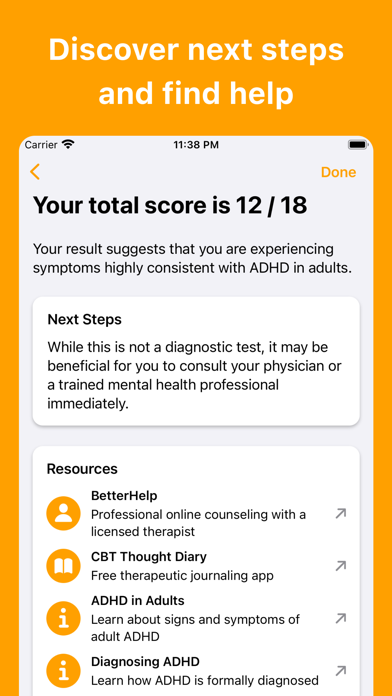

There is a simple diagnostic test available to diagnose adhd

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) - Diagnosis

If you think you or your child may have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), speak to a GP.

If you're worried about your child, it may help to speak to their teachers, before seeing a GP, to find out if they have any concerns about your child's behaviour.

The GP cannot formally diagnose ADHD, but they can discuss your concerns with you and refer you for a specialist assessment, if necessary.

When you see a GP, they may ask you:

- about your symptoms or those of your child

- when these symptoms started

- where the symptoms occur – for example, at home, in school, college or university, or at work

- whether the symptoms affect your or your child's day-to-day life – for example, if they make socialising difficult

- if there have been any recent significant events in your or your child's life, such as a death or divorce in the family

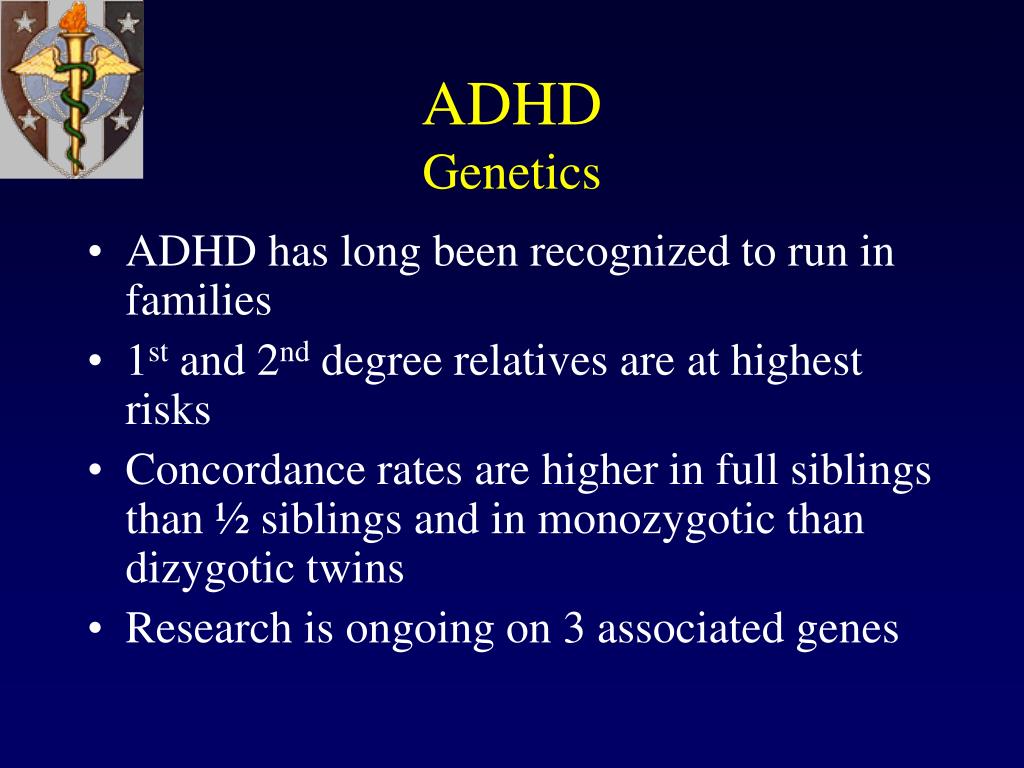

- if there's a family history of ADHD

- about any other problems or symptoms of different health conditions you or your child may have

Next steps

Children and teenagers

If the GP thinks your child may have ADHD, they may first suggest a period of "watchful waiting" – lasting around 10 weeks – to see if your child's symptoms improve, stay the same or get worse.

