Three domains of development

What Is Lifespan Development? – Psychology

Lifespan Development

OpenStaxCollege

[latexpage]

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

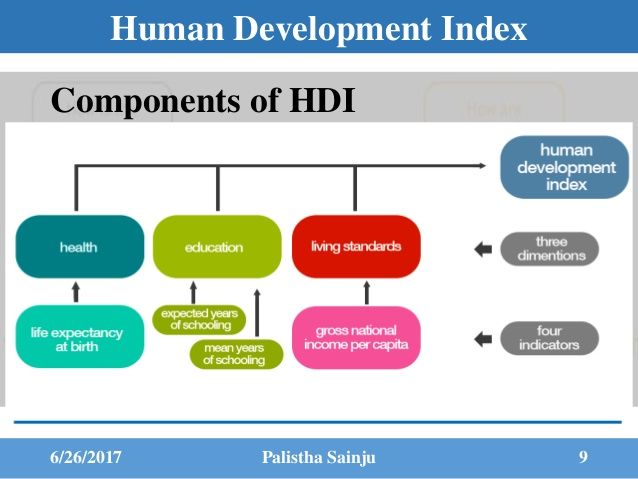

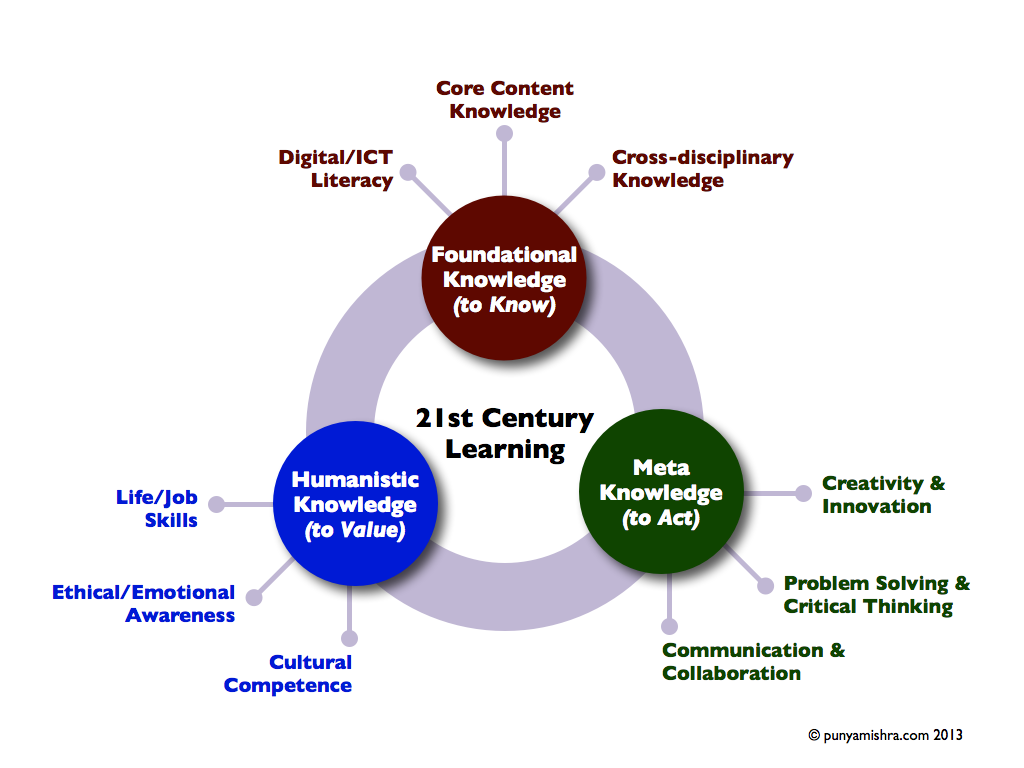

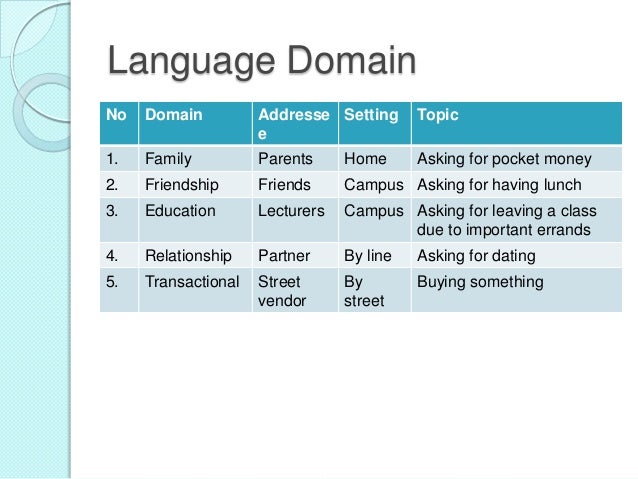

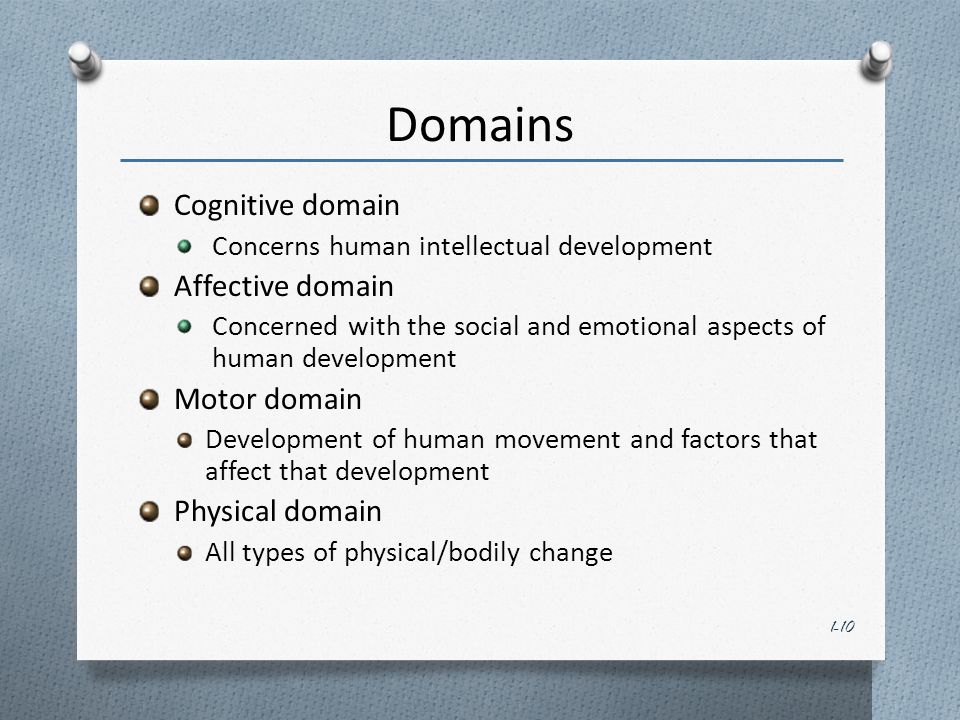

- Define and distinguish between the three domains of development: physical, cognitive and psychosocial

- Discuss the normative approach to development

- Understand the three major issues in development: continuity and discontinuity, one common course of development or many unique courses of development, and nature versus nurture

My heart leaps up when I behold

A rainbow in the sky:

So was it when my life began;

So is it now I am a man;

So be it when I shall grow old,

Or let me die!

The Child is father of the Man;

I could wish my days to be

Bound each to each by natural piety. (Wordsworth, 1802)

In this poem, William Wordsworth writes, “the child is father of the man. ” What does this seemingly incongruous statement mean, and what does it have to do with lifespan development? Wordsworth might be suggesting that the person he is as an adult depends largely on the experiences he had in childhood. Consider the following questions: To what extent is the adult you are today influenced by the child you once were? To what extent is a child fundamentally different from the adult he grows up to be?

