What causes people to become bipolar

Bipolar disorder - Symptoms and causes

Overview

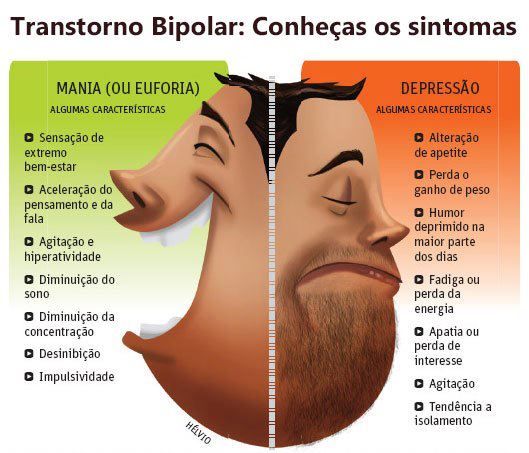

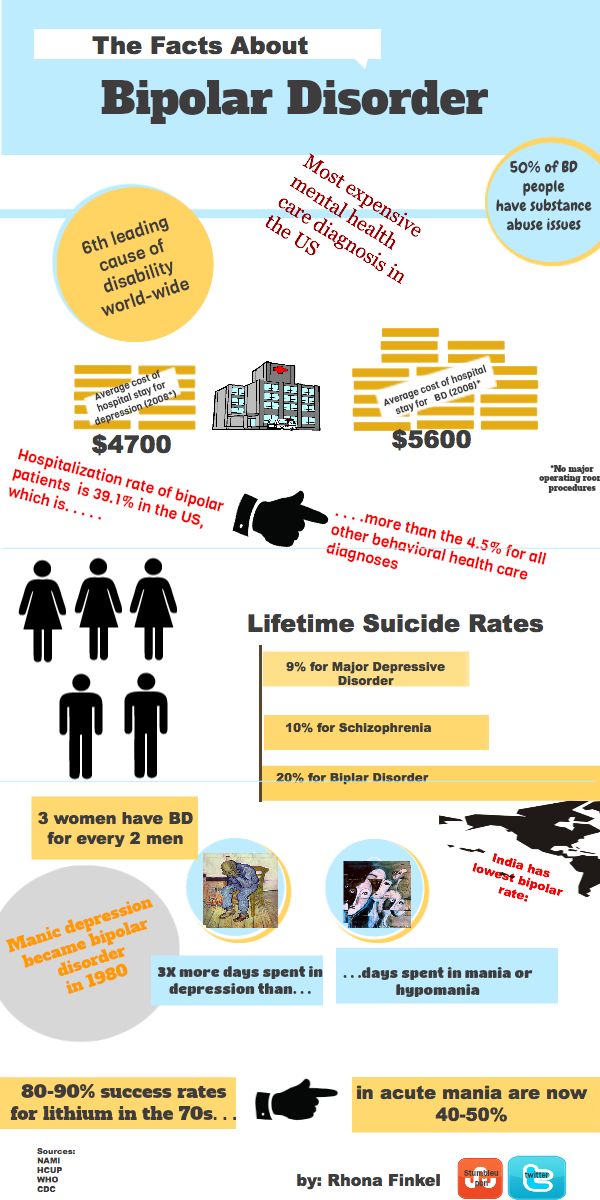

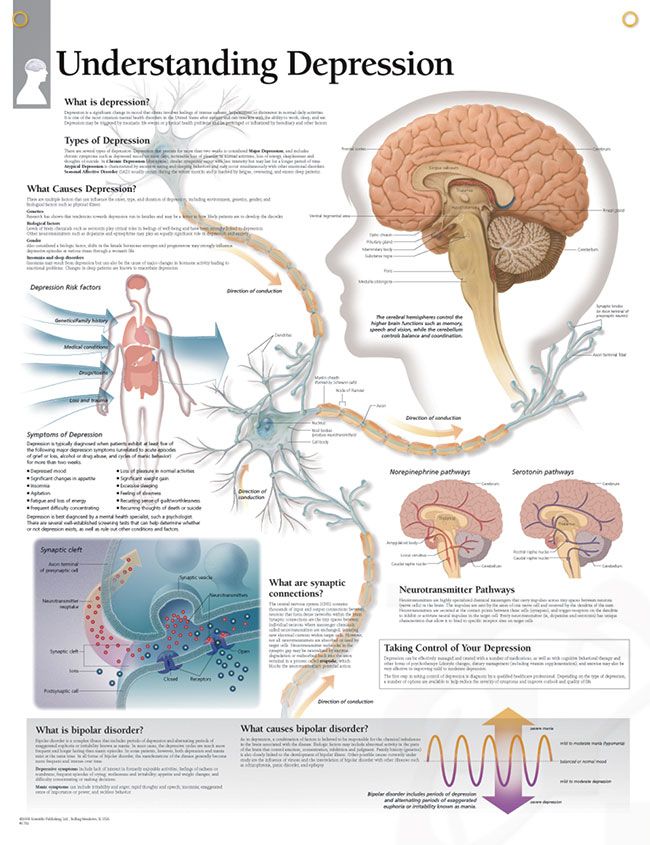

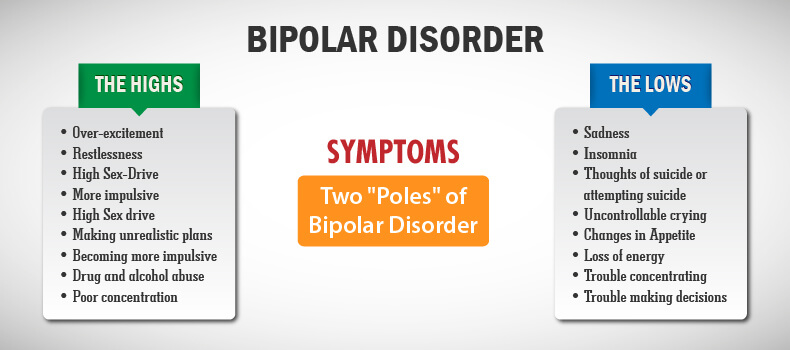

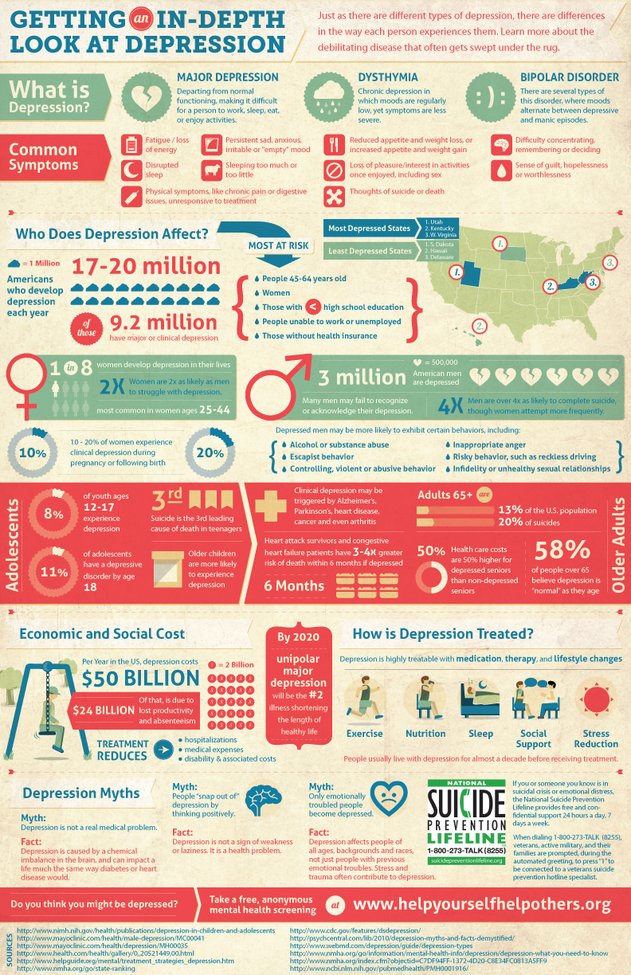

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression).

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When your mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, activity, judgment, behavior and the ability to think clearly.

Episodes of mood swings may occur rarely or multiple times a year. While most people will experience some emotional symptoms between episodes, some may not experience any.

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medications and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Bipolar disorder care at Mayo Clinic

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Symptoms

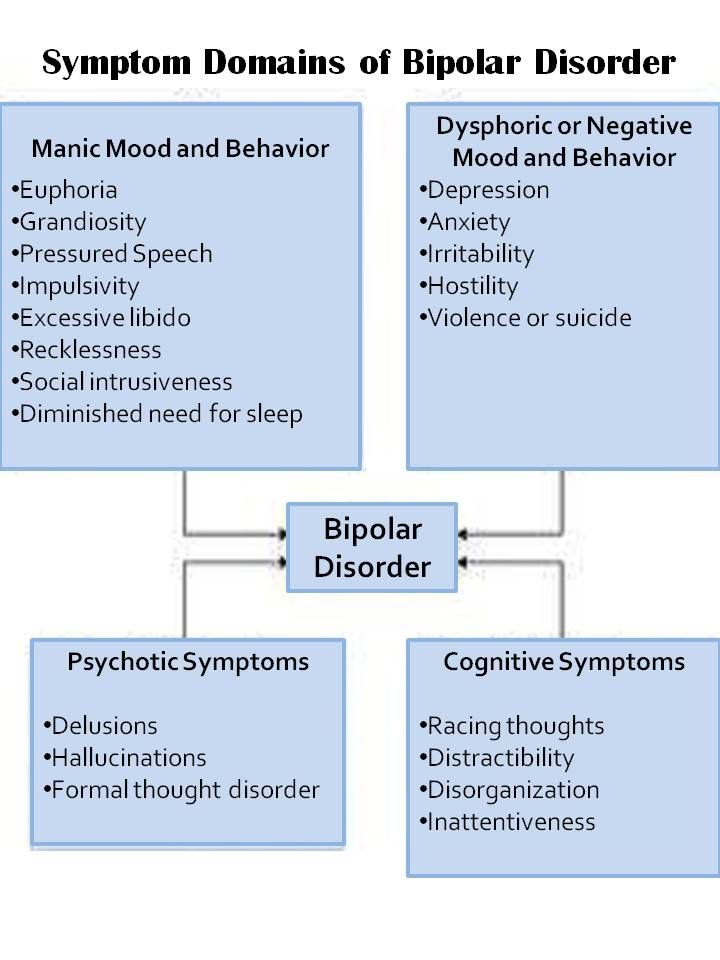

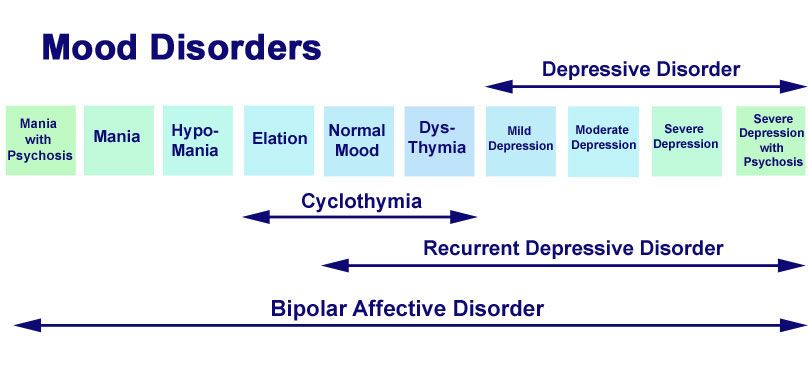

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. They may include mania or hypomania and depression. Symptoms can cause unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, resulting in significant distress and difficulty in life.

- Bipolar I disorder. You've had at least one manic episode that may be preceded or followed by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania may trigger a break from reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar II disorder. You've had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but you've never had a manic episode.

- Cyclothymic disorder. You've had at least two years — or one year in children and teenagers — of many periods of hypomania symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders induced by certain drugs or alcohol or due to a medical condition, such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis or stroke.

Bipolar II disorder is not a milder form of bipolar I disorder, but a separate diagnosis. While the manic episodes of bipolar I disorder can be severe and dangerous, individuals with bipolar II disorder can be depressed for longer periods, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, typically it's diagnosed in the teenage years or early 20s. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms may vary over time.

