What are the 5 stages of death

Five Stages of Grief by Elisabeth Kubler Ross & David Kessler

A Message from David Kessler

I was privileged to co-author two books with the legendary, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, as well as adapt her well-respected stages of dying for those in grief. As expected, the stages would present themselves differently in grief. In our book, On Grief and Grieving we present the adapted stages in the much needed area of grief. The stages have evolved since their introduction and have been very misunderstood over the past four decades. They were never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages. They are responses to loss that many people have, but there is not a typical response to loss as there is no typical loss.

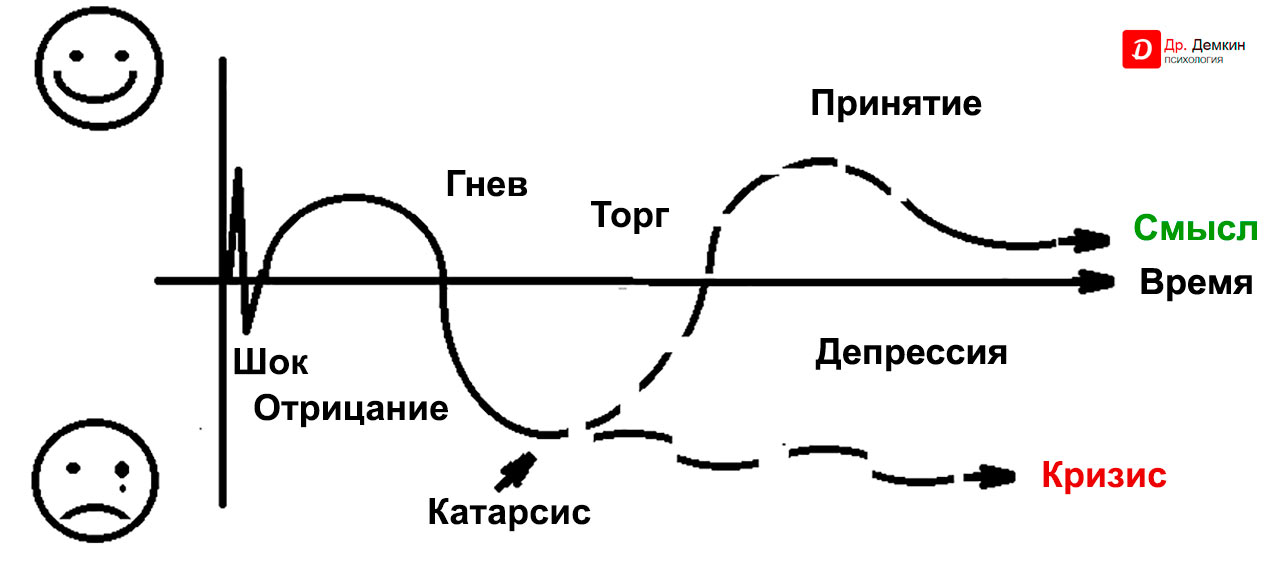

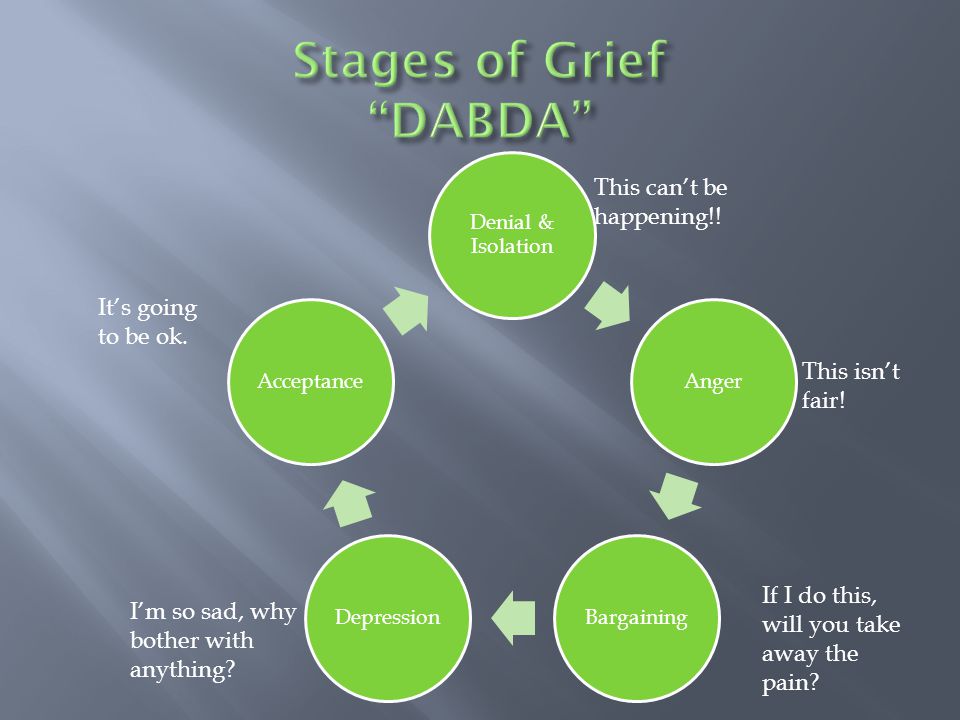

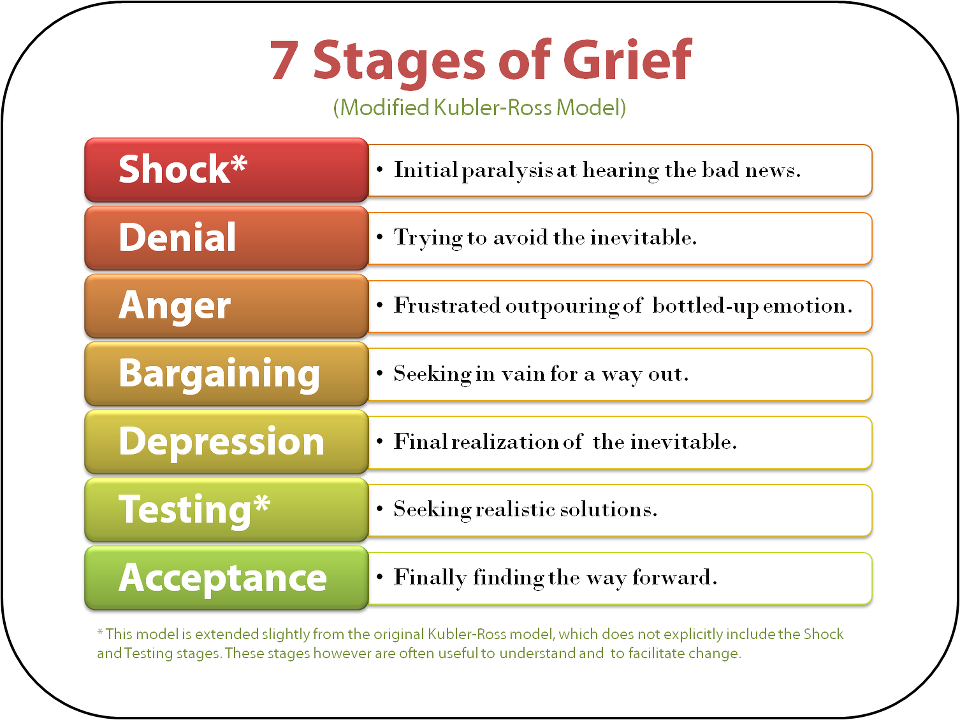

The five stages, denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance are a part of the framework that makes up our learning to live with the one we lost. They are tools to help us frame and identify what we may be feeling. But they are not stops on some linear timeline in grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order. Our hope is that with these stages comes the knowledge of grief ‘s terrain, making us better equipped to cope with life and loss. At times, people in grief will often report more stages. Just remember your grief is an unique as you are.

NEW BOOK

Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief

In this groundbreaking new work, David Kessler—an expert on grief and the coauthor with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross of the iconic On Grief and Grieving—journeys beyond the classic five stages to discover a sixth stage: meaning.

