What is stimming behavior

Stimming: children & teens with autism

About stimming and autism

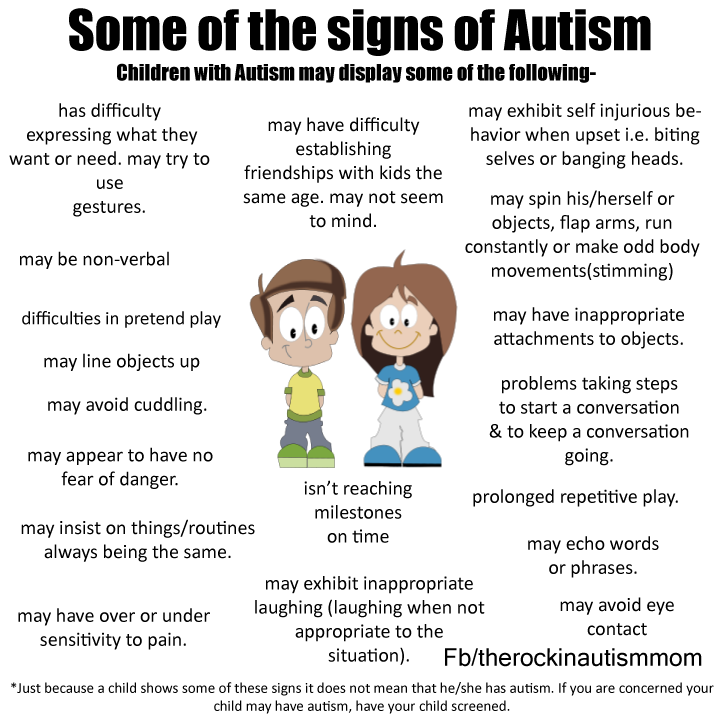

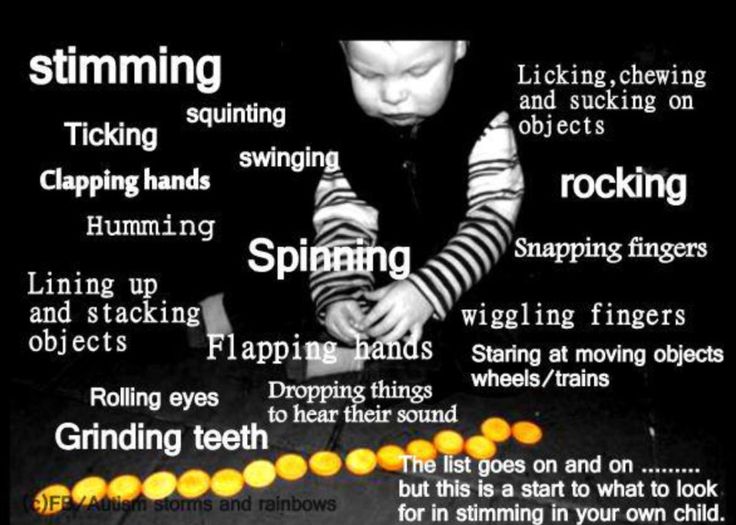

Stimming – or self-stimulatory behaviour – is repetitive or unusual body movement or noises. Stimming might include:

- hand and finger mannerisms – for example, finger-flicking and hand-flapping

- unusual body movements – for example, rocking back and forth while sitting or standing

- posturing – for example, holding hands or fingers out at an angle or arching the back while sitting

- visual stimulation – for example, looking at something sideways, watching an object spin or fluttering fingers near the eyes

- repetitive behaviour – for example, opening and closing doors or flicking switches

- chewing or mouthing objects

- listening to the same song or noise over and over.

Many autistic children and teenagers stim, although stimming varies a lot among children. For example, some children just have mild hand mannerisms, whereas others spend a lot of time stimming. Stimming can also vary depending on the situation. For example, some children stim, or stim more, when they’re feeling stressed or anxious.

Why autistic children and teenagers stim

Stimming seems to help autistic children and teenagers manage emotions like anxiety, anger, fear and excitement. For example, stimming might help them to calm down because it focuses their attention on the stim or produces a calming change in their bodies.

Stimming might also help children manage overwhelming sensory information. For autistic children who are oversensitive to sensory information, stimming can reduce sensory overload because it focuses their attention on just one thing. For autistic children who are undersensitive, stimming can stimulate ‘underactive’ senses.