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two distinct types of episodes, but they have the same symptoms. Mania is more severe than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania may also trigger a break from reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally upbeat, jumpy or wired

- Increased activity, energy or agitation

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Decreased need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Racing thoughts

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making — for example, going on buying sprees, taking sexual risks or making foolish investments

Major depressive episode

A major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in day-to-day activities, such as work, school, social activities or relationships. An episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless or tearful (in children and teens, depressed mood can appear as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling no pleasure in all — or almost all — activities

- Significant weight loss when not dieting, weight gain, or decrease or increase in appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected can be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either restlessness or slowed behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking about, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorders may include other features, such as anxious distress, melancholy, psychosis or others. The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic labels such as mixed or rapid cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or change with the seasons.

The timing of symptoms may include diagnostic labels such as mixed or rapid cycling. In addition, bipolar symptoms may occur during pregnancy or change with the seasons.

Symptoms in children and teens

Symptoms of bipolar disorder can be difficult to identify in children and teens. It's often hard to tell whether these are normal ups and downs, the results of stress or trauma, or signs of a mental health problem other than bipolar disorder.

Children and teens may have distinct major depressive or manic or hypomanic episodes, but the pattern can vary from that of adults with bipolar disorder. And moods can rapidly shift during episodes. Some children may have periods without mood symptoms between episodes.

The most prominent signs of bipolar disorder in children and teenagers may include severe mood swings that are different from their usual mood swings.