In this book, Kessler gives readers a roadmap to remembering those who have died with more love than pain; he shows us how to move forward in a way that honors our loved ones. Kessler’s insight is both professional and intensely personal. His journey with grief began when, as a child, he witnessed a mass shooting at the same time his mother was dying. For most of his life, Kessler taught physicians, nurses, counselors, police, and first responders about end of life, trauma, and grief, as well as leading talks and retreats for those experiencing grief. Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

How does the grief expert handle such a tragic loss? He knew he had to find a way through this unexpected, devastating loss, a way that would honor his son. That, ultimately, was the sixth state of grief—meaning. In Finding Meaning, Kessler shares the insights, collective wisdom, and powerful tools that will help those experiencing loss. Read More

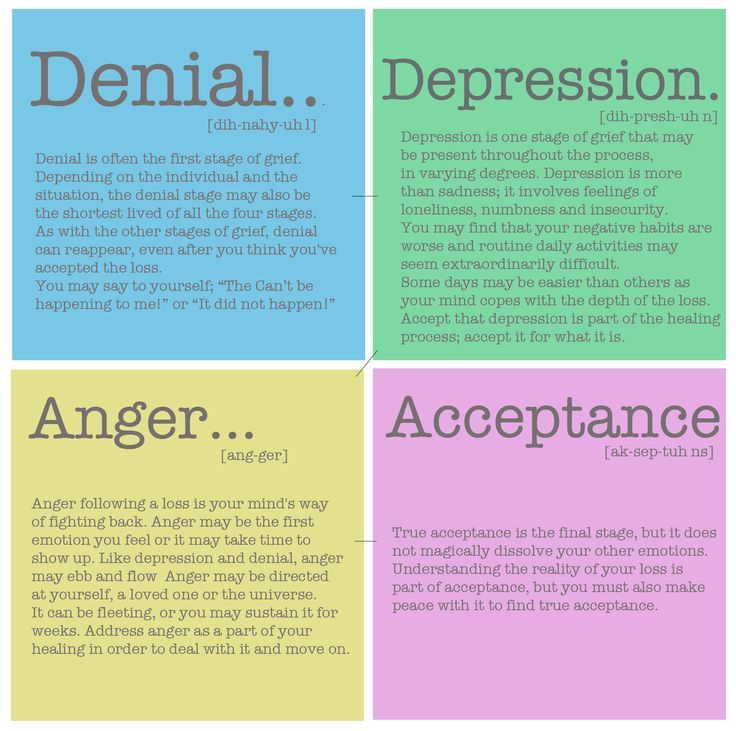

DENIAL Denial is the first of the five stages of grief™️. It helps us to survive the loss. In this stage, the world becomes meaningless and overwhelming. Life makes no sense. We are in a state of shock and denial. We go numb. We wonder how we can go on, if we can go on, why we should go on. We try to find a way to simply get through each day. Denial and shock help us to cope and make survival possible. Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It is nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle. As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

ANGERAnger is a necessary stage of the healing process. Be willing to feel your anger, even though it may seem endless. The more you truly feel it, the more it will begin to dissipate and the more you will heal. There are many other emotions under the anger and you will get to them in time, but anger is the emotion we are most used to managing. The truth is that anger has no limits. It can extend not only to your friends, the doctors, your family, yourself and your loved one who died, but also to God. You may ask, “Where is God in this? Underneath anger is pain, your pain. It is natural to feel deserted and abandoned, but we live in a society that fears anger. Anger is strength and it can be an anchor, giving temporary structure to the nothingness of loss. At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

