Type a personality and adhd

The Relationship of Personality Style and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children

Kans J Med. 2017 May; 10(2): 26–29.

Published online 2017 May 15.

Stephen P. Amos, Ph.D., Gretchen J. Homan, M.D., Natalie Sollo, M.D., Carolyn R. Ahlers-Schmidt, Ph.D., Matthew Engel, MPH, and Patrice Rawlins, APRN

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Introduction

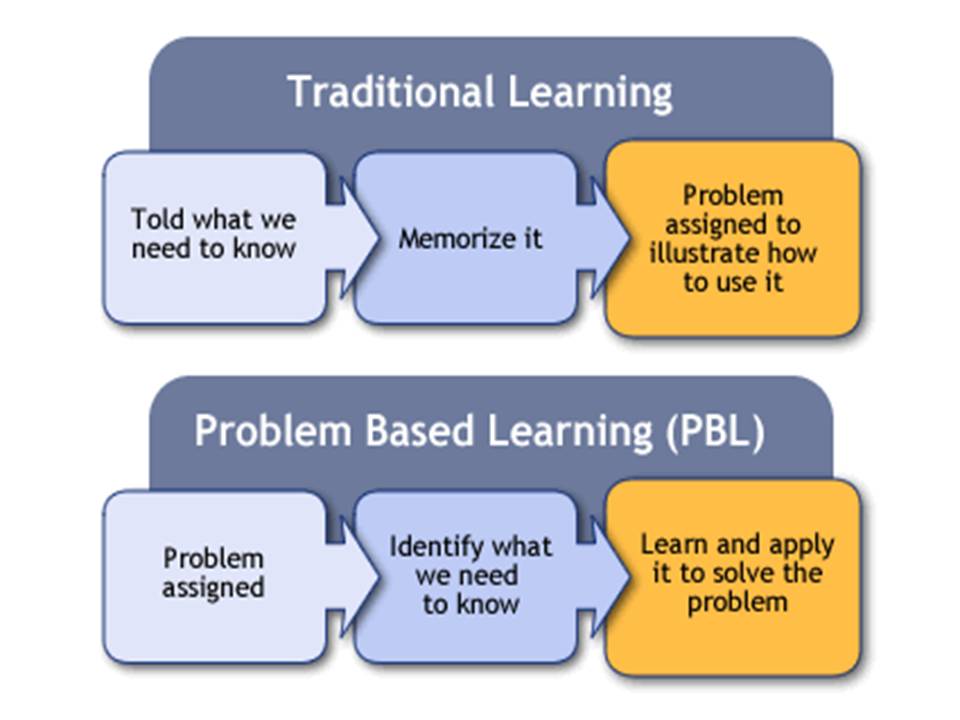

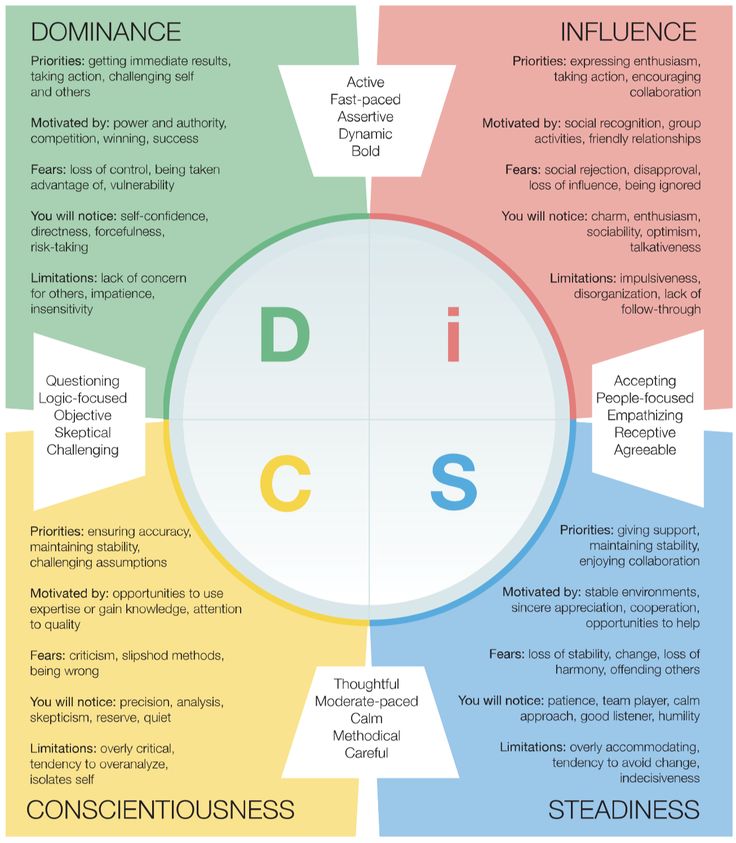

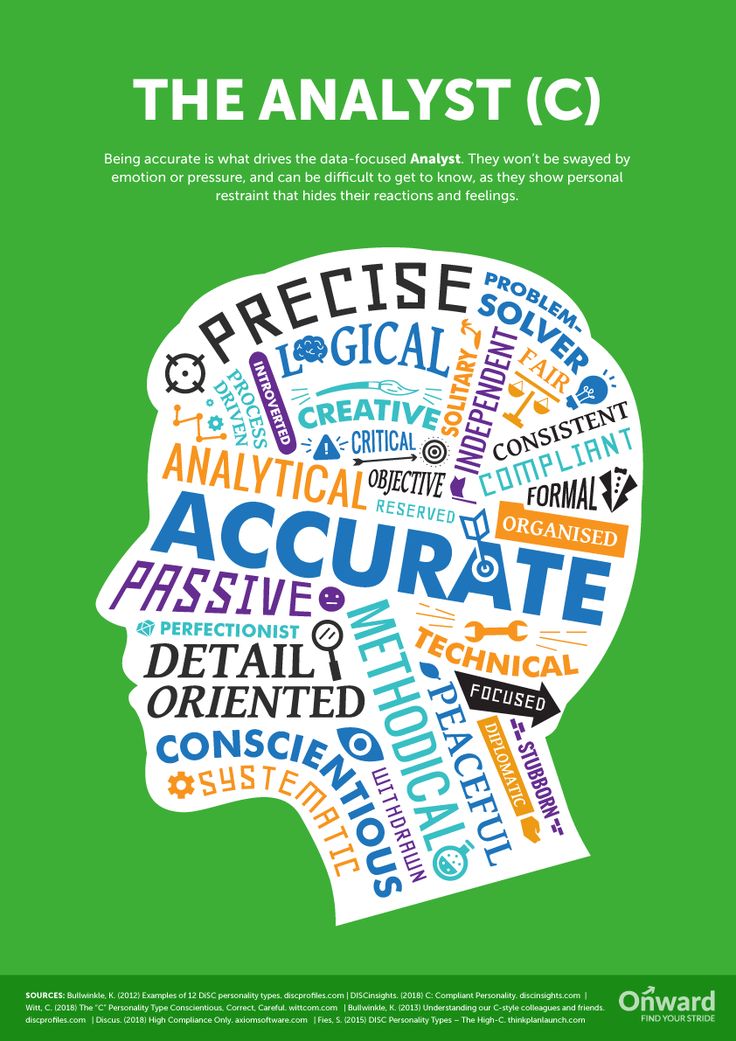

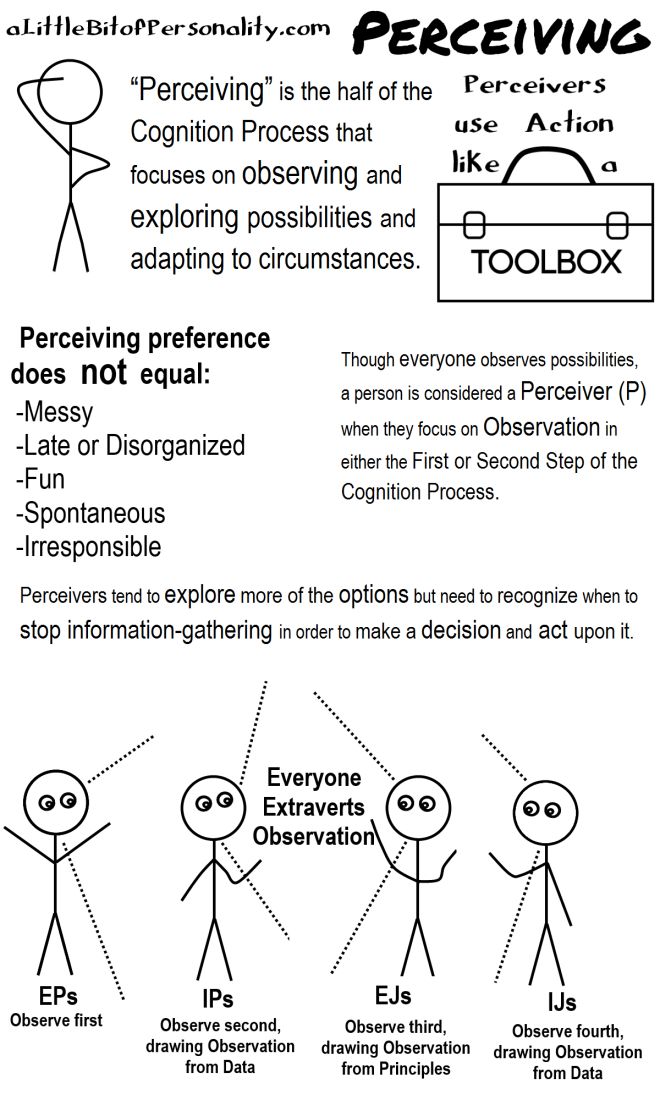

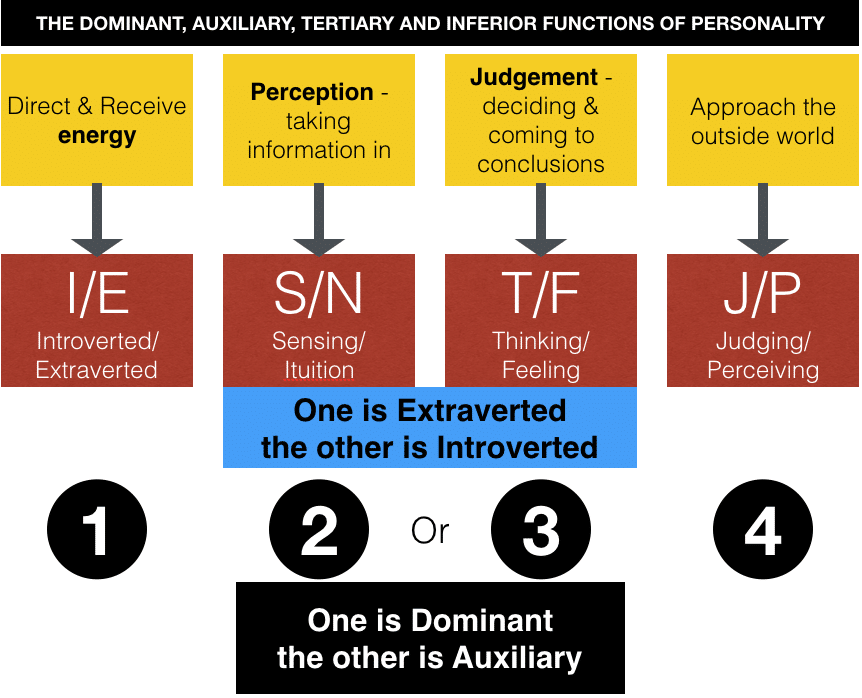

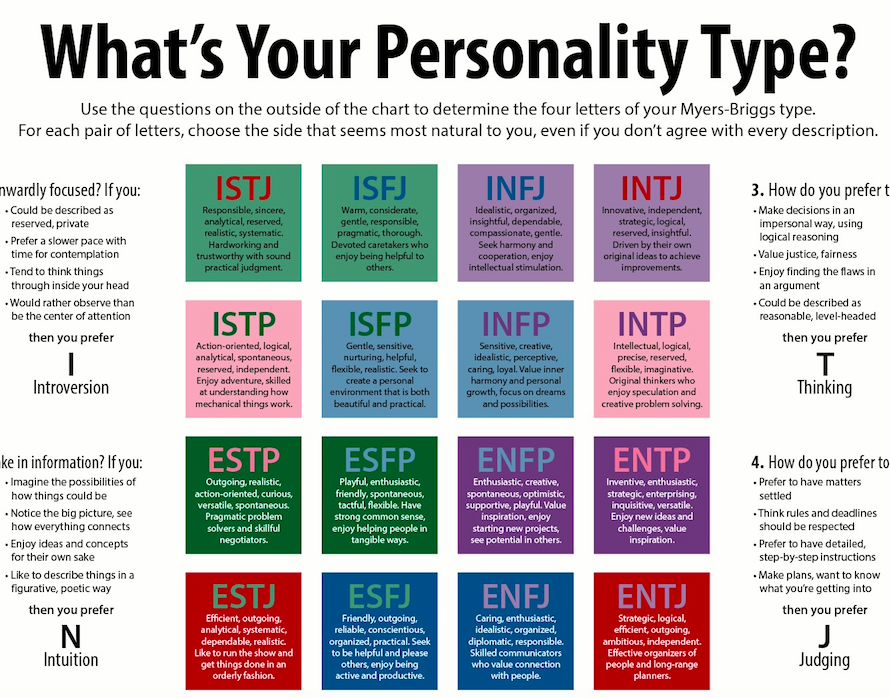

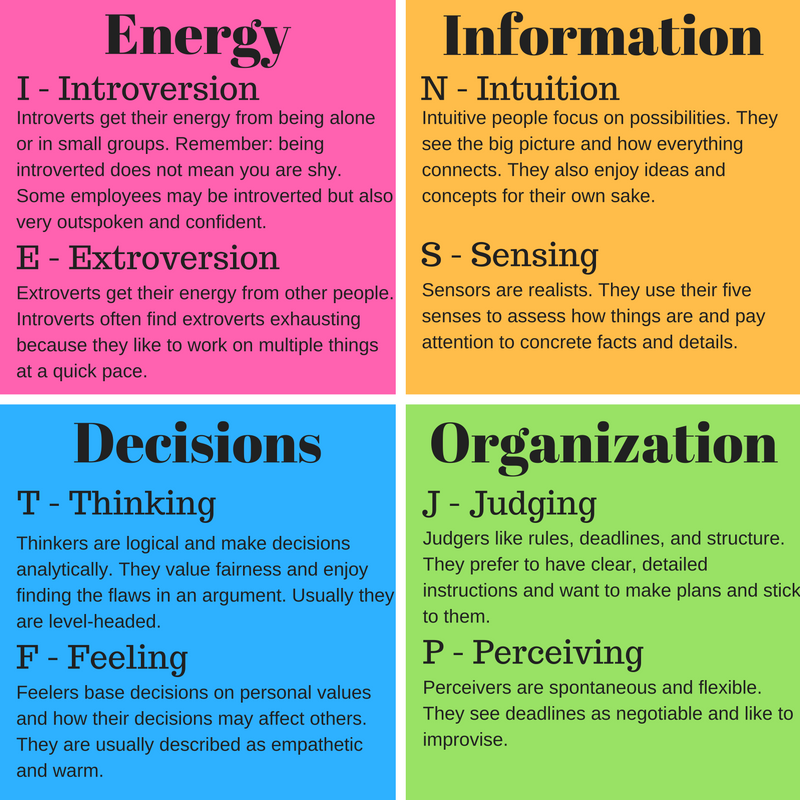

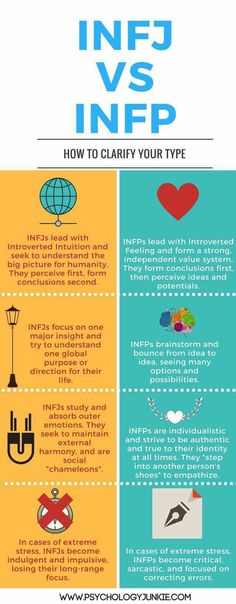

This study was to identify personality correlates of children with a diagnosis of Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder (ADHD). The Jungian Personality Type dimensions primarily considered were Sensing/Intuiting and Perceiving/Judging. A Sensing child is likely to be very present-centered. A Perceiving child tends to be curious and resist order and structure.

