Which race cheats the most

Who Cheats More? The Demographics of Infidelity in America

The last few months of 2017 treated us to a whirlwind of news coverage on sexual harassment and abuse, with powerful men from Hollywood to Washington, D.C. falling because of sexual misconduct. It continues into the new year, with Missouri Governor Eric Greitens the latest to fall. And most of these men are married.

When Time magazine picked the silence breakers as the 2017 “person of the year,” few people paid attention to the other group of women negatively impacted by the fallout—the spouses of the men who engaged in inappropriate or even criminal (in some cases) sexual behavior. To these women, sexual harassment/abuse also means infidelity.

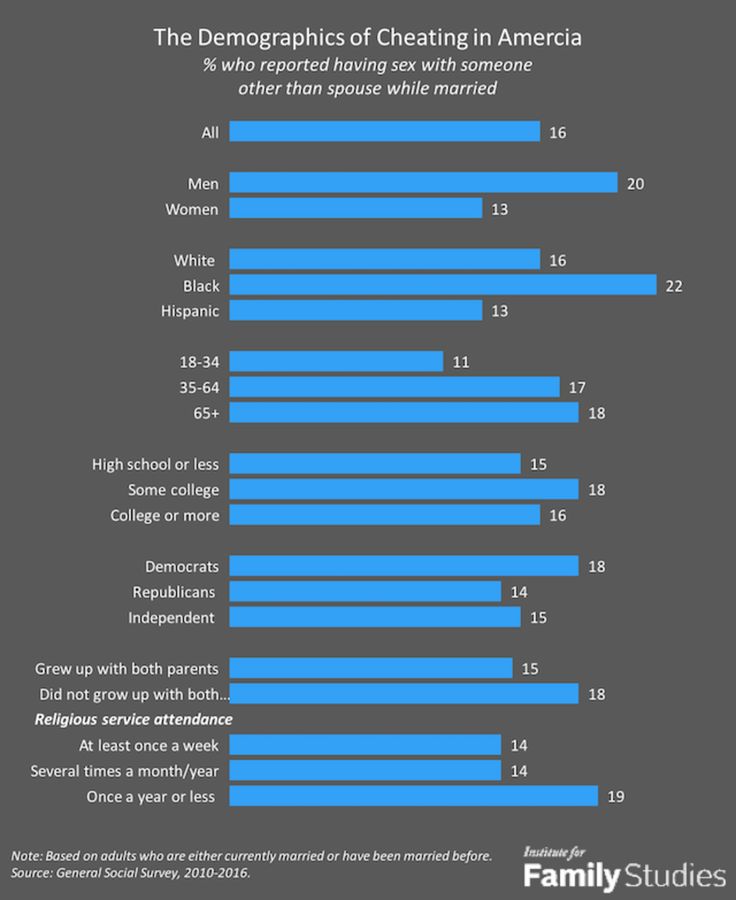

In general, men are more likely than women to cheat: 20% of men and 13% of women reported that they’ve had sex with someone other than their spouse while married, according to data from the recent General Social Survey(GSS).

However, as the figure above indicates, this gender gap varies by age. Among ever-married adults ages 18 to 29, women are slightly more likely than men to be guilty of infidelity (11% vs. 10%). But this gap quickly reverses among those ages 30 to 34 and grows wider in older age groups. Infidelity for both men and women increases during the middle ages. Women in their 60s report the highest rate of infidelity (16%), but the share goes down sharply among women in their 70s and 80s. By comparison, the infidelity rate among men in their 70s is the highest (26%), and it remains high among men ages 80 and older (24%). Thus, the gender gap in cheating peaks among the oldest age group (ages 80+): a difference of 18 percentage points between men and women.

Trend data going back to the 1990s suggests that men have always been more likely than women to cheat. Even so, older men were no more likely to cheat than their younger peers in the past. In the 1990s, the infidelity rate peaked among men ages 50 to 59 (31%) and women ages 40 to 49 (18%). It was lower for both men and women at the older end of the age spectrum. Between 2000 and 2009, the highest rate of infidelity shifted to men ages 60 to 69 (29%) and women ages 50 to 59 (17%). Meanwhile, the gender gap at ages 80+ increased from 5% to 12% in two decades.

Between 2000 and 2009, the highest rate of infidelity shifted to men ages 60 to 69 (29%) and women ages 50 to 59 (17%). Meanwhile, the gender gap at ages 80+ increased from 5% to 12% in two decades.

A generation or cohort effect is likely to contribute to this shifting gender gap in infidelity. As Nicholas Wolfinger noted in an earlier post, Americans born in the 1940s and 1950s reported the highest rates of extramarital sex, perhaps because they were the first generations to come of age during the sexual revolution. My analysis by gender suggests that men and women follow a slightly different age pattern when it comes to extramarital sex. Women born in the 1940s and 1950s are more likely than other women to be unfaithful to their spouse, and men born in the 1930s and 1940s have a higher rate than other age groups of men. The higher infidelity rates among these two cohorts contribute to the changing pattern in the gender gap as they grow older over time.