When to see a doctor

Despite the mood extremes, people with bipolar disorder often don't recognize how much their emotional instability disrupts their lives and the lives of their loved ones and don't get the treatment they need.

And if you're like some people with bipolar disorder, you may enjoy the feelings of euphoria and cycles of being more productive. However, this euphoria is always followed by an emotional crash that can leave you depressed, worn out — and perhaps in financial, legal or relationship trouble.

If you have any symptoms of depression or mania, see your doctor or mental health professional. Bipolar disorder doesn't get better on its own. Getting treatment from a mental health professional with experience in bipolar disorder can help you get your symptoms under control.

When to get emergency help

Suicidal thoughts and behavior are common among people with bipolar disorder. If you have thoughts of hurting yourself, call 911 or your local emergency number immediately, go to an emergency room, or confide in a trusted relative or friend. Or call a suicide hotline number — in the United States, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (1-800-273-8255).

If you have a loved one who is in danger of suicide or has made a suicide attempt, make sure someone stays with that person. Call 911 or your local emergency number immediately. Or, if you think you can do so safely, take the person to the nearest hospital emergency room.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which

information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with

other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could

include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected

health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health

information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of

privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on

the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Causes

The exact cause of bipolar disorder is unknown, but several factors may be involved, such as:

- Biological differences. People with bipolar disorder appear to have physical changes in their brains. The significance of these changes is still uncertain but may eventually help pinpoint causes.

- Genetics. Bipolar disorder is more common in people who have a first-degree relative, such as a sibling or parent, with the condition. Researchers are trying to find genes that may be involved in causing bipolar disorder.

Risk factors

Factors that may increase the risk of developing bipolar disorder or act as a trigger for the first episode include:

- Having a first-degree relative, such as a parent or sibling, with bipolar disorder

- Periods of high stress, such as the death of a loved one or other traumatic event

- Drug or alcohol abuse

Complications

Left untreated, bipolar disorder can result in serious problems that affect every area of your life, such as:

- Problems related to drug and alcohol use

- Suicide or suicide attempts

- Legal or financial problems

- Damaged relationships

- Poor work or school performance

Co-occurring conditions

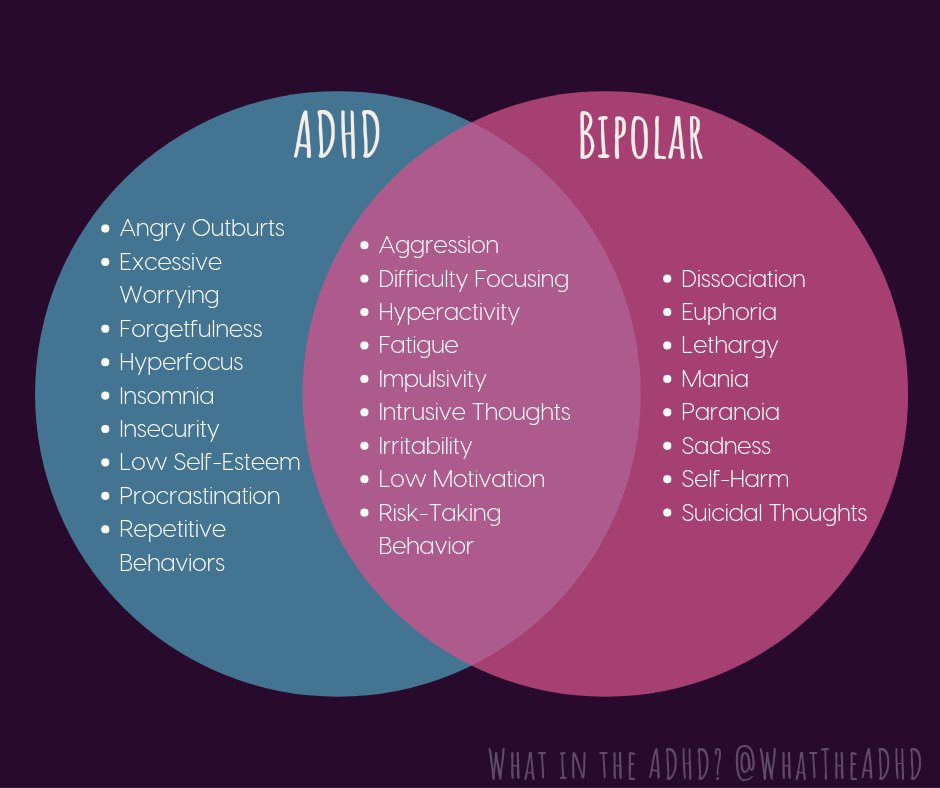

If you have bipolar disorder, you may also have another health condition that needs to be treated along with bipolar disorder. Some conditions can worsen bipolar disorder symptoms or make treatment less successful. Examples include:

Some conditions can worsen bipolar disorder symptoms or make treatment less successful. Examples include:

- Anxiety disorders

- Eating disorders

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Alcohol or drug problems

- Physical health problems, such as heart disease, thyroid problems, headaches or obesity

More Information

- Bipolar disorder care at Mayo Clinic

- Bipolar disorder and alcoholism: Are they related?

Prevention

There's no sure way to prevent bipolar disorder. However, getting treatment at the earliest sign of a mental health disorder can help prevent bipolar disorder or other mental health conditions from worsening.

If you've been diagnosed with bipolar disorder, some strategies can help prevent minor symptoms from becoming full-blown episodes of mania or depression:

- Pay attention to warning signs. Addressing symptoms early on can prevent episodes from getting worse.

You may have identified a pattern to your bipolar episodes and what triggers them. Call your doctor if you feel you're falling into an episode of depression or mania. Involve family members or friends in watching for warning signs.

You may have identified a pattern to your bipolar episodes and what triggers them. Call your doctor if you feel you're falling into an episode of depression or mania. Involve family members or friends in watching for warning signs. - Avoid drugs and alcohol. Using alcohol or recreational drugs can worsen your symptoms and make them more likely to come back.

- Take your medications exactly as directed. You may be tempted to stop treatment — but don't. Stopping your medication or reducing your dose on your own may cause withdrawal effects or your symptoms may worsen or return.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

NIMH » Bipolar Disorder

Do you have periods of time when you feel unusually “up” (happy and outgoing, or irritable), but other periods when you feel “down” (unusually sad or anxious)? During the “up” periods, do you have increased energy or activity and feel a decreased need for sleep, while during the “down” times you have low energy, hopelessness, and sometimes suicidal thoughts? Do these symptoms of fluctuating mood and energy levels cause you distress or affect your daily functioning? Some people with these symptoms have a lifelong but treatable mental illness called bipolar disorder.

What is bipolar disorder?

Bipolar disorder is a mental illness that can be chronic (persistent or constantly reoccurring) or episodic (occurring occasionally and at irregular intervals). People sometimes refer to bipolar disorder with the older terms “manic-depressive disorder” or “manic depression.”