Methods

Children attending a general pediatric clinic with a diagnosis of ADHD were eligible to participate. Enrolled children were administered the Murphy-Meisgeier Type Indicator for Children. Binomial tests were performed comparing Perceiving and Sensing personality components to accepted population rates.

Results

Participants (n = 117) were predominantly male (78%) with a median age of 10 years. The Sensing trait (72%) was more prevalent than expected, though prevalence for the Perceiving trait (44%) did not differ from population rates.

Conclusion

Personality types occasioned with the diagnosis of ADHD could be useful in establishing/normalizing treatment regimens and approaches to assist these children and their families better.

Keywords: attention deficit hyperactive disorder, Myers Briggs Type Indicator, personality inventory, pediatrics

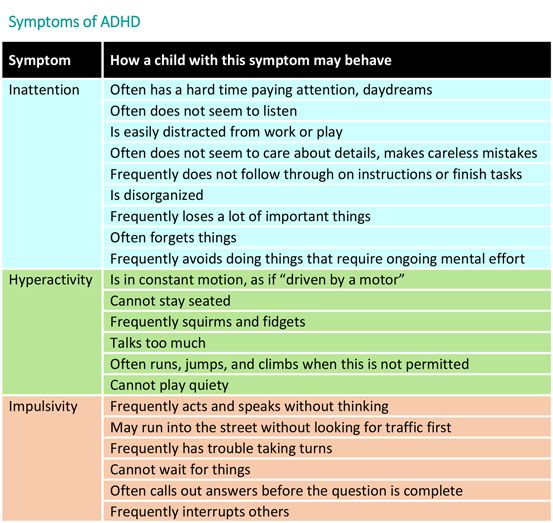

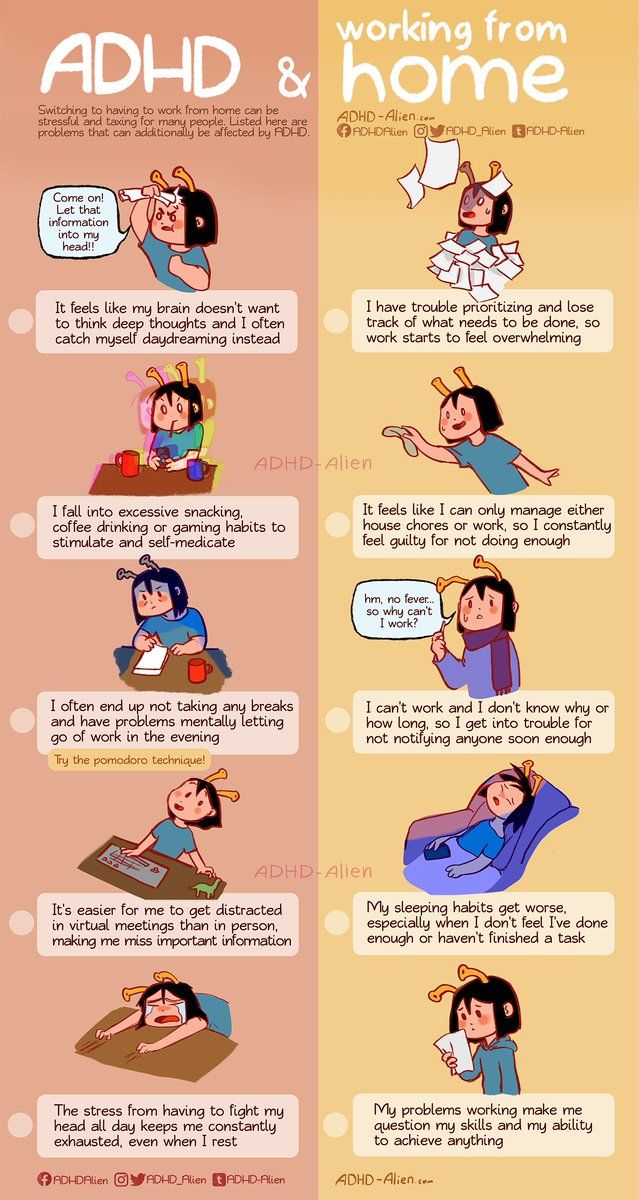

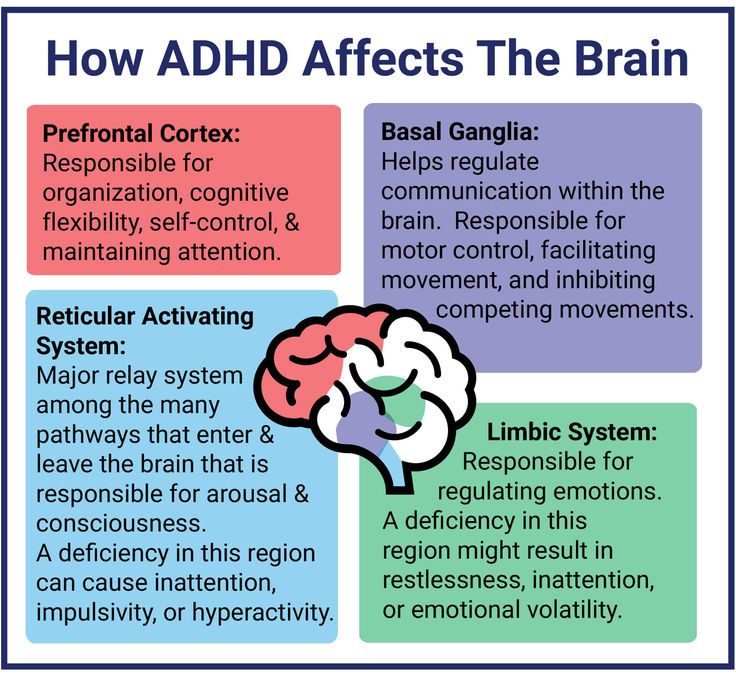

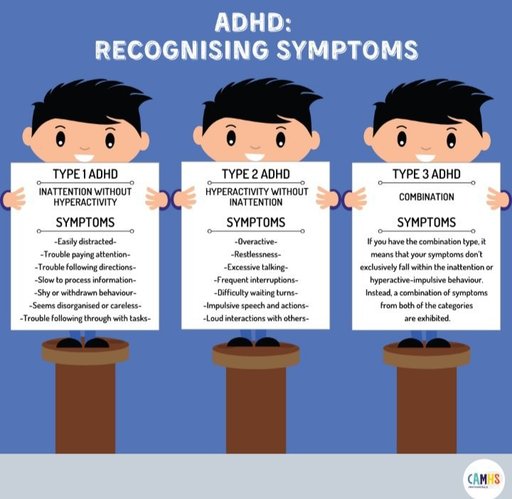

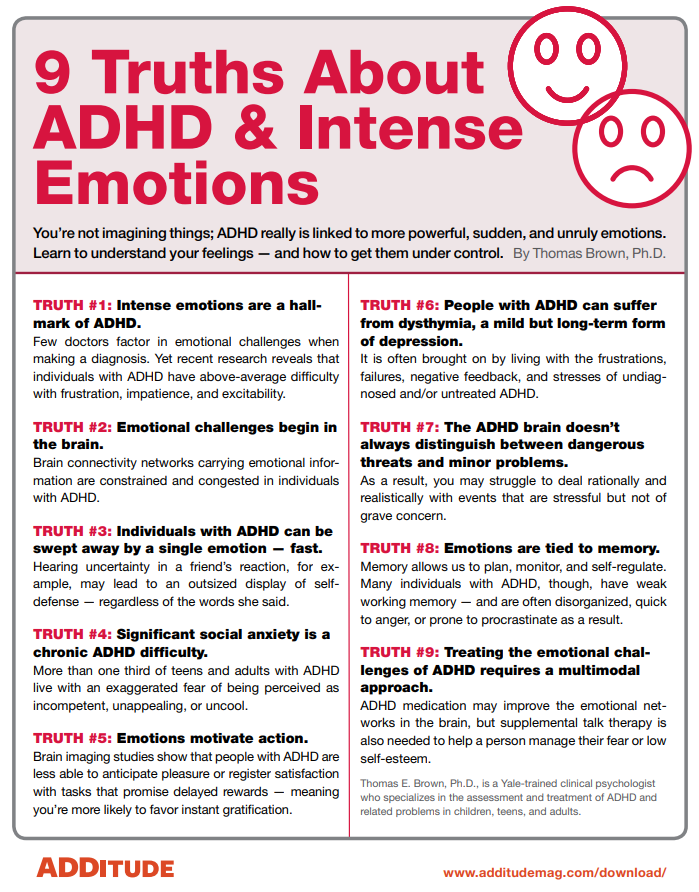

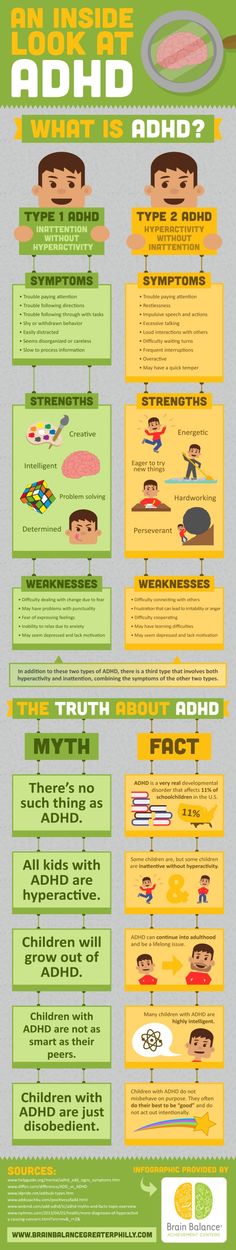

Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a condition characterized by high levels of hyperactivity/impulsivity and inattention that affects up to 10% of school-age children.1 ADHD is associated with chronic functional impairment and increased risk for later psychopathology. 2,3 The specific disorder, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), includes operational criteria targeting both behaviors and deficits in abilities including inattention and communication/impulsivity.4 A search of the literature focused on the relationship of personality characteristics/traits and ADHD revealed a preponderance of research identifying negative aspects associated with the diagnosis, including increased risk of injury, reduced educational achievement, and economic impact.5,6 There was a paucity of research aimed at identifying positive aspects of the diagnosis or ways in which ADHD symptomatology combines favorably with life’s demands. In addition, most research of ADHD and personality focused on adults and not children.

2,3 The specific disorder, as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-V), includes operational criteria targeting both behaviors and deficits in abilities including inattention and communication/impulsivity.4 A search of the literature focused on the relationship of personality characteristics/traits and ADHD revealed a preponderance of research identifying negative aspects associated with the diagnosis, including increased risk of injury, reduced educational achievement, and economic impact.5,6 There was a paucity of research aimed at identifying positive aspects of the diagnosis or ways in which ADHD symptomatology combines favorably with life’s demands. In addition, most research of ADHD and personality focused on adults and not children.

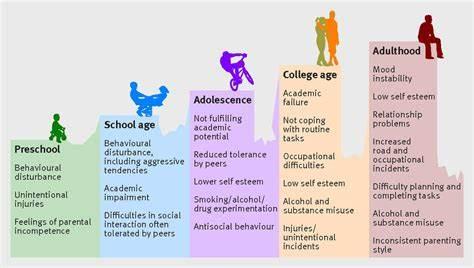

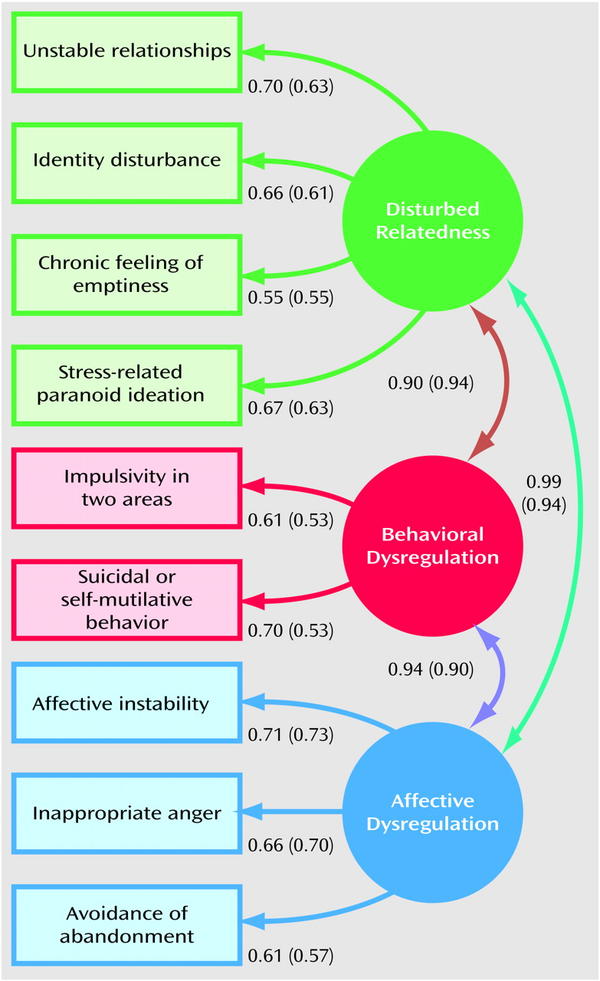

Once thought to disappear with maturation, longitudinal studies have shown ADHD symptoms generally manifest themselves in early childhood, prior to age 12, and can be present in some form throughout adulthood. 6–8 Depending on informant and diagnostic cutoff points, anywhere from 5 to 75% of adults diagnosed as children show significant levels of impairment into adulthood.9 Some have suggested a relationship between disorders of neurocognitive and/or executive function (e.g., ADHD) and subsequent psychopathology (e.g., personality disorders) in adulthood.6,10 However, others have argued the constructs associated with ADHD may be adaptive and represent a positive adjustment to a disorganized and chaotic world.11,12

6–8 Depending on informant and diagnostic cutoff points, anywhere from 5 to 75% of adults diagnosed as children show significant levels of impairment into adulthood.9 Some have suggested a relationship between disorders of neurocognitive and/or executive function (e.g., ADHD) and subsequent psychopathology (e.g., personality disorders) in adulthood.6,10 However, others have argued the constructs associated with ADHD may be adaptive and represent a positive adjustment to a disorganized and chaotic world.11,12

Core symptoms of ADHD may shift in adulthood.13 Behaviors such as difficulty maintaining attention and frequent running around shift to affective lability, lack of anger management skills, emotional over-reactivity, and disorganization. However, coupled with this are concomitant spontaneity, creativity, and responsiveness. Many of the traits associated with creative individuals overlap substantially with behavioral descriptions of ADHD, including higher levels of spontaneous idea generation, mind wandering, daydreaming, sensation seeking, energy, and impulsivity. 14 In addition, persons with diagnosed ADHD may be more likely to convert the exhaustive effects of the disorder into exceptional qualities. Barkley15 noted that children with ADHD actually are able to concentrate intently; this is especially true when the endeavor interests them or provides immediate reinforcement and feedback. Those with an ADHD diagnosis activate higher levels of creative thought and achievement than people without the diagnosis.16,17 This leads to questions concerning what factors contribute to success of those with ADHD and whether they might be functions of personality.