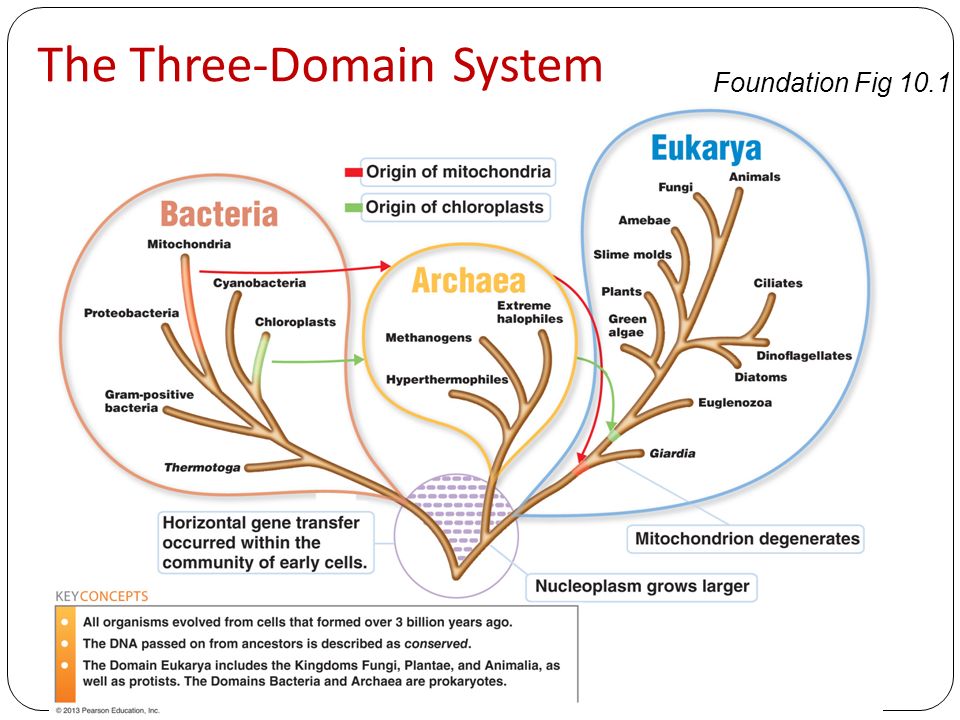

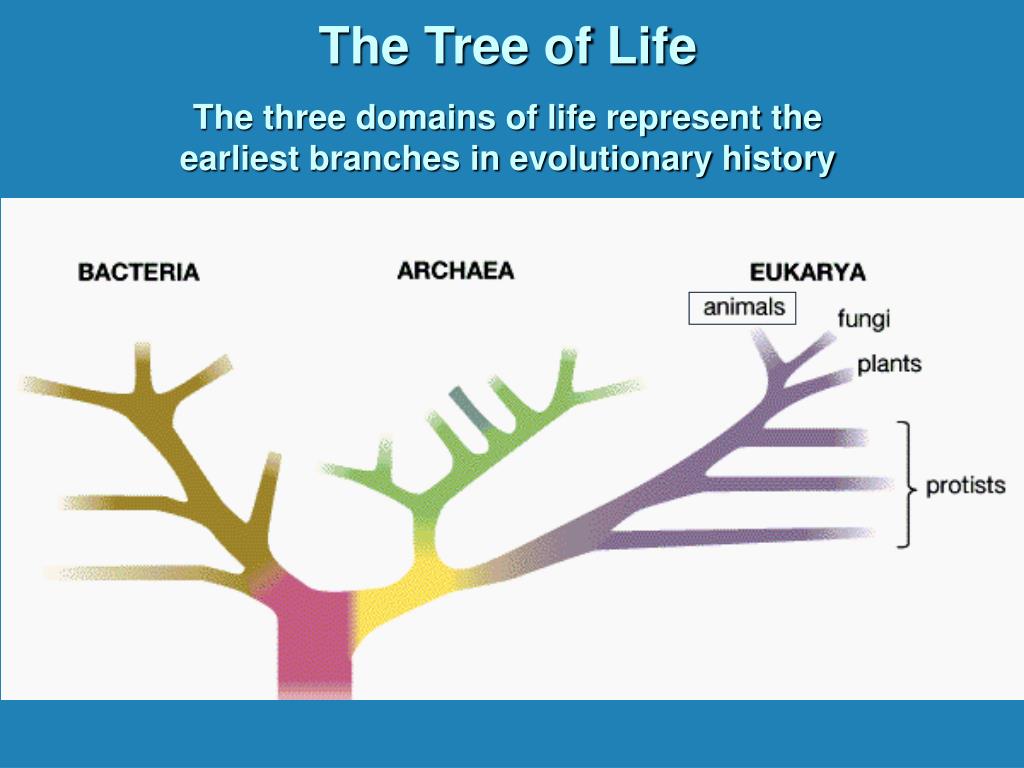

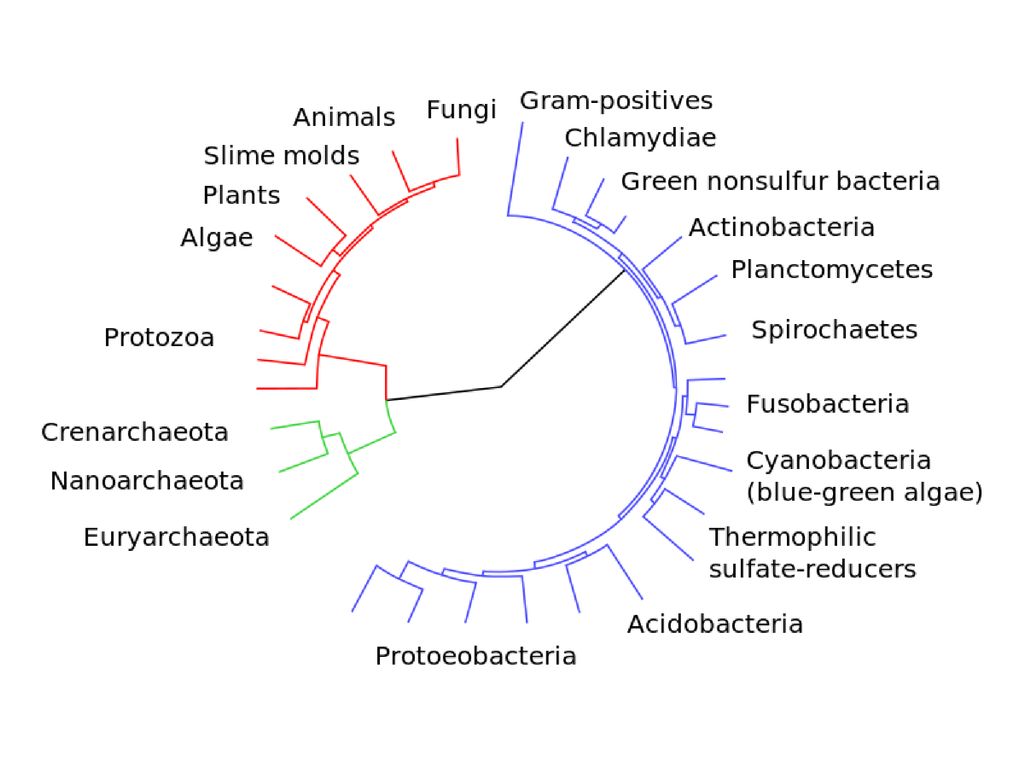

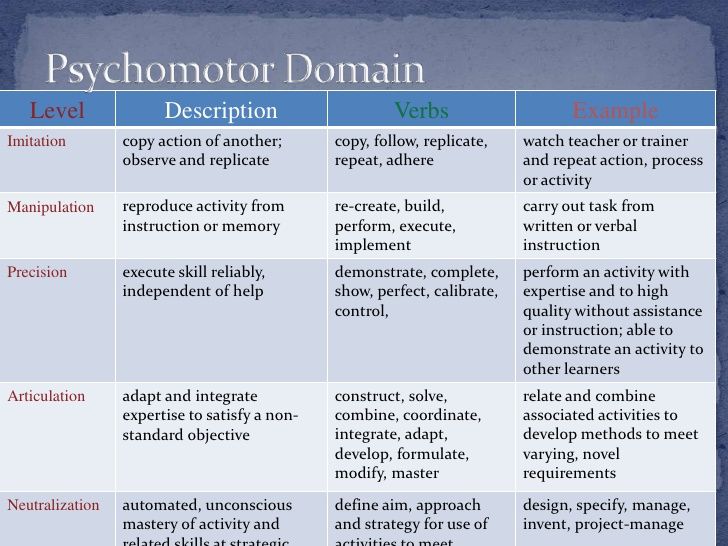

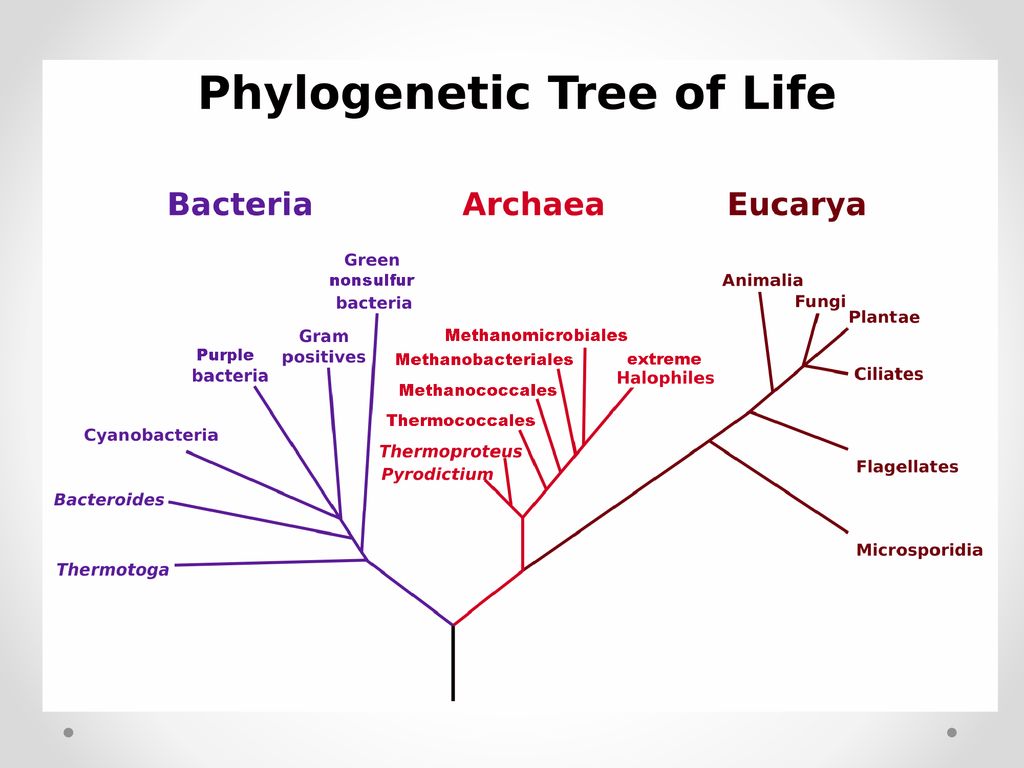

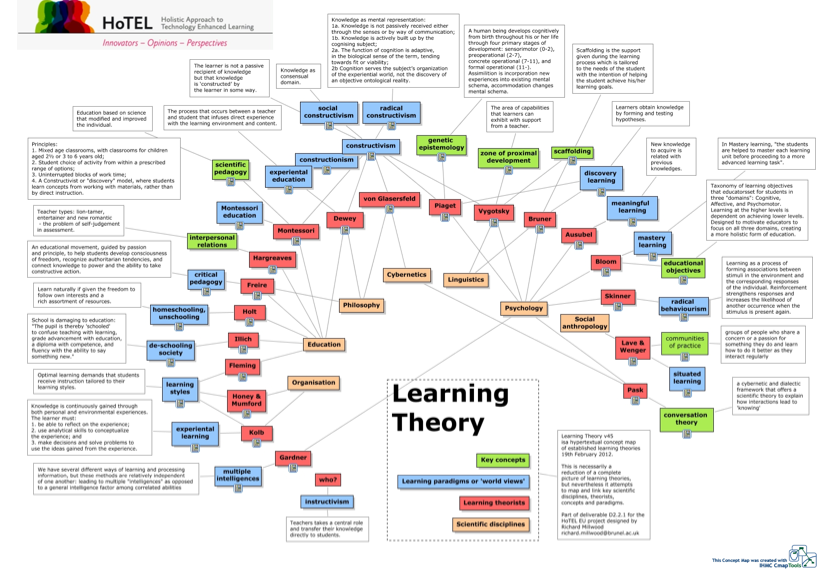

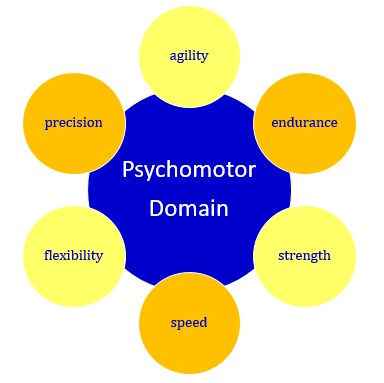

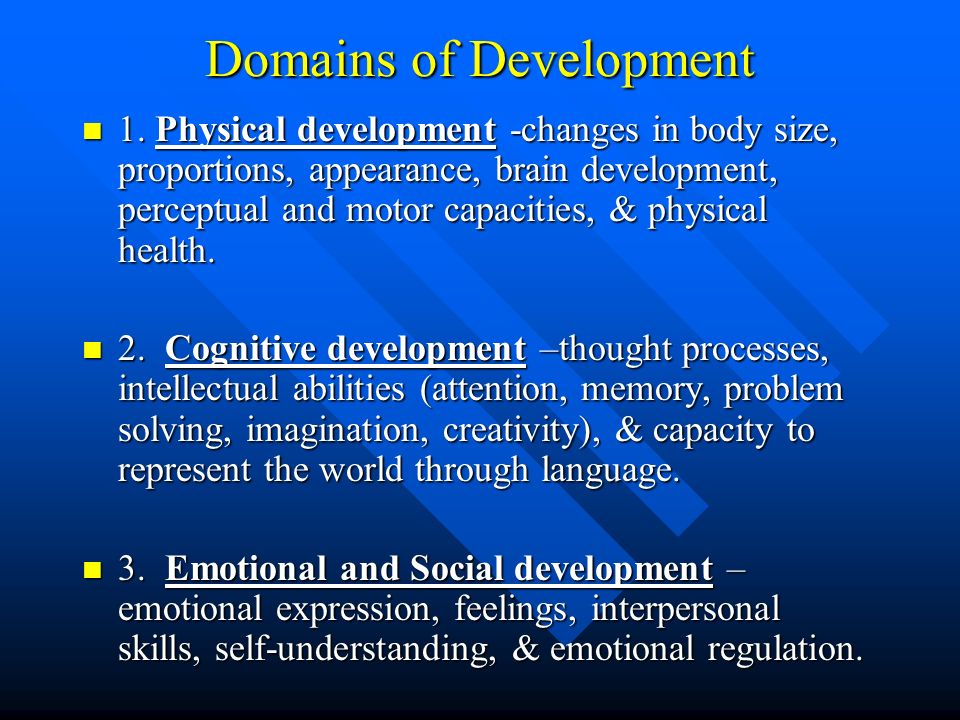

These are the types of questions developmental psychologists try to answer, by studying how humans change and grow from conception through childhood, adolescence, adulthood, and death. They view development as a lifelong process that can be studied scientifically across three developmental domains—physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development. Physical development involves growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness. Cognitive development involves learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, and social relationships. We refer to these domains throughout the chapter.

Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, and social relationships. We refer to these domains throughout the chapter.

Research Methods in Developmental Psychology

You’ve learned about a variety of research methods used by psychologists. Developmental psychologists use many of these approaches in order to better understand how individuals change mentally and physically over time. These methods include naturalistic observations, case studies, surveys, and experiments, among others.

Naturalistic observations involve observing behavior in its natural context. A developmental psychologist might observe how children behave on a playground, at a daycare center, or in the child’s own home. While this research approach provides a glimpse into how children behave in their natural settings, researchers have very little control over the types and/or frequencies of displayed behavior.

In a case study, developmental psychologists collect a great deal of information from one individual in order to better understand physical and psychological changes over the lifespan. This particular approach is an excellent way to better understand individuals, who are exceptional in some way, but it is especially prone to researcher bias in interpretation, and it is difficult to generalize conclusions to the larger population.

This particular approach is an excellent way to better understand individuals, who are exceptional in some way, but it is especially prone to researcher bias in interpretation, and it is difficult to generalize conclusions to the larger population.

In one classic example of this research method being applied to a study of lifespan development Sigmund Freud analyzed the development of a child known as “Little Hans” (Freud, 1909/1949). Freud’s findings helped inform his theories of psychosexual development in children, which you will learn about later in this chapter. Little Genie, the subject of a case study discussed in the chapter on thinking and intelligence, provides another example of how psychologists examine developmental milestones through detailed research on a single individual. In Genie’s case, her neglectful and abusive upbringing led to her being unable to speak until, at age 13, she was removed from that harmful environment. As she learned to use language, psychologists were able to compare how her language acquisition abilities differed when occurring in her late-stage development compared to the typical acquisition of those skills during the ages of infancy through early childhood (Fromkin, Krashen, Curtiss, Rigler, & Rigler, 1974; Curtiss, 1981).

The survey method asks individuals to self-report important information about their thoughts, experiences, and beliefs. This particular method can provide large amounts of information in relatively short amounts of time; however, validity of data collected in this way relies on honest self-reporting, and the data is relatively shallow when compared to the depth of information collected in a case study.

Experiments involve significant control over extraneous variables and manipulation of the independent variable. As such, experimental research allows developmental psychologists to make causal statements about certain variables that are important for the developmental process. Because experimental research must occur in a controlled environment, researchers must be cautious about whether behaviors observed in the laboratory translate to an individual’s natural environment.

Later in this chapter, you will learn about several experiments in which toddlers and young children observe scenes or actions so that researchers can determine at what age specific cognitive abilities develop. For example, children may observe a quantity of liquid poured from a short, fat glass into a tall, skinny glass. As the experimenters question the children about what occurred, the subjects’ answers help psychologists understand at what age a child begins to comprehend that the volume of liquid remained the same although the shapes of the containers differs.

For example, children may observe a quantity of liquid poured from a short, fat glass into a tall, skinny glass. As the experimenters question the children about what occurred, the subjects’ answers help psychologists understand at what age a child begins to comprehend that the volume of liquid remained the same although the shapes of the containers differs.

Across these three domains—physical, cognitive, and psychosocial—the normative approach to development is also discussed. This approach asks, “What is normal development?” In the early decades of the 20th century, normative psychologists studied large numbers of children at various ages to determine norms (i.e., average ages) of when most children reach specific developmental milestones in each of the three domains (Gesell, 1933, 1939, 1940; Gesell & Ilg, 1946; Hall, 1904). Although children develop at slightly different rates, we can use these age-related averages as general guidelines to compare children with same-age peers to determine the approximate ages they should reach specific normative events called developmental milestones (e. g., crawling, walking, writing, dressing, naming colors, speaking in sentences, and starting puberty).

g., crawling, walking, writing, dressing, naming colors, speaking in sentences, and starting puberty).

Not all normative events are universal, meaning they are not experienced by all individuals across all cultures. Biological milestones, such as puberty, tend to be universal, but social milestones, such as the age when children begin formal schooling, are not necessarily universal; instead, they affect most individuals in a particular culture (Gesell & Ilg, 1946). For example, in developed countries children begin school around 5 or 6 years old, but in developing countries, like Nigeria, children often enter school at an advanced age, if at all (Huebler, 2005; United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization [UNESCO], 2013).

To better understand the normative approach, imagine two new mothers, Louisa and Kimberly, who are close friends and have children around the same age. Louisa’s daughter is 14 months old, and Kimberly’s son is 12 months old. According to the normative approach, the average age a child starts to walk is 12 months. However, at 14 months Louisa’s daughter still isn’t walking. She tells Kimberly she is worried that something might be wrong with her baby. Kimberly is surprised because her son started walking when he was only 10 months old. Should Louisa be worried? Should she be concerned if her daughter is not walking by 15 months or 18 months?

However, at 14 months Louisa’s daughter still isn’t walking. She tells Kimberly she is worried that something might be wrong with her baby. Kimberly is surprised because her son started walking when he was only 10 months old. Should Louisa be worried? Should she be concerned if her daughter is not walking by 15 months or 18 months?

There are many different theoretical approaches regarding human development. As we evaluate them in this chapter, recall that developmental psychology focuses on how people change, and keep in mind that all the approaches that we present in this chapter address questions of change: Is the change smooth or uneven (continuous versus discontinuous)? Is this pattern of change the same for everyone, or are there many different patterns of change (one course of development versus many courses)? How do genetics and environment interact to influence development (nature versus nurture)?

Is Development Continuous or Discontinuous?

Continuous development views development as a cumulative process, gradually improving on existing skills ([link]). With this type of development, there is gradual change. Consider, for example, a child’s physical growth: adding inches to her height year by year. In contrast, theorists who view development as discontinuous believe that development takes place in unique stages: It occurs at specific times or ages. With this type of development, the change is more sudden, such as an infant’s ability to conceive object permanence.

With this type of development, there is gradual change. Consider, for example, a child’s physical growth: adding inches to her height year by year. In contrast, theorists who view development as discontinuous believe that development takes place in unique stages: It occurs at specific times or ages. With this type of development, the change is more sudden, such as an infant’s ability to conceive object permanence.

The concept of continuous development can be visualized as a smooth slope of progression, whereas discontinuous development sees growth in more discrete stages.

Is There One Course of Development or Many?

Is development essentially the same, or universal, for all children (i.e., there is one course of development) or does development follow a different course for each child, depending on the child’s specific genetics and environment (i.e., there are many courses of development)? Do people across the world share more similarities or more differences in their development? How much do culture and genetics influence a child’s behavior?