How stimming affects autistic children and teenagers

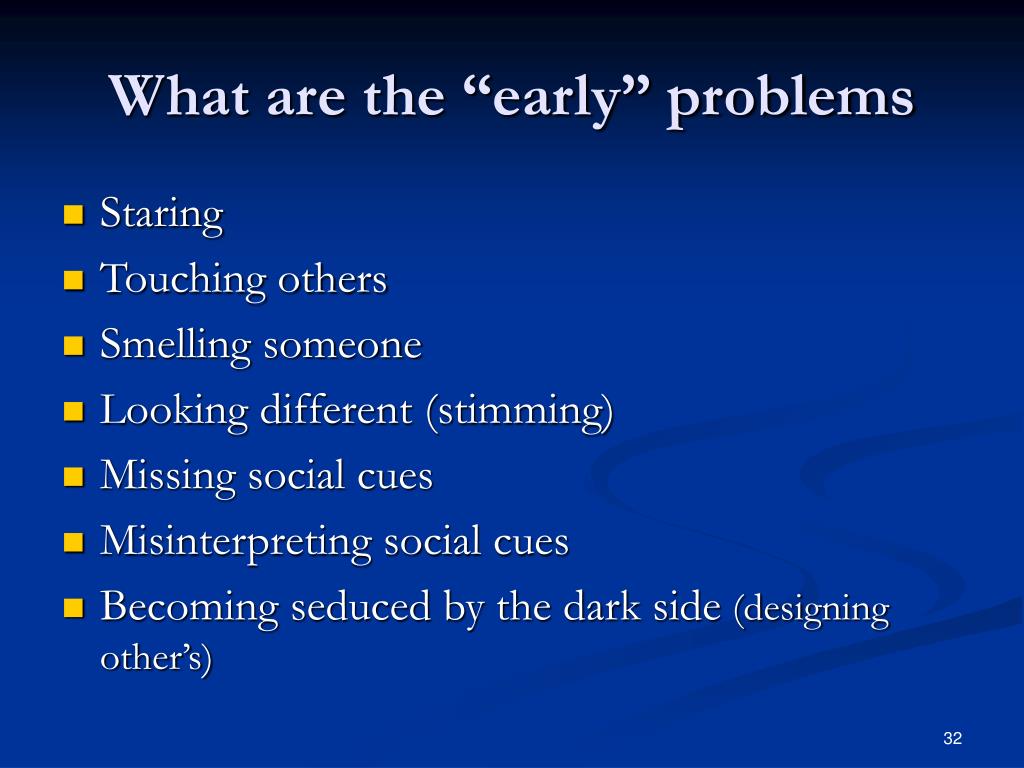

Stimming isn’t necessarily a bad thing, as long as it doesn’t hurt your child. But some stimming can be ‘self-injurious’ – for example, severe hand-biting.

Stimming can also affect your child’s attention to the outside world, which in turn can affect your child’s ability to learn and communicate with others.

For example, if a child flicks their fingers near their eyes, they might not be playing with toys so much and not developing play skills. When the child is older, if they’re absorbed in watching their hands in front of their eyes in the classroom, they’re not engaged with schoolwork. Or if the child is pacing around the fence in the playground, they’re missing valuable social opportunities.

We all use stimming sometimes. For example, some children suck their thumbs or twirl their hair for comfort, and others jiggle their legs while they’re working on a difficult problem or task. You might pace up and down if you’re anxious, or fiddle with a pen in a boring meeting.

Helping autistic children and teenagers with stimming

Many autistic people feel they should be allowed to stim because stimming helps them to manage emotions and overwhelming situations. But if stimming is hurting your child or affecting their learning, social life and so on, it might be best for your child to stim less often.

But if stimming is hurting your child or affecting their learning, social life and so on, it might be best for your child to stim less often.

You might be able to reduce your child’s need to stim by changing the environment or helping your child with anxiety. Also, stimming often reduces as your child develops more skills and finds other ways to deal with sensitivity, understimulation or anxiety.

Changing the environment

If your child finds the environment too stimulating, your child might need a quiet place to go, or just one activity or toy to focus on at a time.

If your child needs more stimulation, your child might benefit from music playing in the background, a variety of toys and textures, or extra playtime outside.