BARGAININGBefore a loss, it seems like you will do anything if only your loved one would be spared. “Please God, ” you bargain, “I will never be angry at my wife again if you’ll just let her live.” After a loss, bargaining may take the form of a temporary truce. “What if I devote the rest of my life to helping others. Then can I wake up and realize this has all been a bad dream?” We become lost in a maze of “If only…” or “What if…” statements. We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion. We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion. We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

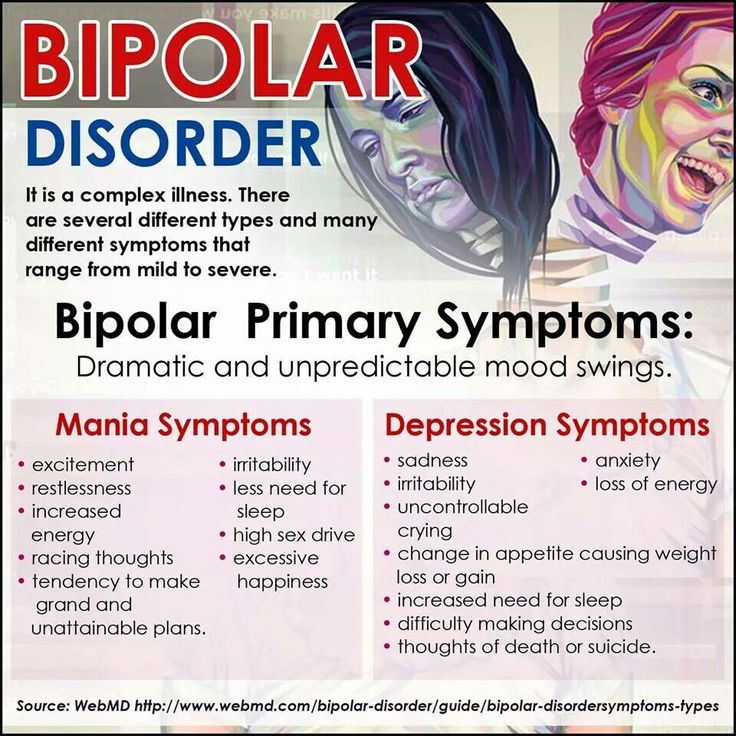

DEPRESSIONAfter bargaining, our attention moves squarely into the present. Empty feelings present themselves, and grief enters our lives on a deeper level, deeper than we ever imagined. This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever. It’s important to understand that this depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone? Why go on at all? Depression after a loss is too often seen as unnatural: a state to be fixed, something to snap out of. The first question to ask yourself is whether or not the situation you’re in is actually depressing. The loss of a loved one is a very depressing situation, and depression is a normal and appropriate response. To not experience depression after a loved one dies would be unusual. When a loss fully settles in your soul, the realization that your loved one didn’t get better this time and is not coming back is understandably depressing. If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever. It’s important to understand that this depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone? Why go on at all? Depression after a loss is too often seen as unnatural: a state to be fixed, something to snap out of. The first question to ask yourself is whether or not the situation you’re in is actually depressing. The loss of a loved one is a very depressing situation, and depression is a normal and appropriate response. To not experience depression after a loved one dies would be unusual. When a loss fully settles in your soul, the realization that your loved one didn’t get better this time and is not coming back is understandably depressing. If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

ACCEPTANCEAcceptance is often confused with the notion of being “all right” or “OK” with what has happened. This is not the case. Most people don’t ever feel OK or all right about the loss of a loved one. This stage is about accepting the reality that our loved one is physically gone and recognizing that this new reality is the permanent reality. We will never like this reality or make it OK, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. We must try to live now in a world where our loved one is missing. In resisting this new norm, at first many people want to maintain life as it was before a loved one died. In time, through bits and pieces of acceptance, however, we see that we cannot maintain the past intact. It has been forever changed and we must readjust. We must learn to reorganize roles, re-assign them to others or take them on ourselves. Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies.

This is not the case. Most people don’t ever feel OK or all right about the loss of a loved one. This stage is about accepting the reality that our loved one is physically gone and recognizing that this new reality is the permanent reality. We will never like this reality or make it OK, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. We must try to live now in a world where our loved one is missing. In resisting this new norm, at first many people want to maintain life as it was before a loved one died. In time, through bits and pieces of acceptance, however, we see that we cannot maintain the past intact. It has been forever changed and we must readjust. We must learn to reorganize roles, re-assign them to others or take them on ourselves. Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies. Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Learn More About The Five Areas of Grief

Watch The FREE Video Now Click Here

Books About the Five Stages by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler

Download Chapter One Click Here

Download Chapter One Click Here

5 stages of grief: What they are and how to get through them

CNN —

When someone you love dies, the world as you’ve known it is totally upended.

One way people cope, added psychologist Sherry Cormier, is by trying to find some sort of certainty. This need for structure is probably one factor behind the popularity that latched onto the “five stages of grief” over 50 years ago and hasn’t yet let up, said David Kessler, who founded grief.com, a resource aiming to help people deal with uncharted territory related to grief. Kessler coauthored “On Grief and Grieving” with the late Dr. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

A Swiss American psychiatrist and pioneer of studies on dying people, Kübler-Ross wrote “On Death and Dying,” the 1969 book in which she proposed the patient-focused, death-adjustment pattern, the “Five Stages of Grief. ” Those stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

” Those stages are denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance.

“In the actual book, she talked about more than five stages,” Kessler said. “Think about the context of 1969 – doctors and hospital personnel were not talking about the end-of-life process. … Elisabeth really hoped ‘On Death and Dying’ would start the conversation.”

