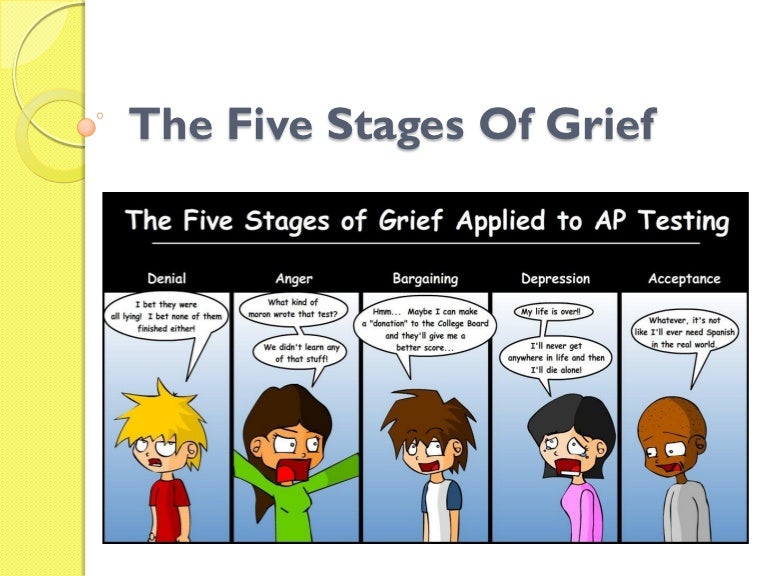

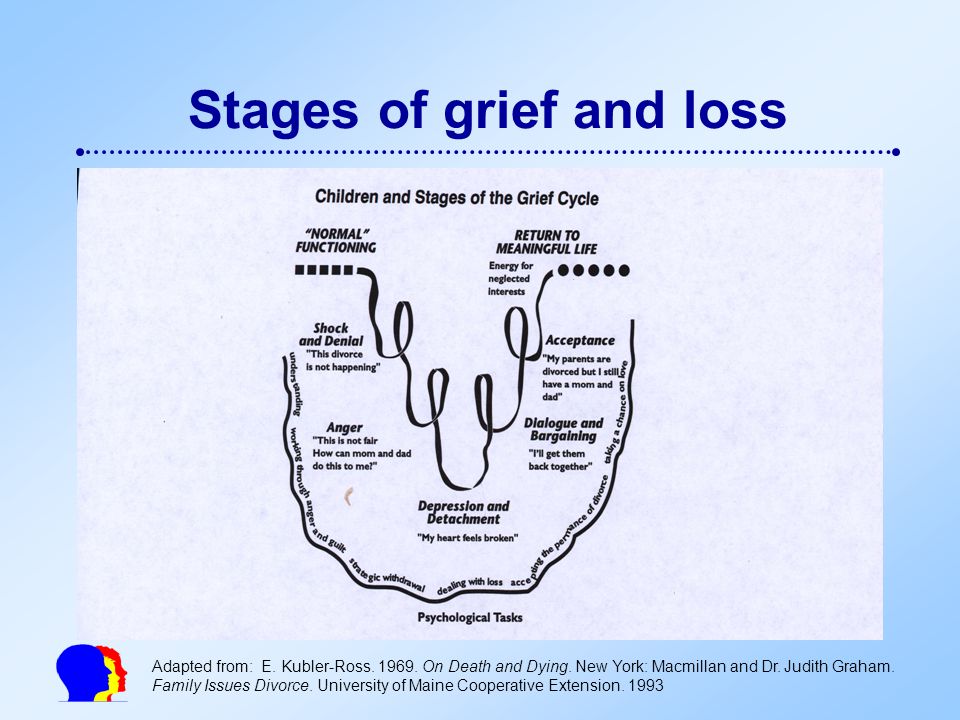

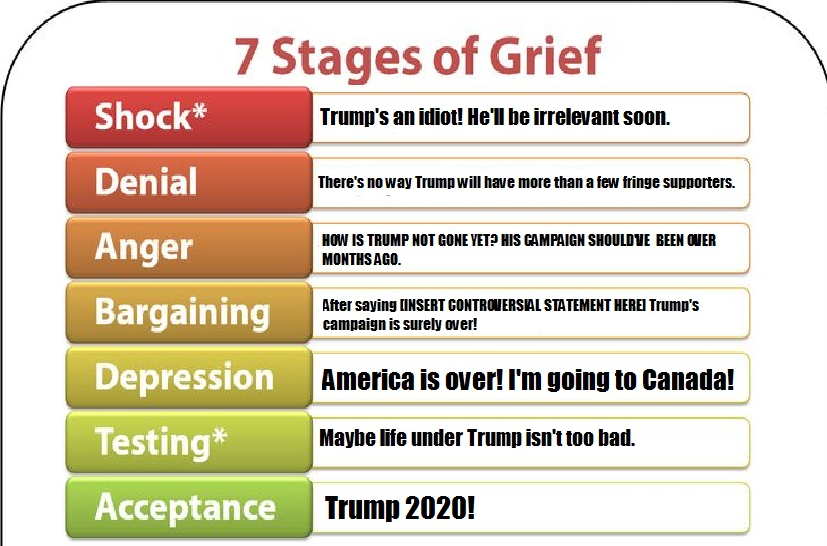

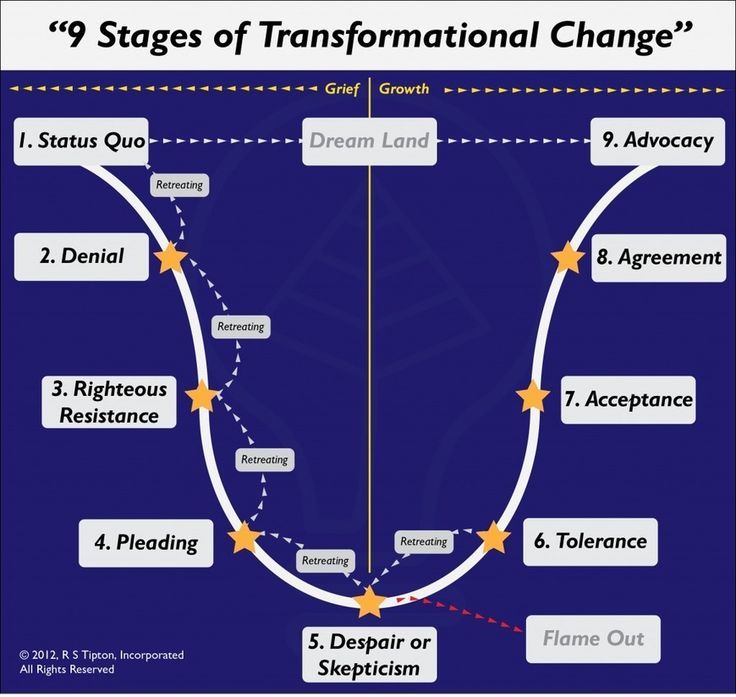

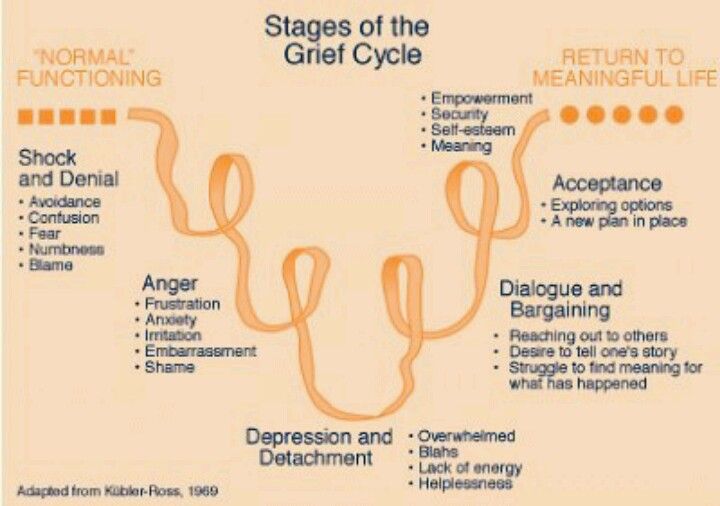

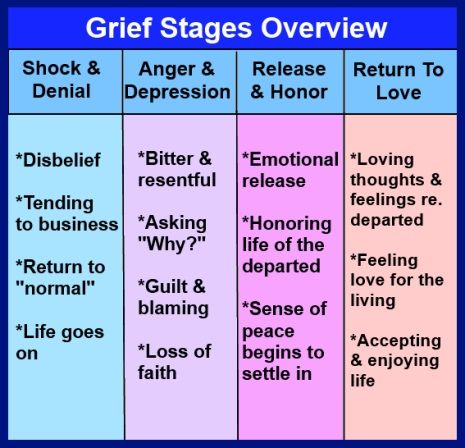

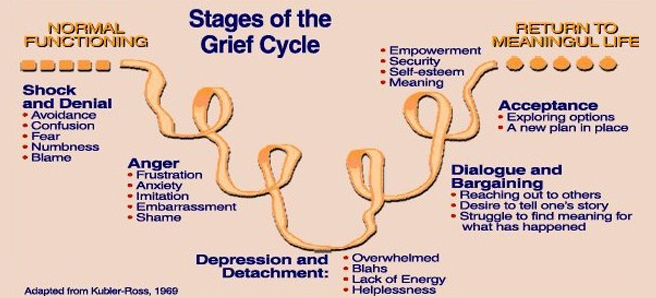

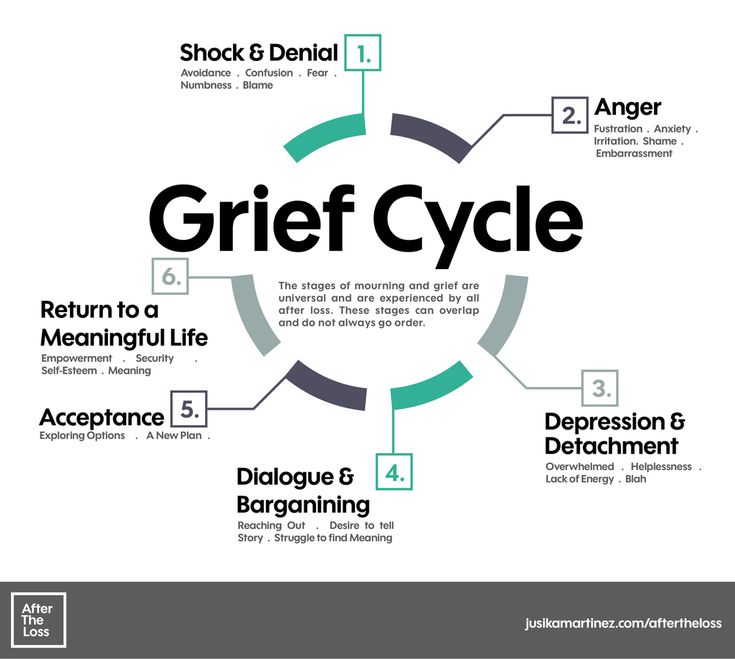

The grieving process involves several stages

Five Stages of Grief by Elisabeth Kubler Ross & David Kessler

A Message from David Kessler

I was privileged to co-author two books with the legendary, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, as well as adapt her well-respected stages of dying for those in grief. As expected, the stages would present themselves differently in grief. In our book, On Grief and Grieving we present the adapted stages in the much needed area of grief. The stages have evolved since their introduction and have been very misunderstood over the past four decades. They were never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages. They are responses to loss that many people have, but there is not a typical response to loss as there is no typical loss.