Some schools have sensory rooms for autistic children who need extra stimulation. There might be equipment children can bounce on, swing on or spin around on, materials they can squish their hands into, and visually stimulating toys.

Working on anxiety

If you watch when and how much your child is stimming, you might be able to work out whether the stimming is happening because your child is anxious. Then you can look at your child’s anxiety and change the environment to reduce their anxiety.

For example, is there something new or changed in your child’s environment? Preparing your child for new situations and teaching your child new skills to deal with things that cause the anxiety can reduce stimming.

Where to go for help with stimming

Occupational therapists can help you look at environmental adjustments to support your child.

If your child’s behaviour is causing your child harm or hurting other people, speak to your child’s GP, paediatrician, psychologist, another health professional working with your child, or school support staff.

There are therapies and supports that can help with stimming if that’s what your child needs. These therapies and supports are listed in our Parent Guide to Therapies. Each guide gives an overview of the therapy, what research says about it, and the approximate time and costs involved in using it.

Each guide gives an overview of the therapy, what research says about it, and the approximate time and costs involved in using it.

Why It Happens and How to Manage It

Stimming refers to the natural behavior of self-stimulation. It may include nail biting, drumming your fingers on a surface, or full body movements like rocking or swaying.

What is stimming?

The word “stimming” refers to self-stimulating behaviors, usually involving repetitive movements or sounds.

Everybody stims in some way. It’s not always clear to others.

Stimming is part of the diagnostic criteria for autism. That’s not because stimming is always related to autism. It’s because stimming in autistic people can get out of control and cause problems.

Stimming isn’t necessarily a bad thing that needs to be stifled. But it should be addressed when it’s disruptive to others and interferes with quality of life.

Continue reading to learn more about stimming, when it requires management, and where to get help.

Almost everyone engages in some form of self-stimulating behavior. You might bite your nails or twirl your hair around your fingers when you’re bored, nervous, or need to relieve tension.

Stimming can become such a habit that you’re not even aware you’re doing it. For most people, it’s a harmless behavior. You recognize when and where it’s inappropriate.

For example, if you’ve been drumming your fingers on your desk for 20 minutes, you take social cues that you’re irritating others and choose to stop.

In autistic people, stimming might be more obvious. For example, it may present as full-body rocking back and forth, twirling, or flapping the hands. It can also go on for long periods. Often, the individual has less social awareness that the behavior might be disruptive to others.

Stimming associated with autism isn’t always cause for concern.

It only becomes an issue if it interferes with learning, results in social exclusion, or is destructive. In some rare cases, it can be dangerous.

Common stimming behaviors include:

- biting your fingernails

- twirling your hair around your fingers

- cracking your knuckles or other joints

- drumming your fingers

- tapping your pencil

- jiggling your foot

- whistling

In an autistic person, stimming might involve:

- rocking

- flapping hands or flicking or snapping fingers

- bouncing, jumping, or twirling

- pacing or walking on tiptoes

- pulling hair

- repeating words or phrases

- rubbing the skin or scratching

- repetitive blinking

- staring at lights or rotating objects such as ceiling fans

- licking, rubbing, or stroking particular types of objects

- sniffing at people or objects

- rearranging objects

An autistic child may spend hours on end arranging toys instead of playing with them. Repetitive behavior may also involve obsessions or preoccupations with certain objects or the reciting of intricate details of a particular subject matter.

Other repetitive behaviors can cause physical harm. These behaviors include:

- head banging

- punching or biting

- excessive rubbing or scratching at skin

- picking at scabs or sores

- swallowing dangerous items

With or without autism, there’s a lot of variation in how often stimming occurs from person to person.

You might crack your knuckles only when you’re particularly stressed, or you may engage in this behavior multiple times a day.

For some autistic people, stimming can become an everyday occurrence. It may be difficult to stop. It can continue for hours at a time.

It’s not always easy to determine the reason for stimming. It’s a coping mechanism that can serve a variety of purposes.

For example, an autistic person may be trying to:

- stimulate the senses or decrease sensory overload

- adapt to an unfamiliar environment

- reduce anxiety and calm themselves

- express frustration, especially if they have trouble communicating effectively

- avoid certain activities or expectations

If previous episodes of stimming resulted in wanted attention, stimming may become a way to continue getting attention.

A behavior specialist or therapist with autism experience can help you understand the reasons for stimming behavior.