Everyone experiences normal ups and downs, but with bipolar disorder, the range of mood changes can be extreme. People with the disorder have manic episodes, or unusually elevated moods in which the individual might feel very happy, irritable, or “up,” with a marked increase in activity level. They might also have depressive episodes, in which they feel sad, indifferent, or hopeless, combined with a very low activity level. Some people have hypomanic episodes, which are like manic episodes, but not severe enough to cause marked impairment in social or occupational functioning or require hospitalization.

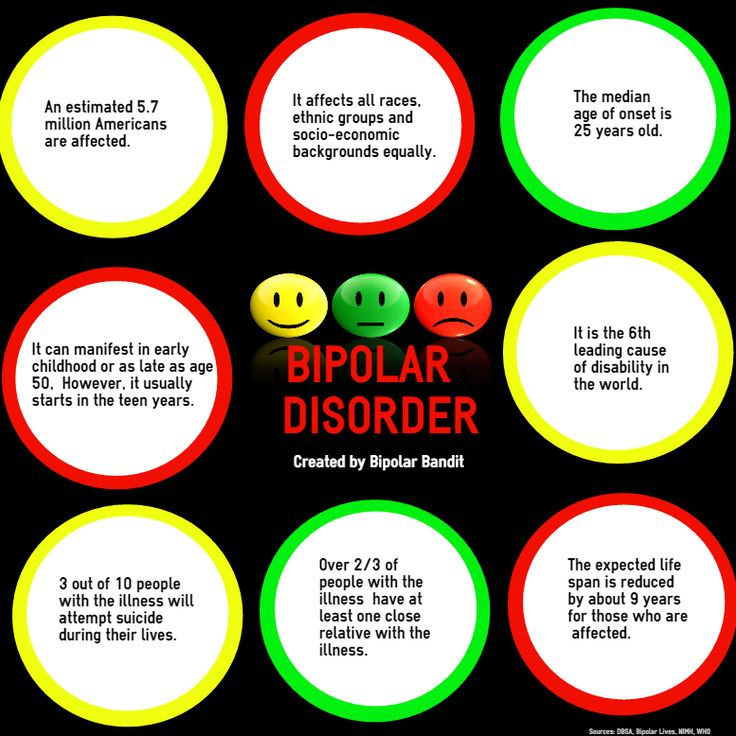

Most of the time, bipolar disorder symptoms start during late adolescence or early adulthood. Occasionally, children may experience bipolar disorder symptoms. Although symptoms may come and go, bipolar disorder usually requires lifelong treatment and does not go away on its own. Bipolar disorder can be an important factor in suicide, job loss, ability to function, and family discord. However, proper treatment can lead to better functioning and improved quality of life.

Occasionally, children may experience bipolar disorder symptoms. Although symptoms may come and go, bipolar disorder usually requires lifelong treatment and does not go away on its own. Bipolar disorder can be an important factor in suicide, job loss, ability to function, and family discord. However, proper treatment can lead to better functioning and improved quality of life.

What are the symptoms of bipolar disorder?

Symptoms of bipolar disorder can vary. An individual with the disorder may have manic episodes, depressive episodes, or “mixed” episodes. A mixed episode has both manic and depressive symptoms. These mood episodes cause symptoms that last a week or two, or sometimes longer. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day. Feelings are intense and happen with changes in behavior, energy levels, or activity levels that are noticeable to others. In between episodes, mood usually returns to a healthy baseline. But in many cases, without adequate treatment, episodes occur more frequently as time goes on.

But in many cases, without adequate treatment, episodes occur more frequently as time goes on.

| Symptoms of a Manic Episode | Symptoms of a Depressive Episode |

|---|---|

| Feeling very up, high, elated, or extremely irritable or touchy | Feeling very down or sad, or anxious |

| Feeling jumpy or wired, more active than usual | Feeling slowed down or restless |

| Racing thoughts | Trouble concentrating or making decisions |

| Decreased need for sleep | Trouble falling asleep, waking up too early, or sleeping too much |

| Talking fast about a lot of different things (“flight of ideas”) | Talking very slowly, feeling unable to find anything to say, or forgetting a lot |

| Excessive appetite for food, drinking, sex, or other pleasurable activities | Lack of interest in almost all activities |

| Feeling able to do many things at once without getting tired | Unable to do even simple things |

| Feeling unusually important, talented, or powerful | Feeling hopeless or worthless, or thinking about death or suicide |

Some people with bipolar disorder may have milder symptoms than others. For example, hypomanic episodes may make an individual feel very good and productive; they may not feel like anything is wrong. However, family and friends may notice the mood swings and changes in activity levels as unusual behavior, and depressive episodes may follow hypomanic episodes.

For example, hypomanic episodes may make an individual feel very good and productive; they may not feel like anything is wrong. However, family and friends may notice the mood swings and changes in activity levels as unusual behavior, and depressive episodes may follow hypomanic episodes.

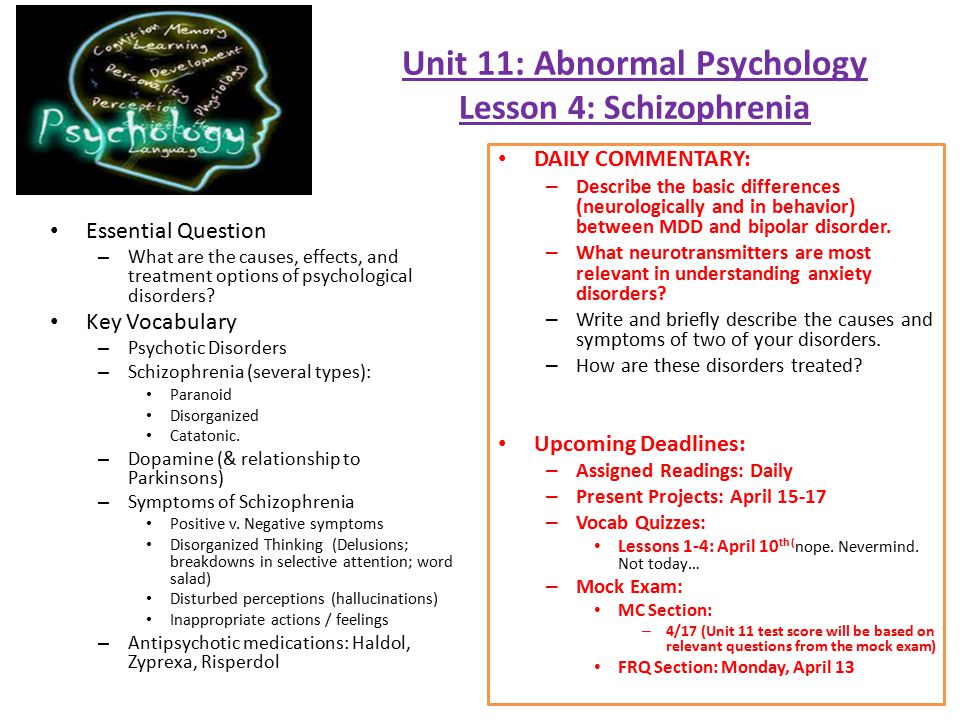

Types of Bipolar Disorder

People are diagnosed with three basic types of bipolar disorder that involve clear changes in mood, energy, and activity levels. These moods range from manic episodes to depressive episodes.