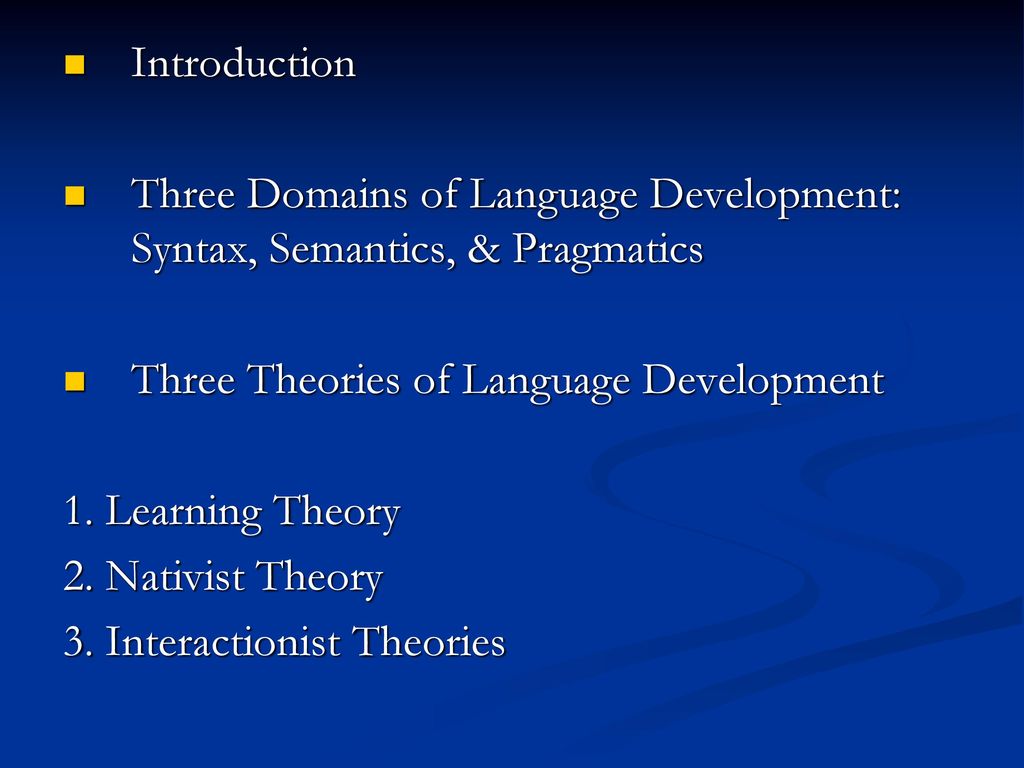

Stage theories hold that the sequence of development is universal. For example, in cross-cultural studies of language development, children from around the world reach language milestones in a similar sequence (Gleitman & Newport, 1995). Infants in all cultures coo before they babble. They begin babbling at about the same age and utter their first word around 12 months old. Yet we live in diverse contexts that have a unique effect on each of us. For example, researchers once believed that motor development follows one course for all children regardless of culture. However, child care practices vary by culture, and different practices have been found to accelerate or inhibit achievement of developmental milestones such as sitting, crawling, and walking (Karasik, Adolph, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 2010).

For example, in cross-cultural studies of language development, children from around the world reach language milestones in a similar sequence (Gleitman & Newport, 1995). Infants in all cultures coo before they babble. They begin babbling at about the same age and utter their first word around 12 months old. Yet we live in diverse contexts that have a unique effect on each of us. For example, researchers once believed that motor development follows one course for all children regardless of culture. However, child care practices vary by culture, and different practices have been found to accelerate or inhibit achievement of developmental milestones such as sitting, crawling, and walking (Karasik, Adolph, Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 2010).

For instance, let’s look at the Aché society in Paraguay. They spend a significant amount of time foraging in forests. While foraging, Aché mothers carry their young children, rarely putting them down in order to protect them from getting hurt in the forest. Consequently, their children walk much later: They walk around 23–25 months old, in comparison to infants in Western cultures who begin to walk around 12 months old. However, as Aché children become older, they are allowed more freedom to move about, and by about age 9, their motor skills surpass those of U.S. children of the same age: Aché children are able to climb trees up to 25 feet tall and use machetes to chop their way through the forest (Kaplan & Dove, 1987). As you can see, our development is influenced by multiple contexts, so the timing of basic motor functions may vary across cultures. However, the functions themselves are present in all societies ([link]).

Consequently, their children walk much later: They walk around 23–25 months old, in comparison to infants in Western cultures who begin to walk around 12 months old. However, as Aché children become older, they are allowed more freedom to move about, and by about age 9, their motor skills surpass those of U.S. children of the same age: Aché children are able to climb trees up to 25 feet tall and use machetes to chop their way through the forest (Kaplan & Dove, 1987). As you can see, our development is influenced by multiple contexts, so the timing of basic motor functions may vary across cultures. However, the functions themselves are present in all societies ([link]).

All children across the world love to play. Whether in (a) Florida or (b) South Africa, children enjoy exploring sand, sunshine, and the sea. (credit a: modification of work by “Visit St. Pete/Clearwater”/Flickr; credit b: modification of work by “stringer_bel”/Flickr)

How Do Nature and Nurture Influence Development?

Are we who we are because of nature (biology and genetics), or are we who we are because of nurture (our environment and culture)? This longstanding question is known in psychology as the nature versus nurture debate. It seeks to understand how our personalities and traits are the product of our genetic makeup and biological factors, and how they are shaped by our environment, including our parents, peers, and culture. For instance, why do biological children sometimes act like their parents—is it because of genetics or because of early childhood environment and what the child has learned from the parents? What about children who are adopted—are they more like their biological families or more like their adoptive families? And how can siblings from the same family be so different?

It seeks to understand how our personalities and traits are the product of our genetic makeup and biological factors, and how they are shaped by our environment, including our parents, peers, and culture. For instance, why do biological children sometimes act like their parents—is it because of genetics or because of early childhood environment and what the child has learned from the parents? What about children who are adopted—are they more like their biological families or more like their adoptive families? And how can siblings from the same family be so different?

We are all born with specific genetic traits inherited from our parents, such as eye color, height, and certain personality traits. Beyond our basic genotype, however, there is a deep interaction between our genes and our environment: Our unique experiences in our environment influence whether and how particular traits are expressed, and at the same time, our genes influence how we interact with our environment (Diamond, 2009; Lobo, 2008). This chapter will show that there is a reciprocal interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

This chapter will show that there is a reciprocal interaction between nature and nurture as they both shape who we become, but the debate continues as to the relative contributions of each.

The Achievement Gap: How Does Socioeconomic Status Affect Development?

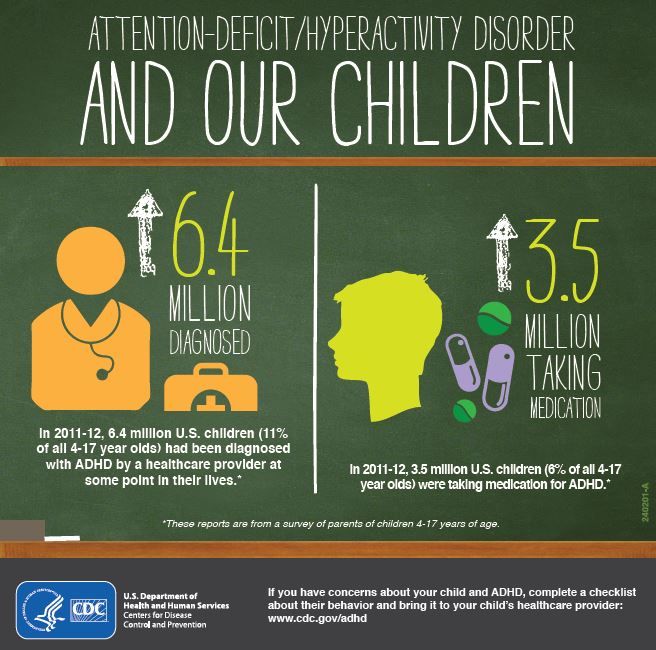

The achievement gap refers to the persistent difference in grades, test scores, and graduation rates that exist among students of different ethnicities, races, and—in certain subjects—sexes (Winerman, 2011). Research suggests that these achievement gaps are strongly influenced by differences in socioeconomic factors that exist among the families of these children. While the researchers acknowledge that programs aimed at reducing such socioeconomic discrepancies would likely aid in equalizing the aptitude and performance of children from different backgrounds, they recognize that such large-scale interventions would be difficult to achieve. Therefore, it is recommended that programs aimed at fostering aptitude and achievement among disadvantaged children may be the best option for dealing with issues related to academic achievement gaps (Duncan & Magnuson, 2005).