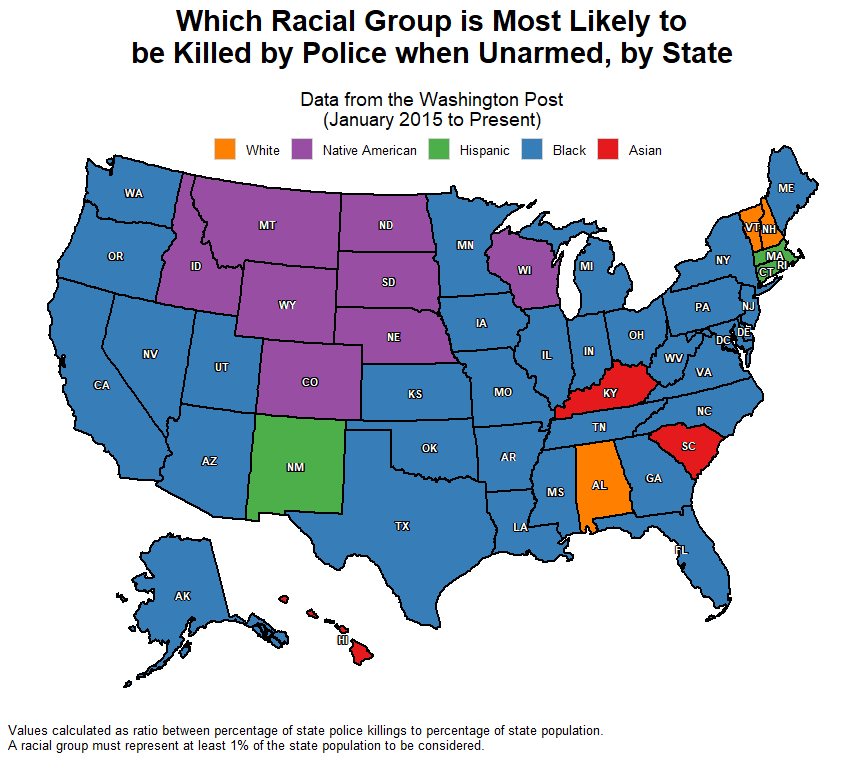

In addition to gender and age, the infidelity rate also differs by a number of other demographic and social factors. For example, cheating is somewhat more common among black adults. Some 22% of ever-married blacks said that they cheated on their spouse, compared with 16% of whites and 13% of Hispanics. And among black men, the rate is highest: 28% reported that they had sex with someone other than their spouse, compared with 20% of white men and 16% of Hispanic men.

For example, cheating is somewhat more common among black adults. Some 22% of ever-married blacks said that they cheated on their spouse, compared with 16% of whites and 13% of Hispanics. And among black men, the rate is highest: 28% reported that they had sex with someone other than their spouse, compared with 20% of white men and 16% of Hispanic men.

A person’s political identity, family background, and religious activity are also related to whether or not they cheat. Overall, Democrats, adults who didn’t grow up in intact families, and those who rarely or never attend religious services are more likely than others to have cheated on their spouse. For example, 15% of adults who grew up with both biological parents have cheated on their spouse before, compared with 18% of those who didn’t grow up in intact families.

On the other hand, having a college degree is not linked to a higher chance of cheating. Almost equal shares of college-educated adults and those with high school or less education have been unfaithful to their spouse (16% vs. 15%), and the share among adults with some college education is slightly higher (18%).

15%), and the share among adults with some college education is slightly higher (18%).

Given that many of these factors could be interrelated, I ran a regression model to test the independent effect of each factor. Basically, holding all other factors equal, will each factor still be related to the odds of cheating? It turned out that most of these differences (such as age, race, party identity, religious service attendance, family background) are significant, even after controlling for other factors. And a person’s education level is not significantly associated with cheating.

However, when it comes to who is more likely to cheat, men and women share very few traits. Separate regression models by gender suggest that for men, being Republican and growing up in an intact family are not linked to a lower chance of cheating, after controlling for other factors. But race, age, and religious service attendance are still significant factors. Likewise, men’s education level is also positively linked to their odds of cheating. By comparison, party ID, family background, and religious service attendance are still significant factors for cheating among women, while race, age, and educational attainment are not relevant factors. In fact, religious service attendance is the only factor that shows consistent significance in predicting both men and women’s odds of infidelity.

By comparison, party ID, family background, and religious service attendance are still significant factors for cheating among women, while race, age, and educational attainment are not relevant factors. In fact, religious service attendance is the only factor that shows consistent significance in predicting both men and women’s odds of infidelity.

Infidelity is painful to the person who is being cheated on and can be detrimental to the relationship. Although statistics on the link between infidelity and divorce are hard to find, my analysis based on GSS data suggests that adults who cheated are much more likely than those who didn’t to be divorced or separated.

Among ever-married adults who have cheated on their spouses before, 40% are currently divorced or separated. By comparison, only 17% of adults who were faithful to their spouse are no longer married. On the flip side, only about half of “cheaters” are currently married, compared with 76% of those who did not cheat.

Men who cheated are more likely than their female peers to be married. Among men who have cheated on their spouse before, 61% are currently married, while 34% are divorced or separated. However, only 44% of women who have cheated before are currently married, while 47% are divorced or separated.

This gender difference could reflect the fact that men are more likely to be remarried than women after a divorce. A portion of currently married “cheaters” may be remarried, since we can't tell from the data whether or not the person who cheated is still married to the spouse he or she cheated on.

Wendy Wang is director of research at the Institute for Family Studies and a former senior researcher at Pew Research Center, where she conducted research on marriage, gender, work, and family life in the United States.