- Bipolar I disorder is defined by manic episodes that last at least 7 days (most of the day, nearly every day) or when manic symptoms are so severe that hospital care is needed. Usually, separate depressive episodes occur as well, typically lasting at least 2 weeks. Episodes of mood disturbance with mixed features are also possible. The experience of four or more episodes of mania or depression within a year is termed “rapid cycling.”

- Bipolar II disorder is defined by a pattern of depressive and hypomanic episodes, but the episodes are less severe than the manic episodes in bipolar I disorder.

- Cyclothymic disorder (also called cyclothymia) is defined by recurrent hypomanic and depressive symptoms that are not intense enough or do not last long enough to qualify as hypomanic or depressive episodes.

“Other specified and unspecified bipolar and related disorders” is a diagnosis that refers to bipolar disorder symptoms that do not match the three major types of bipolar disorder outlined above.

What causes bipolar disorder?

The exact cause of bipolar disorder is unknown. However, research suggests that a combination of factors may contribute to the illness.

Genes

Bipolar disorder often runs in families, and research suggests this is mostly explained by heredity—people with certain genes are more likely to develop bipolar disorder than others. Many genes are involved, and no one gene can cause the disorder.

But genes are not the only factor. Studies of identical twins have shown that one twin can develop bipolar disorder while the other does not. Though people with a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder are more likely to develop it, most people with a family history of bipolar disorder will not develop it.

Though people with a parent or sibling with bipolar disorder are more likely to develop it, most people with a family history of bipolar disorder will not develop it.

Brain Structure and Function

Research shows that the brain structure and function of people with bipolar disorder may differ from those of people who do not have bipolar disorder or other mental disorders. Learning about the nature of these brain changes helps researchers better understand bipolar disorder and, in the future, may help predict which types of treatment will work best for a person with bipolar disorder.

How is bipolar disorder diagnosed?

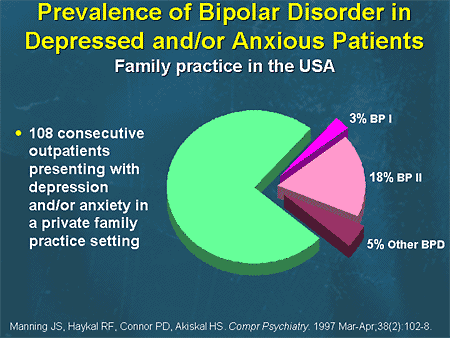

To diagnose bipolar disorder, a health care provider may complete a physical exam, order medical testing to rule out other illnesses, and refer the person for an evaluation by a mental health professional. Bipolar disorder is diagnosed based on the severity, length, and frequency of an individual’s symptoms and experiences over their lifetime.

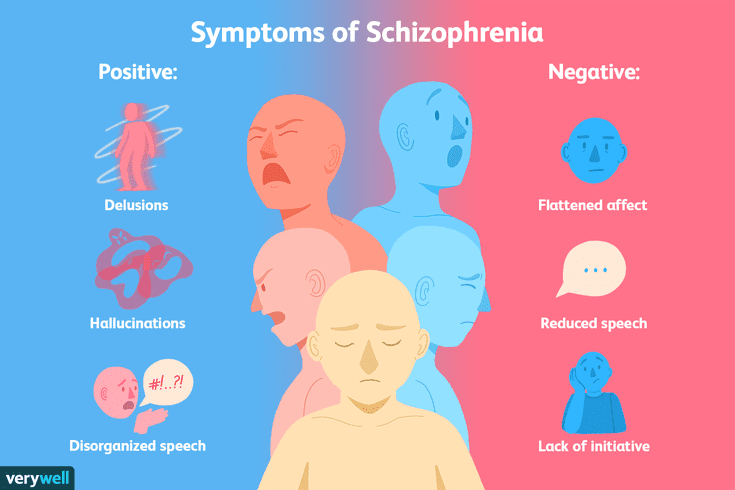

Some people have bipolar disorder for years before it’s diagnosed for several reasons. People with bipolar II disorder may seek help only for depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes may go unnoticed. Misdiagnosis may happen because some bipolar disorder symptoms are like those of other illnesses. For example, people with bipolar disorder who also have psychotic symptoms can be misdiagnosed with schizophrenia. Some health conditions, such as thyroid disease, can cause symptoms like those of bipolar disorder. The effects of recreational and illicit drugs can sometimes mimic or worsen mood symptoms.

Conditions That Can Co-Occur With Bipolar Disorder

Many people with bipolar disorder also have other mental disorders or conditions such as anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), misuse of drugs or alcohol, or eating disorders. Sometimes people who have severe manic or depressive episodes also have symptoms of psychosis, such as hallucinations or delusions. The psychotic symptoms tend to match the person’s extreme mood. For example, someone having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode may falsely believe they are financially ruined, while someone having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode may falsely believe they are famous or have special powers.

The psychotic symptoms tend to match the person’s extreme mood. For example, someone having psychotic symptoms during a depressive episode may falsely believe they are financially ruined, while someone having psychotic symptoms during a manic episode may falsely believe they are famous or have special powers.

Looking at symptoms over the course of the illness and the person’s family history can help determine whether a person has bipolar disorder along with another disorder.

How is bipolar disorder treated?