Low-income children perform significantly more poorly than their middle- and high-income peers on a number of educational variables: They have significantly lower standardized test scores, graduation rates, and college entrance rates, and they have much higher school dropout rates. There have been attempts to correct the achievement gap through state and federal legislation, but what if the problems start before the children even enter school?

Psychologists Betty Hart and Todd Risley (2006) spent their careers looking at early language ability and progression of children in various income levels. In one longitudinal study, they found that although all the parents in the study engaged and interacted with their children, middle- and high-income parents interacted with their children differently than low-income parents. After analyzing 1,300 hours of parent-child interactions, the researchers found that middle- and high-income parents talk to their children significantly more, starting when the children are infants. By 3 years old, high-income children knew almost double the number of words known by their low-income counterparts, and they had heard an estimated total of 30 million more words than the low-income counterparts (Hart & Risley, 2003). And the gaps only become more pronounced. Before entering kindergarten, high-income children score 60% higher on achievement tests than their low-income peers (Lee & Burkam, 2002).

By 3 years old, high-income children knew almost double the number of words known by their low-income counterparts, and they had heard an estimated total of 30 million more words than the low-income counterparts (Hart & Risley, 2003). And the gaps only become more pronounced. Before entering kindergarten, high-income children score 60% higher on achievement tests than their low-income peers (Lee & Burkam, 2002).

There are solutions to this problem. At the University of Chicago, experts are working with low-income families, visiting them at their homes, and encouraging them to speak more to their children on a daily and hourly basis. Other experts are designing preschools in which students from diverse economic backgrounds are placed in the same classroom. In this research, low-income children made significant gains in their language development, likely as a result of attending the specialized preschool (Schechter & Byeb, 2007). What other methods or interventions could be used to decrease the achievement gap? What types of activities could be implemented to help the children of your community or a neighboring community?

Lifespan development explores how we change and grow from conception to death. This field of psychology is studied by developmental psychologists. They view development as a lifelong process that can be studied scientifically across three developmental domains: physical, cognitive development, and psychosocial. There are several theories of development that focus on the following issues: whether development is continuous or discontinuous, whether development follows one course or many, and the relative influence of nature versus nurture on development.

This field of psychology is studied by developmental psychologists. They view development as a lifelong process that can be studied scientifically across three developmental domains: physical, cognitive development, and psychosocial. There are several theories of development that focus on the following issues: whether development is continuous or discontinuous, whether development follows one course or many, and the relative influence of nature versus nurture on development.

The view that development is a cumulative process, gradually adding to the same type of skills is known as ________.

- nature

- nurture

- continuous development

- discontinuous development

C

Developmental psychologists study human growth and development across three domains. Which of the following is not one of these domains?

- cognitive

- psychological

- physical

- psychosocial

B

How is lifespan development defined?

- The study of how we grow and change from conception to death.

- The study of how we grow and change in infancy and childhood.

- The study of physical, cognitive, and psychosocial growth in children.

- The study of emotions, personality, and social relationships.

A

Describe the nature versus nurture controversy, and give an example of a trait and how it might be influenced by each?

The nature versus nurture controversy seeks to understand whether our personalities and traits are the product of our genetic makeup and biological factors, or whether they are shaped by our environment, which includes such things as our parents, peers, and culture. Today, psychologists agree that both nature and nurture interact to shape who we become, but the debate over the relative contributions of each continues. An example would be a child learning to walk: Nature influences when the physical ability occurs, but culture can influence when a child masters this skill, as in Aché culture.

Compare and contrast continuous and discontinuous development.

Continuous development sees our development as a cumulative process: Changes are gradual. On the other hand, discontinuous development sees our development as taking place in specific steps or stages: Changes are sudden.

Why should developmental milestones only be used as a general guideline for normal child development?

Children develop at different rates. For example, some children may walk and talk as early as 8 months old, while others may not do so until well after their first birthday. Each child’s unique contexts will influence when he reaches these milestones.

How are you different today from the person you were at 6 years old? What about at 16 years old? How are you the same as the person you were at those ages?

Your 3-year-old daughter is not yet potty trained. Based on what you know about the normative approach, should you be concerned? Why or why not?

Glossary

- cognitive development

- domain of lifespan development that examines learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity

- continuous development

- view that development is a cumulative process: gradually improving on existing skills

- developmental milestone

- approximate ages at which children reach specific normative events

- discontinuous development

- view that development takes place in unique stages, which happen at specific times or ages

- nature

- genes and biology

- normative approach

- study of development using norms, or average ages, when most children reach specific developmental milestones

- nurture

- environment and culture

- physical development

- domain of lifespan development that examines growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness

- psychosocial development

- domain of lifespan development that examines emotions, personality, and social relationships

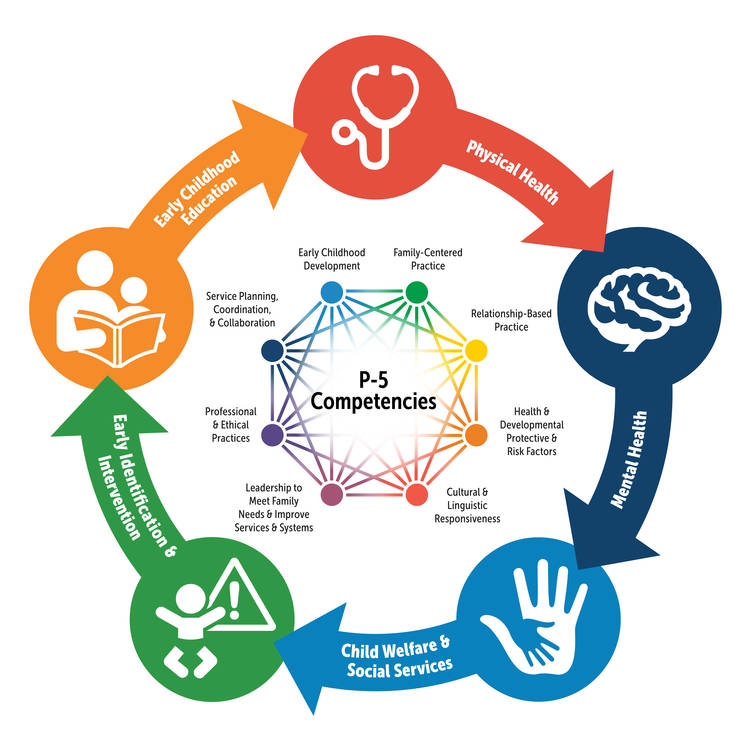

Human Development | Adolescent Psychology

Development refers to the physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development of humans throughout the lifespan. What types of development are involved in each of these three domains, or areas, of life? Physical development involves growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness. Cognitive development involves learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, and social relationships.

What types of development are involved in each of these three domains, or areas, of life? Physical development involves growth and changes in the body and brain, the senses, motor skills, and health and wellness. Cognitive development involves learning, attention, memory, language, thinking, reasoning, and creativity. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, and social relationships.