Predicting Infidelity: An Updated Look at Who Is Most Likely to Cheat in America

Every few months, the American public is treated to the latest spectacle of public figures caught cheating on a spouse—the latest scandals include Jerry Falwell Jr. ’s wife and a pool attendant, and NBC Universal executive Ron Meyer. Despite the regularity of these revelations, public interest in the cheating behaviors of the rich and famous continues to sell and to sell well.

’s wife and a pool attendant, and NBC Universal executive Ron Meyer. Despite the regularity of these revelations, public interest in the cheating behaviors of the rich and famous continues to sell and to sell well.

Even scholarly work benefits from the notion that “sex sells.” For example, a January 2018 research brief by IFS research director Wendy Wang, “Who Cheats More? The Demographics of Infidelity in America,” continues to be the most-read IFS blog of all time, with over 7 million page views to date.

The following analysis compliments Dr. Wang’s work with national data collected in late 2019 by the survey research group YouGov—the iFidelity Survey.1 It examines 1,282 ever-married individuals using both demographic, attitudinal, and relational predictors of extramarital affairs. Different from previous research, however, this new analysis defines extramarital affair as a “married individual having engaged in physical sexual activity with someone other than their spouse, and without their spouses’ knowledge and consent. ” While this is a stricter definition of cheating than used previously, the overall pattern is largely consistent with findings from previous studies.

” While this is a stricter definition of cheating than used previously, the overall pattern is largely consistent with findings from previous studies.

As with nearly all studies of extramarital affairs, the iFidelity data suggest that men are more likely to report ever having engaged in an extramarital affair. In the survey, 20% of ever-married men and 10% of ever-married women reported cheating on their spouse in the past.2

Although these gender differences are certainly important, other demographic characteristics are related to self-reported infidelity as well. As shown in Figure 2, non-Hispanic White participants were less likely to report extramarital affairs than other participants. Less-educated individuals also reported more affairs while those who had a four-year college degree or higher reported less. However, age, political affiliation, and income were not associated with self-reported infidelity.

This analysis went further than Dr. Wang’s research brief to explore how attitudes and relationship quality are associated with having an extramarital affair. Figures 3a and 3b show these associations. If a participant in the iFidelity survey reported having been cheated on by a spouse in the past, they were also more likely to self-report an extramarital affair. When we asked participants what behaviors they felt represented cheating, 70% labeled six behaviors of the nine behaviors presented as “cheating,” and 30% rated seven or more of the behaviors as cheating. Participants who labeled more than six behaviors as cheating were less likely to report extramarital affairs, relative to their more lenient counterparts. Reporting being “very satisfied” in the relationship and perceiving a relationship as “very stable” were also both associated with lower levels of extra marital affairs.

Wang’s research brief to explore how attitudes and relationship quality are associated with having an extramarital affair. Figures 3a and 3b show these associations. If a participant in the iFidelity survey reported having been cheated on by a spouse in the past, they were also more likely to self-report an extramarital affair. When we asked participants what behaviors they felt represented cheating, 70% labeled six behaviors of the nine behaviors presented as “cheating,” and 30% rated seven or more of the behaviors as cheating. Participants who labeled more than six behaviors as cheating were less likely to report extramarital affairs, relative to their more lenient counterparts. Reporting being “very satisfied” in the relationship and perceiving a relationship as “very stable” were also both associated with lower levels of extra marital affairs.

Finally, the personal importance of religion was related to lower levels of cheating, whereas religious worship service attendance was not.

After finding these basic statistical relationships, the variables were put into the same model to test which of them were related to extramarital affairs, even after controlling for the other variables. On the demographic side, women still reported fewer affairs then men and Hispanic participants reported more affairs than White, non-Hispanic participants. No other demographic variables were associated with extramarital affairs in the model with multiple variables. Nearly all the attitude and relational variables were related to extramarital affairs. Having been a victim of cheating was positively associated with reporting an extramarital affair, while having a strict definition of infidelity, feeling that religion is very important in one’s own life, and perceiving one’s relationship as stable were all less associated with reporting an extramarital affair.

These findings suggest that both demographic, attitudinal, and relational variables are associated with extramarital affairs. Among the variables that individuals can control, adopting a stricter than average definition of cheating, being in a stable relationship, and the personal importance of religion are all related to lower likelihoods of cheating on one’s spouse.

Among the variables that individuals can control, adopting a stricter than average definition of cheating, being in a stable relationship, and the personal importance of religion are all related to lower likelihoods of cheating on one’s spouse.

Jeffrey Dew is an associate professor in the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University, a fellow at the National Marriage Project and a fellow of the Wheatley Institution.

1. The iFidelity Survey was sponsored by the Wheatley Institution at Brigham Young University, the National Marriage Project, and the School of Family Life at Brigham Young University. Jeffrey Dew is a fellow of the Wheatley Institution.

2. The question asked participants if they had ever cheated on a spouse given the definition above. For participants who were married at the time of the survey, we do not know if they are reporting having cheated on a previous spouse or their current spouse.

The lie detector that lies: how stereotypes lead to the condemnation of the innocent

Subscribe to our newsletter "Context": it will help you understand the events.

Image copyright, Getty Images

If you think you can unmistakably recognize a person's lies by how they behave (fussing, averting their eyes, sweating, etc.), then you are mistaken, scientists have proven. There are surer tricks to crack a liar, and these tricks should be urgently adopted by the police and investigators, psychologists emphasize, and the old methods (including the lie detector) should be discarded as false.

What is it like to serve 17 years for a crime you didn't commit, just because it seemed to the investigators and the police that you were behaving somehow suspiciously? Is it any consolation that, along with you, many innocent people are imprisoned in the same way?