Since then, there has been extensive media coverage of the five stages; use in television shows including “Grey’s Anatomy” and “House”; clinician support; and criticism. Those five stages are what people clung to, Kessler said.

Grief and psychology experts and academics have criticized the framework for not being thoroughly supported by research, suggesting that the bereaved move through grief sequentially or implying one correct way to grieve. But these suggestions weren’t Kübler-Ross’ intentions, and she stated these caveats on the first page of the book, Kessler said.

But these suggestions weren’t Kübler-Ross’ intentions, and she stated these caveats on the first page of the book, Kessler said.

While there’s debate among experts about the stages of grief, “people who are in the pain of grief are just saying, ‘Help me,’” Kessler said. Here’s what the five stages of grief are, and how you can consider and process them in whichever order you experience them.

In denial there is grace, in that we can’t fully register the total pain, shock and disbelief over our loss in one moment or day, so the pain is spread over time, Kessler said.

Grief isn't linear, as you might experience each stage within one moment, out of order or cyclically.

While denial in a literal and dysfunctional sense would be trying to convince yourself your loved one isn’t dead, an inability to comprehend the loss for a while is healthy – not something you need to quickly snap out of, he added.

If you’re struggling with overwhelming denial, you can try to stop fighting the reality you’ve been presented with, said Cormier, who is also a bereavement trauma specialist and consultant.

Anger is another natural reaction to loss, whether it’s anger at the cause of death, the deceased, the god of your religion, yourself or the randomness of the universe, Kessler said.

“Anger is pain’s bodyguard. It’s how we express pain,” he said. “That stage gives people permission to be angry in healthy ways, and to know it’s not bad.”

Courtesy of Museo Reina Sofia, Madrid

The art of processing our collective grief

Anger “can be an anchor, giving temporary structure to the nothingness of loss. At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything,” according to Kessler’s website. “Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – your anger toward them.”

Suddenly you have a structure – your anger toward them.”

Beneath anger can be feelings of hopelessness or powerlessness, Cormier said, sometimes prompting guilt and blame that some people use to maintain an illusion of control or express frustration.

“Our minds would always rather feel guilty than helpless,” Kessler said.

Depending on how your loved one died, one way to overcome guilt- and blame-related anger is by realizing that as horrific as your loss is, it wasn’t personally done to you, Kessler said.

“The reality is the death rate in families is 100%,” he said. “Everyone is going to die eventually, but our minds just can’t fathom that.”

Allow yourself to express anger in healthy ways, Kessler advised, whether it’s “grief yoga,” screaming in your car, using a punching bag, running or other forms of exercise.

Often also stemming from guilt, bargaining after a loss typically involves “if only” statements, focused on regrets about what you did or didn’t do before the person died, Kessler said.

Shutterstock

Grief-induced anxiety: Calming the fears that follow loss

“We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss,” Kessler’s site says. “People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another.”

Remember that we live in a world where sometimes bad things happen despite our best efforts, Kessler said.

Depression, or an acute sadness, is when the great loss begins more deeply affecting your life. Maybe the sadness feels as if it will last forever, or you’ve withdrawn from life or are wondering if life is worth living alone.

Maybe the sadness feels as if it will last forever, or you’ve withdrawn from life or are wondering if life is worth living alone.

Sadness hits people at different times, Cormier said. She has known people who aren’t distraught in the first year after loss, but by year three are consumed with sadness. Why? Because for a time, some can maintain the illusion that their loved one is away on vacation and may be returning, she said.

Overcoming Depression: Facts and Resources

Often, the eventual, deep sadness “is really an expression of, ‘my loved one is gone and not coming back,’” Cormier said.

But those feelings shouldn’t always be labeled as clinical depression, Kessler said. If you think you’re depressed around a death, see a psychiatrist for an evaluation, he advised.

To cope with sadness, you can also seek support from friends, family or grief support groups, and regularly practice self-care, Cormier suggested.

Acceptance doesn’t mean you’re OK with your loved one being gone. “It just means that I now accept the new reality of my life. I’m a widow, I live alone. I don’t have siblings to call up anymore. I don’t have parents to call up anymore,” said Cormier, who wrote “Sweet Sorrow: Finding Enduring Wholeness After Grief and Loss” after losing her husband and immediate family.

Acceptance isn’t grief’s end, either. You might have many little moments of acceptance over time, Kessler said, such as when you plan and attend the funeral.

“One of the questions I get asked most is, ‘When will this grief be over?’” Kessler added. “Very gently, I’ll ask, ‘How long is the person going to be dead? Because if the person is going to be dead for a long time, you’re going to grieve for a long time. It doesn’t mean you will always grieve with pain. To me, the goal of grief work is to eventually remember the person with more love than pain.”

“Very gently, I’ll ask, ‘How long is the person going to be dead? Because if the person is going to be dead for a long time, you’re going to grieve for a long time. It doesn’t mean you will always grieve with pain. To me, the goal of grief work is to eventually remember the person with more love than pain.”

Courtesy Ruedi Habegger

My friend chose an assisted death in Switzerland. Her dying wish was to tell you why

Arriving at acceptance means you’re healing, Cormier said. But if you can’t get there, you need to seek professional help. Intense and persistent grief that causes problems and interferes with everyday functioning, in a way that typical grief doesn’t after some time has passed, is known as prolonged grief disorder, according to the American Psychiatric Association. The disorder is the newest disorder to be added to the revised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders released in March.

The disorder is the newest disorder to be added to the revised Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders released in March.

To be diagnosed with prolonged grief disorder, a loved one’s death had to have occurred at least a year prior for adults, and at least six months ago for children and adolescents, according to the association, which publishes the DSM. One symptom is difficulty with reintegration, such as pursuing interests or interacting with friends.