In some cases, stimming is an attempt to ease pain or other physical discomfort. It’s also important to determine if what appears to be stimming is actually involuntary due to a medical condition, such as seizures.

If you suspect a medical problem, see your doctor right away.

Stimming doesn’t necessarily need to be controlled unless it’s causing a problem.

Management may be needed if you answer “yes” to any of these questions:

- Has stimming caused social isolation?

- Is stimming disruptive at school?

- Does stimming affect the ability to learn?

- Does stimming cause problems for other family members?

- Is stimming destructive or dangerous?

If you or your child is in danger of self-harm, contact your doctor right away. A physical examination and evaluation may reveal existing injuries.

Otherwise, it may be better to manage stimming rather than attempt to completely control it. When working with children, the goal should be to encourage self-control. It shouldn’t be to control them.

When working with children, the goal should be to encourage self-control. It shouldn’t be to control them.

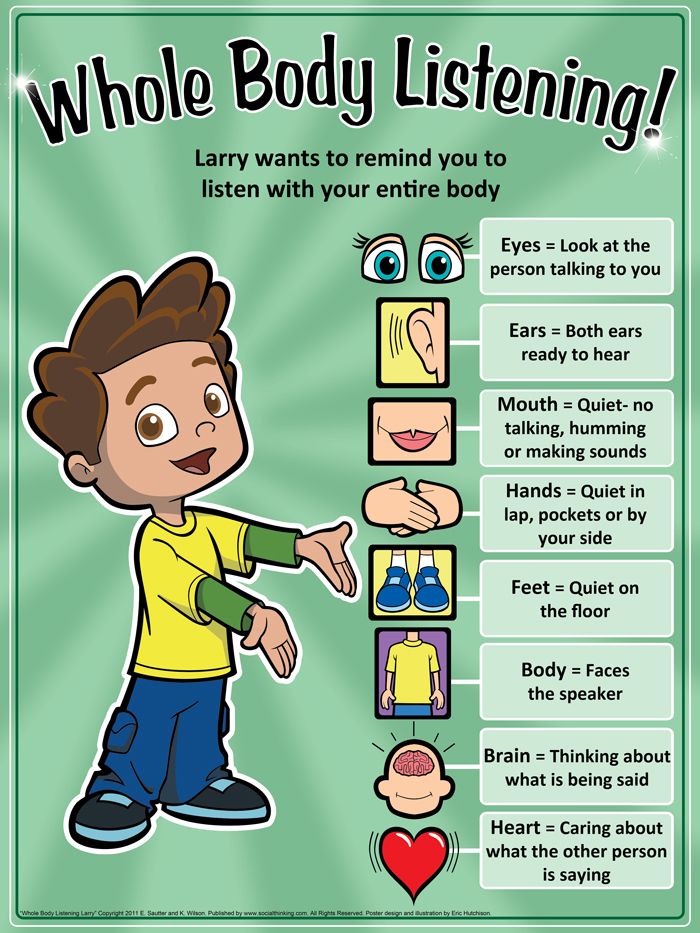

It’s easier to manage stimming if you can figure out the reason behind it. Behavior is a form of communication. Understanding what the person with stimming is trying to say is important.

Evaluate the situation just before stimming starts. What appears to be triggering the behavior? What happens?

Keep the following in mind:

- Do what you can to eliminate or reduce the trigger, lower stress, and provide a calming environment.

- Try to stick to a routine for daily tasks.

- Encourage acceptable behaviors and self-control.

- Avoid punishing the behavior. This action isn’t recommended. If you stop one stimming behavior without addressing the reasons behind it, it’s likely to be replaced with another, which may not be better.

- Teach an alternate behavior that helps to meet the same needs. For example, hand flapping can be replaced with squeezing a stress ball or other fine motor activity.

Consider working with a behavior or other autism specialist. They can evaluate you or your child to determine the reasons behind the stimming.

Once the cause is known, they can make recommendations on the best ways to manage the behavior.

Recommendations may include:

- intervening during any unsafe behavior

- knowing when not to respond

- advising other family members on how they can help

- reinforcing acceptable behavior

- creating a safe environment

- suggesting alternate activities that provide the desired effect

- teaching self-management tools

- working with occupational therapists, educators, and the educational system

- seeking medical help when needed

Stimming behaviors can come and go according to circumstances. Sometimes they get better as a child matures, but they can also become worse during stressful times.