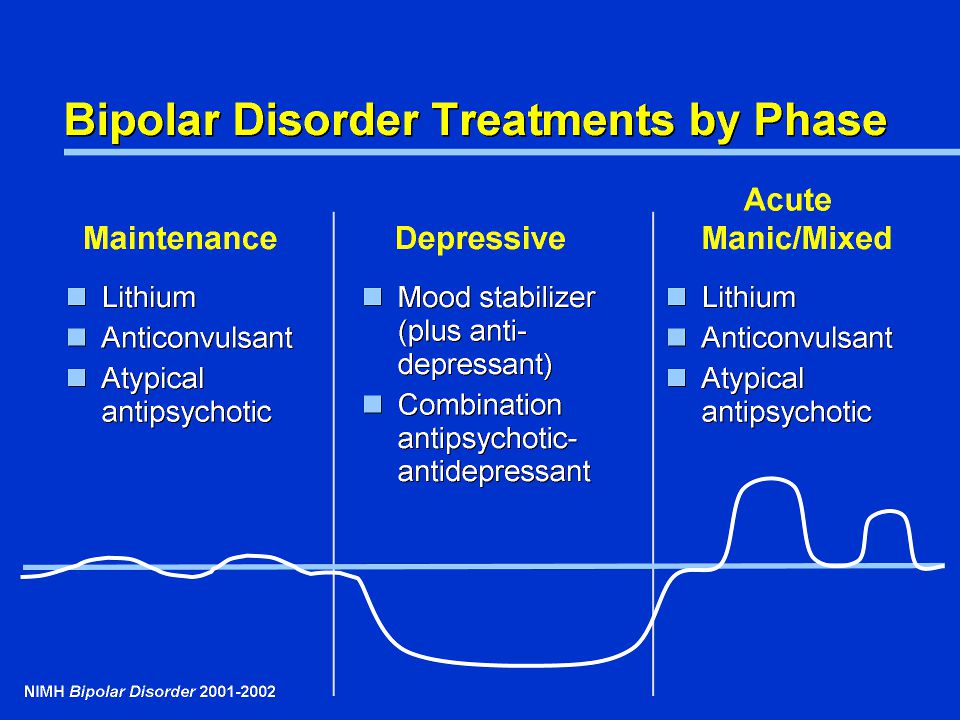

Treatment helps many people, even those with the most severe forms of bipolar disorder. Mental health professionals treat bipolar disorder with medications, psychotherapy, or a combination of treatments.

Medications

Certain medications can help control the symptoms of bipolar disorder. Some people may need to try several different medications before finding the ones that work best. The most common types of medications that doctors prescribe include mood stabilizers and atypical antipsychotics. Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate can help prevent mood episodes or reduce their severity. Lithium also can decrease the risk of suicide. While bipolar depression is often treated with antidepressant medication, a mood stabilizer must be taken as well, as an antidepressant alone can trigger a manic episode or rapid cycling in a person with bipolar disorder. Medications that target sleep or anxiety are sometimes added to mood stabilizers as part of a treatment plan.

Mood stabilizers such as lithium or valproate can help prevent mood episodes or reduce their severity. Lithium also can decrease the risk of suicide. While bipolar depression is often treated with antidepressant medication, a mood stabilizer must be taken as well, as an antidepressant alone can trigger a manic episode or rapid cycling in a person with bipolar disorder. Medications that target sleep or anxiety are sometimes added to mood stabilizers as part of a treatment plan.

Talk with your health care provider to understand the risks and benefits of each medication. Report any concerns about side effects to your health care provider right away. Avoid stopping medication without talking to your health care provider first. Read the latest medication warnings, patient medication guides, and information on newly approved medications on the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website.

Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy (sometimes called “talk therapy”) is a term for various treatment techniques that aim to help a person identify and change troubling emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. Psychotherapy can offer support, education, skills, and strategies to people with bipolar disorder and their families.

Psychotherapy can offer support, education, skills, and strategies to people with bipolar disorder and their families.

Some types of psychotherapy can be effective treatments for bipolar disorder when used with medications, including interpersonal and social rhythm therapy, which aims to understand and work with an individual’s biological and social rhythms. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is an important treatment for depression, and CBT adapted for the treatment of insomnia can be especially helpful as a component of the treatment of bipolar depression. Learn more on NIMH’s psychotherapies webpage.

Other Treatments

Some people may find other treatments helpful in managing their bipolar disorder symptoms.

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is a brain stimulation procedure that can help relieve severe symptoms of bipolar disorder. ECT is usually only considered if an individual’s illness has not improved after other treatments such as medication or psychotherapy, or in cases that require rapid response, such as with suicide risk or catatonia (a state of unresponsiveness).

- Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS) is a type of brain stimulation that uses magnetic waves, rather than the electrical stimulus of ECT, to relieve depression over a series of treatment sessions. Although not as powerful as ECT, TMS does not require general anesthesia and presents little risk of memory or adverse cognitive effects.

- Light Therapy is the best evidence-based treatment for seasonal affective disorder (SAD), and many people with bipolar disorder experience seasonal worsening of depression in the winter, in some cases to the point of SAD. Light therapy could also be considered for lesser forms of seasonal worsening of bipolar depression.

Complementary Health Approaches

Unlike specific psychotherapy and medication treatments that are scientifically proven to improve bipolar disorder symptoms, complementary health approaches for bipolar disorder, such as natural products, are not based on current knowledge or evidence. For more information, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website.

For more information, visit the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health website.

Coping With Bipolar Disorder

Living with bipolar disorder can be challenging, but there are ways to help yourself, as well as your friends and loved ones.

- Get treatment and stick with it. Treatment is the best way to start feeling better.

- Keep medical and therapy appointments and talk with your health care provider about treatment options.

- Take medication as directed.

- Structure activities. Keep a routine for eating, sleeping, and exercising.

- Try regular, vigorous exercise like jogging, swimming, or bicycling, which can help with depression and anxiety, promote better sleep, and is healthy for your heart and brain.

- Keep a life chart to help recognize your mood swings.

- Ask for help when trying to stick with your treatment.

- Be patient. Improvement takes time. Social support helps.

Remember, bipolar disorder is a lifelong illness, but long-term, ongoing treatment can help manage symptoms and enable you to live a healthy life.

Are there clinical trials studying bipolar disorder?

NIMH supports a wide range of research, including clinical trials that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions—including bipolar disorder. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge to help others in the future. Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct clinical trials with patients and healthy volunteers. Talk to a health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information, visit the NIMH clinical trials webpage.

Finding Help

Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

This online resource, provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), can help you locate mental health treatment facilities and programs. Find a facility in your state by searching SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. For additional resources, visit NIMH's Help for Mental Illnesses webpage.

Find a facility in your state by searching SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. For additional resources, visit NIMH's Help for Mental Illnesses webpage.

Talking to a Health Care Provider About Your Mental Health

If you or someone you know is in immediate distress or is thinking about hurting themselves, call or text the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline at 988 or chat at 988lifeline.org. You can also contact the Crisis Text Line (text HELLO to 741741). For medical emergencies, call 911.

Communicating well with a health care provider can improve your care and help you both make good choices about your health. Find tips to help prepare for and get the most out of your visit. For additional resources, including questions to ask a provider, visit the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website.

Reprints

This publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from NIMH. We encourage you to reproduce and use NIMH publications in your efforts to improve public health. If you do use our materials, we request that you cite the National Institute of Mental Health. To learn more about using NIMH publications, refer to NIMH’s reprint guidelines.

We encourage you to reproduce and use NIMH publications in your efforts to improve public health. If you do use our materials, we request that you cite the National Institute of Mental Health. To learn more about using NIMH publications, refer to NIMH’s reprint guidelines.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) (en español)

ClinicalTrials.gov (en español)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

NIH Publication No. 22-MH-8088

Revised 2022

What makes people unite | PSYCHOLOGIES

A wave of protests swept through Belarus; rallies and marches in Khabarovsk that stirred up the entire region; flash mobs against the ecological catastrophe in Kamchatka... It seems that the social distance has not increased, but, on the contrary, is rapidly decreasing.