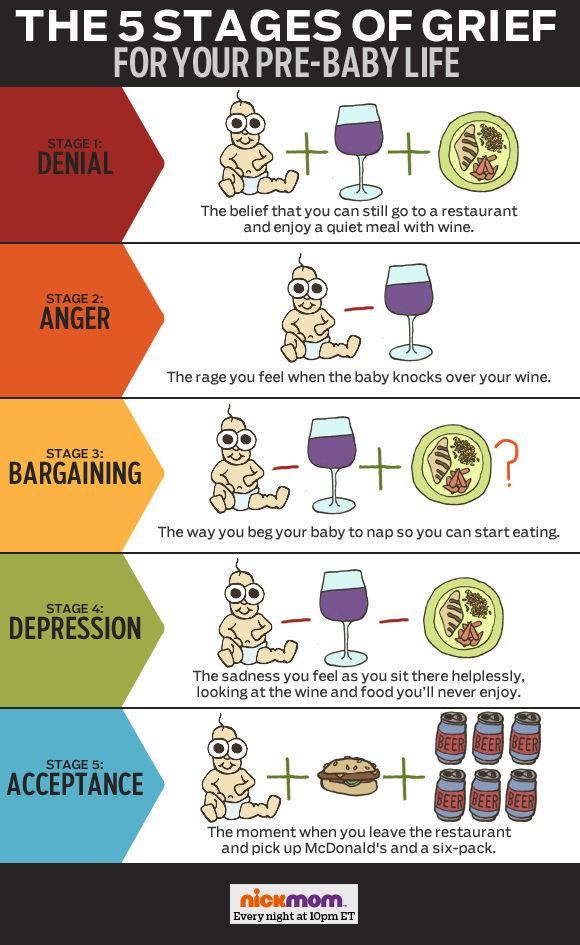

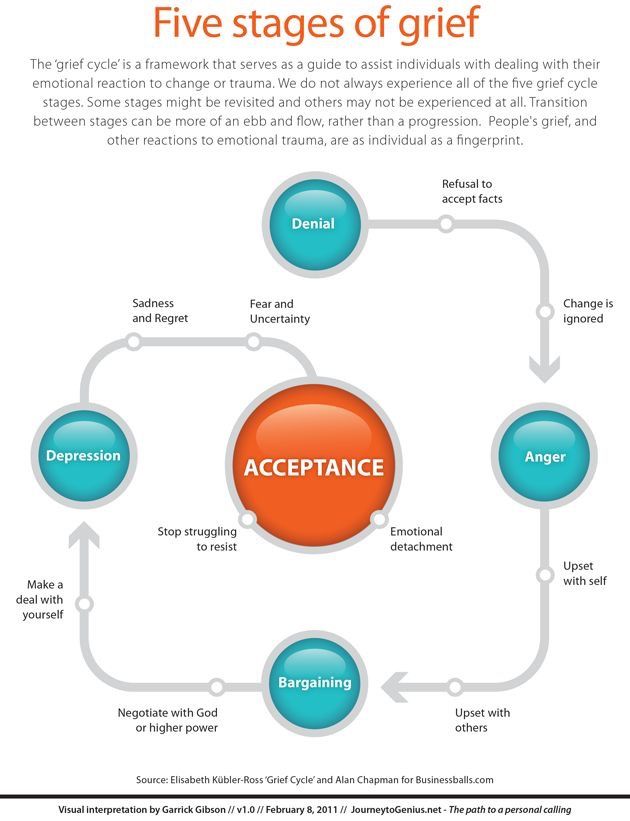

The five stages, denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance are a part of the framework that makes up our learning to live with the one we lost. They are tools to help us frame and identify what we may be feeling. But they are not stops on some linear timeline in grief. Not everyone goes through all of them or in a prescribed order. Our hope is that with these stages comes the knowledge of grief ‘s terrain, making us better equipped to cope with life and loss. At times, people in grief will often report more stages. Just remember your grief is an unique as you are.

NEW BOOK

Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief

In this groundbreaking new work, David Kessler—an expert on grief and the coauthor with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross of the iconic On Grief and Grieving—journeys beyond the classic five stages to discover a sixth stage: meaning.

In this book, Kessler gives readers a roadmap to remembering those who have died with more love than pain; he shows us how to move forward in a way that honors our loved ones. Kessler’s insight is both professional and intensely personal. His journey with grief began when, as a child, he witnessed a mass shooting at the same time his mother was dying. For most of his life, Kessler taught physicians, nurses, counselors, police, and first responders about end of life, trauma, and grief, as well as leading talks and retreats for those experiencing grief. Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

Despite his knowledge, his life was upended by the sudden death of his twenty-one-year-old son.

How does the grief expert handle such a tragic loss? He knew he had to find a way through this unexpected, devastating loss, a way that would honor his son. That, ultimately, was the sixth state of grief—meaning. In Finding Meaning, Kessler shares the insights, collective wisdom, and powerful tools that will help those experiencing loss. Read More

DENIAL Denial is the first of the five stages of grief™️. It helps us to survive the loss. In this stage, the world becomes meaningless and overwhelming. Life makes no sense. We are in a state of shock and denial. We go numb. We wonder how we can go on, if we can go on, why we should go on. We try to find a way to simply get through each day. Denial and shock help us to cope and make survival possible. Denial helps us to pace our feelings of grief. There is a grace in denial. It is nature’s way of letting in only as much as we can handle. As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

As you accept the reality of the loss and start to ask yourself questions, you are unknowingly beginning the healing process. You are becoming stronger, and the denial is beginning to fade. But as you proceed, all the feelings you were denying begin to surface.

ANGERAnger is a necessary stage of the healing process. Be willing to feel your anger, even though it may seem endless. The more you truly feel it, the more it will begin to dissipate and the more you will heal. There are many other emotions under the anger and you will get to them in time, but anger is the emotion we are most used to managing. The truth is that anger has no limits. It can extend not only to your friends, the doctors, your family, yourself and your loved one who died, but also to God. You may ask, “Where is God in this? Underneath anger is pain, your pain. It is natural to feel deserted and abandoned, but we live in a society that fears anger. Anger is strength and it can be an anchor, giving temporary structure to the nothingness of loss. At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

At first grief feels like being lost at sea: no connection to anything. Then you get angry at someone, maybe a person who didn’t attend the funeral, maybe a person who isn’t around, maybe a person who is different now that your loved one has died. Suddenly you have a structure – – your anger toward them. The anger becomes a bridge over the open sea, a connection from you to them. It is something to hold onto; and a connection made from the strength of anger feels better than nothing.We usually know more about suppressing anger than feeling it. The anger is just another indication of the intensity of your love.

BARGAININGBefore a loss, it seems like you will do anything if only your loved one would be spared. “Please God, ” you bargain, “I will never be angry at my wife again if you’ll just let her live.” After a loss, bargaining may take the form of a temporary truce. “What if I devote the rest of my life to helping others. Then can I wake up and realize this has all been a bad dream?” We become lost in a maze of “If only…” or “What if…” statements. We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion. We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

We want life returned to what is was; we want our loved one restored. We want to go back in time: find the tumor sooner, recognize the illness more quickly, stop the accident from happening…if only, if only, if only. Guilt is often bargaining’s companion. The “if onlys” cause us to find fault in ourselves and what we “think” we could have done differently. We may even bargain with the pain. We will do anything not to feel the pain of this loss. We remain in the past, trying to negotiate our way out of the hurt. People often think of the stages as lasting weeks or months. They forget that the stages are responses to feelings that can last for minutes or hours as we flip in and out of one and then another. We do not enter and leave each individual stage in a linear fashion. We may feel one, then another and back again to the first one.