It seemed to the police that 17-year-old Marty Tankleff was somehow too calm when his parents were found murdered in a house in New York's Long Island (mother was stabbed to death, father was beaten to death with a bat). The court did not believe in Marty's innocence and sentenced him to 50 years in prison, 17 of which he served before he was acquitted.

In another case, detectives found the opposite behavior suspicious: 16-year-old Jeffrey Deskovich was, in their opinion, too upset and tried too hard to help the investigation when his classmate was found strangled. And he, like Tankleff, was found guilty and sent to prison for life for rape and murder. Only 15 years later, a re-analysis of DNA showed that Jeffrey did not commit a crime.

So one person didn't seem upset enough. The other was too upset. How can completely opposite emotions be a sign of hidden guilt?

They can't, says psychologist Maria Hartwig, a lie researcher (yes, there are scientists) at the City University of New York College of Criminal Law. The two, later acquitted, fell victim to the widespread misconception that a liar can be recognized by the way he behaves.

- Lie theory: how to determine when you are being lied to

- Little daily lies.

Does she help work?

Does she help work? - A world in which it is impossible to lie - is it good or bad?

- The ability to lie, telling the truth - where does it lead the world

In many countries and cultures, it is believed that when a person fusses, looks away, stutters, he is trying to hide something, to deceive.

In fact, over decades of research, scientists have found very little evidence for such a view.

"One of the problems we face as scientists who study human lies is that everyone thinks they know how lies work," says Hartwig, who co-wrote a paper for the Annual Psychological Review on non-verbal cues indicating that the person is lying.

This overconfidence leads to serious miscarriages of justice, as the cases of Tankleff and Deskovich confirm.

"Mistakes in the definition of lies are costly to society and those who have become victims of miscarriage of justice," says Hartwig. "The stakes are very high."

"The stakes are very high."

We rely too much on our intuition, on our experience - in general, on our own lie detector built into us. But he often lies - as, indeed, a real polygraph.

Poke method?

Psychologists have long known how difficult it is to spot a liar. In 2003, Bella DePaulo, now at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and her colleagues reviewed the current scientific literature, finding 116 experiments that compared people's behavior when they were lying and when they were telling the truth.

The studies assessed 102 possible non-verbal cues (regardless of what words were spoken), such as looking away, blinking, raising the voice, shrugging shoulders, changing posture, moving the head, arms and legs.

None of these "signals" reliably signaled that the person was lying.

However, there were a few that, if desired, could be associated with uttered lies - for example, dilated pupils and a slight increase in the tone of the voice, not caught by the human ear.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Telling a liar is not easy

Three years later, DePaulo and psychologist Charles Bond of Texas Christian University reviewed studies of 24,483 observers who assessed the truthfulness of 6,651 communications from 4,435 people.

It turned out that both experts from law enforcement agencies and student volunteers were able to separate lies from the truth only in 54% of cases (slightly more than half). That is, it almost did not differ from the result that can be obtained by the "poke method".

In experiments with individuals, accuracy ranged from 31 to 73%, and the smaller the study, the wider the scatter and the greater the influence of pure luck.

As psychologist and applied data analyst Timothy Luke of the University of Gothenburg, Sweden, says, "If we still haven't found examples of accuracy from extensive research, it's probably because they don't exist. "

"

- Is it possible to fool a lie detector?

- Exercise for the mind: who is telling the truth?

- How to bring a liar to clean water: expert advice

Worldly wisdom seems to suggest that you can identify a liar by the way he talks and moves.

But when scientists tried to find confirmation of this, they found that in fact very few of the signals considered have a connection with lies or truth in words. Even those few of them that seemed to be statistically significant fell short of the level of reliable indicators.

Police experts, however, often put forward a counterargument: those experiments were far from real conditions. After all, they say, volunteers (most often students) tasked with lying or telling the truth in science labs don't have the threatening prospect of consequences that real-crime suspects see during interrogation.

Real conditions? The results are no better

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

When Samantha Mann, a psychologist at the University of Portsmouth, UK, investigated cases of deception 20 years ago, she thought the police experts had something right.

To get to the bottom of the issue, she and her colleague Aldert Wray first looked at many hours of videotaped interrogation of a convicted serial killer and picked three times he was lying and three more times he was telling the truth.

Mann then asked 65 British police officers to rate these six situations and tell him when he was lying and when he wasn't. Since the notes were in Dutch, the police could only judge by non-verbal signs.

Since the notes were in Dutch, the police could only judge by non-verbal signs.

The law enforcers were right 64% of the time—a little higher than chance, but still not accurate enough, says Mann.

The worst performers relied on non-verbal stereotypes such as "liars hide their eyes", "liars fuss".

The killer did not hide his eyes and did not fuss when he lied. "This guy was clearly very nervous," says Mann. But he controlled his behavior and consciously avoided the stereotypical "liar behavior."

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Prejudices about how people behave when they lie lead to miscarriages of justice

the words of family members who killed their relatives but denied it during televised press conferences that depicted mental anguish.Characteristically, the worst results were for those police officers who believed that the suspects' emotions were real.

What does this say? "If a husband killed his wife, there could be many reasons for him to be upset, from remorse to fear of arrest," says Mann. "Non-verbal behavior is very individual. If you focus on non-verbal behaviors like emotions, you'll quickly become confused."

"Non-verbal behavior is very individual. If you focus on non-verbal behaviors like emotions, you'll quickly become confused."