Cormier doesn’t think we ever “get over” grief. Our task is different than moving on – it’s learning to integrate the loss into our lives so that we can move forward with a new reality, she added. “It’s sort of offensive to grievers to say, ‘Oh, you’ve really moved on.’ No, I don’t think grievers move on. We move forward.”

“It’s sort of offensive to grievers to say, ‘Oh, you’ve really moved on.’ No, I don’t think grievers move on. We move forward.”

After Kessler’s son died at age 21 nearly five years ago, Kessler wanted something beyond acceptance. He had studied late neurologist, psychiatrist and philosopher Dr. Viktor Frankl’s work on meaning, and wondered how meaning related to grief – which inspired his book “Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief.”

Meaning didn’t eliminate Kessler’s pain, but it did cushion it, he said.

Meaning is in what we later do or realize as the bereaved people, Kessler explained. Maybe you recognize the fragility of life, try to change a law or donate money to research so no one dies the way your loved one did, or make a change in your life.

Maybe you recognize the fragility of life, try to change a law or donate money to research so no one dies the way your loved one did, or make a change in your life.

Sign up for CNN’s Stress, But Less newsletter. Our six-part mindfulness guide will inform and inspire you to reduce stress while learning how to harness it.

Stages of accepting the inevitable: what are they and how to survive them

. And how to help them survive a loved one. Psychologists adviseUpdated November 16, 2022, 10:53

Shutterstock

Each person copes with difficult circumstances in their own way. One way to get through a difficult life period is to go through all the stages: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. However, according to psychologists, in practice this model is not so unambiguous. There is no single recipe. But there are ways to help yourself and loved ones during this difficult time. RBC Life talked to psychologists and found out the details. nine0003

But there are ways to help yourself and loved ones during this difficult time. RBC Life talked to psychologists and found out the details. nine0003

Contents

- How We Accept the Inevitable

- The Stages of Acceptance

- 5 Tips

- How to Help a Loved One

How We Accept the Inevitable

Shutterstock

The inevitable is unforeseen events of varying degrees of drama: illness, separation, layoffs, accidents, death of relatives and friends. During a lifetime, a person can experience such difficult situations several times - and not always the range of emotions will be the same. For example, while one will hide his head in the sand and refuse to make any decisions, the other may completely evade reality - there are many scenarios. Be that as it may, psychologists are unanimous: all these reactions are normal, since in a similar way the human psyche is looking for ways to protect itself and save itself. nine0003

nine0003

One way to get through a difficult situation is to accept it. From an emotional point of view, this does not at all mean “to approve or support what happened.”

Acceptance is the recognition of a new objective reality as it is. To be at this point, a person needs time - for everyone it is different.

In psychology, there are at least ten models that describe the process of acceptance. Here are some of the more common examples.

- Sigmund Freud's theory of grief. nine0010 The psychoanalyst saw the acceptance process as follows: breaking the connection, adjusting to new life circumstances and building new relationships [1].

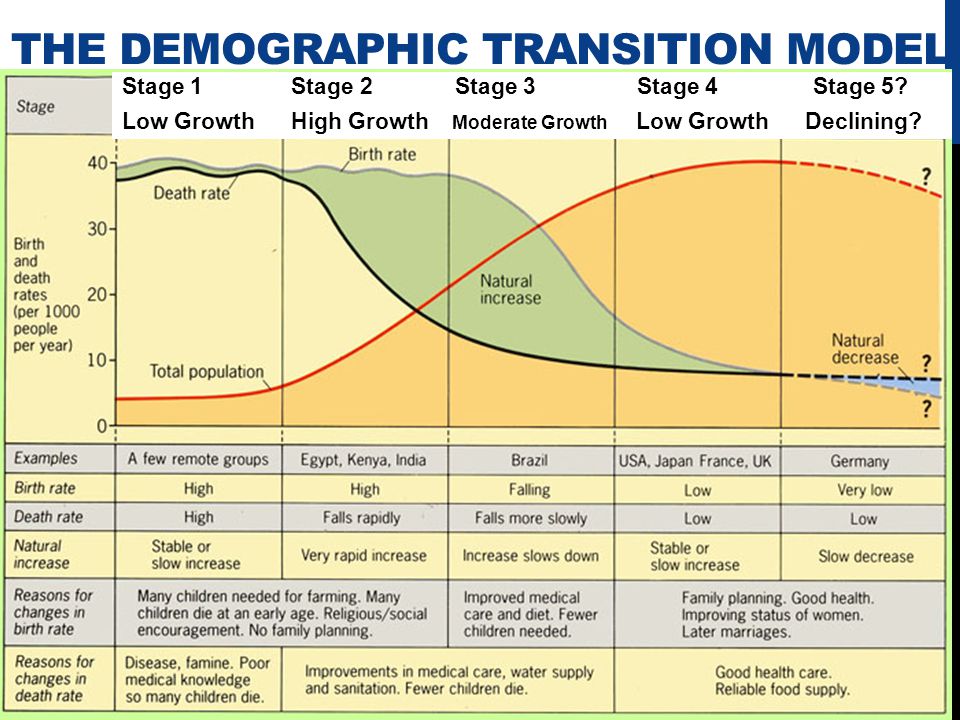

- Stages of acceptance by Kübler-Ross . The most well-known theory of the five stages of acceptance is denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. Often this model is perceived as linear, that is, a person sequentially goes through each of the stages. But Kübler-Ross herself noted that this is not her statement and that each individual stage may manifest itself in different ways or be completely absent [2].

nine0014

- Model of two processes Strebe and Schut. An example of a cyclic model in which a person seems to fluctuate between two states: recognizing the loss and experiencing pain, moving away from emotions and resolving practical issues caused by what is lost. These two processes are cyclically repeated, gradually healing the person [3].

