions can manifest themselves in paradoxical ways.

For example, excessive friendliness or fear of expressing one's dissatisfaction, fear of standing up for one's needs, getting one's way, having a constructive argument. Fear of expressing aggression (and, possibly, receiving it in your address) and the inability to express it lead to the fact that a person is looking for ways to merge with other people, to be convenient for others. The fear of being rejected leads to the fear of defending one's interests.

Fear of expressing aggression (and, possibly, receiving it in your address) and the inability to express it lead to the fact that a person is looking for ways to merge with other people, to be convenient for others. The fear of being rejected leads to the fear of defending one's interests.

© Anthony Tran/Unsplash

- Anxiety

In another, not the most obvious way, the feeling of guilt finds its way out through high anxiety.

At some time in our lives, we all experience anxiety: because of illnesses of loved ones, at work in conflict with colleagues, when we hear sad news, and the like. But the anxiety of a healthy person is proportionate to the situation and passes with time.

High anxiety is a wide range of painful conditions that are difficult to control and sometimes difficult to track (“Something torments me, although objectively everything is fine in life”).

High anxiety can result in poor health, the cause of which doctors cannot find, problematic sleep, “unreasonable” mood swings, overeating, or, conversely, an obsession with diet, overwork, or a breakdown. Anxiety has many symptoms, and if any of these are familiar to you, then this is an occasion to consider the causes.

Anxiety has many symptoms, and if any of these are familiar to you, then this is an occasion to consider the causes.

Anxiety can be chosen by the subconscious as a channel through which the tension from the main problem, the feeling of guilt, comes out. This happens when it is so unbearable or such a difficult experience is associated with it that the psyche refuses to even look in that direction and tries to control at least what it can. This is how anxiety appears: the object of anxiety is selected and all forces are directed to combat it.

This is a really complex construct, and in order to eradicate anxiety, you need to eliminate the root cause. It is much easier to do this in tandem with a psychologist. Therefore, if you are familiar with anxiety, but do not know what caused it, tell a specialist about it. This mechanism is familiar to him, and you will quickly come to a solution to your painful condition. Plus, the therapist is free of your feelings of guilt, does not play by his rules, and contact with someone who does not play by the rules of guilt is already very useful in itself.

Guilt devours a person's resource, because he has to devote his life forces to "servicing" this problem.

Living with guilt is extremely costly, and at one point it can lead to collapse, so it is very important to deal with disturbing symptoms and work them out on your own or in psychotherapy. Among these symptoms are nervous breakdowns, alcohol and drug abuse, chronic illnesses, and many other manifestations that make life hard, poor and unhappy.

© Anthony Tran/Unsplash

Since we are talking about unconscious processes, the changes must also occur there. The most effective way is, of course, psychotherapy: long-term or short-term, individual or in a group - your wishes can be discussed with a psychologist or therapist who, having understood your request and collected an anamnesis, will offer a treatment regimen.

In order to understand the problem yourself, you can use several approaches from cognitive psychology.

- Note under what circumstances and with what people you most often feel guilt.

Write down and analyze: are there similarities in these situations and people? And then remember if there was a similar situation with you before. Perhaps in your childhood or adolescence.

Write down and analyze: are there similarities in these situations and people? And then remember if there was a similar situation with you before. Perhaps in your childhood or adolescence. - When you are caught up in this experience, try to keep track of what is happening to you physically and psychologically. Notice the reactions of the body and mind. Developing such sensitivity is useful in order to learn to separate yourself from your reactions, and ultimately control them.

- Carry out self-training with you. Remind yourself that the situation was in the past, and although it has an extension into the present, you do not have to follow this scenario. Often tell yourself that there is no ideal world, ideal situations, and even more so ideal people. The desire to be perfect leads to neurosis. It is optimal to strive to be good enough and give yourself the right to make mistakes. Remind yourself that you have control and there are many ways you can overcome your suffering.