DEPRESSIONAfter bargaining, our attention moves squarely into the present. Empty feelings present themselves, and grief enters our lives on a deeper level, deeper than we ever imagined. This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever. It’s important to understand that this depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone? Why go on at all? Depression after a loss is too often seen as unnatural: a state to be fixed, something to snap out of. The first question to ask yourself is whether or not the situation you’re in is actually depressing. The loss of a loved one is a very depressing situation, and depression is a normal and appropriate response. To not experience depression after a loved one dies would be unusual. When a loss fully settles in your soul, the realization that your loved one didn’t get better this time and is not coming back is understandably depressing. If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

This depressive stage feels as though it will last forever. It’s important to understand that this depression is not a sign of mental illness. It is the appropriate response to a great loss. We withdraw from life, left in a fog of intense sadness, wondering, perhaps, if there is any point in going on alone? Why go on at all? Depression after a loss is too often seen as unnatural: a state to be fixed, something to snap out of. The first question to ask yourself is whether or not the situation you’re in is actually depressing. The loss of a loved one is a very depressing situation, and depression is a normal and appropriate response. To not experience depression after a loved one dies would be unusual. When a loss fully settles in your soul, the realization that your loved one didn’t get better this time and is not coming back is understandably depressing. If grief is a process of healing, then depression is one of the many necessary steps along the way.

ACCEPTANCEAcceptance is often confused with the notion of being “all right” or “OK” with what has happened. This is not the case. Most people don’t ever feel OK or all right about the loss of a loved one. This stage is about accepting the reality that our loved one is physically gone and recognizing that this new reality is the permanent reality. We will never like this reality or make it OK, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. We must try to live now in a world where our loved one is missing. In resisting this new norm, at first many people want to maintain life as it was before a loved one died. In time, through bits and pieces of acceptance, however, we see that we cannot maintain the past intact. It has been forever changed and we must readjust. We must learn to reorganize roles, re-assign them to others or take them on ourselves. Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies.

This is not the case. Most people don’t ever feel OK or all right about the loss of a loved one. This stage is about accepting the reality that our loved one is physically gone and recognizing that this new reality is the permanent reality. We will never like this reality or make it OK, but eventually we accept it. We learn to live with it. It is the new norm with which we must learn to live. We must try to live now in a world where our loved one is missing. In resisting this new norm, at first many people want to maintain life as it was before a loved one died. In time, through bits and pieces of acceptance, however, we see that we cannot maintain the past intact. It has been forever changed and we must readjust. We must learn to reorganize roles, re-assign them to others or take them on ourselves. Finding acceptance may be just having more good days than bad ones. As we begin to live again and enjoy our life, we often feel that in doing so, we are betraying our loved one. We can never replace what has been lost, but we can make new connections, new meaningful relationships, new inter-dependencies. Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Instead of denying our feelings, we listen to our needs; we move, we change, we grow, we evolve. We may start to reach out to others and become involved in their lives. We invest in our friendships and in our relationship with ourselves. We begin to live again, but we cannot do so until we have given grief its time.

Learn More About The Five Areas of Grief

Watch The FREE Video Now Click Here

Books About the Five Stages by Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and David Kessler

Download Chapter One Click Here

Download Chapter One Click Here

What they are, how long, how to cope

The stages of the grieving process include shock, denial, anger, bargaining, depression, testing, and acceptance. This process helps people heal after experiencing loss.

Symptoms of grief usually resolve after 1–2 years.

If a person has a loved one or friend who is experiencing grief, they can help them cope in various ways. These include offering a listening ear or volunteering to provide a service, such as running errands or preparing a meal.

Additionally, local and national support groups may be an invaluable source of comfort and companionship to those who have experienced a loss.

Read on to learn about the stages of the grieving process, types of grief, how to offer support, and more.

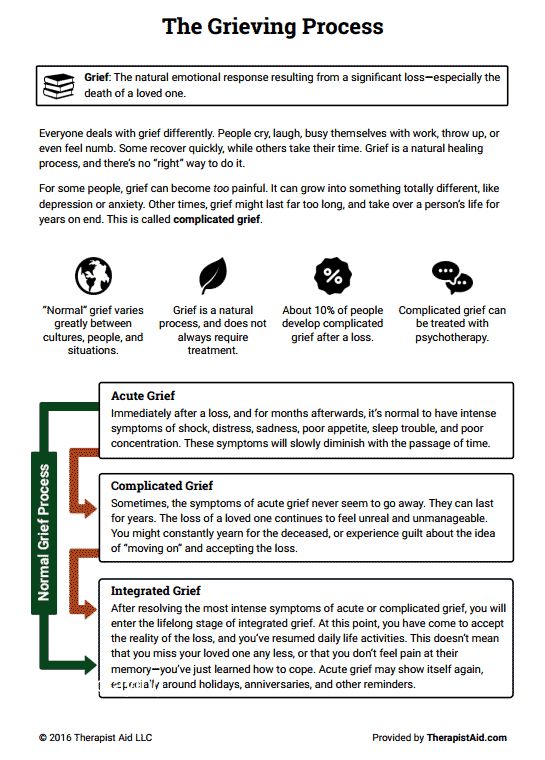

Grief is a natural experience that helps a person process the pain of loss and move toward healing.