- Six R Teresa Rando. Named after the first letter of each stage: Recognize, React to the separation, Recollect and re-experience, Relinquish old attachments, Readjust ) and reinvestment of emotional energy, the beginning of a new life (Reinvest) [4]. nine0014

- Scott and Japhy Curve . In this model, experiences occur along a U-shaped trajectory. The high point at the beginning is characterized by almost manic denial, shock and anger, the low point by despair and depression, the high point at the end of the curve is a recovery of energy and morale. This approach is predominantly focused on accepting events before they happen.

For example, an impending dismissal or something else that does not depend on us [5].

For example, an impending dismissal or something else that does not depend on us [5].

Shutterstock

Psychologists agree that it is often easier for the psyche of a person faced with severe grief or something inevitable to accept and experience something structured. “In modern practices, the Kubler-Ross stage model continues to be applied,” says Luiza Istomina, a medical psychologist at the European Medical Center. - It is used as a kind of support, helping to understand the principle of processes that replace each other. However, there is not enough empirical evidence to support or refute it. But, if it’s easier for you to accept what happened, you can focus on these stages. ” nine0003

1. Negation

A person unconsciously rejects events and begins to doubt them. For example, the laboratory mixed up the tests that confirmed a fatal illness, or the death of a loved one was reported by mistake.

Luiza IstominaMedical psychologist at the European Medical Center

“This state can last from a few seconds to several weeks, on average, by the seventh or ninth day, gradually changing to another. At this time, it is more important than ever to maintain your usual lifestyle: adhere to the sleep and wakefulness regimen, monitor nutrition, devote time to physical activity, and follow a daily routine. You can make a list of activities and activities that help relieve psycho-emotional stress: knitting, drawing, listening to music. It will be useful to use Mindfulness awareness techniques, since at the stage of denial a person may experience a feeling of detachment from the world, stupor, insensitivity. nine0003

At this time, it is more important than ever to maintain your usual lifestyle: adhere to the sleep and wakefulness regimen, monitor nutrition, devote time to physical activity, and follow a daily routine. You can make a list of activities and activities that help relieve psycho-emotional stress: knitting, drawing, listening to music. It will be useful to use Mindfulness awareness techniques, since at the stage of denial a person may experience a feeling of detachment from the world, stupor, insensitivity. nine0003

As soon as the denial and shock begin to fade, feelings that the person has previously suppressed come out.

2. Anger

Anger and anger at the moment of grief or a disturbing event is a natural reaction. Even if it seems that anger and anger are endless, these emotions will still dissipate - and the more you truly feel them, the faster this will happen [6]. At this stage, a person may have thoughts like “why me and not someone else?” or "life isn't fair. " Redirecting anger to others is dysfunctional behavior. nine0003

" Redirecting anger to others is dysfunctional behavior. nine0003

At this stage, as psychologists note, physical activity and sports will be especially useful. For example, Luiza Istomina recommends trying muscle relaxation techniques - Schulz's autogenic training or Ost's applied relaxation.

3. Bargaining

When something bad happens, a person can start an internal bargaining, promising to change something in himself and his life in order to improve the situation. Also at this stage, reasoning can torment, for example: "If I had left the house five minutes earlier, the accident would not have happened." nine0003

Shutterstock

To make it easier to pass this stage, it is useful to know about one non-obvious phenomenon. It turns out that it is easier for the psyche to accept the fact that a person is to blame and he could change something. This is a kind of trick of the psyche in response to a shock event. And this is worth remembering. In reality, such an attempt to bargain with oneself is nothing more than distortion and false hope.

To understand that what happened is not your fault, try to understand the reasons for what happened. If it is a disease, study it in more detail. Having read the necessary literature and received the necessary information, one can come to the conclusion that it was simply impossible to influence the course of treatment and its outcome. nine0003

4. Depression

Depression is the emptiness that a person feels when realizing that life will no longer be the same, for example, due to a sudden change in circumstances or loss. This is a phase of acute grief that lasts six to seven weeks from the onset of a tragic event. This is a period of despair and disorganization.

Luiza Istomina:

“At this step, separation begins, detachment from the object of loss, there is a gradual entry into reality, which will then allow you to combine the image of the lost, which remained in the past, with life in the present. At this stage, destructive and self-destructive coping strategies - dangerous behavior, the use of psychoactive substances, self-harm, the emergence of anti-vital and suicidal thoughts will be alarm bells. Support from loved ones and professional advice will help here. ” nine0003

Support from loved ones and professional advice will help here. ” nine0003

5. Acceptance

At this point the emotions begin to stabilize as the person finally comes to terms with the fact that the new reality will now be different. In essence, we acknowledge the changes that have taken place. But this does not mean that a person evaluates them positively, just now you can live with it. To make it easier to move from depression to acceptance, you can try to learn constructive grief coping skills.

Luiza Istomina:

“Try writing down a negative automatic thought followed by cognitive restructuring (CBT approach). Example: “I can’t deal with this pain” is changed to “I have had suffering in my life, and I was able to cope with it, I need to give myself time.” Cognitive disconnection techniques (ACT-approach) can be applied. We track the depressive thought “My life will not be the same” and put it in a larger frame: “I have a thought that my life will not be the same. ” nine0003

” nine0003

The commit process may have some backtracking. It's demotivating and can be intimidating. However, it is possible to find ways to deal with regression.