It takes patience and understanding, but many autistic people can learn to manage stimming.

Over time, achieving self-control can improve life at school, at work, and in social situations.

Repetitive behavior ("stimming") from the point of view of an adult with autism

05/10/20

A woman on the autism spectrum about her personal experience of "stimming" (stereotypes, repetitive behavior), its pros, cons and possible approaches

Author: Holli Clauser / Holli Clauser

Source: The Mighty

completely wrapped in it. It was a knitted blanket with green, yellow and white squares. I ran under it from the skirmish of my brothers and sisters, from the barking of dogs, from the screams of my parents. And I disconnected from the outside world, counting the squares and rubbing them with my fingers. This calmed me down. It was my soft, familiar, and Tide-smelling place. Now I am 42 years old. This "nanny" usually lies in the corner of my bedroom, but she can no longer protect me.

I had "fidgets" and "spinners" before it became fashionable

"Why are you spinning all the time" - I heard this statement throughout my childhood. I often needed to distract myself and focus on something else to deal with negative emotions. It helped me calm my anxiety in social situations, kept me occupied if others were too emotional, and helped me focus on the task when I was doing my homework.

As an adult, I learned that these repetitive movements were my defense mechanism. They helped me distance myself from a reality that was too difficult or complex. Then I became a tutor in an offline class for children with autism, where I worked with an autistic girl one on one, and only there I realized that "stimming" is not "fidgeting", and what I was doing was stimming.

Key feature of autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

“Stimming” is a slang term for “self-stimulating behavior”. In most cases, this behavior is a symptom of autism. And very often this is the first or only sign of autism that strangers notice. At its core, stimming is a way of self-regulation of one's condition.

At its core, stimming is a way of self-regulation of one's condition.

Examples of stimming

- Any repetitive "pointless" movement: walking back and forth, circling in place, rocking the torso, twisting objects in the arms, jumping, and so on.

- Immersion in repetitive thoughts or fantasies.

- Repetitive movements of the eyebrows, blinking.

- Shaking hands, moving fingers in front of eyes.

- Line up toys, unwind toys.

- Repetitive fingering of one's hair.

- Repeated repetition of certain sounds, words or previously heard phrases.

- Complete and prolonged concentration on a single interest or topic.

- Unusual or inappropriate sniffing of objects.

- Repeated pressing of palms to ears.

Perhaps by the end of the list you are thinking, “Do I have autism? Because I do some of it." I do not know the answer to this question, and, in any case, I am not qualified to make diagnoses. But wait with self-diagnosis - repetitive movements are very common among all people. We all know those who twirl their hair around their fingers, chew on pen caps, and tap their feet when they think. The difference between people with autism is not in the very presence of such movements, but in their volume, frequency and need for such behavior. Below I will explain this in more detail using the example of my own stimming.

We all know those who twirl their hair around their fingers, chew on pen caps, and tap their feet when they think. The difference between people with autism is not in the very presence of such movements, but in their volume, frequency and need for such behavior. Below I will explain this in more detail using the example of my own stimming.

No, not "we're all a little autistic"

One of the most annoying reactions when people hear that I have autism is, "Well, we're all a bit on the autism spectrum." In my experience, two categories of people answer this way - autism-ignorant people and undiagnosed autistic people.

Some people still deny that I've been correctly diagnosed with autism, but I think these people just don't know what autism is, and they don't know me very well.

What is stimming for me

I constantly put my fingers in my ears and move them until they bleed. I noticed that I do it from overload, nervousness and strong thoughtfulness. As a rule, I let my hair down because it partially blocks access to the ears. Or loved ones remind me to stop.

As a rule, I let my hair down because it partially blocks access to the ears. Or loved ones remind me to stop.

To some extent, yes, I can control my stimming. But it's like trying not to scratch a mosquito bite - it's about as hard for me to suppress the urge to stim. The moment I do this, it feels great, but I may regret it later when I can't put my ear on the pillow.

Can this be fixed?

I was more or less able to replace stimming in public with alternative behavior. During meetings, I keep my hands under the table, which allows me to rub my fingers together or fiddle with a piece of cloth in my hands. If I'm worried or bored, I use scrolling on my phone as a repetitive motion. It looks like I'm looking for something or looking, but really I'm just scrolling. From time to time when I do this, I say some random word, I repeat it for a while, and then I keep scrolling. Saying words like sketchy, loyalty, and commitment out loud gives me more pleasure than you might think.