Hartwig and Bond, in their review of research, did not find evidence that in real situations of police investigation, people were able to detect lies better than student volunteers in laboratory conditions.

Ferry experiment

In all of the experiments mentioned - from the serial killer to the lying volunteers - lies were spoken aloud.

In a study published in 2019, Mann set out to test for non-verbal deception, such as when someone tries to cover up illegal behavior (as in cases of smugglers or terrorists trying to smuggle in an explosive device).

Mann invited 52 student volunteers to participate and asked half of them to bring a laptop onto the ferry, which allegedly contained photographs of secret special objects.

Volunteers were asked to blend in with the crowd and try not to look suspicious. They were warned that there would be people on the ferry who would try to figure them out.

They were warned that there would be people on the ferry who would try to figure them out.

The second half of the participants were allowed to carry a regular mobile phone on the ferry and were not instructed to hide their behaviour.

When Mann showed a video of what was happening on the ferry 104 to other volunteers and asked them to point out the "smugglers", the result was again no better than the notorious poke method.

Image copyright Getty Images

Photo caption,The 20th century interrogation technique used in polygraph examinations is notorious for being inaccurate

"Smugglers" later said they were nervous, but tried to behave normally and controlled their nerves with simple tricks - listened music or digging into your smartphone.

Mann then upped the ante. She gave half of the volunteers an envelope with Russian, Egyptian and Korean currencies and asked them to hide it. The second half did not carry anything "illegal".

However, this time Mann sent two investigators onto the ferry and asked them to watch the passengers and pretend they were matching faces with photos on their phones.

And now 120 volunteers who tried to figure out the "smugglers" on the video guessed only 39.2% of the time - far below mere chance.

The reason for this, according to Mann, was that the "smugglers" deliberately tried to look normal, and those volunteers who were not smuggling anything ("innocent"), discovering an unexpected face check by two researchers, were surprised - and this - the reaction was taken as a sign of guilt.

This is what other research lacks, says Florida International University psychologist Ronald Fisher, who is involved in training FBI agents. "Not many studies compare people's inner emotions with what others notice in them," he says. "The fact is that liars, although they are more nervous, hide it and behave in the eyes of observers differently than the stereotypically nervous one. " .

" .

The results of such studies make scientists abandon the search for non-verbal signs of deception. But are there other ways to identify a liar?

Let him talk a little longer

Today, psychologists who work with this topic tend to focus on verbal cues and cues—in particular, how people who lie and those who lie talk differently about the same thing. who is true.

For example, interrogators hold their cards for longer, deliberately letting the suspect speak, which helps to detect contradictions in his words.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Some interrogation techniques help to recall fine details to a suspect or witness

In one experiment, Hartwig taught this interrogation technique to 41 police trainees, and it helped them correctly identify when a person was lying 85% of the time. In comparison, those trainees who had not yet been taught this technique identified a liar only 55% of the time.

Another interrogation technique helps to recall small details: suspects and witnesses are asked to draw the scene of an incident or the location of an alibi. This process activates memory, and those who tell the truth remember more details - in one study as much as 76% more.

The British police regularly use drawing interrogations and collaborate with psychologists to assist in impartial interrogations - in contrast to the accusatory interrogations of the 1980-90s. and caused several scandals with the conviction of the innocent.

Very Slow Change

However, in the US police force, these evidence-based reforms have hardly begun. For example, the Department of Homeland Security's Transportation Security Administration at airports still uses non-verbal cues and cues to screen passengers for interviews.

In a memo to its agents, management lists the same "eyes averted" (considered in some cultures as a mark of respect), quick blinking, too much staring, complaining, whistling, exaggerated yawning, fussy movements, or constant tidying up. Needless to say, all these "signs" are completely debunked and rejected by researchers.

Needless to say, all these "signs" are completely debunked and rejected by researchers.

It is not surprising that the actions of agents armed with such vague and contradictory grounds for suspicion between 2015 and 2018 there were 2,251 official complaints from passengers claiming they were under suspicion only because of race, nationality, ethnicity, and so on.

Despite all the complaints and recommendations from a US congressional committee that conducted its own investigation into the methods of the Transportation Security Administration, they still rely on such, for example, scientifically unsubstantiated signs as profuse sweating.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Interrogators may be nervous for a variety of reasons, not necessarily because they are hiding something

For 11 years, three passengers with explosive devices were prevented from getting on board the plane. But, as Mann points out, without knowing exactly how many intruders managed to get on board undetected, we cannot assess the success of the program.

Indeed, in 2015, the acting head of the Transportation Security Administration was forced to look for a new job after an internal investigation by undercover Homeland Security agents successfully smuggled through airport security 95% of the time fake explosive devices and real weapons.

"Badly flawed methods"

In 2019, Mann, Hartwig and 49 other researchers published a review assessing the accuracy of behavioral analysis. In it, scientists concluded that law enforcement officers should abandon these pseudo-scientific, "fundamentally erroneous" methods that can "harm the lives and freedoms of people."

Meanwhile, Hartwig has partnered with renowned national security expert Mark Fallon to develop a new research-based investigator training program.

"Progress is slow," says Fallon. But he hopes that future reforms will help save people from unfair sentences like those suffered by Jeffrey Deskovich and Marty Tankleff.

As Tankleff's life experience shows, stereotypes stick. The campaign for his rehabilitation lasted for years, his path to the practice of law (already after he was acquitted) was thorny.