They may also suggest starting a group-based, ADHD-focused parent training or education programme. Being offered a parent training and education programme does not mean you have been a bad parent – it aims to teach you ways of helping yourself and your child.

See treating ADHD for more information.

If your child's behaviour does not improve, and both you and the GP believe it's affecting their day-to-day life, the GP should refer you and your child to a specialist for a formal assessment.

Adults

For adults with possible ADHD, the GP will assess your symptoms and may refer you for an assessment if:

- you were not diagnosed with ADHD as a child, but your symptoms began during childhood and have been ongoing since

- your symptoms cannot be explained by a mental health condition

- your symptoms significantly affect your day-to-day life – for example, if you're underachieving at work or find intimate relationships difficult

You may also be referred to a specialist if you had ADHD as a child or young person and your symptoms are now causing moderate or severe functional impairment.

Assessment

You or your child may be referred to 1 of the following types of specialist for a formal assessment:

- a specialist child or adult psychiatrist

- a paediatrician – a specialist in children's health

- an appropriately qualified healthcare professional with training and expertise in the diagnosis of ADHD

Who you're referred to depends on your age and what's available in your local area.

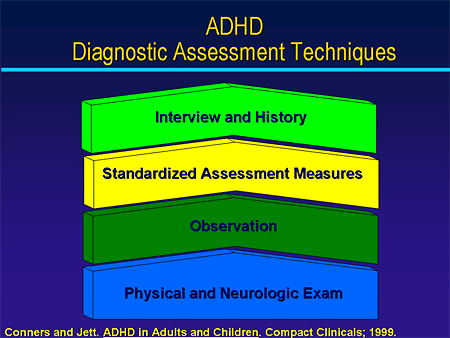

There's no simple test to determine whether you or your child has ADHD, but your specialist can make an accurate diagnosis after a detailed assessment. The assessment may include:

- a physical examination, which can help rule out other possible causes for the symptoms

- a series of interviews with you or your child

- interviews or reports from other significant people, such as partners, parents and teachers

Diagnosis in children and teenagers

Diagnosing ADHD in children depends on a set of strict criteria. To be diagnosed with ADHD, your child must have 6 or more symptoms of inattentiveness, or 6 or more symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsiveness.

To be diagnosed with ADHD, your child must have 6 or more symptoms of inattentiveness, or 6 or more symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsiveness.

Read more about the symptoms of ADHD

To be diagnosed with ADHD, your child must also have:

- been displaying symptoms continuously for at least 6 months

- started to show symptoms before the age of 12

- been showing symptoms in at least 2 different settings – for example, at home and at school, to rule out the possibility that the behaviour is just a reaction to certain teachers or to parental control

- symptoms that make their lives considerably more difficult on a social, academic or occupational level

- symptoms that are not just part of a developmental disorder or difficult phase, and are not better accounted for by another condition

Diagnosis in adults

Diagnosing ADHD in adults is more difficult because there's some disagreement about whether the list of symptoms used to diagnose children and teenagers also applies to adults.

In some cases, an adult may be diagnosed with ADHD if they have 5 or more of the symptoms of inattentiveness, or 5 or more of hyperactivity and impulsiveness, listed in diagnostic criteria for children with ADHD.

As part of your assessment, the specialist will ask about your present symptoms. However, under current diagnostic guidelines, a diagnosis of ADHD in adults cannot be confirmed unless your symptoms have been present from childhood.

If you find it difficult to remember whether you had problems as a child, your specialist may wish to see your old school records, or talk to your parents, teachers or anyone else who knew you well when you were a child.

For an adult to be diagnosed with ADHD, their symptoms should also have a moderate effect on different areas of their life, such as:

- underachieving at work or in education

- driving dangerously

- difficulty making or keeping friends

- difficulty in relationships with partners

If your problems are recent and did not occur regularly in the past, you're not considered to have ADHD. This is because it's currently thought that ADHD cannot develop for the first time in adults.

This is because it's currently thought that ADHD cannot develop for the first time in adults.