14 In addition, persons with diagnosed ADHD may be more likely to convert the exhaustive effects of the disorder into exceptional qualities. Barkley15 noted that children with ADHD actually are able to concentrate intently; this is especially true when the endeavor interests them or provides immediate reinforcement and feedback. Those with an ADHD diagnosis activate higher levels of creative thought and achievement than people without the diagnosis.16,17 This leads to questions concerning what factors contribute to success of those with ADHD and whether they might be functions of personality.

The key constructs of ADHD often appear to be transient. Hyperactivity often declines by adolescence but problems with attention remain.18 Impulsivity may transform from acting without thinking into executive function issues including problems in self-reflection, planning, and creating a future orientation that anticipates outcomes. However, this also may give way to fearless negotiation of life circumstances that sometimes leads to surprisingly creative solutions. 19 Adults with ADHD also reported occasional bursts of activity leading to adaptability, learning to overcome difficulties, and a moderate risk-taking agenda that allows them to disregard obstacles that prevent others from even exploring new possibilities.17,20

19 Adults with ADHD also reported occasional bursts of activity leading to adaptability, learning to overcome difficulties, and a moderate risk-taking agenda that allows them to disregard obstacles that prevent others from even exploring new possibilities.17,20

Many studies have looked at ADHD through the lens of pathognomonic indicators, such as the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Indicator or the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory II.21,22 ADHD often is associated with depression, anxiety, and lower self-esteem as expressions of increased difficulties at home and in the educational setting.3,8,22,23 Fewer studies have sought to identify the positive aspects of ADHD as capable of influencing adaptive functioning in certain situations and as a precursor to success rather than a pathway to failure. For example, adults with ADHD are nearly four times as likely to be entrepreneurs as their counterparts without the disorder.18