In order to experience regression, according to Albina Borisenko, a psychotherapist in the ORCT approach (solution-oriented short-term therapy), a specialist in the Alter psychological platform, one can turn to an example with a metaphor. To do this, it is necessary to imagine that the process of acceptance is a kind of path: a road, a path or a ladder. nine0003

Albina Borisenkopsychotherapist in the ORCT approach, specialist in the psychological platform Alter

“Standing at some point on this path, you can turn around and see how far you have already traveled. To regress is only to take a step or a few steps back along a path that has already been traveled. That is, to be where you already were. So, you already absolutely know exactly how to move on and what can help. It is somewhat reminiscent of a computer game, where the completed levels are clear and understandable, and going through them again is not so scary, despite the difficulties that we know about. That means you're already on your way." nine0003

It is somewhat reminiscent of a computer game, where the completed levels are clear and understandable, and going through them again is not so scary, despite the difficulties that we know about. That means you're already on your way." nine0003

5 tips for accepting the inevitable

Shutterstock

Each of us is individual, so the same advice for someone will be healing, and for someone - absolutely useless. But each of us can listen to ourselves and understand what will help here and now. Here is what experts [7], [8], [9] advise.

1. Allow yourself to be sad

Expression of emotions can be an important part of the acceptance process. Don't judge yourself or compare yourself to others. Everyone mourns differently. If you suddenly feel like crying, give yourself that opportunity. There are many ways to express emotions: you can hit a punching bag or a ball for a healthy release of anger, or turn to creativity. For example, download a mobile application for music and art therapy. At the same time, write down all your feelings, experiences and thoughts in a diary. Over time, you will be able to see how your grief changes. nine0003

At the same time, write down all your feelings, experiences and thoughts in a diary. Over time, you will be able to see how your grief changes. nine0003

2. Ask for help

“Man is a social animal, and it is objectively difficult for us to survive without society,” says psychologist Borisenko. - Talking to a doctor, people in a support group, a relative or trusted friend can be a big help in a moment of grief. Don't be afraid to ask others for help and support. No, you will not be intrusive and will not lay responsibility on someone: a person always has the right to refuse. At the same time, you can always make a request – this is normal and part of human communication.” nine0003

The same applies to offers of assistance. Do not rush to refuse if someone close to you decides to help you with house cleaning, grocery shopping or laundry. It won't make you weaker.

3. Look after your health

Get regular exercise, eat as healthy as possible, and make sure you get enough sleep. Avoid excessive use of alcohol and other psychotropic substances. All this can not only contribute to the deterioration of mental health, but also directly affect your safety. For example, avoid self-driving and other potentially dangerous activities during times of intense emotion. nine0003

Avoid excessive use of alcohol and other psychotropic substances. All this can not only contribute to the deterioration of mental health, but also directly affect your safety. For example, avoid self-driving and other potentially dangerous activities during times of intense emotion. nine0003

4. Set small goals

Do not try to do everything at once - set small goals that are easy to achieve. “Make a list of different and most insignificant things: a cup of coffee in the morning, your favorite TV series or a walk in the park. Write down each item on how it helps the healing. Then, looking from the outside, you can see how much you do for yourself every day and how much more you can do,” says Albina Borisenko.

Also try to refrain from making major decisions, such as moving, for a while. But if this is inevitable, then, on the advice of a psychologist, the following technique will help. nine0003

Albina Borisenko:

“You shouldn't think about moving as one big act “I'm moving”. This is too big a step and therefore frightening. "I'm moving" consists of a lot of tiny steps: "I weigh the pros and cons," "I talk to my family," "I look at the list of required documents," and so on.

This is too big a step and therefore frightening. "I'm moving" consists of a lot of tiny steps: "I weigh the pros and cons," "I talk to my family," "I look at the list of required documents," and so on.

5. Stay Connected

Birthdays, anniversaries and holidays associated with a deceased person can cause a strong sense of grief. But do not completely cross out these days from your life. Celebrate a memorable date by lighting candles, meeting with family, or raising funds for charity. Simple rituals will maintain a sense of connection and emphasize that you continue to respect and appreciate the relationship that was. Keep a diary or write a letter to the person you have lost on an important date for both of you. nine0003

How to help a loved one accept the inevitable

Shutterstock

Some research suggests that the amount and quality of social support can affect the well-being of those who are grieving. The support of a loved one going through painful events can be critical to acceptance. But how to do it right? Here are some tips from experts [10].

But how to do it right? Here are some tips from experts [10].

1. Call a spade a spade

Do not be afraid, for example, to mention the name of a dead person or to talk about a situation the person is going through. This will avoid the unpleasant feeling that, for example, a loved one who has passed away is forever erased from memory. In such a situation, it is better to note that you will be bored than to say formally: "I'm sorry about the loss." nine0003

2. Give practical help

Do not ask how you can help, but act. Cook dinner, buy groceries, clean the house of the person you want to help. For many people, such as those who have lost a spouse, getting used to planning and living alone can be a big challenge.

3. Avoid annoying phrases

If you ask a grieving person how things are going, the answer is obviously "Bad." Instead, you can ask, “How are you feeling today?” Also, on the advice of experts, for some time it is better to refrain from the phrases “this is the will of God / the Universe / life” or “this is for the best”, until the person who has lost loved ones says it first. nine0003

nine0003

4. Be a good listener

Listen carefully, but do not give advice or judge. Perhaps, on the path of acceptance, you will have to listen to your loved one the story of loss dozens of times in the smallest detail. Don't stop the person, as talking through the situation is one way to get through it. Do not rush to give advice, especially if you are not asked for it. Often the one who mourns wants one thing - to simply be heard. Don't rush things. May your loved one recover at their own pace. But if the depression has lingered or you notice disturbing changes in the behavior and thoughts of a loved one, be sure to consult with a specialist about what help can be provided in this case. nine0003

5. Respect others' grief

There is no right or wrong way to grieve. Everyone does it in their own way. A person experiencing grief will have emotional ups and downs for a while. This is a normal part of the grieving process. Don't try to fix it, much less condemn the mourner. Think about how you can help a person smooth out these fluctuations, for example, with the help of creativity. Offer to sign up for art classes, dance classes, or simply spend more time doing something creative together. nine0003

Think about how you can help a person smooth out these fluctuations, for example, with the help of creativity. Offer to sign up for art classes, dance classes, or simply spend more time doing something creative together. nine0003

Share

Article content

Authors

Tags

Nadezhda Gurina

You may be interested

5 stages of accepting death

Death is always sorrowful for people close to the afflicted. But even when the deceased was buried, his relatives remain inconsolable for many months. How to help in such a situation?