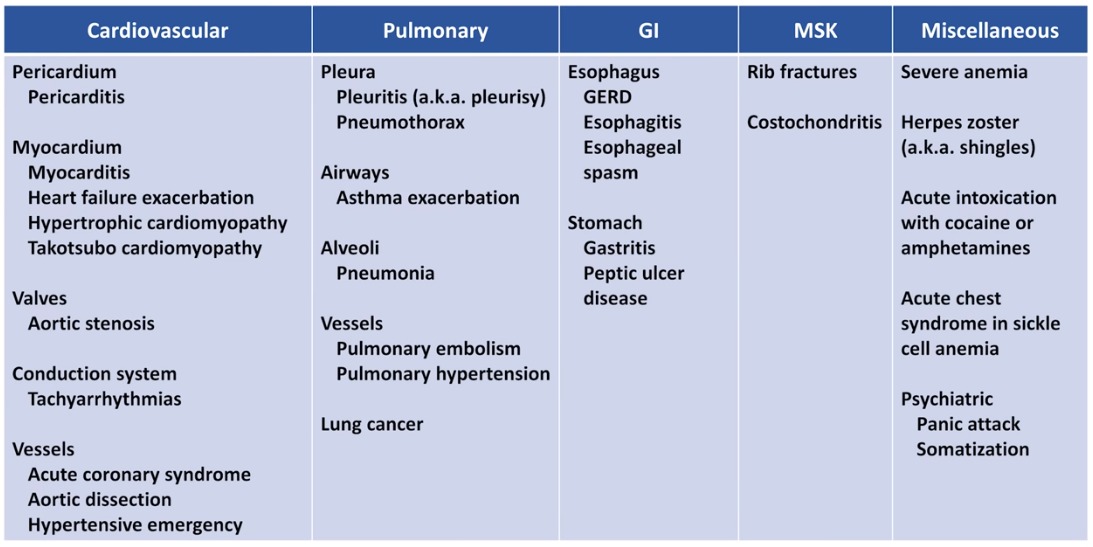

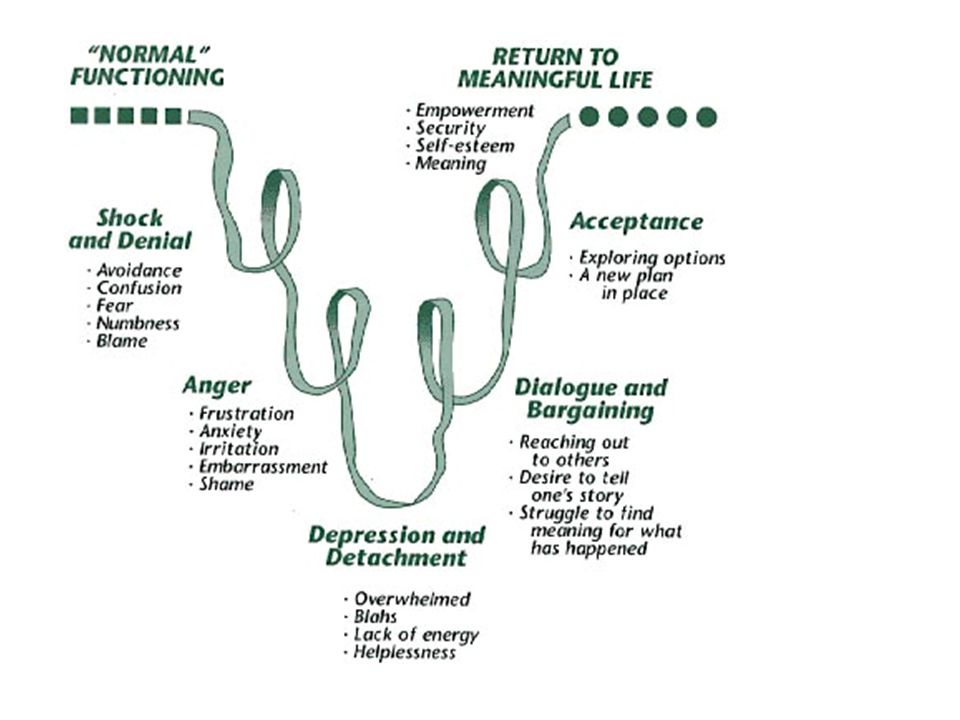

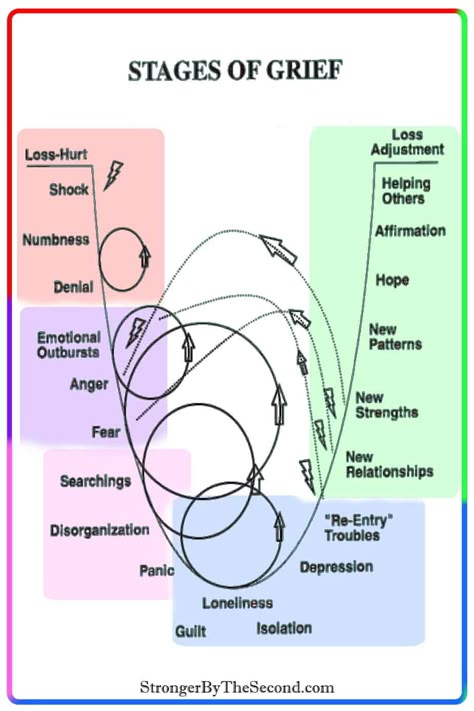

The stages of grief are not necessarily linear, which means people may not go through them in order. However, research notes that, in general, there are seven stages. They consist of the following:

1. Shock

This stage may involve numbed disbelief in response to news of a loss. It may serve as an emotional buffer to prevent someone from feeling overwhelmed.

2. Denial

Denial may entail refuting the reality of the loss or any associated feelings. Once an individual accepts reality, they can move forward through the healing process.

Shock and denial help people manage the immediate aftermath of a loss.

3. Anger

During this stage, an individual may direct their anger toward the person who died, doctors, family members, or even religious entities.

This replaces the numbness of shock and denial. It is important to address the anger.

4. Bargaining

Bargaining involves thoughts such as “I will do anything if you take away the pain.”

This stage may come at any point within the grieving process. It is frequently accompanied by guilt.

5. Depression

At this stage, a person may experience feelings of emptiness and intense sadness. They may also withdraw from daily activities and things they once enjoyed.

While this stage is difficult, it is a necessary step toward healing.

6. Testing

Testing is the process of trying to find solutions that offer a means of dealing with loss. Someone may drift in and out of other grieving stages during this time.

7. Acceptance

This is the final stage of the grieving process. Acceptance does not mean people feel OK about a loss. Rather, it means they realize the loss is their new reality. They understand that while life will not continue as it did before, it will go on.

Acceptance does not mean people feel OK about a loss. Rather, it means they realize the loss is their new reality. They understand that while life will not continue as it did before, it will go on.

This stage may involve reorganizing roles and forming new relationships.

The grieving process has no set duration, and people move through each stage at varying rates.

Symptoms of grief largely resolve after 1–2 years. However, this timeline is different for everyone. Additionally, rather than experiencing a steady decline in grief, a person’s emotions tend to fluctuate over time and come in waves.

It is common for reactions to grief to resurge after many years in response to triggers, which may include:

- birthdays

- special events

- holidays

- songs

Research from 2020 describes the various types of grief. They include:

Anticipatory grief

This is what a person feels when they expect a loss that has not yet happened. It includes many of the same emotions someone experiences after a loss.

It includes many of the same emotions someone experiences after a loss.

Anticipatory grief is more likely in individuals with dependent relationships or limited social support.

‘Normal’ or common grief

Normal grief is a gradual progression toward acceptance. It happens about in 50–85% of people following a loss.

Although people experience difficult emotions, they retain the ability to continue everyday activities. They might have emotional distress, such as crying, low mood, and longing.

Complicated grief

Complicated grief happens in 15–30% of people who experience a loss. It resembles conditions such as depression and generalized anxiety disorder.

It may deviate from normal grief in the following ways:

- Absent or inhibited grief: This is a pattern of manifesting little evidence of distress or yearning.

- Delayed grief: This is a pattern where symptoms occur much later than is typical.

- Chronic grief: This is a pattern where symptoms persist over a prolonged duration.

- Distorted grief: This is a pattern of extremely intense symptoms.

Persistent, prolonged, or complex grief

This is a type of complicated grief that involves intense sorrow after 12 months have passed — or 6 months for children and adolescents. The intensity and pervasiveness of the reactions can cause disability.