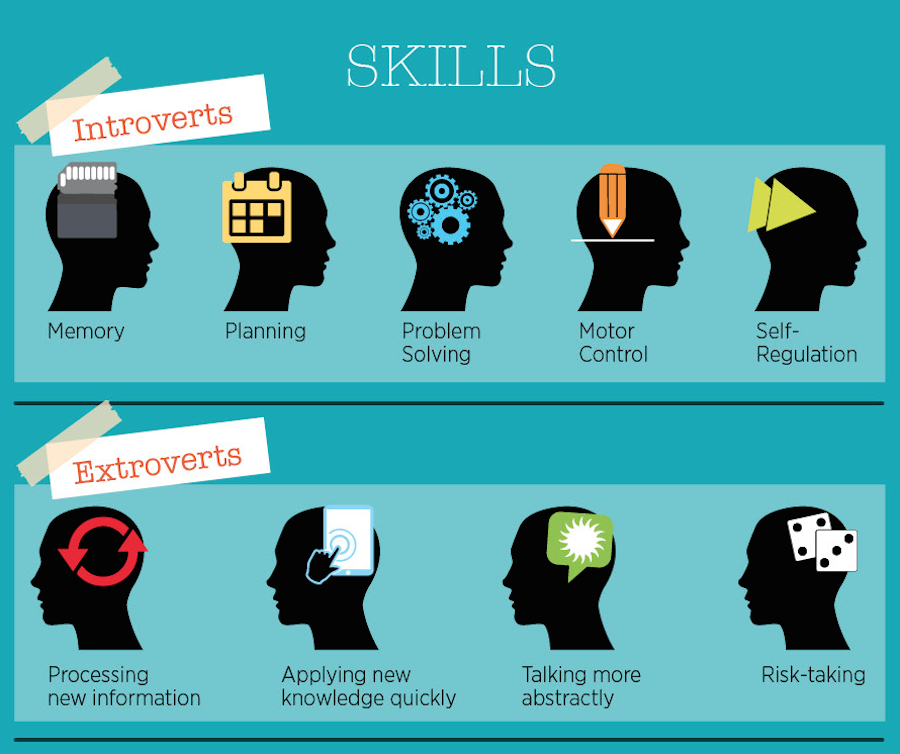

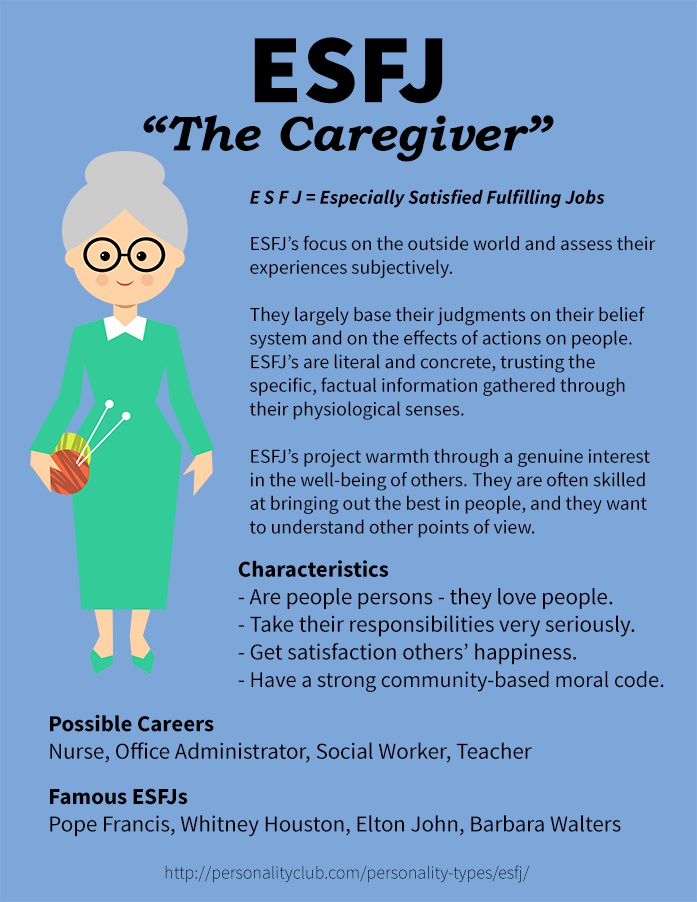

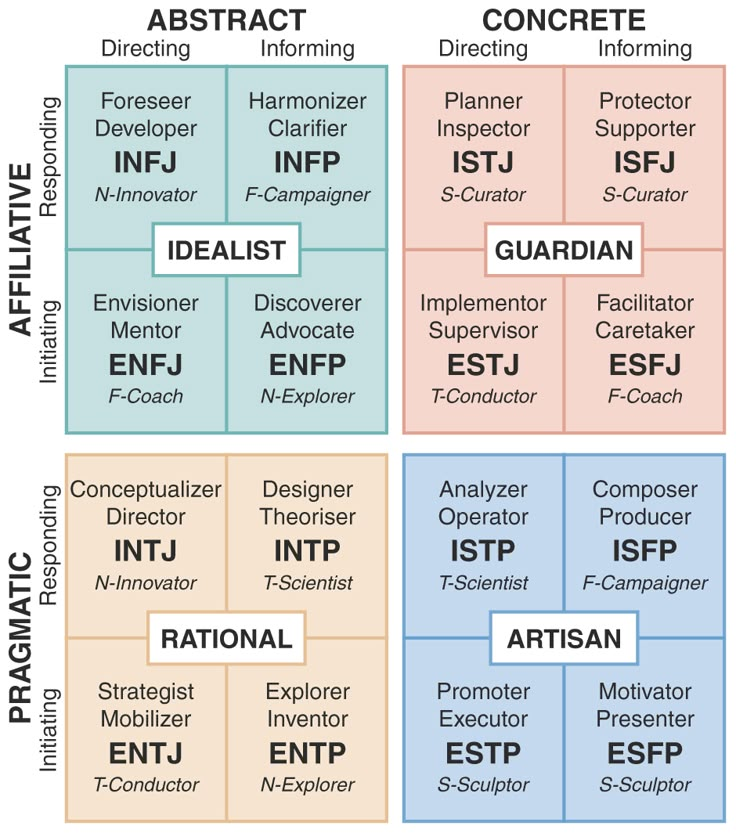

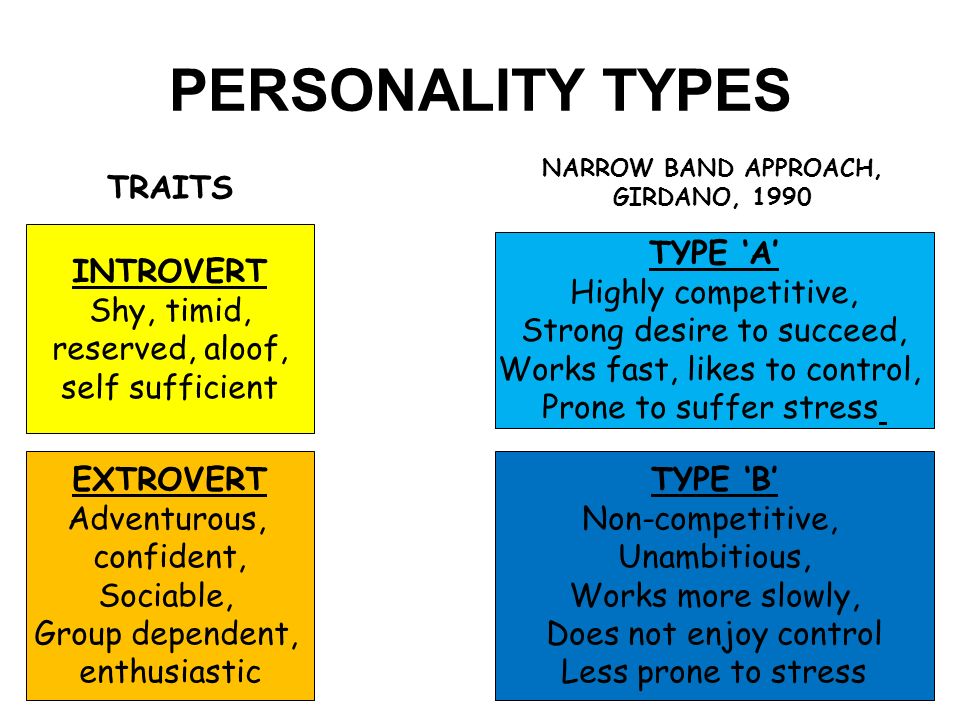

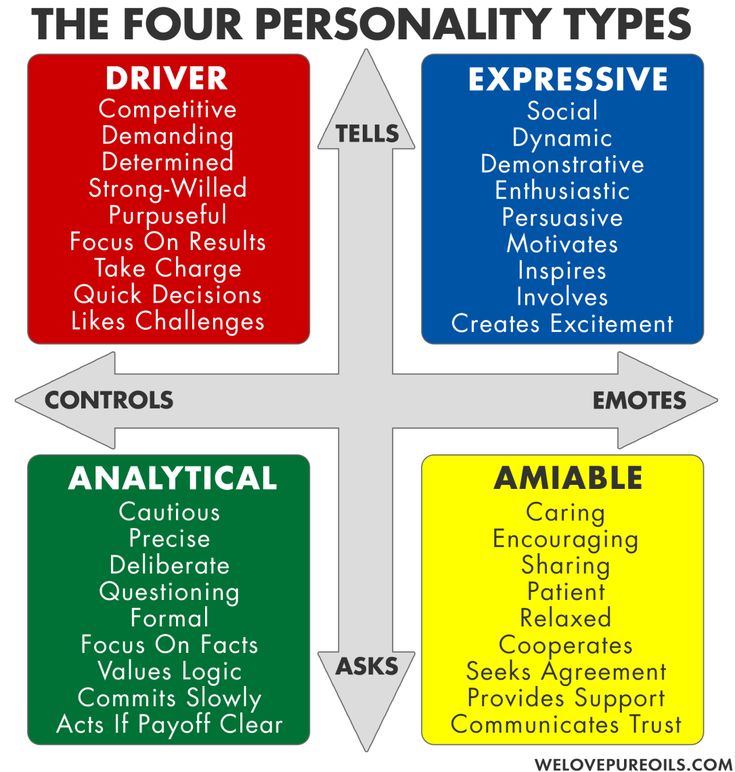

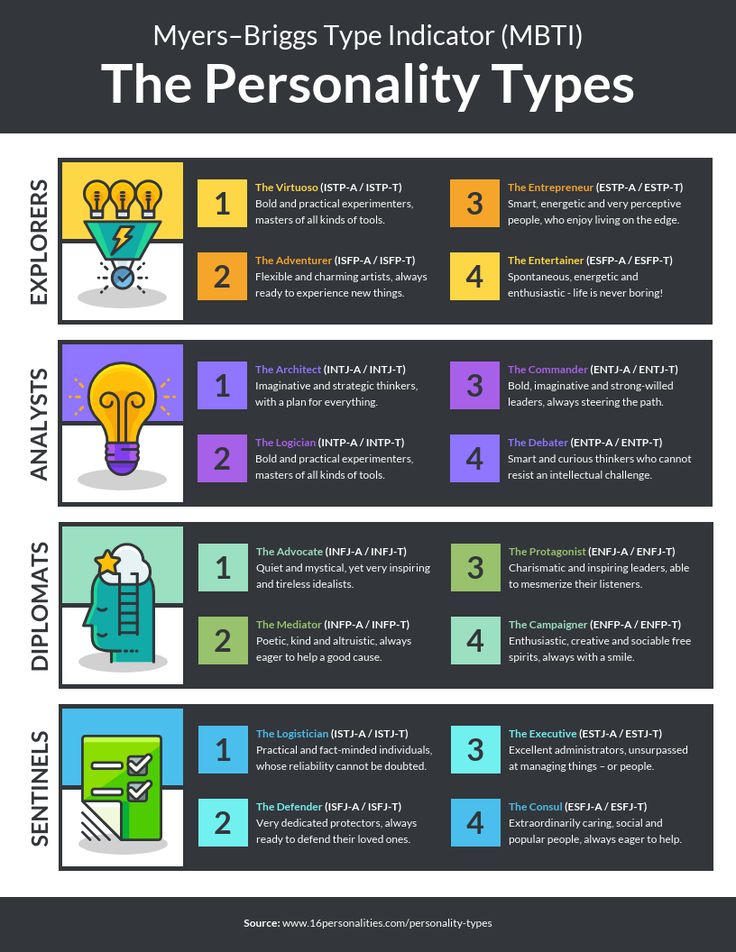

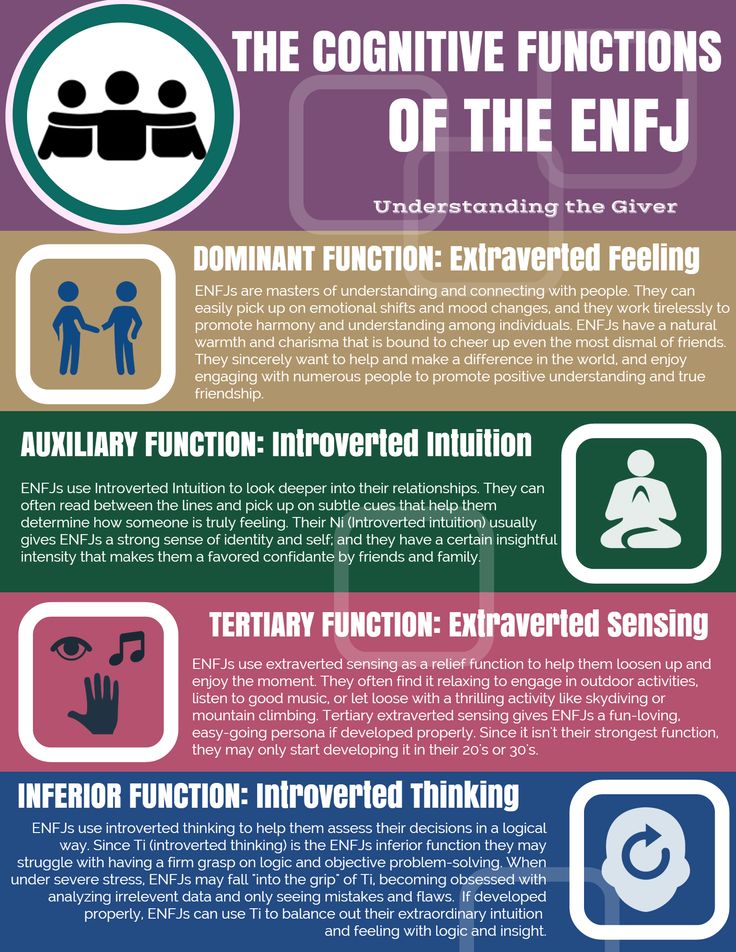

In response to increasing interest in understanding individual personality differences, Carl Jung’s theory of psychological type has been used to develop tools to identify personality indicators. 24 The essence of the theory is that perceived random variation in human behavior is orderly and consistent, being due to certain basic differences in the way people prefer to use their perception and judgment.25 The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) was the first tool developed to investigate Jung’s ideas and measures preferences of the four polar dimensions: Extraversion/Introversion, Sensing/Intuiting, Thinking/Feeling, and Judging/Perceiving. According to type theory, all eight of these preferences are used by each of us but they are not preferred equally. The Murphy-Meisgeier Type Indicator (MMTIC) was developed in an attempt to expand such investigation into the lives of children. The MMTIC reflects normal and adaptive development without any reflection of pathology.26 As each individual grows and develops, predisposed preferences emerge regarding how that person will operate and transact in the world. To date there has been little research looking into the relationship between individual personality type in populations of children with ADHD.

24 The essence of the theory is that perceived random variation in human behavior is orderly and consistent, being due to certain basic differences in the way people prefer to use their perception and judgment.25 The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) was the first tool developed to investigate Jung’s ideas and measures preferences of the four polar dimensions: Extraversion/Introversion, Sensing/Intuiting, Thinking/Feeling, and Judging/Perceiving. According to type theory, all eight of these preferences are used by each of us but they are not preferred equally. The Murphy-Meisgeier Type Indicator (MMTIC) was developed in an attempt to expand such investigation into the lives of children. The MMTIC reflects normal and adaptive development without any reflection of pathology.26 As each individual grows and develops, predisposed preferences emerge regarding how that person will operate and transact in the world. To date there has been little research looking into the relationship between individual personality type in populations of children with ADHD.

The current version of MMTIC has been constructed carefully and the combined reliability and validity statistics demonstrate it is appropriate for and accurately assesses preferences for grades 2 thru 12.26 One particular value of the MMTIC is that it demonstrates clear expectancies of type for the general population. For example, approximately 54% of children would be Judging in their orientation to the world and approximately 46% would be Perceiving. Judging children tend to be planful, organized, orderly, and systematic, whereas Perceiving children tend to be creative, curious, open, flexible, and adaptive, but somewhat scattered in terms of organization. Likewise, expectancies for Sensing and Intuiting would be 57% and 43%, respectively. Sensing children archetypally are present-centered observers who like to do things now, one step at a time, paying attention to details with little regard for the future. Alternatively, Intuiting children tend to look to the future seeking patterns and relationships with a focus on the big picture but often missing details.

The primary research goal was to determine the extent to which an ADHD diagnosis is associated with certain personality preferences. This research explored the possibility that ADHD carries a predisposition to experience the world in certain ways that may complicate the delivery of treatment services and the way in which children with ADHD actually use treatment services. Given the aforementioned descriptions of these personality types, we proposed that Sensing/Perceiving children would not be a natural fit for some educational settings. In addition, their individual preferences may predispose them to be identified as having ADHD. We hypothesized that children with ADHD would be more likely to express the Sensing and Perceiving dimensions on the MMTIC. The Extraversion/Introversion or Thinking/Feeling dimensions were not expected to differ from established population frequencies.

Patients between grade levels 2 and 12 presenting to the practicing psychologist at a general pediatrics clinic in Wichita, KS, who previously were diagnosed with ADHD (all types), were asked to participate in this study. Recruitment occurred between May 2011 and March 2015. For this study, ADHD was defined as confirmed diagnosis by a pediatrician and required additional documentation utilizing the Conner’s Behavior Rating Forms, both Parent and Teacher.27,28

Recruitment occurred between May 2011 and March 2015. For this study, ADHD was defined as confirmed diagnosis by a pediatrician and required additional documentation utilizing the Conner’s Behavior Rating Forms, both Parent and Teacher.27,28

Age, grade level, and gender were collected for all enrolled participants. Each participant was asked to complete the MMTIC. The 43-item assessment tool has documented reliability between .69 and .78 for each of the four scales (Extraversion/Introversion, Sensing/Intuiting, Thinking/Feeling and Judging/Perceiving).26 Children completed the instrument using a computerized assessment (Center for Applications of Psychological Type, Inc; www.capt.org). Basic frequencies were calculated for each of the four dimensions as well as the combinations of all four dimensions. Observed frequencies of individual types were compared to expected values taken from the MMTIC Manual.26

Given the small sample size and skewed distribution of age and grade level, non-parametric tests were used. Age and gender of respondents for each dimension were compared using Mann-Whitney U and Fisher’s exact tests, respectively. Frequencies of MMTIC preferences were compared to expected values using binomial test of proportion. Analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Version 20.0). Significance was defined as p < 0.05. T-test and chi-squared tests were two-tailed. The binomial test of proportion is a one-tailed test. This project was approved by the institutional review board at the Wichita Medical Research and Education Foundation.

Age and gender of respondents for each dimension were compared using Mann-Whitney U and Fisher’s exact tests, respectively. Frequencies of MMTIC preferences were compared to expected values using binomial test of proportion. Analyses were performed using SPSS (IBM SPSS Version 20.0). Significance was defined as p < 0.05. T-test and chi-squared tests were two-tailed. The binomial test of proportion is a one-tailed test. This project was approved by the institutional review board at the Wichita Medical Research and Education Foundation.

All children with a verified diagnosis of ADHD seen by the psychologist were enrolled (n = 117). Children were mostly male (78%), with a median age of 10 (interquartile range [IQR] 8 – 12), and were in the 4

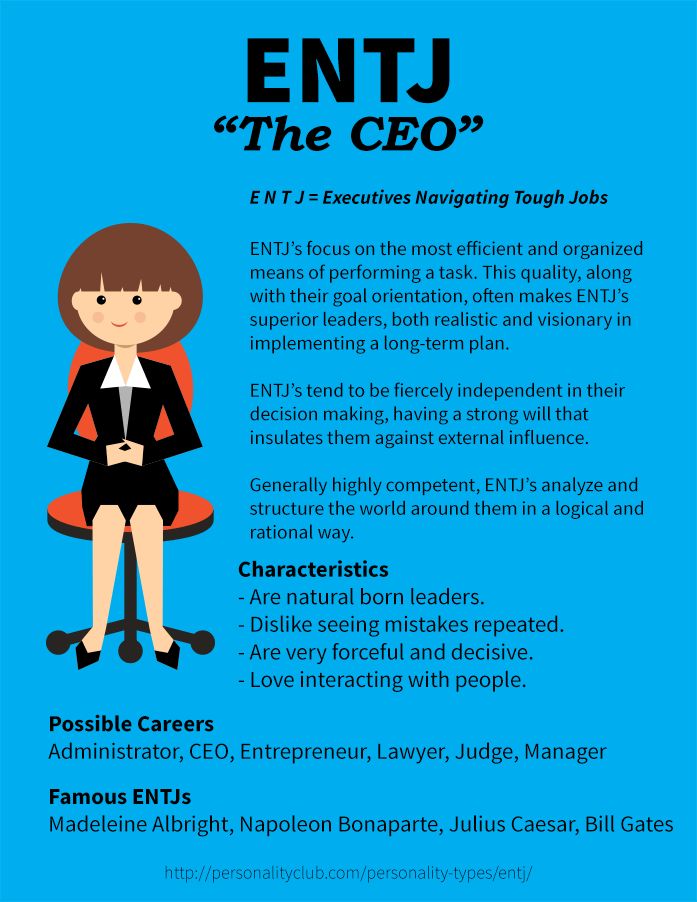

th grade (IQR 3 – 6). The most common 4-type personality indicator was ISFJ (). describes the percent of each personality type who were male and the median age for each type. Age and gender were significantly associated with trait preferences across dimensions (age unassociated with Feeling/Thinking dimension, p = 0. 074, all others unassociated, p > 0.2).

074, all others unassociated, p > 0.2).

Table 1

Distribution of personality types.*

| ISTJ | ISFJ | INFJ | INTJ |

| 5.1% | 20.5% | 5.1% | 0.9% |

| ISTP | ISFP | INFP | INTP |

| 6% | 13. 7% 7% | 3.4% | 3.4% |

| ESTP | ESFP | ENFP | ENTP |

| 2.6% | 4.3% | 5.1% | 5.1% |

| ESTJ | ESFJ | ENFJ | ENTJ |

5. 1% 1% | 14.5% | 4.3% | 0.9% |

Open in a separate window

*Extraversion/Introversion, Sensing/Intuiting, Thinking/Feeling, and Judging/Perceiving.

Table 2

Age and Gender by type

| % Male | Median age | |

|---|---|---|

| Extroversion | 73% | 10 |

| Introversion | 81% | 10 |

| | ||

| Intuiting | 76% | 10 |

| Sensing | 79% | 10 |

| | ||

| Feeling | 76% | 10 |

| Thinking | 82% | 10 |

| | ||

| Perceiving | 75% | 10 |

| Judging | 80% | 10 |

Open in a separate window

When compared to expected averages taken from the MMTIC manual, children in our sample were more likely to exhibit the Sensing preference (72%) than would have been expected (57%; p = 0. 001). No differences were detected in the expression of the Perceiving preference (44%) as compared to the expected 46% (p = 0.334).Differences were detected in both the proportion expressing the Introversion preference (58%; p = 0.001) and the Thinking preference (29%; p = 0.005). Respectively, these are compared to expected frequencies of 43% and 41%.

001). No differences were detected in the expression of the Perceiving preference (44%) as compared to the expected 46% (p = 0.334).Differences were detected in both the proportion expressing the Introversion preference (58%; p = 0.001) and the Thinking preference (29%; p = 0.005). Respectively, these are compared to expected frequencies of 43% and 41%.

The results of this study affirmed our hypothesis that children with ADHD were more likely to be Sensing on the MMTIC, but did not support that they are more likely to exhibit the Perceiving trait. These results presented an intriguing picture of ADHD and personality type that warrants future research, especially at pediatric clinics where ADHD is a relatively common diagnosis. It would be important to see if children with an ADHD diagnosis are indeed more likely to be Sensing in their personality style. Sensing children may live in the present moment without much thinking or worrying about the future and often like real things that are right now. They prefer going step-by-step in a concrete fashion and principally are not interested in theories or big picture generalizations that are usually part of the instructional field of play in any educational system. These children tend to be pragmatic and practical and if the lesson does not make sense to them they will disregard it because the lesson has no place in their worldview. It could be expected that Sensing children would have trouble with an educational system designed to teach big concepts that have little to no real meaning for the practical world they live. Conversely, Intuiting children tend to be quick in their ability to get the major concepts being taught but often miss the details leading to the larger lesson.

They prefer going step-by-step in a concrete fashion and principally are not interested in theories or big picture generalizations that are usually part of the instructional field of play in any educational system. These children tend to be pragmatic and practical and if the lesson does not make sense to them they will disregard it because the lesson has no place in their worldview. It could be expected that Sensing children would have trouble with an educational system designed to teach big concepts that have little to no real meaning for the practical world they live. Conversely, Intuiting children tend to be quick in their ability to get the major concepts being taught but often miss the details leading to the larger lesson.

The Judging/Perceiving dimension is equally intriguing. Judging children tend to be organized and systematic, while Perceiving children tend to be more curious and playful in their approach to the outside world, including education. Children with a Judging preference may value getting things done and often enjoy schedules and routines. Judgers tend to be neat, orderly, and like completing their work on time. They frequently cannot consider playing if they have an assignment due. Perceiving children tend to be far more flexible and like to have time open to do whatever they want whenever they want to do it. They may start lots of projects but have difficulty actually getting anything done. The importance of the spontaneous moment can be a powerful enticer for the Perceiving child. This is precisely why we expected children with ADHD to be inclined to be more Perceiving in their orientation; however, the data in our sample did not support this hypothesis.