Page last reviewed: 24 December 2021

Next review due: 24 December 2024

Symptoms and Diagnosis of ADHD

COVID-19: Information for parenting children with ADHD

Learn more

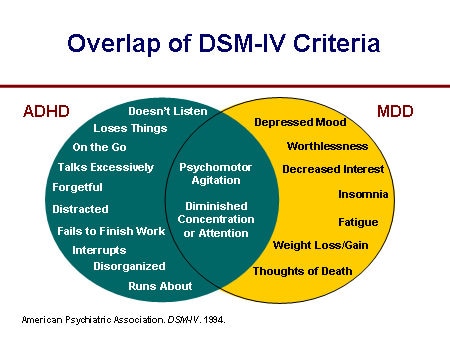

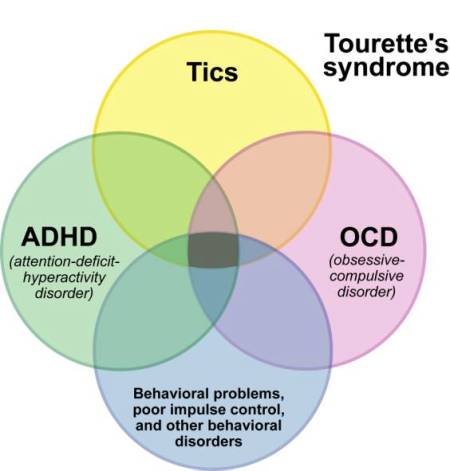

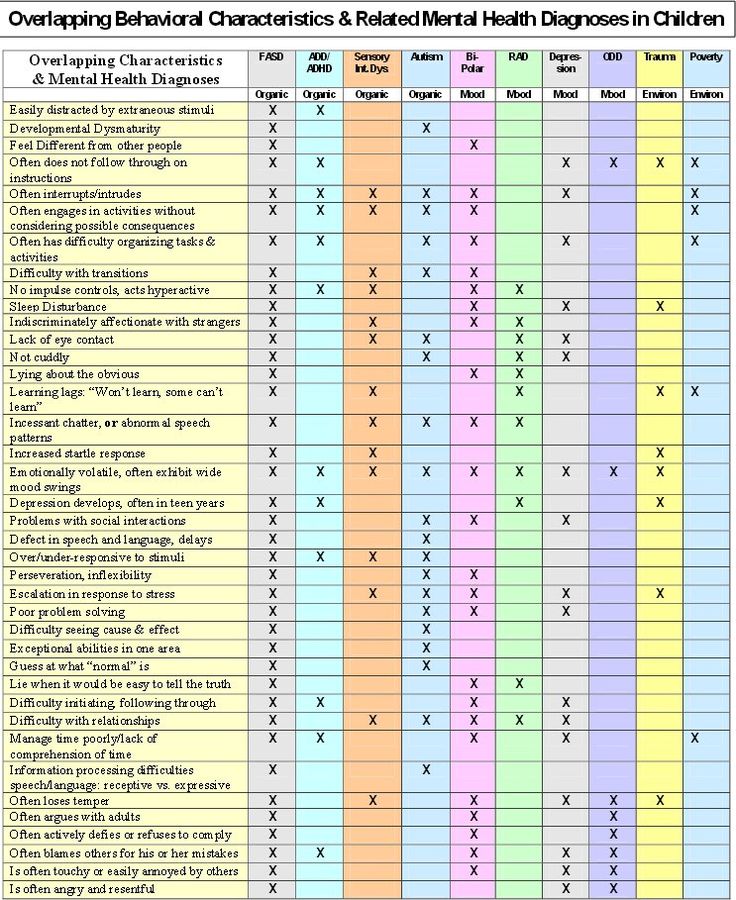

Deciding if a child has ADHD is a process with several steps. This page gives you an overview of how ADHD is diagnosed. There is no single test to diagnose ADHD, and many other problems, like sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, and certain types of learning disabilities, can have similar symptoms.

If you are concerned about whether a child might have ADHD, the first step is to talk with a healthcare provider to find out if the symptoms fit the diagnosis. The diagnosis can be made by a mental health professional, like a psychologist or psychiatrist, or by a primary care provider, like a pediatrician.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that healthcare providers ask parents, teachers, and other adults who care for the child about the child’s behavior in different settings, like at home, school, or with peers. Read more about the recommendations.

Read more about the recommendations.

The healthcare provider should also determine whether the child has another condition that can either explain the symptoms better, or that occurs at the same time as ADHD. Read more about other concerns and conditions.