Figure 1.2.1. Physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development are interrelated.

Physical Domain

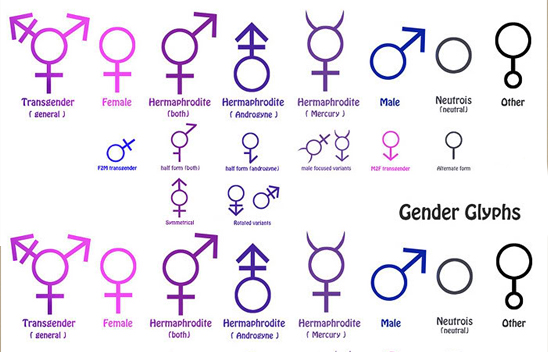

Many of us are familiar with the height and weight charts that pediatricians consult to estimate if babies, children, and teens are growing within normative ranges of physical development. We may also be aware of changes in children’s fine and gross motor skills, as well as their increasing coordination, particularly in terms of playing sports. But we may not realize that physical development also involves brain development, which not only enables childhood motor coordination but also greater coordination between emotions and planning in adulthood, as our brains are not done developing in infancy or childhood. Physical development also includes puberty, sexual health, fertility, menopause, changes in our senses, and healthy habits with nutrition and exercise.

Physical development also includes puberty, sexual health, fertility, menopause, changes in our senses, and healthy habits with nutrition and exercise.

Cognitive Domain

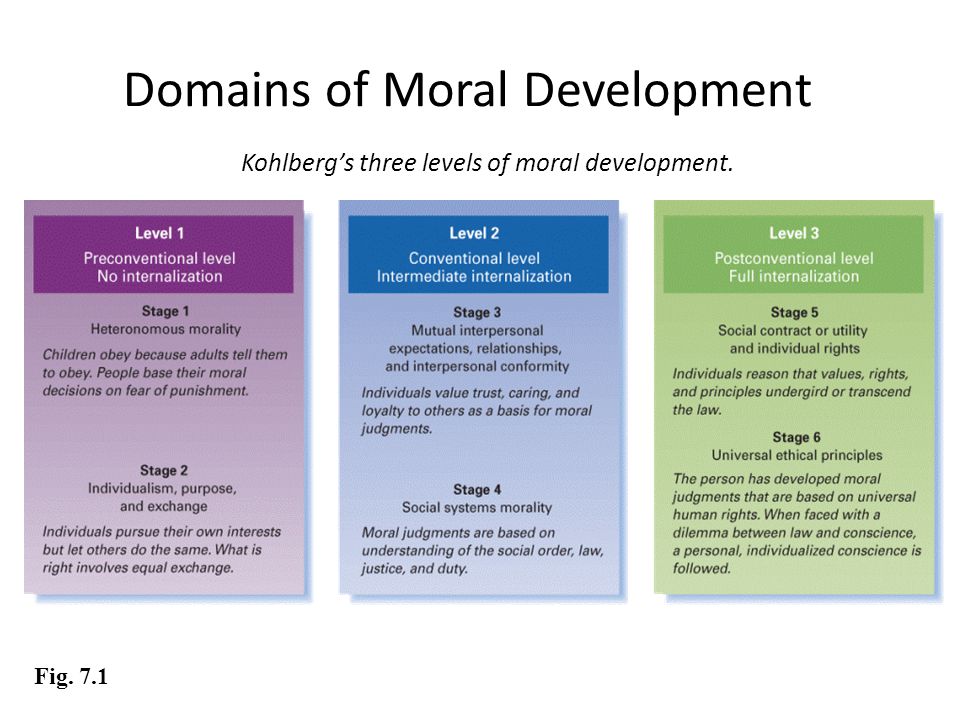

If we watch and listen to infants and toddlers, we can’t help but wonder how they learn so much so fast, particularly when it comes to language development. Then as we compare young children to those in middle childhood, there appear to be considerable differences in their ability to think logically about the concrete world around them. Cognitive development includes mental processes, thinking, learning, and understanding, and it doesn’t stop in childhood. Adolescents develop the ability to think logically about the abstract world (and may like to debate matters with adults as they exercise their new cognitive skills!). Moral reasoning develops further, as does practical intelligence—wisdom may develop with experience over time. Memory abilities and different forms of intelligence tend to change with age. Brain development and the brain’s ability to adapt and compensate for losses is significant to cognitive functions across the lifespan, too.

Brain development and the brain’s ability to adapt and compensate for losses is significant to cognitive functions across the lifespan, too.

Psychosocial Domain

Development in the psychosocial (or socioemotional) domain involves what’s going on both psychologically and socially. Early on, the focus is on infants and caregivers, as temperament and attachment are significant. As the social world expands and the child grows psychologically, different types of play and interactions with other children and teachers become essential. Psychosocial development involves emotions, personality, self-esteem, and relationships. Peers become more important for adolescents, who are exploring new roles and forming their own identities. Dating, romance, cohabitation, marriage, having children, and finding work or a career are all parts of the transition into adulthood. Psychosocial development continues across adulthood with similar (and some different) developmental issues of family, friends, parenting, romance, divorce, remarriage, blended families, caregiving for elders, becoming grandparents and great grandparents, retirement, new careers, coping with losses, and death and dying.

As you may have already noticed, physical, cognitive, and psychosocial development are often interrelated, Puberty exemplifies this interaction well. Puberty is a biological change that releases hormones that spurs the maturation of sex organs and physical growth. However, puberty also triggers changes within the brain that affect cognition, emotions, and social relationships. Puberty often comes with mood swings, but also, improved ability to self-regulate. Puberty is also when relationships change with parents and peers. While puberty may be a topic within the physical domain, there is clearly an interaction with the other areas.

Video 1.2.1. Domains in Development describes the three domains and how those domains interact.

Who Studies Development and Why?

Many academic disciplines contribute to the study of development and developmental psychology is related to other applied fields. The study of development informs several applied fields in psychology, including educational psychology, psychopathology, and forensic developmental psychology. It also complements several other specific areas of psychology, including social psychology, cognitive psychology, and comparative psychology. This multidisciplinary course is made up of contributions from researchers in the areas of biology, health care, anthropology, nutrition, and sociology, among others.

The study of development informs several applied fields in psychology, including educational psychology, psychopathology, and forensic developmental psychology. It also complements several other specific areas of psychology, including social psychology, cognitive psychology, and comparative psychology. This multidisciplinary course is made up of contributions from researchers in the areas of biology, health care, anthropology, nutrition, and sociology, among others.

The main goals of those involved in studying development are to describe, predict, and explain changes. Throughout this course, we will describe observations during development, predict courses and milestones for change, and then examine how theories provide explanations for why these changes occur.