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition, text revision recognizes prolonged grief as an independent disorder.

It can be challenging to help family, friends, or loved ones who are grieving. People can offer support by:

- Offering a listening ear: A person can remind someone who is grieving that they are available to listen whenever they feel like talking about how they feel or sharing memories.

- Finding practical ways to help: Instead of saying, “Let me know if I can do anything for you,” volunteer to help in specific ways. This could involve preparing a meal, running errands, or helping with child care.

- Assuring them that their feelings are valid: Remember that the sadness can linger in some people for quite some time after a loss. Some days will be better than others.

To support a grieving child, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommend:

- asking the child questions to assess their emotional state and understanding of the loss

- maintaining the child’s routine as much as possible

- allowing the child time to express their feelings

- spending time with the child doing things they enjoy

Support groups may provide comfort, companionship, and validation. They can also serve as a source of practical information.

A person can find groups in their community through community centers, hospices, places of worship, and hospitals.

Additionally, the following national resources may help:

- Hope for Bereaved: This offers services and support groups for people who are grieving.

- AARP’s Grief and Loss: The AARP provides articles and tools for coping with grief.

- The Compassionate Friends: This is a resource with online and local support groups for those who have lost a child.

- National Widowers Organization: This group supports those who have lost their wives.

- Dougy Center: This is a resource for support groups and education for children and teenagers who are grieving.

- What’s Your Grief?: This is a resource for those who are grieving, as well as those who are supporting someone who is grieving.

Mourning is a natural process, but it can be harmful if it goes on too long. If a person’s sadness prevents them from engaging in their everyday activities, they should contact a doctor.

Additionally, if an individual has signs of complicated grief — such as the inability to find meaning in life — they may need professional help.

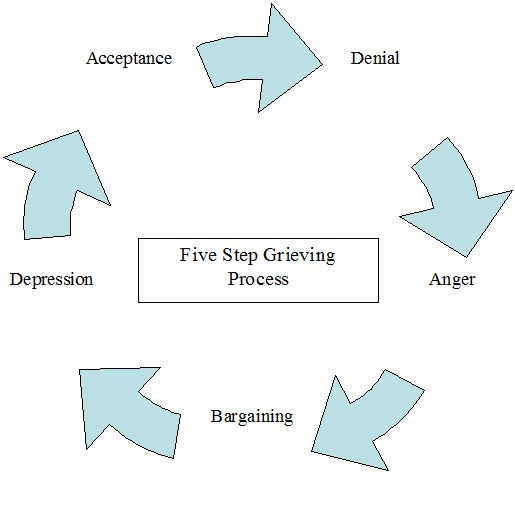

The stages of the grieving process include shock, denial, anger, bargaining, depression, testing, and acceptance. However, people do not always go through the process in this particular order, and some steps last longer than others.

However, people do not always go through the process in this particular order, and some steps last longer than others.

Grief symptoms largely diminish after 1–2 years, but they may reappear years later in response to certain triggers, such as birthdays. Although grieving is normal, if the symptoms interfere with daily life, it is time to talk with a doctor.

Five Stages of Grief

Understanding the grieving process can be helpful if you or a loved one is experiencing a loss. Here we look at the 5 stages of grief, as well as several strategies for helping those who are grieving after a death or separation.

It is important to remember that the process of mourning can be complex and vary from person to person. These stages may not be entirely sequential, or you may experience more emotion after you think you've passed them. Allowing yourself to grieve according to your own ideas will help you recover from the loss.

The Five Stages of Grief

Elisabeth Kübler Ross, a psychiatrist, introduced the five stages of grief. They say that after the death of a loved one, we experience five distinct phases of grief. These stages include denial, anger, bargaining, despair, and acceptance.

They say that after the death of a loved one, we experience five distinct phases of grief. These stages include denial, anger, bargaining, despair, and acceptance.

Denial

In the first phase of the mourning process, denial serves to lessen the intensity of grief from the loss. In addition to processing the truth about loss, we try to process emotional suffering. It can be difficult to accept the fact that a significant person in your life has died, especially if you just hung out with them in the week or even the day before they died.

During this period of mourning, our world is completely changing. Thoughts may take time to adjust to the new reality. We think about what we experienced with the person we lost and worry about how to live without him.

We have a lot of information to learn and interpret images. Denial seeks to slow down this process and take us through it step by step, rather than risk our emotions overpowering us.

Anger

Anger is the second stage of grief. We are trying to adapt to the new world, while probably experiencing significant mental anguish. We have so much information to process that anger can feel like an emotional release.

We are trying to adapt to the new world, while probably experiencing significant mental anguish. We have so much information to process that anger can feel like an emotional release.

Remember that rage doesn't have to be extremely vulnerable. However, in social terms, it may seem more acceptable than the recognition of fear. Anger allows us to express our feelings without fear of criticism or rejection.

In addition, anger is often the first feeling we experience when we begin to release the emotions associated with a loss. This can make us feel alone in our experiences. At times when comfort, companionship, and confidence can be helpful, anger can also make us seem unapproachable to others.

Bargaining

It is not uncommon for you to feel so desperate when you are experiencing a loss that you are ready to do anything to lessen or alleviate the pain. At this stage of grief, you may try to negotiate a change in circumstances by promising to do something in exchange for being relieved of the pain.

When the "bidding" begins, we often turn our demands to a higher power or to something greater than ourselves, which can influence a different outcome. During times of mourning, negotiations may take the form of several promises, including:

- "If God can heal this man, I will change my life."

- "I'll be a better person if you let this person live."

- "If you can prevent him or her from dying or leaving me, I will never be furious again."

Bargaining arises from a sense of powerlessness and gives us the illusion of control over what seems beyond our control. When bidding, we prefer to focus on our own shortcomings or regrets. We can reflect on our relationship with the person we are losing and think of all the times we felt left out or hurt them.

We usually think of times when we could say something we didn't want to say and wish we could change what we did. Sometimes we also assume that if circumstances had turned out differently, then we would not have found ourselves in such an emotionally difficult situation in our lives.

Depression

In the process of mourning, there comes a period when our imagination calms down and we begin to examine the reality of our present circumstances. There is no more desire to have any conversations and we have to deal with the current situation.

At this stage of grief, the loss of a loved one becomes more apparent. Our anxiety begins to subside, the emotional haze dissipates, and the inevitability and inevitability of loss become more apparent.

As melancholy grows, we prefer to withdraw into ourselves at this time. We may feel that we are withdrawing, becoming less friendly, and talking less to people about our situation. While this is a normal part of the mourning process, dealing with depression after the death of a loved one can be very difficult.