Why Family Health History is Important if Your Child has Attention and Learning Problems

How is ADHD diagnosed?

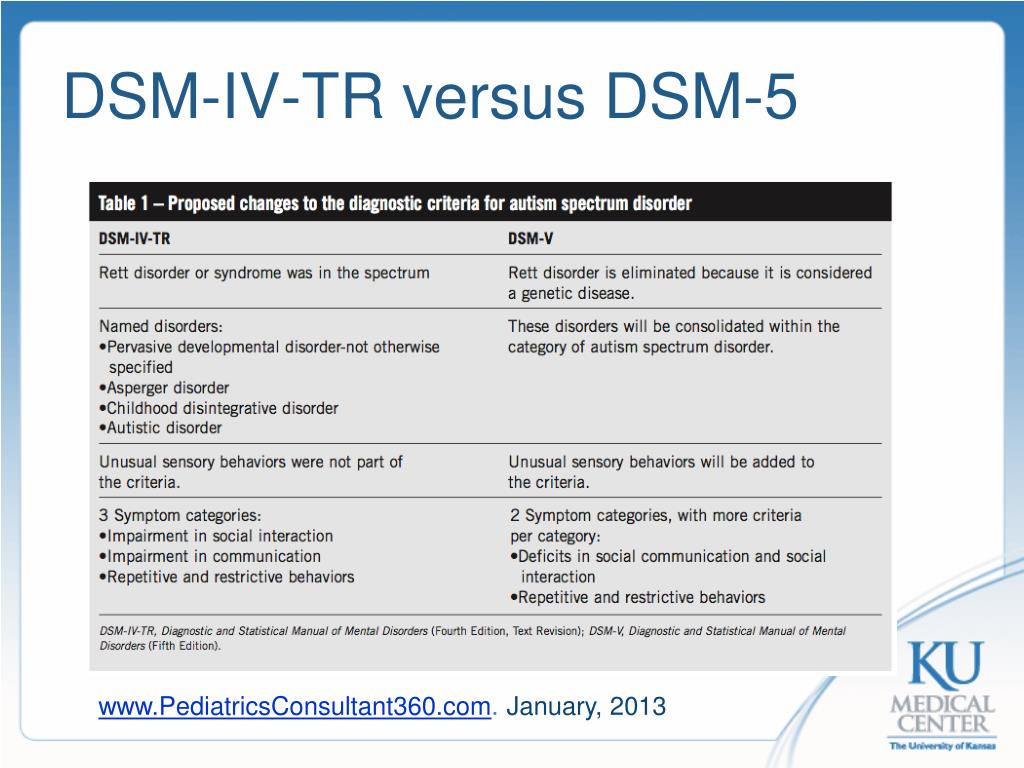

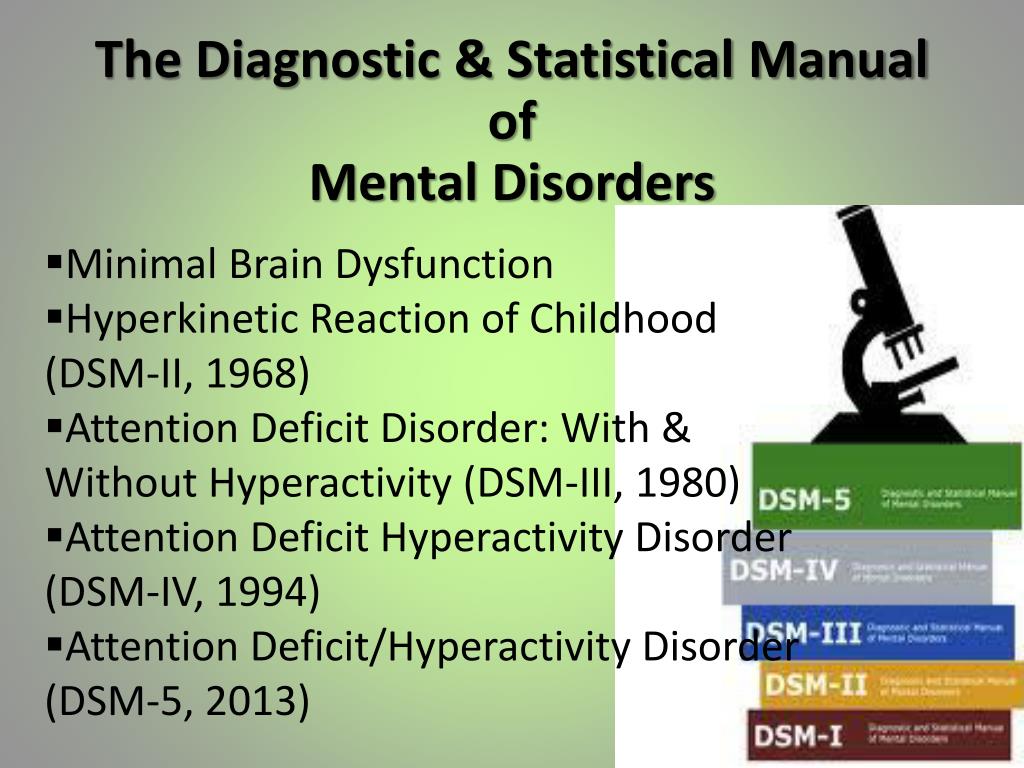

Healthcare providers use the guidelines in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth edition (DSM-5)1, to help diagnose ADHD. This diagnostic standard helps ensure that people are appropriately diagnosed and treated for ADHD. Using the same standard across communities can also help determine how many children have ADHD, and how public health is impacted by this condition.

Here are the criteria in shortened form. Please note that they are presented just for your information. Only trained healthcare providers can diagnose or treat ADHD.

Get information and support from the National Resource Center on ADHD

DSM-5 Criteria for ADHD

People with ADHD show a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development:

- Inattention: Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of inattention have been present for at least 6 months, and they are inappropriate for developmental level:

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

- Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., loses focus, side-tracked).

- Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities.

- Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

- Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

- Is often easily distracted

- Is often forgetful in daily activities.

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

- Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

- Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless).

- Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly.

- Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor”.

- Often talks excessively.

- Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

- Often has trouble waiting their turn.

- Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

In addition, the following conditions must be met:

- Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present before age 12 years.

- Several symptoms are present in two or more settings, (such as at home, school or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities).

- There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, school, or work functioning.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder (such as a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder). The symptoms do not happen only during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder.