First of all, you need to understand that there are several psychological stages that every grieving person goes through. Overcoming these stages helps people restore mental balance, broken by a sudden break in ties with the deceased. At each stage, grief is felt a little differently than at another - knowing this, it becomes easier to support a person. If his condition suddenly worsens, you can figure out if the grieving person needs qualified help from a psychologist. nine0003

nine0003

Stage 1: dumbfounded. Lasts about 7-9 days.

It is difficult for people in this period to realize the very fact of losing a loved one, its completeness and irrevocable. Some react to this with something like a stupor, unresponsiveness; others take on a lot of things: participate in the organization of the funeral, trying to support someone else. This kind of fussiness, however, is not a genuine emotional reaction. These people are not insensitive, just that they are not yet aware of their feelings. Sometimes there is "depersonalization": it seems to a person that he or she is losing identity, perceives everything as if from the outside. Although it seems strange, this kind of reaction is psychologically normal: call the person's name more often, drink sedatives, in extreme cases rubbing the limbs helps (the feeling of the body as "one's own" returns). nine0003

Particularly sensitive people try to commit suicide, seeking to reunite with the deceased - make sure that someone is always with such people. Argued speech does not work at this stage, it is better to just let the grief come out: let the tears flow, and the person stands at the coffin for hours. Those who still remain in a stupor need help to give vent to feelings.

Argued speech does not work at this stage, it is better to just let the grief come out: let the tears flow, and the person stands at the coffin for hours. Those who still remain in a stupor need help to give vent to feelings.

Stage 2: rejection. Lasts about 35-40 days.

The custom of celebrating a commemoration was naturally formed at the border of the period when the psyche of people is ready to "part" with the deceased. At this stage, the consciousness is already able to comprehend the loss, but the subconscious and body memory are not. From here, hallucinations sometimes arise: people see the deceased in the crowd, hear something like an echo of steps, etc. nine0003

In particular, dreams about the deceased should be taken positively. If the loss is very acute, in your thoughts it will not be superfluous to call on the deceased to look into a dream. The opposite is dangerous: if at this stage the deceased did not dream at all, then it seems that the “work of mourning” has somehow stalled, and psychological counseling is needed. Keep up all the conversations that arise about the deceased. Crying at this stage should be regarded positively.

Keep up all the conversations that arise about the deceased. Crying at this stage should be regarded positively.

Stage 3: acceptance of the loss, full awareness of the loss. Lasts up to 6 months. nine0023

Sorrow rolls in waves: now more, then again less. The fact is that the human consciousness adapts to ongoing grief, but not always successfully. In the middle of this stage (3rd month) there is often a sharp decline: internal reserves are depleted, barriers are falling - the pain of loss is sharper than ever, and there is no feeling that this will ever change. During this period, correct, albeit unusual feelings arise: guilt towards the deceased (“you are dead, and I am here among the living”), anger at the deceased (“you left me, left!”), anger at outsiders. nine0003

Let's talk briefly about each of them:

- guilt towards the deceased, oddly enough, is an attempt to regain a sense of control over what is happening. For many, it is accompanied by thoughts like "I could have done something to prevent this from happening" - however, in most cases this is not true in fact, but is only an attempt by memory to rethink death in the usual way.

- Anger at the deceased is also normal, but only for a while. Often it is accompanied by a sense of personal resentment, as if the death was an intentional act. Many people are confused by the very occurrence of such a thought, but it should be accepted and overcome. nine0014

- Finally, anger at third parties occurs most often as a "transfer effect". Public opinion condemns the feeling of anger at the dead, so consciousness is looking for a way out, projecting it onto doctors, directors, the country and even religious figures ("the saint did not help in time"). There is also a time for this phase, but it is important not to let it drag on too long.

During the entire 3rd stage, the mourner learns to exist without the deceased. During the normal "work of mourning", the deceased ceases to dream in everyday situations, but often appears in other worlds, etc. nine0003

Stage 4: consolation of grief. Lasts until the end of the first year after death.

During this stage, there is an acceptance that a loved one is dead in every sense, has ceased to be in this world. A person is forming the contours of a new life; good to meet new people. An indicator that the "work of mourning" is going well is that the mourner mentions the deceased as if alive and tells stories about joyful episodes of his biography. Thanks to such shifts, there is a feeling that the mourner has already been able to adapt to the grief of loss. nine0003

A person is forming the contours of a new life; good to meet new people. An indicator that the "work of mourning" is going well is that the mourner mentions the deceased as if alive and tells stories about joyful episodes of his biography. Thanks to such shifts, there is a feeling that the mourner has already been able to adapt to the grief of loss. nine0003

This stage corresponds to a sense of self, sometimes called "light sadness": when the intensity of grief drops to the level of nostalgia. The fact is that when we live, we change the situation, and no one is used to saying goodbye to the past. Nostalgia is a way of our memory to come to terms with the irreversibility of a moment in the past, accepting it through beauty and joyful-sad emotional coloring.

Stage 5: all stages are repeated in a relaxed form. Lasts until the end of the second year.

The mourning resumes around the death anniversary (because the memory is tied to the date). However, the management of grief is already more or less formed, and therefore the surge of grief is not so sharp.