This introverted, pedantic man was forced to learn how to show his feelings in order to "create a new image" of the wrongly convicted, says Lonnie Sauri, the crisis manager who helped Tankleff change.

And it worked. In 2020, Tankleff was admitted to the practice of law in New York State.

So why was showing emotion so important? "People," Sauri says, "are very biased."

--

Based on Knowable Magazine and BBC Future.

how genetic companies cheat people and destroy families

was looking for his real mother

Michael Douglas recently moved to southern Maryland, USA. He underwent genetic testing to find out where he came from and to find a family about which he knew very little.

Douglas is now 43 years old. In childhood, he was adopted. He always knew the name of his real mother - Deborah Ann McCarthy and even saw a birth certificate indicating his birth name: Thomas Michael McCarthy. For many years, Douglas tried to find his biological family. He looked up the numbers of her namesakes in the phone books and called them. “I must have ruined a lot of marriages,” he laughs.

But he really started looking for his mother only in the last five years. Michael is struggling with a life-threatening disease - a genetic disease - Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. It is caused by a breakdown in a gene that helps build the body's connective tissue. This disease is characterized by elastic skin and hyperflexible joints. “Three times I was on the verge of life and death,” he says.

“You need to study my DNA to find out who I am.”

“I always had dislocations as a child,” says Douglas. His blood vessels don't constrict properly to maintain blood pressure, so he faints when he gets up. For five years he had a constant migraine. Headaches are common in about a third of people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. In addition, he has B-cell lymphoma. “I feel every day like I have the flu,” he continues. Douglas decided it was time to find his biological family and learn more about his family history.

For five years he had a constant migraine. Headaches are common in about a third of people with Ehlers-Danlos syndrome. In addition, he has B-cell lymphoma. “I feel every day like I have the flu,” he continues. Douglas decided it was time to find his biological family and learn more about his family history.

In June 2017, Douglas flew to Ireland, calling his trip "deadly". Douglas saw the land of his ancestors - McCarthy. He chose Fezard because there is a pub in the walled medieval town called McCarthy (Douglas learned later that he and the owner of the pub are related). His health improved during the trip. True, he considers this a merit of the cold weather in Ireland. When he returned to Phoenix, where his foster family lives, he had a strong desire to find his real parents

"That's it," he decided, "I need to study my DNA to find out who I am." He submitted his DNA analysis to three testing companies: DNA Family Tree, AncestryDNA, and MyHeritage. Thanks to the results of DNA tests and research on genealogical records, Douglas found his biological family in November of last year and dived headlong into a new life.

Thanks to the results of DNA tests and research on genealogical records, Douglas found his biological family in November of last year and dived headlong into a new life.

In February, he moved from Phoenix to Maryland to care for his biological mother, who had recently had a stroke. Relationships were not easy to establish, but Douglas found a common language with one of his two biological brothers. “I have relationships with my relatives that I didn’t know before.” He was glad to know that he looked like his great-grandfather, Thomas Rodd, who made bicycles. Douglas himself is the creator of the Star Wars costumes

Adopted children like Douglas and biological parents often use commercial DNA tests in hopes of reunification, says Drew Smith, genealogy librarian at the University of South Florida at Tampa. Many states prevent obtaining birth certificates or other documents to trace biological families. DNA testing is "the end of the lost paperwork problem," says Smith.

AncestryDNA, the genetic testing service with the largest customer base, has convinced nearly 10 million people to take a DNA test. 23andMe, Living DNA, DNA Family Tree, MyHeritage, National Geographic's Geno 2.0, and others offer customers the use of genetic analysis to connect with both living relatives and ancestors. Several companies are even willing to tell people about their Neanderthal connections. But often such services are not able to tell who you are and where your family is from. Even though they claim otherwise.

23andMe, Living DNA, DNA Family Tree, MyHeritage, National Geographic's Geno 2.0, and others offer customers the use of genetic analysis to connect with both living relatives and ancestors. Several companies are even willing to tell people about their Neanderthal connections. But often such services are not able to tell who you are and where your family is from. Even though they claim otherwise.

False precision

Article author Tina Hesman Sai also tried DNA testing. She learned more about her family: who were her ancestors, and what continent she came from. The results of the study stunned her.

“I tested my DNA specifically for this project. My goal was to investigate the methodology behind DNA testing. But of course, it was a good excuse to learn more about my family.

I already knew a lot about the three branches of my family tree. According to birth and death data, censuses and other documents, most of my family is connected with England and Germany. But I was interested in communication with relatives from the Hungarian side, about whom I knew less. Therefore, I sent saliva and smears of buccal epithelium from the inside of the cheeks to several specialized companies.

But I was interested in communication with relatives from the Hungarian side, about whom I knew less. Therefore, I sent saliva and smears of buccal epithelium from the inside of the cheeks to several specialized companies.

My ethnicity was marked all over the map of Europe. As a rule, these estimates are most accurate on a broad continental scale. All companies agree that my origin is European. But that's where the coincidences end. Even companies that limit their results to the size of the continent gave different answers to my DNA results. National Geographic Geno 2.0 claims that I am 45% from the southwest of Europe. Veritas Genetics gives only 4% of my southwestern European origin and makes sure that mostly (91.1%) my ancestors are from north-central Europe.

Companies that dig into the origin down to the level of a particular country are well aware that their accuracy in the results is reduced. But this does not prevent them from giving too specific assessments. In most reports, the main results are shown at the bottom of the confidence scale. For example, 23andme claims they have 50% statistical confidence in my ethnicity results.