Judgers tend to be neat, orderly, and like completing their work on time. They frequently cannot consider playing if they have an assignment due. Perceiving children tend to be far more flexible and like to have time open to do whatever they want whenever they want to do it. They may start lots of projects but have difficulty actually getting anything done. The importance of the spontaneous moment can be a powerful enticer for the Perceiving child. This is precisely why we expected children with ADHD to be inclined to be more Perceiving in their orientation; however, the data in our sample did not support this hypothesis.

There were other incidental findings in this research regarding higher than expected expression of Introversion and Feeling. It may be that these preferences grew in response to the impairments associated with ADHD, for example, difficulty forming and maintaining friendships or heightened sensitivity to educational impediments. However, further research is necessary.

This research pointed to the importance of knowing who the patient is, just as much as knowing what the patient has. The utilization of the MMTIC afforded the opportunity to do just that and to tailor approaches to intervention to fit the personal style of the child. It also allowed the opportunity to think more globally with parents about why a child does what they do, not just in terms of ADHD, but also in terms of who they are as people. This process also suggested where effort needs to be placed in terms of educational interventions and in treatment especially regarding cognitive behavioral approaches. For example, interventions that require a long-term investment and delayed gratification might not bear as much fruit as those devised in a playful, present centered way, with a reward that is immediate rather than delayed.

Perhaps, the more important outcome of this research is the consideration of the personality orientation of the child in addition to a focus on the specific ADHD dimensional criteria. We would suggest that adding the MMTIC to standard ADHD assessment techniques such as behavior rating scales and computer generated tests may create a more complete picture of the child we hope to help.

We would suggest that adding the MMTIC to standard ADHD assessment techniques such as behavior rating scales and computer generated tests may create a more complete picture of the child we hope to help.

The authors would like to thank the staff at KU Wichita Pediatrics. This research was supported by a grant from the Wichita Medical Research and Education Foundation.

1. Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: an updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2014;43(2):434–442. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Murphy K, Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults: Comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr Psychiatry. 1996;37(6):393–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Purper-Ouakil D, Cortese S, Wohl M, et al. Temperament and character dimensions associated with clinical characteristics and treatment outcome in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder boys. Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(3):286–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Compr Psychiatry. 2010;51(3):286–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

5. Küpper T, Haavik J, Drexler H, et al. The negative impact of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on occupational health in adults and adolescents. Int Arch Occup Environ Health. 2012;85(8):837–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Uchida M, Spencer TJ, Faraone SV, Biederman J. Adult outcome of ADHD: An overview of results from the MGH longitudinal family studies of pediatrically and psychiatrically referred youth with and without ADHD of both sexes. J Atten Disord. 2015 Sep 22; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, Fletcher K. The persistence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder into young adulthood as a function of reporting source and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111(2):279–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Miller CJ, Miller SR, Newcorn JH, Halperin JM. Personality characteristics associated with persistent ADHD in late adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36(2):165–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Wasserstein J. Diagnostic issues for adolescents and adults with ADHD. J Clin Psychol. 2005;61(5):535–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Anckarsäter H, Stahlberg O, Larson T, et al. The impact of ADHD and autism spectrum disorders on temperament, character, and personality development. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(7):1239–1244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Hartmann T. Attention deficit disorder: A different perception. Dublin: Newleaf; 1999. [Google Scholar]

12. Thagaard MS, Faraone SV, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Østergaard SD. Empirical tests of natural selection-based evolutionary accounts of ADHD: A systematic review. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2016;28(5):249–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Wender PH. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

14. Issa JP. Encyclopedia of Creativity, Invention, Innovation and Entrepreneurship. New York: Springer; 2013. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Creativity; pp. 128–135. [Google Scholar]

15. Barkley RA. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: The Guilford Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

16. Abraham A, Windmann S, Siefen R, Daum I, Gunturkun O. Creative thinking in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Child Neuropsychol. 2006;12(2):111–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. White HA, Shah P. Creative style and achievement in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pers Individ Dif. 2011;50(5):673–677. [Google Scholar]

18. Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(7):565–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Gilbertson D, Gilbertson D. ADHD or Latent Entrepreneur Personality Type? Mar 31, 2004. http://www.kohutu.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/ADHD.pdf.

20. White HA, Shah P. Training attention-switching ability in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2006;10(1):44–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Holdnack JA, Moberg PJ, Arnold SE, Gur RE, Gur RC. MMPI characteristics in adults diagnosed with ADD: A preliminary report. Int J Neurosci. 1994;79(1–2):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. May B, Bos J. Personality characteristics of ADHD adults assessed with the Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory-II: Evidence of four distinct subtypes. J Pers Assess. 2000;75(2):237–248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Tinney K. Oppositional defiant disorder, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Presentation at Cross Country Education; Wichita, Kansas. 2005. [Google Scholar]

24. Jung CG. Psychological types A revision. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

25. Myers IB, McCaulley MH, Briggs KC. Manual: A guide to the development and use of the Myers-Briggs type indicator. Palo Alto: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

26. Murphy E, Meisgeier CH. MMTIC manual : a guide to the development and use of the Murphy-Meisgeier Type Indicator for Children. Gainesville, FL: Center for Applications of Psychological Type; 2008. [Google Scholar]

27. Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JD, Epstein JN. The revised Conners’ Parent Rating Scale (CPRS-R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26(4):257–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Conners CK, Sitarenios G, Parker JD, Epstein JN. Revision and restandardization of the Conners Teacher Rating Scale (CTRS-R): Factor structure, reliability, and criterion validity. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1998;26(4):279–291. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

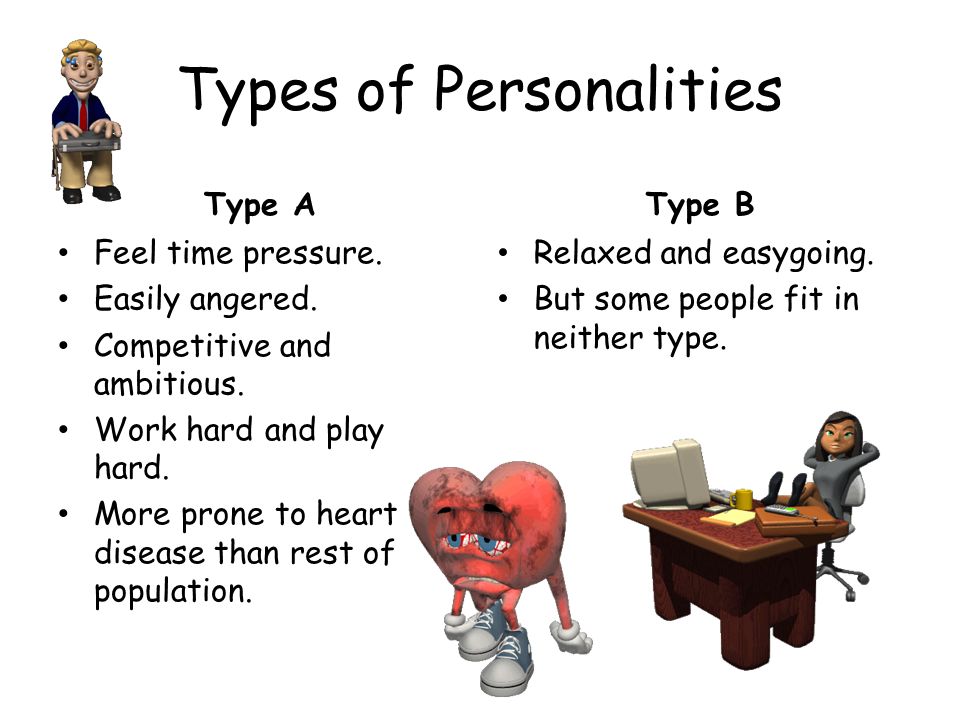

Inhibition and executive functioning in Type A and ADHD boys

Comparative Study

. 2003;57(6):437-45.

2003;57(6):437-45.

doi: 10.1080/08039480310003452.

Lilianne Nyberg 1 , Gunilla Bohlin, Lisa Berlin, Lars-Olof Janols

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, Sweden. [email protected]

- PMID: 14630549

- DOI: 10.1080/08039480310003452

Comparative Study

Lilianne Nyberg et al. Nord J Psychiatry. 2003.

. 2003;57(6):437-45.

doi: 10. 1080/08039480310003452.

1080/08039480310003452.

Authors

Lilianne Nyberg 1 , Gunilla Bohlin, Lisa Berlin, Lars-Olof Janols

Affiliation

- 1 Department of Psychology, Uppsala University, Sweden. [email protected]

- PMID: 14630549

- DOI: 10.1080/08039480310003452

Abstract

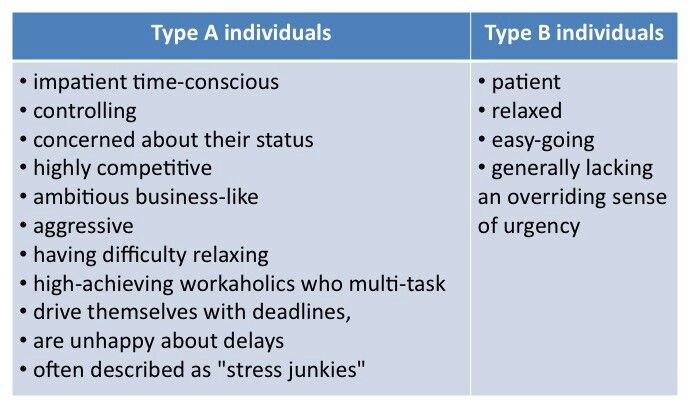

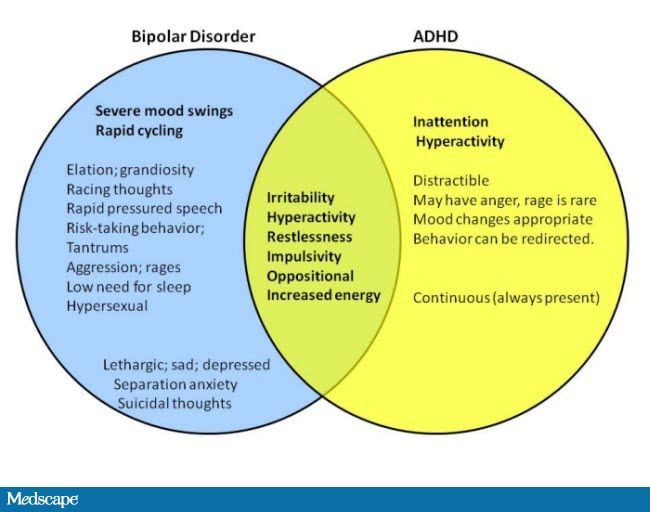

The present study was aimed at clarifying the standing of Type A behavior, as measured by behavioral observations, relative to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), using measures of inhibitory control and executive functioning. The study sample included 20 boys exhibiting Type A behavior, 21 boys exhibiting Type B behavior and 14 boys diagnosed with ADHD, ranging in age from 7 to 12 years. The results of the present study showed that the Type A children differed from Type B children on two time-related variables, response latency and reaction time, in accordance with the view of Type As as time-urgent and impatient. Furthermore, in comparisons with the ADHD group, the Type A boys were found to be superior on several performance tasks, such as Go/no-go omissions, time reproduction, story recall and memory for sequences of hand movements, although similarities between Type A and ADHD boys were evidenced in terms of response latency and reaction time. In other words, although Type A boys were similar to ADHD boys in terms of overt displays of time-urgency and impatience, Type As do not display deficits with regard to executive functioning, of the kind often found when ADHD children are compared with normal controls.

The study sample included 20 boys exhibiting Type A behavior, 21 boys exhibiting Type B behavior and 14 boys diagnosed with ADHD, ranging in age from 7 to 12 years. The results of the present study showed that the Type A children differed from Type B children on two time-related variables, response latency and reaction time, in accordance with the view of Type As as time-urgent and impatient. Furthermore, in comparisons with the ADHD group, the Type A boys were found to be superior on several performance tasks, such as Go/no-go omissions, time reproduction, story recall and memory for sequences of hand movements, although similarities between Type A and ADHD boys were evidenced in terms of response latency and reaction time. In other words, although Type A boys were similar to ADHD boys in terms of overt displays of time-urgency and impatience, Type As do not display deficits with regard to executive functioning, of the kind often found when ADHD children are compared with normal controls. It may thereby be concluded that Type A behavior and hyperactivity/ADHD appear to be well differentiated except with regard to what may be interpreted as impatience. Speculations concerning differing origins of overtly similar characteristics of Type A behavior and ADHD should be considered in future research.

It may thereby be concluded that Type A behavior and hyperactivity/ADHD appear to be well differentiated except with regard to what may be interpreted as impatience. Speculations concerning differing origins of overtly similar characteristics of Type A behavior and ADHD should be considered in future research.

Similar articles

-

[Behavioural inhibition and emotion regulation among boys with ADHD during a go-/nogo-task].

Desman C, Schneider A, Ziegler-Kirbach E, Petermann F, Mohr B, Hampel P. Desman C, et al. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2006;55(5):328-49. Prax Kinderpsychol Kinderpsychiatr. 2006. PMID: 16869480 German.

-

Executive functions: performance-based measures and the behavior rating inventory of executive function (BRIEF) in adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Toplak ME, Bucciarelli SM, Jain U, Tannock R. Toplak ME, et al. Child Neuropsychol. 2009 Jan;15(1):53-72. doi: 10.1080/09297040802070929. Child Neuropsychol. 2009. PMID: 18608232

-

Acute neuropsychological effects of methylphenidate in stimulant drug-naïve boys with ADHD II--broader executive and non-executive domains.

Rhodes SM, Coghill DR, Matthews K. Rhodes SM, et al. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006 Nov;47(11):1184-94. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01633.x. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2006. PMID: 17076758 Clinical Trial.

-

Development of attentional processes in ADHD and normal children.

Gupta R, Kar BR. Gupta R, et al. Prog Brain Res. 2009;176:259-76. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(09)17614-8.

Prog Brain Res. 2009. PMID: 19733762

Prog Brain Res. 2009. PMID: 19733762 -

Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD.

Barkley RA. Barkley RA. Psychol Bull. 1997 Jan;121(1):65-94. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.121.1.65. Psychol Bull. 1997. PMID: 9000892 Review.

See all similar articles

Publication types

MeSH terms

SUBJECT OR NOT SUBJECT? – the topic of a scientific article on psychological sciences read the text of the research paper for free in the CyberLeninka electronic library

Akhmetova Z.A., Tkachenko N.S.

JUNIOR SCHOOLCHILD WITH ATTENTION DEFICIENCY AND HYPERACTIVITY SYNDROME: SUBJECT OR NOT SUBJECT?

Key words: primary school age, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, personality, subject, subjectivity, subjective approach, activity.