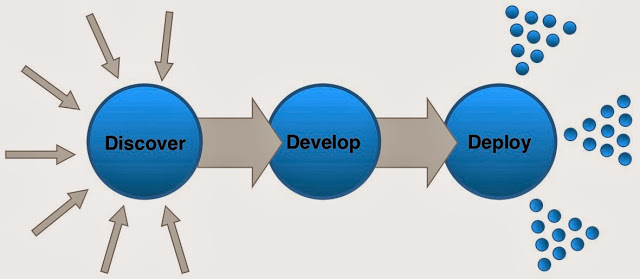

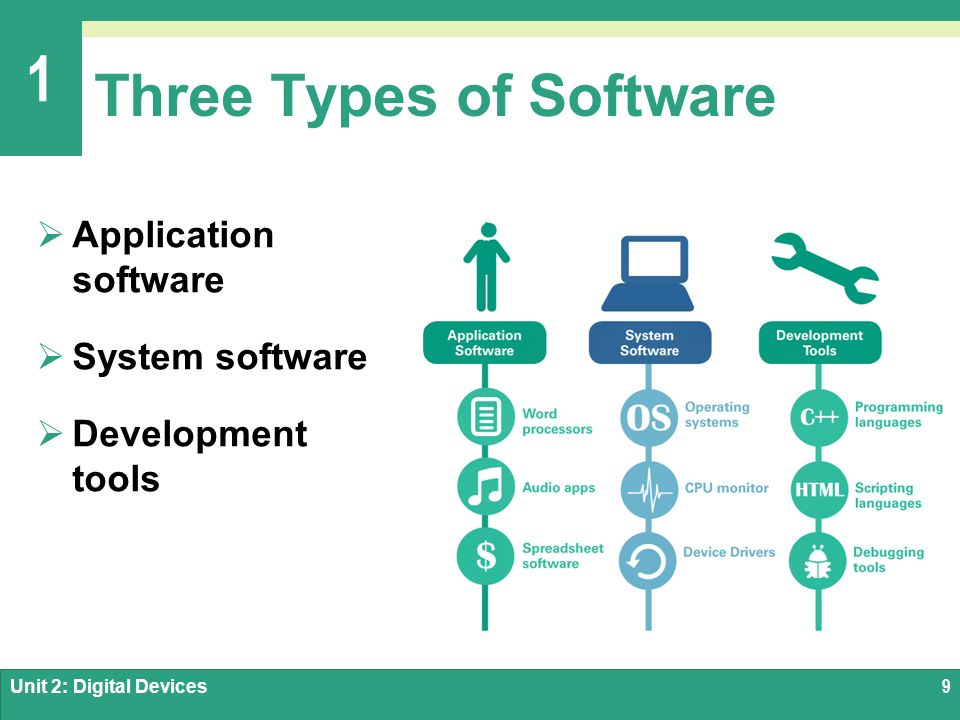

Three directions of technological development in industrial production in 2021

Stories

DIG(IT)AL

Stories

Daria Sidorova

Editor of the History Department.

Darya Sidorova

The industrial industry has taken on the heavy consequences of the economic downturn. Recovery may take a long time. The latest technologies will help speed up this process and ensure the resilience of the industry to future crises. Rafi Billurcu, head of operations at Infosys Consulting, named three areas of technology development that will allow the industry to recover faster in 2021.

In the Dig(IT)al project, we talk about technologies that will help you make money. Move to the digital side of business.

Daria Sidorova

A PwC study found that 80% of manufacturing CFOs expect the pandemic to impact their business revenue. This opinion is shared by about 48% of representatives of inter-industry companies.

The industry has suffered greatly for two reasons.

- Most of the work cannot be done remotely.

- The slowdown in the economy reduced the demand for industrial products around the world.

In order to sustain business during times of uncertainty and ensure its resilience against future crises, businesses need to invest in new technologies.

Here are three trends in industrial technology in 2021.

Remote control of equipment

Manufacturing companies will use more and more technologies that will allow them to control objects remotely. This will reduce the number of staff in the workplace.

“The application of automation and other technologies of the fourth industrial revolution, such as augmented and virtual reality, and analytics, will ensure the efficiency of production with minimal impact. This will affect both the gross income and the net profit of organizations,” says Billurcu.

Remote control becomes the new norm. With these technologies, equipment such as forklifts can be controlled remotely. Specialists can work collaboratively with field operators via AR headsets without the need for personal presence.

With these technologies, equipment such as forklifts can be controlled remotely. Specialists can work collaboratively with field operators via AR headsets without the need for personal presence.

“Remote work and automation will increase access to global talent for manufacturing organizations,” says Billurcu.

“This is becoming increasingly important in the post-pandemic digital skills age,” he adds.

Development of 5G networks

The fourth industrial revolution was slowed down by the pandemic. The economic downturn has prevented some industry players from investing in new technologies. However, in 2021 this development will accelerate and the industry will try to return to pre-crisis levels.

“5G networks will be a critical element of the next generation of businesses. They will provide the reliable, low-latency connectivity needed for the fourth industrial revolution,” says Billurcu.

The speed and reliability of 5G networks will enable manufacturers to move closer to creating an intelligent enterprise and realizing the full potential of digital technologies.

Widespread adoption of artificial intelligence

“2020 has taught the manufacturing industry an important lesson, and the coronavirus crisis has shown that risk cannot be avoided,” says Billurcu.

Artificial intelligence is expected to become more widespread in manufacturing and supply chains next year. It will allow you to better predict risks and quickly address them.

“AI-powered tools can provide automated solutions in just a second. For example, manage the logistics network, change the transportation route and choose the delivery method,” says Billurcu.

Technologies such as 3D printing and blockchain will also proliferate as organizations seek to prepare for similar unforeseen developments in the future.

Source.

Cover photo: Andrey Armyagov / Shutterstock

- Artificial intelligence

- augmented reality

- Business

- Industry

- The world after the epidemic

- robots

- Digital transformation

- Virtual reality

- Coronavirus

Found a typo? Select the text and press Ctrl + Enter

Related materials

- one Overview of the MedTech sphere: what technologies are best to invest in now

- 2 How Speech Technology Helps Businesses Reduce Costs and Improve Customer Experience

- 3 The Russian Funds investment group has increased investments in the food industry

- four Investment in meat substitutes increased by 40% - study

CAPABILITIES

November 11, 2022

AI Journey Contest

November 13, 2022

FranchCamp Aspiring Entrepreneur Competition

November 13, 2022

Sovcombank Team Challenge 2022

All possibilities

News

Only 12.

6% are going on New Year's trip - poll

6% are going on New Year's trip - poll News

Oleg Tinkov decided to renounce Russian citizenship

News

FAS will check marketplaces and retailers after complaints about inflated prices for military equipment

Speakers

9 promising business ideas after the departure of foreign companies

Speakers

Memory training: tips and exercises to help keep the brain in good shape

Directions for the development of scientific research | Saint-Petersburg Mining University

Drilling and exploration technologies, ice cores and subglacial lakes includes:

- development of technology and technical means for melt drilling in ice;

- development of technology and technical means for drilling wells in ice by mechanical means;

- development of a formulation of non-freezing drilling fluid to prevent the narrowing of the wellbore under the influence of rock pressure and the natural ice temperature that increases with depth, significantly changing its viscoplastic properties.

- development of special methods and equipment for a complex of geophysical well surveys in extreme conditions of polar glaciers.

- development of technology for environmentally clean opening and exploration of subglacial reservoirs

technologies for fixing and isolating individual intervals of oil and gas wells using high-temperature heat generators Technology and technique of directional drilling includes: Normalization of the temperature regime of the circulation medium in the well and operation of the diamond tool includes: Development of drilling fluid formulations for opening productive horizons of wells and ensuring well wall stability at the same time includes: ; Investigation of technological modes and control systems of a dynamically balanced drill assembly on a load-carrying cable with an autoresonant electric drive of reciprocating-rotary motion includes: Technical means and technology for drilling oil and gas wells includes: and optimization:

- rotary controlled systems and their modifications;

- improvement of screw downhole motors by balancing oscillations of planetary gear systems, regulation of contact stresses of helical surfaces of cycloidal gearing;

- profile or section of the trajectory, taking into account the multi-criteria analysis of the technical and technological parameters of well drilling and operation;

- drilling parameters for complex trajectories of well profiles, taking into account fluctuations in the bottom of the string assembly system, stress-strain state and stability of the drilling tool in well conditions;

- hydrodynamics during the development and drilling of wells with varying PVT, including models of the formation and flow of multiphase gas-containing emulsions under conditions of variable pressure and temperature, which provides enhanced oil recovery of wells in fields with hard-to-recover reserves.