Do I benefit from stimming?

Stimming has helped me many times. For example, my "stuck" on topics related to my interests, which also applies to repetitive behavior. It has been very helpful at work. If a work task attracts me, then I develop a fixation on it. For example, if I'm in HR, I'll read every HR article I can, listen to podcasts, read other people's resumes online, until I exceed my management's expectations.

However, I can do all this through sleep, family, self-care, and housework. In a way, this may make me a good employee, but I need something else to motivate me, because if my thirst for knowledge is satiated, I will lose motivation. I am currently working on the skills to manage my own behavior. And I've noticed that when I'm less "obsessed" with a topic, I become more creative.

In summary: Yes, stimming can be beneficial. But it is important to learn to control it.

Worry or not

Stimming doesn't necessarily need to be corrected in my opinion.

Intervention is needed if:

- Stimming prevents a person from functioning in society (going to school, working, attending social events, socializing with friends, etc.).

- Causes physical harm (my poor bloody ears) or harms other people.

- Interferes with sleep, eating or daily hygiene.

Do NOT intervene and interrupt stimming because:

– These movements confuse other people.

- These movements irritate other people.

- Others may think that this is not "normal".

If you need help

If you think you or your child needs help with stimming, see a trained professional. First of all, these are certified behavioral analysts with experience in working with self-stimulating behavior in autism.

Warning: Not all behavioral analysts are the same

In every profession, there are people who are not right for you and others who are qualified to suit your needs. Study detailed information, ask about the experience of other people with this or that specialist, before deciding to start therapy. Ultimately, you will need to make up your mind and, of course, be prepared to work hard.

Ultimately, you will need to make up your mind and, of course, be prepared to work hard.

See also:

Why children with autism use stimming

Is it necessary to deal with self-stimulation in a child with autism?

We hope that the information on our website will be useful or interesting for you. You can support people with autism in Russia and contribute to the work of the Foundation by clicking on the "Help" button.

First Person, Sensory and Motor

How people with autism feel when stimmed (stereotyping)

11/21/20

11 autistic people explain their experiences with repetitive movements and actions

Source: The Mighty

Stimming (self-stimulating behavior, stereotypes) are different types of repetitive behavior. Temple Grandin explains in his post that this behavior allows you to cope with sensory overload from the environment or reduce high levels of anxiety. Typical examples of stimming are rocking, circling in place, aimless walking, repeating single words, shaking hands or fingers.

Typical examples of stimming are rocking, circling in place, aimless walking, repeating single words, shaking hands or fingers.

Motor stereotypies are not unique to autistic people, but in autism stims are often unusual, more obvious, and attention-grabbing. It is difficult for many to understand why a person repeats the same aimless movement.

We asked several people with autism to explain what stimming means to them. Here's what they said:

"It helps my body regulate sensory information from the outside world" - Laura Ivanova-Smith.

“You know, when something is being cooked on the stove, sometimes the lid of the pot is moved a little to release the steam? Or how is a bleeding wound tightly bandaged to stop or at least reduce the bleeding? For me, stimming is such a relief, a way to blow off steam - it does not allow me to explode because of the processes taking place inside. Well, or you can say that this is an external action that helps me leave energy inside to normalize the internal state, ”- Paula Gomez.

“Stimming is like turning off the radio because you think you smell something burnt. It's a way of "turning off" the other senses to ensure nothing is on fire." - Lamar Hardwick

“Sometimes if I feel overwhelmed, frustrated or angry, I need to let it out. From overstimulation, I can not sit still, I need to move and make sounds. This is the only way that allows me to somehow cope. This calms me down. As a rule, I start mooing loudly under my breath (sometimes I stop or cover my ears while doing this), and most often I hit something hard with my foot. It's involuntary, so I'm not always even aware that I'm moving my leg. It worries some people, but there's nothing I can do about it." - Sidney Brown

“What do you feel while stimming? You tell me. Most non-autistic people tap their feet, fingertips, or sigh loudly. These are all natural forms of self-expression. The theory behind autistic stimming is the same – they just correct us because our self-expression is more visible than yours!” — Chris Bonello.