For example, 23andme claims they have 50% statistical confidence in my ethnicity results.

Despite the different methods of the companies, their reports generally did not match what I know about my family tree. 23andMe says I am 16.6% Scandinavian. When I sent the raw data from 23andMe to MyHeritage to do my own analysis, the company didn't report my Scandinavian ancestry at all. They claimed that I was 16.9% Italian. But as far as I know, I have no ancestors from Italy or Scandinavia at all

Only 23andMe found German roots in me, although the company combined them with French. In total, 18.8% came out. Hungarian origin is not indicated in the company's findings. I can only guess that the 23% Eastern European and 0.3% Balkan parts, from 23andMe's point of view, exactly cover this part of my ancestry. Both 23andMe and AncestryDNA concluded that I have Ashkenazi Jewish ancestors. This surprised me.

This surprised me.

Most companies agree that my ancestors are from the British Isles. But even in this case, the estimates differ. According to 23andMe, I am 26.6% British and Irish. According to Living DNA, 60.3% of my DNA is from the UK and Ireland, while MyHeritage has a whopping 78.7% of my DNA.

When I shared these inconsistencies with Deborah Bolnick, an anthropological geneticist at the University of Texas at Austin, I thought I could almost hear her shaking her head in disapproval."

“They provide customers with very specific, precise numbers down to the decimal point. But this is a false precision," Bolnik is sure, "The tests that are available cannot be as nuanced, sensitive and small-scale as they are presented."

“If DNA tests tell you you have a muffin, cream and jam, then you are from the UK”

Ethnicity analysis is based on a method of matching patterns of genetic variants, often referred to as single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs. Your DNA contains SNP patterns with traces of people from certain geographic locations. To confirm that this community represents a given place, companies typically require that people, "reference populations", have four grandparents who were born in that place. Many of the companies use human population DNA samples from large public databases compiled as part of the 1000 Genomes Project, a catalog of the genetic variations of thousands of people around the world. Some companies supplement their bases by testing people in different parts of the world. Thus, reconciliations in control populations differ across companies.

Your DNA contains SNP patterns with traces of people from certain geographic locations. To confirm that this community represents a given place, companies typically require that people, "reference populations", have four grandparents who were born in that place. Many of the companies use human population DNA samples from large public databases compiled as part of the 1000 Genomes Project, a catalog of the genetic variations of thousands of people around the world. Some companies supplement their bases by testing people in different parts of the world. Thus, reconciliations in control populations differ across companies.

To tell customers as broadly as possible which country or part of the country their ancestors called home, companies need to sample hundreds of people in those countries and more sophisticated algorithms to detect small differences in the samples. Considering more than SNPs, Living DNA provides estimates of ethnicity in the sub-regions of the United Kingdom and Ireland. The company analyzes how different sections of DNA are connected to each other, says David Nicholson, co-founder and managing director of the company.

The company analyzes how different sections of DNA are connected to each other, says David Nicholson, co-founder and managing director of the company.

This is vaguely reminiscent of regional differences in how people in the South West of England have a tea party with scones, cream and jam. “In Devon, they start with a bun, then they take cream, and then they start with jam,” says Nicholson. “In Cornwall first the muffins, then the jam and cream, in a different order. Most DNA tests simply tell you that you have a muffin, cream and jam, so you are from the UK.” But as his company also looks at the relationship between DNA elements, Nicholson says the results will tell clients exactly which part of the British Isles was their ancestral home.

“People move around and it makes it harder to find”

Companies are confident in their results because you share DNA samples with people living in specific countries. But your ancestors may not always live where their descendants are,” Bolnick notes. People move around, and this complicates the search.

People move around, and this complicates the search.

For many Americans, some branches of their families are connected with immigration, while other branches are deeply rooted in American soil. Two branches of my family came to Massachusetts and Maryland from England in the 1600s. One line moved from Germany to Nebraska in the late 1800s, and my Hungarian great-grandparents arrived in the US in 1905 year.

Most Americans who get tested are interested in their family history before moving to the US, says geneticist Joe Pickrell, CEO of DNA testing company Gencove. But the answer to their question is not so simple. DNA is a record of thousands of ancestors stretching back from different places on the planet. “How do companies sort time and place in search of a specific ancestor,” Pickrel wonders.

Take the stretch of DNA containing the specific SNP pattern. “Today you will find it in the US and with relatives in England and Germany, but perhaps 500 years ago your common ancestor lived in Italy,” Bolnick explains. After many years, this section of DNA looks like it belongs to ancestors from Romania, Mongolia and Siberia. “When people move, their genes move, they change the ‘geography’ of their ancestors,” she says.

“Today you will find it in the US and with relatives in England and Germany, but perhaps 500 years ago your common ancestor lived in Italy,” Bolnick explains. After many years, this section of DNA looks like it belongs to ancestors from Romania, Mongolia and Siberia. “When people move, their genes move, they change the ‘geography’ of their ancestors,” she says.

With all of my family's moves, I expected a lot more of my ethnicity to come from new immigrants. I thought that my British ancestry would be diluted hundreds of years later in America, but it turned out not to be.

According to Bolnick, people think of their ancestry based on information about individual countries, but genetics change and transcend national boundaries. In fact, these categories are not genetic, they are socio-political and historical.

Smith, in South Florida, agrees: "It's hard to tell French from German by DNA analysis."