Abstract. Primary school age is an important stage in the development of personality, however, even a minimal deviation in the development of psychophysiological functions, such as in children with attention deficit disorder, can significantly hinder the formation of subjectivity. The analysis of the concepts of "subject", "subjectness" was carried out using the method of psychological and historical reconstruction. Various concepts in the application of the subjective approach are considered. It is shown that younger schoolchildren with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder can be considered subjects of activity.

Primary school age is the most important stage in the development of a child's personality, since when they enter school, children enter a new social situation, move to a new way of life, they change their leading activities, the requirements for the level of development of their cognitive, emotional-volitional, motivational-need areas. All this undoubtedly affects the formation of important mental qualities of the personality of a younger student: there is a rapid development of intellectual functions, the nature of mental processes changes, which become more conscious and arbitrary, and the horizons expand. Therefore, it is at primary school age that the foundations are laid for many important mental qualities of a person, which should be used in a timely manner for the further more successful development of students.

Therefore, it is at primary school age that the foundations are laid for many important mental qualities of a person, which should be used in a timely manner for the further more successful development of students.

At the same time, in modern society, there is a growing need to educate a person as an active, creative, valuable in itself, independent, initiative and unique personality, acting as a subject. The study of the process of human development as a subject is carried out within the framework of the subjective approach, which today occupies a special place in psychology and pedagogy. However, at present, the theory of the subjective approach has not been developed enough, the concept of the subject is still at the stage of formation, in the scientific literature there is even a denial of this phenomenon. According to E.A. Sergienko, in domestic psychology, the understanding of the criterion of the subject is considered from the standpoint of acmeological and evolutionary approaches [19]. From the point of view of the acmeological approach, the subject is the pinnacle of personality development (A.V. Brushlinsky, V.V. Znakov, V.A. Petrovsky, K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya, G.V. Zalevsky, A.G. Asmolov , Z. I. Ryabikina and others). In the light of the evolutionary approach, a gradual development of a person as a subject is assumed (E.A. Sergienko, V.I. Slobodchikov, E.I. Isaev, L.I. Bozhovich, B.G. Ananiev, A.L. Zhuravlev, V.V. Selivanov, et al.) [19]. Proceeding from this, the question of whether the younger student acts as a subject or is on the path of becoming his subjectivity is currently open.

From the point of view of the acmeological approach, the subject is the pinnacle of personality development (A.V. Brushlinsky, V.V. Znakov, V.A. Petrovsky, K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya, G.V. Zalevsky, A.G. Asmolov , Z. I. Ryabikina and others). In the light of the evolutionary approach, a gradual development of a person as a subject is assumed (E.A. Sergienko, V.I. Slobodchikov, E.I. Isaev, L.I. Bozhovich, B.G. Ananiev, A.L. Zhuravlev, V.V. Selivanov, et al.) [19]. Proceeding from this, the question of whether the younger student acts as a subject or is on the path of becoming his subjectivity is currently open.

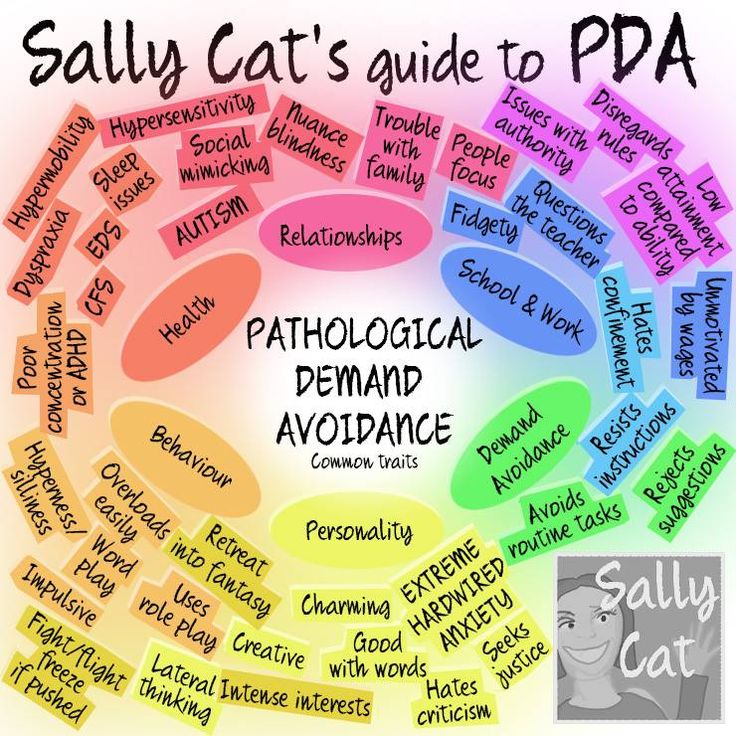

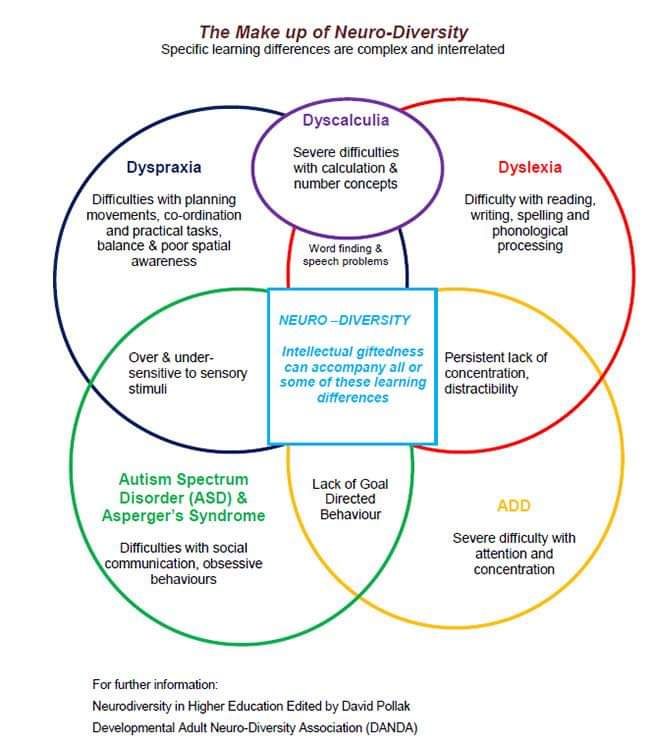

Domestic and foreign researchers in the field of pedagogy and psychology, as well as in the field of psychophysiology and neuropsychology, tend to believe that even a minimal lag or deviation in the development of psychophysiological functions can significantly complicate the child's personal development, thereby inhibiting the formation of his subjectivity. One such developmental disorder is Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). This syndrome usually begins to manifest itself in childhood, it is characterized by such difficulties as a low level of voluntary attention, hypermobility, disinhibition, and difficulty in controlling impulsivity.

This syndrome usually begins to manifest itself in childhood, it is characterized by such difficulties as a low level of voluntary attention, hypermobility, disinhibition, and difficulty in controlling impulsivity.

The problem of ADHD today has a rather high social significance. Firstly, ADHD is characterized by a high frequency of manifestations among children in Russia - up to 47

peppgogichesniy ZhYRNPL SLSHNORTOSTPNN N 5 (84). R019 av§3§аЁ

% [9]. In the Kyrgyz Republic (KR), there are no data on the prevalence of ADHD, but it is assumed that ADHD occurs quite often in this country as well. This can be indirectly judged by the results of a comparative analysis of the data of the state statistics of Russia and Kyrgyzstan, concerning the socio-economic factors of ADHD [2]. Secondly, ADHD in children often leads to behavioral disorders, learning difficulties [8], maladaptation to school [9]. In addition, children with ADHD are characterized by shifts in the activity of mental functions:

In the cognitive sphere, in particular in perceptual activity, poor perception of the shape of objects is possible [11], as well as inaccurate perception of letters and numbers, so it is more difficult for such children to master reading and letter [7]; characterized by a decrease in the amount of RAM, long-term memory suffers [4]. All children with ADHD have attention deficits [8], manifested in the inability to concentrate for a long time on any activity, lack of attention [13], impaired supportive attention [17]. Despite the fact that children with ADHD have an average or even above average IQ [4], their thinking capacity is reduced. 30-60% of children with ADHD have speech disorders: many of these children have difficulty understanding verbal instructions, emotions and humor [8], some students are characterized by impaired written language (dysgraphia) [7].

All children with ADHD have attention deficits [8], manifested in the inability to concentrate for a long time on any activity, lack of attention [13], impaired supportive attention [17]. Despite the fact that children with ADHD have an average or even above average IQ [4], their thinking capacity is reduced. 30-60% of children with ADHD have speech disorders: many of these children have difficulty understanding verbal instructions, emotions and humor [8], some students are characterized by impaired written language (dysgraphia) [7].

In the emotional-volitional sphere, disorders are manifested in excessive excitability, impulsivity, irascibility, delayed emotional development [23], increased anxiety [8; 13], depression [4; 13], irritability, emotional instability [8]. In the motivational sphere in children with ADHD, such features were revealed as a lack of interest in systematic, attention-demanding activities, low activity in purposeful activities [4].

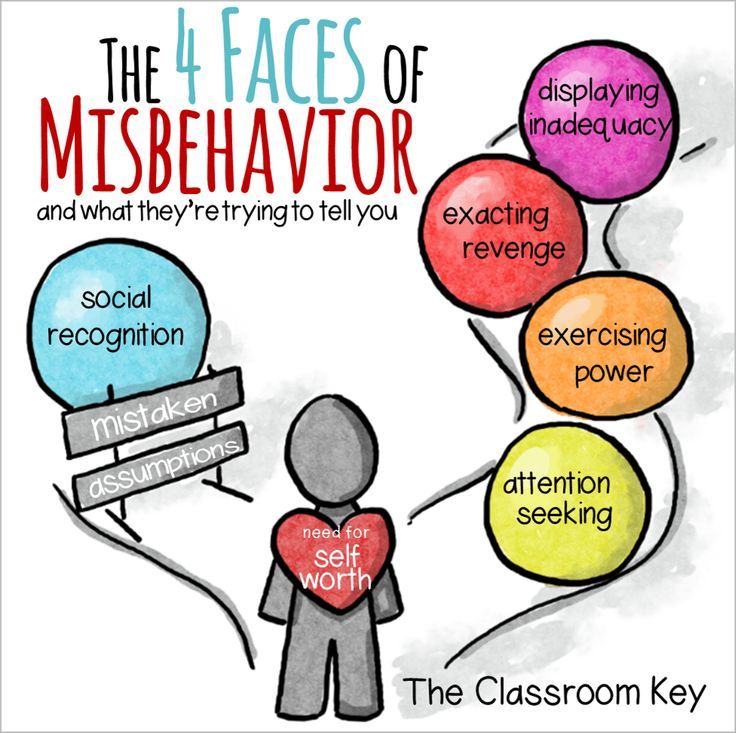

Behaviorally, children with ADHD are usually bully [8], stubborn and disobedient; they are characterized by negativism [7], low self-esteem [4; 7; eight; 11] and pronounced aggressiveness [4; eight; eleven; 17], risk appetite [13], difficulties in social adaptation [13]. In relation to peers, hyperactive children are usually hostile, demanding, selfish [4], experience difficulties in interacting with other children, do not always know how to sympathize and empathize [4; 13].

In relation to peers, hyperactive children are usually hostile, demanding, selfish [4], experience difficulties in interacting with other children, do not always know how to sympathize and empathize [4; 13].

All these manifestations, characteristic of children with ADHD, cannot but complicate the formation of subjectivity at primary school age. In this regard, we have set a goal to find out: “Can a junior student with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder be considered a subject of activity?”

Some help in resolving this issue can be provided by the method of psychological-historical reconstruction, which allows, when a scientist moves into the past, to study the information he is interested in extracted from historical sources, which relate to the psychological phenomenon under consideration, and explain them from the standpoint of modern scientific thinking [12]. From this it follows that understanding the subjective approach in its modern form requires us to move into the information space of the past.

The concept of "subject" arose at the very beginning of philosophical thought. In the era of antiquity, the concept of the subject was understood as hidden under any physical entity, but constituting the basis of all that exists: all inanimate nature, plants and animals, as well as man, were considered as subjects. In the early Middle Ages, all things were also considered subjects, but thanks to the development of Christian teaching, now the basis of everything that exists is the creation of God: every thing, including man, being 9problems of modern psychology and pedagogy

subjects created by God. For this reason, all subjects are responsible to God. This is where the formula of Christian thinking comes from: “There is no subject without an Object” [6].

In the philosophical thought of modern times, the concept of "subject" has completely changed. The well-known thesis of R. Descartes: “I think, therefore I exist”, reveals the essence in a new way, presented through the consciousness of man. As we can see, a person becomes the only subject, and all the rest, unable to think, turn into objects that oppose the subject that cognizes them. So, the formula of the New Age was the statement: "There is no object without a subject." In Hegel's philosophy, which gives rise to all modern philosophical currents, the subject, on the way of its formation, is subordinate to a higher essence - the Absolute. According to Hegel, not only man, but also animals and plants are subjects, but the subject is fully manifested in a conscious being, therefore only man is a complete subject.

As we can see, a person becomes the only subject, and all the rest, unable to think, turn into objects that oppose the subject that cognizes them. So, the formula of the New Age was the statement: "There is no object without a subject." In Hegel's philosophy, which gives rise to all modern philosophical currents, the subject, on the way of its formation, is subordinate to a higher essence - the Absolute. According to Hegel, not only man, but also animals and plants are subjects, but the subject is fully manifested in a conscious being, therefore only man is a complete subject.

Within the framework of dialectical materialism, one of the representatives of which is F. Engels, the concept of the subject is associated with activity; another, no less famous representative, K. Marx, subordinates the human subject to society, while the individual is a subject to the extent that he masters the tools of social, subject-practical activity. [6]

The concept of the subject in Western psychology of the twentieth century is revealed through such categories as “need for self-affirmation” (A. Adler), “self” (K. Jung), “identity” (E. Erickson), “self-actualization” (A. Maslow), “personal growth from within” (K. Rogers), “search for meaning” (V. Frankl) and others [21]. According to L.I. Antsyferova, in the psychoanalytic theories of Western psychologists A. Adler, A. Maslow, K. Rogers, K. Jung, K. Horney and others, the concept of the subject occupies one of the central positions. For these authors, a person as a subject personifies the initiating principle, the creator of his life, the reason for his interaction with the world; he strives for self-development [1]. Thus, V. Frankl emphasized that a person as a subject manifests itself, first of all, in activity directed not at his inner, but at the external world, in which situations, their values and meaning are revealed to the subject [10].