Based on the types of symptoms, three kinds (presentations) of ADHD can occur:

- Combined Presentation: if enough symptoms of both criteria inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were present for the past 6 months

- Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: if enough symptoms of inattention, but not hyperactivity-impulsivity, were present for the past six months

- Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: if enough symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, but not inattention, were present for the past six months.

Because symptoms can change over time, the presentation may change over time as well.

Diagnosing ADHD in Adults

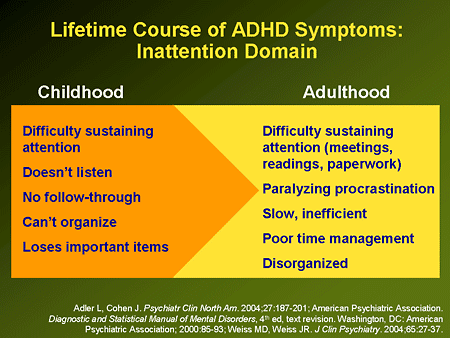

ADHD often lasts into adulthood. To diagnose ADHD in adults and adolescents age 17 years or older, only 5 symptoms are needed instead of the 6 needed for younger children. Symptoms might look different at older ages. For example, in adults, hyperactivity may appear as extreme restlessness or wearing others out with their activity.

To diagnose ADHD in adults and adolescents age 17 years or older, only 5 symptoms are needed instead of the 6 needed for younger children. Symptoms might look different at older ages. For example, in adults, hyperactivity may appear as extreme restlessness or wearing others out with their activity.

For more information about diagnosis and treatment throughout the lifespan, please visit the websites of the National Resource Center on ADHD and the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Reference

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA., American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

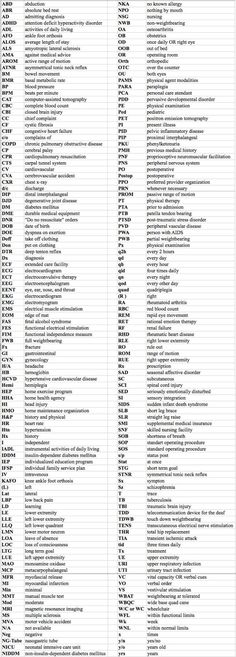

Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale

B Vanderbilt Diagnostic Rating Scale for ADHD (VADRS) psychological assessment tool Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) symptoms and their impact on behavior and academic performance in children aged 6-12 years. This measure was developed by Mark Wohlreich at the Oklahoma Health Sciences Center and includes elements associated with Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorders, Anxiety, and Depression, disorders often associated with ADHD. [1]