Pickets and rallies, large-scale charity events on social networks, the "anti-handicapping project" Izoizolyatsiya, which has 580,000 members on Facebook (an extremist organization banned in Russia). It seems that after a long lull, we again needed to be together. Is it only the new technologies, which have significantly increased the speed of communication, the reason for this? What did “I” and “we” become in the 1920s? Social psychologist Takhir Bazarov reflects on this.

It seems that after a long lull, we again needed to be together. Is it only the new technologies, which have significantly increased the speed of communication, the reason for this? What did “I” and “we” become in the 1920s? Social psychologist Takhir Bazarov reflects on this.

Psychologies: There seems to be a new phenomenon: an action can break out anywhere on the planet at any time. We unite, although the situation seems to be conducive to disunity...

Takhir Bazarov: Writer and photographer Yuri Rost once answered a journalist in an interview who called him a lonely person: “It all depends on which side the key is inserted into the door . If outside, this is loneliness, and if inside, solitude. You can be together, while being in solitude. This is the name — “Seclusion as a union” — that my students came up with for the conference during self-isolation. Everyone was at home, but at the same time there was a feeling that we were together, we were close. It is fantastic!

It is fantastic!

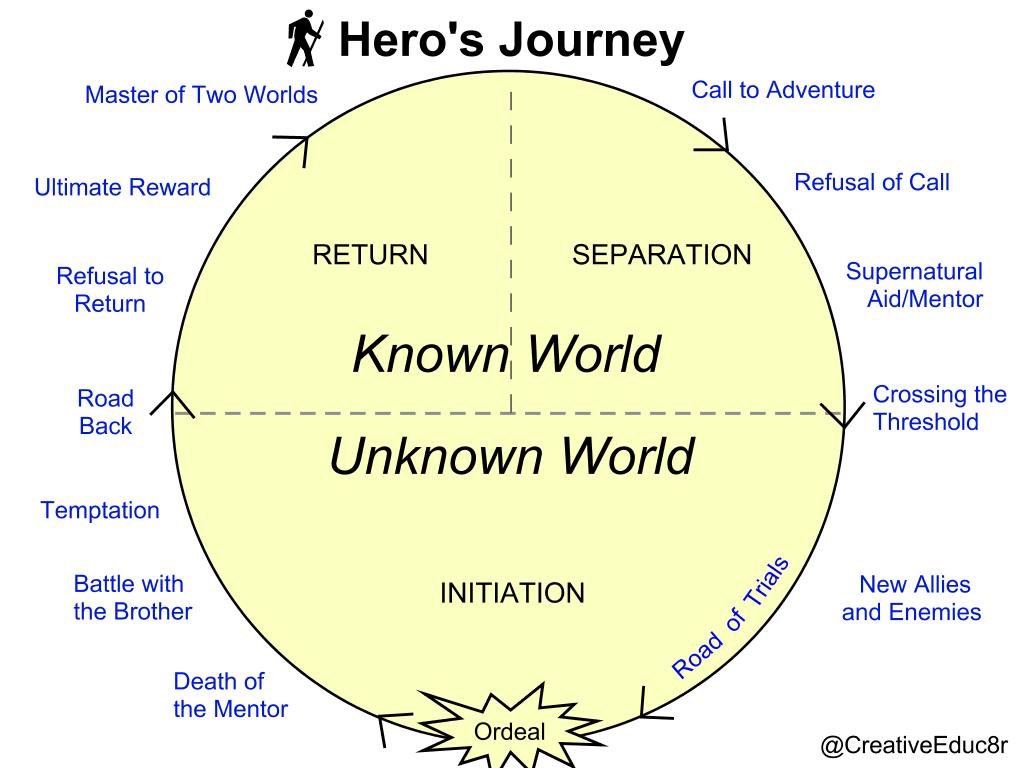

And in this sense, the answer to your question for me sounds like this: we unite, acquiring an individual identity. And today we are moving quite powerfully towards finding our own identity, everyone wants to answer the question: who am I? Why am I here? What are my meanings? Even at such a tender age as my 20 year old students. At the same time, we live in conditions of multiple identities, when we have a lot of roles, cultures, and various attachments.

It turns out that “I” became different, and “we” than a few years, and even more so decades ago?

Of course! If we consider the pre-revolutionary Russian mentality, then at the end of the 19th - beginning of the 20th century there was a strong demolition, which ultimately led to a revolution. Throughout the territory of the Russian Empire, except for those regions that were "set free" - Finland, Poland, the Baltic states - the feeling of "we" was of a communal nature. This is what cross-cultural psychologist Harry Triandis of the University of Illinois has defined as horizontal collectivism: when “we” unites everyone around me and next to me: family, village.

But there is also vertical collectivism, when “we” is Peter the Great, Suvorov, when it is considered in the context of historical time, it means involvement in the people, history. Horizontal collectivism is an effective social tool, it sets the rules of group influence, conformity, in which each of us lives. “Do not go to someone else’s monastery with your charter” - this is about him.

Why did this tool stop working?

Because it was necessary to create industrial production, workers were needed, but the village would not let go. And then Pyotr Arkadyevich Stolypin came up with his own reform - the first blow to the horizontal "we". Stolypin made it possible for peasants from the central provinces to leave with their families, villages for Siberia, the Urals, the Far East, where the yield was no less than in the European part of Russia. And the peasants began to live in farms and be responsible for their own land allotment, moving to the vertical “we”. Others went to the Putilov factory.

Others went to the Putilov factory.

It was Stolypin's reforms that led to the revolution. And then the state farms finally finished off the horizontal. Just imagine what was happening in the minds of Russian residents then. Here they lived in a village where everyone was one for all, the children were friends, and here a family of friends was dispossessed of kulaks, the neighbor's children were thrown out into the cold, and it was impossible to take them home. And it was the universal division of "we" into "I".

That is, the division of "we" into "I" did not happen by chance, but purposefully?

Yes, it was politics, it was necessary for the state to achieve its goals. As a result, everyone had to break something in themselves in order for the horizontal “we” to disappear. It was not until World War II that the horizontal turned on again. But they decided to back it up with a vertical: then, from somewhere out of oblivion, historical heroes were pulled out - Alexander Nevsky, Nakhimov, Suvorov, forgotten in previous Soviet years. Films about outstanding personalities were shot. The decisive moment was the return of shoulder straps to the army. It happened at 1943: those who tore off shoulder straps 20 years ago now sewed them back in a literal sense.

Films about outstanding personalities were shot. The decisive moment was the return of shoulder straps to the army. It happened at 1943: those who tore off shoulder straps 20 years ago now sewed them back in a literal sense.

Now this would be called a rebranding of "I": firstly, I understand that I am part of a larger story that includes Dmitry Donskoy and even Kolchak, and in this situation I am changing my identity. Secondly, without shoulder straps, we retreated, having reached the Volga. And since 1943, we stopped retreating. And there were tens of millions of such “I”, sewing themselves to the new history of the country, who thought: “Tomorrow I may die, but I prick my fingers with a needle, why?” It was powerful psychological technology.