Acceptance

Acceptance is the last of the 5 stages of grief. When we reach a state of acceptance, it does not mean that we no longer experience the pain of loss. On the contrary, we no longer confront the reality of our circumstances and try to change them.

At this stage, sadness and sadness may still prevail. But at this stage of the mourning process, denial, bargaining, and anger are less frequently used as emotional coping mechanisms.

How long do the stages of grief last?

There is no specific duration for each of these phases. One person may go through the phases of grief quickly, for example in a few weeks, while for another it may take months or even years. It is completely natural that you go through these phases at your own pace.

In studying the 5 stages of grief, it is important to remember that people experience grief in different ways. Therefore, you may or may not experience each of these phases, or you may experience them sequentially. The stages of the grieving process are often confused. We can also move from one stage to another and perhaps return to it again before completely moving to a new level.

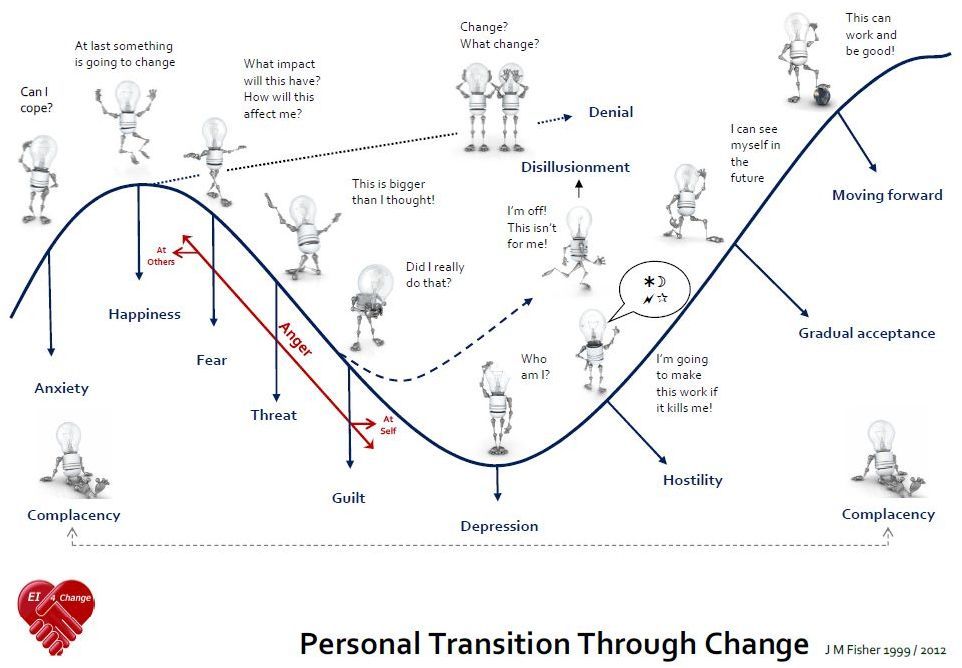

Additional Combustion Processes

Even though Elisabeth Kübler Rossa's 5 Stages of Grief is one of the best-known systems of grief and loss, there are other types of structures that should also be explored. Each of them tries to describe how grief is perceived and overcome.

Each of them tries to describe how grief is perceived and overcome.

These concepts can help those who are experiencing the death of a loved one and can give them a deeper understanding. They are also used by healing professionals, enabling them to give attention to people who are bereaved and looking for the right direction.

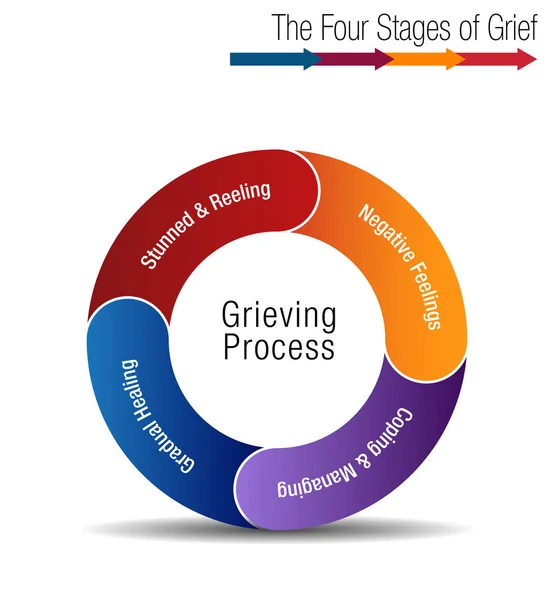

The Four Stages of Grief

John Bowlby, a renowned psychologist, focused his research on the emotional relationship between parents and children.

According to him, early experiences of attachment to significant people in our lives, such as parents, affect our relationships and feelings of safety and security.

British psychiatrist Colin Murray Parkes created the concept of mourning based on Bowlby's theory of attachment, suggesting that there are four periods of mourning after the death of a loved one:

Shock and numbness: inability to acknowledge loss at the moment.![]() When trying to deal with our emotions, we most strongly associate with the Küblerian stage of denial. Parkes states that this stage also includes bodily suffering, which can lead to somatic or physical complications.

When trying to deal with our emotions, we most strongly associate with the Küblerian stage of denial. Parkes states that this stage also includes bodily suffering, which can lead to somatic or physical complications.

Comfort: As we experience loss during this period of mourning, we may begin to seek comfort to replace the void left by our dead loved one. This can be achieved by recreating memories through photographs and looking for information that points to the person in order to feel connected to them. During this period, we become very obsessed with the deceased.

Despair and disorganization: during this phase we may experience confusion and anger. The fact that our loved one will not return seems to be true, and it can be hard for us to understand or find hope for the future. During this phase of mourning, we may feel somewhat lost and withdraw from others while we grieve.

Reorganization and recovery: at this stage we are more optimistic that our brain and heart can be restored. As in the acceptance stage of Kübler Ross, grief or longing for a deceased loved one persists. We find the smallest ways to restore normal daily life, moving towards healing and reconnecting with others for support.

As in the acceptance stage of Kübler Ross, grief or longing for a deceased loved one persists. We find the smallest ways to restore normal daily life, moving towards healing and reconnecting with others for support.

7 Stages of Grief Model

Some argue that there are seven stages of grief, not just four or five. This more complex model of the mourning process includes the following:

1) Surprise and disbelief . Whether the loss happened suddenly or was expected, it can be a shock. You experience emotional numbness and may even be in denial about the loss.

2) Resentment and guilt . At this stage of grief, the grief of loss begins to manifest. At this emotional moment, you may also feel guilty about asking for extra support from family and friends.