[1]

Two versions are available: a parent form with 55 questions and a teacher form with 43 questions. Shortened versions of the VADRS are also available for parents and teachers and consist of 26 questions with an additional 12 measures of side effects. Comparison of scores from different versions of the VADRS with other psychological measures showed that the scores have good but limited reliability and validity across multiple samples. [2] [3] [ minor source required ] However, VADRS has only recently been developed, so the clinical application of this measure is limited.

Content

- 1 Development and History

- 2 Evaluation and interpretation

- 2.1 Parental version

- 2.2 version for teacher

- 3 Reliability

- 5 Infant to

- 6 restrictions

- 7 See also

- 8 Notes

- 9 Recommendations

- 10 further reading

- 11 external link

Development and history

VADRS was developed by Wolraich with the aim of adding common comorbid conditions associated with ADHD that were not present in previous assessments. [1] [4] As public awareness of ADHD has grown, epidemiological studies have shown a prevalence of 4–12% among children aged 6–12 years throughout the United States. Not only is ADHD the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in childhood, but there is also a high rate of comorbidity linking ADHD to other behavioral, emotional, and learning problems and disabilities. [5] Due to the need to obtain a certain sample of the population due to lack of funds, Wohlreich developed the VADRS teacher. Teacher rating scales are important because current diagnostic guidelines require ADHD symptoms to be present in more than one location before a diagnosis can be made.

[1] [4] As public awareness of ADHD has grown, epidemiological studies have shown a prevalence of 4–12% among children aged 6–12 years throughout the United States. Not only is ADHD the most common neurodevelopmental disorder in childhood, but there is also a high rate of comorbidity linking ADHD to other behavioral, emotional, and learning problems and disabilities. [5] Due to the need to obtain a certain sample of the population due to lack of funds, Wohlreich developed the VADRS teacher. Teacher rating scales are important because current diagnostic guidelines require ADHD symptoms to be present in more than one location before a diagnosis can be made.

Evaluation and Interpretation

The Parent-Teacher Rating Scale consists of two components: symptom evaluation and performance impairment. The symptom assessment component identifies symptoms related to the ADHD subtypes of inattention and hyperactivity. To meet the criteria for the diagnosis of ADHD, you need to have 6 positive answers or 9the main symptoms of inattention, or the 9 main symptoms of hyperactivity, or both. [6]

[6]

In both the parent and teacher versions, the respondent is asked to rate the frequency of the child's behavior on a scale from 0 to 3 as follows:

- 0 : "never";

- 1 : "occasionally";

- 2 : "quite often";

- 3 : "very often".

A positive answer is 2 or 3 points (from "often" to "very often").

The last 8 questions of both versions ask the respondent to rate the child's performance in school and his or her interactions with others on a scale of 1 to 5, where 1-2 means "above average", 3 means "average" and 4-5 means "problem ".

To meet the criteria for ADHD, there must be at least one score for a set of indicators that is 4 or 5, as these scores indicate worsening indicators.

Parental version

Parental version of the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale contains 6 subscales. [7] Behavior is included in the total for each subscale if they score 2 or 3. The scoring rules are as follows:

The scoring rules are as follows:

- ADHD inattentive type : Must score 2 or 3 on six or more items in questions 1 -9, and score 1 or 2 on any item in the performance section.

- ADHD hyperactive/impulsive type: Must score 2 or 3 on six or more items in questions 10-18, and score 1 or 2 on any item in the performance section.

- Combined ADHD type: Meets criteria for inattentive ADHD type and hyperactive/impulsive type.

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD): Must score 2 or 3 on four or more items in questions 19-26.

- Conduct disorders : Must score 2 or 3 on three or more items in questions 27-40.

- Anxiety/depression: Must score 2 or 3 on three or more items in questions 41-47.