Vampire Research

Some groups, including aboriginal populations in Australia and large parts of Africa and Asia, are not in the company's databases. The same applies to Native Americans, whose examples are few. And in some cases, they are collected in dubious ways, says Crystal Tsoxi, a geneticist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

The same applies to Native Americans, whose examples are few. And in some cases, they are collected in dubious ways, says Crystal Tsoxi, a geneticist at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

She talks about "vampire projects": geneticists took blood from the natives, and then disappeared. Some scientists have used their positions to obtain DNA samples from several indigenous peoples. DNA donors did not agree to tests that conflicted with the cultural and religious beliefs of the groups.

In 2002, the Navajo Nation (Dine) (Indigenous people of North America - "Hi-tech"), the tribesmen of Tsosi, announced a moratorium on genetic research. Recently, the tribe again discussed lifting the moratorium, but so far it is still in effect, says Tsosi. “We have been used for so long just as research subjects, lab rats, and not as a partner study,” she says. "The Navajo are still waiting for a conversation that will change the established order and protect our interests. "

"

Distrust of genetic research has led to the fact that there is simply no information about people from 566 tribes recognized in the USA in genetic databases. And those who are interested in their origins do not learn about their tribal heritage from DNA tests. Even if a DNA test determined that a person carried DNA inherited from a Native American ancestor, that would not make the person a member of a tribe, Tsosi argues. Tribal memberships are based on family and community ties, not DNA.

As a volunteer with the Tennessee Native American Association, Tsoshi receives many questions. People learn about Indian roots and want to know if they can consider themselves part of the nation. “It’s not enough to just call yourself a Native American,” she says. “I tell them, study your family tree and document it. Typically, the answer is: oh, that sounds like too much work."

This answer confuses her. “If you know that you are descended from Indians, this part of you is so important that you need to get trained, and documentation in this case is very important,” says Tsoshi. She says she doesn't understand why people are so puzzled by randomly inherited SNP patterns. “Our character, who we are, what we are is a complex story of many non-biological factors. If we limit our individuality to the level of tests, in fact we will ignore the beauty and complexity that is given to each of us.

She says she doesn't understand why people are so puzzled by randomly inherited SNP patterns. “Our character, who we are, what we are is a complex story of many non-biological factors. If we limit our individuality to the level of tests, in fact we will ignore the beauty and complexity that is given to each of us.

Matches and Inaccuracies

When genetic testing clients discover that their DNA does not match the people they thought were their cousins, their assumptions can be the most unkind. So are there any secrets in the family tree? Not necessary.

DNA recombination - the rearrangement of parental chromosome bits in cells as early as the egg or ovum level - creates new genetic combinations, half of which the parent passes on to the child. Siblings will match approximately 50% of their DNA. Recombination means that children do not inherit the same set from their parents (unless they are twins).

This mixing results in relatives who have inherited completely different genetic traits from their ancestors. The more distant the connection, the more likely relatives have no common DNA. About 10% of second cousins (who share the same great-great-grandparents) and 45% of second cousins (descendants of the same great-great-grandparents) don't share DNA, says Drew Smith, genealogy librarian at the University of South Florida at Tampa.

The more distant the connection, the more likely relatives have no common DNA. About 10% of second cousins (who share the same great-great-grandparents) and 45% of second cousins (descendants of the same great-great-grandparents) don't share DNA, says Drew Smith, genealogy librarian at the University of South Florida at Tampa.

"Don't be upset if you have a second cousin and don't match on DNA," he says. "On the other hand, if you have a cousin and you don't have DNA in common, it's very strange."

"Oh my God, I'm royal!"

Advertisements for testing companies promote the link between DNA composition and ethnicity. The AncestryDNA ad shows us Kyle Merker, a real person who grew up thinking he was German. He even danced in German folk groups and wore lederhosen (German leather pants, national costume - "High-tech"). Merker's DNA provided him with data that he was not of German origin at all, he was predominantly of Scottish and Irish blood. And he changed his lederhosen for a kilt.

This commercial makes it look like Mercer has changed his whole worldview and culture because of the DNA test. But even before the tests, he researched his family through newspaper articles and government records. According to Smith, the genealogical resources really gave him a complete picture of his family's history.

“DNA alone is rarely of real value,” continues Smith. "If you're really interested in researching your family, there's a lot of work to be done." He compares the process to advertisements for Home Depot or Lowe's (famous hardware stores in the US - Hi-Tech): "They make it look like, oh my gosh, remodeling a room is easy."

To really verify your lineage, you need to keep track of paper records: birth and death certificates, military forms, immigration records, census forms, church baptisms and marriage records. “DNA is another type of record,” says Smith. "You need to put the puzzle together to learn your story."

“DNA is another type of record,” says Smith. "You need to put the puzzle together to learn your story."

Michael Douglas found his Irish roots. But it took much more information than just a DNA test to unravel the complex tangle of his family ties. Douglas learned that he was from a group of McCarthy descendants in the family tree. According to his Y chromosome, he is a descendant of Donal Gott McCarthy, a 13th-century Irish king. "Oh my God, I'm of royal blood!" he rejoices. The group helped him trace the McCarthy family tree from the 1200s to the 1830s in Cork County, Ireland.

But not all such stories have happy endings. Smith saw how DNA testing destroyed families.

"Through analysis, people will discover things that will surprise them or even alarm them," he says. “You will discover that your father is not actually your own. Or a coincidence with other relatives could reveal family secrets.