Adler), “self” (K. Jung), “identity” (E. Erickson), “self-actualization” (A. Maslow), “personal growth from within” (K. Rogers), “search for meaning” (V. Frankl) and others [21]. According to L.I. Antsyferova, in the psychoanalytic theories of Western psychologists A. Adler, A. Maslow, K. Rogers, K. Jung, K. Horney and others, the concept of the subject occupies one of the central positions. For these authors, a person as a subject personifies the initiating principle, the creator of his life, the reason for his interaction with the world; he strives for self-development [1]. Thus, V. Frankl emphasized that a person as a subject manifests itself, first of all, in activity directed not at his inner, but at the external world, in which situations, their values and meaning are revealed to the subject [10].

It is known that the category of the subject was most fully developed in Soviet psychology, the founder of the principle of the subjective approach is S.L. Rubinstein (first quarter of the 20th century). Understanding the subject as a way for a person to realize his human essence in the world, as an active principle, as an organizer of his own being, changing reality thanks to his capabilities, S.L. Rubinstein considered the concept of "subject" as an explanatory principle of human life [6], [14]. The scientist, in contrast to the dialectical materialism dominant at that time, convincingly showed that the object is distinguished only by the subject within being in the course of communication and activity, therefore, without a subject, there is no object. At the same time, S.L. Rubinstein emphasized that, despite the fact that being and things in it exist independently of the subject, a thing can become an object if the subject enters into a relationship with it, then the thing becomes an object of action or cognition for the subject. Therefore, the main idea of S.L. Rubinshtein is that people (and their psyche) are formed and developed due to their activity [16].

Understanding the subject as a way for a person to realize his human essence in the world, as an active principle, as an organizer of his own being, changing reality thanks to his capabilities, S.L. Rubinstein considered the concept of "subject" as an explanatory principle of human life [6], [14]. The scientist, in contrast to the dialectical materialism dominant at that time, convincingly showed that the object is distinguished only by the subject within being in the course of communication and activity, therefore, without a subject, there is no object. At the same time, S.L. Rubinstein emphasized that, despite the fact that being and things in it exist independently of the subject, a thing can become an object if the subject enters into a relationship with it, then the thing becomes an object of action or cognition for the subject. Therefore, the main idea of S.L. Rubinshtein is that people (and their psyche) are formed and developed due to their activity [16].

Ideas S.L. Rubinstein was developed by his students - K. A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya and A.V. Brushlinsky. So, according to K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya, only the individual who is able to consciously build his life activity can be considered a subject, nevertheless, the author agrees with Hegel’s concept of the development and formation of the subject [14].

A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya and A.V. Brushlinsky. So, according to K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya, only the individual who is able to consciously build his life activity can be considered a subject, nevertheless, the author agrees with Hegel’s concept of the development and formation of the subject [14].

peppgogichesny ZhYRNPL SLSHNORTOSTPNP N 5(84). J019 av §3§аЁ

According to A.V. Brushlinsky, the category “subject” can act as a promising theoretical basis for the integration of various directions and trends in psychological science [6]. For A.V. Brushlinsky, as well as for S.L. Rubinshtein, the main characteristic of the subject is activity, the leading form of which is human activity. In considering the category of "subject" A.V. Brushlinsky uses a systematic approach, according to which a person as a subject is a system in unity with its cognitive functions, mental properties and states [14]. The key idea for our study is the idea of A.V. Brushlinsky that the subject is only the person who is at the highest personal level of development of activity, communication, integrity, and so on. At the same time, a person is not born, but becomes a subject, approximately from the age of 7-10 years - during the period of mastering the simplest concepts [3]. Agreeing with V.V. Davydov, A.V. Brushlinsky argues that the formation of the rudiments of elementary theoretical thinking in younger schoolchildren is one of the most important stages in the development of a person as a subject. Thus, according to A.V. Brushlinsky, a child at primary school age can already be considered a subject.

At the same time, a person is not born, but becomes a subject, approximately from the age of 7-10 years - during the period of mastering the simplest concepts [3]. Agreeing with V.V. Davydov, A.V. Brushlinsky argues that the formation of the rudiments of elementary theoretical thinking in younger schoolchildren is one of the most important stages in the development of a person as a subject. Thus, according to A.V. Brushlinsky, a child at primary school age can already be considered a subject.

V.V. Znakov, a student of A.V. Brushlinsky, believes that the psychology of the subject, which has reached its dawn within the framework of the post-non-classical paradigm, is a fundamental area in modern psychology [10]. According to V.V. Znkov, the subject of the psychology of the subject (and the psychology of human existence arising from it) are such problems that can be solved not only by using natural science methods, but also humanitarian ones, therefore one of the priority problems of the psychology of human existence is the problem of humanism and humanistic thinking. In this regard, the scientist, who is in the position of the psychology of human existence, is more interested not in mental processes or properties, but in the specifics of the understanding of the world by the subject, that is, semantic formations expressing the value attitude of the subject to the world. In other words, the world for a person appears as the subject sees it, while the idea of the world also depends on the methods of cognition used by the subject [10].

In this regard, the scientist, who is in the position of the psychology of human existence, is more interested not in mental processes or properties, but in the specifics of the understanding of the world by the subject, that is, semantic formations expressing the value attitude of the subject to the world. In other words, the world for a person appears as the subject sees it, while the idea of the world also depends on the methods of cognition used by the subject [10].

For V.V. Significant in the professional activity and communication of the teacher, the priorities are those values that are aimed at the development, education and upbringing of the student, as well as at becoming him as a person. From this point of view, the subject of study of pedagogy and pedagogical psychology should be the value-semantic sphere of the personality of students, primarily their ways of understanding reality and the meaning of life [10]. As you know, one of the main mental neoplasms of primary school age is reflection [5], according to V. V. Znkov, the development of this particular mental phenomenon is a factor in changing a person and forming his subjective qualities [10]. Despite the fact that V.V. Znakov adheres to the point of view that the subject is the pinnacle of personality development; at the same time, he is a supporter of the idea of the formation of subjectivity in the process of gaining new experience in specific situations and life events [10].

V. Znkov, the development of this particular mental phenomenon is a factor in changing a person and forming his subjective qualities [10]. Despite the fact that V.V. Znakov adheres to the point of view that the subject is the pinnacle of personality development; at the same time, he is a supporter of the idea of the formation of subjectivity in the process of gaining new experience in specific situations and life events [10].

In Russian science, along with the category “subject”, the concept of “subjectness” is widely used. In domestic psychology, subjectivity is most often understood as a special quality of a person, which is associated with active transformative activity; as a property of the individual, associated with the attitude towards oneself as an agent, as a systemic property of individuality; as a system of qualities that make an individual a subject; as a quality of a person, which consists in the ability to withstand external and internal obstacles that hinder the realization of her interests; as a way of being a person, 9problems of modern psychology and peapgogy

being the subject of life; as the ability to make changes in the surrounding world and in oneself [21].

In developmental psychology, the subjective approach is implemented by V.I. Slobodchikov and E.I. Isaev. It, according to scientists, is of fundamental importance for developmental psychology, since, on the one hand, in psychological cognition, the object coincides with the subject, and on the other hand, the subject and object of cognition are equal participants in the cognition process. Consequently, any study is a dialogue between two independent subjects [20]. According to V.I. Slobodchikova and E.I. Isaev, a person as a subject, from the point of view of the subjective approach, always appears as a psychological and spiritual uniqueness and originality, therefore, biological and sociocultural factors alone cannot determine the process of mental development and the formation of a person as a person. The authors propose to introduce into the psychology of human development the idea of his self-development. According to V.I. Slobodchikov and E.I. Isaev, a person in his internal development goes through five stages of subjectivity. In this concept, primary school age marks the beginning of the third stage of subjectivity - personalization, at which the teacher becomes the child's partner [20]. At this stage, the child first begins to realize himself as the creator of his own life. On the one hand, he has the ability for self-development, and on the other hand, his personality has not yet reached inner freedom. At the same time, V.I. Slobodchikov emphasizes that the process of self-development begins with the beginning of a person's life and unfolds within it; but sometimes a person for many years and even all his life may not be a subject [20].

In this concept, primary school age marks the beginning of the third stage of subjectivity - personalization, at which the teacher becomes the child's partner [20]. At this stage, the child first begins to realize himself as the creator of his own life. On the one hand, he has the ability for self-development, and on the other hand, his personality has not yet reached inner freedom. At the same time, V.I. Slobodchikov emphasizes that the process of self-development begins with the beginning of a person's life and unfolds within it; but sometimes a person for many years and even all his life may not be a subject [20].

According to T.P. Voitenko, in the 80-90s of the twentieth century, the conditions under which the subject position is formed were actively studied. The authors who developed the theory of learning activity made the greatest contribution to the development of this problem: D.B. Elkonin, V.V. Davydov, V.I. Slobodchikov, G.A. Zuckerman, E.D. Bozhovich, M.R. Bityanova and others who associated the concept of "subjective position of a schoolchild" with learning activities [6].

O.V. Suvorova, exploring the development of subjectivity in the transition from senior preschool to younger school age, identifies three levels of development of the child's subjectivity: pre-subjective, pre-subjective and pro-subjective. As indicators of the development of the levels of subjectivity of the child, O.V. Suvorova highlights the nature of motivation, the level of claims, the nature of self-esteem, the type of self-regulation and cooperation with peers. The author points out that during the transition from preschool to primary school age, development follows the path of internalization: from reactive to active behavior; from reproductive to creative action; from external motivation to internal; from external control to internal; from dependent behavior to autonomy [22]. That is, O.V. Suvorova adheres to an evolutionary approach, in which the formation of subjectness is seen as a process of its gradual deployment.

According to O.G. Selivanova [18], the formation of the student's subjectivity, reflected in the ability to set and achieve the goals of self-knowledge and self-realization, is an important condition for the successful development of the student's personal and social maturity in the learning process. In her opinion, the structure of the student's subjectivity includes the following components, which are at the same time the criteria for the formation of the student's subjectivity in educational activities: cognitive (knowledge about oneself and the world around), axiological (a system of value relations to oneself, society, nature, activity), activity (a set of skills manage your own learning). So for O.G. Selivanova, the formation of the student's subjectivity occurs in the process of setting the goals of educational activity and achieving them, while the student in cognitive activity begins to better understand himself and his needs, as well as opportunities to transform himself and the world around him [18].

In her opinion, the structure of the student's subjectivity includes the following components, which are at the same time the criteria for the formation of the student's subjectivity in educational activities: cognitive (knowledge about oneself and the world around), axiological (a system of value relations to oneself, society, nature, activity), activity (a set of skills manage your own learning). So for O.G. Selivanova, the formation of the student's subjectivity occurs in the process of setting the goals of educational activity and achieving them, while the student in cognitive activity begins to better understand himself and his needs, as well as opportunities to transform himself and the world around him [18].

peppgogichesny ZhYRNPL SLSHNORTOSTPNP N 5(84). J019 av §3§аЁ

In line with our problem concerning children of primary school age with ADHD, the following views are close to us. For example, N.Yu. Shuvaeva argues that by the beginning of entering school, the subjective qualities of a younger student are already partially formed in the family [25]. I.S. Yakimanskaya, being a supporter of student-centered learning, argues that the student initially, even before entering school, is the subject - the bearer of a unique subjective experience, and does not become the subject of learning in the process of learning activities. [26]. In the light of these statements, despite deviations in the development of psychophysiological functions, disorders in the development of cognitive, emotional and behavioral spheres that hinder the formation of subjectivity at primary school age, we believe that every child with ADHD, upon entering school, has his own unique experience gained in family or preschool institution, is an original, self-valuable personality, which means that already at this stage of its development it can be considered a subject. According to A.K. Osnitsky, the subjectivity of a child can manifest itself in his authorial activity, which, due to various circumstances, can be more or less successful (for example, in cases of ADHD).

I.S. Yakimanskaya, being a supporter of student-centered learning, argues that the student initially, even before entering school, is the subject - the bearer of a unique subjective experience, and does not become the subject of learning in the process of learning activities. [26]. In the light of these statements, despite deviations in the development of psychophysiological functions, disorders in the development of cognitive, emotional and behavioral spheres that hinder the formation of subjectivity at primary school age, we believe that every child with ADHD, upon entering school, has his own unique experience gained in family or preschool institution, is an original, self-valuable personality, which means that already at this stage of its development it can be considered a subject. According to A.K. Osnitsky, the subjectivity of a child can manifest itself in his authorial activity, which, due to various circumstances, can be more or less successful (for example, in cases of ADHD). The degree of success of the author's activity in the learning environment can be adjusted and compensated by the attentive attitude of teachers to the individual characteristics of the child, as well as by the competent selection of teaching methods and techniques that correspond to the child's abilities [15].

The degree of success of the author's activity in the learning environment can be adjusted and compensated by the attentive attitude of teachers to the individual characteristics of the child, as well as by the competent selection of teaching methods and techniques that correspond to the child's abilities [15].

Thus, the analysis of the bibliographic data concerning subjective problems in psychological science allows us to come to the following conclusion. Despite the fact that with regard to the subjective approach, the most developed in domestic psychology, two opposite approaches have developed, acmeological and evolutionary. Supporters of the acmeological approach, who argue that the subject is the pinnacle of personal development, do not deny the gradual formation of subjectness in the course of activity, activity or life activity (A.V. Brushlinsky, V.V. Znakov, K.A. Abulkhanova-Slavskaya and others). In addition, A.V. Brushlinsky, who made the most significant contribution to the development of the subject approach, argues that a person becomes a subject starting from the age of 7-10 years, which corresponds (in the most common periodization in Russian psychology) to junior school age. We are closer to the second - the evolutionary approach, according to which the gradual development of a person as a subject is assumed, the subjectivity of which unfolds throughout his life. That is, a junior student with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a valuable, unique, original personality and manifests himself as a subject as a bearer of his own unique experience.

We are closer to the second - the evolutionary approach, according to which the gradual development of a person as a subject is assumed, the subjectivity of which unfolds throughout his life. That is, a junior student with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a valuable, unique, original personality and manifests himself as a subject as a bearer of his own unique experience.

1. Antsiferova L.I. Psychological content of the phenomenon of the subject and the boundaries of the subject-activity approach // The problem of the subject in psychological science / Ed. A.V. Brushlinsky, M.I. Volovikova, V.N. Druzhinin. - Moscow: Academic project, 2000. - S. 27-42.

2. Akhmetova Z.A. Socio-psychological factors of the prevalence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder among children // Bulletin of the Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University. - 2016. - V. 16, No. 12. - S. 149-154.

3. Brushlinskiy A.V. Psychology of the subject / Ed. ed. prof. V.V. Signs. - Moscow: Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences; St. Petersburg: Publishing House "Aleteiya", 2003. - 272 p.

Petersburg: Publishing House "Aleteiya", 2003. - 272 p.

4. Bryazgunov I.P., Kasatikova E.V. Restless child or all about hyperactive children. - Moscow: Publishing House of the Institute of Psychotherapy, 2001. - 96 p.

5. Developmental and pedagogical psychology: textbook. for students ped. in-tov / V.V. Davydov, T.V. Dragunova, L.B. Itelson and others / ed. A.V. Petrovsky. Ed. 2nd, rev. and additional - Moscow: Enlightenment, 1979. -287 p.