Teacher version

Teacher version of the Vanderbilt ADHD Diagnostic Rating Scale contains 5 subscales. [7] Behaviors are included in the total for each subscale if they score 2 or 3. A score of 1 or 2 on at least one question in the performance section indicates a violation. The scoring rules are as follows:

A score of 1 or 2 on at least one question in the performance section indicates a violation. The scoring rules are as follows:

- Inattentive ADHD : Must score 2 or 3 on six or more items in questions 1-9.

- ADHD hyperactive/impulsive type: Score 2 or 3 on six or more items in questions 10-18.

- Combined ADHD type: Meets the criteria for inattentive ADHD type and hyperactive/impulsive type.

- Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD): Must score 2 or 3 on three or more items in Question 19-28.

- Anxiety/depression: Score 2 or 3 on three or more items in questions 29-35.

Reliability

| Criterion | Evaluation (adequately, well, excellent, excellent, too well [b] 9000) with links | |

|---|---|---|

| Standards | TBD | Rates were collected for large samples of children in elementary school with a teacher version, but rates for a clinical sample were not reported. [1] [1] |

| Internal consistency (Cronbach's alpha, split half, etc.) | Good | Cronbach's alpha was over 0.90 across all subscales in many studies. [1] [2] |

| Inter-rater reliability | TBD | Meta-analysis showed low inter-rater reliability between parent and teacher VADRS scores, but more research is needed to analyze inter-rater reliability relative to the new VADRS. [1] |

| Test-retest reliability | Adequate | Bard's meta-analysis, which extrapolated from the data, demonstrated that retest reliability is greater than 0.80 for all pooled scores in elementary school populations over a period of about a year. |

| Test repeatability | TBD | Test repeatability data was not collected. |

Validity of

| Action content | Good | VADRS contains items typical of ADHD scores, which are also based on DSM-IV criteria, in addition to items related to other behaviors and disorders likely in children, such as general school functioning and frustration behavior. [1] [1] |

| Construct validity (e.g., predictive, parallel, convergent, and discriminant validity) | Good | Parent-teacher versions of VADRS showed high concurrent validity with those with anxiety subscales such as C-DISC -IV, in clinical and non-clinical samples. [2] |

| Discriminatory validity | Good | VADRS showed good sensitivity (0.80) and adequate specificity (0.75) compared to diagnoses based on a structured interview with some teacher confirmation. [9] |

| Generalization of reality | Adequate | The published data on VADRS were mainly from Oklahoma, so more research is needed to monitor the use of this indicator in different settings and with different demographics. However, the samples were carefully collected and analyzed. |

| Treatment responsiveness | TBD | Sources not yet cited. |

| Clinical usefulness | Good | Recommended by the National Institute for the Quality of Children's Health and the American Academy of Pediatrics, and it has become widely used. |

Impact

High comorbidity of learning disabilities (LDs) in children with ADHD, and for this reason VADRS was studied to determine whether performance element questions in VARS could reliably predict whether a child with ADHD had comorbid LDs ( e.g. math, reading, spelling). Receiver Performance Characteristics Analysis (ROC) results indicate that children with ADHD can be reliably excluded from concomitant LD based on performance scores in VARS. This is clinically useful as it allows for the exclusion of those who do not have LD and therefore reduces unnecessary referrals to healthcare professionals. [10]

First edition limitations

At the time of publication, VADRS was a fairly new tool. Test standardization procedures were completed for a limited range of populations, normative data were developed only for the teacher version, and comorbidity subscales were not based on DSM-IV. The current version of VADRS, now the third edition, has been adapted for DSM-5 criteria. [11]

[11]

See also

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder 9 A C D 9000 Ohan, Jeneva L.; Myers, Kathleen M. (September 2003). “A Ten-Year Review of Rating Scales. V: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Scales. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 9Wolraich, Mark L .; Lambert, Warren; Doffing, Melissa A.; Beekman, Leonard; Simmons, Tonya; Worley, Kim (December 1, 2003). "Psychometric Properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD Parental Diagnostic Rating Scale in a Specified Population". Journal of Child Psychology . 28 (8): 559–568. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046. ISSN 0146-8693. PMID 14602846.9 "NICHQ Vanderbilt Rating Scales (archived)."

- Becker, S.P.; Langberg, J.M.; Vaughn, A.J.; Epstein, J. N. (2012). "Clinical usefulness of screening scales for diagnosing comorbidity on the ADHD Parental Diagnostic Scale".

Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics . 33 (3): 221–228. Doi:10.1097 / DBP.0b013e318245615b. PMC 3319856. PMID 22343479.

Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics . 33 (3): 221–228. Doi:10.1097 / DBP.0b013e318245615b. PMC 3319856. PMID 22343479. - Wolraich, M.; Lambert, W.; Doffing, M.; Bickman, L.; Simmons, T.; Worley, K. (2003). "Psychometric Properties of the Vanderbilt ADHD Parental Diagnostic Rating Scale in a Specified Population". Journal of Child Psychology . 28 (8): 559–568. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsg046. PMID 14602846.

- Plischka, Steven; AACAP Quality Working Group (July 2007). "A practical parameter for the evaluation and treatment of children and adolescents with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . 46 (7): 894–921. Doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e318054e724. PMID 17581453.

- Parent (55 position) version

- VADRS (parent version) - online version with automatic scoring

- VADRS (original version) - PDF

- VADRS (Supplementary version for parents) - PDF

- VADRS (Parent Version) - Grading Instructions - PDF

- Teacher Version (43 items)

- VADRS (Teacher Version) - PDF

- VADRS (Teacher Version) - PDF

- Vadrs (version for the teacher) - instructions for setting assessments - PDF

- Other

- Effectivechildarapy.

org management for ADHD

org management for ADHD - ADS for adults

- Effectivechildarapy.

- - Civilized intellectual communication

- - No personal attacks

- - No policy

further reading

external link

Authorization

Forgot password

Remember me

Register now

The SDVG.LIFE website is a continuation of the book and therefore new materials must meet the same standards as the book.

Hence the rules for discussion participants:

Pre-moderation has been introduced for the first few posts.

Welcome!

Create account

ADD(H) test for adults

ADD(H) test for adolescents and adults 17 years of age and older, in accordance with the methodology of the American DSM-V guide.

Number of questions: 18 .

For more information, see the article from the Notes.

. ..

..

To answer "Yes", the symptom must be:

- Stable during the last 6 months .

- Was expressed in measure not corresponding to the level of development .

- Had a negative impact on academic performance and/or professional activities .

...

The test is provided for informational purposes and is not intended to diagnose any disease.

Consult a physician for diagnosis.

...

one

Often makes nervous movements with the hands or feet, or fidgets and wriggles while sitting in a chair.

Yes

No

2

Often interrupts or annoys others.

For example, breaks into conversation, games, or activities without invitation; can use other people's things without asking; for teenagers or adults - they can interfere with someone else's work or continue someone else's work themselves.

Yes

No

3

Often has difficulty waiting in line.

For example, in the shop or at the game.

Yes

No

four

Often blurts out an answer before the question has been fully asked.

For example, completes sentences when others are speaking; cannot wait for their turn to join the conversation.

Yes

No

5

Often too talkative.

Yes

No

6

It is often in constant motion and behaves as if a motor was attached to it.

For example, absolutely unable or unable to stay comfortably in one place in restaurants or meetings; perhaps people around him consider him a restless person or a person with whom it is difficult to deal with.

Yes

No

7

Often has difficulty playing or spending time quietly.

Yes

No

eight

Often runs back and forth without restraint or climbs in situations where this is unacceptable.

Note: Teenagers and adults may not be running, jumping or climbing but may be restless and out of sorts.

Yes

No

9

Often leaves his seat in class or in other situations where the person is expected to be seated.

For example, leaving one's seat in a classroom, in an office or other place of work, or in other situations where one is expected to be seated.

Yes

No

ten

Often fails to pay due attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, work, and other activities.

For example, does not notice or skips details, work is done inaccurately.

Yes

No

eleven

Often forgetful in daily activities.

For example, forgetfulness in housework, while doing errands; for older teenagers and adults - they forget to return calls, pay bills, come to a meeting or appointment (to a doctor, for example).

Yes

No

12

Often easily distracted by extraneous stimuli. For older teenagers and adults, this includes thoughts that are inappropriate for the time / place.

Yes

No

13

Often loses things needed for lessons or classes.

For example, notebooks, textbooks, pencils, books, tools, keys, paper forms, glasses, mobile phones.

Yes

No

fourteen

Often avoids, dislikes, or reluctantly takes on things that require sustained mental effort.

For example, school assignments or school homework, for older teens and adults - preparing reports, filling out forms, studying long texts.