And what is happening with self-consciousness now?

We are now facing, I think, a serious rethinking of ourselves. There are several factors that converge at one point. The most important is the acceleration of generational change. If earlier the generation was replaced in 10 years, now with a difference of only two years we do not understand each other. What can we say about the big difference in age!

If earlier the generation was replaced in 10 years, now with a difference of only two years we do not understand each other. What can we say about the big difference in age!

Modern students perceive information at a speed of 450 words per minute, and I, the professor who lectures them, at 200 words per minute. Where do they put 250 words? They start reading something in parallel, scanning in smartphones. I began to take this into account, gave them a task on the phone, Google documents, a discussion in Zoom. When switching from resource to resource, they are not distracted.

We are increasingly living in virtuality. Does it have a horizontal "we"?

Yes, but it becomes fast and short-lived. They just felt “we” - and they already fled. Elsewhere they united and scattered again. And there are many such “we”, where I am present. It's like ganglia, a kind of hubs, nodes around which others unite for a while. But what is interesting: if someone from my or a friendly hub is hurt, then I start to boil. “How did they remove the governor of the Khabarovsk Territory? How come they didn't consult us?" We already have a sense of justice.

“How did they remove the governor of the Khabarovsk Territory? How come they didn't consult us?" We already have a sense of justice.

This applies not only to Russia, Belarus or the USA, where there have recently been protests against racism. This is a general trend all over the world. States and any representatives of the authorities need to work very carefully with this new “we”. After all, what happened? If before Stolypin's stories "I" was dissolved into "we", now "we" is dissolved into "I". Each "I" becomes the carrier of this "we". Hence “I am Furgal”, “I am a fur seal”. And for us it is a password-review.

They often talk about external control: the protesters themselves cannot unite so quickly.

This is impossible to imagine. I am absolutely sure that Belarusians are sincerely active. The Marseillaise cannot be written for money, it can only be born in a moment of inspiration on a drunken night. It was then that she became the anthem of revolutionary France. And there was a touch to heaven. There are no such issues: they sat down, planned, wrote a concept, got a result. It's not technology, it's insight. As with Khabarovsk.

And there was a touch to heaven. There are no such issues: they sat down, planned, wrote a concept, got a result. It's not technology, it's insight. As with Khabarovsk.

There is no need to look for any external solutions at the time of the emergence of social activity. Then - yes, some become interested in joining this. But the very beginning, the birth is absolutely spontaneous. I would look for the reason in the discrepancy between reality and expectations. No matter how the story ends in Belarus or Khabarovsk, they have already shown that the network “we” will not tolerate outright cynicism and flagrant injustice. Today we are so sensitive to such seemingly ephemeral things as justice. Materialism goes aside - the network "we" is idealistic.

How then to manage society?

The world is moving towards building consensus schemes. Consensus is a very complicated thing, it has inverted mathematics and everything is illogical: how can the vote of one person be greater than the sum of the votes of all the others? This means that only a group of people who can be called peers can make such a decision. Who will we consider equal? Those who share common values with us. In horizontal "we" we collect only those who are equal to us and who reflect our common identity. And in this sense, even short-term "we" in their purposefulness, energy become very strong formations.

Who will we consider equal? Those who share common values with us. In horizontal "we" we collect only those who are equal to us and who reflect our common identity. And in this sense, even short-term "we" in their purposefulness, energy become very strong formations.

How does a person become a murderer?

In order to become a murderer, one must lose one's conscience. Conscience is a social and abstract concept. To find out how it is formed, many psychological studies have been carried out. Apparently, conscience is associated with the development of empathy, and, first of all, with the functioning of the brain.

Most murderers and rapists have either injuries or damage to certain areas of the brain. Such pathologies can be caused by blows to the head or falls, as well as drug or alcohol use in childhood. A person can also initially be born with a pathology, have problems with the development or incorrect functioning of a certain area of the brain. Also, almost everyone who commits serious crimes grew up in an unhealthy family atmosphere and felt very little love from their parents in childhood.

Lack of empathy

In order for a child to develop empathy, and subsequently a conscience, mother's love is necessary. Almost all the criminals who were subjected to psychological research experienced at least indifference from the mother, and quite often suffered from violence and bullying.

If a child has been bullied and prevented from developing since childhood, he may find pleasure in bullying someone else.

Empathy does not develop in a person if he does not have mirror neurons. These are special neurons that are located in the premotor cortex of the brain and are responsible for empathy and empathy. Either some kind of brain anomaly, or an unhealthy atmosphere in the family, lack of love from parents can lead to the absence of these neurons. If a child has been bullied and prevented from developing since childhood, he may find pleasure in bullying someone else. Sometimes this is just self-affirmation at the expense of another person, but in some cases it can even go as far as murder.

Violent motives

There are criminals who plan to kill and understand from the very beginning what exactly they want to achieve, and there are those who kill as a result of increased impulsiveness and aggression. Most killers commit crimes for pleasure and as revenge on someone who bullied them as a child, such as a mother, father, or brother.

If a child grows up in an atmosphere of violence, then the older he gets, the more he begins to understand what is happening to him. When he reaches a certain level of awareness, he may choose to kill other people as revenge on those who bullied him. For example, he can rape and kill women, redressing his aggression for bullying his mother. If a criminal kills women of a certain socio-economic status, then, first of all, during the investigation, they look for motives from his past, from his childhood - they try to understand whether this is connected with his family, environment or the place where he grew up.

Serial murders

Murderers commit crimes again and again due to repetitive motivation. The first kill is always the key in this case. What made a person commit a crime for the first time solidifies and turns into a desire to kill twice and thrice. That is, a crime brings satisfaction to a person, and he becomes dependent on this feeling, wants it to be repeated - at the time of murder, many substances are produced in the brain. Also, the killer may experience a separate pleasure from playing with the police and from the fact that they cannot be caught in any way.

Alcoholics and drug addicts are not more likely than others to become serial killers and rapists.

It is important to understand that repeat homicide addiction is not like drug or alcohol addiction and there are no studies showing that addictions are related. Alcoholics and drug addicts are not more likely than others to become serial killers and rapists.

See also

Mental norm and pathology

Psychiatric diagnosis

As a rule, psychiatric patients do not become murderers and rapists. If a patient with a psychiatric disorder commits such a crime, it is most likely due to either psychological defense against delusions, usually paranoid, or aggression as one of the symptoms of the disease. This can happen in a state of severe paranoid psychosis - a person who thinks that someone is following him will want to protect himself. For example, it may seem to the patient that his mother puts poison in his food, and she picks up a kitchen knife to stab him.

The question of whether a person commits a murder due to a psychiatric illness or for another reason is decided with the help of a forensic psychiatric examination. Specialists determine whether a person was responsible for his actions at the time of the crime. For example, a PTSD patient can kill someone because he flared up and could not restrain himself, without any connection to his disease.