3) Anger and bargaining . You may be offended by loved ones or yourself. You can try to "make a deal" with the higher powers, demanding that the loss be reversed in exchange for some action on your part.

4) Depression and isolation . As you reflect on your loss, you may begin to feel lonely and miserable. At this point in the mourning process, you begin to realize the reality of your loss.

5) Increase . You begin to adjust to your new existence and the pain of loss begins to lessen. At this stage of the mourning process, you may feel more at ease.

6) Recovery and overcoming . This phase of the mourning process involves taking steps to move forward. You begin to restore your new normal life, overcoming all the difficulties that arise.

7) Acceptance and optimism . At the last stage of the mourning process, there is an acknowledgment of the loss and hope for the future. This does not mean that you no longer experience other emotions; rather, you have accepted them and are ready to move on.

How to Help a Grieving Person?

When someone is experiencing a loss, it can be difficult to know what to say or do. We do our best to comfort the person, but sometimes our efforts may seem insufficient or ineffective.

We do our best to comfort the person, but sometimes our efforts may seem insufficient or ineffective.

Here are some considerations to keep in mind if a loved one is going through phases of grief:

- Avoid saving or restorative activities. In an effort to help, we may make upbeat, optimistic remarks or even make jokes in an attempt to alleviate their suffering or “cure” them. Although the goal is sincere, this method can give the person the impression that their suffering is not acknowledged, heard, or justified.

- Do not use excessive force. We can assume that if you encourage a person to discuss and think about his feelings before he is ready, this will help him faster. This is not always true and can potentially interfere with their recovery.

- Ensure accessibility. Give people a place to mourn. This informs the person that you are available at any time. You can ask him to talk to you, but if he is not yet ready, we must give him sympathy and support.

Remind him that you are around and he can come to you at any time.

Remind him that you are around and he can come to you at any time.

Conclusion

It is important to remember that each person experiences loss differently. While it is possible to experience all five phases of grief, it can be difficult to attribute your emotions to any one of them. Be patient with yourself and your emotions as you deal with the loss.

When you feel ready to discuss your concerns with loved ones or a healthcare professional, do so. If you're supporting someone who has lost a spouse or loved one, remember that you don't have to do anything special. Just give them a chance to speak as soon as they are ready.

Five stages of grief - truth or myth?

- Claudia Hammond

- BBC Future

Denial, anger, compromise, depression and acceptance. Is it true that a person experiencing the pain of loss goes through certain stages? Let's look at the research data.

image copyrightMilan Popovic / Unsplash

"Tosca is a place we don't know until we visit it ourselves. We realize that loved ones can die, but we don't know exactly what awaits us in the first days and weeks after losses".

These are the words of the American writer Joan Didion, who described her feelings in the first year after the death of her husband in an extremely emotional confession "The Year of Magical Thinking".

The theory of the five stages of grief - denial, anger, compromise, depression and acceptance - is firmly rooted in popular culture.

Articles are written about her and remembered in serials, and the artist Damien Hirst created a series of paintings, calling them the acronym "DABDA" (denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance).

How long each stage lasts is not specified, but it is believed that all of them must pass in a certain sequence.

- Regular exercise saves from depression.

But not always

But not always - How hormones, immunity, microbes and pulse affect our character

- How parental quarrels affect the health of children

studied the disposition of children to parents) and Colin Murray-Parks.

Researchers interviewed 22 widows and identified four stages of grief: numbness, searching and longing, depression and rethinking.

The modern classification was developed by psychologist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, who worked with terminally ill patients and asked about their near-death experiences.

Kübler-Ross, by the way, radically changed the attitude towards palliative care and raised the question of the doctor's responsibility not only for the health of patients, but also for how they live their last days.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,How does a terminally ill person feel?

Pass the podokast

Podkast

SHO TS BULO

GOLD ISTORIA TIZHNA, Yaku explain our magazines

VIPASS

9000 In the early 2000s, Yale University researchers first took up this topic.

Over the course of three years, they interviewed 233 bereaved people (usually a wife or husband). The interviews were conducted approximately six, eleven and nineteen months after death.

The researchers did not look at cases of violent death of a relative or complex grief reactions.

The picture they got was more complex than the five-stage hypothesis. The researchers found that the most common emotion was acceptance, while denial was not experienced by everyone or to the same extent.

The second strong emotion was longing, and a depressed state accompanied all stages, and it was more pronounced than anger.

In addition, the emotional stages did not change each other in a clear sequence. A person in the third stage of grief could, for example, experience acceptance rather than anger.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption, A popular theory is that when we experience grief, we go through five successive stages.

Longing for the dead can last for years, but in the end, most people cope with grief.

For ethical reasons, the first interviews were conducted only a month after death, and therefore the researchers did not have an accurate picture of what a person feels in the first days and weeks after the loss.

Later, a study of people's reactions to violent death was conducted, but its participants were mainly students who lost more distant relatives than their spouse.

A strict sequence of stages was also not confirmed, although acute mental pain was more characteristic of the first stage, and acceptance - the last. However, unlike in the previous study, the scientists did not follow the reactions of one person over a long period of time.

Another study found that older people experience loss differently.

George Bonanno of Columbia University observed elderly couples before and after the death of one of the spouses. He found that 45% of people did not feel severe pain either immediately after the death of their other half, or later.

He found that 45% of people did not feel severe pain either immediately after the death of their other half, or later.

10% of widowers and widowers even felt some relief. People showed resilience and were able to cope with grief.

Bonanno's latest study in 2012 also disproved the idea of stages of grief.

Whatever the results of the research, however, the theory of the five stages of grief is attractive in a certain sense, because it gives people hope for gradual relief.

Ruth David Koenigsberg, author of The Truth About Grief, notes that the five-stage theory makes people feel certain things.

"It calms those who have similar emotions, but makes those who experience the death of loved ones differently feel guilty," Koenigsberg writes.

Image copyright, Unsplash

Image caption,Everyone experiences loss in their own way

"A person may think that something is wrong with him, that he does not feel what he should feel," the author adds.

However, studies clearly show that there is simply no "correct" way to mourn a loved one. Everyone experiences grief differently, and that's natural.

The sense of loss remains, but the longing goes away with time, at least for most people.

Some "scenario" of what you will experience next can be somewhat reassuring, but, unfortunately, real experience often differs from theory.

After all, life is much more complicated.

The purpose of the article is general information. It cannot replace the medical advice of a specialist. The BBC is not responsible for any diagnosis made by reader based on information from the site. The BBC is not responsible for the content of any external Internet sites linked to by the authors of the article, nor does it endorse any commercial product or service mentioned by on on any site. Always consult your doctor if you have questions related to your health.

Learn more