6. Voitenko T.P. The principle of the subjective approach in psychology and pedagogy: the problem of the anthropological context // Vestnik PSTGU. - Series IV: Pedagogy. Psychology. - 2017. - Issue. 44. - S. 67-83.

a§§zh§§zh§§§zhzh§zhzh§zh§zh§§§§® problems of modern psychology and pedagogy

7. DobsonD. Naughty child: pract. guide for parents. - Moscow: Penates: T-Oko, 1992. -

205 p.

8. Zavadenko, N.N., Suvorinova, N.Yu., Rumyantseva, M.V. Hyperactivity with attention deficit: risk factors, age dynamics, diagnostic features // Defectology. - 2003. - No. 6. - S. 13-20.

- 2003. - No. 6. - S. 13-20.

9. Zalomikhina I.Yu. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children // Speech Therapist Journal. -2007. - No. 3. - S. 33-39.

10. Znakov, V.V. From the psychology of the subject - to the psychology of human existence // Theory and methodology of psychology: Post-non-classical perspective / Ed. ed. A.L. Zhuravlev, A.V. Yurevich. - Moscow: Publishing house "Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences", 2007. - S. 330-351.

11. Kaigorodov, B.V., Nasyrova, O.A. Hyperactivity as a school and individual problem // World of Psychology. - 1996. - No. 1. - S. 100-106.

12. Koltsova, V.A. The procedure for the reconstruction of psychological knowledge in the context of the interaction of cultures / V.A. Koltsova // The idea of consistency in modern psychology / ed. V.A. Barabanshchikov. - Moscow: Publishing House of IP RAS, 2005. - S. 70-98.

13. Mash, E., Wolf, D. Child pathopsychology. Child mental disorders. - St. Petersburg: Prime-EVROZNAK, 2003. - 384 p.

- St. Petersburg: Prime-EVROZNAK, 2003. - 384 p.

14. Nikolskaya, A.V. The study of the category "subject" in Russian and foreign psychology // Person, subject, personality in modern psychology. Proceedings of the International Conference dedicated to the 80th anniversary of A.V. Brushlinsky. - Volume 1 / Res. ed. A.L. Zhuravlev, E.A. Sergienko. - Moscow: Publishing House "Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences", 2013. - S. 137-140.

15. Osnitsky, A.K. Subject and subjectivity // Man, subject, personality in modern psychology. Proceedings of the International Conference dedicated to the 80th anniversary of A.V. Brushlinsky. - Volume 1 / Res. ed. A.L. Zhuravlev, E.A. Sergienko. - Moscow: Publishing House "Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences", 2013. - S. 140-143.

16. Rubinstein, S.L. Being and consciousness. - St. Petersburg: Peter, 2017. - 288 p.

17. Rutman, E.M. Study of the development of attention in ontogeny // Vopr. psychol. - 1990. - No. 4. - With. 161167.

psychol. - 1990. - No. 4. - With. 161167.

18. Selivanova, O.G. Subjectivity of a schoolchild as a pedagogical phenomenon // Person, subject, personality in modern psychology. Proceedings of the International Conference dedicated to the 80th anniversary of A.V. Brushlinsky. - Volume 1 / Res. ed. A.L. Zhuravlev, E.A. Sergienko. - Moscow: Publishing House "Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences", 2013. - S. 325-326.

19. Sergienko, E.A. Development of A.V. Brushlinsky: correlation of categories of subject and personality // Man, subject, personality in modern psychology. Proceedings of the International Conference dedicated to the 80th anniversary of A.V. Brushlinsky. - Volume 1 / Res. ed. A.L. Zhuravlev, E.A. Sergienko. - Moscow: Publishing House "Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences", 2013. - S. 41-44.

20. Slobodchikov, V.I., Isaev, E.I. Psychology of human development: Development of subjective reality in ontogeny: Textbook. - Moscow: PSTGU Publishing House, 2013. - 400 p.

- Moscow: PSTGU Publishing House, 2013. - 400 p.

21. Stakhneva, L.A. Psychological conditions for the development of the subjectivity of the personality // Man, subject, personality in modern psychology. Proceedings of the International Conference dedicated to the 80th anniversary of A.V. Brushlinsky. Volume 1 / Responsible ed. A.L. Zhuravlev, E.A. Sergienko. - Moscow: Publishing House "Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences", 2013. S. 349-352.

22. Suvorova, O.V. The structure of subjectivity as the basis for a criterion-oriented assessment of its development in an older preschooler // Man, subject, personality in modern psychology. Proceedings of the International Conference dedicated to the 80th anniversary of A.V. Brushlinsky. - Volume 1 / Res. ed. A.L. Zhuravlev, E.A. Sergienko. - Moscow: Publishing House "Institute of Psychology of the Russian Academy of Sciences", 2013. - S. 352-354.

23. Wender, P., Shader, R. Psychiatry / Edited by R. Shader. Per. from English. - Moscow: Practice, 1998. - 485 p.

Shader. Per. from English. - Moscow: Practice, 1998. - 485 p.

24. Khotyleva, T.Yu. Technologies of psychological and pedagogical assistance to children with ADHD in Norway / T.Yu. Khotyleva, T.V. Akhutina // Electronic journal "Psychological Science and Education". - 2010. - No. 5. - URL: http://www.psyedu.ru/journal/2010/5/Hotyleva_Ahutina.phtml.

25. Shuvaeva, N.Yu. Formation of subjectivity of the younger schoolboy in the conditions of additional education: Dis.... kand. ... cand. ped. Sciences: 13.00.01. - Nizhny Novgorod, 2004. - 249 p.

26. Yakimanskaya, I.S. Student-centered learning in modern school. - Moscow : September 1996. - 96 p.

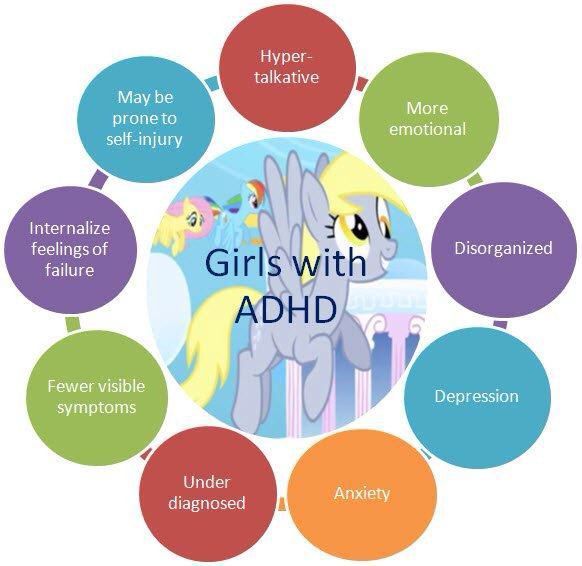

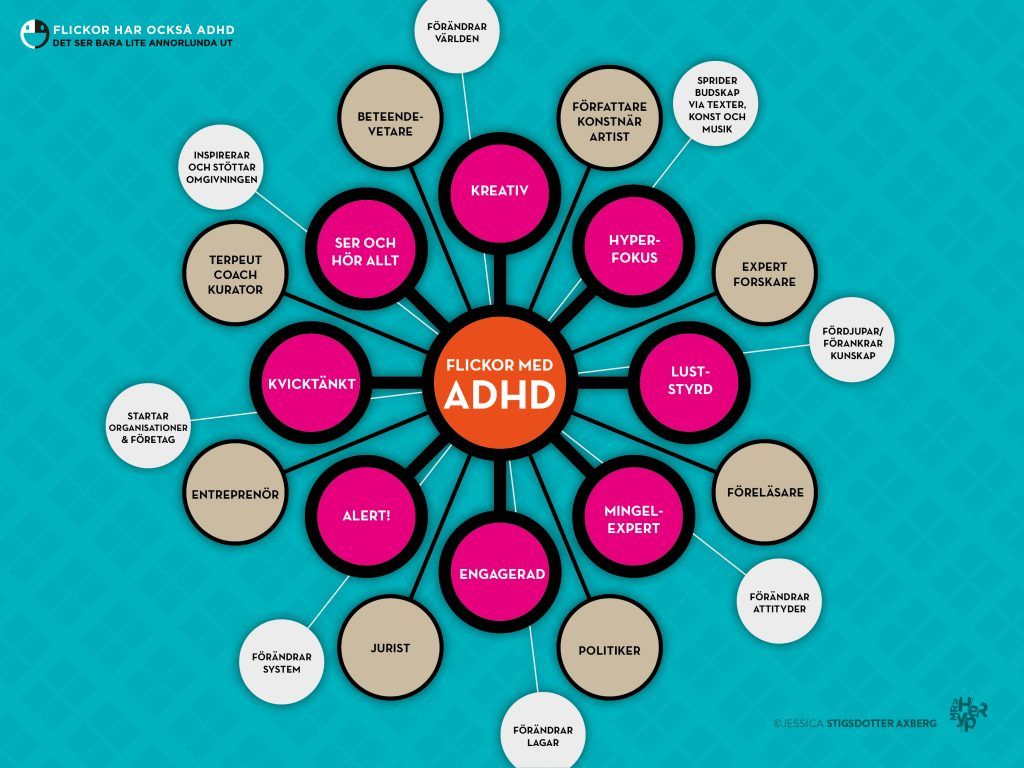

Are gender differences important in ADHD symptoms? (Spoiler: yes, very much).

Girls show fewer behavioral symptoms than boys, so many of them take years before being diagnosed. Read on to find out how ADHD manifests differently by gender.

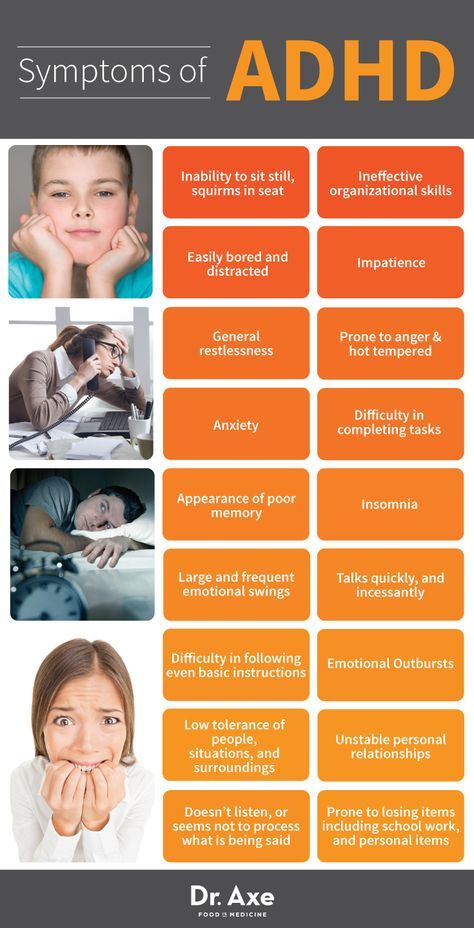

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is one of the most common neurodevelopmental disorders in childhood. It is caused by low levels of certain neurotransmitters, especially dopamine and norepinephrine. This imbalance leads to the classic symptoms of ADHD, such as excessive talkativeness, inability to sit still, trouble concentrating, and impulsivity.

It is caused by low levels of certain neurotransmitters, especially dopamine and norepinephrine. This imbalance leads to the classic symptoms of ADHD, such as excessive talkativeness, inability to sit still, trouble concentrating, and impulsivity.

Although most children show signs of ADHD before the age of seven, many remain undiagnosed until adulthood. Unfortunately, many of them tend to be girls. For example, studies show that boys are three times more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than girls.

This is not because ADHD is more common in boys, but because boys with ADHD tend to show outward symptoms such as impulsivity and aggression. Girls, on the other hand, struggle more with internal symptoms such as low self-esteem or trouble concentrating. It can be linked to many other problems, making it harder for parents and doctors to spot.

Why does gender affect ADHD symptoms?

The symptoms of ADHD are often gender-specific because the disorder is neurodevelopmental and, as everyone knows, girls develop differently than boys. In addition, ADHD is associated with neurochemicals that also play a critical role in how we express ourselves. But since our environment and upbringing also influence these traits, gender norms can also influence how ADHD differs between boys and girls. The most stereotypical example is that boys often express anger through physical aggression, while girls are prone to verbal aggression.

In addition, ADHD is associated with neurochemicals that also play a critical role in how we express ourselves. But since our environment and upbringing also influence these traits, gender norms can also influence how ADHD differs between boys and girls. The most stereotypical example is that boys often express anger through physical aggression, while girls are prone to verbal aggression.

To help those who are concerned that their child may have ADHD or that you may have an undiagnosed case, we asked our experts to talk about gender symptoms.

How to recognize ADHD in girls:

Girls with ADHD are usually not that hyperactive. Instead, they tend to have an attention deficit. For example, a girl is unlikely to disturb the class, but often misses assignments or daydreams too much.

Other symptoms include:

Closeness.

Intellectual difficulties.

Carelessness.

Verbal aggression (in relation to others or to oneself).

Problems with concentration.

Research shows that girls with untreated ADHD are at risk for low self-esteem, academic failure, depression, anxiety, addiction, and eating disorders. It is also estimated that almost 75% of girls with ADHD go unnoticed. Unfortunately, studies also show that young women with undiagnosed ADHD are three times more likely to attempt suicide or engage in self-harm.

However, these frightening statistics are greatly reduced when young women are diagnosed and receive adequate support, medication and psychotherapy.

How to recognize ADHD in boys:

Unlike girls, boys with ADHD are hyperactive. They will also show more classic signs such as:

Impulsivity (inappropriate behavior).

Lack of concentration and concentration problems.

Inability to sit still.

Physical aggression.

Frequent interruption of other people's conversations and activities.

However, regardless of your gender, untreated ADHD is a serious condition that is difficult to live with. It can make you feel frazzled and uncomfortable in your own skin when you're trying to commit to your hobbies, relationships, or life. This can lead to other mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression or substance abuse. However, ADHD is completely curable with adequate treatment and support.

It can make you feel frazzled and uncomfortable in your own skin when you're trying to commit to your hobbies, relationships, or life. This can lead to other mental illnesses such as anxiety and depression or substance abuse. However, ADHD is completely curable with adequate treatment and support.

If you think your daughter or son may have ADHD, see a specialist as soon as possible. Finally, try to remember that ADHD comes in many forms. If your child (or you) is showing some of the symptoms but not all, it's still worth seeing a specialist.

ADHD Treatment at Paracelsus Recovery

At Paracelsus Recovery, we offer in-depth and comprehensive ADHD treatment programs.

Our team of psychotherapists use a variety of methods, such as mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapy, to help you address all major issues, comorbid conditions, and develop strategies to manage your ADHD symptoms. You will also work closely with our in-house psychiatrist and psychotherapist, who is available 24/7 to provide you with emotional support.